Abstract

C-peptide is co-secreted with insulin and is not subject to hepatic clearance and thus reflects functional β-cell mass. Assessment of C-peptide levels can identify individuals at risk for or with type 1 diabetes with residual β-cell function in whom β cell-sparing interventions can be evaluated, and can aid in distinguishing type 2 diabetes from Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults and late-onset type 1 diabetes. To facilitate C-peptide testing, we describe a quantitative point-of-care C-peptide test. C-peptide levels as low as 0.2 ng/ml were measurable in a fingerstick sample, and the test was accurate over a range of 0.17 to 12.0 ng/ml. This test exhibited a correlation of r = 0.98 with a high-sensitivity commercial ELISA assay and a correlation of r = 0.90 between matched serum and fingerstick samples.

Keywords: C-peptide, LADA, MODY, point-of-care, diabetes

Introduction

Insulin deficiency is the proximal cause of hyperglycemia in type-1 diabetes (T1D) and in advanced type-2 diabetes (T2D), although the specific mechanisms responsible differ. 1 In the case of classical T1D, this is the result of immune destruction of β cells. 2 In long-standing T2D, β cell exhaustion resulting from the demands of compensatory hyperinsulinemia to overcome insulin resistance and the deleterious effects of glucolipotoxicity combine to reduce functional β cell mass, leading to insulinopenia.3,4 C-peptide is the amino acid sequence between the B and A chains of mature insulin that is cleaved from proinsulin and is stored in equimolar amounts with mature insulin in the β cell secretory granule and that is released with insulin following glucose stimulation. 5 Since C-peptide is not subject to post-secretion processes that alter circulating levels of insulin, such as first-pass hepatic clearance, degradation by insulin-degrading enzyme, etc., C-peptide levels are considered a superior clinical biomarker for β-cell function,6-8 as they more directly reflect initial insulin granule release and, thus, functional β-cell mass. A practical advantage of C-peptide determination over insulin is that the former can be evaluated in patients undergoing insulin therapy.

The decline in C-peptide during the course of T1D is well characterized, 9 although many patients with long-standing T1D can exhibit residual C-peptide production that suggests persistent β cell function.10,11 Thus, assessment of C-peptide levels in diagnosed T1D patients may identify those for whom β cell-sparing therapies are most likely to be efficacious. More recently, C-peptide levels have emerged as an important parameter in the management of T2D, since they can predict the need for future insulin therapy, especially when combined with postprandial glucose levels, 12 as well as predicting hypoglycemia risk in T2D individuals initiating insulin therapy. 13

While most patients with diabetes can be accurately classified as T1D or T2D, a substantial proportion of patients with presumed T2D exhibit diabetes autoantibody positivity, generally to GAD65 or IA-2. This intermediate category of diabetes is termed Latent Autoimmmune Diabetes in Adults (LADA).14,15 Earlier studies showed that patients in this group more often failed therapy with secretagogues and progressed to insulin dependency faster.16,17 Determination of C peptide levels has been shown to facilitate discrimination of LADA from T2D 18 and to predict β cell failure in GAD65 antibody-positive LADA patients.19,20 C-peptide is also important, in conjunction with autoantibody determination, in distinguishing late-onset T1D from T2D to enable appropriate management. 21

Point-of-care (POC) testing for blood glucose has long been a mainstay of management of T1D and insulin-requiring advanced T2D, although self-monitoring of blood glucose for non-insulin-requiring T2D does not confer clinical benefit.22-23 POC testing for other diabetes analytes, such as diabetes-related autoantibodies, have not been developed to date, although more rapid tests for hemoglobin A1c, for example, are available. 24 C-peptide is an important diabetes biomarker that is amenable to POC technology, and a POC C-peptide test should be useful in a variety of settings, including evaluation of β-cell reserve in individuals at risk for T1D, with long-standing T2D or LADA, and as an intermediate endpoint in T1D prevention trials. 25 To facilitate more widespread C-peptide testing, we have developed a lateral-flow immunoassay POC device for quantitative C-peptide determination in serum or whole blood and assessed its performance in comparison to a commercial predicate test.

Methods

Study Population

Fasting sera were collected from 680 subjects and stored at −80°C for further analyses. The sample cohort included 219 control healthy subjects, 194 subjects with prediabetes, 134 subjects with newly diagnosed or confirmed T1D, and 133 subjects with T2D. The study population was recruited in accordance with institutional review board guidelines for human subjects, and parental/guardian consent was obtained for all participants under 18 years of age. Matched fingerstick whole blood and serum samples were tested in 109 subjects.

Insudex® C-Peptide Test Description

The Insudex® C-peptide device is a two-site sandwich immunoassay. When a diluted serum or fingerstick whole blood sample is applied to the test cartridge sample application port, colloidal gold nanoparticles coated with an anti-C-peptide monoclonal antibody are rehydrated and interact with C-peptide in the sample, resulting in colloidal gold-C-peptide complexes. These complexes migrate via capillary action to the test membrane, where another anti-C-peptide monoclonal antibody is bound at the test line, allowing capture of the colloidal gold-C-peptide complexes to form a reddish-purple line. Color development is complete by 15 minutes. The color intensity of the test line measured by the proprietary Insudex® reader is proportional to the concentration of C-peptide in the sample. The reader, using lot-specific calibration data, converts this color reading into a test result that is displayed on the screen.

Test Performance Assessments

The precision of the method was evaluated by analyzing 3 separate pools of patient serum with low, normal, and increased C-peptide levels. The pools were aliquoted into individual tubes and stored frozen at −80°C. Aliquots were analyzed in duplicate twice daily for 20 consecutive days, with a new aliquot being used for the morning and afternoon precision studies. The results for within-run, between-run, between-day, and total imprecision are shown in Table 1 (upper panel) and described below.

Table 1.

Performance Characteristics of the Insudex® C-Peptide Test.

| Pool | C-peptide a | Within run | Between run | Between day | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 0.932 | SD | 0.055 | 0.01 | 0.043 | 0.071 |

| CV (%) | 5.9 | 1.1 | 4.6 | 7.6 | ||

| Normal | 3.160 | SD | 0.181 | 0.095 | 0.101 | 0.228 |

| CV (%) | 5.7 | 3 | 3.2 | 7.2 | ||

| Increased | 6.370 | SD | 0.219 | 0.376 | 0.169 | 0.467 |

| CV (%) | 3.4 | 5.9 | 2.7 | 7.3 | ||

| Distribution of C-Peptide Levels in the Study Population. | ||||||

| Group | N | Median a | 25th percentile | 75th percentile | IQR | |

| Normal/healthy | 219 | 2.11 | 1.30 | 3.10 | 1.81 | |

| Pre-diabetes | 194 | 1.36 | 0.73 | 2.38 | 1.65 | |

| Type 2 diabetes | 133 | 1.03 | 0.69 | 1.66 | 0.97 | |

| Type 1 diabetes | 134 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.14 | |

C-peptide concentration in ng/mL.

A method comparison study was also performed using serum obtained from 200 individuals. The predicate method used for comparison was the Siemens ADVIA Centaur XP (Siemens Medical; Malvern, PA) test. Previously frozen aliquots of serum from patients were thawed and analyzed using both the Centaur XP and the Insudex® C-peptide test. The data were analyzed using Deming regression statistics.

The correlation between serum and fingerstick blood samples in 109 subjects was also determined using the Insudex® C-peptide test. These data were also analyzed using Deming regression statistics.

Calibrants for the above assays were serum pools from the University of Missouri that have been previously used for C-peptide assay harmonization studies.26,27

Results

Analytical Performance

Analytical sensitivity: The assay range of the Insudex® C-peptide test is from 0.17 ng/mL to 12.0 ng/mL. The limit of detection (LoD) was calculated to be 0.05 ng/mL. The limit of quantitation (LoQ, analytical) was calculated to be 0.17 ng/mL (Standard deviation (SD) 0.02, % coefficient of variance (CV) 11.17). No hook effect was detected up to 80 ng/mL. Analytical specificity: There was no interference from high, clinically feasible levels listed for bilirubin (24 mg/dL), hemoglobin (250 mg/dL), triglycerides (1000 mg/dL), insulin (375 µU/mL), proinsulin (1.25 ng/mL), glucagon (2500 pg/mL), calcitonin (500 pg/mL), somatostatin (12.5 ng/mL), or secretin (6250 ng/mL). The results of performance analyses demonstrate within-run, between-run, and between-day CVs of 7.2% to 7.6% (Table 1, lower panel).

C-Peptide Distribution in the Study Population

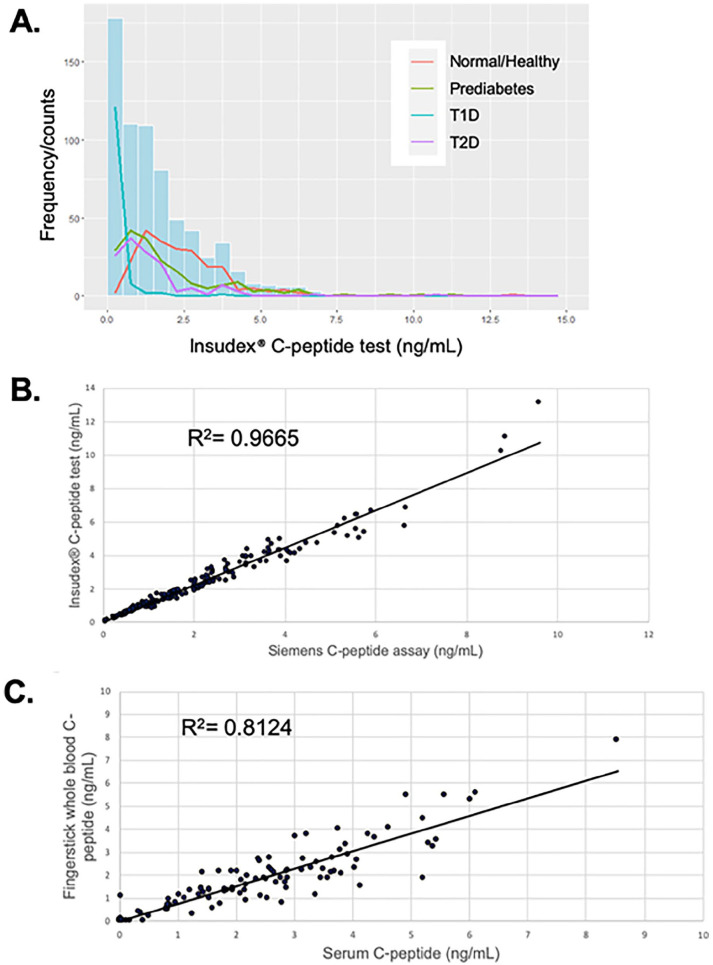

A cohort of 680 subjects, including healthy controls, and subjects with prediabetes, T1D, and T2D were tested with the Insudex® C-peptide test. The distribution (Figure 1A) demonstrated the predicted trends for each group, with T1D samples exhibiting the lowest values (median 0.07), while prediabetes and T2D samples exhibited higher levels (medians of 1.35 and 1.03, respectively), and control samples exhibiting the highest levels (median 2.11; Table 1, lower panel). Based upon the 25th and 75th percentiles and the interquartile range (IQR) shown in Table 1, lower panel, the C-peptide levels in the T1 and T2D groups were relatively tightly clustered around the median, while the levels in the control and prediabetes groups were more dispersed.

Figure 1.

(A) Distribution of C-peptide levels in normal/healthy, prediabetes, T1D, and T2D subjects using the Insudex® C-peptide POC test (n = 680). (B) Correlation between C-peptide levels obtained using the Insudex® C-peptide POC test vs the Siemens ADVIA Centaur XP test (n = 200). (C) Correlation between serum and fingerstick whole blood C-peptide levels using Insudex® C-peptide POC test (n = 109). R 2 values are based on Deming regression analyses.

Performance of the Insudex® C-Peptide Test Compared to the Siemens ADVIA Centaur CpS Predicate Assay

200 serum samples were run on the Insudex® C-peptide test and the Siemens ADVIA Centaur CpS assay (Figure 1B). The correlation coefficient R for this comparison using a Deming regression analysis was 0.979, and the slope and intercept and the 95% confidence intervals were 1.147 (1.114 to 1.180) and −0.068 (−0.154 to 0.018), respectively.

Comparison of Performance of the Insudex® C-Peptide Test in Fingerstick Whole Blood Compared to Serum

109 matched fingerstick whole blood and serum samples were tested for matrix equivalency (Figure 1C). The correlation coefficient R for this comparison using a Deming regression analysis was 0.901, representing good agreement between the 2 sample types. A subset of 83 samples were analyzed for any impact of hematocrit on serum C-peptide concentrations. There was no correlation (r = 0.1257) between packed cell volume and C-peptide concentrations determined with the Insudex® C-peptide test (data not shown).

Discussion

There has been increasing interest over the last several years in characterizing the development of T1D in more detail; in particular, defining stages of T1D development that reflect distinct phases of β-cell functional capacity.28-30 A major goal of these efforts is to enable more accurate assessment of disease risk and better disease management, thus contributing to the realization of precision medicine-based diabetes care.31-34 An important parameter in these studies has been determination of C-peptide levels in the pre-symptomatic, 35 perionset,36-37 and early 38 and late39,40 post-diagnosis periods. Collectively, these studies establish assessment of C-peptide levels as a crucial biomarker to stage T1D. 41 As described above, C-peptide determination can also aid in the assessment of β-cell reserve in patients with long-standing T2D to anticipate need for insulin therapy 12 and, in conjunction with autoantibody status, to distinguish T2D from LADA or late-onset T1D.18,21 Finally, C-peptide has emerged as an important component of diagnosis of Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY) in parallel with assessment of autoantibody status and to direct subsequent genetic analysis.42-45 These data support the adoption of routine screening of C-peptide levels and autoantibody testing in at-risk as well as prediabetic and diagnosed T1D and T2D populations to enable comprehensive assessment of diabetes category and stage, thus facilitating the application of precision medicine to diabetes management and care. More widespread incorporation of C-peptide testing in these situations will be facilitated by the availability of the rapid, accurate, convenient, and cost-effective test we describe in this report.

Conclusions

The Insudex® C-peptide POC test exhibited a wide dynamic range and sensitivity comparable to a laboratory-based predicate assay. The availability of a rapid, simple-to-use POC test for C-peptide will facilitate staging of presymptomatic T1D and differential diagnosis of late-onset T1D, LADA, and MODY.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CV, coefficient of variance; LADA, latent autoimmune diabetes in adults; LoD, limit of detection; LoQ, limit of quantitation; MODY, maturity-onset diabetes of the young; T1D, type 1 diabetes; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: PVR, CTR, and SRN are shareholders in, PVR, EB, DN-S, and SRN are employees of, and SC is a paid consultant for Diabetomics, Inc.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by Diabetomics, Inc.

ORCID iDs: Steven C. Kazmierczak  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4668-4634

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4668-4634

Charles T. Roberts  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1756-5772

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1756-5772

References

- 1. Cnop M, Welsh N, Jonas JC, Jörns A, Lenzen S, Eizirik DL. Mechanisms of pancreatic β-cell death in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: many differences, few similarities. Diabetes. 2005;54(suppl):S97-S107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Belle TL, Coppieters KT, Von Herrath MG. Type 1 diabetes: etiology, immunology, and therapeutic strategies. Phys Rev. 2011;91(1):79-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marchetti P, Lupi R, Del Guerra S, Bugliani M, Marselli L, Boggi U. The beta-cell in human type 2 diabetes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;771:288-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Halban PA, Polonsky KS, Bowden DW, et al. β-cell failure in type 2 diabetes: postulated mechanisms and prospects for prevention and treatment. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1751-1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mayer JP, Zhang F, DiMarchi RD. Insulin structure and function. Peptide Sci. 2007;88(5):687-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jones AG, Hattersley AT. The clinical utility of C-peptide measurement in the care of patients with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2013;30(7):803-817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Perry MH, McDonald TJ. Detection of C-peptide in urine as a measure of ongoing beta cell function. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1433:93-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leighton E, Sainsbury CAR, Jones GC. A practical review of C-peptide testing in diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8(3):475-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Palmer JP. C-peptide in the natural history of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2009;25(4):325-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang L, Lovejoy NF, Faustman DL. Persistence of prolonged C-peptide production in type 1 diabetes as measured with an ultrasensitive C-peptide assay. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):465-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. VanBuecken DE, Greenbaum CJ. Residual C-peptide in type 1 diabetes: what do we really know? Pediatr Diabetes. 2014;15(2):84-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saisho Y. Postprandial C-peptide to glucose ratio as a marker of β cell function: implication for the management of type 2 diabetes. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(5):744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Landgraf W, Owens DR, Frier BM, Zhang M, Bolli GB. Fasting C-peptide, a biomarker for hypoglycemia risk in insulin-naïve people with type 2 diabetes initiating insulin glargine 100 U/ml. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(3):315-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Naik RG, Brooks-Worrell BM, Palmer JP. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(12):4635-4644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laugesen E, Ostergaard JA, Leslie RDG. Latent autoimmune diabetes of the adult: current knowledge and uncertainty. Diabet Med. 2015;32(7):843-852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Irvine WJ, Gray RS, McCallum CJ, Duncan LJP. Clinical and pathogenic significance of pancreatic-islet-cell antibodies in diabetics treated with oral hypoglycaemic agents. Lancet. 1977;1(8020):1025-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zimmet PZ. The pathogenesis and prevention of diabetes in adults: genes, autoimmunity, and demography. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(7):1050-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Subhakumari KN. Role of anti-GAD, anti-IA2 antibodies and C-peptide in differentiating latent autoimmune diabetes in adults from type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2016;36(3):313-319. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li X, Huang G, Yang L, Zhou Z. Variation of C peptide decay rate in diabetic patients with positive glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody: better discrimination with fasting C peptide. BMC Endocr Disord. 2013;13:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li X, Chen Y, Xie Y, et al. Decline pattern of beta-cell function in adult-onset latent autoimmune diabetes: an 8-year prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(7):2331-2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thomas NJ, Lynam AL, Hill AV, et al. Type 1 diabetes defined by severe insulin deficiency occurs after 30 years of age and is commonly treated as type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2019;62(7):1167-1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Malanda UL, Welschen LM, Riphagen II, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Bot SD. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who are not using insulin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(1):CD005060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Young LA, Buse JB, Weaver MA, et al. Glucose self-monitoring in non–insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):920-929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arnold WD, Kupfer K, Little RR, et al. Accuracy and precision of a point-of-care HbA1c test. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2020;14(5):883-889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krischer JP, Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group. The use of intermediate endpoints in the design of type 1 diabetes prevention trials. Diabetologia. 2013;56(9):1919-1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Little RR, Rohlfing CL, Tennill AL, et al. Standardization of C-peptide measurements. Clin Chem. 2008;54(6):1023-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stoyanov AV, Connolly S, Rohlfing CL, Rogatsky E, Stein D, Little RR. Human C-peptide quantitation by LC-MS isotope-dilution assay in serum or urine samples. J Chromatogr Sep Tech. 2013;4(3):172-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Insel RA, Dunne JL, Atkinson MA, et al. Staging presymptomatic type 1 diabetes: a scientific statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(10):1964-1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ziegler AG, Bonifacio E, Powers AC, Todd JA, Harrison LC, Atkinson MA. Type 1 diabetes prevention: a goal dependent on accepting a diagnosis of an asymptomatic disease. Diabetes. 2016;65(11):3233-3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bonifacio E, Mathieu C, Nepom G, et al. Rebranding asymptomatic type 1 diabetes: the case for autoimmune beta cell disorder as a pathological and diagnostic entity. Diabetologia. 2017;60(1):35-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rich SS, Cefalu WT. The impact of precision medicine in diabetes: a multidimensional perspective. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(11):1854-1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gloyn AL, Drucker DJ. Precision medicine in the management of type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(11):891-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chung WK, Erion K, Florez JC, et al. Precision medicine in diabetes: a consensus report from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2020;43(7):1617-1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Klonoff DC, Florez JC, German M, Fleming A. The need for precision medicine to be applied to diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2020;14(6):1122-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sims EK, Chaudhry Z, Watkins R, et al. Elevations in the fasting serum proinsulin-to-C-peptide ratio precede the onset of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;39(9):1519-1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bogun MM, Bundy BN, Goland RS, Greenbaum CJ. C-peptide levels in subjects followed longitudinally before and after type 1 diabetes in TrialNet. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):1836-1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sosenko JM, Palmer JP, Rafkin-Mervis L, et al. Glucose and C-peptide changes in the perionset period of type 1 diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Trial-Type 1. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(11):2188-2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ludvigsson J, Carlsson A, Delo A, et al. Decline of C-peptide during the first year after diagnosis of Type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;100(2):203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hao W, Gitelman S, DiMeglio LA, Boulware D, Greenbaum CJ. Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group. Fall in C-peptide during first 4 years from diagnosis of type 1 diabetes: variable relation to age, HbA1c, and insulin dose. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(10):1664-1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee TH, Kwon AR, Kim YJ, Chae HW, Kim HS, Kim DH. The clinical measures associated with C-peptide decline in patients with type 1 diabetes over 15 years. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28(9):1340-1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sosenko JM. Staging the progression to type 1 diabetes with prediagnostic markers. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23(4):297-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shields BM, Shepherd M, Hudson M, et al. Population-based assessment of a biomarker-based screening pathway to aid diagnosis of monogenic diabetes in young-onset patients. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(8):1017-1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Majidi S, Fouts A, Pyle L, et al. Can biomarkers help target maturity-onset diabetes of the young genetic testing in antibody-negative diabetes? Diabetes Technol Ther. 2018;20(2):106-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Goodsmith MS, Skandari MR, Huang ES, Naylor RN. The impact of biomarker screening and cascade genetic testing on the cost-effectiveness of MODY genetic testing. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(12):2247-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Carlsson A, Shepherd M, Ellard S, et al. Absence of islet autoantibodies and modestly raised glucose values at diabetes diagnosis should lead to testing for MODY: lessons from a 5-year pediatric Swedish national cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(1):82-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]