Abstract

Objective

To examine the qualitative literature on low‐income women's perspectives on the barriers to high‐quality prenatal and postpartum care.

Data Sources and Study Setting

We performed searches in PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, SocIndex, and CINAHL for peer‐reviewed studies published between 1990 and 2021.

Study Design

A systematic review of qualitative studies with participants who were currently pregnant or had delivered within the past 2 years and identified as low‐income at delivery.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

Two reviewers independently assessed studies for inclusion, evaluated study quality, and extracted information on study design and themes.

Principal Findings

We identified 34 studies that met inclusion criteria, including 23 focused on prenatal care, 6 on postpartum care, and 5 on both. The most frequently mentioned barriers to prenatal and postpartum care were structural. These included delays in gaining pregnancy‐related Medicaid coverage, challenges finding providers who would accept Medicaid, lack of provider continuity, transportation and childcare hurdles, and legal system concerns. Individual‐level factors, such as lack of awareness of pregnancy, denial of pregnancy, limited support, conflicting priorities, and indifference to pregnancy, also interfered with the timely use of prenatal and postpartum care. For those who accessed care, experiences of dismissal, discrimination, and disrespect related to race, insurance status, age, substance use, and language were common.

Conclusions

Over a period of 30 years, qualitative studies have identified consistent structural and individual barriers to high‐quality prenatal and postpartum care. Medicaid policy changes, including expanding presumptive eligibility, increased reimbursement rates for pregnancy services, payment for birth doula support, and extension of postpartum coverage, may help overcome these challenges.

Keywords: health policy, maternal, Medicaid, perinatal, pregnancy

What is known on this topic

High‐quality prenatal and postpartum care improves maternal and infant health outcomes.

Medicaid‐insured women are less likely to attend a prenatal or postpartum care visit.

What this study adds

We examine qualitative research on low‐income women's experiences of prenatal and postpartum care.

We identified individual, structural, and quality‐related barriers to care, including difficulty enrolling in Medicaid insurance, lack of transportation and childcare, poor provider continuity, denial of pregnancy, discrimination, and disrespect.

Based on identified themes, we offer targeted Medicaid policy solutions to improve prenatal and postpartum care uptake and value.

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2020, 861 women in the United States died from a pregnancy‐related cause, yielding the highest maternal mortality ratio in two decades at 23.8 deaths per 100,000 live births. 1 This rise was driven by increases in maternal death among non‐Hispanic Black and Hispanic women, reflecting widening racial disparities in maternal health. 1 More than half of these deaths occurred during the postpartum period, including 12% occurring more than 6 weeks postpartum. 2 In addition, rates of preterm birth remained high, affecting 1 in 10 infants, and were 50% higher among non‐Hispanic Black women compared to non‐Hispanic White women. 3 Improving these outcomes and reducing racial disparities in maternal and infant health is a high priority for state Medicaid programs, which financed 42% of births in 2020. 4

High‐quality prenatal and postpartum care are important tools to promote perinatal and newborn health. The current model of prenatal care in the United States recommends 12–14 individual patient visits begun during the first trimester of pregnancy. 5 Following birth, a comprehensive postpartum care visit is recommended within 6–12 weeks. 6 Prenatal care visits have been linked to reduced rates of maternal mortality and low‐birthweight birth, 7 and postpartum care improves detection of cardiac complications, hypertension, and depression. 6 Both visits provide an opportunity to manage chronic conditions and address concerns.

Despite comprising a larger share of high‐risk pregnancies, utilization of prenatal and postpartum care is lower among women with Medicaid insurance at delivery compared to those with private insurance at delivery. 8 Between 2016 and 2019, 21% of Medicaid‐insured women did not initiate prenatal care within the first trimester of pregnancy, and 15% did not attend a routine postpartum visit, compared to 6% and 5% of privately‐insured women, respectively. 9 , 10

Since the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, states have been required to offer continuous Medicaid coverage to pregnant women with household incomes at or below 133% of the federal poverty level (FPL) from conception through 60 days postpartum. 11 In most states, parents had higher eligibility cutoffs than childless adults. 12 In 2014, states were given the option to implement the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion for adults with incomes at or below 138% FPL regardless of pregnancy or parental status. In expansion states, this increased Medicaid coverage during the preconception and postpartum periods. 13 Despite this policy, a large number of pregnant women in expansion and nonexpansion states lost coverage at 60 days postpartum. 14

Even with insurance coverage and access to prenatal and postpartum visits, Medicaid‐eligible women may receive low‐quality care, reducing the value of these visits or the impetus to seek future care. Current measures used to assess the quality of prenatal and postpartum care are limited. 15 For instance, the most widely used measure of prenatal care quality, the Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization (APCU) index, captures only when prenatal care began and how many visits occurred compared to the recommended number of visits. 16 They do not indicate whether women received the full range of guideline‐recommended services and education or provide a score for the experience of care. 17 As a result, we have limited quantitative information about variation in the quality of care by insurance status, demographics, or region. 15

Qualitative research has the potential to clarify issues related to access and quality of prenatal and postpartum care; however, the use of qualitative research methodologies within the field of health services and policy research has been limited. 18 , 19 Qualitative techniques allow us to understand health behaviors and outcomes in practice with an emphasis on the experiences and views of patients. Qualitative findings are useful for validation and triangulation of quantitative results, promoting reflexivity, understanding the experiences of small or historically marginalized populations, and human‐centered design. The aim of this review is to examine the published qualitative literature on low‐income and Medicaid‐eligible women's perspectives of the barriers and facilitators to high‐quality prenatal and postpartum care. These findings can help clarify the enduring gaps in state Medicaid policies intended to promote the receipt of high‐quality prenatal and postpartum care in the United States.

2. METHODS

We conducted a systematic review of qualitative studies examining low‐income women's perspectives on access to and quality of prenatal and postpartum care. We archived the protocol for this review in PROSPERO on October 12, 2021 (No. CRD42021289660). The review was conducted according to PRISMA standards.

2.1. Identification of studies

Studies were eligible for inclusion if participants were (1) currently pregnant or within 2 years of delivery or end of pregnancy, (2) received pregnancy care in the United States, and (3) were Medicaid‐eligible or low‐income at the time of birth. We included peer‐reviewed qualitative and mixed‐methods studies published between 1990 and 2021. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table S1.

We performed searches in PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, SocIndex, and CINAHL in October 2021 using the search terms: (Title/Abstract) (qualitative OR mixed methods OR interview* OR focus group*) AND (Medicaid OR low‐income) AND (maternal OR pregnant OR pregnancy OR preconception OR prenatal OR postnatal OR postpartum OR perinatal) NOT (low‐income country*). We also reviewed the reference lists of eligible studies for titles missing from this search. Two authors independently conducted the title and abstract review and assessed full‐text articles for inclusion using Covidence Review Software. Conflicts were resolved through discussion and decision by a third reviewer.

2.2. Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted information from each study on aims, population, definition of “low‐income,” sample size, data collection methods, primary themes, and key quotations. We then grouped findings into overarching themes to highlight in the review while focusing on those with the greatest implications for Medicaid policy.

Study quality was evaluated by two reviewers using the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality appraisal checklist for qualitative studies (3rd edition) 20 and the 2018 Critical Assessment Skills Programme (CASP) Tool for Evaluating Qualitative Research. 21 These checklists contain a mixture of objective and subjective questions about the clarity of study aims, the rigor of study methods and data analyses, and reporting of ethics.

2.3. Note on language

In this article, we use the gendered terms “pregnant and postpartum women” and “maternal health” to match the language used to describe the populations interviewed in the reviewed papers; however, people of all genders, including nonbinary and transgender people, can become pregnant and give birth.

3. RESULTS

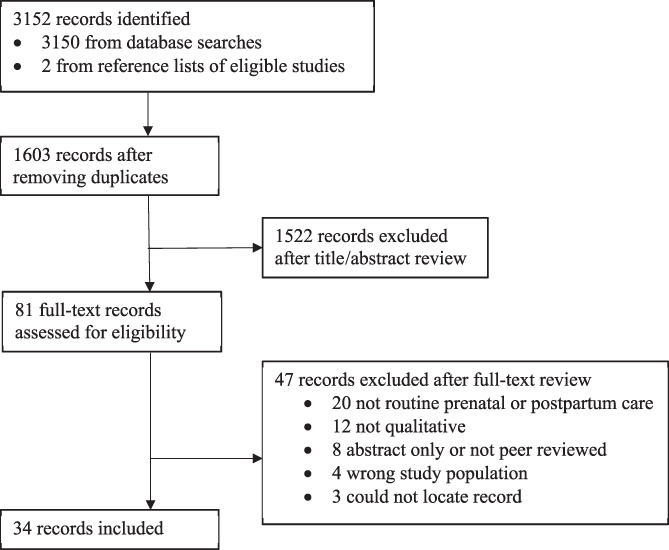

Our searches identified 1603 unique studies. After title, abstract, and full‐text screening, 34 studies met the criteria for inclusion. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for study inclusion. Twenty‐three studies focused on prenatal care, six on postpartum care, and five on both prenatal and postpartum care (Table S2). Semi‐structured interviews and focus groups were equally common (14 each), and six studies used a combination of the two methods. Eight of the studies were published before 2000, 8 between 2000 and 2009, and 18 in 2010 or after. Six studies restricted the study population to Black women, one to women who identified as Latina, and one to ethnic minority mothers. Four studies enrolled adolescent participants under age 17. Study quality was high overall; nearly all came within one point of fulfilling the 10‐item CASP checklist and within two points of fulfilling the 14‐item NICE checklist (91.1%). The most frequently missed items were the clear description of the role of the researcher, missing in 26.5% of studies, and adequate reporting of ethics, missing in 23.5%.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of study inclusion

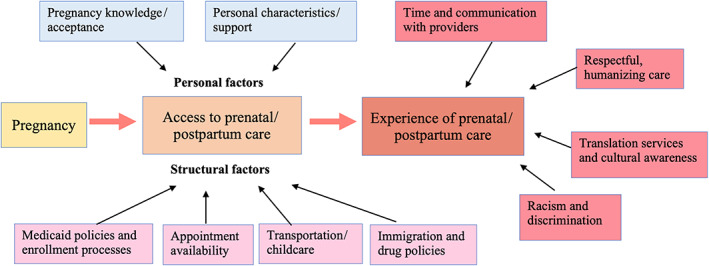

Participants described several barriers to receipt of timely, high‐quality prenatal and postpartum care. We categorized these into three themes: personal barriers to access, structural barriers to access, and experiences of care. Subthemes are listed in Table 1 with illustrative quotations and presented visually in Figure 2.

TABLE 1.

Medicaid member‐identified barriers to high‐quality, timely prenatal and postpartum care

| Themes | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|

| Individual barriers | |

| Lack of awareness of pregnancy 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 | “I did not know that I was pregnant, so I kept going with my life as usual until I found out the belly was growing, and I was pregnant and then that's when I started searching for more information and doing everything. If I would've known before, I would have definitely [sought prenatal care at] an earlier stage in the pregnancy” 27 |

| Considering abortion 27 , 29 , 31 | “I did not want to have her, until it got to the point that I had no other choice. I was too late by then” 29 |

| Shame and stigma surrounding with pregnancy 22 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 30 , 32 | “…it was all surrounding my shame and embarrassment, and that's what was the driving force of me not seeking prenatal care from the beginning is mostly my insecurities, my guilt and shame that I still feel from my past bad decisions, bad choices. So I did not seek prenatal – and honestly I tried to ignore that this whole thing was even happening, which you can only do for so long. But I did not seek prenatal care for the first six months” 27 |

| Limited support from friends or family 26 , 27 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 | “A lot of people do not know who to turn to or do not have their family's support at home” 33 |

| Conflicting life priorities and challenges (e.g., exhaustion, poor mental health, drug use, homelessness) 22 , 23 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 34 , 36 , 38 , 41 , 42 | “Yeah, when I was pregnant, like, I was like real [hungry] and we did not have any money. I always got food from home, but like at the end of the month our food always used to run out…. It used to run out a lot.” 42 |

| Lack of knowledge or belief that prenatal or postpartum care visits are important, especially when feeling fine 22 , 25 , 26 , 28 , 31 , 43 , 44 | “When you do not have a supportive mother, or a mother who was 14 when she had you, and did not get prenatal care and you were fine, why would you get prenatal care? They do not understand the value and importance of everything that could go wrong, but they just think, oh whatever, I'm pregnant” 26 |

| Structural barriers | |

| Medicaid enrollment challenges and delays and unreasonable cost of care without insurance 22 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 38 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 | “If you call the doctor to make an appointment, they will ask you, “What type of Medicaid do you have?” They are going to ask for your ID number to clarify first that your Medicaid is active. And once it's active, then they will make your appointment. If they do not accept it, they will not even schedule your appointment” 43 |

| “If you say, well, I do not have Medicaid, you need to talk to DHS about getting signed up for it. So make an appointment with DHS. DHS wants you to prove you pregnant, so you have to still go to a clinic just to get the help. They're not going to take a home pregnancy test or a phone call either. The paperwork is what you need” 28 | |

| “I was about 16–17 weeks when I found out being pregnant. They actually took them a month before they even gave me my Medicaid. I had to go to an emergency room and a free health center to do pregnancy testing and everything” 43 | |

| “I had always intended on going and having prenatal care, but the first blocker was the welfare department and getting Medi‐Cal… They had denied me Medi‐Cal because I was homeless [and therefore did not have an address].” 32 | |

| Challenges finding a provider accepting new patients on Medicaid or an available appointment time 22 , 26 , 27 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 42 , 43 , 48 | “They should have took them off instead of giving us numbers to doctors that did not accept Medicaid anymore. So we were going to these doctors and they were turning us around. So it took me about a month to find an actual doctor” 26 |

| “I found out I was pregnant at 5 weeks. It took time [to get into PNC] because I only had straight T‐19 [basic Medicaid] and a lot of doctors do not take that. So I was switching from doctor to doctor.” 30 | |

| Challenges with provider continuity and poor inter‐provider communication 23 , 26 , 27 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 39 , 42 , 47 , 49 , 50 | “My problem was that I had three or four different doctors, and none of them talked to each other, as far as I could tell. So they would contradict each other to me in terms of when I could, leave in terms of when I'd get a particular test.” 39 |

| “They did not know I had a seizure when I was having my daughter. They did not know none of that… They just started over from the beginning, it was new, everything was new to them, each and every time… There were different [providers] in there questioning me, same questions over and over” 31 | |

| “The day that [my Medicaid insurance] expired, [my postpartum care provider] did not accept me anymore… And they told me that I had to look for somewhere else… I did not have a choice” 42 | |

| Transportation challenges 22 , 23 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 36 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 | “It has been very difficult for me because of transportation. There's no bus where I live, you cannot say, ‘I'm going to take a bus and go to the clinic or a store’, because there aren't any. There's no taxi. There's Uber, but I need to have a bank account to be able to access it, which I also do not have” 27 |

| Childcare challenges 22 , 27 , 28 , 34 , 38 , 44 | “Well, just like I said, it's harder because we have four other kids who are all pretty little… I keep going places that are really far away from where I live, so it takes like three or four hours by the time someone gets to my house or I take them somewhere and then go the appointment and then go all the way back. So, that's kind of hard… I did not have anybody else to watch them.” 27 |

| Poor linkage to services, such as postpartum depression and substance use treatment 37 , 44 , 45 | “They never once referred me to a drug program, not once gave me any kind of information, did not even attempt to… Then, once I. … had my baby, they wanted to take her from me. Right then and there…. If you guys are so concerned with my child, with keep[ing] me away. … and so worried about my child's well‐being, why did not you do anything while I was pregnant, why did not you refer me to some kind of program?” 37 |

| Fear of legal consequences because of care or insurance seeking (e.g., immigration, drug use) 32 , 37 , 46 | “When I was almost 5 months pregnant and they were already telling me, you know, you have been testing positive for meth and marijuana and so, if this happens in your next trimester, then you are gonna be CPS involved.” 37 |

| Quality of care | |

| Not feeling heard 28 , 32 , 33 , 39 , 49 , 51 | “He wasn't answering my questions, he was very rushed. I'm trying to ask questions and he answered them on his way out the door. Then when I switched over to [new prenatal care site] I was voicing concerns about my pregnancy and they were just pushed off, not taken care of, pushed off. I wasn't happy about that” 32 |

| Not enough time with providers, especially in comparison to wait times 25 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 40 , 42 , 51 | “It was kind of a waste of time, to sit there all that time, and then, you know, be rushed out; pretty much I did not get anything accomplishedwith that” 28 |

| “You just get weighed. Other than that, paperwork and questions, and it's over” 28 | |

| Language barriers 46 , 52 | “I'm worried about the day I go into labor. Will there be an interpreter there for me? Or should I look for someone who will translate for me so I do not have to fight for it, or how should I do it honestly that is something that really makes me anxious. I understand some things in English, right, but not everything, and when it comes to words they use in the hospital, you understand less because they are more difficult things. I worry when I think about that.” 52 |

| Lack of respect for cultural differences and preferences 24 , 45 , 46 , 52 | “I had a male interpreter‚ in my situation‚ well, I wasn't going to get undressed in front of him because I want a woman, but a man, no. I am very modest and besides the fact that I'm a woman‚ I'm not going to show everything in front of a man” 52 |

| Racism or discrimination from providers 24 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 39 , 46 , 48 , 52 , 53 | “I told [my midwife] I did not like going to my appointments, and one day she just asked me, “do you do crack?” …Just because I do not want to come to my appointments, I gotta be a drug addict?… Why would she ask me if I smoke crack? But because I'm Black, she said crack, that's probably what it is” 48 |

| “It's a way a person will talk to you, look at you, and it would just be their whole body language towards you and you'll be able to tell. This one lady…it was just her whole demeanor, she looked at me like I was dirty. Basically, it was just the way she acted towards me that I knew it was because of my skin color.” 30 | |

| Disrespectful, dehumanizing, and overmedicalized care 23 , 24 , 36 , 39 , 45 , 51 | “They do not respect you; they talk down to you because you are a teen. Student doctors came in and out of the room all the time, disturbing me and waking me up. They practice on you like you are a guinea pig.” 24 |

| “That place is a puppy mill for babies. They do not want to answer questions, they were snotty and had no eye contact. The staff acted like they did not want to be bothered. The only reason I went was because Medicaid had not kicked in” 24 | |

| Feeling lesser than because of income, age, drug use, HIV‐status, or undocumented‐status 24 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 36 , 37 , 42 , 47 , 48 | “It depends on the money you make. That's how I feel. It depends on whether you have Medicaid or insurance. When I was on insurance, they treated me like a queen. But when I was off insurance, they like put me in a back room.” 47 |

| “Providers act like I do not know anything just because I am poor. I want to learn. Didn't get nothing out of it; keep repeating; feel like I'm not smart enough to ask questions” 28 | |

FIGURE 2.

Medicaid member‐identified factors affecting the use of timely, high‐quality prenatal and postpartum care [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.1. Personal barriers to access

Study participants identified several personal barriers—individual characteristics, desires, or beliefs – that limited their use of timely prenatal and postpartum care. For prenatal care, these included lack of awareness of pregnancy or denial of pregnancy, 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 consideration of abortion, 27 , 29 , 31 and limited social, family, or mental health support. 26 , 27 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 Women with an unplanned or unwanted pregnancy were more likely to note that they discovered their pregnancies at later gestational ages. Many then needed time to decide whether to carry the pregnancy to term, locate a prenatal care provider, and schedule an appointment. 23 , 25 , 27 Further delays in prenatal care occurred when women had feelings of shame or feared being stigmatized by their social networks due to their pregnancies. 27 , 37 , 54

Other personal barriers to prenatal and postpartum visit attendance included having conflicting life priorities or too much going on to attend a visit 22 , 23 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 34 , 36 , 38 , 41 , 42 and not knowing or believing that the visit was important. 22 , 25 , 26 , 28 , 31 , 43 , 44 Study participants explained that it was difficult to prioritize attendance when they had mental health challenges, were experiencing homelessness, poverty, legal issues, or partner abuse, had children at home to look after, or were exhausted from the demands of new parenthood. 29 , 30 , 36 Some women noted that after missing a visit, their providers did not follow up or would instruct them to see their regular primary care provider. 28 Women with healthy newborns and those who had experienced previous pregnancies were especially likely to express skepticism about the importance of a postpartum visit. 22 , 25

3.2. Structural and health system barriers to access

Structural barriers to prenatal and postpartum care were identified in every study. By far, the most common structural barrier involved navigating state Medicaid insurance policies. This included delays in enrollment in pregnancy‐related Medicaid 22 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 38 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 and difficulty finding prenatal care providers accepting new Medicaid patients. 22 , 26 , 27 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 42 , 43 , 48 These themes were raised by participants in 17 studies spanning nearly two decades. To gain pregnancy‐related Medicaid services, a pregnant person must provide proof of pregnancy, income, and citizenship or noncitizenship to their state Medicaid office. Women noted that simply acquiring proof of pregnancy was challenging, as it required finding transportation to an emergency room or health clinic for a blood test. It then took 2–4 weeks for Medicaid enrollment to be approved and activated. 28 , 43 Most perinatal providers will not schedule a prenatal care appointment until this step is completed. In addition, some prenatal care providers limit the number of Medicaid‐insured patients they accept, as Medicaid reimbursement for a standard prenatal visit is lower than private insurance reimbursement and requires a larger administrative burden. 55 Study participants described calling multiple providers to find one that would accept Medicaid insurance and waiting weeks for an appointment time. 26 , 27 , 43 Often, these barriers overlapped with personal delays in care seeking, such as the late discovery of pregnancy or homelessness. 32 Participants also described being cut off from Medicaid insurance suddenly at 2 months postpartum and fearing bills for postpartum care. 30 , 42

Women also described issues with provider continuity, both within and between pregnancies. 23 , 26 , 27 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 39 , 42 , 47 , 49 , 50 Factors that contributed to discontinuity of care included insurance churn (moving from uninsurance to Medicaid and from private insurance to Medicaid), changes in the insurance types a given provider accepts, developing new pregnancy risk factors that certain providers did not feel equipped to address, and changes in provider office locations. Shifts in prenatal care and delivery provider hinder communication and trust building among participants, leading to lower‐quality care or decisions to forgo postpartum care. Participants were frustrated that there was not better communication between providers, particularly when histories of major medical morbidities had not been shared. 31 , 39 , 44

Transportation 22 , 23 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 36 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 and childcare issues 22 , 27 , 28 , 34 , 38 , 44 were also a challenge for many low‐income women. Some clinics and Medicaid programs offered free transportation to appointments. While some women were grateful for these services and able to use them securely, others reported that they were unreliable and had challenging requirements, such as advance scheduling and restrictions on bringing children. 28 , 43 , 44 During focus groups, many women across studies and years were unaware of these services. 23 , 31 , 44

Some women who had recently immigrated to the United States or had undocumented status expressed fear that attending prenatal or postpartum care could lead to legal consequences, such as being deported, separated from their children, or denied future citizenship due to receipt of public assistance. 32 , 37 , 46 Even when protective policies were in place, distrust and stories about the negative experiences of others kept women from engaging in care. Likewise, women with current or previous drug use feared that visit attendance could result in legal consequences, such as removal of children from their care or arrest. 32 , 37 Often, these fears were compounded by threatening remarks from providers regarding the consequences of continuing drug use during pregnancy or while breastfeeding. 32 , 37

3.3. Experiences of care

Many study participants who did overcome access barriers to attend prenatal or postpartum visits reported receiving low‐quality care. Experiences of dismissal, 28 , 32 , 33 , 39 , 49 , 51 discrimination, 24 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 39 , 46 , 48 , 52 , 53 and disrespect 23 , 24 , 36 , 39 , 45 , 51 were common. Many participants attributed these negative experiences to their race, their insurance status, their age, or their substance use. 24 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 36 , 37 , 42 , 47 , 48 For instance, during focus groups with Black postpartum women in Michigan, participants shared that their prenatal care providers assumed they would not be intelligent enough to raise questions about their pregnancy because they were low‐income. 28 In addition, communication challenges were common among the women interviewed. These included difficulty understanding the provider's advice as a non‐native English speaker, 46 , 52 not being given all the information they requested, and not having enough time with providers to raise concerns. 25 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 40 , 42 , 51 Overall, women expressed frustration that after expending money, time, and energy to attend their appointments, they received little benefit. Women believed this could be remedied by providers listening carefully to their concerns and showing greater respect and compassion. 28 , 33 , 39 , 42 , 45 , 49 , 51 , 56

4. DISCUSSION

We found that the most frequently mentioned barriers to prenatal and postpartum care were structural. These included delays in gaining pregnancy‐related Medicaid coverage, challenges finding providers who would accept Medicaid, lack of provider continuity, transportation and childcare hurdles, and legal system concerns. Individual‐level factors also interfered with the timely use of prenatal and postpartum care. Women noted that lack of awareness of pregnancy, denial of pregnancy, limited support, conflicting priorities, and indifference contributed to delayed or skipped visits. These findings support the conceptual framework published by Khan and Bhardwaj in 1994, arguing that health system transformation is the primary barrier to receipt of prenatal care, followed by personal characteristics. 57

Despite spanning 30 years across publication dates, remarkably similar barriers to receipt of timely, high‐quality prenatal and postpartum care were raised within studies. Each of the seven personal barriers to care we identified was mentioned in a study from the 1990s and 2010 or after. This was also true for the nine structural themes, with the single exception of poor linkage to services, such as treatment for postpartum depression or substance use. Seven of the nine themes related to poor experiences of care were mentioned in studies published in the 1990s and after 2010. The two experience‐related themes that emerged only in later studies were women not feeling heard by providers and women being made to feel lesser because of income, age, HIV status, or substance use. The continued presence of these barriers suggests that the US medical system and policy landscape has not done enough to support prenatal and postpartum care access among low‐income women.

Importantly, many of the barriers we identified as “personal” are the result of structural forces. The use of this designation is not meant to imply that experiencing these barriers is the fault of the individual or their choices. For instance, unintended pregnancies often result from poor access to contraception, which is shaped by structural factors such as lack of insurance, medical examination requirements, and inadequate sexual health education. 58 Likewise, poverty is driven by structural forces, including lack of affordable housing and health care, discrimination, limited mental health and substance use treatment services, and domestic violence.

While other reviews have described women's perceptions of access to prenatal care in the United States., 59 this review makes several important contributions. First, we included themes related to experiences of care in addition to access. The reviewed studies showed that women continue to feel dismissed during visits and experience discrimination and abuse from providers and office staff. In particular, Black and Hispanic women reported facing a double burden of discrimination based on both race and low‐income status. Second, we included studies focused on postpartum visits, which have only recently begun to receive national health policy attention as a neglected means of improving perinatal and infant health. 6 Estimates of postpartum visit attendance vary widely by state, insurance status, and data source, from below 30% to above 90%. 54 , 60 The qualitative studies in this review revealed that low postpartum visit attendance is driven by structural issues with care delivery, competing life priorities, and disrespectful treatment by providers.

This review has a few limitations. First, because we determined that study quality was high overall, we did not distinguish themes stemming from higher or lower quality studies within the results section. In addition, we did not include studies focused on nonroutine care, such as programs providing organized group prenatal care. Our rationale was that barriers to and experiences of care would differ between these program participants and the general Medicaid population, as they may have received additional social and administrative support throughout pregnancy. This likely excluded some innovative approaches to pregnancy care that warrant research and policy attention; however, it allowed us to focus on a form of prenatal and postpartum care available to most Medicaid enrollees. 5 , 6 In the following section, we offer several targeted Medicaid policy actions to address the challenges identified by low‐income pregnant and postpartum women. Each could be implemented in the near term while broader, long‐term social policy changes are pursued, such as affordable childcare, improved public transportation, access to paid family leave, and expansion of access to pregnancy care in rural areas.

4.1. Medicaid policy actions

4.1.1. Expand presumptive eligibility

Medicaid enrollment policies continue to be a major hurdle for pregnant women seeking prenatal care. Presumptive eligibility is a Medicaid policy option that allows qualified entities, including hospitals and federally qualified health centers (FQHC), to temporarily enroll eligible pregnant women in Medicaid if they meet screening criteria. This would address the issue raised in multiple studies of women needing to go to a health clinic to receive lab work proving pregnancy before beginning the Medicaid enrollment process or booking a prenatal care appointment. A difference‐in‐difference analysis using the 2015–2018 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) data found that presumptive eligibility increased first‐trimester initiation of prenatal care and overall prenatal care use, with the largest effects on women uninsured prior to pregnancy. 61 Currently, 20 states do not provide pregnant women with presumptive eligibility for Medicaid, and within states with the policy, not all prenatal care clinics are qualified. 62 A few states, such as West Virginia, have allowed a broader range of outpatient clinics, including FQHCs, Rural Health Clinics, Free Clinics, and Community Behavioral Health Centers, to enroll as qualified presumptive eligibility providers. 63 Expanding this policy to additional states and increasing the number of presumptive eligibility providers are practical steps toward improving access to timely prenatal care for low‐income women.

4.1.2. Greater parity in state Medicaid payment rates

Reimbursement rates for low‐risk pregnancy care vary widely by state, with some states offering rates up to 20 times higher than others. 64 Studies have found an association between state Medicaid reimbursement rates and the number of prenatal visits obtained by pregnant women. 65 In addition, some research has indicated the ACA “fee bump,” which mandated a two‐year increase in fees for primary care services to Medicare levels for Medicaid fee‐for‐service and managed care, resulting in increased availability of physicians for Medicaid members. 66 This was greatest in states with the largest increases in reimbursement rates. In the qualitative studies reviewed, Medicaid‐insured women noted that finding a provider who accepts Medicaid insurance was challenging. Raising Medicaid reimbursement rates for pregnancy and postpartum visits in states that currently offer payment below the national average could encourage providers to accept a greater share of patients with Medicaid coverage.

4.1.3. Medicaid reimbursement for doula care

Medicaid reimbursement for doula care is also likely to increase prenatal and postpartum care utilization while addressing some of the quality‐of‐care issues identified in this review. A doula is a nonclinical professional who offers continuous emotional, physical, and practical support during pregnancy, labor, and the postpartum period. 67 In addition to improving clinical outcomes, women who use doula services are more likely to attend recommended prenatal and postpartum visits and report higher satisfaction. 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 As of 2021, three states were actively providing Medicaid reimbursement for doula services, and an additional eight had passed legislation, including Medicaid coverage for doula services. 72 Importantly, Medicaid reimbursement levels must be high enough to adequately compensate doulas for their time, training, and licensure costs. Analyses of Medicaid reimbursement for doula services in Oregon and Minnesota in 2012 and 2013 found that uptake was low because of inadequate reimbursement rates. 70 , 73 , 74

4.1.4. Extend pregnancy Medicaid coverage to 12 months postpartum and increase covered services

As of March 2022, in 8 expansion and 38 nonexpansion states, women with pregnancy‐Medicaid eligibility lose coverage after 60 days postpartum. 75 The Build Back Better Act (BBBA) would have begun to address this issue by requiring states to permanently extend postpartum Medicaid coverage to 1 year and allow those with incomes below 100% FPL in non‐expansion states to qualify for subsidies on the ACA Marketplace until 2025. An estimated 720,000 additional women would remain eligible through 1 year postpartum with the implementation of this policy. 76 While extending Medicaid coverage to 1 year postpartum is a critical step to ensure adequate postpartum care, we must also extend the range of postpartum services covered by Medicaid to include full assessment and treatment of physical, social, and psychological needs across multiple visits. This recommendation is in line with the 2018 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines to optimize the postpartum visit 6 ; however, progress has been slow. For example, in 2021, only 34 states and DC covered postpartum mental health screening to identify postpartum depression, and treatment beyond 60 days postpartum is rarely covered by Medicaid. 77

5. CONCLUSIONS

The qualitative studies included in this systematic review identified several barriers to high‐quality prenatal and postpartum care that are driven by current Medicaid policies and administrative hurdles. As a result, low‐income women experience delayed insurance enrollment, provider scarcity, and care interruptions. Often, these structural barriers are compounded by individual barriers to care seeking, such as limited social support and competing life priorities, as well as disrespectful or discriminatory care from providers because of insurance status, income, race, language, age, or substance use. Medicaid policy changes, including expanding presumptive eligibility, increased reimbursement rates for pregnancy services, payment for birth doula support, and extension of postpartum visit coverage, have the potential to improve access to supportive prenatal and postpartum care.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None declared.

Bellerose M, Rodriguez M, Vivier PM. A systematic review of the qualitative literature on barriers to high‐quality prenatal and postpartum care among low‐income women. Health Serv Res. 2022;57(4):775‐785. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.14008

REFERENCES

- 1. Hoyert DL. Maternal mortality rates in the United States, 2020. 2021.

- 2. Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, et al. Vital signs: pregnancy‐related deaths, United States, 2011–2015, and strategies for prevention, 13 states, 2013–2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(18):423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control . Preterm birth 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pretermbirth.htm

- 4. Kaiser Family Foundation . Births financed by Medicaid 2021;

- 5. Peahl AF, Gourevitch RA, Luo EM, et al. Right‐sizing prenatal care to meet patients' needs and improve maternity care value. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(5):1027‐1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists (ACOG) . Optimizing postpartum care. 2018. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2018/05/optimizing-postpartum-care. Accessed October 20, 2021.

- 7. Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M. Assessing the role and effectiveness of prenatal care: history, challenges, and directions for future research. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(4):306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) . Medicaid and CHIP beneficiary profile: maternal and infant health. 2020. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/downloads/mih-beneficiary-profile.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2021.

- 9. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) . Access in brief: pregnant women and Medicaid. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Pregnant-Women-and-Medicaid.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2021.

- 10. Gordon SH, Declercq E, Garrido MM. Quality of prenatal and postpartum care in affordable care act marketplaces. Pre‐publication. 2021;

- 11. Daw JR, Sommers BD. The affordable care act and access to care for reproductive‐aged and pregnant women in the United States, 2010–2016. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(4):565‐571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kaiser Family Foundation . Medicaid income eligibility limits for parents, 2002–2021. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-income-eligibility-limits-for-parents/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22January%202013%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D. Accessed October 31, 2021.

- 13. Bellerose M, Collin L, Daw JR. The ACA Medicaid expansion and perinatal insurance, health care use, and health outcomes: a systematic review. Health Aff. 2022;41(1):60‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Daw JR, Hatfield LA, Swartz K, Sommers BD. Women in the United States experience high rates of coverage ‘churn’ in months before and after childbirth. Health Aff. 2017;36(4):598‐606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gourevitch R, Peahl A, McConnell MSN, Shah N. Understanding the impact of prenatal care: improving metrics, data, and evaluation. Health Affairs Blog. 2020;

- 16. Kotelchuck M. An evaluation of the Kessner adequacy of prenatal care index and a proposed adequacy of prenatal care utilization index. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(9):1414‐1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gourevitch RA, Natwick T, Chaisson CE, Weiseth A, Shah NT. Variation in guideline‐based prenatal care in a commercially insured population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(3):413.e1‐413.e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Richardson JC, Liddle J. Where does good quality qualitative health care research get published? Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2017;18(5):515‐521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weiner BJ, Amick HR, Lund JL, Lee S‐YD, Hoff TJ. Use of qualitative methods in published health services and management research: a 10‐year review. Med Care Res Rev. 2011;68(1):3‐33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance: process and methods guide. 3rd ed. https://guides.lib.unc.edu/ld.php?content_id=30267122. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 21. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) . CASP qualitative checklist. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 22. Aved BM, Irwin MM, Cummings LS, Findeisen N. Barriers to prenatal care for low‐income women. West J Med. 1993;158(5):493‐498. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gazmararian JA, Schwarz KS, Amacker LB, Powell CL. Barriers to prenatal care among Medicaid managed care enrollees: patient and provider perceptions. HMO Pract. 1997;11(1):18‐24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Humbert L, Roberts TL. The value of a learner's stance: lessons learned from pregnant and parenting women. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(5):588‐596. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0373-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee SH, Grubbs LM. Pregnant teenagers' reasons for seeking or not seeking prenatal care. Clin Nurs Res. 1995;4(1):38‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meyer E, Hennink M, Rochat R, et al. Working towards safe motherhood: delays and barriers to prenatal Care for Women in rural and Peri‐urban areas of Georgia. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(7):1358‐1365. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-1997-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reid CN, Fryer K, Cabral N, Marshall J. Health care system barriers and facilitators to early prenatal care among diverse women in Florida. Birth. 2021;48(3):416‐427. doi: 10.1111/birt.12551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Roman LA, Raffo JE, Dertz K, et al. Understanding perspectives of African American Medicaid‐insured women on the process of perinatal care: an opportunity for systems improvement. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21:81‐92. doi: 10.1007/s10995-017-2372-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. York R, Williams P, Munro BH. Maternal factors that influence inadequate prenatal care. Public Health Nurs. 1993;10(4):241‐244. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1993.tb00059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mazul MC, Salm Ward TC, Ngui EM. Anatomy of good prenatal care: perspectives of low‐income African‐American women on barriers and facilitators to prenatal care. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(1):79‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Edmonds BT, Mogul M, Shea JA. Understanding low‐income African American women's expectations, preferences, and priorities in prenatal care. Fam Community Health. 2015;38(2):149‐157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roberts S, Pies C. Complex calculations: how drug use during pregnancy becomes a barrier to prenatal care. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(3):333‐341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Akpovi EE, Carter T, Kangovi S, Srinivas SK, Bernstein JA, Mehta PK. Medicaid member perspectives on innovation in prenatal care delivery: a call to action from pregnant people using unscheduled care. Healthcare. 2020;8(4):100456. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2020.100456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Buchberg MK, Fletcher FE, Vidrine DJ, et al. A mixed‐methods approach to understanding barriers to postpartum retention in care among low‐income, HIV‐infected women. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(3):126‐132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Handler A, Raube K, Kelley MA, Giachello A. Women's satisfaction with prenatal care settings: a focus group study. Birth. 1996;23(1):31‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nijagal MA, Patel D, Lyles C, et al. Using human centered design to identify opportunities for reducing inequities in perinatal care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):714. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06609-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roberts SC, Nuru‐Jeter A. Women's perspectives on screening for alcohol and drug use in prenatal care. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20(3):193‐200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schaffer MA, Lia‐Hoagberg B. Prenatal care among low‐income women. Fam Soc. 1994;75(3):152‐159. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang E, Glazer KB, Sofaer S, Balbierz A, Howell EA. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity: a qualitative study of Women's experiences of Peripartum care. Womens Health Issues. 2021;31(1):75‐81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wilkinson DS, González‐Calvo J. Client's perceptions of the value of prenatal psychosocial services. Soc Work Health Care. 1999;29(4):1‐12. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Henderson V, Stumbras K, Caskey R, Haider S, Rankin K, Handler A. Understanding factors associated with postpartum visit attendance and contraception choices: listening to low‐income postpartum women and health care providers. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(1):132‐143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Michels TM. “Patients like us”: pregnant and parenting teens view the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2000;115(6):557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Harville EW, Giarratano GP, Buekens P, Lang E, Wagman J. Congenital syphilis in East Baton Rouge parish, Louisiana: providers' and women's perspectives. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05753-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rodin D, Silow‐Carroll S, Cross‐Barnet C, Courtot B, Hill I. Strategies to promote postpartum visit attendance among Medicaid participants. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(9):1246‐1253. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Abrams LS, Dornig K, Curran L. Barriers to service use for postpartum depression symptoms among low‐income ethnic minority mothers in the United States. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(4):535‐551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guendelman S, Witt S. Improving access to prenatal care for Latina immigrants in California: outreach and inreach strategies. Int Q Community Health Educ. 1991;12(2):89‐106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sheppard VB, Zambrana RE, O'Malley AS. Providing health care to low‐income women: a matter of trust. Fam Pract. 2004;21(5):484‐491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Salm Ward TC, Mazul M, Ngui EM, Bridgewater FD, Harley AE. “You learn to go last”: perceptions of prenatal care experiences among African‐American women with limited incomes. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(10):1753‐1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bennett I, Switzer J, Aguirre A, Evans K, Barg F. 'Breaking it down': patient‐clinician communication and prenatal care among African American women of low and higher literacy. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(4):334‐340. doi: 10.1370/afm.548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jesse DE, Dolbier CL, Blanchard A. Barriers to seeking help and treatment suggestions for prenatal depressive symptoms: focus groups with rural low‐income women. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2008;29(1):3‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wheatley RR, Kelley MA, Peacock N, Delgado J. Women's narratives on quality in prenatal care: a multicultural perspective. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(11):1586‐1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fitzgerald EM, Cronin SN, Boccella SH. Anguish, yearning, and identity: toward a better understanding of the pregnant Hispanic woman's prenatal care experience. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;27(5):464‐470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yee LM, Simon MA. Perceptions of coercion, discrimination and other negative experiences in postpartum contraceptive counseling for low‐income minority women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(4):1387‐1400. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Author's analysis of Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) data, 2016–2020.

- 55. Dunn A, Gottlieb JD, Shapiro A, Sonnenstuhl DJ, Tebaldi P. A denial a day keeps the doctor away. 2021.

- 56. Heberlein EC, Picklesimer AH, Billings DL, Covington‐Kolb S, Farber N, Frongillo EA. Qualitative comparison of women's perspectives on the functions and benefits of group and individual prenatal care. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61(2):224‐234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Khan AA, Bhardwaj SM. Access to health care: a conceptual framework and its relevance to health care planning. Eval Health Prof. 1994;17(1):60‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Grindlay K, Grossman D. Prescription birth control access among US women at risk of unintended pregnancy. J Womens Health. 2016;25(3):249‐254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Phillippi JC. Women's perceptions of access to prenatal care in the United States: a literature review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2009;54(3):219‐225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Medicaid.gov . Prenatal and postpartum care: postpartum care. 2021. https://www.medicaid.gov/state-overviews/scorecard/postpartum-care/index.html

- 61. Eliason E, Daw J, Allen H. Access to care for pregnant women: the role of presumptive eligibility policies in Medicaid. AcademyHealth. 2021.

- 62. Kaiser Family Foundation . Presumptive eligibility in Medicaid and CHIP. 2020. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/presumptive-eligibility-in-medicaid-chip/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

- 63. West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources . Presumptive eligibility. https://dhhr.wv.gov/bms/Provider/HBPE/Pages/default.aspx

- 64. Baker MV, Butler‐Tobah YS, Famuyide AO, Theiler RN. Medicaid cost and reimbursement for low‐risk prenatal care in the United States. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2021;66(5):589‐596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sonchak L. Medicaid reimbursement, prenatal care and infant health. J Health Econ. 2015;44:10‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zuckerman S, Skopec L, Epstein M. Medicaid physician fees after the ACA primary care fee bump. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. 2017;(0.667):0.002.

- 67. Gilliland AL. Beyond holding hands: the modern role of the professional doula. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2002;31(6):762‐769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zhang J, Bernasko JW, Leybovich E, Fahs M, Hatch MC. Continuous labor support from labor attendant for primiparous women: a meta‐analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88(4):739‐744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hodnett ED, Gates S, Hofmeyr GJ, Sakala C. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7(7):CD003766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kozhimannil KB, Hardeman RR, Alarid‐Escudero F, Vogelsang CA, Blauer‐Peterson C, Howell EA. Modeling the cost‐effectiveness of doula care associated with reductions in preterm birth and cesarean delivery. Birth. 2016;43(1):20‐27. doi: 10.1111/birt.12218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Koumouitzes‐Douvia J, Carr CA. Women's perceptions of their doula support. J Perinat Educ. 2006;15(4):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. National Health Law Program . Doula medicaid project: current state doula medicaid efforts. 2021. https://healthlaw.org/doulamedicaidproject/

- 73. Chen A. Routes to success for Medicaid coverage of doula care. National Health law Program Retrieved on 2018;6(30):2019.

- 74. Kozhimannil K, Hardeman R. How Medicaid coverage for doula care could improve birth outcomes, reduce costs, and improve equity. Health Affairs. 2015;

- 75. Kaiser Family Foundation . Medicaid postpartum coverage extension tracker. 2022. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-postpartum-coverage-extension-tracker/. Accessed March 13, 2022.

- 76. Ranji U, Salganicoff A, Gomez I. Maternal health in the build back better act. 2021. https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/maternal-health-in-the-build-back-better-act/

- 77. Babbs G, McCloskey L, Gordon SH. Expanding postpartum Medicaid benefits to combat maternal mortality and morbidity. Health Affairs Forefront. 2021. 10.1377/forefront.20210111.655056 [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supporting information.