Abstract

DNA replication of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage TP901-1 was shown to involve the gene product encoded by orf13 and the repeats located within the gene. Sequence analysis of 1,500 bp of the early transcribed region of the phage genome revealed a single-stranded DNA binding protein analogue (ORF12) and the putative replication protein (ORF13). The putative origin of replication was identified as series of repeats within orf13 and was shown to confer a TP901-1 resistance phenotype when present in trans. Site-specific mutations were introduced into the replication protein and into the repeats. The mutations were introduced into the TP901-1 prophage by homologous recombination by using a vector with a temperature-sensitive replicon. Subsequent analysis of induced phages showed that the protein encoded by orf13 and the repeats within orf13 were essential for phage TP901-1 amplification. In addition, analyses of internal phage DNA replication showed that the ORF13 protein and the repeats are essential for phage TP901-1 DNA replication in vivo. These results show that orf13 encodes a replication protein and that the repeats within the gene are the origin of replication.

Strains of Lactococcus lactis are industrially important members of the lactic acid bacteria. They are commonly used as starter cultures in the production of fermented milk products, but their susceptibility to bacteriophage attack, which causes fermentation failure, continues to be a significant problem in industrial practice. This has led to a number of studies aimed at understanding the physical and genetic organization of lactococcal phages (for review, see reference 17). The interest in DNA replication of lactococcal bacteriophages has increased in recent years, since this knowledge may lead to development of new phage resistance mechanisms for lactococcal strains. So far, only a few features of the lactococcal phage origins of replication have been described. The presence of series of repeats has been identified in all lactococcal phage origins described until now. In two cases, phage c2 and sk1, these repeats were shown to be able to function as plasmid origins of replication in Lactococcus (9, 45). Another feature of the repeats is the Per (phage-encoded resistance) phenotype, which has been shown for the lactococcal phages ϕ50, ϕ31, and Tuc2009 (21, 33, 35). The Per effect is observed as resistance against phage infection of the host harboring the phage origin of replication on a plasmid in trans. Per has been suggested to function by titrating out factors required for replication of the infecting phage (21, 35). Binding of the putative replication initiation protein to the repeats of the origin has been shown for the lactococcal phage Tuc2009 (33).

In this work we investigate the biological importance of a replication protein and the origin of replication in DNA replication of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage TP901-1. The putative replication initiator protein (ORF13) and the origin of replication, identified as series of repeats within orf13, were analyzed by the introduction of site-specific mutations followed by determination of the internal phage DNA replication. The origin of replication was furthermore shown to confer Per resistance against TP901-1 infection on the indicator strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, media, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Lactococcus strains were propagated at 30°C in M17 broth (41) containing 0.5% glucose (GM17) without shaking, supplemented when necessary with antibiotics at the following concentrations: chloramphenicol at 4 μg/ml or tetracycline at 2 μg/ml. Escherichia coli strains were grown with agitation at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth (37). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: chloramphenicol at 20 μg/ml, tetracycline at 10 μg/ml or ampicillin at 100 μg/ml, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 1 mM, 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) at 40 μg/ml, and tetracycline at 12.5 μg/ml. To prepare solid or soft agar media, 1.5 or 0.7% Agar-agar (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was added. For work with phages, GM17 medium containing 5 mM CaCl2 was used.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and phages

| Strain, plasmid, or phage | Relevant feature(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Lactis subsp. cremoris strains | ||

| 901-1 | Lysogenic for bacteriophage TP901-1 | 6 |

| 901-Δ | Mutant of 901-1 produced by homologous recombination with pG8Δ | This study |

| 901-R | Mutant of 901-1 produced by homologous recombination with pG8R | This study |

| 901-A | Mutant of 901-1 produced by homologous recombination with pG8A | This study |

| 3107 | Indicator strain for phage TP901-1 | 6 |

| E. coli strains | ||

| XL1-Blue MRF′ | Transformation host | Stratagene |

| JM105 | Transformation host | 47 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCI3340 | Shuttle vector; Cmr | 19 |

| pG5f6 | EcoRV fragment 6 from TP901-1 cloned in pGEM-5Zf(−) | 11 |

| pG7f8b | EcoRI fragment 8b from TP901-1 cloned in pGEM-3Zf(+) | 11 |

| pS40H1 | pCI3340 + 269-bp HindIII fragment isolated from pG7f8b | This study |

| pS40H2 | pCI3340 + two direct repeated copies of the 269-bp HindIII fragment isolated from pG7f8b | This study |

| pS40C2 | pCI3340 + 10-kb ClaI (fragment 2) isolated from purified TP901-1 DNA | This study |

| pGEM-3Zf(+) | E. coli cloning vector; Apr | Promega |

| pG3PBX | pGEM-3Zf(+) + 3.3-kb TP901-1 with 165-bp deletion in orf13 | This study |

| pG3PIX | pGEM-3Zf(+) + 3.4-kb TP901-1 with mutations in group I repeats of orf13 | This study |

| pG3PAB | pGEM-3Zf(+) + 3.4-kb TP901-1 with an amber mutation in orf13 | This study |

| pGhost8 | Vector with a thermosensitive replicon used for homologous recombination; Tc | 31 |

| pG8Δ | pGhost8 + 3.3-kb subclone from pG3PBX | This study |

| pG8R | pGhost8 + 3.4-kb subclone from pG3PIX | This study |

| pG8A | pGhost8 + 3.4-kb subclone from pG3PAB | This study |

| pAK89 | Plasmid pCI372 with suppressor gene supD, which can suppress an amber codon with serine; Cmr | 14 |

| Bacteriophages | ||

| TP901-1 | Isolated following UV induction of L. cremoris 901-1 | This study |

| TP901-Δ | Isolated following UV induction of L. cremoris 901-Δ | This study |

| TP901-R | Isolated following UV induction of L. cremoris 901-R | This study |

| TP901-A | Isolated following UV induction of L. cremoris 901-A | This study |

Plasmids, phages, and plaque assay.

Plasmids and bacteriophages used in this study are listed in Table 1. The temperate phage TP901-1 or mutated derivatives were induced from their L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 strains by the use of UV light, as previously described (11). Phages were further purified by CsCl block gradients as described for phage λ (37). Phages were diluted in Ca2+ dilution water (137 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2) and were plated on lawns of L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107 or derivatives of this strain. The phage titer was determined as PFU per ml, based on at least three independent experiments (41). A variation for phage titers of 20% was observed. The efficiency of plaquing (EOP) was calculated by dividing the phage titer on L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107/plasmid derivatives by the titer on the indicator strain L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107/pCI3340. A variation for the EOP values of 10% was observed.

DNA technology.

DNA extraction from purified phage particles was performed as described for λ (37). Recombinant plasmid DNA from E. coli was isolated by the alkaline lysis procedure (37), and preparative samples were further purified with QIAGEN columns as recommended by the supplier (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Chromosomal DNA from lactococcal cells was prepared as described for E. coli (37), except that the cells were frozen overnight at −20°C after harvesting and were treated with lysozyme at a final concentration of 20 mg/ml for 20 min at 37°C to promote lysis. Restriction endonucleases, calf intestine alkaline phosphatase, and T4 DNA ligase were used as recommended by the supplier (New England Biolabs, Inc., Beverly, Mass.). Agarose gel electrophoresis was conducted in Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer (37). DNA restriction fragments were isolated from excised agarose gel segments with the GENE-CLEAN kit (BIO 101, Vista, Calif.). PCRs were performed in a DNA Thermal cycler using Taq DNA polymerase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Allerød, Denmark) or Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). PCR products were purified either by ethanol precipitation or by using the GFX PCR DNA purification kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Construction of plasmids used for mutational analysis.

The three constructions with site-specific mutations in the orf13 gene (Table 1; see Fig. 2) were first obtained in the E. coli vector pGEM-3Zf(+) (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and were then subcloned in the pGhost8 vector, which has a thermosensitive replicon that is functional at a permissive temperature (28°C) in L. lactis and E. coli (31). The primers used for the site-specific constructions are shown in Table 2. The pS40C2 construction was used as a PCR template in the following constructions. Construction of pG3PBX was performed by digestion of the two PCR products generated with primers 3729XbaI-2161BamH and 1996BamH-147PstI by restriction enzymes XbaI plus BamHI and BamHI plus PstI, respectively. The digested PCR products were cloned in the XbaI- and PstI-digested pGEM-3Zf(+) vector, which resulted in a new BamHI site at the site of deletion. The construction contained an in-frame deletion of 165 bp, which includes all the repeats within the orf13 gene. The XbaI-PstI fragment from pG3PBX was then subcloned in the pGhost8 vector to create pG8Δ. Construction of pG3PIX was performed by mixing the two PCR products generated with primers 3729XbaI-RepeIrev and RepeIfor-147PstI and further amplified with primer 3729XbaI-147PstI. The final product was digested with XbaI and PstI and was cloned in similarly digested pGEM-3Zf(+). The construction contains several mutations within group I repeats of the orf13 gene, which resulted in a new HpaII restriction site. The XbaI-PstI fragment from pG3PIX was further subcloned in the pGhost8 vector to create pG8R. Construction of pG3PAB was performed by digestion of the two PCR products amplified with primers 3600BamH-REPambfor and REPambrev-147PstI with BamHI plus XbaI and XbaI plus PstI, respectively. The digested PCR products were cloned in BamHI- and PstI-digested pGEM-3Zf(+) vector, which resulted in a new XbaI site at the place of mutation. The construction contained an amber codon at amino acid residue 17 in ORF13. The BamHI-PstI fragment from pG3PAB was subcloned in the pGhost8 vector to create pG8A. All constructions in the pGEM-3Zf(+) vector were subject to sequencing in order to rule out the possibility of unwanted mutations introduced by the PCRs.

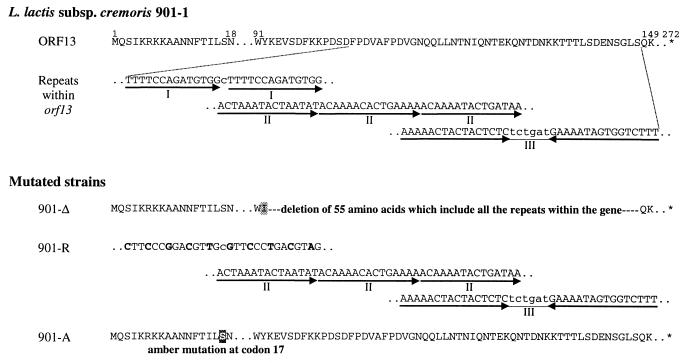

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of mutated L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 strains. Site-specific mutations introduced in the lysogenic strain L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 resulted in three mutated strains. The relevant amino acid sequence of wild-type ORF13, the two sets of direct repeats, and the inverted repeat within orf13 are shown. The mutations in the three strains are shown as follows: (i) 901-Δ, in which all the repeats including the five direct and the one inverted have been deleted in frame; (ii) 901-R, in which the group I repeat has been changed without any amino acid changes; (iii) 901-A, which contains an amber mutation at amino acid residue 17 in which the serine codon is changed to a TAG stop codon. The positions of amino acid residues in ORF13 are shown above the sequence by numbers. Dots symbolize omitted amino acids or nucleotides. The asterisks indicate stop codons.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for construction of site-specific mutations in orf13 of TP901-1

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| 3729XbaI | 5′-GGGGGTCTAGAAAAATTCGGGAAAGATATCG-3′ |

| 147PstI | 5′-Cy5-GCCAGTTTCATGTCATCACGGCC-3′ |

| 2161BamH | 5′-GGGGGGGATCCACTCTTTAACAGCTTTAGTTTCTGGG-3′ |

| 1996BamH | 5′-GGGGGGGATCCAAAGCTTTCTGACATTTATCAAG-3′ |

| RepeIrev | 5′-GTAGCTGCTGATTTCCTACGTCAGGGAACGCAACGTCCGGGAAGTCGGAATCTGGC-3′ |

| RepeIfor | 5′-GCCAGATTCCCGACTTCCCGGACGTTGCGTTCCCTGACGTAGGAAATCAGCAGCTAC-3′ |

| 3600BamH | 5′-GGGGGGGATCCGGGAAAGATATCGAAAACGAATTGCC-3′ |

| REPambfor | 5′-GCAGCGAATAACTTCACTATTCTCTAGAATGAGTTTTTACGTG-3′ |

| REPambrev | 5′-CACGTAAAAACTCATTCTAGAGAATAGTGAAGTTATTCGCTGC-3′ |

Homologous recombination by pGhost8 constructions.

The pGhost8 constructions were established in L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1, and the wild-type allele was exchanged with the plasmid-carried modified copy by homologous recombination (2) as described previously (36). L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1–pGhost8 constructions were maintained on GM17 plates with 2 μg of tetracycline/ml at a permissive temperature (28°C). The mutated lysogenic L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 strains, which all contain additional restriction sites compared to the wild-type strain, were identified by colony PCR using primers that annealed close to the mutated site. Furthermore, the selected strains were analyzed by Southern blotting by using the Enhanced chemiluminescence labeling and detection kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) to verify the introduced site-specific mutations in the prophage.

Colony PCR from L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 strains.

Two to four colonies from a single strain were resuspended in 10 μl of 0.1 M NaOH in PCR tubes. The colony mixture was incubated at 97°C for 30 min. Sterile glass beads corresponding to 3 μl were added, and the colony mixture was vortexed for 30 s. Then 1 μl of 1 M HCL and 1 μl of 1 M Tris (pH 7.5) were added and vortexed for 30 s. The mixture was left on the bench for 10 to 15 min. Subsequently, the colony mixture was incubated on ice, and 5 μl was used in a PCR.

Transformation procedure.

Transformation of E. coli was conducted essentially as described by Sambrook et al. (37). Electrotransformation of plasmid DNA into Lactococcus was performed as described by Holo and Nes (22), except that the strains were grown in the presence of 0.2 M sucrose and 1% glycine.

Isolation of intracellular phage DNA.

The method is modified according to the procedure described by Hill et al. (20). L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 strains were freshly grown to an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.25. Mitomycin C at a concentration of 3 μg/ml was added to the cultures, which were incubated at 30°C in the dark. At various times 1 ml of cells was transferred to 250 μl of ice-cold 5 M NaCl, mixed briefly and immersed for 4 s in liquid nitrogen, mixed briefly again, and harvested immediately in a cooled microcentrifuge. The pellet was resuspended in 400 μl of ice-cold lysis solution, and the remainder of the procedure followed the previous work of Hill et al. (20).

Sequencing.

DNA sequencing was conducted by using the Thermosequenase cycle sequencing kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) with custom-performed Cy-5′-labeled primers (DNA Technology, Århus, Denmark). The material was sequenced on an Alf express automatic DNA sequencer. The plasmid constructions pG5f6 and pG7f8b and deletion derivatives thereof were used as sequencing templates. Computer analyses of the sequence data were carried out with Genetics Computer Group (GCG, Madison, Wis.) software (Wisconsin Package, version 9.1) (13) or the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/blast.cgi). Homology to L. lactis subsp. lactis IL1403 was analyzed by using the website http://spock.jouy.inra.fr/.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence has been deposited in GenBank under accession number AY007566.

RESULTS

Identification of the replication region.

Transcription analysis previously performed with phage TP901-1 identified clusters of early, middle, and late transcribed genes, corresponding to similar stages of infection (30). Initiation of DNA replication is an early event in most phages. About 6.4 kb of the early transcribed region encoding orf1 to the first half of orf12 has previously been sequenced, and an additional 1,200 bp of the early region was sequenced in this work (12, 30). Analysis of the obtained sequence revealed the presence of ORF12 and ORF13, two putative protein products of open reading frames (ORFs) which could be involved in phage TP901-1 DNA replication. ORF12 and ORF13 are both preceded by a potential Shine-Dalgarno sequence complementary to the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA of L. lactis at an appropriate distance from the commonly used initiation codon ATG (29, 42).

ORF12 showed significant similarity to single-stranded DNA binding (SSB) proteins from a large variety of organisms, including both gram-positive and -negative bacteria and phages. High homology to E. coli SSB protein in the N-terminal region indicates that ORF12 may interact with single-stranded DNA in a way similar to E. coli SSB protein (10, 27). In addition, the identity between ORF12 and SSB protein from E. coli is 53% in 172 amino acids (38). This strongly suggests that ORF12 functions like an SSB protein in TP901-1 DNA replication. The role of SSB proteins in DNA replication is to stabilize single strands of DNA that are transiently formed as the replication fork moves though the double helix (32). In addition, ORF12 shows an identity of 71% in 166 amino acids to the putative SSB protein (encoded by gene ssbD) from L. lactis subsp. lactis IL1403 (3) and was nearly identical to ORF15 encoded by the lactococcal phage Tuc2009 (33).

The deduced protein product of ORF13 showed significant homology to only eight ORFs from different sources, such as phages, plasmids, or bacterial genomes (Table 3), but no biological data are available on any of these ORFs (3, 4, 16, 18, 24, 25, 28, 34). Besides this, ORF13 shows homology, although less significant, to two protein products which have been proven to be involved in DNA replication. One is the DnaD protein from Bacillus subtilis, which has an unknown function in initiation of chromosomal DNA replication (7), and the other is a protein encoded by the replication origin, ori60, of a large plasmid from Bacillus thuringiensis, which seems to be involved in plasmid replication (1).

TABLE 3.

Similarities observed by database searches with ORF13 of TP901-1

| ORF protein homologues with ORF13 | % Identitya | Probabilityb | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. lactis SMQ-86 and phage ul36.1 ORF235 | 33 (168) | 2 × 10−13 | 4 |

| L. lactis phage ϕ31.1 ORF269 | 33 (168) | 2 × 10−13 | 16 |

| Enterococcus faecalis ORF13 | 33 (150) | 2 × 10−12 | 18 |

| Staphylococcus aureus phage ϕPVL ORF46 | 25 (154) | 5 × 10−6 | 25 |

| L. lactis IL1403 (gene dnaD) | 28 (91) | 5 × 10−6 | 3 |

| Listeria monocytogenes phage A118 ORF49 | 26 (152) | 1 × 10−5 | 28 |

| Bacillus anthracis plasmid pX01 ORF pX01-89 | 29 (74) | 9 × 10−5 | 34 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes ORF1 | 27 (129) | 2 × 10−4 | 24 |

| B. thuringiensis 60-MDa plasmid ORF ori60 | 24 (200) | 0.016 | 1 |

| B. subtilis DnaD | 29 (111) | 0.080 | 7 |

The number of amino acids over which the percentage match was determined is shown in parentheses.

The probability is derived from BLASTP score and show the probability that the observed similarity had occurred by chance.

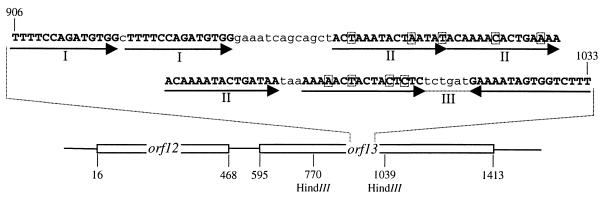

A characteristic feature of iteron-regulated origins of replication is the presence of a series of repeats to which an origin-specific protein binds (5). Analysis of the nucleotide sequence revealed two sets of direct repeats and one inverted repeat located within the orf13 gene, as shown in Fig. 1. The direct repeats in group I are fully conserved repeats of 14 bp, while the direct repeats in group II are repeats of 15 bp which have 3, 2, and no deviations from their consensus. The inverted repeat has, out of 16 bp, 4 that deviate from the consensus. Another feature of replication origins is the presence of a nearby AT-rich region, which is the site of duplex opening prior to recruitment of the replication machinery (5). The A+T contents of Lactococcus phage genomes are approximately 64%, which is similar to that of the lactococcal host (26, 39, 43). Analysis of the nucleotide sequence on each site of the repeats showed that the upstream region has an A+T content of 63%, while the downstream region has an A+T content of 71%. Thus the downstream region could be a potential site for duplex opening.

FIG. 1.

Diagram showing the repeats identified within orf13. The putative origin of replication identified within orf13 comprises two sets of direct repeats and one inverted repeat indicated by capitalized bases and arrows below the sequence. The direct repeats in group I are fully conserved, while the direct repeats in group II and the inverted repeat have few deviations, as indicated by boxes. The numbers indicate the base pair positions according to the sequence deposited in GenBank (accession number A4007566).

In conclusion, the observed features of the analyzed sequence strongly indicate that the origin of replication in phage TP901-1 is located within orf13 and that the gene products encoded by orf12 and orf13 are involved in phage DNA replication.

Phage TP901-1 resistance conferred by the repeats.

Phage origins of replication have previously been shown to confer phage resistance when present on a plasmid in trans. The effect is believed to reflect titration of phage replication factors by the plasmid-carried origin, thus inhibiting proliferation of the phage within the host (21, 33, 35). The putative TP901-1 origin of replication contained on a 269-bp HindIII fragment (Fig. 1) was cloned in the pCI3340 vector in one or two copies to create pS40H1 or pS40H2, respectively. Sequence analysis showed that the two copies in pS40H2 were directly repeated. The plasmid constructions and the control plasmid pCI3340 were introduced into L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107 by electroporation, using the chloramphenicol resistance (Cmr) marker for selection. The presence of the plasmids in Cmr L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107 strains was confirmed by plasmid profile analysis (data not shown).

Infection of L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107 and of derivative strains by phage TP901-1 was analyzed by standard plaque assays. The presence of the cloning vector pCI3340 had no effect on phage TP901-1 infection of L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107. The presence of pS40H1 or pS40H2 with one or two copies of the repeats reduced the EOP to 0.6 or 0.2, respectively. An even more pronounced effect was observed on plaque morphology, where the presence of pS40H1 resulted in wild-type and small plaques, whereas the presence of pS40H2 with two copies of the repeats resulted in plaques of pinpoint size. Thus the presence of additional repeats in the indicator strain L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107 influences the proliferation of phage TP901-1, which could be due to the titration of phage-specific protein or proteins by binding to the repeats.

Construction of mutated TP901-1 phages.

To analyze the importance of the gene product of orf13 and the repeats within the gene in phage TP901-1 DNA replication, site-specific mutations were introduced in the lysogenic strain L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1. The mutations were introduced by replacement of a prophage gene by a plasmid-carried modified copy by homologous recombination using the pGhost8 vector system (2, 31).

Three lysogenic L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 strains containing different mutations in the TP901-1 prophage genome were constructed (Fig. 2). The 901-Δ strain contains an in-frame deletion of 165 bp within orf13, which includes the two groups of direct repeats and the inverted repeat that is the putative origin of replication. Strain 901-R has been changed in the fully conserved direct repeats in group I without any change at the amino acid level. In strain 901-A, an amber stop codon was introduced at amino acid residue 17 in orf13 by changing the codon serine (AGC) to a TAG stop codon.

The plasmid constructions used for creation of the three strains by homologous recombination were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Mutated L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 strains were identified by colony PCR using primers that annealed close to the mutated site. The 901-Δ strain resulted in a PCR product 165 bp shorter than the wild type, while the 901-R and 901-A strains gave PCR products that contained a new restriction enzyme site, compared to the wild type (data not shown). The mutated lysogenic L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 strains, which all contain additional restriction sites compared to the wild-type strain, were further analyzed by Southern blotting in order to verify the introduced specific mutation(s) in the prophage (data not shown). The Southern blot analyses verified the results obtained by colony PCR, and no unexpected differences between the wild-type and mutated strains were found.

Induction of mutated L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 strains.

In order to examine the effect of introduced mutations on phage liberation, the three mutated lysogenic L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 strains and the wild-type strain were induced by UV light. All strains were induced under the same conditions, and phage titers were determined on the indicator strain L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107 (Table 4). The number of phages released from strain 901-A, which contains an amber mutation in ORF13, was furthermore examined in the presence of the amber suppressor plasmid pAK89. This plasmid expresses a mutated tRNAser gene which enables the tRNAser to recognize an amber codon as a sense codon for serine, thus suppressing the nonsense mutation (14).

TABLE 4.

Titration by UV-induced phages on indicator strains

| Induced phage | Titer (PFU/ml) for L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107 | Titer (PFU/ml) for L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107/pAK89 |

|---|---|---|

| TP901-1 | 2 × 109 | 1 × 109 |

| TP901-Δ | 2 × 103 | |

| TP901-R | 3 × 104 | |

| TP901-A | 2 × 103 | 2 × 106 |

| TP901-A induced in the presence of pAK89a | 2 × 103 | 1 × 108 |

pAK89 plasmid contains the amber suppressor gene supD (14).

The plaque assays (Table 4) showed that the phage titers on L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107 were reduced 105- to 106-fold, compared to the wild-type situation when the TP901-1 prophage contains (i) an in-frame deletion in orf13 (TP901-Δ), (ii) changes in group I repeats within orf13 (TP901-R), or (iii) an amber mutation in orf13 (TP901-A). This indicates that the repeats within orf13 and the protein encoded by orf13 are essential for amplification of phage TP901-1.

The conditional mutation in TP901-A was furthermore studied at permissive conditions by the presence of the suppressor plasmid (Table 4). When TP901-A was induced in the presence of the suppressor but was assayed in the absence of the suppressor, the phage titer was about 103. However, when these TP901-A phages were assayed on the indicator strain in the presence of the suppressor plasmid, the phage titer was 108, which is only 10-fold lower than the titer obtained in the wild-type situation but with pinpoint-sized plaques. This shows that the introduced amber mutation in orf13 can be suppressed and that the gene product of orf13 is essential for phage TP901-1 proliferation in both host and indicator strains. When TP901-A was induced and assayed without the presence of the suppressor, a phage titer of 103 was obtained. Surprisingly, when these TP901-A phages were assayed in the presence of the suppressor plasmid, the phage titer increased 103-fold, which indicates leakiness of the amber mutation in the host strain. These plaques were smaller than pinpoints, meaning that they were only visible at high concentrations.

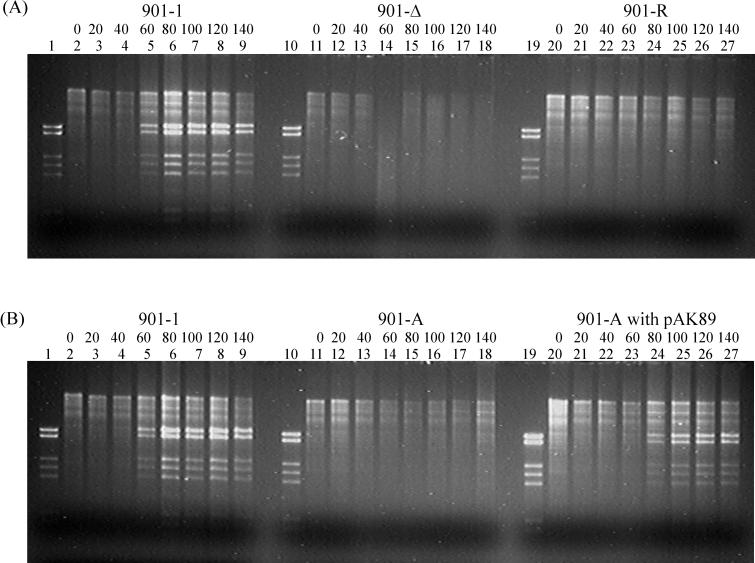

Analysis of the internal replication by mutated phages.

To investigate whether the introduced mutations in the orf13 gene influence phage TP901-1 DNA replication, intracellular phage DNA replication of wild-type and mutated TP901-1 phages was examined. Total DNA was isolated from lysogenic L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 strains at 20-min intervals after the addition of 3 μg of mitomycin C/ml, which is known to induce phage TP901-1 liberation. The isolated DNA was digested with PstI and was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, as shown in Fig. 3. The analysis clearly shows phage DNA replication by the wild-type TP901-1 phage (Fig. 3A and B, lanes 2 to 9); in contrast, DNA replication by any of the mutated TP901-1 phages was not visible (Fig. 3A, lanes 11 to 18 and 20 to 27, and B, lanes 11 to 18). However, in the presence of the suppressor plasmid in strain 901-A, phage DNA replication was unmistakably visible (Fig. 3B, lanes 20 to 27). These results strongly indicate that the protein encoded by orf13 and the repeats within orf13 are essential for phage TP901-1 DNA replication.

FIG. 3.

Internal DNA replication of wild-type and mutated TP901-1 phages in L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1. Lysogenic strains were induced by the addition of mitomycin C at time zero, and total DNA was isolated at 20-min intervals. All DNA was digested by PstI. (A) Lanes: 1, 10, and 19, purified TP901-1 DNA; 2 to 9, total DNA from L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 from time zero to 140 min; 11 to 18, total DNA from L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-Δ from time zero to 140 min; 20 to 27, total DNA from L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-R from time zero to 140 min. (B) Lanes: 1, 10, and 19, purified TP901-1 DNA; 2 to 9, total DNA from L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 from time zero to 140 min; 11 to 18, total DNA from L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-A from time zero to 140 min; 20 to 27, total DNA from L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-A in the presence of the suppressor plasmid pAK89 from time zero to 140 min.

DISCUSSION

In this work DNA replication of the lactococcal temperate phage TP901-1 was studied. By mutational analysis the gene product encoded by orf13 and the repeats located within the gene were shown to be essential for in vivo phage replication. The use of prophage-carried mutations, including nonsense mutation, to investigate DNA replication of phages infecting lactic acid bacteria has not been reported previously.

A Per phenotype was observed for the repeats identified within orf13 of phage TP901-1. Similar results were obtained with the lactococcal phages ϕ50 and ϕ31, but a more severe Per phenotype was observed with these phages when the copy number of the plasmid carrier was increased (21, 35). Unfortunately, no high-copy-number vector was found compatible with the natural resident plasmids of the indicator strain L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107. Thus, the plasmid copy number effect could not be examined for phage TP901-1; however, the presence of two copies of the repeats clearly had a stronger effect both on EOP and plaque morphology than did one copy. The Per effect has been suggested to function by titrating out factors required for replication, thus retarding replication of the infecting phage genome (21). This was emphasized by the observation that no internal phage ϕ31 DNA replication took place when the ϕ31 origin was present on a high-copy-number vector in trans (35). In conclusion, the Per phenotype observed by the repeats identified in phage TP901-1 indicates that they are the origin of replication.

By mutational analysis we further investigated the repeats and observed that deletion of all the repeats within orf13 or alterations of the group I repeats both strongly reduced phage TP901-1 amplification. In addition, no internal phage TP901-1 DNA replication took place in these mutated strains, compared to the wild type in which phage DNA replication was clearly visible (Fig. 3A). This shows that the repeats within orf13, particularly the group I repeats, are important for phage TP901-1 DNA replication, which, together with the Per phenotype of the repeats, strongly indicates that this series of repeats functions as the origin of replication in phage TP901-1.

The TP901-Δ mutant in which all the repeats have been deleted should be regarded as a double mutant, since the lack of 55 central amino acid residues could be important for correct folding and function of the protein product, in addition to the lack of all the repeats. For this reason an amber mutation was introduced in the beginning of the orf13 gene, which would result in premature translation termination and, thus, an inactive ORF13 protein product but would retain functional repeats. Furthermore, it was possible to analyze the amber mutant under permissive conditions in the presence of a nonsense suppressor. Analyses showed that when induced and assayed under nonpermissive conditions, the TP901-A phage titer was heavily reduced (Table 4). However, when these phages were assayed under permissive conditions, a higher phage titer was observed, indicating leakiness of the amber phenotype. This leakiness may be explained by (i) the presence of a natural suppressor in the lysogenic strain L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1, (ii) a very low frequency of readthrough of the amber mutation, or (iii) the presence of a second protein which can substitute for the ORF13 protein, although not very efficiently. The first two explanations are most likely, since leakiness was observed with other amber mutated TP901-1 prophages mutagenized in structural genes (36). More importantly, the results obtained when the amber mutant was induced in the presence of the suppressor clearly showed the importance of ORF13 protein function, since a significant increase in phage titer was observed when assayed under permissive conditions compared to nonpermissive conditions (Table 4). Thus the introduced stop codon in the orf13 gene and the subsequent lack of ORF13 protein function inhibit TP901-1 proliferation on the indicator strain L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107. The importance of ORF13 protein in phage TP901-1 DNA replication was demonstrated by internal phage DNA replication at almost the same intensity during permissive conditions as the wild type, whereas no DNA replication was seen under nonpermissive conditions (Fig. 3B). This shows that suppression of the amber mutation in orf13 restores phage TP901-1 DNA replication and that the ORF13 protein product in vivo is essential for phage TP901-1 DNA replication.

Our results show that the orf13 gene encodes a replication protein of phage TP901-1 and that the repeats within the gene are the origin of replication. This further indicates that ORF13 could be the replication initiator protein, which would initiate assembly of a replication complex in phage TP901-1 by binding to the repeats as previously shown in other phage systems, such as the well-studied E. coli λ phage (15, 40).

The significant homologies to SSB proteins by ORF12 strongly suggest that it functions like an SSB protein in phage TP901-1 DNA replication. A possible role of phage SSB proteins in phage DNA replication is that they assist in proper assembling of replication complexes at the phage origin (8) or prevent degradation of replicative intermediates by nucleases (46). The latter was shown to be the case for E. coli T4 phage, where E. coli SSB cannot substitute for T4 SSB in phage DNA replication. This may be explained by the fact that E. coli SSB protein is a tetramer composed of four identical subunits, while T4 SSB protein is a monomer (10, 46). Another important function of SSB proteins is their ability to melt out double-helical hairpin structures in the ssDNA template, which enhances the rate of synthesis by the polymerase (23). Finally, it could be envisaged that phage SSB proteins are required for transition from theta (θ) to rolling circle (ς) replication, which takes place in some phages.

The lactococcal phages TP901-1 and Tuc2009 encode highly similar SSB proteins located upstream of the putative replication initiator proteins of the phages, which on the other hand show no similarity to each other. Even though functional similarities have been observed in phage replication systems, only a few homologous replication initiator proteins and origins have been identified. Thus, the initiation of phage DNA replication seems to have differentiated during evolution to be specific for each phage genome. Furthermore, most phages only encode one or two additional replication proteins (44), indicating that DNA replication of phage genomes is highly dependent on the DNA replication machinery of the host. In contrast to initiation of phage DNA replication, it seems likely that phages infecting the same species may retrieve host replication proteins by homologous proteins. In the early transcribed region of many lactococcal phages, highly homologous ORFs with, so far, unidentified functions are located. These ORFs could be involved in retrieving the host replication machinery. A putative common mechanism for retrieving the host replication machinery may be a potential target for development of new phage resistance mechanisms in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank E. Johansen, Chr. Hansen A/S, for providing the nonsense suppressor plasmid pAK89.

This work was supported by FØTEK, the Danish Governmental Research Program for Food Science and Technology, through The Center for Advanced Food Studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baum J A, Gilbert M P. Characterization and comparative sequence analysis of replication origins from three large Bacillus thuringiensis plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5280–5289. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5280-5289.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biswas I, Gruss A, Ehrlich S D, Maguin E. High-efficiency gene inactivation and replacement system for gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3628–3635. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3628-3635.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolotin A, Mauger S, Malarme K, Ehrlich S D, Sorokin A. Low-redundancy sequencing of the entire Lactococcus lactis IL1403 genome. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:27–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouchard J D, Moineau S. Homologous recombination between a lactococcal bacteriophage and the chromosome of its host strain. Virology. 2000;270:65–75. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bramhill D, Kornberg A. A model for initiation at origins of DNA replication. Cell. 1988;54:915–918. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun V, Jr, Hertwig S, Neve H, Geis A, Teuber M. Taxonomic differentiation of bacteriophages of Lactococcus lactis by electron microscopy, DNA-DNA hybridization, and protein profiles. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:2551–2560. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruand C, Sorokin A, Serror P, Ehrlich S D. Nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus subtilis dnaD gene. Microbiology. 1995;141:321–322. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-2-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke R L, Alberts B M, Hosoda J. Proteolytic removal of the COOH terminus of the T4 gene 32 helix-destabilizing protein alters the T4 in vitro replication complex. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:11484–11493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandry P S, Moore S C, Boyce J D, Davidson B E, Hillier A J. Analysis of the DNA sequence, gene expression, origin of replication and modular structure of the Lactococcus lactis lytic bacteriophage sk1. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:49–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5491926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chase J W, Williams K R. Single-stranded DNA binding proteins required for DNA replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:103–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.000535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christiansen B, Johnsen M G, Stenby E, Vogensen F K, Hammer K. Characterization of the lactococcal temperate phage TP901–1 and its site-specific integration. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1069–1076. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.4.1069-1076.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christiansen B, Brøndsted L, Vogensen F K, Hammer K. A resolvase-like protein is required for the site-specific integration of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage TP901–1. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5164–5173. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5164-5173.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickely F, Nilsson D, Hansen E B, Johansen E. Isolation of Lactococcus lactis nonsense suppressors and construction of a food-grade cloning vector. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:839–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodson M, McMacken R, Echols H. Specialized nucleoprotein structures at the origin of replication of bacteriophage λ. Protein association and disassociation reactions responsible for localized initiation of replication. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:10719–10725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durmaz E, Klaenhammer T R. Genetic analysis of chromosomal regions of Lactococcus lactis acquired by recombinant lytic phages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:895–903. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.3.895-903.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forde A, Fitzgerald G F. Bacteriophage defence systems in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:89–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garnier F, Taourit S, Glaser P, Courvalin P, Galimand M. Characterization of transposon Tn/549, conferring VanB-type resistance in Enterococcus spp. Microbiology. 2000;146:1481–1489. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-6-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayes F, Daly C, Fitzgerald G F. Identification of the minimal replication of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis UC317 plasmid pC1305. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:202–209. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.1.202-209.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill C, Massey I J, Klaenhammer T R. Rapid method to characterize lactococcal bacteriophage genomes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:283–288. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.283-288.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill C, Miller L A, Klaenhammer T R. Cloning, expression, and sequence determination of a bacteriophage fragment encoding bacteriophage resistance in Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6419–6426. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6419-6426.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holo H, Nes I F. High-frequency transformation, by electroporation, of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris grown with glycine in osmotically stabilized media. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:3119–3123. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.12.3119-3123.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang C C, Hearst J E. Pauses at positions of secondary structure during in vitro replication of single-stranded fd bacteriophage DNA by T4 DNA polymerase. Anal Biochem. 1980;103:127–139. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inagaki Y, Myouga F, Kawabata H, Yamai S, Watanabe H. Genomic differences in Streptococcus pyogenes serotype M3 between recent isolates associated with toxic shock-like syndrome and past clinical isolates. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:975–983. doi: 10.1086/315299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaneko J, Kimura T, Narita S, Tomita T, Kamio Y. Complete nucleotide sequence and molecular characterization of the temperate staphylococcal bacteriophage ϕPVL carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes. Gene. 1998;215:57–67. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilpper-Bälz R, Fischer G, Schleifer K H. Nucleic acid hybridization of group N and group D streptococci. Curr Microbiol. 1982;7:245–250. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinebuchi T, Shindo H, Nagai H, Shimamoto N, Shimizu M. Functional domains of Escherichia coli single-stranded DNA binding protein as assessed by analyses of the deletion mutants. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6732–6738. doi: 10.1021/bi961647s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loessner M J, Inman R B, Lauer P, Calendar R. Complete nucleotide sequence, molecular analysis and genome structure of bacteriophage A118 of Listeria monocytogenes: implications for phage evolution. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:324–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludwig W, Seewaldt E, Kilpper-Bälz R, Schleifer K H, Magrum L, Woese C R, Fox G E, Stackebrandt E. The phylogenetic position of Streptococcus and Enterococcus. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:543–551. doi: 10.1099/00221287-131-3-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madsen P L, Hammer K. Temporal transcription of the lactococcal temperate phage TP901–1 and DNA sequence of the early promoter region. Microbiology. 1998;144:2203–2215. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-8-2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maguin E, Prévots H, Ehrlich S D, Gruss A. Efficient insertional mutagenesis in lactococci and other gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:931–935. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.931-935.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marians K J. Prokaryotic DNA replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:673–719. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.003325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGrath S, Seegers J F M L, Fitzgerald G F, van Sinderen D. Molecular characterization of a phage-encoded resistance system in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1891–1899. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.1891-1899.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okinaka R T, Cloud K, Hampton O, Hoffmaster A R, Hill K K, Keim P, Koehler T M, Lamke G, Kumano S, Mahillon J, Manter D, Martinez Y, Ricke D, Svensson R, Jackson P. Sequence and organization of pX01, the large Bacillus anthracis plasmid harboring the anthrax toxin genes. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6509–6515. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6509-6515.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Sullivan D J, Hill C, Klaenhammer T R. Effect of increasing the copy number of bacteriophage origins of replication, in trans, on incoming-phage proliferation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2449–2456. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2449-2456.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pedersen M, Østergaard S, Bresciani J, Vogensen F K. Mutational analysis of two structural genes of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage TP901–1 involved in tail length determination and baseplate assembly. Virology. 2000;276:315–328. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sancar A, Williams K R, Chase J W, Rupp W D. Sequences of the ssb gene and protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:4274–4278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schouler C, Ehrlich S D, Chopin M-C. Sequence and organization of the lactococcal prolate-headed bIL67 phage genome. Microbiology. 1994;140:3061–3069. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-11-3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor K, Wegrzyn G. Replication of coliphage lambda DNA. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1995;17:109–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1995.tb00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terzaghi B E, Sandine W E. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl Microbiol. 1975;29:807–813. doi: 10.1128/am.29.6.807-813.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van de Guchte M, Kok J, Venema G. Gene expression in Lactococcus lactis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;88:73–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb04958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Sinderen D, Karsens H, Kok J, Terpstra P, Ruiters M H J, Venema G, Nauta A. Sequence analysis and molecular characterization of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage rlt. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1343–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venema G, Kok J, van Sinderen D. From DNA sequence to application: possibilities and complications. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:3–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waterfield N R, Lubbers M W, Polzin K M, Le Page R W F, Jarvis A W. An origin of DNA replication from Lactococcus lactis bacteriophage c2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1452–1453. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.4.1452-1453.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu J R, Yeh Y C. Requirement of a functional gene 32 product of bacteriophage T4 in UV repair. J Virol. 1973;12:758–765. doi: 10.1128/jvi.12.4.758-765.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]