Abstract

Bacterial biofilms are structured clusters of bacterial cells enclosed in a self-produced polymer matrix that are attached to a biotic or abiotic surface. This structure protects bacteria from hostile environmental conditions. There are also accumulating reports about bacterial aggregates associated but not directly adherent to surfaces. Interestingly, these bacterial aggregates exhibit many of the same phenotypes as surface-attached biofilms. Surface-attached biofilms as well as non-attached aggregates are ubiquitous and found in a wide variety of natural and clinical settings. This strongly suggests that biofilm/aggregate formation is important at some steps in the bacterial lifecycle. Biofilm/aggregate formation might therefore be important for some bacterial species for persistence within their host or their environment, while for other bacterial species it might be more important for persistence in the environment between infection of different individuals or even between infection of different hosts (humans or animals). This is strikingly similar to the One Health concept which recognizes that the health and well-being of humans, animals and the environment are intricately linked. We would like to propose that within this One Health concept, the One Biofilm concept also exists, where biofilm/aggregate formation in humans, animals and the environment are also intricately linked. Biofilm/aggregates could represent the unifying factor underneath the One Health concept. The One Biofilm concept would support that biofilm/aggregate formation might be important for persistence during infection but might as well be even more important for persistence in the environment and for transmission between different individuals/different hosts.

Keywords: Biofilms, bacterial aggregates, One Health

1. Bacterial biofilms

Bacterial biofilms are structured clusters of bacterial cells enclosed in a self-produced polymer matrix, attached to a biotic or abiotic surface [1]. This structure protects bacteria from hostile environmental conditions and guarantees the survival and spread of these communities. Bacteria in biofilms are more resistant/tolerant to antibiotics and disinfectants than planktonic cells and can withstand attacks from the host immune system [1, 2]. Although in vitro studies have focused mainly on single-species biofilms, multispecies biofilms are predominant in the context of host colonization and environmental conditions [3–5].

Intensive efforts are directed towards the development of new anti-biofilm molecules or strategies. The most frequent approaches that are currently investigated are blocking bacterial adhesion, killing persister cells, interfering with bacterial communication, inhibiting bacterial cooperation, degrading the polymeric matrix and stimulating dispersal of biofilms [6–9].

Cai [10] recently proposed that, in addition to the two main lifestyles (i.e., planktonic individuals and surface-attached biofilms), non-surface attached bacterial aggregates represent a third lifestyle. There are indeed accumulating reports in medical literature indicating that while some biofilms adhere to natural surfaces or artificial devices in the host, others may consist of bacterial aggregates that are not directly adherent to surfaces [11]. A characterization of biofilms associated with chronic infections in humans (e.g., lung infections, otitis media, osteomyelitis) revealed the presence of microbial cells aggregates ranging from ~5 to 200 µm in diameter [12]. These bacterial aggregates, interestingly, share many of the same characteristics as surface-attached biofilms, such as increased antibiotic resistance/tolerance [13]. Aggregates were also observed in animals such as in the lungs of pigs infected with Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae [14] and the mammary gland of cows infected with Staphylococcus aureus (I. Doghri, S. Dufour and M. Jacques, unpublished data). Furthermore, bacterial aggregates and biofilms are not mutually exclusive. Salmonella forms aggregates in conditions of biofilm formation, separate from the population that sticks to the solid surface at the air–liquid interface [15].

Surface-attached biofilms as well as non-attached aggregates are ubiquitous and found in a wide variety of natural environments (e.g., marine, freshwater and wastewater) and clinical situations (human and animal infections). Over the years, studies of bacterial genomes have documented the presence of a plethora of genes (sometimes even showing redundancy) involved in biofilm formation (e.g., for biosynthesis of polymeric matrix components [16]) as well as for biofilm regulation and modulation (e.g., quorum sensing, stringent response, and c-di-GMP signaling [17]). The fact that the huge and energy-consuming machinery necessary for matrix synthesis is present in many, if not all, genomes, and that these genes were conserved through evolution, strongly suggest that biofilm/aggregate formation is critical at certain steps in the bacterial lifecycle. For example, staphylococci produce one dominant extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) named polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA) which production is mediated by the ica locus [18]. PIA and the ica locus were first described in Staphylococcus epidermidis but then also found in Staphylococcus aureus and other staphylococcal species with significant conservation [18]. Another illustration is the extracellular matrix of drar-positive cells in Salmonella that is comprised of protein polymers (curli fimbriae) and EPS (cellulose and an O-antigen capsule) [15]. The genes coding for these polymers are conserved throughout Salmonella and Escherichia coli [15].

Biofilm/aggregate formation, on the other hand, does not necessarily represent a virulence factor, but could rather be seen as a valuable asset for pathogenic bacteria’s persitence within a host during infection or between hosts. Moreover, the ability to produce large amounts of biofilms does not necessarily correlates with virulence. For example, our group has observed that non-virulent strains of Glaesserella (Haemophilus) parasuis, a porcine pathogen, have the ability to form robust biofilms in vitro in contrast to virulent, systemic strains [19]. Biofilm formation might therefore allow the non-virulent G. parasuis strains to colonize and persist in the upper respiratory tract of pigs. Conversely, the planktonic state of the virulent strains might allow them to disseminate within the host [19]. Hence, biofilm/aggregate formation might therefore be vital for persistence of some bacterial species within their host or environment, while it may have a more significant role in the ability of others to persist between infections of different individuals or hosts (humans or animals).

2. Similarities with the One Health concept

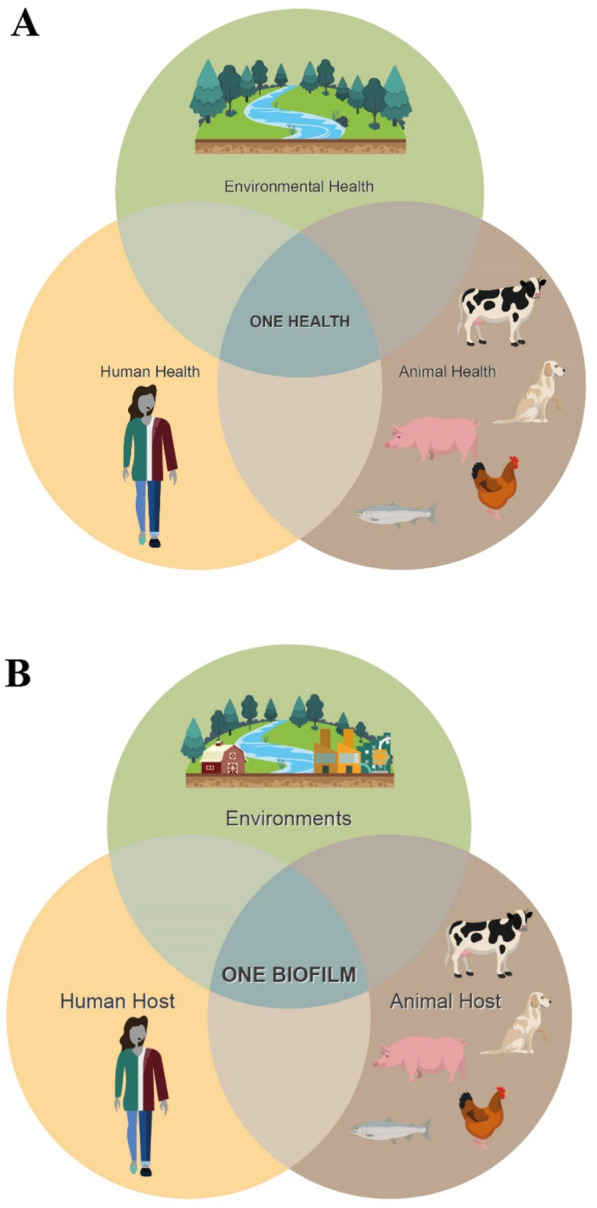

Although several definitions exist for the One Health concept, the main point is awareness that the health and well-being of humans, animals (domestic and wild), and the environment are inextricably linked (Figure 1A) [20]. One Health also represents a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach to address health threats at the human-animal-environment interface [20, 21]. The success of the One Health approach requires breaking down the barriers that still often separate human and veterinary medicine from ecological, evolutionary and environmental sciences [22] as well as socioeconomic and social policies. The One Health approach has been proven to be effective to tackle complex public health problems such as zoonotic diseases, antimicrobial resistance, food safety and food security, and other health threats shared by people, animals, and the environment such as pollution and climate changes [20]. For example, zoonoses (caused by pathogens such as Salmonella, Campylobacter, Listeria, and E. coli) are commonly spread at the human-animal-environment interface, where people and animals interact with each other in their shared environment [21, 23]. Zoonotic diseases can be foodborne, waterborne, vector-borne, or transmitted through direct contact with animals, indirectly by fomites or environmental contamination.

Figure 1.

The One Health and One Biofilm concepts. A The One Health triad shows that the health of people, animals, and the environment are intricately linked. B Similarly, the One Biofilm triad proposes that bacterial biofilm/aggregate formation in humans, animals and the environments (e.g., natural environments but also farms, slaughterhouse or food-processing plants, and hospital settings) are also intricately linked.

Similarly, biofilm/aggregate formation in humans, animals (domestic and wild), and the environment are probably also intricately linked, and we would like to propose the One Biofilm concept (Figure 1B). As such, the One Biofilm concept could be the cornerstone underlying the One Health concept. Biofilm formation is widespread among the microbial world and biosynthesis genes for biofilm production are present in most bacterial genomes. Biofilms can easily be evidenced, for multiple bacterial species, in the laboratory using in vitro assays (e.g., microtiter plates and flowcells). As indicated before, those facts strongly suggest that biofilm/aggregate formation is crucial at some steps in the bacterial lifecycle. The One Biofilm concept therefore supposes that biofilm/aggregate formation might be important for persistence during infection but might as well be even more important for persistence outside the host, in diverse environments (e.g., water, soil, surfaces at the farm, slaughterhouse or food-processing plants, hospital settings) and for transmission between different individuals and/or different hosts. We may not always understand (or have not discovered yet) where the biofilm is most important (i.e., which lifecycle stages). The One Biofilm concept is adding another layer of complexity to the One Health concept. A collaborative, multi-stakeholder, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach is therefore preferred to address complex problems involving biofilms or bacterial aggregates including the development of new and effective strategies to prevent or control their formation and to prevent persistence and spread of microbial pathogens across environments, animals and people. The One Biofilm concept is a proposition and we would invite researchers to build on the present proposition and to add observations to further strengthen and refine this new concept.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Aida Minguez Menendez for artwork and also Ibtissem Doghri, and Christopher Fernandez Prada, for discussion during the preparation of the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

MJ first formulated the One Biofilm concept. MJ and FM wrote this opinion paper. Both the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors wish to thank the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC; Discovery Grant and CREATE Grant programs), the Fonds de Recherche du Québec—Nature et technologies (FRQNT; Projet de Recherche en Équipe et Programme des Regroupements Stratégiques) and the Dairy Reaserch Clusters (Dairy Farmers of Canada, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Canadian Dairy Network, Canadian Dairy Commission) for research funding.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jacques M, Aragon V, Tremblay YD. Biofilm formation in bacterial pathogens of veterinary importance. Anim Health Res Rev. 2010;11:97–121. doi: 10.1017/S1466252310000149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hathroubi S, Mekni MA, Domenico P, Nguyen D, Jacques M. Biofilms: microbial shelters against antibiotics. Microb Drug Resist. 2017;23:147–156. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2016.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elias S, Banin E. Multi-species biofilms: living with friendly neighbors. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36:990–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burmølle M, Ren D, Bjarnsholt T, Sørensen SJ. Interactions in multispecies biofilms: do they actually matter? Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Røder HL, Olsen NMC, Whiteley M, Burmølle M. Unravelling interspecies interactions across heterogeneities in complex biofilm communities. Environ Microbiol. 2020;22:5–16. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beloin C, Renard S, Ghigho JM, Lebeaux D. Novel approaches to combat bacterial biofilms. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2014;18:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dieltjens L, Appermans K, Lissens M, Lories B, Kim W, Van der Eycken E, Foster KR, Steenackers HP. Inhibiting bacterial cooperation is an evolutionarily robust anti-biofilm strategy. Nat Commun. 2020;11:107. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13660-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart PS. Prospects for anti-biofilm pharmaceuticals. Pharmaceuticals. 2015;8:504–511. doi: 10.3390/ph8030504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verderosa AD, Totsika M, Fairfull-Smith KE. Bacterial biofilm eradication agents: a current review. Front Chem. 2019;7:824. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2019.00824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai YM. Non-surface attached bacterial aggregates: a ubiquitous third lifestyle. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:557035. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.557035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoiby N, Bjarnsholt T, Moser C, Bassi GL, Coenye T, Donelli G, Hall-Stoodley L, Hola V, Imbert C, Kirketerp-Moller K, Lebeaux D, Oliver A, Ullmann AJ, Williams C, Zimmerli W, The ESCMID Study Group for Biofilms (ESGB) and Consulting External Expert ESCMID guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of biofilm infections 2014. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:S1–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bjarnsholt T, Alhede M, Eickhardt-Sorensen SR, Moser C, Kühl M, Jensen PO, Hoiby N. The in vivo biofilm. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21:466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kragh KN, Hutchison JB, Melaugh G, Rodesney C, Roberts AE, Irie Y, Jensen PO, Diggle SP, Allen RJ, Gordon V, Bjarnsholt T. Role of multicellular aggregates in biofilm formation. mBio. 2016;7:e00237. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00237-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tremblay YDN, Labrie J, Chénier S, Jacques M. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae grows as aggregates in the lung of pigs: is it time to refine our in vitro biofilm assays? Microb Biotechnol. 2017;10:756–760. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacKenzie KD, Wang Y, Shivak DJ, Wong CS, Hoffman LJL, Lam S, Kröger C, Cameron ADS, Townsend HGG, Köster W, White AP. Bistable expression of CsgD in Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium connects virulence to persistence. Infect Immun. 2015;83:2312–2326. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00137-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flemming HC, Wingender J. The biofilm matrix. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:623–633. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.An AY, Choi KG, Baghela AS, Hancock REW. An overview of biological and computational methods for designing mechanism-informed anti-biofilm agents. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:640787. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.64087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen HTT, Nguyen TH, Otto M. The staphylococcal exopolysaccharide PIA—biosynthesis and role in biofilm formation, colonization, and infection. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;18:3324–3334. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bello-Orti B, Deslandes V, Tremblay YDN, Labrie J, Howell KJ, Tucker AW, Maskell DJ, Aragon V, Jacques M. Biofilm formation by virulent and non-virulent strains of Haemophilus parasuis. Vet Res. 2014;45:104. doi: 10.1186/s13567-014-0104-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . One Health basics. Atlanta: CDC; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), World Health Organization (WHO) Taking a multisectoral One Health approach: a tripartite guide to addressing zoonotic diseases in countries. Geneva: WHO; 2019. p. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Destoumieux-Garzon D, Mavingui P, Boetsch G, Boissier J, Darriet F, Duboz P, Fritsch C, Giraudoux P, Le Roux F, Morand S, Paillard C, Pontier D, Sueur C, Voituron Y. The One Health concept : 10 years old and a long road ahead. Front Vet Sci. 2018;5:14. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cantas L, Suer K. Review: the important bacterial zoonoses in “One Health” concept. Front Public Health. 2014;2:144. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]