Abstract

We used in situ hybridization with fluorescently labeled rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes concurrently with measurements of bacterial carbon production, biomass, and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) to describe the bacterial community in sediments along a glacial stream. The abundance of sediment-associated Archaea, as detected with the ARCH915 probe, decreased downstream of the glacier snout, and a major storm increased their relative abundance by a factor of 5.5 to 7.9. Bacteria of the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium group were also sixfold to eightfold more abundant in the storm aftermath. Furthermore, elevated numbers of Archaea and members of the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium group characterized the phylogenetic composition of the supraglacial ice community. We postulate that glacial meltwaters constitute a possible source of allochthonous bacteria to the stream biofilms. Although stream water temperature increased dramatically from the glacier snout along the stream (3.5 km), sediment chlorophyll a was the best predictor for bacterial carbon production and specific growth rates along the stream. Concomitant with an increase in sediment chlorophyll a, the EPS carbohydrate-to-bacterial-cell ratio declined 11- to 15-fold along the stream prior to the storm, which is indicative of a larger biofilm matrix in upstream reaches. We assume that a larger biofilm matrix is required to assure prolonged transient storage and enzymatic processing of allochthonous macromolecules, which are likely the major substrate for microbial heterotrophs. Bacteria of the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium cluster, which are well known to degrade complex macromolecules, were most abundant in these stream reaches. Downstream, higher algal biomass continuously supplies heterotrophs with easily available exudates, therefore making a larger matrix unnecessary. As a result, bacterial carbon production and specific growth rates were higher in downstream reaches.

Although early biofilm research (e.g., references 15, 16, and 35) has largely focused on alpine streams, our current knowledge on the functioning and phylogeny of stream microbial communities still remains poor (27). This is particularly true for streams at high altitudes and latitudes, which is even more surprising considering the ecological significance of cold ecosystems dominated by ice and snow (see references 13, 46, and 47). Interest in low-temperature aquatic ecosystems was triggered by the recognition that they are major players in global change (3) and that cold-adapted microorganisms bear the potential for biotechnological applications (48).

Geesey et al. (15, 16) showed that bacteria associated with streambed biofilms dominate both numerically and metabolically in mountain streams and further emphasized the tight functional links between epilithic algae, exopolymer saccharides, and microbial heterotrophs in sediment biofilms. Haack and McFeters (20) also showed that bacteria use extracellular substances released by senescent algae in epilithic biofilms in a high alpine stream. Recently, these relationships between heterotrophs and phototrophs were confirmed in a cold and oligotrophic mountain stream where water temperature seems to have only minor effects on streambed bacterial activity (4). Thus, we still do not know if heterotrophic biofilm communities in cold streams obey the same rules as planktonic communities that have higher substrate requirements for the sustenance of metabolic activities at low temperatures (cf. references 39 and 58).

Furthermore, little is known about the effects of environmental gradients on the composition and functioning of sediment microbes along streams. Using gradient plates, McArthur et al. (33) found that bacteria isolated from sediments in grassland reaches were able to grow exclusively on grass leachates, whereas bacterial isolates from forested reaches further downstream were able to grow on leachates from both grass and the dominant types of foliage. This led McArthur et al. (33) to conclude that qualitative and quantitative differences of the substrates along the stream should select for variation in the sediment bacterial assemblages. Leff (26) also found spatial patterns in the bacterial assemblage of the water column along the Ogeechee River in Georgia and related this variation to changing substrate availability and protozoan grazing. By contrast, McArthur et al. (34) and Wise et al. (59) did not find any significant genetic variation in sediment-associated Burkholderia cepacia and Burkholderia pickettii as a response to environmental gradients. They postulated that the continuous downstream transport of water prevents bacteria from adapting to any selective pressure.

Glacial-stream chemistry and hydrology are obviously influenced by glacier dynamics which, along with channel slope and varying aquatic/terrestrial connectivity, generate strong downstream environmental gradients. We have therefore chosen a glacial stream and combined phylogenetic and ecological parameters to test the general hypothesis that sediment microbial communities change along environmental gradients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling site and sample collection.

The Rotmoos (RT) stream (11°05′N 46°50′E, 2,250 to 2,450 m above sea level [Table 1]) drains a pristine catchment (ca. 10 km2) in the Austrian Alps with approximately 40% of its surface area being glaciated (49). The catchment geology is characterized by gneisses and micaschists and a prominent marble stripe in the headwater subcatchment. Surficial sediment (at a depth of 0 to 4 cm) was collected on 12 August, 6 September, and 3 October 1999, at five sites along the stream (Table 1); all samples were collected around noon to account for diurnal variations in water flow, chemistry, and temperature. Daily average water flow was relatively high and fluctuating prior to the August sampling date, whereas the September sampling date was preceded by relatively low and invariate water flow. A late September storm (ca. 80 mm of precipitation in 24 h) that dramatically altered the stream channel occurred before the last sampling date. As revealed by light microscopy, the major algae associated with sediment were Hydrurus foetidus and species belonging to the genera Fragilaria, Synedra, Cymbella, Diatoma, Navicula, and Nitzschia.

TABLE 1.

Location of sampling sites along the RT stream and bulk sediment characteristics

| Site | Distance from glacier (km) | Gradient (m m−1) | Altitude (m.a.s.l.)b | Sedimenta

|

Organic matterc (% [wt/wt]) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median grain size (μm) | Bulk density (g ml−1 of sediment) | |||||

| RT0 | 0.1 | 0.11 | 2,440 | 528 ± 72 | 1.568 ± 0.079 | 0.046 ± 0.033 |

| RT1 | 0.3 | 0.26 | 2,360 | 514 ± 84 | 1.665 ± 0.074 | 0.021 ± 0.031 |

| RT2 | 1.0 | 0.06 | 2,300 | 450 ± 38 | 1.594 ± 0.057 | 0.026 ± 0.003 |

| RT3 | 2.1 | 0.05 | 2,270 | 519 ± 56 | 1.648 ± 0.122 | 0.040 ± 0.008 |

| RT4 | 3.0 | 0.02 | 2,250 | 355 ± 30 | 1.505 ± 0.027 | 0.058 ± 0.019 |

Mean ± SD of three sampling dates.

m.a.s.l., meters above sea level.

Determined as ash-free dry mass (450°C, 4 h).

Bacterial abundance is inversely related to sediment grain size (e.g., reference 8) because smaller particles have a higher surface area per unit mass. Therefore, at each site we collected random grab-samples that were gently wet-sieved through a 1,000-μm sieve. A fraction of >200 μm was retained to achieve sandy samples with a median grain size ranging from 355 to 528 μm (Table 1). The sandy sediment accounts for ca. 25% (wt/wt) (57) of the bulk benthic sediment in the RT stream, without considering cobble and boulders. It thus accounts for a large fraction of the surface available to microbial colonization. The bulk density of the sediment ranged from 1.505 to 1.665 g ml−1, and we related all microbial parameters to the sediment volume to prevent spurious correlations with the organic matter content (cf. reference 6). Samples for secondary production of bacteria were incubated in the field with radiochemicals to ensure an in situ temperature. Aliquot samples were immediately transferred into sterile polypropylene tubes (Corning, Cambridge, Mass.) containing 2.5% (vol/vol) formaldehyde and a 1:1 mixture of ethanol and paraformaldehyde (4%, vol/vol) for the determination of bacterial biomass and whole-cell in situ hybridization, respectively. The remaining sediment was frozen (−20°C) for carbohydrate, amino acid, and chlorophyll a analyses, which were performed within 2 months.

Glacial ice samples.

We collected supraglacial ice in October 1999, using an ethanol-flame-sterilized ice ax. To avoid the inclusion of atmospheric deposition on the ice cover, we scraped the surface ice and carefully chipped the underlying ice (ca. 2 liters) into HCl-washed and 0.22-μm-filtered MilliQ-rinsed PE trays. Ice samples were transferred frozen to the laboratory and stored at −20°C. For analyses, they were carefully thawed and [3H]leucine incorporation was performed at 0°C in a defrosting bath.

Stream water chemistry.

Stream water conductance was measured in the field with a WTW LF196 probe. Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) was measured with a Shimadzu TOC-5000, and ions were measured with a DIONEX DX-120. Ammonium and total phosphorus (Ptot) were measured photometrically by applying the indophenol-blue and molybden-blue method after digestion by the method of Vogler (56).

Sediment organic matter.

Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) were harvested from lyophilized sediment (ca. 10 g dry mass) by extraction with 50 mM EDTA on a rotary shaker (1 h). The extract was 0.2-μm-filtered to remove particles and bacterial cells, and EPS was precipitated in the filtrate with ice-cold 99% (vol/vol) ethanol and left at −20°C for 48 h. The polymeric fraction was pelleted by centrifugation (900 × g for 30 min), and the white pellet was redissolved in MilliQ water. EPS was analyzed for bulk carbohydrates according to the sulfuric acid-phenol method (12). Total amino acids associated with EPS were assayed spectrofluorometrically (EX342/EM452) in aliquot samples after derivatization with o-phthaldialdehyde as described by Lindroth and Mopper (28). The amino acid solution AA-S-18 (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was used as a standard. Sediment chlorophyll a was extracted with p.a. grade methanol (99% [vol/vol]) from approximately 2 to 3 g of sediment during 12 h in the dark (4°C). After centrifugation, the supernatant was assayed fluorometrically (EX435/EM675), and chlorophyll a from spinach (Sigma) was used as a standard.

Bacterial abundance and biomass.

Bacterial abundance was estimated by epifluorescence microscopy (Nikon Labophot-2 with an Epi-Flu attachment, interference filter 450 to 490 nm) after staining with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma) according to the method of Porter and Feig (43). Approximately 2 to 3 g (wet mass) of sediment preserved in formaldehyde (2.5%) was incubated in 0.1 M tetrasodium pyrophosphate for 1 h and subsequently sonicated (180 s, 40-W output) to detach the bacterial cells from the sediment (54). In order to reduce the high background fluorescence caused by minerals, 2 ml of the thoroughly mixed supernatant was transferred into Eppendorf tubes, sonicated (microtip, 30 s, 30-W output) and finally spun with a tabletop centrifuge (Eppendorf 5415C) to pellet mineral particles. This procedure significantly reduced background fluorescence and, as revealed by microscopic analyses of the residual particles, recovered on average more than 93% of the bacterial cells. One milliliter of the supernatant was stained with 50 μl of DAPI (100 μg ml−1) and filtered (<20 kPa vacuum) onto a black 0.2-μm GTBP Millipore filter (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.). Bacterial cells were enumerated in 10 to 30 randomly selected fields to account for 300 to 500 cells. Two filters were counted per site and date.

Cell size and shape were determined on 400 to 600 bacterial cells per filter with image analysis as described by Posch et al. (44) with a Zeiss Axioplan epifluorescence microscope connected to a high-sensitivity charge-coupled device camera (Optronics ZVS-47EC) and using the software LUCIA (Laboratory Imaging, Prague, Czech Republic). Cell volume was derived from V = (w2 × π/4) × (l − w) + (π × w3/6), where V is the cell volume (in cubic micrometers), and w and l are cell width and length (in micrometers), respectively. We used the allometric relationship between cell volume and cell carbon content (in femtograms) given by Norland (41), C = 120 × V0.72, to calculate bacterial biomasses. Biomass allocation in designated cell length classes of a 0.1-μm interval was calculated as the product of abundance and mean cell C content in the respective length classes.

Bacterial secondary production.

The incorporation of [3H]leucine was used to estimate bacterial secondary production in the sediment and was measured according to the method of Marxsen (32). Approximately 2 to 3 g (wet weight) of sediment was incubated with [3H]leucine (specific activity, 60 Ci mmol−1; American Radiochemicals) at saturating concentrations of 200 nM (made up with cold leucine) for 2 to 4 h in the field at in situ temperatures in the dark. Time series confirmed linear [3H]leucine uptake within this incubation time. Triplicate [3H]leucine assays and duplicate formaldehyde-killed (2.5% final concentration, 30 min prior to [3H]leucine addition) controls were run for each site. The [3H]leucine incorporation was stopped in the field with 5 ml of formaldehyde, and samples were frozen (−20°C) within 2 to 3 h. Upon return to the laboratory, samples were repeatedly washed with 5% formaldehyde following a 24-h alkaline extraction of macromolecules with 0.3 N NaOH–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–25 mM EDTA. The extract was subsequently centrifuged (2,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min), the supernatant was transferred into Sorvall tubes on ice and 0.7 ml of 3 N HCl was added for acidification along with 0.5 ml (4 mg ml−1) of γ-globulin as a coprecipitate and 1.2 ml of 30% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) for precipitating the macromolecules. After 45 min, the solution was centrifuged (6,500 × g for 20 min at 4°C), the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was washed with 5% ice-cold TCA and centrifuged again (6,500 × g for 20 min at 4°C). The resulting pellet was considered to include DNA and proteins. DNA was solubilized by redissolving the pellet in 3 ml of 5% TCA and was transferred to a hot (90 to 95°C) water bath for 35 min. Subsequently, the solution was centrifuged again, and the pellet was resuspended in 3 ml of 0.5 N NaOH in a water bath at 95°C for 1 h. Two milliliters of the supernatant containing the protein fraction was collected in a 6-ml liquid scintillation cocktail (Ultima Gold; Canberra Packard) and radioassayed with a liquid scintillation counter (Canberra Packard Tricarb 2000). Bacterial carbon production was calculated as described by Simon and Azam (51). Specific growth rates were calculated as the ratio of bacterial production to biomass.

Whole-cell in situ hybridization.

Within 3 days after sampling, bacterial cells were detached from the sediment by sonication and centrifugation as described above, and 3- to 5-ml-aliquot samples of the supernatant were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2, for 30 min at room temperature and subsequently filtered onto 0.2-μm polycarbonate membrane filters (Millipore GTTP, 47-mm diameter). Air-dried filters were stored in petri dishes at −20°C pending further processing.

The following oligonucleotide probes (Interactiva, Ulm, Germany) were used to describe the microbial communities: ARCH915 for members of the domain Archaea (16S rRNA, positions 915 to 934), EUB338 for members of the domain Bacteria (16S rRNA, positions 338 to 355), BET42a for the beta subclass of Proteobacteria (23S rRNA, positions 1027 to 1043), ALF968 for the alpha subclass of Proteobacteria (16S rRNA, positions 968 to 986), and CF319a for the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium cluster (16S rRNA, positions 319 to 336) (2). Probes were labeled with the indocarbocyanine fluorescent dye CY3 (Biological Detection Systems, Pittsburgh, Pa.). To ensure optimal stringency conditions, the unlabeled probe GAM42a served as competitor for BET42a (e.g., references 30 and 31). Since there is some potential for cross-hybridization with probes ARCH915 and CF319a (22), we compared the morphologies of cells hybridizing with ARCH915 and CF319a (see discussion below).

We used the protocols by Alfreider et al. (1) and Glöckner et al. (19) for the hybridization procedure, DAPI staining, and microscopy. Aliquot filter sections were placed on coverslips, covered with 18 μl of hybridization buffer along with 2 μl (50 ng ml−1) of the respective fluorescent probe, and hybridized at 46°C for at least 90 min. The hybridization buffer consisted of 0.9 M NaOH, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.01% SDS, and 35% formamide. Subsequently, filters were washed for 15 min at 48°C with a solution consisting of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mM EDTA, 0.01% SDS, and an adequate concentration of NaOH. Next, they were rinsed in distilled water, air dried, counterstained with 1 μg of DAPI per ml, and washed in ethanol (70% [vol/vol]) and distilled water. Filter sections were mounted in glycerol medium (5:1 mixture of mounting medium from Citifluor, Canterbury, England, and VectaShield mounting medium from Vector Laboratories) and inspected by epifluorescence microscopy (Axioplan; Carl Zeiss, Inc.) using the filter sets BP365, FT395, and LP397 for DAPI and BP535-550, FT505, and LP610-675 for CY3. At least 1,000 to 1,500 cells stained with DAPI were counted per hybridized filter to account for the percentage of CY3-stained cells. As CY3 sorbed to minerogenic particles in some samples, thereby increasing the background fluorescence, each particle emitting a CY3 signal was checked against DAPI staining. We checked each filter section for autofluorescence signals of phototrophic and cyanobacterial cells, using the filter sets BP510-560 (FT580, LP590) and BP450-490 (FT510, LP520). The amounts of autofluorescent particles remained low in sediment samples (<0.5% of DAPI signals) but were elevated in glacier and stream water samples (2.7% and 1.4%, respectively, with a standard deviation [SD] of 0.4). However, stronger fluorescent signals and the clear-cut morphology of cyanobacteria and algae allowed reliable discrimination.

RESULTS

Environmental gradients.

Stream water temperatures exhibited very steep gradients along the stream during all three sampling dates (Table 2). The headwater catchment geology imparted a higher magnesium and calcium signature to the stream water at sampling site RT0 on 12 August and 6 September (Table 2). Both N-NO3 and N-NH4 concentrations clearly decreased downstream while Ptot showed no clear longitudinal gradient. DOC concentrations were generally elevated at RT0 in August and September but did not exhibit any clear pattern. A late-September storm altered flow paths through the catchment and dramatically affected stream water chemistry on 3 October. Average solute concentrations and conductance were about twofold higher after the storm, and no gradients, with the exception of nitrate and ammonium, could be detected (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Physicochemical characteristics of the RT stream water

| Site and date | Temperature conductance

|

Cl− (mg liter−1) | Na+ (mg liter−1) | Mg2+ (mg liter−1) | Ca2+ (mg liter−1) | NO3 (μg liter−1) | NH4 (μg liter−1) | Ptot (μg liter−1) | DOC (mg liter−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| °C | μS cm−1 | |||||||||

| 12 August 1999 | ||||||||||

| RT0 | 0.9 | 75.0 | NDa | 0.16 | 1.82 | 11.13 | 161 | 22 | 61.9 | 0.363 |

| RT1 | 1.8 | 52.6 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 1.11 | 7.80 | 159 | 31 | 58.1 | 0.281 |

| RT2 | 2.7 | 59.6 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 1.27 | 8.83 | 148 | 34 | 92.5 | 0.549 |

| RT3 | 4.5 | 61.4 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 1.28 | 8.83 | 145 | 22 | 64.0 | 0.291 |

| RT4 | 5.9 | 69.0 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 1.43 | 9.77 | 144 | 18 | 51.9 | 0.270 |

| 6 September 1999 | ||||||||||

| RT0 | 1.1 | 77.5 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 1.89 | 13.30 | 120 | 15 | 70.4 | 0.572 |

| RT1 | 2.1 | 57.4 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 1.03 | 8.58 | 110 | 14 | 126 | 0.259 |

| RT2 | 3.8 | 60.0 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 1.11 | 8.82 | 100 | 11 | 54.8 | 0.237 |

| RT3 | 5.8 | 60.6 | 0.10 | 0.28 | 1.10 | 8.61 | 90 | 10 | 71.0 | 0.261 |

| RT4 | 7.1 | 67.3 | 0.10 | ND | 1.20 | 9.44 | 90 | 5 | 77.8 | 0.246 |

| 3 October 1999 | ||||||||||

| RT0 | 0.4 | 111.3 | 0.18 | 0.37 | 2.18 | 15.44 | 275 | 41 | ND | 0.380 |

| RT1 | 1.5 | 111.1 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 2.25 | 16.57 | 248 | 35 | ND | 0.379 |

| RT2 | 2.8 | 132.8 | 0.20 | 0.47 | 2.77 | 18.67 | 206 | 24 | ND | 0.320 |

| RT3 | 3.4 | 130.8 | 0.21 | 0.50 | 2.65 | 18.84 | 202 | 21 | ND | 0.438 |

| RT4 | 4.4 | 139.3 | 0.20 | 0.53 | 2.57 | 19.03 | 186 | 14 | ND | 0.361 |

ND, not determined.

Sediment chlorophyll a and EPS.

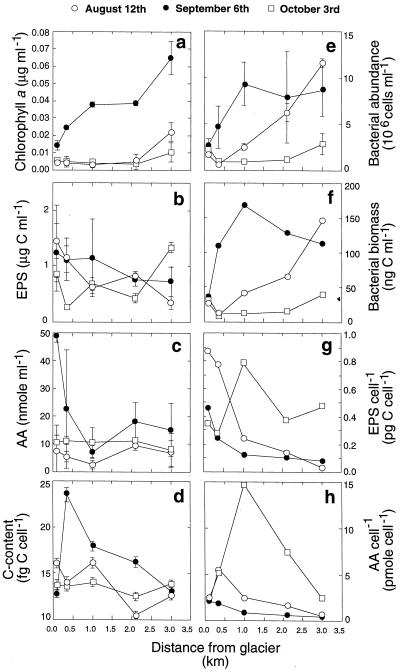

Sediment chlorophyll a exhibited a pronounced longitudinal gradient in September, whereas the spatial patterns were not as clear in August and October (Fig. 1a). After a prolonged period of low variations in flow (data not shown), the average chlorophyll a concentration was approximately fourfold and sevenfold higher on 6 September than on the August and October sampling dates, respectively. An inverse power model described the significant relationships between sediment chlorophyll a and both stream water N-NH4 (Chl a = 1.556 × N-NH4−0.427, r2 = 0.89, P = 0.003) and N-NO3 (Chl a = 38.28 × N-NO3−0.027, r2 = 0.61, P = 0.008) concentrations along the stream continuum. Stream water temperature explained 48% (P = 0.004) of the variation of the chlorophyll a concentration.

FIG. 1.

Longitudinal patterns of sediment organic matter and bacterial biomass along the RT stream. Panels: a, chlorophyll a; b, EPS as carbohydrates; c, amino acids (AA) associated with EPS; d, cell carbon content; e, bacterial abundance; f, bacterial biomass; g, carbohydrate EPS normalized to bacterial cell number; h, EPS amino acids normalized to bacterial cell number.

EPS carbohydrates declined from site RT0 to site RT4 prior to the storm, but there was no clear longitudinal gradient in the storm aftermath (Fig. 1b). Similarly, amino acids associated with microbial EPS were highest on 6 September (Fig. 1c). Before the storm, amino acid concentrations were elevated at site RT0 and declined downstream to slightly increase again at site RT3.

Cell size and biomass.

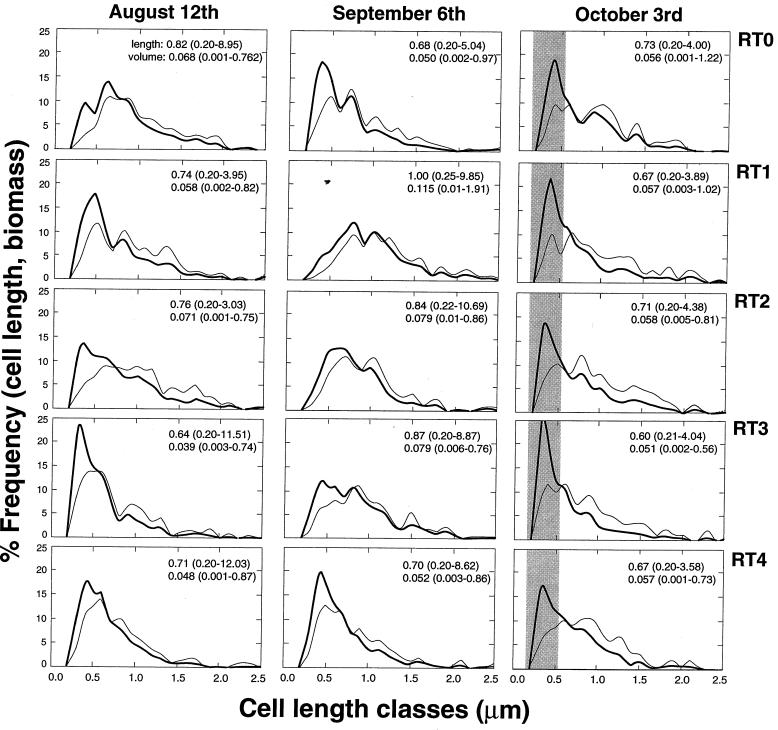

Frequency analyses of cell length and biomass allocation revealed that community size structure did not change consistently along the stream (Fig. 2). In many cases, cell length frequency diagrams showed pronounced peaks (13 to 23%) for the 0.2- to 0.4-μm size classes, which correspond to average cell length/width ratios ranging from 1.04 ± 0.12 to 1.14 ± 0.25, indicative of coccoid and short rod-shaped cells. This pattern was remarkably consistent in the samples taken during the storm aftermath, with 17 to 26% of the cells belonging to the 0.3- to 0.4-μm size class. On 6 September, the cell length distributions clearly shifted toward longer cells. Nonetheless, biomass allocation always showed that bacteria larger than 0.6-μm cell length (i.e., with rod-shaped cells) predominated; they averaged 70% ± 9%, 75% ± 12%, and 72% ± 6% for the August, September, and October sampling dates, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Bacterial cell size distribution (thick curve) and biomass allocation (thin curve) to cell length intervals of 0.1 μm along the RT stream. The shaded bar designates the consistent cell length peak along the stream in October.

The average cell carbon content did not show a clear spatial pattern (Fig. 1d). On 6 September, the carbon content per cell was, on average, 25% higher than on the other sampling dates. At site RT0, bacterial abundance varied little, but it increased continuously, by factors of 3 and 7, downstream on 12 August and 6 September, respectively (Fig. 1e). As a result, total bacterial biomass was clearly higher along the stream on 6 September, while values at RT0 showed little variation (Fig. 1f). Bacterial biomass increased downstream by factors of 5.5 and 3.3 prior to the storm and by a factor of 1.2 in its aftermath.

EPS carbohydrates normalized to the bacterial abundance decreased by factors of 11 to 15 along the stream prior to the storm (Fig. 1g). No such pattern was observed on 3 October. The EPS carbohydrates per cell closely followed the downstream temperature gradient, and their relationship was best described by an inverse power model (EPS cell−1 = 0.777 × T−0.135, r2 = 0.74, P = 0.01). EPS amino acids normalized to the cell number showed a similar pattern (Fig. 1f), and average values were 2.6- to 6-fold higher in October than prior to the storm.

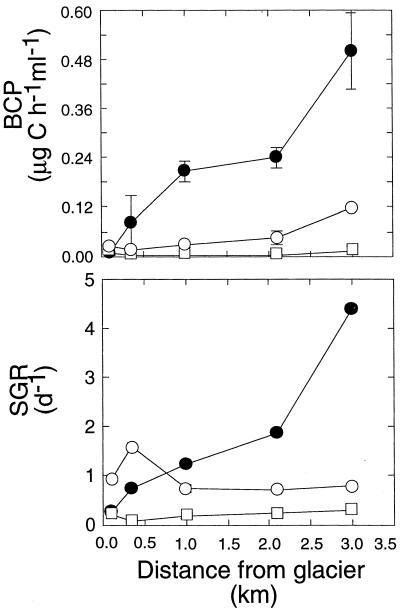

Bacterial secondary production and specific growth rate.

Concomitantly with bacterial biomass, the bacterial carbon production (BCP) varied only little at site RT0 (Fig. 3). Average BCP increased downstream by factors of 4.6, 55, and 1.7, on the respective sampling dates. Average BCP was 4.8- and 50-fold higher at site RT4 on 6 September than on 12 August and 3 October, respectively. The specific growth rate (SGR) increased downstream by factors of 15 and 1.4 on 6 September and 3 October, respectively, whereas it slightly decreased on 12 August.

FIG. 3.

Longitudinal gradients of BCP and SGR in sediment biofilms along the RT stream.

As shown by the standardized regression coefficients in Table 3, stream water temperature, sediment chlorophyll a, and bacterial biomass significantly affected BCP. Similar relationships were found for SGR. Stepwise multiple regression applied to the data pooled from all three sampling dates retained chlorophyll a (standardized coefficient, 0.332) and bacterial biomass (standardized coefficient, 0.629) as predictors to explain 79% (F ratio = 24.85, P < 0.001) of the variation in log-transformed BCP. As for the log-transformed SGR, only chlorophyll a entered the model, operating with the same parameters as in Table 3. Since bacterial biomass is included in the SGR term, it was not considered for the regression analysis on SGR to prevent spurious correlations.

TABLE 3.

Linear regression analyses on log-transformed BCP and SGR

| Measurement | Independent variable | Standardized coefficient | r2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| log BCP | Temperature | 0.653 | 0.383 | 0.008 |

| Chlorophyll a | 0.802 | 0.613 | <0.001 | |

| Bacterial biomass | 0.861 | 0.722 | <0.001 | |

| EPS | 0.202 | 0.000 | 0.471 | |

| Amino acids | −0.285 | 0.011 | 0.302 | |

| DOC | −0.532 | 0.228 | 0.041 | |

| log SGR | Temperature | 0.564 | 0.266 | 0.028 |

| Chlorophyll a | 0.721 | 0.481 | 0.002 | |

| EPS | 0.267 | 0.000 | 0.336 | |

| Amino acids | −0.351 | 0.056 | 0.199 | |

| DOC | −0.503 | 0.195 | 0.056 |

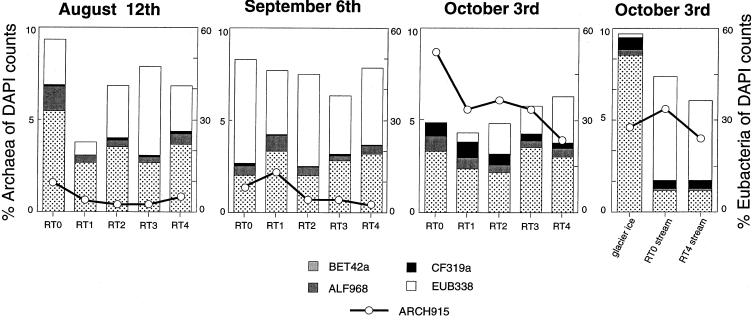

Whole-cell in situ hybridization.

The EUB338 probe detected 22% (0.14 × 106 cells ml−1 of sediment) to 56% (0.93 × 106 cells ml−1 of sediment) of DAPI-stained cells along the RT stream, with 3 to 34% that could not be explained by the sum of the BET42a, ALF968, and CF319a subclasses (Fig. 4). No consistent longitudinal patterns of Eubacteria were found along the stream. However, the number of cells hybridizing with the EUB338 probe was noticeably (1.2- to 2-fold) lower on 3 October than before the storm; this was particularly clear at site RT0. The BET42a probe (18% ± 3% of DAPI-stained cells, corresponding to 0.77 × 106 ± 0.68 × 106 cells ml−1 of sediment) detected on average fivefold to sixfold more cells than the ALF968 probe along the stream. Only 0.58% ± 0.37% and 0.44% ± 0.17% of DAPI-stained cells hybridized with the CF319a probe on 12 August and 6 September, respectively. This percentage was augmented sixfold to eightfold in the storm aftermath, and it also exhibited a prominent downstream gradient. Overall, the ARCH915 probe detected 0.4 to 7.5% (corresponding to 0.02 × 106 to 0.19 × 106 cells ml−1 of sediment) of DAPI-stained cells with about fourfold higher detection rates at upstream sites RT0 and RT1 than at site RT4. In October, the percentage of cells hybridizing with the ARCH915 probe averaged 6.0% ± 1.7% along the stream and was thus 7.9-fold higher than in August and 5.5-fold higher than in September.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic composition of Bacteria and Archaea in sediment biofilms, glacier ice, and stream water as revealed by fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Glacier ice community.

The glacier ice was very low in sediment, and the bacterial abundance averaged 2.1 × 104 (±8.2%; n = 3) cells ml−1, of which the majority was associated with organic particles. Cells were relatively large rods with an average volume of 0.140 μm3, which translates to a cell C content of 26.9 ± 18.9 fg cell−1. Besides these particle-associated cells, we repeatedly observed nonattached “ghost” cells that were remarkable in size (1.039 ± 0.479 μm3) but gave no distinct DAPI signal. Secondary production of bacteria was very low, with 0.9 ng of C d−1 liter−1. The glacier ice microbial community was characterized by a high percentage of BET42a (48.5% of DAPI-stained cells), 3.7% CF319a, and 4.3% ARCH915 (Fig. 4).

DISCUSSION

Phylogenetic composition and dynamics.

This study is the first to document the occurrence of Archaea in a lotic ecosystem (cf. reference 30) and—more importantly—in glacier ice, where they occurred in abundance similar to that found in the stream itself. The microscopic observation that at least some of these putative archaeal cells were dividing both in the stream and the glacier ice (data not shown) suggests that a part of the archaeal population is active in this cold ecosystem. The fact that cells emitted a detectable CY3 signal points to a relatively high rRNA content and, consequently, to a certain growth activity of Archaea. Originally, Archaea were believed to be confined to specialized habitats, characterized by high temperature and salinity and extreme pH, and to strictly anaerobic niches permitting methanogenesis (e.g., reference 45). Recently, however, studies based on the comparison of 16S rRNA genes have revealed the occurrence of Archaea in habitats that range from freshwater (29) and marine (55) sediments to the cold marine surface waters of Antarctica (11).

Although the ARCH915 probe has been widely used to detect archaeal cells (e.g., references 31 and 42), there is preliminary evidence (22) that the ARCH915 probe likely exhibits three mismatches to the target sequence and therefore also to members of the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium cluster that are thought to occasionally hybridize with the archaeal probe. In the present study, we used cell morphologies that matched presumed archaeal cells and cells from the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium cluster to test for possible interference with the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium cluster. We consider the fact that similarly shaped cells hybridized with both the ARCH915 and EUB338 probes on only a few occasions as evidence that the relative abundances of archaeal cells could be only marginally overestimated.

The majority of members of the domain Bacteria found in sediments from the RT stream fell into the beta subclass of the Proteobacteria, a finding which is consistent with other reports from oligotrophic freshwater systems that range from drinking water biofilms (24, 31) to alpine lakes (1, 42). As suggested by the increasing data on cloning of 16S rRNA gene fragments (e.g., reference 36) and fluorescence in situ hybridization application to a wide array of ecosystems (18), the beta subclass of Proteobacteria predominates in freshwater planktonic communities. Our data now corroborate recent findings that these Proteobacteria also account, at least occasionally, for a large number of the Eubacteria in lotic biofilms (10, 30). It is striking that, in the glacier ice, the beta subclass of Proteobacteria clearly predominated, with 88% of the cells hybridizing with the eubacterial probe. Sediment Proteobacteria of the alpha subclass were consistently lower in abundance than the members of the beta subclass, which agrees well with reports from other ecosystems (cf. reference 18).

Members of the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium group were regularly detected in sediments along the RT stream although in very low numbers (1.1% ± 0.7% of eubacterial cells before the storm). However, they were detected in consistently higher numbers at upstream sites. In the storm aftermath, their numbers were noticably higher, with 11.4% ± 5.4% of the eubacterial cells counted in the sediments. Their relative abundances were also clearly elevated in the stream water and notably in glacier ice. This finding agrees with their apparent occurrence in cold and oligotrophic ecosystems such as in the winter cover (1) and the pelagic water (42) of a high mountain lake, where they account for a remarkable percentage of the microbial biomass. There is ample evidence that members of the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium cluster are adapted to low nutrient and substrate concentrations. For instance, Noble et al. (40) showed that members of the genus Flavobacterium isolated from oligotrophic habitats and subsequently grown under both low temperatures and low-nutrient concentrations were more versatile in terms of substrate uptake than when they were grown in rich media. Furthermore, Geller (17) found that Flavobacterium isolates from lake water decompose refractory substrates more efficiently than do other strains.

Gradients and functional biofilm heterogeneity.

Large parts of the RT catchment are devoid of vegetation, and terrestrial organic carbon inputs are low along the stream (T. J. Battin, unpublished data). We presume that in-stream primary producers represent the major carbon source for microbial heterotrophs, an assumption that was in fact supported by the very low content of organic matter (Table 1) in the sediment and by low DOC concentrations. Algal biomass (as indicated by chlorophyll a) consistently increased downstream, a pattern that most likely results from the interplay of physical disturbances such as mechanical abrasion (cf. reference 7) and shading by suspended solids. Both processes largely depend on the flow velocity, which is in fact higher in upstream reaches where elevated slopes (Table 1) cooccur with reduced channel stability. Further downstream, lower slopes along with a wider stream channel reduce flow-induced physical disturbance. The downstream increase of algal biomass was always accompanied by a significant decrease in stream water N-NH4 and N-NO3 concentrations, a pattern that has also been observed in small glacial streams in Antarctica (e.g., references 21 and 37). As the water flows over benthic biofilms, nitrogen is removed from the water and, in some cases, considerable internal cycling in cyanobacterial mats has been postulated to create the downstream gradients (21).

Although water temperature, a factor of general importance for bacterial growth, increased strongly downstream, chlorophyll a explained most of the variation in heterotrophic activity along the RT stream, which agrees with previous observations from other oligotrophic mountain streams (e.g., references 4 and 20). However, the synergistic effects of temperature and substrate supply (as indicated by chlorophyll a) on the heterotrophic community of the biofilm are not yet clear. Regression analyses revealed that water temperature explained only 38 and 27% of the variation in BCP and SGR, respectively. Temperature did not significantly improve the multiple models and was therefore excluded as a further predictor. Thus, BCP and notably SGR largely relied on substrate supply in the benthic sediments of the glacial RT stream. It is now well known that bacteria in cold aquatic ecosystems require high substrate concentrations to be active because of reduced substrate affinity at low temperatures (e.g. references 39 and 58). The underlying mechanism is stiffening of the cell membrane lipids, which subsequently leads to decreased efficiency of the transport proteins. Hence, low substrate affinity requires higher substrate concentrations at low temperatures to maintain cell metabolism (39).

The biofilm matrix that largely consists of EPS also functions as an important site of transient storage of carbon immobilized from the stream water (5) that ultimately buffers against fluctuating substrate supply (14). We found significantly decreasing gradients of EPS (as carbohydrates and amino acids) normalized to bacterial cell numbers along the stream. This pattern likely reflects the lower algal biomass in upstream sites where bacteria rely more on allochthonous carbon that enters the stream more sporadically and is generally of low bioavailability. Thus, a relatively large matrix is required to store transiently macromolecules that need enzymatic processing before being used as substrate by bacteria. It is striking that this pattern cooccurs with the downstream distribution of the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium cluster, members of which have high catabolic ability for complex and more recalcitrant molecules as discussed above. Furthermore, at least some gliding Cytophaga species were shown to produce copious amounts of EPS when grown on surfaces, whereas suspended cells failed to synthesize EPS (23). By constrast, in lower reaches, larger amounts of algae continuously supply the heterotrophic community with highly available exudates that make storage, enzymatic processing, and hence an elaborated biofilm matrix unnecessary.

Cell size is indicative of the trophic status of bacteria (e.g., reference 38), and we thus anticipated a downstream shift in the microbial community size structure distribution towards larger cell sizes as a result of starvation in the upstream reaches due to lower substrate supply and lower average temperature. However, no consistent spatial pattern of size structure could be detected, with the exception of an apparent shift from site RT0 to RT1 on 6 September. Yet there were clear differences among dates. Larger cells dominated the size structure in September when algal biomass and average EPS were elevated, both indicative of well-established biofilms, whereas in the storm aftermath, small coccoid and rod-shaped cells dominated the size structure of the community. Along with very low SGR and ribosomal content of bacteria in October, as indicated by lower fluorescence in situ hybridization detection rates (EUB338 probe [Fig. 4]), this strongly points to starved cells in an early phase of biofilm formation. It is, in fact, well known (e.g., reference 25) that starved, small-sized cells adhere to surfaces in oligotrophic systems because conditioned surfaces tend to concentrate scarce nutrients and substrates, thereby making sessile growth advantageous. Elevated per-cell EPS, as observed in the storm aftermath, also supports this scenario and agrees with laboratory findings (53) showing that cell attachment to surfaces stimulates exopolysaccharide production.

Glacier control on stream biofilms.

There is some evidence (50, 52) that glaciers harbor palaeomicrobial communities that are largely fueled by organic carbon that results from the soil organic matter accumulated under interglacial conditions in areas subsequently overridden by Pleistocene ice sheets. We were able to show that supraglacial ice from the RT glacier contains an autochthonous microbial assemblage largely associated with particles similar to those from a high Arctic glacier (52) and sea ice (9). Comparative studies on glacier microbes are still extremely scarce, but Sharp et al. (50) reported glacial bacterial abundances of 5.3 × 104 to 5.9 × 107 cells ml−1 in two Swiss glaciers, with 5 to 24% of cells dividing or recently divided. We were able to describe for the first time the bulk phylogeny of a glacier ice community with a mentionable percentage of Archaea and a remarkably high number of cells from the beta subclass of Proteobacteria and from the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium cluster. Bacteria from the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium cluster also seem to be common in sea ice, where gliding strains are attached to particles and algal cells (9).

The sediment microbial community changed over a relatively small spatial scale (ca. 3.5 km) along the stream, and we propose that at least part of this shift is attributable to glacier-melting dynamics. In fact, the late September storm not only reduced nutrient resources (as indicated by chlorophyll a) but also changed biofilm composition and functioning. Archaea and bacteria from the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium cluster were much more abundant in the storm aftermath. Furthermore, Archaea showed a downstream gradient on all sampling dates, whereas the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium cluster showed this trend only in the storm aftermath. This suggests that subglacial meltwaters continuously entrain microbes from glacial populations into the RT stream, where they adhere to sediment biofilms, an assumption that is certainly supported by the signature of the stream water microbial community. Massive storm-induced supraglacial flow is likely to reinforce this process, as indicated by the similar phylogenetic signatures of the glacial community and the upstream biofilms after the storm. The observed patterns in the stream can best be interpreted as resulting from the interplay of downstream transport of archaeal and bacterial cells and niche adaptation in the upstream reaches. Certainly, other allochthonous sources of bacteria such as adjacent soils cannot be discounted. However, the temporal dynamics of the Archaea and Cytophaga-Flavobacterium gradients point to the glacier as an important source. Ultimately, this implies that glaciers influence the stream microbiology not only chemically and physically, but also directly by seeding and inoculating, thus having a profound impact on the composition and functioning of microbial communities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Thomas Posch, Jakob Pernthaler, and two anonymous reviewers for commenting on an earlier version of the paper. We also thank Werner Müller, Joseph Franzoi for excellent chemical analyses, and Meini Strobl for his hospitality in Obergurgl. TIWAG kindly provided flow data. Thanks to the lab of Branko Velimirov for access to the sonicator.

Financial support came from the Austrian National Bank (7323) to Roland Albert and B.S. and from the Landesregierung Tirol to T.J.B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfreider A, Pernthaler J, Amann R, Sattler B, Glöckner F O, Wille A, Psenner R. Community analysis of the bacterial assemblages in the winter cover and pelagic layers of a high mountain lake by in situ hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2138–2144. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2138-2144.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrigo K R, Worthen D L, Lizotte M P, Dixon P, Dieckmann G. Primary production in Antarctic sea ice. Science. 1997;276:394–397. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5311.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battin T J. Hydrodynamics is a major determinant of streambed biofilms: from the sediment to the reach scale. Limnol Oceanogr. 2000;45:1308–1319. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Battin T J, Butturini A, Sabater F. Immobilization and metabolism of dissolved organic carbon by natural sediment biofilms in Mediterranean and temperate streams. Aquat Microb Ecol. 1999;19:297–305. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bird D F, Duarte C M. Bacteria-organic matter relationship in sediments: a case of spurious correlation. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1989;41:1015–1023. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blenkinsopp S A, Lock M A. The impact of storm-flow on river biofilm architecture. J Phycol. 1994;5:807–818. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bott T L, Kaplan L A. Bacterial biomass, metabolic state, and activity in stream sediments: relation to environmental variables and multiple assay comparisons. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;50:508–522. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.2.508-522.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowman J P, McCammon S A, Brown M V, Nichols D S, McMeekin T A. Diversity and association of psychrophilic bacteria in Antarctic sea ice. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3068–3078. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3068-3078.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brümmer I H M, Fehr W, Wagner-Döbler I. Biofilm community structure in polluted rivers: abundance of dominant phylogenetic groups over a complete annual cycle. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3078–3082. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.7.3078-3082.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeLong E F, Ying Wu K, Prezelin B B, Jovine R V M. High abundance of Archaea in Antarctic marine picoplankton. Nature (London) 1994;371:695–697. doi: 10.1038/371695a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubois M, Giles K A, Hamilton J K, Rebers P A, Smith F. Colorimetric method for the determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felip M, Sattler B, Psenner R, Catalan J. Highly active microbial communities in the ice and snow cover of high mountain lakes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2394–2401. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2394-2401.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman C, Lock M A. The biofilm polysaccharide matrix: a buffer against changing organic supply. Limnol Oceanogr. 1995;40:273–278. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geesey G G, Mutch R, Costerton J W, Green R B. Sessile bacteria: an important component of the microbial population in small mountain streams. Limnol Oceanogr. 1978;23:1214–1223. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geesey G G, Richardson W T, Yeomans H G, Irvin R T, Costerton J W. Microscopic examination of natural sessile bacterial populations from an alpine stream. Can J Microbiol. 1977;23:1733–1736. doi: 10.1139/m77-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geller A. Comparison of mechanisms enhancing biodegradability of refractory lake water constituents. Limnol Oceanogr. 1986;31:755–764. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glöckner F O, Fuchs B M, Amann R. Bacterioplankton composition of lakes and oceans: a first comparison based on fluorescence in situ hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3721–3726. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3721-3726.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glöckner F O, Amann R, Alfreider A, Pernthaler J, Psenner R, Trebius K, Schleifer K. An in situ hybridization protocol for detection and identification of planktonic bacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:403–406. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haack T K, McFeters G A. Microbial dynamics of an epilithic mat community in a high alpine stream. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:702–707. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.3.702-707.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawes I, Bazier P. Freshwater stream ecosystems of James Ross Island, Antarctica. Antarct Sci. 1991;3:265–271. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hentschke A. M.Sc. thesis. Berlin, Germany: Humboldt University of Berlin; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humphrey B A, Dickson M R, Marshall K C. Physicochemical and in situ observations on the adhesion of gliding bacteria to surfaces. Arch Microbiol. 1979;120:231–238. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalmbach S, Manz W, Szewzyk U. Dynamics of biofilm formation in drinking water: phylogenetic affiliation and metabolic potential of single cells assessed by formazan reduction and in situ hybridization. FEMS Microb Ecol. 1997;22:265–279. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kjelleberg S, Hermansson N. The effect of interfaces on small starved marine bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:497–503. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.5.1166-1172.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leff L. Longitudinal changes in microbial assemblages of the Ogeechee River. Freshw Biol. 2000;43:605–615. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leff L G. Stream bacterial ecology: a neglected field? ASM News. 1994;60:135–138. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindroth P, Mopper K. High performance liquid chromatographic determination of subpicomole amounts of amino acids by procolumn fluorescence derivatization with o-phtaldialdehyde. Anal Chem. 1979;51:1667–1674. [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacGregor B J, Moser D P, Wheeler Alm E, Nealson K H, Stahl D A. Crenarchaeota in Lake Michigan sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1178–1181. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1178-1181.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manz W, Wendt-Potthoff K, Neu T R, Szewzyk U, Lawrence J R. Phylogenetic composition, spatial structure, and dynamics of lotic bacterial biofilms investigated by fluorescent in situ hybridization and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Microb Ecol. 1999;37:225–237. doi: 10.1007/s002489900148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manz W, Szewzyk U, Ericsson P, Amann R, Schleifer K H, Stenström T A. In situ identification of bacteria in drinking water and adjoining biofilms by hybridization with 16S and 23S rRNA-directed fluorescent oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2293–2298. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2293-2298.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marxsen J. Measurement of bacterial production in stream-bed sediments via leucine incorporation. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1996;21:313–325. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McArthur J V, Marzolf G R, Urban J E. Response of bacteria isolated from a pristine prairie stream to concentration and source of soluble organic carbon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:238–241. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.1.238-241.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McArthur J V, Leff L G, Smith M H. Genetic diversity of bacteria along a stream continuum. J N Am Benthol Soc. 1992;11:269–277. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McFeters G A, Stuart S A, Olson S B. Growth of heterotrophic bacteria and algal extracellular products in oligotrophic waters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:383–391. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.2.383-391.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Methé B A, Hiorns W D, Zehr J P. Contrasts between marine and freshwater bacterial community composition — analyses of communities in Lake George and six other Adirondack lakes. Limnol Oceanogr. 1998;43:368–374. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moorhead D L, McKnight D M, Tate C M. Modeling nitrogen transformations in Dry Valley streams, Antarctica. In: Priscu J C, editor. Ecosystem dynamics in a polar desert. Washington, D.C.: American Geophysical Union; 1998. pp. 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moriarty D J W, Bell R T. Bacterial growth and starvation in aquatic environments. In: Kjelleberg S, editor. Starvation in bacteria. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 25–52. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nedwell D B. Effect of temperature on microbial growth: lowered affinity for substrates limits growth at low temperature. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1999;30:101–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1999.tb00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noble P A, Dabinett P E, Crow J. A numerical taxonomic study of pelagic and benthic surface-layer bacteria in seasonally-cold coastal waters. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1990;13:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norland S. The relationship between biomass and volume of bacteria. In: Kemp P F, Sherr B, Sherr E, Cole J J, editors. Handbook of methods of aquatic microbial ecology. Boca Raton, Fla: Lewis Publications; 1993. pp. 303–308. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pernthaler J, Glöckner F O, Unterholzner S, Alfreider A, Psenner R, Amman R. Seasonal community and population dynamics of pelagic bacteria and archaea in a high mountain lake. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4299–4306. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4299-4306.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Porter K G, Feig Y G. The use of DAPI for identifying and counting aquatic microflora. Limnol Oceanogr. 1980;25:943–948. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Posch T, Pernthaler J, Alfreider A, Psenner R. Cell-specific respiratory activity of aquatic bacteria studied with the tetrazolium reduction method, cyto-clear slides, and image analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:867–873. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.867-873.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preston C M, Ying Wu K, Molinski T F, DeLong E F. A psychrophylic Crenarchaeon inhabits a marine sponge: Cenarchaeum symbiosum gen. nov., spec. nov. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6241–6246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Priscu J C, Fritsen C H, Adams E E, Giovannoni S J, Pearl H W, McKay C P, Doran P T, Gordon D A, Lanoil B D, Pinckney J L. Perennial antarctic lake ice: an oasis for life in a polar desert. Science. 1998;280:2095–2098. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Psenner R, Sattler B. Life at the freezing point. Science. 1998;280:2073–2074. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russel N J. Molecular adaptations in psychrophilic bacteria: potential for biotechnological applications. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 1998;61:1–22. doi: 10.1007/BFb0102287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schütz C. Ph.D. thesis. Innsbruck, Austria: University of Innsbruck; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharp M, Parkes J, Cragg B, Fairchild I J, Lamb H, Tranter M. Widespread bacterial populations at glacier beds and their relationship to rock weathering and carbon cycling. Geology. 1999;27:107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simon M, Azam F. Protein content and protein synthesis rates of planktonic marine bacteria. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1989;51:201–213. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skidmore M L, Foght J M, Sharp M J. Microbial life beneath a high Arctic glacier. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3214–3220. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.8.3214-3220.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vandevivere P, Kirchman D L. Attachment stimulates exopolysaccharide synthesis by a bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3280–3286. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.10.3280-3286.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Velji M I, Albright L J. Microscopic enumeration of attached marine bacteria of seawater, marine sediment, fecal matter, and kelp blade samples following pyrophosphate and ultrasound treatments. Can J Microbiol. 1985;32:121–126. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vetriani C, Jannasch H W, McGregor B J, Stahl D A, Reysenbach A L. Population structure and phylogenetic characterization of marine benthic Archaea in deep-sea sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4375–4385. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4375-4384.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vogler P. Zur Analytik kondensierter Phosphate und organischer Phosphate bei limnischen Untersuchungen. Int Rev Ges Hydrobiol. 1966;51:775–785. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wallinger M M. M.Sc. thesis. Innsbruck, Austria: University of Innsbruck; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wiebe W J, Sheldon W M, Jr, Pomeroy L R. Bacterial growth in the cold: evidence for an enhanced substrate requirement. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:359–365. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.1.359-364.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wise M G, Shimkets L J, McArthur J V. Genetic structure of a lotic population of Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1791–1798. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.5.1791-1798.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]