Abstract

Simple Summary

Glioblastoma is the most common tumour that originates in the brain in adults. Most of the published data on glioblastoma are from patients in clinical trials who tend to be younger and fitter than the average patient. We therefore looked at patient demographic, tumour characteristics, and treatments received in a group of 490 real-world patients with glioblastoma to evaluate their survival, and to investigate whether we could find any factors that were associated with longer survival. Overall, the average survival of patients was 9 months. Patients tended to live longer if they were younger, had surgery, if they had further treatment after surgery (chemo- or radio-therapy), or if they had a tumour marker called MGMT promotor methylation.

Abstract

Background: IDH-wildtype glioblastoma is the most common malignant primary brain tumour in adults. As there is limited information on prognostic factors outside of clinical trials; thus, we conducted a retrospective study to characterise the glioblastoma population at our centre. Methods: Demographic, tumour molecular profiles, treatment, and survival data were collated for patients diagnosed with glioblastoma at our centre between July 2011 and December 2015. We used multivariate proportional hazard model associations with survival. Results: 490 patients were included; 60% had debulking surgery and 40% biopsy only. Subsequently, 56% had standard chemoradiotherapy, 25% had non-standard chemo/radio-therapy, and 19% had no further treatment. Overall survival was 9.2 months. In the multivariate analysis, longer survival was associated with debulking surgery vs. biopsy alone (14.9 vs. 8 months) (HR 0.54 [95% CI 0.41–0.70]), subsequent treatment after diagnosis (HR 0.12 [0.08–0.16]) (standard chemoradiotherapy [16.9 months] vs. non-standard regimens [9.2 months] vs. none [2.0 months]), tumour MGMT promotor methylation (HR 0.71 [0.58–0.87]), and younger age (hazard ratio vs. age < 50: 1.70 [1.26–2.30] for ages 50–59; 3.53 [2.65–4.70] for ages 60–69; 4.82 [3.54–6.56] for ages 70+). Conclusions: The median survival for patients with glioblastoma is less than a year. Younger age, debulking surgery, treatment with chemoradiotherapy, and MGMT promotor methylation are independently associated with longer survival.

Keywords: glioblastoma, MGMT, IDH, biomarker

1. Introduction

Glioblastoma is the most common malignant primary brain tumour in adults with an incidence of 3–4/100,000, and accounting for approximately half of all malignant primary brain tumours [1,2]. An initial diagnosis is typically made on the histology from tissue taken at surgical resection or stereotactic tumour biopsy. Diagnosis solely on the basis of imaging may occur if the risk of biopsy is too high, or if treatment is not contemplated-usually due to frailty [3]. Overall, over 90% of patients have a histological diagnosis, but this is less than 60% in those over 70 years old [4].

Standard treatment consists of surgical resection if possible, followed by radiotherapy and temozolomide chemotherapy, where, 60 Gray (Gy) of focal radiotherapy is administered in 2 Gy fractions. Temozolomide is given concurrently alongside radiotherapy and then for a further six months. Hypofractionated radiotherapy may be used in those patients not expected to tolerate standard radiotherapy [3,5]. Recently, the addition to standard therapy of tumour treating fields following radiotherapy has shown improved outcomes [6]. At relapse, typically, nitrosurea-based chemotherapy is given, although no therapies at relapse have demonstrated survival benefit in clinical trials.

Survival outcomes are bleak with a median survival in registry databases of 6–10 months [2,4] and 14.6–21.1 months in those treated with standard therapy in clinical trials [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Several demographic and molecular prognostic factors are recognised. However, there is limited information on the application of prognostic factors outside of the highly selected population within clinical trials, particularly in the temozolomide era, and there are few studies that include both molecular and clinical factors. We characterised the glioblastoma population treated at our centre, to determine the prognostic factors that can be identified at the time of diagnosis, and to assess the role of subsequent treatments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

All patients with primary glioblastoma that was histologically diagnosed using the 2007 WHO Classification of CNS Tumours (but with comprehensive molecular workup equivalent to glioblastoma IDH- (isocitrate dehydrogenase) mutant/IDH-wildtype in the 2016 Classification, and to Glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype/Grade 4 Astrocytoma, IDH-mutant within the recent 2021 WHO Classification) at our centre between January 2011 and December 2015 were identified using a pathology database [1,14,15,16]. Patients were excluded if they were not UK residents or if they had a previously identified primary brain tumour (either histologically or radiologically diagnosed). Patient demographics, treatment received, and date of death or last contact were collated from the Electronic Patient Record (EPR) at University College London Hospitals; 90% of patients of patients had died at the time of analysis, suggesting adequate capture of patient death records. The tumour molecular characteristics were collated via the centre’s pathology database (IDH1 (R132H) mutation determined by immunohistochemistry; MGMT (O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferasepromotor) methylation by methylation sensitive high resolution melting analysis; and Sanger sequencing for mutation hotspots in IDH1 and IDH2, copy number assays for the PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) locus on chromosome 10, EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor locus on chromosome 7, and chromosomal arms 1p and 19q by quantitative PCR [15]. Survival was defined as time from the date of diagnosis to death or last known contact.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

We performed two main sets of analyses. First, we investigated the impact of age, gender, and tumour biomarkers on survival in the full cohort (n = 490). We used Kaplan−Meier survival curves and estimates of median survival to describe univariate associations with survival. To investigate multivariate predictors of survival, we built a Cox proportional hazard models to predict survival, including age, gender, and all tumour biomarkers as candidate predictors. We used a forward stepwise variable selection with a p-value for inclusion of 0.05. To allow for estimation in the presence of missing data, we performed multiple imputation with chained equations. The imputation model included all candidate predictors, the outcome, and the cumulative hazard functions [17]. We used 10 imputed datasets.

Second, we described the association of treatment with survival. We restricted these analyses to patients in whom treatment was known. In standard practice, adjuvant chemoradiotherapy is initiated within six weeks of diagnosis; we were therefore unable to reliably define the treatment choice for each patient until this time because of our retrospective study design. We therefore included only patients surviving for a minimum of 6-weeks in these analyses (although sensitivity analyses including the first 6 weeks gave similar findings). We investigated the effect of treatment on survival using Cox model adjusted biomarkers found to be associated with outcome in the full patient cohort. We additionally tested for evidence that tumour biomarkers modified the effect of treatment using formal tests of interaction. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 14.2 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Patients

In total, 517 consecutively diagnosed patients with primary IDH-wildtype glioblastoma or Grade 4 IDH-mutant astrocytoma were identified; 27 patients who were not UK residents were excluded from all of the analyses, leaving a total of 490 patients. The median age at baseline was 59 years (Supplementary Materials Figure S1), 293 (59.8%) were male and 197 (40.2%) female, 51 (11% of 482 patients with available data) had IDH1 or IDH2 mutations detected in their tumours, and 234 (51% of 456) of patients had methylation of the MGMT promotor. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics.

| Patient Characteristics | Percentage (n/N with data) |

|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 59.2 ± 13.1 |

| Male | 59.8% (293/490) |

| Female | 40.2% (197/490) |

| Tumour molecular markers: | |

| IDH mutation | 10.6% (51/482) |

| MGMT promotor methylation | 51.3% (234/456) |

| Loss of PTEN locus | 45.6% (165/362) |

| EGFR amplification | 42.1% (151/359) |

| 1p and 19q LOH | 6.1% (15/245) |

| Debulking surgery | 60.0% (294/490) |

| Radio-/chemo-therapy1: | |

| Standard 2 | 56.1% (176/314) |

| Non-standard | 24.8% (78/314) |

| None | 19.1% (60/314) |

1 Among patients surviving 6 weeks. 2 RT 60–65 Gy/30# with TMZ chemotherapy.

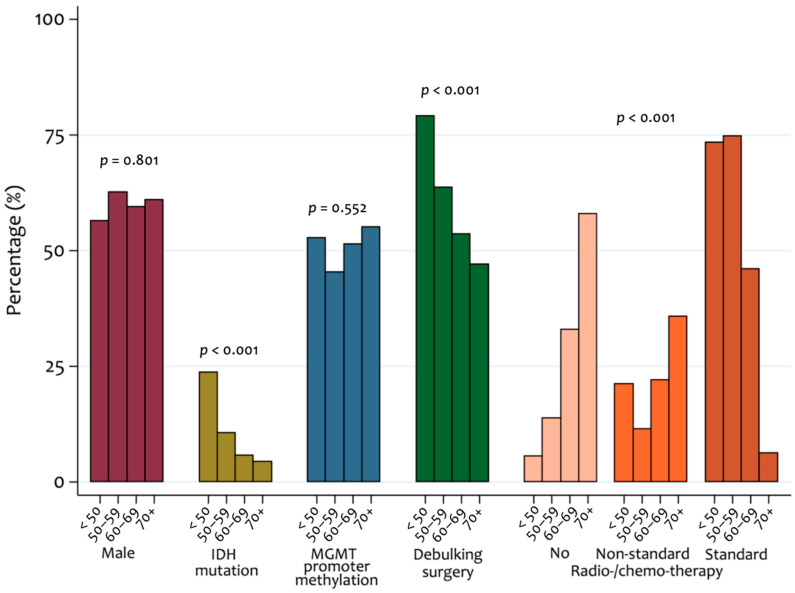

3.2. Treatment

It was found that 60% of patients had a primary debulking surgery and 40% of patients had biopsy only. Patients who had debulking surgery were younger than those who had biopsy only (median age 56 vs. 63 years, p < 0.001) (Figure 1 and Table S1). Thirty-six patients (7%) who died within six weeks of diagnosis were not included in the analyses of subsequent treatments. Subsequent treatment details were known in 314 patients (69%); where subsequent patient treatment was unknown, it was usually because patients were referred to other centres. Among these patients, 254 (81%) had further active therapy. Patients who had further active therapy tended to be younger (median age 58.8 years vs. 68.8, p < 0.001) and more frequently had debulking surgery (69% vs. 31%, p < 0.001) (Figure 1 and Table S1).

Figure 1.

Patient characteristics by age category. p-values indicate the significance of observed differences between age groups for each variable.

In those who had adjuvant therapy, 176 (69%) had radical radiotherapy (RT) (60–65 Gray in 30 fractions) with temozolomide (TMZ) chemotherapy (standard therapy), 43 (17%) had short course RT alone, 20 (8%) had radical RT alone, 10 (4%) had short course RT with TMZ, and 3 (1%) had TMZ alone. Patients receiving standard care tended to be younger than those receiving other active (non-standard) therapies (52.2 years vs. 60.2 years, p < 0.0001) (Figure 1 and Table S1).

At relapse, 57 (22%) of patients who had treatment after initial diagnosis had further surgery, 94 (37%) had second line chemotherapy, and 29 (11%) had third line chemotherapy. Of those who received chemotherapy in the relapsed setting, PCV (procarbazine, lomustine, vincristine) or lomustine monotherapy were most frequently used (in 71, 76% of patients), followed by bevacizumab (28, 30%), immune checkpoint inhibitors (20, 21%), temozolomide (7, 7%), carboplatin (7, 7%), or other agents (9, 10%).

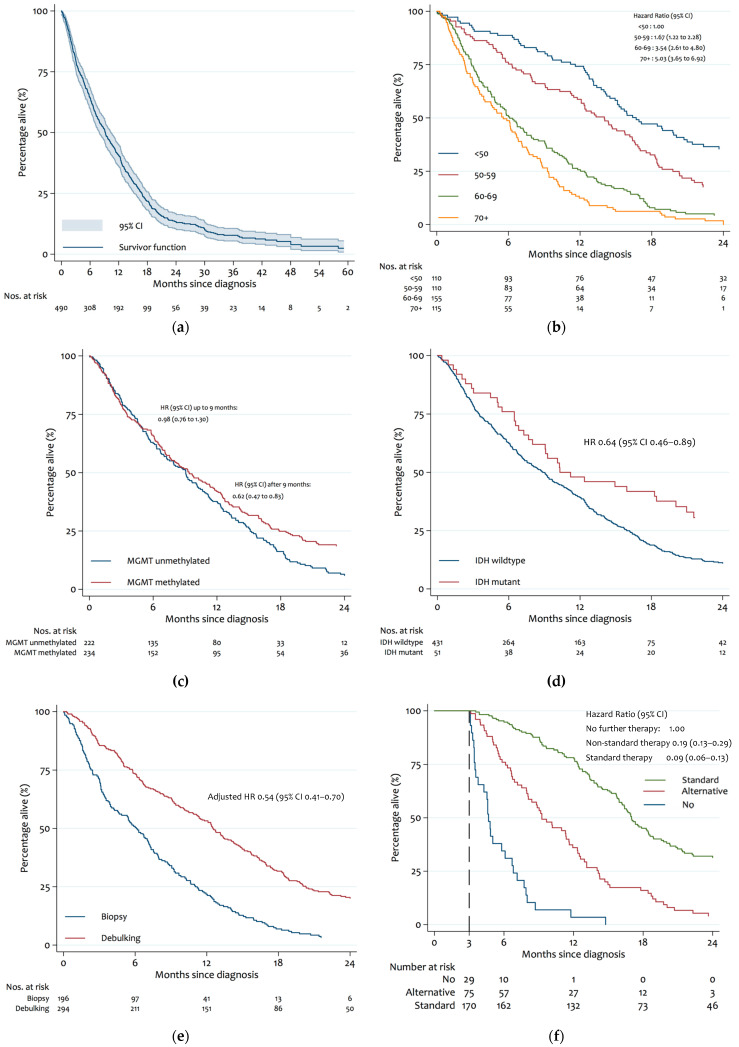

3.3. Survival Outcomes

Overall, the median survival was 9.2 months (IQR 7.9 to 10.3 months) (Figure 2a); the 12- and 24-month survival rates were 40.7% (95% CI 36.3–45.1) and 13.3% (95% CI 10.3–16.6), respectively.

Figure 2.

Kaplan−Meier survival estimates: (a) overall survival; (b) age at diagnosis; (c) tumour IDH mutation; (d) tumour MGMT methylation; (e) debulking surgery vs. biopsy alone; (f) chemo/radio-therapy after diagnosis.

In the univariate analyses of variables known at the time of diagnosis, advancing age was associated with a shorter survival (hazard ratio vs. age < 50: 1.70 [1.26–2.30] for ages 50–59; 3.53 [95% CI, 2.65–4.70] for ages 60–69; 4.82 [95% CI 3.54–6.56] for ages 70+), whereas an IDH mutation (HR 0.64 [0.46–0.89]) or MGMT promotor methylation (HR 0.80 [0.66–0.97]) were associated with longer survival (Table 2, Figure 2). Interestingly, the improved survival among patients with MGMT promoter methylation occurred almost exclusively after 9 months of follow up (Figure 2d). Compared with patients without MGMT promotor methylation, patients with methylated promotors had an almost identical risk of death during the first 9 months (HR = 0.98 [95% CI 0.76 to 1.30]), but a greatly reduced risk of death thereafter (HR = 0.62 [95% CI 0.47 to 0.83], p for interaction of hazard ratio over time = 0.121). Other tumour characteristics were not significantly associated with survival. In multivariate analyses, age and MGMT promoter methylation, but not IDH mutation, remained significant predictors of survival.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of treatment independent survival characteristics.

| Biomarker | Patients Included in Analysis |

N | Median Survival with Factor (95% CI) |

N | Median Survival without Factor (95% CI) |

Unadjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

Final Model 1 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (vs. Female) | 490 | 293 | 8.8 (7.2 to 10.2) | 229 | 9.7 (7.9 to 12.5) | 1.21 (1.00 to 1.47) | - |

| Age: | 490 | ||||||

| <50 | 110 | 110 | 16.7 (14.5 to 20.7) | - | - | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 50–59 | 110 | 110 | 14.0 (11.5 to 16.4) | - | - | 1.70 (1.26 to 2.30) | 1.67 (1.22 to 2.28) |

| 60–69 | 155 | 155 | 6.1 (4.9 to 7.5) | - | - | 3.53 (2.65 to 4.70) | 3.54 (2.61 to 4.80) |

| 70+ | 115 | 115 | 5.6 (3.9 to 6.7) | - | - | 4.82 (3.54 to 6.56) | 5.03 (3.65 to 6.92) |

| PTEN mutation | 362 | 165 | 9.2 (6.9 to 11.2) | 197 | 10.1 (8.0 to 12.5) | 1.14 (0.92 to 1.42) | - |

| EGFR amplification | 359 | 151 | 9.3 (7.9 to 11.3) | 208 | 9.4 (6.8 to 12.1) | 1.07 (0.86 to 1.34) | - |

| 1p and 19q LOH | 245 | 15 | 14.1 (2.3 to >24) | 230 | 10.5 (8.4 to 12.8) | 0.54 (0.29 to 1.00) | - |

| MGMT promotor methylation | 456 | 234 | 9.4 (7.5 to 11.6) | 222 | 9.1 (7.3 to 10.3) | 0.80 (0.66 to 0.97) | 0.71 (0.58 to 0.87) |

| IDH mutation | 482 | 51 | 10.3 (7.7 to 20.1) | 431 | 8.9 (7.5 to 10.1) | 0.64 (0.46 to 0.89) | - |

1 Final model chosen by stepwise variable selection on full data (n = 490) after fully conditional specification multiple imputation.

In further multivariate analyses restricted to the 314 patients in whom adjuvant treatment was known, debulking surgery and type of further treatment were both identified as predictors of survival (Table 3). Debulking surgery was associated with longer survival compared with biopsy only (adjusted HR 0.54 [95% CI 0.41–0.70]), with median survivals of 14.9 vs. 8.0 months in patients with debulking surgery and biopsy, respectively, and 24-month survival rates of 23.4% vs. 4.5%. When compared with no further therapy (median survival 2.0 months), non-standard therapy (median survival 9.2 months, adjusted HR = 0.19 [95% CI 0.13 to 0.29]) and standard therapy (median survival = 16.9 months, adjusted HR = 0.09 [0.06 to 0.13]) were associated with progressively longer survival. Twenty-four month survival rates among patients with no further therapy, non-standard therapy, and standard therapy were 0%, 3.8%, and 30.5%, respectively.

Table 3.

Survival characteristics by treatment.

| Characteristic | Patients Included in Analysis | Median Survival with Factor (95% CI) | Adjusted Hazard Ratio 1 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Debulking surgery: | 314 | ||

| No | 113 | 8.0 (6.7 to 9.7) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 201 | 14.9 (13.1 to 16.7) | 0.54 (0.41 to 0.70) |

| Radio-/chemo-therapy: | 314 | ||

| None | 176 | 2.8 (2.3 to 3.4) | 1.00 |

| Non-standard | 78 | 9.2 (7.5 to 11.4) | 0.19 (0.13 to 0.29) |

| Standard 2 | 60 | 16.9 (15.8 to 18.3) | 0.09 (0.06 to 0.13) |

1 Adjusted for MGMT and age, on full data (n = 314), after fully conditional specification multiple imputation. 2 RT 60–65 Gy/30# with TMZ chemotherapy.

In those who had treatment in the relapsed setting, having further chemotherapy was associated with longer survival [HR 0.39, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.54 (age/sex adjusted)] and having further surgery was associated with longer survival, although this was non-significant [HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.07 (age/sex adjusted)].

4. Discussion

This study confirms the major treatment-independent prognostic factors of age and tumour MGMT promotor methylation, and supports the role of debulking surgery and chemoradiotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma.

Younger age is consistently recognised as the most significant prognostic variable [4,18,19,20,21,22,23]. In our study, as well as being an independently positive prognostic factor, younger patients were more likely to have debulking surgery rather than biopsy, and were more likely to receive standard rather than non-standard or no therapies; both of which were associated with longer survival.

MGMT mediates a DNA repair mechanism, and epigenetic silencing through methylation of the MGMT promotor confers a positive prognosis and predicts response to temozolomide (an alkylating agent) in patients with glioblastoma [8,11,18,24,25]. In patients unfit for standard therapy such as the elderly, MGMT promotor methylation is frequently used to stratify whether patients should have chemotherapy, an approach that is supported by clinical trials [26,27]. Our study supports these findings, and the apparent divergence of the survival curves after 9 months supports a potential treatment related effect.

In our study, the presence of an IDH mutation was associated with longer survival, but was also associated with younger age (49 years with vs. 60 years without). It was not independently associated with survival in adjusted models, although statistical power to detect an association was limited because only 10% of patients had the IDH mutation. IDH mutation is an early event in tumourgenesis, and IDH mutant tumours are considered clinically and genetically distinct from those that are IDH wild type. They were first classified separately within the 2016 WHO Classification (as glioblastoma, IDH-mutant) and have been further distinguished as a separate entity within the recent 2021 WHO Classification, which removed the nomenclature glioblastoma entirely, terming them as astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, CNS WHO grade 4 [1,16,28,29]. This is in keeping with the long-held view that they are considered to represent high grade transformation from a lower grade lesion, and most studies and meta-analyses have identified IDH mutation as an independently favourable prognostic factor [30,31,32,33,34,35], although more complex interactions between age and molecular groups have been proposed [36].

Our study is limited by the retrospective study design. We were unable to collect and statistically adjust for some known prognostic indicators of survival; as the selection bias of patients to different treatments is so strong, the extent to which survival outcomes are driven by differences in treatments is unclear. Performance status is consistently recognised as an independent prognostic variable [18,19,20,21,22,23]. No standardised performance status was available in the vast majority of our patients and we felt retrospective designation risked unacceptable bias. While resection over biopsy is an accepted prognostic marker and is supported by our study, and it is generally (although not always) agreed that the complete resection is favourable over partial resection, the degree of resection required to offer improved survival remains unestablished [37,38,39]. However, it was not standard practice in our centre to perform post-operative imaging at the time of this study, and so our data cannot address this important research question. We attempted to account for these limitations by performing both treatment-independent and treatment-dependent analyses (Table S2), which both determined MGMT promotor methylation and younger age as independent prognostic variables in our cohort.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, in this single-institution retrospective cohort review of 490 consecutively newly diagnosed patients with glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype, CNS WHO grade 4, and astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, CNS WHO grade 4, the median survival from diagnosis was 9.2 months. The median survival in patients who received debulking surgery at diagnosis was 14.9 months vs. 8.0 months in those who had a biopsy only. Following diagnosis, median survival in those treated with standard therapy (radical radiotherapy with temozolomide chemotherapy) was 16.9 months, compared with 9.2 months for those who received other regimens of radiotherapy or chemotherapy, and 2.8 months in those patients who received no subsequent therapy. Multivariate analysis treatment-independent variables at diagnosis identified younger age and tumour MGMT promotor methylation to be positive prognostic markers.

Acknowledgments

P.M. is supported by the University College Hospital/University College London Biomedical Research Centre and the National Brain Appeal. S.B. is supported by the Department of Health’s NIHR Biomedical Research Centre’s funding scheme to UCLH.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers14133161/s1. Figure S1: Age at diagnosis. Table S1: Age at diagnosis by clinical characteristics. Table S2: Final Survival Model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.F.B. and P.M.; Data curation, N.F.B. and D.O.; Formal analysis, J.T. and J.G.; Methodology, J.T., J.G. and P.M.; Project administration, N.F.B. and D.O.; Resources, S.B.; Supervision, N.K., N.F. and P.M.; Writing—original draft, N.F.B.; Writing—review & editing, N.F.B., D.O., J.T., J.G., N.K., S.B., N.F. and P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it did not meet the NHS Health Research Authority and UKRI Medical Research Council criteria for research.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Louis D.N., Perry A., Reifenberger G., von Deimling A., Figarella-Branger D., Cavenee W.K., Ohgaki H., Wiestler O.D., Kleihues P., Ellison D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostrom Q.T., Gittleman H., Fulop J., Liu M., Blanda R., Kromer C., Wolinsky Y., Kruchko C., Barnholtz-Sloan J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2008–2012. Neuro-Oncology. 2015;17((Suppl. 4)):iv1–iv62. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weller M., van den Bent M., Tonn J.C., Stupp R., Preusser M., Cohen-Jonathan-Moyal E., Henriksson R., Rhun E.L., Balana C., Chinot O., et al. European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of adult astrocytic and oligodendroglial gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e315–e329. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brodbelt A., Greenberg D., Winters T., Williams M., Vernon S., Collins V.P., National Cancer Information Network Brain Tumour Group Glioblastoma in England: 2007–2011. Eur. J. Cancer. 2015;51:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stupp R., Brada M., van den Bent M.J., Tonn J.C., Pentheroudakis G., Group E.G.W. High-grade glioma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol./ESMO. 2014;25((Suppl. 3)):iii93–iii101. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stupp R., Hegi M.E., Idbaih A., Steinberg D.M., Lhermitte B., Read W., Toms S.A., Barnett G.H., Nicholas G., Kim C., et al. CT007—Tumor treating fields added to standard chemotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma (GBM): Final results of a randomized, multi-center, phase III trial; Proceedings of the AACR Annual Meeting 2017; Washington, DC, USA. 18–22 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chinot O.L., Wick W., Mason W., Henriksson R., Saran F., Nishikawa R., Carpentier A.F., Hoang-Xuan K., Kavan P., Cernea D., et al. Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy-temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:709–722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert M.R., Dignam J.J., Armstrong T.S., Wefel J.S., Blumenthal D.T., Vogelbaum M.A., Colman H., Chakravarti A., Pugh S., Won M., et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:699–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson D.R., O’Neill B.P. Glioblastoma survival in the United States before and during the temozolomide era. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2012;107:359–364. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0749-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malkki H. Trial Watch: Glioblastoma vaccine therapy disappointment in Phase III trial. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2016;12:190. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stupp R., Hegi M.E., Mason W.P., van den Bent M.J., Taphoorn M.J., Janzer R.C., Ludwin S.K., Allgeier A., Fisher B., Belanger K., et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stupp R., Taillibert S., Kanner A.A., Kesari S., Steinberg D.M., Toms S.A. Maintenance therapy with tumor-treating fields plus temozolomide vs temozolomide alone for glioblastoma: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:2535–2543. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.16669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilbert M.R., Wang M., Aldape K.D., Stupp R., Hegi M.E., Jaeckle K.A., Armstrong T.S., Wefel J.S., Won M., Blumenthal D.T., et al. Dose-dense temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma: A randomized phase III clinical trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31:4085–4091. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louis D.N., Ohgaki H., Wiestler O.D., Cavenee W.K., Burger P.C., Jouvet A., Scheithauer B.W., Kleihues P. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaunmuktane Z., Capper D., Jones D.T.W., Schrimpf D., Sill M., Dutt M., Suraweera N., Pfister S.M., von Deimling A., Brandner S. Methylation array profiling of adult brain tumours: Diagnostic outcomes in a large, single centre. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2019;7:24. doi: 10.1186/s40478-019-0668-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louis D.N., Perry A., Wesseling P., Brat D.J., Cree I.A., Figarella-Branger D., Hawkins C., Ng H.K., Pfister S.M., Reifenberger G., et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro-Oncology. 2021;23:1231–1251. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White I.R., Royston P., Wood A.M. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat. Med. 2011;30:377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weller M., Felsberg J., Hartmann C., Berger H., Steinbach J.P., Schramm J., Westphal M., Schackert G., Simon M., Tonn J.C., et al. Molecular predictors of progression-free and overall survival in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: A prospective translational study of the German Glioma Network. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:5743–5750. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filippini G., Falcone C., Boiardi A., Broggi G., Bruzzone M.G., Caldiroli D., Farina R., Farinotti M., Fariselli L., Finocchiaro G., et al. Prognostic factors for survival in 676 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed primary glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology. 2008;10:79–87. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stark A.M., van de Bergh J., Hedderich J., Mehdorn H.M., Nabavi A. Glioblastoma: Clinical characteristics, prognostic factors and survival in 492 patients. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2012;114:840–845. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J., Wang M., Won M., Shaw E.G., Coughlin C., Curran W.J., Jr., Mehta M.P. Validation and simplification of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group recursive partitioning analysis classification for glioblastoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011;81:623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamborn K.R., Chang S.M., Prados M.D. Prognostic factors for survival of patients with glioblastoma: Recursive partitioning analysis. Neuro-Oncology. 2004;6:227–235. doi: 10.1215/S1152851703000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gittleman H., Lim D., Kattan M.W., Chakravarti A., Gilbert M.R., Lassman A.B., Lo S.S., Machtay M., Sloan A.E., Sulman E.P., et al. An independently validated nomogram for individualized estimation of survival among patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: NRG Oncology RTOG 0525 and 0825. Neuro-Oncology. 2017;19:669–677. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang K., Wang X.Q., Zhou B., Zhang L. The prognostic value of MGMT promoter methylation in Glioblastoma multiforme: A meta-analysis. Fam. Cancer. 2013;12:449–458. doi: 10.1007/s10689-013-9607-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hegi M.E., Diserens A.C., Gorlia T., Hamou M.F., De T.N., Weller M., Kros J.M., Hainfellner J.A., Mason W., Mariani L., et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wick W., Platten M., Meisner C., Felsberg J., Tabatabai G., Simon M., Nikkhah G., Papsdorf K., Steinbach J.P., Sabel M., et al. Temozolomide chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly: The NOA-08 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:707–715. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70164-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malmström A., Grønberg B.H., Marosi C., Stupp R., Frappaz D., Schultz H., Abacioglu U., Tavelin B., Lhermitte B., Hegi M.E., et al. Temozolomide versus standard 6-week radiotherapy versus hypofractionated radiotherapy in patients older than 60 years with glioblastoma: The Nordic randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:916–926. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan H., Parsons D.W., Jin G., McLendon R., Rasheed B.A., Yuan W., Kos I., Batinic-Haberle I., Jones S., Riggins G.J., et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:765–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brat D.J., Aldape K., Colman H., Figrarella-Branger D., Fuller G.N., Giannini C., Holland E.C., Jenkins R.B., Kleinschmidt-DeMasters B., Komori T., et al. cIMPACT-NOW update 5: Recommended grading criteria and terminologies for IDH-mutant astrocytomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;139:603–608. doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02127-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia L., Wu B., Fu Z., Feng F., Qiao E., Li Q., Sun C., Ge M. Prognostic role of IDH mutations in gliomas: A meta-analysis of 55 observational studies. Oncotarget. 2015;6:17354–17365. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng H.B., Yue W., Xie C., Zhang R.Y., Hu S.S., Wang Z. IDH1 mutation is associated with improved overall survival in patients with glioblastoma: A meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. J. Int. Soc. Oncodev. Biol. Med. 2013;34:3555–3559. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0934-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parsons D.W., Jones S., Zhang X., Lin J.C., Leary R.J., Angenendt P., Mankoo P., Carter H., Siu I.M., Gallia G.L., et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen J.-R., Yao Y., Xu H.-Z., Qin Z.-Y. Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (IDH)1/2 Mutations as Prognostic Markers in Patients With Glioblastomas. Medicine. 2016;95:e2583. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berghoff A.S., Stefanits H., Woehrer A., Heinzl H., Preusser M., Hainfellner J.A. Clinical neuropathology practice guide 3-2013: Levels of evidence and clinical utility of prognostic and predictive candidate brain tumor biomarkers. Clin. Neuropathol. 2013;32:148–158. doi: 10.5414/NP300646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nobusawa S., Watanabe T., Kleihues P., Ohgaki H. IDH1 mutations as molecular signature and predictive factor of secondary glioblastomas. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2009;15:6002–6007. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eckel-Passow J.E., Lachance D.H., Molinaro A.M., Walsh K.M., Decker P.A., Sicotte H., Pekmezci M., Rice T., Kosel M.L., Smirnov I.V., et al. Glioma Groups Based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT Promoter Mutations in Tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:2499–2508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown T.J., Brennan M.C., Li M., Church E.W., Brandmeir N.J., Rakszawski K.L., Patel A.S., Rizk E.B., Suki D., Sawaya R., et al. Association of the Extent of Resection With Survival in Glioblastoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1460–1469. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Almenawer S.A., Badhiwala J.H., Alhazzani W., Greenspoon J., Farrokhyar F., Yarascavitch B., Algird A., Kachur E., Cenic A., Sharieff W., et al. Biopsy versus partial versus gross total resection in older patients with high-grade glioma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuro-Oncology. 2015;17:868–881. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hess K.R. Extent of resection as a prognostic variable in the treatment of gliomas. J. Neuro-Oncol. 1999;42:227–231. doi: 10.1023/A:1006118018770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.