Abstract

BACKGROUND

The introduction of minimal invasive principles in colorectal surgery was a major breakthrough, resulting in multiple clinical benefits, at the cost, though, of a notably steep learning process. The development of structured nation-wide training programs led to the easier completion of the learning curve; however, these programs are not yet universally available, thus prohibiting the wider adoption of laparoscopic colorectal surgery.

AIM

To display our experience in the learning curve status of laparoscopic colorectal surgery under a non-structured training setting.

METHODS

We analyzed all laparoscopic colorectal procedures performed in the 2012-2019 period under a non-structured training setting. Cumulative sum analysis and change-point analysis (CPA) were introduced.

RESULTS

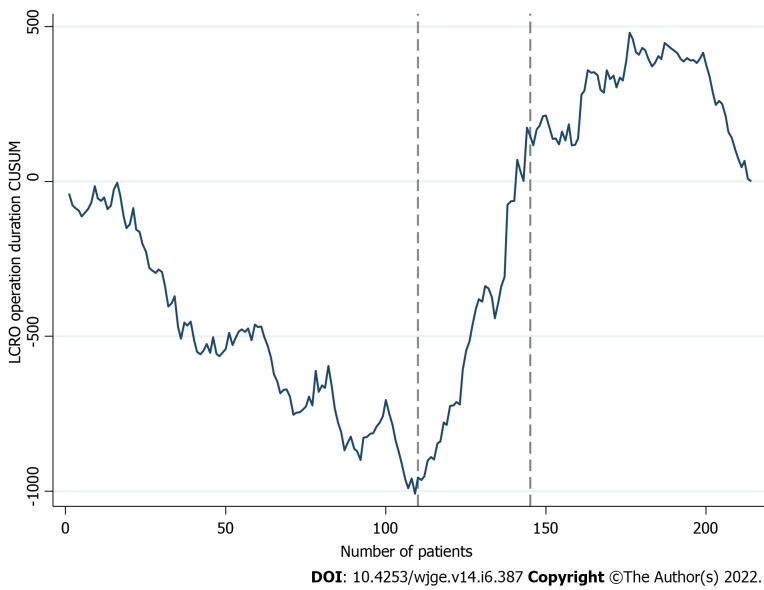

Overall, 214 patients were included. In terms of operative time, CPA identified the 110th case as the first turning point. A plateau was reached after the 145th case. Subgroup analysis estimated the 58th for colon and 52nd case for rectum operations as the respective turning points. A learning curve pattern was confirmed for pathology outcomes, but not in the conversion to open surgery and morbidity endpoints.

CONCLUSION

The learning curves in our setting validate the comparability of the results, despite the absence of National or Surgical Society driven training programs.

Keywords: Colorectal, Education, Gastrointestinal, Laparoscopy, Outcomes

Core Tip: In terms of operative time, the learning curve of a dedicated colorectal surgical team consists of three phases. Change point analysis identified the 110th case as the separation key-point of the first two phases. A plateau was reached after the 145th case. Although we were able to confirm the presence of a learning curve pattern in the histopathological endpoints, this was not the case for the open conversion and morbidity outcomes. Formal training program initiatives are necessary for the safe and efficient implementation of laparoscopic colorectal operations.

INTRODUCTION

The introduction of minimal invasive principles in colorectal surgery, during the last two decades, was a major breakthrough[1]. Multiple studies confirmed the advantages of a minimal invasive approach, including reduced analgesic requirements, fewer complications, and a shorter recovery period[2].

Nonetheless, the accrual of these benefits depends on the completion of an elongated learning process[3-5]. Due to the complexity of laparoscopic colorectal operations (LCRO) and the innate dexterity requirements, the accumulation of the respective surgical skills is quite demanding[6-9]. Thus, like other multi-leveled procedures, learning curves were universally adopted for the assessment of surgical competency[10-13].

Although there is a remarkable heterogeneity in the turning points of learning curves for LCRO, current evidence suggests that at least 100 consecutive operations are needed to obtain proficiency[14-17]. During the initial phase, an analogous variation in endpoints, such as morbidity and open conversion rates, is expected[3,18-24].

The determination of the individual elements that contribute to the elongation of the learning curve was a major step towards the establishment of a safety and training culture in laparoscopic colorectal surgery[14,23,25]. Subsequently, the development of structured nation-wide training programs expedited the completion of the respective learning curves[26-28]. Among the various components of these programs are the formation of specialized colorectal surgical groups, the conduction of hands-on courses, and the introduction of mentor guidance during the first cases[26-29]. Unfortunately, these initiatives are not yet implemented in all health systems, thus restraining the efficient dissemination of the minimal invasive principles in colorectal surgery[9,24,30].

Therefore, we designed this study to analyze the laparoscopic colorectal surgery learning curves, outside a formal national or surgical society driven training program.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is a retrospective analysis of a prospectively collected database. Between January 2012 and December 2019, data from all laparoscopic colorectal resections performed by a specialized colorectal surgical team, were recorded in an institutional database. All patients, prior to their inclusion, provided informed consent for data recording, analyses, and future publication. This study report follows the STROBE guidelines[31].

The surgical team consisted of two consultant surgeons with previous experience in laparoscopic general surgery (G.T. and I.B.). Six months prior to the onset of the study, the surgeons attended both national and international specialized formal courses and performed their initial operations under proctoring. However, this learning process was not based on any national or scientific society training program, due to the absence of such initiatives in Greece. The surgical team was also supported by a dedicated pathology team responsible for the evaluation of the resected specimens.

All operations were performed with four or five trocars. Dissection was completed using an energy source. A medial to lateral approach was implemented in all patients. In case of malignancy, the appropriate oncological principles (Complete mesocolic excision/ Total mesorectal excision CME/TME and Central vascular ligation CVL) were followed. Splenic flexure mobilization was always performed in left sided tumors. A structured pathology report was also provided.

All adult patients (age > 18 years) submitted to elective or semi-elective laparoscopic colorectal surgery for benign or malignant disease were deemed as eligible. The following exclusion criteria were considered: (1) Age < 18 years; (2) American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score > III; (3) Emergency surgery, e.g., for peritonitis and perforation; and (4) Cases not performed by the above-mentioned surgical team.

The primary endpoint of our study was to identify the learning curve status of the operation duration in patients submitted to LCRO. Subgroup analysis for colon (LCO) and rectal operations (LRO) was also performed. Secondary endpoints included operative characteristics (complication and open conversion rates) and specimen pathology quality outcomes. Postoperative complications were any Clavien Dindo ≥ 2 adverse events. The complexity of each operation was graded on the basis of the Miskovic et al[23] classification system. Data extraction was completed by a group of senior researchers (I.M., G.V., and A.V.).

Statistical analysis

Prior to any statistical analysis, a Shapiro-Wilk normality test was applied to all continuous variables. Since normality was not proven, a non-parametric approach was implemented. Mann-Whitney U test was used for the comparison of continuous variables. Kruskal Wallis H test was applied in multiple comparisons of continuous data. Categorical variables were analyzed by Pearson chi square test, while proportions were evaluated by the Z test. Correlation was assessed through a Spearman’s rank-order correlation test.

To identify variations in the changing rate of the studied variables and plot the respective learning curve (LC), cumulative sum (CUSUM) analysis was performed. CUSUM analysis was applied to all above-mentioned endpoints.

The CUSUM analysis plots that confirmed a significant LC pattern, were further evaluated by change-point analysis (CPA). CPA allows the identification of even small trend shifts and provides the respective statistical significance of each change. The CPA analysis incorporated the application of 1000 bootstraps, and a 50% confidence level (CL) for candidate changes.

The acceptable rate of missing values was < 10%. Missing data were handled using the multiple imputation technique. Continuous data are reported in the form of median (interquartile range), whereas categorical variables are provided as number (percentage). Significance was considered at the level of P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were completed with STATA v.13 and SPSS v.23 software.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Overall, 214 LCRO were included in the study. More specifically, 76 (35.5%) right colectomies, 31 (14.5%) left colectomies, 26 (12.2%) sigmoidectomies, 72 (33.6%) low anterior resections (LAR), 7 (3.3%) ultra-LAR, and 2 (2.4%) abdominoperineal resections (APR) were performed. Most of the cases displayed a level 1 (54.2%) or 2 (38.2%) complexity. Mean operation duration was 180 and 200 min for LCO and LRO, respectively. The results of the correlation analyses are reported in Supplementary Tables. The overall complication rate was 22.9%. Negative resection margins were confirmed in 95.3% of the patients. A mesocolic and mesorectal resection plane was achieved in 86.4% and 88.8% of cases, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

|

|

Total

|

Colon operations

|

Rectal operations

|

P

value

|

|

| n | 214 | 133 | 81 | ||

| Sex | Male | 128 (59.8%) | 78 (58.6%) | 50 (61.7%) | NS |

| Female | 86 (40.2%) | 55 (41.4%) | 31 (38.3%) | ||

| Age (yr) | 70 (13) | 71 (14) | 68 (13) | NS | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27 (5) | 28 (5) | 26.5 (4) | NS | |

| ASA score | I | 71 (33.2%) | 35 (26.3%) | 36 (44.4%) | 0.021 |

| II | 117 (54.7%) | 79 (59.4%) | 38 (46.9%) | ||

| III | 26 (12.1%) | 19 (14.3%) | 7 (8.6%) | ||

| Diagnosis | Malignancy | 206 (96.3%) | 125 (94%) | 81 (100%) | NS |

| Diverticulitis | 6 (2.8%) | 6 (4.5%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Volvulus | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Crohn’s disease | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Previous operation | 17 (7.9%) | 13 (9.8%) | 4 (4.9%) | NS | |

| T | 1 | 51 (24.8%) | 33 (26.4%) | 18 (22.2%) | NS |

| 2 | 63 (30.6%) | 39 (31.2%) | 24 (29.6%) | ||

| 3 | 85 (41.3%) | 47 (37.6%) | 38 (46.9%) | ||

| 4 | 7 (3.4%) | 6 (4.8%) | 1 (1.2%) | ||

| N | 0 | 153 (74.3%) | 89 (71.2%) | 64 (79%) | NS |

| 1 | 42 (20.4%) | 30 (24%) | 12 (14.8%) | ||

| 2 | 11 (5.3%) | 6 (4.8%) | 5 (6.2%) | ||

| M | 0 | 205 (99.5%) | 125 (100%) | 80 (98.8%) | NS |

| 1 | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.2%) | ||

| Neoadjuvant modality | 19 (9.2%) | 2 (1.6%) | 17 (20%) | < 0.001 | |

| Complexity level | 1 | 116 (54.2%) | 74 (55.6%) | 42 (51.9%) | 0.022 |

| 2 | 82 (38.2%) | 44 (33.1%) | 38 (46.9%) | ||

| 3 | 6 (2.8%) | 6 (4.5%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 4 | 10 (4.7%) | 9 (6.8%) | 1 (1.2%) | ||

| Operation | Right colectomy | 76 (35.5%) | 76 (57.1%) | - | < 0.001 |

| Left colectomy | 31 (14.5%) | 31 (23.3%) | - | ||

| Sigmoidectomy | 26 (12.1%) | 26 (19.5%) | - | ||

| Low anterior resection | 72 (33.6%) | - | 72 (88.9%) | ||

| Ultra-low anterior resection | 7 (3.3%) | - | 7 (8.6%) | ||

| Abdominoperineal resection | 2 (1%) | - | 2 (2.4%) | ||

| Emergency status | Elective | 212 (99.1%) | 131 (98.5%) | 81 (100%) | NS |

| Semi-elective | 2 (0.9%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Laparoscopic approach | Totally laparoscopic | 182 (85%) | 127 (95.5%) | 55 (67.9%) | < 0.001 |

| Laparoscopy assisted | 32 (15%) | 6 (4.5%) | 26 (32.1%) | ||

| Preoperative optimization | Bowel preparation | 191 (89.3%) | 112 (84.2%) | 79 (97.5%) | 0.002 |

| Antibiotic preparation | 206 (96.3%) | 127 (95.5%) | 79 (97.5%) | NS | |

| Tattoo | 51 (23.8%) | 28 (21.1%) | 23 (28.4%) | NS | |

| Extraction site | Pfannenstiel | 95 (44.4%) | 40 (30.1%) | 55 (67.9%) | < 0.001 |

| Subumbilical | 19 (8.9%) | 4 (3%) | 15 (18.5%) | ||

| Transumbilical | 100 (46.7%) | 89 (66.9%) | 11 (13.6%) | ||

| Anastomosis | Stapled | 159 (75%) | 80 (60.2%) | 79 (100%) | < 0.001 |

| Handsewn | 53 (25%) | 53 (39.8%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Intracorporeal | 112 (52.8%) | 50 (37.6%) | 62 (78.4%) | < 0.001 | |

| Extracorporeal | 100 (47.1%) | 83 (62.4%) | 17 (21.5%) | ||

| Protective stoma | 66 (30.8%) | 9 (6.8%) | 57 (70.4%) | < 0.001 | |

| Operation duration (min) | 180 (51) | 180 (50) | 200 (60) | < 0.001 | |

| Open conversion | 20 (9.3%) | 6 (4.5%) | 14 (17.3%) | 0.002 | |

| Transfusion | 8 (3.7%) | 4 (3%) | 4 (4.9%) | NS | |

| Tumor diameter (cm) | 3 (2.2) | 3 (2) | 3.75 (2.5) | NS | |

| Specimen length (cm) | 20 (9) | 21 (7) | 15 (7) | < 0.001 | |

| Distal margin (cm) | 5 (4.35) | 5.25 (3.5) | 4.5 (4.25) | 0.01 | |

| Lymph nodes | 17 (12) | 19 (13) | 15 (11) | 0.004 | |

| Lymph node ratio | 0 (2.3) | 0 (4) | 0 (0) | NS | |

| Histological grade | 1 | 40 (19.4%) | 20 (16%) | 20 (24.7%) | NS |

| 2 | 135 (65.5%) | 89 (71.2%) | 46 (56.8%) | ||

| 3 | 31 (15%) | 16 (12.8%) | 15 (18.5%) | ||

| R status | 0 | 204 (95.3%) | 124 (99.2%) | 80 (98.8%) | NS |

| 1 | 2 (0.9%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (1.2%) | ||

| Resection plane | Mesocolic/mesorectal | 183 (88.8%) | 108 (86.4%) | 75 (88.8%) | NS |

| Intramesocolic/intramesorectal | 19 (9.2%) | 14 (11.2%) | 5 (6.2%) | ||

| Muscularis propria | 4 (1.9%) | 3 (2.4%) | 1 (1.2%) | ||

| Extramural vascular invasion | 54 (26.2%) | 33 (26.4%) | 21 (25.9%) | NS | |

| Perineural invasion | 21 (10.2%) | 13 (10.4%) | 8 (9.9%) | NS | |

| Mucous | Focal | 29 (14.1%) | 20 (16%) | 9 (11.1%) | NS |

| Diffuse | 20 (9.7%) | 15 (12%) | 5 (6.2%) | ||

| Complications | Total | 49 (22.9%) | 33 (24.8%) | 16 (19.8%) | NS |

| Wound infection | 9 (4.2%) | 5 (3.8%) | 4 (4.9%) | NS | |

| Wound dehiscence | 2 (0.9%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Leak | 14 (6.5%) | 10 (7.5%) | 4 (4.9%) | ||

| Postoperative ileus | 11 (5.1%) | 8 (6%) | 3 (3.7%) | ||

| Urinary tract infection | 2 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.5%) | ||

| Urinary retention | 2 (0.9%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (1.2%) | ||

| Bleeding | 3 (1.4%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (2.5%) | ||

| Pulmonary embolism | 2 (0.9%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| ARDS | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.2%) | ||

| Other | 4 (1.9%) | 4 (3%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Relaparotomy | 11 (5.1%) | 8 (6%) | 3 (3.7%) | NS | |

| ICU | 8 (3.7%) | 5 (3.8%) | 3 (3.7%) | NS | |

| Mortality | 5 (2.3%) | 4 (3%) | 1 (1.2%) | NS | |

| Length of hospital stay (d) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | NS | |

| Follow-up (mo) | 2 (3.75) | 2 (5.8) | 2 (2.5) | NS | |

NS: Non-significant; BMI: Body mass index; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; ARDS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome; ICU: Intensive care unit.

Figure 1 illustrates the LCRO learning curve, in terms of operation duration. A declining trend of the CUSUM plot, until the 109th case was noted, followed by an upwards shift and a maximum value at the 176th case. CPA confirmed the 110th (CL: 100%) and 145th (CL: 99%) case turning points. On the basis of these findings (Table 2), the LCRO LC was subdivided in three distinct phases (phase I: 1 to 109 operations; phase II: 110 to 144 operations; and phase III: 145 to 214 operations).

Figure 1.

Cumulative sum analysis of operation duration in laparoscopic colorectal operations. CUSUM: Cumulative sum; LCRO: Laparoscopic colorectal operations.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics in different phases of the learning curve

|

|

Overall

|

Colon

|

Rectal

|

|||||||||

| Phase I (1-109) | Phase II (110-144) | Phase III (145-214) | P value | Phase I (1-57) | Phase II (58-133) | P value | Phase I (1-51) | Phase II (52-81) | P value | |||

| N | 109 | 35 | 70 | 57 | 76 | 51 | 30 | |||||

| Sex | Male | 68 (62.4%) | 24 (68.6%) | 36 (51.4%) | NS | 37 (64.9%) | 41 (53.9%) | NS | 30 (58.8%) | 20 (66.7%) | NS | |

| Female | 41 (37.6%) | 11 (31.4%) | 34 (48.6%) | 20 (35.1%) | 35 (46.1%) | 21 (41.2%) | 10 (33.3%) | |||||

| Age (yr) | 71.5 (12) | 70 (13) | 69.5 (14) | NS | 72 (14) | 71 (13) | NS | 69.5 (12) | 67 (16) | NS | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27 (5) | 28 (4) | 27 (5) | NS | 28 (6) | 28 (5) | NS | 26 (3) | 27.5 (6) | NS | ||

| ASA score | I | 36 (33%) | 13 (37.1%) | 22 (31.4%) | NS | 14 (24.6%) | 21 (27.6%) | NS | 21 (41.2%) | 15 (50%) | NS | |

| II | 62 (56.9%) | 16 (45.7%) | 39 (55.7%) | 35 (61.4%) | 44 (57.9%) | 27 (52.9%) | 11 (36.7%) | |||||

| III | 11 (10.1%) | 6 (17.1%) | 9 (12.9%) | 8 (14%) | 11 (14.5%) | 3 (5.9%) | 4 (13.3%) | |||||

| Diagnosis | Malignancy | 106 (97.2%) | 34 (97.1%) | 66 (94.3%) | NS | 54 (94.7%) | 71 (93.4%) | NS | 51 (100%) | 30 (100%) | - | |

| Diverticulitis | 2 (1.8%) | 1 (2.9%) | 3 (4.3%) | 2 (3.5%) | 4 (5.3%) | - | - | |||||

| Volvulus | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | - | - | |||||

| Crohn’s disease | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.3%) | - | - | |||||

| Previous operation | 13 (11.9%) | 2 (5.7%) | 2 (2.9%) | NS | 9 (15.8%) | 4 (5.3%) | 0.04 | 4 (7.8%) | 0 (0%) | NS | ||

| T | 1 | 24 (22.6%) | 6 (17.6%) | 21 (31.8%) | NS | 12 (22.6%) | 21 (29.2%) | NS | 12 (23.5%) | 6 (20%) | NS | |

| 2 | 34 (32.1%) | 7 ( (20.6%) | 22 (33.3%) | 16 (30.2%) | 23 (31.9%) | 18 (35.3%) | 6 (20%) | |||||

| 3 | 43 (40.6%) | 20 (58.8%) | 22 (33.3%) | 21 (39.6%) | 26 (36.1%) | 20 (39.2%) | 18 (60%) | |||||

| 4 | 5 (4.7%) | 1 (2.9%) | 1 (1.5%) | 4 (7.5%) | 2 (2.8%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |||||

| N | 0 | 77 (74.5%) | 25 (73.5%) | 49 (74.2%) | NS | 36 (67.9%) | 53 (73.6%) | NS | 41 (80.4%) | 23 (76.7%) | NS | |

| 1 | 23 (21.7%) | 6 (17.6%) | 13 (19.7%) | 16 (30.2%) | 14 (19.4%) | 6 (13.7%) | 5 (16.7%) | |||||

| 2 | 4 (3.8%) | 3 (8.8%) | 4 (6.1%) | 1 (1.9%) | 5 (6.9%) | 3 (5.9%) | 2 (6.7%) | |||||

| M | 0 | 106 (100%) | 34 (100%) | 65 (98.5%) | NS | 53 (100%) | 72 (100%) | - | 51 (100%) | 29 (96.7%) | NS | |

| 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.5%) | - | - | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.3%) | |||||

| Neoadjuvant modality | 6 (5.5%) | 5 (14.3%) | 8 (11.4%) | NS | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.6%) | NS | 6 (11.8%) | 11 (36.7%) | 0.008 | ||

| Complexity level | 1 | 50 (54.1%) | 13 (37.1%) | 44 (62.9%) | NS | 29 (50.9%) | 45 (59.2%) | NS | 30 (58.8%) | 12 (40%) | NS | |

| 2 | 42 (38.5%) | 20 (57.1%) | 20 (28.6%) | 21 (36.8%) | 23 (30.3%) | 20 (39.2%) | 18 (60%) | |||||

| 3 | 2 (1.8%) | 1 (2.9%) | 3 (4.3%) | 2 (3.5%) | 4 (5.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||||

| 4 | 6 (5.5%) | 1 (2.9%) | 3 (4.3%) | 5 (8.8%) | 4 (5.3%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |||||

| Operation | Right colectomy | 34 (31.2%) | 13 (37.1%) | 29 (41.4%) | NS | 34 (59.6%) | 42 (55.3%) | NS | - | - | NS | |

| Left colectomy | 10 (9.2%) | 6 (17.1%) | 15 (21.4%) | 10 (17.5%) | 21 (27.6%) | - | - | |||||

| Sigmoidectomy | 13 (11.9%) | 2 (5.7%) | 11 (15.7%) | 13 (22.8%) | 13 (17.1%) | - | - | |||||

| Low anterior resection | 46 (42.2%) | 13 (37.1%) | 13 (18.6%) | - | - | 45 (88.2%) | 27 (90%) | |||||

| Ultra-low anterior resection | 4 (3.7%) | 1 (2.9%) | 2 (2.9%) | - | - | 4 (7.8%) | 3 (10%) | |||||

| Abdominoperineal resection | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - | - | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | |||||

| Emergency status | Elective | 109 (100%) | 35 (100%) | 68 (97.1%) | NS | 57 (100%) | 74 (97.4%) | NS | 51 (100%) | 30 (100%) | - | |

| Semi-elective | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.6%) | - | - | |||||

| Laparoscopic approach | Totally laparoscopic | 98 (89.9%) | 24 (68.6%) | 60 (85.7%) | 0.009 | 56 (98.2%) | 71 (93.4%) | NS | 41 (80.4%) | 14 (46.7%) | 0.002 | |

| Laparoscopy assisted | 11 (10.1%) | 11 (31.4%) | 10 (14.3%) | 1 (1.8%) | 5 (6.6%) | 10 (19.6%) | 16 (53.3%) | |||||

| Preoperative optimization | Bowel preparation | 107 (98.2%) | 30 (85.7%) | 54 (77.1%) | < 0.001 | 56 (98.2%) | 56 (73.7%) | < 0.001 | 50 (98%) | 29 (96.7%) | NS | |

| Antibiotic preparation | 105 (96.3%) | 33 (94.3%) | 68 (97.1%) | NS | 54 (94.7%) | 73 (96.1%) | NS | 50 (98%) | 29 (96.7%) | NS | ||

| Tattoo | 36 (33%) | 2 (5.7%) | 13 (18.6%) | 0.002 | 17 (29.8%) | 11 (14.5%) | 0.032 | 19 (37.3%) | 4 (13.3%) | 0.021 | ||

| Extraction site | Pfannenstiel | 52 (47.7%) | 15 (42.9%) | 28 (40%) | NS | 15 (26.3%) | 25 (32.9%) | NS | 37 (72.5) | 18 (60%) | NS | |

| Subumbilical | 12 (11%) | 4 (11.4%) | 3 (4.3%) | 2 (3.5%) | 2 (2.6%) | 9 (17.6%) | 6 (20%) | |||||

| Transumbilical | 45 (41.3%) | 16 (45.7%) | 39 (55.7%) | 40 (70.2%) | 49 (64.5%) | 5 (9.8%) | 6 (20%) | |||||

| Anastomosis | Stapled | 85 (78.7%) | 24 (70.6%) | 50 (71.4%) | NS | 34 (59.6%) | 46 (60.5%) | NS | 50 (100%) | 29 (100%) | NS | |

| Handsewn | 23 (21.3%) | 10 (29.4%) | 20 (28.6%) | 23 (40.4%) | 30 (39.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||||

| Intracorporeal | 57 (52.8%) | 16 (47.1%) | 39 (55.7%) | NS | 18 (31.6%) | 32 (42.1%) | NS | 38 (76%) | 24 (82.8%) | NS | ||

| Extracorporeal | 51 (47.2%) | 18 (52.9%) | 31 (44.3%) | 39 (68.4%) | 44 (57.9%) | 12 (24%) | 5 (17.2%) | |||||

| Protective stoma | 38 (34.9%) | 11 (31.4%) | 17 (24.3%) | NS | 3 (5.3%) | 6 (7.9%) | NS | 34 (66.7%) | 23 (76.7%) | NS | ||

| Operation duration (min) | 180 (50) | 220 (60) | 180 (40) | < 0.001 | 160 (48) | 180 (40) | 0.003 | 200 (50) | 220 (63) | 0.003 | ||

| Open conversion | 13 (11.9%) | 2 (5.7%) | 5 (7.1%) | NS | 4 (7%) | 2 (2.6%) | NS | 8 (15.7%) | 6 (20%) | NS | ||

| Transfusion | 5 (4.6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (4.3%) | NS | 3 (5.3%) | 1 (1.3%) | NS | 1 (2%) | 3 (10%) | NS | ||

| Tumor diameter (cm) | 3 (2.1) | 4 (2.4) | 3 (2) | NS | 3 (1.5) | 3.5 (2) | NS | 4 (2.4) | 3 (3) | NS | ||

| Specimen length (cm) | 16.25 (7.25) | 22.5 (6.5) | 24 (8) | < 0.001 | 20.5 (8) | 23 (8.75) | 0.001 | 14.25 (3.75) | 21 (6) | < 0.001 | ||

| Distal margin (cm) | 4 (3.5) | 7 (2) | 7 (5) | < 0.001 | 4 (2.5) | 7 (3.5) | < 0.001 | 4 (4.25) | 5 (4.5) | NS | ||

| Lymph nodes | 15 (10) | 20 (19) | 21 (12) | 0.016 | 15 (10) | 22 (13) | 0.002 | 15 (10) | 12.5 (15) | NS | ||

| Lymph node ratio | 0 (0) | 0 (0.8) | 0 (8) | NS | 0 (4.5) | 0 (3.8) | NS | 0 (0) | 0 (13.5) | NS | ||

| Histological grade | 1 | 26 (24.5%) | 1 (2.9%) | 13 (19.7%) | 0.013 | 10 (18.9%) | 10 (13.9%) | 0.009 | 16 (31.4%) | 4 (13.3%) | NS | |

| 2 | 60 (56.6%) | 27 (79.5%) | 48 (72.7%) | 31 (58.5%) | 58 (80.6%) | 27 (52.9%) | 19 (63.3%) | |||||

| 3 | 20 (18.9%) | 6 (17.6%) | 5 (7.6%) | 12 (22.6%) | 4 (5.6%) | 8 (15.7%)_ | 7 (23.3%) | |||||

| R status | 0 | 105 (99.1%) | 33 (97.1%) | 66 (100%) | NS | 53 (98.1%) | 71 (100%) | NS | 51 (100%) | 29 (96.7%) | NS | |

| 1 | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.3%) | |||||

| Resection plane | Mesocoli/mesorectal | 91 (85.8%) | 31 (91.2%) | 61 (92.4%) | NS | 43 (79.6%) | 65 (91.5%) | NS | 47 (92.2%) | 28 (93.3%) | NS | |

| Intramesocolic/intramesorectal | 12 (11.3%) | 3 (8.8%) | 4 (6.1%) | 9 (16.7%) | 5 (7%) | 3 (5.9%) | 2 (6.7%) | |||||

| Muscularis propria | 3 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.5%) | 2 (3.7%) | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |||||

| Extramural vascular invasion | 30 (28.3%) | 7 (20.6%) | 17 (25.8%) | NS | 13 (24.5%) | 20 (27.8%) | NS | 16 (31.4%) | 5 (16.7%) | NS | ||

| Perineural invasion | 13 (12.3%) | 4 (11.8%) | 4 (6.1%) | NS | 7 (13.2%) | 6 (8.3%) | NS | 6 (11.8%) | 2 (6.7%) | NS | ||

| Mucous | Focal | 11 (10.4%) | 12 (35.3%) | 6 (9.1%) | 0.006 | 6 (11.3%) | 14 (19.4%) | NS | 4 (7.8%) | 5 (16.7%) | NS | |

| Diffuse | 9 (8.5%) | 3 (8.8%) | 8 (12.1%) | 7 (13.2%) | 8 (11.1%) | 2 (3.9%) | 3 (10%) | |||||

| Complications | Total | 28 (25.7%) | 9 (25.7%) | 12 (17.1%) | NS | 15 (26.3%) | 18 (23.7%) | NS | 12 (23.5%) | 4 (13.3%) | NS | |

| Wound infection | 5 (4.6%) | 2 (5.7%) | 2 (2.9%) | NS | 1 (1.8%) | 4 (5.3%) | NS | 4 (7.8%) | 0 (0%) | NS | ||

| Wound dehiscence | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||||

| Leak | 8 (7.3%) | 4 (11.4%) | 2 (2.9%) | 5 (8.8%) | 5 (6.6%) | 2 (3.9%) | 2 (6.7%) | |||||

| Postoperative ileus | 7 (6.4%) | 1 (2.9%) | 3 (4.3%) | 4 (7%) | 4 (5.3%) | 3 (5.9%) | 0 (0%) | |||||

| Urinary tract infection | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.9%) | 0 (0%) | |||||

| Urinary retention | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |||||

| Bleeding | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (3.3%) | |||||

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||||

| ARDS | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.3%) | |||||

| Other | 3 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 3 (5.3%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||||

| Relaparotomy | 5 (4.6%) | 3 (8.6%) | 3 (4.3%) | NS | 2 (3.5%) | 6 (7.9%) | NS | 2 (3.9%) | 1 (3.3%) | NS | ||

| ICU | 6 (5.5%) | 1 (2.9%) | 1 (1.4%) | NS | 4 (7%) | 1 (1.3%) | NS | 2 (3.9%) | 1 (3.3%) | NS | ||

| Mortality | 4 (3.7%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) | NS | 3 (5.3%) | 1 (1.3%) | NS | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | NS | ||

| Length of hospital stay (d) | 6 (2) | 6 (3) | 6 (2) | NS | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | NS | 6 (2) | 5 (1) | NS | ||

| Follow-up (mo) | 2 (3.25) | 0.65 (0) | 6 (5) | NS | 2 (3.3) | 6.8 (4.4) | NS | 2 (3) | 0.27 (0) | 0.032 | ||

BMI: Body mass index; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; ARDS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome; ICU: Intensive care unit.

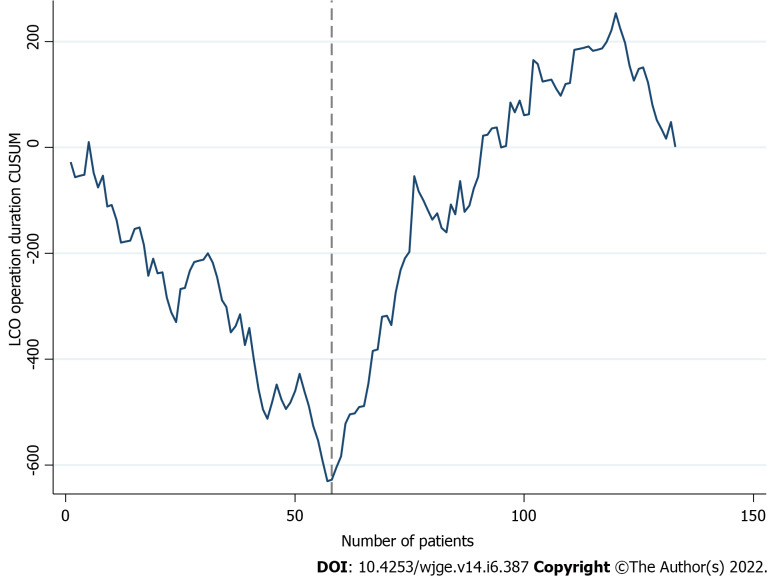

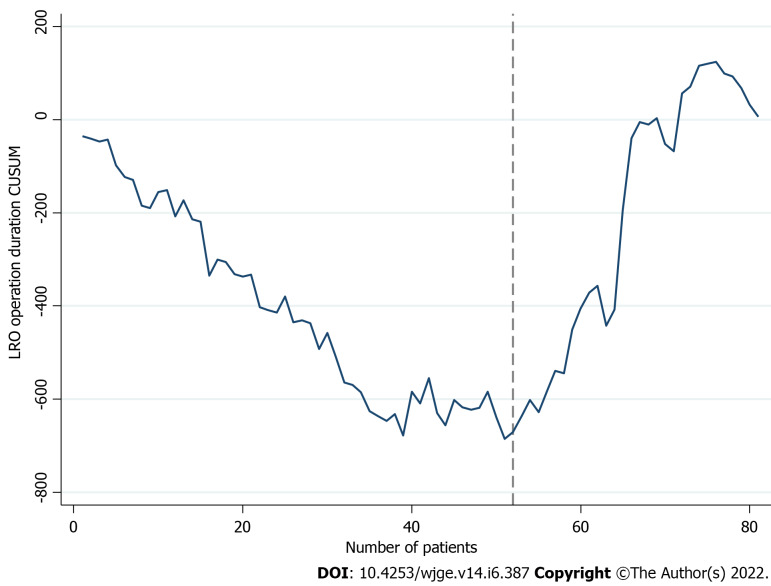

Figures 2 and 3 display the learning curve plots of LCO and LRO, correspondingly. Both LC patterns were comparable. First successive cases resulted in a gradual decrease and the reach of a minimum, followed by a consequent increment of the LC line. We confirmed that the 58th (CL: 99%) and 52nd (CL: 100%) cases were the corresponding turning points of colon and rectal resections. Hence, we identified two phases of the LCO and LRO learning curve (LCO phase I: 1 to 57 operations; LCO phase II: 58 to 133 operations; LRO phase I: 1 to 51 operations; LRO phase II: 52 to 81 operations).

Figure 2.

Cumulative sum analysis of operation duration in laparoscopic colon operations. CUSUM: Cumulative sum; LCO: Laparoscopic colon operations.

Figure 3.

Cumulative sum analysis of operation duration in laparoscopic rectal operations. CUSUM: Cumulative sum; LRO: Laparoscopic rectal operations.

Table 2 summarizes the eligible patient data and the study outcomes between the various LC phases. LCRO phase III displayed a significant improvement in the specimen length (P < 0.001), the resection distal margin (P < 0.001), and the lymph node yield (P = 0.016).

Subgroup analyses of the LC phases showed that surgical experience was correlated with the specimen length in both LCO and LRO (P = 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively). However, dexterity in laparoscopic surgery increased the distal resection margin (P < 0.001) and number of excised lymph nodes (P = 0.002) only in LCO.

Postoperative complication analysis (Supplementary Figures) in LCRO (P = 0.48), LCO (P = 0.419), and LRO (P = 0.521) did not identify an LC pattern. Similarly, open conversion was not associated with a learning curve pattern in any of the study subgroups (P = 0.3, P = 0.8, and P = 0.19, correspondingly).

Finally, the diagrams of the pathology endpoints are provided in Supplementary Figures. The 64th case (CL: 100%) was estimated as the turning point of the specimen length in colon resections. A plateau was reached after the 99th case (CL: 94%). The respective turning point of the LRO was the 47th case. There were no significant CPA turning points in the resected lymph node yield.

DISCUSSION

LC is defined as the schematic depiction of the fluctuation of an efficiency outcome, plotted over a successive number of repetitions[27,29]. Among the various statistical methodologies that have been employed for the LC evaluation are the group splitting, moving average, and CUSUM analysis[3,17,32,33]. Following an introductory learning phase, the trainee is gradually performing operations of higher complexity and difficulty[34,35]. Finally, once the iteration of the process does not affect the measured variable, mastery is achieved[16,17,32]. As a result, estimation of the LC turning points is of paramount importance in trend analysis[26].

The inherent divergence of the learning efficiency, alongside the discrepancy in the estimated LC endpoints, resulted in a significant heterogeneity in the published LC outcomes[4,36]. To be more specific, recent studies in laparoscopic colorectal surgery suggested that LC turning points fluctuate between 10[32] and 200 cases[37].

Operation duration has been frequently introduced as the LCRO LC estimated variable[27,29,32]. Nonetheless, surgical expertise assessment, based solely upon operation duration, may result in biased conclusions[27,29]. This is due to the fact that the overlapping surgical skills and the efficient collaboration between the assisting theater personnel can also impact the duration of a procedure[27,38,39]. Initial studies suggested that 23 operations may suffice for the standardization of operative time[9,24]; however, this was not validated in subsequent trials, where a 96-case margin was reported[23]. Our results estimated the first LC cut-off point at the 110th case, which is in parallel with the previous evidence.

Interestingly, we identified lower LC turning points during the individual assessment of both colon and rectal operations (LCO: 58 cases; LRO: 52 cases). This discrepancy may be the result of the combination of the two study subgroups. In particular, the estimated LC of a specific operation subtype is usually shorter, since it incorporates fewer surgical steps. Despite the fact that previous surgical competence, in either LCO or LRO, may accelerate the transposition of skills to the other, completion of LCRO LC prerequisites the attainment of mastery in both operations. Therefore, LCRO LC is equal to the summation of the two subgroup CUSUM plots.

The narrow working space, the lack of three-dimensional vision, and the fixed port positions further enhance the LCRO surgical complexity and the risk of critical intraoperative events[29]. Consequently, the learning curve status mat have a direct impact on perioperative morbidity[7,17,22,23]. Previous reports estimated that a plateau in LCRO complication rate is achieved after 140 to 200 operations[23,37]. However, we were not able to validate a LC pattern in perioperative morbidity. Similarly, MacKenzie et al[4] suggested the absence of fluctuation in the perioperative complications rate during the LC period. Nonetheless, these results may be due to an inadequate sample size, since larger cohorts confirmed the presence of an LC pattern in perioperative morbidity[7,17,22,23,37].

Open conversion is considered in the case of a critical event that is not amendable by the ongoing approach[17,19,32]. Typical examples include an intraoperative complication or the compromise of the oncological principles[15,19,24,25]. Although not widely accepted, conversion turning point is estimated at 61 successive operations[18,26,40]. A structured training program, though, may further reduce the above-mentioned LC margin[18,26,40]. Even though our results were in accordance with previously published reports[23], we did not confirm the presence of an LC trend in the open conversion rate.

Specimen-related endpoints are of paramount importance when evaluating the oncological efficacy of an operation[6,14,36]; lymph node yield is the most prominent among them[6,14,36]. However, this can be misleading since lymph node harvest can be affected by anthropometric and disease-related characteristics[41]. Despite these, we confirmed the presence of a significant LC trend in the number of the resected lymph nodes. Additionally, CPA validated the increase of the specimen length after the 64th LCO and 47th LRO case, respectively. We did not introduce positive resection margin and non-CME/TME dissection plane as an LC outcome, due to the scarcity of these events. Moreover, in case of CME/ TME violation, an open conversion was performed to secure adherence to oncological principles.

A swift completion of the learning curve is needed, in order to capitalize on the LCRO advantages[29]. Modular training enables the partitioning of the procedure in successive steps, each with its own optimization requirements[18]. The introduction of advanced LCRO courses, mentor guidance, and large operational volume exposure result in a considerable downgrade of the LC cut-off points[18,27]. These methods have been successfully enrolled in multiple national structured training programs, with promising results[17,26]. Nonetheless, surgeons in healthcare systems that have not included LCRO in their official guidelines, do not have access to similar training modules[22]. Therefore, the implementation of LCRO in such settings is based on the individual training efforts of the involved surgeons, with questionable, though, results.

In this study, we analyzed the pooled learning curve of two senior colorectal surgeons. LCRO training was not structured and included course attendance and proctor guidance. Despite this, previous experience in laparoscopic surgery and open colorectal resections could have impacted the pooled LCRO LC turning points. Therefore, our results may not reflect the typical LC pattern of an average surgical trainee.

Several limitations should be acknowledged, prior to the appraisal of our findings. First, despite the statistical significance of several LC turning points, our study incorporated a relatively small sample size. This prohibited further explanatory analyses, including risk-adjustment of the learning curves. Moreover, the innate discrepancy in terms of patient and surgical characteristics, degraded the significance of our results. Furthermore, another major source of bias could be the retrospective design of our study. Finally, the fact that only two consultants were included in this study, prohibited the safe extrapolation of these findings to a wider pool of colorectal surgeons and surgical trainees.

CONCLUSION

Overall, our study reported that the LCRO operation duration learning curve consists of three distinct phases. CPA estimated that the 110th case is the cut-off point between the first two phases. Stabilization of operative time is achieved after the 145th case. LCO and LRO subgroup analysis estimated the 58th and 52nd case as the respective turning points. In contrast to the open conversion and morbidity outcomes, a learning curve pattern was confirmed in pathology endpoints. The learning curves in our settings validate the comparability of the results, despite the absence of National or Surgical Society driven training programs. However, the initiation of a formal LCRO training policy is necessary for the safe and efficient implementation of these procedures.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

The introduction of structured training programs results in an enhanced learning process in laparoscopic colorectal surgery.

Research motivation

National training programs are not widely available, thus constraining the efficient adaptation of minimal invasive techniques in colorectal surgery.

Research objectives

To analyze the learning curve patterns in laparoscopic colorectal operations under a non-structured training setting.

Research methods

A retrospective analysis of a prospectively collected database was performed. Cumulative sum analysis and change point analysis were introduced for the evaluation of learning curve patterns.

Research results

In terms of operation duration, three learning curve phases were identified. A learning curve pattern was also confirmed in pathology endpoints, but not in the open conversion and complications outcomes.

Research conclusions

Laparoscopic colorectal operations under a non-structured training setting result in similar learning patterns with the respective structured training curves.

Research perspectives

The introduction of formal training programs in laparoscopic colorectal surgery is necessary for the safer and wider adoption of these techniques.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This retrospective chart review study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. We consulted extensively with the IRB of University Hospital of Larissa who determined that our study did not need ethical approval since all procedures being performed were part of the routine care.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict-of-interest statement: We have no financial relationships to disclose.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement—checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement—checklist of items.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: January 24, 2022

First decision: April 17, 2022

Article in press: May 17, 2022

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Greece

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Apiratwarakul K, Thailand; Farouk S, Egypt A-Editor: Lin FY, China S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang LL

Contributor Information

Konstantinos Perivoliotis, Department of Surgery, University Hospital of Larissa, Larissa 41110, Greece.

Ioannis Baloyiannis, Department of Surgery, University Hospital of Larissa, Larissa 41110, Greece. balioan@hotmail.com.

Ioannis Mamaloudis, Department of Surgery, University Hospital of Larissa, Larissa 41110, Greece.

Georgios Volakakis, Department of Surgery, University Hospital of Larissa, Larissa 41110, Greece.

Alex Valaroutsos, Department of Surgery, University Hospital of Larissa, Larissa 41110, Greece.

George Tzovaras, Department of Surgery, University Hospital of Larissa, Larissa 41110, Greece.

Data sharing statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Yamanashi T, Nakamura T, Sato T, Naito M, Miura H, Tsutsui A, Shimazu M, Watanabe M. Laparoscopic surgery for locally advanced T4 colon cancer: the long-term outcomes and prognostic factors. Surg Today. 2018;48:534–544. doi: 10.1007/s00595-017-1621-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamaguchi S, Tashiro J, Araki R, Okuda J, Hanai T, Otsuka K, Saito S, Watanabe M, Sugihara K. Laparoscopic versus open resection for transverse and descending colon cancer: Short-term and long-term outcomes of a multicenter retrospective study of 1830 patients. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2017;10:268–275. doi: 10.1111/ases.12373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Son GM, Kim JG, Lee JC, Suh YJ, Cho HM, Lee YS, Lee IK, Chun CS. Multidimensional analysis of the learning curve for laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech . 2010;20:609–617. doi: 10.1089/lap.2010.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackenzie H, Miskovic D, Ni M, Parvaiz A, Acheson AG, Jenkins JT, Griffith J, Coleman MG, Hanna GB. Clinical and educational proficiency gain of supervised laparoscopic colorectal surgical trainees. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2704–2711. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2806-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao PP, Rao PP, Bhagwat S. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery - current status and controversies. J Minim Access Surg. 2011;7:6–16. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.72360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim CW, Lee KY, Lee SC, Lee SH, Lee YS, Lim SW, Kim JG. Learning curve for single-port laparoscopic colon cancer resection: a multicenter observational study. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:1828–1835. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Georgiou PA, Bhangu A, Brown G, Rasheed S, Nicholls RJ, Tekkis PP. Learning curve for the management of recurrent and locally advanced primary rectal cancer: a single team's experience. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:57–65. doi: 10.1111/codi.12772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melich G, Jeong DH, Hur H, Baik SH, Faria J, Kim NK, Min BS. Laparoscopic right hemicolectomy with complete mesocolic excision provides acceptable perioperative outcomes but is lengthy--analysis of learning curves for a novice minimally invasive surgeon. Can J Surg. 2014;57:331–336. doi: 10.1503/cjs.002114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai KY, Kiu KT, Huang MT, Wu CH, Chang TC. The learning curve for laparoscopic colectomy in colorectal cancer at a new regional hospital. Asian J Surg. 2016;39:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rönnow C-F, Uedo N, Toth E, Thorlacius H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of 301 Large colorectal neoplasias: outcome and learning curve from a specialized center in Europe. Endosc Int Open . 2018;6:E1340–8. doi: 10.1055/a-0733-3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lohsiriwat V. Learning curve of enhanced recovery after surgery program in open colorectal surgery. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;11:169–178. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v11.i3.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Symer MM, Sedrakyan A, Yeo HL. Case Sequence Analysis of the Robotic Colorectal Resection Learning Curve. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:1071–1078. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gehrman J, Angenete E, Björholt I, Lesén E, Haglind E. Cost-effectiveness analysis of laparoscopic and open surgery in routine Swedish care for colorectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:4403–4412. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-07214-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prakash K, Kamalesh NP, Pramil K, Vipin IS, Sylesh A, Jacob M. Does case selection and outcome following laparoscopic colorectal resection change after initial learning curve? J Minim Access Surg. 2013;9:99–103. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.115366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naguib N, Masoud AG. Laparoscopic colorectal surgery for diverticular disease is not suitable for the early part of the learning curve. A retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg . 2013;11:1092–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pendlimari R, Holubar SD, Dozois EJ, Larson DW, Pemberton JH, Cima RR. Technical proficiency in hand-assisted laparoscopic colon and rectal surgery: determining how many cases are required to achieve mastery. Arch Surg. 2012;147:317–322. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tekkis PP, Senagore AJ, Delaney CP, Fazio VW. Evaluation of the learning curve in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: comparison of right-sided and left-sided resections. Ann Surg. 2005;242:83–91. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000167857.14690.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkins JT, Currie A, Sala S, Kennedy RH. A multi-modal approach to training in laparoscopic colorectal surgery accelerates proficiency gain. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:3007–3013. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4591-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rencuzogullari A, Stocchi L, Costedio M, Gorgun E, Kessler H, Remzi FH. Characteristics of learning curve in minimally invasive ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in a single institution. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:1083–1092. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang MR, Seo GJ, Yoo SB, Park JW, Choi HS, Oh JH, Jeong SY. Learning curve of assistants in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: overcoming mirror imaging. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2575–2580. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito M, Sugito M, Kobayashi A, Nishizawa Y, Tsunoda Y, Saito N. Influence of learning curve on short-term results after laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:403–408. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9912-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dinçler S, Koller MT, Steurer J, Bachmann LM, Christen D, Buchmann P. Multidimensional analysis of learning curves in laparoscopic sigmoid resection: eight-year results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1371–8; discussion 1378. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6752-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miskovic D, Ni M, Wyles SM, Tekkis P, Hanna GB. Learning curve and case selection in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: systematic review and international multicenter analysis of 4852 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:1300–1310. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31826ab4dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen G, Liu Z, Han P, Li JW, Cui BB. The learning curve for the laparoscopic approach for colorectal cancer: a single institution's experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23:17–21. doi: 10.1089/lap.2011.0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haas EM, Nieto J, Ragupathi M, Aminian A, Patel CB. Critical appraisal of learning curve for single incision laparoscopic right colectomy. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4499–4503. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3096-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miskovic D, Wyles SM, Carter F, Coleman MG, Hanna GB. Development, validation and implementation of a monitoring tool for training in laparoscopic colorectal surgery in the English National Training Program. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1136–1142. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1329-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toledano Trincado M, Sánchez Gonzalez J, Blanco Antona F, Martín Esteban ML, Colao García L, Cuevas Gonzalez J, Mayo Iscar A, Blanco Alvarez JI, Martín del Olmo JC. How to reduce the laparoscopic colorectal learning curve. JSLS. 2014;18 doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ni M, Mackenzie H, Widdison A, Jenkins JT, Mansfield S, Dixon T, Slade D, Coleman MG, Hanna GB. What errors make a laparoscopic cancer surgery unsafe? Surg Endosc. 2016;30:1020–1027. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kye BH, Kim JG, Cho HM, Kim HJ, Suh YJ, Chun CS. Learning curves in laparoscopic right-sided colon cancer surgery: a comparison of first-generation colorectal surgeon to advance laparoscopically trained surgeon. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21:789–796. doi: 10.1089/lap.2011.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leong S, Cahill RA, Mehigan BJ, Stephens RB. Considerations on the learning curve for laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a view from the bottom. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1109–1115. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi DH, Jeong WK, Lim SW, Chung TS, Park JI, Lim SB, Choi HS, Nam BH, Chang HJ, Jeong SY. Learning curves for laparoscopic sigmoidectomy used to manage curable sigmoid colon cancer: single-institute, three-surgeon experience. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:622–628. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9753-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li JC, Hon SS, Ng SS, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Leung KL. The learning curve for laparoscopic colectomy: experience of a surgical fellow in an university colorectal unit. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1603–1608. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0497-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stam M, Draaisma WA, Pasker P, Consten E, Broeders I. Sigmoid resection for diverticulitis is more difficult than for malignancies. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:891–896. doi: 10.1007/s00384-017-2756-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shanker BA, Soliman M, Williamson P, Ferrara A. Laparoscopic Colorectal Training Gap in Colorectal and Surgical Residents. JSLS. 2016;20 doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2016.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li JCM, Lo AWI, Hon SSF, Ng SSM, Lee JFY, Leung KL. Institution learning curve of laparoscopic colectomy-a multi-dimensional analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:527–533. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park IJ, Choi GS, Lim KH, Kang BM, Jun SH. Multidimensional analysis of the learning curve for laparoscopic colorectal surgery: lessons from 1,000 cases of laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:839–846. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang XM, Wang Z, Liang JW, Zhou ZX. Seniors have a better learning curve for laparoscopic colorectal cancer resection. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:5395–5399. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.13.5395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bennett CL, Stryker SJ, Ferreira MR, Adams J, Beart RW Jr. The learning curve for laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Preliminary results from a prospective analysis of 1194 laparoscopic-assisted colectomies. Arch Surg. 1997;132:41–4; discussion 45. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430250043009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kiran RP, El-Gazzaz GH, Vogel JD, Remzi FH. Laparoscopic approach significantly reduces surgical site infections after colorectal surgery: data from national surgical quality improvement program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Destri G, Di Carlo I, Scilletta R, Scilletta B, Puleo S. Colorectal cancer and lymph nodes: the obsession with the number 12. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1951–1960. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i8.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.