Abstract

National strategies are needed to continue to promote the broader benefits of participating in sport and organised physical activity to reduce physical inactivity and related disease burden. This paper employs the RE-AIM framework to evaluate the impact of the federally funded $150 million Move it AUS program in engaging inactive people in sport and physical activity through the Participation (all ages) and Better Ageing (over 65 years) funding streams. A pragmatic, mixed-methods evaluation was conducted to understand the impact of the grant on both the participants, and the funded organisations. This included participant surveys, case studies, and qualitative interviews with funded program leaders. A total of 75% of participants in the Participation stream, and 65% in the Better Ageing stream, were classified as inactive. The largest changes in overall physical activity behaviour were seen among socioeconomically disadvantaged participants and culturally and linguistically diverse participants. Seven key insights were gained from the qualitative interviews: Clarity of who, Partnerships, Communication, Program delivery, Environmental impacts, Governance, and that Physical inactivity must be a priority. The Move It AUS program successfully engaged physically inactive participants. Additional work is needed to better engage inactive people that identify as culturally and linguistically diverse, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and those that live in disadvantaged communities in sport and physical activities. Tangible actions from the seven key insights should be adopted into workforce capability planning for the sport sector to effectively engage physically inactive communities.

Keywords: physical activity, sporting program, physical inactivity, organised physical activity, health-enhancing physical activity promotion

1. Introduction

Physical inactivity is a major public health and economic concern to global communities [1]. Despite the benefits of physical activity (PA) on population health outcomes (physical, mental, and social), improved community connectedness, and contribution to economic growth [2,3,4], limited evidence exists on population-level strategies to increase PA, particularly in communities most likely to be inactive [5]. In the 2018/19 Federal Government Budget, Sport Australia committed more than $150m to ‘Drive national sports participation and PA initiatives to get more Australian’s moving more often’ through the launch of the Australian roadmap ‘Sport 2030’, and investment through the Move It AUS grant program [6]. Support for this national plan is evident, with funding in sport identified as one of the eight best investments to tackle the growing inactivity crisis, and sport as a tool to enable active communities has been recognised and endorsed in the Global Action Plan on Physical Activity (GAPPA) [4,7]. More recently, the World Health Organization released the Fair Play advocacy brief, which signposted the necessity for PA to be a priority for all involved stakeholders to reduce the equity gap in physical inactivity [2]. Improved and equitable access to appropriate PA and sport activities must become a priority across society to address growing health inequities, made particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic [2,8].

Effectively evaluating the impact of population-level physical activity programs is complex and challenging. A lack of integrated evaluations and weak intervention designs are common, and few evaluations are transparent in their protocol reporting and many fail to assess program reach, omitting key process information required to make a judgement of value and translation [9,10]. The aims of this paper are to present the process and outcomes of a national government-funded national sport grant program ‘Move it AUS’ for physically inactive Australians using the RE-AIM framework. The paper will report the outcomes of the grant program’s Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance of the different components of the program in the real-world contexts of the program’s delivery [11]. This evaluation of the Move It AUS funded program will contribute to the evidence base on what works and what does not for reducing physical inactivity within communities and provide key insights on enhancing capability within the sport and recreation sectors to suggest appropriate and inclusive opportunities to recruit new target groups to participate.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Funding Overview

In 2019, Sport Australia announced a $56 million investment into two funding streams, the Participation (all ages) and Better Ageing (BA, over 65 years) streams. Funding focused on engaging inactive target groups in organised sport and PA, including people living with a disability, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, women and girls, disadvantaged communities, individuals with (or at risk of) long-term conditions, and culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) and older people.

2.2. Evaluation Design

The ‘Theory of Change’ guided the evaluation methods to inform how the program impacted both the capacity of the sport and PA sector (funded organisations) [12]. A logic model was created for both Participation and BA streams to ensure data collected could appropriately explain whether the program achieved these outcomes (Table 1). The use of realistic evaluation methods using the RE-AIM framework in this study aimed to understand the reasons for a certain outcome and to provide practice-relevant evidence [13].

Table 1.

Sport Australia Move It AUS Participation and Better Ageing (BA) Logic Model.

| Inputs | Activities | Outputs | Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short (June 2019–June 2021) |

Medium (July 2021–June 2023) |

Long-Term (July 2023–) |

|||

|

|

Sport and Physical Activity Sector | |||

|

|

|

|

||

| Participants | |||||

|

|

|

|

||

A quasi-experimental mixed method design used a pre-post survey, alongside qualitative data collection with funded program operational leaders. Participant characteristics and program designs for the two streams (Participation and BA) differ and have been analysed and reported separately.

2.3. Ethics

The University of Sydney ethics committee granted ethics approval for this evaluation (2019/533 and 2020/250). Where required, written informed consent was attained prior to data collection.

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Pre-Post Survey (Participant Outcomes)

Surveys were expected to be distributed by the funded organisations to all registered participants before and after their participation in the funded program, or at 6 months post initial registration. Socio-demographic data were collected from participants including postcode, which was used to classify both socioeconomic status using the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) [14], and remoteness using the Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+) [15]. This survey data were used to inform on the reach, effectiveness, and maintenance aspects of programs in achieving the aims of the funding.

The primary outcome of the survey data was meeting PA guidelines status, assessed using the validated single item measures for children 5–17 [16] and adults 18+ years old [17]. The definition for physically inactive were adults who were not completing 30 mins of PA on 5 or more days per week, and for children 60 mins of PA on 7 days per week [4]. Secondary outcomes, including organised sport participation, were aligned where possible with existing validated or accepted measures [18].

2.4.2. Qualitative Interviews (Organisational Outcomes)

All Move It AUS grant funded organisations were invited to participate in a 30–45 min qualitative interview (Appendix A). A purposive convenience sample of organisations was recruited, and a nominated leader from each organisation participated in the interview at the conclusion of the program delivery. Interview questions related to the RE-AIM framework and provided perspectives on the process and outcomes of program delivery (Appendix A). The interviews were conducted and recorded online using Zoom (ZoomVideo Communications Inc., San Jose, CA, USA, 2016).

2.5. Data Analysis

Participants’ demographic characteristics were calculated using descriptive statistics, including frequencies and proportions. Logistic regression models were used to determine whether the pre/post timepoint was associated with meeting physical activity guidelines and sport participation (at least twice per week). Model 1 is unadjusted and model 2 adjusts for age, sex, language, remoteness, and socioeconomic status. All analyses were performed in SAS Enterprise Guide 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

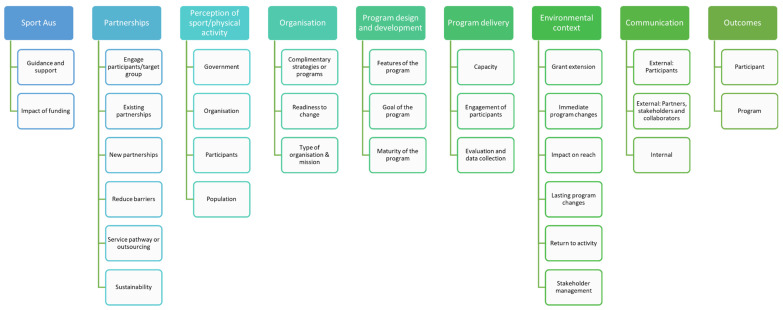

All audio recordings of the qualitative interviews were transcribed verbatim for analysis by a professional transcription company (Way With Words). Framework Analysis was deemed an appropriate approach to analyse qualitative data due to the systematic nature of the semi-structured interviews [19]. Interview transcriptions were analysed using the Framework Analysis approach in NVivo software (NVivo 12 Plus). Once familiarised with the transcripts, the research team conducted an iterative process that identified codes and sub-codes within the interviews to form a thematic scheme of the data (Figure 1). The RE-AIM framework was applied to the coded themes to understand the areas in which the grant programs were successful, or could be improved, in achieving the aims of the funding.

Figure 1.

A thematic scheme of the codes and sub-codes identified within the qualitative interview data.

3. Results

In total, 88 diverse organisations were funded to deliver activities from July 2019 to July 2020 (Participation stream, n = 62), or July 2019 to July 2020 (BA stream, n = 26). Due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, 32 of the funded programs were provided an extension beyond the planned completion date in June 2020. The 62 organisations in the Participation stream engaged 495,528 people, with 43,638 participants participating across 26 BA funded programs. A small proportion of participants responded to the pre/post survey, with 3483 (0.8%) and 6687 (15.3%) of Participation and BA stream participants responding to the survey, respectively. The results for each funding stream are presented separately herein, using the RE-AIM framework.

3.1. Reach

Funded programs successfully reached target groups (Table 2) and inactive populations. A total of 75% of participants in Participation programs and 77% of participants in BA programs did not meet PA guidelines at baseline. However, there was low representation in some key target groups within the data set of inactive participants, including Aboriginal and or Torres Strait Islanders (5% Participation, <1% Better Ageing), CALD participants (11% Participation, 11% BA), and those living in outer regional/remote communities (7.6% Participation, 12% BA).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of participants in the Participation and Better Ageing stream across timepoints.

| Participation Stream | Better Ageing Stream | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | All | Pre | Post | All | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| All persons | 1410 | 100 | 1328 | 100 | 3837 | 100 | 3351 | 100 | 2649 | 100 | 6687 | 100 |

| Age category | ||||||||||||

| 0–17 | 536 | 43.4 | 730 | 58.2 | 1604 | 45.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 18–34 | 233 | 18.9 | 141 | 11.2 | 526 | 14.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 35–44 | 230 | 18.6 | 190 | 15.2 | 795 | 22.4 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 45–54 | 143 | 11.6 | 138 | 11.0 | 451 | 12.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 55–64 | 76 | 6.2 | 46 | 3.7 | 143 | 4.0 | 63 | 20.0 | 468 | 27.7 | 594 | 25.2 |

| 65+ | 17 | 1.4 | 9 | 0.7 | 34 | 1.0 | 252 | 80.0 | 1220 | 72.3 | 1762 | 74.8 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 543 | 38.8 | 592 | 44.8 | 1347 | 35.5 | 1001 | 32.5 | 382 | 21.7 | 1433 | 27.5 |

| Female | 824 | 58.8 | 705 | 53.3 | 2383 | 62.8 | 2079 | 67.5 | 1382 | 78.3 | 3771 | 72.5 |

| Prefer not to say | 34 | 2.4 | 25 | 1.9 | 64 | 1.7 | ||||||

| Indigenous | ||||||||||||

| Yes, Aboriginal | 81 | 5.9 | 64 | 4.8 | 179 | 4.8 | 57 | 1.8 | 6 | 0.3 | 63 | 1.2 |

| and/or Torres Strait | ||||||||||||

| Islander | ||||||||||||

| No | 1273 | 92.2 | 1230 | 93.2 | 3492 | 93.4 | 3104 | 98.2 | 1821 | 99.7 | 5315 | 98.8 |

| Prefer not to say | 26 | 1.9 | 26 | 2.0 | 66 | 1.8 | ||||||

| Primary language | ||||||||||||

| English | 1229 | 87.7 | 1121 | 85.2 | 3337 | 88.9 | 3086 | 97.0 | 1610 | 72.8 | 5046 | 87.3 |

| Other | 173 | 12.3 | 194 | 14.8 | 417 | 11.1 | 94 | 3.0 | 601 | 27.2 | 736 | 12.7 |

| Employment | ||||||||||||

| Employed | 275 | 28.7 | 310 | 30.6 | 1177 | 43.1 | 1085 | 35.0 | 434 | 16.8 | 1563 | 25.9 |

| Unemployed | 88 | 9.2 | 62 | 6.1 | 172 | 6.3 | 119 | 3.8 | 802 | 31.1 | 931 | 15.4 |

| Student | 359 | 37.5 | 529 | 52.2 | 943 | 34.5 | 11 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.1 | 13 | 0.2 |

| Pension/welfare | 186 | 19.4 | 85 | 8.4 | 291 | 10.7 | 328 | 10.6 | 280 | 10.9 | 664 | 11.0 |

| Retired | 24 | 2.5 | 4 | 0.4 | 36 | 1.3 | 1446 | 46.6 | 997 | 38.7 | 2689 | 44.5 |

| Other | 26 | 2.7 | 24 | 2.4 | 113 | 4.1 | 113 | 3.6 | 64 | 2.5 | 183 | 3.0 |

| Location | ||||||||||||

| Major Cities | 753 | 58.2 | 802 | 69.4 | 2314 | 65.9 | 1363 | 44.4 | 1720 | 81.1 | 3357 | 60.5 |

| Inner Regional | 392 | 30.3 | 280 | 24.2 | 908 | 25.9 | 1071 | 34.9 | 282 | 13.3 | 1404 | 25.3 |

| Outer Regional and remote | 149 | 11.5 | 73 | 6.3 | 290 | 8.3 | 637 | 20.7 | 118 | 5.6 | 788 | 14.2 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||||||||

| 1st | 338 | 26.2 | 371 | 32.2 | 813 | 23.2 | 642 | 20.9 | 298 | 14.0 | 987 | 17.8 |

| 2nd | 222 | 17.2 | 187 | 16.2 | 655 | 18.7 | 920 | 29.9 | 459 | 21.6 | 1461 | 26.3 |

| 3rd | 395 | 30.6 | 276 | 24.0 | 974 | 27.8 | 664 | 21.6 | 623 | 29.4 | 1366 | 24.6 |

| 4th | 337 | 26.1 | 317 | 27.5 | 1061 | 30.3 | 847 | 27.6 | 741 | 34.9 | 1740 | 31.3 |

| Health condition | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 488 | 36.2 | 320 | 25.3 | 810 | 31.0 | 1451 | 50.6 | 1107 | 44.5 | 2564 | 47.8 |

| No | 859 | 63.8 | 943 | 74.7 | 1807 | 69.0 | 1416 | 49.4 | 1381 | 55.5 | 2797 | 52.2 |

Note: “All” column includes those who could not be classified as pre or post.

3.2. Effectiveness

43% of participants in the Participation stream reported increases in PA behaviours. Participants were 19% (non-significant) more likely to meet guidelines at follow-up, compared to baseline (OR:1.19, 95% CI 0.93, 1.53) (Table 3). Weekly minutes of PA increased in the Participation stream with an increase from 447.5 min per week of organised sport and PA, to 534.7 mins per week.

Table 3.

Odds of meeting physical activity guidelines across timepoints in the Participation and Better ageing funding stream.

| Participation | Better Ageing | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Proportions Meeting Physical Activity Guidelines | Unadjusted Odds Ratio for Meeting Physical Activity Guidelines | Adjusted Odds Ratio for Meeting Physical Activity Guidelines | Unadjusted Proportions Meeting Physical Activity Guidelines | Unadjusted Odds Ratio for Meeting Physical Activity Guidelines | Adjusted Odds Ratio for Meeting Physical Activity Guidelines | |||

| Pre (%) | Post (%) | OR (95% CIs) | OR (95% CIs) | Pre (%) | Post (%) | OR (95% CIs) | OR (95% CIs) | |

| All persons | 25.0 | 27.7 | 1.15 (0.95, 1.39) | 1.19 (0.93, 1.53) | 35.1 | 21.0 | 0.49 (0.43, 0.57) | 0.65 (0.55, 0.76) |

| Age category | ||||||||

| 0–17 | 13.3 | 13.6 | 1.03 (0.69, 1.54) | 1.21 (0.65, 2.22) | ||||

| 18–34 | 30.5 | 40.4 | 1.55 (1.00, 2.40) | 1.72 (0.95, 3.11) | ||||

| 35–44 | 40.9 | 40.0 | 0.96 (0.65, 1.43) | 0.93 (0.6, 1.43) | ||||

| 45–54 | 32.9 | 48.6 | 1.93 (1.19, 3.12) | 1.81 (1.05, 3.12) | ||||

| 55–64 | 35.5 | 34.8 | 0.97 (0.45, 2.08) | 1.45 (0.5, 4.23) | ||||

| 65+ | 17.7 | 66.7 | 9.33 (1.45, 60.21) | |||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 21.8 | 24.3 | 1.15 (0.85, 1.56) | 1.24 (0.84, 1.83) | 39.2 | 20.4 | 0.40 (0.30, 0.53) | 0.60 (0.44, 0.82) |

| Female | 27.6 | 31.5 | 1.21 (0.95, 1.54) | 1.32 (0.95, 1.83) | 33.1 | 21.2 | 0.54 (0.46, 0.64) | 0.65 (0.54, 0.79) |

| Indigenous | ||||||||

| Yes, Aboriginal | 11.1 | 41.5 | 5.67 (1.98, 16.22) | 40.77 (3.75, 443.83) | 28.1 | 16.7 | 0.51 (0.06, 4.73) | 2.4 (0.05, 114.79) |

| and/or Torres | ||||||||

| Strait Islander | ||||||||

| No | 26.7 | 27.5 | 1.04 (0.86, 1.26) | 1.08 (0.84, 1.39) | 34.9 | 21.5 | 0.51 (0.45, 0.58) | 0.65 (0.55, 0.76) |

| Primary language | ||||||||

| English | 25.8 | 29.9 | 1.23 (1.00, 1.5) | 1.29 (1, 1.67) | 35.1 | 33.7 | 0.94 (0.83, 1.07) | 0.71 (0.60, 0.84) |

| Other | 20.4 | 16.7 | 0.78 (0.44, 1.38) | 0.94 (0.42, 2.10) | 26.9 | 7.8 | 0.23 (0.13, 0.40) | 0.18 (0.10, 0.34) |

| Employment | ||||||||

| Employed | 41.4 | 39.9 | 0.94 (0.67, 1.31) | 1.07 (0.74, 1.55) | 34.1 | 35.2 | 1.05 (0.81, 1.36) | 0.76 (0.53, 1.08) |

| Unemployed | 26.4 | 17.0 | 0.57 (0.25, 1.3) | 0.39 (0.12, 1.22) | 40.2 | 13.0 | 0.22 (0.15, 0.34) | 0.39 (0.23, 0.65) |

| Student | 10.7 | 10.8 | 1.02 (0.63, 1.63) | 1.26 (0.71, 2.21) | 36.4 | 50.0 | 1.75 (0.08, 36.29) | |

| Pension/welfare | 15.1 | 38.8 | 3.58 (1.98, 6.48) | 3.29 (1.75, 6.2) | 27.3 | 34.6 | 1.41 (1.00, 2.00) | 0.93 (0.51, 1.71) |

| Retired | 41.7 | 50.0 | 1.4 (0.17, 11.68) | 36.3 | 36.7 | 1.01 (0.86, 1.2) | 0.80 (0.63, 1.02) | |

| Other | 46.2 | 52.2 | 1.27 (0.41, 3.92) | 38.6 | 28.6 | 0.64 (0.21, 1.89) | 0.25 (0.01, 6.86) | |

| Location | ||||||||

| Major Cities | 28.3 | 28.0 | 0.99 (0.77, 1.27) | 0.8 (0.56, 1.13) | 35.7 | 23.8 | 0.56 (0.48, 0.66) | 0.58 (0.48, 0.7) |

| Inner Regional | 23.1 | 35.4 | 1.83 (1.28, 2.62) | 2.24 (1.46, 3.43) | 35.3 | 35.2 | 1.00 (0.76, 1.31) | 0.66 (0.42, 1.03) |

| Outer Regional | 31.5 | 30.4 | 0.95 (0.51, 1.78) | 0.92 (0.46, 1.84) | 33.7 | 47.0 | 1.75 (1.17, 2.61) | 1.56 (0.94, 2.59) |

| and remote | ||||||||

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||||

| 1st | 21.5 | 21.8 | 1.02 (0.69, 1.50) | 1.16 (0.72, 1.88) | 36.3 | 23.7 | 0.54 (0.40, 0.74) | 0.31 (0.17, 0.56) |

| 2nd | 24.5 | 38.7 | 1.95 (1.23, 3.08) | 1.96 (1.10, 3.50) | 34.1 | 22.5 | 0.56 (0.43, 0.73) | 0.68 (0.47, 0.98) |

| 3rd | 26.4 | 32.4 | 1.34 (0.93, 1.94) | 1.01 (0.59, 1.70) | 32.6 | 29.0 | 0.84 (0.66, 1.07) | 0.90 (0.67, 1.22) |

| 4th | 35.9 | 33.6 | 0.91 (0.63, 1.31) | 1.06 (0.63, 1.78) | 37.7 | 28.4 | 0.66 (0.53, 0.81) | 0.59 (0.45, 0.76) |

| Health condition | ||||||||

| Yes | 21.5 | 28.4 | 1.45 (1.03, 2.03) | 1.56 (1.03, 2.35) | 30.3 | 26.5 | 0.83 (0.70, 0.99) | 0.69 (0.53, 0.89) |

| No | 27.2 | 26.9 | 0.98 (0.78, 1.24) | 1.03 (0.74, 1.43) | 39.6 | 29.0 | 0.63 (0.53, 0.73) | 0.62 (0.50, 0.77) |

There was a decline in the number of participants achieving PA guidelines in the BA programs, with participants 35% less likely to meet guidelines at follow-up, compared to baseline (OR: 0.65, 95% CI 55, 0.76) (Table 3). This was particularly evident for those in the lowest SEIFA categories and those speaking a language other than English at home (Table 3). However, once engaged in the program, older adults in the BA program that spoke a language other than English at home typically spent more time in the funded activity (115 min) than native English speakers (100 min). Of all the older adults engaged, 27% also reported significant improvements in their balance after participation in the funded program.

The qualitative data also evidenced that targeted approaches to engage and deliver appropriate activities to new target groups was in engagement. Appropriate program design was also necessary to effectively retain participants to achieve PA guidelines through continued participation.

3.3. Adoption

A diverse range of 88 organisations were funded through the Move it AUS grant program, including 35 national sporting organisations (29 Participation, 6 BA), 7 state sporting organisations (4 Participation, 3 BA), 30 non-government organisations (22 Participation, 7 BA), 4 educational organisations (all Participation), 4 clinical organisations (all BA), and 8 local city councils (2 Participation, 6 BA).

The organisations were at different levels of readiness, which impacted the adoption and integration of the program within the organisations’ strategies for long term results. Our findings showed that organisations with existing internal buy-in from leaders were more likely be using the support from Sport Australia to scale-up an idea already in place, rather than scoping out a pilot to test the feasibility of a new product (Appendix B). The importance of a strong organisational commitment and the integration of positive internal communication supporting the funded activity was reported as critical to the successful adoption within organisations.

3.4. Implementation

The qualitative analysis of the interviews with program leads was synthesised into seven key insights (Appendix B):

Clarity of who organisations aimed to reach was provided in the Move It AUS grant guidelines informed program design, recruitment, and delivery to overcome barriers specific to the nominated target groups.

Partnerships were recognised as a mode of working synergistically to reach new audiences or provide new offerings designed to reducing physical inactivity through new target groups.

Communication was redefined externally to emphasise the fun, social, and non-competitive aspects of sport participation and internally to advocate for internal buy-in for the funded activity and new target audience.

Program designs included a traditional or modified sport, the provision of educational or capacity building resources, or a multifaceted approach. High quality program deliverers and program flexibility were central to the effective implementation and adoption of funded programs.

COVID-19 disruptions forced funded organisations to pivot online, which impacted reach and program delivery both positively and negatively. Although this time enabled organisations to reflect on improving key aspects of delivery, it also emphasised the importance social connections in project delivery.

Governance from Sport Australia allowed organisations to try new approaches in recruiting target groups and legitimised internal commitment to these new strategies.

Participation strategies to reduce physical inactivity were recognised as a priority across the sport ecosystem despite competing priorities for resourcing within funded organisations.

3.5. Maintenance

There was a 5% increase in participants in the Participation stream that was seen in those that “don’t know” whether they will drop out of sport or PA after the program, with a reduction in the proportion of participants who had already dropped out by 8.7%. A total of 91% of participants in the BA stream reported that they were planning to continue their current sports and physical activities at the post time point. This suggests there may be an impact of retention in programs, despite the impact of COVID-19 on participation opportunities.

The sustainability of programs was a common concern within funded organisations (coded under “program delivery” and “governance”) (Figure 1). Most interviewees reported that an extended grant delivery time would be preferable to allow consideration for mechanisms for sustainability. Other solutions presented by organisations included effective partnerships and continued collection of data on the impact of the program to support future grant applications and strategic directions (Figure 1).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate how a national grant program reached and engaged inactive communities in sport and physical activity, and to understand the impact on the capability and capacity of the sport sector to meet the needs of inactive communities. This is the first time that a nationally funded grant program in Australia has specifically targeted inactive participants and results suggest that the clear focus and strategic direction of the grant program was successful in recruiting inactive people. Despite the impact of COVID-19, the programs successfully demonstrated how organised sport can reach inactive populations and investment in sport can achieve health outcomes for these populations [5]. Seven key insights were synthesised from the results, providing an improved understanding on what works and what does not when designing and implementing PA and sport initiatives for inactive populations. Investments in “sport and recreation for all” have been listed as one of the Eight Best Investments to reduce physical inactivity [3,7]. This evaluation will inform policies that may better support sporting organisations as health promotion, supporting on this directive.

A major barrier to reducing physical inactivity is the initial engagement and reach to recruit key inactive groups [5,20]. The targeted approach of the Move It AUS grants were based on findings reported by both GAPPA, and through Sport Australia’s AusPlay data, which identified key inactive population groups [4,6]. Clarity enabled organisations to create a strategic focus and unified approach that guided all aspects of program delivery, helped identify key partners, and informed communication strategies. Funded organisations tried new communication strategies to reach new target groups that were like those found in other studies, including word of mouth, local marketing, and cross-promotion through partnerships [5,21]. Communication of sport as accessible to all, not just those that have experience in sporting activities is important and challenges perceived barriers to participation. However, methods to better engage primary target groups (including CALD, rural communities, and indigenous Australians) into organised PA and sport programs are still required [2].

Program design should begin with clearly defined target groups and include co-design where possible [5]. Challenging pre-conceived notions of sport as intimidating or out-of-reach through the development of beginner-friendly, non-competitive, and social options was reported as critical in engaging inactive participants. Core components of delivery should also include flexibility in delivery, embedded social opportunities, and skilled and qualified staff. The impact of a champion of the program within the organisation was emphasised by Ooms (et al., 2015) and signposts the importance of identifying and training skilled volunteers to deliver programs to ensure participant engagement and enjoyment [5]. Involvement in the funded PA programs presented an opportunity for community members to connect and create support networks. Sport and organised PA also have added benefits of group delivery, which have a positive impact on social and mental health across the lifespan [22]. Using sport as both a social connector and vehicle to achieve PA targets will be particularly relevant in recovering from the detrimental social, physical, and mental effects of experiencing various lockdowns and periods of social distancing due to COVID-19 [23,24].

There was a reduction in the proportion of participants achieving PA guidelines in the BA stream, most significantly observed in the most disadvantaged and CALD participants. Research has found that the effect of COVID-19 on population participation in PA was not equal, and further work is required to address the widening equity gap in PA, particularly in the return to sport and organised PA after COVID-19 [8,25]. However, our findings also reported that once engaged, CALD communities participating in BA programs engaged for an average of 15 mins longer each week in funded activities than English speakers. This evidences the feasibility of tailored programs as a gateway to achieve physical activity guidelines for inactive minority groups. Barriers to participation are greater for these minority groups, therefore, socioecological models for understanding participation rates may be used to better understand how to design and deliver effectively tailored organised sport and PA [26,27].

Recently released by World Health Organisation, the Fair Play advocacy brief has called for greater cross-sectoral collaboration to better engage and retain inactive target groups [2]. Our evaluation found that despite the complicated process of aligning strategic objectives organisations, partnerships were a critical factor to the success in reaching and delivering sport and PA programs to new target groups. Casey et al. (2011) made the case for long-term commitments in funding strategies and partnerships to provide sustainability, which was echoed from program providers concerned about resources required to maintain delivery [28]. Similarly, Staley et al. (2019) found that addressing inactivity through sport requires collaboration and support across multiple levels of the ecosystem [20]. Cross-sectoral collaboration is instrumental in reaching specific inactive target groups and should be embedded in future initiatives to support sustained delivery and fair access to sport and PA opportunities across the lifespan [2,5,28,29].

Limitations

Funded organisations were responsible for disseminating the surveys. Some surveys were not able to be determined at either time point but are included in the aggregate total of respondents. Some organisations modified the data collection methods during program delivery due to unforeseen practicality implications such as language barriers and available resourcing.

Findings would be strengthened in future with information on maintenance and the long-term impact of the Move It AUS grants, particularly in the absence of COVID-19 implications. Participation in the qualitative surveys was voluntary, and the possibility for self-selection bias should be noted.

5. Conclusions

The strong engagement of inactive people in Move It AUS funded programs demonstrates the success and acceptability of targeted interventions in engaging inactive people to reduce physical inactivity and improve health for all. The sport sector is motivated and mobilised to be part of the solution to physical inactivity, and integration of the seven key insights from this study can inform future policies and opportunities supporting sporting programs for inactive populations in the future. Utilising grant programs to broaden the population engagement throughout sport and enhance the capability of the sport sector is one strategy for increasing population levels of PA and understanding the unique contribution sport makes to our local communities.

Acknowledgments

Cameron French, Deputy General Manager, Sport Australia; Lisa Nugara, Director, Participation Design, Sport Australia; Matthew Warr, Assistant Director, Participation Design, Sport Australia; Tom Halliday, Adviser, Participation Design, Sport Australia; Jesse Kerrison, Project Officer, Participation Design, Sport Australia.

Appendix A. Interview Script

| QUESTIONS | INTERVIEWER PROMPTS |

| Project description & background | |

|

Which sport activity, target audience, capacity of the program, when is/has it been delivered, for how long, frequency, where is it being delivered, number of staff or volunteers |

|

Lead, Admin, coach, referee etc. |

|

Increase participation in general/of a target group, introduce a new product, collaborate with new partner? |

|

Website, media, people, Sport Australia, SSO, word of mouth etc. |

|

Financial, recognition of your organization, increase in business, collaboration etc. |

| Impact of recent events | |

|

Has your program been impacted by the 2019/20 bushfires/COVID-19 – Coronavirus, other factors? Or not affected at all? |

|

Program delivery is unchanged or near completion and will meet milestones, program delivery unchanged but may be affected in the future, program delivery affected and delivery will be delayed, program affected and format or activities delivered will have to be altered, it is too early to know how our program will be affected? |

|

Delay program delivery, alter program format or activities delivered? |

|

Will you finish the project by the project end date? Will you be able to spend and acquit funds by the due date? |

| A bit about your experience delivering the move it AUS program… | |

|

Positive/negative

How did you form this opinion? What is this based on? |

|

Issues related to travel, expense, security, competitiveness, engagement Yes- how and why do you think so? No- how and why do you think so? |

|

One of the target audiences highlighted in Move It Aus grant applications, or simply inactive population of a specific age group? Explain why that choice was made? |

|

Funds, engagement of effective deliverers who engage with target market, staff, attitudes of participants |

|

Participation rate, conversion to memberships, positive feedback |

|

Participation rate, Dropouts, barriers, implementation, staff, parental support, data collection, funds |

|

Attitudes, behaviours, secure environment, attractive spaces, less competitive atmosphere, engagement, awareness, knowledge, targeted approach |

|

Capacity building of the organization, staff recruitment, enhancement of the sporting area, targeted participation, how does the program fit within the organisational structure etc. |

| How does the funded program fit within your organisation? | |

|

Is it a new program or scaling/alteration of existing program? |

If yes, how? |

Recognition, collaborations, motivation to improve, employment etc. |

|

Increased membership, improved public perception of organisation, increased participation of target group etc. |

|

Targeted approaches to increasing participation amongst inactive or disengaged members of public? Or not at all? Why not? Is this the first time this approach has been taken and why? |

|

Implementation issues, target audience difficulties, staff management of the program, how did you keep the participants engaged, how has it impacted your key KPIs and organisational outcomes |

|

Capacity building – staff, volunteers, type of sports, frequency of program, means to increase participation rate, engagement, study the attitudes of target audience, technological support, collaboration etc. |

| Your funded program and organisation’s role within the global approach to reducing physical inactivity | |

|

Self-driven research, funding programs for the inactive, evaluation of programs on improving PA outside of this current evaluation? |

|

Which sport, geographical area, target group, effects of this sport on health |

|

Funds helped in capacity building, better provision of resources, technological support |

|

Your opinion |

|

Your opinion |

|

Culturally & linguistically diverse people, Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander people, people with disability, people living in rural/remote locations, and women & girls |

|

Yes/no - why? |

| Recommendations and next steps | |

|

Resources required, effective reach to target groups, |

|

Refer to earlier challenges |

|

Ensure effective program planning & staff recruitment to effectively roll out program, plan of previous attempts |

|

|

Appendix B. Qualitative Interview Quotations within the RE-AIM Framework

| Re-Aim Theme | Quote |

| Reach | “How, how do you get people to exercise more? You change their mind… Shifting of attitudes, and the conversations we’ve had internally is an ongoing thing and you can’t put a monetary value to it. But it was a big part of our programme and it will continue to be, going forward.” |

|

“The messaging we had around it was, have a go, enjoy it with your friends, get fit, feel better, this is good medicine, this is good stuff for you. This is going to help you and help you feel much better. You can have fun with your mates” “I would probably suggest for them to really look at how they can leverage relationships with stakeholders and people who have a respect and access to community members in a particular area.” | |

| Effectiveness | “We saw an 81% increase or improvement in their sit-to-stand test scores [after 8-weeks of participation in the funded activity], so their mobility, which is huge. And then we saw a 68% increase in their grip strength. Which doesn’t sound like much but for seniors can be really important.” |

| “Having that really targeted approach and consulting with the communities that we’re trying to target is something that we do, but we just didn’t really think about it in as much detail or had time to do what we did for the Move it AUS grant.” | |

| “I think it gave [the participants] a bit of motivation to start on getting healthier and that was what a lot of them needed. And I think it also broke down a few barriers for them. Walking into a gym or a sporting organisation I think could be quite threatening for people from another culture. And they got such a warm response that I think that broke down a lot of barriers.” | |

| Adoption | “We would almost be back at square one, or not far down the track, if we hadn’t had the opportunity through the grant.” |

| “The other challenge is trying to convince people around us. I’m in that female participation space, but [we need] our decision makers [to understand] why this programme is really important, and for them to understand that this is the opportunity, and we’ve got to support this, not just because it’s a grant… But that this is absolute key… We keep talking about wanting to be different, and we want to do things differently, we’ve got this opportunity, so, let’s do it.” | |

| “The change sport is providing is challenging the norm now. It pushes us to be innovative. I think that’s such a positive thing. To be pushed out of your comfort zone and to see what you can do because there’s some, some incredible outcomes that come from that.” | |

| “From an internal perspective… The message that we really tried to get across is that [the] terminology is changing. Consumption of sport is changing and has changed over the last five years, and if [our sport] wants to remain relevant in the space, meaning we need to keep having people participate in our sport to actually make their way up the pathway to high performance, we needed to adopt to some of this terminology change [to include participation strategies], which meant challenging the norm.” | |

| Implementation | “So, we’ve created a new what we call a community instructor module, which is basically a course for all our coaches to do to upskill and to up-educate in our national programs. So, we’ve built in a lot of the focus through that. It’s sort of the same in terms of the senior program as well. It’s really about educating our deliverers and making sure they understand the needs of these groups.” |

| “We’ve been talking about this legacy… that we use this premise of activation of spaces and sporting clubs to target a wider variety of people who are inactive. [To] provide those introductory… non-threatening activities, the accessible ones in terms of costs and geographical location… so that we’re seeing more concerted effort to get underrepresented population groups physically active.” | |

| “This funding has… given us a platform to say, we don’t have to do things the same way that it has been done… and it’s challenged the norm.” | |

| Maintenance | “This was a good opportunity for us to run a program, but also bring on board some partners that would help us tell that story, people like ESSA with some surveys and data analysing… [It] also gave us some very important data so that we could tell the story later.” |

| “We need a strong national PA strategy that is cross-government, that engages everyone. That involves organised sport, that involves active outdoor recreation. That involves fitness, that involves active transport and that involves play. We need something broader, and it needs to be integrated so we’re not all scrambling to get dollars but we’re all actually working together because that’s the only way we’ll achieve success.” |

Author Contributions

L.J.R. acquired the contract; L.J.R., B.C.F. and K.B.O. contributed to the conceptualization and design of the research. C.L.R. led project management and the data collection and storage. C.L.R., L.J.R., B.C.F. and K.B.O. collaborated on the evaluation of data. C.L.R. and B.C.F. conducted the analysis of qualitative data. K.B.O. led the statistical interpretation of data. C.L.R. and L.J.R. led the writing of this paper, with significant contributions in the draft and editing components made by B.C.F. and K.B.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of Sydney Ethics committee (reference numbers 2019/533 and 2020/250).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Sport Australia delivered a federally funded grant, Move It AUS, which was evaluated in this paper. This study was funded by Sport Australia to evaluate the impact of this grant. At the time of data collection, there were no other competing interests. At the time of manuscript submission, L.R. is an employee of Sport Australia, however, there are no known vested interests related to this research connected to this position.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Australian Sports Commission through Sport Australia by way of a privately contracted evaluation agreement. All research was conducted independently of Sport Australia.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Australian Government: Department of Health Australia’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines and the Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines. [(accessed on 26 May 2022)];2019 Available online: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-strateg-phys-act-guidelines.

- 2.WHO Fair Play: Building a Strong Physical Activity System for More Active People. 2021. [(accessed on 3 June 2021)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HEP-HPR-RUN-2021.1.

- 3.Bull F.C., Al-Ansari S.S., Biddle S., Borodulin K., Buman M.P., Cardon G., Carty C., Chaput J.P., Chastin S., Chou R., et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020;54:1451–1462. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO . Global Action Plan on Physical Activity (GAPPA) 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2018. [(accessed on 3 June 2021)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/ncds/prevention/physical-activity/global-action-plan-2018-2030/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ooms L., Veenhof C., Schipper-van Veldhoven N., de Bakker D.H. Sporting programs for inactive population groups: Factors influencing implementation in the organized sports setting. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2015;7:12. doi: 10.1186/s13102-015-0007-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sport 2030 Canberra2018. [(accessed on 15 April 2021)]; Available online: https://www.sportaus.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/677894/Sport_2030_-_National_Sport_Plan_-_2018.pdf.

- 7.ISPAH Eight Investments that Work for Physical Activity 2020. [(accessed on 22 May 2021)]. Available online: https://www.ispah.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/English-Eight-Investments-That-Work-FINAL.pdf.

- 8.Sher C., Wu C. Who Stays Physically Active during COVID-19? Inequality and Exercise Patterns in the United States. Socius. 2021;7:2378023120987710. doi: 10.1177/2378023120987710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koorts H., Gillison F. Mixed method evaluation of a community-based physical activity program using the RE-AIM framework: Practical application in a real-world setting. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1102. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2466-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dzewaltowski D.A., Estabrooks P.A., Glasgow R.E. The future of physical activity behavior change research: What is needed to improve translation of research into health promotion practice? Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2004;32:57–63. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200404000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaglio B., Shoup J.A., Glasgow R.E. The RE-AIM framework: A systematic review of use over time. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;103:e38–e46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss C.H. Nothing as Practical as Good Theory: Exploring Theory-Based Evaluation for Comprehensive Community Initiatives for Children and Families. 2011. [(accessed on 3 June 2021)]. Available online: https://canvas.harvard.edu/files/1453087/download?download_frd=1&verifier=IVZpf0ynt3iriSXpb8lE7WirRBXUHfbceDQUHleG.

- 13.Fynn J.F., Hardeman W., Milton K., Jones A. Exploring influences on evaluation practice: A case study of a national physical activity programme. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021;18:31. doi: 10.1186/s12966-021-01098-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes For Areas (SEIFA) Canberra. [(accessed on 3 June 2021)];2016 Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/2033.0.55.001.

- 15.Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 5—Remoteness Structure, July 2016 Canberra 2018. [(accessed on 8 February 2021)]; Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1270.0.55.005.

- 16.Prochaska J.J., Sallis J.F., Long B. A physical activity screening measure for use with adolescents in primary care. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2001;155:554–559. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milton K., Bull F.C., Bauman A. Reliability and validity testing of a single-item physical activity measure. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011;45:203–208. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.068395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.AusPlay Australian Government: Canberra 2016–21. [(accessed on 27 November 2021)]; Available online: https://www.clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/research/ausplay.

- 19.Ritchie J., Spencer L. Analyzing Qualitative Data. Routledge; London, UK: 1994. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Staley K., Donaldson A., Randle E., Nicholson M., O’Halloran P., Nelson R., Cameron M. Challenges for sport organisations developing and delivering non-traditional social sport products for insufficiently active populations. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 2019;43:373–381. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williamson C., Kelly P., Baker G. A conceptual framework for physical activity messaging. [(accessed on 26 May 2022)];Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020 Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336956859_A_conceptual_framework_for_physical_activity_messaging. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenkin C.R., Eime R.M., Westerbeek H., O’Sullivan G., van Uffelen J.G.Z. Sport and ageing: A systematic review of the determinants and trends of participation in sport for older adults. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:976. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4970-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faulkner J., O’Brien W.J., McGrane B., Wadsworth D., Batten J., Askew C.D., Badenhorst C., Byrd E., Coulter M., Draper N., et al. Physical activity, mental health and well-being of adults during initial COVID-19 containment strategies: A multi-country cross-sectional analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2021;24:320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2020.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Son J.S., Nimrod G., West S.T., Janke M.C., Liechty T., Naar J.J. Promoting Older Adults’ Physical Activity and Social Well-Being during COVID-19. Leis. Sci. 2021;43:287–294. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2020.1774015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Australian Government: Canberra 2016–21 2021AusPlay: Ongoing Impact of COVID-19 on Sport and Physical Activity Participation. [(accessed on 1 July 2021)]; Available online: https://www.clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/1012846/AusPlay-COVID-19-update-June-2021.pdf.

- 26.Caperchione C.M., Kolt G.S., Tennent R., Mummery W.K. Physical activity behaviours of Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) women living in Australia: A qualitative study of socio-cultural influences. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson A., Abbott R., Macdonald D. Indigenous Austalians and physical activity: Using a social–ecological model to review the literature. Health Educ. Res. 2010;25:498–509. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casey M.M., Payne W.R., Brown S.J., Eime R.M. Engaging community sport and recreation organisations in population health interventions: Factors affecting the formation, implementation, and institutionalisation of partnerships efforts. Ann. Leis. Res. 2009;12:129–147. doi: 10.1080/11745398.2009.9686815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casey M.M., Payne W.R., Eime R.M. Partnership and capacity-building strategies in community sports and recreation programs. Manag. Leis. 2009;14:167–176. doi: 10.1080/13606710902944938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.