Abstract

Background:

Since cannabis has been legalized in Canada for medical and recreational use, there has been an increased demand on pharmacists for cannabis counselling. The objective of this study was to determine the concerns, beliefs and attitudes of Canadian pharmacists and pharmacy students towards using cannabis.

Methods:

An online survey was synthesized under 3 broad themes: concerns, beliefs and attitudes about cannabis, consisting of 27 questions capturing demographics and Likert scale responding to survey questions. We examined whether there were differences in responses by geographic location (i.e., Ontario, Quebec, Canada), sex or practice setting (i.e., community, hospital).

Results:

Across Canada, there were 654 survey respondents, with 399 in Ontario and 95 in Quebec. Approximately 24% indicated they had used cannabis since legalization, 69% indicated they believed cannabis should be available for medical and recreational use and 34% indicated their perceptions towards cannabis had become more positive since legalization. Relative to Quebec or the rest of Canada, respondents from Ontario were significantly more likely to be comfortable providing counselling to and answering questions of patients on the safety and efficacy of medical cannabis use. Examining sex differences across Canada, male respondents were more comfortable than female counselling patients on the safety and efficacy of medical cannabis.

Conclusion:

The current results reinforce the perceived need by pharmacists and pharmacy students for targeted education, and future research in cannabis education should consider potential gender differences in attitudes and beliefs surrounding cannabis therapy.

Introduction

In October 2018, the Cannabis Act went into effect, whereby the Government of Canada legalized the possession, use, cultivation and purchase of cannabis for recreational use by individuals who are, depending on the province, 18, 19 or 21 years of age and older. 1 From a health care perspective, medicinal use of cannabis refers to use based on a prescription or recommendation by a registered physician or nurse practitioner, for a known medical condition, with evidence demonstrating its indication and efficacy.

Knowledge into Practice.

Cannabis was legalized in Canada for medical purposes in 2001 and recreational purposes in 2018.

Attitudes of medical professionals influence patient care, but few studies focus on pharmacists.

This study provides an overview of the knowledge and confidence of pharmacists towards providing patient care as it relates to cannabis and demonstrates the importance of education in optimizing patient care under a backdrop of increasing cannabis legalization.

Stronger education of pharmacists and students may enhance counselling abilities and confidence, which are determinants of quality patient care.

Pharmacists play a frontline role in helping guide patients through their medical cannabis therapy and must uphold the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence. Indeed, the lack of strong evidence for medical cannabis therapy ensures continued ethical and legal concern among practising pharmacists. Evidence of clinical efficacy does exist, however, and a recent systematic review of 79 randomized controlled trials showed that there was moderate-quality evidence to support the use of cannabinoids for the treatment of chronic pain and spasticity, whereas low-quality evidence suggested that cannabinoids were associated with improvements in nausea and vomiting due to chemotherapy, weight gain in HIV infection, sleep disorders and Tourette syndrome. 2

Although cannabis research and training is still in its infancy, some professional associations have developed educational materials on cannabis. 3 Of concern, however, a recent survey of Canadian undergraduate pharmacy programs found that on average, merely 4 hours were devoted to cannabis-related material among the 9 faculties, ranging from as little as 0.5 hours up to 12.5 hours in any given program. 4 In an attempt to balance gaps in training and continuing education, the Ontario College of Pharmacists recently mandated that all practising pharmacists complete a Canadian Council on Continuing Education in Pharmacy (CCCEP) 2.5 CEUs in order to renew their practice licences. 3 To date, Ontario is the only province that mandates this training.

It is known that health care provider attitudes and beliefs can influence the care that they provide.5,6 As a result, there is a growing body of evidence assessing the attitudes and beliefs of health care providers as they relate to the use of medical cannabis. Because of the increased need for cannabis counselling, evidence on perceived knowledge of cannabis and the pharmacist’s comfort level on providing cannabis counselling is growing.7,8 However, there is a gap in the literature when it comes to Canadian pharmacists’ attitudes and perspectives toward cannabis; 9 furthermore, as far as the authors are aware, no studies have assessed attitudes and perspectives on use in pediatric patients. Since pharmacists play a pivotal role in medication management and safety, as well as public education, it is imperative to understand their attitudes towards the consumption of cannabis.

The objective of this study was to explore the attitudes of pharmacists and pharmacy students in Canada towards using cannabis for both medical and recreational purposes. More specifically, we wanted to identify their concerns over providing advice and on the legality of dispensing cannabis to patients. Secondary objectives were to examine potential differences in responses by geographic location (i.e., Ontario, Quebec, Canada) and explore potential differences in responses by sex. It was hypothesized that due to the recent mandatory cannabis e-learning requirements by the Ontario College of Pharmacists, respondents from Ontario would have fewer concerns regarding providing advice on medical and recreational cannabis.

Methods

Participants

The inclusion criteria for this study were to be either a pharmacy student or a pharmacist in Canada. For Quebec, the respondents needed to understand French and, for the rest of Canada, English.

Participants were recruited from July 14, 2020, to October 28, 2021, by sharing the link to the survey on social media and with pharmacist associations and colleges across Canada to distribute to their respective members. Completion of the survey was taken as implied consent. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Research and Ethics Board at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO).

Survey development

A review of the literature on surveys assessing the knowledge and attitudes of pharmacists, pharmacy students and other health care professionals toward cannabis use was conducted through PubMed and Google Scholar. A 27-item questionnaire was subsequently developed that focused on 3 key themes on cannabis use: 1) concerns, 2) beliefs and 3) attitudes. The questionnaire was written in English and was translated into French. The survey link directed participants to the secure web-based survey administered using the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) platform.

Definitions for cannabis use were operationalized in the survey as follows: 1) medically supervised use of cannabis was defined as cannabis used under medical supervision (Medical Cannabis); 2) self-medicating cannabis use was defined as cannabis used for perceived medical purposes but without medical supervision (Self-medicating Cannabis); and 3) recreational cannabis use was defined as cannabis used for nonmedical purposes (Recreational Cannabis).

After responding to questions on demographics, participants were asked to comment on their worries and concerns regarding medical and recreational cannabis, as well as their concerns regarding the legality of providing advice and dispensing cannabis to patients using a 5-item Likert scale, with 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree and 5 = strongly agree.

Respondents were asked for their beliefs on the legality of cannabis for medical and recreational uses with the following responses: 1 = legal for medical and recreational use, 2 = legal for medical use only and 3 = illegal for medical and recreational use.

Questions on frequency of advice for medical and recreational cannabis were answered using a 5-item Likert scale, with 1 = never, 2 = rarely (less than twice per month), 3 = sometimes (2 to 4 times per month), 4 = often (once per week) and 5 = frequently (more than once per week).

Statistical plan

Comparisons were made by geographic location (Ontario, Quebec and Canada) and by sex (male vs female). Pharmacists and pharmacy students from Ontario were compared with those from all other provinces (i.e., Ontario vs Canada), as well as with Quebec only (i.e., Ontario vs Quebec), and the third comparison by geographic location was Quebec compared to the rest of Canada (i.e., Quebec vs Canada). This approach to grouping by geographic location was taken due to the relatively small numbers of those responding from provinces other than Ontario and Quebec.

Independent sample t tests were used to examine demographic differences and 2 × 2 and 2 × 5 chi-square tests of independence were used to examine differences in responding to survey questions on concerns, beliefs and attitudes. Standardized residuals were analyzed to determine which cells contributed significantly to the results. When a standardized residual is greater than 2, the cell is contributing significantly to the differences between groups. The Cramer’s V statistic was used to test the strength of association between 2 categorical variables. This is an appropriate test to use after the chi-square statistic is found to be significant. 10 Statistical significance was bound by a p-value of <0.05.

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants, geographically grouped by Ontario, Quebec or all of Canada (n = 654).

Table 1.

Characteristics of pharmacists and pharmacy students who participated in the survey

| Ontario (n = 399) | Quebec (n = 95) | Canada (n = 654)* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n (%) | Sum total | n (%) | Sum total | n (%) | Sum total |

| Sex | 396* | 95 | 654 | |||

| Male | 162 (40.9) | 24 (25.2) | 227 (34.7) | |||

| Female | 227 (57.3) | 71 (74.8) | 413 (63.1) | |||

| Prefer not to say | 7 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 10 (1.5) | |||

| Pharmacy status | 399 | 95 | 654 | |||

| Pharmacist | 352 (88.2) | 94 (98.9) | 584 (89.3) | |||

| Pharmacy student | 47 (11.8) | 1 (1.1) | 70 (10.7) | |||

| Degree | ||||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 123 (30.8) | 10 (10.5) | 172 (26.3) | |||

| Bachelor’s degree in pharmacy | 256 (64.2) | 57 (60) | 439 (67.1) | |||

| Doctorate degree (i.e., PharmD) | 90 (22.6) | 24 (25.3) | 135 (20.6) | |||

| Master’s degree in pharmacy | 23 (5.8) | 20 (21.1) | 46 (7) | |||

| Doctor of philosophy degree | 3 (0.8) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (0.6) | |||

| Hospital pharmacy residency | 40 (10) | 5 (5.3) | 78 (11.9) | |||

| Industrial pharmacy residency | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.5) | |||

| Not applicable | 11 (2.8) | 2 (2.1) | 4 (0.6) | |||

| Practice setting | 390† | 95 | 644† | |||

| Industry | 6 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 6 (1.0) | |||

| Government | 5 (1.3) | 3 (3.2) | 10 (1.6) | |||

| Military | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.5) | |||

| Community | 223 (57.3) | 67 (70.5) | 358 (55.6) | |||

| Hospital | 113 (28.9) | 18 (18.9) | 206 (31.9) | |||

| Academia | 3 (0.8) | 1 (1.0) | 6 (0.9) | |||

| Consultant or primary care (family health team) | 15 (3.8) | 3 (3.2) | 22 (3.4) | |||

| Other | 23 (5.9) | 3 (3.2) | 33 (5.1) | |||

| Practice location | 387* | 95 | 640* | |||

| Rural | 70 (17.5) | 29 (30.5) | 132 (20.2) | |||

| Urban | 317 (79.4) | 66 (69.5) | 508 (77.7) | |||

The respondents from all of Canada consisted of the following: Newfoundland, n = 3 (0.5%); Nunavut, n = 1 (0.2%); Nova Scotia, n = 21 (3.2%); Prince Edward Island, n = 10 (1.5%); New Brunswick, n = 39 (6%); Quebec, n = 95 (14.5%); Ontario, n = 399 (61%); Manitoba, n = 4 (0.6%); Saskatchewan, n = 35 (5.4%); Alberta, n = 21 (3.2%); British Columbia, n = 25 (3.8%) and Northwest Territories, n = 1 (0.2%) (results not shown due to pooling of data).

Represents unfilled values in the survey (missing cases).

There were significantly more females than males who responded to the survey for all of Canada (p < 0.01), as well as in the provinces of Ontario (p < 0.01) and Quebec (p < 0.001). There were significantly more community pharmacists than hospital pharmacists, respectively, who responded to the survey for all of Canada (p < 0.01), as well as in the provinces of Ontario (p < 0.01) and Quebec (p < 0.001).

Legality of cannabis use

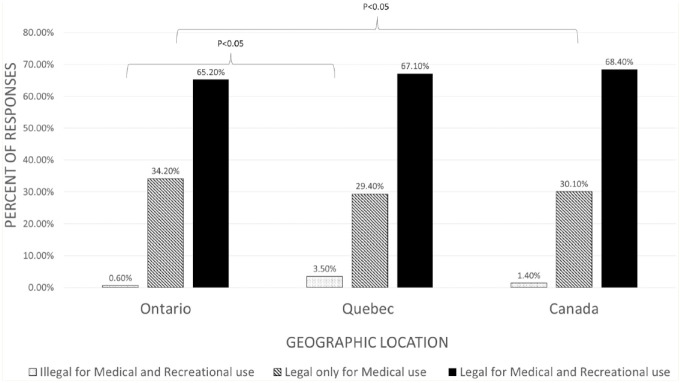

The results regarding the legality of cannabis use are seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Percentage of responses by geographic location and by practice setting for the survey questions on the legality of medical and recreational cannabis*

*The survey questions all began “I think cannabis should be. . . .”

There was a significant impact of geographic location (χ2 = 7.4, df = 2, V = 0.11, p < 0.05), where compared to the rest of Canada, those from Ontario were less likely to believe that cannabis should be “available only for medical use.” Compared to Ontario, those from Quebec were more likely to think that cannabis should be “illegal for medical and recreational use” (χ2 = 6.5, df = 2, V = 0.11, p < 0.05). There were no significant differences in response by sex.

Worries and concerns about legal repercussions

The percentage of responses from pharmacists and pharmacy students on their worries and concerns regarding potential repercussions associated with dispensing cannabis and providing advice is seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Percentage of responses from pharmacists and pharmacy students on their worries and concerns regarding potential repercussions associated with dispensing cannabis and providing advice

| Survey question | 1 = Strongly disagree | 2 = Disagree | 3 = Neither disagree nor agree | 4 = Agree | 5 = Strongly agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I worry that patients who request medical cannabis may actually want it for recreational purposes | |||||

| Ontario (397) | 13.4 | 29.2 | 24.2 | 24.2 | 9.0 |

| Quebec (95) | 16.8 | 39.0 | 16.8 | 22.1 | 5.3 |

| Canada (651) | 13.7 | 30.1 | 23.2 | 23.5 | 9.5 |

| I worry that medical cannabis use may lead to the use of other drugs for recreational purposes | |||||

| Ontario (399) | 22.3 | 32.9 | 19.5 | 17.3 | 8.0 |

| Quebec (94) | 21.2 | 50.0 | 16.0 | 9.6 | 3.2 |

| Canada (653) | 21.9 | 36.4 | 19.4 | 14.4 | 7.8 |

| I am concerned there may be legal repercussions to providing advice on medical cannabis | |||||

| Ontario (398) | 26.6 | 34.4 | 17.8 | 17.6 | 3.5 |

| Quebec (94) | 44.7 | 33.0 | 11.8 | 10.6 | 0.0 |

| Canada (652) | 28.8 | 34.0 | 17.3 | 15.6 | 4.1 |

| I am concerned there may be legal repercussions to providing advice on recreational cannabis | |||||

| Ontario (396) | 20.5 | 26.8 | 20.5 | 21.2 | 11.1 |

| Quebec (94) | 34.0 | 24.5 | 16.0 | 14.9 | 10.6 |

| Canada (650) | 22.3 | 26.0 | 18.6 | 21.4 | 11.7 |

| I am concerned there may be legal repercussions to dispensing medical cannabis to patients | |||||

| Ontario (396) | 27.8 | 29.5 | 20.2 | 15.9 | 6.6 |

| Quebec (95) | 37.9 | 33.7 | 14.7 | 10.5 | 3.2 |

| Canada (651) | 28.1 | 30.0 | 20.4 | 15.7 | 5.8 |

Dispensing medical cannabis

There was a significant impact of geographic location (χ2 = 9.3, df = 4, V = 0.12, p < 0.05), where compared to the rest of Canada, those from Quebec were more likely to be concerned about the legal repercussions of dispensing medical cannabis to patients.

A significant sex difference regarding concerns about legal repercussions of dispensing medical cannabis to patients was found (χ2 = 11.0, df = 4, V = 0.25, p < 0.05), where compared to females from Ontario, females from Quebec were more likely to be concerned about legal repercussions of dispensing medical cannabis to patients. Similarly, compared to females from the rest of Canada, females from Quebec were more likely to be concerned about legal repercussions of dispensing medical cannabis to patients (χ2 = 12.0, df = 4, V = 0.17, p < 0.05).

Providing advice on medical cannabis

Responses from Quebec indicate that pharmacists and students are less likely to be concerned with legal repercussions of providing advice on medical cannabis (χ2 = 15.56, df = 4, V = 0.17, p = 0.004). There was no significant difference between Ontario and Canada in concern over legal repercussions associated with providing advice on medical cannabis.

A significant sex difference regarding concerns about legal repercussions of providing advice on medical cannabis to patients was found (χ2 = 12.5, df = 4, V = 0.20, p < 0.05), where compared to females from Ontario, females from Quebec were more likely to be concerned about legal repercussions. No significant difference was noted for males.

Providing advice on recreational cannabis

Compared to Canada, responses from Quebec indicate they are less likely to be concerned with legal repercussions of providing advice on recreational cannabis (χ2 = 9.57, df = 4, V = 0.12, p = 0.04). There was no significant difference between Ontario and Canada or between Ontario and Quebec in concern over legal repercussions associated with providing advice on recreational cannabis.

There were no significant differences in responses by sex.

Role of medicinal cannabis in adult and child therapy

Respondents from Quebec were more likely to agree that medical cannabis has a place in adult therapy compared to the rest of Canada (χ2 = 14.8, df = 4, V = 0.15, p < 0.01). No significant differences were noted in the role of therapy of children or according to sex.

Frequency of advice provided to patients

The results regarding how often advice is provided to patients on recreational and medicinal cannabis can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Percentage of responses by geographic location regarding how often advice is provided to patients on medicinal and recreational cannabis

| Survey question | 1 = Never | 2 = Rarely (less than twice per month) | 3 = Sometimes (2 to 4 times per month) | 4 = Often (once per week) | 5 = Frequently (more than once per week) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How often do you provide advice to patients on medical cannabis? | |||||

| Ontario (399) | 28.3 | 49.4 | 16.8 | 3.8 | 1.8 |

| Quebec (95) | 37.9 | 51.6 | 7.4 | 1.1 | 2.1 |

| Canada (653) | 38.2 | 46.5 | 11.8 | 2.8 | 0.8 |

| How often do you provide advice to patients on recreational cannabis? | |||||

| Ontario (396) | 49.7 | 37.6 | 9.6 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Quebec (95) | 45.3 | 43.2 | 7.4 | 3.2 | 1.1 |

| Canada (650) | 49.9 | 37.8 | 9.2 | 2.2 | 0.9 |

There were no significant associations in how often advice is provided to patients on medicinal or recreational cannabis.

Comfort providing advice on safety and efficacy

Comfort providing advice on the safety of medical cannabis use

Regarding the safety of medical cannabis use, there was a significant impact of geographic location (χ2 = 32.6, df = 4, V = 0.22, p < 0.001), where compared to the rest of Canada, those from Ontario were more likely to be comfortable providing advice on the safety of medical cannabis.

Similarly, respondents from Ontario were more comfortable with advice on safety than those in Quebec (χ2 = 17.1, df = 4, V = 0.12, p < 0.01). Compared to the rest of Canada, those from Quebec were less likely to be comfortable providing advice on the safety of medical cannabis.

A significant difference was identified by sex (χ2 = 14.7, df = 2, V = 0.22, p < 0.01), where compared with females from the rest of Canada, females from Quebec were less likely to be comfortable providing advice on the safety of medical cannabis.

Comfort providing advice on the efficacy of medical cannabis use

A significant difference was identified by geographic location. Respondents from Ontario and Quebec were more likely to be comfortable providing counselling and answering questions from patients about cannabis use regarding efficacy compared to the rest of Canada (χ2 = 47.46, df = 4, V = 0.27, p < 0.001 and χ2 = 11.97, df = 4, V = 0.13, p < 0.05, respectively). However, respondents from Ontario were more likely to be comfortable than respondents from Quebec (χ2 = 22.5, df = 4, V = 0.21, p < 0.001).

A significant difference across all of Canada was identified by sex on comfort providing counselling and answering questions from patients about cannabis use regarding efficacy (χ2 = 24.6, df = 4, V = 0.21, p < 0.001), where compared to males, females were less likely to be comfortable discussing efficacy. When compared to female responses from Ontario, females from Quebec were significantly less likely to be comfortable providing advice on efficacy (χ2 = 11.94, df = 2, V = 0.20, p < 0.05).

Beliefs in the role of pharmacy in dispensing medical cannabis and comfort in discussing medical and recreational cannabis use with patients

The percentage of survey responses regarding personal beliefs on the role of pharmacy in dispensing medical cannabis and comfort in discussing medical and recreational cannabis use with patients can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Percentage of survey responses regarding personal beliefs of the role of pharmacy in dispensing medical cannabis and comfort in discussing medical and recreational cannabis use with patients

| Survey question | 1 = Strongly disagree | 2 = Disagree | 3 = Neither disagree nor agree | 4 = Agree | 5 = Strongly agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I would be willing to dispense medicinal cannabis in my pharmacy if it were legal to do so | |||||

| Ontario (398) | 11.6 | 7.3 | 16.6 | 35.2 | 29.4 |

| Quebec (95) | 8.4 | 7.4 | 14.7 | 32.6 | 36.8 |

| Canada (653) | 9.8 | 7.5 | 16.5 | 36.8 | 29.4 |

| I feel medical cannabis should be dispensed only by a licensed pharmacy | |||||

| Ontario (398) | 5.8 | 8.1 | 13.1 | 31.7 | 41.3 |

| Quebec (95) | 9.5 | 8.4 | 14.7 | 26.3 | 41.1 |

| Canada (652) | 6.4 | 9.7 | 15.8 | 30.9 | 37.3 |

| I think most medical cannabis users need the intervention of pharmacists | |||||

| Ontario (397) | 3.8 | 10.8 | 22.4 | 39.5 | 23.4 |

| Quebec (95) | 3.2 | 5.3 | 12.6 | 42.1 | 36.8 |

| Canada (652) | 3.5 | 10.9 | 21.6 | 38.8 | 25.2 |

| I think most recreational cannabis users need the intervention of pharmacists | |||||

| Ontario (398) | 14.8 | 28.9 | 26.4 | 19.8 | 10.1 |

| Quebec (94) | 13.8 | 23.4 | 31.9 | 23.4 | 7.4 |

| Canada (652) | 14.3 | 29.9 | 26.2 | 20.4 | 9.2 |

| I feel comfortable discussing medical cannabis use with patients | |||||

| Ontario (396) | 6.3 | 10.9 | 19.2 | 37.9 | 25.8 |

| Quebec (94) | 12.8 | 16 | 19.1 | 33 | 19.1 |

| Canada (648) | 8.3 | 14.5 | 20.2 | 35.5 | 21.5 |

| I feel comfortable discussing recreational cannabis use with patients | |||||

| Ontario (398) | 13.8 | 19.3 | 22.1 | 27.9 | 16.8 |

| Quebec (95) | 20 | 24.2 | 17.9 | 27.4 | 10.5 |

| Canada (653) | 15.3 | 21.9 | 21.7 | 26.8 | 14.2 |

For each geographic location, the sum of responses to each survey question is in brackets.

There were no significant differences, neither by geographic location nor by sex.

Use of cannabis since legalization and change in perception and worry that medical cannabis will lead to misuse and to the use of other recreational drugs (e.g., gateway effect)

Used cannabis since legalization?

Since legalization, across Canada, 24.3% (n = 159) of respondents have used cannabis. For Ontario, 23.3% (n = 93) have used since legalization and only 11.6% (n = 11) in Quebec.

There were no significant differences in responses between Ontario and the rest of Canada. However, compared to Ontario, respondents from Quebec were less likely to respond that they have used cannabis since legalization (χ2 = 7.7,df = 2, V = 0.12, p < 0.05). Similarly, compared to the rest of Canada, respondents from Quebec were less likely to respond that they have used cannabis since legalization (χ2 = 11.8, df = 2, V = 0.16, p < 0.01).

A significant sex difference regarding whether respondents have used cannabis since legalization of medical cannabis therapy in adults was found (χ2 = 21.7, df = 2, V = 0.16, p < 0.01), where compared to the rest of Canada, female respondents from Quebec were less likely to have used cannabis since legalization (1.2% vs 19.9%, respectively). No significant differences were noted for males.

Worry that patients who request medical cannabis may actually want it for recreational purposes

There were no significant differences in worry that patients who request medical cannabis may actually want it for recreational purposes, neither by geographic location, sex, nor practice setting.

Worry that medical cannabis use may lead to the use of other drugs for recreational purposes (gateway drug)

There were no significant differences in responses between Ontario and Canada on the worry that medical cannabis use may lead to the use of other drugs for recreational purposes.

Compared to Ontario, respondents from Quebec differed in their level of worry (χ2 = 12.1, df = 4, V = 0.15, p < 0.05), where those from Quebec were more likely to be worried that medical cannabis use may lead to the use of other drugs for recreational purposes.

Similarly, compared to the rest of Canada, respondents from Quebec significantly differed on their worry (χ2 = 11.0, df = 4, V = 0.13, p < 0.05), where those from Quebec were more likely to be worried that medical cannabis use may lead to the use of other drugs for recreational purposes.

There were no significant differences by sex.

Perception changed since legalization?

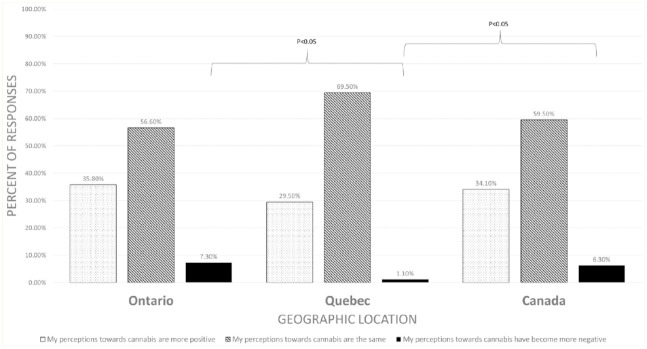

Figure 2 shows the frequency of response by geographic location to the question of whether perception of cannabis has changed since legalization.

Figure 2.

Percentage of responses from pharmacists and pharmacy students to the following survey question: “How have your perceptions towards cannabis changed since legalization?”

There were no significant differences between Ontario and Canada on the perception of cannabis since legalization. However, compared to Ontario, respondents from Quebec were less likely to indicate that their perceptions are more negative (χ2 = 7.9, df = 2, V = 0.12, p < 0.05). Similarly, compared to the rest of Canada, respondents from Quebec were less likely to indicate that their perceptions are more negative (χ2 = 7.37, df = 2, V = 0.10, p < 0.05).

Which indications or symptoms do you think cannabis may be helpful for in adults or children?

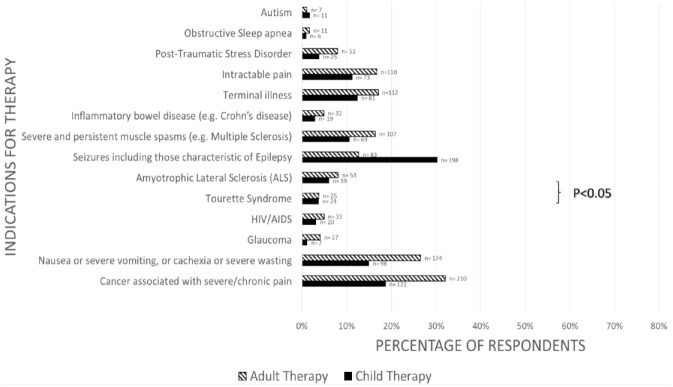

The percentage of responses from pharmacists and pharmacy students across all of Canada who believe medical cannabis has a place in medical therapy by various prespecified indications can be seen in Figure 3. There were no significant differences for whether medical cannabis has a place in medical therapy of adults or of children, neither by geographic location, sex, nor practice setting.

Figure 3.

Percentage of responses from pharmacists and pharmacy students across all of Canada who believe medical cannabis has a place in medical therapy by various prespecified indications*

*The question posed was as follows: “Which indications or symptoms do you think cannabis may be helpful for?” Participants were allowed to choose multiple indications and the question was posed separately for adults and children.

Respondents were more likely to choose that cannabis has a place in child therapy only for seizures, including those characteristic of epilepsy, compared to adults (30% vs 12.7%, p < 0.05). For all other indications, there were no significant differences on responses between indications for adult and child therapy. Notably for all other indications beside seizures, respondents were less likely to consider cannabis as a therapy for children than for adults.

Discussion

The objective of the current study was to determine the attitudes of pharmacists and pharmacy students in Canada towards the use of cannabis for both medical and recreational purposes, as well as to identify their concerns regarding providing advice and on the legality of dispensing cannabis to patients. In all of Canada, approximately 24% of the survey respondents had used cannabis since it was legalized. Ontario had nearly identical numbers (~23%), but Quebec had significantly fewer who indicated they had used cannabis since its legalization (~12%). The fact that Quebec respondents had a nearly 50% lower frequency of cannabis use since legalization could have had effects on their concerns, beliefs and attitudes about both medical and recreational cannabis.

Interestingly, when compared with the rest of Canada, fewer females from Quebec indicated they had used cannabis since legalization. This was a stark difference, where only 1% of females in Quebec, but 20% of females in the rest of Canada, had used cannabis. This disproportionately larger number of female respondents from Ontario who had used cannabis since legalization could have affected perceptions on the safety and efficacy of medical cannabis and could have played a role in the increased comfort in providing this advice when compared with Quebec and the rest of Canada.

The fact that respondents from Quebec were more conservative in their beliefs about the legality of cannabis use is contrasted by their being less concerned over the legal repercussions of dispensing it, as well as being less concerned about the potential legal repercussions of providing advice on medicinal and recreational cannabis. This effect seems to be driven by differences in response by sex. Specifically, females from Quebec were less concerned about potential legal repercussions to dispensing medical cannabis to patients when compared with females from Ontario and from Canada.

Regarding the question of whether cannabis should even be legal, responses from all of Canada indicated that 69% believed cannabis should be legal for medical and recreational use, 29.5% believed it should be available only for medical use and 1.5% believed it should be completely illegal. The current findings suggest that respondents from Ontario were more liberal in their views about the legality of cannabis use compared to Quebec and to the rest of Canada. Furthermore, compared to Ontario, those from Quebec were more likely to think that cannabis should be “illegal for medical and recreational use.” It would have been interesting to examine the role that stigma may have had in differences in response by geographic location, as past research on pharmacists’ perspectives on medical cannabis identified stigma as a major barrier that needed to be mitigated in order for medical cannabis to be successfully rolled out. 11

Another factor that can influence attitudes and beliefs about cannabis use can be the openness to changing one’s opinion when presented with more evidence. In all of Canada, 34.1% of respondents indicated their perceptions towards cannabis had become more positive, 59.5% indicated perceptions were the same and 6.3% indicated that their perceptions had become more negative. It was found that significantly fewer respondents from Quebec indicated that their perceptions of cannabis were more negative when compared to Ontario and to the rest of Canada. This is interesting in the context that fewer from Quebec indicated that they had tried cannabis since legalization, while at the same time, those from Quebec were more likely to be worried that medical or recreational cannabis use may lead to the use of other drugs (i.e., a gateway effect).

When examining how often advice is provided to patients on medical and recreational cannabis, there were no significant associations by geographic location. In all of Canada, ~40% of respondents had never provided advice on medical cannabis and ~50% had never provided advice on recreational cannabis. In all of Canada, ~70% of respondents agreed that medical cannabis should be dispensed only by a licensed pharmacy. This is contrasted by the fact that approximately 20% respondents agreed that they were concerned there may be legal repercussions to dispensing cannabis and providing medical advice to patients.

In all of Canada, approximately 48% agreed they were comfortable providing counselling and answering questions from patients on the safety of medicinal cannabis, and approximately 40% agreed they were comfortable counselling on efficacy. It was found that relative to the rest of Canada, those from Ontario were significantly more likely to be comfortable discussing the safety and efficacy of medical cannabis with patients. When compared with Ontario or the rest of Canada, those from Quebec were significantly less likely to be comfortable discussing safety and efficacy of medical cannabis. Although the current study was not designed to specifically examine the role that the mandatory pharmacy education had on responses from Ontario pharmacists, these results are consistent with a recent study on the knowledge and attitudes of US neurologists, nurses and pharmacists, where health care providers’ education was correlated to more favourable attitudes surrounding cannabis therapy. 8 Our findings are also consistent with those from a recent Canadian study of nearly 800 hospital pharmacists, where two-thirds (64.5%) disagreed with the statement, “I consider myself knowledgeable about marijuana for medical purposes,” and half were uncomfortable with the prospect of providing advice to patients or other health professionals. 12

Examining sex differences, it was found that across all of Canada, males were more comfortable counselling patients on the efficacy of medical cannabis. Specifically, the fraction of male pharmacists who chose “strongly agree” was 71% higher compared to female pharmacists. There were also sex differences by geographic location, where females from Quebec were less comfortable than females from the rest of Canada providing counselling on the safety of medical cannabis. Similarly, females from Quebec were less comfortable counselling on efficacy than females from Ontario.

Taken together, a relationship emerged where the more comfortable one is talking to patients about the safety/efficacy of medical cannabis, the more worried one is over the legal repercussions surrounding dispensing and providing advice on medical cannabis. In this sense, the online training could be said to have helped Ontario pharmacists with their knowledge of safety and efficacy, but the current findings suggest that they are still wary about providing this advice on medicinal cannabis due to potential litigation.

When comparing the indications for whether medical cannabis has a place in adult therapy and child therapy, respondents were more likely to choose that cannabis has a place in child therapy only for seizures. A plausible explanation for this is that there are data on the effectiveness and safety of medical cannabis for seizures, more particularly for drug-refractory childhood epilepsy. 13

Notably for all other indications beside seizures, respondents were less likely to consider cannabis as a therapy for children than for adults. Indeed, there is less evidence to support cannabis for pediatric use, but this is also a broad theme that applies to many pharmacotherapies. 14 The 3 most selected indications for medical cannabis for adults were cancer associated with severe/chronic pain, nausea or severe vomiting, or cachexia or severe wasting and terminal illness. This is consistent with the indications in other studies (cancer, pain, nausea). 15 On the other hand, indications such as autism or posttraumatic stress disorder, for which cannabis is known to be effective, were selected by <10% of pharmacists and students.

The 3 most selected indications for medical cannabis for children were seizures, including those characteristic of epilepsy, cancer associated with severe/chronic pain and nausea or severe vomiting, or cachexia or severe wasting. For children and adolescents, the clinical and ethical trade-offs are more complex than those for adults; the younger the individual, the higher the risk for cannabis dependence or adverse outcomes. 16 The current finding that respondents were less likely to choose that cannabis should be a therapy in children for most indications is not surprising. This suggests that pharmacists and pharmacy students recognize the differential clinical effects and adverse risks of cannabis on various subpopulations and the need for more evidence-based research.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. The survey was exploratory in nature and was not powered to specifically examine differences across all geographic locations or by sex. Therefore, it is important to consider that there were significantly more females than males who responded to the survey for all of Canada (63.1% vs 34.7%), as well as in the provinces of Ontario (57.3% vs 40.9%) and Quebec (74.8% vs 25.2%). The aim of the current study was to examine the demographics of responses for pharmacists as well as pharmacy students, but the study was not powered to examine differences between these 2 groups, or other subgroup analyses that could have been performed (e.g., differences in responses to the question of whether cannabis had been used since legalization). We chose to create a preselected list of clinical indications for medical cannabis therapy for adults and children, which could have influenced our results. Insomnia and anxiety disorders (excluding posttraumatic stress disorder), which are common reasons for self-medicating cannabis use, should be included in further studies that explore our topic. In our study, there may have been overlap between “intractable pain” and “cancer associated with severe chronic pain.”

Conclusions

The current findings suggest that those from Ontario are more liberal in their views about the legality of cannabis use compared with Quebec and to the rest of Canada. Furthermore, relative to Quebec or the rest of Canada, respondents from Ontario were significantly more likely to be comfortable providing counselling and answering questions on medical cannabis use from patients about safety (adverse effects, drug interaction, contraindication) and efficacy (indications, doses, types, routes of administration, medication regimen, monitoring). Overall, males were more comfortable than females counselling patients on the safety and efficacy of medical cannabis. Pharmacists base their practice on a strong body of evidence and may be more worried about cannabis because of their lack of education and practice on the topic. The current results reinforced the perceived need by pharmacists and pharmacy students for targeted education, and future research in education should consider potential gender differences in concerns, beliefs and attitudes surrounding cannabis therapy. ■

Acknowledgments

Saara Manji, Valerie Simoncic, Maelys Giorello and Ashwin Juneja were pharmacy students at CHEO who helped with data collection and the initial development of the survey.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: R.V., J.C., R.D. and T.L. designed and directed the project; R.V., J.C., R.D., T.L., P.M. and H.M. were involved in disseminating the survey; R.V. and J.C. were involved in statistical analysis; R.V., J.C., R.D., T.L., P.M., G.G. and H.M. wrote the article. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Jameason Cameron  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5210-6195

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5210-6195

Our group was interested in assessing the attitude of pharmacists towards cannabis, since it has now been legalized in Canada. With the Ontario College of Pharmacists’ new online training on cannabis being mandated in order for pharmacists to renew their licenses, we wanted to examine any differences between the attitudes of Ontario pharmacists and those in other provinces.

Notre groupe souhaitait évaluer l’attitude des pharmaciens à l’égard du cannabis, qui est désormais légalisé au Canada. La nouvelle formation en ligne sur le cannabis de l’Ordre des pharmaciens de l’Ontario étant obligatoire pour que les pharmaciens puissent renouveler leur licence, nous voulions examiner les différences entre les attitudes des pharmaciens de l’Ontario et ceux des autres provinces.

Contributor Information

Régis Vaillancourt, Department of Pharmacy, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa; Department of Family Medicine, University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine, Ottawa.

Rahim Dhalla, Hybrid Pharm, Ottawa, Ontario.

Piotr Merks, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University, Faculty of Medicine, Warsaw and the Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Collegium, Medicum, Bydgoszcz, Poland.

Taylor Lougheed, Section of Emergency Medicine, Northern Ontario School of Medicine, Sudbury.

Gary Goldfield, Healthy Active Living and Obesity (HALO) Research Group, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa.

Holly Mansell, College of Pharmacy and Nutrition, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

Jameason Cameron, Department of Pharmacy, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa; Department of Family Medicine, University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine, Ottawa.

References

- 1. Government of Canada, Justice Laws. Cannabis Act (SC 2018, c. 16). April 18, 2022. Available: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-24.5/fulltext.html (accessed May 3, 2022).

- 2. Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2015;313(24):2456-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Canadian Pharmacists Association. Medicinal cannabis CE. Ontario College of Pharmacists; 2018. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/advocacy/webinars-continuing-education/medical-cannabis-ce/ (accessed May 3, 2022).

- 4. Tang G, Schwarz J, Lok K, Wilbur K. Cannabis content in Canadian undergraduate pharmacy programs: a national survey. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2020;153(1):27-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Houben RMA, Gijsen A, Peterson J, de Jong PJ, Vlaeyen JWS. Do health care providers’ attitudes towards back pain predict their treatment recommendations? Differential predictive validity of implicit and explicit attitude measures. Pain 2005;114(3):491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davari M, Khorasani E, Tigabu BM. Factors influencing prescribing decisions of physicians: a review. Ethiop J Health Sci 2018;28(6):795-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hwang J, Arneson T, St Peter W. Minnesota pharmacists and medical cannabis: a survey of knowledge, concerns and interest prior to program launch. P T 2016;41(11):716-22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Szaflarski M, McGoldrick P, Currens L, et al. Attitudes and knowledge about cannabis and cannabis-based therapies among US neurologists, nurses and pharmacists. Epilepsy Behav 2020;109:107102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zolotov Y, Metri S, Calabria E, Kogan M. Medical cannabis education among healthcare trainees: a scoping review. Complement Ther Med 2021;58: 102675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McHugh ML. The chi-square test of independence. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2013;23(2):143-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Isaac S, Saini B, Chaar BB. The role of medicinal cannabis in clinical therapy: pharmacists’ perspectives. PLoS One 2016;11(5):e0155113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mitchell F, Gould O, LeBlanc M, Manuel L. Opinions of hospital pharmacists in Canada regarding marijuana for medical purposes. Can J Hosp Pharm 2016;69(2):122-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Perucca E. Cannabinoids in the treatment of epilepsy: hard evidence at last? J Epilepsy Res 2017;7(2):61-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lasky T, Carleton B, Horton DB, et al. Real-world evidence to assess medication safety or effectiveness in children: systematic review. Drugs Real World Outcomes 2020;7(2):97-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Philpot LM, Ebbert JO, Hurt RT. A survey of the attitudes, beliefs and knowledge about medical cannabis among primary care providers. BMC Fam Pract 2019;20(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Englund A, Freeman TP, Murray RM, McGuire P. Can we make cannabis safer? Lancet Psychiatry 2017;4(8):643-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]