Abstract

Introduction

Many biological, psychological and sociocultural factors influence the prevalence of sexual dysfunctions and sexual behavior. The purpose of the study was to evaluate the prevalence of sexual dysfunctions and sexual behaviors.

Material and methods

The study was the third edition of a general population-based, cross sectional survey, evaluating sexual attitude, sexual behaviors within and outside relationships and type of sexual dysfunctions present in the Polish population. The survey consisted of 82 questions, grouped into five blocks that contained open- and closed-ended general questions, inquiries about early sexual contacts, sex life, relationships, sexual behaviors and preferences. A standard questionnaire was used to obtain data on age, education, marital status, religious beliefs, medical history, disabilities and other illnesses. A total of 1054 responders aged from 18 to over 70 years participated in the study. Risk factors and other causes contributing to certain sexual dysfunctions defined in the DSM-5 and in the available literature were analyzed.

Results

In this research, 40% of women and 36.5% of men had at least one sexual dysfunction. Analysis of the total population showed that decreased sexual desire (29.0%), occasional climaxing (28.5%) and anorgasmia (21.0%) were the dysfunctions most frequently reported by women. In men, premature ejaculation (23%) and excessive sexual needs (16.3%) were most prevalent. Both men and women with arousal problems reported significantly more comorbid sexual dysfunctions (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Sexual dysfunctions are highly prevalent in the Polish population. Of note, it is alarming that only very few patients seek professional help when sexual problems occur.

Keywords: sexual dysfunction, sexual activity, sexual behavior

Introduction

Data available on the prevalence of sexual dysfunctions are limited. Those related to sexual interest and desire disorders in men and most aspects of female sexual dysfunction (FSD) receive particularly scarce attention [1]. According to the DSM-5 classification of mental disorders, male sexual dysfunctions include erectile disorder (ED), delayed ejaculation (DE), hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), orgasmic dysfunction and interest/desire and substance/medication-induced sexual disorders [2]. Female sexual dysfunctions constitute the sexual interest/arousal disorder (FSIAD), genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder (GPPPD) and female orgasmic disorder (FOD) [2]. The pathoetiology of sexual dysfunctions involves various factors such as anatomical, biological or physiological. These in turn can be affected by environmental variables [3–17]. Interpersonal, sociocultural factors such as the attitude to sex, religious views, previous sexual experience and education level could also contribute to the development of sexual impairments [3–17].

McCabe et al. performed a literature search regarding the incidence and prevalence of sexual dysfunctions in men and women. They found that the high level of variability across studies was caused by methodologic differences including instruments used to assess the presence of sexual dysfunctions, data collection, nature of samples such as participants’ age, or cultural differences [1]. Results of epidemiological reports show that the prevalence of sexual dysfunctions varies considerably among countries [1, 13].

Burri’s and Spector’s analysis conducted in the United Kingdom showed that 5.8% of women reported symptoms that constituted a diagnosis of FSD and 15.5% reported lifelong FSD. Furthermore, results from an Australian study found that 36% of women reported at least one new sexual difficulty during the previous 12 months. Moreover, in many countries and cultures, sexual dysfunction is taboo, which negatively impacts the quality of life and may often lead to the onset of other psychopathological disturbances [18]. Nicolosi et al. compared the prevalence rates of erectile dysfunction (ED) in Brazil, Italy, and two Asian regions in men between 40 and 70 years of age. The age-adjusted prevalence of moderate or complete ED varied and was 34.5% in Japan, 22.4% in Malaysia, 17.2% in Italy, and 15.5% in Brazil [19]. Moreover, according to the study by Brotto et al. neurobiological factors contributing to sexual function and dysfunction strongly support the impact of psychological, interpersonal, and sociocultural factors and play a significant role in making one vulnerable to developing a sexual concern (e.g., lack of accurate sexual knowledge), in triggering the onset of a sexual difficulty (e.g., exposure to stress), and in maintaining sexual dysfunction over the long term (e.g., ongoing concerns about partner evaluation and associated anxiety) [3]. There is no doubt that sexual problems in both men and women often affect interpersonal functioning and quality of life. It is also of importance that risk factors that drive the onset of sexual dysfunctions may vary depending on the population studied. Therefore, in the present study we wished to present risk factors in regard to the Polish population.

Material and methods

Study design

The study is the third edition of a general population-based, cross sectional survey, evaluating sexual attitude, sexual behaviors and type of sexual dysfunctions within the Polish population. A total of 1054 responders aged from 18 to over 70 years took part in the study. The population was selected based on demographic factors. The required sample size was estimated at 384 individuals with a 95% confidence interval (CI), based on the size of the Polish population in 2015 (37.99 million). Data were collected between December 4 and December 15, 2015 via computer-assisted web interviewing (CAWI). Respondents were members of the Ariadna National Panel, which involves over 100 thousand responders and operates in accordance with the International Code of Ethics (ICC/ESOMAR) and the Inspector General for Personal Data Protection (GIODO). The self-completed, validated survey consisted of 82 questions, grouped into five blocks that contained open- and closed-ended general questions, inquiries about early sexual contacts, sex life, relationships, sexual behaviors and sexual preferences. A standard questionnaire was used to obtain data on age, education, marital status, religious beliefs, medical history, disabilities and other illnesses.

Subjects were divided into five age groups: 18–24, 25–34, 35–49, 50–59 and over 60 years of age (Table I). The sample was representative of all age groups, except for the oldest subgroup over 60 years of age (n = 225) due to insufficient computer and internet skills. However, the oldest population was recruited in the same way as the younger population. Participants were informed about the following issues: i) all information obtained would be used in aggregate; ii) responses were voluntary; iii) participant confidentiality and privacy were protected because no personal identifiers were coded into the interview instruments. Written consent was obtained from all study participants. The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education. There were no exclusion criteria. The dropout rate was 2% and all self-completed questionnaires were analyzed.

Table I.

Sexual problems reported by women depending on age

| Variable | Age [years] | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 | 25–34 | 35–49 | 50–59 | 60–70 | > 70 | ||

| Reduced sexual needs/lack of interest in sex | 19.0% | 32.9% | 25.4% | 31.3% | 33.3% | 37.5% | 29.0% |

| Sex is not pleasurable | 12.1% | 17.6% | 16.1% | 7.8% | 5.1% | 7.5% | 12.6% |

| Vaginismus | 6.9% | 5.9% | 2.5% | 3.1% | 5.1% | 0.0% | 4.0% |

| Pain during intercourse (dyspareunia) | 24.1% | 23.5% | 19.5% | 12.5% | 15.4% | 15.0% | 19.1% |

| Lack of lubrication | 17.2% | 9.4% | 20.3% | 18.8% | 17.9% | 20.0% | 17.1% |

| Rarely climaxing | 29.3% | 41.2% | 28.0% | 18.8% | 17.90% | 27.50% | 28.5% |

| Anorgasmia | 24.1% | 29.4% | 22.0% | 12.5% | 17.90% | 12.50% | 21.0% |

| Climaxing too quickly | 8.6% | 2.4% | 4.2% | 7.8% | 5.1% | 5.0% | 5.2% |

| Excessive sexual needs | 12.1% | 4.7% | 6.8% | 0.0% | 5.1% | 2.5% | 5.4% |

| Other | 3.4% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 2.6% | 2.5% | 1.2% |

Analysis of the data obtained in 2015 was performed in 2018 in regard to risk factors and other possible causes contributing to certain sexual dysfunctions defined in the DSM-5 and in available literature. There is no doubt that the assessment of the possible causes underlying sexual dysfunction demands a holistic approach, where both the patient’s mental and physical health are taken into account. However, the study presented here allowed investigation of only psychological factors and self-reported health status.

For the purpose of this analysis, certain questions were chosen. In the women’s group, the presence of a sexual problem was assessed with the following question: ‘Have you experienced any of the following within the last 12 months: (1) reduced sexual desire/lack of interest in sex, (2) did not find sex pleasurable, (3) rarely reached climax (experienced orgasm), (4) were unable to reach climax (experience orgasm), (5) reached climax (experienced orgasm) too quickly, (5) experienced physical pain during sex, (6) were unable to have vaginal intercourse due to muscle contractions or pain, (7) had trouble becoming adequately lubricated?’ Men were asked to answer whether they experienced: (1) reduced sexual needs/lack of interest in sex, (2) excessive sexual needs, (3) premature ejaculation, (4) premature ejaculation (before penetration), (5) difficulty in achieving an erection, (6) difficulty in maintaining an erection, (7) delayed ejaculation, (8) lack of ejaculation. Respondents experiencing ejaculation issues were additionally asked how long these problems persisted for: (1) 1 week, (2) 1 month, (3) over 3 months, (4) over 6 months, (5) over a year. Some patients reported more than one sexual problem; therefore, one respondent could be included in several groups.

Based on the answers to the questions above, respondents were grouped into subgroups that most closely fitted the DSM-5 classification. The man’s group consisted of individuals struggling with (1) reduced sexual desire/lack of interest in sex, (2) premature ejaculation and premature ejaculation (before penetration), (3) inability to achieve or maintain an erection and inability to achieve ejaculation, (4) delayed ejaculation and lack of ejaculation. Women were allocated to the following groups: (1) reduced sexual needs/lack of interest in sex/sex is not pleasurable, (2) pain during intercourse (dyspareunia) and vaginismus, (3) rarely climaxing and anorgasmia.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22pl software package. Results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05 and 95% confidence interval (CI). A number of possible correlates in the group of respondents who reported sexual problems were investigated. These included age, self-reported measures of general health status, educational attainment, religion, level of satisfaction with current job, time spent at workplace, self-report of a recently diagnosed health problem (within the last 12 months), chronic diseases, and medication taken including hormonal treatment. Respondents also reported how often they thought about sex, had sex, their sexual desires and behaviors and their feelings towards these experiences. Other self-reported measures included relationship experience, emotional and sexual satisfaction, relationship problems as well as violent traumatic experiences in childhood or in adult life such as rape or attempted rape. The menopausal status of women was defined only based on age – the age threshold between pre- and post-menopause was assumed to be 50 years. In Poland the overall median age at natural menopause is 51.25 years. Variation in age at menopause revealed the age range from 45 to 56 years [20, 21]. In addition, the results of the analysis by Stepaniak et al. also showed that median age for women from Krakow is 52 years old [22]. Moreover, as only a few patients (n < 5) out of the whole population (n = 1054) reported taking hormonal medicinal products, this potential confounding factor was not analyzed in our study. Parameters used to describe qualitative data were percentage and number of events, and to characterize quantitative data, average, median, standard deviation, minimal, and maximal values. Additionally, normality test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics were performed. Statistical reasoning was based on statistical significance. It was assumed that the null hypothesis was not true when p < 0.05. Statistical reasoning was based on 95% confidentiality intervals. In order to test the correlation between qualitative variables χ2 test analysis, column proportions test with Bonferroni amendment, analysis of correlation (correlation coefficient was adjusted to the data analyzed), and effect size measurement were performed. The choice of statistical analysis was dependent on the operationalization of variables and the level of their measurement (qualitative or quantitative).

Results

Description of the studied population

The study involved 1054 respondents, 52% of whom were women. In regard to age, the largest group consisted of subjects aged between 35 and 49 years (26.5%). Most respondents (36%) lived in rural areas, while about 13% lived in the largest cities with over 500,000 inhabitants. Over half of the studied population (51.2%) was married, 22.2% were bachelors and single women, whereas 15.1% were living in non-formalized intimate relationships. About 65% of the respondents had children. About 40% of respondents had higher education and 45% had secondary education. In regard to religion, about 81% of the respondents were practicing Catholics. Population characteristics of those that reported at least one sexual problem are presented in supplementary data (Supplementary Tables SI and SII).

Sexual disorders

Among 548 women and 506 men, 224 women and 184 men reported sexual problems. Respondents could report more than one sexual issue. Statistical analysis revealed that in the women’s group, the most frequently reported problems were decreased sexual desire, rare climaxing and anorgasmia, whereas men most often reported premature ejaculation and excessive sexual needs. More detailed data are presented in Tables I and II.

Table II.

Sexual problems reported by men depending on age

| Variable | Age [years] | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 | 25–34 | 35–49 | 50–59 | 60–70 | > 70 | ||

| Reduced sexual needs/lack of interest in sex | 8.0% | 9.8% | 11.2% | 15.9% | 22.2% | 23.5% | 13.0% |

| Excessive sexual needs | 20.0% | 17.1% | 15.9% | 14.5% | 19.4% | 5.9% | 16.3% |

| Premature ejaculation | 26.0% | 14.6% | 18.7% | 29.0% | 41.7% | 17.6% | 23.0% |

| Premature ejaculation (before penetration) | 8.0% | 1.2% | 2.8% | 2.9% | 11.1% | 5.9% | 4.2% |

| Inability to achieve or maintain an erection (Erectile dysfunction during the intercourse) | 2.0% | 2.4% | 1.9% | 7.2% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 4.4% |

| Inability to achieve ejaculation (Erectile dysfunction before achieving orgasm) | 4.0% | 2.4% | 1.9% | 2.9% | 11.1% | 5.9% | 3.6% |

| Delayed ejaculation | 2.0% | 6.1% | 5.6% | 0.0% | 8.3% | 5.9% | 4.4% |

| Lack of ejaculation | 8.0% | 4.9% | 1.9% | 2.9% | 8.3% | 5.9% | 4.4% |

| Other | 0.0% | 2.4% | 1.9% | 0.0% | 2.8% | 11.8% | 1.9% |

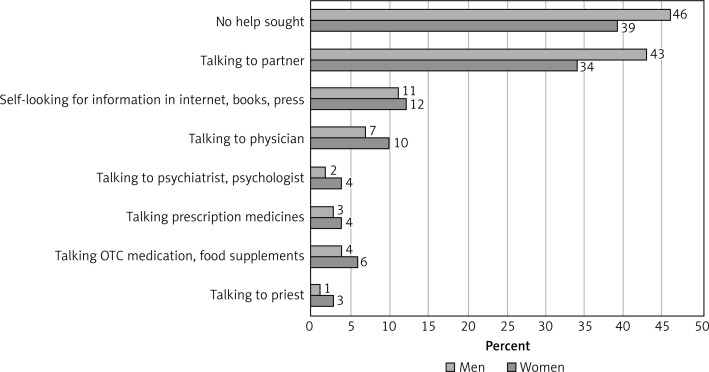

Most responders did not seek professional help upon occurrence of sexual problems. About 46% of men and 34% of women discussed their problems with their partner and only 4% of women and 2% of men visited a psychiatrist or psychologist for counseling (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Strategies undertaken by male and female respondents to tackle sexual problems

Women

Women with reduced sexual needs/lack of interest in sex or sex is not pleasurable

Women in this group claimed to have reduced sexual needs, have lost their interest in sex or that sex was not pleasurable. These two categories of sexual dysfunctions were not dependent either on age or spiritual beliefs. There were also no statistically significant differences in either subgroup between women suffering and those not suffering from chronic diseases. However, it is worth noting that in both subgroups, women more frequently observed changes in their sex life after being diagnosed with a chronic disease (19.4% vs. 5.7%, p < 0.05).

Women who reported reduced sexual needs and stated that sex was not pleasurable were more likely to report lack of lubrication (p < 0.05) and other dysfunctions such as rarely climaxing and anorgasmia (Table III).

Table III.

Factors contributing to sexual dissatisfaction in the reduced sexual needs/lack of interest in sex and sex is not pleasurable subgroups of women

| Oarameter | Reduced sexual needs/lack of interest in sex | Sex is not pleasurable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| Anorgasmia (%) | No | 85.7a | 62,4b | 86.7a | 25.5b |

| Yes | 14.3a | 37.6b | 13.3a | 74.5b | |

| Lack of lubrication (%) | No | 89.2a | 67.5b | 86.4a | 58.8b |

| Yes | 10.8a | 32.5b | 13.6a | 41.2b | |

| Rarely climaxing (%) | No | 83.3a | 42.7b | 79.9a | 13.7b |

| Yes | 16.7a | 57.3b | 20.1a | 86.3b | |

Subset of results for which column proportions did not differ statistically at the level p < 0.05

subset of results for which column proportions differ with statistical significance at the level p < 0.05.

Twenty-four percent of women who reported reduced sexual needs considered themselves significantly less sexually attractive than the women who reported a normal sex drive. Regarding the quality of sex life, both subgroups rarely experienced desire-driven intercourse and significantly less often engaged in any sexual activity. In addition, significantly more women in these two subgroups, than in any other group studied, reported never or rarely having orgasms (women who reported reduced sexual needs/lack of interest in sex 37.6% vs. 14.3%; 57.3% vs. 16.7% respectively; sex is not pleasurable 74.5% vs. 13.3% and 86.3% vs. 20.1% respectively). Moreover, these women significantly less often reported to have, or to have fulfilled, their sexual fantasies (65.2% vs. 39.8%, p < 0.001).

Both subgroups of women who reported reduced sexual needs/lack of interest in sex and sex is not pleasurable reported significantly less emotional (18.0% vs. 48%, p < 0.05 and 12.0% vs. 43.5%, p < 0.05, respectively) and physical contact with their partner, which was also significantly more often not quite satisfying or pleasant as in the rest of the population studied (14.4% vs. 44.0%, p < 0.05 and 12.0% vs. 39.1%, p < 0.05 respectively). Women in both subgroups were less likely to state that the commitment of both partners to the relationship was the same (38.0% vs. 68%, p < 0.05). They were also more likely to describe the frequency of intercourse as too seldom (40.0% vs. 71.0%, p < 0.05).

Pain during intercourse and vaginismus

Women who reported pain during intercourse (dyspareunia) and vaginismus did not significantly differ from each other in terms of age, spiritual beliefs or incidence of chronic diseases. However, more women who reported dyspareunia noticed a change in their sex life after being diagnosed with a chronic disease (21.7% vs. 7.1%, p < 0.01). In regard to sexual attractiveness, significantly more women in both subgroups perceived themselves as definitely not sexually attractive (7.8% vs. 2.8%, p < 0.01). When the quality of sexual life was assessed, women with dyspareunia tended to declare less desire for sexual intercourse (p = 0.074). However, the difference was not statistically significant. It was observed that women who reported dyspareunia had sexual intercourse significantly less often compared to women who did not report pain during intercourse. Only 5.7% of women in this group had sex once in a month (5.7% vs. 25.0%, p < 0.001) or a few times a year (5.4% vs. 25%, p < 0.001).

In both subgroups, women reported less emotional satisfaction and less pleasant physical contact with their partners. Lack of an emotional bond was also more often reported. Moreover, women who reported pain during intercourse significantly more often reported having sexual contacts outside the relationship (35.7% vs. 15.2%, p < 0.001). The partner failing to satisfy their needs was among the most frequent reasons for such behavior (40.0% vs. 8.8%, p < 0.001).

Women in both analyzed groups – with dyspareunia and vaginismus – were more likely to experience single episodes of violence in sexual contacts: 15.6% vs. 7.3%, p < 0.001 and 25.0% vs. 8.2%, p < 0.001 respectively. They also reported using violence during sexual intercourse from time to time (15.6% vs. 7.3%, p < 0.001 and 6.3.% vs. 0.3%, p < 0.001, respectively).

Female orgasmic disorder

Women who reported rare climaxing and anorgasmia were evaluated in this group. The results showed that women in this group significantly more often reported lack of lubrication as the primary cause of their sexual dysfunction: women who reported rarely climaxing 32.2% vs. 11.1%, p < 0.05 and women with anorgasmia 34.1% vs. 12.5%, p < 0.05. Women with orgasmic disorders also considered themselves significantly less attractive than those with no climaxing dysfunctions. Only 5.2% of women who reported rare climaxing felt sexually attractive (5.2% vs. 22.1%, p < 0.01) and 9.4% of women with anorgasmia (9.4% vs. 19.4%, p < 0.01). Moreover, women who reported rare climaxing more often felt definitely not sexually attractive (7.0% vs. 2.4%, p < 0.05) and probably not sexually attractive (24.3% vs. 11.18%). Similar results were obtained in the group with anorgasmia – 8.2% of women felt definitely not attractive (8.2% vs. 2.5%, p < 0.05) and 21.2% probably not attractive (21.2% vs. 13.8%, p < 0.05).

No statistically significant differences were observed in regard to sexual desire between women reporting an orgasmic disorder and the rest of the studied population. However, our results show that women in both subgroups had a tendency to less frequently engage in sexual intercourse.

Women in both subgroups also reported less emotional satisfaction in their relationships, i.e. 15.7% of women who reported rare climaxing were not really satisfied and 6.5% definitely not satisfied with the emotional connection with their partners. Moreover, more women in both subgroups stated that physical contact was not pleasurable. Women who reported suffering from an orgasmic disorder felt that the physical contact with their partner was rather pleasant (25.9% vs. 11.4%, p < 0.01), not really pleasant (11.1% vs. 1.8%, p < 0.01) and definitely not pleasant (13.8% vs. 1.9%, p < 0.01). Among women who reported anorgasmia, their assessment of physical contact quality was also lower in comparison with the rest of the population. Moreover, they less often reported an equal commitment of both partners to the relationship.

Women who reported rare climaxing much more often experienced sexual abuse or violence (2.6% vs. 0.3%, p < 0.01), and at the same time were more eager to use violence in sexual contacts (4.3% vs. 1.0%, p < 0.01). Among women with anorgasmia the differences were not statistically significant.

Men

Men with reduced sexual desire/lack of interest in sex

In this group age, faith or education had no statistically significant impact on the prevalence of the reported sexual dysfunction. However, these men less frequently felt the need to engage in sexual intercourse (46.4% vs. 14.3%, p < 0.01). No statistically significant differences in emotional and physical aspects of the relationship, including satisfaction from sexual intercourse, were observed. The results showed no differences in the occurrence of sexual fantasies as well. However, men with reduced sexual desire/lack of interest in sex were less likely to use and enjoy pornography (9.0% vs. 5.0% p < 0.05). These men were also more likely to have more sexual dysfunctions (p < 0.001) (Table IV).

Table IV.

Factors underlying reduced sexual needs and lack of interest in sex among men

| Variable | Reduced sexual needs/lack of interest in sex | |

|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |

| Inability to achieve or maintain an erection (%) | 3.5a | 10.6b |

| Lack of ejaculation (%) | 2.9a | 14.9b |

| Premature ejaculation (before penetration) (%) | 2.9a | 12.8b |

Subset of results for which column proportions did not differ statistically at the level p < 0.05,

subset of results for which column proportions differ with statistical significance at the level p < 0.05.

Premature ejaculation

The majority of men who reported premature ejaculation were statistically significantly more often devoted Catholics (86.7% vs. 75.5%, p < 0.01).

In terms of attitude towards masturbation, it was observed that men in this group more often reported feelings of guilt, sin (18.7% vs. 6.6%, p < 0.05) or indifference (men with PE 9.3% vs. 3.5%, men with PE before the penetration 21.4% vs. 4.2%) in comparison to the rest of the population. However, there was no significant difference in the frequency of masturbation.

Problems with premature ejaculation did not affect the men’s feelings towards their sexual attractiveness. There were no statistically significant differences between this group and the rest of studied population in terms of emotional bond, physical satisfaction in the relationship or the occurrence of sexual contacts outside the relationship. Men who reported premature ejaculation before penetration reported their intercourse as being too frequent (8.3% vs. 1.3%, p < 0.05).

Premature ejaculation had no impact on assessment of erotic life. There were also no differences observed in regard to the impact that chronic diseases had on sex life of men who reported premature ejaculation.

Erectile disorder

In this group, men who claimed an inability to achieve or maintain an erection or inability to achieve ejaculation were analyzed. Men with inability to achieve or maintain an erection more often reported the occurrence of chronic diseases compared with the rest of the studied population (56.3% vs. 27.2%, p < 0.05). Both subgroups observed a change in their sex life after being diagnosed with a chronic disease: 28.6% of men with inability to achieve or maintain an erection (28.6% vs. 7.6%, p < 0.01) and 25.0% of men with inability to achieve ejaculation (25.0% vs. 8.0%).

Compared with the rest of the population, men who reported an inability to achieve or maintain an erection described the physical contact with their partner as less pleasurable (p < 0.001). In addition, men with an inability to achieve ejaculation more pejoratively described both the emotional (10.0% vs. 1.3%, p < 0.05) and physical aspects (10.0% vs. 0.0%, p < 0.05) of their relationship and more often reported having no romantic bond with their partner (20.0% vs. 1.3%, p < 0.05). They also had significantly less sexual intercourse (a few times a year) and found this sexual activity more sporadic than the rest of the population (14.5% vs. 2.3%, p < 0.05).

In both subgroups of men with erectile disorders, sexual needs and desires were significantly weaker, i.e. a few times a year (12.5% vs. 2.3%, p < 0.05), compared to the rest of the population. However, they did not feel less sexually attractive, and they had significantly more sexual contacts outside the relationship (p < 0.01).

Delayed ejaculation

Men who reported delayed ejaculation or lack of ejaculation were analyzed for their sexual behaviors. No relationship between the occurrence of a chronic disease or change in the quality of sex life after being diagnosed was observed in this group. However, it was observed that men who reported problems with delayed ejaculation or lack of ejaculation more often described the physical contact with their partner as less pleasant compared with the rest of the studied population (7.7% vs. 0.0%, p < 0.01). They also rarely felt the desire to engage in sexual intercourse (30.8% vs. 60.4%, p < 0.001). Moreover, men with delayed ejaculation were more likely to have had sexual contacts outside the relationship (61.5% vs. 25.9%, p < 0.01). They also did not differ in their perception of sexual attractiveness from the rest of the population. No differences in the frequency of either masturbation or feelings towards masturbation were noted between subjects reporting delayed ejaculation and those who did not. The same trend was observed for the attitude towards the use of pornography.

Regarding abuse and sexual violence, the group of men who reported lack of ejaculation more often experienced (6.3% vs. 0.9%, p < 0.05) or used sexual violence than men who had no such dysfunction (18.8% vs. 5.5%, p < 0.05). Among men who reported delayed ejaculation, experiencing or using sexual violence was more frequent, but these results failed to reach statistical significance.

Hypersexuality

Both men and women who reported hypersexuality were analyzed for their sexual behavior. The presence of a chronic disease had no significant influence on the respondents’ sex life quality before and after diagnosis. Moreover, no statistically significant differences were observed in their perception of sexual attractiveness compared to the rest of the studied population.

Among women, 4.5% and 18.2% reported experiencing sexual desire a few times a day (4.5% vs. 0.3%, p > 0.05) or everyday (18.2% vs. 6.5%, p < 0.01), respectively. Among men, 10.2% reported experiencing desire surges a few times a day (10.2% vs. 4.6%, p < 0.05), whereas 33.9% of men experienced them everyday (33.9% vs. 15.6%, p < 0.001). However, no differences were observed in regard to the frequency of intercourse and climaxing. Both men and women described the frequency of their sexual contacts as too low (women: 54.5% vs. 24.6%; men: 69.5% vs. 30.8%, p < 0.001).

Only the men’s group reported the emotional and physical contact with their partners as being less satisfying and pleasant (p < 0.01). Moreover, they significantly more often reported that they are more committed to the relationship than their partners (p < 0.01).

Women with hypersexuality reported having more sexual contacts outside the relationship (38.9% vs. 14.9%, p < 0.01) and, similarly to women with normal sexual drive, mentioned monotony as the primary cause for such behavior. Interestingly, men with hypersexuality did not engage in sexual contacts outside the relationship more often than men who did not report excessive sexual drive. However, more men with hypersexuality reported monotony in their relationship (41.2% vs. 13.7%, p < 0.001).

No significant relationship was observed between excessive sexual needs and abuse/violence experienced in sexual contacts in both men and women. In regard to using violence in sexual contacts, differences were observed only in the women’s group, where 9.1% of women reported using violence during intercourse from time to time (9.1% vs. 1.6%, p < 0.01).

Discussion

In the study presented herein, we examined a number of factors that could be associated with sexual problems in men and women in the Polish population. Data were obtained at the end of 2015 and main study outcomes were presented in 2017. However, the analysis presented in this article was performed in 2018. Overall, 40% of women and 36.5% of men had at least one sexual dysfunction. It is worth emphasizing that all dysfunctions were self-reported. It needs to be outlined that the study has several limitations. First of all, we could not confirm any of the patient’s medical conditions or verify their medical history due to the study design. Data obtained were based on the patients’ answers only. We cannot exclude the possibility that our data were affected by reporting bias given the sensitive nature of the questions. Moreover, owing to lower computer and internet skills among elderly respondents (over 60 years of age), the results obtained from this group can hardly be extrapolated to the overall population. Dunne et al. observed that surveys of sexual behavior may overestimate sexual liberalism, activity, and prevalence of sexual dysfunctions. However, this bias does not seriously compromise population estimates as judged by the pattern of effect sizes [23]. In addition, it would be erroneous to assume a direct causative relationship between sexual problems and some of the variables found in this study, e.g. some of the factors could be the outcome of the dysfunction reported. Despite these limitations, our analysis represents the most recent data regarding the prevalence of sexual dysfunctions in Poland.

Female sexual dysfunction can severely impair a woman’s quality of life, self-esteem and relationships [23]. In this report 17.1% of women reported lubrication problems. Laumann et al. and Richters et al. determined that self-reported levels of lubrication impairments were present in 21% to 28% of sexually active women [24, 25]. Safarinejad found that lack of lubrication was present in 34% of Iranian women [26], whereas Öberg et al. reported that 49% of Swedish women aged from 18 to 65 years had mild (sporadically occurring) lubrication insufficiency [27].

We found that women with arousal problems reported significantly more sexual dysfunctions. Women in this group felt less attractive and reported more relationship problems relating to both emotional and physical aspects. We found that age, sociodemographic factors or chronic diseases did not contribute to the perception of physical attractiveness in these women. However, they noticed a change in regard to their sexual problems after being diagnosed with a chronic disease.

The prevalence of orgasmic dysfunction in women varies considerably in epidemiologic reports, ranging from 10% in Northern Europe to 34% in Southeast Asia [1, 28]. FOD is complex and has no single causative factor. Relationship issues such as abuse, poor communication and misunderstandings or differences regarding sexual intimacy and satisfaction can also lead to sexual problems. Women experiencing extreme stress from a variety of life circumstances can also experience problems in reaching orgasm. Personal vulnerabilities such as a history of sexual abuse, negative body image, anxiety or depression can also contribute to FOD [2]. In our study, the prevalence of FOD was between 21 and 28.5% and was associated with arousal disorder (i.e. lack of lubrication) in 65% of responders. It had a major impact on the women’s self-esteem and their relationships regardless of age or sociodemographic factors. Women who reported rare climaxing much more often experienced abuse or violence and admitted using violence in sexual contacts.

Anatomical abnormalities or inflammation in the vaginal muscles or an injury to the vulva could serve as causative factors for genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder (GPPPD) referred to as dyspareunia and vaginismus. Additionally, it may result from a psychologically traumatic past experience such as early-life abuse or domestic violence. Psychological factors such as fear of the pain worsening or loss of self-confidence may also contribute to this condition [11]. The prevalence of dyspareunia and vaginismus in our sample population studied was 19.1% and 4%, respectively. In other available studies, dyspareunia was present in as many as 14% to 27% of women [1]. Our findings confirm that dyspareunia had a significant negative impact on the women’s self-esteem and their relationship, regardless of sociodemographic factors. However, women who experienced pain during intercourse were also more likely to have experienced or used abuse or violence.

Desire and arousal disorders were a concern in 13% of men and seemed to intensify with age. It could be observed that men with reduced sexual desire/lack of interest in sex were more likely to have more sexual dysfunctions (p < 0.001). McCabe et al. found that in different geographic locations and in different age groups, the prevalence of decreased sexual interest or desire was reported in 15% to 25% of men up to approximately 60 years of age. However, this dysfunction did not have any noticeable impact on their relationships and self- assessment in regard to sexual attractiveness. It seems that some desire/arousal disorders could be the effect of sexual mismatch, because all groups of men declaring desire and arousal dysfunctions had sexual fantasies.

The prevalence of premature ejaculation varies from 8% to 30% in all age groups [1]. In this report, the prevalence of self-reported PE equaled 23% and did not depend on age, sociodemographic factors or any existing chronic diseases. Men who reported PE were more often practicing Catholics in comparison with the rest of the studied population. Moreover, PE did not affect the men’s self-esteem or their relationships.

In regard to erectile dysfunction (ED), 4.4% of men reported an inability to achieve or maintain an erection and 3.6% of men claimed they were unable to achieve ejaculation. A successful diagnosis of ED is often preceded by careful exclusion of possible anatomical pathologies. Among the major predictors of ED are diabetes mellitus, vascular diseases, hypertension and decreased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels. Treatment with anti-diabetic and cardiovascular medications constitutes yet another important risk factor for the development of ED [13]. It is well documented that the prevalence of ED increases with age [2]. In our report, 7.2% of men in their 50s were dysfunctional in regard to maintaining an erection and 2.9% in regard to achieving ejaculation. For men over 60 years of age, these parameters were 16.7% and 11.1%, respectively. Other studies estimate that the prevalence of ED is 1% to 10% in individuals younger than 40 years of age [1]. In subjects aged from 40 to 49 years, the prevalence of ED ranges from 2% to 15%. The 50- to 59-year-old group showed the greatest range of reported ED prevalence rates. The average fell between rates for men in their 40s and men in their 60s. Most studies show ED prevalence rates from 20% to 40% in subjects aged from 60 to 69 years [1, 27]. In our study, the occurrence of ED increased with age, but was not dependent on socioeconomic factors. Men with ED significantly more often suffered from chronic diseases and observed a change in their sex life after being diagnosed with one.

Delayed or absent ejaculation (DE) is a disorder associated with a variety of neurological conditions or surgical interventions (e.g. multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, surgical prostatectomy). Prevalence rates for DE vary from 1% to 10% [1]. This condition can also be the consequence of using sympatholytic or neuroleptic drugs [13]. Moreover, psychological and interpersonal factors such as performance anxiety, conditioning factors, fear of impregnation, and lack of desire or arousal have also been implicated as risk factors in the development of DE [13–15]. Irrespective of the contribution the organic etiology has in the development of DE, this condition is exacerbated by insufficient stimulation or excessive sexual expectations displayed by the partner, for instance not properly duplicated masturbation technique by the partner [16]. Moreover, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that excessive exposure to alternative sexual stimuli such as pornography or engaging in idiosyncratic masturbation may produce sexual dysfunction as a consequence of desensitization [16, 17]. In our study, delayed ejaculation or lack of ejaculation concerned 4.4% of men. As with other dysfunctions, a negative impact on their relationship was observed. Sexual mismatch also could be a contributing factor, because men in this group thought that the frequency of sexual intercourse was inadequate and also had more sexual contacts outside the relationship. It is speculated that the prevalence of DE or anejaculation in elderly men, many of whom are no longer sexually active, could be much higher [1]. However, we did not observe such a tendency in our investigation. It could be due to the fact that elderly respondents were not internet savvy, and this could have accounted for the insignificant outcome.

In conclusion, sexual dysfunctions have an impact on the quality of life of males and females, their self-esteem, relationship quality and sex life. Despite the study limitations, we conclude that data regarding the prevalence of sexual dysfunctions in our studied population do not differ significantly from other studies. The disturbing fact is that most of the respondents do not seek professional help after noting problems in their sex life.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.McCabe MP, Sharlip ID, Lewis R, et al. Incidence and prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women and men: a consensus statement from the Fourth International Consultation on Sexual Medicine 2015. J Sex Med 2016; 13: 144-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brotto L, Atallah S, Johnson-Agbakwu C, et al. Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. J Sex Med 2016; 13: 538-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayes RD, Dennerstein L, Bennett CM, Fairley CK. What is the “true” prevalence of female sexual dysfunctions and does the way we assess these conditions have an impact? J Sex Med 2008; 5: 777-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schnarch D. Passionate Marriage: Keeping Love and Intimacy Alive in Committed Relationship. Owl Books, New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris JM, Cherkas LF, Kato BS, Heiman JR, Spector TD. Normal variations in personality are associated with coital orgasmic infrequency in heterosexual women: a population based study. J Sex Med 2008; 5: 1177-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson AL, Purdon C. Non-erotic thoughts, attentional focus, and sexual problems in a community sample. Arch Sex Behav 2011; 40: 395-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laan E, Everaerd W, Van-Aanhold M, et al. Performance demand and sexual arousal in women. Behav Res Ther 1993; 31: 25-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rellini AH, Meston CM. Sexual self-schemas, sexual dysfunction, and the sexual responses of women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Arch Sex Behav 2011; 40: 351-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kring AM, Johnson SL, Davison GC, Neale JM. Sexual disorders. In: Abnormal Psychology. 12th edn. Kring A, Johnson SL, Davidson GC, Neale JM (eds). John Wiley and Sons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verit FF, Verit A, Yeni E. The prevalence of sexual dysfunction and associated risk factors in women with chronic pelvic pain: a cross-sectional study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2006; 274: 297-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khera M, Goldstein I. Erectile dysfunction. BMJ Clin Evid 2011; 2011; pii: 1803. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen RC. Prevalence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction in men and women. Curr Psych Rep 2000; 2: 189-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segraves RT. Effects of psychotropic drugs on human erection and ejaculation. Arch Gen Psych 1989; 46: 275-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apfelbm B. Retarded ejaculation: a much-misunderstood syndrome. In: Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy: Update for the 1990s. Leiblum SR, Rosen RC (eds). Guilford Press, New York: 1989; 168-206. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perelman MA. Psychosexual therapy for delayed ejaculation based on the sexual tipping point model. Transl Androl Urol 2016; 5: 563-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brand M, Laier C, Pawlikowski M, Schächtle U, Schöler T, Altstötter-Gleich C. Watching pornographic pictures on the Internet: role of sexual arousal ratings and psychological–psychiatric symptoms for using Internet sex sites excessively. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2011; 14: 371-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burri A, Spector T. Recent and lifelong sexual dysfunction in a female UK population sample: prevalence and risk factors. J Sex Med 2011; 8: 2420-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicolosi A, Moreira ED Jr, Shirai M, Tambi MI, Glasser DB. Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction in four countries: cross-national study of the prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction. Urology 2003; 61: 201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaczmarek M. The timing of natural menopause in Poland and associated factors. Maturitas 2007; 57: 139-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaczmarek M. Variation in age at natural menopause among Polish women in relation to biological social factors. In: Ageing Related Problems in Past and Present Populations. Vol. 5. Bodzsár EB, Susanne C. Plantin Publ. & Press Ltd, Budapest, 2008; 119-41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stepaniak U, Szafraniec K, Kubinova R, et al. Age at natural menopause in three central and eastern European urban populations: the HAPIEE study. Maturitas 2013; 75: 87-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunne MP, Bailey JM, Kirk KM, Martin NG. The subtlety of sex atypicality. Arch Sex Behav 2000; 29: 549-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999; 281: 537-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richters J, Grulich AE, de Visser RO, et al. Sex in Australia: sexual difficulties in a representative sample of adults. Aust N Z J Public Health 2003; 27: 164-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Safarinejad MR. Female sexual dysfunction in a population-based study in Iran: prevalence and associated risk factors. Int J Impot Res 2006; 18: 382-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Öberg K, Fugl-Meyer AR, Sjögren Fugl-Meyer K. On categorization and quantification of women’s sexual dysfunction. An epidemiological approach. Int J Impot Res 2004; 16: 261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicolosi A, Laumann EO, Glasser DB, Moreira ED Jr, Paik A, Gingell C. Sexual behavior and sexual dysfunctions after age 40: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Urology 2004; 64: 991-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.