Abstract

Background

Communication about end of life (EoL) and EoL care is critically important for providing quality care as people approach death. Such communication is often complex and involves many people (patients, family members, carers, health professionals). How best to communicate with people in the period approaching death is not known, but is an important question for quality of care at EoL worldwide. This review fills a gap in the evidence on interpersonal communication (between people and health professionals) in the last year of life, focusing on interventions to improve interpersonal communication and patient, family member and carer outcomes.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions designed to improve verbal interpersonal communication about EoL care between health practitioners and people affected by EoL.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL from inception to July 2018, without language or date restrictions. We contacted authors of included studies and experts and searched reference lists to identify relevant papers. We searched grey literature sources, conference proceedings, and clinical trials registries in September 2019. Database searches were re‐run in June 2021 and potentially relevant studies listed as awaiting classification or ongoing.

Selection criteria

This review assessed the effects of interventions, evaluated in randomised and quasi‐randomised trials, intended to enhance interpersonal communication about EoL care between patients expected to die within 12 months, their family members and carers, and health practitioners involved in their care. Patients of any age from birth, in any setting or care context (e.g. acute catastrophic injury, chronic illness), and all health professionals involved in their care were eligible. All communication interventions were eligible, as long as they included interpersonal interaction(s) between patients and family members or carers and health professionals. Interventions could be simple or complex, with one or more communication aims (e.g. to inform, skill, engage, support). Effects were sought on outcomes for patients, family and carers, health professionals and health systems, including adverse (unintended) effects.

To ensure this review's focus was maintained on interpersonal communication in the last 12 months of life, we excluded studies that addressed specific decisions, shared or otherwise, and the tools involved in such decision‐making. We also excluded studies focused on advance care planning (ACP) reporting ACP uptake or completion as the primary outcome. Finally, we excluded studies of communication skills training for health professionals unless patient outcomes were reported as primary outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

Standard Cochrane methods were used, including dual review author study selection, data extraction and quality assessment of the included studies.

Main results

Eight trials were included. All assessed intervention effects compared with usual care. Certainty of the evidence was low or very low. All outcomes were downgraded for indirectness based on the review’s purpose, and many were downgraded for imprecision and/or inconsistency. Certainty was not commonly downgraded for methodological limitations.

A summary of the review's findings is as follows.

Knowledge and understanding (four studies, low‐certainty evidence; one study without usable data): interventions to improve communication (e.g. question prompt list, with or without patient and physician training) may have little or no effect on knowledge of illness and prognosis, or information needs and preferences, although studies were small and measures used varied across trials.

Evaluation of the communication (six studies measuring several constructs (communication quality, patient‐centredness, involvement preferences, doctor‐patient relationship, satisfaction with consultation), most low‐certainty evidence): across constructs there may be minimal or no effects of interventions to improve EoL communication, and there is uncertainty about effects of interventions such as a patient‐specific feedback sheet on quality of communication.

Discussions of EoL or EoL care (six studies measuring selected outcomes, low‐ or very low‐certainty evidence): a family conference intervention may increase duration of EoL discussions in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting, while use of a structured serious illness conversation guide may lead to earlier discussions of EoL and EoL care (each assessed by one study). We are uncertain about effects on occurrence of discussions and question asking in consultations, and there may be little or no effect on content of communication in consultations.

Adverse outcomes or unintended effects (limited evidence): there is insufficient evidence to determine whether there are adverse outcomes associated with communication interventions (e.g. question prompt list, family conference, structured discussions) for EoL and EoL care. Patient and/or carer anxiety was reported by three studies, but judged as confounded. No other unintended consequences, or worsening of desired outcomes, were reported.

Patient/carer quality of life (four studies, low‐certainty evidence; two without useable data): interventions to improve communication may have little or no effect on quality of life.

Health practitioner outcomes (three studies, low‐certainty evidence; two without usable data): interventions to improve communication may have little or no effect on health practitioner outcomes (satisfaction with communication during consultation; one study); effects on other outcomes (knowledge, preparedness to communicate) are unknown.

Health systems impacts: communication interventions (e.g. structured EoL conversations) may have little or no effect on carer or clinician ratings of quality of EoL care (satisfaction with care, symptom management, comfort assessment, quality of care) (three studies, low‐certainty evidence), or on patients' self‐rated care and illness, or numbers of care goals met (one study, low‐certainty evidence). Communication interventions (e.g. question prompt list alone or with nurse‐led communication skills training) may slightly increase mean consultation length (two studies), but other health service impacts (e.g. hospital admissions) are unclear.

Authors' conclusions

Findings of this review are inconclusive for practice. Future research might contribute meaningfully by seeking to fill gaps for populations not yet studied in trials; and to develop responsive outcome measures with which to better assess the effects of communication on the range of people involved in EoL communication episodes. Mixed methods and/or qualitative research may contribute usefully to better understand the complex interplay between different parties involved in communication, and to inform development of more effective interventions and appropriate outcome measures. Co‐design of such interventions and outcomes, involving the full range of people affected by EoL communication and care, should be a key underpinning principle for future research in this area.

Keywords: Humans, Anxiety, Communication, Physician-Patient Relations, Quality of Life, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Terminal Care

Plain language summary

How can communication about the end of life and care in the last 12 months of life be improved?

Key messages

We did not find enough good quality evidence to be able to say which ways of communicating about end of life (EoL) are best for the people involved. One study of a family conference intervention found that communication interventions might increase the length of EoL discussions between families and health professionals in some situations, and one other found that an intervention which used a structured conversation guide might lead to earlier discussions between patients, carers, and health professionals about EoL and EoL care. We did not find any evidence of harmful or negative effects of communication interventions, and we are uncertain about effects on outcomes like knowledge or quality of EoL care.

Why is communication at the end of life important?

When people are in the last year of their life, it is important that they receive high‐quality care (refer to ACSQHC 2015 and 2015b references for more on care at end of life). Communication about EoL is a critical part of such care. It helps patients and their families and carers to understand what is happening, to know what to expect and what their options are, to ask questions and receive support, and to be involved in decisions and planning as much as they would like to be. Communication about EoL is not always done well and this can have negative effects. Understanding how to improve such communication between the different people involved in care at EoL (patients, family members, carers, health professionals) is important to help ensure that people receive the best possible care in the time leading up to death.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out which ways of communicating with patients and carers might be best for improving people’s knowledge about the EoL (e.g. what to expect, treatment options).

What people thought about the communication (e.g. satisfaction, communication quality, how involved they were and wanted to be in consultations). Discussions about end of life (e.g. how often these happened, and when).

We also wanted to find out if communication interventions might increase unwanted or harmful effects, like fear or distress.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that looked at communication interventions compared with usual care (care that is provided routinely or as the standard way of treating people), or comparing one type of communication (e.g. providing information) with another (e.g. providing information together with support), in people of all ages from birth onwards and who were expected to die within 12 months. We summarised the results of the included studies and rated our confidence in the evidence based on factors such as study size, study methods, and the people studied by the trials.

To ensure this review's focus was maintained on interpersonal communication in the last 12 months of life, we excluded studies that addressed specific decisions, shared or otherwise, and the tools involved in such decision‐making. We also excluded studies focused on advance care planning (ACP) reporting ACP uptake or completion as the primary outcome. Finally, we excluded studies of communication skills training for health professionals unless patient outcomes were reported as primary outcomes.

What did we find?

We found eight studies that compared the effects of communication interventions for people at EoL with usual care. Interventions were varied and ranged from simple approaches like a list to help patients and carers ask questions in consultations, through to complex structured conversation interventions to engage patients and carers in discussions about EoL and the care they wished to receive.

We found that a family conference intervention may increase the length of EoL discussions in some situations, and a structured serious illness conversation guide might lead to earlier discussions between patients, carers and health professionals about EoL and EoL care.

We also found there may be little effect of communication interventions on knowledge, on what people thought about the communication (e.g. quality of communication, how involved in the discussion they would like to be) or on outcomes like numbers of questions asked by patients in consultations with their doctors. We did not find any evidence of harmful or negative effects of the interventions, but the studies were mostly small and not designed primarily to identify these.

There may also be little effect on the other outcomes we looked for, like quality of life, quality of EoL care, or numbers of care goals met. In other cases, we are unsure because there was little or no evidence available (e.g. health professional outcomes like knowledge or confidence to communicate, or health service use e.g. hospital admissions).

What are the limitations of the evidence?

We have very little confidence in the evidence: included studies only looked at communication for older adults in high‐income countries, whereas the review looked for evidence across the whole lifespan and irrespective of country and setting. Additionally, included studies often studied small numbers of people.

How up to date is this evidence?

The evidence is up to date to July 2018.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings .

| Communication intervention compared with usual care for end of life care | |||

|

Patient or population: people approaching the end of life (within 12 months), their family members and/or carers Settings: any (residential care, hospital (inpatient and outpatient units) and community‐based clinics, palliative care services) Intervention: interventions to improve communication about EoL and/or EoL care Comparison: usual care | |||

| Outcomes | Intervention effects | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Patient, family and/or carer outcomes | |||

| Knowledge and understanding Variable scales: information (amount and type) needs/preferences; discordance between patient and physician survival and curability estimates Timing: immediately to 1 month post‐consultation |

Overall, interventions to improve communication may have little or no effect on measures of knowledge of illness and prognosis, or information needs and preferences In 1 study (303 participants), discordant estimates of 2‐year survival between patients and doctors (intervention 59% versus usual care 62%) and curability (intervention 39% versus usual care 44%) were similar between groups (Epstein 2017). Another (79 participants) reported similar proportions of patients had their preferences for amount of information met or exceeded across intervention and usual care groups, but that type of information was met or exceeded more often in the intervention group (93% versus 80%) (Walczak 2017). 1 final study (170 participants) reported no differences in patients’ unmet information needs overall (Clayton 2007) |

552 (3 studies)c | ⊕⊕⊝⊝

lowa,b |

| Evaluation of the communication: different constructs (perceptions of communication quality; patient‐centredness of communication; involvement preferences; doctor‐patient relationship measures) Timing: immediately post‐consultation to 18 weeks post‐consultation |

Across constructs (patient‐centredness, involvement preferences, doctor‐patient relationship, satisfaction with consultation), there may be minimal or no effects of interventions to improve communication about EoL and EoL care (Agar 2017; Bernacki 2019; Clayton 2007; Epstein 2017; Walczak 2017), and uncertaintye about effects on quality of communication (Au 2012) |

6 studiesf | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb,d |

| Discussions of EoL/EoL care: discussion timing and length EMR review post‐death Timing: at time of family conference (intervention) in ICU; post‐death |

The intervention may lead to longer and earlier discussions of EoL and EoL care, compared with usual care, but each result is based on a single study 1 study (108 participants) reported comparative data: median family conference intervention duration was 30 minutes (IQR 19 to 45 minutes) versus usual care (median 20 minutes, IQR 15 to 30 minutes) (Lautrette 2007) 1 study (376 participants) reported that the first documented Serious Illness Conversation happened earlier among intervention group participants (median 143 days prior to death (IQR 71 to 325) than usual care (71 days, IQR 33 to 166) (Bernacki 2019) |

484 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb,d |

| Discussions of EoL/EoL care: discussion occurrence EMR review post‐death; coding of consultations; self‐reported occurrence Timing: immediately, 1 or 2 weeks post‐consultation; after death |

Overall, we are uncertain about the effects of interventions to improve discussions about EoL care 2 studies indicated that the intervention increased the occurrence of EoL discussions, compared with usual care (RR 1.96, 95% CI 1.61 to 2.39; 2 trials, 537 participants); the others indicated little or no effect of the intervention on mean total numbers of patient questions in consultations (MD 1.58, 95% CI ‐1.82 to 4.98; 2 trials, 249 participants) |

786 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝

very lowb,g,h |

| Adverse (unintended) outcomes |

There is insufficient evidence to determine whether adverse (unintended) outcomes are associated with communication interventions. Patient and/or carer anxiety was reported (3 studies), but was judged as confounded, and no other unintended consequences, or worsening of desired outcomes, were reported | ‐ | ‐ |

| CI: confidence interval; EMR: electronic medical record; EoL: end of life; ICU: intensive care unit; IQR: interquartile range; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | |||

aDowngraded (‐1) due to inconsistency (different outcome measures and concepts assessed across studies). bDowngraded (‐1) for indirectness (all participants were older patients with advanced cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or both, and results may not apply to other populations nearing EoL). c1 further study (Lautrette 2007, 108 participants) conducted in an ICU setting did not report useable data. dDowngraded (‐1) due to imprecision (results are from a single study and/or a small number of participants). eQuality of communication also downgraded (‐1) due to methodological limitations (sequence generation rated at unclear risk of bias). fMost of these outcomes under this broad construct were assessed by only 1 study; doctor‐patient relationship was reported by 3 studies (238 participants); and numbers of participants were consistently small across all outcome measures. gDowngraded (‐1) for inconsistency (2 of 4 studies indicated that the intervention had no effect, with residual variation despite similar populations and interventions). hDowngraded (‐1) for methodological limitations (the largest study rated as at unclear risk of bias on sequence generation).

Background

Description of the condition

Discussion about end of life (EoL) between health practitioners and affected people can be a confronting experience for all parties involved. According to the Australian Medical Association, "Death, dying and bereavement are all an integral part of life; however, reflecting on, and discussing death, can be profoundly confronting and difficult. Open and frank discussion of death and dying including EoL care options, approach to futile treatment, caring and bereavement should be encouraged within the profession and in the wider community" (AMA 2014). EoL and EoL care can be defined in many different ways. For this review, we have adopted the following definitions, developed as part of a national (Australian) consensus statement on end of life care.

End of life: "the period when a patient is living with, and impaired by, a fatal condition, even if the trajectory is ambiguous or unknown. This period may be years in the case of patients with chronic or malignant disease, or very brief in the case of patients who suffer acute and unexpected illnesses or events, such as sepsis, stroke or trauma" (ACSQHC 2015, page 33).

-

End of life care: "includes physical, spiritual and psychosocial assessment, and care and treatment delivered by health professionals and ancillary staff. It also includes support of families and carers, and care of the patient’s body after their death. People are 'approaching the end of life' when they are likely to die within the next 12 months. This includes people whose death is imminent (expected within a few hours or days) and those with:

advanced, progressive, incurable conditions;

general frailty and co‐existing conditions that mean that they are expected to die within 12 months;

existing conditions, if they are at risk of dying from a sudden acute crisis in their condition; and

life‐threatening acute conditions caused by sudden catastrophic events" (ACSQHC 2015, page 33).

Taken together, the above definitions show that the EoL period may be one of prognostic uncertainty and highly variable in duration. This review acknowledges this uncertainty and the difficulties associated with defining this period. When the selection criteria for this review were developed, the definition given by the above statement (i.e. people are approaching EoL when they are expected to die within 12 months) was the most recent available definition for Australian audiences and so was adopted as a working definition to define the scope of the review.

People involved in communication with health practitioners about EoL and EoL care may include the person at EoL and the family or carers of that person (Hjelmfors 2020; Wolfe 2020). Each of these people may have an important role in discussions about EoL care. For the purpose of this review, we needed to define these different people in a way that is not ambiguous, given the multiplicity of terms that are used in different health systems for all parties. Further, although the term 'patient' is not always suitable for someone who may often not be in a patient role, we needed to distinguish the person at EoL from that person's family member or carer. We therefore define affected people as follows.

Patient: identified as "the primary recipient of care" (ACSQHC 2015, page 34). In many health systems and countries, terms other than 'patient' are preferred. However, in this review we use this term to distinguish clearly between people who are approaching the end of their life, or dying (and to whom discussions about prognosis, treatment, and care relate directly), and people to whom these discussions relate indirectly (i.e. discussions about EoL and EoL care related to a family member or person in whose care they are involved).

Family: this review takes the broadest possible view of family members, considered to represent "those who are closest to the patient in knowledge, care and affection. This may include the biological family, the family of acquisition (related by marriage or contract), and the family and friends of choice" (ACSQHC 2015, page 33). It also includes First Nations definitions of family within the wider culture, such as those encompassed by the concept of kinship care (Palliative Care Australia 2016).

Carer: "a person who provides personal care, support and assistance to another individual who needs it because they have a disability, medical condition (including a terminal or chronic illness) or mental illness, or they are frail and aged. An individual is not a carer merely because they are a spouse, de facto partner, parent, child, other relative or guardian of an individual, or live with an individual who requires care" (ACSQHC 2015, page 32).

The focus of this review is interpersonal interactions occurring between patients, family, carers, and health practitioners at the EoL.

EoL discussions are often placed within the context of palliative care. The "WHO [World Health Organization] identified that, globally, palliative care needs are very high, with an estimated 20 million people needing end‐of‐life care each year" (AIHW 2014, page 2). This enormous demand exists across countries and healthcare systems (World Wide Palliative Care Alliance 2014), yet palliative care is only one of the contexts in which good communication about EoL care is essential.

Internationally, a large body of research has documented difficulties in EoL communication between healthcare professionals and people affected by EoL (i.e. patients, their families, and carers) (Anderson 2019; Clayton 2007a; Fawole 2012; Fujimori 2020; IoM 2014; NICE 2017; Walczak 2016). These difficulties include failure to communicate adequately with the person who is dying about his or her prognosis (Barnes 2006; Brighton 2016; Fawole 2012; Gott 2009; NICE 2017), or to provide understandable information on what the future holds, and decisions that the person and family members and carers may need to make (Alsakson 2012; Anselm 2005; Barnes 2012; Gutierrez 2012; NICE 2019; Selman 2007). It is also documented that patients receiving EoL care, or those closest to them, may not be given the opportunity to ask questions or to check their understanding of information that has been provided (Alsakson 2012; Clayton 2007a; Gutierrez 2012; Hjelmfors 2020). People often have misunderstandings about their prognosis and goals of treatment in the EoL period (Anderson 2019; Clayton 2007a; ; Gattellari 1999; Thode 2020; Weeks 1998). Misunderstandings may also arise from conflicting information given by multiple practitioners involved in the patient's care. Additionally, the patient and family members or carers may have their own questions about EoL care but may be unaware of how or whom they should approach to find answers to these questions (Alsakson 2012; Anselm 2005; Gutierrez 2012; NICE 2017).

Communication problems have significant potential to negatively impact the person who is dying and family members or carers. Communication problems may contribute to loss of trust in health practitioners (Clayton 2007a; NICE 2017), poorer quality of life and satisfaction, psychological harms, and avoidable distress (Chochinov 2000; Fawole 2012; Fujimori 2020; NICE 2017; Schofield 2003; Selman 2007; Wright 2008). These negative outcomes reflect poorly on the ability of existing healthcare systems to effectively deliver patient‐centred, responsive care during EoL (Anderson 2019; IoM 2014; NICE 2017; NICE 2019). In comparison, high‐quality communication about EoL is associated with improved quality of life and less aggressive approaches to treatment, as well as better outcomes for carers related to bereavement (Brighton 2016; Detering 2010; Heyland 2009; Wright 2008; Zhang 2009).

Communicating effectively about EoL is a difficult and complex task that is further complicated by uncertainty about the trajectory of the last stages of a person's life and the associated prognosis (Barnes 2012; Brighton 2016; Fawole 2012). Good communication remains the primary means of preparing the patient and affected people for the last months, weeks, and days of life (Anderson 2019; Fawole 2012). This review focuses on general communication between health practitioners and people affected by EoL ‐ not specifically on communication involving use of specific tools to achieve structured decision‐making (such as communication or discussion in which participants use a highly structured checklist to develop an advance care plan). Such specific, structured decision‐making approaches were therefore excluded. With focus on general communication, this review is able to evaluate the evidence on interventions intended to improve communication about EoL care among health professionals and patients and their family members and carers. Previous research has shown that discussion of prognosis and EoL is important to people who are dying and to their families (Brighton 2016; Fujimori 2020; NICE 2019; Steinhauser 2000; Walczak 2016; Wenrich 2001; Wolfe 2020). It is clear that for people to be able to articulate what they would like, and to participate in decisions about their care in the last stages of their life or the life of someone close to them, they must be adequately informed (Clayton 2007a; NICE 2019). A recent study seeking to develop quality indicators for EoL communication and decision‐making confirmed that these discussions are also important to health professionals and the systems in which EoL care is delivered (Sinuff 2015). The highest‐rated quality indicator overall was related directly to whether discussions about prognosis and the likelihood that the patient is approaching the end of life had actually been undertaken (Sinuff 2015). This review therefore seeks to evaluate how communication about EoL and EoL care might be better undertaken, and to assess the impact of verbal communication on the various people most directly involved.

Description of the intervention

Communication interventions can be broadly defined as "a purposeful, planned and formalised strategy associated with a diverse range of intentions or aims, including to inform, educate, communicate with, support, skill, change behaviour, engage and seek participation of people" (Hill 2011, page 30). This review follows this broad view and considers a communication intervention as a planned interaction provided by health practitioners to communicate with people about EoL and provision of EoL care. Although these interventions may take many forms and may reflect different purposes, to be eligible for this review interventions must have included direct interpersonal (verbal) communication between health practitioners and the patient and the patient's family members and/or carers. Specifically, these interventions could have taken the form of facilitating or improving EoL care discussions targeting a broad range of continuum of care, ranging from rapidly evolving situations to early preparatory stages of what may be a protracted period of terminal care. The review included any EoL communication intervention that involved a patient who was likely to die within 12 months (ACSQHC 2015, page 2; NICE 2017, page 7). Communication interventions must have been primarily interpersonal (verbal) in nature and preferably delivered in‐person, although if necessary they may have included the following channels for communication: in‐person, telephone, videoconferencing, remote video links, and internet‐enabled verbal discussions. Other non‐verbal forms of communication, such as written information, may also have been included as part of the intervention, and while data were collected on these approaches they were not the primary focus of the review.

The intervention may have focused on one or more of the following elements of EoL or EoL care: knowledge of what might happen around the disease and what a possible disease trajectory might be for the patient (prognosis); understanding of the possibilities for treatment, pain management, symptom management, and treatment or care to relieve suffering; preferences for care or treatment or both, including wishes regarding the location of living until dying; needs or concerns related to supportive, spiritual, cultural, or palliative care; needs or concerns related to the role of the family or carer, including support for family members/carers; needs or concerns associated with administrative paperwork, formal documentation, dying or the choice for assisted dying (for jurisdictions where relevant); and death. The intervention may have been tailored towards an individual or a small group, as long as the group includes patients and their family members or carers.

We considered the full range of EoL communication interventions identified as eligible for this review, and we anticipated that their dispersion and application across studies might vary. The needs and circumstances of the people involved were also expected be complex and highly varied. Accordingly, the elements of EoL and EoL care discussed were expected to be tailored to specific EoL contexts. EoL discussions are not limited to a specific healthcare setting, so it was important that this review was inclusive of EoL communication interventions applied irrespective of national, geographical, cultural, social, wealth, and healthcare access boundaries. Such diverse EoL experiences could be related to gender, ethnicity, race, religion, culture, refugee status, indigenous peoples, gender diversity, disability, socioeconomic status, education, poverty, and populations in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Welch 2010). For this reason, the review considered inequality and inequity issues as they relate to EoL communication interventions (Welch 2010).

To ensure this review's focus was maintained on interpersonal communication in the last 12 months of life, we excluded studies that addressed specific decisions, shared or otherwise, and the tools involved in such decision‐making. We also excluded studies focused on advance care planning (ACP) reporting ACP uptake or completion as the primary outcome. Finally, we excluded studies of communication skills training for health professionals unless patient outcomes were reported as primary outcomes.

How the intervention might work

Interventions to improve EoL verbal communication aim to provide more effective general communication between practitioners and the people directly affected by EoL and EoL care. Previous reviews have confirmed the highly complex and varied scope of EoL experiences, and support the need for the study intervention to be fully described and to include EoL context, details of what the intervention entails, and related primary patient outcomes (Fawole 2012; Walczak 2016).

We have described the content of the EoL communication intervention above. Practitioners could use a variety of modalities to deliver the intervention and to guide or influence the discussion about EoL or EoL care. Examples could include prompts for patients to promote or guide discussions about EoL care (Clayton 2007b; Fujimori 2020; Hjelmfors 2020; Sansoni 2014; Walczak 2017); web‐based collaboration tools to facilitate communication between practitioners and people affected by EoL (Voruganti 2017; Walczak 2016); nurse‐led discussions about EoL care (Sulmasy 2017); or EoL family meetings (Agar 2017; Bradford 2021; Walczak 2016). Outcomes chosen to measure effects of the interventions could reflect changes in the level of communication occurring (e.g. increasing the frequency or length or both of discussions between practitioners and patients and affected people), improved structure of the communication taking place (e.g. providing prompts to assist patients, family members, and carers to ensure that key questions are raised with practitioners, thereby improving knowledge and understanding about EoL care), or specific outcomes related to patient's/affected people's EoL care experiences and their experiences of the communication around EoL.

Why it is important to do this review

General EoL communication guidelines are already available. For example, in 2007, Medical Journal of Australia published a supplement titled 'Clinical practice guidelines for communicating prognosis and end of life issues with adults in the advance stages in a life limiting illness, and their caregivers' (Clayton 2007a). More recently published EoL guidelines related to paediatric patients and young people include the 'End of life planning series' (Together for Short Lives 2012), along with 'Difficult Conversations' (Together for Short Lives 2015). EoL care standards and quality markers and measures of EoL care related to communication are also available (ACSQHC 2015; NICE 2017). A more recent exploratory study conducted with paediatric practitioners confirmed that evidence‐based interdisciplinary interventions are needed to support general EoL discussions (Henderson 2017). A systematic review of communication quality improvement interventions for patients with advanced and serious illness completed in 2012 confirmed that better descriptions of communication interventions were needed for assessment of impact on the outcomes being researched (Fawole 2012). Although general guidelines on communication are available, they do not necessarily address or draw on rigorous research evidence related to the effectiveness of specific EoL communication interventions.

A systematic review and meta‐analysis undertaken by Oczkowski in 2016 examined communication tools for EoL decision‐making in ambulatory care settings (Oczkowski 2016). The Oczkowski review was focused on EoL decision‐making and advance care planning and concluded that use of structured communication tools should be the preferred approach to EoL decision‐making conversations (Oczkowski 2016). Another recent systematic review of studies of mixed designs (Thode 2020) assessed the role of communication tools such as decision aids for people considering life‐prolonging treatments. It similarly concluded that prompt lists and decision aids may be useful in communicating with patients about options for treatment, but was based on a small number of studies in a population that is not directly relevant to this current review. Two completed Cochrane Reviews ('Advance care planning for haemodialysis patients' (Lim 2016) and 'Advance care planning for adults with heart failure' (Nishikawa 2020) also have an indirect link with this review. The current review includes discussions on the topic of advance care planning, but only when these conversations are taking place in the last 12 months of life, and only when uptake of advance care planning (ACP) or advance directives (AD) is not the primary goal of the study.

Several other Cochrane Reviews, for example 'End‐of‐life care pathways for improving outcomes in caring for the dying' (Chan 2016); 'Hospital at home: home based end of life care' (Shepperd 2021); and 'Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer' (Moore 2018), have addressed issues related to EoL, but they have not addressed the interventions to improve communication, with a distinct focus on patient outcomes, explored in this current review.

Studies of ACP or AD that did not meet these criteria were therefore deliberately excluded as they focused on the outcomes of the process (i.e. ACP completion) rather patient outcomes (this review's focus). Additionally, these strategies are commonly not closely related in time to the end of life, with many elderly people now asked to undertake ACP in preparation for death that may be years or even decades in the future. This variability in degree of temporal linkage to EoL, as well as heavy reliance on checklists and structured tools common with ACP, also led to the exclusion of these studies. As indicated above, studies focusing on specific decisions using structured tools (e.g. decision aids) were excluded in order to ensure the review maintained a focus on patient outcomes and how these were influenced by communication.

Communication skills training for health professionals was also excluded from this review, unless patient outcomes were reported as primary outcomes. This decision aligned with the reasoning above, as interventions to prepare professionals to communicate typically focus on evaluating the effectiveness of such strategies to improve clinician skills (how, and how well, clinicians communicate) ‐ a step influencing but preceding the communication encounter with patients, and typically reflected in a lesser focus on patient outcomes. One of the review's main underpinning principles was that interventions involved interpersonal interaction between health practitioner(s) and the patient, family, and/or carers in order that the focus on patients be maintained.

It is worth noting that had we included studies with a focus on structured decision‐making tools like those underpinning many approaches to ACP, or those on communication skills training, this review would have quickly become unfeasible and run to inclusion of potentially hundreds of trials ‐ as this represents a very substantial literature. Such a review however, would have a far more dispersed scope, and it would have been very difficult to untangle the effects of interpersonal communication for the people involved at EoL within this larger collective body of research.

Previous reviews of the literature have considered EoL communication interventions. Barnes 2012 undertook a critical review of the literature to explore patient‐professional communication about EoL issues in life‐limiting conditions. These review authors found limited evidence regarding successful interventions to improve discussions with patients about EoL care. Additionally, communication topics are often embedded in more specific EoL research. Walczak 2016 completed an important systematic review of evidence for EoL communication interventions. This review identified 45 studies through a search of the literature conducted in 2014, and review authors concluded that "Overall, greater use of validated measures, commonality of outcomes between studies and meta‐analyses allowing more concrete statements about the efficacy of end‐of‐life communication interventions are vital to the advancement of the field" (Walczak 2016, page 13). Bradford 2021 completed a systematic review regarding family meetings in paediatric palliative care, finding there was little guidance about how meetings should be organised or conducted, or when these should occur. Overall, the literature confirms that there is general agreement that EoL communication and interventions to improve such communication are important for providing quality care for patients and other people affected by EoL.

To inform how EoL communication can be improved in future practice, one must gain an understanding of the effectiveness of communication interventions in the EoL context, and the impact these interventions can have on measurable outcomes for patients, families, and carers. The findings of this review should prove important in this endeavour. Improved and more effective communication between health practitioners and people affected by EoL has the potential to help practitioners address gaps in care and to improve poor outcomes such as distress and lower quality of life associated with poor communication (Brighton 2016). This will provide a foundation where patients and others affected by EoL events can participate in shared decisions about treatment and care.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions designed to improve verbal interpersonal communication about end of life (EoL) care between health practitioners and people affected by EoL.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised and cluster‐randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs evaluating the effects of interventions intended to enhance communication between health practitioners and patients and families or carers about end of life (EoL) care. We expected to find a limited number of RCTs on this topic and therefore planned to include quasi‐RCTs (defined as trials attempting, but not achieving, random allocation of participants).

Types of participants

We included the following participants.

Patients with a life‐limiting illness who were expected to die within 12 months (ACSQHC 2015).

Patients with cancer, end‐stage pulmonary disease, end‐stage cardiac failure, end‐stage renal failure, motor neuron disease, or other chronic conditions (e.g. dementia), as reported in the study.

Patients with a life‐threatening acute condition caused by sudden catastrophic events (ACSQHC 2015).

Vulnerable groups of patients with a life‐limiting illness, as reported in the study. For example, patients could be in a third world setting in which EoL is not explicitly defined. In such cases, researchers may use terms such as 'dying' and 'death', which can be used to identify the study as relevant.

Patients of any age from birth who met one of the criteria listed above.

We also included family or carers of a patient with a life‐limiting illness, as defined by the study. We defined family as "biological, family of acquisition (related by marriage or contract) and the family and friends of choice" (ACSQHC 2015, page 33). We defined a carer as "a person providing personal care, support and assistance for the patient with a life‐limiting illness" (ACSQHC 2015, page 32).

We did not exclude studies based on the setting of the communication or the person delivering the communication, although the communication must have involved a health practitioner. We defined health practitioners for inclusion in this review as follows.

Healthcare professionals may include doctors, nurses, midwives, allied health practitioners, social workers, and government healthcare workers.

The professional population could be identified as the healthcare team, the interdisciplinary team, the interprofessional team, or a group of healthcare providers, as reported in the study.

We included lay health workers, who are not health practitioners as such but who are educated/trained to deliver the intervention (e.g. may be applicable in resource‐poor/low‐ and middle‐income country settings or within a specific cultural context to promote cultural safety).

We included other community providers or volunteers, as reported in the study.

Types of interventions

We included any interventions provided to promote or improve interpersonal communication between health practitioners and people affected by EoL care versus usual care. We also included comparisons of one form of communication intervention versus another.

The communication may have focused on any aspect of EoL or EoL care, including the following.

Knowledge of what might happen around the disease and what a possible disease trajectory might be for the patient (prognosis).

Understanding of the possibilities for treatment, pain management, symptom management, and treatment or care to relieve suffering.

Preferences for care or treatment or both (e.g. resuscitation, feeding), including wishes regarding the location of living until dying.

Needs or concerns related to supportive, spiritual, cultural, or palliative care.

Needs or concerns related to the role of the family or carer, including support for family members/carers.

Needs or concerns associated with administrative paperwork, formal documentation, and dying or the choice for assisted dying (for jurisdictions where relevant).

The intervention must have involved interpersonal interaction between health practitioner(s) and the patient, family, and/or carers. We included videoconferencing, remote video links, or internet‐enabled discussions only if the parties involved could not be located physically together (e.g. in the case of patients living in rural, remote, or underserved areas).

The communication intervention might have included one or more of the following aims: to inform or educate, support, skill, engage, or seek the participation of patients and their families and carers in a communication episode with professionals around EoL care. Interventions could be simple or complex; we included interventions as long as the effects of the communication element of any complex intervention could be isolated by inclusion of an appropriate comparison group.

We excluded the following studies.

Studies focusing on specific decisions ‐ shared or otherwise. This review focused on general communication between health practitioners and patients and their family members and carers. Such communication may be viewed as a necessary and fundamental precursor to more specific decisions about treatment and other choices, which may often involve highly structured or specific communication tools (as described above).

Studies focusing on development or completion of an advance care planning (ACP) or advance directives (AD) for which uptake or completion is the primary outcome.

Studies assessing the effects of public education (e.g. on ACP), or of general individual education (e.g. about ACP, or about how to speak up).

Studies focusing on case conferencing for specific decision‐making needs, or case conferencing about choice of residence (e.g. discharging patient to a nursing home or to a palliative care service).

Studies focusing on communication skills training for health professionals (unless patient outcomes were reported as primary outcomes).

Studies involving health practitioner communication with a group of people, unless that group comprised the patient, family members, and/or carers.

Types of outcome measures

We collected data on a range of primary and secondary outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Patient, family, and/or carer (affected persons) outcomes

Knowledge and understanding about what might happen (prognosis), or what to do, or options.

Evaluation of the communication ‐ positive constructs (e.g. satisfaction, calmness or confidence about ability to manage the future).

Evaluation of the communication ‐ negative constructs (e.g. fear, anxiety, distress).

Discussions of EoL care/EoL (e.g. frequency, length, type, participants).

Adverse outcomes

-

Any adverse outcomes or harms identified in the included studies.

These might have included any negative effects on the primary outcomes listed above.

Secondary outcomes

Health practitioner knowledge and understanding of patient/family/carer knowledge, wishes, or preferences.

Health practitioner evaluation of his or her communication performance, the overall communication encounter, or self‐confidence or preparedness to communicate.

Patient/family member/carer quality of life.

Health systems impacts relevant to the impacts of communication

Costs of subsequent care.

Hospital admissions and re‐admissions (e.g. hospital bed days, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions).

Quality of EoL care (family/carer rated, practitioner rated).

Ratings of concordance with patient preferences for EoL care.

We did not exclude studies that were otherwise eligible based on the outcomes reported, except for the situation described above, in which the intervention focused on ACP/AD and the primary outcome sought was uptake or completion.

Main outcomes for the summary of findings tables

We reported the following outcomes.

Patient, family, and/or carer (affected persons) outcomes

Knowledge and understanding about what might happen (prognosis), what to do, or options.

Evaluation of the communication ‐ positive constructs (e.g. satisfaction, calmness or confidence about ability to manage the future, preparedness to plan for the future).

Evaluation of the communication ‐ negative constructs (e.g. fear, anxiety, distress).

Adverse events

These were reported as any negative changes in the above outcomes associated with the intervention.

We reported findings for each of the primary outcomes in the summary of findings tables.

If multiple outcomes were reported in a given outcome category, we collected information on all relevant outcomes. However, if the same outcome had been assessed by two or more outcome measures in the same trial, we planned for two review authors to:

select the primary outcome measure identified by the publication authors;

select the one specified in the sample size calculation when no primary outcome measure was identified; and

-

rank effect estimates (i.e. list them in order from largest to smallest) and select the median effect estimate if no sample size calculations were reported.

When an even number of outcome measures was reported, we planned to select the outcome measure whose effect estimate was ranked n/2, where n was the number of outcome measures.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases in July 2018, all from inception.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (to 27 July 2018).

MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1946 to 27 July 2018).

Embase (OvidSP) (1947 to 27 July 2018).

PsycINFO (OvidSP) (1806 to 27 July 2018).

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (EBSCOHost) (1937 to 27 July 2018).

Search strategies for all major databases are presented in Appendix 1 to Appendix 2.

There were no language or date restrictions.

We applied the Cochrane RCT Classifier to the database search results. The Classifier assigned a probability (from 0 to 100) of being a randomised trial to each citation retrieved. Those citations with a Classifier scores of nine or less were excluded from dual reviewer screening but were screened by a single reviewer (titles and abstracts) as part of a check of the accuracy of the Classifier and to ensure that no studies were misclassified and wrongly excluded from the search outputs.

Database searches were re‐run in June 2021. Studies potentially meeting the selection criteria are listed in studies Awaiting classification.

Searching other resources

We contacted experts in the field and authors of included studies for advice as to other relevant studies and searched reference lists of relevant studies. We searched (September 2019) relevant grey literature sources (ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, British Library Electronic Theses Online Service (EThOS)), conference proceedings (European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC), American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), World Congress of Psycho‐oncology), and clinical trials registries (US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov and World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP)) to identify relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

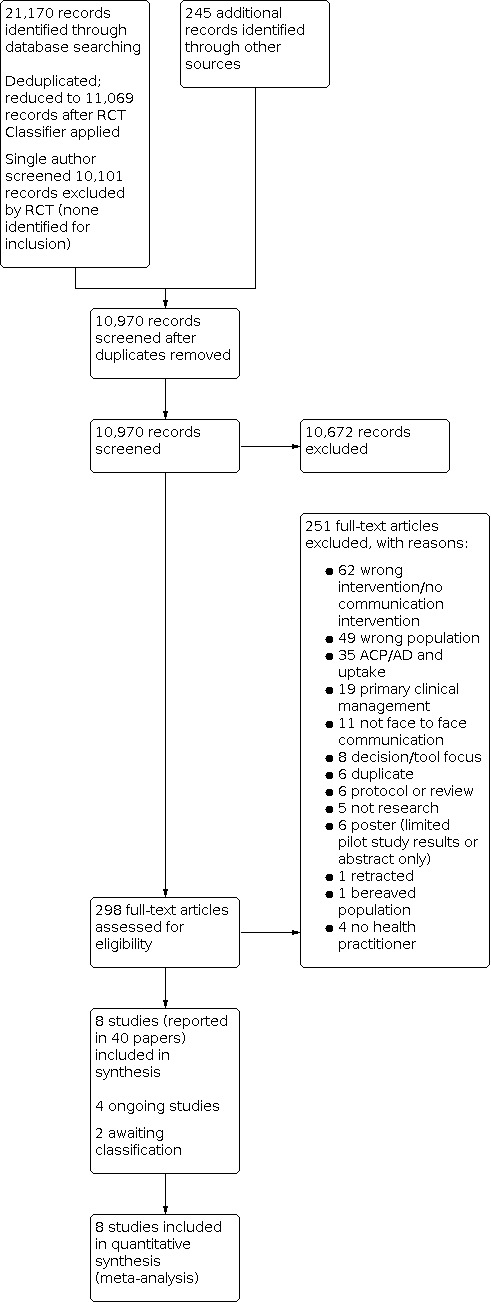

Two review authors independently screened all titles and abstracts identified through searches to determine which met the inclusion criteria. We retrieved in full text any papers identified as potentially relevant by at least one review author. Two review authors independently screened full‐text articles for inclusion or exclusion and resolved discrepancies by discussion and by consultation with a third review author if necessary to reach consensus. We listed all potentially relevant papers excluded from the review at this stage as excluded studies and provided reasons for exclusion in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. We also provided citation details and any available information about ongoing studies and collated and reported details of duplicate publications, so that each study (rather than each report) is the unit of interest in the review. We report the screening and selection process in an adapted PRISMA flow chart (Liberati 2009); see Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Screening was performed by at least two review authors working independently, except those citations classified with a score of nine or less by the RCT Classifier, which were screened by a single review author. Citations from conference proceedings and trials registries were also screened by a single review author, who consulted with a second review author on any potentially relevant studies.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors extracted data from included studies. Ratings of risk of bias were made independently by two review authors, otherwise data were extracted by one review author and checked for accuracy by a second. We resolved any discrepancies by discussion until consensus was reached, or through consultation with a third review author when necessary. We developed and piloted a data extraction form using the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group (CCCG) Data Extraction Template (available at cccrg.cochrane.org/author-resources)). Data extracted included the following: study details (aim of intervention, study design, description of the intervention and comparison group, outcomes, and data). One review author entered all extracted data into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2020), and a second review author working independently checked the data for accuracy against the data extraction sheets.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed and reported on the methodological risk of bias of included studies in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), as well as the guidelines of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group (Ryan 2013), which recommend explicit reporting of the following individual elements for RCTs: random sequence generation, allocation sequence concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, completeness of outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias (baseline imbalances). We considered blinding separately for different outcomes when appropriate (e.g. blinding may have the potential to differently affect subjective versus objective outcome measures). We judged each item as being at high, low, or unclear risk of bias as set out in the criteria provided by Higgins 2011, and provided a quote from the study report or a justification for our judgement or both for each item in the risk of bias table.

We judged studies to be at highest risk of bias if they scored as at high or unclear risk of bias for either the sequence generation or the allocation concealment domain, based on growing empirical evidence that these factors are particularly important potential sources of bias (Higgins 2011).

In all cases, two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies and resolved disagreements by discussion to reach consensus. We contacted study authors for additional information about the included studies, or for clarification of study methods as required. We incorporated results of the risk of bias assessment into the review through standard tables and systematic narrative description and commentary about each of the elements, leading to an overall assessment of the risk of bias of included studies and a judgement about the internal validity of results of the review.

We planned to assess and report quasi‐RCTs as being at high risk of bias on the random sequence generation item of the risk of bias tool, but none were identified. For cluster‐RCTs, we also assessed and reported the risk of bias associated for an additional domain: selective recruitment of cluster participants.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, we analysed data based on the number of events and the number of people assessed in the intervention and comparison groups. We used these numbers to calculate the risk ratio (RR) and the 95% confidence interval (CI) where possible. For continuous measures, we analysed data based on the mean, the standard deviation (SD), and the number of people assessed for both intervention and comparison groups to calculate the mean difference (MD) and 95% CI. If the MD was reported without individual group data, we had planned to use this information to report the study results. If more than one study measured the same outcome using different tools, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) and the 95% CI using the inverse variance method in Review Manager 5.

Unit of analysis issues

We checked cluster‐RCTs for unit of analysis errors. Levels of allocation and analysis were different in all four cluster‐RCTs, but all appropriately adjusted for clustering in their analyses.

If errors and sufficient information were available, we planned to re‐analyse the data using the appropriate unit of analysis, by taking account of the intracluster correlation (ICC). We planned to obtain estimates of the ICC by contacting authors of included studies, or impute them using estimates from external sources. Where it was not possible to obtain sufficient information to re‐analyse the data, we planned to report effect estimates, annotated with 'unit of analysis error'.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to contact authors of all included studies to obtain missing data (participant, outcome, or summary data), or to clarify details of the trial's methods or conduct or both. All but two teams of authors were successfully contacted and provided additional information about their trial. We planned to analyse participant data based on an intention‐to‐treat basis, however we analysed the data as reported. We reported on the levels of loss to follow‐up and assessed this as a source of potential bias.

For missing outcome or summary data, we planned to impute missing data when possible, report any assumptions in the review, and investigate the effects of imputed data on pooled effect estimates through sensitivity analysis. We were unable to conduct these analyses due to the small number of studies contributing data for all outcomes.

Assessment of heterogeneity

When we considered studies similar enough (based on consideration of populations, interventions, or other factors) to allow pooling of data using meta‐analysis, we assessed the degree of heterogeneity by visually inspecting forest plots and by examining the Chi² test for heterogeneity. We quantified heterogeneity by using the I² statistic. We considered an I² value of 50% or more to represent substantial levels of heterogeneity, but we interpreted this value in the light of size and direction of effects and strength of the evidence for heterogeneity, based on the P value derived from the Chi² test (Higgins 2011).

We planned, when we detected substantial clinical, methodological, or statistical heterogeneity across included studies, not to report pooled results from meta‐analysis but instead to use a descriptive approach to data synthesis. However, where we judged studies to be similar enough clinically and methodologically to justify statistical pooling, and data were available, but heterogeneity was high, we reported the pooled result irrespective of high variability and accounted for this in our GRADE ratings of evidence certainty.

At protocol stage we planned to attempt to explore possible clinical or methodological reasons for variation across studies descriptively synthesised by grouping studies that were similar in terms of populations, intervention features, methodological features, or other factors to explore differences in intervention effects. However, numbers of studies contributing data to any one outcome were small and did not allow this type of analysis to go ahead.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting bias qualitatively based on the characteristics of included studies (e.g. if only small studies that indicated positive findings were identified for inclusion), or where information that we obtained upon contacting experts and study authors suggested that there were relevant unpublished studies.

If we had identified sufficient studies (at least 10) for inclusion in the review, we planned to construct a funnel plot to investigate small‐study effects, which may indicate the presence of publication bias. In such instances, we planned to formally test for funnel plot asymmetry, after choosing the test based on advice provided in Higgins 2011, and bearing in mind when interpreting study results that there may be several reasons for funnel plot asymmetry.

Data synthesis

We decided whether to meta‐analyse data based on whether interventions in the included trials were similar enough in terms of participants, settings, comparisons, and outcome measures to ensure meaningful conclusions from a statistically pooled result. Owing to anticipated variability in populations and interventions, and possibly other factors, we used a random‐effects model for meta‐analysis.

Where we were unable to pool the data statistically using meta‐analysis, we prepared a descriptive synthesis of results. We presented data, organised by major outcome categories, and subcategories where applicable, in tables and in text. We had planned to explore the main comparisons of the review (intervention versus usual care; one intervention form versus another) within data categories but only the first comparison was assessed by included studies.

For each outcome/data category, we drew together results of meta‐analysis or descriptive synthesis or both to provide an overall synthesis of the effects of the intervention for each outcome category and subcategory.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not anticipate including enough studies with quantitative data to warrant subgroup analyses, but planned to attempt to explore potential effects of the following factors through systematic grouping of studies and synthesis when possible.

Type of EoL care: groupings might include palliative care, acute (emergency) care, and others. The rationale for considering effects separately in such (or similar) groupings is that communication needs, opportunities to communicate, and information and decisions needed are likely very different across such different types of EoL care.

Type or aim or both of intervention: groupings might include those to inform and educate, those to support communication, and those to promote communication or decision‐making skills. The rationale for separately considering these groupings is that interventions with different purposes have different underlying mechanisms of action.

Too few studies contributing data to any outcome were included in the review to enable the above analyses to proceed.

Sensitivity analysis

As anticipated, we did not include enough studies in any one pooled analysis to justify conducting sensitivity analyses. However, in future if we identify sufficient studies, we will consider removing those rated as having the highest risk of bias from the analysis and examining effects on the pooled effect estimates.

Ensuring relevance to decisions in health care

One of the co‐authors (Josephine Bothroyd (JB)) is a consumer representative for the Healthcare Consumers' Association of the Australian Capital Territory. She had input to the protocol at all stages.

We planned to consult more widely about the consumer perspective with consumer groups, industry, and/or government agencies. However, given the inconclusive findings of the review we did not perform these wider consultations at this stage. This may be an avenue to explore in future updates of the review.

A consumer provided feedback on the protocol and the review as part of standard CCCG editorial processes.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We prepared a summary of findings table to present results for the main outcomes, based on the methods described in Chapter 11 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011). We presented the results of analysis for the major comparison of the review, for each of the major primary outcomes, including potential harms, as outlined in the Types of outcome measures section. We used the GRADE system to rank the certainty of evidence (GRADEpro GDT; Schünemann 2011). Two or more review authors independently assessed outcomes against the GRADE criteria, with discussion to reach consensus on final ratings of certainty.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Database searches identified 21,170 records for screening. The RCT Classifier was used to assess these references, with 11,069 references remaining for screening with a 90% or higher likelihood of being true randomised controlled trials (RCTs). These references were screened, together with another 245 citations identified from searches of grey literature and other sources (e.g. author contact). After de‐duplicating references, two review authors independently screened 10,970 abstracts. Of these, 10,672 were excluded, with 298 papers screened in full text. In total 251 of these papers were excluded, four ongoing studies were identified, two are awaiting classification, and eight studies (reported in 40 papers) were included in the review; see Figure 1 for PRISMA chart.

One review author (Rebecca Ryan (RR)) screened the remaining 10,101 records excluded by the RCT Classifier as being of lower likelihood of being RCTs. No studies were identified for inclusion in the review from this secondary screening.

Included studies

Trial and participant features

Full details of the included studies are given in Characteristics of included studies tables.

We included eight trials, see Table a below. In four, participants were individually randomised to one of two arms, while in the remaining four, clusters of participants were randomised to one of two (three trials) or three (one trial) arms. All cluster trials appropriately adjusted for clustering in their analyses. See Additional Table 2 for participant numbers for each trial.

1. Participant numbers in trials.

| Participant numbers | Agar 2017 | Au 2012 | Bernacki 2019 | Clayton 2007 | Epstein 2017 | Lautrette 2007 | Reinhardt 2014 | Walczak 2017 |

| Eligible for inclusion | Nursing homes: 111 eligible Participants: 148 UC 171 intervention |

1292 1173 mailed introductory letter |

Clinicians: 133 recruited Patients: 9182 screened UC (8530 ineligible) 9395 screened intervention (8842 ineligible) |

196 | Physicians: 38 eligible Patients: 453 eligible |

132 | 214 | 363 |

| Excluded | Nursing homes: 91 (55 did not meet criteria; 36 declined) 14 UC 11 intervention |

30 screened out (did not meet criteria) 21 declined participation prior to screening |

Clinicians: 6 pilot clinicians ineligible Patients: 8987 UC 9211 intervention |

22 | Patients: 137 excluded (38 ineligible, 99 refused) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Refused to take part | ‐ | 645 (did not wish to participate) 101 (did not keep appointment) |

Clinicians: 36 Patients: unclear |

18 | 99 | 6 | 104 | 253 |

| Randomised to intervention group(s) | 10 homes, 160 participants 156 received allocated intervention |

194 | Clinicians: 48 (20 clusters) Patients: 184 (20 clusters) |

92 | Physicians: 19 Patients: 139 Carers: 105 |

63 | 58 | 61 |

| Randomised to control (usual care) group | 10 homes, 134 participants 130 received allocation intervention |

182 | Clinicians: 43 (21 clusters) Patients: 195 (19 clusters) |

82 | Physicians: 19 Patients: 142 Carers: 99 |

63 | 52 | 49 |

| Excluded post‐randomisation (for each group; with reasons if relevant) | UC 66 Intervention 89 All excluded because did not die during the study period |

‐ | 96 (intervention) Death; lost to follow‐up; declined further surveys; completed 2 years 118 (UC) Death; lost to follow‐up; declined further surveys; completed 2 years Intervention: 184 (20 clusters) enrolled: 134 analysed (18 clusters); (50 total: no family/friend response, no baseline survey, withdrew) 34 (13 clusters) analysed: 74 died, 11 lost to follow‐up; 17 declined further surveys; 32 completed 2 years UC: 195 (19 clusters) enrolled: 144 analysed (17 clusters); (51 total: no family/friend response, no baseline survey, withdrew) 26 patients (13 clusters) analysed: 77 died. 12 lost to follow‐up, 21 declined further surveys; 34 completed 2 years |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Withdrawn (for each group; with reasons if relevant) | UC 4 Intervention 4 (died before intervention) |

Control 27 (14.5%) 3 patient‐clinician relationship changed 6 refuse to continue 9 not contactable 8 no target visit 1 too ill/deceased Intervention 43 (22.2%) 4 patient‐clinician relationship changed 15 refuse to continue 8 not contactable 10 no target visit 3 too ill/deceased 3 other |

Intervention 12 Control 8 |

None | Intervention 6 Control 5 |

Intervention 11 Control 7 |

‐ | ‐ |

| Lost to follow‐up (for each group; with reasons) | ‐ | ‐ | Intervention: 11, no reason given Control 12, no reason given |

Intervention: 2, 1 mistakenly seen by a junior physician who was not participating in the study, 1 due to mechanical failure of tape recorder Control: 2, 1 mistakenly seen by a junior physician who was not participating in the study 1 due to mechanical failure of tape recorder |

Intervention: 3 died Control: 1 died 1 lost to follow‐up |

Intervention: did not answer telephone n = 4; experiencing severe emotional distress n = 5; refused interview n = 2 Control: did not answer telephone n = 3; experiencing severe emotional distress n = 1; refused interview n = 2; patient still alive n = 1 |

Total numbers reported at each time point N = 96/110 completed 3‐month measures N = 90/110 completed 6‐month measures Plus an additional 3 where complete data were not available NB also for several outcomes data for slightly lower numbers in total are available i.e. table 3 – ranges from n = 65 to n = 81. Not clear what happened to these missing measures |

Intervention: 21 (34%) Unclear; data collection hampered by declining health, attrition high (higher in intervention group) but no systematic reasons for differential dropout identified. Reasons for loss not reported specifically Control: 9 (18%) Reasons for loss not reported specifically |

| Included in the analysis (for each group, for each outcome) | Intervention 67 Control 64 These numbers were analysed throughout, with losses for particular scales/assessments noted where applicable |

Intervention 194 Control 182 |

Intervention 38 patients (13 clusters) Control 26 patients (13 clusters) |

Intervention 90 Control 80 |

Intervention 19 physicians, 130 patients Control 19 physicians, 135 patients |

Intervention 52 (83%) Control 56 (89%) |

6‐month data (longest time point) Intervention 47 Control 40 |

Intervention 39 Control 40 |

| Assessment of attrition bias for RoB ratings | Assessed as low risk Large proportion of data (participants randomised) missing. However, these were comparable for the 2 study groups, and was due to participants not dying during the study period (outcomes assessed for this study were focused on those around death) Withdrawal rates for other reasons were low and comparable across groups |

Assessed as unclear risk Withdrawal 15% to 22% respectively control and intervention arms Reasons for withdrawal/dropout were reasonably comparable except that more (15 versus 6) refused to continue participation in the intervention group Authors report no differences in baseline characteristics regarding whether patients completed the study or were lost to follow‐up ITT analysis was used; effect of imputed data on results was examined in analysis models with authors reporting similar results where imputed and non‐imputed data were used in analysis |

Assessed as unclear risk Patient participation rates and numbers analysable were low but comparable between arms Authors note non‐participants and those not analysed were not significantly different from those who were analysed, and groups were still comparable (based on randomisation), although non‐participants were older, and less likely to have breast cancer than participants; and those patients with analysable data were more likely to be married and have higher incomes than those with non‐analysable data |

Assessed as low risk Low levels of loss to follow‐up 4/174; balanced across groups (n = 2 each), with comparable reasons |

Assessed as low risk "Fewer than 3% of follow‐up questionnaires were missing" (page 95) Data seem otherwise complete for outcomes reported in main paper and in supplement 3 |

Assessed as low risk Loss to follow‐up and withdrawals were acceptably low and comparable across study groups: 52/63 (83%) completed interviews at 90 days intervention group, 56/63 (89%) in control group Reasons for withdrawal/loss were similar across groups (not answering telephone, refused interview), although higher rates of severe emotional distress in intervention group (n = 5) than control group (n = 1) |

Assessed as unclear risk Missing data were reported 110 were randomly assigned and completed baseline interviews; 96 (87%) completed 3 month outcomes; 90 (82%) completed 6 month outcomes Losses were fairly comparable across groups and no major differences between those who completed the study and those who dropped out (on key demographic features) were noted by the authors However, numbers were lower for some outcomes (such as ratings of care management) where n = 65 (numbers fairly comparable between the 2 groups) Not clear what impact this may have had on the result, or what the reasons for this missing data were |

Assessed as high risk Attrition was high (31/110 (28%) lost to follow‐up), possibly largely explained by declining health of participants (patients) Higher in intervention group. No systematic reasons for differential attrition were identified by authors but 34% dropout in intervention group is substantial and may introduce bias Authors state that ITT analysis was used (according to group assignment) but dropout rates may be problematic |

| Additional notes | The study was underpowered for the primary outcome because fewer participants died during the study period than predicted Predicted sample size required recruitment of 272 participants (assuming 10% dropout rate) (17 per site) |

‐ | Sample size calculated as 200 evaluable patients per arm for required power, assuming 6% dropout | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Trial is underpowered (sample size calculated at 140; 110 recruited; 79 completed) to detect differences between groups |

ITT: intention to treat; RoB: risk of bias; UC: usual care.

All studies were conducted in high‐income countries (four USA, three Australia, one France), and all in urban settings mostly associated with larger hospitals, clinics, or residential care facilities. All participants were older patients where the mean age was 60 years or more, despite inclusion criteria being wide (aged 18 years and older) for most studies, and even in the single study conducted in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting (Lautrette 2007). Most studies included minority ethnic groups to a small degree, and most explicitly excluded people not fluent in the majority language (English or French) and those with cognitive impairment.

Gender composition varied across trials: in the two dementia trials most patients were female (approximately 60% to 80%), whereas gender in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients in Veteran's Affairs centres was almost exclusively male (96% or more). Other trials fell between these extremes. Only one trial reported surrogates' characteristics, with 70% or more of surrogate decision makers for ICU patients being female.