Abstract

The ncc and nre nickel resistance determinants from Ralstonia eutropha-like strain 31A were used to construct mini-Tn5 transposons. Broad host expression of nickel resistance was observed for the nre minitransposons in members of the α, β, and γ subclasses of the Proteobacteria, while the ncc minitransposons expressed nickel resistance only in R. eutropha-like strains.

Several nickel resistance determinants have been identified in Ralstonia eutropha (Alcaligenes eutrophus) (24) strains isolated from different biotopes heavily polluted with heavy metals. The cnrYXHCBA operon of R. eutropha CH34 plasmid pMOL28 (12), which mediates medium levels of nickel resistance (up to 10 mM) and cobalt resistance, is the most thoroughly studied determinant (3, 11, 17, 18, 20). The resistance mechanism mediated by cnr is inducible and is due to an energy-dependent efflux system driven by a chemo-osmotic proton-antiporter system (6, 18, 22, 23). A 14.5-kb BamHI fragment of plasmid pTOM9 from R. eutropha-like strain 31A (Alcaligenes xylosoxidans 31A) (10) and a similar BamHI fragment of plasmid pGOE2 from R. eutropha-like strain KTO2 were also found to encode Ni resistance. On both fragments a locus mediating high-level nickel resistance (up to 20 to 50 mM) and a locus mediating low-level nickel resistance (3 mM) were identified and designated ncc and nre, respectively (15, 16). The nccYXHCBAN determinant, which except for the nccN gene is very similar to cnr, causes high levels of nickel and cobalt resistance and a low level of cadmium resistance in R. eutropha. Neither cnr nor ncc is expressed in Escherichia coli. On the other hand, the 1.8-kb nre locus causes low levels of nickel resistance in both Ralstonia and E. coli (16). An nre-like determinant, which could be expressed in E. coli and Citrobacter freundii, was also found in Klebsiella oxytoca CCUG15788 (19, 20).

Recently, amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis was used to determine the phylogenetic position of zinc- and nickel-resistant Ralstonia-like strains (2). The ncc operon was found in many nickel-resistant R. eutropha-like strains and in environmental strains in the direct vicinity of the genus Burkholderia (2), a member of the β subclass of the class Proteobacteria like the genus Ralstonia. This might indicate that ncc has range of expression broader than the genus Ralstonia.

Heavy metal resistance markers with broad host expression ranges have been shown to be useful for genetic manipulation of Pseudomonas strains potentially designated for environmental release (14). Broad-host-range expression of ncc-nre was recently confirmed by Dong et al. (7), who found ncc-nre-based Ni resistance in Comamonas, Sphingobacterium heparinum, flavobacteria, and even gram-positive bacteria related to Arthrobacter. However, it was not clear from this study which of the Ni resistance determinants was responsible for the broad-host-range Ni resistance. In addition, plasmid instability problems were encountered with some of the transconjugants. In order to study the range of expression of ncc and nre and to develop new tools for genetic manipulation of environmental bacteria, which are not based on antibiotic resistance markers, the Ni resistance markers were introduced into mini-Tn5 transposon vectors. The new nre-based minitransposons were found to have a broad expression range and were successfully used for constructing Ni-resistant transconjugants of plant-associated bacteria belonging to families of the α, β, and γ subclasses of the class Proteobacteria, including plant-associated endophytic bacteria with potential to improve phytoremediation strategies (C. Lodewyckx, S. Taghavi, M. Mergeay, J. Vangronsveld, H. Clijsters, and D. van der Lelie, submitted for publication).

Construction of Ni resistance minitransposons.

The ncc operon of pTOM9 was cloned in pUC18/NotI as a 8.1-kb BamHI-PstI fragment, resulting in pMOL1522 (E. coli CM2395). Plasmid pMOL1522 was digested with NotI, and the ncc-containing NotI fragment was subsequently cloned in the unique NotI site of pUTmini-Tn5-Km1 (4). This resulted in plasmid pUTminiTn5-Km1/ncc (pMOL1524 in E. coli CM2428).

In order to construct an nre-based mini-Tn5 transposon vector, it was necessary to inactivate the NotI site in nreB. PCR mutagenesis performed with primers nre-PstI (sense) and nre-NotI (antisense) and with primers nre-NotI (sense) and nre-EcoRI (antisense) (Table 1) was used to change the NotI site with the sequence GCGGCCGC into GCGGCAGC. This resulted in two PCR fragments that were approximately 1.6 and 1.1 kb long, respectively. Subsequently, these fragments were mixed and joined by using a PCR-based ligation strategy and were amplified with primers nre-PstI (sense) and nre-EcoRI (antisense). This resulted in a 2.7-kb PstI-EcoRI fragment with the mutated nre operon. The mutation did not affect the amino acid sequence of the NreB protein, since GCC and GCA both encode alanine. The 2.7-kb PstI-EcoRI fragment was subsequently cloned into pUC18/NotI, resulting in plasmid pMOL1525 (E. coli CM2438). Plasmid pMOL1525 was digested with NotI, and the nre-containing NotI fragment was cloned in the unique NotI site of pUTmini-Tn5-Km1. This resulted in plasmid pUTminiTn5-Km1/nre(NotI) (pMOL1527 in E. coli CM2442).

TABLE 1.

Primers used for PCR mutagenesis and amplification of the nre regiona

| Primer | Start position | End position | Sequence (5′-3′) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nre-PstI (sense) | 1477 | 1510 | CGC CTG CAG CGC AGA CCG TGG CGG CAG CGG CGC C | |

| nre-PstI (antisense) | 4183 | 4160 | AAA CTG CAG CCC GGA TTG AAA ATG CGA CTC ATG | AAA CTG CAG was added at the 5′ end |

| nre-EcoRI (antisense) | 4189 | 4160 | AAA GAA TTC CCC GGA TTG AAA ATG CGA CTC ATG | AAA was added at the 5′ end |

| nre-SfiI (sense) | 2234 | 2286 | GGA GAG CGC CGT GAC CCA GGC gAA GAA GGC gCT GGT GCA TGA CCA TAT CGA CC | Mutations (C to G) are indicated by lowercase g |

| nre-SfiI (antisense) | 2286 | 2234 | GGT CGA TAT GGT CAT GCA CCA GcG CCT TCT TcG CCT GGG TCA CGG CGC TCT CC | Mutations (G to C) are indicated by lowercase c |

| nre-NotI (sense) | 3107 | 3164 | GAA GGG ACT GCT GGC GCT GAA TCT TGC CGC GGC aGC AGC CAG CGC CAT GGT GAT CGT G | Mutation (C to A) is indicated by lowercase a |

| nre-NotI (antisense) | 3164 | 3107 | CAC GAT CAC CAT GGC GCT GGC TGC tGC CGC GGC AAG ATT CAG CGC CAG CAG TCC CTTC | Mutation (G to T) is indicated by lowercase t |

The region with the mutated nreB gene was also amplified as a 2.7-kb PstI fragment by using primers nre-PstI (sense) and nre-PstI (antisense). Subsequently, this fragment was cloned in the unique PstI site of pMOL1522. This resulted in a 10.8-kb ncc-nre fragment flanked by two NotI sites (plasmid pMOL1548 in E. coli CM2500). This fragment was subsequently cloned in the unique NotI site of pUTmini-Tn5-Km1, resulting in plasmid pUTminiTn5-Km1/ncc-nre (NotI) (pMOL1554 in E. coli CM2520).

To inactivate the SfiI site in nreA, we used a strategy similar to that used for mutation of the NotI site, except that primers nre-PstI (sense) and nre-SfiI (antisense) and primers nre-SfiI (sense) and nre-EcoRI (antisense) were used. The mutations did not affect the amino acid sequence of the NreA protein. A 2.7-kb PstI-EcoRI fragment with the mutated nre operon (SfiI site) was subsequently cloned in pUC18/SfiI (8), resulting in plasmid pMOL1526 (E. coli CM2440). Plasmid pMOL1526 was digested with SfiI, and the nre-containing SfiI fragment was cloned in SfiI-digested pUTmini-Tn5-Km1. This resulted in plasmids pUTminiTn5-Km1/nre(SfiI) (pMOL1529 in E. coli CM2446) and pUTminiTn5-nre(SfiI) (pMOL1528 in E. coli CM2444), in which the kanamycin resistance gene was replaced by nre. The restriction maps of the mini-Tn5 Ni resistance transposons are presented in Fig. 1.

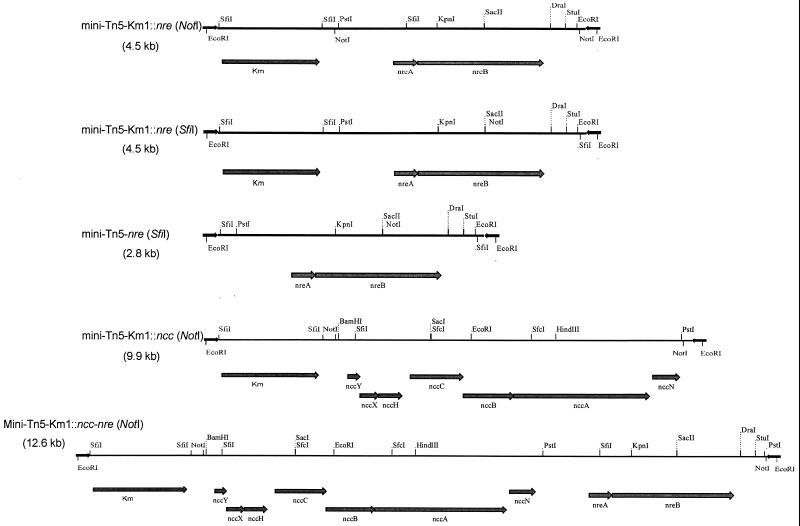

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of different mini-Tn5 Ni resistance transposons. The positions of the kanamycin resistance marker (Km), the Ni resistance determinants ncc and nre, the inverted repeats at the extremities of the minitransposons, and important restriction sites are indicated. The sizes of the minitransposons are given in parentheses.

Range of expression of Ni resistance.

The range of expression of Ni resistance was examined for all mini-Tn5 Ni resistance transposons. To do this, the pUT-based constructs were introduced into E. coli S17-1 (λpir) (5) and subsequently transferred by conjugation into the nickel-sensitive strains R. eutropha AE104 (12), E. coli DH10B, Burkholderia cepacia W1.2 (isolated from wheat) and LS2.4 (isolated from lupine shoots) (a gift from K. Ophel-Keller), Herbaspirillum seropedicae LMG2284 (associated with rye grass) (1), Pseudomonas stutzeri A15 (associated with rice roots) (13, 25), Azospirillum irakense KBC1 (a rice endophyte) (9), and Pseudomonas putida VMO433. The last strain was isolated as an endophytic bacterium after surface sterilization of Brassica napus plants (Lodewyckx and van der Lelie, unpublished data). Transfer frequencies, as well as the appearance of nickel- and kanamycin-resistant mutants, were examined. The results are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Mutation and transconjugation frequencies of the strains used to test transfer and heterologous expression of ncc, nre, and ncc plus nrea

| Donor | Recipient | Frequency of transconjugation

|

Frequency of mutation

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni resistant | Kanamycin resistant | Ni resistant | Kanamycin resistant | ||

| CM2676 (nre Kmr) | AE104 | 9.2 × 10−5 | <7.1 × 10−10 | 2.4 × 10−8 | |

| DH10B | 4.6 × 10−6 | <4.2 × 10−10 | <4.2 × 10−10 | ||

| LMG2284 | 9.7 × 10−8 | <1.8 × 10−9 | 1.3 × 10−8 | ||

| W1.2 | 7.1 × 10−10 | <4.5 × 10−10 | <4.5 × 10−10 | ||

| LS2.4 | 5.8 × 10−8 | <0.8 × 10−9 | 5.7 × 10−8 | ||

| A15 | 1.7 × 10−9 | <1.3 × 10−10 | <1.3 × 10−10 | ||

| VM0433 | 3.9 × 10−6 | <2.5 × 10−10 | 3.5 × 10−8 | ||

| CM2677 (nre) | AE104 | 9.5 × 10−5 | |||

| DH10B | 9 × 10−6 | ||||

| LMG2284 | 1.1 × 10−7 | ||||

| W1.2 | <4.5 × 10−10 | ||||

| LS2.4 | 2.7 × 10−8 | ||||

| A15 | 9.6 × 10−9 | ||||

| VM0433 | 3.7 × 10−6 | ||||

| CM2536 (ncc Kmr) | AE104 | 1.5 × 10−5 | 8.2 × 10−6 | ||

| DH10B | <4.2 × 10−10 | 2.8 × 10−7 | |||

| LMG2284 | <1.8 × 10−9 | 1.2 × 10−7 | |||

| W1.2 | <4.5 × 10−10 | 1.3 × 10−9 | |||

| LS2.4 | <0.8 × 10−9 | 2.3 × 10−7 | |||

| A15 | <1.3 × 10−10 | 3.3 × 10−9 | |||

| VM0433 | <2.5 × 10−10 | 1.4 × 10−7 | |||

| CM2520 (ncc nre Kmr) | AE104 | 8.6 × 10−7 | |||

| DH10B | 1.8 × 10−7 | ||||

| LMG2284 | 1.4 × 10−8 | ||||

| W1.2 | 1.1 × 10−9 | ||||

| LS2.4 | 2 × 10−9 | ||||

| A15 | 1.3 × 10−9 | ||||

| VM0433 | 1.5 × 10−7 | ||||

The strains used as recipients in the matings were R. eutropha AE104, E. coli DH10B (Gibco BRL), H. seropedicae LMG2284, B. cepacia W1.2 and LS2.4, P. stutzeri A15, and P. putida VMO433. E. coli S17-1 (λpir) (5) containing pUTminiTn5-Km1::ncc-nre (strain CM2520), pUTminiTn5-Km1::ncc (strain CM2536), pUTminiTn5-Km1::nre (strain CM2676), and pUTminiTn5-nre (strain CM2677) were used as donors. Ni-resistant transconjugants were selected on 284 minimal medium containing 1 mM NiCl2. Most of the kanamycin-resistant transconjugants were selected on 284 minimal medium (12) containing 100 mg of kanamycin per liter; the only exception was strain AE104, whose transconjugants were selected on 284 minimal medium containing 1,000 mg of kanamycin per liter.

Comparing the efficiencies of transfer of the minitransposons, we observed that R. eutropha AE104, E. coli DH10B, and P. putida VM0433 showed the highest transfer frequencies. The lowest transfer frequencies were observed for B. cepacia W1.2 and P. stutzeri A15; this might have been due to the presence of efficient restriction-modification systems present in these two strains.

No spontaneous Ni-resistant mutants were found for the strains used in the experiments; this is in contrast to the kanamycin-resistant mutants that were observed at low frequencies (∼10−8) for most of the strains tested. This indicates that nickel resistance is a more reliable marker for selecting transconjugants than kanamycin.

Transconjugants were selected for kanamycin or nickel resistance (Table 2). The stabilities of the transconjugants were confirmed by growing them for more than 100 generations under nonselective conditions. Subsequently, the Ni resistance of these organisms was compared to that of the wild-type strains. As expected, both ncc- and nre-containing mini-Tn5 transposons gave Ni resistance in R. eutropha AE104, and the MICs on 284 gluconate medium (Lodewyckx et al., submitted) were 3 and 40 mM Ni for nre and ncc, respectively (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

MICs of Ni in 284 minimal medium for wild-type strains and their Ni resistance transconjugants

| Strain | MICs (mM)a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | MiniTn5-Km1::ncc (NotI) | MiniTn5-Km1::nre (SfiI) | MiniTn5::nre (SfiI) | MiniTn5-Km1::ncc-nre (NotI) | |

| Ralstonia metallidurans AE104 | 0.6 | 20–40 | 3–4 | 3–4 | >40 |

| Herbaspirillum seropedicae LMG2284 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 3–4 | 3–4 | 2 |

| Burkholderia cepacia | |||||

| W1.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | NDb | 2 |

| LS2.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Pseudomonas putida VM0433 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 3–4 | 3 | 3 |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri A15 | 0.6 | 1 | 3–4 | 2–3 | 3 |

| Escherichia coli DH10B | ≤0.6 | ≤0.6 | 3 | 2 | 2–3 |

The ranges of the MICs were determined with four individual transconjugants.

ND, not determined (no transconjugants available).

For all of the other strains tested except B. cepacia W1.2, Ni resistance was observed when the nre determinant was present. For these strains miniTn5-Km1/ncc-containing transconjugants had to be selected for kanamycin resistance. The presence of nre resulted in MICs of Ni for Ni resistance on 284 minimal medium with an appropriate C source that varied from 2 to 3 mM depending on the bacterial species (Table 3). In all cases the presence of nre was confirmed by PCR (results not shown). No Ni resistance was observed for transconjugants containing ncc, and the presence of both ncc and nre in general did not increase the MIC for Ni resistance, as determined for nre. However, two exceptions were found: in P. stutzeri A15 the presence of ncc resulted in an increase in Ni resistance (MIC) from 0.6 to 1.0 mM, while B. cepacia W1.2 transconjugants showed Ni resistance only when both ncc and nre were present. The latter phenomenon might imply that both ncc and nre contribute to Ni resistance, but it is not clear in what way. Therefore, it can be concluded that in general broad-host-range Ni resistance is encoded by nre and that the ncc determinant is expressed only in R. eutropha-like strains. This implies that only the nre-based nickel resistance minitransposons, such as miniTn5-nre(SfiI), are suitable as broad-host-range selection markers for construction of antibiotic resistance-free but selectable strains belonging to the families of the α, β, and γ subclasses of the class Proteobacteria.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the European Commission and OVAM as an EFRO project.

We are grateful to K. Ophel-Keller and J. Balandreau for providing the B. cepacia strains used in this study and to J. Vanderleyden and M. Gillis for providing the H. seropedicae strain. We also thank T. Engelen and A. Bossus for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldani J I, Baldani V D L, Olivares F L, Kirchof G, Hartmann A, Pot B, Hoste B, Falsen E, Kersters K, Gillis M, Döbereiner J. Emended description of Herbaspirillum; inclusion of (Pseudomonas) rubrisubalbicans, a milk plant pathogen, as Herbaspirillum rubrisubalbicans comb. nov.; and classification of a group of clinical isolates (EF group 1) as Herbaspirillum species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:802–810. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-3-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brim H, Heyndrickx M, De Vos P, Wilmotte A, Springael D, Schlegel H G, Mergeay M. Amplified rDNA restriction analysis and further genotypic characterisation of metal-resistant soil bacteria and related facultative hydrogenotrophs. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1999;22:258–268. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(99)80073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collard J-M, Provoost A, Taghavi S, Mergeay M. A new type of Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34 zinc resistance generated by mutations affecting regulation of the cnr cobalt-nickel resistance system. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:779–784. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.779-784.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Jakubzik U, Timmis K. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6568-6572.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in Gram-negative bacteria with Tn5 and Tn10-derived mini-transposons. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:386–405. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diels L, Dong Q, van der Lelie D, Baeyens W, Mergeay M. The czc operon of Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34: from resistance mechanism to the removal of heavy metals. J Ind Microbiol. 1995;14:142–153. doi: 10.1007/BF01569896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong Q, Springael D, Schoeters J, Nuyts G, Mergeay M, Diels L. Horizontal transfer of bacterial heavy metal resistance genes and its applications in activated sludge systems. Water Sci Technol. 1998;37:465–468. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khammas K M, Ageron E, Grimont P A D, Kaiser P. Azospirillum irakense sp. nov., nitrogen fixing bacterium associated with rice roots and rhizosphere soil. Res Microbiol. 1989;140:679–693. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(89)90199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemke K. Schwermetallresistenz in den zwei Alcaligenes-Stämmen A. eutrophus CH34 und A. xylosoxydans 31A: Transposonmutagenese, Klonierung und Sequenzierung. Ph.D. thesis. Göttingen, Germany: Universität Göttingen. Cuvillier Verlag Göttingen; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liesegang H, Lemke K, Siddiqui R A, Schlegel H G. Characterization of the inducible nickel and cobalt resistance determinant cnr from pMOL28 of Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:767–778. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.767-778.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mergeay M, Nies D, Schlegel H G, Gerits J, Charles P, Van Gijsegem F. Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34 is a facultative chemolithotroph with plasmid-bound resistance to heavy metals. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:328–334. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.1.328-334.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiu Y S, Zhou S P, Mo X Z, Wang D, Hong J H. Study of nitrogen fixing bacteria associated with rice root. Acta Microbiol Sin. 1981;21:468–472. . (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanchez-Romero J M, Diaz-Orejas R, de Lorenzo V. Resistance to tellurite as a selection marker for genetic manipulations of Pseudomonas strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4040–4046. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.4040-4046.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt T, Stoppel R-D, Schlegel H G. High-level nickel resistance in Alcaligenes xylosoxidans 31A and Alcaligenes eutrophus KTO2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3301–3309. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.11.3301-3309.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt T, Schlegel H G. Combined nickel-cobalt-cadmium resistance encoded by the ncc locus of Alcaligenes xylosoxidans 31A. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7045–7054. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.7045-7054.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sensfuss C, Schlegel H G. Plasmid pMOL28-encoded resistance to nickel is due to specific efflux. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;55:295–298. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siddiqui R A, Benthin K, Schlegel H G. Cloning of pMOL28-encoded nickel resistance genes and expression of the genes in Alcaligenes eutrophus and Pseudomonas spp. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5071–5078. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5071-5078.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stoppel R D, Meyer M, Schlegel H G. The nickel resistance determinant cloned from the enterobacterium Klebsiella oxytoca: conjugational transfer, expression, regulation and DNA homologies to various nickel-resistant bacteria. Biometals. 1995;8:70–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00156161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoppel R-D, Schlegel H G. Nickel-resistant bacteria from anthropogenically nickel-polluted and naturally nickel-percolated ecosystems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2276–2285. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2276-2285.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taghavi S, Mergeay M, van der Lelie D. Genetic and physical maps of the Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34 megaplasmid pMOL28 and its derivative pMOL150 obtained after temperature induced mutagenesis and mortality (TIMM) Plasmid. 1997;37:22–34. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tibazarwa C, Wuertz S, Mergeay M, Wyns L, van der Lelie D. Regulation of the cnr cobalt and nickel resistance determinant of Ralstonia eutropha (Alcaligenes eutrophus) CH34. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1399–1409. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.5.1399-1409.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varma A K, Sensfuss C, Schlegel H G. Inhibitor effects on the accumulation and efflux of nickel ions in plasmid pMOL28-harboring strains of Alcaligenes eutrophus. Arch Microbiol. 1990;154:42–49. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yabuuchi E, Kosako Y, Yano I, Hotta H, Nishiuchi Y. Transfer of two Burkholderia and an Alcaligenes species to Ralstonia gen. nov.: proposal of Ralstonia pickettii (Ralston, Palleroni and Doudoroff 1973) comb. nov., Ralstonia solanacearum (Smith 1896) comb. nov. and Ralstonia eutropha (Davis 1969) comb. nov. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39:897–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb03275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.You C B, Li X, Wang H X, Qiu Y S, Mo X Z, Zhang Y L. Associative nitrogen fixation of Alcaligenes faecalis with rice plant. Biol. N2. Fixation Newsl Sydney. 1983;11:92–103. [Google Scholar]