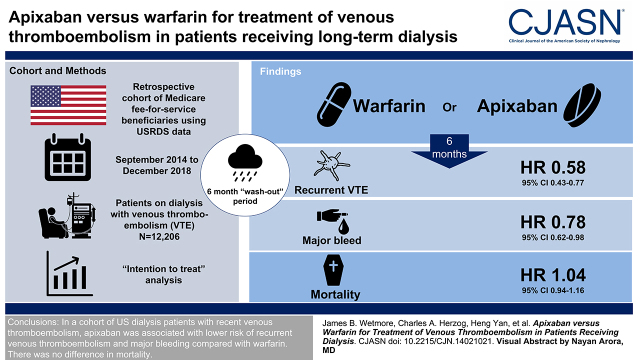

Visual Abstract

Keywords: apixaban, direct oral anticoagulants, warfarin, deep vein thrombosis, ESKD, end stage kidney disease, dialysis

Abstract

Background and objectives

The association of apixaban compared with warfarin for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients receiving maintenance dialysis is not well studied.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries receiving dialysis using United States Renal Data System data from 2013 to 2018. The study included patients who received a new prescription for apixaban or warfarin following a venous thromboembolism diagnosis. The outcomes were recurrent venous thromboembolism, major bleeding, and death. Outcomes were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards regression for intention-to-treat and censored-at-drug-switch-or-discontinuation analyses. Models incorporated inverse probability of treatment and censoring weights to minimize confounding and informative censoring.

Results

In 12,206 individuals, apixaban, compared with warfarin, was associated with lower risks of both recurrent venous thromboembolism (hazard ratio [HR], 0.58; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.43 to 0.77) and major bleeding (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.62 to 0.98) in the intention-to-treat analysis over 6 months of follow-up. However, there was no difference between apixaban and warfarin in terms of risk of all-cause death (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.94 to 1.16). Corresponding hazard ratios for the 6-month censored-at-drug-switch-or-discontinuation analysis and for corresponding analyses limited to a shorter (3-month) follow-up were all highly similar to the primary analysis.

Conclusions

In a large group of US patients on dialysis with recent venous thromboembolism, we observed that apixaban was associated with lower risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism and of major bleeding than warfarin. There was no observed difference in mortality.

Introduction

Annually in the United States, there are an estimated 1.2 million cases of venous thromboembolism, comprising deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (1). CKD is an established risk factor for venous thromboembolism (2,3). In particular, risk of venous thromboembolism is much higher among patients with kidney failure compared with the general population (4,5). The mechanism linking kidney failure with increased thrombosis risk likely relates to disturbances in hemostasis, including activation of procoagulants and platelets and decreases in endogenous anticoagulants and fibrinolytic activity (6).

The primary treatment of venous thromboembolism typically involves use of an oral anticoagulant for 3–6 months (7,8). Over the past decade, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have rapidly displaced warfarin (9), including among patients with kidney failure receiving dialysis (10,11). In contrast with warfarin, DOACs act more quickly, have fewer drug interactions, and do not require routine laboratory monitoring, making them a promising alternative. However, relatively few patients with kidney failure were included in clinical trials of DOACs; as a result, there still remain clinical concerns regarding the use of DOACs in the kidney failure population.

The comparative effectiveness and safety of various oral anticoagulant treatments for venous thromboembolism are relatively understudied in the CKD population (12,13). There has been a rapid uptake of apixaban, in particular, for stroke prevention among US Medicare beneficiaries with both nondialysis-dependent CKD (14) and dialysis-requiring kidney failure with atrial fibrillation (11). In this study, using data from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) (15), we sought to investigate the effectiveness and safety of apixaban versus warfarin for the treatment of venous thromboembolism among patients with kidney failure requiring maintenance dialysis. We hypothesized that apixaban would be associated with lower risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism, major bleeding, and all-cause mortality in comparison with warfarin.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This was a retrospective cohort study of patients receiving maintenance dialysis using the USRDS Standard Analysis Files. These files include patient-level enrollment information linked with kidney failure treatment history and Medicare institutional (Part A), physician/supplier (Part B), and prescription drug (Part D) claims. The analysis included adult Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who used either warfarin or apixaban between September 1, 2014 (shortly after the approval of apixaban for treating venous thromboembolism in the United States) and December 31, 2018 (currently the most recent data available from USRDS) following a venous thromboembolism diagnosis. The date of the first prescription became the index date. A 6-month “washout period” was used to exclude prevalent oral anticoagulant users. Thus, we used an active comparator, new user design, which reduces the potential for confounding by indication and immortal time bias (16,17).

Identification of Venous Thromboembolism at Baseline

Venous thromboembolism at baseline was identified through one or more Medicare Part A or B claims with a diagnosis of venous thromboembolism, in any position on the claim, occurring in the 31 days prior to and including the index date. International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revisions, Clinical Modification (ICD-9/10-CM) diagnosis codes used to define venous thromboembolism are shown in Supplemental Table 1. Venous thromboembolism was further categorized as deep venous thrombosis only versus pulmonary embolism (with or without deep venous thrombosis).

Demographic and Comorbidity Variables

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, sex, race, enrollment in Medicaid, receipt of Part D low-income subsidy, and urban residence (utilizing rural-urban commuting area codes). For an additional covariate control, we included modality/vascular access type (hemodialysis with a catheter, graft, or fistula or peritoneal dialysis in the 6 months prior to the index date), time since onset of kidney failure, and primary cause of kidney failure.

Comorbid conditions were identified in the 6 months prior to the index date on the basis of one or more inpatient claims or two or more outpatient or physician claims on different days with ICD-9/10-CM diagnosis codes, as defined by Quan et al. (18). We also identified possible provoking factors for venous thromboembolism, including major surgery or trauma (Supplemental Table 2), an institutional stay (inpatient or skilled nursing) of ≥3 days, and active cancer or chemotherapy. Except for cancer, all provoking factors were identified in the 90 days prior to the index date; cancer was identified in accordance with the other comorbid conditions in the 6 months prior. We also quantified the total number of hospital admissions, days in hospital, and emergency department or observation unit encounters in the 6 months prior to the index date.

To create a score to reflect putative frailty, we used a variation of a previously developed claims-based algorithm to assign a disability proxy score (14), which has been shown to be associated with adverse outcomes. This approach is detailed in Supplemental Material and Supplemental Table 3. Lastly, we identified the use of ten key prescription medication classes during the 6 months prior to the index date.

Follow-Up

In the “intention-to-treat” (ITT) analysis, patients were followed until the earliest of the following: date of the outcome of interest, death, loss of Medicare coverage, change of modality or kidney transplant, other loss of follow-up, or after 3 or 6 months. The ITT analysis mimicked a clinical trial by classifying the patient as being exposed to the first drug initiated for the duration of follow-up. For the censored-at-drug-switch-or-discontinuation analysis, which mimics the censoring that would occur in an “as-treated” analysis in a clinical trial, additional sources of censoring were treatment discontinuation (i.e., a gap of >7 days without a prescription refill) or drug switching.

Outcomes

The primary effectiveness end point was recurrent venous thromboembolism defined as an inpatient hospital admission with a diagnosis of venous thromboembolism in the primary position using the codes listed in Supplemental Table 1. The primary safety end point was major bleeding, which was defined to include bleeding events that were fatal, involved a critical site, or required a blood transfusion. Bleeding events were identified using a recent adaptation (9) of the widely used Cunningham bleeding algorithm (19), a validated algorithm that captures bleeding events that resulted in a hospitalization. All-cause mortality was also assessed as a secondary safety end point.

Statistical Analyses

A weighting approach, including both inverse probability of treatment (IPT) and inverse probability of censoring (IPC) weights, was used to create a pseudopopulation in which imbalance in patient characteristics at baseline (i.e., measured confounding) and selection bias due to differential loss to follow-up (i.e., informative censoring), respectively, do not exist (20,21). The pseudopopulation became the analytic cohort.

Logistic regression was used to estimate the probability of being in the treatment group actually observed conditional on all baseline characteristics. IPT weights were calculated as the inverse of this probability and stabilized by multiplying by the marginal probability of being in the treatment group actually observed (22).

Pooled logistic regression was used to estimate probabilities at fixed 7-day intervals across follow-up for not dying and separately for not discontinuing or switching from the index treatment. The inverse of these estimates was used to create IPC weights. The second set of censoring weights was used only in the censored-at-drug-switch-or-discontinuation analyses. In addition to including all baseline covariates, the pooled logistic models also included time-varying covariates for modality, comorbid conditions, disability proxy score, comedications, emergency department and observation stay encounters, inpatient hospitalizations, and days in the hospital. When analyzing the recurrent venous thromboembolism outcome, the first major bleeding event was included as a time-varying covariate; conversely, when analyzing the major bleeding outcome, the first recurrent venous thromboembolism event was included as a time-varying covariate. Time-varying covariates for both recurrent venous thromboembolism and major bleeding were included when analyzing the mortality outcome. IPC weights were stabilized by multiplying the numerator by the probability of remaining uncensored conditional on the baseline treatment category.

Descriptive statistics, both crude and IPT weighted, were calculated to characterize patients in each treatment group. Standardized differences were used to compare baseline characteristics between treatment groups, with a difference of >10% considered to suggest meaningful imbalance (22).

For each outcome of interest, we used Cox proportional hazards models, weighted by the product of the IPT and IPC weights, to estimate marginal hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for the association of apixaban versus warfarin (21). Analyses were conducted in parallel in terms of both analytic method (ITT and censored-at-drug-switch-or-discontinuation) and length of follow-up (6 and 3 months). The ITT analysis with 6 months of follow-up was designated, a priori, as the primary analysis.

Finally, we also performed several sensitivity and subgroup analyses, each using the ITT approach. First, we fit a subdistribution hazards model in which death was treated as a competing risk event. Second, we used a longer (1-year) “washout period” to reduce the likelihood of including prevalent anticoagulant users. Third, we excluded individuals with a history of atrial fibrillation in the 6-month baseline period. Fourth, we eliminated individuals with any claims for a venous thromboembolism during an extended 12-month baseline period. Fifth, we used an alternative bleeding end point consisting of fatal and/or cerebral bleeding. Sixth, we conducted analyses stratified by type of venous thromboembolism (deep venous thrombosis only versus pulmonary embolism); setting of initial venous thromboembolism diagnosis (inpatient versus outpatient); vascular access type (among patients receiving maintenance dialysis only; catheter, graft, or fistula); recent major surgery or trauma; active cancer or chemotherapy; and use of prescription antiplatelet agents. Finally, we estimated net clinical benefit, which consisted of a combination of recurrent venous thromboembolism and fatal and/or cerebral bleeding.

Compliance and Protection of Human Research Participants

A waiver of informed consent was granted by the institutional review board at Hennepin Healthcare. Data use agreements between the Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases were in place.

Results

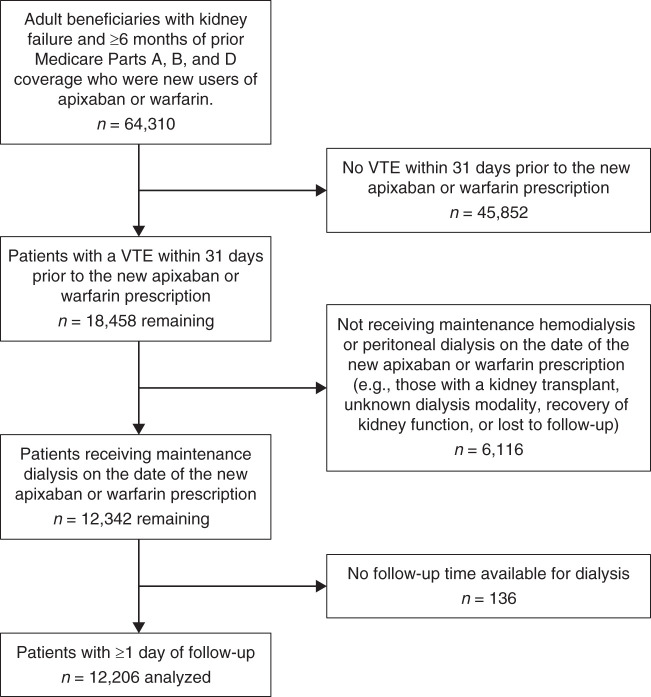

Construction of the study cohort is shown in Figure 1. The final analytic sample included 12,206 adult Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with kidney failure and receiving maintenance dialysis who were new users of apixaban or warfarin following a venous thromboembolism diagnosis between September 1, 2014 and December 31, 2018. Warfarin and apixaban were prescribed in 74% and 26% of patients, respectively. Overall, mean age was 63±14 years, and 53% were women. By race, 50% were White and 46% were Black. Crude baseline characteristics and standardized differences are shown in Supplemental Table 4, and corresponding values after incorporating IPT weights (i.e., reflecting the pseudopopulation) are shown in Table 1. In the pseudopopulation, standardized differences between treatment groups were uniformly <10%. Patterns of drug use over time (discontinuation or drug switching) are shown in Supplemental Table 5, and reasons for the end of follow-up for the ITT analysis are shown in Supplemental Table 6.

Figure 1.

Construction of the study cohort. VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Table 1.

Inverse probability of treatment–weighted baseline characteristics and standardized differences for the analytic sample

| Characteristic | Treatment Group | Standardized Differencea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warfarin | Apixaban | ||

| n | 9086 | 3130 | |

| Age, yr, % | |||

| 18–44 | 1164 (13) | 410 (13) | 0.0 |

| 45–64 | 3396 (37) | 1163 (37) | 0.5 |

| 65–74 | 2506 (28) | 869 (28) | −0.4 |

| 75–79 | 919 (10) | 318 (10) | −0.2 |

| 80+ | 1100 (12) | 379 (12) | 0.0 |

| Women, % | 4836 (53) | 1660 (53) | 0.4 |

| Race, % | |||

| White | 4569 (50) | 1569 (50) | 0.3 |

| Black | 4187 (46) | 1446 (46) | −0.2 |

| Other | 330 (4) | 116 (4) | −0.3 |

| Urban residence, % | 7274 (80) | 2500 (80) | 0.5 |

| Medicaid coverage, % | 5389 (59) | 1867 (60) | −0.7 |

| Low-income subsidy, % | 6549 (72) | 2267 (72) | −0.8 |

| Modality/vascular access, % | |||

| HD catheter | 4399 (48) | 1520 (49) | −0.3 |

| HD AVG | 1392 (15) | 473 (15) | 0.5 |

| HD AVF | 2756 (30) | 957 (31) | −0.3 |

| PD | 530 (6) | 180 (6) | 0.4 |

| Time with kidney failure, % | |||

| 0 to <6 mo | 1578 (17) | 555 (18) | −1.0 |

| 6 to <12 mo | 649 (7) | 227 (7) | −0.5 |

| 1 to <3 yr | 2179 (24) | 739 (24) | 0.9 |

| 3 to <5 yr | 1586 (18) | 547 (18) | −0.1 |

| 5 to <8 yr | 1595 (18) | 553 (18) | −0.3 |

| ≥8 yr | 1499 (17) | 509 (16) | 0.7 |

| Primary cause of kidney failure, % | |||

| Diabetes | 4176 (46) | 1451 (46) | −0.8 |

| Hypertension | 2808 (31) | 962 (31) | 0.4 |

| GN | 842 (9) | 284 (9) | 0.7 |

| Other | 1260 (14) | 434 (14) | 0.0 |

| VTE type, % | |||

| DVT only | 6711 (74) | 2304 (74) | 0.6 |

| PE with or without DVT | 2376 (26) | 827 (26) | −0.6 |

| Provoking VTE factors, % | |||

| Surgery | 2173 (24) | 756 (24) | −0.6 |

| Institutional stay of ≥3 d | 4740 (52) | 1656 (53) | -1.5 |

| Active cancer or chemotherapy | 1256 (14) | 435 (14) | −0.2 |

| Comorbid conditions, % | |||

| Heart failure | 5384 (59) | 1866 (60) | −0.7 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2127 (23) | 731 (23) | 0.2 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2119 (23) | 746 (24) | −1.2 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 3583 (39) | 1239 (40) | −0.3 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3791 (42) | 1313 (42) | −0.4 |

| Peptic ulcer | 373 (4) | 132 (4) | −0.6 |

| Liver disease | 1301 (14) | 452 (14) | −0.3 |

| Coagulopathy | 2293 (25) | 797 (26) | −0.5 |

| Alcohol abuse | 300 (3) | 108 (4) | −0.9 |

| Tobacco use | 4176 (46) | 1432 (46) | 0.4 |

| History of falls | 1657 (18) | 570 (18) | 0.1 |

| Disability proxy score, % | |||

| ≤0 | 2124 (23) | 718 (23) | 1.0 |

| 1–2 | 2415 (27) | 825 (26) | 0.5 |

| 3–4 | 2054 (23) | 708 (23) | 0.0 |

| 5–6 | 1420 (16) | 497 (16) | −0.7 |

| ≥7 | 1073 (12) | 382 (12) | −1.2 |

| Medication use on index date, % | |||

| Antidiabetic | 2184 (24) | 764 (24) | −0.8 |

| Antihypertensive | 3519 (39) | 1205 (38) | 0.5 |

| Antiarrhythmic | 494 (5) | 174 (6) | −0.5 |

| Statin | 3324 (37) | 1144 (37) | 0.1 |

| Antiplatelet | 1236 (14) | 418 (13) | 0.7 |

| NSAID | 120 (1) | 42 (1) | −0.3 |

| Corticosteroid | 588 (6) | 203 (6) | 0.0 |

| SSRI/SNRI | 1421 (16) | 490 (16) | 0.0 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 2747 (30) | 954 (30) | −0.5 |

| Antineoplastic | 259 (3) | 88 (3) | 0.3 |

| ED/observation visits, mean (SD) | 1.7 (2.8) | 1.7 (2.6) | 0.0 |

| Inpatient visits, mean (SD) | 2.4 (1.8) | 2.4 (1.9) | −1.7 |

| Hospitalization d, mean (SD) | 23.7 (21.4) | 24.9 (26.9) | −4.9 |

| Hospitalization d, median (IQR) | 17 (9 − 31) | 16 (7 − 33) | − |

The analytic sample represents the “pseudopopulation” after incorporating stabilized inverse probability of treatment weights. HD, hemodialysis; AVG, arteriovenous graft; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; PD, peritoneal dialysis; VTE, venous thromboembolism; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SSRI, serotonin selective reuptake inhibitor; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; ED, emergency department; IQR, interquartile range.

The standardized difference (reported as a percentage) represents the difference in means or proportions of the two groups scaled by the pooled SD.

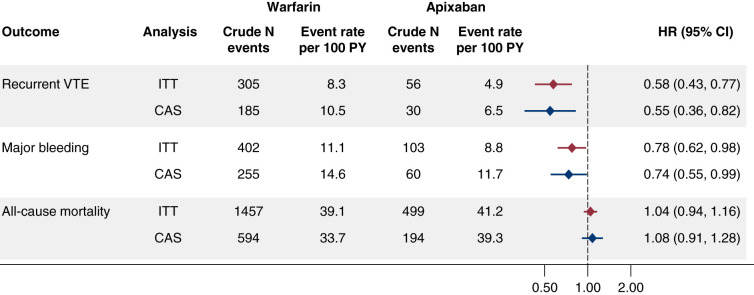

Event rates and HRs estimated using IPT and IPC weighting for the primary analysis (i.e., the 6-month ITT analysis) are shown in Figure 2. In the 6 months following the first prescription for apixaban or warfarin, there were a total of 361 recurrent venous thromboembolism events, 505 major bleeding events, and 1956 all-cause deaths. In terms of major bleeding events (reporting of which is governed by Medicare policy on suppression of small cell sizes), among warfarin users, 70% were gastrointestinal, 13% were cerebral, and 16% involved another site; among apixaban users, 74% were gastrointestinal, <11% were cerebral, and >16% involved another site. Compared with warfarin, use of apixaban was associated with lower risks of both recurrent venous thromboembolism (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.43 to 0.77) and major bleeding (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.62 to 0.98). However, there was no difference between apixaban and warfarin in terms of risk of all-cause death (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.94 to 1.16). Corresponding HRs for the 6-month censored-at-drug-switch-or-discontinuation analysis (Figure 2) and for the ITT and censored-at-drug-switch-or-discontinuation analyses limited to a shorter (3-month) follow-up (Supplemental Figure 1) were all highly similar to the primary analysis.

Figure 2.

Comparisons, adjusted using the inverse probability of treatment (IPT) and the inverse probability of censoring (IPC) weighting for sociodemographic factors, comorbid conditions, disability proxy score, concomitant medications, and health care utilization, for apixaban versus warfarin in the 6-month follow-up analysis. CAS, censored-at-drug-switch-or-continuation; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; ITT, intention-to-treat; PY, person-years.

In Table 2, we present results from six sensitivity analyses, including the calculation of net clinical benefit. The results of these analyses were generally unchanged in comparison with the primary analysis.

Table 2.

Hazard ratios for the sensitivity analyses (intention-to-treat; 6-month follow-up)

| Analysis and Outcome | Apixaban | Warfarin | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N Events | Event Rate per 100 Person-yr | N Events | Event Rate per 100 Person-yr | ||

| Death as a competing event | |||||

| Recurrent VTE | 56 | 4.9 | 305 | 8.3 | 0.57 (0.43 to 0.77) |

| Major bleeding | 103 | 8.8 | 402 | 11.1 | 0.77 (0.61 to 0.96) |

| 1-yr washout period | |||||

| Recurrent VTE | a | 4.8 | 271 | 8.3 | 0.56 (0.41 to 0.77) |

| Major bleeding | a | 9.0 | 368 | 11.5 | 0.77 (0.60 to 0.97) |

| All-cause mortality | 465 | 42.4 | 1321 | 40.0 | 1.05 (0.94 to 1.17) |

| No history of atrial fibrillation | |||||

| Recurrent VTE | a | 6.0 | 249 | 8.9 | 0.66 (0.47 to 0.90) |

| Major bleeding | 65 | 7.3 | 293 | 10.7 | 0.67 (0.51 to 0.89) |

| All-cause mortality | 313 | 34.9 | 942 | 33.0 | 1.05 (0.92 to 1.20) |

| No history of VTE | |||||

| Recurrent VTE | 33 | 4.8 | 192 | 8.2 | 0.56 (0.38 to 0.83) |

| Major bleeding | 67 | 7.9 | 258 | 11.3 | 0.68 (0.51 to 0.89) |

| All-cause mortality | 315 | 39.8 | 890 | 37.6 | 1.05 (0.91 to 1.20) |

| Alternative bleeding end point | |||||

| Fatal and/or cerebral bleeding | 16 | 1.3 | 79 | 2.2 | 0.57 (0.33 to 0.99) |

| Net clinical benefit | |||||

| Combination of recurrent VTE and fatal and/or cerebral bleeding | 72 | 6.3 | 381 | 10.6 | 0.58 (0.45 to 0.75) |

VTE, venous thromboembolism.

A cell size or the difference in cell size compared with another cell is too small to report (n<11) per the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid reporting rules.

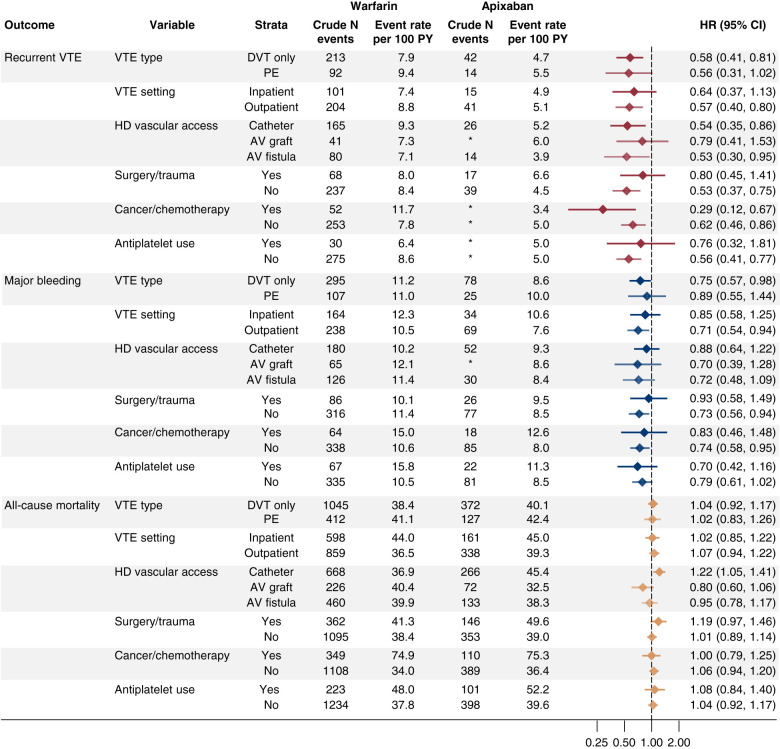

Results from stratified analyses are shown in Figure 3. For the recurrent venous thromboembolism outcome, apixaban compared with warfarin demonstrated HRs <1.0 irrespective of type or setting of the venous thromboembolism diagnosis, hemodialysis vascular access type, presence of recent surgery or trauma, presence of active cancer or use of chemotherapy, or prescription antiplatelet use, although 95% CIs varied widely and often spanned unity. For the major bleeding outcome, the pattern was similar; apixaban uniformly demonstrated HRs <1.0 relative to warfarin. In congruence with the main analyses, there were relatively few differences in mortality between apixaban and warfarin across the subgroups examined, although in patients on hemodialysis utilizing a catheter, the HR for death associated with apixaban relative to warfarin use was 1.22 (95% CI, 1.05 to 1.41).

Figure 3.

Results of the stratified analyses. AV, arteriovenous; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; HD, hemodialysis; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Discussion

In a large cohort of US patients on maintenance dialysis with a recent venous thromboembolism who were new users of oral anticoagulants, we observed that apixaban, compared with warfarin, was associated with a reduced risk of both recurrent venous thromboembolism and major bleeding events. There was no difference in mortality between the treatments. Our findings were highly similar in complementary ITT and censored-at-drug-switch-or-discontinuation analyses over follow-up periods of 3 and 6 months, in multiple sensitivity analyses, and across a host of subgroup analyses. Collectively, these findings suggest that apixaban, compared with warfarin, may be a safer and more effective treatment for venous thromboembolism in patients receiving maintenance dialysis.

It is important to determine whether findings related to the treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients receiving maintenance dialysis are similar to those demonstrated in the general population. In a major clinical trial of apixaban versus warfarin for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in the general population (23), participants randomized to apixaban had a lower risk of major bleeding. In that trial, apixaban was noninferior to warfarin for recurrent venous thromboembolism, but there was no clear signal that it was superior for this outcome.

Previous administrative claims–based observational studies in the general population comparing oral anticoagulants for the primary treatment of venous thromboembolism have consistently reported an association of lower major bleeding risk with apixaban versus warfarin (24–26). Most of these studies also found that apixaban was associated with a lower risk of venous thromboembolism recurrence compared with warfarin (24,25). One study also found that apixaban was associated with lower risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism compared with warfarin (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.47 to 1.00) in the context of secondary prevention (i.e., anticoagulation continuing beyond the initial treatment period), although our goal was to examine only primary prevention because secondary prevention represents a distinct clinical decision-making point that occurs up to 6 months after initial management (27). Furthermore, when limited to the subgroup of patients with kidney disease (ostensibly mostly patients with nondialysis-dependent CKD), the association favored apixaban even more strongly, although with a wide 95% CI (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.12 to 1.01).

The question of apixaban versus warfarin for treatment of venous thromboembolism is relatively understudied, however, in the population undergoing maintenance dialysis. A recent systematic review did not detect any differences between apixaban and warfarin for risk of either recurrent venous thromboembolism or major bleeds (12). However, the studies available to these researchers included, at most, several hundred patients receiving maintenance dialysis and seemed to consist primarily of single-center studies in which medical records (electronic and otherwise) were accessed. Sy et al. (13) recently used a large administrative database of privately insured and Medicare Advantage enrollees to study bleeding risk (among other outcomes) in patients with various stages of kidney disease. They identified <2700 patients with kidney failure on dialysis and found that DOACs, relative to warfarin, were associated with lower bleeding risk for patients whose initial indication was deep venous thrombosis but not pulmonary embolism; pooled results for venous thromboembolism overall were not presented. As such, our findings of a reduced risk of bleeding associated with apixaban are not inconsistent with the findings of Sy et al. (13), although they did not examine risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. Our study has the advantage of including nearly five times more patients with kidney failure given that we were able to identify >12,200 patients receiving maintenance dialysis from the definitive source, namely the comprehensive registry provided by the USRDS. Furthermore, our study did not combine multiple DOACs as the comparator versus warfarin.

Our study has important limitations. First, we studied only US Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries. In particular, the cohort of patients we studied seems to have been quite sick; approximately half were using a catheter and, on average, had spent over 3 weeks in the hospital within the previous 6 months. This may limit our generalizability to other populations. Second, we relied on administrative claims, meaning some degree of misclassification is likely. Nevertheless, the claims-based algorithms used for identifying venous thromboembolism and bleeding events have high positive predictive values (19,28). The Cunningham bleeding algorithm captures only bleeding events that resulted in a hospital admission, meaning that we missed bleeding events that were treated in the emergency department; as a result, these events have a high validity and likely represent the most clinically significant bleeding events. Also, Medicare does not provide specific laboratory test results, such as the international normalized ratio (INR) values, for warfarin users. However, our study was designed to examine how the drugs are being used in actual clinical practice, and the inability to reliably achieve target INR values is an inherent limitation when using warfarin. Further, the ITT analysis—our primary approach—mimics real-world clinical decision making in that the prescriber, when facing the decision to prescribe an oral anticoagulant, does not know how effective warfarin will be in obtaining desired INR values in a given patient. Finally, although we attempted to limit confounding by careful use of both IPT and IPC weighting techniques, residual confounding is almost certainly present, as is the case in all observational studies. However, patient characteristics were very well balanced even prior to IPT weighting. Although a healthy user bias may be present despite our efforts at confounding control, there was no mortality benefit associated with use of apixaban relative to warfarin, suggesting that this may be less of a concern in our study. These limitations may be counterbalanced by several strengths: use of a large cohort encompassing all data presently available for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries receiving dialysis; use of a new-user design; use of complementary ITT and censored-at-drug-switch-or-discontinuation approaches; and use of subgroup and sensitivity analyses to demonstrate robustness of our findings.

In conclusion, we observed that in a large group of US patients on maintenance dialysis receiving an oral anticoagulant for treatment of venous thromboembolism, apixaban was associated with lower risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism and of major bleeding than warfarin; there was no difference in mortality. Although use of DOACs for venous thromboembolism is being studied further in the Venous Thromboembolism in Renally Impaired Patients and Direct Oral Anticoagulants (VERDICT) trial (NCT02664155), it appears that this trial is focused on patients with advanced nondialysis-dependent CKD. A goal for the nephrology community should be to conduct a clinical trial in patients receiving maintenance dialysis, testing apixaban and other indicated DOACs against warfarin following a diagnosis of a venous thromboembolism.

Disclosures

C.A. Herzog reports consultancy agreements with AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Corvidia, DiaMedica, FibroGen, Janssen, Merck, NxStage, Pfizer, Relypsa, Sanifit, and the University of Oxford; stock only (no other ownership role) in Boston Scientific, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, General Electric, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Pfizer; research funding from Amgen, AstraZeneca, the Bristol-Myers Squibb-Pfizer alliance (the ARISTA investigator-initiated research program), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK; National Institutes of Health [NIH]), Relypsa, and the University of British Columbia; honoraria from the American College of Cardiology (nonprofit) and writing royalties from UpToDate; serving on the American Heart Journal editorial board; and other interests or relationships as a Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes Planning Committee Cochair for the “CKD, Heart, and Vasculature” conference series, as a participant in various nephrology-related controversies conferences, and with the American Society of Nephrology (ASN; Kidney Health Initiative workgroups). N.S. Roetker reports research funding from Amgen, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Merck, and NIH. E.D. Weinhandl reports grant/research support from NIH (NIDDK); consultancy agreements with Fresenius Medical Care North America, Outset Medical, and Quanta Dialysis Technologies; serving on the advisory board of Home Dialyzors United and on the board of directors of the Medical Education Institute; and other interests or relationships with the University of Minnesota. J.B. Wetmore reports ad hoc consulting for the Bristol-Myers Squibb-Pfizer alliance; research funding from ACADIA, Amgen, AstraZeneca, the Bristol-Myers Squibb-Pfizer alliance (the American Thrombosis Investigator Initiated Research Program [ARISTA]), Genentech, Merck, NIH (NIDDK), OPKO Health, and Relypsa; honoraria from Aurinia (for advisory board activities as noted), the Bristol-Myers Squibb-Pfizer alliance, and Reata; participating on occasion on Bristol-Myers Squibb-Pfizer alliance ad hoc advisory boards; and honoraria for educational activities (Continuing Medical Education eligible) for NephSAP (ASN) and Healio. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The data reported here have been supplied by USRDS.

The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Treatment Options for Venous Thromboembolism in Patients Receiving Dialysis,” on pages 623–625.

Authors Contributions

N.S. Roetker and J.B. Wetmore conceptualized the study; H. Yan was responsible for data curation; J.B. Wetmore, C.A. Herzog, H. Yan, J.L. Reyes, E.D. Weinhandl, and N.R. Roetker were responsible for formal analysis; J.B. Wetmore, C.A. Herzog, and N. S. Roetker provided supervision; J.B. Wetmore and N.S. Roetker wrote the original draft; and J.B. Wetmore, C.A. Herzog, H. Yan, J.L. Reyes, E.D. Weinhandl, and N.S. Roetker reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

Data for this study can be provided, free of charge, to qualified United States–based investigators from USRDS after completion and approval of a data use agreement with the USRDS Project Officer at the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.14021021/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Figure 1. Comparisons adjusted using IPT and IPC weighting for sociodemographic factors, comorbid conditions, disability proxy score, concomitant medications, and health care utilization for apixaban versus warfarin in the 3-month follow-up analysis.

Supplemental Material. Approaches used to determine the disability proxy score.

Supplemental Table 1. ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes used to identify venous thromboembolism.

Supplemental Table 2. Diagnosis-related group codes used to identify recent hospitalization for surgery or trauma.

Supplemental Table 3. HCPCS and ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes used to define the disability proxy score.

Supplemental Table 4. Baseline characteristics of the study sample prior to inverse probability of treatment weighting.

Supplemental Table 5. Pattern of drug discontinuation or switching over time.

Supplemental Table 6. Reasons for the end of follow-up for the ITT analysis.

References

- 1.Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Cheng S, Delling FN, Elkind MSV, Evenson KR, Ferguson JF, Gupta DK, Khan SS, Kissela BM, Knutson KL, Lee CD, Lewis TT, Liu J, Loop MS, Lutsey PL, Ma J, Mackey J, Martin SS, Matchar DB, Mussolino ME, Navaneethan SD, Perak AM, Roth GA, Samad Z, Satou GM, Schroeder EB, Shah SH, Shay CM, Stokes A, VanWagner LB, Wang NY, Tsao CW; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee : Heart disease and stroke statistics-2021 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 143: e254–e743, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahmoodi BK, Gansevoort RT, Næss IA, Lutsey PL, Brækkan SK, Veeger NJ, Brodin EE, Meijer K, Sang Y, Matsushita K, Hallan SI, Hammerstrøm J, Cannegieter SC, Astor BC, Coresh J, Folsom AR, Hansen JB, Cushman M: Association of mild to moderate chronic kidney disease with venous thromboembolism: Pooled analysis of five prospective general population cohorts. Circulation 126: 1964–1971, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuan S, Bruzelius M, Larsson SC: Causal effect of renal function on venous thromboembolism: A two-sample Mendelian randomization investigation. J Thromb Thrombolysis 53: 43–50, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar G, Sakhuja A, Taneja A, Majumdar T, Patel J, Whittle J, Nanchal R; Milwaukee Initiative in Critical Care Outcomes Research (MICCOR) Group of Investigators : Pulmonary embolism in patients with CKD and ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1584–1590, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu HY, Liao KM: Increased risk of deep vein thrombosis in end-stage renal disease patients. BMC Nephrol 19: 204, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wattanakit K, Cushman M: Chronic kidney disease and venous thromboembolism: Epidemiology and mechanisms. Curr Opin Pulm Med 15: 408–412, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, Blaivas A, Jimenez D, Bounameaux H, Huisman M, King CS, Morris TA, Sood N, Stevens SM, Vintch JRE, Wells P, Woller SC, Moores L: Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 149: 315–352, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortel TL, Neumann I, Ageno W, Beyth R, Clark NP, Cuker A, Hutten BA, Jaff MR, Manja V, Schulman S, Thurston C, Vedantham S, Verhamme P, Witt DM, D Florez I, Izcovich A, Nieuwlaat R, Ross S, J Schünemann H, Wiercioch W, Zhang Y, Zhang Y: American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Blood Adv 4: 4693–4738, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lutsey PL, Walker RF, MacLehose RF, Alonso A, Adam TJ, Zakai NA: Direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin for venous thromboembolism treatment: Trends from 2012 to 2017. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 3: 668–673, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan KE, Edelman ER, Wenger JB, Thadhani RI, Maddux FW: Dabigatran and rivaroxaban use in atrial fibrillation patients on hemodialysis. Circulation 131: 972–979, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siontis KC, Zhang X, Eckard A, Bhave N, Schaubel DE, He K, Tilea A, Stack AG, Balkrishnan R, Yao X, Noseworthy PA, Shah ND, Saran R, Nallamothu BK: Outcomes associated with apixaban use in patients with end-stage kidney disease and atrial fibrillation in the United States. Circulation 138: 1519–1529, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung CYS, Parikh J, Farrell A, Lefebvre M, Summa-Sorgini C, Battistella M: Direct oral anticoagulant use in chronic kidney disease and dialysis patients with venous thromboembolism: A systematic review of thrombosis and bleeding outcomes. Ann Pharmacother 55: 711–722, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sy J, Hsiung JT, Edgett D, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Streja E, Lau WL: Cardiovascular and bleeding outcomes with anticoagulants across kidney disease stages: Analysis of a national US cohort. Am J Nephrol 52: 199–208, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wetmore JB, Roetker NS, Yan H, Reyes JL, Herzog CA: Direct-acting oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in Medicare patients with chronic kidney disease and atrial fibrillation. Stroke 51: 2364–2373, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States Renal Data System : 2021 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2021. Available at: https://adr.usrds.org/2021. Accessed on March 21, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webster-Clark M, Ross RK, Lund JL: Initiator types and the causal question of the prevalent new-user design: A simulation study. Am J Epidemiol 190: 1341–1348, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lund JL, Richardson DB, Stürmer T: The active comparator, new user study design in pharmacoepidemiology: Historical foundations and contemporary application. Curr Epidemiol Rep 2: 221–228, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, Saunders LD, Beck CA, Feasby TE, Ghali WA: Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 43: 1130–1139, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham A, Stein CM, Chung CP, Daugherty JR, Smalley WE, Ray WA: An automated database case definition for serious bleeding related to oral anticoagulant use. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 20: 560–566, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernán MA, Brumback B, Robins JM: Marginal structural models to estimate the causal effect of zidovudine on the survival of HIV-positive men. Epidemiology 11: 561–570, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buchanan AL, Hudgens MG, Cole SR, Lau B, Adimora AA; Women’s Interagency HIV Study : Worth the weight: Using inverse probability weighted Cox models in AIDS research. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 30: 1170–1177, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin PC, Stuart EA: Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med 34: 3661–3679, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, Curto M, Gallus AS, Johnson M, Masiukiewicz U, Pak R, Thompson J, Raskob GE, Weitz JI; AMPLIFY Investigators : Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 369: 799–808, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weycker D, Wygant GD, Guo JD, Lee T, Luo X, Rosenblatt L, Mardekian J, Atwood M, Hanau A, Cohen AT: Bleeding and recurrent VTE with apixaban vs warfarin as outpatient treatment: Time-course and subgroup analyses. Blood Adv 4: 432–439, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo JD, Rajpura J, Hlavacek P, Keshishian A, Sah J, Delinger R, Mu Q, Mardekian J, Russ C, Okano GJ, Rosenblatt L: Comparative clinical and economic outcomes associated with warfarin versus apixaban in the treatment of patients with venous thromboembolism in a large U.S. commercial claims database. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 26: 1017–1026, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo JD, Hlavacek P, Rosenblatt L, Keshishian A, Russ C, Mardekian J, Ferri M, Poretta T, Yuce H, McBane R: Safety and effectiveness of apixaban compared with warfarin among clinically-relevant subgroups of venous thromboembolism patients in the United States Medicare population. Thromb Res 198: 163–170, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zakai NA, Walker RF, MacLehose RF, Koh I, Alonso A, Lutsey PL: Venous thrombosis recurrence risk according to warfarin versus direct oral anticoagulants for the secondary prevention of venous thrombosis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 5: e12575, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanfilippo KM, Wang TF, Gage BF, Liu W, Carson KR: Improving accuracy of International Classification of Diseases codes for venous thromboembolism in administrative data. Thromb Res 135: 616–620, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.