Abstract

Objective:

To examine the possible association between diaper need, difficulty affording an adequate amount of diapers, and pediatric care visits for urinary tract infections (UTIs) and diaper dermatitis (DD).

Study design:

This cross-sectional analysis using nationally representative survey data collected July-August 2017 using a web-based panel, examined 981 parents of children between 0-3 years old in the United States (response rate, 94%). Survey weighting for differential probabilities of selection and nonresponse was used to estimate the prevalence of diaper need and to perform multivariable logistic regression of the association between parent reported diaper need and visits to the pediatrician for diaper rash or urinary tract infections within the past 12-months.

Results:

An estimated 36% of parents endorsed diaper need. Both diaper need (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.37; 95% CI 1.69–3.31) and visiting organizations to receive diapers (aOR 2.14; 95% CI 1.43–3.21) were associated with DD visits. Similar associations were found for diaper need (aOR 2.63; 95% CI 1.54–4.49) and visiting organizations to receive diapers (aOR 4.50; 95% CI 2.63–7.70) for UTI visits.

Conclusions:

Diaper need is common and associated with increased pediatric care visits. These findings suggest pediatric provider and policy interventions decreasing diaper need could improve child health and reduce associated health care utilization.

Keywords: Social determinants of health, Poverty, Diaper bank, Policy, Health care utilization, Child Health

Introduction

One child is estimated to use between 4600 and 4800 disposable diapers during the first three years of life,1 costing families between $945 and $1,500 annually.2 Although diapers are a basic need of infants and vital for good health, research estimates that 1 out of 3 families experience diaper need. 3,4 Diaper need is the gap between the number of diapers required for infants to stay clean and the number of diapers a family can afford without cutting back on other basic needs.5 Diapering an infant is a primary parental activity, but for low-income families, diapering imposes a significant financial burden. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported the poorest 20% of families spent almost 14% of their 2014 household income on diapers.6 Government assistance programs such as Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), cannot be used to purchase diapers. In 2013, the first peer-reviewed published study quantifying diaper need among low-income women in an urban area found that 28% of women reported diaper need and of those women, 27% reported putting off changing a child’s diapers when their supply was running short, or “stretching” diapers.3 Since this paper was published, additional research has supported the negative impact of diaper need on a family’s economic success and maternal mental health,7 yet no research has directly linked diaper need with child health outcomes.

Two child health outcomes associated with the frequency of diaper changes and thus diaper need, are urinary tract infections (UTIs) and diaper dermatitis (DD).8–11 DD is a general term used to describe various inflammatory reactions of the skin within the diaper region and is often related to irritant contact on the skin, such as moisture from urine and feces and friction from diapers themselves, or infection, including candidal dermatitis.12–14 DD is a common reason for visits to the pediatrician15, and cases can vary in severity from mild to severe; however, most cases rarely cause long-term health problems for the infant but cause appreciable distress for both the infant and caregiver with prevalence rate estimates between 8-12% at any given time.16,17 The American Academy of Dermatology recommends changing an infant’s diaper every 1 to 3 hours during the day, or as soon as the diaper is soiled, and at least once per night to prevent DD.18

UTI is one of the most common serious bacterial infections with prevalence rate estimates between ~5.0% and 7.0% in infants 2-years old or younger.19–22 However, UTIs are challenging to detect in very young children;23 therefore, prevalence may be underestimated.24 There is an association between untreated UTI in early childhood and serious short- and long-term health complications, including renal scarring25–28 (even in infants with normal urinary tracts), 29 hypertension,30 preeclampsia,31 and renal failure.32

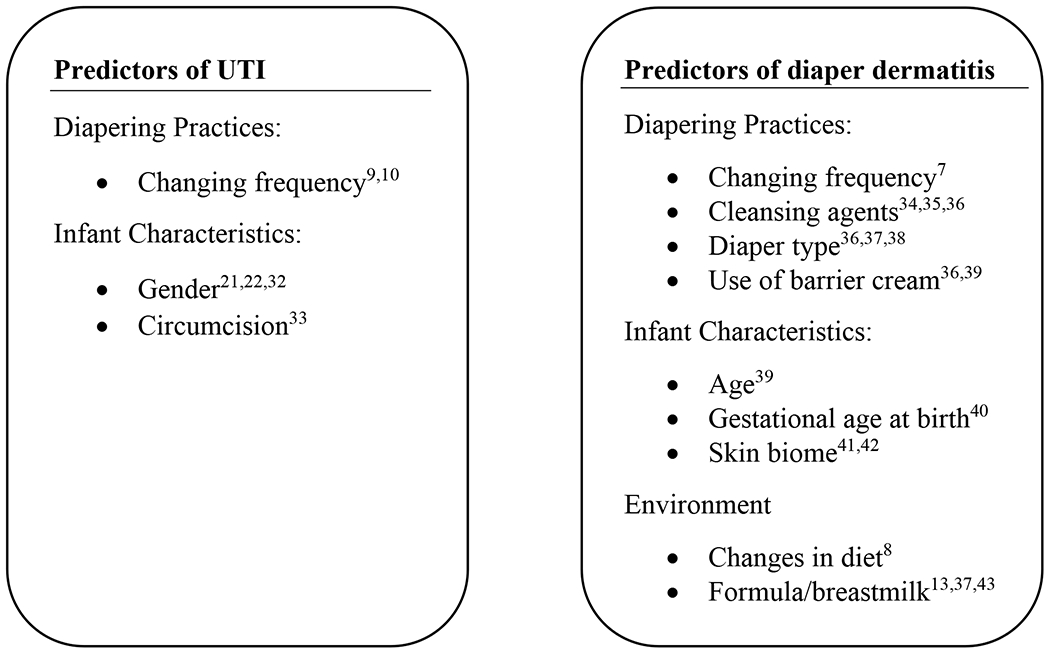

Not only do UTIs and DD have multiple predictors of risk (Figure 1 illustrates these risk factors),8–11,14,22–23,33–44 but they also share a risk factor that is shaped by conditions of poverty–diaper need. Diaper need impacts the frequency of diaper changing such that families endorsing diaper need may be less likely to change their children as frequently as they desire. A significant association between frequency of diaper change and DD is well documented in the literature,8, 9 and more recent research has elucidated an inverse relationship between the frequency of diaper changes and risk of UTI in infants.10, 11

Figure 1.

Predictors of Urinary Tract Infection and Diaper Dermatitis in Children

To further explore the relationship between diaper need and child health outcomes, this study uses nationally representative data to examine whether diaper need was associated with pediatric health care visits for DD and UTI.

Methods

Participants and Study Design

This study is a secondary data analysis of a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of parents commissioned by Kimberly-Clark. Survey Sampling International, a top global digital data collection company, was contracted to recruit a representative random sample of the general parent population by age, gender, and income (n=1000) from their large web-based respondent panels; the margin of error for this sample was ±3% at the 95% confidence level. A study invitation was issued to randomly selected members of the web-based panel. Participants were included if they were 18 years old or older, had children between 0-3 years old, were the primary or shared caregiver in the household, and were involved in changing the diaper of children between 0-3 years old. Edelman Intelligence, a full-service consumer research firm, conducted cross-sectional online surveys (approximately 15 minutes to complete) from July to August 2017. The response rate was 94% (1064 initial, 64 drop out, 1000 complete surveys). Nineteen participants were excluded because they were not parents of a child, leaving a final analytic sample of 981. All research procedures were conducted in accordance with MRA Marketing Research Standards and the CASRO Code of Standards and Ethics. Secondary data analytic procedures were approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Covariates

Sociodemographics

Demographic characteristics including sex, race (self-identified by participants), relationship status, caregiving responsibility, socioeconomic status indices, geographic location, participation in SNAP, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and WIC were collected.

Diaper Need

Participants were considered to have diaper need if they responded positively to one of the following statements: (1) I currently do not have enough diapers to keep the child(ren) in my household clean, dry and healthy; (2) I find it difficult to afford buying diapers for the child(ren) in my household; and (3) I frequently find myself running out of diapers for the child(ren) in my household.

Diaper receipt

Participants were asked if they visited a variety of locations to obtain diapers. Locations included food banks, churches, synagogues and other places of worship, early childhood education programs (e.g., Head Start), hospitals or health clinics, homeless shelters, or other community based organizations and non-profit organizations. Those who visited at least one of these locations were classified as “visited organization to get diapers.”

Outcome Variables

Diaper Dermatitis and Urinary Tract Infections

The two outcome measures were pediatric care visits for diaper dermatitis and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Parents reported the number of times in the past year they took their child to see a health care professional for diaper rash from zero to more than five times. Participants could also answer not applicable. The same question was asked for urinary tract infections. Responses were dichotomized to zero and one or more times for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were weighted for differential probabilities of selection and nonresponse to produce nationally representative estimates. To test for the association between sociodemographic and diaper variables and diaper rash or UTI, chi-square and t tests were used. Multivariate logistic regression models including significant covariates from bivariate analyses (P < .05) were used to examine the association between variables and use of pediatric care for diaper rash and UTI. To ensure that we did not exclude relevant covariates in our multivariate logistic regression models, we did exploratory analysis with a more liberal P value (P < .1) in bivariate analyses. Collinearity statistics were acceptable (variance inflation factor < 10). Analyses were performed by using R 3.4.4 and Stata 13.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas). All tests were set to P value <.05.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Overall, 55.9% of parents self-designated as female. The majority of participants were Caucasian (72.9% [n = 754]), but African Americans (11.3% [n = 87]), Asian (5.8% [n = 57]), and Native American (2.1% [n = 18]) populations were represented. Nationally, 35.9% (n = 362) of respondents reported diaper need, 32.1% (n = 292) of parents brought their child to a healthcare provider for diaper rash and 11.7% (n = 109) of parents brought their child to a healthcare provider for a UTI. Demographics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Caregivers of Young Children from a 2017 Nationally Representative Web-based Panel Survey

| Characteristics | Total Na (%)b |

Visited clinician for Diaper rash na (%)b |

P Value | Visited clinician for UTI na (%)b |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 981 (100) | 292 (100) | 109 (100) | ||

| Gender | .09 | <.001 | |||

| Female | 578 (55.9) | 160 (51.9) | 43 (36.9) | ||

| Male | 403 (44.1) | 132 (48.1) | 66 (63.1) | ||

| Age, mean (SE), y | 32.28 (0.22) | 31.69 (0.41) | .09 | 31.7 (0.67) | .37 |

| Race | .30 | .77 | |||

| White or Caucasian | 754 (72.9) | 216 (70.3) | 87 (76.0) | ||

| Black or African American | 87 (11.3) | 31 (13.4) | 11 (12.4) | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 57 (5.8) | 20 (6.1) | 6 (5.5) | ||

| Native American or Alaskan Native | 18 (2.1) | 7 (2.9) | 1 (2.2) | ||

| Mixed racial background | 35 (4.4) | 7 (2.8) | 2 (1.9) | ||

| Other | 30 (3.4) | 11 (4.5) | 2 (2.0) | ||

| Education level | .07 | .06 | |||

| High school graduate or less | 188 (22.9) | 51 (22.9) | 18 (19.6) | ||

| Some college/ Associate’s degree/technical school | 328 (30.2) | 92 (30.2) | 25 (20.9) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 292 (25.6) | 77 (25.6) | 36 (35.0) | ||

| Master’s degree/ Post-graduate or professional degree | 173 (21.3) | 56 (21.3) | 26 (24.5) | ||

| Employment status | .22 | .001 | |||

| Employed | 673 (70.5) | 210 (73.4) | 89 (83.4) | ||

| Unemployed | 308 (29.5) | 82 (26.6) | 20 (16.6) | ||

| Household income, $ | |||||

| < $25,000 | 155 (17.6) | 54 (20.4) | .41 | 14 (14.6) | .34 |

| $25,000 to $34,999 | 95 (8.8) | 30 (9.4) | 5 (4.4) | ||

| $35,000 to $49,999 | 141 (13.5) | 46 (14.5) | 14 (12.1) | ||

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 207 (17.8) | 51 (14.6) | 26 (19.1) | ||

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 145 (14.0) | 49 (15.3) | 24 (20.7) | ||

| $100,000 to $149,999 | 154 (15.8) | 37 (13.1) | 18 (17.9) | ||

| $150,000 or more | 77 (12.4) | 22 (12.7) | 7 (11.2) | ||

| Partnered | .007 | .74 | |||

| Yes | 857 (87.7) | 244 (82.7) | 97 (88.9) | ||

| No | 124 (13.2) | 48 (17.3) | 12 (11.1) | ||

| Caregiving responsibility | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Primary caregiver | 546 (54.3) | 192 (64.7) | 80 (73.2) | ||

| Share responsibility with someone else | 435 (45.7) | 100 (35.3) | 29 (26.8) | ||

| Geographic location | .02 | .003 | |||

| Urban | 279 (29.6) | 106 (36.4) | 49 (43.3) | ||

| Suburban | 492 (50.4) | 125 (43.8) | 41 (41.4) | ||

| Rural | 210 (20.0) | 61 (19.8) | 19 (15.3) | ||

| TANF, SNAP, or WIC recipient | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Yes | 649 (66.5) | 134 (56.0) | 59 (52.5) | ||

| No | 332 (33.5) | 158 (44.0) | 50 (47.5) | ||

| Diaper Need | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Yes | 362 (35.9) | 167 (55.3) | 79 (71.3) | ||

| No | 619 (64.1) | 125 (44.7) | 30 (28.7) | ||

| Visited organization to get diapers | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Yes | 190 (19.1) | 187 (65.6) | 69 (60.5) | ||

| No | 791 (80.9) | 105 (44.0) | 40 (39.5) | ||

| Diaper type | .006 | .001 | |||

| Disposable only | 868 (91.8) | 244 (84.2) | 80 (73.5) | ||

| Cloth only | 34 (3.3) | 19 (5.7) | 16 (13.7) | ||

| Mix of disposable and cloth | 77 (7.6) | 28 (9.6) | 13 (12.8) | ||

| Other | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | ||

| Took child to healthcare provider for UTI during past year | <.001 | ||||

| One or more times | 109 (11.7) | 78 (27.4) | … | ||

| Never | 809 (88.3) | 192 (72.6) | … | ||

| Took child to healthcare provider for diaper rash during past year | <.001 | ||||

| One or more times | 292 (32.1) | … | 78 (27.4) | ||

| Never | 631 (67.9) | … | 30 (72.6) |

Raw totals vary because of missing values

Sampling weights are applied to account for differential probabilities of selection and differential nonresponse to derive accurate nationally representative estimates

Boldface indicates statistical significance

Associations with diaper need and utilization for child diaper rash and UTIs

Bivariate associations demonstrated that parents who endorsed diaper need or visited an organization to receive diapers had higher proportions of care visits for both DD and UTI (all P < .001). Partnered parents (married or in a civil union/domestic partnership) had higher rates of bringing their child to care for DD compared to non-partnered parents (P = .007). Fathers (P < .001) and employed parents (P = .001) had higher rates of UTI care visits compared to women and unemployed, respectively. Parents who were TANF, SNAP, or WIC recipients had more care visits for both DD and UTI (both P < .001). Geographic location differed such that people living in urban areas had the highest rates of care visits (P = .02, P = .003, respectively). Similarly, DD and UTI groups differed based on the type of diapers participants used (disposable only, cloth only, mix of disposable and cloth, other). Parents using only cloth diapers had higher rates of visits for diaper dermatitis (P = .006), while those using only cloth diapers or a mix of disposable and cloth diapers had more visits for UTI (P = .001).

Multivariate logistic regression results are presented in Table 2 and Table 3. Both diaper need (Odds ratio [OR], 2.37, 95% CI, 1.69-3.31, P < .001) and visiting organizations to get diapers (OR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.43-3.21, P < .001) were strongly associated with higher odds of DD visits. Participants who completed some college/associate’s/technical school and bachelor’s degree were less likely to bring their child in for DD (OR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.12-0.78, P = .01 and OR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.14-0.92, P = .03, respectively). Parents’ caregiving responsibility and diaper type were not associated with DD visits.

Table 2.

Association of Health Care Utilization for Diaper Rash Relating to Demographic and Diapering Variables (n = 922)

| ORb | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education level | |||

| High school graduate or less | Ref | . | |

| Some college/Associate’s degree/technical school | 0.65 | 0.41–1.02 | .06 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 0.76 | 0.47–1.22 | .26 |

| Master’s degree/Post-graduate or professional degree | 1.09 | 0.64–1.87 | .75 |

| Social benefit recipient | 0.94 | 0.64–1.39 | .77 |

| Partnered | 0.80 | 0.51–1.33 | .44 |

| Share caregiving responsibility | 0.76 | 0.55–1.06 | .10 |

| Geographical location | |||

| Urban | Ref | ||

| Suburban | 0.80 | 0.55–1.16 | .25 |

| Rural | 0.94 | 0.61–1.47 | .82 |

| Diaper need | 2.39*** | 1.71–3.35 | <.001 |

| Visited organization to get diapers | 2.19*** | 1.46–3.27 | <.001 |

| Diaper type | |||

| Disposable only | Refa | ||

| Cloth only | 1.49 | 0.69–3.25 | .31 |

| Disposable and cloth | 1.24 | 0.76–2.06 | .39 |

| Other | … | … | … |

Ref, reference

Adjusted models included all other variables in the table

Boldface indicates statistical significance

P < .05

P < .01

P < .001

Table 3.

Association of Health Care Utilization for Urinary Tract Infection Relating to Demographic and Diapering Variables (n = 916)

| ORa | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 2.19** | 1.32–3.63 | .002 |

| Employed | 1.71 | 0.90–3.27 | .10 |

| Social benefit recipient | 0.90 | 0.52–1.54 | .70 |

| Geographical location | |||

| Urban | Ref | ||

| Suburban | 0.82 | 0.48–1.42 | .48 |

| Rural | 0.89 | 0.46–1.75 | .74 |

| Share caregiving responsibility | 0.52* | 0.30–0.91 | .02 |

| Diaper need | 2.63*** | 1.54–4.49 | <.001 |

| Visited organization to get diapers | 4.50*** | 2.63–7.70 | <.001 |

| Diaper type | |||

| Disposable only | Ref | ||

| Cloth only | 2.57* | 1.07–6.20 | .04 |

| Disposable and cloth | 1.43 | 0.69–2.98 | .34 |

| Other | … | … | … |

Adjusted models included all other variables in the table

Boldface indicates statistical significance

P < .05

P < .01

P < .001

Fathers were more likely to bring their child to care for a UTI (OR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.12-0.80, P = .002). Similar to diaper need care visit results, diaper need (OR, 2.63; 95% CI, 1.54-4.49, P < .001) and visiting an organization to get diapers (OR, 4.50; 95% CI, 2.63-7.70, P < .001), were the most important factors associated with UTI care visits. Parents using only cloth diapers were more likely to make UTI care visits (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.07-6.20, P = .04). Parents sharing caregiving responsibility were less likely to bring their child in for UTI (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.30-0.91, P = .02). Employment status and geographical location were not associated UTI visits.

Exploratory analysis

Using a P value < .1 in bivariate analysis, fathers and younger parents were more likely to bring their child to the pediatrician for DD, while no additional covariates were significant for UTI visits compared to P value < .05. However, when the multivariate model with age and gender was compared to the more parsimonious model (i.e., not including age or gender) using the Akaike information criterion (AIC), we found the parsimonious model was more appropriate (lower AIC). Therefore, we elected to keep the original model using P value < .05 for DD.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first nationally representative study of diaper need and its association with pediatric care utilization for DD and UTIs. Although DD and UTIs are among the most common reasons parents seek pediatric care, few studies have examined the role of social factors in their etiology. In this paper, we found that lack of access to diapers, reflected by diaper need and receiving diapers from community organizations, was associated with more visits to a health care provider for both DD and UTIs. A prior non-peer reviewed report of recipients of diapers from diaper banks in Connecticut45 found a lower parent reported incidence of DD, UTI, and associated medical visits. This study adds to the literature by demonstrating similar findings in a nationally representative sample. Further, the current study found this association held when considering potential contributing and confounding factors.

We found that nearly 36% of parents nationwide cannot afford to properly diaper their children. These findings align with two prior studies based in the United States and Canada where a third of mothers reported diaper need.3, 4 Given the high number of patient presentations for DD and UTI, pediatric health care providers should screen for diaper need in addition to providing treatment and education. Screening for social determinants of health has been recommended as part of the Bright Futures Guidelines for pediatric well care visits46 and should include specific questions on diaper need as part of pediatric social determinants of health. However, we acknowledge that screening without access to resources or referrals can cause unintentional harm,47 and the value of screening depends largely on accompanied access to free or very low-cost diapers for families with need. Clinical interventions can support an individual family in meeting this basic need and should accompany larger public health strategies to address diaper need as a social determinant of health.48

Our findings suggest improving access to diapers is one way to decrease the health care utilization for these ailments. Without diapers or emollients, caregivers may be unable to carry out recommended treatment regimens. Unfortunately, many parents are unaware of diaper banks and community organizations which provide free diapers and child hygiene products4 and these organizations remain underfunded. Asking parents if they visit organizations to obtain diapers may help increase clinician knowledge of community resources. These efforts align with the American Academy of Pediatrics recent recommendation to connect families with community resources to help with basic needs.49

Diapers are a basic need of infants and young children, yet government assistance programs for low-income families, namely SNAP and WIC, do not allow for the purchasing of diapers. Given the negative impact of diaper need on child health, we recommend that these programs expand their rosters of allowable expense items to include diapers and legislation similar to the 2015 “Hygiene Assistance for Families of Infants and Toddlers Act” be revisited.50 Despite the Bill not passing the Subcommittee on Human Resources, some states are making incremental progress toward reducing diaper need by providing diapers to families, removing sales tax, and requiring Early Head Start programs to provide diapers to children.51 A recent study found that only a small proportion of low-income families access diapers through community diaper banks and highlights the need for policies at a municipal, state and federal level to address diaper need in low-income families.52 Additionally, the impact of these policies on child outcomes should be further evaluated.

Although not explored in this study, the effects of diaper need on psychological and economic outcomes of families is worth additional study. Diaper need has been associated with maternal depressive symptoms3 and DD is associated with parental anxiety.48 Missing work to bring children to appointments, enforced absence from childcare because of lack of a sufficient supply of diapers, and healthcare expenses, are all possible ways DD and UTIs negatively affect the economic security of families. Economic insecurity in turn, is associated with poor parental mental health.53, 54 While the use of cloth diapers may defray costs for families who have access to free laundry, a previous study found that exclusive use increases the risk of diaper rash.55 We did not find an association between diaper type and diaper rash, but exclusive use of cloth diapers was associated with visits for UTI. This finding should be explored in future studies.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Parents reported visits for their child, and thus reports may be subject to different types of reporting bias or general confounding by parental characteristics, such as knowledge and perceptions about DD and UTI, and it is unclear if DD or UTI was diagnosed during pediatric appointments. Thus, incorporating administrative data from the health record would be beneficial. Also, because this is a cross-sectional study, causal associations cannot be determined. Although the study sample was nationally-representative, because participants were recruited from the web-based panel participants, the results may not generalize to people with limited internet access. The diaper need questionnaire is not validated but was developed with expert input and pilot testing and has been used in multiple studies. Despite these limitations, our study reinforces the importance of a sufficient supply of diapers for child health.

Conclusion

In a nationally representative study, we find that lack of a sufficient supply of diapers increases pediatric care utilization for UTIs and DD. Longitudinal studies, ideally with administrative data, are needed to further assess this relationship.56 Individual, community, and policy interventions are needed to acknowledge, and better address diaper need as a social determinant of health.

Funding Sources:

Funding support for this study was provided by The Annie E. Casey Foundation to M.V.S. The study sponsor did not have any role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication. Kunmi Sobowale is supported by NIMH T32 (MH073517-14).

Abbreviations:

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- DD

Diaper dermatitis

- OR

odds ratio

- SNAP

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

- TANF

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

- UTI

urinary tract infection

- WIC

Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interests to report.

Financial disclosure: The authors of this paper have no financial disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Dey S, Purdon M, Kirsch T, Helbich H, Kerr K, Li L, Zhou S. Exposure Factor considerations for safety evaluation of modern disposable diapers. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2016;81:183–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadler LS, Condon EM, Deng SZ, Ordway MR, Marchesseault C, Miller A, et al. A diaper bank and home visiting partnership: Initial exploration of research and policy questions. Public Health Nursing. 2018;35:135–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith MV, Kruse A, Weir A, Goldblum J. Diaper need and its impact on child health. Pediatrics. 2013;132:253–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raver C, Letourneau N, Scott J, D’Agostino H. Huggies every little bottom study: Diaper need in the US and Canada. Commissioned by Huggies®, a Kimberly-Clark company. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter S, Steefel L. Diaper Need: A Change for Better Health. Pediatric nursing. 2015;41:141–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cashman K The hygiene assistance for families of infants and toddlers act will help the poor pay for diapers. Center for Economic and Policy Research. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobs AW, Hill TD, Tope D, O’Brien LK. Employment transitions, child care conflict, and the mental health of low-income urban women with children. Women’s Health Issues. 2016;26:366–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singalavanija S, Frieden I. Diaper dermatitis. Pediatrics in Review. 1995;16:142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li C, Zhu Z, Dai Y. Diaper dermatitis: a survey of risk factors for children aged 1–24 months in China. Journal of International Medical Research. 2012;40(5):1752–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugimura T, Tananari Y, Ozaki Y, Maeno Y, Tanaka S, Ito S, et al. Association between the frequency of disposable diaper changing and urinary tract infection in infants. Clinical pediatrics. 2009;48:18–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daulay M, Siregar R, Ramayani OR, Supriatmo S, Ramayati R, Rusdidjas R. Association between the frequency of disposable diaper changing and urinary tract infection in children. Paediatrica Indonesiana. 2013;53:70–75. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humphrey S, Bergman J, Au S. Practical management strategies for diaper dermatitis. Skin Therapy Lett. 2006;11:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Odio M, Thaman L. Diapering, diaper technology, and diaper area skin health. Pediatric dermatology. 2014;31:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg R. Etiology and pathophysiology of diaper dermatitis. Advances in dermatology. 1988;3:75–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward DB, Fleischer AB, Feldman SR, Krowchuk DP. Characterization of diaper dermatitis in the United States. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2000;154:943–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Runeman B Skin interaction with absorbent hygiene products. Clinics in dermatology. 2008;26:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Šikić Pogačar M, Maver U, Marčun Varda N, Mičetić-Turk D. Diagnosis and management of diaper dermatitis in infants with emphasis on skin microbiota in the diaper area. International journal of dermatology. 2018;57:265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Academy of Dermatology. Prevent and treat diaper rash with tips from dermatologists. 2014.

- 19.Montini G, Tullus K, Hewitt I. Febrile urinary tract infections in children. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Downs SM. Technical report: urinary tract infections in febrile infants and young children. Pediatrics. 1999;103:e54–e54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wald E Urinary tract infections in infants and children: a comprehensive overview. Current opinion in pediatrics. 2004;16:85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaikh N, Morone NE, Bost JE, Farrell MH. Prevalence of urinary tract infection in childhood: a meta-analysis. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2008;27:302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaikh N, Morone NE, Lopez J, Chianese J, Sangvai S, D’Amico F, et al. Does this child have a urinary tract infection? JAMA. 2007;298:2895–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Brien K, Edwards A, Hood K, Butler CC. Prevalence of urinary tract infection in acutely unwell children in general practice: a prospective study with systematic urine sampling. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e156–e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zorc JJ, Kiddoo DA, Shaw KN. Diagnosis and management of pediatric urinary tract infections. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2005;18(2):417–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vernon SJ, Coulthard MG, Lambert HJ, Keir MJ, Matthews JN. New renal scarring in children who at age 3 and 4 years had had normal scans with dimercaptosuccinic acid: follow up study. BMJ. 1997;315:905–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaikh N, Craig JC, Rovers MM, Da Dalt L, Gardikis S, Hoberman A, et al. Identification of children and adolescents at risk for renal scarring after a first urinary tract infection: a meta-analysis with individual patient data. JAMA pediatrics. 2014;168:893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaikh N, Mattoo TK, Keren R, Ivanova A, Cui G, Moxey-Mims M, et al. Early antibiotic treatment for pediatric febrile urinary tract infection and renal scarring. JAMA pediatrics. 2016;170:848–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shim YH, Lee JW, Lee SJ. The risk factors of recurrent urinary tract infection in infants with normal urinary systems. Pediatric Nephrology. 2009;24:309–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobson SH, Eklöf O, Eriksson CG, Lins L-E, Tidgren B, Winberg J. Development of hypertension and uraemia after pyelonephritis in childhood: 27 year follow up. BMJ. 1989;299:703–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Khatib M, Packham D, Becker G, Kincaid-Smith P. Pregnancy-related complications in women with reflux nephropathy. Clinical nephrology. 1994;41:50–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Bailey R. A long term follow up of adults with reflux nephropathy. The New Zealand medical journal. 1995;108:142–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mårild S, Jodal U. Incidence rate of first-time symptomatic urinary tract infection in children under 6 years of age. Acta Paediatrica. 1998;87:549–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Male circumcision. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e756.22926175 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prasad H, Srivastava P, Verma KK. Diapers and skin care: merits and demerits. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2004;71:907–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borkowski S Diaper rash care and management. Pediatric nursing. 2004;30:467–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adam R Skin care of the diaper area. Pediatric dermatology. 2008;25:427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jordan W, Lawson K, Berg R, Franxman J, Marrer A. Diaper dermatitis: frequency and severity among a general infant population. Pediatric dermatology. 1986;3:198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clark-Greuel JN, Helmes CT, Lawrence A, Odio M, White JC. Setting the record straight on diaper rash and disposable diapers. Clinical pediatrics. 2014;53:23S–26S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atherton DJ. A review of the pathophysiology, prevention and treatment of irritant diaper dermatitis. Current medical research and opinion. 2004;20:645–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalia YN, Nonato LB, Lund CH, Guy RH. Development of skin barrier function in premature infants. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1998;111:320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McLane KM, Bookout K, McCord S, McCain J, Jefferson LS. The 2003 national pediatric pressure ulcer and skin breakdown prevalence survey: a multisite study. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing. 2004;31:168–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yonezawa K, Haruna M, Shiraishi M, Matsuzaki M, Sanada H. Relationship between skin barrier function in early neonates and diaper dermatitis during the first month of life: a prospective observational study. Pediatric dermatology. 2014;31:692–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stamatas GN, Tierney NK. Diaper dermatitis: etiology, manifestations, prevention, and management. Pediatric dermatology. 2014;31:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cartensen F, Gunterh P Better health for children and increased opportunities for families. 2019. https://nationaldiaperbanknetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/The-Social-and-Economic-Impacts-of-the-DIaper-Bank-of-Connecticut.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2020.

- 46.American Acadmey of Pediatrics. Bright Futures: Integrating Social Determinates of Health Into Health Supervision Visits. 2019. https://brightfutures.aap.org/Bright%20Futures%20Documents/BF_Tips_ClinPractice_Tipsheet.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2020.

- 47.Garg A, Boynton-Jarrett R, Dworkin PH. Avoiding the Unintended Consequences of Screening for Social Determinants of Health. JAMA. 2016;316:813–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adalat S, Wall D, Goodyear H. Diaper dermatitis-frequency and contributory factors in hospital attending children. Pediatric dermatology. 2007;24:483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and Child Health in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20160339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Randles J The Diaper Dilemma. Contexts. 2017;16:66–68. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wallace LR, Weir AM, Smith MV. Policy impact of research findings on the association of diaper need and mental health. Women’s Health Issues. 2017;27:S14–S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Massengale KEC, Comer LH, Austin AE, Goldblum JS. Diaper Need Met Among Low-Income US Children Younger Than 4 Years in 2016. American Journal of Public Health. 2020;110:106–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kopasker D, Montagna C, Bender KA. Economic Insecurity: A Socioeconomic Determinant of Mental Health. SSM-Population Health. 2018;6:184–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Masarik AS, Conger RD. Stress and child development: a review of the family stress model. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2017;13:85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu N, Wang X, Odio M. Frequency and severity of diaper dermatitis with use of traditional Chinese cloth diapers: observations in 3-to 9-month-old children. Pediatric dermatology. 2011;28:380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krist AH, Davidson KW, Ngo-Metzger Q, Mills J. Social determinants as a preventive service: US Preventive Services Task Force methods considerations for research. American journal of preventive medicine. 2019;57:S6–S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]