Abstract

This study examines whether disagreeable youth are distinct from aggressive youth, victimized youth, and withdrawn youth. Young adolescents (120 girls and 104 boys, M = 13.59 years old) completed personality and adjustment inventories. Aggression, withdrawal, and victimization scores were derived from peer nominations (N = 807). Cluster analyses identified six groups. Disagreeable youth, aggressive victimized youth, withdrawn victimized youth, and withdrawn youth tended to have worse concurrent peer relations than did agreeable youth and aggressive youth. Disagreeable youth had some of the highest levels of concurrent and prospective adjustment problems, with rates of self-and mother-reported internalizing problems that rivaled withdrawn victimized youth and withdrawn youth, and rates of self-and mother-reported externalizing problems that rivaled aggressive victimized youth and aggressive youth. The findings indicate that low agreeable youth represent a discrete category of adolescents with social and adjustment difficulties.

The Distinctive Difficulties of Disagreeable Youth

Chronic peer difficulties are a marker of maladjustment. Adolescents who fail to navigate the social world present more emotional and behavioral problems than those who are well accepted (Parker, Rubin, Erath, Wojslawowicz, & Buskirk, 2006). Considerable attention has focused on the difficulties of aggressive youth and victimized youth (Graham, Bellmore, & Mize, 2006) and, to a lesser extent, on withdrawn youth (Oh et al., 2008). Unpopularity, however, is probably not limited to adolescents with these attributes. The inverse correlation between agreeableness and peer difficulties makes disagreeable youth strong candidates for consideration (Scholte, van Aken, & van Lieshout, 1997). This raises the question: Are disagreeable youth different from other types of youth who have troubles with peers? We know that there is some overlap among the attributes that predict peer problems, but we do not know whether low agreeableness is a salient feature of a unique group of youth or a trait that covaries with in dices of aggression, victimization, and withdrawal. In the present investigation, cluster analyses were used to identify groups of young adolescents on the basis of personality and reputation-based characteristics, and to evaluate whether disagreeable youth differ from other youth who experience peer difficulties.

Theories addressing the origins of peer troubles tend to focus on traits that undermine dyadic ties and that interfere with group functioning (Hartup, 2009). Youth with attributes that are attractive to friends and that enhance group unity are typically accepted, whereas those who are unsociable and disruptive tend to be rejected. Peer reputations are particularly salient. Peer reports of aggression are correlated with indices of poor peer relations, but these links are moderated by characteristics valued by peers, which explains how attractive, athletic, and socially skilled aggressive children become group leaders and are perceived to be popular even though they are not well accepted (Vaillancourt & Hymel, 2006). Peer reports of victimization resemble aggression, with inverse links to peer acceptance and perceived popularity, but unlike aggressive youth, victimized youth are almost never popular or accepted (Prinstein & Cillessen, 2003). Withdrawn youth are not typically disruptive, but their anxious behavior undercuts positive sentiments shared by group members and thus threatens group cohesion (Rubin, Bowker, & Kennedy, 2009). Like aggression and victimization, peer reports of withdrawal are tied to low peer acceptance; like victimization, withdrawal is also associated with low perceived popularity (Rubin, Chen, & Hymel, 1993). Aggressive youth are more apt to have friends than are victimized youth and withdrawn youth, but the friendships of each are often of lower quality than those of accepted children (Brendgen, Vitaro, Turgeon, & Poulin, 2002; Schneider, 1999). Finally, youth with these attributes share one other important characteristic: Their adjustment prognosis is poor (Prinstein, Rancourt, Guerry, & Browne, 2009). Peer rejection combined with a peer reputation for aggression, victimization, or withdrawal is a recipe for persistent long-term academic, social, and mental health problems.

Agreeableness is a personality dimension that ranges from warm, considerate, and compliant on the high end to antagonistic, rude, and willful on the low end (Graziano & Eisenberg, 1997). Low agreeableness (which is synonymous with disagreeableness) is characterized by an inability to get along with others. Disagreeable youth are not known to be aggressive or violent, but they are disputatious, self-centered, manipulative, and stubborn; some are prone to outbursts of negative emotionality (Asendorpf & Wilpers, 1998). Common sense suggests that it is an interpersonal liability to be disagreeable because it interferes with the rewarding exchanges necessary to establish and maintain friendships and gain acceptance by the group. This is particularly true for young adolescents, whose social world is increasingly dominated by voluntary affiliations with peers. Consistent with this notion, adolescent agreeableness is negatively correlated with peer rejection and positively correlated with peer acceptance, friendship participation, and the overall quality of close peer relationships (Jensen-Campbell et al., 2002; Scholte et al., 1997; Shiner, 2000). Like other markers of poor peer relations, low agreeableness anticipates maladjustment: Disagreeable youth are at risk for future school and work difficulties, criminality, and psychopathology (Shiner & Caspi, 2003).

Correlations between adjustment outcomes and agreeableness are similar to those between adjustment outcomes and aggression, victimization, and withdrawal, raising the prospect of overlap among markers of peer troubles. Some studies suggest ties between agreeableness and aggression, victimization, and withdrawal (Finch & Graziano, 2001; Gleason, Jensen-Campbell, & Richardson, 2004; Laursen, Pulkkinen, & Adams, 2002), but factor analyses indicate that these are independent constructs (Scholte et al., 1997). Although suggestive, these strength-of-relations findings are somewhat tangential to our interests because they do not speak to the issue of whether the low agreeable represent a separate category of troubled youth. Linear associations between variables often mask heterogeneity in the salience of particular characteristics for specific individuals (Magnusson, 2003). As a consequence, variable-centered analyses cannot tell us whether disagreeable youth are distinct from aggressive youth, victimized youth, and withdrawn youth.

Taxometrics is the process of empirically identifying and classifying individuals into typologies that specify discrete groups, each with a unique profile of defining features. Two taxometric studies have identified groups of adolescents on the basis of peer nominations (Luthar & McMahon, 1996; Rodkin, Farmer, Pearl, & Van Acker, 2000). Each identified a well-liked prosocial group, as well as groups of popular aggressive youth and unpopular isolated youth. Peer reports of victimization were not included in either investigation, but other taxometric studies reveal two additional groups of youth with peer difficulties (Schwartz, 2000): aggressive victims and passive or withdrawn victims. Taken together, these findings suggest that aggressive youth are divided into those with positive attributes and few peer problems and those with negative attributes and many peer problems. In contrast, poor peer relations were expected to typify all victimized youth and withdrawn youth, regardless of their accompanying attributes.

Three goals guided the study. The first goal was to determine whether disagreeable youth are distinct from aggressive youth, victimized youth, and withdrawn youth. Aggression, victimization, and withdrawal are the most salient markers of youth with peer problems, but previous studies have not considered these peer reputation variables in conjunction with personality variables, so the final configuration of clusters could not be anticipated. The second goal was to determine whether disagreeable youth have peer difficulties that resemble those of aggressive youth, victimized youth, or withdrawn youth. Disagreeable youth were expected to fare poorly on most concurrent measures of peer relations, particularly on indices of friendship, which are presumably more sensitive to negative emotionality and interpersonal insensitivity than measures of standing in the group. The third goal was to determine how the adjustment problems of disagreeable youth compare with those of aggressive youth, victimized youth, and withdrawn youth. In terms of concurrent and prospective externalizing problems, disagreeable youth were expected to resemble aggressive youth because both appear to have impulse control and affective regulation deficits. In terms of concurrent and prospective self-esteem and internalizing problems, disagreeable youth were expected to resemble withdrawn and victimized youth because both appear anxious and sensitive to rejection.

Method

Participants

Participants included 224 eighth-grade adolescents (120 girls and 104 boys), who ranged in age from 12 to 15 years old (M = 13.59, SD = 0.58) at the outset. Of this total, 60% were European Americans (n = 135), 15% were Asian Americans (n = 34), 9% were African Americans (n = 20), 8% were Hispanic Americans (n = 18), and the remainder identified mixed and other ethnic backgrounds.

Mothers ranged in age from 33 to 59 years old (M = 44.4, SD = 4.57) at the beginning of the study. Socioeconomic status (SES) data based on parent reports of maternal and paternal education and occupation (Hollingshead, 1975) were available for 175 households. Of a potential range of 8–66, SES scores for participants ranged from 13 to 66 (M = 54.48, SD = 9.75) during the first wave of data collection.

Participants were drawn from an ongoing study of youth attending public middle schools (containing grades 6–8) in an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse community in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area. The schools ranged in size from 726 to 988 students (M = 867.75, SD = 131.99), and the number of eighth graders in each school ranged from 248 to 335 (M = 301.57, SD = 37.00). Multiple classes within the same grade met concurrently in each school. Students attended different classes with different classmates during a school day.

A total of 1,081 eighth-grade students attending public middle schools were invited to complete peer nomination surveys; written parental consent was obtained from 74.7% (N = 807) of those invited. A staggered cohort longitudinal design was employed that included eighth-grade students from three schools in 2002 (n = 167 boys and 199 girls), from two schools in 2003 (n = 128 boys and 121 girls), from one school in 2004 (n = 31 boys and 68 girls), and from two schools in 2007 (n = 39 boys and 54 girls).

The mothers of children with consent for the peer nomination study were later contacted about participation in a longitudinal project. A total of 258 mothers agreed to their own participation in the longitudinal study and to that of their children (32.0% of the peer nomination sample). This participation rate is on the low end of rates reported in similar longitudinal studies (e.g., Hafen & Laursen, 2009; Silk, Steinberg, & Morris, 2003), partly because school time was not made available for this portion of the study. Approximately 2 months after peer nomination measures were administered in school, mothers and children in the longitudinal study separately completed questionnaires at home and returned them by mail. Approximately 1 year later, 224 mothers and ninth-grade children (86.8% of the initial sample) separately returned another set questionnaires.

Differences between those who participated in eighth-and ninth-grade longitudinal components of the study and those who participated in the peer nominations only did not arise at levels greater than chance on peer nomination and demographic variables. Also, there were no differences on any variables between those who participated in the eighth grade but not the ninth grade. A final set of contrasts failed to reveal any cohort or school differences on any variable.

Instruments and Procedure

Eighth-grade students in the peer nomination portion of the study completed the Extended Class Play (Wojslawowicz, Rubin, Burgess, Booth-LaForce, & Rose-Krasnor, 2006), a modified version of the Revised Class Play (Masten, Morison, & Pellegrini, 1985). Research assistants administered surveys to the entire class, reading instructions aloud and answering questions. Participants were instructed to pretend that as the director of an imaginary play, they were to select students who best fit 35 roles. Only students in the peer nomination portion of the study were eligible for nomination. Students in different classrooms were eligible for consideration, but nominations were limited to same-grade students attending the same school. For each role, three boys and three girls were listed in rank order. The same students could be nominated for more than one role, and self-nominations were possible. Details on the psychometric properties and factor scales are provided elsewhere (Rubin, Wojslawowicz, Rose-Krasnor, Booth-LaForce, & Burgess, 2006). Three scales were included in the present inquiry. Aggression consists of seven items (e.g., “Someone who hits others”). Shyness/withdrawal consists of four items (e.g., “A person who doesn’t talk much or who talks quietly”). Victimization consists of eight items (e.g., “Someone who gets picked on by other kids”). Nominations were summed and standardized by sex within school. Internal reliability was high (α = .88–.92).

Eighth-grade students in the peer nomination portion of the study also completed the Friendship Nominations Inventory (Bukowski, Hoza, & Boivin, 1994). The inventory was not administered to the 2004 cohort, so the data on 23 participants from the longitudinal sample were missing on this variable. Adolescents were instructed to list two same-sex best friends and three additional good friends. Nominations were limited to same-grade students attending the same school. Peer Acceptance represents the sum of all nominations an individual received, standardized by sex within school. Participants with and without peer acceptance data did not differ on any variables at any time point.

Participants in the longitudinal portion of the study completed the Big Five Inventory (John & Srivastava, 1999) in the eighth grade. Items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Agreeableness, the focus of the present inquiry, includes eight items that describe cooperative and good-natured behavior (i.e., helpful and unselfish with others; tends to find fault with others; starts quarrels with others; has a forgiving nature; is generally trusting; is cold and distant; is considerate and kind to almost everyone; is sometimes rude to others; likes to cooperate with others). Internal reliability was adequate (α = .76).

Participants in the longitudinal portion of the study also completed a revised version of the Friendship Quality Questionnaire (Parker & Asher, 1993; Rubin et al., 2006) in the eighth grade. Items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (really true). Friendship quality includes 33 items that encompass constructive features of the relationship (e.g., “When I’m mad about something that happened to me, I can always talk to ____ about it”). Friendship conflict includes seven items that encompass destructive features of the relationship (e.g., “____ and I get mad at each other a lot”). Internal reliability was adequate (α = .79–.83).

Participants in the longitudinal portion of the study completed the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (Harter, 1988) in the eighth and ninth grades. The inventory was not administered in the ninth grade to the 2002 and 2003 cohorts, so 152 participants were missing ninth-grade data on this variable. Three subscales with five items each were included in the present inquiry. Items were rated on a 4-point structured alternative format scale. Behavioral conduct provides an assessment of comportment (e.g., “Some teenagers often do not like the way they behave but other teenagers usually like the way they behave”). Global self-worth provides an assessment of overall self-esteem (e.g., “Some teenagers are disappointed with themselves but other teenagers are pretty pleased with themselves”). Social acceptance provides an assessment of competence in the peer group (e.g., “Some teenagers find it hard to make friends but for other teenagers it is pretty easy”). Across grades, internal reliability was adequate (α = .78–.85, M = .82).

During the eighth and ninth grades, mothers completed the Child Behavior Checklist, and children completed the Youth Self Report (Achenbach, 1991). Both describe the child’s adjustment on eight narrowband indices. Five subscales load on two broadband indices of adjustment. Externalizing problems (e.g., “gets in many fights”) includes two narrowband subscales (aggression and delinquency). Internalizing problems (e.g., “unhappy, sad, or depressed”) includes three narrowband subscales (withdrawal, somatic complaints, and anxious/depressed). Three additional subscales load on separate factors. Of these, the present study includes social problems (e.g. “My child does not get along well with others”). All items were rated on a scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true). Across grades, internal reliability was adequate for maternal reports (α = .73–.83, M = .77) and self-reports (α = .72–.86, M = .81). Average item scores are presented in tables; raw scores were used in analyses.

Plan of Analysis

Hierarchical cluster analyses (with Ward’s solution) were conducted with eighth-grade peer-nominated aggression, victimization, and shyness/withdrawal, and eighth-grade self-reported agreeableness. Ward’s procedure is designed to maximize the homogeneity within each cluster by minimizing their error sum of squares (ESS), which is the sum of the squared distance of each individual’s score from the mean of his or her cluster. The quality of the cluster solution was evaluated in terms of the overall explained ESS and each cluster’s homogeneity. The optimal solution explains the greatest amount of ESS (up to 100%), with the least amount of heterogeneity (homogeneity coefficients greater than .70 but not more than 1.00). Additional cluster analytic procedures validated the results (Blashfield & Aldenderfer, 1988). First, the sample was split in half, and a confirmatory k-means cluster analysis was performed on both halves of the sample. A similar pattern of results emerged. Second, a leave-one-out procedure replicated the cluster solution by omitting the members of one group and replicating the existence of the remaining groups. Finally, separate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) contrasted the cluster groups on clustering variables to identify the distinguishing feature of each group.

To determine whether disagreeable youth are characterized by a distinct set of social difficulties, the groups that emerged from the cluster analysis were contrasted in terms of concurrent peer relations. Separate ANOVAs were conducted with sex and cluster groups as independent variables. Eighth-grade friendship conflict, friendship quality, peer acceptance, and social problems were the dependent variables.

To determine whether disagreeable youth are characterized by a distinct set of adjustment difficulties, the groups that emerged from the cluster analysis were contrasted in terms of well-being over time. Separate repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted with sex and eighth-grade cluster groups as independent variables. Externalizing problems, internalizing problems and self-worth were dependent variables. Time (eighth grade and ninth grade) was the repeated measure.

Results

Intercorrelations

Correlations examined associations between eighth-grade clustering variables (p < .05). Victimization and aggression were correlated (r = .14), and shyness/withdrawal was linked to both victimization (r = .37) and aggression (r = −.16). There were no statistically significant associations between agreeableness and any of the peer nomination variables.

Table 1 includes correlations between the eighth-grade clustering variables and the eighth-grade peer relations variables. Agreeableness correlated with all peer relations variables except peer reports of acceptance. Aggression was associated only with friendship quality. Shyness/withdrawal was correlated with peer and self-reports of acceptance, friendship quality, and maternal reports of social problems. Victimization was associated with self-reports of acceptance, and maternal and self-reports of social problems.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations between Eighth-Grade Clustering Variables and Eighth-Grade Peer Relations Variables

| Clustering Variable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Relations Variable | Agreeableness | Aggression | Shyness/Withdrawal | Victimization | M (SD) |

| Acceptance | |||||

| Peer reports | .10 | −.02 | −.29** | −.12 | 0.05 (0.86) |

| Self-reports | .29** | .12 | −.33** | −.42** | 3.31 (0.62) |

| Friendship | |||||

| Conflict | −.19** | .09 | −.05 | .03 | 1.71 (0.56) |

| Quality | .41** | .19** | −.26** | −.09 | 4.03 (0.52) |

| Social problems | |||||

| Maternal reports | −.29** | −.08 | .27** | .34** | 0.12 (0.17) |

| Self-reports | −.26** | .04 | .11 | .30** | 0.24 (0.22) |

| M (SD) | 3.95 (0.69) | 0.06 (0.84) | 0.02 (0.87) | 0.04 (0.82) | |

Notes.

p < .05

p < .01.

N = 201 for peer reported acceptance. N = 224 for all other variables. Social problems ranged from 0 to 2. Self-reported acceptance ranged from 1 to 4. Friendship conflict and quality ranged from 1 to 5.

Table 2 includes correlations between the eighth-grade clustering variables and the eighth-and ninth-grade adjustment variables. Agreeableness correlated with all adjustment variables except ninth-grade global self-worth. Aggression was associated with eighth-and ninth-grade self-reports of externalizing problems and with eighth-grade self-reports of behavioral conduct self-worth and global self-worth. Shyness/withdrawal was correlated with eighth-and ninth-grade global self-worth. Victimization was correlated with all adjustment variables except eighth-and ninth-grade behavioral conduct self-worth and ninth-grade self-reported internalizing problems.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations between Eighth-Grade Clustering Variables and Eighth- and Ninth-Grade Adjustment Variables

| Adjustment Variable | Clustering Variable | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreeableness | Aggression | Shyness/Withdrawal | Victimization | M (SD) | ||||||

| 8th | 9th | 8th | 9th | 8th | 9th | 8th | 9th | 8th | 9th | |

| Externalizing problems | ||||||||||

| Maternal reports | −.32** | −.28** | .11 | .13 | −.10 | −.12 | .26** | .24** | 0.13 (0.16) | 0.12 (0.15) |

| Self-reports | −.37** | −.31** | .24** | .29** | −.09 | −.07 | .23** | .19** | 0.30 (0.26) | 0.28 (0.22) |

| Internalizing problems | ||||||||||

| Maternal reports | −.29** | −.21** | −.03 | .02 | .13 | .09 | .16** | .17** | 0.21 (0.19) | 0.25 (0.23) |

| Self-reports | −.26** | −.17** | .07 | .03 | .06 | .10 | .18** | .13 | 0.29 (0.25) | 0.31 (0.29) |

| Self-worth | ||||||||||

| Behavioral conduct | .41** | .31** | −.21** | −.15 | −.13 | −.05 | −.10 | −.06 | 3.09 (0.65) | 3.11 (0.68) |

| Global | .29** | .11 | −.15* | −.11 | −.29** | −.22* | −.31** | −.28** | 3.27 (0.58) | 3.33 (0.62) |

Notes.

p < .05

p < .01.

N = 201 for peer reported acceptance. N = 224 for all other variables. Externalizing problems and internalizing problems ranged from 0 to 2. Self-worth ranged from 1 to 4.

Cluster Analyses

Cluster analyses were conducted to determine whether disagreeable youth are distinct from aggressive youth, victimized youth, and withdrawn youth. Preliminary analyses failed to identify outliers with unique profiles, so all participants were included in the analyses. A six-cluster solution emerged that explained 77.3% of the total ESS, with cluster homogeneity coefficients that ranged from 0.71 to 0.88 (M = 0.79). This six-cluster solution compared favorably to a five-cluster solution that explained less error (ESS = 73.1%) and to a seven-cluster solution with unacceptably high homogeneity coefficients (M = 0.84, range 0.70–1.14). The five-, six-, and seven-cluster solutions each contained the same distinct cluster of low agreeable youth.

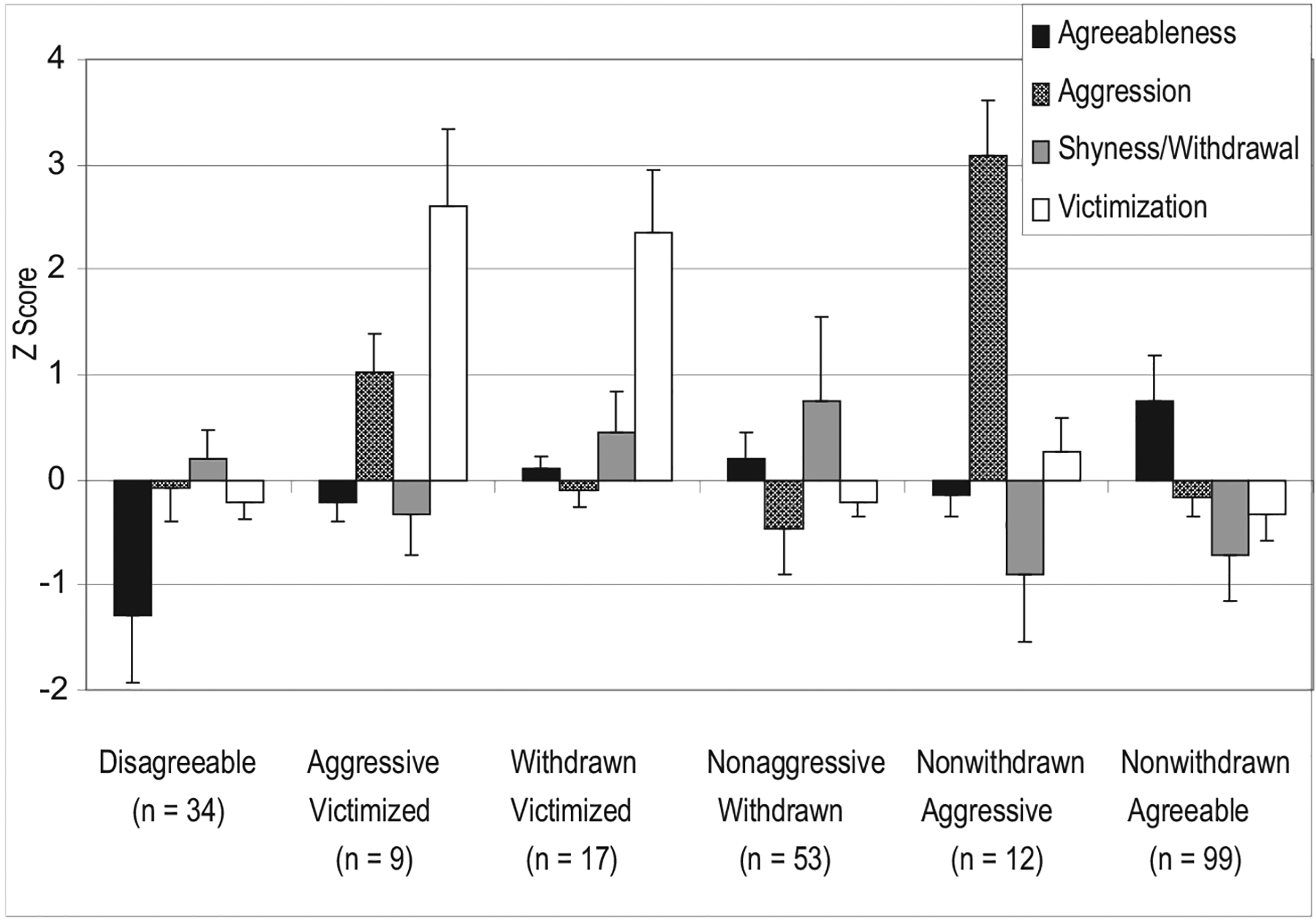

The six-cluster solution is depicted in Figure 1. One-way ANOVAs identified the salient features of each cluster. Statistically significant differences emerged for agreeableness, F(5, 218) = 59.23, p < .001; aggression, F(5, 218) = 122.17, p < .001; shyness/withdrawal F(5, 218) = 46.11, p < .001; and victimization, F(5, 218) = 132.64, p < .001. Cluster labels describe statistically significant (p < .01) group differences in follow-up LSD (least significant difference) tests. Nonwithdrawn agreeable youth (d = 0.62–1.92) were more agreeable than other groups of youth (except nonaggressive withdrawn youth, d = 0.34); disagreeable youth (d = 0.87–1.92) were less agreeable than other groups of youth. Aggressive victimized youth (d = 1.06–1.76) and nonwithdrawn aggressive youth (d = 2.03–3.57) were more aggressive than other groups of youth; nonaggressive withdrawn youth (d = 0.48–3.21) were less aggressive than other groups of youth (except nonwithdrawn agreeable youth, d = 0.21). Nonaggressive withdrawn youth (d = 0.63–2.13) and withdrawn victimized youth (d = 0.88–1.71) were more shy/withdrawn than other groups of youth (except disagreeable youth, d = 0.38 and 0.17, respectively); nonwithdrawn aggressive youth (d = 0.64–2.13) and nonwithdrawn agreeable youth (d = 0.53–1.75) were less shy/withdrawn than other groups of youth. Aggressive victimized youth (d = 1.88–2.34) and withdrawn victimized youth (d = 2.76–3.22) were more victimized than other groups of youth. Clusters did not differ as a function of age, ethnicity, sex, or SES.

Figure 1.

Six Cluster Solution for Agreeableness, Aggression, Shyness/Withdrawal, and Victimization

Some of these labels were simplified in the text that follows (but retained in full in the tables). We refer to nonwithdrawn agreeable youth as agreeable youth, nonaggressive withdrawn youth as withdrawn youth, and nonwithdrawn aggressive youth as aggressive youth.

Group Differences in Concurrent Peer Relations

ANOVAs were conducted to determine whether disagreeable youth have concurrent peer difficulties that resemble those of aggressive youth, victimized youth, or withdrawn youth. Table 3 contains results contrasting groups on eighth-grade peer relations. Unless otherwise indicated, there were no main effects or interactions involving sex.

Table 3.

Group Differences in Concurrent Peer Relations

| Dependent Variable | Aggressive Victimized | Withdrawn Victimized | Disagreeable | Nonaggressive Withdrawn | Nonwithdrawn Aggressive | Nonwithdrawn Agreeable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | |

| Acceptance | ||||||||||||

| Self-reports | 2.67c | (0.59) | 2.51c | (0.64) | 3.14b | (0.53) | 3.11b | (0.56) | 3.41a | (0.44) | 3.56a | (0.49) |

| Peer reports | −0.29b | (0.84) | −0.16b | (0.76) | −0.04b | (0.79) | −0.17b | (0.81) | −0.25b | (0.56) | 0.34a | (0.98) |

| Friendship | ||||||||||||

| Conflict | 1.87ab | (0.55) | 1.54c | (0.46) | 1.91a | (0.57) | 1.71bc | (0.52) | 1.74 | (0.74) | 1.64bc | (0.58) |

| Quality | 4.08b | (0.61) | 3.91b | (0.54) | 3.59c | (0.67) | 3.93b | (0.59) | 4.33a | (0.26) | 4.17ab | (0.48) |

| Social problems | ||||||||||||

| Maternal reports | 0.26a | (0.23) | 0.27a | (0.22) | 0.20ab | (0.28) | 0.18ab | (0.22) | 0.12bc | (0.14) | 0.07c | (0.10) |

| Self-reports | 0.39a | (0.31) | 0.43a | (0.26) | 0.39a | (0.35) | 0.31 | (0.23) | 0.25b | (0.18) | 0.19b | (0.18) |

Note. N = 201 for friendship nominations. N = 224 for all other variables. Across rows, numbers with different subscripts differ significantly (p < .05) in LSD contrasts.

Acceptance.

A main effect for clusters emerged for self-reports of social acceptance, F(5, 212) = 14.12, p < .001, and peer reports of acceptance, F(5, 212) = 12.23, p < .001. In terms of self-reports, disagreeable youth and withdrawn youth scored higher than aggressive victimized youth and withdrawn victimized youth on concurrent perceived acceptance (d = 0.77–1.08), but lower than aggressive youth and agreeable youth (d = 0.56–0.86). In terms of peer reports, agreeable youth had higher levels of concurrent acceptance than did disagreeable youth (d = 0.43) and youth in all other groups (d = 0.57–0.77).

Friendship.

A main effect for clusters emerged for friendship conflict, F(5, 193) = 7.03, p < .001, and friendship quality, F(5, 193) = 9.82, p < .001. Disagreeable youth reported more concurrent conflict with best friends than did withdrawn victimized youth, withdrawn youth, and agreeable youth (d = 0.37–0.72). In addition, aggressive victimized youth reported more conflict with best friends than did withdrawn victimized youth (d = 0.65). Disagreeable youth reported lower concurrent friendship quality than youth in all other groups (d = 0.53–1.59). In addition, aggressive youth reported higher friendship quality than aggressive victimized youth, withdrawn victimized youth, and withdrawn youth (d = 0.57–1.05).

Social problems.

Main effects for clusters emerged for maternal reports of social problems, F(5, 212) = 7.23, p < .001, and self-reports of social problems, F(5, 212) = 8.61, p < .001. In terms of maternal reports, disagreeable youth, aggressive victimized youth, withdrawn victimized youth, and withdrawn youth had more concurrent social problems than did agreeable youth (d = 0.68–1.25). In addition, aggressive victimized youth and withdrawn victimized youth had more mother-reported social problems than did aggressive youth (d = 0.76–0.83). In terms of self-reports, disagreeable youth, aggressive victimized youth, and withdrawn victimized youth had more concurrent social problems than did aggressive youth and agreeable youth (d = 0.57–1.55).

In sum, the findings were consistent with our predictions: Disagreeable youth had the most friendship conflict and the lowest friendship quality. The social problems of disagreeable youth rivaled those of victimized youth and withdrawn youth. Disagreeable youth fared somewhat better on self-reported acceptance, scoring higher than both groups of victimized youth and about the same as withdrawn youth.

Group Differences in Concurrent and Prospective Adjustment Problems and Self-worth

ANOVAs were conducted to determine how the prospective adjustment problems of disagreeable youth compare with those of aggressive youth, victimized youth, and withdrawn youth. Table 4 summarizes results contrasting groups in terms of eighth-and ninth-grade adjustment outcomes. Unless otherwise indicated, there were no main effects or interactions involving sex. There were no main effects or interactions involving time, so follow-up contrasts were conducted on the average of eighth-and ninth-grade scores. For those participants with only a single wave of data on a variable, the mean score represented reports from that grade only. To address concerns about overlap between the aggression clustering variables and the externalizing outcome variables, separate supplemental analyses were conducted on the delinquency and aggression narrowband scales. The same pattern of results emerged, so findings for the broadband construct of externalizing problems are presented.

Table 4.

Group Differences in Prospective Adjustment

| Dependent Variable | Aggressive Victimized | Withdrawn Victimized | Disagreeable | Nonaggressive Withdrawn | Nonwithdrawn Aggressive | Nonwithdrawn Agreeable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | |

| Externalizing Problems | ||||||||||||

| Maternal reports | 0.28a | (0.16) | 0.12c | (0.16) | 0.23ab | (0.17) | 0.10c | (0.15) | 0.19b | (0.16) | 0.09c | (0.11) |

| Self-reports | 0.41a | (0.28) | 0.25b | (0.26) | 0.52a | (0.32) | 0.24b | (0.19) | 0.45a | (0.25) | 0.25b | (0.19) |

| Internalizing problems | ||||||||||||

| Maternal reports | 0.20bc | (0.14) | 0.39a | (0.19) | 0.28b | (0.22) | 0.29b | (0.25) | 0.18c | (0.17) | 0.14c | (0.14) |

| Self-reports | 0.32 | (0.23) | 0.41a | (0.25) | 0.38a | (0.32) | 0.34 | (0.23) | 0.32 | (0.21) | 0.25b | (0.22) |

| Self-worth | ||||||||||||

| Behavioral conduct | 2.77b | (0.49) | 3.09a | (0.57) | 2.77b | (0.62) | 3.18a | (0.50) | 2.74b | (0.66) | 3.23a | (0.54) |

| Global | 2.86cd | (0.61) | 2.74d | (0.54) | 3.10bc | (0.59) | 3.21b | (0.61) | 2.88cd | (0.70) | 3.46a | (0.57) |

Note. N = 224. Numbers with different subscripts differ significantly (p < .05) in LSD contrasts. Repeated measures ANOVAs revealed no time by cluster group interactions, so scores represent the average of eighth- and ninth-grade reports.

Externalizing problems.

Main effects for clusters emerged for maternal reports of externalizing problems, F(5, 212) = 7.34, p < .001, and self-reports of externalizing problems, F(5, 212) = 18.63, p < .001. In terms of maternal reports, disagreeable youth and aggressive victimized youth had more concurrent and prospective externalizing problems than did withdrawn victimized youth, withdrawn youth, and agreeable youth (d = 0.67–1.41). In addition, aggressive victimized youth had more mother-reported externalizing problems than did aggressive youth (d = 0.56). In terms of self-reports, disagreeable youth, aggressive victimized youth, and aggressive youth had more concurrent and prospective externalizing problems than did withdrawn victimized youth, withdrawn youth, and agreeable youth (d = 0.68–1.10).

Internalizing problems.

Main effects for clusters emerged for maternal reports of internalizing problems, F(5, 212) = 8.99, p < .001, and self-reports of internalizing problems, F(5, 212) = 7.87, p < .001. There was also a main effect for sex on self-reports of internalizing problems F(1, 212) = 7.41, p < .001. Girls (M = 0.37, SD = 0.23) reported more internalizing problems than boys (M = 0.27, SD = 0.22). In terms of maternal reports, disagreeable youth and withdrawn youth had more concurrent and prospective internalizing problems than aggressive youth and agreeable youth (d = 0.52–0.78) but less than withdrawn victimized youth (d = 0.45–0.54). In addition, withdrawn victimized youth had more internalizing problems than did aggressive victimized youth (d = 1.15). In terms of self-reports, disagreeable youth and withdrawn victimized youth reported more internalizing problems than did agreeable youth (d = 0.48–0.68).

Self-worth.

Main effects for clusters emerged for behavioral conduct self-worth, F(5, 60) = 8.19, p < .001, and global self-worth, F(5, 60) = 6.20, p < .001. In terms of behavioral conduct, disagreeable youth, aggressive victimized youth, and aggressive youth reported lower concurrent and prospective self-worth than did withdrawn victimized youth, withdrawn youth, and agreeable youth (d = 0.47–0.93). In terms of global self worth, disagreeable youth and withdrawn youth reported lower concurrent and prospective self-worth than agreeable youth (d = 0.42–0.62), but higher self-worth than withdrawn victimized youth (d = 0.64–0.82). In addition, withdrawn youth and agreeable youth reported higher self-worth than did aggressive victimized youth and aggressive youth (d = 0.50–1.02).

In sum, we predicted that disagreeable youth would present externalizing problems at levels comparable to those of aggressive youth, and, indeed, groups with these attributes had the most behavior problems. We also predicted that disagreeable youth would resemble withdrawn youth and victimized youth in terms of internalizing problems. Consistent with this prediction, disagreeable youth and withdrawn victimized youth had the highest self-reported internalizing problems, and disagreeable youth and withdrawn youth were second only to withdrawn victimized youth on mother-reported internalizing problems. We predicted that disagreeable youth would have low self-worth and they did, but they tended to resemble aggressive youth and not (as we had predicted) withdrawn youth.

Discussion

Cluster analyses indicated that disagreeable youth represent a separate category of troubled youth whose members are not aggressive, victimized, or withdrawn. Disagreeable youth fared poorly on most measures of interpersonal and behavioral adjustment. Victimized youth had the highest scores on most concurrent measures of social difficulties, but disagreeable youth matched them on some dimensions and trailed just behind them on the others. Disagreeable youth had some of the highest levels of concurrent and prospective adjustment problems, with rates of self-and maternal-reported internalizing problems that rivaled those of withdrawn victimized youth and withdrawn youth, and rates of self-and mother-reported externalizing problems that rivaled those of aggressive victimized youth and aggressive youth.

This investigation is unique in many respects. It is the first to indicate that low agreeable individuals comprise a discrete subset of youth with social difficulties. Disagreeable adolescents did not have favorable scores on any measure of social functioning; they were particularly noteworthy for their troubled friendships. Arguably, disagreeable youth have more problems in more domains than any of their peers. As might be expected, the social problems of disagreeable youth were most evident at the level of the dyad; the rude and the obnoxious make poor friends. Unlike other groups of youth with peer troubles who tended to suffer from adjustment difficulties in a single domain, disagreeable youth had elevated levels of both internalizing problems and externalizing problems. Few would argue with the claim that low agreeableness is a liability. Variable-centered analyses have documented negative correlations between agreeableness and conduct problems (Shiner, 2000), and the apparent contribution of agreeableness to poor peer relations and depression (Finch & Graziano, 2001; Jensen-Campbell et al., 2002). What sets our findings apart is the designation of low agreeableness as a marker of a special class of troubled youth, separate from those who are victimized, those who are aggressive, and those who are shy and withdrawn.

Low agreeableness is an underappreciated developmental phenomenon. Approximately 15% of our sample was disagreeable, a figure equivalent to the aggressive victimized, withdrawn victimized, and aggressive groups combined. Even if the latter groups are somewhat lower than might be expected, the findings suggest that a sizeable proportion of youth with interpersonal troubles have been overlooked in conventional research on peer relationships. Contrary to popular opinion, low agreeableness is not a developmental phase that characterizes adolescence. Consistent and reliable markers of low agreeableness are evident by age 3. Disagreeableness appears to have origins in early childhood irritability coupled with a lack of inhibition and emotional regulation (Caspi et al., 2003). Meta-analyses suggest that agreeableness is one of the most enduring personality dimensions, with stability coefficients well above .50 (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000). Trait consistency appears to be especially pronounced for those with very low levels of agreeableness. A 25-year longitudinal study indicated that most children described by their teachers as noncompliant and lacking self-control during the early grade-school years grew up to be impulsive and disagreeable adults (Laursen et al., 2002). The consequences of being disagreeable are profound: These same middle-aged adults presented elevated levels of alcoholism, criminality, depression, and career instability relative to the high agreeable members of their cohort. We found that the interpersonal and adjustment problems of low agreeable eighth graders continued during the ninth grade, a trend that is likely to persist given the stability of this trait and the potential for problems that accompany it to snowball over time, interfering with the formation of friendships that may protect against cascading difficulties (Bukowski, Laursen, & Hoza, in press; Laursen, Bukowski, Aunola, & Nurmi, 2007).

The troubles of the victimized are well documented. Consistent with previous studies (Hanish & Guerra, 2002), we found that victimized youth had social difficulties and poor adjustment. Although the number of youth in each group was small, the findings were consistent with a previous cluster analytic study of young children that distinguished aggressive victims from passive victims (Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2003). Little is known about the attributes that set victimized youth apart from their peers, aside from the fact that they have few friends, have low self-worth, and are physically weak (Hodges, Malone, & Perry, 1997). We found that neither victimized group stood out in terms of agreeableness, which leads us to conclude that most of the adolescents who experienced persistent victimization were not victimized because they were disagreeable.

Withdrawn youth resemble overcontrolled youth. Both are poorly accepted by peers and score somewhat higher than agemates on maternal reports of social problems and internalizing problems (for review, see Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005). We can only speculate about the degree to which membership in these groups overlaps. A higher proportion of the sample was classified as withdrawn in the present study than has been classified as overcontrolled in other studies (e.g., Robins, John, Caspi, Moffitt, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1996). We suspect that overcontrolled youth tended to be classified as withdrawn, but because neuroticism was not a clustering variable in our study, the withdrawn group also included those who were not particularly neurotic, lowering the group’s internalizing scores and raising their self-esteem scores.

This is not the first study to identify a group of youth who are aggressive and socially skilled, high on self-perceptions of popularity but low on social acceptance. The aggressive youth in our study resemble aggressive-popular adolescents (Luthar & McMahon, 1996) and tough adolescents (Farmer, Estell, Bishop, O’Neal, & Cairns, 2003; Rodkin et al., 2000) from previous studies, who were noteworthy for disruptive, antisocial behavior and a relative absence of internalizing problems. New to the present study was the finding of low self-esteem among these aggressive youth. These results shed new light on this controversial group, suggesting that an insecure interior may be hiding beneath a brazen exterior.

No study is without limitations. In our case, the size of the sample restricted the number of clustering variables and may have limited the number of clusters. Additional clustering variables would be expected to alter the resulting taxonomy only insofar as they represent characteristics that help to define unique groups. Some might argue that different results would emerge if other variables linked to interpersonal functioning were included (e.g., conscientiousness; Jensen-Campbell & Malcolm, 2007), but this is unlikely to alter the main findings concerning distinctions between disagreeable youth and aggressive youth, withdrawn youth, and victimized youth. With a larger sample, more groups may be identified as clusters subdivide into smaller, more homogeneous components. Subtypes of disagreeable youth might emerge, along with a maladjusted group whose sole salient characteristic was elevated aggression. Failure to find the latter, however, is not entirely anomalous; similar studies also found that clusters of aggressive youth were limited to the well adjusted and popular (Luthar & McMahan, 1996).

Other concerns should be noted. First, the more affluent were better represented in our sample than the less affluent, which may have limited the variance in behavior problem scores but probably had little impact on scores for personality traits and peer difficulties. Second, the concurrent nature of the data on social difficulties precludes causal interpretations about the origins and consequences of group membership. The organization of the analyses implies that peer problems follow from individual characteristics. We make no claim to this effect, but others have found that personality variables drive changes in relationships and not the reverse (Asendorpf & Wilpers, 1998). Third, some may question the need for person-centered research in light of variable-centered studies indicating that victimization, shyness/withdrawal, and agreeableness have linear associations with individual adjustment. The techniques often yield complimentary results (Laursen & Hoff, 2006). A comparison of results from correlations (Table 1) and clustering techniques (Tables 2 and 3) illustrates the novel contribution of our approach. Aggression, shyness/withdrawal, and victimization had patterns of correlations that obscured important differences between individuals who were high or low on two of these attributes. Agreeableness and shyness/withdrawal combined to form groups with outcomes that differed from what might be expected from the correlates of each. In most cases, the difference between the well-functioning and the poorly functioning groups identified through clustering procedures is considerably greater in magnitude than that suggested by linear associations between variables. Fourth, agreeableness was assessed in a manner that differed from the other grouping variables. Replication of the cluster analytic results with peer nominations of disagreeable youth is essential. Fifth, we know that associations between agreeableness and maladjustment differ for boys and girls (Pursell, Laursen, Rubin, Booth-LaForce, & Rose-Krasnor, 2008). Small sample sizes limited our power to fully explore sex differences in cluster membership and cluster correlates. Finally, the absence of longitudinal data on the composition of the clusters and the relatively low rates of participation raise legitimate questions about the generalizability of the results. There is plenty of anecdotal evidence to support our claims about the chronically unpleasant, but this is no substitute for additional empirical study.

This multiple-method, multiple-reporter study represents one of the first attempts to determine whether the low agreeable are a distinct group of youth with social troubles. Being disagreeable does not go hand in hand with being aggressive; hostile adolescents are not alone in their inability to get along with others. Disagreeable youth are not shy; low agreeableness ought not be confused with reticence. Disagreeable youth are not routinely victimized because of their demeanor. Instead, disagreeable youth have attributes and problems that, when taken together, set them apart from the aggressive, the shy, and the victimized. In many respects, our findings bolster claims that William Hazlitt made in his (then) widely read essay “On Disagreeable People” (1827/1903): “If we look about us, and ask who are the agreeable and disagreeable people in the world, we shall see that it does not so much depend on their virtues or vices—their understanding or stupidity—as on the degree of pleasure or pain they seem to feel in ordinary social intercourse.”

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by a grant from the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (MH58116) to K.H.R and by a grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation (0923745) to B.L. Special thanks to Bill Bukowski, Wyndol Furman, and Bill Hartup for comments on a previous draft.

Contributor Information

Brett Laursen, Florida Atlantic University.

Christopher A. Hafen, Florida Atlantic University

Kenneth H. Rubin, University of Maryland

Cathryn Booth-LaForce, University of Washington.

Linda Rose-Krasnor, Brock University.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4–18, YSR, & TRF profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf JB, & Wilpers S (1998). Personality effects on social relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1531–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Blashfield RK, & Aldenderfer MS (1988). The methods and problems of cluster analysis. In Nesselroade JR & Cattell RB (Eds.), Handbook of multivariate experimental psychology (2nd ed., pp. 447–473). New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Turgeon L, & Poulin F (2002). Assessing aggressive and depressed children’s social relations with classmates and friends: A matter of perspective. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 609–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Laursen B, & Hoza B (in press). The snowball effect: Friendship moderates over-time escalations in depressed affect among avoidant and excluded children. Development and Psychopathology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Hoza B, & Boivin M (1994). Measuring friendship quality during pre-and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the Friendship Qualities Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11, 472–484. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Harrington H, Milne B, Amell JW, Theodore RF, & Moffitt TW (2003). Children’s behavioral styles at age 3 are linked to their adult personality traits at age 26. Journal of Personality, 71, 495–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Roberts BW, & Shiner RL (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 453–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer TW, Estell DB, Bishop JL, O’Neal KK, & Cairns BD (2001). Rejected bullies or popular leaders? The social relations of aggressive subtypes of rural African American early adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 39, 992–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch JF, & Graziano WG (2001). Predicting depression from temperament, personality, and patterns of social relations. Journal of Personality, 69, 27–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason KA, Jensen-Campbell LA, & Richardson DS (2004). Agreeableness as a predictor of aggression in adolescence. Aggressive Behavior, 30, 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Bellmore AD, & Mize J (2006). Peer victimization, aggression, and their co-occurrence in middle school: Pathways to adjustment problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 363–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano WG, & Eisenberg N (1997). Agreeableness: A dimension of personality. In Hogan R, Johnson J, & Briggs S (Eds.), Handbook of personality psychology (pp. 795–824). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hafen CA, & Laursen B (2009). More problems and less support: Early adolescent adjustment forecasts changes in perceived support from parents. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, & Guerra NG (2002). A longitudinal analysis of patterns of adjustment following peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 69–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S (1988). The self-perception profile for adolescents. Denver, CO: University of Denver. [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW (2009). Critical issues and theoretical viewpoints. In Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, & Laursen B (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 3–19). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hazlitt W (1903). On disagreeable people. Sketches and essays. London: Richards. (Original work published 1827) [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Malone MJ, & Perry DG (1997). Individual risk and social risk as interacting determinants of victimization in the peer group. Developmental Psychology, 33, 1032–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB (1975). Four Factor Index of Social Status. Unpublished manuscript, Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Campbell LA, Adams R, Perry DG, Workman KA, Furdella JQ, & Egan SK (2002). Agreeableness, extraversion, and peer relations in early adolescence: Winning friends and deflecting aggression. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 224–251. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Campbell LA, & Malcolm KT (2007). The importance of conscientiousness in adolescent interpersonal relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 368–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, & Srivastava S (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In Pervin LA & John OP (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer-Ladd B (2003). Identification of aggressive and asocial victims and the stability of their peer victimization. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 49, 401–425. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Bukowski WM, Aunola K, & Nurmi J-E (2007). Friendship moderates prospective associations between social isolation and adjustment problems in young children. Child Development, 78, 1395–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, & Hoff E (2006). Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52, 377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Pulkkinen L, & Adams R (2002). The antecedents and correlates of agreeableness in adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 38, 591–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, & McMahon TJ (1996). Peer reputation among inner-city adolescents: Structure and correlates. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 6, 581–603. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson D (2003). The person approach: Concepts, measurement models, and research strategy. In Peck SC & Roeser RW (Eds.), New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development: Person-centered approaches to studying development in context (No. 101, pp. 3–23). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Morison P, & Pellegrini DS (1985). A Revised Class Play method of peer assessment. Child Development, 21, 523–533. [Google Scholar]

- Oh W, Rubin KH, Bowker JC, Booth-LaForce CL, Rose-Krasnor L, & Laursen B (2008). Trajectories of social withdrawal from middle childhood to early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 553–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, & Asher SR (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29, 611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Parker J, Rubin KH, Erath S, Wojslawowicz JC, & Buskirk AA (2006). Peer relationships and developmental psychopathology. In Cicchetti D & Cohen D (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation, Vol. 2 (2nd ed., pp. 419–493). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, & Cillessen A (2003). Forms and functions of adolescent peer aggression associated with high levels of peer social status. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 49, 310–342. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Rancourt D, Guerry JD, & Browne CB (2009). Peer reputations and psychological adjustment. In Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, & Laursen B (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 548–567). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pursell GR, Laursen B, Rubin KH, Booth-LaForce C, & Rose-Krasnor L (2008). Gender differences in patterns of association between prosocial behavior, personality, and externalizing problems. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 472–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, & DelVecchio WF (2000). The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, John OP, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, & Stouthamer-Loeber M (1996). Resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled boys: Three replicable personality types. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 157–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodkin PC, Farmer TW, Pearl R, & van Acker R (2000). Heterogeneity of popular boys: Antisocial and prosocial configurations. Developmental Psychology, 36, 14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Bowker JC, & Kennedy AE (2009). Avoiding and withdrawing from the peer group. In Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, & Laursen B (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 303–321). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Chen X, & Hymel S (1993). The socio-emotional characteristics of extremely aggressive and extremely withdrawn children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 39, 518–534. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Wojslawowicz JC, Rose-Krasnor L, Booth-LaForce C, & Burgess KB (2006). The best friendships of shy/withdrawn children: Prevalence, stability, and relationship quality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 139–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BH (1999). A multi-method exploration of the friendships of children considered socially withdrawn by their peers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 27, 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholte RHJ, van Aken MAG, & van Lieshout CFM (1997). Adolescent personality factors in self-ratings and peer nominations and their prediction of peer acceptance and peer rejection. Journal of Personality Assessment, 69, 534–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D (2000). Subtypes of victims and aggressors in children’s peer groups. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28, 181–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner R, & Caspi A (2003). Personality differences in childhood and adolescence: Measurement, development, and consequences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 2–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner RL (2000). Linking childhood personality with adaptation: Evidence for continuity and change across time into late adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 310–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Steinberg L, & Morris AS (2003). Adolescents’ emotion regulation in daily life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Development, 74, 1869–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt T, & Hymel S (2006). Aggression and social status: The moderating roles of sex and peer-valued characteristics. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 396–408. [Google Scholar]

- Wojslawowicz JC, Rubin KH, Burgess KB, Booth-LaForce CL, & Rose-Krasnor L (2006). Behavioral characteristics associated with stable and fluid best friendship patterns in middle childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52, 671–693. [Google Scholar]