Abstract

Biaryl scaffolds are privileged templates used in the discovery and design of therapeutics with high affinity and specificity for a broad range of protein targets. Biaryls are found in the structures of therapeutics, including antibiotics, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, neurological and antihypertensive drugs. However, existing synthetic routes to biphenyls rely on traditional coupling approaches that require both arenes to be prefunctionalized with halides or pseudohalides with the desired regiochemistry. Therefore, the coupling of drug fragments may be challenging via conventional approaches. As an attractive alternative, directed C−H activation has the potential to be a versatile tool to form para-substituted biphenyl motifs selectively. However, existing C–H arylation protocols are not suitable for drug entities as they are hindered by catalyst deactivation by polar and delicate functionalities present alongside the instability of macrocyclic intermediates required for para-C−H activation. To address this challenge, we have developed a robust catalytic system that displays unique efficacy towards para-arylation of highly functionalized substrates such as drug entities, giving access to structurally diversified biaryl scaffolds. This diversification process provides access to an expanded chemical space for further exploration in drug discovery. Further, the applicability of the transformation is realized through the synthesis of drug molecules bearing a biphenyl fragment. Computational and experimental mechanistic studies further provide insight into the catalytic cycle operative in this versatile C−H arylation protocol.

Subject terms: Homogeneous catalysis, Catalytic mechanisms

Biaryls are privileged structural motif used in the discovery and design of therapeutics with high affinity and specificity for a broad range of protein targets. Herein, the authors develop a robust strategy for para-C–H arylation of arenes with a range of (het)aryl iodides, including bioactive molecules.

Introduction

Chemistries utilizing unactivated C–H bonds as potential sites for regioselective functionalization offer an efficient strategy for the decoration and diversification of biologically active molecules1,2. Alongside the growth of new directions in C–H transformations, there have been consistent efforts to harness broad functional group compatibility to expand the scope of these transformations to include complex molecules3–5. These advances have attracted the attention of the medicinal chemistry community, where C–H functionalization methods have been harnessed to explore chemical space inaccessible to conventional synthetic processes6–8. In this regard, C−H arylation to form biphenyl motifs can be an effective method of accessing areas of chemical space important for drug discovery and development9. This is attributed to the pivotal role of aromatic components in protein-ligand recognition10 through non-covalent interactions, which can provide improved binding activity and selectvitiy11–14. In this context, a historical bias towards ‘flatland’ biphenyl products is usually observed with a para-connectivity15. Consequently, the development of a robust para-C−H arylation protocol to install biaryl units in complex drug molecules would allow rapid access to structural diversity and enhance the novel chemical space.

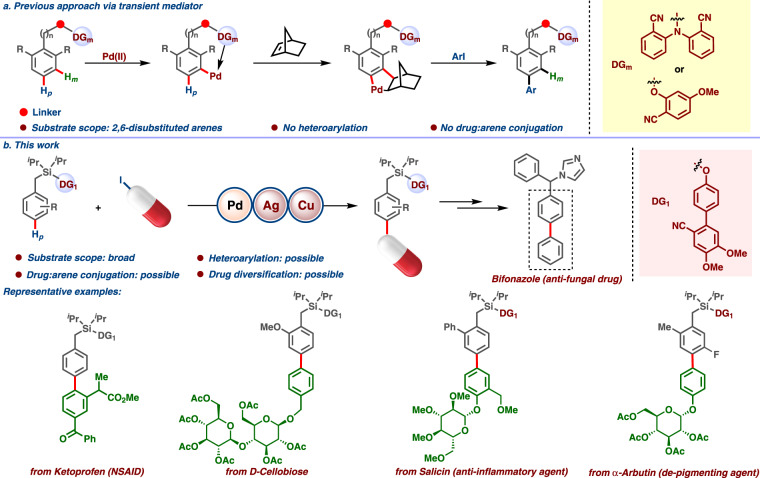

Druglike molecules present immediate challenges to the development of robust synthetic methodologies with transition metal catalysts. Drug moieties are commonly decorated with functionalities having Lewis basic heteroatoms16–18, which tend to impede catalytic activity19–21 or outcompete the directing group binding of the parent substrate22. As a result, efficient C−H activation protocols for the decoration and diversification of drugs are rare23. Nevertheless, the introduction of drug entities selectively at the ortho-position of arenes was recently demonstrated utilizing a directed C−H arylation protocol24,25. While ortho-substituted biaryls adopt non-planar conformations and experience restricted rotation, para-substitution results in flatland products associated with higher bioactivities15. In this endeavor, quite a few para-C−H arylation protocols of simple arenes have been developed by Gaunt26, Yu27, and Ye28. However, analogous directed C−H arylation protocols for availing such “flatland” biphenyls with para-connectivity remain elusive. Employing a transient mediator in substrates possessing a meta-directing group, para-arylation can be achieved29,30. However, the scope of these transformations is limited to 2,6-disubstituted arenes (Fig. 1a). This strategy is also not amenable to introducing heteroarene moieties, severely limiting its applicability in the preparation of pharmaceutically relevant fragments and drugs. Thus, the development of a general catalytic system is needed in which (i) the directing group (DG) outcompetes other Lewis basic atoms to bind the catalyst, and (ii) in which a stable macrocyclic intermediate required for DG-enabled para-C−H activation can be accessed31–35.

Fig. 1. Expanding chemical space by para-C−H arylation.

a Previous work using palladium/norbornene cooperative catalysis. b Present work using traceless directing group.

Herein, we describe a robust catalytic system for conjugating arenes with drug molecules at the para-position, creating unique biphenyl fragments.

Results

Reaction optimization

Exploratory studies began by attempting the para-arylation of toluene derivative 1a with 3-nitro iodobenzene. 1a consists of a benzyl part tethered to an easily removable cyano containing biphenyl moiety (DG1) by means of a silyl hinge (Fig. 1b). The incorporation of di-methoxy groups in DG1 was found to be advantageous36–39 (see Supplementary Information, Section 2.2 for further details). The para-arylation reaction initiated with Pd(OAc)2 and N-Ac-Gly in the presence of AgOAc as oxidant provided the desired product. However, substantial improvement both in yield and selectivity was achieved following further optimization of solvent and additives. Hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) solvent, which is beneficial in distal C−H activation, gave superior results to other solvents40. Although AgOAc showed promising results at early stages, extensive optimization studies through systematic alterations of different parameters led to the finding that a combination of Ag2SO4, Cu2Cr2O5, and LiOAc.2H2O, in appropriate proportion, gave the highest yield of para-arylated product. The regioselectivity could be further increased in favor of the desired para-arylated product by modifying the N-protecting group on the α-amino acid: Fmoc was found to enhance regioselectivity. An intriguing feature of these optimization studies was the influence of aryl iodide stoichiometry. A 1:1 ratio of aryl iodide to 1a gave the maximum yield and selectivity under these conditions.

Scope of the methodology

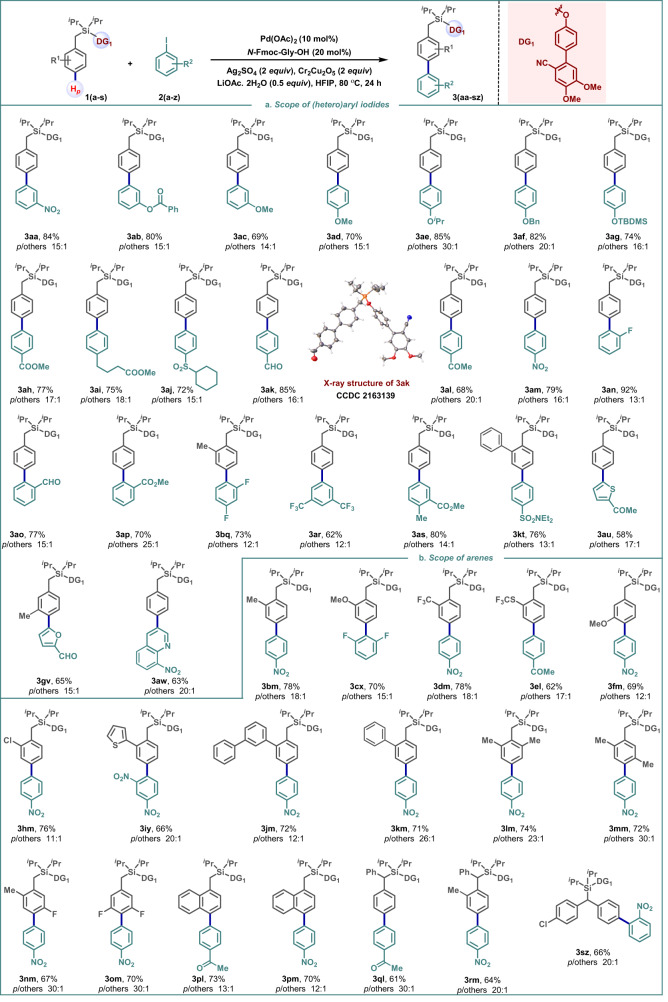

The optimized reaction conditions were then used to assess the potential of this protocol. 1a was subjected to para-arylation with several aryl iodides, focusing on those with heteroatoms and functional groups found in drugs and natural products (Fig. 2a). Gratifyingly, the protocol was tolerant of an array of protected phenol derivatives, providing the desired para-arylated products in synthetically useful yields and selectivity, irrespective of aryl iodide regiochemistry (3ab-3ag; Fig. 2a). Similarly, aryl iodides possessing ester, sulfoxide, and amide groups all underwent facile reactions (3ah, 3ai, 3aj, and 3kt; Fig. 2a). Functional groups vulnerable under oxidative conditions, viz. the formyl group, were also compatible under the present reaction conditions (3ak and 3ao; Fig. 2a). The reaction with 4-iodo benzyl alcohol furnished the same product 3ak (80%, para:others = 14:1) via in situ oxidation of the benzyl alcohol to a formyl group. Of significance are the high reactivities displayed by the ortho-substituted aryl iodides without compromising yields or selectivity despite the hindrance associated with their steric bulk (3an-3bq, Fig. 2a). The disubstituted aryl iodides with different substitution patterns were also competent substrates for para-arylation (3ar and 3as, Fig. 2a). Typically, the regioselective heteroarylation of arenes is challenging to promote because competitive binding impedes catalytic activity. Remarkably, however, heteroarylation with different N, O, S heterocycles such as thiophene, furan, and quinoline derivatives was achieved in good yields and fairly high selectivities (3au-3aw, Fig. 2a). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first instance of the distal para-heteroarylation process via C(sp2)−H activation.

Fig. 2. Scope of para-arylation.

a Scope of (hetero)aryl iodides. b Scope of substituted arenes. Reaction conditions: arene (1 equiv.), (hetero)aryl iodide (1 equiv.), Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%), N-Fmoc-Gly-OH (20 mol%), Ag2SO4 (2 equiv.), Cr2Cu2O5 (2 equiv.), LiOAc.2H2O (0.5 equiv.), HFIP, 80 °C, 24 h.

We next proceeded to examine the feasibility of para-arylation with a range of substituted arenes. An array of electronically diverse arenes possessing substituents at different positions were tolerated under the present reaction conditions (Fig. 2b). The electronic nature of the substituents did not significantly impact the yields of the corresponding para-arylated products. Functional groups at the ortho-position such as −Me, −OMe provided synthetically useful yields of their corresponding products with high para-selectivity (3bm and 3cx, Fig. 2b). Different fluorine-containing substituents such as −CF3 (3dm) and −SCF3 (3el) were equally compatible in this transformation. Substituents at the meta-position such as −OMe was well tolerated with this reaction protocol (3fm, Fig. 2b). Reactive functional groups such as −Cl (3hm), prone to undergo cross-coupling with aryl iodides, remained intact. The presence of thiophene (3iy), biphenyl (3jm), and phenyl (3km) systems did not hamper the desired reaction. The presence of 2,6-, 2,5-, and 3,5-substituents, including fluorine atoms, led to para-arylated products in high yields and excellent selectivity (3lm-3om, Fig. 2b). The use of a naphthalene system provided C4-selectivity (3pl and 3pm). The protocol was also applicable to toluene derivatives possessing α-substituents such as phenyl (3ql and 3rm) and substituted phenyl (3sz). In the case of α-phenyl substrate, arylation occurred at one of the phenyl rings (3ql and 3rm). In contrast to the above, the scope of para-arylation via a transient mediator is limited to 2,6-disubstituted arenes29,30.

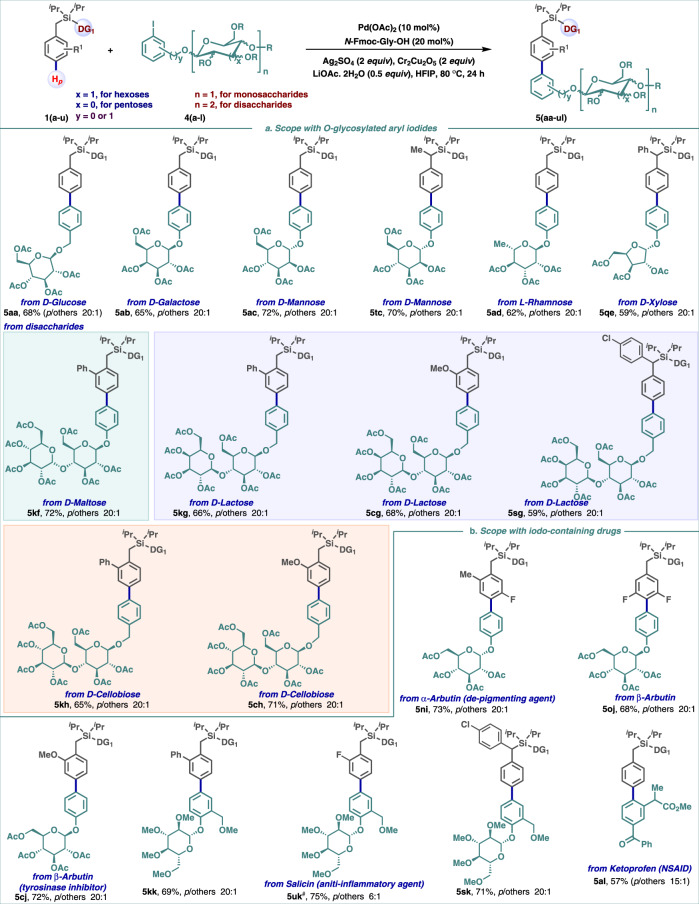

Encouraged by our protocol’s compatibility with heteroatoms and heteroaryl groups, we next explored the potential for the selective incorporation of drugs and natural products at the para-position. Synthetic phenol O-glycosylated small molecules play a significant role as biochemical probes and therapeutic agents41,42. Their innate properties could be subtlely modified by arylation of the phenol moiety of the glycoside43. To this aim, toluene derivatives were reacted with iodo-containing O-glycosylated phenols and iodo-benzyl alcohols (Fig. 3a). Strikingly, the presence of multiple heteroatoms in mono-saccharides such as D-glucose (5aa), D-galactose (5ab), D-mannose (5ac and 5tc), L-rhamnose (5ad), D-xylose (5qe); di-saccharides such as D-maltose (5kf), D-lactose (5kg, 5cg, and 5sg), and D-cellobiose (5kh and 5ch) did not impede reactivity due to catalyst interception. High compatibility with such a wide range of hexoses and pentoses is rare in the entire realm of C−H arylation protocols. These successful outcomes to generate a library of structurally diversified O-aryl glycosides demonstrate the versatility of the protocol. Further, iodo-containing pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals could be employed as efficient coupling partners for para-C−H arylation of toluene derivatives (Fig. 3b). Saccharide-based drugs such as α-arbutin (5ni), β-arbutin (5oj and 5cj), and salicin (5kk, 5uk, and 5sk) were selectively introduced into para-position of arenes in useful yields and high selectivity. Similarly, ketoprofen (5al), marketed as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), was amenable to the reaction conditions to afford biaryl systems. These observations are of compelling interest to the field of drug diversification by C−H activation. Also, such a conjugation process enables an expanded chemical space with a desirable “flatland” and a modulated bioactivity in parent drugs.

Fig. 3. Scope of para-arylation.

a Scope of the reaction with O-glycosylated aryl iodides. b Scope of para-C–H arylation with iodo-containing drugs. Reaction conditions: arene (1 equiv.), (hetero)aryl iodide (1 equiv.), Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%), N-Fmoc-Gly-OH (20 mol%), Ag2SO4 (2 equiv.), Cr2Cu2O5 (2 equiv.), LiOAc.2H2O (0.5 equiv.), HFIP, 80 °C, 24 h. # the isomer for 5uk was not separated clearly.

Application

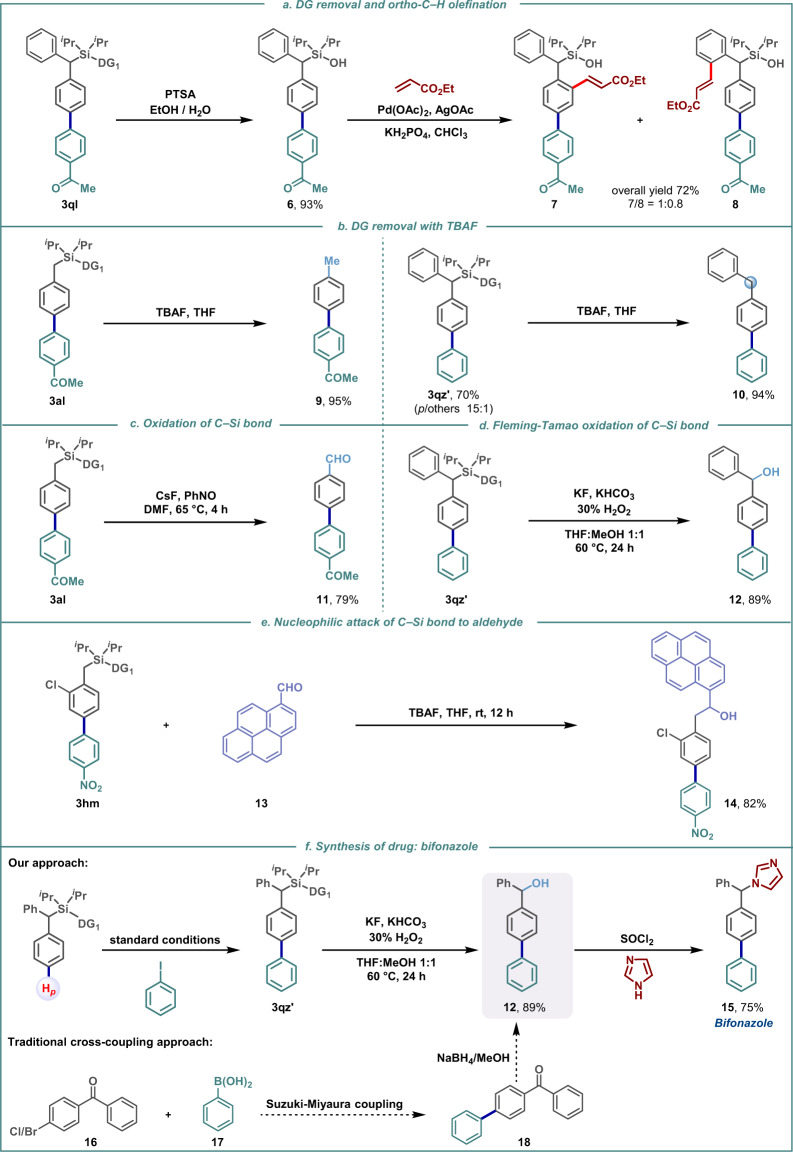

Removal of the directing group from the para-arylated product was achieved under mild conditions to afford the silanol (6, Fig. 4a). The potential of the silanol to act as an ortho-directing group was further exploited towards ortho-olefination (7 and 8, Fig. 4a). In an alternative approach, post para-arylation, treatment with tetrabutylammonium fluoride led to desilylation with the concomitant formation of para-arylated toluene and benzhydryl derivatives (9 and 10, Fig. 4b). Further, upon treatment with nitrosobenzene as an oxidant the C−Si bond of para-arylated product can be transformed into a valuable aldehyde (−CHO) functional group (11, Fig. 4c). Alternatively, the Fleming-Tamao oxidation of this C−Si bond of para-arylated product was able to deliver corresponding benzhydryl alcohol derivative, an important synthon for numerous drugs, natural products, and bio-active molecules (12, Fig. 4d)44. In the presence of TBAF the carbon atom of C−Si bond can also act as a potential nucleophile (Fig. 4e). The synthetic applicability was further elaborated by employing the para-arylated product to synthesize bifonazole, an antifungal drug (15, Fig. 4f). It is worth mentioning over here that the traditional method of synthesizing this drug molecule 15 uses Cl/Br-substituted benzophenone and expensive phenyl boronic acids which we are replacing by much cheaper iodo benzene in this protocol. The silyl linked DG can thus be viewed as a traceless DG that can be deleted or transformed into diverse functional groups.

Fig. 4. Applications.

a DG removal and ortho-C−H functionalization. b DG removal with TBAF. c Oxidation of C−Si bond. d Fleming-Tamao oxidation of C−Si bond. e Nucleophilic attack of C−Si bond to aldehyde. f Formal synthesis of bifonazole.

Mechanistic and computational studies

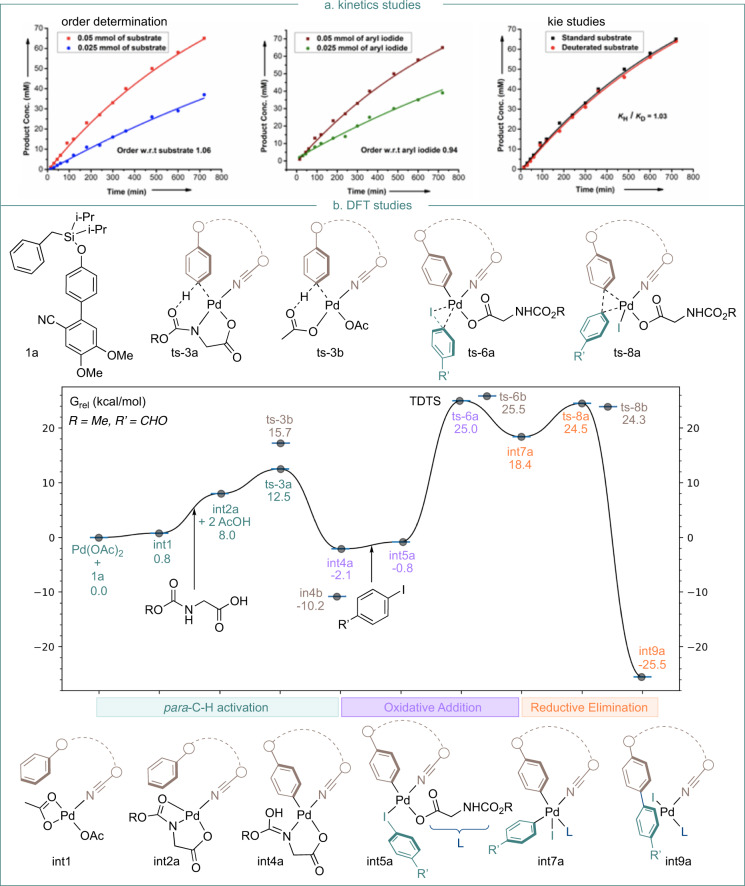

Mechanistic studies were undertaken to gain insight into this transformation. A first-order dependence with respect to both the substrate and aryl iodide was observed, implying their involvement in or before the turnover-determining transition state (TDTS) (Fig. 5a). In addition, the absence of a primary kinetic isotopic effect (KIE) was observed from parallel experiments with protiated and deuterated substrates 1a and 1a-d7 (kH/kD = 1.03), implying that C−H cleavage is not involved in the TDTS. Computational studies at the wB97XD/def2-TZVP//B3LYP/6–31G(d)+LANL08(f) level of theory with SMD solvation were used to obtain a Gibbs energy profile for the proposed catalytic cycle (Fig. 5b) (Calculations were performed with Gaussian 16 rev. B.01. Full computational details and references are given in the Supplementary Information). Consistent with the experiment, these calculations predict C−H activation (TS-1) to be relatively facile compared to the subsequent oxidative addition of the aryl iodide (TS-2), which is the highest barrier overall. This is proceeded by reductive elimination (TS-3) to yield the biaryl product and regenerate the Pd(II) catalyst to continue the cycle. Mono- and multi-metallic mechanisms have been studied computationally in Pd-catalyzed C−H activations with mono-N-protected amino acid (MPAA) ligands36,45. We considered both possibilities (see Supplementary Figs. 19, 20), finding that the mono-metallic pathway gave reasonable barriers which were also consistent with the observed regioselectivity.

Fig. 5. Mechanistic studies.

a Kinetic studies. b DFT studies [wB97XD/def2-TZVP//B3LYP/6-31G(d) + LANL08(f) computed Gibbs energy profile for the proposed mechanism of Pd-catalyzed para-C-H arylation reaction].

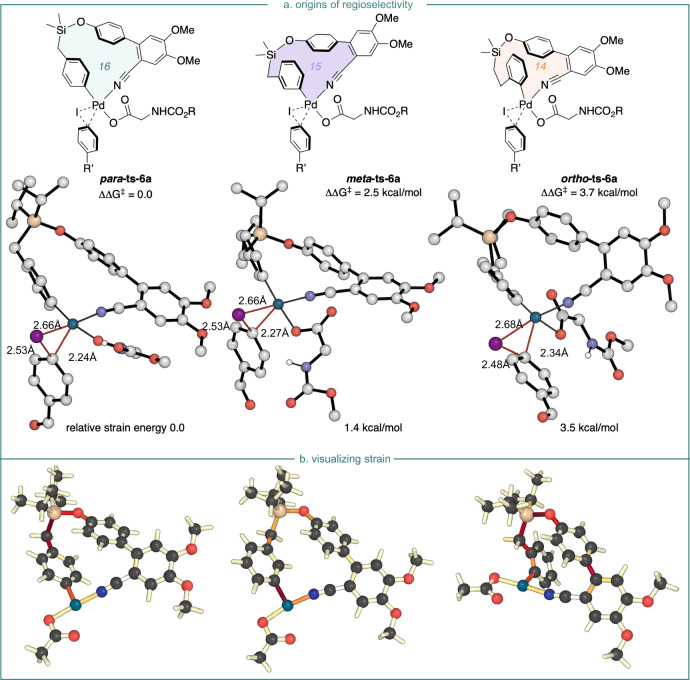

Without the MPAA ligand, para C−H activation occurs via transition state TS-3b with an activation barrier of 15.7 kcal/mol, forming intermediate int-4b in an exergonic process. Subsequently, the oxidative addition of aryl iodide onto Pd(II) species via transition state TS-6b with an energetic span of 35.7 kcal/mol leads to the formation of a Pd(IV) intermediate. This pathway would not occur under mild conditions. However, with the MPAA ligand, TS-3a contains a [5,6]-palladacycle conducive to C−H bond activation. The calculated free energy barrier of this step is 12.5 kcal/mol, in agreement with the absence of experimental KIE (measured kH/kD = 1.03). The oxidative addition of aryl iodide 2k is computed to occur in the turnover frequency-determining transition state with a barrier of 27.1 kcal/mol from int-6a. Since C−H activation is reversible, it is this oxidative addition step that determines regioselectivity (para over ortho or meta) for the overall reaction. Consistent with the experiment, the para-TS6a is 2.5 and 3.7 kcal/mol more stable than the meta- and ortho-TS6a in Fig. 6a, respectively. The site selectivity results from differing ring strain in the palladacyclic TS, which is minimized in the para pathway. The relative macrocyclic ring strain energies in ortho, meta, and para TS structures were evaluated using isodemic reactions (Fig. 6a). These studies suggest that relative to the 16-membered para-TS, the 15-membered meta-TS is destabilized by 1.4 kcal/mol and the 14-membered ortho-TS is destabilized by 3.5 kcal/mol. Visualization of cyclic strain energies (Fig. 6b) was performed for 14,15- and 16-membered palladacycles using StrainViz. This analysis suggests that the meta-structure incurs additional strain around the Pd-center, and that in the ortho-structure, the biaryl fragment of the directing group experiences additional strain, relative to the more favorable para-structure.

Fig. 6. Computational analysis of regioselectivity.

a Optimized geometries and corresponding relative Gibbs free energies (kcal/mol) for the para-, meta-, and ortho-TSs in the turnover-determining step. Ring-strain energies are defined by an isodesmic reaction. b Visualization of ring strain with StrainViz. Bonds bearing high strain are shown in red.

Discussion

In summary, we have developed a robust strategy for para-C−H arylation employing a removable directing group. The protocol is tolerant of diverse functionalities in arenes and aryl iodides, irrespective of their orientation. Noteworthy, this transformation is amenable in introducing even the heteroarenes selectively at the distal para-position, the first report of its kind. Furthermore, aryl iodides containing O-glycosides such as mono and di-saccharides were selectively installed at the para-position without any hindrance in the catalytic activity. The protocol also paves the path for drug diversification by forming preferred para-connected ‘flatland’ biaryls in various marketed drugs. Post-functionalization removal of the directing group was carried out under mild conditions and further utilized for iterative functionalization of arene with increased aromatic content. The protocol has also been utilized for a concise synthesis of drug molecules. The compatibility of this protocol with diverse functional groups renders the method suitable for streamlining drug development by expanding the chemical space. The reaction mechanism involves relatively facile and reversible C−H activation, followed by turnover-limiting oxidative insertion into the aryl iodide and then reductive elimination to yield the biaryl product. The high levels of regiocontrol for the para-product result from the minimization of strain in the macrocyclic template, which is 1.4–3.5 kcal/mol larger in the competing regioisomeric pathways.

Methods

Palladium-catalyzed para-C−H arylation

In an oven-dried screw cap reaction tube charged with a magnetic stir bar was added Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%), Fmoc-Gly-OH (20 mol%), Ag2SO4 (2 equiv.), Cu2Cr2O5 (2 equiv.) and LiOAc.2H2O (0.5 equiv.). After that, benzylsilyl ether substrate (0.1 mmol, 1 equiv.) and aryl iodide (1 equiv.) were added. Subsequently, 1 mL of 1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) was added with a disposable laboratory syringe under aerobic conditions. The tube was placed in a preheated oil bath at 80 °C, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 24 h. The reaction mixture was then cooled to room temperature and filtered through a celite pad with ethyl acetate. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo, and the resulting residue was purified by silica gel (100–200 mesh size) column chromatography to give the desired product.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

Financial support received from SERB; India is gratefully acknowledged (CRG/2018/003951). Financial support received from UGC-India (fellowship to S.M. and T.B.), IIT Bombay (S.G. and S.S.), and (J. C. Bose Fellowship to G.K.L) is gratefully acknowledged. R.S.P. acknowledges support from the NSF (CHE-1955876) and computational resources from the RMACC Summit supercomputer supported by the National Science Foundation (ACI-1532235 and ACI-1532236), the University of Colorado Boulder and Colorado State University, and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) through allocation TG-CHE180056.

Author contributions

S.M., G.K.L., and D.M. conceived the concept. S.M., S.S., and T.B. performed the reactions, analyzed the products, and carried out the kinetics studies. Y.L. carried out the computational studies. R.S.P. supervised the computational studies. D.M. supervised the experimental work. S.M., S.G., Y.L., G.K.L., R.S.P., and D.M. wrote the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Genping Huang, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. The experimental procedures and characterization of all new compounds are provided in Supplementary Information file. For the computed stationary points and Cartesian coordinates, see Supplementary Data 1 file.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

8/25/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41467-022-32720-3

Contributor Information

Goutam Kumar Lahiri, Email: lahiri@chem.iitb.ac.in.

Robert S. Paton, Email: robert.paton@colostate.edu

Debabrata Maiti, Email: dmaiti@iitb.ac.in.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-31506-x.

References

- 1.Wencel-Delord J, Glorius F. C–H bond activation enables the rapid construction and late-stage diversification of functional molecules. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:369–375. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cernak T, Dykstra KD, Tyagarajan S, Vachalb P, Krskab SW. The medicinal chemist’s toolbox for late stage functionalization of druglike molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:546–576. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00628g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMurray L, O’Hara F, Gaunt MJ. Recent developments in natural product synthesis using metal-catalysed C–H bond functionalisation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:1885–1898. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15013h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamaguchi J, Yamaguchi AD, Itami K. C–H bond functionalization: emerging synthetic tools for natural products and pharmaceuticals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:8960–9009. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abrams DJ, Provencher PA, Sorensen EJ. Recent applications of C–H functionalization in complex natural product synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47:8925–8967. doi: 10.1039/c8cs00716k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roughley SD, Jordan AM. The medicinal chemist’s toolbox: an analysis of reactions used in the pursuit of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:3451–3479. doi: 10.1021/jm200187y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker A, Kettle JG, Nowak T, Pease JE. Expanding medicinal chemistry space. Drug. Discov. Today. 2013;18:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boström J, Brown DG, Young RJ, Keserü GM. Expanding the medicinal chemistry synthetic toolbox. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018;17:709–727. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown DG, Boström J. Analysis of past and present synthetic methodologies on medicinal chemistry: where have all the new reactions gone? J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:4443–4458. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer EA, Castellano RK, Diederich F. Interactions with aromatic rings in chemical and biological recognition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:1210–1250. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robichaud J, et al. A novel class of nonpeptidic biaryl inhibitors of human cathepsin K. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:3709–3727. doi: 10.1021/jm0301078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang X, Lee C-L, Zhao J, Toone EJ, Zhou P. Synthesis, structure, and antibiotic activity of aryl-substituted LpxC inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:6954–6966. doi: 10.1021/jm4007774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer C, et al. Improvement of σ 1 receptor affinity by late-stage C–H-bond arylation of spirocyclic lactones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:1844–1856. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kokornaczyk A, Schepmann D, Yamaguchi Y, Itami K, Wünsch B. Microwave-assisted regioselective direct C–H arylation of thiazole derivatives leading to increased σ 1 receptor affinity. Med. Chem. Commun. 2016;7:327–331. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown DG, Gagnon MM, Boström J. Understanding our love affair with p-chlorophenyl: present day implications from historical biases of reagent selection. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:2390–2405. doi: 10.1021/jm501894t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitaku E, Smith DT, Njardarson JT. Analysis of the structural diversity, substitution patterns, and frequency of nitrogen heterocycles among US FDA-approved pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:10257–10274. doi: 10.1021/jm501100b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith BR, Eastman CM, Njardarson JT. Beyond C, H, O, and N! Analysis of the elemental composition of US FDA approved drug architectures. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:9764–9773. doi: 10.1021/jm501105n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilardi EA, Vitaku E, Njardarson JT. Data-mining for sulfur and fluorine: an evaluation of pharmaceuticals to reveal opportunities for drug design and discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:2832–2842. doi: 10.1021/jm401375q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busacca, C. A., Fandrick, D. R., Song, J. J. & Senanayake, C. H. In Applications of Transition Metal Catalysis in Drug Discovery and Development: An Industrial Perspective (eds Crawley, M. L. & Trost, B. M.) 1–25 (Wiley, New York, 2012).

- 20.Larsen MA, Hartwig JF. Iridium-catalyzed C–H borylation of heteroarenes: scope, regioselectivity, application to late-stage functionalization, and mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:4287–4299. doi: 10.1021/ja412563e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malik HA, et al. Non-directed allylic C–H acetoxylation in the presence of Lewis basic heterocycles. Chem. Sci. 2013;5:2352–2361. doi: 10.1039/C3SC53414F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y-J, et al. Overcoming the limitations of directed C–H functionalizations of heterocycles. Nature. 2014;515:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nature13885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nadin A, Hattotuwagama C, Churcher I. Lead-oriented synthesis: a new opportunity for synthetic chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:1114–1122. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simonetti M, Cannas DM, Just-Baringo X, Vitorica-Yrezabal IJ, Larrosa I. Cyclometallated ruthenium catalyst enables late-stage directed arylation of pharmaceuticals. Nat. Chem. 2018;10:724–731. doi: 10.1038/s41557-018-0062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai H-X, Stepan AF, Plummer MS, Zhang Y-H, Yu J-Q. Divergent C−H functionalizations directed by sulfonamide pharmacophores: Late-stage diversification as a tool for drug discovery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:7222–7228. doi: 10.1021/ja201708f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ciana C-L, Phipps RJ, Brandt JR, Meyer F-M, Gaunt MJ. A highly para-selective copper(II)-catalyzed direct arylation of aniline and phenol derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:458–462. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, Leow D, Yu J-Q. Pd(II)-Catalyzed para-Selective C−H arylation of monosubstituted arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:13864–13867. doi: 10.1021/ja206572w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luan Y-X, et al. Amide-ligand-controlled highly para-selective arylation of monosubstituted simple arenes with arylboronic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:1786–1789. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b12907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi H, et al. Differentiation and functionalization of remote C−H bonds in adjacent positions. Nat. Chem. 2020;12:399–404. doi: 10.1038/s41557-020-0424-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dutta U, et al. Para-selective arylation of arenes: a direct route to biaryls by norbornene relay palladation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:20831–20836. doi: 10.1002/anie.202005664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dutta U, Maiti S, Bhattacharya T, Maiti D. Arene diversification through distal C(sp2)−H functionalization. Science. 2021;372:701–716. doi: 10.1126/science.abd5992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meng G, et al. Achieving site-selectivity for C−H activation processes based on distance and geometry: a carpenter’s approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:10571–10591. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c04074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bag S, et al. Remote para-C−H functionalization of arenes by a D-shaped biphenyl template-based assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:11888–11891. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li M, et al. Remote para-C−H acetoxylation of electron-deficient arenes. Org. Lett. 2019;21:540–544. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen X, et al. Palladium-catalyzed remote para-C−H activation of arenes assisted by a recyclable pyridine-based template. Chem. Sci. 2021;12:4126–4131. doi: 10.1039/d0sc07042d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maji A, et al. Experimental and computational exploration of para-selective silylation with a hydrogen-bonded template. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:14903–14907. doi: 10.1002/anie.201708449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maji A, et al. H-bonded reusable template assisted para-selective ketonisation using soft electrophilic vinyl ethers. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3582–3592. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06018-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pimparkar S, et al. Para-selective cyanation of arenes by H-bonded template. Chem. Eur. J. 2020;26:11558–11564. doi: 10.1002/chem.202001368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dutta U, et al. Rhodium catalyzed template-assisted distal para-C−H olefination. Chem. Sci. 2019;10:7426–7432. doi: 10.1039/c9sc01824g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leow D, Li G, Mei T-S, Yu J-Q. Activation of remote meta-C−H bonds assisted by an end-on template. Nature. 2012;486:518–522. doi: 10.1038/nature11158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moradi SV, Hussein WM, Varamini P, Simerska P, Toth I. Glycosylation, an effective synthetic strategy to improve the bioavailability of therapeutic peptides. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:2492–2500. doi: 10.1039/c5sc04392a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paradís-Bas M, Tulla-Puche J, Albericio F. The road to the synthesis of difficult peptides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:631–654. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00680e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wadzinski TJ, et al. Rapid phenolic O-glycosylation of small molecules and complex unprotected peptides in aqueous solvent. Nat. Chem. 2018;10:644–652. doi: 10.1038/s41557-018-0041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vardanyan, R. & Hruby, V. in Synthesis of Best-Seller Drugs, Ch. 16, 247–263 (Elsevier, 2016).

- 45.Gair JJ, Haines BE, Filatov AS, Musaev DG, Lewis JC. Mono-N-protected amino acid ligands stabilize dimeric palladium(II) complexes of importance to C−H functionalization. Chem. Sci. 2017;8:5746–5756. doi: 10.1039/c7sc01674c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. The experimental procedures and characterization of all new compounds are provided in Supplementary Information file. For the computed stationary points and Cartesian coordinates, see Supplementary Data 1 file.