Abstract

The human placenta represents a unique non-neuronal site of monoamine transporter expression, with pathophysiological relevance during the prenatal period. Monoamines (serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine) are crucial neuromodulators for proper placenta functions and fetal development, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and neuronal migration. Accumulating evidence suggests that even a transient disruption of monoamine balance during gestation may lead to permanent changes in the fetal brain structures and functions, projecting into adulthood. Nonetheless, little is known about the transfer of dopamine and norepinephrine across the placental syncytiotrophoblast. Employing the method of isolated membranes from the human term placenta, here we delineate the transport mechanisms involved in dopamine and norepinephrine passage across the apical microvillous (MVM) and basal membranes. We show that the placental uptake of dopamine and norepinephrine across the mother-facing MVM is mediated via the high-affinity and low-capacity serotonin (SERT/SLC6A4) and norepinephrine (NET/SLC6A2) transporters. In the fetus-facing basal membrane, however, the placental uptake of both monoamines is controlled by the organic cation transporter 3 (OCT3/SLC22A3). Our findings thus provide insights into physiological aspects of dopamine and norepinephrine transport across both the maternal and fetal sides of the placenta. As monoamine transporters represent targets for several neuroactive drugs such as antidepressants, our findings are pharmacologically relevant to ensure the safety of drug use during pregnancy.

Subject terms: Transporters in the nervous system, Endocrinology

Introduction

The human placenta represents a unique non-neuronal site for the metabolism and transport of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. As messengers on the placenta-brain axis1, these monoamine neurotransmitters play essential roles in fetal development and programming. In the early fetal brain, monoamine receptors develop before the inception of synaptogenesis, highlighting their relevance for behavioral development2. In addition, they participate in cell proliferation and differentiation processes, neurite outgrowth, modulation of the cell cycle, and neuronal migration3–7. Moreover, norepinephrine is a pivotal monoamine for the fetal cardiovascular system, lung function, and glucose mobilization8,9 and plays a detrimental role in postnatal adaptation8. On the other hand, dopamine affects placental endocrine functions by regulating the production of human placental lactogen and chorionic gonadotropin10,11.

Accumulating evidence suggests that even a transient disruption of monoamine balance during gestation may lead to permanent changes in the fetal brain structures and functions, projecting into adulthood1. Altered dopamine homeostasis is linked to higher risks of neurological disorders, such as schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder, bipolar affective, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder after birth7,12,13. In addition, monoamines are vasoactive agents, and inappropriate levels have been related to changes in uterine blood flow, resulting in hypoxia and preterm delivery14,15. Thus, the placental transport of monoamines has crucial pathophysiological importance during the prenatal period.

Specific transport proteins of the solute carrier family (SLC) serve as the primary mechanism for the active uptake of monoamines into cells. The three neuronal monoamine transporters—serotonin transporter (SERT/SLC6A4), norepinephrine transporter (NET/SLC6A2), and dopamine transporter (DAT/SLC6A3)—are high-affinity, low-capacity membrane transporters, driven by an inward Na+/Cl− gradient and an outward K+/H+ gradient16–18. However, their substrate specificity is not unambiguous, and a significant overlap exists in substrate affinity19,20. In addition, a low-affinity but high-capacity organic cation transporter 3 (OCT3/SLC22A3), also known as the extraneuronal monoamine transporter, mediates monoamine uptake in the brain21,22. To some extent, monoamines can also pass biological membranes by passive diffusion23,24.

The functional unit of the human placenta is the syncytiotrophoblast—an epithelial layer polarized into the apical, maternal-facing microvillous membrane (MVM) and basal, fetal-facing membrane (BM)25. Current knowledge of monoamine transport in the placenta is restricted to the MVM, where functional expression of SERT and NET was reported26,27. Several studies have failed to detect DAT in placental cells28–30, speculating that dopamine must use different transport system(s) to enter the placenta from the maternal circulation. Surprisingly, despite increasing fetal monoamine production towards the term15, limited evidence exists on the transport of monoamines across the BM. Our team has recently characterized a serotonin clearance mechanism in the human and rat placenta, mediated by SERT in the MVM and OCT3 in the BM; this synchronized transporter activity in conjunction with the intracellular metabolism by monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) regulates serotonin levels in the fetoplacental unit31. Nonetheless, little is known about the placental handling of dopamine and norepinephrine. The only other report of this kind dates back to 1984; it indicates a non-specific extraction of norepinephrine from the fetal circulation, followed by enzymatic degradation via MAO-A and catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT)32. As OCT3 in neuronal tissues exhibits affinity for dopamine and norepinephrine33, we hypothesized that OCT3 might also be responsible for placental uptake of these monoamines from the fetal circulation.

Thus, in the present study, we aimed to characterize dopamine and norepinephrine transport in the human placental syncytiotrophoblast. Experiments were conducted in purified MVM and BM vesicles simultaneously isolated from the human term placenta, providing an ideal system to investigate transport characteristics of both membranes in parallel. Collectively, our findings provide insights into physiological aspects of dopamine and norepinephrine transport across the placenta. As monoamine transporters represent targets for several neuroactive drugs, typically antidepressants, our findings are pharmacologically relevant to ensure the safety of drug use during pregnancy.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

3H-norepinephrine, 20 Ci/mmol, 3H-serotonin, 80 Ci/mmol, and 3H-dopamine, 60 Ci/mmol were purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dopamine hydrochloride, norepinephrine hydrochloride, serotonin hydrochloride, sodium L-ascorbate, paroxetine hydrochloride, venlafaxine hydrochloride, nisoxetine hydrochloride, GBR 12935 dihydrochloride, decynium-22 and hydrocortisone were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Tri Reagent solution was obtained from the Molecular Research Centre (Cincinnati, OH, USA). Bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA assay) reagents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, MA, USA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Human term placenta sample collection

Term placentas from uncomplicated pregnancies (gestational age at delivery between 39 and 40 weeks) were collected at the University Hospital in Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic. All the experiments conducted in the study conformed to the ethical standards established by the Declaration of Helsinki, and all the women provided signed informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the University Hospital Research Ethics Committee (201006 S15P).

RNA isolation from human term placenta and reverse transcription

According to the manufacturer's instructions, RNA was isolated from weighed placenta tissue samples using the Tri Reagent solution (Molecular Research Center, Cinncinati, OH, USA). Total RNA concentration and purity were calculated using NanoDrop™ 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). 1 µg of total RNA was reversely transcribed to cDNA in a total volume of 20 µl using the iScript Advanced cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and Bio-Rad T100™ Thermal Cycler (Hercules, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Absolute quantification of DAT, NET, SERT, and OCT3 transcripts in human term placenta

The quantification of monoamine transporter expression in human term placentas was investigated using duplex droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) analysis, as described previously31. Briefly, the duplex reaction mixture consisted of 10 µL ddPCR™ Supermix for probes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), 1 µL of the predesigned probe assay (target gene—FAM, reference gene—HEX), and 1 µL of cDNA (25 ng/µL), in a total volume 20 µL. Expression levels of the following target genes were quantified: NET/SLC6A2 (Hs00426573_m1), DAT/SLC6A3 (Hs00997374_m1), SERT/SLC6A4 (Hs00984349_m1), and OCT3/SLC22A3 (Hs01009571_m1)—all TaqMan assays were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, MA, USA). On the other hand, β-2 microglobulin (B2M) was used as the reference gene, obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA; dHsaCPE5053101). Droplets were created using QX200 Droplet Generator and amplified to the endpoint using the T100™ Thermal Cycler, following the thermal conditions recommended by the manufacturer. Droplets were counted in QX200™ Droplet Reader, and the concentration of the target gene was calculated using the QuantaSoft™ Software. Only samples with more than 13 000 generated droplets were used for final data analysis. Expression levels are reported in the number of transcripts/ng of transcribed RNA. The whole system for ddPCR reaction and analysis was obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA).

Preparation of microvillous and basal membrane vesicles from human term placenta

Syncytiotrophoblast plasma membranes were simultaneously prepared from fresh healthy term placentas as described previously31. Briefly, maternal decidua and chorionic plate were removed. Next, placental villous tissue (80–100 g) was chopped into small pieces and washed with 0.9% NaCl to remove blood. The purification method involved different steps: homogenization, differential centrifugation, precipitation of non-microvillous membranes with Mg2+, and a sucrose gradient step. Microvillous membranes (MVM) and basal membranes (BM) were resuspended in intravesicular buffer (290 mM sucrose, 5 mM Hepes, 5 mM Tris; pH 7.4) and vesiculated by 15 passages through a 25-gauge needle. Protein concentration in the placental homogenate, MVM, and BM vesicles, was analyzed using the BCA assay.

The purity and enrichment of MVM were determined enzymatically by assaying the activity of alkaline phosphatase, according to a well-established protocol34. β-adrenergic receptor expressed in the basal membrane was assayed as a basal membrane marker by measuring [3H]dihydroalprenolol, levo-[propyl-1,2,3–3H] hydrochloride binding35. Purity and enrichment results are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Monoamine uptake by microvillous and basal membrane vesicles

3H-dopamine, 3H-norepinephrine, and 3H-serotonin uptake by syncytiotrophoblast vesicles (MVM or BM) was performed using the MultiScreen™ Vacuum Manifold 96-well system. Briefly, 3 µL of extravesicular buffer (5 mM Tris, 5 mM HEPES, 145 mM NaCl; pH 7.4) were added into 3 µL of MVM or BM vesicles (10 mg/ml) at room temperature. Uptake was initiated by adding 3 µL of 3H-dopamine, 20 µCi/ml (112 nM) or 3H-norepinephrine, 20 µCi/ml (332 nM) or 3H-serotonin, 24 µCi/ml (100 nM). Uptake was stopped after 1 min or pre-defined time points (time-dependency studies), by adding 200 µL of ice-cold stop solution (130 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 4.2 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 0.75 mM CaCl2; pH 7.4), consequently, transferred into 1 800 µL stop solution and filtered through a 0.45 µm mixed cellulose ester filter (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA; cat. no. MAHAS4510). Finally, filters were washed ten times with 300 µL of stop solution and cut using the MultiScreen Multiple Punch system (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Protein-free controls were analyzed in parallel to determine tracer binding to the filter, and this background value was subtracted from the total vesicle count.

For concentration-dependent uptake and interaction studies, 3H-dopamine, 3H-norepinephrine, and 3H-serotonin were used as a tracer. The total substrate concentration was supplemented with increasing levels of unlabelled dopamine hydrochloride, norepinephrine hydrochloride, or serotonin hydrochloride. To assess 3H-dopamine or 3H-norepinephrine binding and/or diffusion in MVM and BM vesicles, uptake experiments were performed at 4 °C at 0 and 1 min incubation times, respectively. On the other hand, to evaluate the effect of intracellular K+ on 3H-dopamine or 3H-norepinephrine uptake, vesicles were preloaded with 140 mM KCl overnight at 4 °C before the uptake experiments.

The effect of specific transport inhibitors on 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine uptake was assessed by preincubating MVM and BM vesicles with the selected inhibitors for 10 min at room temperature. Subsequently, 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine uptake was assayed in the presence of the inhibitor. The following inhibitors were used: paroxetine 100 µM (SERT, OCT3 inhibitor)36, venlafaxine 100 µM (SERT, NET inhibitor)37, nisoxetine 20 nM (NET inhibitor)37, GBR 12935 50 nM (DAT inhibitor)38, hydrocortisone 100 µM (OCT3 inhibitor)33, and decynium-22 10 µM (OCT3 inhibitor)39. Inhibitors' concentrations were chosen based on previously published data33,36,40,41.

Radioisotope analysis

Filter-associated concentrations of 3H-norepinephrine, 20 Ci/mmol, 3H-serotonin, 80 Ci/mmol, and 3H-dopamine, 60 Ci/mmol were measured by liquid scintillation counting using a Tri-Carb 2910 TR instrument. Non-specific tracer binding to the filter was determined by measuring protein-free controls.

Statistical analysis

The effect of incubation temperature and intracellular K+ on 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine uptake by MVM and BM was assessed by the Mann–Whitney test. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to evaluate the effect of inhibitors on 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine uptake by MVM and BM. IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) values for monoamine interactions were obtained by fitting concentration-inhibition curves through nonlinear regression analysis. All statistical analyses were implemented in GraphPad prism 9.3.1 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Asterisks in the figures indicate significance levels: * (p ≤ 0.05), ** (p ≤ 0.01), and *** (p ≤ 0.001).

Results

Quantification of monoamine transporter transcripts in the human term placenta

ddPCR analysis was employed to determine and compare the transcript levels of monoamine transporters in the human term placenta (Table 1). NET expression was predominant among the four monoamine transporters tested, albeit revealing a high inter-individual variability. SERT and OCT3 showed comparable expression levels, whereas DAT expression in whole placental tissue was negligible, with transcript levels below 0.2 transcripts/ng RNA.

Table 1.

Absolute quantification of monoamine transporter gene transcripts in the human term placenta (gestational age at delivery: 39–40).

| Gene | Aliases | Transcripts/ng RNA |

|---|---|---|

| SLC6A2 | NET | 24.20 (14.28–60.26) |

| SLC6A3 | DAT | 0.071 (0.030–0.177) |

| SLC6A4 | SERT | 16.00 (10.50–27.50) |

| SLC22A3 | OCT3 | 5.00 (3.50–7.50) |

Target genes were amplified to the endpoint in a duplex ddPCR system, yielding high-precision quantification.

The final output is reported as target transcripts/ng RNA.

The results are shown as median with interquartile range, n ≥ 12.

Dopamine and norepinephrine uptake by microvillous and basal membrane vesicles isolated from human placental syncytiotrophoblast

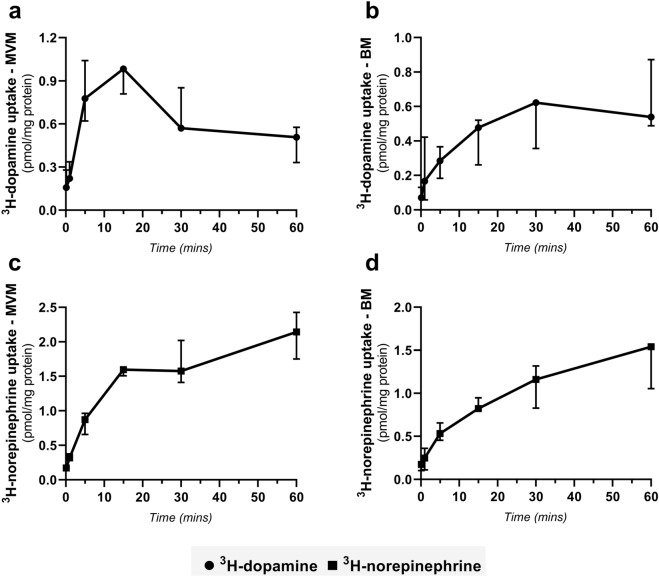

To characterize dopamine and norepinephrine transport across placental membranes, we conducted uptake studies using ex vivo separately isolated human placenta membrane vesicles (MVM—maternal facing and BM—fetal facing). The time course of 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine uptake was determined at pH 7.4 over a period of 20 s to 60 min. As shown in Fig. 1, both membranes exhibited time-dependent 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine accumulation. Contrary to 3H-norepinephrine, whose uptake increases with time (Fig. 1c), 3H-dopamine accumulation by MVM vesicles exhibited the “overshoot phenomenon” (Fig. 1a), previously reported for Na+-dependent transporters29. At the peak of the overshoot (15 min), the intravesicular 3H-dopamine concentration was 1.97 times higher than at 60 min. On the other hand, uptake of 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine by BM vesicles was fast and increased with time, reaching equilibrium in 60 min (Fig. 1b, d). Based on these results, a one-minute uptake was selected for subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

Time-course of 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine uptake into MVM and BM vesicles isolated from human term placenta. Vesicle fractions were incubated at room temperature with 112 nM 3H-dopamine (a, b) and 332 nM 3H-norepinephrine (c, d), pH 7.4. The vesicular uptake is presented as pmol/mg protein, and data are shown as median with interquartile range, n = 3.

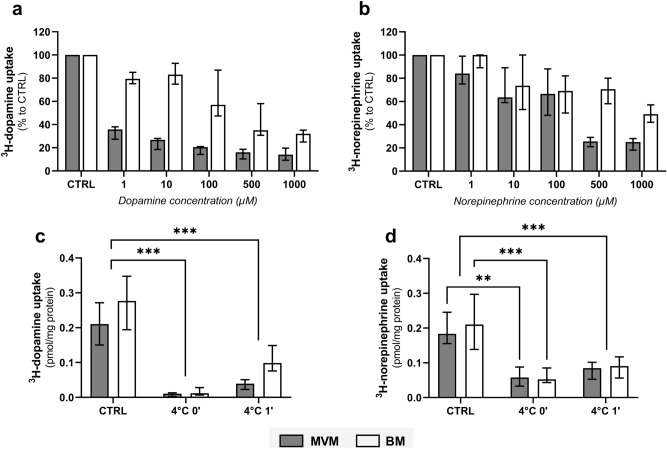

Subsequently, we evaluated the effect of increasing substrate concentration on the intravesicular accumulation of 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine, indicating a transporter-mediated uptake mechanism. However, at a concentration range of 1 to 1000 µM, we observed different saturation kinetics between both membranes (Fig. 2a, b). When comparing transporter saturation between MVM and BM, the uptake of 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine was more profoundly affected in MVM. These findings indicate that different monoamine transport systems of differing capacities are present on maternal vs fetal side of the placenta. Nonetheless, even at the highest substrate concentration used, we were not able to completely block 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine uptake by MVM, and especially BM (Fig. 2a, b). Thus, to evaluate the possibility of non-specific radioisotope binding to the membrane vesicles and/or involvement of passive diffusion, uptake of 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine was carried out at 4 °C for 0 and 1 min. Figure 2c shows that 3H-dopamine uptake by both membranes at time 0 is negligible. In contrast, compared to control experiments conducted at room temperature, one-minute uptakes at 4 °C recorded 17.9% and 36.3% 3H-dopamine accumulation in MVM and BM, respectively (Fig. 2c). This feature suggests potential radioisotope binding and/or a passive diffusion component in the uptake, and this effect is higher in BM vesicles. On the other hand, the fraction of 3H-norepinephrine uptake into membrane vesicles at 4 °C was similar in both membranes, regardless of the time (Fig. 2d). This indicates a comparable factor of unspecific 3H-norepinephrine binding to the vesicles and/or passive diffusion in both MVM and BM. These findings can explain the unsaturated fraction of 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine transport across placental membranes observed in Fig. 2a, b.

Figure 2.

Characterization of 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine uptake kinetics into MVM and BM vesicles isolated from human term placenta. Initial uptake rates (CTRL) were determined in vesicles incubated with 112 nM 3H-dopamine (a, c) and 332 nM 3H-norepinephrine (b, d) at room temperature for 1 min. Concentration-dependent analysis of 3H-dopamine (a) and 3H-norepinephrine (b) uptakes were evaluated at a range of 1–1000 µM unlabelled substrate concentration. Subsequently, the contribution of non-specific radioisotope binding and/or passive diffusion was determined by analyzing uptake rates of 3H-dopamine (c) and 3H-norepinephrine (d) transport at 4 °C (for 0 and 1 min). Results are presented as percent uptake relative to CTRL or as pmol/mg protein. Data are shown as median with interquartile range, n = 4. Statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA: **(p ≤ 0.01), ***(p ≤ 0.001).

Effect of intracellular K+ on dopamine and norepinephrine uptake by placental microvillous and basal membrane vesicles

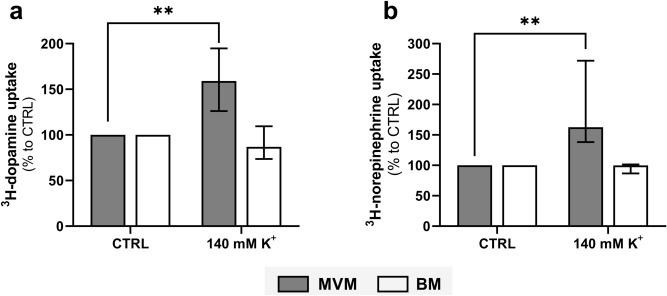

To distinguish between the neuronal (DAT, NET, SERT) and extraneuronal (OCT3) monoamine transporters in MVM and BM, we investigated the effect of intracellular K+ on dopamine and norepinephrine uptake. This is because neuronal monoamine transporters are driven by an extracellular Na+/Cl− and an intracellular K+/H+ concentration gradient. Furthermore, substrate uptake by DAT and NET is reportedly voltage-dependent due to the transient nature of intracellular K+ binding42. We observed that overnight loading of MVM vesicles with 140 mM K+ significantly increased the uptake of 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine (Fig. 3a). On the other hand, radioisotope accumulation in BM was unaffected by the intracellular K+ concentration (Fig. 3b). These results confirm the presence of different catecholamine transport mechanisms in MVM and BM vesicles, with the MVM displaying an electrogenic transport system for dopamine and norepinephrine.

Figure 3.

The effect of intracellular K+ on monoamine uptake systems in MVM and BM vesicles isolated from human term placenta. Uptake of 3H-dopamine (a) and 3H-norepinephrine (b) was determined in membrane vesicles preloaded overnight with 140 mM K+. Results are presented as percent uptake relative to the unloaded vesicles (CTRL). Data are expressed as median with interquartile range, n = 4. Statistical analyses were performed using Mann–Whitney test: **(p ≤ 0.01).

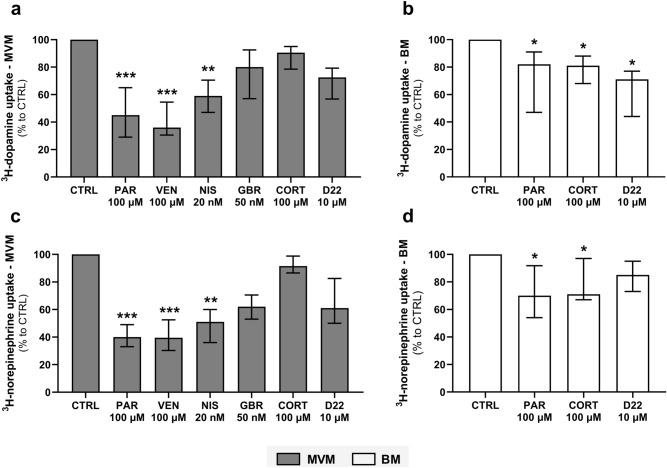

Identification of dopamine and norepinephrine transport systems in MVM and BM using specific transport inhibitors

A selection of monoamine transporter inhibitors was assayed to further characterize the transporters responsible for dopamine and norepinephrine uptake by MVM and BM vesicles. Since there is no involvement of neuronal transporters (NET, DAT, SERT) in the BM, only inhibitors related to the extraneuronal transport system (OCT3) were tested in this membrane. We found that paroxetine, venlafaxine, and nisoxetine significantly inhibit 3H-dopamine (Fig. 4a) and 3H-norepinephrine (Fig. 4c) uptake by the MVM vesicles. These data highlight SERT and NET as the predominant transporters involved in dopamine and norepinephrine membrane transport by MVM. On the other hand, paroxetine and cortisol displayed weak albeit significant inhibitory action on 3H-dopamine (Fig. 4b) and 3H-norepinephrine (Fig. 4d) uptake by the BM vesicles. Additionally, BM uptake of 3H-dopamine was affected by decynium-22. Collectively, these results suggest that OCT3 mediates the transport of 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine across the BM.

Figure 4.

Differential inhibitor sensitivity of 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine transport systems in human placental membranes. One-minute uptake of 3H-dopamine (a, b) and 3H -norepinephrine (c, d) was evaluated in the presence of 100 µM paroxetine (PAR), 100 µM venlafaxine (VEN), 20 nM nisoxetine (NIS), 50 nM GBR 12935 (GBR), 100 µM cortisol (CORT), and 10 µM decynium-22 (D22). Results are presented as percent uptake relative to the uptake in the absence of inhibitors (CTRL). Data are shown as median with interquartile range, n ≥ 4. Statistical analysis was evaluated using Kruskal–Wallis test: *(p ≤ 0.05), **(p ≤ 0.01), ***(p ≤ 0.001).

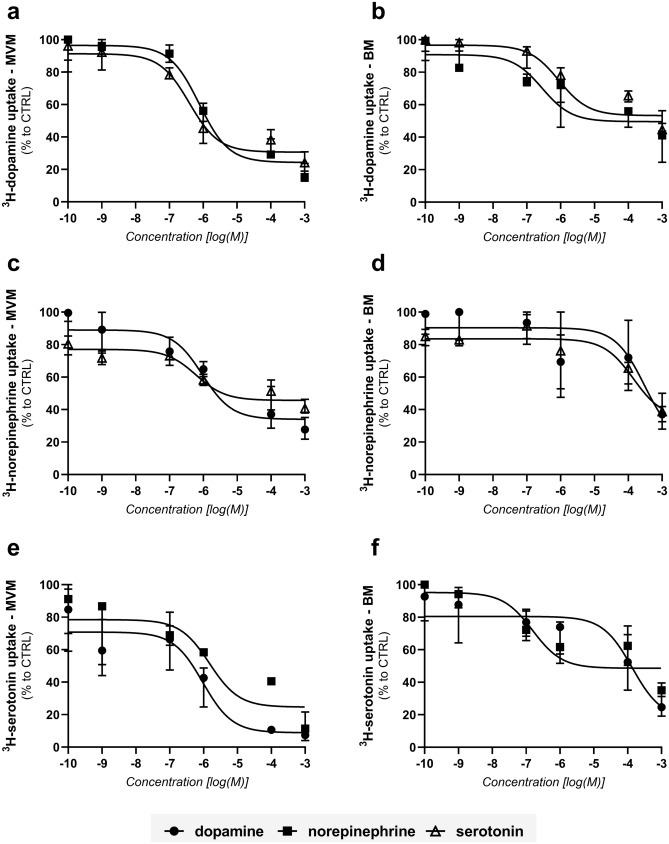

Characterization of the dynamic interactions of monoamines with placental transport systems

To investigate the interactions of monoamines on placental monoamine transporters, the effect of unlabelled monoamines on 3H-dopamine, 3H-norepinephrine, and 3H-serotonin uptake was investigated (Fig. 5a–f). These experiments suggest that the individual monoamine transport across placental MVM and BM does not occur via a single transporter, and a significant interaction between the three monoamines is observed on both membranes. 3H-dopamine (Fig. 5a) and 3H-norepinephrine (Fig. 5c) uptake by MVM was most potently inhibited by serotonin, whereas dopamine was the most potent inhibitor of 3H-serotonin (Fig. 5e) uptake by this membrane. In the BM vesicles, norepinephrine was the most potent monoamine to affect 3H-dopamine (Fig. 5b) and 3H-serotonin uptake (Fig. 5f). The half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) values are shown in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Effect of unlabelled dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin on monoamine transport systems in MVM and BM. Initial uptake rates (CTRL) were determined in vesicles incubated with 112 nM 3H-dopamine (a, b), 332 nM 3H-norepinephrine (c, d), and 100 nM 3H-serotonin (e, f) at room temperature for 1 min. Concentration-dependent analyses of unlabelled monoamines were evaluated at a range of 0.0001–1000 µM. Curve fitting by nonlinear regression was implemented in GraphPad Prism 8.1. Results are presented as percent uptake relative to CTRL. Data are shown as median with interquartile range, n = 4.

Table 2.

IC50 values (nM) for inhibition of 112 nM 3H-dopamine, 332 nM 3H-norepinephrine, and 100 nM 3H-serotonin uptake by MVM and BM in the presence of increasing concentrations of unlabelled monoamines.

| IC50 (nM) | MVM | BM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | Norepinephrine | Serotonin | Dopamine | Norepinephrine | Serotonin | |

| 3H-dopamine | – | 766 | 389 | – | 283 | 885 |

| 3H-norepinephrine | 939 | – | 602 | 3056 | – | 1422 |

| 3H-serotonin | 948 | 1491 | – | 1357 | 154 | – |

Discussion

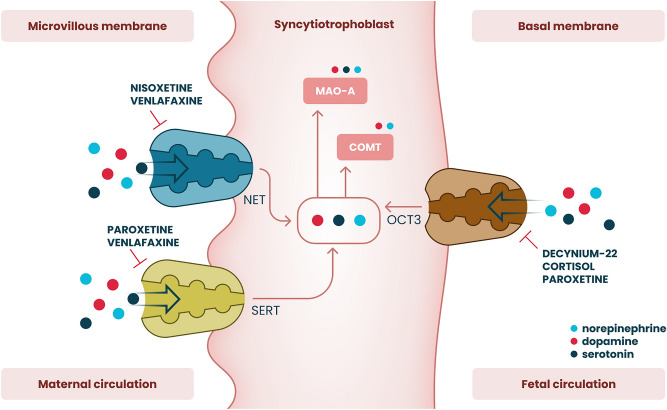

This study characterizes the transport mechanisms involved in dopamine and norepinephrine transfer across the apical and basal membranes of the human placenta (Fig. 6). Uptake by syncytiotrophoblast represents one of the main mechanisms of monoamine handling in the fetoplacental unit, and intrauterine catecholamine clearance is primarily mediated via transporter-dependent mechanisms43. Our findings expand on the pioneering work by Ganapathy et al., who were the first to identify the functional expression of monoamine transporters in the placenta44. The importance of SERT and NET for maternal-placental handling of dopamine and norepinephrine has been clearly established. However, despite increasing fetal monoamine production towards term15, limited attempts have been made to elucidate dopamine and norepinephrine transport across the fetal-facing basal membrane. Using an established ex vivo model of human placenta membrane vesicles, we demonstrate a novel physiological mechanism of dopamine and norepinephrine transport across the fetal-facing membrane into the placenta by OCT3.

Figure 6.

Summary of monoamine transport mechanisms in the apical and basal membranes of the human placental syncytiotrophoblast. Active uptake of dopamine and norepinephrine by the microvillous membrane is mediated via the high-affinity and low-capacity serotonin (SERT/SLC6A4) and norepinephrine (NET/SLC6A2) transporters. On the other hand, the organic cation transporter 3 (OCT3/SLC22A3) contributes to the placental monoamine clearance system by effectively mediating dopamine and norepinephrine uptake from the fetal circulation across the basal membrane.

Increasing evidence supports the placenta as a dopaminergic and adrenergic organ1. Although polar molecules, dopamine and norepinephrine were reported to cross the placental barrier from the maternal to the fetal circulation45,46. Moreover, increased fetal monoamine secretion during pregnancy results in elevated cord blood levels15. This intrauterine neuroendocrine milieu requires a finely tuned clearance mechanism to control monoamine levels in the fetoplacental unit. The current state of knowledge has primarily focused on the MVM, where functional expression of neuronal monoamine transporters (SERT and NET) is recognized as critical to intrauterine monoamine homeostasis26,27. Our findings show that these transporters share a similar transcriptional profile in the human placenta. In agreement with previous studies29, we demonstrate that NET mediates norepinephrine uptake by MVM in a time-, concentration- and Na+-dependent manner. Nonetheless, inhibition of norepinephrine transport in the presence of paroxetine (a selective SERT inhibitor) indicates the potential involvement of SERT in total norepinephrine uptake by MVM, although with significantly lower affinity.

In contrast, DAT expression in the human placenta is negligible and, based on the functional studies, does not contribute to monoamine uptake. This was previously suggested by Ramamoorthy et al., who attributed dopamine transport across placental MVM to NET30. Interestingly, we observed that dopamine uptake by MVM vesicles reveals an overshoot phenomenon over time, which largely mirrors that of serotonin, previously reported by our team31. On the contrary, norepinephrine uptake does not exhibit such a phenomenon, thus, suggesting SERT as the key transporter responsible for dopamine uptake by MVM. However, the sensitivity of the uptake to selective SERT (paroxetine) and NET (nisoxetine) inhibitors suggests an overlapping substrate specificity whereby both SERT and NET contribute to placental uptake of dopamine across the maternal-facing membrane. Indeed, accumulating evidence reveals that the SLC6A members share structural and mechanistic properties47,48. Consequently, dopamine has already been described as an alternative substrate of SERT and NET in neuronal tissue, albeit with a mechanistically distinct mode of substrate translocation49,50.

Importantly, our findings reveal a concentration-dependent placental uptake of dopamine and norepinephrine across the fetal-facing BM. Isotope displacement kinetics revealed different profiles between MVM and BM, indicating the involvement of a high-capacity transporter in BM. Moreover, intracellular potassium concentrations did not affect dopamine and norepinephrine uptake by BM vesicles, thus excluding the involvement of neuronal monoamine transporters in the fetus-facing membrane. We have recently shown that the low-affinity but high-capacity OCT3 mediates placental serotonin uptake from the fetal circulation31. Since OCT3 recognizes dopamine and norepinephrine as substrates33, we speculated that this transporter might also mediate the uptake of these two monoamines. Using several OCT3 inhibitors33,39, we confirm that this transporter is involved in the placental uptake of fetal dopamine and norepinephrine. Nonetheless, we identified a non-saturable fraction in the transport kinetics across BM. Although not widely acknowledged in the literature, several studies indicate that dopamine and norepinephrine may cross biological barriers also by passive diffusion23,24. Such a mechanism was also previously speculated in the placenta32, particularly in the BM, where water permeability through a lipid diffusive mechanism is significantly higher than in MVM51.

Fetal-to-maternal transfer of norepinephrine was first described by Sodha et al. using a human placenta perfusion system. The authors demonstrated that up to 50% of extracted fetal norepinephrine is metabolized within the trophoblast via COMT and MAO-A and released on the maternal side in the form of inactive metabolites32. Later, this was also reported in the ovine model, highlighting the role of the placenta in fetal norepinephrine clearance52. Similarly, we have shown that via a synchronized activity of transporters (SERT and OCT3) and metabolizing enzyme (MAO-A), the placenta contributes significantly to serotonin clearance from the fetal circulation31. Thus, we propose that the human placenta plays a neutralizing role in preventing elevated monoamine levels in the fetoplacental unit under physiological conditions.

Monoamine transporter promiscuity in the placenta was previously suggested in the MVM44; here, we describe a similar behavior also in the BM. It is thus logical to assume potential competition of monoamines for their transporters on both the maternal and fetal sides of the placenta. However, we report that the calculated IC50 values are notably higher than the physiological plasma concentrations of these monoamines in healthy pregnant women53–55, suggesting that mutual interactions and competition for uptake systems do not occur under physiological conditions. Nonetheless, this phenomenon may be detrimental in placental pathologies such as preeclampsia, associated with altered monoamine transporter expression27 and elevated plasma monoamine concentrations54–56. Moreover, inhibition of monoamine transporters by illicit drugs (e.g., cocaine) and pharmaceuticals (e.g., antidepressants) used during pregnancy, or endogenous molecules (e.g., cortisol), could compromise monoamine levels in the fetoplacental unit29,36, contributing to the adverse effect on fetal development and programming.

The strength of this study is using simultaneously isolated MVM and BM from the same placenta, thus minimizing the influence of clinical and genetic heterogeneity when comparing the transporter characteristics in each membrane. Nonetheless, while isolated human placental membranes provide an ideal model to investigate syncytial transport aspects (including ion composition, transport kinetics, and effect of inhibitors), this is done in the absence of intracellular constituents and regulatory factors57. Thus, an intact cell system is required to identify the contribution of specific transporter(s) on monoamine transplacental flux in vivo. Moreover, cellular metabolism should be considered when estimating the total clearance capacity.

In conclusion, the placenta provides an efficient clearance system for dopamine and norepinephrine from both maternal and fetal circulations. Although not investigated in this study, we speculate that this transport function plays a multifaceted role in placental physiology in conjunction with intracellular metabolism. Ultimately, placental monoamine transport and metabolism may constitute essential mechanisms implicated in fetal programming of adulthood disorders.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank prof. Marian Kacerovsky, Ph.D. and Martina Hudeckova (Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty Hospital in Hradec Kralove), for arranging placenta sample collection. Additionally, we would like to thank Jarda Simek for the graphical presentation of Fig. 6.

Author contributions

Study concept and design—H.H., F.S., C.A.; Data acquisition—H.H., R.K., V.V., H.T., C.A.; Data analysis—H.H., R.K.; Data interpretation—H.H., R.K., C.A., F.S.; Manuscript preparation—H.H., R.K., C.A., F.S. All authors have approved the submitted version and are personally accountable for their contributions to the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (Grant No. GACR 20-13017S) and the Grant Agency of Charles University (SVV 260414). The research of H.H. and V.V. was further supported by Grant Schemes at CU (Reg. No. CZ.02.2.69/0.0/0.0/19_073/0016935).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-15790-7.

References

- 1.Rosenfeld CS. The placenta-brain-axis. J. Neurosci. Res. 2021;99:271–283. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levitt P, Harvey JA, Friedman E, Simansky K, Murphy EH. New evidence for neurotransmitter influences on brain development. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:269–274. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarthy D, Lueras P, Bhide PG. Elevated dopamine levels during gestation produce region-specific decreases in neurogenesis and subtle deficits in neuronal numbers. Brain Res. 2007;1182:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Todd RD. Neural development is regulated by classical neurotransmitters: Dopamine D2 receptor stimulation enhances neurite outgrowth. Biol. Psychiatry. 1992;31:794–807. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90311-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohtani N, Goto T, Waeber C, Bhide PG. Dopamine modulates cell cycle in the lateral ganglionic eminence. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:2840–2850. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.23-07-02840.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popolo M, McCarthy DM, Bhide PG. Influence of dopamine on precursor cell proliferation and differentiation in the embryonic mouse telencephalon. Dev. Neurosci. 2004;26:229–244. doi: 10.1159/000082140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saboory E, Ghasemi M, Mehranfard N. Norepinephrine, neurodevelopment and behavior. Neurochem. Int. 2020;135:104706. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padbury JF. 5—Functional maturation of the adrenal medulla and peripheral sympathetic nervous system. Baillieres Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1989;3:689–705. doi: 10.1016/S0950-351X(89)80049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas SA, Matsumoto AM, Palmiter RD. Noradrenaline is essential for mouse fetal development. Nature. 1995;374:643–646. doi: 10.1038/374643a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macaron C, Famuyiwa O, Singh SP. In vitro effect of dopamine and pimozide on human chorionic somatomammotropin (hCS) secretion*. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1978;47:168–170. doi: 10.1210/jcem-47-1-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petit A, et al. Presence of D2-dopamine receptors in human term placenta. J. Recept. Res. 1990;10:205–215. doi: 10.3109/10799899009064666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Previc FH. Prenatal influences on brain dopamine and their relevance to the rising incidence of autism. Med. Hypotheses. 2007;68:46–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson PD, Schutz CK, Macciardi F, White BN, Holden JJ. Genetically determined low maternal serum dopamine beta-hydroxylase levels and the etiology of autism spectrum disorders. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001;100:30–36. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holzman C, et al. Maternal catecholamine levels in midpregnancy and risk of preterm delivery. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009;170:1014–1024. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones CM, Greiss FC. The effect of labor on maternal and fetal circulating catecholamines. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1982;144:149–153. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90616-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Möller IR, et al. Conformational dynamics of the human serotonin transporter during substrate and drug binding. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1687. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09675-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mandela P, Ordway GA. The norepinephrine transporter and its regulation. J. Neurochem. 2006;97:310–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borre L, Andreassen TF, Shi L, Weinstein H, Gether U. The second sodium site in the dopamine transporter controls cation permeation and is regulated by chloride. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:25764–25773. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.574269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stamford JA, Kruk ZL, Millar J. Striatal dopamine terminals release serotonin after 5-HTP pretreatment: In vivo voltammetric data. Brain Res. 1990;515:173–180. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90593-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vizi ES, Zsilla G, Caron MG, Kiss JP. Uptake and release of norepinephrine by serotonergic terminals in norepinephrine transporter knock-out mice: Implications for the action of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2004;24:7888–7894. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1506-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gasser PJ. Roles for the uptake(2) transporter OCT3 in regulation of dopaminergic neurotransmission and behavior. Neurochem. Int. 2019;123:46–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miura Y, et al. Characterization of murine polyspecific monoamine transporters. FEBS Open Bio. 2017;7:237–248. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ingebretsen OC, Flatmark T. Active and passive transport of dopamine in chromaffin granule ghosts isolated from bovine adrenal medulla. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:3833–3839. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)50662-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scholze P, Sitte HH, Singer EA. Substantial loss of substrate by diffusion during uptake in HEK-293 cells expressing neurotransmitter transporters. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;309:173–176. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Staud F, Karahoda R. Trophoblast: The central unit of fetal growth, protection and programming. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018;105:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasad PD, et al. Functional expression of the plasma membrane serotonin transporter but not the vesicular monoamine transporter in human placental trophoblasts and choriocarcinoma cells. Placenta. 1996;17:201–207. doi: 10.1016/S0143-4004(96)90039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bottalico B, et al. Norepinephrine transporter (NET), serotonin transporter (SERT), vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2) and organic cation transporters (OCT1, 2 and EMT) in human placenta from pre-eclamptic and normotensive pregnancies. Placenta. 2004;25:518–529. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shearman LP, Meyer JS. Norepinephrine transporters in rat placenta labeled with [3H]nisoxetine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;284:736–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramamoorthy S, et al. Expression of a cocaine-sensitive norepinephrine transporter in the human placental syncytiotrophoblast. Biochemistry. 1993;32:1346–1353. doi: 10.1021/bi00056a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramamoorthy S, Leibach FH, Mahesh VB, Ganapathy V. Active transport of dopamine in human placental brush-border membrane vesicles. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;262:C1189–C1196. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.5.C1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karahoda R, et al. Serotonin homeostasis in the materno-foetal interface at term: Role of transporters (SERT/SLC6A4 and OCT3/SLC22A3) and monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) in uptake and degradation of serotonin by human and rat term placenta. Acta Physiol. 2020;229:e13478. doi: 10.1111/apha.13478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sodha RJ, Proegler M, Schneider H. Transfer and metabolism of norepinephrine studied from maternal-to-fetal and fetal-to-maternal sides in the in vitro perfused human placental lobe. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1984;148:474–481. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90729-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koepsell H. Organic cation transporters in health and disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 2020;72:253–319. doi: 10.1124/pr.118.015578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glazier JD, Jones CJ, Sibley CP. Purification and Na+ uptake by human placental microvillus membrane vesicles prepared by three different methods. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1988;945:127–134. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(88)90475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farrugia W, de Gooyer T, Rice GE, Moseley JM, Wlodek ME. Parathyroid hormone(1–34) and parathyroid hormone-related protein(1–34) stimulate calcium release from human syncytiotrophoblast basal membranes via a common receptor. J. Endocrinol. 2000;166:689–695. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1660689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horackova H, et al. Effect of selected antidepressants on placental homeostasis of serotonin: Maternal and fetal perspectives. Pharmaceutics. 2021 doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13081306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou J. Norepinephrine transporter inhibitors and their therapeutic potential. Drugs Future. 2004;29:1235–1244. doi: 10.1358/dof.2004.029.12.855246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berger P, Elsworth JD, Arroyo J, Roth RH. Interaction of [3H]GBR 12935 and GBR 12909 with the dopamine uptake complex in nucleus accumbens. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990;177:91–94. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90554-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horton RE, et al. Decynium-22 enhances SSRI-induced antidepressant-like effects in mice: Uncovering novel targets to treat depression. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2013;33:10534–10543. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5687-11.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haka MS, Kilbourn MR. Synthesis and regional mouse brain distribution of [11C]nisoxetine, a norepinephrine uptake inhibitor. Int. J. Rad. Appl. Instrum. B. 1989;16:771–774. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(89)90160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rothman RB, et al. Identification of a GBR12935 homolog, LR1111, which is over 4,000-fold selective for the dopamine transporter, relative to serotonin and norepinephrine transporters. Synapse. 1993;14:34–39. doi: 10.1002/syn.890140106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhat, S. et al. Handling of intracellular K+ determines voltage dependence of plasmalemmal monoamine transporter function. bioRxiv 2021.2003.2011.434931. 10.1101/2021.03.11.434931 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Bzoskie L, Blount L, Kashiwai K, Humme J, Padbury JF. The contribution of transporter-dependent uptake to fetal catecholamine clearance. Biol. Neonate. 1997;71:102–110. doi: 10.1159/000244403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ganapathy V, Ramamoorthy S, Leibach FH. Transport and metabolism of monoamines in the human placenta: A review. Placenta. 1993;14:35–51. doi: 10.1016/S0143-4004(05)80281-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe T, Matsuhashi K, Takayama S. Placental and blood–brain barrier transfer following prenatal and postnatal exposures to neuroactive drugs: Relationship with partition coefficient and behavioral teratogenesis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1990;105:66–77. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(90)90359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morgan CD, Sandler M, Panigel M. Placental transfer of catecholamines in vitro and in vivo. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1972;112:1068–1075. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(72)90182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coleman JA, Green EM, Gouaux E. X-ray structures and mechanism of the human serotonin transporter. Nature. 2016;532:334–339. doi: 10.1038/nature17629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pidathala S, Mallela AK, Joseph D, Penmatsa A. Structural basis of norepinephrine recognition and transport inhibition in neurotransmitter transporters. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:2199. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22385-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morón JA, Brockington A, Wise RA, Rocha BA, Hope BT. Dopamine uptake through the norepinephrine transporter in brain regions with low levels of the dopamine transporter: Evidence from knock-out mouse lines. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:389–395. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.22-02-00389.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larsen MB, et al. Dopamine transport by the serotonin transporter: A mechanistically distinct mode of substrate translocation. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:6605–6615. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0576-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jansson T, Illsley NP. Osmotic water permeabilities of human placental microvillous and basal membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 1993;132:147–155. doi: 10.1007/bf00239004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bzoskie L, et al. Placental norepinephrine clearance: In vivo measurement and physiological role. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;269:E145–E149. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.269.1.E145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cengiz H, et al. Plasma serotonin levels are elevated in pregnant women with hyperemesis gravidarum. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015;291:1271–1276. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3572-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carrasco G, et al. Plasma and platelet concentration and platelet uptake of serotonin in normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancies. Life Sci. 1998;62:1323–1332. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khatun S, et al. Increased concentrations of plasma epinephrine and norepinephrine in patients with eclampsia. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1996;69:61–67. doi: 10.1016/0301-2115(95)02511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Middelkoop CM, Dekker GA, Kraayenbrink AA, Popp-Snijders C. Platelet-poor plasma serotonin in normal and preeclamptic pregnancy. Clin. Chem. 1993;39:1675–1678. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/39.8.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greenwood SL, Sibley CP. In vitro methods for studying human placental amino acid transport placental villous fragments. Methods Mol. Med. 2006;122:253–264. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-989-3:253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).