Abstract

Mentorship is critical to develop research scholars. Current literature provides mentorship guidance for biomedical research; however, mentorship for educational research is scarce. We explored literature to offer evidence-based guidance for medical education research mentors. A librarian searched peer-reviewed literature from 2001 to 2021 to identify guidelines for research mentors. Thirty-five articles were included in this narrative review. Our results identified attributes of mentors, overlapping roles, and barriers and benefits of mentoring. The structures and processes related to mentoring are reviewed and applicability to medical education research mentorship is summarized.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40670-022-01565-2.

Keywords: Medical student, Mentor, Educational research, Educational scholarship

Introduction

Mentors in research play critical roles in shaping mentee career paths, research productivity, and career satisfaction [1–5], and mentors’ characteristics have been catalogued. Recognizing concern for the leaky trainee pipeline and declines in the percentage of physicians engaged in biomedical research, academic health systems initiated dedicated efforts to recruit faculty and learners to physician scientist roles [1, 6–12]. Medical schools now offer promotion and tenure pathways for educators [13]; however, there continues to be the need for better understanding of medical educational scholarship in order to mentor effectively [14].

Institutions have robust biomedical research mentoring programs and numerous articles were identified addressing biomedical research mentoring programs [15–19]. Many of these programs are formal courses or seminars designed to establish expectations for students seeking mentorship in biomedical research [17, 18, 20, 21]. One program reported hiring dedicated staff to function as mentors and advisors to trainees [16]. Published works also emphasized characteristics of effective mentorship, including setting clear research goals, defining expectations, and maintaining clear communication [22], particularly in more formal mentoring programs [23–25]. All studies primarily focused on the learners who were to be mentored, with only limited direct guidance provided for faculty mentors.

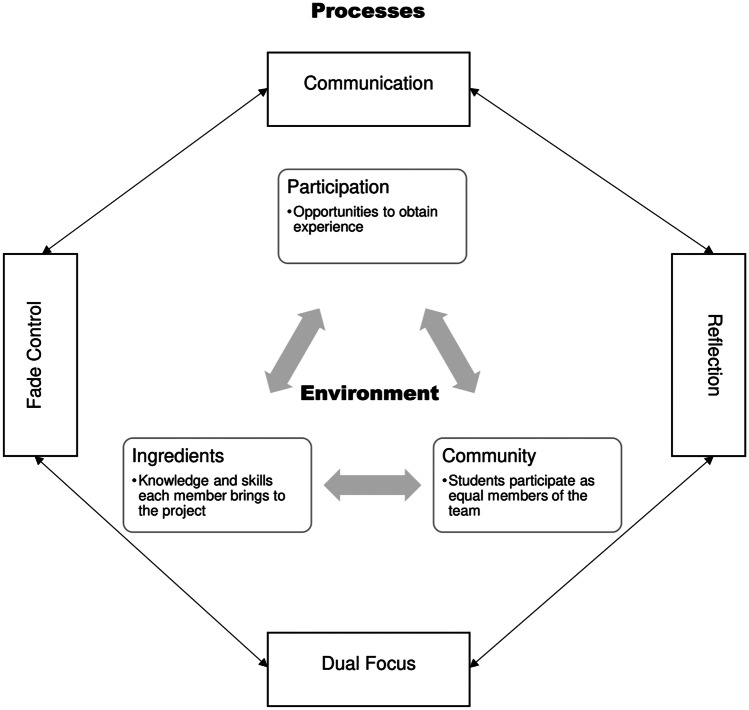

There is limited literature to describe faculty development in educational research mentorship. One model that could be applied to medical education research mentorship is the process-environment model (Fig. 1) [26]. This model describes the interaction of processes (communication, reflection, dual focus, fade control) with environmental factors (participation, community, ingredients) for successful mentoring relationships. Regarding the processes, there is the need for communication in medical education research given the longitudinal nature of many educational research projects. Reflection may be accomplished through regular discussions via in-person meetings or email communications. The reflection process allows the mentor and mentee to review progress as well as discuss potential shortcomings in their own research skills. This leads into dual focus, which addresses efforts to study the primary research question or innovation objective coupled with the mentee’s learning throughout the research process. Lastly, fade control allows mentees more autonomy on research-related activities as self-efficacy (confidence) grows.

Fig. 1.

Process-environment mentorship model (adapted from Hickey et al. [26]). Process elements include communication, reflection, dual focus, and fade control. Environmental elements of this model involve participation (opportunities), community (active engagement), and ingredients (skills and knowledge)

Regarding the environmental elements of this model [26], participation ensures the medical education research environment provides a range of opportunities. In other words, the project should be flexible to ensure mentees can contribute to the highest degree possible balancing the demands of their academic commitments. Community suggests students contribute as equal members of the research team. Given many clinician educators are unfamiliar with medical education research, this sense of community is also important and is closely tied with ingredients. The element of ingredients reflects the knowledge and skills both mentor and mentee bring to the project, and together community and ingredients promote a synergistic relationship to strengthen the work.

The process-environment mentorship model [26] works well in the context of medical education research given the nuances of educational research. Unlike clinical trials or laboratory research, educational research has neither one best way to plan and conduct the research nor a single truth to be discovered [27]. Because of these uncertainties, processes of communication and reflection are key elements along with ingredients to address the research question [26].

Today’s learners are interested in not only what, but how, they engage with new subject matter. Passionate about emerging topics, medical students lead efforts initiating innovative approaches to content delivery [28]. Their enthusiasm highlights both opportunity and need for greater expertise in methodologies of medical education research; however, the authors found very little available to guide clinician educators who mentor medical students in educational scholarship. Challenges posed by medical students’ varied exposure to research in college, faculty and student limited or lack of familiarity with educational research methodologies, and time constraints on busy clinician educators, are but a few of the obstacles the authors have experienced. This manuscript identifies unique features in medical education research mentorship through the process-environment mentorship model [26].

Materials and Methods

We conducted a narrative review of the literature on medical education research mentorship. Narrative reviews allow investigators to synthesize existing literature to address questions or explore new directions. Given the limited publications related specifically to medical education research mentoring, we chose to explore the data using narrative review [29, 30] as the best approach for our objective.

Search Strategy

In June 2021, our librarian (SW) searched PubMed for English-language literature published in peer-reviewed journals from 2001 to 2021. Two of the authors (GBD, SJ) conceptualized this project and crafted a list of search terms. With the help of the librarian, the search was refined. The search strategy used the following terms: (faculty[ti] OR faculty, medical[majr] OR mentoring[majr] OR attending*[ti] OR mentor*[ti] OR collabor*[ti] OR physician*[ti] OR coordinat*[ti]) AND (“medical student*”[ti] OR students, medical[majr] OR “medical education”[ti] OR “medical school*”[ti] OR schools, medical[majr] OR education, medical, undergraduate[majr] OR summer[ti] OR elective[ti]) AND (research*[ti] OR research[majr]).

Study Selection Criteria and Process

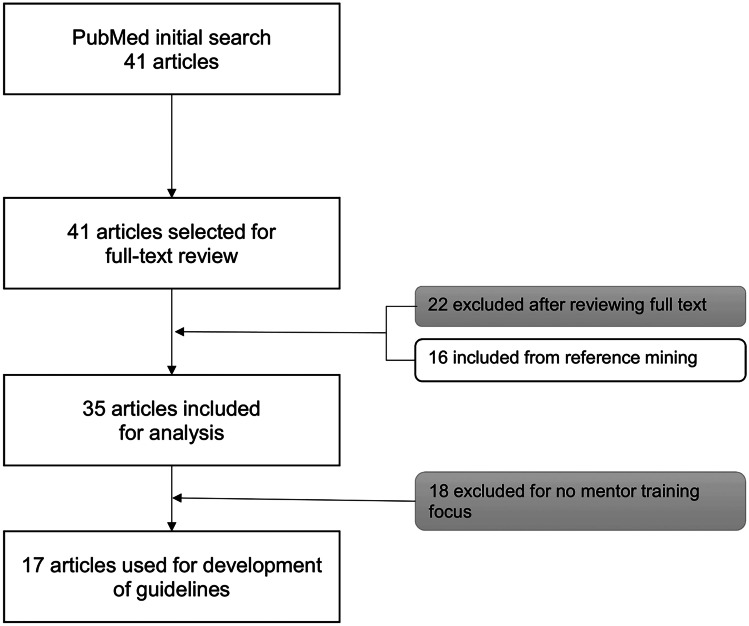

We included studies in this review if (1) the study was available in English; and (2) the study involved recommendations for research mentors. The librarian’s electronic database search yielded 41 studies. While articles were being reviewed, references were mined to incorporate into the review. From the reference mining, 16 additional articles were identified, which included four review articles. Given the small number of articles, full text reviews were conducted on every article. Twenty-two were eliminated from inclusion because they contained no content about mentors (Fig. 2). An additional 18 were removed after careful review because they contained no guidance for mentors.

Fig. 2.

Search strategy and article selection process. The results of the literature search conducted by the librarian along with additional reference mining resulted in 17 articles specifically related to guidelines for educational research mentors

Data Extraction

We extracted data from 17 studies to develop guidance for faculty members seeking to mentor medical education research. This approach allowed us to integrate evidence from the literature with our experiences in medical education research mentorship.

Results and Discussion

From our review of the literature and application of the process-environment mentorship model [26], a summary of articles and key findings is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Findings from articles categorized by recommendation and theoretical component

| Author | Findings | Guideline | Theory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allen et al. [31] | Meta-analysis addressing mentor career satisfaction, expectations for advancement, career commitment, and retention | Benefits of mentoring |

Participation Communication |

| Ben-David et al. [1] | Describes rigorous mentored research training program funding medical students’ summer research in oncology (development, implementation, evaluation, and major outcomes of program) | Setting expectations |

Participation Community |

| Bower et al. [32] | Presents a theoretical model to effectively acclimate faculty into academic medicine, emphasizing the need for quality mentorship | Role of mentor |

Ingredients Dual focus |

| Coe et al. [33] | Describes a model of possible pathways to several leadership positions within academic family medicine and intentional use of multidimensional mentoring team as critically important for successfully navigating path to leadership | Overlapping roles |

Participation Community Reflection |

| Corcoran et al. [15] | Describes 8-week Summer Clinical Otolaryngology and Obstetrics/Gynecology Research (SCORE) Program for second-year medical students | Benefits of mentoring |

Community Fade control |

| Koehler et al. [34] | Describes an approach with undergraduate nursing students who work with faculty to develop a research proposal, identifying specific questions and exploring relevant literature |

Identifying knowledge gaps Benefits of mentoring |

Reflection Participation |

| McSweeney et al. [35] | Qualitative interviews with 20 participants from the NIH-funded Arkansas INBRE SSMRP to elicit student perspectives on SSMRP participation | Benefits of mentoring |

Community Fade control |

| Morrison-Beedy et al. [22] | Describes reciprocal benefits of research mentoring for students, junior faculty, and senior faculty researchers as well as for colleges of nursing and nursing science | Benefits of mentoring |

Community Fade control |

| O’Brien and Hathaway [36] | Survey study 15 student and 5 faculty perceptions of a research internship embedded in an existing evidence-based practice course | Characteristics of mentor/mentee relationship |

Community Participation Fade control |

| Ramani et al. [37] | 12 tips workshops reviewed skills of mentoring and strategies for designing effective mentoring programs. Participants engaged in brainstorming and interactive discussions and developed implementation plan for a mentoring program for medical students and faculty | Role of mentor |

Ingredients Dual focus |

| Characteristics of mentor/mentee relationship | Dual focus | ||

| Sambunjak et al. [12] | Systematic review of qualitative literature to explore and summarize the development, perceptions, and experiences of the mentoring relationship in academic medicine | Barriers to participation |

Ingredients Community Communication |

| Sng et al. [38] | Thematic analysis of 49 articles reveals five semantic themes of initiation process, developmental process, evaluation process, sustaining mentoring relationship, and obstacles to effective mentoring | Characteristics of mentor/mentee relationship |

Communication Participation Dual focus Fade control |

| Som et al. [9] | Descriptive toolkit – resident-led radiology research interest group for undergraduate and medical students to foster career development, build practical skills, and create opportunities for multidisciplinary collaborative research and mentorship | Setting expectations |

Participation Community |

| Ssemata et al. [39] | Thematic analysis identifying key factors defined by mentees and mentors as necessary for a successful mentorship program | Barriers to mentoring |

Ingredients Participation Community |

| Straus et al. [40] | Qualitative interview studied mentor–mentee relationship to characterize among people who have obtained early career support from a government funding agency | Characteristics of mentor/mentee relationship |

Communication Dual focus |

| Straus et al. [41] | Qualitative interview reported themes of mentor–mentee relationship with a focus on characteristics of effective mentors and mentees and understanding the factors influencing successful and failed mentoring relationships |

Characteristics of mentor/mentee relationship Barriers to mentoring |

Communication Reflection Dual focus Ingredients Participation Community |

| Ward et al. [10] | Describes database focused on common and under-researched pathology resulting in high volume of novel research output. Additional program benefits include increased scholarly and mentorship ability in engaged residents and medical students | Setting expectations |

Participation Communication |

Role of Mentor

A mentor is often an advisor, counselor, teacher, and provides constructive feedback to the mentee [37]. Although it may be difficult, mentorship must offer both support and challenge to the mentee to ensure professional growth [32]. Within medical education research, a mentor employs dual focus providing mentorship while sharing foundational knowledge in principles of medical education research such as methodologies (quantitative vs. qualitative), theoretical frameworks, collection and analysis of data, and scholarly dissemination.

Characteristics of Mentor/Mentee Relationship

A thematic review by Sng et al. [38] assessed the characteristics of mentoring relationships between senior physicians and junior physicians/medical students in formal mentoring programs. These characteristics included an initiation process followed by deliberate cultivation of the mentoring relationship. The initiation process focuses on identifying overlapping qualities of mentors and mentees and the process of matching the dyads. Medical education research mentoring is often unstructured and relies on regular communication to develop and maintain relationships [26, 36].

The characteristics identified by Sng et al. [38] rely upon equal investment from the mentor and mentee to ensure a successful relationship. Reciprocity and mutual respect, along with honest communication, are paramount in effective mentorship [40, 41]. Not unlike quality improvement in the clinical setting, successful mentoring relationships require constant attention, evaluation of relationship, and strategies for continued improvement.

Overlapping Roles

It is important to note that mentors often assume additional roles in the mentoring relationship, particularly those of sponsor and coach. Although all dovetail in the goal of helping the mentee succeed, sponsorship and coaching serve additional roles in a multidimensional mentoring team [33]. Coaches typically focus on improving the quality of the mentees’ performance and sponsors actively share the mentees’ accomplishments with others and promote mentees in additional opportunity endeavors [33, 41]. These roles are examples of environmental elements of participation and community [26].

An additional overlapping role medical education research mentors may encounter is the dual roles as both research mentor and course director or instructor for student(s). This may not happen very often in biomedical research. In situations such as this, it is incumbent upon the mentor to strive to not show any instructional bias toward the mentee. Reflection on actions assists mentors in assuring their duality of roles and relationships with the mentee do not alter the research and clinical goals [26].

Identifying Knowledge Gaps of Mentees and Mentors

Clinician educators may be skilled at teaching medical students, but often lack needed fundamentals in educational scholarship. Educational scholarship requires a systematic inquiry of educational interventions guided by theoretical assumptions that can be disseminated to allow peer review of the work’s merit [42]. Although research methodologies of basic sciences and translational science overlap with educational scholarship, there are methodologies and data analysis techniques that are unique to educational research [27]. Mentors must recognize their own knowledge gaps and also assist students in identifying theirs [34]. This is not meant to imply mentors must become expert in these areas, but it is important for clinician educators to have working knowledge and to know the experts with whom they can partner to facilitate student and mentor success.

Setting Expectations

Successful medical student research programs vary, but all emphasize defined goals and structure [1, 9]. Recommended steps in a structured program include defined application submission and review, rigorous program with introductory onboarding, mid-program works in progress seminar, and final formal symposium, followed by qualitative and quantitative post program evaluation [1]. Successful longitudinal research experiences have detailed expectations with regularly scheduled meetings and institutional research infrastructure [9, 10]. Mentor training also emphasizes strategies for improving communication with mentees and promoting mentee professional development [1, 9]. In medical education research, data collection often occurs over a longer period of time; mentors should plan regular check-ins with mentees to foster the sense of participation and community [26].

Barriers to Mentoring

Mentors seek to enhance learners’ skills and thereby improve learners’ abilities to produce desired outcomes [39]. Mentoring, however, is susceptible to challenges. Broadly reported challenges are a lack of knowledge about institutional programs, lack of formal structure, and unclear roles and expectations of mentors and mentees [39, 41]. A multidisciplinary systematic review identified barriers as a. Personal, b. Relational, and c. Structural [43]. The list of challenges included lack of appropriate mentoring skills of the mentor; racial, ethnic, or gender differences that make finding common ground difficult; mentor taking credit for the work of the mentee; mentee surpassing a mentor in their area of expertise; lack of time; lack of mentor incentives or recognition; and lack of mentee access to faculty mentors [43]. Also identified in thematic analyses were poor communication, lack of commitment, personality differences, perceived (or real) competition, conflicts of interest, and the mentor’s lack of experience [41]. Of those identified, competition between mentors and mentees contributed more to a failed relationship [41].

Benefits of Mentoring

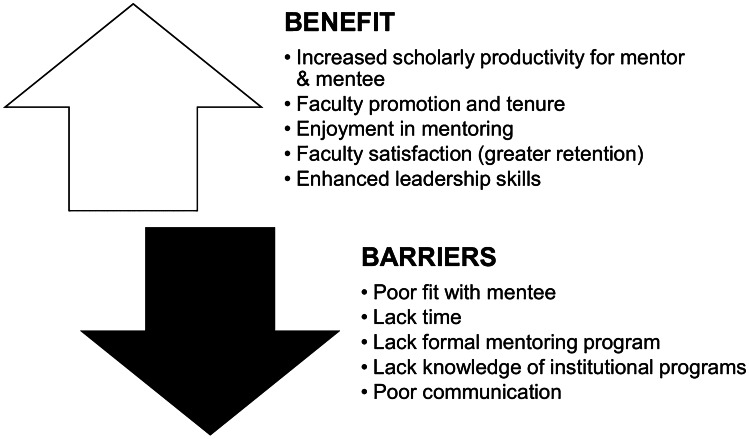

In medical education research, mentoring discovery (research inquiries) can result in mutual scholarly productivity for the mentor and mentee [15, 22, 35]. Scholarly productivity benefits the mentor with increased promotion, tenure, and retention rates [41] and benefits the mentee’s application to residency [22, 44]. Intangible benefits are also present – mentors gain guidance in navigating medical education research processes, mutual respect and collegiality, and career satisfaction [31]. Mentors also express enjoyment found in educating mentees in research [15, 34]. Figure 3 provides a summary of barriers and benefits to mentoring.

Fig. 3.

Benefits and barriers for medical education research mentors. Guided by the literature, this figure summarizes key benefits and potential barriers for faculty considering mentoring trainees in medical education research

Guidelines for Medical Education Research Mentors

Medical students may bring skills (or ingredients) [26] in basic research principles and/or formulating a scientific question, but very few have experience in medical education research question development. For medical education research, questions may not be as straightforward as biomedical research due to uncontrolled factors. Mentors should strive to assess the mentees’ needs and capabilities and facilitate goal-setting to ensure aligned expectations of the mentor and mentee [37, 38, 40]. The mentee should strive to be reflective, open to feedback, and show initiative to facilitate the mentoring relationship [41]; this in turn aligns with the dual focus and reflective processes described by Hickey et al. [26]. Lastly, mentors should have institutional and academic awareness to appraise mentees on possible pitfalls and challenging encounters [41].

Based on our narrative review as well as our collective experience mentoring medical students and residents in educational research, key guidelines to consider for faculty seeking to mentor trainees in educational research are included in Table 2. Brief tips for faculty are included.

Table 2.

Guidelines for educational scholarship

| Guideline | Description and tips |

|---|---|

| Welcoming attitude |

Being open to working with a trainee on a research project is the first step (participation and community). Even if you feel unprepared, being open to learning is part of the dual process TIP: Be aware of experts (from local and national networking) and resources to support students’ scholarly pursuits! |

| Overlapping Roles | |

| Planning |

Data collection for educational research can be short-term and sometimes take years. Creating a plan for the project will help ensure regular communication with mentees as well as progress to completion TIP: Set up reminders on your calendar for regular check-ins with your mentee TIP: Set reasonable deadlines based on the students’ schedule, taking into consideration examinations and holidays |

| Assess research needs |

Educational research involves different methodologies and may require special permissions for data use (e.g., Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act) TIP: The following topics with accompanying article citations offer foundational education you and your mentee can benefit from reading! TIP: These topics are also often times available as continuing education sessions professional organizations or the Medical Education Research Certificate program (https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/medical-education/meded-research-certificate-program) |

|

Foundational topics in medical education research • Crites GE, Gaines JK, Cottrell S, Kalishman S, Gusic M, Mavis B, Durning SJ. Medical education scholarship: an introductory guide: AMEE Guide No. 89. Med Teach. 2014; 36:657–674 • Kanter SL. Toward better descriptions of innovations. Acad Med. 2008; 83(8):703–704 • Chen W, Reeves TC. Twelve tips for conducting educational design research in medical education. Med Teach. 2020; 42(9):980–986 | |

|

Theory and conceptual models • Samuel A, Konopasky A, Schuwirth LWT, King SM, Durning SJ. Five principles for using education theory: strategies for advancing health professions research. Acad Med. 2020; 95:518–522 • Bordage G, Youdkowsky R. Conceptual frameworks to guide research and development (R&D) in health professions education. Acad Med. 2016; 91(12):e2 | |

|

Human subjects review • Egan-Lee E, Freitag S, Leblanc V, Baker L, Reeves S. Twelve tips for ethical approval for research in health professions education. Med Teach. 2011; 33:268–272 | |

|

Quantitative research • Windish DM, Diner-West M. A clinician-educator’s roadmap to choosing and interpreting statistical tests. J Gen Intern Med. 2006; 21:656–660 | |

|

Qualitative research • McGrath C, Palmgren PJ, Liljedahl M. Twelve tips for conducting qualitative research interviews. Med Teach. 2019; 41(9):1002–1006 • Kiger ME, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med Teach. 2020; 42(8):846–854 | |

|

Mixed methods research • Kajamaa A, Mattick K, de la Croix A. How to…do mixed-methods research. Clin Teach. 2020; 17:1–5 | |

|

Survey research • Artino Jr AR, Durning SJ, Sklar DP. Guidelines for reporting survey-based research submitted to academic medicine. Acad Med. 2018; 93(3):337–340 | |

|

Literature reviews • Siddaway AP, Wood AM, Hedges LV. How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu Rev Psychol. 2019; 70:747–770 • Ferrari R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med Writing. 2015: 24(4):230–235 | |

| Barriers |

Time and lack of mentoring incentives for educational research are real barriers TIP: Negotiate with your department for time, highlighting the benefits of mentoring identified in the article |

Not included is one key characteristic for medical education research mentors that addresses the competition barrier, which is faculty humility. Knowing that mentors may be learning as much about educational scholarship as the mentee, the mentor must be open to the idea that the mentee may have greater expertise. Recognizing this will permit the mentor to exercise fade control during the project as the mentee transitions to function in a more autonomous fashion.

Conclusions

As healthcare delivery continues to evolve, so too should medical education. To ensure continued innovation, a pathway of medical education researchers is imperative, complete with dedicated medical education mentors. The processes, educational scholarship resources, and guidelines outlined above provide a platform to support medical education research mentors. While the process requires time and resource investment, the benefits are multiple for both the mentors and mentees. It is also important to highlight that while there is overlap between biomedical research mentors and medical education research mentors, there remains a unique skillset among medical educators.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Data Availability

No data is associated with this submission.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ben-David K, Lin JJ, Ferrara LM. Tisch Cancer Institute Scholars Program: mentored cancer research training pipeline for medical students. J Cancer Educ. 2021;1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Horn L, Koehler E, Gilbert J, Johnson DH. Factors associated with the career choices of hematology and medical oncology fellows trained at academic institutions in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(29):3932–3938. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.8663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lev EL, Kolassa J, Bakken LL. Faculty mentors’ and students’ perceptions of students’ research self-efficacy. Nurse Educ Today. 2010;30(2):169. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorkness CA, Pfund C, Ofili EO, Okuyemi KS, Vishwanatha JK, on behalf of the NRMN team. Zavala ME, Pesavento T, Fernandez M, Tissera A, et al. A new approach to mentoring for research careers: the National Research Mentoring Network. BMC Proc. 2017;11(Suppl 12):22. doi: 10.1186/s12919-017-0083-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steiner JF, Curtis P, Lanphear BP, Vu KO, Main DS. Assessing the role of influential mentors in the research development of primary care fellows. Acad Med. 2004;79(9):865–872. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200409000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosik RO, Tran DT, Fan AP-C, Mandell GA, Tarng DC, Hsu HS, Chen YS, Su TP, Wang SJ, Chiu AW, et al. Physician scientist training in the United States: a survey of the current literature. Eval Health Prof. 2016;39(1):3–20. doi: 10.1177/0163278714527290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institutes of Health. Physician-scientist workforce working group report 2014. https://acd.od.nih.gov/documents/reports/PSW_Report_ACD_06042014.pdf. Accessed 22 Sept 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Robbins L, Bostrom M, Marx R, Roberts T, Sculco TP. Restructuring the orthopedic resident research curriculum to increase scholarly activity. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):646–651. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00303.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Som A, Lang M, Di Capua J, Chonde DB, Cochran RL. Resident-led medical student radiology research interest group: an engine for recruitment, research, and mentoring. Radiology. 2021;300(1):E290–E292. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021204518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward B, Schultz JJ, Halsey JN, Hoppe IC, Lee ES, Granick MS. Mentorship through research: a novel approach to increasing resident and medical student research competency through an institutional database. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(6):1331–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams CS, Iness AN, Baron RM, Ajijola OA, Hu PJ, Vyas JM, Baiocchi R, Adami AJ, Lever JM, Klein PS, et al. Training the physician-scientist: views from program directors and aspiring young investigators. JCI Insight. 2018;3(23):e125651. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.125651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):72–78. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1165-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman LA, Lufler RS, Brown KM, DeVeau K, DeVaul N, Fatica LM, Mussell J, Byram JN, Dunham SM, Wilson AB. A review of U.S. Medical schools’ promotion standards for educational excellence. Teach Learn Med. 2020;32(2):184–193. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2019.1686983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook DA. Getting started in medical education scholarship. Keio J Med. 2010;59(3):96–103. doi: 10.2302/kjm.59.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corcoran K, Weintraub MR, Silvestre I, Varghese R, Liang J, Zaritsky E. An evaluation of the SCORE program: a novel research and mentoring program for medical students in obstetrics/gynecology and otolaryngology. Perm J. 2020;24:19.153. doi: 10.7812/TPP/19.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gildehaus L, Cotter P, Buck S, Sousa M, Hueffer K, Reynolds A. The research, advising, and mentoring professional: a unique approach to supporting underrepresented students in biomedical research. Innov High Educ. 2019;44(2):119–131. doi: 10.1007/s10755-018-9452-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monarrez A, Morales D, Echegoyen LE, Seira D, Wagler AE. The moderating effect of faculty mentorship on undergraduates students’ summer research outcomes. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2020;19:ar56. doi: 10.1187/cbe.20-04-0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Öcek Z, Bati H, Sezer ED, Köroğlu ÖA, Yilmaz Ö, Yilmaz ND, Mandiracioğlu A. Research training program in a Turkish medical school: challenges, barriers and opportunities from the perspectives of the students and faculty members. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:2. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02454-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wayne PM, Buring JE, Davis RB, Andrews SM, St. John M, Conboy L, Kerr CE, Kaptchuk TJ, Schachter SC. Increasing research capacity at the New England School of Acupuncture through faculty and student research training initiatives. Altern Ther Health Med. 2008;14(2):52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dyck MJ, Novotny NL, Blakeman J, Bricker C, Farrow A, LoVerde J, Nielsen SD, Johnson B. Collaborative student-faculty research to support PhD research education. J Prof Nurs. 2020;36:106–110. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2019.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes SM. Engaging early-career students in research using a tiered mentoring model. ACS Symp Ser Am Chem Soc. 2018;1275:273–289. doi: 10.1021/bk-2018-1275.ch016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrison-Beedy D, Araonowitz T, Dyne J, Mkandawire L. Mentoring students and junior faculty in faculty research: a win-win scenario. J Prof Nurs. 2001;17(6):291–296. doi: 10.1053/jpnu.2001.28184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen TD, Eby LT, Lentz E. Mentorship behaviors and mentorship quality associated with formal mentoring programs: closing the gap between research and practice. J Applied Psychol. 2006;91(3):567–578. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morales DX, Grineski SE, Collins TW. Faculty motivation to mentor students through undergraduate research programs: a study of enabling and constraining factors. Res High Educ. 2017;58(5):520–544. doi: 10.1007/s11162-016-9435-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morales DX, Grineski SE, Collins TW. Increasing research productivity in undergraduate research experiences: exploring predictors of collaborative faculty-student publications. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2017;16(3):ar42. doi: 10.1187/cbe.16-11-0326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hickey JE, Adam M, Elwadia I, Nasser S, Topping AE. A process-environment model of mentoring undergraduate research students. J Prof Nurs. 2019;35:320–324. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K. Research methods in education. 8. London: Routledge; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cutshaw D, O’Gorman T, Beck Dallaghan GL, Swiman A, Joyner BL, Gilliland K, Shea P. Clinical skills simulation complementing core content: development of the Simulation Lab Integrated Curriculum Experience (SLICE) Med Sci Educ. 2019;29(3):643–646. doi: 10.1007/s40670-019-00771-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snadden D, Bates J, Burns P, Casiro O, Hays R, Hunt D, Towle A. Developing a medical school: expansion of medical student capacity in new locations: AMEE Guide No. 55. Med Teach. 2011;33(7):518–529. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.564681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrari R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med Writing. 2015;24(4):230–235. doi: 10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen TD, Eby LT, Poteet ML, Lentz E, Lima L. Career benefits associated with mentoring for protégé: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89(1):127–136. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bower DJ, Diehr S, Morzinski JA, Simpson DE. Support–challenge–vision: a model for faculty mentoring. Med Teach. 1998;20:595–597. doi: 10.1080/01421599880373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coe CL, Piggott C, Davis A, Hall MN, Goodell K, Joo P, South-Paul JE. Leadership pathways in academic family medicine: focus on underrepresented minorities and women. Fam Med. 2020;52(2):104–111. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2020.545847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koehler A, Smith LR, Davies S, Mangan-Danckwart D. Partners in research: developing a model for undergraduate faculty-student collaboration. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2015;12(1):131–142. doi: 10.1515/ijnes-2015-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McSweeney JC, Hudson TJ, Prince L, Beneš H, Tackett AJ, Miller Robinson C, Koeppe R, Cornett LE. Impact of the INBRE summer student mentored research program on undergraduate students in Arkansas. Am Phsyiol Educ. 2018;42:123–129. doi: 10.1152/advan.00127.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Brien T, Hathaway D. Students and faculty perceptions of an undergraduate nursing research internship program. Nurse Educ. 2018;43(2):E1–4. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramani S, Gruppen L, Kachur EK. Twelve tips for developing effective mentors. Med Teach. 2006;28(5):404–408. doi: 10.1080/01421590600825326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sng JH, Pei Y, Toh YP, Peh TY, Neo SH, Krishna LKR. Mentoring relationships between senior physicians and junior doctors and/or medical students: a thematic review. Med Teach. 2017;39(8):866–875. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1332360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ssemata AS, Gladding S, John CC, Kiguli S. Developing mentorship in a resource limited context: a qualitative research study of the experiences and perceptions of the Makerere University student and faculty mentorship programme. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17:123. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0962-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Straus SE, Chatur F, Taylor M. Issues in the mentor-mentee relationship in academic medicine: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2009;84:135–139. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819301ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Straus SE, Johnson MO, Marquez C, Feldman MD. Characteristics of successful and failed mentoring relationships: a qualitative study across two academic health centers. Acad Med. 2013;88:82–89. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827647a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crites GE, Gaines JK, Cottrell S, Kalishman S, Gusic M, Mavis B, Durning SJ. Medical education scholarship: an introductory guide: AMEE Guide No. 89. Med Teach. 2014;36:657–674. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.916791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103–1115. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamby T, Bowman WP, Wilson DP, Basha R. Mentors’ experiences in an osteopathic medical student research program. J Osteopath Med. 2021;121(4):385–390. doi: 10.1515/jom-2020-0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data is associated with this submission.