Abstract

Craniomaxillofacial bone defects represent a clinical challenge in the fields of maxillofacial surgery and (implant) dentistry. Regeneration of these bone defects requires the application of bone graft materials that facilitate new bone formation in a safe, reliable, and predictive manner. In addition to autologous bone graft, several types of (synthetic) bone substitute materials have become clinically available, and still major efforts are focused on improving such bone substitute materials by optimizing their properties. Given the regulatory necessity to evaluate the performance of new bone substitute materials for craniomaxillofacial bone regeneration in a large animal model with similarity to human bone before clinical application, we here describe a mini-pig mandibular bone defect model that allows for the creation of multiple (critical-size) bone defects within the mandibular body of a single animal. As examples of bone substitute materials, we utilize both the clinically used BioOss granules and an experimental calcium phosphate cement for filling the created defects. Regarding the latter, its advantages are the injectable application within the defect site, in which the material rapidly sets, and the tailorable degradation properties via the inclusion of hydrolytically degrading polymeric particles. For both bone substitute materials, we show the suitability of the bone defect model to assess bone regeneration via histology and micro-computed tomography.

Impact statement

Given the regulatory necessity to evaluate the performance of new bone substitute materials for craniomaxillofacial bone regeneration in a large animal model with similarity to the human bone before clinical application, we here describe a mini-pig mandibular bone defect model that allows for the creation of multiple (critical-size) bone defects within the mandibular body of a single animal that can be used for the evaluation of the bone regenerative capacity of new bone grafting materials as well as tissue-engineered products for alveolar bone regeneration.

Keywords: bone defect, mandibula, mini-pig model, bone regeneration

Introduction

Bone possesses the intrinsic capacity for spontaneous healing after injury.1 However, this self-healing capacity of bone tissue can be limited or disrupted, which can hamper the complete healing of the injured bone. For example, large defects beyond a certain size, commonly known as critical-size bone defects, are not able to heal naturally due to their large size.2 If spontaneous bone healing does not occur, a surgical intervention in the form of a bone grafting procedure can be performed to aid the healing process.3

Bone defects do not occur only in orthopedics or neurosurgery, but they are also a frequent problem in dentistry. Loss of alveolar bone can lead to aesthetic as well as functional problems. The major aim of alveolar bone grafting is to restore or enhance the bone volume of the alveolar ridge.4 A bone grafting procedure is based on the transplantation of autologous, allogeneic, or xenogeneic bone into the bone defect.

However, these bone graft materials are associated with several drawbacks, including availability, need for additional surgery, graft-versus-host reaction, graft necrosis, and delayed incorporation.5 An alternative treatment option is the use of synthetic bone graft materials (also called “bone substitute”).

Before a new synthetic bone graft material can be applied for craniofacial bone regeneration in a human patient, animal experiments have to be performed as required by national and international regulations and legislation to ensure their safety and intended performance under in vivo conditions. For the evaluation of craniomaxillofacial bone regeneration, both small (e.g., mouse, rat, and rabbit) and large (e.g., dog, goat, sheep, and pig) animal models are used.

An advantage of small animal models is their ease of use and low costs, but their major disadvantage in testing bone graft materials for craniomaxillofacial application is the fast bone-healing response compared with humans. This makes the interpretation and translation of small animal data toward clinical setting very complex. When selecting a large animal model, it is important that the physiological processes, including bone healing, in the respective animal model optimally match the human situation.

In addition, large animal models have to allow the creation of a critical-sized defect in a location at which the bone structure is similar to the human craniomaxillofacial bone. In view of these requirements, pigs, and particularly mini-pigs, represent an excellent animal model to be used in the final stage of the preclinical testing of biomaterials or tissue-engineered products.6,7 The advantage of (mini-)pigs above other animal models is that their anatomical and physiological features of craniofacial bones are more comparable to humans in comparison with other animal models.

However, a disadvantage of the large, domestic pig is that its increased size and weight, as a consequence of its regular maturation pattern, makes it less suitable for longer implantation studies. Therefore, mini-pigs have been bred, which are smaller and more manageable, but that retain the similarity in craniofacial bone structure with humans. For the testing of craniomaxillofacial medical devices, the calvarium, mandible, and maxilla can be used as implantation sites.7–9

Specifically, the body of the mandible is a load-bearing area and comprises a tube-like structure consisting of a cortical bone at the outside and a bone marrow at the center, which resembles the dento-alveolar architecture of the human mandible10 and has large similarity in bone mineral density to the human bone.11 In addition, the anterior region of the mandibular body is easily accessible from a surgical point of view and the size of the mandibular body is such that a reproducible generation of multiple critical-sized bone defects with clinical validity is possible. This allows the simultaneous comparison of various bone graft materials under similar experimental condition, which also reduces the total number of animals that are necessary to efficiently and reliably analyze the bone regenerative response.

Here, we describe a surgical protocol for the creation of load-bearing critical-sized bone defects in the body of the mini-pig mandible that can be used for the evaluation of the bone regenerative capacity of new bone grafting materials as well as tissue-engineered products for alveolar bone regeneration.

Materials and Methods

Surgical procedure

After shaving and disinfecting the anterior region of the left and right side of the mandible mesial from the first molar, an extra-oral sub-angular incision was made bilaterally to expose the lateral portion of the anterior region of the mandibular body. The incision was made through the fascia and muscle, and the bone was exposed by blunt dissection. Then, full-thickness standardized cylindrical defects, comprising removal of the buccal mandibular cortex, were made by using a trephine dental drill.

After implantation of the bone graft material, the soft tissue was closed in multiple layers by using resorbable sutures. At the end of the designated healing period, animals were euthanized. The mandibles were harvested, excess soft tissue was removed, and with a circular saw the mandibular body was reduced in length by removing the distal and mesial parts that contained teeth. Subsequently, the specimen can be prepared for the analysis of bone regeneration in the bone defects by using different techniques, including microcomputed tomography (micro-CT), mechanical testing, and histology.

Experimental design

Implantation material

Various biomaterials or tissue-engineered constructs can be implanted into the bone defect, provided that their osteocompatibility has been validated earlier in small animal studies. Xenografts, particularly those of bovine origin (e.g., BioOss® by Geistlich Biomaterials), have a long track of clinical use in dento-alveolar surgery.12,13 Frequently, this material is included in a study design as a reference material (FDA; personal communication). Synthetic bone graft materials can be subdivided into three main material classes, that is, biopolymers, bioceramics, and biocomposites.14

Calcium phosphate (CaP) bioceramics are considered the most effective type of synthetic bone graft material for bone regenerative treatment due to their biological performance: CaP-based bone graft materials promote apatite formation in vitro15 and in vivo,16 and they allow direct bone apposition because of their chemical similarity to the mineral phase of bone.17 A disadvantage of CaP bioceramics for dento-alveolar bone regeneration is that they are mainly available in the form of granules or particles.

This hampers their clinical use, as granules/particles are difficult to handle and maintain within a bone defect and cannot be molded to the specific irregular dimensions of a dento-alveolar bone defect. However, calcium phosphate cements (CPCs) have been developed, which are composed of a powder and liquid phase to result in a paste with self-setting properties and are therefore more appealing for such application.18

The CPCs can be injected into the bone defect and molded to the defect shape, which results in an optimal filling and bone contact. The CPCs can be mixed with porogens (e.g., poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) [PLGA]) to create microporosity into the CPC after the setting and degradation of the porogen.19 This results in an accelerated degradation of the CPC and its subsequent replacement with newly formed bone. In addition, CPCs can be used for the delivery of different biologically active substances, such as antibiotics, growth factors, and bioinorganics.20,21 This protocol describes the application of a CPC with an increased degradation speed, which was obtained by the incorporation of degradable poly(lactic-co-glycolic)acid particles into the CPC, for the regeneration of critical-sized defects in the mini-pig mandible.

Implantation time

Various implantation times can be used to study the bone regenerative capacity of a bone graft material or a tissue-engineered construct. Time points are depending on the aim of the study and range from 1 to 26 weeks. At short implantation times (1–2 weeks), information can be obtained about inflammatory response and initial bone formation.22 At longer implantation times, initial bone remodeling events and initial material degradation can be assessed.23 Studies with an end point of 26 weeks will provide information about late bone remodeling, including maintenance of the regenerated bone, and the progression of material degradation.23

Defect

Different sizes and numbers of bone defects can be created in the mini-pig mandibular body.

Standardized experimental studies demonstrated that defects in the mandible of mini-pigs with a volume >5 cm3 are assumed as critical sized.24 In addition to defect volume, periosteal coverage of the defect plays an important role in the formation of new bone. If the periosteum over the bone defect is preserved during surgery, new bone formation proceeds both from the periosteum and from the bone defect edges. On the other hand, if the periosteum is removed during defect creation, even the healing of small-bone defects fails.25

In addition, it has to be noticed that the full-thickness defects have to be generated only in the buccal cortex of the mandibular body and do not penetrate through the lingual cortex to avoid the installation of plates to prevent fracture of the mandible.

Further, defects can have a cylindrical or rectangular/square shape. The diameters of a cylindrical defect can range from 2 to 10 mm. The number of cylindrical defects that can be created depends on the diameter of the defect and the space between the defects. When a 2 mm distance is maintained between the defects, the number of defects can range from 8 (2 mm diameter) to 2 (10 mm diameter) on each side of the mandible. Rectangular/square-shaped defects can also be generated, but they are less common.26

Materials required

Animal species

The currently used mini-pigs are obtained by selective breeding, and various strains are available.6 Each strain has its own characteristics and they can vary considerably in size and weight. The most common mini-pigs used as laboratory animals are the Hanford, Yucatan, and Göttingen strain, which range in size from large (Hanford) to small (Göttingen). Small mini-pigs, such as the Göttingen strain, have a body weight of about 7–9 kg and a body length of about 75 cm.

The advantage of smaller mini-pigs is that they are easier to handle, which makes them more suitable for longer-term implant studies. Mini-pigs are skeletally mature at around 6 months of age. Although female mini-pigs may be housed in pairs, individual housing arrangements may be needed for male mini-pigs due to their potentially aggressive behavior.

In this protocol (AVD1030020197984), 16 adult female Göttingen mini-pigs were used to assess bone defect regeneration at two healing periods, that is., 4 and 12 weeks. The number of animals has to be based on statistical power analysis. The primary outcome parameter in this study design was bone formation. Based on earlier studies, bone formation was estimated to be around 20–30% with a standard deviation of 15%.27 Sample size was calculated based on a two-way ANOVA with an alpha of 0.05, a standard deviation of 15%, and an effect size of 30%. The estimated group size for each healing time and experimental material was eight defects, which corroborates other mini-pig study data for bone regeneration.28

All surgical procedures have to be performed at an accredited animal research facility and have to be in agreement with (inter)national regulations and guidelines about the use of experimental animals.

Personnel and expertise

The team to perform the protocol is recommended to be composed of two researchers serving as primary surgeons and one veterinary technician. The two surgeons should be trained in dental or medical surgery. The veterinary technician needs to have all theoretical and practical skills required for experimental animal studies, that is, the administration, maintenance, and monitoring of inhalation anesthesia. In addition, the presence of an extra assistant or technician is recommended for assistance with providing supplies during the surgical procedure. All involved personnel should have appropriate institutional training and approval.

Equipment and tools

-

1.

Autoclave (Tuttnauer, Mannheim, Germany)

-

2.

Vital signs monitor for ECG, rectal temperature, and pulse oximeter (Datex-Ohmeda, Excel 210SE, Madison, WI)

-

3.

Rectal temperature probe (Datex-Ohmeda, Excel 210SE, Madison, WI)

-

4.

Large animal anesthesia machine (Datex-Ohmeda, Excel 210SE, Madison, WI)

-

5.

Veterinary anesthesia inhalator (Datex-Ohmeda, Excel 210SE, Madison, WI)

-

6.

Warming pad (Datex-Ohmeda, Excel 210SE, Madison, WI)

-

7.

Electric razor (Aesculap, Favorita, I.I., Melsungen, Germany)

-

8.

Cauterization clippers (Valleylab, Force FX, Velbert, Germany)

-

9.

Dental drill unit and contra angled handpiece (W&M, handpiece, maximum 800 r.p.m., Bürmoos, Germany)

-

10.

Dental trephine drill, external diameter 8 mm; internal 7 mm (Meisinger, Neus, Germany)

-

11.

Surgical knife holder (Double bladed Scalpel Handle Hu-Friedy, Tuttlingen, Germany)

-

12.

Surgical knife (Sterile Blade #15, Hu-Friedy, Tuttlingen, Germany)

-

13.

Raspatory (Hu-Friedy, Tuttlingen, Germany)

-

14.

Scissors (Hu-Friedy, Tuttlingen, Germany)

-

15.

Tweezers (Hu-Friedy, Tuttlingen, Germany)

-

16.

Retractor (Hu-Friedy, Tuttlingen, Germany)

-

17.

Spatula (Hu-Friedy, Tuttlingen, Germany)

-

18.

Needle driver (Hu-Friedy, Tuttlingen, Germany)

-

19.

Trephine drill (Meisinger, Neuss, Germany)

-

20.

Diamond saw

-

21.

Micro-CT scanner (Scanco Medical, Brüttisellen, Switzerland)

-

22.

Microtome (Leica SP1600; Leica Biosystems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands)

Reagents and surgical materials

-

1.

Sterile gown, face mask, head cover (Barrier Surgical gown; Barrier Molnlycke Health Care, Breda, The Netherlands), and gloves (Sempermed, supreme, Utrecht, The Netherlands)

-

2.

Endotracheal tube

-

3.

Suction vessel

-

4.

Suction tube

-

5.

Chlorhexidine solution (0.5%)

-

6.

Iodine solution (Mylan, Betadine, 100 mg/mL)

-

7.

Alcohol 70%

-

8.

Surgical towels

-

9.

Nonwoven gauze sponges

-

10.

Venflon Pro Safety infusion set 1.3 × 45 mm, 103 mL/min (BD infusion Therapy, Helsingborg, Sweden)

-

11.

Sterile 50 mL syringes

-

12.

2-0 Vicryl sutures FS-1 (Ethicon, Vicryl plus 24 mm, 3/8c)

-

13.

2-0 Vicryl sutures MH-1 plus (Ethicon, Vicryl plus 31 mm 1/2c)

-

14.

Meloxycam (Metacam, Boehringer, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany)

-

15.

Ketamine (Alfasan, Woerden, The Netherlands)

-

16.

Midazolam (Roche Laboratories, Almere, The Netherlands)

-

17.

Atropine (Centrafarm, Breda, The Netherlands)

-

18.

Amoxicillin (Centrafarm, Breda, The Netherlands)

-

19.

Propofol

-

20.

Isoflurane (Isoflutek, Fendigo Laboratories Karizoo, Sevilla, Spain)

-

21.

Oxygen

-

22.

Sufentanil (Butrans, Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals B.V., Mechelen, Belgium)

-

23.

Lidocain/Bupivacaine (Aurobindo Pharma B.V. Baarn, The Netherlands)

-

24.

Buprenorphine (Butrans, Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals B.V., Mechelen, Belgium)

-

25.

Euthanasia solution

-

26.

Tissue specimen bags

-

27.

Formalin

-

28.

Ethanol

-

29.

Methylmethacrylate (MMA) embedding medium

Experiment

Example bone substitute

-

1.

Prepare CPC as previously described.29 Briefly, alpha-tricalcium phosphate (TCP) powder was combined with PLGA particles and homogenously dispersed throughout the CPC powder. Before installation in the bone defect, the CPC powder was mixed with 4% sodium phosphate solution to obtain a paste, which set in situ after its application into the bone defect. The final sterilization was performed by gamma irradiation with 25 kGy (Synergy Health, Ede, The Netherlands).

BioOss small (S) granules (Geistlich Pharma, Wolhusen, Switzerland) were used as a predicate device to compare performance for guided bone regeneration (GBR) A BioGuide GBR membrane (Geistlich Pharma) with mini-titan fixation pins (Botiss Dental, Berlin, Germany) were used to prevent soft tissue ingrowth into the defect filled with BioOss.

Preoperative preparation

-

2.

Autoclave dental handpiece and surgical tool set for each animal.

-

3.

Prepare CPC-PLGA, sterilize, and store appropriately.

-

4.

Purchase BioOss S granules and BioGuide membranes and store appropriately.

-

5.

Prepare surgical table, that is, place warming pad and cover table with absorbent cover.

-

6.

Install dental drill unit and place unit on a nonoperating table covered with a sterile surgical drape.

-

7.

Deposit surgical tools on a nonoperating table covered with a sterile surgical drape.

Surgical induction

-

8.

Before surgery, all animals were given an intramuscular injection of ketamine (10 mg/kg, Ketamine; Alfasan), midazolam (0.6 mg/kg, Dormicum; Roche Laboratories), and atropine 50 μg/kg; Centrafarm).

-

9.

An intravascular (i.v.) winged infusion set (Venflon) was applied in the ear of the mini-pig.

-

10.

General anesthesia was induced by propofol i.v. (2.5 mg/kg; Fresenius Kabi, The Netherlands). Prophylactic Amoxicillin (20 mg/kg; Centrafarm) was administered by i.v. infusion. Also, preoperatively pain medication was given by an intramuscular injection of Meloxicam (15 mg/mL, Metacam; Boehringer).

-

11.

An electric razor was used to shave the left and right surgical area. Subsequently, surgical sites were scrubbed with 0.5% chlorhexidine solution and disinfected with iodine (Mylan, Betadine, 100 mg/mL).

-

12.

The mini-pig was placed on the surgical preparation room table, and the mini-pig was intubated by using a cuffed endotracheal tube. Isoflurane 1.0–1.5% ET (Isoflutek; Fendigo Laboratories Karizoo) and oxygen were administered.

-

13.

Remifentanyl was administered by i.v. infusion (0.03 mg/kg/h, Ultiva), and a Buprenorphine patch was placed (20 μg/h, Butrans; Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals B.V.).

-

14.

The animal and surgical site were covered with sterile drapes.

-

15.

A combination (1:1) of Lidocain (0.4 mg/kg; Fresenius, The Netherlands) and Bupivacaine (0.4 mg/kg; Aurobindo Pharma) was administered at the surgical sites for local anesthesia and reduction of bleeding.

Defect generation and implantation

-

16.

Surgery was performed on each side of the jaw separately.

-

17.

The underside of the mandible was palpated, and a subangular incision was made through the skin parallel to the longitudinal axis of the body of the mandible. The incision ran from the first molar to the canine and was about 5 cm in length. The muscle tissue became visible. An incision was made through the muscle to the bone surface of the mandibular body. An incision was made through the periosteum and the musculo-periosteal flap was raised by blunt dissection with a raspatory to expose the bone surface of the mandibular body. If blood vessels are cut, apply pressure with a sterile gauze to stop bleeding. If a larger blood vessel is cut, clamp the cut vessel with a tweezer and stop bleeding by saucerization.

-

18.

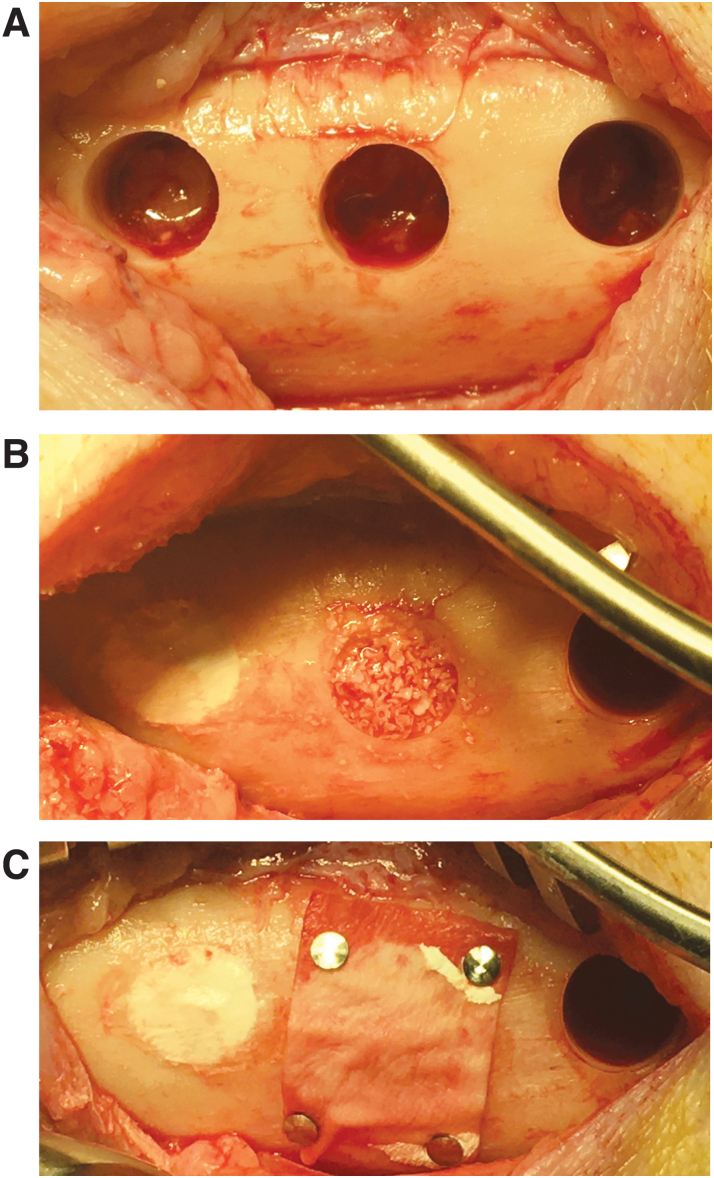

The 8 mm trephine drill was inserted into the handpiece. The drill was aligned perpendicular to the bone surface and drilling was done at low speed (maximum 800 r.p.m.) to penetrate the cortex of the mandibular body. During defect drilling, the other primary surgeon should irrigate the drill site by dripping a sterile physiological sodium solution from a 50 mL disposable syringe. Drilling was stopped when the cortex was penetrated, and the loose cortical part was removed with an Ash 6 (Fig. 1A).

-

19.

The bone defect was cleaned by rinsing with sodium solution, and the defect was dried with a sterile gauze. Pressure was applied with a sterile gauze on the exposed bone marrow if bleeding occurred.

-

20.

Preparation of the next defect was continued, if more than one defect had to be created in the mandibular body (Fig. 1A).

-

21.

The preparation of the bone substitute was commenced, and the bone substitute was installed into the cylindrical bone defect. The bone substitute was adapted to the defect borders with help of a spatula and Ash 6. A GBR membrane was applied in combination with mini-titan fixation pins after installation of the bone substitute, if this was part of the study design (Fig. 1B, C).

-

22.

The heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation were continuously monitored during surgery.

FIG. 1.

Overview of the surgical procedure. (A) Three circular defects (diameter: 8 mm) as created in the mini-pig mandibular body. (B) Circular defects filled with CPC/PLGA (left) or BioOss (middle). (C) Placement of a GBR membrane (BioGuide) with mini-titan fixation pins to prevent soft tissue ingrowth into the defect filled with BioOss; the solid nature of CPC/PLGA makes that a GBR membrane is not necessary for this bone graft material. CPC/PLGA, calcium phosphate cement/poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid); GBR, guided bone regeneration.

Wound closure

-

23.

The periosteum was sutured by using 3-0 Vicryl sutures FS-1 (Ethicon, Vicryl plus 24 mm, 3/8c, Norderstedt, Germany) in a continuous pattern.

-

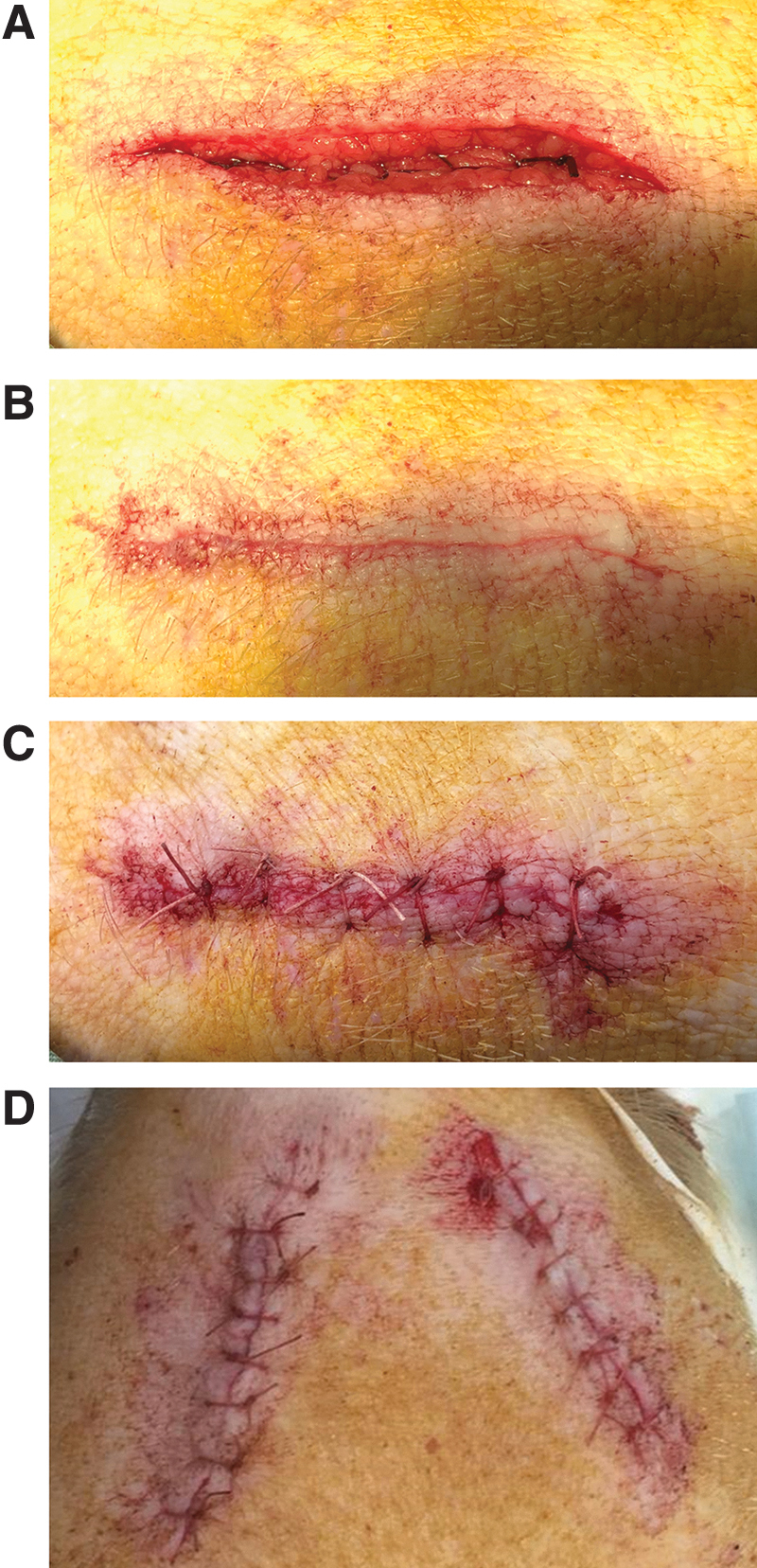

24.

The muscle layer was sutured by using 3-0 Vicryl sutures FS-1 (Ethicon, Vicryl plus 24 mm, 3/8c Norderstedt, Germany) in a continuous pattern (Fig. 2A).

-

25.

The skin was sutured by using 2-0 Vicryl sutures (MH-1 plus) (Ethicon, Vicryl plus 31 mm 1/2c Norderstedt, Germany) using an intracutaneous continuous pattern (Fig. 2B). In addition, with the running sutures, it is probably necessary to place extra sutures in the middle of the wound to secure closure of the outer skin layer (Fig. 2C).

-

26.

Bleeding was checked for, and the wound was closed. The wound area was cleaned, and a tissue adhesive was applied.

-

27.

The other side of the mandible was dealt with in the same manner, and the same procedure was performed (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

Overview of the suturing techniques to close the different layers of the surgical site. (A) Resorbable sutures were used to close fascia layers. (B) The skin is closed with a continuous, intracutaneous suture. (C) Extra sutures were placed in the middle to secure closure of the outer skin layer. (D) Aspect of the mini-pig mandible after bilateral creation of mandibular bone defects; the wound area is cleaned, and tissue adhesive is administered.

Postoperative care

-

28.

Isoflurane was stopped, and Buprenorfine i.v. (0.05 mg/kg, Butrans; Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals B.V.) was administered to control immediate postoperative pain. When the animals had stable saturation and independent breathing, they returned to the animal facility and were checked individually.

Euthanasia and tissue retrieval

-

29.

The mini-pig was weighed to determine drug dosages. The mini-pig was secured in the weighing scale.

-

30.

An intramuscular injection of ketamine (10 mg/kg, Ketamine; Alfasan) and midazolam (0.6 mg/kg, Dormicum; Roche Laboratories) was administered.

-

31.

An intracardial (i.c) injection overdose of pentobarbital (Euthasol, 50%) was administered.

-

32.

Lack of cardiovascular function was verified by the absence of heartbeat, respiration, and eye reflex.

-

33.

A cut was made to the skin and muscles by using a scalpel and scissors to isolate the mandible. The complete mandible was removed with a circular saw.

-

34.

The residual tissues were removed, and the specimen was cut into a smaller size by using a diamond saw, which contained only the bone defects. The lingual cortex was removed as much as possible. The remaining bone marrow in the mandibular canal was removed by using a scalpel and Ash 6.

-

35.

The tissue specimen was fixed in ∼100 mL of 4% neutral-buffered formalin at room temperature for 5 days on a shaking table.

-

36.

Each fixed tissue specimen was stored in ∼100 mL of 70% ethanol at room temperature on a shaking table.

Analysis

-

37.

Micro-CT was performed on mandibular body specimens, using a μCT100 imaging system (Scanco Medical) or a similar instrument to assess the remaining bone graft material and bone regeneration into the defect area.

-

38.

Compressive and push-out mechanical testing was performed, using a tensile bench to assess the mechanical properties of the regenerated bone defect.

-

39.

For histological analysis, the specimens were dehydrated in a gradient series of ethanol (from 70% to 100%) for 12 h each. Subsequently, the specimens were embedded into MMA and histological sections of 15–20 μm were cut by using an inner circular saw microtome (Leica SP1600; Leica Biosystems). Finally, the sections were stained by using methylene blue and basic fuchsin and assessed by light microscopy and histomorphometry.

The presented protocol has been validated in several studies to assess the bone regenerative capacity of synthetic bone graft substitutes. An example of such a study including the obtained data is discussed next. In this study, micro-CT and histology were the primary techniques used for specimen analysis.

Bone substitute and surgical procedure

This study focuses on the efficacy of CPC/PLGA as a bone substitute material. For bone regenerative efficacy, mandibular defects were filled with CPC/PLGA or BioOss; BioOss was subsequently covered with a collagen GBR membrane (BioGuide). At the end of the designated healing period, the retrieved samples were subjected to micro-CT and histologic/histomorphometric analysis to determine bone formation into the defect.

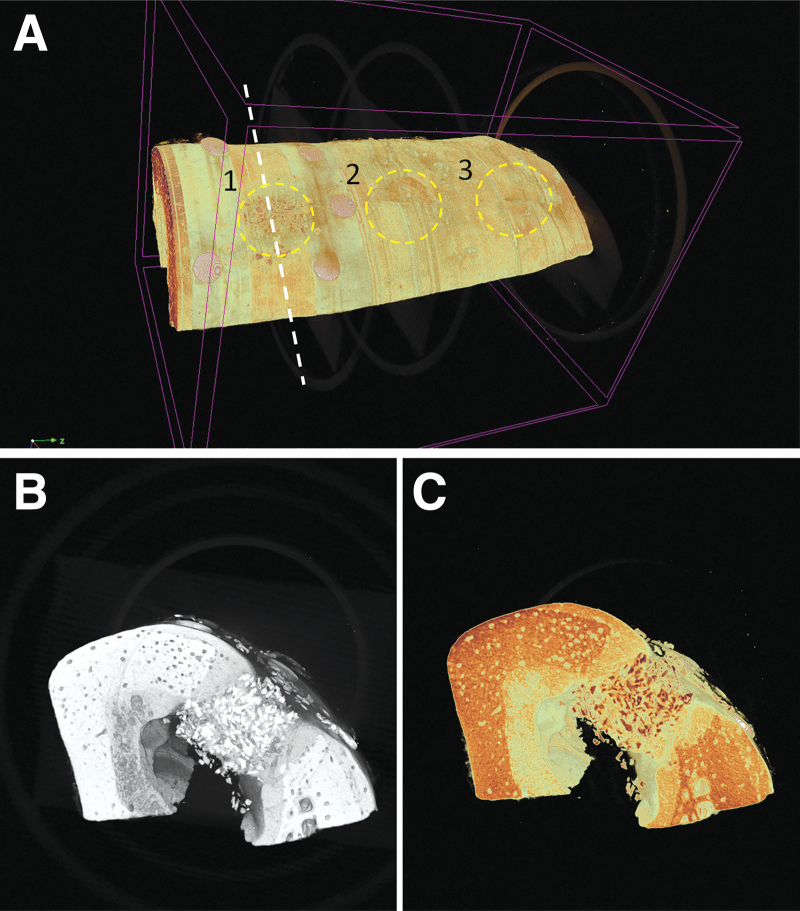

Micro-CT

Micro-CT is a nondestructive imaging technique that provides 3D information about bone formation into the defect. Micro-CT makes the use of X-rays a threshold to distinguish between the recorded gray values for image reconstruction. Bone and bone-mineral graft material have similar X-ray density, which hampers the accurate calculation of the regenerated bone volume. On the other hand, the images can still be used to provide subjective information about closure of the bone defect (Fig. 3A, B).

FIG. 3.

3D reconstruction of the defect area using micro-CT imaging. (A) Full aspect of the mandibular area in which critical-size defects were created and filled with bone graft material. Note the three created defects (indicated with 1, 2, 3) and the presence of titan mini-pins used for fixation of the GBR membrane on top of the BioOss filled defect (1). (B) Lingual-buccal cross-section of the mandible at the region of defect 1. Note the difference in appearance between BioOss in the defect area and the surrounding cortical bone. (C) Color contrast was applied to visually enhance the difference in appearance between the different calcified structures. micro-CT, microcomputed tomography.

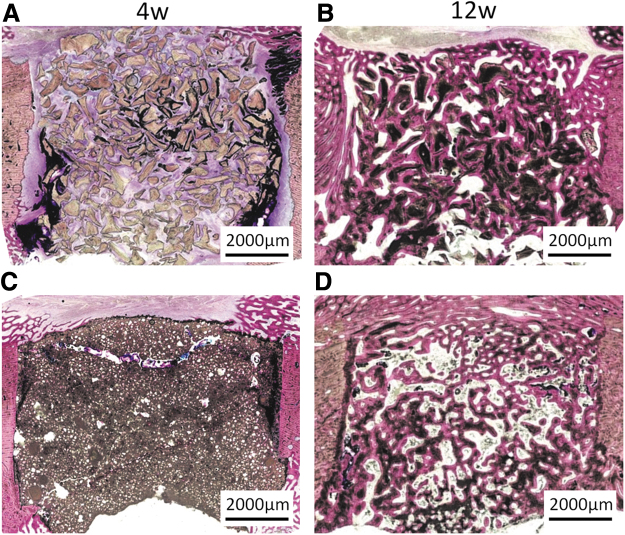

Histology and histomorphometry

Bone specimens can be prepared for histologic analysis by following the cycle of dehydration and embedding. As bone is a mineralized tissue, it is difficult to section. Therefore, before embedding, the bone specimens are decalcified by immersion in EDTA. After completion of the decalcification process, they are embedded in paraffin and light microscopical sections are made by using a standard microtome. The sections can be stained by using various stains to discern specific tissue structures. Also, undecalcified bone sections can be made.

For this, the bone specimens are embedded in methylmethacrylate after fixation. To allow a proper penetration of the MMA into the bone specimen, it is necessary that the bone marrow is removed as much as possible out of the specimen. After embedding in MMA, sections can be made by using a specialized microtome (Fig. 4A–D). The advantage of MMA embedding is that no damage to the sections occurs due to the calcification and during sectioning. A disadvantage of MMA embedding is that the number of stains to indicate specific tissue structures is limited.30

FIG. 4.

Histological cross-sections of mini-pig mandibular bone defects with a diameter of 8 mm after 4 and 12 weeks of healing following embedding in MMA, sectioning using an inner circular diamond saw, and staining with methylene blue/basic fuchsin [38] (original magnification × 400). The bone defects were filled with BioOss and CPC/PLGA. (A) BioOss filled defect after 4 weeks of implantation. The BioOss particles can easily be discerned. Bone ingrowth into the defect and between the particles is very limited. Only new bone formation occurred at the subperiosteal and endosteal surface of the bone defect. (B) BioOss filled defect after 12 weeks of implantation. Bone has grown into the defect area, and the majority of BioOss particles are surrounded by bone (C) CPC/PLGA filled defect after 4 weeks of implantation. After 4 weeks of implantation, the CPC/PLGA is still present and completely occupies the bone defect. Micro-pores can be observed within the CPC/PLGA, which is due to degradation of the PLGA. (D) CPC/PLGA filled defect after 12 weeks of implantation. The CPC/PLGA has almost completely degraded, and the created space has been filled to a large extent with newly deposited bone. MMA, methylmethacrylate.

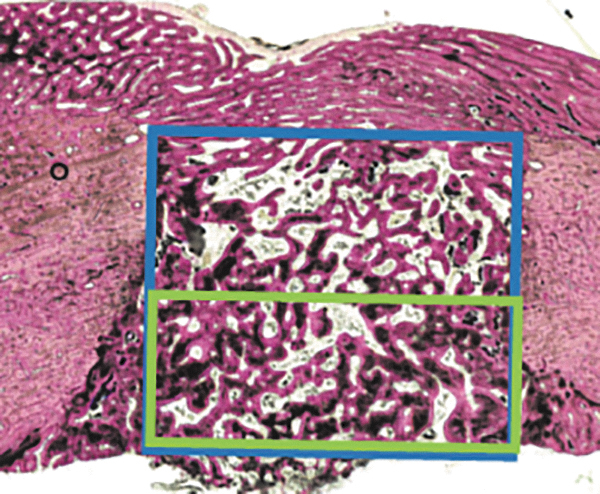

Histomorphometry allows the quantitative assessment of the bone regeneration in the created defect.31,32 Such a quantification can be performed by using computer-based image analysis software and starts with defining the size and location of a representative region of interest in the histological sections (Fig. 5). Subsequently, measurement of the parameters of interest takes place.

FIG. 5.

Illustration of the histomorphometric procedure that allows for quantitative assessment of bone regeneration in the created defect that starts with defining the size and location of a representative region of interest in the histological sections. For this, a rectangular box can be projected over the histological image, either in the middle (blue box) or at the border (green box) to quantify a specific region of the bone defect. The relative area of bone tissue (based on staining and morphology) can be quantified by using image analysis software (ImageJ2; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

A commonly used parameter is the relative volume or regenerated bone, but also other parameters can be calculated, such as trabecular number, trabecular thickness, trabecular separation, and marrow area. In addition to bone histomorphometry, the degradation rate of the applied graft material can be determined. Further, if fluorescent labels are used to demonstrate the mineralization front, the appositional rate of bone formation can be determined.

Conclusion

In this protocol, we describe a reproducible and standardized technique to create critical-sized bone defects in the mandibular body of mini-pigs for the assessment of the bone regenerative capacity of bone graft materials and tissue-engineered products. At the end of the study, the obtained specimens can be subjected to various analytical techniques to assess the bone regeneration into the defect.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Natasja van Dijk and Vincent Cuijpers for preparing the histological MMA sections and histological analyses. The authors also acknowledge the support of Bert van Rietbergen from the department of Biomedical Engineering, Eindhoven University, for his assistance and advice in performing the X-ray Micro-CT scans.

Authors' Contributions

All people listed as authors declare that they have participated significantly in the work, including participation in the concept, design, analysis, writing, or revision of the article.

Disclosure Statement

Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the Army, Navy, NIH, Air Force, VA and Health Affairs to support the AFIRM II effort, under Award No. W81XWH-14-2-0004. The U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity, 820 Chandler Street, Fort Detrick, MD 21702–5014 is the awarding and administering acquisition office.

References

- 1. Giannoudis, P.V., Jones, E., and Einhorn, T.A.. Fracture healing and bone repair. Injury 42, 549, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Perry, C.R. Bone repair techniques, bone graft, and bone graft substitutes. Clin Orthop Relat Res 71, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Van der Stok, J., Van Lieshout, E.M., El-Massoudi, Y., Van Kralingen, G.H., and Patka, P.. Bone substitutes in the Netherlands—a systematic literature review. Acta Biomater 7, 739, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mansour Alaa, A. Alveolar bone grafting: rationale and clinical applications. In: Alghamdi, H., and Jansen, J., eds. Dental Implants Bone Grafts Sawston, United Kingdom: Woodhead Publishing, 2020. pp. 43–87. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Giannoudis, P.V., Dinopoulos, H., and Tsiridis, E.. Bone substitutes: an update. Injury 36, 20, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Swindle, M.M., Makin, A., Herron, A.J., Clubb, F.J.Jr., and Frazier, K.S.. Swine as models in biomedical research and toxicology testing. Vet Pathol 49, 344, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kantarci, A., Hasturk, H., and Van Dyke, T.E.. Animal models for periodontal regeneration and peri-implant responses. Periodontol 2000 68, 66, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schwarz, F., Sculean, A., Engebretson, S.P., Becker, J., and Sager, M.. Animal models for peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000 68, 168, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mardas, N., Dereka, X., Donos, N., and Dard, M.. Experimental model for bone regeneration in oral and cranio-maxillo-facial surgery. J Invest Surg 27, 32, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pearce, A.I., Richards, R.G., Milz, S., Schneider, E., and Pearce, S.G.. Animal models for implant biomaterial research in bone: a review. Eur Cell Mater 13, 1, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aerssens, J., Boonen, S., Lowet, G., and Dequeker, J.. Interspecies differences in bone composition, density, and quality: potential implications for in vivo bone research. Endocrinology 139, 663, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Starch-Jensen, T., Aludden, H., Hallman, M., Dahlin, C., Christensen, A.E., and Mordenfeld, A.. A systematic review and meta-analysis of long-term studies (five or more years) assessing maxillary sinus floor augmentation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 47, 103, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Valentini, P., Abensur, D., Densari, D., Graziani, J.N., and Hammerle, C.. Histological evaluation of Bio-Oss in a 2-stage sinus floor elevation and implantation procedure. A human case report. Clin Oral Implants Res 9, 59, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bongio, M., van den Beucken, J.J.J.P., Leeuwenburgh, S.C.G., and Jansen, J.A.. Development of bone substitute materials: from ‘biocompatible’ to ‘instructive’. J Mater Chem 20, 8747, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kokubo, T., Takadama, H.. How useful is SBF in predicting in vivo bone bioactivity? Biomaterials 27, 2907, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leeuwenburgh, S.C., Wolke, J.G., Siebers, M.C., Schoonman, J., and Jansen, J.A.. In vitro and in vivo reactivity of porous, electrosprayed calcium phosphate coatings. Biomaterials 27, 3368, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davies, J.E. Bone bonding at natural and biomaterial surfaces. Biomaterials 28, 5058, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Habraken, W., Habibovic, P., Epple, M., and Bohner, M.. Calcium phosphates in biomedical applications: materials for the future? Mater Today 19, 69, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lodoso-Torrecilla, I., van den Beucken, J., and Jansen, J.A.Calcium phosphate cements: optimization toward biodegradability. Acta Biomater 119: 6985, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jansen, J.A., Vehof, J.W., Ruhe, P.Q., et al. Growth factor-loaded scaffolds for bone engineering. J Control Release 101, 127, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van de Watering, F.C., Molkenboer-Kuenen, J.D., Boerman, O.C., van den Beucken, J.J., and Jansen, J.A.. Differential loading methods for BMP-2 within injectable calcium phosphate cement. J Control Release 164, 283, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vehof, J.W., Takita, H., Kuboki, Y., Spauwen, P.H., and Jansen, J.A.. Histological characterization of the early stages of bone morphogenetic protein-induced osteogenesis. J Biomed Mater Res 61, 440, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bodde, E.W., Wolke, J.G., Kowalski, R.S., and Jansen, J.A.. Bone regeneration of porous beta-tricalcium phosphate (Conduit TCP) and of biphasic calcium phosphate ceramic (Biosel) in trabecular defects in sheep. J Biomed Mater Res A 82, 711, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Henkel, K.O., Bienengraber, V., Lenz, S., and Gerber, T.. Comparison of a new kind of calcium phosphate formula versus conventional calcium phosphate matrices in treating bone defects—a long-term investigation in pigs. Key Eng Mat 284–286, 885, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huh, J.Y., Choi, B.H., Kim, B.Y., Lee, S.H., Zhu, S.J., and Jung, J.H.. Critical size defect in the canine mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med O 100, 296, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. De Santis, E., Lang, N.P., Favero, G., Beolchini, M., Morelli, F., and Botticelli, D.. Healing at mandibular block-grafted sites. An experimental study in dogs. Clin Oral Implants Res 26, 516, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jensen, S.S., Yeo, A., Dard, M., Hunziker, E., Schenk, R., and Buser, D.. Evaluation of a novel biphasic calcium phosphate in standardized bone defects: a histologic and histomorphometric study in the mandibles of minipigs. Clin Oral Implants Res 18, 752, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dau, M., Kammerer, P.W., Henkel, K.O., Gerber, T., Frerich, B., and Gundlach, K.K.. Bone formation in mono cortical mandibular critical size defects after augmentation with two synthetic nanostructured and one xenogenous hydroxyapatite bone substitute - in vivo animal study. Clin Oral Implants Res 27, 597, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Felix Lanao, R.P., Leeuwenburgh, S.C., Wolke, J.G., and Jansen, J.A.. Bone response to fast-degrading, injectable calcium phosphate cements containing PLGA microparticles. Biomaterials 32, 8839, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van der Lubbe, H.B., Klein, C.P., and de Groot, K.. A simple method for preparing thin (10 microM) histological sections of undecalcified plastic embedded bone with implants. Stain Technol 63, 171, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Walsh, W.R., Oliver, R.A., Christou, C., et al. Critical size bone defect healing using collagen-calcium phosphate bone graft materials. PLoS One 12, e0168883, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Houdt, C.I.A., Cardoso, D.A., van Oirschot, B., et al. Porous titanium scaffolds with injectable hyaluronic acid-DBM gel for bone substitution in a rat critical-sized calvarial defect model. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 11, 2537, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]