Abstract

Dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), an abundant osmoprotectant found in marine algae and salt marsh cordgrass, can be metabolized to dimethyl sulfide (DMS) and acrylate by microbes having the enzyme DMSP lyase. A suite of DMS-producing bacteria isolated from a salt marsh and adjacent estuarine water on DMSP agar plates differed markedly from the pelagic strains currently in culture. While many of the salt marsh and estuarine isolates produced DMS and methanethiol from methionine and dimethyl sulfoxide, none appeared to be capable of producing both methanethiol and DMS from DMSP. DMSP, and its degradation products acrylate and β-hydroxypropionate but not methyl-3-mecaptopropionate or 3-mercaptopropionate, served as a carbon source for the growth of all the α- and β- but only some of the γ-proteobacterium isolates. Phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences showed that all of the isolates were in the group Proteobacteria, with most of them belonging to the α and γ subclasses. Only one isolate was identified as a β-proteobacterium, and it had >98% 16S rRNA sequence homology with a terrestrial species of Alcaligenes faecalis. Although bacterial population analysis based on culturability has its limitations, bacteria from the α and γ subclasses of the Proteobacteria were the dominant DMS producers isolated from salt marsh sediments and estuaries, with the γ subclass representing 80% of the isolates. The α-proteobacterium isolates were all in the Roseobacter subgroup, while many of the γ-proteobacteria were closely related to the pseudomonads; others were phylogenetically related to Marinomonas, Psychrobacter, or Vibrio species. These data suggest that DMSP cleavage to DMS and acrylate is a characteristic widely distributed among different phylotypes in the salt marsh-estuarine ecosystem.

Dimethyl sulfide (DMS)-producing bacteria play an important but as yet unquantified role in the biogenic transfer of sulfur from the ocean to the atmosphere (2, 25, 30). DMS production results from the enzymatic degradation of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) (9, 28, 43), an osmoprotectant (13, 14, 22, 47) produced and stored by marine phytoplankton, macroalgae, cyanobacteria, and coastal vascular plants (e.g., Spartina alterniflora) (7, 8, 23, 38, 50). When these organisms senesce and decay or phytoplankton are grazed upon by zooplankton, the intracellular DMSP is released into the water column or sediment (9, 35, 53), where it can be used as a carbon and energy source for the bacterial community (25, 49). The enzymatic degradation of DMSP to DMS and acrylate has been observed in marine and estuarine bacteria (11, 25, 31), fungi (4), and algae (6, 22, 41). The enzyme responsible, DMSP lyase, has been purified from several marine bacteria (11, 12, 48).

Understanding the factors controlling DMS production in the marine environment relies on knowing the abundance, phenotypic diversity, and physiology of the microbes involved in this process. As there is not a functional probe available to quantitate and identify DMS-producing microbes in environmental samples, studies of DMS production have been limited to isolation and characterization of DMS-producing strains (11, 17, 21, 25, 31, 48, 52). The limitations in culturing marine bacteria have long been known (see reference 36), so it is probable that only a small percentage of DMS producers have been isolated. In recent studies of the diversity of DMS-producing bacteria from oceanic and estuarine waters it was found that all the isolates belonging to the Roseobacter subgroup of the α subdivision of the Proteobacteria were DMS producers (17, 31). Since the Roseobacter group accounted for almost 30% of the 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) in coastal and estuarine water (19), it suggested that this group of DMS-producing bacteria is quite common in the marine environment (17). However, other DMS-producing phylotypes from the marine environment belonging to the β (11), γ (21, 31), and δ (48) subdivisions of the Proteobacteria have also been identified, but their prominence remains unknown.

S. alterniflora-dominated salt marshes represent another marine ecosystem where DMS production occurs. In fact the rates per unit area of salt marsh are much higher than those of coastal and ocean water (42) and may support a unique assemblage of DMS producers. The focus of this research was to assess the phenotypic and phylogenetic diversity of DMS-producing bacteria from the marsh and adjacent estuarine waters. The culturable DMS producers from these sources obtained by plating dilutions on minimal DMSP medium as described below belonged predominantly to the γ subdivision and, to a lesser extent, the α subdivision of Proteobacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of DMS-producing bacteria.

Surface sediment and estuarine water samples (salinity, ca. 35 ppt) were obtained from North Inlet, Georgetown, S.C. DMS-producing bacteria were obtained by plating serial dilutions of estuarine water or sediment slurries directly on modified basal salts (3) or f/2 medium supplemented with DMSP (1 mM). The latter is a minimal, seawater-based medium (20). Additional isolates were obtained from 5-day enrichment cultures grown in f/2-DMSP medium, followed by plating of serial dilutions onto f/2-DMSP agar plates. In both cases the dilutions were sufficient to yield 30 to 100 colonies when 100 μl was spread on plates of marine broth (Bacto). After several days of growth, colonies with diverse morphologies were selected for further testing after purification.

Production of volatile organosulfur compounds.

Isolates were grown in either marine or tryptic soy broth (5-ml cultures) for 24 h, at which time the cultures reached maximum turbidity. The cultures were harvested by centrifugation for 30 s, the pellet was resuspended in an equal volume of half-strength seawater, and 1-ml aliquots were placed in 14.5-ml glass serum bottles. Organosulfur compounds (DMSP, methionine, dimethyl sulfoxide, methyl-3-mercaptopropionate [MMPA], or 3-mercaptopropionate [MPA]) were added at 1 mM concentrations from 150 mM neutralized stock solutions, and the cultures were incubated at 23°C for 3 days on a rotary shaker (100 rpm). DMS, hydrogen sulfide, and methanethiol were analyzed at 24-h intervals by gas chromatography as described previously (11).

Growth substrates.

Overnight cultures grown in minimal medium containing 0.05% yeast extract were used to inoculate tubes of minimal media (either f/2 or modified basal salts) containing either DMSP, acrylate, β-hydroxypropionate (β-HP), glycine betaine (GBT), MPA, or MMPA as the carbon and energy source. All the carbon sources were added to a final concentration of 5 mM from a filter-sterilized stock solution to autoclaved media. Cultures were incubated on a roll shaker at 30°C, and growth was monitored with a Klett spectrophotometer.

Isolation of chromosomal DNA and PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene.

Isolates were grown on either tryptic soy or marine broth overnight and then subcultured into 50 ml of the same medium for 5 h at 37°C on a rotary shaker (150 rpm). Cells were harvested by centrifugation (6,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C), and chromosomal DNA was isolated from cell pellets using a standard procedure (33). Purified DNA from the DMS-producing isolates was used as the template in a PCR to amplify the 16S rRNA coding regions. Bacterium-specific primers (GM3F and GM4R) (see Table 1) were used to amplify the 16S rRNA gene. PCR mixtures contained the following per 50 μl of reaction mixture: ca. 10 ng of template, 45 pmol of each primer (GM3F and GM4R), 10 μmol of each deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate, 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and TaqBead Hot Start polymerase (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.). PCR amplifications were performed using an Eppendorf Mastercycler gradient. To reduce the chance of spurious by-product formation and increase the specificity of the amplification, a “touchdown” PCR was performed (15). Denaturation of the DNA was carried out at 94°C for 30 s, while the annealing temperature was set at 50°C, which was 10°C above the expected annealing temperature. The temperature was decreased by 1°C every second cycle until a touchdown of 40°C was achieved, at which temperature 10 additional cycles were carried out. Elongation was carried out at 72°C for 2 min, with a total of 30 cycles.

TABLE 1.

Primer sequences and positions

| Primer | Positionsa | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| GM3Fb | 8–24 | 5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGC-3′ |

| GM4Rb | 1492–1507 | 5′-TACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′ |

| DY23 | 341–357 | 5′-CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′ |

| DY24 | 907–926 | 5′-CCGTCAATTCCTTTGAGTTT-3′ |

The numbering of the positions is according to that of the 16S rRNA of E. coli.

Forward and reverse primers were used to amplify almost the entire 16S rRNA gene from chromosomal DNA.

PCR products (5 μl) were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 0.8% (wt/vol) agarose gel to ensure the correct size of the amplified DNA. Products were then purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.) and ligated into the pGem-T vector (Promega), and the hybrid vector was used to transform Escherichia coli JM109 competent cells (Promega). PCR purification, ligation, and transformation were performed using the manufacturer's instructions. Recombinants were selected on tryptic soy agar plates supplemented with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, and 100 μg of ampicillin · ml−1. Transformants harboring the hybrid vector (white colonies) were subsequently patched onto tryptic soy agar plates supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin · ml−1 and analyzed for the 16S rRNA gene plasmid insert by a colony PCR procedure using the GM3F and GM4R primers. One positive clone harboring the 16S rRNA gene insert from each DMS-producing isolate was chosen for partial sequence analysis.

Plasmid isolation and 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

Plasmids were purified from transformants grown overnight in tryptic soy Broth (5 ml) supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin · ml−1 using the alkaline pH method (5). The 16S rRNA gene insert was amplified using M13 primers that are complementary to the plasmid sequences flanking the insert. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation was carried out at 95°C for 3 min followed by 36 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 20 s, annealing at 50°C for 20 s, and elongation at 72°C for 1.5 min. PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit. Sequences spanning the V3 and V5 hypervariable regions of the rRNA gene (35a) were sequenced on both strands using primers DY23 and DY24 (Table 1). Primer DY23 corresponds to positions 341 to 357 of the E. coli numbering system, and DY24 corresponds to positions 907 to 926 of the E. coli numbering system. The sequences were determined using the ABI Prism BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit and ABI Prism 377 sequencer according to the manufacturer's directions. Complementary sequences were aligned using the Sequencer program (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, Mich.).

Phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rDNA sequences.

To determine the nearest phylogenetic neighbors, each partial sequence of the cloned 16S rDNA genes was compared to the National Center for Biotechnology Information GenBank database using a homology search tool, BLAST (1). For phylogenetic trees, sequences were aligned using the CLUSTAL W multiple sequence alignments program (version 1.81) (46). The alignment was performed using several bacteria that were closely related to the unknown organisms based on information obtained using the BLAST search and unrelated phyla as outgroups. Additional details are given in the figure legends.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rDNA sequences of the isolates from the North Inlet, S.C., salt marsh and estuary and their GenBank accession numbers are as follows: JA6, AF296133; JA33, AF296134; JA41, AF296135; JA22, AF296136; JA3, AF296137; JA1 AF296139; JA14, AF296139; JA11, AF296140; JA17, AF296141; JA42, AF296142; JA31, AF296143; JA32, AF296144; JA23, AF296145; JA27, AF296146; JA13, AF296147; JA35, AF296148; JA45, AF296149; JA29, AF296150; JA30, AF296151; JA20, AF296152; JA9, AF296153; JA19, AF296154; JA34, AF296155; JA16, AF296156; and JA25, AF296157. Isolate M3A was identified earlier as Alcaligenes faecalis strain M3A (AF155147).

Reference 16S rDNA sequences from the GenBank database used in the phylogenetic analyses were as follows, by group.

(i) α-Proteobacteria.

Rhodospirillum rubrum, X87278; SAR11, X52172; Agrobacterium tumefaciens, D13943; Paracoccus denitrificans, X69159; Rhodobacter sphaeroides, D16424; Roseobacter sp. strain DSS-1, AF098492; Sulfitobacter sp. strain DSS-2, AF098490; Silicibacter sp. strain DSS-3, AF098491; Marinosulfonomonas methylotrophus, U62894; Sulfitobacter mediterraneus, Y17387; Roseobacter denitrificans, M96746; Roseobacter gallaeciensis, Y13244; Antarctobacter heliothermus, Y11552; Ruegeria atlantica, AF124521; Silicibacter lacuscaerulensis, U77644; Sagittula stellata E-37, U58356; strain LFR (DMSP-degrading bacterium), L15345; and uncultured marine bacterium D033, AF177566. Bacillus subtilis, AB018486, was used as an outgroup.

(ii) β-Proteobacteria.

Alcaligenes faecalis strain M3A (ATCC 700596), AF155147; Alcaligenes faecalis, D88008; Alcaligenes strain 05-36, X86580; Alcaligenes defragrans, AJ005450; Ralstonia eutropha, Y10825; Bordetella parapertussis, U04949; Bordetella pertussis, AF142327; Bordetella hinzii, AF177667; Bordetella avium, AF177666; Achromobacter xylosoxidans, AF225979; and Achromobacter denitrificans, AF232712.

(iii) γ-Proteobacteria.

Alteromonas macleodii, X82145; Pseudomonas doudoroffii, AB021371; E. coli, J01859; Vibrio mytili, X99761; Acinetobacter junii, X81658; Acinetobacter anitratus, U10874; Moraxella lacunata, AF005171; Psychrobacter immobilis, U39399; Psychrobacter glacincola, PGU85876; Psychrobacter pacificensis, AB016059; Neptunomonas napthovorans, AF053734; Marinobacterium georgiense, U58339; Pseudomonas stanieri, X92176; Marinomonas vaga, X67025; Marinomonas protea, AJ238597; Pseudomonas fluorescens, AF228367; Pseudomonas fulva, D84015; Pseudomonas stutzeri, AJ288148; Pseudomonas aeruginosa, AF237678; and Pseudomonas putida, U70977.

Phospholipid analysis.

Certain microbes were also identified by phospholipid fatty acid analysis using the MIDI microbial identification system (Newark, Del.) (40).

RESULTS

Metabolism of DMSP and its metabolites.

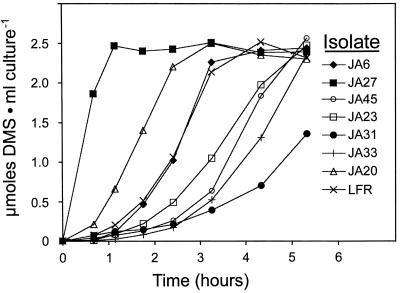

Several hundred colonies that grew rapidly on DMSP-containing plates were isolated from estuarine water samples and DMSP enrichment cultures inoculated with salt marsh surface sediment. All were capable of DMS cleavage from DMSP. Twenty-five isolates were chosen from this group based on their differences in colony morphology; all proved to be aerobic, gram-negative rods. The initial kinetics of DMS production from DMSP showed considerable variability among the isolates in carrying out this reaction (Fig. 1). The DMSP added at time zero served as both the inducer of the DMSP lyase and its substrate, and variability among the isolates is seen in both DMSP-dependent processes. One of the isolates (JA27) was able to metabolize DMSP to DMS with no apparent lag period, suggesting that the DMSP lyase might be constitutively expressed, a characteristic never before seen in DMSP utilizers.

FIG. 1.

Kinetics of DMS production from DMSP by cell suspensions of marine bacteria. Isolates were cultured in marine or tryptic soy broth; 1 ml was harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in half-strength seawater containing DMSP. All cultures tested were fully developed in 24 h on this rich medium and contained approximately the same amount of protein (0.3 mg · ml−1). The headspace analyzed for DMS by gas chromatography. The experiment was performed twice (two replicas), and the average values were used for constructing the graph.

DMSP and its degradation products DMS, acrylate, β-HP, MMPA, and MPA, and a DMSP analog, GBT, are all potentially important carbon and energy sources for marine bacteria, and as such the DMS-producing isolates were tested for their ability to grow on these molecules (Table 2). DMSP served as a growth substrate for all isolates; however, acrylate, a product of DMS cleavage, served as a growth substrate for some but not all. MMPA and MPA, the products of DMSP demethylation (45), were all ineffective as was DMS (data not shown). The metabolism of acrylate to β-HP and the utilization of the latter as a carbon and energy source was observed in two DMS producers, A. faecalis M3A (3) and strain LFR (J. H. Ansede, P. J. Pellechia, and D. C. Yoch, unpublished data). When β-HP was tested as a growth substrate for the isolates, the pattern was identical only among the α-proteobacteria to that of its precursor, acrylate (Table 2). GBT, an abundant quaternary ammonium compound found among DMSP-producing marine algae and plants and an important carbon and energy source for marine bacteria (29), supported growth of most of the DMS-producing isolates. Among the phylotypes, the α-proteobacteria were the most versatile in using these substrates for growth. None of these isolates grew on DMS, nor did they degrade it, as it did not disappear from the gas phase once produced by the action of DMSP lyase (Fig. 1). One isolate (JA25), although isolated on a DMSP plate, could not subsequently be cultured on DMSP in liquid medium and did not produce DMS from DMSP. It did, however, produce methanethiol from DMSP. Although an α-proteobacterium, it was not closely related to the DMS producers (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Growth of DMS-producing isolates on DMSP, acrylate, β-HP, and GBTa

| Strain | Growth on carbon sourceb:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSP | Acrylate | β-HP | GBT | |

| α-Proteobacteria | ||||

| LFR | + | + | + | ± |

| JA6 | + | + | + | + |

| JA13 | + | + | + | + |

| JA19 | + | + | + | + |

| JA20 | + | + | + | + |

| β-Proteobacteria | ||||

| A. faecalis strain M3A | + | + | + | − |

| γ-Proteobacteria | ||||

| P. doudoroffii | + | − | − | + |

| JA1 | + | − | − | + |

| JA3 | + | − | − | + |

| JA9 | + | + | − | + |

| JA11 | + | − | − | + |

| JA14 | + | − | − | + |

| JA16 | + | ± | + | − |

| JA17 | + | − | + | − |

| JA22 | + | − | − | + |

| JA23 | + | + | + | + |

| JA27 | + | − | − | − |

| JA29 | + | − | − | + |

| JA30 | + | − | − | + |

| JA31 | + | − | + | − |

| JA32 | + | + | − | + |

| JA33 | + | − | − | + |

| JA34 | + | + | + | + |

| JA35 | + | − | − | + |

| JA41 | + | − | − | + |

| JA42 | + | − | − | + |

| JA45 | + | − | + | − |

All growth tests were performed at least twice with three replicas each; controls were minimal media without a carbon source.

+, growth on the substrate indicated; −, no growth; ±, a turbidity about twice that of the freshly inoculated value. Not shown are the results of growth on MMPA, MPA, and DMS, none of which served as a substrate. All substrates were provided at 5 mM.

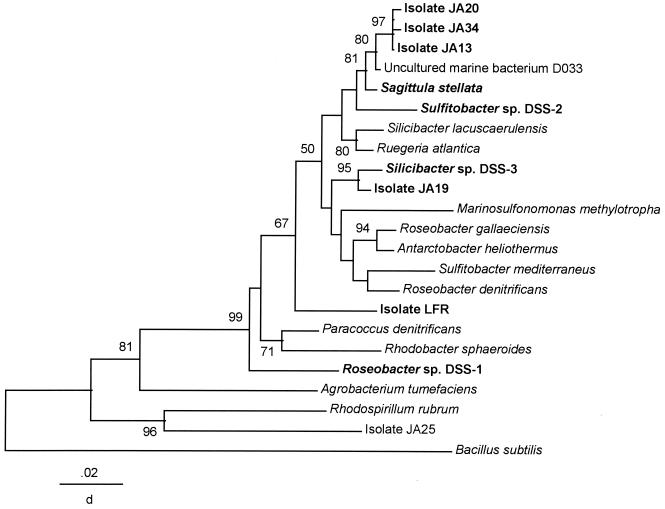

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on the partial 16S rRNA gene sequence showing the relationship among the DMS-producing isolates belonging to the α subdivision of the Proteobacteria. The tree was constructed using Jukes-Cantor distance, and the method was neighbor-joining (39). B. subtilis was used as the outgroup, and bootstrap values greater than 50% (indicated near the branch points) based on 500 pseudoreplicas were generated to establish confidence in the clustering (16). The distance scale is the corrected proportion of the nucleotide changes. All the DMS-producing strains are in bold print; those designated “JA” are from this study.

The isolates were also characterized for their ability to volatilize organosulfur compounds found in marine environments (Table 3). Many were able to reduce DMSO to DMS (probably via DMSO reductase activity) and metabolize methionine to methanethiol. None of the DMS-producing isolates were able to metabolize MMPA to MPA or methanethiol, or MPA to hydrogen sulfide. Dimethylsulfonioacetate, a DMSP analog, was ineffective as a substrate for DMS volatilization (data not shown), and dimethyl disulfide and methanethiol were not degraded by any of the isolates (data not shown). These results must be viewed with caution because of the high concentrations tested.

TABLE 3.

Volatilization and transformation of organosulfur compounds by DMS-producing isolates

| Strain | DMS production fromab:

|

CH3SH production fromac:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSP | DMSO | Methionine | MMPA | |

| α-Proteobacteria | ||||

| LFR | + | + | − | − |

| JA6 | + | + | − | − |

| JA13 | + | + | + | − |

| JA19 | + | + | + | − |

| JA20 | + | + | + | − |

| β-Proteobacteria | ||||

| A. faecalis M3A | + | ± | + | − |

| γ-Proteobacteria | ||||

| P. doudoroffii | + | ± | ± | − |

| JA1 | + | + | + | − |

| JA3 | + | + | + | − |

| JA9 | + | − | + | − |

| JA11 | + | + | + | − |

| JA14 | + | ND | ND | − |

| JA16 | + | − | − | − |

| JA17 | + | − | − | − |

| JA22 | + | ND | ND | − |

| JA27 | + | − | + | − |

| JA29 | + | − | − | − |

| JA30 | + | − | − | − |

| JA31 | + | − | − | − |

| JA32 | + | − | − | − |

| JA33 | + | + | + | − |

| JA34 | + | + | + | − |

| JA35 | + | + | ± | − |

| JA41 | + | + | + | − |

| JA42 | + | − | − | − |

| JA45 | + | − | − | − |

+, production; −, no production; ±, less than 25% of the substrate was converted to its product; ND, not determined.

DMSA and DMDS were also tested but none of the isolates were able to degrade them to DMS.

None of the isolates were capable of producing CH3SH from MPA.

Phylogenetic analysis.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences used for phylogenetic analysis of the DMS-producing salt marsh and estuarine isolates were approximately 500 nucleotides in length and spanned the V3 and V5 hypervariable regions of the gene. These sequences were submitted for BLAST analysis (1) and subjected to phylogenetic analyses by using the PAUP program to gain an understanding of their relationship to each other and their phylogenetic positions relative to known sequences. All sequences submitted showed ≥93% similarity to those found in the GenBank database (32), and while some were >99% similar, none were exactly identical to the sequences of cultured organisms or environmental clones in the database. The closest match was isolate JA3, which had a 99.7% partial-sequence similarity to P. putida. Phylogenetic analysis identified all of the DMS-producing isolates as members of the class Proteobacteria, most of which were in the γ subclass.

The phylogenetic tree of the isolates belonging to the α subgroup of the Proteobacteria is presented in Fig. 2. Distance and maximum likelihood analyses of the partial 16S rRNA gene sequences produced similar results. All strains capable of producing DMS, whether from this study (prefaced by “JA”) or the literature, are indicated in bold. All of the DMS-producing α-proteobacterium isolates were in the Roseobacter subgroup of the Rhodobacter group. Isolates JA13, JA20, and JA34 formed a tight cluster that grouped close to another marine DMS producer, Sagitulla stellata (17). Isolate JA6 (not shown on the tree) was placed close to R. sphaeroides and P. denitrificans, showing 96% sequence homology to the latter. Isolate JA25, which did not group near any of the DMS producers, was the strain that did not grow on DMSP or produce DMS but did produce methanethiol from it. This is apparently unusual as all methanethiol producers isolated to date also produce DMS from DMSP (see reference 26).

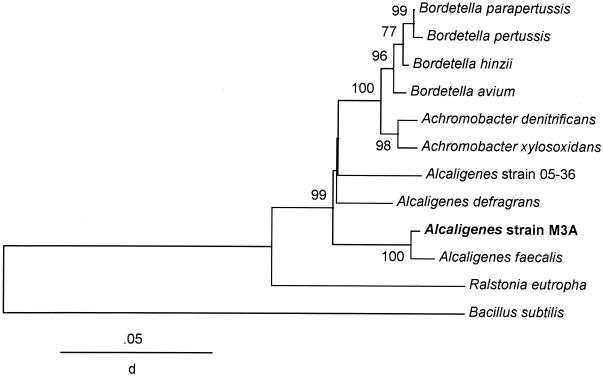

Of all the DMS-producing bacteria isolated over a 5-year period from the salt marsh and estuarine water, only one isolate, Alcaligenes strain M3A, identified by its phenotypic characteristics (11) and phospholipid fatty acid content (data not shown), belonged to the β-proteobacteria. Analysis of 1,536 bp of the 16S rRNA gene indicated more specifically that it was an A. faecalis subspecies having 99.3% sequence similarity to the type strain, ATCC 8750. The type strain, a terrestrial isolate, does not degrade DMSP (data not shown). The phylogenetic tree shows the relationship of strain M3A to its closest β-proteobacterial relatives (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationship of the 16S rRNA gene sequence of A. faecalis strain M3A to other, closely related members of the β subdivision of the Proteobacteria. Methods were as described in the Fig. 2 legend.

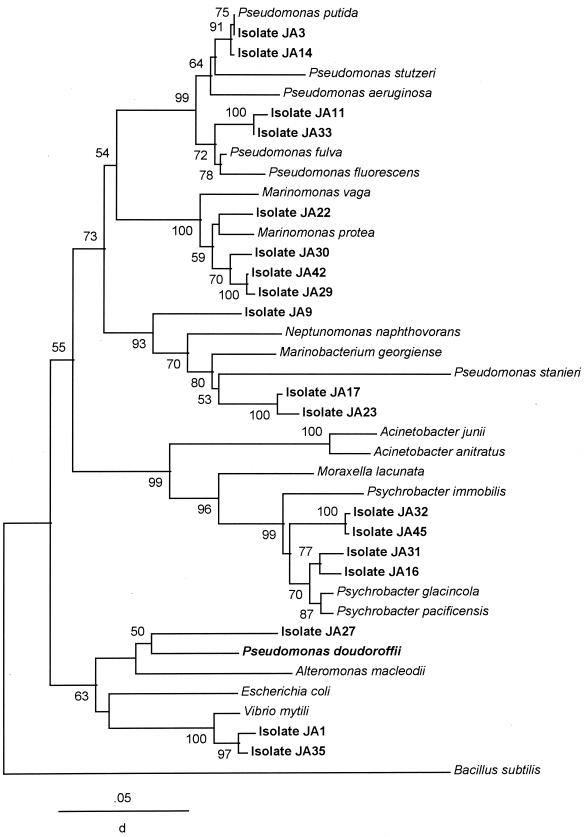

The most abundant group of the salt marsh and estuarine DMS-producing isolates (18 of 24) was affiliated with the γ subdivision of Proteobacteria (see the Fig. 4 tree). They were widely dispersed among various taxa and appeared to group into five clusters, with numerous isolates clustering near the pseudomonads and the genera Marinomonas, Psychrobacter, and Vibrio.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic tree showing relationships of the DMS-producing isolates to representative cultured species of the γ subdivision of the Proteobacteria in the database. The sequence analysis was identical to that described in the legend to Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

Bacteria play an important role in the cycling of sulfur within the marine environment, and the catalysis of DMSP to DMS is an important, well-established part of this cycle. Therefore, knowing the diversity of the population involved is essential to understanding the global sulfur cycle. Prior to this study there were about a dozen DMS-producing isolates whose physiology and phylogeny had been analyzed, most of which were isolated from marine waters. In addition to single isolates belonging to the β, γ, and δ subdivisions of the Proteobacteria, numerous isolates of the α subdivision of the Roseobacter subgroup were obtained from either open ocean or coastal waters which also proved to be DMS producers. The latter observation led to the suggestion that this class of bacteria represented a prominent lineage of DMS producers and “play an important role in the marine sulfur cycle” (17). While α-proteobacteria may also prove to play an important role in the sediments of a Spartina-dominated salt marsh and adjacent estuarine water, the phylogenetic pattern seen here on examining 16S rDNA sequences of DMS producers isolated suggested that γ-proteobacteria may be even more important in this ecosystem. Of the culturable DMS producers deemed to be unique based on phenotypic characteristics, partial 16S rDNA sequence analysis showed that 80% were γ-proteobacteria and <20% were α-proteobacteria (cf. Fig. 2 and 4). Although not quantitative, and no doubt dependent on the isolation technique employed, this study has extended the DMS-producing characteristic into new phylogenetic territory.

The apparent predominance of γ-proteobacterial DMS producers in these North Inlet tidal creeks contrasts with analysis of community DNA of microbes that attach to submerged surfaces in that 85% of the clones sequenced were affiliated with the Roseobacter subgroup of the α-proteobacteria (10). One of those clones, DO33, showed 98% sequence similarity to members of a clade of DMS producers (JA13, JA20, and JA34) isolated from the same tidal creek and adjacent salt marsh, and all were related to another DMS producer, S. stellata E-37 (Fig. 2). A somewhat unrelated isolate, JA19, is closely related to another nearshore DMS producer, Silicibacter sp. strain DSS-3 (17).

The β-proteobacteria are much less common in both estuarine (10) and oceanic water (18, 24, 37, 43), and similar results are reported here. Only one DMS-producing β-proteobacterium, Alcaligenes strain M3A, whose isolation was previously reported (11), was isolated from the salt marsh in numerous samplings of this ecosystem over a number of years. Analysis of full-length 16S rDNA showed strain M3A to be a subspecies of A. faecalis, apparently the first to be isolated from the marine environment. It appears to be quite common on the marsh surface, as microbes of identical phenotypes (25 carbon utilization abilities were assayed) were isolated many times. It is easily recognizable by its diffusable yellow pigment on agar plates, a characteristic not produced by the non-DMS-producing terrestrial A. faecalis strains. The isolated pigment had an absorbance maximum between 390 and 490 nm (data not shown). Not only does the type strain of A. faecalis (ATCC 8750) not have the pigment, it does not metabolize DMSP to DMS, nor could it grow on acrylate or β-HP, products of the DMSP degradation pathway. The isolation of other species of DMS-producing β-proteobacteria may require different isolation techniques.

The majority of the DMS-producing isolates from the marsh whose rDNA was sequenced proved to be γ-proteobacteria (Fig. 4). Several isolates (JA3, JA14, JA11, and JA33) were closely related to cultured pseudomonads. Isolate JA3, in fact, was positively identified as P. putida by both its phospholipid fatty acid composition (data not shown) and its 16S rRNA gene, which showed >99% sequence similarity to that of P. putida. Four isolates (JA42, JA29, JA30, and JA22) form a cluster that is closely related to several Marinomonas species. Two other isolates (JA17 and JA23) did not group closely to other marine bacteria, and therefore it may be of interest to further characterize them. Isolate JA9 was found closest to N. napthovorans on the tree. Several of the DMS-producing isolates (JA31, JA32, JA45, and JA16) were found to cluster among a group of psychrophilic bacteria, showing 97 to 98% sequence similarity to P. pacificensis, a deep seawater isolate from the Japan Trench (34). Two other isolates, JA1 and JA35, were closely related to the marine vibrio V. mytili. The sequence differences between these two isolates are due mostly to transitions, which suggests that they could be more closely related than the tree indicates. Finally, isolate JA27, which shows no apparent lag prior to producing DMS from added DMSP, is related to the marine DMS-producing bacterium P. doudoroffii.

The salt marsh and estuarine isolates were characterized as to their ability to metabolize various organosulfur compounds and DMSP degradation products that occur as sulfur cycle intermediates in the marine environment. Anoxic salt marsh sediments amended with dl-methionine were previously shown to yield methanethiol as the major, volatile organosulfur product (28). Many of the aerobic isolates from this study that produce DMS from DMSP also metabolized methionine to methanethiol. Presumably both methionine and DMSP are released into the sediment pore water and water column during periods of phytoplankton senescence and therefore would serve as both a carbon and energy source for the bacterial community.

An alternative route of DMSP metabolism is its demethylation to MMPA, which may then be subsequently degraded to MPA or methanethiol (27, 44, 51). This demethylation mechanism has been observed in both oxic and anoxic marine sediments and in a number of DMS-producing α-proteobacterium isolates (17). Interestingly, out of the several hundred DMS-producing isolates obtained from salt marshes and tidal creeks in this study, only one demethylating strain was isolated. Since DMSP demethylating strains apparently dominate in the marine environment, the isolation of mostly DMS producers reported here can be explained only if they grew more rapidly (24 to 48 h) on 1 mM DMSP agar plates. These results are, however, consistent with a report by Taylor and Gilchrist (44) who found that “enrichments with DMSP selected for bacteria that generated DMS, whereas MMPA enrichments selected organisms that produced methanethiol.”

None of the DMS-producing isolates were able to metabolize DMSP to MMPA or MPA, as all the DMSP-sulfur could be accounted for as DMS (Fig. 2 and similar data not shown), nor did any produce DMS and methanethiol concomitantly from DMSP. The latter characteristic was reported for several α-proteobacterium isolates (26). One isolate, JA19, that might have been expected to have demethylation activity did not, even though it showed 98% sequence similarity to Silicibacter sp. strain DSS-3, its nearest relative in the database, which has both lyase and demethylase activities (17).

The uptake of acrylate and β-HP seems to be phylotype related in that all α- and β-proteobacterium isolates were able to grow on DMSP, acrylate, and β-HP (Table 2). This correlates with the fact that representatives of these phylogenetic groups degrade DMSP or acrylate to β-HP on the cell surface and transport it into the cell (3, 54; Ansede, Pellechia, and Yoch, unpublished). The phenomenon of some isolates growing on DMSP but not on acrylate or β-HP may be explained if the concentration provided was inhibitory, which may also explain the lack of growth of numerous marine α-proteobacteria on 5 mM acrylate (17). P. doudoroffii and isolates that resemble it may not be able to grow on acrylate or β-HP simply because they cannot transport it. P. doudoroffii transports DMSP into the cytosol where it is degraded to acrylate and DMS (54) and therefore may not have a need to transport the DMSP degradation products.

While the substrate utilization patterns reported here appear to have some relation to the phylogeny of the isolates, this pattern apparently does not hold up when the results from other studies are examined. For example, most the DMS-producing α-proteobacterium isolates of Gonzalez and Moran (19) did not grow on 5 mM acrylate (17, 26), unlike those reported here (Table 2).

To date, studies performed with natural populations of DMS producers have focused on culture-based techniques that may or may not reveal the extent of their actual diversity. However, it is recognized that culture-independent methods are needed to assess DMS-producing assemblages in their natural habitat. Unfortunately, at this time there are no probes available to identify the community involved in DMS production. Primers specific to conserved regions of the 16S rRNA genes that target only sulfate reducers, for example, have been developed and used for analyzing natural assemblages. However, DMS producers are widely dispersed among the Proteobacteria as shown here, and more recently were even found among the gram-positive bacteria (D. C. Yoch and R. N. Hardee, unpublished data). Therefore the development of primers to specifically target the 16S rRNA gene of DMS producers seems unlikely. Attempts are under way to clone the DMSP lyase gene so that a functional probe may be constructed. Such a probe could be used in identifying DMS-producing bacteria from natural populations, thereby eliminating the culture-based bias when accessing the diversity of the DMS-producing assemblage. Despite the limitations of using cultured bacteria to access their abundance in the natural environment, this study has nonetheless added to the accumulating knowledge of the diversity of the DMS-producing bacteria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Travis Glenn for his help and advice with the DNA sequencing and introduction to phylogenetic analysis of 16S rDNA.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreae M O. The ocean as a source of atmospheric sulfur compounds. In: Buat-Menard P, editor. The role of air-sea exchange in geochemical cycling. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Reidel Publishing Co.; 1986. pp. 331–362. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ansede J H, Pellechia P J, Yoch D C. Metabolism of acrylate to β-hydroxypropionate and its role in dimethylsulfoniopropionate lyase induction by a salt marsh sediment bacterium, Alcaligenes faecalis M3A. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5075–5081. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.5075-5081.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bacic M K, Yoch D C. In vivo characterization of dimethylsulfoniopropionate lyase in the fungus Fusarium lateritium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:106–111. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.106-111.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birnboim H, Dolly J. A rapid extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1525. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantoni G L, Anderson D G. Enzymatic cleavage of dimethylpropiothetin by Polysiphonia lanosa. J Biol Chem. 1956;222:171–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Challenger F, Simpson M I. Studies on biological methylation. Part XII. A precursor of the dimethyl sulfide evolved by Polysiphonia fastigata. Dimethyl-2-carboxyethyl-sulfonium hydroxide and its salts. J Chem Soc. 1948;3:1591–1597. doi: 10.1039/jr9480001591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dacey J W H, King G M, Wakeham S G. Factors controlling emission of dimethylsulfide from salt marshes. Nature. 1987;330:643–645. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dacey J W H, Wakeham S G. Oceanic dimethyl sulfide: production during zooplankton grazing on phytoplankton. Science. 1986;233:1314–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.233.4770.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dang H, Lovell C R. Bacterial primary colonization and early succession on surfaces in marine waters as determined by amplified rRNA gene restriction analysis and sequence analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:467–475. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.2.467-475.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Souza M P, Yoch D C. Purification and characterization of dimethylsulfoniopropionate lyase from an Alcaligenes-like dimethyl sulfide-producing marine isolate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:21–26. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.21-26.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Souza M P, Yoch D C. N-terminal amino acid sequences and comparison of DMSP lyases from Pseudomonas doudoroffii and Alcaligenes strain M3A. In: Kiene R P, Visscher P T, Keller M D, Kirst G O, editors. Environmental and biological chemistry on dimethylsulfoniopropionate and related sulfonium compounds. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 293–304. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickson D M J, Kirst G O. The role of dimethylsulfoniopropionate, glycine betaine and homarine in the osmoacclimation of Platymonas subcordiformis. Planta. 1986;7:536–543. doi: 10.1007/BF00391230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickson D M J, Kirst G O. Osmotic adjustment in marine eukaryotic algae: the role of inorganic ions, quaternary ammonium, tertiary sulfonium and carbohydrate solutes. II. Prasinophytes and haptophytes. New Phytol. 1987;106:645–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1987.tb00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Don R H, Cox P T, Wainwright B, Baker K, Mattick J S. “Touchdown” PCR to circumvent spurious priming during gene amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4008. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.González J M, Kiene R P, Moran M A. Transformation of sulfur compounds by an abundant lineage of marine bacteria in the α-subclass of the class Proteobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3810–3819. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.9.3810-3819.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.González J M, Whitman W B, Hodson R E, Moran M A. Identifying numerically abundant culturable bacteria from complex communities: an example from a lignin enrichment culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4433–4440. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4433-4440.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.González J M, Moran M A. Numerical dominance of a group of marine bacteria in the α-subclass of the class Proteobacteria in coastal seawater. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4237–4242. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4237-4242.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillard R R L. Culture of phytoplankton for feeding marine invertebrates. In: Smith W L, Chanley M H, editors. Culture of marine invertebrate animals. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1975. pp. 29–60. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonkers H M, de Bruin S, van Gemerden H. Turnover of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) by the purple sulfur bacterium Thiocapsa roseopersicina M11: ecological implications. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;27:281–290. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadota H, Ishida Y. Production of volatile sulfur compounds by microorganisms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1972;26:127–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.26.100172.001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keller M D, Bellows W K, Guillard R R L. Dimethylsulfide production in marine phytoplankton. In: Salzman E S, Cooper W J, editors. Biogenic sulfur in the environment. American Chemical Society Symposium Series no. 393. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society; 1989. pp. 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerkhof L J, Voytek M A, Sherrell R M, Millie D, Schofield O. Variability in bacterial community structure during upwelling in the coastal ocean. Hydrobiologia. 1999;401:139–148. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiene R P. Dimethyl sulfide production from dimethylsulfoniopropionate in coastal seawater samples and bacterial cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3292–3297. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.11.3292-3297.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiene R P, Linn L J, Gonzalez J, Moran M A, Bruton J A. Dimethylsulfoniopropionate and methanethiol are important precursors of methionine and protein-sulfur in marine bacterioplankton. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4549–4558. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4549-4558.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiene R P, Taylor B F. Demethylation of dimethylsulfoniopropionate and production of thiols in anoxic marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2208–2212. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.9.2208-2212.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiene R P, Visscher P T. Production and fate of methylated sulfur compounds from methionine and dimethylsulfoniopropionate in anoxic salt marsh sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2426–2434. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.10.2426-2434.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King G M. Distribution and metabolism of quaternary amines in marine sediment. In: Blackburn T H, Sorensen J, editors. Nitrogen cycling in coastal marine environments. New York, N.Y: John Wiley; 1988. pp. 143–173. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ledyard K M, Dacey J W H. Microbial cycling of DMSP and DMS in coastal and oligotrophic seawater. Limnol Oceanogr. 1996;41:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ledyard K M, DeLong E F, Dacey J W H. Characterization of a DMSP-degrading bacterial isolate from the Sargasso Sea. Arch Microbiol. 1993;160:312–318. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maidak B L, Cole J R, Parker C T, Jr, Garrity G M, Larsen N, Li B, Lilburn T G, McCaughey M J, Olsen G J, Overbeek R, Pramanik S, Schmidt T M, Tiedje J M, Woese C R. A new version of the RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:171–173. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marmur J. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from microorganisms. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maruyama A, Honda D, Yamamoto H, Kitamura K, Higashihara T. Phylogenetic analysis of psychrophilic bacteria isolated from the Japan Trench, including a description of the deep-sea species Psychrobacter pacificensis sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:835–846. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-2-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matrai P, Keller M D. DMS in a large scale coccolithophore bloom in the Gulf of Maine. Cont Shelf Res. 1993;13:831–843. [Google Scholar]

- 35a.Neefs J-M, Van de Peer Y, Hendriks L, De Wachter R. Complication of small ribosomal subunit RNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:2237–2317. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.suppl.2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pace N R. New perspective on the natural microbial world: molecular microbial ecology. ASM News. 1996;62:463–470. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rath J, Wu K Y, Herndl G J, DeLong E F. High phylogenetic diversity in a marine-snow-associated bacterial assemblage. Aquat Microb Ecol. 1998;14:261–269. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reed R H. Measurement and osmotic significance of β-dimethylsulfoniopropionate in marine macroalgae. Mar Biol Lett. 1983;4:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–424. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sasser M. Identification of bacteria by gas chromatography of cellular fatty acids. MIDI Technical Notes 101–102. Newark, Del: Microbial ID Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stefels J, van Boekel W H M. Production of DMS from dissolved DMSP in axenic cultures of the marine phytoplankton species Phaeocystis sp. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1993;97:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steudler P A, Peterson B J. Contribution of gaseous sulfur from salt marshes to the global sulfur cycle. Science. 1984;311:455–457. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki M T, Rappe M S, Haimberger Z W, Winfield H, Adair N, Ströbel J, Giovannoni S J. Bacterial diversity among small-subunit rRNA gene clones and cellular isolates from the same seawater sample. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:983–989. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.983-989.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor B F, Gilchrist D C. New routes for aerobic biodegradation of dimethylsulfoniopropionate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3581–3584. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.12.3581-3584.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor B F, Visscher P T. Metabolic pathways involved in DMSP degradation. In: Kiene R P, Visscher P T, Keller M D, Kirst G O, editors. Environmental and biological chemistry on dimethylsulfoniopropionate and related sulfonium compounds. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalities and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vairavamurthy A, Andreae M O, Iversen R L. Biosynthesis of dimethyl sulfide and dimethyl propiothetin by Hymenomonas carterae in relation to sulfur source and salinity variations. Limnol Oceanogr. 1985;30:59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Maarel M J E C, Aukema W, Hansen T A. Purification and characterization of a dimethylsulfoniopropionate cleaving enzyme from Desulfovibrio acrylicus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;143:241–245. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Visscher P T, Diaz M R, Taylor B F. Enumeration of bacteria which cleave or demethylate dimethylsulfoniopropionate in the Caribbean Sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1992;89:293–296. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Visscher P T, van Gemerden H. Production and consumption of dimethylsulfoniopropionate in marine microbial mats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3237–3242. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.11.3237-3242.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Visscher P T, Taylor B F. Demethylation of dimethylsulfoniopropionate to 3-mercaptopropionate by an aerobic marine bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4617–4619. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4617-4619.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wagner C, Stadtman E R. Bacterial fermentation of dimethyl-β-propiothetin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1962;98:331–336. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(62)90191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolfe G V, Sherr E B, Sherr B F. Release and consumption of DMSP from Emliana huxleyi during grazing by Oxyrrhis marina. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1994;111:111–119. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoch D C, Ansede J H, Rabinowitz K S. Evidence for intracellular and extracellular dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) lyases and DMSP uptake sites in two species of marine bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3182–3188. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3182-3188.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]