Abstract

Background

Research in sarcomas has historically been the domain of scientists and clinicians attempting to understand the disease to develop effective treatments. This traditional approach of placing scientific rigor before the patient’s reality is changing. This evolution is reflected in the growth of patient-centered organizations and patient advocacy groups that seek to meaningfully integrate patients into the research process. The aims of this study are to identify the unanswered questions regarding sarcomas (including gastrointestinal stromal tumors and desmoid fibromatosis) from patient, carer, and clinical perspectives and examine how patients and carers want to be involved in sarcoma research.

Methods

The Patient-Powered Research Network of Sarcoma Patients EuroNet set up a Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) in collaboration with stakeholders from the sarcoma research field. This PSP is largely based on the James Lind Alliance methodology.

Results

In total, 264 sarcoma patients (73%) and carers (27%) from all over the world participated in the online survey and covered the full spectrum of sarcomas. The topics mentioned were labeled in accordance with the Common Scientific Outline of the International Cancer Research Partnership and lists for potential research topics, advocacy topics, and requests for information were constructed. With regard to patient and carer involvement, 64% were very willing to be actively involved and mainly in the following areas: sharing perspectives, discussing patient-clinician interactions, and attending research meetings.

Conclusions

The first results of this sarcoma PSP identified important research questions, but also important topics for patient advocacy groups and further improvement of information materials. Sarcoma patients and carers have a strong wish to be involved in multiple aspects of sarcoma research. The next phase will identify the top 10 research priorities per tumor type. These priorities will provide guidance for research that will achieve greatest value and impact.

Key words: sarcoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, desmoid fibromatosis, priority setting partnership, patient involvement, patient advocacy

Highlights

-

•

The results from this international sarcoma Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) identified important research questions.

-

•

This PSP also identified important topics for patient advocacy and requests for information.

-

•

Sarcoma patients and carers have a strong wish to be involved in multiple aspects of sarcoma research.

-

•

The next phase of this PSP will aim to prioritize the research questions per tumor type.

Introduction

Sarcomas are malignancies originating from mesenchymal cells and encompass more than 70 different histological subtypes.1 With a total incidence of 5.6 per 100 000 per year in Europe they account for ∼1% of all adult malignancies.2 Sarcomas affect people of all ages and can occur at any anatomical site. A broad histological distinction can be made between bone sarcomas (BS) and soft tissue sarcomas (STS), with a 5-year survival rate of 50%-55% and 55%-65%, respectively.3, 4, 5

Tumors from mesenchymal origin closely linked to STS, however, often regarded separately in the context of research, are gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and desmoid fibromatosis (DF). GISTs are the most common mesenchymal malignancies6 and DF is a borderline mesenchymal tumor, lacking the ability to metastasize.7 Research in sarcoma, GIST, and DF aims at understanding the disease in an effort to develop effective treatments.

Setting the agenda in sarcoma research has historically been the domain of researchers and clinicians. This traditional approach of placing scientific rigor before the patient’s reality, however, is changing. This evolution is reflected in the growth of patient-centered organizations and patient advocacy groups that seek to meaningfully integrate patients into the process of prioritizing research needs.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 An example of such a patient-centered organization in the field of sarcomas is the Sarcoma Patients EuroNet Association (SPAEN). SPAEN is an international network of national sarcoma, GIST, and DF patient advocacy groups with the aim of extending patient support and advocacy to patient organizations for the benefit of sarcoma patients globally.

The management and decision making in health care is taking increasing regard to the input of patients and patient advocacy groups through consultation methods, the development of patient-reported outcomes and patient experience measures, and bringing patients into research projects to provide their ‘lived experience’.

The need for patient involvement in scientific research is emphasized by the reported mismatch between what patients, clinicians, and researchers would want to see researched, and what is actually being researched. Tallon et al.16 described this mismatch in osteoarthritis patients where patients and doctors did not favor drug trials, yet most of the published studies on this disease were drug trials. Crowe et al.17 confirmed these results and also found that researchers generally preferred drug trials, whereas clinicians, patients, and carers preferred non-drug trials.

In an effort to bridge this mismatch, the James Lind Alliance (JLA) was founded to open up the discussion between patients and clinicians to agree on priorities for future research.18 Through Priority Setting Partnerships (PSPs), the JLA brings together clinicians, patients, and carers to identify and prioritize evidence uncertainties in particular areas of health and care that could be answered by research.19

Patient-centered care in sarcomas cannot be practiced without patients participating in their own health care decisions and in the research that informs such decisions. With this in mind, the Patient-Powered Research Network (PPRN) of SPAEN set up a PSP. This study reports on the first phase and aims to identify unanswered questions regarding sarcomas (including GIST and DF) from a patient, carer, and clinical perspective. Additionally, this study aims to examine how patients and carers want to be involved in sarcoma research.

Methods

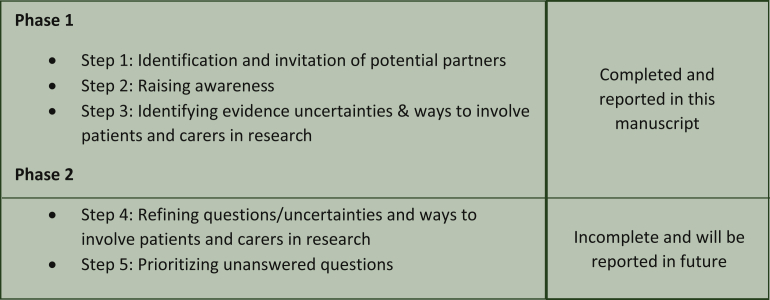

The PPRN of SPAEN set up a PSP in collaboration with several stakeholders in the sarcoma research field. The JLA methodology was tailored to best meet the aims of this PSP, which is the first activity of the PPRN. It consists of five steps divided in two phases (Figure 1). This manuscript reports only on phase 1 of the PSP.

Figure 1.

Methodology of this Priority Setting Partnership. The James Lind Alliance methodology was tailored to best fit the aims of this Priority Setting Partnership.

Step 1: Identification and invitation of potential partners

Steering group

First, a steering group was established to oversee the project and determine the scope and objectives. The steering group consisted of patients, and carers, clinicians, and researchers. Researchers were included to advise on the shaping of research questions; however, they did not participate in the prioritization exercise.

Objectives

The objectives of this sarcoma PSP are to:

-

•

Work with patients, carers, clinicians, and industry professionals to identify uncertainties concerning sarcomas and agree by consensus a prioritized list of those uncertainties.

-

•

Work with patients, carers, clinicians, and industry professionals to identify ways to involve patients and carers in research and agree by consensus the best way to involve patients and carers in research.

-

•

Publish the results and process of this PSP.

-

•

Take the results to research commissioning bodies to be considered for funding.

The scope

The scope of this PSP is all sarcoma, GIST, and DF patients, carers, clinicians, and industry professionals aged 16 years and older. The PSP will exclude children (<16 years old) from its scope.

Partners

Potential partner organizations were identified through a process of consultation via the Steering Group members’ networks. Potential partners were organizations representing the following groups: (i) people who have (had) sarcoma; (ii) carers of people who have (had) sarcoma; (iii) health/social care professionals with experience in sarcomas; and (iv) industry professionals with experience in sarcomas. Potential partners were contacted and informed of the establishment and aims of the sarcoma PSP.

Step 2: Raising awareness

SPAEN utilized its network and communication channels to reach patients, carers, clinicians, and industry professionals. The partners identified in step 1 were requested to employ their networks in the same way.

Step 3: Identifying evidence uncertainties and ways to involve patients and carers in research

Identifying unanswered research questions and ways to engage patients and carers in research was conducted through a sarcoma research PSP questionnaire. Sarcoma patients, carers, health care professionals, industry professionals, and researchers were able to take part. The questionnaires were distributed though digital media (SPAEN website and social media channels) and via snowball sampling of local national patient associations. In the Netherlands, an additional strategy was used, in which participants of a currently ongoing study were invited to complete the questionnaire.20

Questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of three sections. The first section assessed what questions on sarcomas participants would like to see answered by research. The six open questions assessed that on the areas of: (i) diagnosis; (ii) treatment; (iii) support; (iv) health-related quality of life; (v) survivorship; and (vi) end-of-life issues. The second section concerned questions on the involvement of patients and carers in research. The first five multiple choice questions inquired about past involvement of patients/carers in sarcoma research; wishes to be involved; and whether it was deemed useful to be involved. The three open questions asked where patients/carers could impact research; why they do or do not take part in research; and what could help them become more involved. The third sections assessed personal information and the participants’ connection with sarcoma.

Analysis

Members of the steering group and stakeholders (OH, CD, PvK, CK, and GvO) conducted the analysis of the first section of the questionnaire. Topics mentioned by respondents were labeled in accordance with the Common Scientific Outline (CSO) of the International Cancer Research Partnership (icpartnership.org/cso). A subset of the data was labeled by more than one team member to make sure that the classification was carried out consistently. Next, similar topics were combined and for every CSO category, a list was formed. It became clear that some topics on that list were not potential subjects for research (R), but rather topics that require advocacy action (A) or topics that are more requests for information (I); these were labeled accordingly.

Results

Respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics

In total, 264 individuals filled out the questionnaire (Table 1). Of all respondents, 194 (74%) were sarcoma patients; 51 (20%) were carers/partners/relatives of sarcoma patients; 11 (4%) were bereaved carers/partners/relatives of sarcoma patients (n = 11); 3 (1%) were sarcoma health care professionals, and 3 (1%) were organizations representing the interests of sarcoma patients. Most respondents were female (70%) and the median age was 53 years (range 19-82 years). The country of residence/work was the Netherlands for most respondents (20%), followed by respondents from Germany (19%), and the UK (17%). Most sarcoma patients who responded live independently at home (82%), whereas 15% live at home supported by family or carers, with their parents (2%), or in a nursing home (1%).

Table 1.

Respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics

| Sociodemographic characteristics | All respondents N = 264 (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 76 (29.2) |

| Female | 183 (70.4) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.4) |

| Missing | 4 (1.5) |

| Age (years) | |

| Median (range) | 53 (19-82) |

| Respondents’ connection with sarcoma | |

| Sarcoma patient | 194 (74.1) |

| Carer/partner/relative of sarcoma patient | 51 (19.5) |

| Bereaved carer/partner/relative of sarcoma patient | 11 (4.2) |

| Health care professional treating sarcoma patients | 3 (1.1) |

| Organization representing interests of sarcoma patients | 3 (1.1) |

| Missing | 2 (0.76) |

| Ethnic origin | |

| White Caucasian | 231 (89.2) |

| Asian | 3 (1.2) |

| Mix/other | 12 (4.6) |

| Prefer not to say | 13 (5.0) |

| Missing | 5 (1.9) |

| Educational level | |

| No education/primary school | 4 (1.5) |

| Secondary school | 23 (8.7) |

| Vocational education | 33 (12.5) |

| College/diploma | 75 (28.5) |

| University/degree | 109 (41.4) |

| Prefer not to say | 4 (1.5) |

| Other | 15 (5.7) |

| Missing | 1 (0.4) |

| Country of residence/work | |

| Netherlands | 52 (19.7) |

| Germany | 51 (19.3) |

| UK | 44 (16.7) |

| Spain | 25 (9.5) |

| Italy | 23 (8.7) |

| USA | 23 (8.7) |

| France | 19 (7.2) |

| Othera | 24 (9.2) |

| Prefer not to say | 3 (1.1) |

| Sarcoma patients N = 194 (%) |

|

|---|---|

| Current living arrangement of sarcoma patients | |

| Own home (independently) | 155 (79.9) |

| Own home (supported by family/carer) | 29 (14.9) |

| Living with parents | 4 (2.1) |

| Nursing home | 1 (0.5) |

| Missing | 5 (2.6) |

Ireland, Belgium, Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden, Austria, Finland, Australia, India, Brazil, Argentine, Chile and Canada.

Tumor characteristics

Table 2 presents the tumor characteristics of both the sarcomas of the respondents and the sarcomas of the people the respondents care(d) for. The majority were diagnosed with STS (49%), followed by GIST (29%), BS (13%), and DF (8%). Localization of the tumor was most frequently seen intra-abdominally (34%). Most respondents [or the person the respondent care(s/d) for] presented with localized disease (68%) and were treated in a curative setting (44%). The median time a patient was living with sarcoma at the time of the study was 4 years (range 0-38 years).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the sarcoma the respondent [or person the respondent care (s/d) for] was diagnosed with

| Disease characteristics | All respondents N = 264 (%) |

|---|---|

| What was the type of tumor you [or the person you care(d) for] were diagnosed with? | |

| Bone sarcoma | 31 (12.6) |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 120 (48.8) |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | 71 (28.9) |

| Desmoid fibromatosis | 20 (8.1) |

| Prefer not to say | 4 (1.6) |

| Missing | 18 (6.8) |

| What was the location of the sarcoma you [or the person you care(d) for] were diagnosed with? | |

| Upper extremity | 16 (6.2) |

| Lower extremity | 61 (23.7) |

| Head/neck/scalp | 11 (4.3) |

| Retroperitoneal | 14 (5.4) |

| Heart/vascular | 4 (1.6) |

| Lung | 3 (1.2) |

| Gynecological | 24 (9.3) |

| Intra-abdominal | 87 (33.9) |

| Thorax | 28 (10.9) |

| Other | 5 (1.9) |

| Prefer not to say | 4 (1.6) |

| Missing | 7 (2.7) |

| What was the stage of the disease you [or the person you care(d) for] were diagnosed with? | |

| Localized | 174 (67.5) |

| Metastatic | 62 (24.0) |

| I don’t know | 15 (5.8) |

| Prefer not to say | 7 (2.7) |

| Missing | 6 (2.3) |

| What was the intention of the treatment you [or the person you care (d) for] had or are currently receiving? | |

| Curative | 107 (43.8) |

| Palliative | 57 (23.4) |

| Symptom control only | 32 (13.1) |

| I don’t know | 26 (10.7) |

| Prefer not to say | 22 (9.0) |

| Missing | 20 (7.6) |

| How long are you (or is the person with sarcoma) living with sarcoma? | |

| Median (range) | 4 Years (0-38) |

Patient and carer involvement in research

Of all respondents, 34% had been asked to take part in sarcoma research in the past as a participant and 27% had in fact participated in sarcoma research. Thirty respondents (11%) do not want to be involved in sarcoma research. Almost all respondents strongly agree (67%) or agree (26%) that patients and carers can contribute meaningfully to the research process. How the respondents think patients and carers can contribute best to the research process is presented in Table 3. Of the multiple options given, respondents indicated most often that they think patients and carers can contribute to the research process by ‘sharing the perspective and experience of living with and beyond sarcoma or experiences with care’ (15%); ‘discussing aspects of patient-clinician interactions’ (11%), and ‘attending meetings to learn about study updates and progress’ (10%).

Table 3.

Patient and carer involvement in sarcoma research

| All respondents N = 264 (%) |

|

|---|---|

| Have you ever been asked to take part in sarcoma research? | |

| Yes, as a participant | 89 (34.1) |

| Yes, as a researcher | 7 (2.7) |

| No | 163 (62.5) |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (0.7) |

| Missing | 5 (1.9) |

| Have you ever been involved in sarcoma research? |

|

| Yes, as a participant | 71 (27.4) |

| Yes, as a researcher | 7 (2.7) |

| No | 181 (69.9) |

| Missing | 5 (1.9) |

| Do you want to be involved in sarcoma research? | |

| Yes, as a participant | 176 (66.4) |

| Yes, as a researcher | 34 (12.8) |

| No | 30 (11.3) |

| Prefer not to say | 25 (9.5) |

| Missing | 18 (6.8) |

| Patients/carers can contribute meaningfully to the research process | |

| Strongly agree | 176 (67.4) |

| Agree | 69 (26.4) |

| Disagree | 2 (0.8) |

| Undecided | 14 (5.4) |

| Missing | 3 (1.1) |

| How do you think patients/carers can contribute to the research process? | N = 264 (%)a |

|---|---|

| Share perspective and experience of living with and beyond sarcoma or experiences with care | 220 (83.7) |

| Discuss aspects of patient-clinician interactions | 167 (63.5) |

| Attend meetings to learn about study updates and progress | 150 (57.0) |

| Identify research topics | 137 (52.1) |

| Participate as advisors on multi-stakeholder advisory councils | 127 (48.3) |

| Create and refine patient-facing study materials | 118 (44.9) |

| Provide input on study design | 113 (43.0) |

| Provide input and guidance on plans for disseminating research findings to a broader community | 99 (37.6) |

| Discuss and troubleshoot challenges arising throughout the study | 99 (37.6) |

| Provide input or feedback on data analysis and findings as interpreted by the research team | 78 (29.7) |

| Provide input on recruitment and retention plans | 55 (20.9) |

| Author/co-author publications | 50 (19.0) |

| Provide input on issues related to data governance and confidentiality | 44 (16.7) |

| Other | 37 (14.1) |

| I don’t know | 14 (5.3) |

| Missing | 1 (0.4) |

263 Respondents (1 missing) provided 1508 answers.

Subjects for research, advocacy, and information requests

The product after the analysis of the respondents’ mentioned topics was a list of 23 subjects for research; 15 subjects for advocacy action; and 17 topics that could be categorized as requests for information (Table 4). The order of all three lists is according to the themes in which the specific subjects for research, advocacy, or requests for information can be placed.

Table 4.

Subjects for research, advocacy, and information

| Subjects for research (R) | |

|---|---|

| 1 | What are causes of sarcoma? |

| 2 | Are preventative measures possible? Can vaccines be developed? |

| 3 | Research into hereditary aspects of sarcoma. |

| 4 |

|

| 5 | Research the effect of personal characteristics: what have survivors in common? |

| 6 | Research better diagnostic techniques (imaging, blood tests, scans, innovative image analysis techniques, whole gene sequencing) and research how to better distinguish between subtypes and benign and malignant tumors. |

| 7 | What percentage of diagnosis is wrong? |

| 8 | What is the risk of taking biopsies? |

| 9 | Research into innovative treatment: immunotherapy, targeted therapy, and combined therapies. |

| 10 | Research more options for treatment; compare their effectiveness (e.g. perfusion versus amputation); and pay more attention to quality of life (balancing of overall survival and quality of life). |

| 11 | Research into methods for precision surgery. What is the effect of surgical margins on prognosis? |

| 12 | Research on effects of lifestyle, diet, mental condition (integrative health care). |

| 13 | Research on all kinds of side-effects (pain, side-effects of TKIs, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, etc.) and treatments thereof. |

| 14 | Research coping strategies for side-effects. |

| 15 | Research long-term effects of treatment on fertility, intimacy. |

| 16 | Research for better estimation of prognosis and risk. |

| 17 | Research personalized, risk-based follow-up schemes. |

| 18 | What is the effect of mental condition on the result of the treatment? |

| 19 | Research on treatment methods (e.g. psychotherapy, mindfulness, psychedelics) for disease-related mental suffering (e.g. acceptance, anxiety). |

| 20 | Research on the re-integration of sarcoma survivors. |

| 21 | How is end-of-life care organized in different countries? |

| 22 | What is happening in the terminal phase (development of the disease and best supportive care)? |

| 23 | Research shared decision making in final phase: what is role of carers? |

| Subjects for advocacy (A) | |

|---|---|

| 1 | The diagnostic process must be improved through better education and development of tools (artificial intelligence) that can assist GPs in recognizing the possibility of a sarcoma. |

| 2 | A better classification is needed for benign and malignant tumors and benign tumors should be included in registries. |

| 3 | Mutational analysis of the tumor should be available for all patients. |

| 4 | Data sharing should be improved; all relevant data of a patient should be available across medical institutions. |

| 5 | An international registry is needed to supply with data for research and stimulate international research collaboration. |

| 6 | International registry for research and the use of big data analysis. |

| 7 | Communication between specialists and patient must be improved to stimulate shared decision making. |

| 8 | A single point of contact must be provided to patients (e.g. case manager, specialized nurse). |

| 9 | Information on all tumor subtypes must be available for patients. |

| 10 | Sarcoma centers should advise patients on complementary treatments, lifestyle, and diet. |

| 11 | Ample attention should be given to quality of life and consequences of treatment (e.g. pain, temporary/permanent effects of surgery, side-effects of medication) during the shared decision-making process. |

| 12 | Mental support must be available for sarcoma patients. |

| 13 | End-of-life scenario should be discussed openly and timely with the patient. |

| 14 | Referral of patients to sarcoma expert centers, centralization, networks. |

| 15 | The availability to patients of off-label or compassionate use medication. |

| Information requests (I) | |

|---|---|

| 1 | What are causes of sarcoma? |

| 2 | What do survivors have in common? |

| 3 | What are symptoms that can alert patients? |

| 4 | Is it possible to screen people for sarcoma? |

| 5 | Can sarcoma be prevented? What have I done myself? |

| 6 | What methods are available for detecting sarcoma? What are differences between diagnostic methods? |

| 7 | Request for information about trials. |

| 8 | Information about treatment options, including success rate, side-effects, quality of life, long-term effects. |

| 9 | What are consequences of the disease and treatment on mental health? |

| 10 | More information on successive treatment options after first-line treatment. |

| 11 | Information about alternative treatment (including integral medicine) in case medical treatment fails. |

| 12 | More information on prognosis. |

| 13 | When can I be considered cured? |

| 14 | Which is the best place for sarcoma treatment? Request for more information about expert centers (also internationally). |

| 15 | Can I be treated in a center abroad? Information about insurance coverage for sarcoma treatment abroad. |

| 16 | Which medical professional is responsible for me? |

| 17 | Information on all aspects of end of life, both for patients and carers. |

GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; GP, general practitioner; TGCT, tenosynovial giant cell tumor; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

The topics mentioned by the respondents as subjects for research are on the theme of the origin of sarcoma (R1-5); diagnostic process (R6-8); treatment (R9-12); side-effects (R13-15); prognosis (R16, R17); quality of life (R18-20); and end of life (R21-23). The themes of the subjects for advocacy action are the diagnostic process (A1-3); collaboration (A4-6); information sharing (A7-11); quality of life (A12); end of life (A13); expert centers (A14); and off-label medication (A15). Requests for information are on the themes of the origin of sarcoma (I1-2); detection and prevention (I3-6); treatment (I7-11); prognosis (I12, I13); organization of care (I14-16); and end of life (I17).

Discussion

This sarcoma PSP has brought together patients, carers, and health care professionals to identify research questions, topics for patient advocacy, and requests for information in the field of sarcoma. The first results of this PSP also showed that patients and carers are eager to participate in various aspects of sarcoma research.

In this PSP, we chose to identify patients’ and carers’ unanswered questions about sarcomas through open questions. The analysis was time- and labor-intensive, as many respondents did not restrict their response to the open questions of the six areas mentioned. Instead, they took the open questions as an invitation to tell their story about the difficulties they experienced during their patient journey. This is positive as it indicates that the questions gave respondents enough room to write down what is important to them. Respondents were asked what questions they would like to see answered by research and it became apparent that it is not always completely clear to respondents what scientific research entails and what questions can be answered by research. During the process of analyzing the results, it became clear that the respondents’ answers were either topics for research, topics for advocacy, or requests for information. Although it would probably yield more uniform answers, it is important not to specifically ask for research questions in a PSP, as it might discourage people who are not familiar with scientific research from responding. Instead, the JLA approach is to simply ask what is important to the respondent. This had a good effect in this PSP and brought forward topics that were not necessarily anticipated, but clearly important to the respondents. In some cases, there was overlap between the three categories. For instance, the question ‘What are causes of sarcoma?’ was mentioned by respondents as a subject for research, as well as a request for information. This means that the respondents want more research into the causes of sarcomas, as well as more information on what is already known about the causes of sarcomas.

Sarcomas are a rare and heterogeneous group of tumors and patients often experience a delay in diagnosis and report that it had cost them much effort to receive the right diagnosis.21,22 Therefore, it is not surprising that several topics for research address the diagnostic process (‘Research better diagnostic techniques’; ‘What percentage of diagnoses is wrong?’). Also, in sarcoma the progress in survival improvement is lagging when compared with other cancer types. Many respondents mentioned the topic of novel methods of treatment (‘Research into innovative treatment: immunotherapy, targeted therapy and combined therapies’). The results also showed that the respondents were very interested in more research on quality of life including side-effects of treatment, long-term effects of treatment, mental and emotional aspects and anxiety [‘Research on treatment methods for disease-related mental suffering (e.g. acceptance, anxiety)’]. Sarcomas are generally aggressive tumors that require intensive treatment with long-term side-effects that negatively impact quality of life in survivors, and it is therefore not surprising that patients and carers would like to see more research in this area. Interestingly, many topics mentioned by the respondents were regarding end of life, and in those questions, the presence of carers among the respondents became apparent (‘Research shared decision making in the final phase: what is the role of carers?’).

With respect to advocacy, the topics mentioned reflect the special needs that are typical for rare cancers such as sarcomas. These include high-quality care in specialized centers and networks (‘Referral of patients to sarcoma expert centers, centralization, networks’) and international collaboration (‘Data sharing should be improved; all relevant data of a patient should be available across medical institutions’). It is noteworthy that the wish from patients is to increase and improve data sharing, whilst the regulations and legislation regarding data sharing are increasing, making exactly that more difficult. For such rare tumors, centralization of both research efforts and care are key to providing patients with the best care. It exposes health care professionals to enough cases to become experienced and studies can be designed that include more patients and gives evidence more power. It is important that sarcoma specialists have a good network nationally and internationally to ask advice from colleagues when needed.

The topics that respondents mentioned as subjects for research were often reflected in the requests for information. For example, a topic mentioned for research was: ‘Are preventive measures possible?’ This relates to the request for information: ‘Can sarcoma be prevented?’ For many other cancers, there are often multiple factors that increase the risk of that cancer, such as dietary habits, sun exposure, or smoking. For sarcomas, however, there are very few risk factors known and the risk factors that are known cannot be influenced (e.g. genetic or exposure to radiation). It is therefore understandable that sarcoma patients and carers wonder if there is anything they could have done to prevent sarcoma or do to prevent this in the future. In addition to this theme of detection and prevention, respondents also requested more information on the organization of care (‘Which is the best place for sarcoma treatment?’ and ‘Can I be treated in a center abroad?’). This is an understandable theme for respondents to want more information on, as expert care is often harder to find than for common cancer patients.23 Many of the research questions, topics for advocacy, and requests for information raised by the respondents in this PSP are specific to sarcomas. In other tumours, it would be less likely to find topics involving borderline conditions, wrong pathological diagnoses, single histologies, alternate treatment options for similar clinical diagnoses, and estimation of prognosis.

The goal of this sarcoma PSP was to involve the entire community of sarcoma patients and carers to identify unanswered questions from this group about sarcomas. Therefore, an accurate representation of the sarcoma community amongst the respondents is important to ensure that questions from minority communities are not marginalized. The sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents showed that 89% had a white Caucasian ethnic origin and 70% had either a college diploma or a university degree. This is not representative of the entire population of sarcoma patients and carers. Therefore, it seems that known hard-to-reach demographic groups are underrepresented in this sarcoma PSP. This is an often-encountered problem in projects that aim to involve patients in the research process and should receive more attention.24,25 A systematic review of strategies for improving participation of socially disadvantaged groups suggests community-driven research and peer recruiters.25 These strategies are already in place for this PSP through the SPAEN network. The review also suggests using neutral terms in the recruitment process and the questionnaire itself. This can be applied in the next phase of this PSP to reach the lesser represented populations. The questionnaire used in the next step of this PSP and in any future project of the sarcoma PPRN should be written in clear and understandable language and available to complete via multiple modalities (online and paper). The involvement of patient navigators to bridge the gap between patients and researchers would be interesting to optimize the inclusion of minorities.26 For the next phase of this PSP, we will completely revise the language and layout of the questionnaire together with patient navigators with no background in research. In addition, we will develop a strategy for distribution together with patient navigators who could be part of underrepresented minorities. The relatively high number of respondents who live and work in the Netherlands can be explained by the application of an additional recruitment strategy, which was not used in other countries. Finally, there are patients who might have received the questionnaire but will not respond as it is too confronting.

The results from this first step of the sarcoma PSP can be used in multiple ways. Primarily, it identified the questions that sarcoma patients and their carers would like to see answered by research and this can guide researchers and professionals in designing their research. It also helps funding agencies in assessing whether research proposals are relevant for the target population. Additionally, these results can be used to determine research priorities for specific groups or subtypes of sarcomas, which has already been done for leiomyosarcoma based on the results from this PSP.27 The topics for advocacy that this PSP revealed can be used by patient advocacy organizations in the representation of sarcoma patients and carers. Patient advocacy organizations and health care professionals can use the requests for information that came forth to improve on information provision and materials to patients and carers. Additionally, the requests for information can support clinicians to discuss the right topics during consultations.

On the subject of patient involvement, this study shows that sarcoma patients and carers are very eager to be involved in sarcoma research as either a researcher or participant (79%). Almost all respondents (94%) agreed that patients and carers can contribute to sarcoma research meaningfully. More than half of all respondents (57%) would like to attend meetings to receive updates on the progress of research and 43% want to provide input on study design. Both these aspects of research require patients and carers to be involved in the whole study process and not just at one point in the beginning where they share perspectives. It is impressive to see that so many respondents would like to be at this level of involvement in the research process. Current literature on patient involvement mainly focusses on stating its importance and discussing (dis)advantages. No literature is available, however, on the percentage of patients and carers who want to be involved in research and what their motives are. It is important to investigate this in future to optimize patient involvement in research. This PSP is an example of how to involve patients and carers in research. To further explore the role of patients and carers and how they would like to be involved in sarcoma research, the Involvement Matrix designed by Smits et al.28 would be a good starting point.

The next step in this PSP will be to identify the top research priorities per tumor type (STS, BS, GIST, and DF). These priorities will provide guidance for research that will achieve greatest value and impact.

Conclusions

The first results of this sarcoma PSP have identified important subjects for research, but also important topics for patient advocacy and requests for information. It also showed that sarcoma patients and carers are eager to be involved in multiple aspects of sarcoma research. The next phase of this PSP will identify the top priorities per tumor type. These preliminary results can be used to guide new research in the field of sarcoma.

Acknowledgments

Funding

None declared.

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Burningham Z., Hashibe M., Spector L., Schiffman J.D. The epidemiology of sarcoma. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2012;2(1):14. doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiller C.A., Trama A., Serraino D., et al. Descriptive epidemiology of sarcomas in Europe: report from the RARECARE project. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(3):684–695. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trautmann F., Schuler M., Schmitt J. Burden of soft-tissue and bone sarcoma in routine care: Estimation of incidence, prevalence and survival for health services research. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(3):440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dangoor A., Seddon B., Gerrand C., Grimer R., Whelan J., Judson I. UK guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2016;6:20. doi: 10.1186/s13569-016-0060-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerrand C., Athanasou N., Brennan B., et al. UK guidelines for the management of bone sarcomas. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2016;6:7. doi: 10.1186/s13569-016-0047-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin B.P., Heinrich M.C., Corless C.L. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Lancet. 2007;369(9574):1731–1741. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60780-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Otero S., Moskovic E.C., Strauss D.C., et al. Desmoid-type fibromatosis. Clin Radiol. 2015;70(9):1038–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crocker J.C., Boylan A.M., Bostock J., Locock L. Is it worth it? Patient and public views on the impact of their involvement in health research and its assessment: a UK-based qualitative interview study. Health Expect. 2017;20(3):519–528. doi: 10.1111/hex.12479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aldiss S., Fern L.A., Phillips R.S., et al. Research priorities for young people with cancer: a UK priority setting partnership with the James Lind Alliance. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sacristan J.A., Aguaron A., Avendano-Sola C., et al. Patient involvement in clinical research: why, when, and how. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:631–640. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S104259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snow R., Crocker J.C., Crowe S. Missed opportunities for impact in patient and carer involvement: a mixed methods case study of research priority setting. Res Involv Engagem. 2015;1:7. doi: 10.1186/s40900-015-0007-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young K., Kaminstein D., Olivos A., et al. Patient involvement in medical research: what patients and physicians learn from each other. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0969-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domecq J.P., Prutsky G., Elraiyah T., et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tinetti M.E., Basch E. Patients’ responsibility to participate in decision making and research. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2331–2332. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasper B., Schuster K., Wilson R., et al. Global patient involvement in sarcoma care—a collaborative initiative of the connective tissue oncology society (CTOS) & Sarcoma Patients EuroNet (SPAEN) Cancers (Basel) 2022;14(4):854. doi: 10.3390/cancers14040854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tallon D., Chard J., Dieppe P. Relation between agendas of the research community and the research consumer. Lancet. 2000;355(9220):2037–2040. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crowe S., Fenton M., Hall M., Cowan K., Chalmers I. Patients’, clinicians’ and the research communities’ priorities for treatment research: there is an important mismatch. Res Involv Engagem. 2015;1:2. doi: 10.1186/s40900-015-0003-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Partridge N., Scadding J. The James Lind Alliance: patients and clinicians should jointly identify their priorities for clinical trials. Lancet. 2004;364(9449):1923–1924. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17494-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cowan K. The James Lind alliance: tackling treatment uncertainties together. J Ambul Care Manage. 2010;33(3):241–248. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181e62cda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.den Hollander D., Fiore M., Martin-Broto J., et al. Incorporating the patient voice in sarcoma research: how can we assess health-related quality of life in this heterogeneous group of patients? A study protocol. Cancers (Basel) 2020;13(1):1. doi: 10.3390/cancers13010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drabbe C., Grunhagen D.J., van Houdt W.J., et al. Diagnosed with a rare cancer: experiences of adult sarcoma survivors with the healthcare system-results from the SURVSARC study. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(4):679. doi: 10.3390/cancers13040679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soomers V., Husson O., Desar I.M.E., et al. Patient and diagnostic intervals of survivors of sarcoma: Results from the SURVSARC study. Cancer. 2020;126(24):5283–5292. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ray-Coquard I., Pujade Lauraine E., Le Cesne A., et al. Improving treatment results with reference centres for rare cancers: where do we stand? Eur J Cancer. 2017;77:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaghaghi A., Bhopal R.S., Sheikh A. Approaches to recruiting ‘hard-to-reach’ populations into re-search: a review of the literature. Health Promot Perspect. 2011;1(2):86–94. doi: 10.5681/hpp.2011.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonevski B., Randell M., Paul C., et al. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nipp R.D., Hong K., Paskett E.D. Overcoming barriers to clinical trial enrollment. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2019;39:105–114. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_243729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasper B., Achee A., Schuster K., et al. Unmet medical needs and future perspectives for leiomyosarcoma patients-a position paper from the National LeioMyoSarcoma Foundation (NLMSF) and Sarcoma Patients EuroNet (SPAEN) Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(4):886. doi: 10.3390/cancers13040886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smits D.W., van Meeteren K., Klem M., Alsem M., Ketelaar M. Designing a tool to support patient and public involvement in research projects: the Involvement Matrix. Res Involv Engagem. 2020;6:30. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-00188-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]