Abstract

For development of novel starter strains with improved proteolytic properties, the ability of Lactococcus lactis to produce Lactobacillus helveticus aminopeptidase N (PepN), aminopeptidase C (PepC), X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase (PepX), proline iminopeptidase (PepI), prolinase (PepR), and dipeptidase (PepD) was studied by introducing the genes encoding these enzymes into L. lactis MG1363 and its derivatives. According to Northern analyses and enzyme activity measurements, the L. helveticus aminopeptidase genes pepN, pepC, and pepX are expressed under the control of their own promoters in L. lactis. The highest expression level, using a low-copy-number vector, was obtained with the L. helveticus pepN gene, which resulted in a 25-fold increase in PepN activity compared to that of wild-type L. lactis. The L. helveticus pepI gene, residing as a third gene in an operon in its host, was expressed in L. lactis under the control of the L. helveticus pepX promoter. The genetic background of the L. lactis derivatives tested did not affect the expression level of any of the L. helveticus peptidases studied. However, the growth medium used affected both the recombinant peptidase profiles in transformant strains and the resident peptidase activities. The levels of expression of the L. helveticus pepD and pepR clones under the control of their own promoters were below the detection limit in L. lactis. However, substantial amounts of recombinant pepD and PepR activities were obtained in L. lactis when pepD and pepR were expressed under the control of the inducible lactococcal nisA promoter at an optimized nisin concentration.

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) play an important role in dairy fermentation processes and have a great influence on the quality and preservation of end products. The primary roles of LAB are to produce lactic acid from lactose, resulting in a pH decrease, and, by proteolysis, to liberate short peptides and free amino acids affecting the flavor and texture of dairy products.

Since the concentration of free amino acids and small peptides is insufficient to support the growth of LAB to high cell densities in milk, these bacteria are dependent on a proteolytic system to liberate free amino acids from milk proteins. The proteolytic system of LAB consists of a cell envelope-associated proteinase, membrane-bound transport systems, and several cytoplasmic peptidase classes. The proteolytic system is particularly important in the development of flavor and texture of cheeses (9). Since Lactococcus strains, along with those of Lactobacillus, are widely used as starters in cheese manufacture, substantial effort has been directed in the last two decades toward elucidating the proteolytic mechanism of Lactococcus lactis. More recently, the proteolytic system of lactobacilli has also been extensively examined.

Over 10 different peptidase types have been identified in various LAB strains, and a large number of peptidase genes have been cloned from different Lactococcus and Lactobacillus species and characterized (reviewed recently by Christensen et al. [4]). For most of the characterized peptidases from Lactobacillus helveticus, an L. lactis counterpart with a similar type of specificity can also be found. However, the overall proteolytic activity of L. helveticus has been found to be higher than that of L. lactis (14, 22). This has led to the use of lysed or heat-shocked L. helveticus cells as flavor adjuncts in cheese processes based on the use of other starters (8). The wide range of peptidases that have been molecularly characterized is now enabling heterologous-expression studies with these peptidases in different lactic acid bacteria. This will be of importance in elucidation of the roles of different peptidases in cheese manufacture, enhancement of the maturation process, and development of new cheeses with improved characteristics.

Based on the favorable proteolytic properties of L. helveticus, our goal has been to study whether the peptidolytic profiles of L. lactis can be changed or improved with peptidases from L. helveticus to provide new strains for testing in cheese processes. In this study, we have constructed new L. lactis strains carrying six previously characterized peptidase genes, i.e., pepN, pepX, pepC, pepI, pepD, and pepR, from industrial L. helveticus strain 53/7 and studied their expression in several peptidase mutants of L. lactis and in different growth media. The results revealed that not all of the promoters from the L. helveticus peptidases are functional in L. lactis. Furthermore, it was shown that expression of the tested L. helveticus peptidases was not affected by the genetic background of L. lactis peptidases. In addition, growth defects of peptidase mutants of L. lactis could be complemented with corresponding L. helveticus genes, and, surprisingly, L. helveticus PepN alone could also complement an L. lactis mutant lacking five peptidases (hereafter termed a fivefold peptidase-negative mutant of L. lactis). Unexpectedly, there were also substantial differences in the responses to the growth media for some of the peptidases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The lactococcal strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. L. lactis cells were routinely grown at 30°C in M17 medium (Difco) supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose or lactose. For determination of enzyme activities, the recombinant L. lactis strains were cultivated to stationary phase in glucose-M17 (GM17) for 12 h and in citrate-buffered milk (Valio Ltd., Helsinki, Finland) for 16 h. Erythromycin and chloramphenicol were used as selection agents at concentrations of 5 and 10 μg/ml, respectively, when needed. Escherichia coli DH5α was grown in Luria broth medium with aeration at 37°C. Erythromycin (300 μg/ml) was added to the growth medium when required. L. helveticus was grown in MRS (Difco) broth at 37°C without aeration.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| L. helveticus 53/7 | Industrial starter strain | Valio Ltd. |

| L. lactis subsp. cremoris | ||

| MG1363 | Plasmid-free derivative of NCDO712 | 10 |

| MG1363[XTOCN]− | ΔpepX ΔpepT ΔpepO ΔpepC ΔpepN | 19 |

| MG1363[NC]− | ΔpepN ΔpepC | 19 |

| MG1363 (Prt+ Lac+) | pLP712 | 10 |

| MG1363[XTOCN]− (Prt+ Lac+) | ΔpepX ΔpepT ΔpepO ΔpepC ΔpepN (pLP712) | 19 |

| MG1363[X]− (Prt+ Lac+) | ΔpepX (pLP712) | 16 |

| MG1363[N]− (Prt+ Lac+) | ΔpepN (pLP712) | 10 |

| L. lactis NZ9000 | nisR+nisK+ | NIZOa |

| E. coli DH5α | F80 lacZDM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | 12 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKTH2095 | Emr; 4.5 kb; pGK12 with pUC19 multilinker, pWV01 replicon | 13 |

| pIL277 | Emr; 4.3 kb; pAMβ1 replicon | 24 |

| pNZ8037 | Cmr; 3.1 kb; pSH71 replicon, PnisA | 5 |

| pKTH2073 | pUC19 with L. helveticus pepN as 3.7-kb XbaI insert | 26 |

| pKTH2097 | pJDC9 with L. helveticus pepX in 2.6-kb BamHI insert | 31 |

| pKTH2105 | pJDC9 with L. helveticus pepD as 1.6-kb BamHI-SalI insert | 30 |

| pKTH2082 | pJDC9 with L. helveticus pepR as 1.1-kb BamHI-SalI insert | 27 |

| pKTH2172 | L. helveticus pepN in pKTH2095 under control of its own promoter | This work |

| pKTH2171 | L. helveticus pepX in pKTH2095 under control of its own promoter | This work |

| pKTH2175 | L. helveticus pepC in pIL277 under control of its own promoter | This work |

| pKTH2179 | L. helveticus pepI in pKTH2095 under control of PpepX | This work |

| pKTH2150 | L. helveticus pepD in pKTH2095 under control of its own promoter | This work |

| pKTH2170 | L. helveticus pepR in pKTH2095 under control of its own promoter | This work |

| pKTH2182 | L. helveticus pepD in pNZ8037 under control of PnisA | This work |

| pKTH2193 | L. helveticus pepR in pNZ8037 under control of PnisA | This work |

NIZO, Ede, The Netherlands.

DNA methods.

Chromosomal DNA from L. helveticus 53/7 and L. lactis was isolated essentially as described by Marmur (17). Plasmid DNA was isolated from L. lactis by alkaline lysis (21) of cells. Purification of plasmid DNA was performed by phenol-chloroform extraction followed by anion-exchange chromatography (DNA Plasmid Midi Kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Plasmid DNAs were isolated from E. coli by using commercial kits (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden, and Wizard, Madison, Wis.). Oligonucleotides were synthesized with an Applied Biosystems DNA synthesizer (model 392) and purified by gel filtration with NAP-10 columns (Pharmacia). Standard DNA methods were used as described by Sambrook et al. (21). Lactococcal and E. coli strains were electrotransformed by using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser under conditions of 2.5 kV, 400 Ω, and 25 μF and 2.5 kV, 200 Ω, and 25 μF, respectively.

Plasmid constructions.

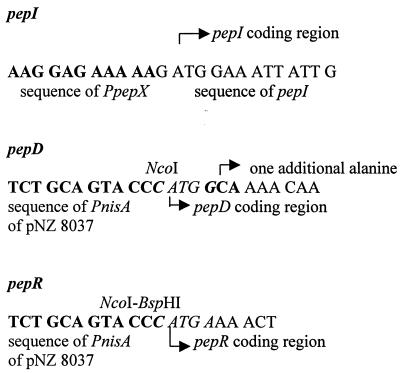

All of the plasmids constructed in this study are listed in Table 1. A 3.7-kb insert carrying the L. helveticus pepN gene (26) was obtained from pKTH2073 by digestion with XbaI and ligated into pKTH2095 (23). The new plasmid, pKTH2172, was propagated in an E. coli DH5α host. A 2.7-kb insert carrying pepX (31) was obtained from plasmid pKTH2097 by digestion with BamHI and ligated into pKTH2095 to yield a new plasmid, pKTH2171. In L. helveticus, the pepC gene is expressed both as a monocistronic mRNA and as a polycistronic transcript with its adjacent, downstream open reading frame (orf2) (29). For this study, the pepC gene was synthesized without the downstream orf2 by PCR using a pair of specific primers (5′-AAAACTGCAGAGCTTAAGGCAGTTCAATCAGATCAG-3′ and 5′-AAAACTGCAGCTAAATTGCTAGCAAATTTTTTGCC-3′) containing PstI sites at their 5′ ends for cloning. Ligation of the 1.7-kb PstI fragment into the pIL277 vector gave a new recombinant plasmid, pKTH2175. The 1.079-kb L. helveticus pepI (28) coding region was ligated with the L. helveticus pepX promoter by using specific primer pairs (5′-CCGGAATTCGCGTTCAATTTATTATTGCAATTTACG-3′–5′-CA ATAATTTCCATCTTTTTCTCCTTTGTCAGTATTATTACC-3′ and 5′-CAAAGGAGAAAAAGATGGAAATTATTGAAGGAAAAATGCC-3′–5′- GGGGAATTCCAGTAACCAACAAACGCTACGTTAAAG-3′), resulting in a transcriptional fusion (PpepX= pepI) (Fig. 1). The new plasmid, based on the vector pKTH2095, was designated pKTH2179. Genes pepD (30) and pepR (27) were digested from pKTH2105 and pKTH2082 with BamHI-SphI and BamHI-SalI, respectively. The new plasmids, pKTH2150 and pKTH2170, which were propagated in E. coli DH5α, were constructed by ligating the pepD and pepR inserts into the vector pKTH2095. The recombinant plasmids pKTH2172, pKTH2171, pKTH2175, pKTH2179, pKTH2150, and pKTH2170, harboring pepN, pepX, pepC, PpepX-pepI, pepD, and pepR, respectively, were introduced into the fivefold peptidase mutant L. lactis MG1363 [XTOCN]− (Table 1) by electroporation and screened as described by Pedersen et al. (20) or by PCR using specific probes. The pepD and pepR genes were also cloned as translational fusions with the inducible lactococcal nisin promoter (PnisA) in vector pNZ8037 (5). The pepD coding region was synthesized by PCR using a pair of primers (5′-CATGCCATGGCAAAACAAACAGAATGTAC-3′ and 5′-CGGGATCCGGAATTGATGTGGTACTTGTTCCAG-3′) containing NcoI and BamHI sites at their 5′ and 3′ ends for cloning. The NcoI cloning site at the translation start codon gave rise to an additional alanine after the initiation methionine on the coding sequence of pepD. The NcoI-BamHI fragment of 1.7 kb, carrying the pepD structural gene, was ligated into the pNZ8037 vector (Fig. 1) and transformed into L. lactis NZ9000 (Table 1). The pepR coding region was synthesized by PCR using a pair of primers (5′-CAATGTCATGAAAACTGGTACTAAAATCATTAC-3′ and 5′-CGGGATCCTTGTTATAATTCTAGCATATTAGGGAG-3′) containing BspHI and BamHI sites at their 5′ and 3′ ends for cloning. The BspHI-BamHI fragment of 1.0 kb, carrying the pepR structural gene, was ligated with pNZ8037 (Fig. 1) and transferred into NZ9000. The recombinant plasmids pKTH2182 and pKTH2193, harboring the pepD and pepR inserts, respectively, were screened as described by Pedersen et al. (20).

FIG. 1.

Promoter fusion regions of pepI, pepD, and pepR.

RNA isolation and Northern hybridization.

Total RNA was isolated from L. lactis and L. helveticus cells, grown in GM17 and MRS, respectively, by using an RNeasy Midi Kit (Qiagen). RNA gel electrophoresis and Northern blots were performed as described previously (11). A 0.24- to 9.5-kb RNA ladder (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) was used as a standard. For use as a hybridization probe, an 864-bp HpaI-BamHI fragment of L. helveticus pepN, a 994-bp HaeIII fragment of L. helveticus pepX, a 1.0-kb PCR fragment of pepC (primers 5′-AGGTCCCGGGTAAAGGAGGATTTTTAATGG-3′ and 5′-CACGGCGGTAAAGATTGG-3′), and a 1.079-kb PCR fragment of the pepI coding region (primers 5′-CAAAGGAGAAAAAGATGGAAATTATTGAAGGAAAAATGCC-3′ and 5′-GGCGAATTCCAGTAACCAACAAACGCTACGTTAAAG-3′) were labeled with digoxigenin-dUTP (DIG; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). A DIG luminescence detection kit (Boehringer) was used for hybrid detection.

Enzyme assays.

L. lactis cells were disrupted with an Ultrasonic 2000 sonicator (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany), cell debris was removed, and the PepN, PepX, PepC, and PepI activities of the cell extracts were determined by the method of El Soda and Desmazeaud (7). The substrates used were 16.4 mM l-lysine p-nitroanilide (Sigma) for PepN and PepC, 16.4 mM l-proline p-nitroanilide for PepI, and 16.4 mM l-glysine–proline p-nitroanilide for PepX. The buffers and temperatures used were 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 45°C for PepN, 50 mM 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES; pH 6.5) and 45°C for PepX, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) and 40°C for PepC, and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 37°C for PepI, respectively. To determine PepC activity, PepN activity was inhibited with 5 mM EDTA (26, 29). PepD activity was determined from cell extracts by the Cd-ninhydrin method (6) with 2 mM Leu-Leu in 50 mM MES (pH 6.0) at 55°C. PepR activity was determined as described by Baankreis and Exterkate (1) at 37°C with 2 mM Pro-Leu as a substrate. In determining PepD and PepR activity, 1 U is defined as the amount of enzyme activity producing a variation of 0.01 in absorbance at 505 or 480 nm, respectively, per minute. The protein concentrations were determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent based on the Bradford dye-binding procedure (2). Bovine serum albumin (Sigma) was used as a protein standard. All enzyme activities presented are averages of two to four parallel measurements.

SDS-PAGE.

The production of PepD and PepR under nisin-induced conditions was monitored by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (11% [wt/vol] acrylamide gels) using the procedure of Laemmli (15). The gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R250. LMW-SDS proteins (Pharmacia) were used as molecular weight markers.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Construction of strains for expression of L. helveticus genes in L. lactis.

The pepN, pepX, pepD, and pepR genes of L. helveticus were subcloned from the plasmids described in Materials and Methods into E. coli DH5α by using the vector pKTH2095. The new plasmids, designated pKTH2172, pKTH2171, pKTH2150, and pKTH2170, respectively, were transferred into a fivefold peptidase-negative mutant strain, [XTOCN]−, of L. lactis MG1363 (Table 1). The pepC and pepI genes reside in operon structures in L. helveticus (7, 28). For this work, the pepC gene and pepI under the control of the pepX promoter (PpepXpepI) were isolated by PCR, transferred into pKTH2095, and cloned as plasmid constructs pKTH2179 and pKTH2175, respectively, directly into L. lactis. Due to stability problems encountered with pepC in pKTH2095, its cloning vector was changed to pIL277. The pepN, pepX, pepC, and pepI genes (pKTH2172, pKTH2171, pKTH2175, and pKTH2179) were also transferred into the wild-type strain L. lactis MG1363 with and without the lactose protease plasmid pLP712. Furthermore, pepN, pepX, and pepC were transferred into the MG1363[XTOCN]− mutant carrying pLP712. The pepN, pepX, and pepC genes were also introduced into pLP712-carrying L. lactis mutants MG1363[N]−, MG1363[X]−, and MG1363[NC]−, respectively (Table 1).

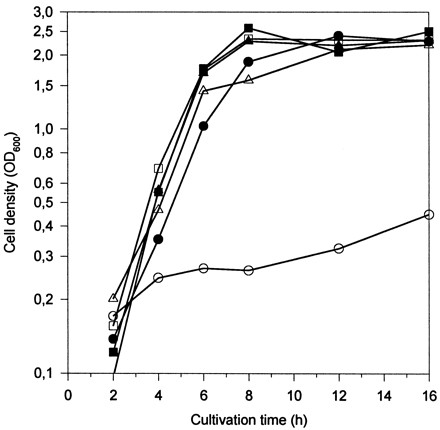

Growth patterns of lactococcal strains.

The growth curves of the lactococcal strains and strain-plasmid combinations tested in this study revealed no significant differences between the strains when grown in GM17. In milk, the growth of the fivefold peptidase-negative mutant MG1363[XTOCN]− and the pepN and pepN pepC deletion mutants MG1363[N]− and MG1363[NC]− was impaired as described earlier by Mierau et al. (19). L. helveticus pepN (pKTH2172) in L. lactis restored the growth of MG1363[N]− and MG1363[NC]− to the wild-type level. In contrast to overexpressed L. lactis pepN in pNZ1120, which can restore the pepN deficiency but, cannot complement the growth defects of other pep mutations in MG1363[XTOCN]− in milk (19), L. helveticus pepN (pKTH2173) was able to restore the growth of this fivefold mutant almost to the wild-type L. lactis level (Fig. 2). This may suggest broader substrate specificity for L. helveticus pepN than for L. lactis. This is also in agreement with our earlier observation that L. helveticus PepN can to some extent hydrolyze, for example, proline-containing peptides (P. Varmanen and A. Palva, unpublished data). As expected, L. helveticus pepC and pepX alone could not compensate for the growth defects of MG1363[XTOCN]− in milk.

FIG. 2.

Growth curves of L. lactis MG1363 (□) and its derivatives MG1363[N]− (▵), MG1363[XTOCN]− (○), MG1363 + pepN (■), MG1363[N]− + pepN (▴), and MG1363[XTOCN]− + pepN (●) in milk.

Expression of L. helveticus peptidase genes in L. lactis.

Peptidase activities were studied at different time points of growth. Enzyme activities were determined from cell lysates of milk- or GM17-grown L. lactis MG1363 and MG1363[XTOCN]− hosts in the presence or absence of the pLP712 plasmid and from their transformants harboring L. helveticus pepN, pepX, pepC, pepI, pepD, or pepR. In addition, PepN, PepX, and PepC activities were also determined in L. lactis MG1363[N]−, MG1363[X]−, and MG1363[NC]− peptidase mutants, respectively. Recombinant strains harboring pepN, pepX, pepC, or pepI gave rise to detectable enzyme activities of the L. helveticus-derived peptidases both in M17- and in milk-grown cells. In contrast, no L. helveticus-derived PepD or PepR activity exceeding the background level of L. lactis was found. The genetic background of any of the L. lactis derivatives tested did not affect the expression level of any of the L. helveticus peptidases studied. Since the amounts of each L. helveticus peptidase activity were equal in all lactococcal hosts, only the enzyme activities of MG1363 and its different L. helveticus peptidase transformants are shown.

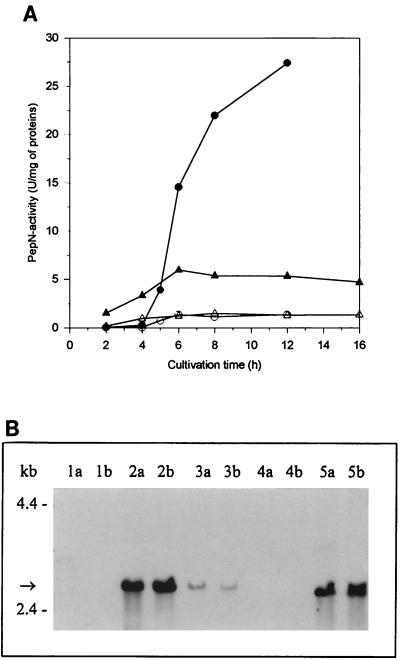

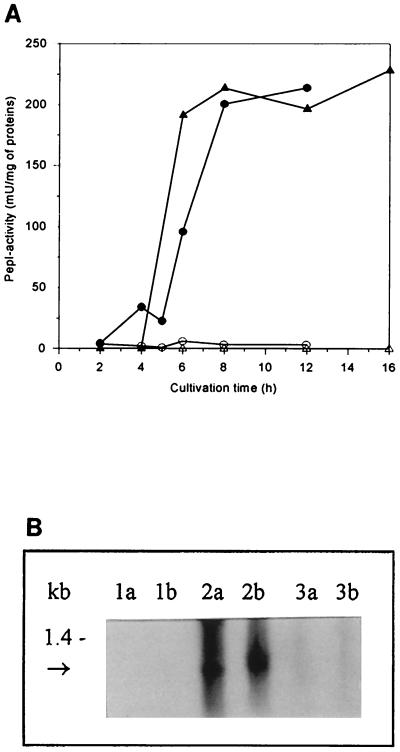

The highest levels of total PepN activity detected were 27 U/mg of protein in GM17-grown cells and 5 U/mg of protein in milk-grown cells. The resident PepN activity of MG1363 was approximately 1 U/mg of protein in both GM17- and milk-grown cells; thus, no down-regulation in milk was observed, in contrast to the recombinant activity (Fig. 3A). A similar high productivity has also been observed by Christensen et al. (3), who found a profound increase in PepN activity in GM17 when the L. helveticus pepN gene was expressed in a multicopy plasmid in L. lactis. In our study, however, the vector pKTH2095, based on pGK12, had only 1 or 2 copies in L. lactis (23).

FIG. 3.

Expression of L. helveticus pepN in L. lactis. (A) Peptidase activity of L. lactis MG1363 and its pepN+ transformant strain in GM17- and milk-grown cells. GM17-grown cells: MG1363 (○), MG1363 + pepN (●). Milk-grown cells: MG1363 (▵), MG1363 + pepN (▴). (B) Northern blot hybridization. Lanes a, samples (5 μg of total RNA) taken at an OD600 of 0.5; lanes b, samples taken 3 h thereafter. Lanes 1, MG1363[XTOCN]; lanes 2, pepN+ transformant of MG1363[XTOCN]; lanes 3, L. helveticus 53/7; lanes 4, MG1363; lanes 5, pepN+ transformant of MG1363. The size of pepN mRNA is indicated with an arrow.

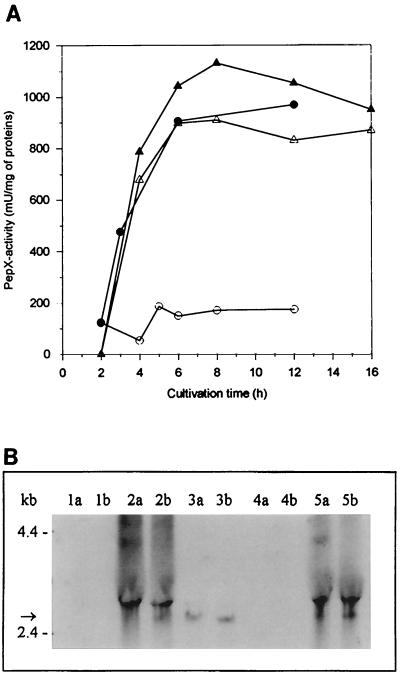

The recombinant PepX activity in GM17-grown cells was fivefold higher than the resident lactococcal PepX activity. In milk-grown cells, the recombinant PepX activity was only 20% of that obtained in GM17, and a majority of the total PepX activity was derived from the lactococcal PepX. The marked decrease of recombinant PepX activity in milk was also confirmed with L. lactis MG1363[X] carrying L. helveticus pepX. In MG1363, use of the milk medium resulted in a fivefold increase in resident PepX activity (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Expression of L. helveticus pepX in L. lactis. (A) Peptidase activity of L. lactis MG1363 and its pepX+ transformant strain in GM17- and milk-grown cells. GM17-grown cells: MG1363 (○), MG1363 + pepX (●). Milk-grown cells: MG1363 (▵), MG1363 + pepX (▴). (B) Northern blot hybridization. Lanes a, samples (20 μg of total RNA) taken at an OD600 of 0.5; lanes b, samples taken 3 h thereafter. Lanes 1, MG1363[XTOCN]−; lanes 2, pepX+ transformant of MG1363[XTOCN]−; lanes 3, L. helveticus 53/7; lanes 4, MG1363; lanes 5, pepX+ transformant of MG1363. The size of pepX mRNA is indicated with an arrow.

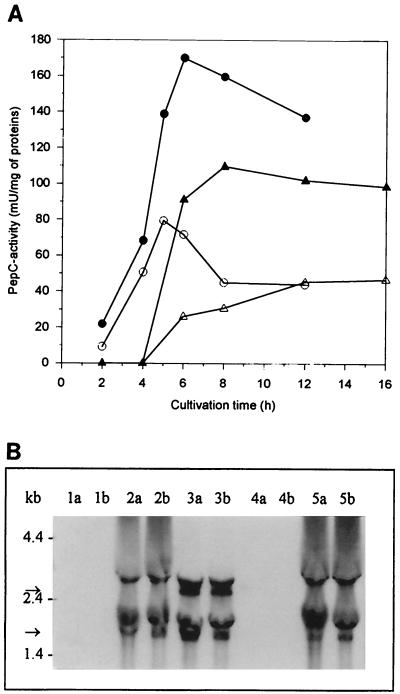

Recombinant PepC activity was twice the resident PepC activity in both GM17- and milk-grown cells. Both the recombinant and resident PepC activities were down-regulated approximately by a factor of two in milk medium (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Expression of L. helveticus pepC in L. lactis. (A) Peptidase activity of L. lactis MG1363 and its pepC+ transformant strain in GM17- and milk-grown cells. (A) GM17-grown cells: MG1363 (○), MG1363 + pepC (●). Milk-grown cells: MG1363 (▵), MG1363 + pepC (▴). (B) Northern blot hybridization. Lanes a, samples (20 μg of total RNA) taken at an OD600 of 0.5; lanes b, samples taken 3 h thereafter. Lanes 1, MG1363[XTOCN]; lanes 2, pepC+ transformant of MG1363[XTOCN]; lanes 3, L. helveticus 53/7; lanes 4, MG1363; lanes 5, pepC+ transformant of MG1363. The sizes of mono- and polycistronic pepC mRNAs are indicated with arrows.

In this study, the pepI gene was expressed under the control of the L. helveticus pepX gene promoter. PepI activities in GM17 and milk were almost equal. A very slight resident activity against the PepI substrate was detected in GM17-grown MG1363 cells, but it was undetectable in cells grown in milk (Fig. 6A). Surprisingly, in contrast to PepX, there was no down-regulation of PepI in milk, suggesting that PepX might be affected at the enzymatic level.

FIG. 6.

Expression of L. helveticus pepI in L. lactis. (A) Peptidase activity of L. lactis MG1363 and its pepI+ transformant strain in GM17- and milk-grown cells. GM17- grown cells: MG1363 (○), MG1363 + pepI (●). Milk-grown cells: MG1363 (▵), MG1363 + pepI (▴). (B) Northern blot hybridization. Lanes a, samples (40 μg of total RNA) taken at an OD600 of 0.5; lanes b, samples taken 3 h thereafter. Lanes 1, MG1363[XTOCN]; lanes 2, pepI+ transformant of MG1363[XTOCN]; lanes 3, L. helveticus 53/7. The size of pepI mRNA is indicated with an arrow.

It has previously been shown that high peptide content in a growth medium (like in M17) represses some components of the proteolytic system in lactococci. The effect on specific peptidases has, however, been shown to be strain dependent (18). Unexpectedly, significant repression of some of the peptidases was observed in low-peptide-content medium in this study.

To elucidate the levels of transcripts of the L. helveticus pepN, pepX, pepC, pepI, pepD, and pepR genes, Northern blot hybridization was performed with probes specific for each peptidase as described in Materials and Methods. Transcripts of expected sizes—i.e., about 2.8 kb (Fig. 3B), 2.6 kb (Fig. 4B), 1.7 kb (Fig. 5B), and 1.1 kb (Fig. 6B)—were detected in L. lactis transformants harboring L. helveticus pepN, pepX, pepC, and pepI, respectively. There appeared to be no significant differences between the levels of L. helveticus pepN, pepX, and pepC transcripts when expressed in either the wild type or the fivefold peptidase-negative L. lactis host. None of the probes gave any peptidase mRNA-specific signals from the host L. lactis strain. The relative amount of L. helveticus pepN transcripts in L. lactis was over 10-fold larger than that in L. helveticus (Fig. 3B), whereas the amounts of pepX and pepC transcripts were slightly larger in L. helveticus than in L. lactis (Fig. 4B and Fig. 5B). This suggests that the pepN promoter in L. helveticus is partially down-regulated in MRS medium. The pepD and pepR transcripts in L. lactis were below the detection limits under their own promoters, suggesting that these promoters were not recognized in L. lactis (data not shown). This is in agreement with the promoter structures of pepD and pepR (29, 30), which clearly differ from the general consensus sequences of L. lactis promoters (25). Therefore, expression of the pepD and pepR genes under the control of PnisA in L. lactis was studied.

Expression of pepD and pepR under the control of PnisA.

The pepD and pepR structural genes were isolated by PCR with primers which were designed according to previously characterized L. helveticus genes and contained at their initiation codons restriction sites suitable for cloning. After ligation of these genes into pNZ8037, the resulting plasmids, pKTH2182 and pKTH2193 (Table 1), were transferred into L. lactis NZ9000. Expression of pepD and pepR in these recombinant strains was induced with nisin at different concentrations. Recombinant peptidase activity assays and SDS-PAGE analyses of nisin-induced samples withdrawn as a function of growth were carried out. The highest recombinant peptidase activities were obtained with a nisin concentration of 5 ng/ml, whereas the higher nisin concentrations resulted in retarded growth and a decline of peptidase activities. SDS-PAGE of the soluble fractions of lysates showed increasing amounts of PepD and PepR with nisin concentrations up to 20 and 5 ng/ml, respectively (Fig. 7B and C). SDS-PAGE carried out from insoluble fractions of lysates showed that recombinant PepD and PepR began to accumulate in the cell as insoluble aggregates at nisin concentrations of 0.5 and 5 ng/ml, respectively.

FIG. 7.

Expression of L. helveticus pepD and pepR in L. lactis NZ9000. (A) Relative recombinant PepD and PepR activities produced under the control of PnisA in GM17-grown cells after induction with nisin. Shown are PepD activity in NZ9000 + pepD at 1 h (●) and 3 h (○) after induction with nisin and PepR activity in NZ9000 + pepR at 1 h (▵) and 3 h (▴) after induction with nisin. (B) SDS-PAGE of the recombinant PepD-producing L. lactis transformant 3 h after induction with nisin. (C) SDS-PAGE of the recombinant PepR-producing L. lactis transformant 3 h after induction with nisin. Lanes 1, uninduced cells; lanes 2 to 6, induction with 0.05, 0.5, 5, 20, and 50 ng of nisin, respectively.

Wegmann et al. (32) have successfully expressed four different L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis peptidase genes, pepI, pepL, pepW, and pepG, under the control of PnisA. These genes have no counterparts in L. lactis. In milk, nisin induction of pepG and pepW resulted in growth acceleration. The study by Wegmann et al. (32) and the results of our work presented here demonstrate that the proteolytic system of L. lactis can be modulated with lactobacillus peptidase genes. Cheese slurry experiments and cheese trials performed with these new strains will demonstrate how the modulated proteolytic L. lactis system and accelerated amino acid release affect the ripening and organoleptic properties of the model cheeses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Ilkka Palva for valuable discussions. We also thank Jaana Jalava for technical assistance and Jan Kok and Roland Siezen for lactococcal strains and expression vectors.

This work was conducted as part of the STARLAB project (contract ERBBIO4CT960016) of the European Union.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baankreis R, Exterkate F. Characterization of a peptidase from Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris HP that hydrolyses di- and tripeptides containing proline or hydrophilic residues as the amino-terminal amino acid. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1991;14:317–323. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen J E, Johnson M, Steele J L. Production of cheddar cheese using a Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris SK11 derivative with enhanced aminopeptidase activity. Int Dairy J. 1995;5:367–379. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen J E, Dudley E G, Pedersen J A, Steele J L. Peptidases and catabolism in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:217–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Ruyter P G G A, Kuipers O P, de Vos W M. Controlled gene expression systems for Lactococcus lactis with the food-grade inducer nisin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3662–3667. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3662-3667.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doi E, Shibata D, Matoba T. Modified colorimetric ninhydrin methods for peptidase assay. Anal Biochem. 1981;118:173–184. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Soda M, Desmazeaud M. Les peptide hydrolases des lactobacilles du groupe Thermobacterium. Mise en évidence de ces activités chez Lactobacillus helveticus, L. acidophilus, L. lactis et L. bulgaricus. Can J Microbiol. 1982;28:1181–1188. . (In French.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Soda M. The role of lactic acid bacteria in accelerated cheese ripening. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;12:239–252. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox P. Proteolysis during cheese manufacture and ripening. J Dairy Sci. 1989;72:1379–1400. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gasson M J. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO 712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:1–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.1-9.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hames B, Higgins S. Nucleic acid hybridisation: a practical approach. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahala M, Palva A. The expression signals of the Lactobacillus brevis slpA gene direct efficient heterologous protein production in lactic acid bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;51:71–78. doi: 10.1007/s002530051365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khalid N M, Marth E H. Lactobacilli—their enzymes and role in ripening and spoilage of cheese: a review. J Dairy Sci. 1990;73:2669–2684. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leenhouts K, Buist G, Bolhuis A, ten Berge A, Kiel J, Mierau I, Dabrowska M, Venema G, Kok J. A general system for generating unlabelled gene replacement in bacterial chromosomes. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;253:217–224. doi: 10.1007/s004380050315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marmur J. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from microorganisms. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meijer W, Marugg J D, Hugenholtz J. Regulation of proteolytic enzyme activity in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:156–161. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.156-161.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mierau I, Kunji E R S, Leenhouts K J, Hellendoorn M A, Haandrikman A J, Poolman B, Konings W N, Venema G, Kok J. Multiple-peptidase mutants of Lactococcus lactis are severely impaired in their ability to grow in milk. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2794–2803. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2794-2803.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedersen M L, Arnved K R, Johansen E. Genetic analysis of the minimal replicon of the Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis citrate plasmid. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;244:374–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00286689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasaki M, Basman B W, Tan P S T. Comparison of proteolytic activities in various lactobacilli. J Dairy Res. 1995;62:601–610. doi: 10.1017/s0022029900031332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savijoki K, Kahala M, Palva A. High level heterologous production in Lactococcus and Lactobacillus using a new secretion system based on the Lactobacillus brevis signals. Gene. 1997;186:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00717-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon D, Chopin A. Construction of a vector plasmid family and its use for molecular cloning in Streptococcus lactis. Biochimie. 1988;70:559–566. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(88)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van de Guchte M, Kok J, Venema G. Gene expression in Lactococcus lactis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;88:73–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb04958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varmanen P, Vesanto E, Steele J L, Palva A. Characterization and expression of the pepN gene encoding a general aminopeptidase from Lactobacillus helveticus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;124:315–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varmanen P, Steele J L, Palva A. Characterization of a prolinase gene and its product and an adjacent ABC transporter gene from Lactobacillus helveticus. Microbiology. 1996;142:809–816. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-4-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varmanen P, Rantanen T, Palva A. An operon from Lactobacillus helveticus composed of a proline iminopeptidase gene (pepI) and two genes coding for putative members of the ABC transporter family of proteins. Microbiology. 1996;142:3459–3468. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-12-3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vesanto E, Varmanen P, Steele J L, Palva A. Characterization and expression of the Lactobacillus helveticus pepC gene encoding a general aminopeptidase. Eur J Biochem. 1994;224:991–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vesanto E, Peltoniemi K, Purtsi T, Steele J L, Palva A. Molecular characterization, over-expression and purification of novel dipeptidase from Lactobacillus helveticus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;45:638–645. doi: 10.1007/s002530050741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vesanto E, Savijoki K, Rantanen T, Steele J L, Palva A. An X-propyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase (pepX) gene from Lactobacillus helveticus. Microbiology. 1995;141:3067–3075. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-12-3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wegmann U, Klein J R, Drumm I, Kuipers O P, Henrich B. Introduction of peptidase genes from Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis into Lactococcus lactis and controlled expression. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4729–4733. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.4729-4733.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]