Abstract

Acute pediatric burn injuries often result in chronic sequelae that affect physical, psychological, and social outcomes. To date, no review has comprehensively reported on the impact of burn injuries across all three domains in school-aged children. The aim of this systematic review was to identify published literature that focuses on the impact of burn injuries on physical, psychological, or social functioning, and report upon the nature of study characteristics and their outcomes. We included literature published after 1980, focusing on burn outcomes in children aged 5 to 18 years. Each eligible study was systematically reviewed and primary outcomes were classified into outcome domains based on existing frameworks. Fifty-eight studies met inclusion criteria, and reported on physical (n = 24), psychological (n = 47), and social (n = 29) domains. The majority of the studies had sample sizes of <100 participants, burn size of <40%, and findings reported by parents and/or burn survivors. Only eight of 107 different measures were used in three or more studies. Parents and burn survivors generally reported better physical and social outcomes and worse psychological functioning compared to non-burn populations. Physical disabilities were associated with psychological and social functioning in several studies. Follow-up data reported improvements across domains. This review demonstrates the importance of physical, psychological, and social status as long-term outcomes in burn survivors. Mixed findings across three outcome domains warrant long-term research. Findings of this review will guide the foundation of comprehensive burn and age-specific instruments to assess burn recovery.

Burn-related injuries in children and adolescents (5 to under 19 years of age) account for roughly 15% of burn hospital admissions.1 With improvements in burn care, research efforts have expanded to include the study of patient-centered outcomes—tailored to specific health care needs of individuals.2 Long-term health-related quality of life (HRQL) of burn survivors are now explored and ways for their improvement are sought. For the purpose of this review, HRQL refers to the health domains pertinent to quality of life that focuses on people’s level of ability, daily functioning, and capacity to experience a fulfilling life.3 It is important to assign and assemble items relevant to the outcome domains that are of significance after a burn injury. The viewpoints of clinicians, pediatric burn survivors, and their parents is especially important in order for this scope of domains and survey items to lead to interventions useful or impactful in clinical care.

Burn survivors experience physical, psychological and social challenges in both the short and long term. Complications during the acute stage often involve fluid shifts, wounds, infections, pain, or cardiopulmonary issues. Long-term physical complications are different, including contractures, hypertrophic scarring, heterotopic ossification, difficulties with thermoregulation, and pruritus.4,5 Metabolic changes, which contribute to loss of muscle mass and weakness, may delay growth and development in young children.6 Adverse outcomes and complications are often treated with reconstructive surgery, intensive physical and occupational therapy, and other special accommodations (eg, environmental temperature control, access to routine medical care such as colonoscopy when an IV cannot be inserted in burnt extremities) in order to limit long-term disabilities.7 Impaired physical functioning impacts psychological outcomes, such as posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) which are less severe and persistent than posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, disruptive behavior, body image, or cognitive functioning.8–10 Alternatively, psychological functioning also impacts physical functioning where maladjustment can hinder physical performance. Social outcomes such as peer relations and community participation are influenced as well, especially in those injured during the adolescence where peer approval is particularly important. Since the consequences of a burn injury can persist into adulthood, it is vital to understand the long-term consequences of burn injuries on physical, psychological, and social outcomes from a developmental lens.

Erikson identifies several stages of psychosocial development that define the critical role psychological and social functioning plays in human development.11 The fourth and fifth stages are important to consider in the context of this study. The fourth stage, industry versus inferiority (approximately 6–12 years), is defined by increased socialization at home and at school through interactions with peers alongside the drive to be competent and developing a greater sense of reality. In the fifth stage of identity versus role confusion (approximately 12–18 years), social identity, values, and goals are further established. Disruption of typical development at either stage can negatively influence functioning,12,13 therefore impacting HRQL.

Previous systematic reviews have analyzed physical,14 psychological,15 and social functioning16–18 separately, were conducted in adult burn survivors,18,19 or focused only on interventions.20–27 The current systematic review is unique as, to our knowledge, there are no existing reviews that comprehensively report upon physical, psychological, and social outcomes in burn survivors 5 to 18 years of age. This is one of the first reviews to add a contextual perspective to the burn literature by encompassing all three domains in burn survivors 5 to 18 years of age.17,20 As such, the aim of this review is to report the physical, psychological, and social impact as well as symptoms of burn injuries in pediatric burn survivors aged 5 to 18 years, and link outcome domains to existing frameworks for the purpose of providing a foundation for measurement of outcomes in burn recovery.

METHODS

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were identified through PubMed, Web of Science, and a manual reference check. Search terms covered both broad and domain specific terms such as “pediatric burn” and “health-related quality of life,” “pediatric burn,” and “outcomes,” or “pediatric burn” and “psychosocial recovery” (Supplementary Appendix 1). Studies reporting on pediatric and adolescent burn survivors’ outcomes (5–18 years at time of assessment), written in English, and published after 1980 to April 2021 in a peer-reviewed journal were included. We also performed a manual reference check on other study reviews (eg, meta-analysis, systematic reviews, or editorials) to ensure potentially eligible articles were not missed.

Article Review Process

The first author (K.F.P.) conducted the literature search. After removal of duplicates, K.F.P. excluded studies on the basis of the title and abstracts. Full texts were further evaluated for remaining studies and doubts surrounding study inclusion were resolved by discussion with a second reviewer. Independent reviews were conducted in randomly assigned three sets such that each study was systematically reviewed twice using the McMasters Critical Review Form for Quantitative Studies (Supplementary Appendix 2), developed by the McMaster University Occupations Therapy Evidence Based Practice Research Group.28 This assessment tool has been used in systematic reviews in multiple health care fields and is appropriate for this type of quantitative research.29–32 Of the eight sections of this tool, the section involving interventions did not apply to this review as the aim of this current systematic review was to identify studies reporting on outcome domains that are influenced as a result of the burn injury rather than to report on the influence of interventions on outcome domains. Two authors (K.F.P. and G.G.G.) reviewed the first set of 36 studies, two authors (C.A.R. and S.L.R.) reviewed the second set of 39 studies, and two authors (K.F.P. and E.M.K.) reviewed the third set of four studies. Each dyad discussed their individual reviews to reach a consensus. We used the Cochrane review methodology for data extraction.33 Any disagreements were later addressed by another reviewer through consulting McMasters Critical Review Guidelines, and bias limited through internal weekly checks by senior authors and a clear distinction between inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Classification of Instrument Subdomains Into Outcome Domains

We extracted subdomains assessed by each instrument utilized in each article and classified them into the applicable World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health – Child and Youth (ICF-CY) components (body structure and function, personal factors, activity and participation, and environmental factors). Relevant American Burn Association/Shriners Hospitals for Children Burn Outcomes Questionnaire 5–18 (BOQ 5–18) scales (pain, itch, appearance, emotional health, school reentry, upper extremity function, physical function and sports, transfers and mobility, and satisfaction with current state) were then matched to these ICF-CY components for classification into outcome domains. Further, the relevant subdomains of the Preschool1–5 LIBRE Conceptual Framework (gross motor, fine motor, internalizing, externalizing, dysregulation, trauma, toileting, play, connecting with family/peers, and friendships) were used to provide a foundation for outcome domains (Table 1). These outcome domains were further categorized into subdomains to present the results in a coherent manner. Outcome subdomains include the following: clinical symptoms (including pain, itch, sleep disturbance, height, or weight), physical resilience (ie, ability to recover quickly and maintain physical strength), internalizing behavior (including findings related to anxiety, depression, body image, and self-esteem), externalizing behavior (including findings related to defiance, aggression), psychological resilience (ie, ability to positively adapt or cope), school performance (including school re-entry, cognitive difficulties, and status/popularity), and interpersonal relations (including relationships with peers, siblings, parents, or strangers and social skills).

Table 1.

Linking outcomes to the relevant domains of previous conceptual frameworks

| ICF-CY | BOQ5–18 | Preschool LIBRE1–5 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Functioning | Body structure & function | Upper extremity function Pain Itch Transfers and mobility |

Gross motor Fine motor |

| Psychological Functioning | Personal factors | Appearance Satisfaction with current state Emotional health |

Internalizing Externalizing Dysregulation Trauma Toileting |

| Social Functioning | Activity and Participation Environmental factors |

Physical function and sports School reentry |

Play Connecting with family/peers Friendships |

RESULTS

Included Studies

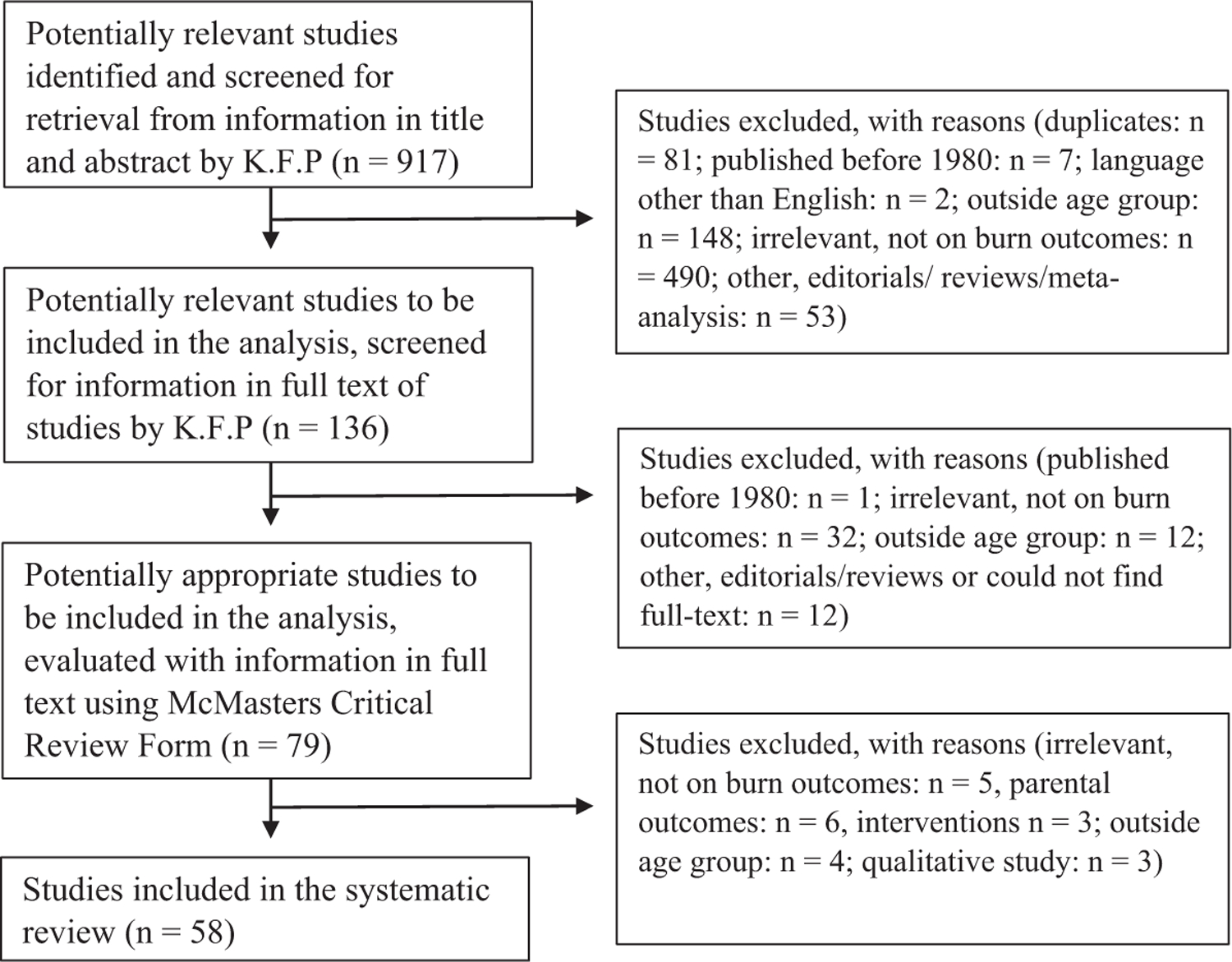

After screening titles and abstracts of 917 studies, 781 studies were excluded. Full texts were reviewed for the remaining 136 studies and 57 additional studies were excluded resulting in 79 potential studies. These studies were systematically reviewed using the McMasters critical review form, and after dyad discussions, 21 studies were further deemed ineligible, resulting in the final inclusion of 58 studies. Example studies that were excluded are studies with range and/or mean age of subjects outside of our intended population,34 studies reporting on parental outcomes,35 or studies aiming to understand the influence on outcomes following an intervention.36 Further reasons for exclusions at each step are given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of systematic selection of studies included in the review.

Study Characteristics

Studies were conducted in North America (n = 38), Europe (n = 18), South America (n = 1), and Oceania (n = 1). Sample sizes in the studies involved 6 to 678 burn survivors. Both patient- and parent-report measures were used in 23 studies. Results were compared to a reference group in 25 studies and 29 studies had no comparison group. Follow-up data were reported in 23 studies. Study design, type of measurement, mean age at time of assessment, mean burn size (% total body surface area burned, %TBSA), and assessed outcome domains are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Study characteristics of 58 studies assessing health outcomes in pediatric burn survivors

| Study Characteristics | Studies (n) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessed domain | Physical | 24 | 7,39,40–42,46,47,50–52,62,65,67,69–77,80,81 |

| Psychological | 47 | 37–55,57–68,73,75–80,82–90 | |

| Social | 29 | 37,40–42,44–46,48–50,52,53,55,56,61,62,64,73,75,78–80,85,88–93 | |

| Study design | Before-and-after | 2 | 92,93 |

| Case study | 3 | 7,66,71 | |

| Case-control | 7 | 43,46,68,70,84,88,91 | |

| Cohort | 14 | 37,39,47–49,52,55,72,74,76,77,81,85,91 | |

| Cross-sectional | 30 | 38,40–42,44,45,50,51,53,54,56–60,62–65,67,69,73,75,78–80,82,83,87,90 | |

| RCT | 2 | 61,86 | |

| Sample size | 0–20 | 6 | 42,43,46,60,72,88 |

| >20–50 | 15 | 37,41,54,57,59,61,66,70,75,79,80,82,89,90,92 | |

| >50–100 | 20 | 38,39,44,47,50,53,58,62–65,67–69,71,81,83,86,87,91 | |

| >100–200 | 9 | 7,40,45,51,55,56,73,77,84 | |

| >200–400 | 5 | 48,49,85,93 | |

| >400–600 | 2 | 73,75 | |

| >600 | 1 | 52 | |

| Mean age at time of assessment | 0–10 | 11 | 50,51,54,57,58,65,71–73,77,79 |

| 10–15 | 27 | 40,41,43,48,49,59,62–64,67,70,74,76,80–88,90,92,93 | |

| 15–20 | 6 | 47,55,68,69,89,91 | |

| Not available | 14 | 7,38,39,42,44–46,52,53,56,60,61,66,75,78 | |

| Mean %TBSA burned | 0–20% | 16 | 40,45,46,48,51,54,57,58,64,65,79,80,83,84,92 |

| >20–40% | 13* | 44,47,49,50,53,62,63,67–69,89,90,93 | |

| >40–60% | 8* | 7,55,61,71,72,74,81,86 | |

| >60–80% | 2 | 70,92 | |

| >80% | 2 | 41,42 | |

| Not available | 18 | 37,38,40,51,55,58–60,69,73,75–77,79,84,85,87,93 | |

| Type of measurement | Self-report | 41 | 7,37–39,41,42,46,47,49,56,58–63,65–68,71–76,78–90,92,93 |

| Parent-report | 38 | 37–45,47–55,57,58,60,62–66,74,75,77–80,82,83,85,87,89,92 | |

| Nurses/Clinicians/Teachers | 7 | 38,41,63,75,79,83,92 | |

| Medical Records | 5 | 46,65,70,71,91 | |

1 study reported mean TBSA for males and females separately, not together for all participants.

Outcome Domains and Instruments

Results were categorized into three outcome domains: physical functioning, psychological functioning, and social functioning. A total of 24 studies addressed physical functioning, 47 studies addressed psychological functioning, and 29 studies addressed social functioning. Results of some studies were specific to one outcome domain while others reported on health outcomes in multiple outcome domains. The summarized findings described in the subsections below cite each study that reported those findings. Across 58 studies, 107 different instruments were used to measure outcomes (Supplementary Appendix 3). Of these 107 instruments, only eight instruments were used in three or more studies: Child Behavior Checklist,37–46 Burn Outcomes Questionnaire (0–4, 5–18, or 11–18),47–53 Family Environment Scale,41,44,48,54–57 Youth Self Report,37–39,41,42,58 Piers-Harris Self Concept Scale,37,59–63 Strengths and Difficulties,39,53,62,64,65 Beck Depression Inventory,43,66,67 and Teacher Report Form.37,38,41

Physical Functioning

Impact of Clinical Symptoms

Significant loss of long-term bone density (P < .005) and below average height (P < .0001) was noted in severely burned children up to 5-year postburn measured through age-related bone mineral density z scores and height-for-age z scores, respectively.7,68,69 In another study, prevalence for below average height and weight decreased by 3-year postburn, indicating growth delay.70 Sleep disturbance was another common phenomenon where despite adequate sleep time, burn survivors had poorer quality of sleep.71 Moderately burned children had significantly lower pain thresholds (P = .02) while thresholds for severely burned children were not altered consistently.65 Pain coping styles were significantly different, with females seeking social support more than males (P = .01), and associated with age at time of burn injury and age at time of assessment.72 Pain is additionally correlated with itch intensity and while frequency and intensity decreased over time, symptoms were consistently reported at discharge, 6-, 12-, and 24-month postburn injury.73 Similarly, both females and children with a pre-existing comorbidity were found to be at a higher risk of experiencing itch symptoms.50,74 Additional factors associated with a higher risk of problems with pain and itch include severity of burn, presence of a facial burn, and length of hospital stay.50,52

Physical Resilience

Parents generally reported children as physically resilient, with optimal functioning in mobility, self-care, and usual activities of play and leisure.41,47,51,62 Severely burned children and their parents reported that children were more active at an average of 5-year follow-up after burn injury with children also reporting fewer health problems.37 Functional independence significantly improved from admission to discharge and remained consistent at 3- and 6-month postburn (P = .000) at all time points.75,76 Mean weight-for-age from pre-injury to follow up at 1.5 years also improved significantly (P = .03) for severely burned children compared to a reference sample.7,68

On the other hand, larger burn size significantly impacted upper extremity functioning compared to smaller burn size.51 The risk of functional limitations in upper extremity and sports increased with the presence of visible scars.50 According to parental reports, physical impairment, especially right lower extremity impairment, was found to correlate negatively (r = −0.76, P = .02) with organized activities and athletics.42 Athletic competence was significantly lower (P = .033) than the non-burned sample.46 Lower scores were also reported on scales related to freedom of movement and self-help activities compared to non-burned samples.74

Psychological Functioning

Clinical Symptoms

The prevalence of clinical symptoms was reported in 14 studies with difficulties reported by combinations of self-, parent-, and teacher-reports in internalizing behaviors, externalizing behaviors, cognitive difficulties, and phobias.39,43,45,47,51,55,57,60,63,64,77–80 Depending on the informant, prevalence ranged from 6% to 87%. Sleep disorders manifested as nightmares, sleepwalking, bed-wetting, and daytime naps with nightmares persisting 6.9 years postburn injury.81 Additionally, PTSS was highly prevalent, and present at follow-up time points with mixed results.60,79 High PTSS prevalence was significantly predicted by longer time since burn injury (P < .05), more use of distraction coping strategy (P = .04), dissociation, more severe burn, and more preburn conflict with family.82,83 Alternatively, fewer symptoms were reported by children with maternal supervision at time of burn injury.79

Internalizing Behavior

Anxiety and Depression

Parents of older children reported higher anxiety in their children during hospital stay compared to parents of younger children at time of assessment.44 Additionally, anxiety was noted in children of all ages awaiting surgery with behaviors such as attachment, wishing to go home, sweating, crying, complaints, and stiffness.44 On the other hand, young survivors and females reported experiencing higher levels of anxiety compared to older survivors and males.84 Internalizing behaviors noted in survivors with burns to critical areas (ie, burns to hands, face, feet, and/or genitalia area) included loneliness, solitariness, social isolation, and reduced heterosexual contact.78

Body Image and Self-esteem

Body image scores were mixed between sexes with one study reporting better scores for females while another reported worse scores.67,85 Extremely high anxiety was initially reported when evaluating self-image.60 Survivors with severe burns experience problems with appearance scores and satisfaction with current state.51 Compared to non-burned populations, worse body image scores were reported in children with burns until 5-years post-injury.47,50,86 Body esteem and appearance scores correlated with perceived stigma, social comfort, and conflict with family.48,85 Higher number of scars resulted in significantly decreased scores (P < .001) for physical appearance59 and happiness, satisfaction, and emotional adjustment.53,59 Parents underreported their children’s perceived stigmatization compared to self-reports (P = .01).87 Burn survivors reported significantly better scores in perceived appearance (P = .018), satisfaction with weight (P = .001), and general feelings about self-appearance compared to an age-matched population.67

In some studies, there were no sex differences in self-esteem,59,62 whereas in other studies, males had better self-esteem in behavior (P < .001), intellectual abilities (P < .05), and physical appearance (P < .05).37 Compared to age-matched pediatric cancer sample, burn survivors reported significantly poorer perceived physical appearance.62 Scarring and appearance influenced HRQL with children reporting lower HRQL62 and parents of younger children reporting problems with sexual identity.38 Self-worth was significantly lower (P = .007) and importance of physical appearance was rated higher than level of personal competence in half of the participants.46 On the other hand, few studies reported no impact on self-image or sexual development compared with non-burned children.44,88 Additionally, physical appearance and mood highly correlated with global self-esteem in burn survivors compared to a normative sample.46 In contrast, global self-worth was higher in burned children compared to non-burned children.61

Externalizing Behavior

Significant increases in externalizing behavior were noted for children with burn injuries by parents compared to nonburned populations.38,61,64,65 On the other hand, no significant differences in behavioral problems between non-burned children and children with >80% burns was reported by parent-, teacher-, and self-reports.41. Regardless of sex, behavior problems included somatic complaints (P < .01), aggression (P < .01), delinquent behavior (P < .05), as well as being more moody (P < .05) and demanding (P < .01).38 These same behaviors were noted by teachers in older boys. Parental ratings appeared to be influenced by child’s preburn functioning.39 Fewer conduct problems and hyperactivity-inattention were reported by females.62

One significant factor related to problematic behavior was age (P < .05) as noted in self-report measures.58,78 Sex, visibility of scars, burn etiology (flame) in older burn survivors, and preburn behavior correlated with problematic behaviors such as attention deficit and aggressive behaviors as noted in parent reports.45,53,74 A greater frequency of externalizing behavior such as temper tantrums, irritability, disobedience, and hyperactivity were noted in females by parents, teachers, and children themselves compared to male burn survivors.74,78 Those with significantly more behavior problems displayed maladaptive behavior, used fewer coping skills, were emotionally distanced from problems, and participated less in recreational activities.55,89 On the other hand, the number of problematic behaviors were not impacted by physical impairment and these patients were as competent as the reference group.42

Psychological Resilience

Levels of extraversion and emotional stability was significantly higher (P < .01) as reported by adolescents in a study comparing findings to a non-burned population.58,78 These personality strengths were also related to lower depression rates and less hostility.90 Psychological adjustments and cognitive improvements were noted at multiple follow-up time points across several studies.43,49,54,60,75,76,78 In other studies, while burn survivors displayed worse functioning at initial follow-up, generic HRQL was comparable to a pediatric population with an injury unrelated to burns at a later follow-up date.51,60 Significantly poorer HRQL (P < .001) was noted in cognitive, behavioral and emotional functioning, and psychosocial health for females and participants with increasing number of reported symptoms.62,67,79 Age at time of burn injury predicted HRQL at follow-up, with younger children having better HRQL.40,52 Additionally, extraversion and emotional stability was related to psychological adjustment after a severe burn injury.90 Parents, teachers, and severely burned children reported equal competency in a sample compared to a normative group with no statistically significant difference between physical functioning and social competence.41

Social Functioning

School Performance

The average time in returning to school varied among different studies ranging from 9 days to 182 days.91–93 School performance ratings by children, teachers, and/or parents were mixed for concerns regarding externalizing behavior, concentration problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity, prosocial skills, peer problems, and overall social functioning.37,41,53,62,64,77,79,93 Studies also indicated higher presence of school avoidance, adjustments to peer reactions (P < .01), worse intellectual and school status (P = .005) and popularity (P = .003), more bullying (P < .05), and reduced integration with peers and teachers (P < .0001) during school reentry.48,61,64,72,74,78,93 Factors associated with longer time before return to school included sex (male), age, length of hospital stay, living in rural areas, presence of visible scar, parental self-confidence and confidence in their child and child’s school, and school receptivity 50,91.

Interpersonal Relations

Interpersonal social interactions for this age group worsens postburn injury, impacting peer relations, domestic and community adjustment skills, perceived stigma, and social comfort.85,89 Burn survivors were more active and socially outgoing, and were found to have high social integration scores within school, home, and peer group—demonstrating a significantly higher self-regard (P = .03), social acceptance (P = .03), social competence (P = .002), and adjustment skills compared to an age-matched group without burns.37,46,61,90 One study also reported no significant difference in inter-personal relationships.66 Alternatively, parents and children additionally reported that physical impairment impacted involvement in organized and recreational activities such as athletics outside of school.42 Furthermore, more males self-reported having friends of the opposite sex and fewer parents reported females visiting friends outside of school regardless of sex.74 While one study noted no differences in regards to sexual development compared to non-burned adolescents,88 another study reported that burns to critical areas significantly impacted heterosexual interaction and social isolation.78

DISCUSSION

The principal outcome domains mentioned in this systematic review (physical, psychological, and social functioning) support and integrate well into the three frameworks for a comprehensive overview of burn outcomes in children and adolescents 5 to 18 years of age. These three outcome domains were linked to existing frameworks of ICF-CY, BOQ5–18, and Preschool LIBRE1–5 to guide the development of new conceptual frameworks for burn-specific instruments in this age group. For example, studies in this review that reported on internalizing behaviors (ie, anxiety or depression) could be based in BOQ5–18 and Preschool LIBRE1–5 as “emotional health” and “internalizing” outcomes, respectively. Further, ICF-CY would define internalizing behaviors under “personal factors” comprising coping styles and overall behavior pattern. Another example is social domain, represented in Preschool LIBRE1–5 as “connecting with family/peers” subdomain under social functioning, in BOQ5–18 as “school reentry,” and in ICF-CY as “support and relationships” under environmental factors. Additionally, only eight of the 107 outcome instruments were utilized in three or more studies and only one using the BOQ was burn-specific. This broad range of generic assessment tools with differing validity and reliability can indicate that generic measures may not capture the granularity of burn-specific assessments. Although the BOQs are widely used, the length of the legacy measures may not always be practical for clinical use and the content covered does not adequately address the wide range of growth and development during the formative years. A more granular instrument may be better suited to assess outcomes given that the domains that we selected point to a foundation in the ICF-CY, BOQ5–18 and Preschool LIBRE1–5.

HRQL in pediatric burn survivors was comparable to other pediatric injuries 24-months postburn injury with improved recovery rates in adolescents compared to children.51,52 Although physical functioning improved at follow-up in some studies,7,37,68,75,76 physical impairments still pose a risk to a burn survivor’s height and weight growth as well as ability to participate in organized activities and influence on social interactions.42 In order to minimize this risk, it is important to understand factors that influence physical outcomes. While variables such as sex and burn size did not contribute significantly to the prediction of HRQL, general health, or functional independence,40,66,73 higher number of clinical symptoms, severity of re-experiencing symptoms, use of avoidance/numbing coping strategies, arousal symptoms, and amputations were factors associated with significantly worse HRQL (P < .05).41,79 Furthermore, females were more likely to seek social support for pain and were at a higher risk for itch problems. Multidisciplinary inpatient rehabilitation efforts are recommended to improve overall functioning scores across all three outcome domains.75

Physical impairments were associated with psychological and social functioning in several studies.42,55,89 Factors that were noted to significantly impact physical functioning including pain and itch45,72,73 and athletic competence.42,46 Visible scars,50,53,59,93 body image satisfaction,46,63,74,86 peer relations,38,46,61,62,64,74,78,90,93 and adjustment skills55,58,62,72,82,89 are factors impacting psychological functioning. Compared to non-burned population, burn survivors exhibit high rates of anxiety,43–45,51,57,60,63,74,78,84 PTSS,39,59,60,79 depression,43,51,57,63,74,78,80 and cognitive difficulties43,74,77,79 as well as low body image satisfaction.47,50,59,60,67,85,86 This remained consistent regardless of self-report or proxy-report measures. Parents of children with severe burns reported that their children were also less compliant, less satisfied with current state and had more emotional and behavior problems compared to children with minor burns.50,53 Furthermore, mixed findings were reported for outcomes such as physical competence,42,46,75,76 conduct problems,38,41,62,74,78 and interpersonal social interactions42,66,85,89 across multiple studies. Alternatively, few studies also reported no differences in social outcomes compared to non-burn populations.40,41,59 These discrepant findings across these domains in multiple studies warrant further research.

Similar to physical functioning studies, psychological functioning studies had mixed findings on factors that influenced outcomes. Age, sex, severity of burn, and burn etiology (flame and thermal) correlated with higher levels of anxiety,44,45,65,72,74,78,84 whereas in other studies, burn size, presence of functional or aesthetic sequelae, and visibility of scars were not associated with depression or self-esteem.57,66,80 Furthermore, while females had significantly lower body image scores in some studies,60,67,84,85 mixed findings on appearance and self-esteem scores in other studies warrant additional research.44,46,61,62,88 While many studies reported poor functioning,40,43–45,47,49–53,57,62,65,72,74,77,78,80,84,87,89 this is not to say that psychological and social functioning is less likely to improve. One study reported potential improvement in adult burn survivors after receiving cognitive behavioral therapy. Adequate psychological and social support (both for burn survivor and family) such as counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy or social skills training, or education on the importance of active coping strategies as well as management of unpleasant social experiences can enhance psychological adjustment and help burn survivors meet developmental challenges.38–44,48,49,54,55,58,60–62,66,67,82,83,86,88,90

Erikson’s stages described earlier are accentuated in pediatric burn survivors as emotional dysregulation and maladaptive coping strategies enable behavioral problems that negatively influence social interactions.51,58 Social ramifications for pediatric burn survivors postburn injury worsen recovery and increase long-term health consequences.16,17 Furthermore, detriments in social functioning can exacerbate existing symptoms of depression, anxiety, and body image due to changes in appearance resulting from the burn injury. The complexities associated with a burn injury warrant a need for effective and early intervention to ensure positive resolutions at each stage of psychosocial development and reduce adverse health outcomes.94,95 In order to overcome these challenges, burn survivors are often encouraged to engage in their community where positive interactions with peers can facilitate social functioning.96 For example, acceptance by teachers and schoolmates, independence, family dynamics, and involvement in social or organizational activities were factors associated with better psychological and social outcomes.44,50,55,56,78 Well-adjusted burn survivors also tended to be more adventurous, socially congenial, less cautious, and less shy.

During the recovery process, family dynamics pre- and postburn, such as sibling relationships, parenting style, or presence/lack of community support are vital in understanding the psychological adjustment of children following a burn injury. For example, a study by Liber et al (2006) reported family’s level of control to significantly correlate with children’s internalizing symptoms (P < .05)57 and preburn conflict with family predicted high PTSS prevalence.82,83 Alternatively, maternal supervision at time of burn injury resulted in fewer child-reported symptoms.79 In another study, increased independence among family as related to assertiveness, self-sufficiency, and making own decisions was associated with a decrease in parental concern or stress (P < .05).48 Additionally, caregiver anxiety and depression significantly moderated children’s use of distractive coping strategies and PTSS (P = .02)82 and poorer maternal psychological and social adjustment reflected poor behavioral adjustment in children (P = .004).55,90 Poor behavioral adjustment in burn survivors was also impacted by mothers who participated in few recreational activities.90

If a caregiver is unable to cope with the child’s burn injury, it can indirectly impact psychological and social outcomes in burn survivors. Caregivers may also unintentionally model maladaptive coping strategies that can worsen HRQL. Sheridan and colleagues (2012) previously associated negative reaction to self-appearance with increased conflict between family members.48 In order to balance parental outcomes from influencing the well-being of young burn survivors, educating parents on the importance of active coping and promoting emotional stability during rehabilitation can reduce externalizing and internalizing behaviors in burn survivors.58,72 As reporting upon family functioning was beyond the scope of our current aims, future reviews should consider the role of family cohesion or disruption on long-term outcomes of pediatric burn survivors.

This review allows burn care providers and researchers to understand the clinical impact of a traumatic event on health and functioning, and shed light on research that has been previously conducted, especially in this age range where large developmental changes occur. The findings of this review showed fewer innovative studies in physical and social domains, whereas further research is required across all three domains to address inconclusive findings. However, with the comprehensive strength of this review are limitations that need to be acknowledged. A significant discrepancy noted in the literature during this review includes the age range. Studies were often conducted in various age groups (ie, 0–18, 5–12, 5–18, 6–18, etc.). There were also inconsistencies in reporting age at burn injury and age at time of assessment. Additionally, some studies failed to describe their population, making it difficult to frame findings in terms of time since burn injury. A second limitation includes the use of inconsistent language across the literature for comparison groups. For example, terms such as “non-burn survivors,” “healthy controls,” “age-matched group,” “reference group,” “normal population,” and so on were used across studies. We believe consistency in defining comparison groups is important to compare findings across studies and draw conclusions that can be clinically important. It is also necessary to compare findings to preburn levels in order to better understand postburn adjustment. Further, this is important in order to attribute findings to burn injury rather than normative development or normal changes in an individual’s life unrelated to the burn injury.

Similarly, few instruments were used across multiple studies. The lack of common data elements for measurements results in further difficulties in comparing findings. A future burn-specific computer adaptive test (CAT) using advanced psychometrics can be tailored for selected items relevant to each respondent on a common metric based on a large item bank with a solid foundation to measure recovery of burn survivors. A future aim of this review is the development of such conceptual model frameworks that contributes to the Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation (LIBRE) project for the creation of the age-specific LIBRE measurements: School-Aged LIBRE5–12 and Teen-Aged LIBRE12–18– CAT Profile.97–99

Another potential limitation is that the majority of studies utilized a cross-sectional study design. While this was appropriate considering the nature of the study (to explore the impact of burn injury on a particular outcome), cohort study designs with longer follow-ups, and advanced statistical analyses can further help evaluate developmental changes in burn survivors compared to age-matched populations. Additionally, biases that were most noted in the included studies were recall bias and sample bias. This study frames outcomes depending on self-report or parent-report, and future reviews should focus on whether there is agreement between different types of reports. Lastly, the aim of this systematic review is to comprehensively document and describe clinical outcomes and not to synthesize data on the recovery/rehabilitation process or other study factors that presumably may contribute to reported findings (such as the influence of attrition rates on improvements or selection bias related to participation). Therefore, we did not include a quality assessment of studies and only reported on the nature and description of unique outcomes.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review demonstrates the importance of understanding the convergence of burn injuries and long-term outcomes related to physical and psychological health as well as social status. Further research in this age group warrants long-term follow-up to address mixed findings within each domain impacted by the burn injury. Furthermore, the current review provides the basis for future studies aimed at guiding cohesive burn-specific assessments targeting age groups to account for developmental changes. Clinical implications include promoting use of coping strategies, multidisciplinary rehabilitation, and adequate social/family support to further improve adjustment processes by refining care at the individual level to optimize treatment.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This work was supported by Shriners Hospitals for Children (Grant #72000-BOS-18 and #79145-BOS-20) Partial support was obtained from the Fraser Fund at the Massachusetts General Hospital and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (Grant #90DPBU0001). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this manuscript do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Burn Association, Committee NBRA. National Burn Repository 2017 Update. Am Burn Assoc 2017;60606(312):1–141. http://ameriburn.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2017_aba_nbr_annual_report-1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catalyst N What is patient-centered care? 2017. 10.1056/CAT.17.0559. [DOI]

- 3.ISOQOL. What is QOL? 2019. https://www.isoqol.org/what-is-qol/. Accessed June 19, 2021.

- 4.Levi B, Jayakumar P, Giladi A, et al. Risk factors for the development of heterotopic ossification in seriously burned adults: a National Institute on Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research burn model system database analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;79:870–6. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeschke MG, Chinkes DL, Finnerty CC, et al. Pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. Ann Surg 2008;248:387–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter C, Herndon DN, Sidossis LS, Børsheim E. The impact of severe burns on skeletal muscle mitochondrial function. Burns 2013;39:1039–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prelack K, Dwyer J, Dallal GE, et al. Growth deceleration and restoration after serious burn injury. J Burn Care Res 2007;28:262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAleavey AA, Wyka K, Peskin M, Difede J. Physical, functional, and psychosocial recovery from burn injury are related and their relationship changes over time: a Burn Model System study. Burns 2018;44:793–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esselman PC, Askay SW, Carrougher GJ, et al. Barriers to return to work after burn injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88(12 Suppl 2):S50–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenberg M, Mehta N, Rosenberg L, et al. Immediate and long-term psychological problems for survivors of severe pediatric electrical injury. Burns 2015;41:1823–1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erikson EH. Childhood and Society New York: Norton; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svetina M Resilience in the context of Erikson’s theory of human development. Curr Psychol 2014;33:393–404. doi: 10.1007/s12144-014-9218-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell FA, Pungello EP, Burchinal M, et al. Adult outcomes as a function of an early childhood educational program: an Abecedarian Project follow-up. Dev Psychol 2012;48:1033–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meng F, Zuo KJ, Amar-Zifkin A, Baird R, Cugno S, Poenaru D. Pediatric burn contractures in low- and lower middle-income countries: a systematic review of causes and factors affecting outcome. Burns 2020;46:993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cleary M, Kornhaber R, Thapa DK, West S, Visentin D . A quantitative systematic review assessing the impact of burn injuries on body image. Body Image 2020;33:47–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Padalko A, Cristall N, Gawaziuk JP, Logsetty S. Social complexity and risk for pediatric burn injury: a systematic review. J Burn Care Res 2019;40:478–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szabo MM, Ferris KA, Urso L, Aballay AM, Duncan CL. Social competence in pediatric burn survivors: a systematic review. Rehabil Psychol 2017;62:69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mason ST, Esselman P, Fraser R, Schomer K, Truitt A, Johnson K. Return to work after burn injury: a systematic review. J Burn Care Res 2012;33:101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wasiak J, McMahon M, Danilla S, Spinks A, Cleland H, Gabbe B. Measuring common outcome measures and their concepts using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in adults with burn injury: a systematic review. Burns 2011;37:913–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hornsby N, Blom L, Sengoelge M. Psychosocial interventions targeting recovery in child and adolescent burns: a systematic review. J Pediatr Psychol 2020;45:15–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kornhaber R, Visentin D, Kaji Thapa D, et al. Burn camps for burns survivors—Realising the benefits for early adjustment: a systematic review. Burns 2020;46:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flores O, Tyack Z, Stockton K, Ware R, Paratz JD. Exercise training for improving outcomes post-burns: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil 2018;32:734–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi KJ, Williams EA, Pham CH, et al. Fractional CO2 laser treatment for burn scar improvement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Burns 2021;47:259–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mudawarima T, Chiwaridzo M, Jelsma J, Grimmer K, Muchemwa FC. A systematic review protocol on the effectiveness of therapeutic exercises utilised by physiotherapists to improve function in patients with burns. Syst Rev 2017;6:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ault P, Plaza A, Paratz J. Scar massage for hypertrophic burns scarring-A systematic review. Burns 2018;44:24–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gittings PM, Grisbrook TL, Edgar DW, Wood FM, Wand BM, O’Connell NE. Resistance training for rehabilitation after burn injury: a systematic literature review & meta-analysis. Burns 2018;44:731–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenkinson E, Williamson H, Byron-Daniel J, Moss TP. Systematic review: psychosocial interventions for children and young people with visible differences resulting from appearance altering conditions, injury, or treatment effects. J Pediatr Psychol 2015;40:1017–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Law M, Stewart N, Pollock D, et al. Guidelines for critical review form - quantitative studies. Guidel Crit Rev Form - Quant Stud 1998;1–11.

- 29.Fisher A, Lennon S, Bellon M, Lawn S. Family involvement in behaviour management following acquired brain injury (ABI) in community settings: a systematic review. Brain Inj 2015;29:661–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egan M, Hobson S, Fearing VG. Dementia and occupation: a review of the literature. Can J Occup Ther 2006;73:132–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cranage S, Perraton L, Bowles KA, Williams C. The impact of shoe flexibility on gait, pressure and muscle activity of young children. A systematic review. J Foot Ankle Res 2019;12:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryall T, Judd BK, Gordon CJ. Simulation-based assessments in health professional education: a systematic review. J Multidiscip Healthc 2016;9:69–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Starr M, Chalmers I, Clarke M, Oxman AD. The origins, evolution, and future of The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2009;25 Suppl 1:182–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orr DA, Reznikoff M, Smith GM. Body image, self-esteem, and depression in burn-injured adolescents and young adults. J Burn Care Rehabil 1989;10:454–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blakeney P, Moore P, Broemeling L, et al. Parental stress as a cause and effect of pediatric burn injury. J Burn Care Rehabil 1993;14:73–9. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199301000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arshad SN, Gaskell SL, Baker C, et al. Measuring the impact of a burns school reintegration programme on the time taken to return to school: a multi-disciplinary team intervention for children returning to school after a significant burn injury. Burns 2015;41:727–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blakeney P, Meyer W, Moore P, et al. Psychosocial sequelae of pediatric burns involving 80% or greater total body surface area. J Burn Care Rehabil 1993;14:684–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blakeney P, Meyer W, Moore P, et al. Social competence and behavioral problems of pediatric survivors of burns. J Burn Care Rehabil 1993;14:65–72. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199301000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egberts MR, van de Schoot R, Boekelaar A, Hendrickx H, Geenen R, Van Loey NE. Child and adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems 12 months postburn: the potential role of preburn functioning, parental posttraumatic stress, and informant bias. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2016;25:791–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Landolt MA, Grubenmann S, Meuli M. Family impact greatest: predictors of quality of life and psychological adjustment in pediatric burn survivors. J Trauma 2002;53:1146–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyers-Paal R, Blakeney P, Robert R, et al. Physical and psychologic rehabilitation outcomes for pediatric patients who suffer 80% or more TBSA, 70% or more third degree burns. J Burn Care Rehabil 2000;21(1 Pt 1):43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore P, Moore M, Blakeney P, Meyer W, Murphy L, Herndon D. Competence and physical impairment of pediatric survivors of burns of more than 80% total body surface area. J Burn Care Rehabil 1996;17(6 Pt 1):547–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nayeb-Hashemi N, Rosenberg M, Rosenberg L, et al. Skull burns resulting in calvarial defects: cognitive and affective outcomes. Burns 2009;35:237–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Delgado Pardo G, Moreno García I, Marrero FR, Gómez Cía T. Psychological impact of burns on children treated in a severe burns unit. Burns 2008;34:986–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Delgado Pardo G, García IM, Gómez-Cía T. Psychological effects observed in child burn patients during the acute phase of hospitalization and comparison with pediatric patients awaiting surgery. J Burn Care Res 2010;31:569–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robert R, Meyer W, Bishop S, Rosenberg L, Murphy L, Blakeney P. Disfiguring burn scars and adolescent self-esteem. Burns 1999;25:581–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pan R, Egberts MR, Nascimento LC, et al. Health-related quality of life in adolescent survivors of burns: agreement on self-reported and mothers’ and fathers’ perspectives. Burns 2015;41:1107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheridan RL, Lee AF, Kazis LE, et al. ; Multi-Center Benchmarking Study Working Group. The effect of family characteristics on the recovery of burn injuries in children. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73(3 Suppl 2):S205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stubbs TK, James LE, Daugherty MB, et al. Psychosocial impact of childhood face burns: a multicenter, prospective, longitudinal study of 390 children and adolescents. Burns 2011;37:387–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sveen J, Sjöberg F, Öster C. Response to letter to the editor: ‘sleep quality implicates in life quality: an analysis about children who suffered burns.’ Burns 2014;40:775–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Baar ME, Polinder S, Essink-Bot ML, et al. Quality of life after burns in childhood (5–15 years): children experience substantial problems. Burns 2011;37:930–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Warner P, Stubbs TK, Kagan RJ, et al. ; Multi-Center Benchmarking Study Working Group. The effects of facial burns on health outcomes in children aged 5 to 18 years. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73(3 Suppl 2):S189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willebrand M, Sveen J, Ramklint MD, Bergquist RN, Huss MD, Sjöberg MD. Psychological problems in children with burns–parents’ reports on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Burns 2011;37:1309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blakeney P, Portman S, Rutan R. Familial values as factors influencing long-term psychological adjustment of children after severe burn injury. J Burn Care Rehabil 1990;11:472–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Browne G, Byrne C, Brown B, et al. Psychosocial adjustment of burn survivors. Burns Incl Therm Inj 1985;12:28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Byrne C, Love B, Browne G, Brown B, Roberts J, Streiner D. The social competence of children following burn injury: a study of resilience. J Burn Care Rehabil 1986;7:247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liber JM, List D, Van Loey NE, Kef S. Internalizing problem behavior and family environment of children with burns: a Dutch pilot study. Burns 2006;32:165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liber JM, Faber AW, Treffers PD, Van Loey NE. Coping style, personality and adolescent adjustment 10 years post-burn. Burns 2008;34:775–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abdullah A, Blakeney P, Hunt R, et al. Visible scars and self-esteem in pediatric patients with burns. J Burn Care Rehabil 1994;15:164–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beard SA, Herndon DN, Desai M. Adaptation of self-image in burn-disfigured children. J Burn Care Rehabil 1989;10:550–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.LeDoux JM, Meyer WJ, Blakeney P, Herndon D. Positive self-regard as a coping mechanism for pediatric burn survivors. J Burn Care Rehabil 1996;17:472–6; discussion 471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maskell J, Newcombe P, Martin G, Kimble R. Psychosocial functioning differences in pediatric burn survivors compared with healthy norms. J Burn Care Res 2013;34:465–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saxe G, Stoddard F, Chawla N, et al. Risk factors for acute stress disorder in children with burns. J Trauma Dissociation 2005;6:37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Phillips C, Rumsey N. Considerations for the provision of psychosocial services for families following paediatric burn injury–a quantitative study. Burns 2008;34:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wollgarten-Hadamek I, Hohmeister J, Demirakça S, Zohsel K, Flor H, Hermann C. Do burn injuries during infancy affect pain and sensory sensitivity in later childhood? Pain 2009;141:165–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nicolosi JT, de Carvalho VF, Sabatés AL, Paggiaro AO. Assessment of health status of adolescent burn victims undergoing rehabilitation: a cross-sectional field study. Plast Surg Nurs 2013;33:185–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pope SJ, Solomons WR, Done DJ, Cohn N, Possamai AM. Body image, mood and quality of life in young burn survivors. Burns 2007;33:747–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klein GL, Herndon DN, Langman CB, et al. Long-term reduction in bone mass after severe burn injury in children. J Pediatr 1995;126:252–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Klein GL, Langman CB, Herndon DN. Vitamin D depletion following burn injury in children: a possible factor in post-burn osteopenia. J Trauma 2002;52:346–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rutan RL, Herndon DN. Growth delay in postburn pediatric patients. Arch Surg 1990;125:392–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gottschlich MM, Jenkins ME, Mayes T, et al. The 1994 Clinical Research Award. A prospective clinical study of the polysomnographic stages of sleep after burn injury. J Burn Care Rehabil 1994;15:486–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rimmer RB, Alam NB, Bay RC, Sadler IJ, Foster KN, Caruso DM. The reported pain coping strategies of pediatric burn survivors-does a correlation exist between coping style and development of anxiety disorder? J Burn Care Res 2015;36:336–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schneider JC, Nadler DL, Herndon DN, et al. Pruritus in pediatric burn survivors: defining the clinical course. J Burn Care Res 2015;36:151–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rivlin E, Faragher EB. The psychological sequelae of thermal injury on children and adolescents: part 1. Dev Neurorehabil 2007;10:161–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Luce JC, Mix J, Mathews K, et al. Inpatient rehabilitation experience of children with burn injuries: a 10-yr review of the uniform data system for medical rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2015;94:436–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Disseldorp LM, Niemeijer AS, Van Baar ME, Reinders-Messelink HA, Mouton LJ, Nieuwenhuis MK. How disabling are pediatric burns? Functional independence in Dutch pediatric patients with burns. Res Dev Disabil 2013;34:29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Andersson G, Sandberg S, Rydell AM, Gerdin B. Social competence and behaviour problems in burned children. Burns 2003;29:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rivlin E, Faragher EB. The psychological effects of sex, age at burn, stage of adolescence, intelligence, position and degree of burn in thermally injured adolescents: Part 2. Dev Neurorehabil 2007;10:173–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Landolt MA, Buehlmann C, Maag T, Schiestl C. Brief report: quality of life is impaired in pediatric burn survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Pediatr Psychol 2009;34:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stoddard FJ, Stroud L, Murphy JM. Depression in children after recovery from severe burns. J Burn Care Rehabil 1992;13:340–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kravitz M, McCoy BJ, Tompkins DM, et al. Sleep disorders in children after burn injury. J Burn Care Rehabil 1993;14:83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Enlow PT, Brown Kirschman KJ, Mentrikoski J, et al. The role of youth coping strategies and caregiver psychopathology in predicting posttraumatic stress symptoms in pediatric burn survivors. J Burn Care Res 2019;40:620–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hall E, Saxe G, Stoddard F, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in parents of children with acute burns. J Pediatr Psychol 2006;31:403–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rimmer RB, Bay RC, Sadler IJ, Alam NB, Foster KN, Caruso DM. Parent vs burn-injured child self-report: contributions to a better understanding of anxiety levels. J Burn Care Res 2014;35:296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lawrence JW, Rosenberg LE, Fauerbach JA. Comparing the body esteem of pediatric survivors of burn injury with the body esteem of an age-matched comparison group without burns. Rehabil Psychol 2007;52:370–9. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jessee PO, Strickland MP, Leeper JD, Wales P. Perception of body image in children with burns, five years after burn injury. J Burn Care Rehabil 1992;13:33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lawrence JW, Rosenberg L, Mason S, Fauerbach JA. Comparing parent and child perceptions of stigmatizing behavior experienced by children with burn scars. Body Image 2011;8:70–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Robert RS, Blakeney PE, Meyer WJ 3rd. Impact of disfiguring burn scars on adolescent sexual development. J Burn Care Rehabil 1998;19:430–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meyer WJ 3rd, Blakeney P, LeDoux J, Herndon DN. Diminished adaptive behaviors among pediatric survivors of burns. J Burn Care Rehabil 1995;16:511–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Moore P, Blakeney P, Broemeling L, Portman S, Herndon DN, Robson M. Psychologic adjustment after childhood burn injuries as predicted by personality traits. J Burn Care Rehabil 1993;14:80–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Christiansen M, Carrougher GJ, Engrav LH, et al. Time to school re-entry after burn injury is quite short. J Burn Care Res 2007;28:478–81; discussion 482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Staley M, Anderson L, Greenhalgh D, Warden G. Return to school as an outcome measure after a burn injury. J Burn Care Rehabil 1999;20(1 Pt 1):91–4; discussion 90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rimmer RB, Foster KN, Bay CR, et al. The reported effects of bullying on burn-surviving children. J Burn Care Res 2007;28:484–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bakker A, Maertens KJ, Van Son MJ, Van Loey NE. Psychological consequences of pediatric burns from a child and family perspective: a review of the empirical literature. Clin Psychol Rev 2013;33:361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pond JS, Peters ML, Pannell DL, Rogers CS. Psychosocial challenges for children with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Educ 1995;21:297–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pan R, Dos Santos BD, Nascimento LC, Rossi LA, Geenen R, Van Loey NE. School reintegration of pediatric burn survivors: an integrative literature review. Burns 2018;44:494–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brady KJS, Grant GG, Stoddard FJ, et al. Measuring the impact of burn injury on the parent-reported health outcomes of children 1 to 5 years: a conceptual framework for development of the preschool life impact burn recovery evaluation profile cat. J Burn Care Res 2020;41:84–94. doi: 10.1093/jbcr/irz110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Grant GG, Brady KJS, Stoddard FJ, et al. Measuring the impact of burn injury on the parent-reported health outcomes of children 1-to-5 years: item pool development for the Preschool1–5 Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation (LIBRE) Profile. Burns 2021;47:1511–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kazis LE, Marino M, Ni P, et al. Development of the life impact burn recovery evaluation (LIBRE) profile: assessing burn survivors’ social participation. Qual Life Res 2017;26:2851–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.