Abstract

Two novel Enterococcus faecalis-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors that utilize the promoter and ribosome binding site of bacA on the E. faecalis plasmid pPD1 were constructed. The vectors were named pMGS100 and pMGS101. pMGS100 was designed to overexpress cloned genes in E. coli and E. faecalis and encodes the bacA promoter followed by a cloning site and stop codon. pMGS101 was designed for the overexpression and purification of a cloned protein fused to a Strep-tag consisting of 9 amino acids at the carboxyl terminus. The Strep-tag provides the cloned protein with an affinity to immobilized streptavidin that facilitates protein purification. We cloned a promoterless β-galactosidase gene from E. coli and cloned the traA gene of the E. faecalis plasmid pAD1 into the vectors to test gene expression and protein purification, respectively. β-Galactosidase was expressed in E. coli and E. faecalis at levels of 103 and 10 Miller units, respectively. By cloning the pAD1 traA into pMGS101, the protein could be purified directly from a crude lysate of E. faecalis or E. coli with an immobilized streptavidin matrix by one-step affinity chromatography. The ability of TraA to bind DNA was demonstrated by the DNA-associated protein tag affinity chromatography method using lysates prepared from both E. coli and E. faecalis that overexpress TraA. The results demonstrated the usefulness of the vectors for the overexpression and cis/trans analysis of regulatory genes, purification and copurification of proteins from E. faecalis, DNA binding analysis, determination of translation initiation site, and other applications that require proteins purified from E. faecalis.

Enterococcus faecalis is a gram-positive bacterium that inhabits the human intestine and is frequently associated with urinary tract infections, biliary infections, bacteremia, and endocarditis. E. faecalis commonly harbors mobile elements that confer resistance to antibiotics, including vancomycin (3). It is a significant nosocomial pathogen and is an emerging clinical problem because of the widespread antibiotic resistance of pathogens, including vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

Several complex genetic networks have been reported in enterococci (2, 21, 25, 33, 35). Mutagenesis, cloning, analysis of gene products by Western blotting, and transcript analysis have been employed for the analysis of these gene networks. However, the lack of an appropriate expression vector that can express cloned genes efficiently in E. faecalis has made the analysis of regulatory genes difficult, and in some cases, has caused confusion due to insufficient cis/trans analysis (2, 14). When the gene of interest cannot be placed in a cell as an allele, a reliable gene expression vector is required for cis/trans analysis.

Escherichia coli-E. faecalis shuttle vectors have greatly facilitated the genetic analysis of enterococci. pAM401 is a widely used shuttle vector (1, 5, 10, 19, 23, 36, 37) that can be maintained stably both in E. coli and in E. faecalis (37); however, it does not have a promoter that allows the constitutive expression of cloned genes in E. faecalis.

One-step purification of recombinant proteins using fused tags and affinity chromatography with ligands to the tags has become a standard technique for protein purification. Tagged proteins are a convenient means of exploring the interactions between proteins (11, 22), protein and DNA, or protein and peptide signals (7). pASK60-Strep (29, 30, 31) is an E. coli protein expression and purification vector that utilizes Strep-tag. Strep-tag confers a moderate affinity to streptavidin to facilitate protein purification. The ability of the TraA protein from the E. faecalis plasmid pAD1 to bind to DNA and the effect of the peptide pheromone on binding have been shown by DNA-associated protein tag affinity chromatography (DPAC) with the Strep-tag (7).

Although heterologous gene expression in an E. coli background is the most common method of producing recombinant proteins from other bacteria, autologous gene expression is an alternative when heterologous expression has failed. Translation initiation sites vary among bacteria, and the prediction of translation initiation sites cannot be done solely by genome sequencing (13). The evidence necessary to determine the translation initiation site can be relatively easily obtained by amino acid sequencing of a tagged protein (18) when expressed in its autologous host.

Bacteriocin 21 (bac21) is on the E. faecalis plasmid pPD1 (9, 35). The bacA gene of bac21 encodes the BacA protein, which is homologous to AS-48 of pMB2 (20). We found that bacA of bac21 is transcribed constitutively. We constructed two new shuttle vectors comprising pAM401, the bacA promoter, a ribosome binding site, and a cloning site, with and without a Strep-tag coding sequence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and PCR primers.

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and PCR primers used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers

| Strain, plasmid, or prime | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. faecalis | ||

| OG1X | str gel | 16 |

| OG1S | str | Don B. Clewell |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80 lacZΔM15 endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK−mk+) supE44 thi-1 ΔgyrA96 (ΔlacZYA-argF)U169 relA1 | Bethesda Research Laboratories |

| DH1 | endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 ΔgyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 12 |

| LE392 | supE44 supF58 hsdR514(rK− mK+) galK2 galT22 metB1 trpR55 lacY1 mcrA | Stratagene |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAM401 | E. coli-E. faecalis shuttle vector; cat, tet | 37 |

| pAD1 | 60 kb; encodes hemolysin and bacteriocin (cytolysin); responds to cAD1; originally found in DS16 | 4 |

| pAM714 | pAD1::Tn917, erm, normal responder of cAD1 | 15 |

| pPD1 | 59 kb; conjugative plasmid from strain 39-5; encodes bac21 | 35, 38 |

| pE · BDEFJ | pPD1 EcoRI fragments B, D, E, F, J cloned in pAM401 | 9 |

| pMGS100 | E. coli-E. faecalis shuttle expression vector | This study |

| pMGS101 | E. coli-E. faecalis shuttle expression and purification vector | This study |

| PCR primers | ||

| Pnpbacal | AAAAACGGCCGGCATGGTTAAAGAAAATAAA | |

| Prpbacal | ATTTTTCGCGACCAAGCAATAACTGCTC | |

| Bapro-for-01 | AAAATAGTCGACTGATTGAAACTCAAGAT | |

| PbacA-EagI-NruI-stop-01 | GTCGGATATCTTATCGCGATTCGGCCGCCTCCTCAAAATATTTTTG | |

| PbacA-EagI-NruI-tag-03 | GTCGGATATCTTAACCACCGAACTGCGGGTGACGCCAAGCACTTC GCGATTCGGCCGCCTCCTCAAAATATTTTTG | |

| LacZ-for-primer-01 | TTTTTCGGCCGGCATGACCATGATTACGGATTCAC | |

| LacZ-rev-primer-01 | ATTTTTCGCGATTTTTGACACCAGACCAACTGG | |

| PN02 (traA, pAD1) | TTTAACGGCCGGCATGTTTCTTTACGAACT | |

| PR01 (traA, pAD1) | ATTTTTCGCGACTCTAGTCTTTTGGTTATT | |

| NruI-seq-rev-01 | GCAACGCGGGCATCCCGAT |

Media, reagents, assays, and standard DNA and RNA techniques.

E. faecalis strains were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth (Becton Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, N.J.). E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (GIBCO BRL, Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) unless otherwise stated. For solid media, 1.5% agar was added to liquid media. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: chloramphenicol, 20 μg/ml for E. faecalis and 50 μg/ml for E. coli; ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; erythromycin, 12.5 μg/ml; streptomycin, 500 μg/ml. X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan) was used at a concentration of 200 μg/ml to obtain blue color development on agar plates. Standard DNA and RNA manipulations were carried out as previously described (28). Transformation of bacteria was done by electrotransformation (8). Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs, Inc. (Beverly, Mass.), and reactions were carried out under the conditions recommended. The PCR cycle used was 2 min at 95°C followed by 30 cycles of 2 min at 95°C, 2 min at 56°C, and 2 min at 72°C using a GeneAmp 9600 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) unless otherwise specified. An ABI PRISM 310 genetic analyzer and BigDye terminator cycle sequencing FS ready reaction kit (Applied Biosystems) were used for DNA sequencing. When the structure of composite plasmids was examined by DNA sequencing, DNA sequences of at least 300 bp from each sequencing primer were confirmed. The β-galactosidase assay was performed using the chloroform lysis method previously described (28). Pheromone response (clumping) assays were as previously described (6). Synthetic cAD1 was prepared by Sawaday Technology Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

Northern blotting analysis of bacA transcript.

The bacA probe was prepared with a PCR DIG probe synthesis kit (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), Pnpbacal and Prpbacal were used as primers, and pPD1 plasmid DNA was used as a template. Total RNAs were prepared by the TRIzol method (Gibco Life Technologies) following the manufacturer's instructions. Hybridization and detection were performed as previously described (26).

Construction of pMGS100 and pMGS101.

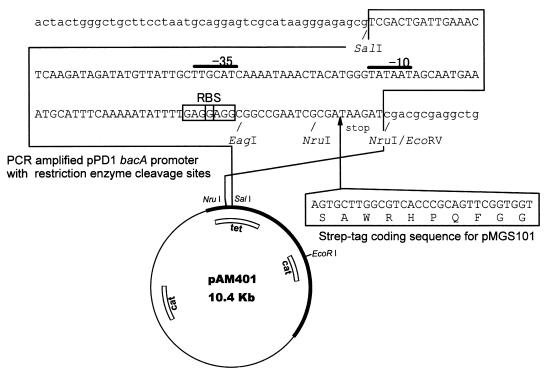

pAM401 was used as a base for vector construction. The bacA promoter and the putative ribosome binding site of the bacA gene were PCR amplified using pPD1 as a template, with Bapro-for-01 and PbacA-EagI-NruI-stop-01 or PbacA-EagI-NruI-tag-03 as primers, respectively. The primers included SalI and EcoRV cleavage sites for ligation with pAM401. EagI/NruI cleavage sites were introduced downstream of the ribosome binding site as a cloning site (see Fig. 2). A stop codon, or a stop codon following the Strep-tag coding sequence, was introduced downstream of the EagI/NruI cleavage sites (the cloning site) (see Fig. 2). The Strep-tag coding sequence was introduced to enable the insert to be inserted in frame in the E. coli expression purification vector pASK60 Eco47III/BsaI cloning site (30) and to allow the insert to be inserted in frame into the new vector. The PCR products were digested with SalI and EcoRV and ligated with NruI/SalI-digested pAM401 and were used to transform DH1. The plasmids with the desired structure were named pMGS100 (without Strep-tag) and pMGS101 (with Strep-tag). The structures of the plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing using NruI-seq-rev-01 as a primer.

FIG. 2.

Construction of pMGS100 and pMGS101. NruI/SalI-cleaved pAM401 was ligated with the SalI/EcoRV-cleaved PCR-amplified promoter region and the putative ribosome binding site (RBS) of the bacA gene of pPD1, with EagI and NruI cleavage sites for use as the cloning site, and with or without the Strep-tag coding sequence for protein purification of the cloned gene's product.

Cloning of the E. coli LE392 lacZ gene.

The lacZ gene of E. coli strain LE392 was PCR amplified using LE392 as a template and the primers LacZ-for-primer-01 and LacZ-rev-primer-01. The primers were designed using the DNA sequence previously described (17). The PCR conditions were 2 min at 95°C followed by 30 cycles of 2 min at 95°C, 2 min at 68°C, and 2 min at 72°C using a GeneAmp 9600 thermal cycler. The PCR product was digested with NruI and EagI and ligated with NruI/EagI-digested pMGS100. The ligated product was used to transform E. coli DH5α. Transformants were selected on LB agar plates containing chloramphenicol and X-Gal. Blue colonies were selected, and one of the clones was partially sequenced using Bapro-for-01 and NruI-seq-rev-01 as primers and was confirmed to have the desired structure. The plasmid was named pMGS100::lacZ.

Cloning of the pAD1 traA gene.

The traA gene of pAD1 was PCR amplified using pAD1 plasmid DNA as a template and the primers PN02 (traA, pAD1) and PR01 (traA, pAD1). The PCR product was digested with NruI and EagI and then ligated with NruI/EagI-digested pMGS100 or pMGS101 and was used to transform DH5α. Transformants were selected on LB agar containing chloramphenicol. Both types of clones were partially sequenced using Bapro-for-01 and NruI-seq-rev-01 as primers and were confirmed to have the desired structures. The plasmids were named pMGS100::traA(pAD1) and pMGS101::traA(pAD1).

Purification of TraA of pAD1 and DPAC.

A cell lysate of E. faecalis OG1X carrying pMGS101::traA(pAD1) was prepared as follows. An overnight culture grown at 37°C in Todd-Hewitt broth containing 5 μg of chloramphenicol per ml was diluted 1:50 into 200 ml of the same medium. The cells were grown at 37°C overnight. After being harvested by centrifugation and resuspension in 400 μl of buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM benzamidine, 100 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 10% glycerol), the cells were disrupted by sonication (approximately 18 W, 12 min at 10% duty cycle). After centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 90 min, the supernatant was recovered. DNase I (10 μl; 10 mg/ml) and RNase (10 μl; 10 mg/ml) were added, and the sample was incubated on ice for 30 min. Then EDTA (25 μl; 500 mM) and Triton X-100 (8 μl; 0.5%) were added. Twenty-five microliters of streptavidin affinity matrix (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was placed in a microcentrifuge tube and washed with 1 ml of TSAGE buffer (150 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 0.02% sodium azide, 10% glycerol) (7). Cell lysate (100 μl) was added to the matrix and was incubated on ice for 30 min. The matrix was washed four times with 1 ml of TSAGE buffer. The purified protein was eluted with 40 μl of 5 mM diaminobiotin (Sigma), and the protein was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). SDS-PAGE protein gels were stained by Silver Stain Plus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). For DPAC, approximately 0.1 μg of RsaI-digested pAM7500 (7, 27) DNA was mixed with the matrix and was incubated on ice for 2 h. The matrix was washed four times with 1 ml of the buffer and was eluted with 40 μl of 5 mM diaminobiotin in TSAGE buffer. The protein-DNA complex solution (20 μl) was subjected to SDS-PAGE. The remainder of the solution was extracted with phenol and chloroform and then was subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis. The agarose gel was stained with SYBR Green I (Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd., Shiga, Japan). Purification of the protein from the E. coli cell lysate was carried out as previously described (7).

RESULTS

Northern blot analysis of bacA transcript.

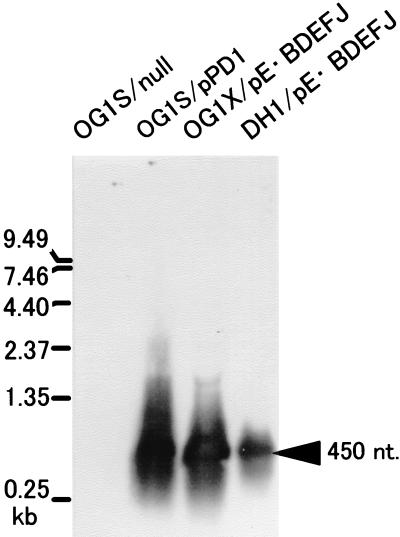

Total RNA of an E. faecalis strain carrying pPD1 or E. faecalis and E. coli strains carrying the bacteriocin genes of pPD1 (9) were analyzed by Northern blotting using the PCR-amplified bacA structural gene (318 bp) as a probe (Fig. 1). A band of approximately 450 nucleotides was observed in the lane for the total RNA of OG1S/pPD1 but was not observed in the lane for OG1S, thus showing that the band corresponds to the bacA transcript. The same band was observed in the lanes for the total RNAs of E. faecalis (OG1X) or E. coli (DH1) carrying the shuttle vector pAM401 that contains the bacteriocin genes of pPD1 (pE · BDEFJ). This result suggests that the promoter of the bacA gene of pPD1 is constitutively expressed both in E. coli and in E. faecalis. We decided to construct E. coli-E. faecalis shuttle vectors that included the bacA promoter and the ribosome binding site of the bacA gene.

FIG. 1.

Northern blot analysis of bacA transcript. Overnight cultures of strains were diluted 1:6 and incubated for 8 h. Total RNA from 8 ml of E. faecalis cultures or 1 ml of E. coli cultures was applied to the agarose gel. The bacA structural gene was used as the probe (see Materials and Methods). OG1S/null, total RNA of E. faecalis OG1S carrying no plasmid. OG1S/pPD1, total RNA of E. faecalis OG1X/pPD1; OG1X/pE · BDEFJ, total RNA of E. faecalis OG1X carrying the plasmid pE · BDEFJ that contains the bac21 determinant of pPD1; DH1/pE · BDEFJ, total RNA of E. coli DH1 carrying pE · BDEFJ. The positions of size markers are indicated on the left. The arrow on the right indicates the position of the band measured as approximately 450 nucleotides (nt) on the gel.

Cloning of E. coli lacZ in pMGS100.

The new expression and purification E. coli-E. faecalis shuttle vectors pMGS100 and pMGS101 were constructed as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 2). To test the ability of the vector to express the cloned genes, we cloned the promoterless lacZ (β-galactosidase) gene of E. coli LE392 into pMGS100. The colonies of E. coli DH5α and E. faecalis OG1X carrying the plasmid developed a blue color on X-Gal plates (data not shown). The β-galactosidase activities of the clones were measured using o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) as a substrate (24) (Table 2). The E. coli clone showed a high level of β-galactosidase activity, comparable to that of DH1 carrying pUC18 (39) that had been induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), while the E. faecalis clone showed a moderate level of activity similar to that of the original E. coli strain LE392.

TABLE 2.

β-Galactosidase activity using ONPG as a substrate

| Strain | β-Galactosidase activity in Miller unitsa | No. of cultures tested |

|---|---|---|

| DH5α/null | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 3 |

| OG1X/null | 0.7 ± 1.2 | 3 |

| LE392 | 7.3 ± 3.2 | 3 |

| DH1/pUC18 induced with 1 mM IPTG | 2.7 × 103 ± 0.6 × 103 | 4 |

| DH5α/pMGS100 | 0.3 ± 1.3 | 4 |

| OG1X/pMGS100 | − 0.3 ± 0.5 | 4 |

| DH5α/pMGS100::lacZ | 2.5 × 103 ± 0.6 × 103 | 4 |

| OG1X/pMGS100::lacZ | 4.6 ± 0.9 | 5 |

Values given are averages and standard deviations.

Cloning of traA of pAD1 in pMGS100 and pMGS101.

To test whether the vector would overexpress the cloned gene in trans, the traA gene of pAD1 (7) was cloned into pMGS100. traA was also cloned into pMGS101 to test the ability of the vector to overexpress the Strep-tag-tagged protein for use in one-step purification and other applications. The plasmids with the desired structures were named pMGS100::traA(pAD1) and pMGS101::traA(pAD1), respectively.

In vitro effect of overexpressed pAD1 TraA by pMGS100::traA(pAD1) placed as an allele of the native pAD1 traA on pheromone sensitivity.

pAD1 is a pheromone-responsive E. faecalis conjugative plasmid which initiates conjugative transfer in response to the peptide pheromone cAD1 (4). The TraA protein of pAD1 is a pheromone receptor carried by the plasmid pAD1. When the strain harboring the plasmid is exposed to the pheromone, it produces an aggregation substance and shows macroclumping as a response. pAM714 is a derivative of pAD1 and has been determined to be a prototype cAD1 responder (15). When pMGS100::traA(pAD1) was introduced into OG1X/pAM714 (the normal responder of the sex pheromone cAD1), the clone showed eightfold less sensitivity to cAD1 in the clumping assay. The clone required 5 ng of synthetic cAD1 per ml for clumping, while clumping was induced in OG1X/pAM714+pMGS100 (control strain) by 0.62 ng of synthetic cAD1 per ml.

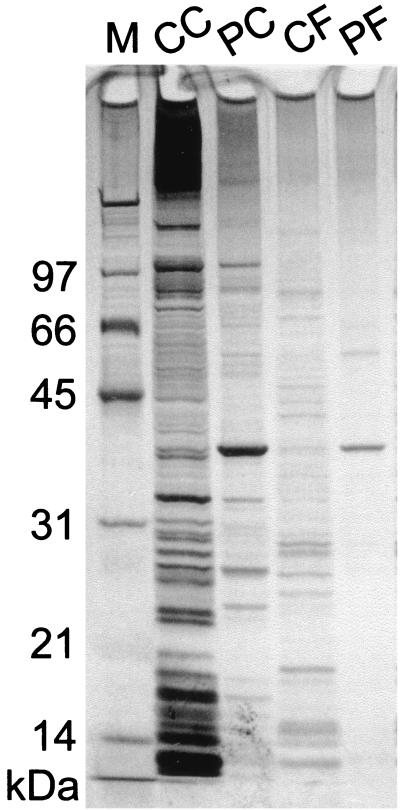

One-step purification of TraA-tag protein.

The TraA-tag protein was purified from an E. faecalis lysate overexpressing TraA-tag by one-step affinity chromatography and was visualized as a single band on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3). The TraA-tag protein was also purified from an E. coli lysate overexpressing TraA-tag (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

One-step affinity purification of TraA-tag protein from E. faecalis. SDS-PAGE of one-step affinity purified proteins. M, molecular size marker (SDS-PAGE molecular mass standards, Bio-Rad Laboratories); CC, crude lysate of DH5α/pMGS101::traA(pAD1) (E. coli); PC, one-step purified TraA-tag purified from DH5α/pMGS101::traA(pAD1) lysate; CF, crude lysate of OG1X/pMGS101::traA(pAD1) (E. faecalis); PF, one-step purified TraA-tag purified from OG1X/pMGS101::traA(pAD1) lysate. The gel was stained with Silver Stain Plus (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The molecular sizes of the size markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left.

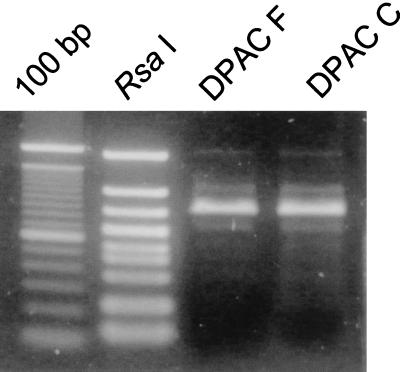

DNA binding assay by DPAC using overexpressed protein from E. faecalis and E. coli.

To test whether the lysate obtained from E. faecalis overexpressing the Strep-tag-tagged protein is suitable for other applications, the lysate was subjected to the DPAC assay. The DNA binding of pAD1 TraA was shown with pMGS101::traA(pAD1). The lysate of OG1X/pMGS101::traA(pAD1) or DH5α/pMGS101::traA(pAD1) was mixed and incubated with the streptavidin affinity matrix in a microcentrifuge tube. The matrix was then washed with buffer. The matrix was incubated with a mixture of DNA fragments (RsaI-digested pAM7500) and washed with buffer. The final eluates contained only the DNA fragment that includes the TraA binding site (32) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

DPAC showing DNA binding of TraA-tag protein from E. faecalis. DNA binding of pAD1 TraA protein shown by the DPAC method. A crude lysate of E. faecalis (100 μl) or E. coli (20 μl), 25 μl of streptavidin affinity matrix (Sigma), and approximately 0.1 μg of RsaI-digested pAM7500 DNA were used for each experiment. The samples were subjected to agarose electrophoresis and stained with SYBR Green I (Takara Shuzo). Abbreviations: 100 bp, 100-bp DNA ladder (GIBCO BRL); RsaI, RsaI-digested pAM7500 (approximately 0.02 μg); DPAC F, phenol-chloroform-extracted protein-DNA complex obtained with E. faecalis lysate; DPAC C, phenol-chloroform-extracted protein-DNA complex obtained with E. coli lysate.

DISCUSSION

We found that the transcription of the bacA gene of the E. faecalis bacteriocin plasmid pPD1 is constitutive. Northern blot analysis produced a strong mRNA hybridization signal, and this gave us the idea of constructing a new E. faecalis-E. coli shuttle vector employing the bacA promoter and the ribosome binding site.

The bacA transcript was observed in E. faecalis harboring pPD1 (Fig. 1). The hybridization signals were specific and intense compared to the results of similar experiments with pAD1 traE (32) and uvrA (26) or pIY17 bac31 (34), for which a similar amount of total RNA was used.

Two new vectors were constructed using the widely used E. faecalis-E. coli shuttle vector pAM401 as a base for construction. The lacZ gene from E. coli strain LE392 and the traA gene of the E. faecalis pheromone-responsive hemolysin plasmid pAD1 were cloned into the vectors to demonstrate the practical applications of the vectors. Expression of both genes was confirmed by enzyme activity, bioassay, or purification of the protein.

The lacZ gene in pMGS100 expressed β-galactosidase activity both in E. coli and in E. faecalis. When the pAD1 traA clone in pMGS100 was introduced into E. faecalis harboring pAM714 (the normal responder of cAD1), the strain showed eightfold less sensitivity to the pheromone cAD1. This observation is interpreted as being due to the relatively low concentration of cAD1 to TraA protein as a result of the overexpression of TraA having made the strain less sensitive to cAD1. This suggests that the expression of the cloned gene in pMGS100 is high enough to perform cis/trans analysis.

When pAD1 traA was cloned in pMGS101, the Strep-tag-tagged TraA was overexpressed both in E. coli and in E. faecalis and could be purified by one-step affinity chromatography. Overexpression and one-step purification of tagged proteins from an autologous background make it possible to obtain proteins of higher integrity for further experiments, like the determination of the translation initiation site in the original organism (18).

The lysate obtained from E. faecalis or E. coli overexpressing Strep-tag-tagged TraA could be used directly for the DPAC assay. DNA binding of TraA was shown by capture of a DNA fragment containing the binding site from the mixture of DNA fragments. This clearly indicates the suitability of the proteins obtained with the vector for use in further applications to determine the interaction of proteins with other proteins, DNA, or other molecules.

There are a number of questions to which the new vectors may provide answers. For example, in the case of bac21 of the E. faecalis bacteriocin plasmid pPD1, there are two problems that may be solved with the new vectors. One is the difference in gene expression in different backgrounds, and the other is the position of the translation initiation site. As shown in Fig. 1, the bacA transcript was observed in E. coli as well as in E. faecalis when it was cloned in pAM401 as the operon bac21 (pE · BDEFJ). pE · BDEFJ in an E. faecalis background shows bacteriocin activity; however, it does not express bacteriocin activity in an E. coli background. By comparison of the gene products obtained from E. faecalis and E. coli, it may be possible to understand the difference in autologous and heterologous expressions. Nine genes (bacA to bacI) are required for the full expression of bac21 (35). The published DNA sequence of the AS-48 gene, although it does not include bacH and bacI portions, is identical to the bac21 gene. However, the deduced open reading frames (ORFs) for bacteriocin expression include ORFs with translation initiation sites that differ from that of bac21 (21). The role of the ORFs and the position of the translation initiation sites will be the subject of studies with the new vectors.

We have constructed and shown the applications of the new expression and purification E. coli-E. faecalis shuttle vectors pMGS100 and pMGS101. The vectors will provide an opportunity to observe various biological phenomena in the original E. faecalis background and will help improve our knowledge of the regulation of various genes, including pathogenic genes and drug resistance genes such as those of vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

Finally, plasmid pIP501, the gram-positive replicon of pMGS100 and pMGS101, is reported to be maintained in several species of gram-positive cocci (37). Plasmid pAM401 has the same replicon and has been used for cloning in Streptococcus gordonii (23), Lactococcus lactis (10), and a group B streptococcus (19) background. The vectors may also have applications in the research of other gram-positive bacterial species.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture and a grant from the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare.

We thank E. Kamei for helpful advice on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.An F Y, Clewell D B. The origin of transfer (oriT) of the enterococcal, pheromone-responding, cytolysin plasmid pAD1 is located within the repA determinant. Plasmid. 1997;37:87–94. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bae T, Clerc-Bardin S, Dunny G M. Analysis of expression of prgX, a key negative regulator of the transfer of the Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-inducible plasmid pCF10. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:861–875. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clewell D B. Movable genetic elements and antibiotic resistance in enterococci. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:90–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01963632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clewell D B, Tomich P K, Gawron-Burke M C, Franke A E, Yagi Y, An F Y. Mapping of Streptococcus faecalis plasmids pAD1 and pAD2 and studies relating to transposition of Tn917. J Bacteriol. 1982;152:1220–1230. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.3.1220-1230.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demuth D R, Berthold P, Leboy P S, Golub E E, Davis C A, Malamud D. Saliva-mediated aggregation of Enterococcus faecalis transformed with a Streptococcus sanguis gene encoding the SSP-5 surface antigen. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1470–1475. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.5.1470-1475.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunny G M, Craig R A, Carron R L, Clewell D B. Plasmid transfer in Streptococcus faecalis: production of multiple sex pheromones by recipients. Plasmid. 1979;2:454–465. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(79)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujimoto S, Clewell D B. Regulation of the pAD1 sex pheromone response of Enterococcus faecalis by direct interaction between the cAD1 peptide mating signal and the negatively regulating, DNA-binding TraA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6430–6435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujimoto S, Hashimoto H, Ike Y. Low cost device for electrotransformation and its application to the highly efficient transformation of Escherichia coli and Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid. 1991;26:131–135. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(91)90053-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujimoto S, Tomita H, Wakamatsu E, Tanimoto K, Ike Y. Physical mapping of the conjugative bacteriocin plasmid pPD1 of Enterococcus faecalis and identification of the determinant related to the pheromone response. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5574–5581. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5574-5581.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garvey P, Fitzgerald G F, Hill C. Cloning and DNA sequence analysis of two abortive infection phage resistance determinants from the lactococcal plasmid pNP40. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4321–4328. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4321-4328.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant P A, Schieltz D, Pray-Grant M G, Steger D J, Reese III J C, Yates J R, Workman J L. A subset of TAF(II)s are integral components of the SAGA complex required for nucleosome acetylation and transcriptional stimulation. Cell. 1998;94:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hannenhalli S S, Hayes W S, Hatzigeorgiou A G, Fickett J W. Bacterial start site prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3577–3582. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.17.3577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedberg P J, Leonard B A, Ruhfel R E, Dunny G M. Identification and characterization of the genes of Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pCF10 involved in replication and in negative control of pheromone-inducible conjugation. Plasmid. 1996;35:46–57. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ike Y, Clewell D B. Genetic analysis of the pAD1 pheromone response in Streptococcus faecalis, using transposon Tn917 as an insertional mutagen. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:777–783. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.3.777-783.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ike Y, Craig R A, White B A, Yagi Y, Clewell D B. Modification of Streptococcus faecalis sex pheromones after acquisition of plasmid DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:5369–5373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.17.5369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalnins A, Otto K, Ruther U, Muller-Hill B. Sequence of the lacZ gene of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1983;2:593–597. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawakami T, Kaneko A, Okada N, Imajoh-Ohmi S, Nonaka T, Matsui H, Kawahara K, Danbara H. TTG as the initiation codon of Salmonella slyA, a gene required for survival within macrophages. Microbiol Immunol. 1999;43:351–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1999.tb02415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreikemeyer B, Jerlstrom P G. An Escherichia coli-Enterococcus faecalis shuttle vector as a tool for the construction of a group B Streptococcus heterologous mutant expressing the beta antigen (Bac) of the C protein complex. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;180:255–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez-Bueno M, Maqueda M, Galvez A, Samyn B, Van Beeumen J, Coyette J, Valdivia E. Determination of the gene sequence and the molecular structure of the enterococcal peptide antibiotic AS-48. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6334–6339. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.20.6334-6339.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez-Bueno M, Valdivia E, Galvez A, Coyette J, Maqueda M. Analysis of the gene cluster involved in production and immunity of the peptide antibiotic AS-48 in Enterococcus faecalis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:347–358. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martzen M R, McCraith S M, Spinelli S L, Torres F M, Fields S, Grayhack E J, Phizicky E M. A biochemical genomics approach for identifying genes by the activity of their products. Science. 1999;286:1153–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNab R, Forbes H, Handley P S, Loach D M, Tannock G W, Jenkinson H F. Cell wall-anchored CshA polypeptide (259 kilodaltons) in Streptococcus gordonii forms surface fibrils that confer hydrophobic and adhesive properties. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3087–3095. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.10.3087-3095.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Keeffe T, Hill C, Ross R P. Characterization and heterologous expression of the genes encoding enterocin A production, immunity, and regulation in Enterococcus faecium DPC1146. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1506–1515. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1506-1515.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozawa Y, Tanimoto K, Fujimoto S, Tomita H, Ike Y. Cloning and genetic analysis of the UV resistance determinant (uvr) encoded on the Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-responsive conjugative plasmid pAD1. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7468–7475. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7468-7475.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pontius L T, Clewell D B. Regulation of the pAD1-encoded sex pheromone response in Enterococcus faecalis: nucleotide sequence analysis of traA. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1821–1827. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.6.1821-1827.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt T G, Skerra A. One-step affinity purification of bacterially produced proteins by means of the “Strep tag” and immobilized recombinant core streptavidin. J Chromatogr. 1994;676:337–345. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(94)80434-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt T G, Skerra A. The random peptide library-assisted engineering of a C-terminal affinity peptide, useful for the detection and purification of a functional Ig Fv fragment. Protein Eng. 1993;6:109–122. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skerra A, Schmidt T G. Applications of a peptide ligand for streptavidin: the Strep-tag. Biomol Eng. 1999;16:79–86. doi: 10.1016/s1050-3862(99)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanimoto K, Clewell D B. Regulation of the pAD1-encoded sex pheromone response in Enterococcus faecalis: expression of the positive regulator TraE1. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1008–1018. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1008-1018.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomita H, Clewell D B. A pAD1-encoded small RNA molecule, mD, negatively regulates Enterococcus faecalis pheromone response by enhancing transcription termination. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1062–1073. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.1062-1073.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomita H, Fujimoto S, Tanimoto K, Ike Y. Cloning and genetic organization of the bacteriocin 31 determinant encoded on the Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-responsive conjugative plasmid pYI17. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3585–3593. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3585-3593.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomita H, Fujimoto S, Tanimoto K, Ike Y. Cloning and genetic and sequence analyses of the bacteriocin 21 determinant encoded on the Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-responsive conjugative plasmid pPD1. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7843–7855. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.24.7843-7855.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weaver K E, Walz K D, Heine M S. Isolation of a derivative of Escherichia coli-Enterococcus faecalis shuttle vector pAM401 temperature sensitive for maintenance in E. faecalis and its use in evaluating the mechanism of pAD1 par-dependent plasmid stabilization. Plasmid. 1998;40:225–232. doi: 10.1006/plas.1998.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wirth R, An F Y, Clewell D B. Highly efficient protoplast transformation system for Streptococcus faecalis and a new Escherichia coli-S. faecalis shuttle vector. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:831–836. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.831-836.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yagi Y, Kessler R E, Shaw J H, Lopatin D E, An F, Clewell D B. Plasmid content of Streptococcus faecalis strain 39-5 and identification of a pheromone (cPD1)-induced surface antigen. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:1207–1215. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-4-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]