Abstract

Overdose deaths involving opioids have increased dramatically since the 1990s, leading to the worst drug overdose epidemic in U.S. history, but there is limited empirical evidence about the initial causes. In this article, we examine the role of the 1996 introduction and marketing of OxyContin as a potential leading cause of the opioid crisis. We leverage cross-state variation in exposure to OxyContin’s introduction due to a state policy that substantially limited the drug’s early entry and marketing in select states. Recently unsealed court documents involving Purdue Pharma show that state-based triplicate prescription programs posed a major obstacle to sales of OxyContin and suggest that less marketing was targeted to states with these programs. We find that OxyContin distribution was more than 50% lower in “triplicate states” in the years after the drug’s launch. Although triplicate states had higher rates of overdose deaths prior to 1996, this relationship flipped shortly after the launch and triplicate states saw substantially slower growth in overdose deaths, continuing even 20 years after OxyContin’s introduction. Our results show that the introduction and marketing of OxyContin explain a substantial share of overdose deaths over the past two decades.

Keywords: I12, I18

I. Introduction

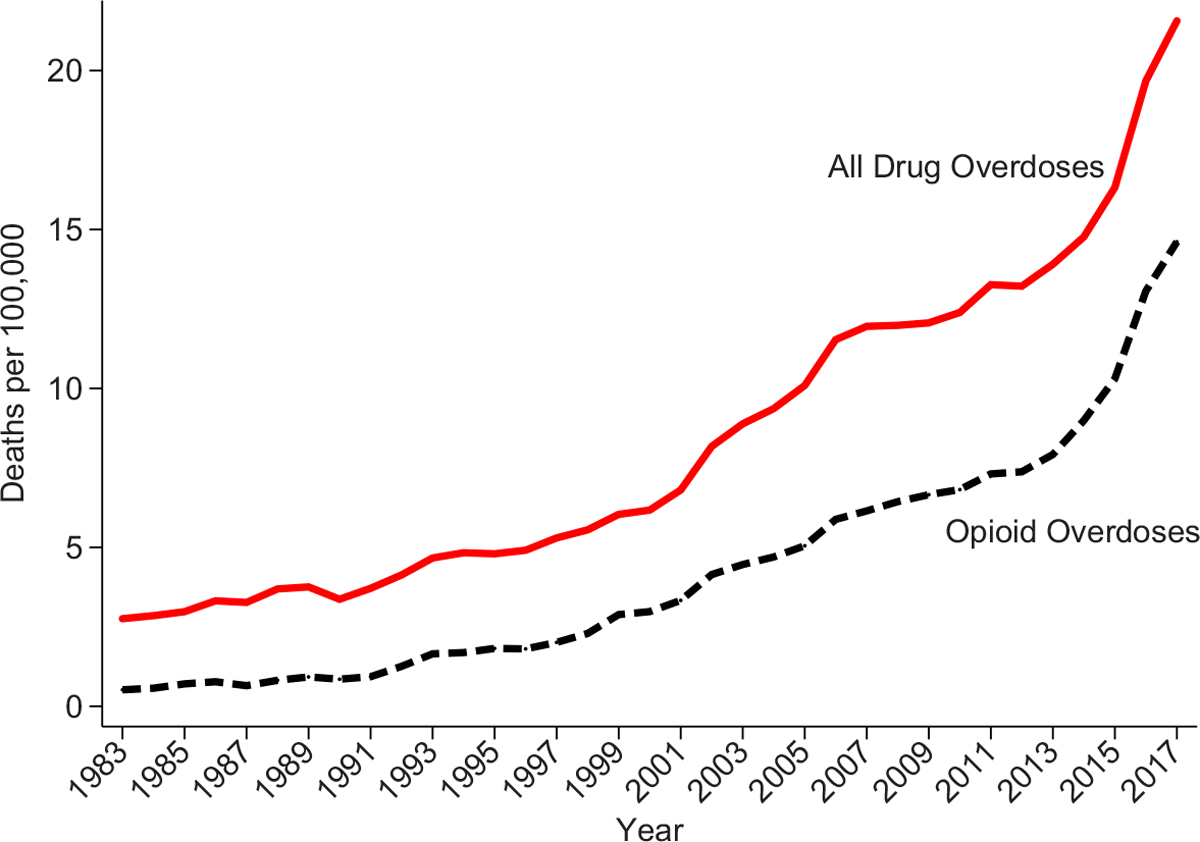

Since the 1990s, there has been a staggering increase in mortality from drug overdoses in the United States. Between 1983 and 2017, the drug overdose death rate increased by a factor of eight, with a dramatic increase beginning in the 1990s (Figure I). Overdose deaths involving opioids account for 75% of the growth and, by 2017, two-thirds of all drug overdose deaths were related to opioids.1 Overdoses involving opioids claimed the lives of 47,600 people in 2017 (Scholl et al. 2019) and almost 500,000 since 1999 (CDC 2021), about the same number of U.S. soldiers who died in World War II (DeBruyne 2018). This massive rise in opioid deaths has contributed to the longest sustained decline in life expectancy since 1915 (Dyer 2018).

Figure I.

National Drug Overdose Death Rates

We use geocoded NVSS data to construct all drug overdose and opioid overdose deaths per 100,000. See Section III.A for ICD codes used in each period. Opioid overdoses are defined as overdoses that report opioid involvement (including natural/semisynthetic opioids, methadone, heroin, and synthetic opioids). These overdoses may or may not also include nonopioid substances.

There are many hypotheses about the initial causes of the opioid crisis. Case and Deaton (2015, 2017) suggest that demand factors played an important role as worsening cultural and economic conditions may have sparked a surge in “deaths of despair”: suicides, alcohol-related mortality, and drug overdoses. Empirical tests have found mixed evidence on the role of economic conditions in driving drug misuse and overdoses (e.g., Ruhm 2019a; Pierce and Schott 2020; Venkataramani et al. 2020). Alternative hypotheses, though not mutually exclusive ones, consider the role of supply factors. Beginning in the 1990s, changing attitudes and new treatment guidelines encouraged doctors to treat pain more aggressively with opioids (Quinones 2015; Jones et al. 2018).2 In addition, in 1996, Purdue Pharma launched its drug OxyContin, a prescription opioid pain reliever that quickly became one of the leading drugs of abuse in the United States (Cicero, Inciardi, and Muñoz 2005).

Despite the discussion of these supply-side hypotheses throughout the literature, there is surprisingly little empirical evidence on any individual factor’s importance. Ruhm (2019a) finds that increased access to opioids overall, rather than economic conditions, was a major driver of growth in overdose rates since 1999. Powell, Pacula, and Taylor (2020) show that increased opioid access through Medicare led to higher rates of opioid diversion and overdose deaths.3 Existing research is relevant to understanding the role of supply versus demand factors in driving the ongoing crisis; however, none of these studies isolate the causes of the initial rise in overdose deaths in the 1990s.

In this article, we provide the first quasi-experimental evidence on the initial causes of the opioid crisis, which is commonly dated as beginning in the 1990s.4 We examine the role of the introduction and marketing of OxyContin as a potential leading cause, exploring its effects on drug overdose deaths over the two decades since its launch. The aggressive and deceptive marketing of OxyContin has been the subject of enormous public and scholarly discussion (e.g., Van Zee 2009; Kolodny et al. 2015; Quinones 2015) and thousands of lawsuits from state and local governments, which have implicated OxyContin as “the taproot of the opioid epidemic.”5 Defenders of OxyContin argue that numerous other suppliers of opioids and the behaviors of physicians and patients played a larger role (McLean 2019).6

Since OxyContin was launched nationwide, it is difficult to isolate its effects from other concurrent changes to prescribing practice patterns, opioid availability, and demand. We address this issue by exploiting geographic variation in exposure to OxyContin’s introduction due to a previously unexplored state policy that substantially limited OxyContin’s entry and marketing in select states. We obtained information on the importance of this state policy from recently unsealed court documents we collected from multiple settled lawsuits involving Purdue Pharma. These documents provide an unprecedented look at the manufacturer’s internal marketing strategies for OxyContin. They reveal that Purdue Pharma viewed state-based “triplicate prescription programs,” an unusually stringent early prescription drug monitoring program, as a significant barrier to prescribing OxyContin. They suggest that the company did not target marketing to states with triplicate programs given the lower expected returns. For example, Purdue Pharma’s focus group research found that “doctors in the triplicate states were not enthusiastic about the product [OxyContin] at all, with only a couple indicating they would ever use it, and then in very infrequent situations” and recommended that “the product should only be positioned to physicians in non-triplicate states” (Groups Plus 1995).

Using a difference-in-differences framework, we take advantage of the variation in OxyContin use induced by these triplicate policies to study drug overdose trends in states with triplicate programs relative to states without these programs. We consider the nontriplicate states to be more exposed to OxyContin’s introduction because the barriers to prescribing were lower and more initial marketing was targeted to these states. Indeed, we find that OxyContin distribution was more than twice as high in nontriplicate states in the years after the launch.

Given this variation in exposure to OxyContin’s introduction, we estimate the drug’s effect on drug overdose deaths over the short and long run. Prior to OxyContin’s launch, the two groups of states had similar trends in drug overdose death rates. These trends diverged shortly after the launch, with overdose deaths increasing much more rapidly in nontriplicate states, a trend that continued even 20 years later. This differential growth is driven by drug overdoses involving prescription opioids until 2010. After 2010, when the original formulation of OxyContin was replaced with an abuse-deterrent version, large differences in deaths involving heroin and fentanyl emerged. This is consistent with prior evidence that areas with high rates of OxyContin misuse experienced differential transitions to illicit opioids as people substituted from OxyContin to heroin (Alpert, Powell, and Pacula 2018; Evans, Lieber, and Power 2019).

Overall, our estimates imply that nontriplicate states would have had an average of 34% fewer drug overdose deaths and 45% fewer opioid overdose deaths from 1996 to 2017 if they had been triplicate states at the time of OxyContin’s launch. Our results are not explained by other opioid policies, economic shocks, or differences in urbanicity and population size. We do not find similar patterns in the use of prescription opioids not covered by triplicate programs or other deaths of despair. It is statistically rare to observe effect sizes of a similar magnitude as our main estimates when we randomly assign triplicate status to other states.

This research contributes to our understanding of what initially sparked the opioid crisis. We find that the introduction and marketing of OxyContin explain a substantial share of overdose deaths over the past two decades. Although triplicate programs were discontinued in the years after OxyContin’s launch, their initial deterrence of OxyContin promotion had long-term effects on overdose deaths in these states, dramatically decreasing overdose death rates even today. The triplicate states currently have some of the lowest overdose death rates in the country. Our work also speaks to the importance of early regulations in explaining current geographic variation in overdose deaths.

Although triplicate programs may have discouraged OxyContin adoption, the enduring mortality differences across states even after triplicate programs had ended suggest that persistent marketing practices played a more central role. We evaluate the role of marketing relative to the independent long-term effects of triplicate programs by studying former triplicate states that eliminated their triplicate programs just before OxyContin’s launch. Former triplicate states experienced high rates of OxyContin adoption and overdose mortality growth similar to states that never had triplicate programs, suggesting minimal legacy effects of these programs. Instead, the lack of OxyContin marketing in triplicate states appears to explain the persistent low growth in overdose deaths.

The remainder of the article proceeds as follows. We provide additional background in Section II. Section III introduces the data, and Section IV discusses the empirical strategy. We present the results and discuss mechanisms in Section V. In Section VI, we consider alternative explanations for the observed differential overdose trends. Section VII concludes. All appendix material can be found in the Online Appendix.

II. Background

II.A. OxyContin’s Launch and Promotional Activities

In this section, we provide a brief background on OxyContin and its promotion (see Online Appendix B for a more detailed history). OxyContin is a long-acting formulation of oxycodone, a morphine-like drug, produced by Purdue Pharma. Given its high potential for abuse, it is classified as a Schedule II controlled substance. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved OxyContin in 1995, and the drug was introduced to the market in January 1996. OxyContin’s key technological innovation was its sustained-release formulation that uses a high concentration of the active ingredient to provide 12 hours of continuous pain relief. However, crushing or dissolving the pill allowed users to access the high dosage of oxycodone all at once, producing an intense high. The high potency of OxyContin made it one of the leading drugs of abuse in the United States (Cicero, Inciardi, and Muñoz 2005) and concerns about widespread abuse of this drug were being reported by 2000 (GAO 2003).

Purdue Pharma launched an aggressive advertising campaign for OxyContin that was unprecedented for an opioid in terms of the promotional spending (GAO 2003) and the type of physicians being targeted. They targeted marketing to primary care physicians to promote the drug for noncancer chronic pain—a previously untapped market for opioids.7 Such physician detailing has been shown to be effective at increasing prescribing (Carey, Lieber, and Miller 2021; Agha and Zeltzer forthcoming).8 Indeed, OxyContin prescriptions increased at a faster rate for noncancer pain than for cancer pain from 1997 to 2002 (GAO 2003). The initial marketing strategy centered on false claims that the drug had low abuse potential and was safer than other opioid drugs.9 The original FDA product label for OxyContin included the statement that “delayed absorption as provided by OxyContin tablets, is believed to reduce the abuse liability of a drug,” which became a cornerstone of the initial marketing campaign.

Overall, these marketing efforts contributed to OxyContin’s blockbuster success. Revenue from its sales skyrocketed from $48 million in 1996 to $1.1 billion in 2000 (Van Zee 2009) and $3.1 billion in 2010 (IMS 2011). The marketing of OxyContin eventually concerned local and state governments. In 2007, Purdue Pharma paid fines over $600 million for misleading advertising. In 2020, another lawsuit resulted in an $8.3 billion settlement.

II.B. Geographic Variation in Exposure to OxyContin’s Introduction

This study exploits previously unexplored geographic variation in OxyContin’s introduction and initial marketing. To understand how OxyContin was marketed, we made Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to obtain recently unsealed documents in Florida, Washington, and West Virginia from investigations and settled court cases involving Purdue Pharma.10 Among these documents, we obtained the launch plan for OxyContin, the focus group research conducted prior to the launch (see Online Appendix Figure A1), and annual itemized budgets for OxyContin from 1996 to 2002. These documents revealed that Purdue Pharma would have difficulty penetrating markets that had enacted a state policy known as a triplicate prescription program and suggested that it would target less marketing to these states.

1. What Are Triplicate Prescription Programs?

Triplicate prescription programs were among the earliest prescription drug monitoring programs enacted to reduce the diversion and misuse of controlled substances. Triplicate programs mandated that doctors use state-issued triplicate prescription forms when prescribing Schedule II controlled substances (which includes many opioids). The physician was required to maintain one copy of the triplicate form for their records. The patient was given two copies to give to the pharmacy; the pharmacy kept one and sent the third copy to the state drug monitoring agency. States kept a database of the forms to monitor and investigate prescribing irregularities.

The academic literature on triplicate programs finds that such programs led to dramatic reductions in the prescribing of drugs subject to the policy (Sigler et al. 1984; Weintraub et al. 1991; Hartzema et al. 1992; Simoni-Wastila et al., 2004). There are two main reasons for these reductions. First, physicians in triplicate states were concerned about government oversight of their prescribing behavior (Berina et al. 1985). As Purdue Pharma observed in its focus group research: “The doctors did not want to provide the Government with any ammunition to question their medical protocols relative to pain management. The mere thought of the government questioning their judgement created a high level of anxiety” (Groups Plus 1995, 24). Although electronic monitoring programs also involved government oversight, relative to electronic systems, “It was felt that paper forms, tangible reminders of such scrutiny when handled by the prescribing physician and dispensing pharmacist, would have a greater effect on reduced prescribing and dispensing than would an electronic system that remained largely invisible to health care practitioners” (Simoni-Wastila and Toler n.d., 3).

Second, triplicate programs imposed large hassle costs on physicians. According to Purdue Pharma’s research: “Writing triplicate prescriptions was more trouble than others, due to the details of the forms and the various people that need to be copied to them. To the extent that they [physicians] can avoid this extra effort, they will try to follow alternative protocols” (Groups Plus 1995, 24). Placing this burden specifically on the prescriber rather than on the pharmacist suggests a key reason for why triplicate programs are found to have substantial effects on prescriptions, while some modern electronic prescription drug monitoring programs (particularly, nonmandate PDMPs) have more muted effects.11

At the time of OxyContin’s launch in 1996, five states had active triplicate programs: California, Idaho, Illinois, New York, and Texas.12 The enactment and end years of the triplicate programs are listed in Online Appendix Table A1.13 These triplicate programs were adopted decades before OxyContin’s launch. California adopted the first triplicate program in 1939 (Joranson et al. 2002); other states adopted the program between 1961 and 1988. Indiana and Michigan also had triplicate programs, but they ended their programs two years before OxyContin’s launch.14

The triplicate states all discontinued their programs by 2004. Therefore, our analysis speaks to the long-run effects of the initial targeting of Purdue Pharma’s marketing due to triplicate status during the launch. The discontinuation of these programs provides an opportunity to isolate long-term persistent effects of marketing from the direct effects of having a triplicate program. In addition, we separate the legacy effects of triplicate programs from the marketing effects induced by OxyContin’s launch by separately analyzing the two former triplicate states (Indiana and Michigan), which repealed their triplicate programs prior to 1996.15

2. Purdue Pharma’s Marketing in Triplicate and Nontriplicate States.

Triplicate programs are mentioned repeatedly in Purdue Pharma’s internal documents given concerns borne out in their premarket research that physicians in triplicate states would be less willing to prescribe OxyContin. Purdue Pharma found that “physicians in the triplicate state did not respond positively to the drug [OxyContin], since it is a Class II narcotic which would require triplicate prescriptions. Therefore, only a few would ever use the product, and for them it would be on a very infrequent basis” (Groups Plus 1995, 36).16

Based on this research, the launch plan acknowledges that “these regulations create a barrier when positioning OxyContin” (Purdue Pharma 1995, 4). They recommended that “the product should only be positioned to physicians in non-triplicate states” (Groups Plus 1995, 55). Furthermore, they noted that “our research suggests the absolute number of prescriptions they [physicians in triplicate states] would write each year is very small, and probably would not be sufficient to justify any separate marketing effort” (Groups Plus 1995, 49).17

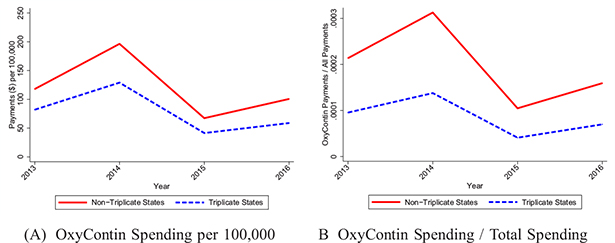

Although we do not have data that breaks down Purdue Pharma’s initial marketing spending by state to confirm this strategy directly, we examined their marketing in 2013–2016 using the CMS Open Payments database as a measure of persistent differences in marketing. These data report payments made from pharmaceutical manufacturers to physicians related to the promotion of specific drugs, including payments for meals, travel, and gifts. Figure II shows that nontriplicate states received 44%–71% more payments per capita for OxyContin than triplicate states in each year (Panel A).18 As an alternative metric, we scaled OxyContin payments by total payments (across all drugs) to account for state-level differences in marketing (Panel B). The gap between triplicates and nontriplicates grows wider when using this metric.

Figure II.

OxyContin Promotional Payments to Physicians

We used CMS Open Payments Data to calculate total payments and gifts made to physicians regarding OxyContin (presented in nominal dollars). In Panel A, we scaled this measure by population. In Panel B, we scaled this measure by total promotional spending (across all drugs). The outcomes correspond to August 2013–December 2016. Because the 2013 data only cover a partial year, we annualize the rate in that year.

The persistence of the initial targeting based on triplicate status is consistent with the marketing strategy discussed in the internal documents. Early budget plans for Purdue Pharma dictated that the sales force target calls to the top deciles of physicians in terms of past prescribing volumes; more recent documents show that this targeting strategy continued through 2018.19 Thus, if triplicate states initially received less marketing and this resulted in lower prescribing, these states would continue to receive less marketing in future periods as well. This evidence supports our empirical design of studying the long-term effects of OxyContin’s launch based on whether a state initially had a triplicate program.

III. Data

III.A. Mortality Data

We use a restricted-use version of the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) Multiple Cause of Death mortality files from 1983 to 2017 that contains state and county of residence identifiers.20 These data represent a census of deaths in the United States. The 1983–1998 data use ICD-9 codes to categorize causes of deaths, while the 1999–2017 data use ICD-10 codes. We follow the coding used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to categorize deaths as drug- and opioid-related across both sets of classification systems.21 The CDC reports that the transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10 resulted in a small increase in poisoning-related deaths (not necessarily drug poisonings) of 2% (Warner et al. 2011).22 Our time fixed effects account for this transition, given that we would not expect systematically different effects of the coding change across states.

Given concerns over missing opioid designations on death certificates for drug-related overdoses (e.g., Ruhm 2018), we favor using a broader measure of total drug overdose deaths in most of our analysis, which should be robust to substance-specific classification errors (Venkataramani and Chatterjee 2019). However, we also present results for opioid-related overdose deaths. In addition, we study disaggregated measures of drug overdose deaths by type of opioid from 1999 to 2017, including heroin (T40.1), natural and semisynthetic opioids (T40.2) such as OxyContin, and synthetic opioids (T40.4) such as fentanyl.23

III.B. Opioid Distribution, Prescriptions, and Misuse

We use state-level data on the legal supply of opioids from the Drug Enforcement Agency’s Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System (ARCOS). Manufacturers and distributors are required to report their transactions and deliveries of all Schedule I and II substances, all narcotic Schedule III substances, and a number of Schedule IV–V substances to the Attorney General. This includes all oxycodone and hydrocodone products.24 We analyze data available online for 2000–2017, and we collected earlier data for 1997–1999 using the WayBack Machine.25 In the public data, only active ingredients are reported, so we observe oxycodone but not OxyContin.26 Because of our interest in OxyContin, we made a FOIA request for OxyContin distribution specifically and received these data for 2000–2016. We report all ARCOS measures in morphine equivalent doses (MEDs), defined as 60 morphine milligram equivalents.

As complementary measures, we use Medicaid State Drug Utilization Data for 1996–2005, which reports the number of Medicaid prescriptions by National Drug Code, quarter, and state.27 Although the Medicaid population is nonrepresentative, prescriptions among this group are a potentially useful proxy for state prescribing behavior and represent an important population disproportionately affected by the opioid crisis (Sharp and Melnik 2015). In addition, we use a restricted version of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) with state identifiers, accessed through the AHRQ Data Facility, for 1996–2016. The MEPS is a nationally representative survey of households, including pharmaceutical claims.

Finally, we study self-reported rates of opioid misuse in the past year for OxyContin and all other pain relievers (excluding OxyContin) using the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) for 2004–2013.28 OxyContin misuse is first available in 2004 and is reported in two-year waves. The NSDUH is a nationally representative survey of individuals ages 12 and older and is the largest survey collecting information on substance use in the United States.29

III.C. Summary Statistics

In Online Appendix Table A1, we present summary statistics for 1991–1995, representing the pre-OxyContin period, separately for each triplicate state and aggregated means by triplicate status. Drug overdose and opioid-related overdose death rates are higher on average in the triplicate states before OxyContin’s introduction. Some of these differences can be explained by disproportionately higher rates of cocaine-related deaths in these states. When overdoses involving cocaine are eliminated, the differences between triplicate and nontriplicate states shrink. With respect to demographic characteristics, triplicate states have larger populations, and a larger share of the population is Hispanic.30 Age and education distributions are similar.

IV. Empirical Strategy

To estimate the effect of OxyContin’s introduction, we use a difference-in-differences framework that compares outcomes in nontriplicate states relative to triplicate states before and after the launch of OxyContin. We rely on event study models because of their transparency and because the timing of the effect is of interest. We report the differential change in overdose death rates for nontriplicate states relative to triplicate states given that nontriplicate states were more “exposed” to the introduction of OxyContin. The event study specification is:

| (1) |

where yst represents annual drug overdose deaths per 100,000 people in state s in year t. This specification includes state (αs) and year (γt) fixed effects. 1(Nontriplicate)s is an indicator based on the initial triplicate status of the state in 1996, and it is interacted with a full set of year fixed effects. The nontriplicate indicator is fixed over the entire time period so the estimates refer to the effects of initial triplicate status. We present the estimates of βk along with 95% confidence intervals graphically, normalizing β1995 to equal zero. Our main results are population weighted. We also summarize the results using a more parsimonious difference-in-differences specification:

| (2) |

The excluded category is 1991–1995 as we limit the sample to 1991–2017 for the difference-in-differences analyses.31 We estimate three separate “post” effects to permit some heterogeneity while still providing more aggregated effects. The first post-OxyContin effect (δ1) is for the time period 1996–2000, representing the introduction of OxyContin, the launch of different dosages, and the initial ramp-up of marketing. We also estimate an effect for 2001–2010 (δ2), corresponding to the “first wave” of the opioid crisis when most deaths are from prescription opioids. Finally, we estimate a separate effect for 2011–2017 (δ3), representing the second and third waves of the crisis when deaths from heroin and fentanyl became more prominent.

We also present estimates for both equations including covariates. Our baseline controls include the fraction of the population that is white non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, the fraction ages 25–44, 45–64, 65+, the fraction with a college degree, and log population.

Because we have a small number of untreated states, traditional cluster covariance estimators produce standard error estimates that are too small (Brewer, Crossley, and Joyce 2018). We use a restricted wild cluster bootstrap method at the state level to account for within-state dependence in all models, relying on a six-point weight distribution as suggested by Webb (2014) when there are few clusters. Given p-values for a range of null hypotheses, we construct and report 95% confidence intervals, which will not be symmetric using this approach.32 In the Online Appendix, we show that traditional “clustered” standard errors produce much smaller confidence intervals. We also conduct permutation tests, discussed in Section VI.B.

V. Results

Our analysis begins by documenting large differences in OxyContin use across triplicate and nontriplicate states. We estimate the effect of these differences on drug overdose deaths over the short and long run and explore the mechanisms for persistent mortality effects.

V.A. Effects of Triplicate Status on OxyContin Use

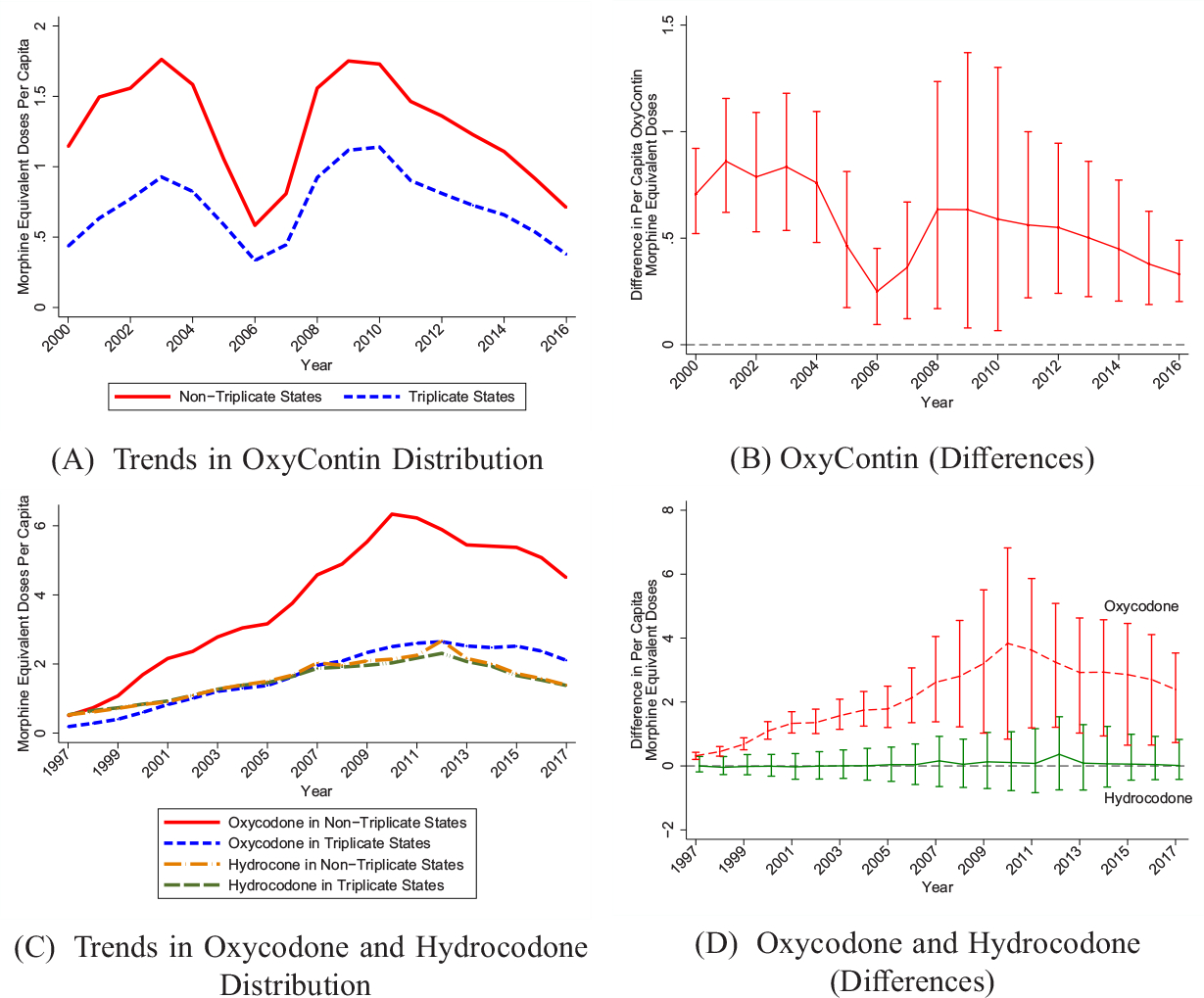

We first show that nontriplicate states were more exposed to the introduction of OxyContin as measured by OxyContin distribution per capita in the ARCOS data. Figure III, Panel A shows the raw trends for OxyContin distribution per capita, and Panel B shows the differences between nontriplicate and triplicate states with 95% confidence intervals. In 2000, there is over 2.5 times more OxyContin distribution per capita in nontriplicate states compared with triplicate states. These large and statistically significant differences persist through 2016.

Figure III.

Differences in Opioid Distribution by Triplicate Status

We use ARCOS data, converted to morphine equivalent doses. Panel A shows raw (per capita) means for OxyContin. Panel C shows raw (per capita) means for oxycodone and hydrocodone in separate trend lines. Estimates in Panels B and D represent cross-sectional differences corresponding to Panels A and C, respectively. 95% confidence intervals are generated using a clustered (at state) wild bootstrap. All figures are population weighted.

In Online Appendix Figure A3, we study two complementary data sources that allow us to observe OxyContin prescriptions for earlier years. Panel A shows trends for Medicaid OxyContin prescriptions per 1,000 beneficiaries for 1996–2005. Panel B shows OxyContin prescriptions per 1,000 people using the MEPS for 1996–2016. We again observe much higher rates of OxyContin prescriptions in nontriplicate states. OxyContin prescribing increases rapidly for several years after its launch; however, there is a reduction in OxyContin prescriptions in 2005–2006.33 OxyContin prescribing decreases again after Purdue Pharma replaced the original formulation with an abuse-deterrent version in 2010. However, nontriplicate states continue to experience additional OxyContin use throughout these downturns.

We also examine patterns of initial “adoption” of OxyContin. In Online Appendix Figure A4, we show the distribution of OxyContin supply per capita across states using the earliest years of Medicaid and ARCOS data. For both measures, the triplicate states cluster close to the bottom of the distribution. Four of the triplicate states (CA, IL, NY, TX) are among the five states with the lowest number of OxyContin prescriptions per capita in 1996.34 The pattern is similar in the ARCOS data. Triplicate states initially had some of the lowest rates of OxyContin adoption.

V.B. Effects of Triplicate Status on Use of Other Opioids

We examine differences in the use of other prescription opioids across triplicate and nontriplicate states that could potentially contribute to differences in overdose death trends. Using ARCOS data, Figure III, Panel C shows raw trends in oxycodone and hydrocodone distribution in MEDs, which adjusts for their potency. Hydrocodone (e.g., Vicodin) is a substitute for oxycodone, but it was primarily classified as a Schedule III drug and would not be subject to triplicate programs, which cover Schedule II drugs.35 Panel D plots differences between the two sets of states for each of these opioid drugs along with 95% confidence intervals. Remarkably, per capita hydrocodone distribution is nearly identical in triplicate and nontriplicate states over the whole time period. However, there are large and statistically significant differences in oxycodone distribution between triplicate and nontriplicate states. Finding differences in oxycodone, but not hydrocodone, suggests that these differences are caused by triplicate status.

As shown in Figure III, the differences in oxycodone distribution (Panel D) exceed the differences observed for OxyContin alone (Panel B) and grow over time; this growth suggests spillovers of OxyContin’s promotion on the use of other oxycodone products (e.g., combination products, such as Percocet). We observe evidence of spillovers to other types of oxycodone studying prescriptions in Medicaid (our only data set with pre-1996 prescriptions). We provide event study estimates in Online Appendix Figure A5. The outcome is Medicaid oxycodone prescriptions, excluding OxyContin, per 1,000 beneficiaries. We observe no difference across states before 1996. After 1996, nontriplicate states increased their oxycodone prescriptions, and this effect persists through the end of the sample period. Such spillovers are likely generated by Purdue Pharma’s marketing strategies that aimed to expand the opioid market by normalizing the use of strong opioids for noncancer chronic pain and creating the message that opioids carry a low risk of addiction (Van Zee 2009).36 Moreover, individuals introduced to OxyContin will often transition to using other opioids, especially similar products containing oxycodone.37

Finally, in Online Appendix Figure A6, we show trends in the rates of misuse of OxyContin versus all other pain relievers using the NSDUH for 2004–2013. There are large differences in OxyContin misuse (Panel A) across triplicate and nontriplicate states, but no meaningful differences in the misuse of other pain relievers excluding OxyContin (Panel B). Taken together, the above results are consistent with any differences in overdose rates being primarily attributable to OxyContin.

V.C. Effects of OxyContin Use on Drug Overdose Deaths

1. Overall Results.

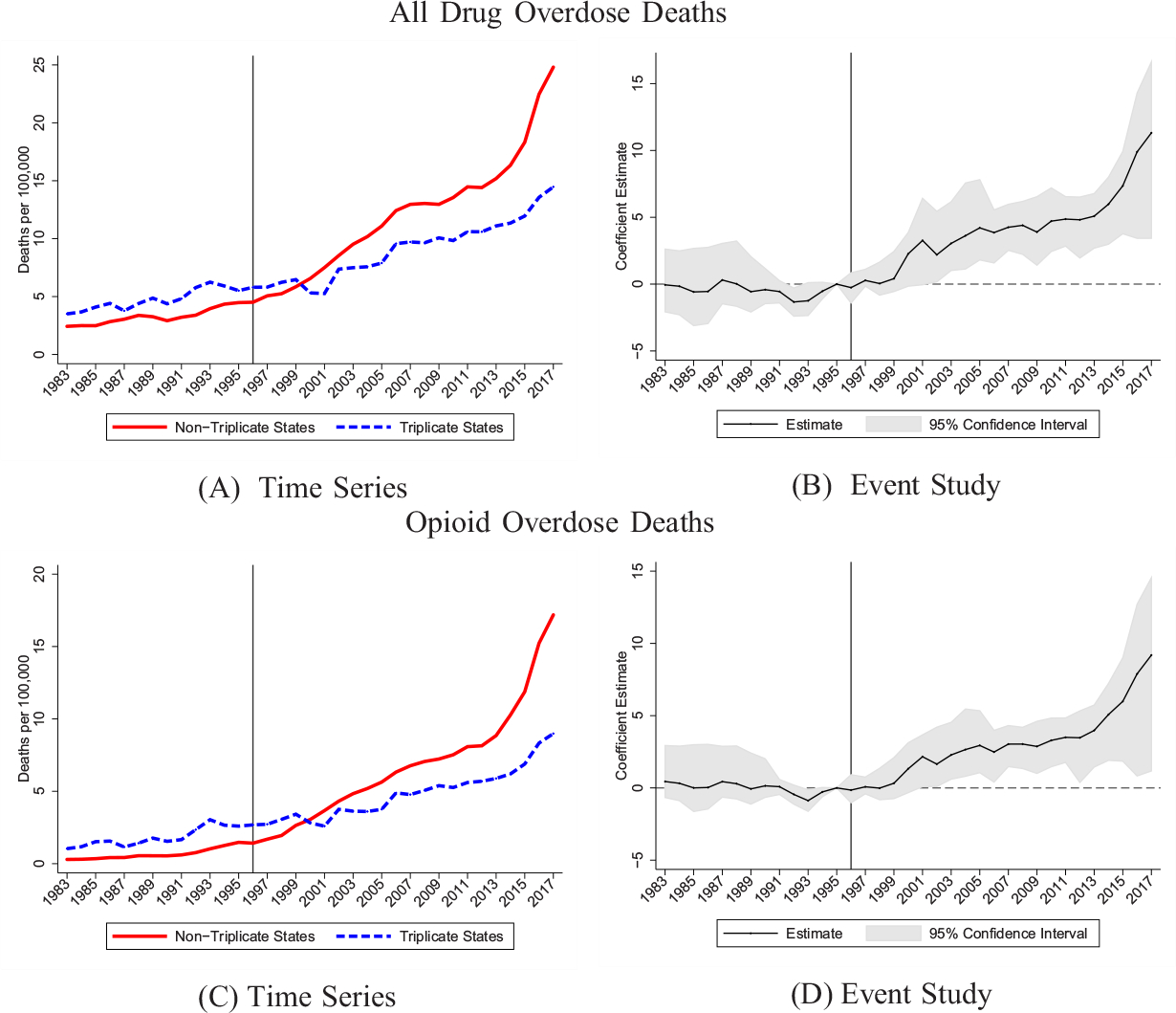

We examine whether this differential OxyContin use led to differences in drug overdose deaths over time. In Figure IV, we show raw trends in drug overdose death rates for triplicate and nontriplicate states. We also show coefficients and 95% confidence intervals from estimating the event study specification in equation (1). As is evident in Panel A, the trends in overdose death rates were similar across the two sets of states prior to the introduction of OxyContin. Triplicate states had higher overdose rates initially, but this flips within a few years of the launch. Nontriplicate states see rapid growth in overdose deaths, whereas the trend for triplicate states is much flatter. The corresponding event study estimates, shown in Panel B, are close to zero and largely statistically insignificant prior to 1996, but then the estimates diverge and become statistically significant.38 The event study estimate for 1997 indicates that overdose deaths in nontriplicate states increased by 0.28 deaths per 100,000 compared with triplicate states. These effects increase to a statistically significant 2.20 deaths per 100,000 in 2002 and 11.32 deaths per 100,000 by 2017.39 It is not surprising that these mortality effects are delayed, given the expansions in OxyContin promotion and sales over time and the FDA’s relabeling in 2001 that expanded its market for chronic use.40 In addition, it would take time for a person to transition from an initial prescription for OxyContin to dependence and an overdose.41

Figure IV.

Drug Overdose Death Rates by Triplicate Status

We use geocoded NVSS data to construct all drug overdose and opioid overdose deaths per 100,000. See Section III.A for exact ICD codes used in each period. Event study models include state and year fixed effects. 95% confidence intervals are generated using a clustered (at state) wild bootstrap. Estimates are normalized to zero in 1995. Weighted by population.

We find similar patterns for opioid-related deaths in Figure IV, Panels C and D, demonstrating that the overall drug overdose effects are largely driven by opioids. The event study estimates are similar without population weights or when we condition on covariates (see Online Appendix Figure A7). The results are also robust to adding census region-year interactions to account for geographic differences in overdose rate growth (see Online Appendix Figure A8).

To quantify the magnitude of these effects, in Table I, we present difference-in-differences estimates for the three postperiods from equation (2).42 In column (1), we present unweighted estimates. In column (2), we present population-weighted estimates, which are slightly larger. Relative to the baseline period, we estimate that nontriplicate states experienced an additional 1.3 overdose deaths per 100,000 people in the earliest years after the launch (1996–2000), which is statistically significant at the 1% level. The “counterfactual” fatal overdose rate for nontriplicates during this time period was 4.2 per 100,000, implying a 31% increase.43 The estimated effect grows to 4.5 in 2001–2010, representing a 68% increase, and 7.8 in 2011–2017, a 76% increase over the counterfactual. Column (3) shows that the estimates are robust to including time-varying covariates. Column (4) shows robustness to census region-year interactions.

TABLE I.

Difference-in-Differences Estimates: Drug Overdose Death Rate

| Nontriplicate × | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Panel A: All drug overdose deaths per 100,000 | ||||

| 1996–2000 | 1.173** [0.390, 2.374] | 1.290*** [0.421, 2.449] | 1.267** [0.062, 2.274] | 1.229** [0.017, 2.483] |

| 2001–2010 | 3.667** [1.521, 6.210] | 4.488*** [2.201, 6.395] | 3.561*** [1.321, 5.687] | 3.232** [1.011, 5.318] |

| 2011–2017 | 6.061** [2.812, 9.371] | 7.806*** [4.023, 10.439] | 5.240*** [3.213, 7.274] | 4.714*** [1.811, 7.253] |

| Joint p-value | .016 | .000 | .001 | .015 |

| Weighted | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Covariates | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Region-time dummies | No | No | No | Yes |

| Mean 1991–1995 | 3.890 | 4.436 | 4.436 | 4.436 |

| N | 1,377 | 1,377 | 1,377 | 1,377 |

| Panel B: Opioid overdose deaths per 100,000 | ||||

| 1996–2000 | 0.634** [0.083, 1.573] | 0.620** [0.112, 1.614] | 0.725 [−0.244, 1.621] | 0.821* [−0.189, 1.761] |

| 2001–2010 | 2.614** [1.115, 4.382] | 2.940*** [1.232, 4.249] | 2.081** [0.151, 4.192] | 2.271** [0.297, 4.402] |

| 2011–2017 | 5.002** [1.480, 8.292] | 5.899*** [1.764, 8.895] | 3.334*** [1.415, 5.613] | 3.284** [0.703, 6.012] |

| Joint p-value | .039 | .010 | .034 | .118 |

| Weighted | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Covariates | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Region-time dummies | No | No | No | Yes |

| Mean 1991–1995 | 1.189 | 1.476 | 1.476 | 1.476 |

| N | 1,377 | 1,377 | 1,377 | 1,377 |

Notes:

Significance 1%

significance 5%

significance 10%.

Outcome is all drug overdose deaths or opioid overdose deaths per 100,000. The reported coefficients refer to the interaction of the given time period and an indicator for whether the state did not have a triplicate program in 1996. Estimates are relative to preperiod 1991–1995. 95% confidence intervals reported in brackets are estimated by clustered (by state) wild bootstrap. All models include state and year fixed effects. Covariates include the fraction non-Hispanic white, fraction non-Hispanic Black, fraction Hispanic, log of population, fraction with college degree, fraction ages 25–44, fraction ages 45–64, and fraction ages 65+. “Joint p-value” refers to the p-value from ajoint hypothesis test that all three nontriplicate post effects are equal to zero and is also estimated using a restricted wild bootstrap.

The bottom panel of Table I shows the results for opioid-related overdose deaths. The patterns are similar. The 1996–2000 estimate in column (2) implies a 40% increase for nontriplicate states and the 2011–2017 estimate indicates an increase over 100%.

2. State-Specific Results.

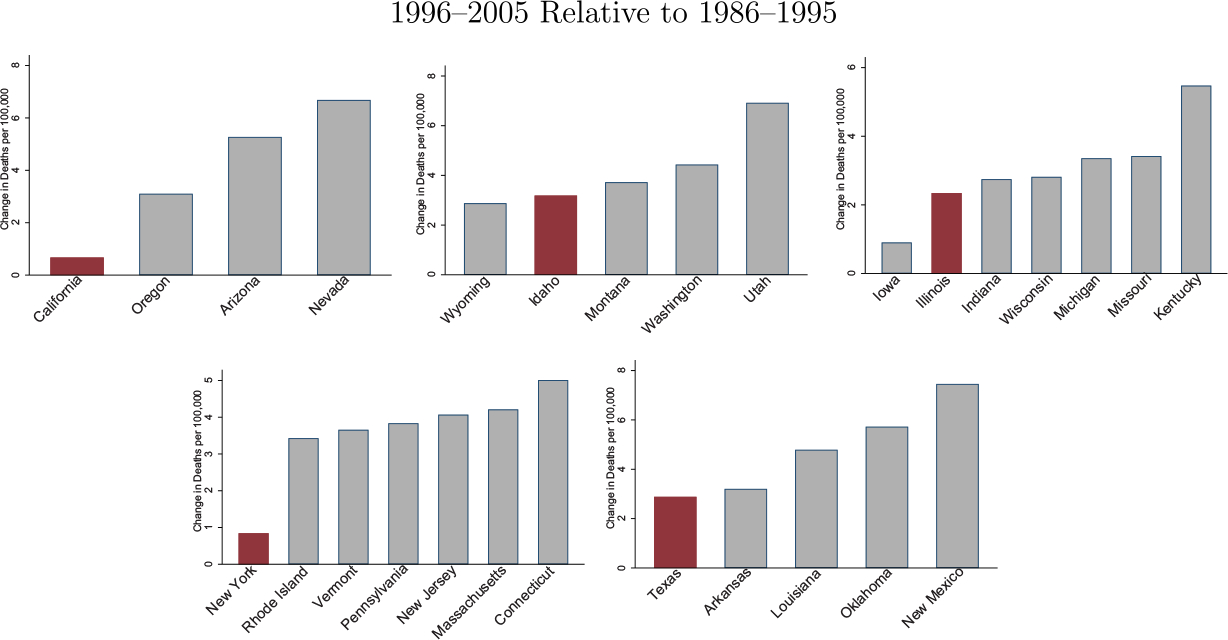

We examine the mortality effects for each state separately. In Figure V, we compare the growth in overdose death rates for each triplicate state with its bordering neighbor states for the 10 years before and after OxyContin’s introduction. Online Appendix Figure A9 repeats this exercise but uses the most recent 10 years. In almost every case, the triplicate state had the lowest growth in drug overdose rates compared with its neighbors.44 Thus, the overall results are not driven by a single outlier triplicate state experiencing uniquely low growth in overdose deaths. Instead, we observe this pattern for all triplicate states. This suggests that it was the triplicate program, not other characteristics of the states or regions, that drove the uniquely low mortality growth rates.

Figure V.

Drug Overdose Death Rate Changes: Triplicate States versus Bordering States

We construct the change in all drug overdose deaths per 100,000 for 1996–2005 relative to 1986–1995. We plot this change for each triplicate state relative to its bordering states.

3. Heroin and Fentanyl Overdose Deaths.

We examine trends in overdose deaths by the type of opioid. Online Appendix Figure A10 shows cross-sectional annual differences in opioid-related overdose deaths for natural and semisynthetic opioids, heroin, and synthetic opioids for 1999–2017. Prior to 2010, the only meaningful difference in overdose mortality between triplicate and nontriplicate states was for natural and semisynthetic opioids, the category that includes OxyContin. After 2010, we observe a large relative increase in heroin-related fatal overdoses in nontriplicate states, although the differences are not statistically significant. We also find that sharp differences in synthetic opioid overdose death rates emerged in 2014. These patterns are consistent with the main hypothesis of this article, combined with the earlier findings in Alpert, Powell, and Pacula (2018) and Evans, Lieber, and Power (2019). In 2010, Purdue Pharma introduced an abuse-deterrent version of OxyContin, and the original formulation was discontinued. This earlier work showed that states more exposed to OxyContin (measured by having high prereformulation rates of OxyContin misuse) experienced much faster growth in heroin deaths after 2010 as people substituted from OxyContin to heroin. These states later saw faster growth in synthetic opioid deaths (Powell and Pacula 2021) when fentanyl became mixed with the United States heroin supply (Ciccarone 2017; Pardo et al. 2019). The timing of these drug-specific trends shows that the introduction of OxyContin affected drug overdose deaths through each wave of the opioid crisis. States less exposed to OxyContin’s introduction were also (as predicted by the prior studies) less affected by transitions to illicit drugs after OxyContin’s reformulation in later years of the opioid crisis.

V.D. Mechanisms

1. Effects of Triplicate Programs or Marketing?

We consider two possible mechanisms for the lower OxyContin use and overdose death rates in triplicate states. First, triplicate programs themselves and the prescribing culture that developed from them may have independently protected states against OxyContin adoption and overdose growth, even after these programs were discontinued. Second, these effects could be due to the lack of initial OxyContin marketing targeted to triplicate states.

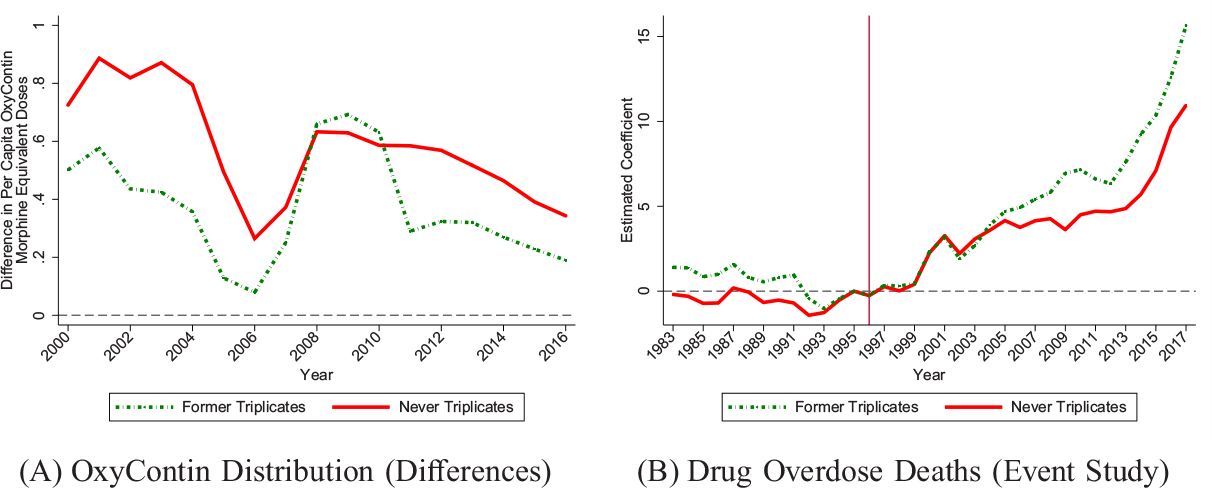

We conducted two tests to disentangle these mechanisms. In the first test, we compare triplicate states to two former triplicate states—Michigan and Indiana—that had discontinued their triplicate programs in 1994, prior to OxyContin’s launch. These former triplicate states serve as a useful counterfactual because they show the long-term effects of having a triplicate program, independent of marketing effects.45 In Figure VI, we reestimate our main results while permitting different effects for two groups of nontriplicate states: (i) former triplicate states and (ii) never-triplicate states. Using the five triplicate states as the comparison group, Panel A shows estimates of cross-sectional differences in OxyContin distribution for former triplicate states and never-triplicate states relative to triplicate states. Panel B estimates our main event study for drug overdose death rates, allowing separate coefficients for former triplicate and never-triplicate states. These figures show that triplicate states had much lower rates of OxyContin use compared to former triplicate states that eliminated their programs just two years before OxyContin’s launch.46 Triplicate programs also experienced persistently lower overdose rate growth relative to the former triplicate states. In fact, former triplicate states had nearly identical overdose trends as states that never had triplicate programs. Thus, the triplicate programs themselves do not appear to explain the enduringly low overdose rates because these programs are only predictive of low overdose rate growth if they were in effect in 1996, when Purdue Pharma targeted its marketing based on triplicate status. This evidence points to marketing practices as the main driver of the overdose trends.47

Figure VI.

Former Triplicate States: OxyContin Distribution and Drug Overdose Deaths

Panel A estimates the annual differences in OxyContin morphine equivalent doses per capita between never-triplicate and triplicate states and the annual differences between former-triplicate and triplicate states. Panel B estimates our main event study for all drug overdoses per 100,000 (as in Figure IV) using the triplicate states as the comparison group, allowing separate coefficients for never-triplicate states and former-triplicate states. The event study model estimated in Panel B includes state and year fixed effects. Regressions are population weighted.

In the second test in Online Appendix Figure A13, we compare triplicate states to five nontriplicate states that had similar initial prescribing cultures. Specifically, we select states with the lowest oxycodone prescribing rates in 1991–1995 (see Online Appendix Table A4 for list of states). For OxyContin distribution (Panel A) and overdose death rates (Panel B), the estimates are similar to the main results. Triplicate states used OxyContin at much lower rates and had lower overdose growth compared to nontriplicate states that initially had similar prescribing habits. These results are difficult to explain by entrenched prescribing culture, further supporting the marketing channel.

2. Persistence in Marketing Effects.

The persistent differences in OxyContin use and overdose deaths following the elimination of all triplicate programs by 2004 are consistent with serial correlation in Purdue Pharma’s marketing practices. As discussed in Section II, the company’s strategy was to target sales force visits to the top deciles of physicians based on past prescribing volume.48 Thus, given initial differences in marketing and the resulting higher prescribing in nontriplicate states, nontriplicate states would in turn continue to receive more marketing in future years (as shown previously in Figure II) and higher prescribing would persist. Without these marketing differences, it is difficult to explain why the triplicate states as of 1996 experienced such enduringly low overdose growth after eliminating their triplicate programs, but states that had discontinued their programs just two years before the launch experienced overdose trends almost identical to states that never had these programs.

It also does not appear that Purdue Pharma significantly increased marketing to triplicate states after their programs were eliminated. In Online Appendix Figure A14, we plot estimates from an event study examining Medicaid prescriptions around triplicate repeal dates.49 We observe a downward trend over time, consistent with the general separation between nontriplicate and triplicate states due to marketing, but no independent effect of triplicate repeal. Although this does not rule out subsequent targeting of marketing to the triplicate states, it suggests that there was not a dramatic increase in marketing intensity. The CMS Open Payments data shows that there is still a large gap in marketing across triplicate and nontriplicate states that has continued to the present day. The likely reason for this is that Purdue Pharma’s marketing strategy was to target the highest prescribers, which, given earlier targeting, were predominantly in nontriplicate states.50 In addition, even if marketing did increase after repeal, it would likely be less effective than during the initial campaign, which could also explain the low demand response.51

VI. Robustness Tests

In this section, we explore alternative explanations for our findings and test the robustness of our results. The main set of robustness tests for drug overdose deaths are presented in Table II (see Online Appendix Table A5 for opioid-related overdose deaths).

TABLE II.

Robustness Tests: Drug Overdose Death Rate

| Nontriplicate × | Baseline results (1) |

Select on population size (2) |

Select on PDMP states in 1996 (3) |

Control for policy variables (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 1996–2000 | 1.267** [0.062, 2.274] | 2.919** [0.452, 5.067] | 2.163 [−0.978, 4.828] | 1.348** [0.176, 2.453] |

| 2001–2010 | 3.561*** [1.321, 5.687] | 5.543*** [2.671, 8.591] | 5.869* [−0.711, 11.369] | 3.628*** [1.671, 5.322] |

| 2011–2017 | 5.240*** [3.213, 7.274] | 6.045** [0.535, 12.242] | 9.299*** [3.528, 14.946] | 5.808*** [3.528, 8.030] |

| Joint p-value | .001 | .073 | .005 | .000 |

| Mean 1991–1995 | 4.436 | 5.090 | 5.294 | 4.436 |

| N | 1,377 | 216 | 405 | 1,377 |

Notes:

Significance 1%

significance 5%

significance 10%.

Outcome is all drug overdose deaths per 100,000. The reported coefficients refer to the interaction of the given time period and an indicator for whether the state did not have a triplicate program in 1996. Estimates are relative to preperiod 1991–1995. 95% confidence intervals reported in brackets are estimated by clustered (by state) wild bootstrap. All models include state and year fixed effects and time-varying covariates (see Table I for details). Column (1) repeats the column (3) results from Table I. Column (2) selects on the four nontriplicate states with the largest populations in 1990 along with the four largest triplicate states. Column (3) selects on states with some form of PDMP (triplicate, duplicate, electronic) in 1996. Column (4) includes policy controls for PDMPs (any PDMP, electronic PDMP, “must access” PDMPs), pain clinic regulation, medical marijuana laws, and operational/legal medical marijuana dispensaries. “Joint p-value” refers to the p-value from a joint hypothesis test that all three nontriplicate post effects are equal to zero and is also estimated using a restricted wild bootstrap.

VI.A. Alternative Explanations

1. Population Size.

It is notable that four of the triplicate states are among the largest states in the country. One concern is that states with large populations may have experienced different trends in overdose deaths independent of their triplicate status. In Table II, column (2), we select the four largest nontriplicate states (FL, PA, OH, and MI) as comparison states for the four largest triplicate states.52 The estimates are larger than the main estimates, indicating that triplicate states have uniquely low overdose growth, even compared with the largest nontriplicate states.

A related concern is that the triplicate states are more urban than nontriplicate states. In Online Appendix Figure A15, Panel A, we replicate our event study at the county level with county fixed effects, selecting only on urban counties (826 counties).53 In Panel B, we select counties with the largest population size: “central counties of metro areas of 1 million population or more” (175 counties).54 The patterns are remarkably similar to our main results, showing that triplicate status predicts large differences in overdose deaths among the largest metropolitan areas in the country.

2. Adoption of Other Policies.

Triplicate states were some of the earliest adopters of drug monitoring programs and were potentially at the frontier of reducing prescription drug abuse in the years following OxyContin’s introduction. If triplicate states followed different policy paths that addressed opioid misuse more effectively than the policies in nontriplicate states, this could be confounding our results. In Table II, column (3) we examine drug overdose death rates in triplicate states compared to states with other types of PDMPs in 1996—electronic PDMPs and duplicate programs (Horwitz et al. 2018). States with other types of monitoring programs might also be “ahead of the curve” in moderating opioid misuse, and we would expect them to experience slower growth in overdose death rates. However, the estimates increase when we select on this sample of states. As a complementary approach, in column (4), we replicate the difference-in-differences analysis for the full sample of states while controlling for a set of opioid-related policy variables.55 Again, the results are similar implying that triplicate states did not adopt systematically different opioid policies after 1996.56

3. Deaths of Despair.

The deaths of despair hypothesis discussed in Case and Deaton (2015, 2017) suggests that we would have observed an increase in mortality even in the absence of a rise in opioid supply because of worsening cultural and economic factors. In this section, we study other types of deaths of despair: suicides (excluding overdoses) and alcohol-related liver deaths. Online Appendix Figure A17 presents the event study estimates for these outcomes by triplicate status. Suicides trend upward in the nontriplicate states relative to the triplicate states beginning in the preperiod and continuing through the end of the sample period (Panel A). Alcohol-related liver deaths also exhibit preexisting trends that continue throughout the period (Panel B). We present detrended event studies in Panels C and D. Overall, we find little evidence that other deaths of despair follow the same patterns as drug overdose deaths across triplicate and nontriplicate states, suggesting that there is not a confounding underlying factor that is common across these causes of death. This shows that OxyContin played a crucial independent role in the opioid crisis. Moreover, the lack of a decline in suicides and alcohol-related liver mortality suggests that fatal opioid overdoses were not substitutes for these types of deaths.

4. Additional Alternative Explanations.

We conducted numerous additional robustness tests that are discussed in detail in Online Appendix C. Our results are unchanged if we account for changes in economic conditions by controlling for the unemployment rate or for economic shocks using Bartik-type instruments. The results are also unaffected if we exclude fatal overdoses involving unspecified narcotics. Finally, we implement a leave-one-out analysis where we exclude each state in turn. The findings are not driven by a single triplicate or nontriplicate state.

VI.B. Parallel Trends Assumption

In this section, we further evaluate the parallel trends assumption in our main analysis and consider the robustness of the results to possible violations of this assumption.

1. Synthetic Controls.

First, we use a synthetic control approach (Abadie, Diamond, and Hainmueller 2010, 2015) to account for systematic differences in pretreatment outcomes. We discuss details of the implementation in Online Appendix D. Online Appendix Table D1 presents estimates for our three postperiods. The estimates are close to our main difference-in-differences estimates and statistically significant at the 1% level. For example, when we population weight the state-specific estimates (column (2)), we estimate that nontriplicate states experienced a differential increase in overdoses per 100,000 of 2.1 in 1996–2000, 5.1 in 2001–2010, and 6.9 in 2011–2017. The similarity between the main estimates and the synthetic control estimates suggests that the main results are not driven by any preexisting differences in levels or trends between triplicate and nontriplicate states. Online Appendix Figure D1 presents the results graphically. We observe little evidence of pretreatment differences between the triplicate states and their synthetic counterfactuals.

We compare 10-year overdose death rate growth in each triplicate state to its synthetic control state in a manner similar to Figure V (see Online Appendix Figure D2). Each triplicate state had much lower growth than its corresponding synthetic control.

2. Permutation Test.

Second, we consider the uniqueness of the post-OxyContin overdose rate trends for triplicate states. We conduct a permutation-like test where we randomly assign triplicate status to five nontriplicate states and then estimate placebo effects for three postperiods. We discuss this procedure further in Online Appendix E. We present a histogram representing the distribution of placebo estimates in Online Appendix Figure E1 and the distribution of t-statistics (recommended in MacKinnon and Webb 2020) in Online Appendix Figure E2.

In comparing our main estimates to the placebo estimates, we never observe differences in overdose rates between triplicate and nontriplicate states as large as our actual estimated effects. Our main estimates are outliers, ranking first in the placebo distribution for each time period. In fact, it is impossible to find any combination of five nontriplicate states that experienced the same low rate of overdose rate growth as the triplicate states in each of our three postperiods.

We also study whether the triplicate states had uniquely low overdose rate growth before 1996. We randomly assign triplicate status to five nontriplicate states and estimate the differential growth in overdoses between 1991 and 1995. As shown in Online Appendix Figure E3, the estimates for the actual triplicate states are in the middle of this placebo distribution. Combined with the results of the previous permutation tests, this implies that even if we selected nontriplicate states in which the pretrend was similar to the pretrend for triplicate states, triplicate states still have uniquely low growth in overdose deaths over the entire postperiod.

3. Effect of Cocaine Deaths on Trends.

Third, in Online Appendix Figure A18, we exclude overdoses involving cocaine to evaluate the effect of the crack epidemic on pre-1996 trends. The differences between triplicate and nontriplicate states in the preperiod become even smaller, but the post-1996 effects remain. Conversely, as a placebo test, we show event study results for cocaine overdose rates alone in Online Appendix Figure A19. We do not observe a comparable posttreatment upward trend, suggesting that this rise was unique to overdoses involving opioids.

4. Deviations from Parallel Trends.

Finally, we test the sensitivity of our estimates to deviations from the parallel trend assumption using the method of Rambachan and Roth (2020).57 This approach relaxes the parallel trends assumption by imposing inequality constraints that permit deviations from preexisting (treatment-specific) linear trends in the postperiod. Specifically, if nontriplicates states experience differential annual linear growth prior to treatment equal to θ, then the inequality constraints permit posttreatment differential annual secular growth between θ − M and θ + M. In Online Appendix Figure A21, we plot confidence intervals for the three aggregated postperiods for different values of M.58 The estimates in all time periods are statistically different from zero when including a treatment group-specific linear trend (M = 0) and even when permitting annual deviations from a linear trend by as much as 0.015.

To interpret these magnitudes, Rambachan and Roth (2020) recommend benchmarking the results to outcome patterns in nontreated units. This practice relates to our permutation test. We replicate Online Appendix Figure A21 but assign placebo triplicate status to the five nontriplicate states with the lowest overdose rate growth. This exercise is designed to find the highest placebo values of M for the three postperiods in which it is still possible to statistically reject zero overdose rate growth for nontriplicate states. In Online Appendix Figure A22, we show that the maximum values of M for which it is possible to reject zero are smaller than those observed in Online Appendix Figure A21 for the true triplicate states. This evidence suggests that it would be extremely rare for the relative trend shift observed for triplicate states to occur randomly.

VII. Conclusion

Despite the importance of the opioid crisis, there is little empirical work exploring its initial causes. This article demonstrates the importance of the introduction and marketing of OxyContin in 1996 as a key driver of the opioid crisis. We show this by exploiting early variation in OxyContin’s promotion and market entry due to state triplicate prescription programs. Our results imply striking differences throughout the opioid crisis stemming from variation in these initial conditions. States with more exposure to OxyContin’s introduction experienced higher growth in overdose deaths in every year since its launch in 1996. Our estimates (from Figure IV) show that nontriplicate states would have experienced 4.21 fewer drug overdose deaths per 100,000 on average from 1996 to 2017 if they had been triplicate states and 3.16 fewer opioid overdose deaths per 100,000. Over this time period, nontriplicate states had an average of 12.32 fatal overdoses per 100,000 annually, and 6.98 of those involved opioids. This implies that if nontriplicate states had the same initial exposure to OxyContin’s introduction as triplicate states, they would have had 34% fewer drug overdose deaths and 45% fewer opioid overdose deaths on average from 1996 to 2017.

We use our results to provide a back-of-the-envelope calculation of how much of the growth in drug overdose deaths can be accounted for by the introduction and marketing of OxyContin. This exercise is explained in detail in Online Appendix F. Online Appendix Figure F1 shows the estimated counterfactual national overdose death rate trend in the absence of OxyContin. This extrapolation exercise suggests that the introduction of OxyContin explains 79% of the rise in the overdose death rate since 1996. In the absence of OxyContin, overdose death rate levels would be substantially lower and unlikely to rise to the level of an opioid crisis. In fact, the estimated counterfactual overdose rate does not rise above the 1995 overdose death rate until 2006. We conduct a similar extrapolation exercise for all-cause mortality focusing on non-Hispanic whites ages 45–54, a population highlighted in Case and Deaton (2015) as experiencing the largest reversal in mortality trends after 1998. For this population, we estimate that OxyContin’s introduction can explain about one-third of the rise in all-cause mortality since 1998.

Our estimates capture both the direct and indirect consequences of initial exposure to OxyContin’s introduction, including spillovers of OxyContin promotion to other opioid drugs and transitions to heroin and fentanyl in the later waves of the epidemic. They also internalize downstream indirect effects of OxyContin’s introduction on the behaviors of other entities in the supply chain—distributors, pharmacies, and doctors—which may have further amplified OxyContin’s effects. Our findings do not rule out the possibility that economic and cultural factors also contributed to a meaningful share of the rise in drug-related mortality. Also, although these results quantify the harms associated with OxyContin use, our analysis does not speak to the potential benefits of improved opioid access through the introduction of OxyContin. Opioids may be effective pain management tools in some cases, and we do not attempt to estimate the gains from pain reduction stemming from OxyContin’s launch.

Finally, the evidence in this article suggests that Purdue Pharma’s marketing practices, in particular, played an important role in explaining growth in drug overdose rates. When triplicate states are compared to states that had recently eliminated their triplicate programs or other states with similar prior oxycodone prescribing rates, they still have uniquely low overdose death rate growth. This suggests that it was not the triplicate programs themselves that independently influenced OxyContin adoption. Instead, the evidence is more consistent with the idea that differences in marketing led to persistent differences in overdose death rate growth. Overall, we find strong evidence that the marketing practices for OxyContin interacted with state-level policy conditions led to dramatically reduced overdose death rates in triplicate states. Even though triplicate programs are now obsolete, by deterring OxyContin’s widespread introduction in 1996, these programs protected some states against the long-term fatal overdose trends experienced by most other states.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Molly Candon, Matthew Harris, Mireille Jacobson, Robert Kaestner, Rosalie Liccardo Pacula, Harold Pollack, Paul Steinberg, and seminar and conference participants at the Bates White Life Sciences Symposium, Becker Friedman Institute Conference on the Economics of the Opioid Epidemic, Cal Poly State University, Cornell VERB, Federal Reserve Board, Illinois, Johns Hopkins, Notre Dame, RAND, Temple, Toronto, Tulane, USC, Health and Labor Market Effects of Public Policy at UCSB, iHEA, IIMA, Midwest Health Economics Conference, Population Health Science Research Workshop, NBER Health Care Winter Meeting, and NBER Summer Institute Crime Meeting for helpful feedback. For help obtaining some of the unsealed court documents, we thank Caitlin Esch at Marketplace, Nicholas Weilhammer in the Office of Public Records for the Office of the Attorney General of Florida, La Dona Jensen in the Office of the Attorney General of Washington, and Judge Booker T. Stephens of West Virginia. We thank Ray Kuntz for assistance with the restricted MEPS data. Powell gratefully acknowledges financial support from NIDA (P50DA046351) and the CDC (R01CE02999). Evans gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts at the University of Notre Dame.

Footnotes

Some of these overdoses may involve nonopioid drugs in addition to opioids. Ruhm (2019b) documents the recent rise in nonopioid overdose death rates.

The American Pain Society launched an influential campaign declaring pain as the “fifth vital sign”; in response, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) revised its guidelines in 2001, requiring that doctors assess pain along with other vitals during medical visits (Phillips 2000).

In addition, Finkelstein, Gentzkow, and Williams (2018) find that place-specific factors are important determinants of opioid abuse rather than individual-level factors; however, their study design does not allow them to separate out the relative importance of local economic and cultural conditions from opioid access.

The CDC marks the first wave of the crisis as beginning in the 1990s (https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html, last accessed December 1, 2020). Maclean et al. (2020) date the first wave beginning in the mid-1990s.

See the 2019 New York complaint: https://ag.ny.gov/sites/default/files/oag_opioid_lawsuit.pdf

For example, an attorney for Purdue Pharma argues that the opioid epidemic “is not caused by Purdue’s sale of its legal, FDA-regulated medications, but rather by doctors who wrote improper prescriptions and/or by third parties who caused persons without valid and medically necessary prescriptions to get opioid medications or illegal street drugs. Purdue has no control over those persons” (Satterfield 2018).

Purdue Pharma also promoted OxyContin through a variety of other channels, such as sponsoring pain-related educational programs and conferences, distributing coupons and gifts, and advertising in medical journals.

Purdue Pharma conducted internal research showing that its promotional activities were effective. From Commonwealth of Massachusetts (2019), the effectiveness of the sales visits was corroborated by an outside consulting firm: “McKinsey confirmed that Purdue’s sales visits generated opioid prescriptions” (137); from Commonwealth of Massachusetts (2018): “Purdue knew its sales push drove patients to higher doses … Purdue’s business plans emphasized that ‘OxyContin is promotional sensitive, specifically with the higher doses, and recent research findings reinforce the value of sales calls”‘ (19); “Director Richard Sackler testified that the sales representatives were the main way that Purdue promoted its opioids. He testified that the key to getting doctors to prescribe and keep prescribing Purdue opioids was regular visits from the sales force” (50).

For example, marketing materials relied heavily on a 100-word letter to the editor (Porter and Jick 1980) to support the claim that the risk of addiction among opioid users was “much less than one percent.”

The documents come from three main sources. In November 2001, the Florida attorney general opened an investigation into Purdue Pharma’s marketing tactics. The investigation was closed about a year later. Purdue Pharma paid the state of Florida a $2 million settlement. We also received documents from the State of Washington v. Purdue Pharma L.P. et al. (filed September 2017) and State of West Virginia v. Purdue Pharma et al. (filed June 11, 2001, settled in 2004).

Must-access PDMPs have been shown to reduce opioid prescribing, while nonmandate PDMPs have muted effects (Buchmueller and Carey 2018). Notably, similar to triplicate programs, must-access PDMPs impose a hassle cost on the prescriber, which can explain a large share of the prescribing reduction from these programs (Alpert, Jacobson, and Dykstra 2020). The hassle costs were even higher for the triplicate programs, which may explain their large deterrent effects. Doctors needed to purchase the triplicate forms and store the written prescriptions for years. In 2001, only 57.6% of physicians in California requested triplicate prescription forms, implying that the other 42.4% were not even capable of prescribing Schedule II opioids (Fishman et al. 2004).

In one case in the internal documents we reviewed, there is an incorrect reference to “nine triplicate states” when discussing retail pharmacy distribution. It is possible they were referring to the nine states with paper-based monitoring systems (including duplicate and single-copy programs), because this statement appears in the context of pharmacists’ concerns about the “voluminous paperwork” required in these states, which would be a consideration with any paper-based system. To the degree that Purdue Pharma was also concerned about other paper-based programs and marketed less in these states, our results will be attenuated.

Idaho adopted its program in 1967, switching to a duplicate program in 1997 (Joranson et al. 2002; Fishman et al. 2004, see also https://legislature.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/OPE/Reports/r9901.pdf). Illinois enacted its triplicate program in 1961, converting to an electronic system in 2000 (see https://www.isms.org/opioidplan/). New York enacted a triplicate program in 1972 (Joranson et al. 2002), which ended in 2001 (NY Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement, personal communication, May 3, 2019). Texas adopted a triplicate system in 1982 (Sigler et al. 1984), converting to an electronic system in 1999 (see https://www.pharmacy.texas.gov/DPS.asp).

Indiana’s triplicate program began in 1987, but it was replaced with an electronic and single-copy program in 1994 (Joranson et al. 2002). Michigan enacted a triplicate program in 1988 but it ended in 1994 (Joranson et al. 2002). Washington also adopted a triplicate program, but because of limited funding, triplicate forms were required only for physicians disciplined for drug-related violations (Simoni-Wastila and Tompkins 2001; Fishman et al. 2004).

We include these two former triplicate states in the set of nontriplicate states. Purdue Pharma’s internal documents refer to states that have triplicate programs, which would exclude states that had discontinued their triplicate programs prior to the launch. There is no mention of former triplicate states in the Purdue Pharma documents, and we assume they received similar marketing as other nontriplicate states.

Other representative examples: “The impact of the triplicate laws was particularly significant when one realizes that the most common narcotic used by the surgeons and PCP’s in New Jersey [a nontriplicate state] was Percocet/Percodan, whereas in Texas [a triplicate state], this was a product/class of drugs prescribed by most doctors less than five times per year … if at all” (Groups Plus 1995, 24). “Targeting will be a key element to the success of OxyContin … Unfortunately, physicians in triplicate states are going to be harder to convince since they use less CII medications” (Strategic Business Research 1996, 7). “These triplicate state physicians are far less likely to use an oxycodone product…. Only 14% mentioned the use of oxycodone products for moderately severe pain, whereas almost three times this number of the non-triplicate physicians (37%) utilize this class of opioid” (Strategic Business Research 1996, 13).

Purdue Pharma appears to have lobbied for the repeal of triplicate policies. For example, the 1999 budget plan includes a $750,000 line item to fund a “Program to impact the regulatory environment for opioid prescribing in triplicate states” (Purdue Pharma 1999, 68).

The evidence of promotional activities for opioids responding to state-level PDMPs is consistent with findings in Nguyen, Bradford, and Simon (2019) about more recent adoption of mandatory access PDMPs in the 2010s.

For example, “McKinsey recommended doubling down on Purdue Pharma’s strategy of targeting high prescribers for even more sales calls” (Commonwealth of Massachusetts 2019, 212).

We begin in 1983 because the 1981 and 1982 files do not include all deaths. In select states, only half of deaths were included, and they were included twice.

For 1983–1998, we define drug poisonings as deaths involving underlying cause of death ICD-9 codes E850–E858, E950.0–E950.5, E962.0, or E980.0–E980.5 (see Table 2 of https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pdo_guide_to_icd-9-cm_and_icd-10_codes-a.pdf, last accessed November 29, 2018). When we study opioid-related overdoses, we use deaths involving E850.0, E850.1, E850.2, or N965.0 (Green et al. 2017; Alexander, Kiang, and Barbieri 2018). For the 1999–2017 data, we code deaths as drug overdoses using the ICD-10 external cause of injury codes X40–X44, X60–64, X85, or Y10–Y14 (Warner et al. 2011). We use drug identification codes to specify opioid-related overdoses: T40.0–T40.4 and T40.6. Linking opioid overdoses across ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes in this manner is recommended in Table 3 of https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pdo_guide_to_icd-9-cm_and_icd-10_codes-a.pdf. One exception is our use of T40.6. The inclusion of this code does not change our results, which we show in the Online Appendix.

In Online Appendix Figure A2, we explore this coding change by examining the national trend in drug overdose deaths around 1999. Although we observe an increase in 1999, it is comparable to increases in other time periods. The 1999 increase is larger for opioid-related overdose deaths but not uniquely large relative to other annual changes.

The specific type of opioid is not reliably coded before 1999 in a manner that can be linked to 1999–2017 data.

Distribution of controlled substances from online or mail-order pharmacies is included in the ARCOS data but cannot be separately identified. These distributions will be attributed to the location of the supplier, which may add some measurement error (MEPS/Medicaid reports prescriptions by state of residence). This could attenuate our ARCOS estimates because the use of online pharmacies is more likely in the nontriplicate states given higher levels of OxyContin prescribing. However, this bias is likely to be small, because the use of online pharmacies for opioids was limited. When online pharmacies were first introduced in 1999, there was limited internet access (Stergachis 2001) and, over time, state and federal laws effectively banned opioid sales online (GAO 2000).

ARCOS data are available from https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/arcos/retail_drug_summary/ (last accessed November 30, 2018). Archived data are available from https://web.archive.org/web/20030220041015/https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/arcos/retail_drug_summary/.

The public ARCOS data do not report all scheduled substances for each state-quarter, especially for the 1997–2001 time period, which raises concerns about comparability over time. However, oxycodone and hydrocodone—the focus of our study—are reported in all years and states. Moreover, in the figures we do not observe any evidence of unusual year-to-year jumps which would suggest inconsistent reporting for these substances.

We end the sample in 2005 because of the introduction of Medicare Part D. We select on state-years reporting in all four quarters (over 94% of state-years). Although a recent version suppresses data with fewer than 10 prescriptions, we rely on an earlier version of the data that is unsuppressed.

NSDUH defines “misuse” as taking medication that “was not prescribed for you or that you took only for the experience or feeling they caused.”

For more information on these data, see Section II.A of Alpert, Powell, and Pacula (2018).

Demographic information comes from Medicare SEER population data for 1990–2017 and census data for 1983–1989 since SEER only includes population by ethnicity beginning in 1990. The education variables are calculated using the Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Study (Ruggles et al. 2018).

We condensed the preperiod to 5 years (from the full 13 years available) to provide a more meaningful comparison with the postperiods. As can be seen in the event study results, the estimates are not sensitive to different choices for the preperiod.

We use the boottest package in Stata (Roodman et al. 2019) to implement this procedure.