Abstract

Context

Incidentally discovered adrenal adenomas are common. Assessment for possible autonomous cortisol excess (ACS) is warranted for all adrenal adenomas, given the association with increased cardiometabolic disease.

Objective

To evaluate the discriminatory capacity of 3-dimensional volumetry on computed tomography (CT) to identify ACS.

Methods

Two radiologists, blinded to hormonal levels, prospectively analyzed CT images of 149 adult patients with unilateral, incidentally discovered, adrenal adenomas. Diameter and volumetry of the adenoma, volumetry of the contralateral adrenal gland, and the adenoma volume-to-contralateral gland volume (AV/CV) ratio were measured. ACS was defined as cortisol ≥ 1.8 mcg/dL after 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test (DST) and a morning ACTH ≤ 15. pg/mL.

Results

We observed that ACS was diagnosed in 35 (23.4%) patients. Cortisol post-DST was positively correlated with adenoma diameter and volume, and inversely correlated with contralateral adrenal gland volume. Cortisol post-DST was positively correlated with the AV/CV ratio (r = 0.46, P < 0.001) and ACTH was inversely correlated (r = −0.28, P < 0.001). The AV/CV ratio displayed the highest odds ratio (1.40; 95% CI, 1.18-1.65) and area under curve (0.91; 95% CI, 0.86-0.96) for predicting ACS. An AV/CV ratio ≥ 1 (48% of the cohort) had a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 70% to identify ACS.

Conclusion

CT volumetry of adrenal adenomas and contralateral adrenal glands has a high discriminatory capacity to identify ACS. The combination of this simple and low-cost radiological phenotyping can supplement biochemical testing to substantially improve the identification of ACS.

Keywords: hypercortisolism, adrenal incidentaloma, adrenal volumetry, adrenocorticotropic hormone, Cushing syndrome, adrenal cortex neoplasm

Adrenal incidentalomas are frequently observed in clinical practice, ranging from 1% to 10% prevalence among < 30-year-old and > 70-year-old patients, respectively (1-4). Although the majority of incidental adrenal adenomas have been traditionally categorized as nonfunctional, an increasing proportion are considered “hormonally active,” mainly due to hypercortisolism (5-8). The spectrum of autonomous adrenal hypercortisolism (ACS) has expanded, ranging from rare overt Cushing’s syndrome with severe cardiometabolic risk and mortality, to much more frequent mild adrenal hypersecreting tumors. Recent guidelines referred to ACS as either being “mild” or “possible” when post-dexamethasone cortisol values are from 1.8 to 5.0 mcg/dL, and “definite” when post-dexamethasone cortisol values were greater than 5.0 mcg/dL (6). Some form of ACS has been described in up to 25% of incidental adenomas, and this cortisol excess is associated with adverse cardiometabolic consequences and related mortality (1, 2, 9-11). Unfortunately, there is a lack of clinical awareness of ACS, especially by non-endocrinologists; the majority of incidentally discovered adrenal masses never undergo the appropriate assessments to identify ACS (12).

Although computed tomography (CT) can provide discriminatory data to differentiate benign from malignant adrenal tumors; to date, studies that use radiologic phenotyping to diagnose or exclude ACS are scarce (13-15). Since adrenal incidentalomas are initially identified on imaging, the identification of specific radiologic features that predict a high or low probability of ACS would be of clinical value.

From a pathophysiological perspective, unilateral adrenal hypercortisolism should exhibit an asymmetric radiographic pattern: a unilateral adrenal adenoma overproducing cortisol should induce relative suppression of ACTH, consequent atrophy of the contralateral zona fasciculata, and hence a diminished volume of the contralateral adrenal gland. In this regard, asymmetric adrenal volumetry could be a radiographic surrogate for, or complementary metric to, hormonal testing.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the discriminatory capacity of CT-derived 3-dimensional (3D) adrenal volumetry as a radiological tool to predict ACS among patients with unilateral incidentally discovered adrenal adenomas.

Methods

Subjects

Patients consecutively treated and followed prospectively at our institution between August 2016 and May 2020, with a diagnosis of adrenal incidentaloma were selected. Adenomas were defined by radiological assessment, as described below.

Patients that met any of the following criteria were initially excluded: (i) age younger than 18 years, (ii) tumor size < 1 cm; (iii) known metastatic disease; (iv) use of oral/intramuscular/intravenous glucocorticoids in the last 3 months or inhaled/transdermal glucocorticoids in the last month; and (v) clinically overt Cushing syndrome prior to adrenal radiological assessment. This study was approved by the ethics committee of our institution.

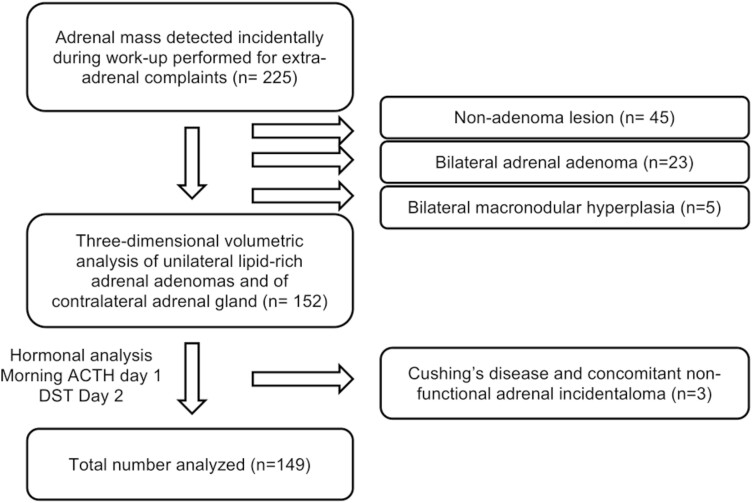

Radiologic Assessment

Initially, 225 subjects underwent an abdominal CT, either nonenhanced or with iodinated intravenous contrast, in the setting of clinical conditions unrelated to adrenal disorders. The adrenal lesion was confirmed as an adenoma using attenuation criteria <10 Hounsfield units (HU) in unenhanced images or strict washout criteria when delayed contrast images were available (relative washout > 40% and/or absolute washout > 60%). When magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was available, signal dropout on opposed-phase images was considered diagnostic of an adenoma. When these methods were not available or diagnosis was unclear, confirmatory CT using a standard adrenal protocol was performed (noncontrast imaging, 70-second post-contrast venous phase imaging, and 10- to 15-minute delayed post-contrast phase), using known density and washout criteria for adenoma diagnosis (16-19). Using these definitions, 45 subjects were excluded for having nonadenomatous adrenal masses, 5 were excluded for having bilateral macronodular hyperplasia, and 23 subjects were excluded because they had bilateral adrenal adenomas (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Algorithm of included and excluded participants.

Among the included 152 subjects, 3D volumetric analysis of the unilateral adrenal adenoma and of the contralateral adrenal gland was performed. These volumetric analyses were performed by 2 independent radiologists who were blinded to laboratory test results. Osirix viewer software was used to examine 1.5- to 2.5-mm thin-section axial CT images as well as sagittal and coronal reconstructions to perform a manual segmentation, highlighting and separating the adenoma and adrenal gland from neighboring structures. Of note, this software, accessing to all available raw data, can address volumetry even in a nonenhanced CT urography or chest CT. In cases with more than one CT available, the one closest by date to the blood analysis was chosen to perform the evaluation. Reproducibility of the volumetric analysis obtained by each reviewer was evaluated using a Bland-Altman graphic method.

Endocrine Assessment

The Adrenal Program in our institution has implemented a systematic hormonal assessment for all adrenal incidentalomas, as previously described (20, 21). On the first day, blood samples were obtained between 08:00 and 09:00 hours, after an 8-hour overnight fast, for measurement of morning ACTH. We also performed a 1-mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test (DST) by administering 1 mg of dexamethasone at 23:00, with measurement of cortisol the following morning (between 08:00 and 09:00 hours) (Fig. 1).

In order to maximize sensitivity and avoid potential confounders in the assessment of ACS, the samples were obtained after at least 2 months without using estrogen-containing oral contraceptives or postmenopausal estrogen-containing replacement therapy. All blood samples were analyzed in the Central Laboratory of our institution, which meets international standards and is certified by the College of American Pathologist’s Laboratory Accreditation Program. ACS was defined as a morning ACTH < 15 pg/mL and cortisol following DST of >1.8 mcg/dL as recommended (22-24). All subjects with DST ≥ 1.8 and ACTH ≥ 15 were evaluated with a pituitary MRI. Three patients were ultimately diagnosed with Cushing’s disease and concomitant nonfunctional adrenal incidentaloma, and were excluded from further analysis, reducing the total sample size to 149 patients (Fig. 1).

Hormonal Assays

Serum cortisol was measured with an electrochemiluminescence immunometric assay (Cobas; Roche), with intra-assay coefficient of variation < 5%. ACTH was measured with a chemiluminescent immunoenzymatic solid-phase assay (Immulite2000 XPi; Siemens), with intra-assay coefficient of variation < 10%.

Comorbidities

Hypertension was defined as previous diagnosis or use of antihypertensive medication. Dysglycemia (prediabetes or diabetes) was defined by documented diagnosis and/or a hemoglobin A1c > 5.7% or a serum glucose > 140 mg/dL after a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (25).

Dyslipidemia was defined by LDL-cholesterol > 130 mg/dL or triglycerides > 150 mg/dL or HDL < 40 mg/dL in males or < 50 mg/dL in females (26).

Coronary disease was defined as previous diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction, stable angina, or history of coronary arterial revascularization (27).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean and SD. Categorical comparisons were performed with Chi-square test and continuous variables were compared using Student t test, with P value of < 0.05 considered significant. Normality was assessed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Correlations between normally continuous variables were evaluated using Pearson’s test. When variables were not normally distributed, a bootstrapping analysis with resampling in 1000 iterations was applied to deal with outliers and nonnormality issues and to confirm the internal validation of the analysis. Further, a logistic regression model was performed with unadjusted and adjusted models (laterality, age, and sex) assessing odds ratios for the association of ACS with radiologic variables. Goodness of fit was determined by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. Finally, a predictive model (crude and adjusted) was developed using C-statistics, with the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve determined by 1-Specificity on the x-axis against sensitivity on the y-axis for all possible cutoff points. Sensitivity was defined as the ability of the radiologic test to correctly identify patients with ACS (true positives). Specificity was defined as the ability of the radiologic test to identify patients without ACS (true negatives). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (v.25: SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

The demographic data and comorbidities of the final cohort are presented in Table 1. Of the total cohort, 113 patients (76%) were female, with a mean age of 58 ± 11.4 years. We observed that 54% of adenomas were left-sided, with a mean diameter and volume of 20.2 ± 8.1 cm and 4.6 ± 6.6 cm3, respectively, while mean contralateral adrenal volume was 2.63 ± 1.1 cm3.

Table 1.

Clinical, radiological, and biochemical characteristics of included patients

| Incidental adrenal adenomas (n = 149) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years (range) | 57.8 (26 – 90) |

| Women, n (%) | 113 (76) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 28.9 (4.2) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 88 (59) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 82 (55) |

| Dysglycemia, n (%) | 73 (49) |

| Coronary disease, n (%) | 5 (3) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 8 (5) |

| Left side, n (%) | 81 (54) |

| Adenoma diameter, mm (range) | 20.2 (10 – 49) |

| Adenoma volume, cm3 (range) | 4.6 (0.9 – 49.8) |

| Contralateral adrenal volume, cm3 (range) | 2.64 (0.5 – 6.4) |

| Adenoma volume/Contralateral adrenal volume ratio (range) | 2.73 (0.05 – 59.5) |

| DST 1 mg, μg/dL, mean (SD) | 1.86 (2.9) |

| ACTH, pg/mL, mean (SD) | 15.1 (8.4) |

| ACS, n (%) | 35 (23.4) |

Values are expressed as n, total number (%), or mean (SD), and range (min-max) when appropriate.

Abbreviations: ACS, possible autonomous cortisol secretion; DST, 1 mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test.

The Bland-Altman analysis showed acceptable inter-reader measurement agreement and only moderate dispersion of the results in both adenoma diameter (mean difference 0.29 ± 1.49 mm) and contralateral adrenal volume (mean difference 0.26 ± 1.49 cm3). Mean DST was 1.86 ± 2.9 μg/dL and ACTH was 15.1 ± 8.4 pg/mL.

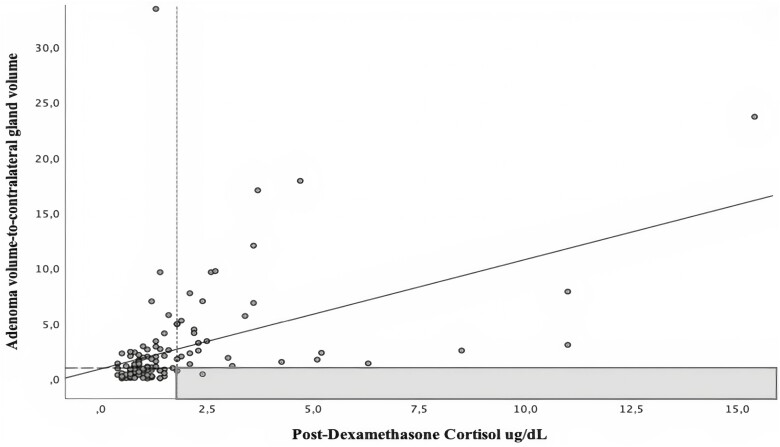

The post-dexamethasone cortisol was positively correlated with both the diameter and volume of the adenoma, and inversely correlated with the contralateral adrenal gland volume. In contrast, ACTH showed the opposite behavior, exhibiting a negative correlation with both diameter and volume of adenoma, and a positive correlation with the contralateral adrenal gland volume (Table 2). No association was observed between pre-contrast or post-contrast density (in HU) and DST or ACTH. Since both higher volume of the adenoma and lower contralateral adrenal gland volume were associated with higher DST and lower ACTH, we developed a novel ratio that combined the aforementioned 2 radiologic features, defined as the adenoma volume-to-contralateral adrenal gland volume (AV/CV) ratio. The cortisol level post-DST showed the highest correlation with the AV/CV ratio (r = +0.46, P < 0.001, Fig. 2), while ACTH showed an inverse correlation (r = −0.28, P < 0.001) (Table 2). Since only age (and not sex or body mass index [BMI]) was inversely associated with DST (r = −0.17, P = 0.30) we performed partial correlation analyses and observed that the positive association between DST and AV/CV ratio remained unchanged after adjusting for age (partial r = 0.44, P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Correlations of continuous variables and possible autonomous cortisol secretion (ACS) measurements

| Patients (n = 149) | DST ug/dL | ACTH pg/mL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson (r) | Pvalue | Pearson (r) | Pvalue | |

| Age, years | -0.167 | 0.03 | +0.12 | 0.14 |

| Adenoma volume, cm3 | +0.43 | 0.001 | -0.32 | <0.001 |

| Adenoma diameter, cm | +0.42 | 0.001 | -0.36 | <0.001 |

| Adenoma density, HU | +0.15 | 0.13 | +0.08 | 0.45 |

| Contralateral adrenal gland volume, cm3 | -0.29 | 0.001 | +0.30 | <0.001 |

| Adenoma volume/ Contralateral adrenal volume (AV/CV) ratio | +0.46 | 0.001 | -0.28 | <0.001 |

r = Pearson’s coefficient. Significant correlations are in bold.

Abbreviations: ACS, possible autonomous cortisol excess; DST, 1 mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test; HU, Hounsfield Units.

Figure 2.

Correlation of post-dexamethasone cortisol values with proposed volumetric ratio. Scatterplot showing Pearson correlation of post-dexamethasone cortisol with adenoma volume/contralateral gland volume ratio. Vertical dotted line (x-axis) represents post-dexamethasone cortisol of 1.8 ug/dL (threshold for possible autonomous cortisol secretion). Horizontal dashed line (y-axis) represents adenoma volume/contralateral gland volume ratio equal to 1. The gray colored area represents the most sensitive threshold to exclude (rule-out) autonomous cortisol secretion.

Of the 149 studied patients, 23.4% (35/149) were diagnosed with ACS. There were no differences in age, sex, BMI, or other comorbidities between patients with ACS and those without ACS (Table 3). In contrast, radiographic parameters were substantially different between those with and without ACS. Compared to patients without ACS, those with ACS had significantly higher adenoma diameter (28.6 ± 8.1 vs 17.6 ± 6.2 mm; P< 0.001), higher adenoma volume (10.7 ± 9.7 vs 2.7 ± 3.9 cm3; P < 0.001), as well as lower contralateral adrenal gland volume (1.9 ± 0.6 vs 2.9 ± 1.1 cm3; P< 0.001). Further, patients with ACS had significantly higher AV/CV ratio than those without ACS (7.3 ± 10.6 vs 1.4 ± 3.3; P< 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Anthropometric and radiologic parameters categorized by ACS status

| ACS (n = 35) | Nonfunctional adenoma (n = 114) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (SD) | 60.1 (12.0) | 57.3 (10.5) | 0.16 |

| Women, % | 82% | 76% | 0.23 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 30.6 (4.4) | 28.3 (4.0) | 0.16 |

| Hypertension, % | 61 | 53 | 0.40 |

| Dysglycemia, % | 28 | 26 | 0.87 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 60 | 53 | 0.37 |

| Adenoma diameter, mm (SD) | 28.6 (8.1) | 17.6 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Adenoma volume, cm3 (SD) | 10.7 (9.7) | 2.8 (3.9) | <0.001 |

| Contralateral adrenal gland volume, cm3 (SD) | 1.9 (0.6) | 2.9 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Adenoma volume/ Contralateral adrenal volume ratio (SD) | 7.3 (10.6) | 1.3 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| DST (ug/dL, mean, SD) | 4.7 (4.9) | 0.9 (0.3) | <0.001 |

| ACTH, pg/mL, mean (SD) | 9.5 (5.7) | 17.2 (8.3) | <0.001 |

Values are expressed as n, total number (%), or mean (SD) where appropriate.

Abbreviations: ACS, possible autonomous cortisol secretion; DST, 1 mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test.

We evaluated radiologic parameters to predict ACS in crude and adjusted logistic regression analysis. Predicted regression values were used to evaluate ROC curves and estimate sensitivity and specificity of the models. Of the 4 significant radiologic parameters predicting ACS status, the AV/CV ratio displayed both the highest odds ratio (OR 1.40; 95% CI, 1.18-1.65) and area under ROC curve (AUC) (0.91; 95% CI, 0.86-0.96) for ACS diagnosis, thus it was chosen for further adjusted analyses.

An AV/CV ratio of ≥ 1 (48% of the cohort) identified ACS with a sensitivity of 97% (thus, with a very low false negative rate) and specificity of 70%. On the other hand, an AV/CV ratio of ≥ 3 (19% of the cohort) identified ACS with a sensitivity of 62% but a specificity of 95% (thus, with a very low false positive rate). To evaluate the robustness of these findings, we performed adjusted models with potential confounders, including laterality. We present AUC, sensitivity, and specificity for different models in Table 4.

Table 4.

Area under ROC curves and estimate sensitivity and specificity of unadjusted and adjusted predictive models for possible autonomous cortisol secretion (ACS)

| Unadjusted | Adjusted by laterality | Adjusted by laterality, age, and sex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Odd ratio (95% CI) | 1.40 (1.18-1.65) | 1.40 (1.18-1.66) | 1.41 (1.19-1.68) |

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.91 (0.86-0.96) | 0.89 (0.84-0.95) | 0.88 (0.81-0.95) |

| Sensitivity and specificity of AV/CV ratio ≥ 1 |

S = 97 E = 70 |

S = 94 E = 64 |

S = 91 E = 72 |

| Sensitivity and specificity of AV/CV ratio ≥ 3 |

S = 62 E = 95 |

S = 62 E = 93 |

S = 59 E = 93 |

Abbreviations: ACS, possible autonomous cortisol secretion; AUC, area under the curve; AV/CV, adrenal volume/contralateral adrenal volume; E, specificity; S, sensitivity.

Sensitivity Analyses

We assessed ROC curves of radiological measurements for a stricter hormonal threshold, using DST > 5 µg/dL, defined by current guidelines as definite autonomous cortisol secretion. Of the 149 studied patients, we identified only 9 (6%) that fulfilled definite ACS criteria, with a range from 5.2 to 25.9 µg/dL. Consistent with our findings for possible ACS (DST ≥ 1.8 µg/dL), AV/CV ratio also displayed the highest area under ROC curve for definite ACS diagnosis (AUC 0.85), performing better than adenoma diameter, adenoma volume, or contralateral adrenal gland volume (Table 5).

Table 5.

Sensitivity analyses of radiologic measurements

| AUC DST > 1.8 and ACTH < 15 (possible ACS) |

AUC DST > 5 (definite ACS) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Adenoma diameter, mm | 0.85 | 0.81 |

| Adenoma volume, cm 3 | 0.86 | 0.83 |

| Contralateral adrenal volume, cm 3 | 0.77 | 0.78 |

| AV/CV ratio | 0.91 | 0.85 |

Abbreviations: ACS, autonomous cortisol secretion; AV/CV, adrenal volume/contralateral adrenal volume; DST, 1 mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test.

Discussion

In the present study we evaluated the discriminatory capacity of 3D CT volumetry to predict mild autonomous cortisol excess in incidentally discovered unilateral adrenal adenomas. Our findings show that CT volumetry can accurately assess that higher adenoma volume, in combination with lower contralateral adrenal gland volume, is a strong predictor of higher post-DST cortisol levels and lower ACTH levels. The AV/CV ratio was the best predictor for assessing the presence of ACS, with a ratio ≥1 showing an impressive sensitivity of 97%. Given the very low false negative rate, an AV/CV ratio lower than 1 could be used in clinical practice to exclude ACS. Collectively, these results highlight a novel radiographic tool with high capacity to evaluate the risk for ACS, which can be used instead of, or in combination with, standard hormonal evaluations.

Mild or possible ACS is a frequent condition, described in up to one-third of incidental adrenal adenomas and associated with important morbidity and mortality, thereby highlighting the need for its recognition as a clinical risk factor (28). Current clinical practice guideline recommendations suggest a 2-step process that results in an inefficient evaluation of ACS (6). First, radiographic detection of an incidental adrenal adenoma needs to be recognized by clinicians as an important finding that may warrant referral for appropriate evaluation; however, the majority of incidental adrenal adenomas are rarely referred for further follow-up (12). The second step, biochemical assessment via the DST, only occurs in a small minority of cases (12). Our findings suggest that a 1-step process in which a CT scan can both identify an incidental adenoma and also provide a prediction of the potential for hormone excess could simplify and enhance clinical care.

Our findings provide a novel method, based on pathophysiological expectations, to better characterize ACS in incidental adrenal adenomas. Unilateral adrenal hypercortisolism is characterized by impaired ACTH secretion, resulting in atrophy of the contralateral adrenal gland. Due to improved CT technology, this pathophysiological phenomenon has become the subject of multiple studies during the last decade, aiming to improve the diagnostic accuracy of ACS (29-31). Mosconi et al demonstrated that both diameter and post-enhancement attenuation of incidental adenomas were positively associated with mild cortisol secretion (cortisol post-DST > 1.8 μg/dL); however, this study did not assess any radiologic features of the contralateral gland (32). Following these findings, the study of Sugiura et al in patients with a post-DST cortisol > 1.8 μg/dL who underwent adrenalectomy, showed that contralateral adrenal width was the only radiologic predictor of prolonged postoperative glucocorticoid replacement, which could be considered a surrogate marker of the amount of chronic exposure to endogenous cortisol and low ACTH (33). Kong et al recently found a negative linear correlation between limb width of the contralateral adrenal gland and cortisol levels after DST in patients with unilateral adrenal adenomas. They also found that the diameter of the contralateral adrenal limb had better diagnostic performance to differentiate ACS from nonfunctional adenomas than the volume of either the contralateral gland or adenoma (34).

Our study extends these prior findings in that the aforementioned studies evaluated the diagnostic performance of single radiologic parameters, whereas we show that the combination of radiographic findings enhances accuracy for detecting ACS (35). In our study, the AV/CV ratio demonstrated the best discriminative capacity to exclude patients with ACS from those with nonfunctional adenomas. On the other hand, an AV/CV ratio ≥3 displayed high specificity for ACS, at the expense of a lower sensitivity. This is explained because patients with ACS had an AV/CV ratio 5 times higher than those with nonfunctional adenomas, comparable to the difference between the DST results between both groups. Of note, clinical variables such as comorbidities, age, and BMI were not particularly useful in predicting ACS. These findings highlight that 3D CT volumetry to assess the AV/CV ratio could be a valuable adjunct to clinical care, enabling clinicians to readily identify adenomas that warrant further testing, distinguishing them from those that do not require further hormonal screening.

Our study has several strengths. Logistic regression and AUC results are clinically significant, and our findings persisted after adjusting for laterality, which is important because normally the mean volume of the left adrenal gland is significantly greater (10%-15%) than the mean volume of the right gland. Moreover, Hao et al found that left-sided adenomas were 3 times more frequently detected than right-sided adenomas, especially in tumors < 3.0 cm, attributable to radiologic detection bias due to better visualization of the left adrenal gland on abdominal cross-sectional imaging (36). This phenomenon was confirmed in our study, with 54% of adenomas being left-sided. Considering the normal asymmetry of left and right adrenal glands, it would be expected that future software would be able to adjust volume of adenomas and contralateral gland according to tumor location. Imaging protocols used for the diagnosis of adenoma and the assessment of nodule volumetry and contralateral gland in this study, reflect typical practice worldwide. As such, the volumetric analysis results are expected to have good applicability in the real-life setting.

Some limitations of the present exploratory study include a relatively small sample size and the lack of follow-up in order to predict cardiometabolic outcomes. However, the aim of our study was to evaluate the discriminative capacity of radiologic features to predict biochemical hypercortisolism, not incidence of comorbidities. Future studies are required to confirm if adrenal asymmetry can add benefit in the management of patients with incidental adrenal adenomas, including the use of relaxed vs strict follow-up and, eventually, as a complementary tool for surgical indication. Our study had a preponderance of women with unilateral adenomas. Several studies have shown that a larger proportion of women are observed in radiological studies of adrenal incidentalomas but not in autopsy studies (37-39). This discordance has been explained as being due to the fact that women may undergo abdominal imaging more frequently than men. In our study, despite a higher prevalence of women, we observed no sex differences in diameter and/or volume of adenoma or cortisol post-DST. Finally, our findings regarding AV/CV ratio only apply to unilateral adenomas, although the diameter and volume of the adenoma were good predictors of ACS and should be investigated in cases of bilateral adenomas. Future studies regarding the discriminative capacity of adrenal volumetry for prediction of functional status in incidental adenomas in different cohorts are needed to validate this novel radiologic tool.

Conclusion

CT volumetry of adrenal adenomas and contralateral adrenal gland is a simple and low-cost method with excellent predictive capacity to identify ACS. An AV/CV ratio ≥ 1, with high sensitivity and a very low false negative rate, could assist in the clinical decision to exclude incidental adenomas unlikely to exhibit hypercortisolism. The inclusion of this radiographic phenotyping could simplify the assessments and referrals for incidental adrenal adenomas and improve clinical care for this overlooked entity.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ACS

autonomous cortisol secretion (adrenal hypercortisolism)

- ACTH

adrenocorticotropic hormone

- AUC

area under the ROC curve

- AV/CV

adenoma volume-to-contralateral adrenal gland volume

- BMI

body mass index

- CT

computed tomography

- DST

dexamethasone suppression test

- HU

Hounsfield units

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- ROC

receiver-operating characteristic

Contributor Information

Roberto Olmos, Department of Endocrinology, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, 8330077, Chile; Program for Adrenal Disorders, CETREN UC, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, 8330077, Chile.

Nicolás Mertens, Department of Radiology, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, 8330077, Chile.

Anand Vaidya, Center for Adrenal Disorders, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Thomas Uslar, Department of Endocrinology, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, 8330077, Chile; Program for Adrenal Disorders, CETREN UC, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, 8330077, Chile.

Paula Fernandez, Program for Adrenal Disorders, CETREN UC, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, 8330077, Chile.

Francisco J Guarda, Department of Endocrinology, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, 8330077, Chile.

Álvaro Zúñiga, Department of Urology, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago 8330077, Chile.

Ignacio San Francisco, Department of Urology, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago 8330077, Chile.

Alvaro Huete, Department of Radiology, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, 8330077, Chile.

René Baudrand, Department of Endocrinology, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, 8330077, Chile; Program for Adrenal Disorders, CETREN UC, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, 8330077, Chile.

Financial Support

We acknowledge our funding sources: Fondecyt grant #1190419 (R.B., R.O., A.H.); Fondecyt grant #1212006 and 1211879 (R.B.); R01 DK115392 (A.V.), R01 HL153004 (A.V.), R01 DK16618 (A.V.), ANID ANILLO ACT210039 (R.B.).

Disclosures

A.V. reports consulting fees unrelated to the contents of this work from Corcept Therapeutics, Mineralys, and HRA Pharma.

Data Availability

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Sherlock M, Scarsbrook A, Abbas A, et al. Adrenal incidentaloma. Endocr Rev. 2020;41(6):775-820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bancos I, Prete A. Approach to the patient with adrenal incidentaloma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(11):3331-3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Young WFJ. The incidentally discovered adrenal mass. n-clinical-practice. N Engl J Med. 2009;356(6):601-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vassiliadi DA, Tsagarakis S. Endocrine incidentalomas--challenges imposed by incidentally discovered lesions. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7(11):668-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cambos S, Tabarin A. Management of adrenal incidentalomas: Working through uncertainty. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;34(3):101427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fassnacht M, Arlt W, Bancos I, et al. Management of adrenal incidentalomas: European Society of Endocrinology clinical practice guideline in collaboration with the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;175(2):G11-G34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lopez D, Luque-Fernandez MA, Steele A, Adler GK, Turchin A, Vaidya A. “Nonfunctional” adrenal tumors and the risk for incident diabetes and cardiovascular outcomes: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(8):533-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Delivanis DA, Athimulam S, Bancos I. Modern management of mild autonomous cortisol secretion. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;106(6):1209-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Debono M, Bradburn M, Bull M, Harrison B, Ross RJ, Newell-Price J. Cortisol as a marker for increased mortality in patients with incidental adrenocortical adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;12:4462-4470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Di Dalmazi G, Vicennati V, Rinaldi E, et al. Progressively increased patterns of subclinical cortisol hypersecretion in adrenal incidentalomas differently predict major metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes: a large cross-sectional study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;166(4):669-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yozamp N, Vaidya A. Assessment of mild autonomous cortisol secretion among incidentally discovered adrenal masses. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;35(1):101491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kirsch MJ, Hsu KT, Lee MH, et al. Hormonal evaluation of incidental adrenal masses: the exception, not the rule. World J Surg. 2020;44(11):3778-3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dinnes J, Bancos I, Ferrante di Ruffano L, et al. Management of endocrine disease: imaging for the diagnosis of malignancy in incidentally discovered adrenal masses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;175(2):51-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hong AR, Kim JH, Park KS, et al. Optimal follow-up strategies for adrenal incidentalomas: reappraisal of the 2016 ESE-ENSAT guidelines in real clinical practice. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;177(6):475-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nandra G, Duxbury O, Patel P, Patel JH, Patel N, Vlahos I. Technical and interpretive pitfalls in adrenal imaging. Radiographics. 2020;40(4):1041-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marty M, Gaye D, Perez P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography to identify adenomas among adrenal incidentalomas in an endocrinological population. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;178(5):439-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Malayeri AA, Zaheer A, Fishman EK, Macura KJ. Adrenal masses: contemporary imaging characterization. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2013;37(4):528-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Humbert AL, Lecoanet G, Moog S, et al. The computed tomography adrenal wash-out analysis properly classifies cortisol secreting adrenocortical adenomas. Endocrine. 2018;59(3):529-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schieda N, Siegelman ES. Update on CT and MRI of adrenal nodules. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208(6):1206-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Canu L, Van Hemert JAW, Kerstens MN, et al. CT Characteristics of pheochromocytoma: relevance for the evaluation of adrenal incidentaloma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(2):312-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Olmos R, Gutierrez J, Guarda F, et al. ¿Como optimizar el diagnóstico funcional de los incidentalomas suprrarenales? Importancia de un estudio protocolizado. Rev Chil Endo Diab. 2018;11(3):108-113. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bancos I, Alahdab F, Crowley RK, et al. Therapy of endocrine disease: improvement of cardiovascular risk factors after adrenalectomy in patients with adrenal tumors and subclinical Cushing’s syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;175(6):283-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mauclère-Denost S, Duron-Martinaud S, Nunes M, et al. Surgical excision of subclinical cortisol secreting incidentalomas: impact on blood pressure, BMI and glucose metabolism. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2009;70(4):211-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mitchell IC, Auchus RJ, Juneja K, et al. “Subclinical Cushing’s syndrome” is not subclinical: improvement after adrenalectomy in 9 patients. Surgery. 2007;142(6):900-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adler A, Bennett P, Colagiuri Chair S, et al. Reprint of: classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;108972. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.108972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018;139(25):e1082-e1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(10):177-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zavatta G, Di Dalmazi G. Recent advances on subclinical hypercortisolism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2018;47(2):375-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Amsterdam JD, Marinelli DL, Arger P, Winokur A. Assessment of adrenal gland volume by computed tomography in depressed patients and healthy volunteers: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 1987;21(3):189-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carsin-Vu A, Oubaya N, Mule S, et al. MDCT linear and volumetric analysis of adrenal glands: normative data and multiparametric assessment. Eur Radiol. 2016;26(8):2494-2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Degenhart C, Schneller J, Osswald A, et al. Volumetric and densitometric evaluation of the adrenal glands in patients with primary aldosteronism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2017;86(3):325-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mosconi C, Vicennati V, Papadopoulos D, et al. Can imaging predict subclinical cortisol secretion in patients with adrenal adenomas? A CT predictive score. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;209(1):122-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sugiura M, Imamura Y, Kawamura K, et al. Contralateral adrenal width predicts the duration of prolonged post-surgical steroid replacement for subclinical Cushing syndrome. Int J Urol. 2018;25(6):583-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kong SH, Kim JH, Shin CS. Contralateral adrenal thinning as a distinctive feature of mild autonomous cortisol excess of the adrenal tumors. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;183(3):325-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Park SY, Oh YT, Jung DC, Rhee Y. Prediction of adrenal adenomas with hypercortisolism by using adrenal computed tomography: emphasis on contralateral adrenal thinning. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2015;39(5):741-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hao M, Lopez D, Luque-Fernandez MA, et al. The lateralizing asymmetry of adrenal adenomas. J Endocr Soc. 2018;2(4):374-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Alesina PF, Walz MK. Adrenal tumors: are gender aspects relevant? Visc Med. 2020;36(1):15-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ye YL, Yuan XX, Chen MK, Dai YP, Qin ZK, Zheng FF. Management of adrenal incidentaloma: the role of adrenalectomy may be underestimated. BMC Surg. 2016;16(1):41-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mantero F, Terzolo M, Arnaldi G, et al. A survey on adrenal incidentaloma in Italy. Study group on adrenal tumors of the Italian Society of Endocrinology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(2):637-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.