Abstract

Background High neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is associated with poor survival in lung cancer. This study evaluates whether NLR is associated with baseline brain metastasis in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods Medical records of stage IV NSCLC patients treated at King Hussein Cancer Center (Amman-Jordan) between 2006 and 2016 were reviewed. Patients with baseline brain imaging and complete blood count (CBC) were included. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to identify the optimal cutoff value for the association between NLR and baseline brain metastasis. Association between age, gender, location of the primary tumor, histology, and NLR was assessed using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses.

Results A total of 722 stage IV NSCLC patients who had baseline brain imaging were included. Median age was 59 years. Baseline brain metastasis was present in 280 patients (39.3%). Nine patients had inconclusive findings about brain metastasis. The ROC curve value of 4.3 was the best fitting cutoff value for NLR association with baseline brain metastasis. NLR ≥ 4.3 was present in 340 patients (48%). The multivariate analyses showed that high baseline NLR (≥ 4.3) was significantly associated with higher odds of baseline brain metastasis (odds ratio [OR]: 1.6, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.2–2.2; p = 0.0042). Adenocarcinoma histology was also associated with baseline brain metastasis (OR: 0.4, 95% CI: 0.25–0.6; p = 0.001).

Conclusion High NLR is associated with baseline brain metastasis in advanced-stage NSCLC. In the era of immunotherapy and targeted therapies, whether high NLR predicts response of brain metastasis to treatment is unknown.

Keywords: NSCLC, neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio, brain metastasis, stage IV

Introduction

Metastatic brain tumor is the most common intracranial cancer in adults. Lung cancer is one of the most frequent solid tumors to metastasize to the brain. 1 Approximately one-third of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients develop brain metastasis throughout their disease course. 2 3 Despite all recent advances in the management of brain metastasis, the prognosis remains grim. 4

Although inflammation has been linked to the carcinogenesis process, metastasis and survival outcomes in cancer, 5 6 a definitive relationship between inflammation and brain metastasis is lacking. Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR), absolute neutrophil count (ANC), and absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) were found to have a negative impact on the survival outcomes in various tumors including NSCLC. 7 8 9 10 11 One study showed that high NLR is an independent predictive factor of baseline presence and subsequent development of brain metastasis in stage IV NSCLC. 12 However, that study included only 260 patients and the results were likely limited by the patient population comprised of only Korean lung cancer patients historically known to have higher rates of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations.

Various explanations have been postulated to describe the relationship between inflammation and metastasis. High neutrophil count resulting in high NLR is thought to promote metastasis via releasing certain growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor and other proteases. 13 Alternatively, the lymphocytes have an essential role in eliminating tumor cells by inducing cytotoxic cell death and inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and migration, which may explain the association of low ALC with poor outcomes in cancer. 14 15 Another potential explanation might include the relationship between high neutrophils and the myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which was shown to suppress the activity of T cells in lung cancer. 16

In this retrospective study, we aim to further identify the relationship between inflammatory indices, such as NLR, and baseline brain metastasis in stage IV NSCLC. This association could potentially have significant implications on management of NSCLC. Do stage IV NSCLC patients with high NLR need more frequent surveillance brain imaging? Do they benefit from prophylactic cranial irradiation? Do they respond better to brain radiation? And importantly, are tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and immunotherapies more effective in treating brain metastasis when NLR is high?

Methods

This is a retrospective chart review study approved by the Institutional Review Board office at King Hussein Cancer Center in 2017. The study included 722 patients with stage IV NSCLC who had baseline brain imaging. The clinical data including age, gender, histology, the location of primary tumor, and presence of baseline brain metastasis were collected and summarized in Table 1 . Patients were excluded if they had no baseline brain imaging or if they were on steroids before obtaining baseline complete blood count (CBC). Using steroids was expected to confound the results of the study as it is known to cause leukocytosis 17 and especially neutrophilia. 18 The reports of magnetic resonance imaging and/or computed tomography reviewed to detect brain metastasis.

Table 1. Characteristic of stage IV non-small cell lung cancer patients.

| Patients features | No. of patients (%) n = 722 |

|---|---|

| Age > 59 | 342 (47.4) |

| Age ≤ 59 | 380 (52.6) |

| Male | 568 (78.7) |

| Female | 154 (21.3 |

| Location | |

| Upper | 323 (44.7) |

| Middle | 24 (3.3) |

| Lower | 183 (25.3) |

| Others | 192 (26.6) |

| Histology | |

| Adenocarcinoma others | 533 (73.8) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 151 (20.9) |

| Others | 38 (5.3) |

| Baseline brain metastases | |

| Yes | 280 (39.3) |

| No | 433 (60.7) |

| Inconclusive | 9 (1) |

| Baseline liver metastases | |

| Yes | 325 (45) |

| No | 397 (55) |

| Baseline bone metastases | |

| Yes | 245 (34) |

| No | 477 (66) |

CBCs with differential white cell count were collected before initiation of any cancer-specific treatment (systemic treatment or radiation). The pretreatment baseline NLR, monocyte–lymphocyte ratio (MLR), and platelet–lymphocyte ratio (PLR) were calculated using the following formulas: NLR = ANC/ALC, MLR= absolute monocyte count (AMC)/ALC, and PLR = platelet count/ALC.

The ROC curve was used to determine the optimal cutoff value for NLR association with baseline brain metastasis, matching the most extreme joint sensitivity and specificity. Associations between NLR, age, gender, histological subtype, and location of the primary tumor with the presence of baseline brain metastasis were examined. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to test the association between the various variables and baseline brain metastasis.

Our analysis proceeded in stepwise approach. In the first phase, we examined the association between baseline NLR and brain metastasis. In the second phase, we examined the association between other inflammatory indices including ANC, ALC, AMC, MLR, and PLR and baseline brain metastasis. In the third phase, we examined the association between baseline brain metastasis and clinical variables that included age, gender, location of the primary tumor, and histological subtype. In the last phase, we performed a multivariate analysis that included the collected variables (age, gender, location of the primary tumor, and histologic subtype) and NLR as a continuous variable, to clarify any relationship with baseline brain metastasis.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical data were reported as counts and percentages, whereas continuous data were reported as mean ± standard deviation or median (range). Comparisons between baseline brain metastasis and categorical disease characteristics were held using chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate

ROC curve and area under the curve (AUC) were used to determine the cutoff value for NLR that predicts baseline brain metastasis. Same was done to the ANC and ALC. Multivariate analysis was done using logistic regression modeling. Adjusted and unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported.

A significance criterion of p ≤0.05 was used in the analyses. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, United States).

Results

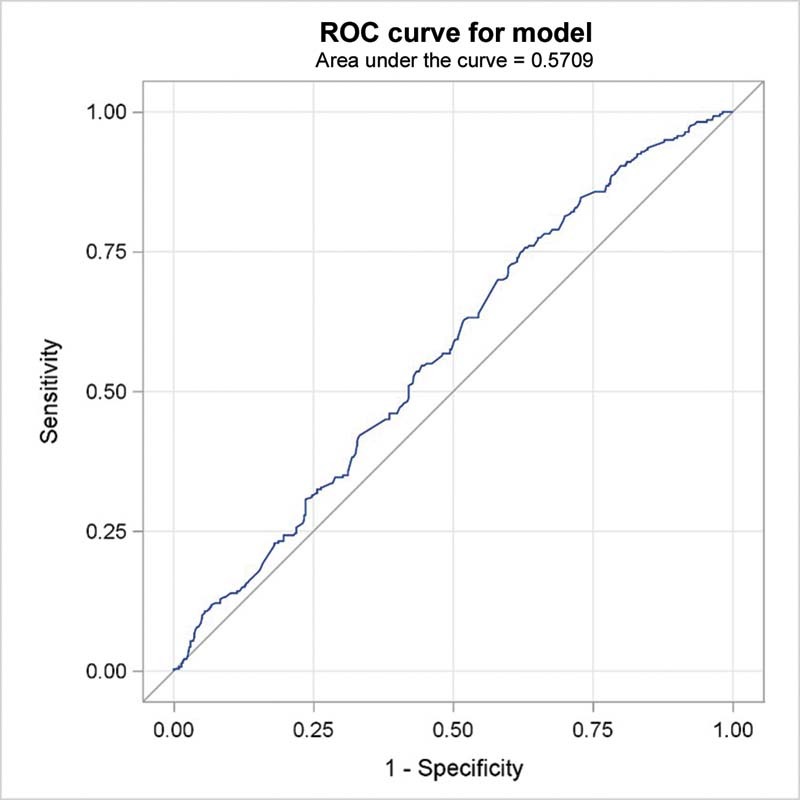

The clinical characteristics of 722 stage IV NSCLC patients were summarized in Table 1 . The majority of the patients were males (568; 78.7%). The median age at time of diagnosis was 59 years. The most common histology was adenocarcinoma consisting of 533 cases (73.8%), while 151 cases (20.9%) had squamous cell carcinoma and 38 cases (5.3%) had other histologic subtypes. Baseline brain metastasis was present in 39.3% of the patients, while 45 and 34% of the patients had baseline liver and bone metastasis, respectively. Nine patients had inconclusive findings about brain metastasis. The mean baseline NLR was 5.7, and the median was 4.2. The optimal NLR cutoff value associated with baseline brain metastasis was 4.3 using the ROC curve where the AUC was 0.5709 ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and area under the curve for neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio cutoff point for association with baseline brain metastases in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer patients.

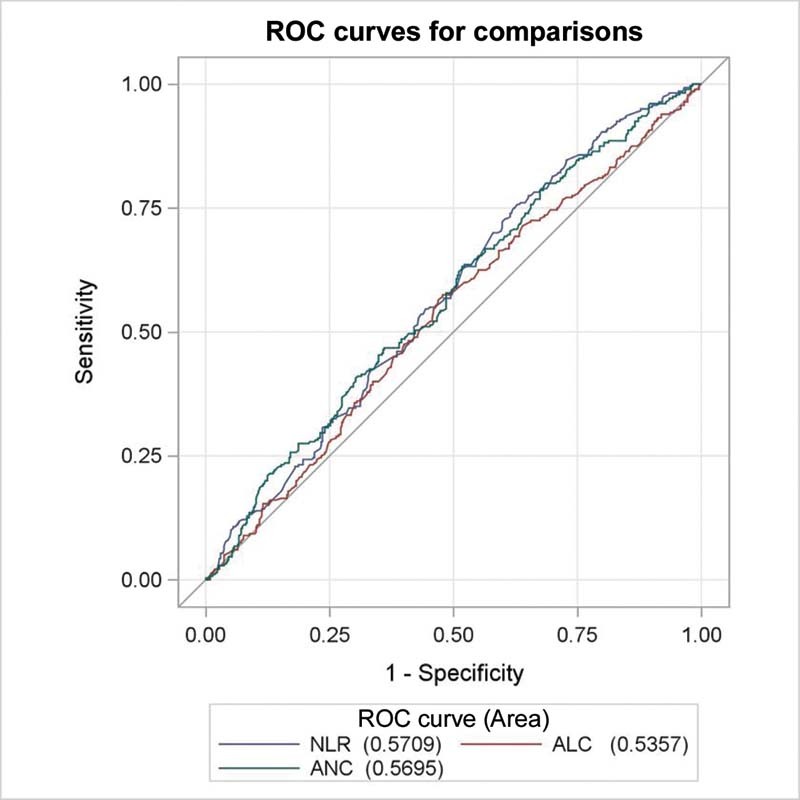

The relationship between the various inflammatory indices and baseline brain metastasis is shown in Table 2 . Patients with high baseline NLR (≥4.3) were more likely to have baseline brain metastasis comparing to patients with low baseline NLR (< 4.3), ( p -value 0.011). High baseline ANC (≥8400) and low ALC (< 1,700) were associated with statistically higher risk of baseline brain metastasis ( p -values: 0.014 and 0.023, respectively). The ROC curve was utilized to determine which inflammatory index (NLR, ANC, or ALC) is the best variable associated with baseline brain metastasis as shown in Fig. 2 . The curve showed that NLR has the highest AUC followed by ANC then ALC. So, NLR was the only inflammatory variable included in the subsequent multivariate analysis. AMC, MLR, and PLR were not significantly associated with baseline brain metastasis (data not shown).

Table 2. The association between hematologic indices with the baseline presence of brain metastases.

| Baseline brain metastases | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Present ( n = 280) |

Absent ( n = 433) |

p -Value | |

| Baseline ANC≥8400 | 122 (43.6%) | 149 (34.4%) | 0.014 |

| Baseline ANC < 8400 | 158 (56.4%) | 284 (65.6%) | |

| Baseline ALC≥1700 | 125 (44.6%) | 232 (53.6%) | 0.023 |

| Baseline ALC < 1700 | 155 (55.4%) | 201 (46.4%) | |

| Baseline AMC≥700 | 138 (49.3%) | 223 (51.5%) | 0.560 |

| Baseline AMC < 700 | 142 (50.7%) | 210 (48.5%) | |

| Baseline NLR≥4.3 | 150 (53.6%) | 190 (43.9%) | 0.011 |

| Baseline NLR < 4.3 | 130 (46.4%) | 243 (56.1%) | |

| Baseline MLR≥0.4 | 149 (53.2%) | 232 (53.6%) | 0.920 |

| Baseline MLR < 0.4 | 131 (46.8%) | 201 (46.4%) | |

| Baseline PLR≥0.2 | 142 (50.7%) | 214 (49.4%) | 0.730 |

| Baseline PLR < 0.2 | 138 (49.3%) | 219 (50.6%) |

Abbreviations: ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; AMC, absolute monocyte count; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; NLR, neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio; MLR, monocyte–lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet–lymphocyte ratio.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR), absolute neutrophil count (ANC), and absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) for predicting brain metastases.

The results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses exploring the association of the clinical variables (including NLR) with baseline brain metastasis were summarized in Table 3 . Patients with adenocarcinoma had more baseline brain metastasis compared with patients with squamous cell carcinoma or other histologic subtypes, ( p -value 0.001). Younger patients (≤59 years) had more brain metastasis ( p -value 0.024). Gender and location of the primary tumor were not associated with baseline brain metastasis in the univariate analysis ( p -values = 0.900 and 0.390, respectively). Although gender and location of the primary tumor were not associated with baseline brain metastasis in the univariate analysis, we included them in the multivariate analysis because of their clinical relevance. In the multivariate analysis, lung adenocarcinoma and NLR were significantly associated with baseline brain metastasis ( p -value < 0.0001 and 0.0042, respectively). The other factors (age, gender, and location of the primary tumor) were not associated with baseline brain metastasis ( p -values = 0.0502, 0.700, and 0.640, respectively).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis for the association of different variables with the presence of baseline brain metastases.

| Baseline brain metastases | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Present ( n = 280) |

Absent ( n = 433) |

p -Value | OR (95% CI) | p -Value | OR (95% CI) |

| Age | 0.024 | 0.0502 | ||||

| Age > 59 | 118 (42.1%) | 220 (50.8%) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | ||

| Age≤59 | 162 (57.9%) | 213 (49.2%) | ||||

| Gender | 0.900 | 0.700 | ||||

| Female | 60 (21.4%) | 91 (21.0%) | 0.97 (0.7–1.4) | 1.0 (0.72–1.56) | ||

| Male | 220 (78.6%) | 342 (79.0%) | ||||

| Location | 0.390 | 0.640 | ||||

| Upper | 126 (45.0%) | 195 (45.0%) | 1.09 (0.74–1.6) | 1.0 (0.74–1.6) | ||

| Middle | 6 (2.1%) | 17 (3.9%) | ||||

| Lower | 67 (23.9%) | 113 (26.1%) | ||||

| Others | 81 (28.9%) | 108 (24.9%) | ||||

| Histology | 0.001 | 0.0001 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 234 (83.6%) | 292 (67.4%) | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | 0.4 (0.25–0.6) | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 36 (12.9%) | 113 (26.1%) | ||||

| Others | 10 (3.6%) | 28 (6.5%) | ||||

| Baseline NLR | 0.011 | 0.0042 | ||||

| NLR > 4.3 | 150 (53.6%) | 190 (43.9%) | 1.5 (1.1–1.99) | 1.6 (1.2–2.2) | ||

| NLR≤4.3 | 130 (46.4%) | 243 (56.1%) | ||||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NLR, neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

In this study, elevated baseline NLR (≥ 4.3) was an independent factor associated with higher odds of baseline brain metastasis in stage IV NSCLC (OR: 1.6, 95% CI: 1.2–2.2; p = 0.0042) ( Table 3 ). To our knowledge, this is the largest study showing association between higher levels of NLR and presence of baseline brain metastasis in stage IV NSCLC.

The brain is one of the most common sites for lung cancer metastasis. 1 3 Using simple tests such as CBC and differential white cell count to predict presence of baseline brain metastasis, and potentially assessing the likelihood of subsequent development of brain metastasis, could have an important impact on NSCLC management. Surveillance for brain metastasis through more frequent brain imaging and consideration for prophylactic cranial irradiation in NSCLC patients 19 with high NLR could be an attractive area for future research.

Treatment of brain metastasis in NSCLC includes radiation, TKIs, and rarely surgery. Although NLR was shown to predict response to immunotherapy in stage IV NSCLC, 20 whether NLR correlates with brain metastasis response to treatment is unknown. Whole brain radiation or stereotactic radiosurgery is the most commonly used approach to treat brain metastasis. Recently, new-generation EGFR and ALK TKIs are showing promising results in treating brain metastasis in small subsets of genetically driven NSCLC patients. 21 22 New reports are also showing responses and prolonged control of brain metastasis in NSCLC patients receiving immunotherapy. 23 A major advancement in the management of stage IV NSCLC will be achieved if NLR is confirmed to be a predictor of brain metastasis response to immunotherapy or other available treatments, given the dramatic progress in the immunotherapy field nowadays. 24

Limitations of this study include the retrospective nature of the data collected with all cases coming from one cancer center, unknown EGFR or ALK status, and no data on survival metrics.

Conclusion

Elevated baseline NLR might be associated with baseline brain metastasis in stage IV NSCLC. This inflammatory-brain metastasis association is worthy of further studying in prospective trials, and might be used as a stratification tool to assess the need for more frequent brain surveillance imaging, and consideration of prophylactic cranial irradiation in stage IV NSCLC with high NLR. It is unknown if high NLR is predictive of brain metastasis response to treatments such as immunotherapy that is also an important area for future research.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Kamal Alrabi, Dr. Sameer Yaser, Dr. Jun Zhang, Dr. Muhammad Furqan, and Dr. Gerald Clamon for their guidance throughout this project.

Funding Statement

Funding None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Schouten L J, Rutten J, Huveneers H AM, Twijnstra A. Incidence of brain metastases in a cohort of patients with carcinoma of the breast, colon, kidney, and lung and melanoma. Cancer. 2002;94(10):2698–2705. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popper H H. Progression and metastasis of lung cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35(01):75–91. doi: 10.1007/s10555-016-9618-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stenbygaard L E, Sørensen J B, Larsen H, Dombernowsky P. Metastatic pattern in non-resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Oncol. 1999;38(08):993–998. doi: 10.1080/028418699432248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali A, Goffin J R, Arnold A, Ellis P M. Survival of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer after a diagnosis of brain metastases. Curr Oncol. 2013;20(04):e300–e306. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grivennikov S I, Greten F R, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140(06):883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore M M, Chua W, Charles K A, Clarke S J. Inflammation and cancer: causes and consequences. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87(04):504–508. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abu-Shawer M, Abu-Shawer O, Souleiman M. Hematologic markers of lung metastasis in stage IV colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2019;50(03):428–433. doi: 10.1007/s12029-018-0089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haimour A, Abu-Shawer O, Abu-Shawer M. The clinical potential of circulating immune cell counts in primary gastric lymphoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;12(02):365–376. doi: 10.21037/jgo-20-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abu-Shawer O, Abu-Shawer M, Haimour A. Hematologic markers of distant metastases in gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10(03):529–536. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2019.01.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abu-Shawer O, Abu-Shawer M, Shurman A. The clinical value of peripheral immune cell counts in pancreatic cancer. PLoS One. 2020;15(06):e0232043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232043c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie D, Allen M S, Marks R. Nomogram prediction of overall survival for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer incorporating pretreatment peripheral blood markers. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;53(06):1214–1222. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koh Y W, Choi J-H, Ahn M S, Choi Y W, Lee H W. Baseline neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio is associated with baseline and subsequent presence of brain metastases in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6(01):38585. doi: 10.1038/srep38585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swierczak A, Mouchemore K A, Hamilton J A, Anderson R L. Neutrophils: important contributors to tumor progression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015;34(04):735–751. doi: 10.1007/s10555-015-9594-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balkwill F, Mantovani A.Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 2001357(9255):539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen D S, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(01):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma J, Xu H, Wang S. Immunosuppressive role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and therapeutic targeting in lung cancer. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:6.319649E6. doi: 10.1155/2018/6319649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shoenfeld Y, Gurewich Y, Gallant L A, Pinkhas J. Prednisone-induced leukocytosis. Influence of dosage, method and duration of administration on the degree of leukocytosis. Am J Med. 1981;71(05):773–778. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakagawa M, Terashima T, D'yachkova Y, Bondy G P, Hogg J C, van Eeden S F. Glucocorticoid-induced granulocytosis: contribution of marrow release and demargination of intravascular granulocytes. Circulation. 1998;98(21):2307–2313. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.21.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Ruysscher D, Dingemans A C, Praag J. Prophylactic cranial irradiation versus observation in radically treated stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized phase III NVALT-11/DLCRG-02 study. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(23):2366–2377. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.5817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khunger M, Patil P D, Khunger A. Post-treatment changes in hematological parameters predict response to nivolumab monotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0197743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ALEX Trial Investigators . Peters S, Camidge D R, Shaw A T. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(09):829–838. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.FLAURA Investigators . Soria J-C, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(02):113–125. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong A. The emerging role of targeted therapy and immunotherapy in the management of brain metastases in non-small cell lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2017;7:33. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abu-Shawer O, Bushnaq T, Abu-Shawer M. Cancer immunotherapy: an updated overview of current strategies and therapeutic agents. Gulf J Oncolog. 2019;1(29):76–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]