Abstract

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are present in many types of tumors and play a pivotal role in tumor progression and immunosuppression. Fibroblast-activation protein (FAP), which is overexpressed on CAFs, has been indicated as a universal tumor target. However, FAP expression is not restricted to tumors, and systemic treatment against FAP often causes severe side effects. To solve this problem, a photodynamic therapy (PDT) approach was developed based on ZnF16Pc (a photosensitizer)-loaded and FAP-specific single chain variable fragment (scFv)-conjugated apoferritin nanoparticles, or αFAP-Z@FRT. αFAP-Z@FRT PDT efficiently eradicates CAFs in tumors without inducing systemic toxicity. When tested in murine 4T1 models, the PDT treatment elicits anti-cancer immunity, causing suppression of both primary and distant tumors, i.e. abscopal effect. Treatment efficacy is enhanced when αFAP-Z@FRT PDT is used in combination with anti-PD1 antibodies. Interestingly, it is found that the PDT treatment not only elicits a cellular immunity against cancer cells, but also stimulates an anti-CAFs immunity. This is supported by an adoptive cell transfer study, where T cells taken from 4T1-tumor-bearing animals treated with αFAP PDT retard the growth of A549 tumors established on nude mice. Overall, our approach is unique for permitting site-specific eradication of CAFs and inducing a broad spectrum anti-cancer immunity.

Keywords: photodynamic therapy, immunotherapy, immunomodulation, cancer associated fibroblast, fibroblast activation protein

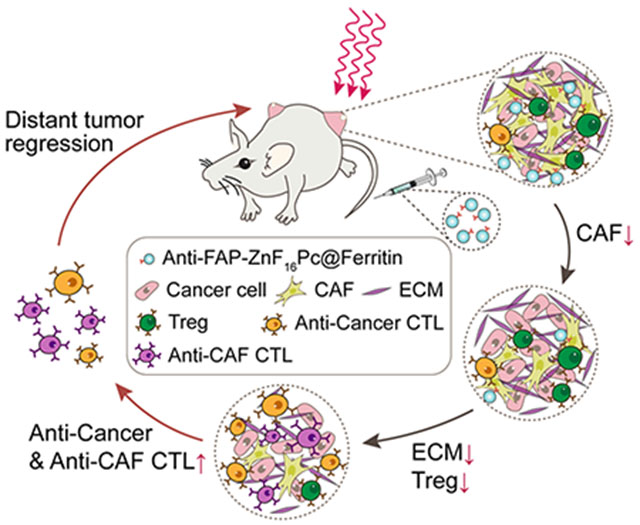

Graphical Abstract

Anti-FAP photodynamic therapy, mediated by ZnF16Pc-loaded and single-chain variable-fragment (scFv)-conjugated ferritin nanoparticles, eliminates cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in a specific fashion. This results in destructed extracellular matrix and reduced recruitment of regulatory T cells. In turn, the treatment enhances the expansion of anti-cancer and anti-CAF cytotoxic T lymphocytes, eliciting an immunity that inhibits tumor growth.

1. Introduction

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are the most abundant cell type in the tumor stroma.[1] Unlike normal fibroblasts that often inhibit tumor progression, CAFs are involved in promoting tumor growth. Specifically, CAFs secrete growth factors such as VEGFA, EGF, FGF, and HGF, which stimulate cancer cell proliferation and tumor angiogenesis.[2] CAFs produce various types (I, III, IV, V) of collagens, fibronectin, and laminins, as well as extracellular matrix (ECM)-degrading proteases such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA);[3] these molecules enhance tumor ECM remodeling and as a result promote cancer cell migration and metastasis. CAFs are also involved in tumor drug resistance through inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), upregulating glutathione, or directly scavenging therapeutics.[3a, 4] Due to widespread implications, there has been a great interest of developing CAF-targeted therapies. One promising CAF target is fibroblast activation protein (FAP), a membrane-bound glycoprotein that is upregulated in CAFs but not in normal fibroblasts.[3b] In fact, FAP is positive in over 90% of human cancers,[5] making it a promising generic target for solid tumors. Recently, FAP-targeted immunotoxins (FAP5-DM1[6] and αFAP-PE38[7] conjugates), humanized monoclonal antibodies (F19[8]), DNA vaccines,[9] and CAR T therapy[10] have been developed. However, the test results were mixed. One common problem is that FAP is also expressed in normal tissues such as the placenta, uterus, embryo, and bone marrow.[11] Hence, a systemic FAP-targeted therapy may cause severe or even lethal toxicities.[12]

To address the issue, we have proposed a PDT approach for targeted CAF elimination.[13] PDT is a focal treatment modality, exploiting radicals generated from activated photosensitizers to induce cell damage.[14] In a typical PDT regimen, patients are administered with photosensitizers and photo-irradiation is applied to the lesions after a certain drug-light interval. This activates the photosensitizers, which transfer energy to nearby O2 to produce cytotoxic 1O2 among other reactive oxygen species.[15] Given the short-lived nature of radicals, the impact of CAF-targeted PDT is confined to photo-irradiated areas (e.g. tumors), thus minimizing side effects to FAP+ cells in normal tissues. Specifically, we have loaded ZnF16Pc (zinc hexadecafluorophthalocyanine), a potent photosensitizer (λmax = 671 nm; ΦΔ = 0.85),[16] onto apoferritins (FRTs), and conjugated onto the FRTs surface a single chain variable fragment (scFv) that is FAP-specific. FRTs are compact drug carriers (~ 12 nm in diameter) and can efficiently diffuse through tumor mass and bind to CAFs.[17] FRTs are efficient at photosensitizer encapsulating, loading up to 200 ZnF16Pc molecules in its cavity (as a comparison, antibodies, which have similar sizes to FRTs, can each be coupled with a 5-10 photosensitizers).[18] Our previous studies showed that ZnF16Pc loaded anti-FAP FRTs (abbreviated as αFAP-Z@FRTs) can selectively accumulate in tumors and, with photo-irradiation, efficiently eradicate CAFs.[13]

CAFs are also a major player in the often immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME).[19] CAFs achieve this by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines including TGF-β, IL-6, CCL2, and CXCL12, which recruit immuno-suppressive cells such as regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) into the tumor stroma.[20] Furthermore, CAFs prevent cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) from migrating into tumors by depositing a dense layer of ECM and secreting CXCL12.[21] Last but not least, CAFs express programmed cell death ligand 1/2 (PD-L1/2), which engage with PD-1 to cause T cell anergy.[22] Eliminating CAFs may boost the immune response to improve tumor control, a notion that was supported by our previous studies.[13] However, whether antigen specific immunity is elicited by anti-FAP (αFAP) PDT and whether the treatment elicits sustained tumor protection is unknown. Moreover, in addition to inducing a cancer-cell-targeted immune response, αFAP PDT may also elicit an anti-CAF immunity. If so, anti-CAF PDT may serve as a unique tumor vaccination approach, given that CAFs are present in almost all solid tumors and are genetically more stable than cancer cells.[23] Herein we tested these hypotheses in syngeneic mouse models established with 4T1 cells.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preparation and characterization of ZnF16Pc-loaded, anti-FAP-scFv-conjugated FRTs (αFAP-Z@FRTs)

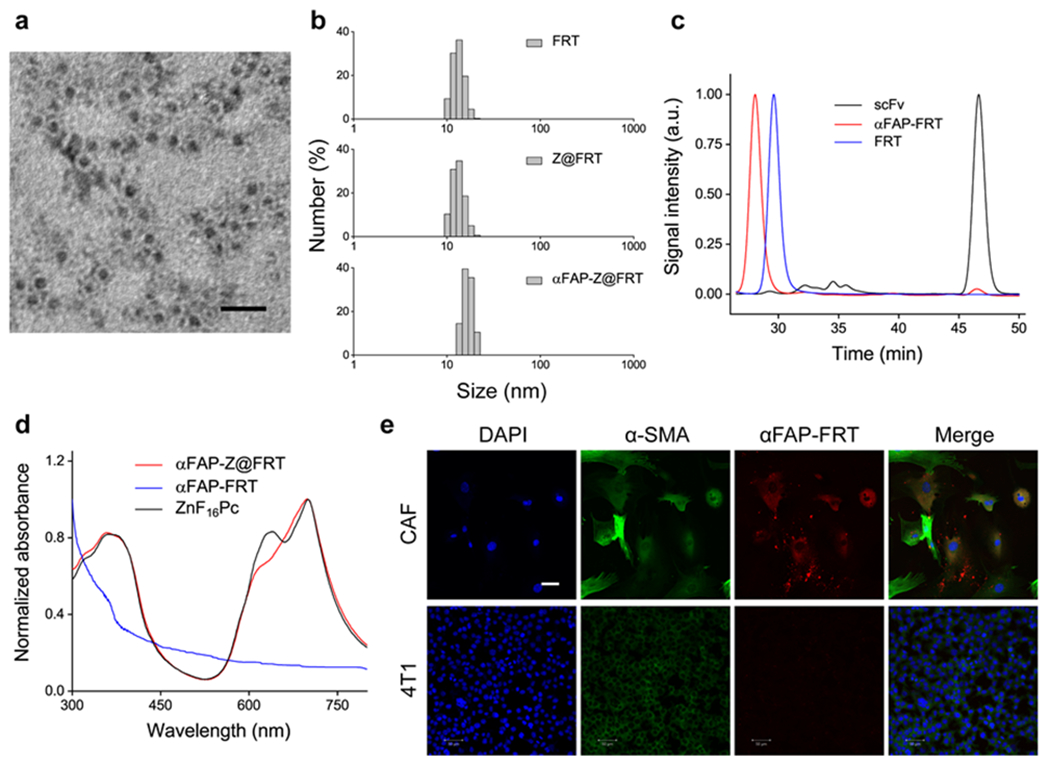

FRTs consists of 24 subunits.[24] While natural FRTs contain both heavy and light subunits, we used recombinant mouse FRTs made of heavy chains only. FRTs were expressed following our published protocol[13] and purified by size exclusion chromatography (SEC). SDS-PAGE found a single band at ~21 kDa, which coincides with the molecular weight of heavy chain FRTs (Figure S1, Supporting Information). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Figure 1a) showed that FRTs were ~12 nm in diameter, which corroborates with our previous observation.[16]

Figure 1.

Characterizations of αFAP-Z@FRT. (a) TEM image of ferritin (FRT), with uranium acetate staining. Scale bar, 20 nm. (b) DLS analysis. The hydrodynamic sizes were 13.3 ± 2.0, 13.3 ± 2.1, and 16.8 ± 2.1 nm, respectively, for FRT, ZnF16Pc-loaded FRT (Z@FRT), anti-FAP-scFv-conjugated Z@FRT (αFAP-Z@FRT), in PBS (pH 7.4). (c) SEC analysis. The retention times (tR) were 28.1, 29.6, and 46.6 min, respectively, for αFAP-FRT, FRT, and scFv. (d) UV-vis analysis. The absorbance spectra of αFAP-Z@FRT, αFAP-FRT, and ZnF16Pc in PBS. For ZnF16Pc, 1% Tween 20 was added to the solution to improve solubility. (e) Confocal microscopy images. CAF and 4T1 cells were incubated with rhodamine-conjugated αFAP-FRTs for 12 h before taking images. Scale bar, 50 μm.

We then loaded ZnF16Pc into FRTs by exploiting pH-dependent de-assembly and re-assembly of the protein cages. Specifically, we decreased the pH of FRT solutions to 2.0, which led to FRT dissociation.[25] We then added ZnF16Pc in DMSO into the solution and slowly adjusted the pH back to 7.4. This caused reconstitution of the protein cages and encapsulation of ZnF16Pc into them. We passed the resulting, ZnF16Pc-loaded FRTs through a NAP-10 column to remove excessive ZnF16Pc molecules. UV-vis spectroscopy analysis determined that the ZnF16Pc loading rate was ~12 wt% (Figure 1d). While ZnF16Pc is poorly water soluble, ZnF16Pc-encapsulated FRTs (Z@FRTs) are well dispersed in PBS (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Notably, there was ZnF16Pc little release from FRTs (Figure S3, Supporting Information), which was attributed to the relatively bulky molecule size and its hydrophobicity. Despite high loading rate, minimal self-quenching was observed with Z@FRTs (Figure S4, Supporting Information).

We then conjugated a FAP-specific scFv to FRT surface. The anti-FAP scFv was expressed and purified following a published protocol with minor modifications.[13] Briefly, the anti-FAP scFv sequence (VH and VL linked by a 4×GGGGS spacer) was inserted into a pOPE101 plasmid to transduce E. coli. The polypeptide was collected by metal affinity chromatography and its molecular weight (26 kDa) was confirmed by SDS-PAGE (Figure S1, Supporting Information). The scFv was conjugated to Z@FRTs using a crosslinker, bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate or BS3.[13] The resulting nanoparticles, i.e. αFAP-Z@FRTs, were collected on a centrifugal filter unit (MWCO = 100 KDa). On average, 6.3 ± 2.2 scFv molecules were coupled to each FRT cage. The scFv coupling slightly increased the overall nanoparticle size. This was observed by dynamic light scattering (DLS), which found that the hydrodynamic size was increased from 13.3 ± 2.1 nm for Z@FRTs to 16.8 ± 2.1 nm for αFAP-Z@FRTs (Figure 1b). SEC confirmed the size increase, finding that the retention time (tR) was decreased from 29.6 min for FRTs to 28.1 min for αFAP-FRTs (Figure 1c; note that the tR of scFv was 46.6 min).

2.2. CAF targeting by αFAP-Z@FRTs

We then investigated CAF targeting of αFAP-Z@FRTs. This was first studied in vitro with CAFs and 4T1 cells. CAFs were isolated from a 4T1 xenograft using a magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS) kit. To keep track of the nanoparticles, αFAP-FRTs were labeled with rhodamine before incubation (see Experimental section). CAFs are greater in size than 4T1 cells (Figure 1e), and unlike spindle-like normal fibroblasts, CAFs are stelliform in shape (Figure 1e). Moreover, CAFs were stained positively for α-SMA and manifested characteristic stress fiber structures of myofibroblasts (Figure 1e). These characteristics are consistent with previous reports.[26] It was found that αFAP-FRTs were efficiently taken up by CAFs, but barely bound to 4T1 cells, which are FAP-negative (Figure 1e).

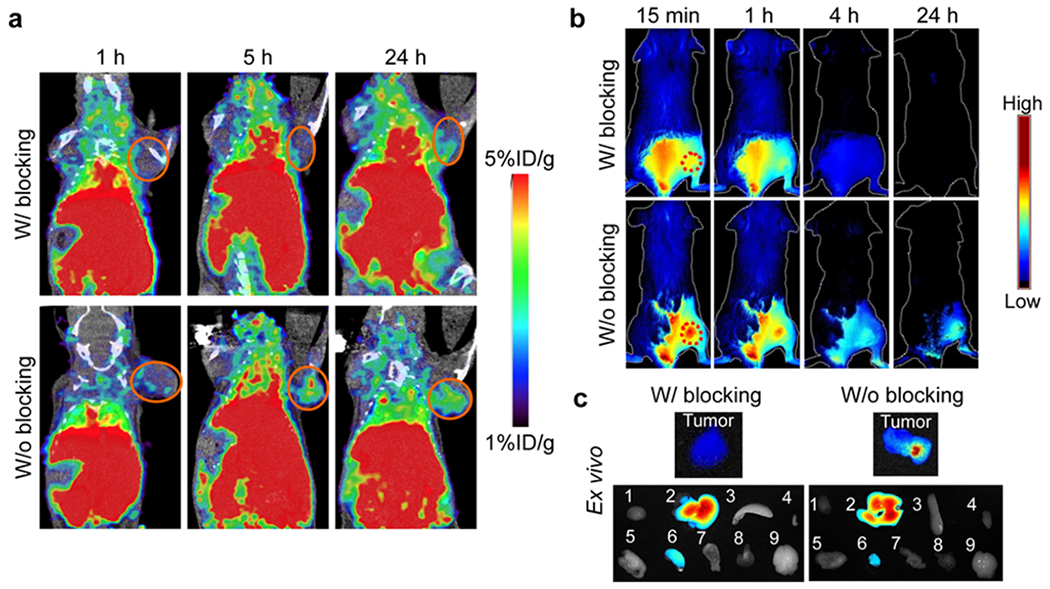

We next studied tumor targeting in vivo. To this end, we labeled αFAP-Z@FRTs with either 64Cu-DOTA or IRDye 800, and intravenously (i.v.) injected the conjugates into 4T1 bearing BALB/c mice (n = 3). Probe accumulation in tumors was assessed by positron emission tomography (PET) and fluorescence imaging. PET scans found gradual increase of activity in tumors, with tumor uptake of 1.66 ± 0.02, 3.41 ± 0.24 and 3.14 ± 0.25%ID/g at 1, 5, and 24 h, respectively. When free scFv (30 ×) was co-injected, the tumor uptake was reduced to 1.37, 1.65 and 1.47 %ID/g at 1, 5, and 24 h, respectively (Figure 2a). These results suggest that αFAP-Z@FRTs after i.v. injection accumulated in tumors through FAP-scFv interaction. Similar results were observed with fluorescence imaging (Figure 2b). After 24 h, we euthanized the animals, collected tumors and major organs, and performed ex vivo scans. We found that tumor uptake of αFAP-Z@FRTs was decreased by 9.7 folds when free scFv was co-injected. Meanwhile, comparable nanoparticle uptake was observed in major organs such as the liver and kidneys (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

In vivo imaging studies. (a) PET images, taken at 1, 5, and 24 h after i.v. injecting 64Cu-labeled αFAP-FRTs into 4T1 bearing mice. For blocking, 30× free scFv was co-injected with the nanoparticles. (b) In vivo fluorescence images, taken at 1, 5, and 24 h after i.v. injecting IRDye800 labeled αFAP-FRTs into 4T1 bearing mice. The tumor area was shaven before the imaging studies. For blocking, 30× free scFv was co-injected with the nanoparticles. (c) Ex vivo fluorescence images. After the 24-h imaging, animals from b) were euthanized and the tumor and major organs were taken for ex vivo imaging. The major organs, labeled 1-9, were heart, liver, spleen, skin, lung, kidney, intestine, muscle, and brain, respectively.

2.3. Therapy studies with αFAP-Z@FRTs-mediated PDT

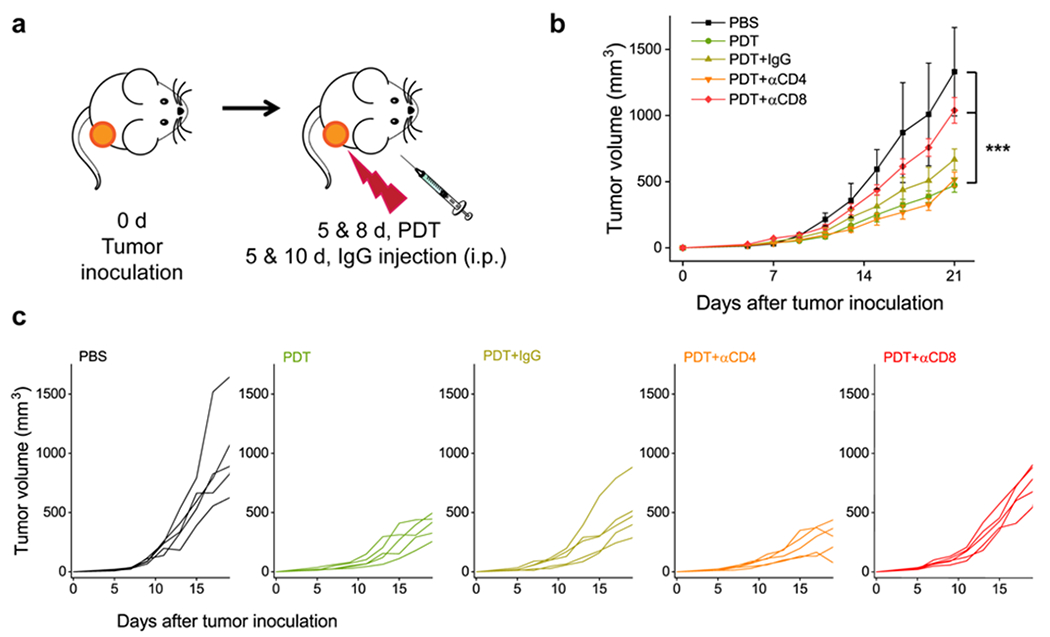

We next studied the therapeutic effects of PDT in 4T1 tumor models. Briefly, we i.v. injected αFAP-Z@FRTs (0.5 mg ZnF16Pc/kg) into the animals, and applied photo-irradiation (671 nm, 300 mW/cm2 for 15 min) to tumors at 24 h (n = 5). We chose 24 h instead of an earlier time point (e.g. 5 h) because FRTs have relatively long blood circulation half-lives,[16] hence early irradiation may induce vasculature damage, which is undesired in the current application. For complete CAF elimination, we performed two PDT procedures that were three days apart (Figure 3a). The treatment caused effective tumor suppression, leading to tumor inhibition by 65.3% on Day 21 (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

T cell depletion studies. Two sessions of αFAP PDT were given to 4T1 bearing BALB/c mice, along with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, or mouse IgG antibodies (n=5). (a) Schematic illustration of the treatment protocol. (b) Tumor growth curves. ***, P < 0.001. (c) Individual tumor growth curves.

In separate groups, we intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected anti-CD4 (αCD4) or anti-CD8 (αCD8) antibodies into 4T1 tumor bearing BALB/c mice (200 μg per injection per mouse, given on Day 5 and 10; n = 5; Figure 3a); these antibodies would eliminate CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in the animals. For comparison, we also tested PDT in combination with non-specific IgG. IgG and αCD4 showed a minimal impact on the treatment outcome. For both groups, there was no significant change in tumor volume (Day 21) compared with the PDT-only control (P = 0.078 and 0.758, respectively). On the contrary, CD8+ cell depletion significantly accelerated tumor growth (P = 0.000905). These results suggest that αFAP-PDT elicited a cellular immunity that was a major cause of the tumor suppression.

2.4. Abscopal effect induced by αFAP-Z@FRT PDT

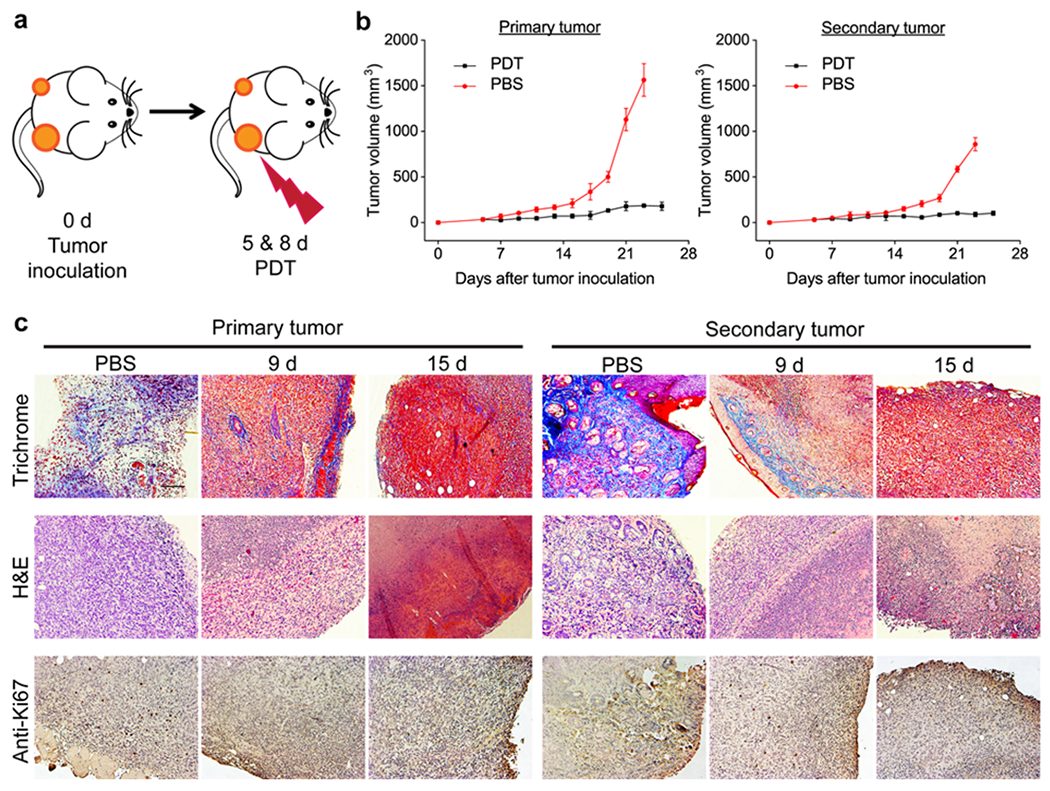

We then tested the efficacy of αFAP PDT in bilateral 4T1 tumor models. Specifically, we i.v. injected αFAP-Z@FRTs (0.5 mg ZnF16Pc/kg) into animals on Day 4 and 7 post tumor inoculation. We then applied photo-irradiation (671 nm laser, 300 mW/cm2 for 15 min) 24 h post the particle injection onto the primary tumors, leaving the contra-lateral tumors un-irradiated (Figure 4a). The growth of both primary and secondary tumors was monitored. Similar to single-tumor model studies, PDT treatment effectively suppressed primary tumors, causing tumor inhibition by 90.2% on Day 23. Meanwhile, the growth of the secondary tumors was also retarded. On Day 23, the secondary tumors had a size of 88.8 ± 25.1 mm3, compared to 859.7 ± 72.8 mm3 for the untreated animals (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Abscopal effect by αFAP PDT. (a) Schematic for the treatment plan. The studies were performed on a s.c. 4T1 bilateral tumor model. Two PDT treatments were applied to the primary, but not the secondary, tumor. (b) Tumor growth curves. PDT treatment led to suppression of both primary and secondary tumors. (c) Masson’s trichrome, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and anti-Ki67 staining results. Primary and secondary tumors were taken from animals euthanized on Day 9 and 15 (i.e. 1 day and 1 week after the second PDT). Scale bar = 100 μm.

For better assessment, we repeated the study but euthanized the animals on Day 9 and 15, and collected tumors for histopathology analysis (Figure 4c). In both primary and secondary tumors, we observed a significantly reduced cancer cell population in the PDT group, along with a decreased level of anti-Ki67 positive staining (for primary tumors, the positively stained area of untreated mice was 16.00 and 5.15 times as large as PDT-treated mice on Day 9 and 15, respectively; for secondary tumors, the difference was 6.16- and 7.27-fold, respectively, on Day 9 and 15; Figure S5). In addition, we performed Masson’s trichrome staining, which examines the level of collagen in the ECM. Both primary and secondary tumors showed a reduced level of positive staining (Figure 4c). This is because CAFs are the main source of collagen in tumors, hence CAFs elimination leads to reduced collagen deposition. Notably, more severely destructed ECM was observed on Day 15 than on Day 9, indicating persisted CAF eradication. Overall, these results suggest that αFAP-Z@FRT PDT can induce a cellular immunity that slows down the development of a secondary, distant tumor, i.e. abscopal effect.

2.5. Combination therapy with αFAP-Z@FRT PDT and immune checkpoint blockade therapy

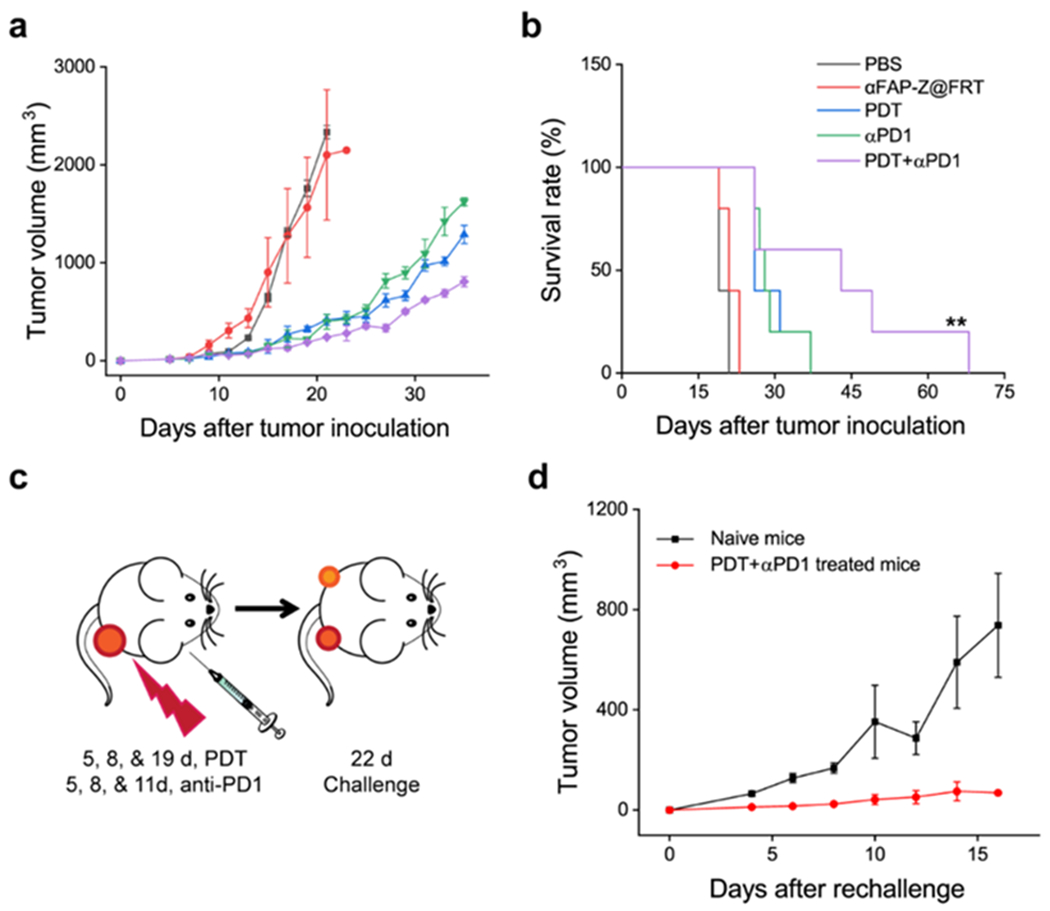

We next examined whether immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti-PD-1 (αPD1) antibodies can be used along with αFAP PDT to improve tumor control. αPD1 antibodies bind to PD-1 expressed on T cells and in doing so remove inhibitory signals of T cell activation.[27] We expect this effect to synergize with αFAP PDT to enhance anti-tumor immune response. This was tested in BALB/c mice bearing a single 4T1 xenograft. The animals again received two sessions of αFAP PDT, which were applied on Day 5 and 8 after tumor inoculation. Meanwhile, three doses of αPD1 antibodies (10 mg/kg) were i.p. administrated on Day 5, 8, and 11 (immediately after PDT on Day 5 and 8). The combination of αFAP PDT and αPD1 outperformed either monotherapy, manifested in significantly improved tumor suppression (Figure 5a&b). The mean animal survival was 42.4 days for the combination group, compared to 19.8, 21.4, 29.2, and 29.4 days, respectively, for the PBS, αFAP-Z@FRT, αFAP PDT, and αPD1 groups (Figure 5b). Meanwhile, there was no sign of toxicity associated with the combination treatment.

Figure 5.

Combining αFAP PDT with anti-PD1 antibodies improved tumor control. The studies were performed on BALB/c mice that bore single 4T1 tumors. (a) Tumor growth curves and (b) animal survival curves. **, P < 0.01. (c) Schematic for tumor challenge studies. A secondary tumor was inoculated 22 days after the primary tumor inoculation. (d) Growth curves of the secondary tumors.

The αFAP PDT and αPD1 combination also led to a strong abscopal effect. This was tested in a separate study where live 4T1 cells were injected into the contralateral flank of animals that had received combination treatment of αFAP PDT and αPD1. We found that 25% of the animals completely rejected the secondary tumor (Figure 5d). The remainder animals also manifested significantly retarded tumor progression, showing an average tumor growth suppression of 90.6% on Day 16 (Figure 5d).

2.6. Anti-tumor and anti-CAF immunity induced by αFAP-Z@FRT PDT

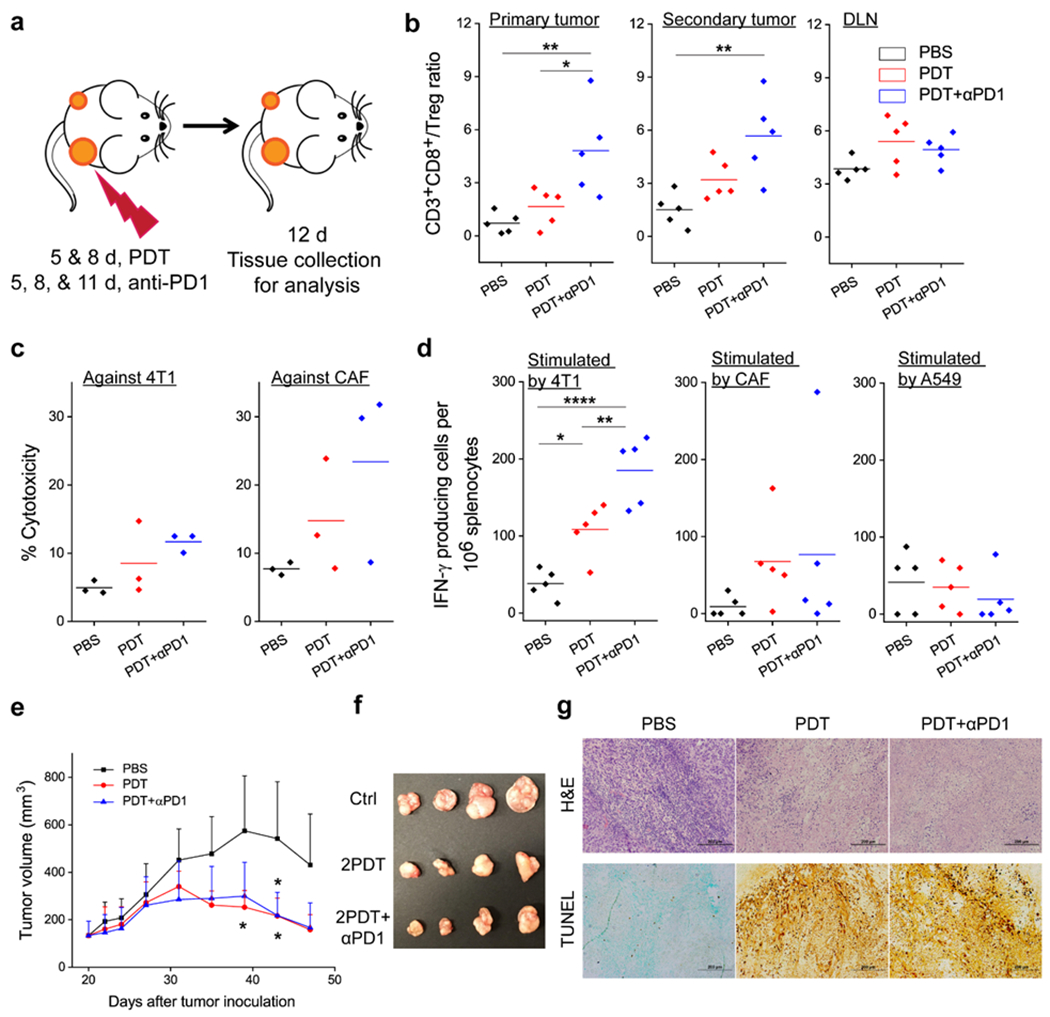

To better understand the cellular immunity, we analyzed infiltrating lymphocytes in the primary and secondary tumors as well as in the draining lymph nodes (DLN, tissues were taken on Day 12, i.e. one week after the first PDT, Figure 6a). Relative to the PBS control, the CD8+/Treg ratio in PDT treated animals was increased by ~1.6, 3.2, and 5.4-fold in primary tumors, secondary tumors, and DLNs, respectively (Figure 6b). The increase was even more prominent in the αFAP PDT and αPD1 combination group, where the CD8+/Treg ratio was increased by 4.8 and 5.7-fold, respectively, in primary and secondary tumors. This again is attributed to the synergy of the two components in the combination therapy: while αFAP PDT depletes CAFs and inhibits the recruitment of Tregs to tumors,[13] αPD1 blocks the regulating signal pathway thus improving effector T cells expansion.

Figure 6.

αFAP PDT induces anti-cancer and anti-CAF immunity. (a) Schematic showing the treatment plan. Combination therapy with αFAP PDT and anti-PD1 was performed on bilateral 4T1 tumor models. (b) CD3+CD8+ to Treg (CD3+CD4+FOXP3+) ratios in primary tumor, secondary tumor, and tumor-draining lymph node (DLN), based on flow cytometry analysis. (c) Cell-specific cytotoxicity. Splenocytes were taken from animals receiving PDT, PDT+αPD1 combination therapy, or PBS, and were incubated in vitro with carboxy-fluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled 4T1 and CAF cells. Cytotoxicity was assessed by propidium iodide (PI) staining followed by flow cytometry analysis. (d) Enzyme-linked immune absorbent spot (ELISpot) analysis. Splenocytes were taken from animals receiving PDT, PDT+αPD1 combination therapy, or PBS, and were incubated in vitro with 4T1, CAF, or A549 cell debris. IFN-γ producing cells were quantified. Cell debris was obtained by treating cells with 100 Gy radiation. (e) Growth curves of A549 tumors after adoptive cell transfer. 4T1 bearing BALB/c mice were treated with PDT, PDT+αPD1, or PBS. Non-adherent splenocytes were isolated and injected into A549 bearing nude mice. Significant difference was observed between PBS and PDT or PDT+αPD1 groups. (f) Photograph of A549 tumors taken on 47 post A549 inoculation. (g) Photograph of A549 tumors taken on 47 post A549 inoculation. (h) H&E and TUNEL staining, performed with A549 tumors taken on Day 47. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

We also examined the specificity of the cellular immunity. We took splenocytes from both treated and control mice on Day 12 and then stimulated the cells in vitro with 4T1 cell debris in the presence of IL-2 (30 ng/mL). The resulting splenocytes were then incubated with carboxy-fluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled 4T1 cells, followed by propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry analysis. In both PDT and combination groups, we observed an increased population of PI+CFSE+ cells (i.e. cells killed by T cells), confirming T cell toxicity against the cancer cells (Figure 6c). We also tested T cell toxicity against CAFs following stimulation with CAF debris. Interestingly, the frequency of PI+CFSE+ CAFs was also increased. In fact, CAFs seemed to be more susceptible to T cells than 4T1 cells (Figure 6c), suggesting that the immunity elicited may contain an anti-CAF component.

To validate, we analyzed the number of IFN-γ producing T cells (i.e. effector T cells) that are specific to 4T1 and CAFs by enzyme-linked immune absorbent spot (ELISpot, Figure 6d). Relative to the PBS control (on average 38.0 per million splenocytes), the frequency of 4T1-specific effector T cells was significantly increased in the αFAP PDT group (average 108.5 per million splenocytes) and αFAP-PDT-and-αPD1 combination group (185.0 per million splenocytes). As for CAFs, the effector T cell frequency was 67.5 and 76.5, respectively, for the PDT and combination groups, compared to 9.0 for the PBS control. It is noted that there is a relatively large variance in anti-CAF response, possibly due to varied immune response among individuals. Nonetheless, these results support the hypothesis that αFAP PDT, while stimulating an immune response against cancer cells, also elicits an anti-CAF immunity.

2.7. Adoptive cell transfer for cancer treatment

The presence of CAFs in solid tumors is almost universal.[1] While cancer cells are associated with high levels of mutations, CAFs are much more stable genetically.[1] Hence, we speculate that the cellular immunity induced by αFAP PDT may help the host to reject or suppress a tumor that has a different origin. This hypothesis was assessed through an adoptive cell transfer study, where T cells from 4T1-bearing BALB/c mice that had been treated by αFAP PDT, αFAP PDT plus α-PD1, or PBS alone, were transferred to nude mice that bore A549 (human lung cancer) xenografts. Because the recipient mice are immune-deficient and lack indigenous T cells, they are unable to amount an anti-tumor immunity on their own. For animals receiving T cells from PBS-treated donors, A549 tumors grew rapidly, showing an average size of 542.1 mm3 on Day 43 (Figure 6e). Compared to the PBS group, animals receiving T cells taken from donors treated by αFAP PDT or αFAP PDT + α-PD1 showed significantly retarded tumor growth (Figure 6f). The average tumor sizes were 216.5 mm3 and 218.6 mm3, respectively, for the αFAP PDT group and combination group on Day 43. Consistent with tumor suppression, histology examination revealed extensive cell death in A549 tumors in the αFAP PDT and αFAP PDT + α-PD1 groups (Figure 6g). H&E staining found nuclei generally appeared ongoing pyknosis, karyorrhexis, or karyolysis in these tumors. TUNEL staining, which detects DNA fragmentation, also confirmed extensive apoptosis in the αFAP PDT and αFAP PDT+α-PD1 groups (Figure 6g). It is noted that ELISpot found few effector T cells when splenocytes from αFAP PDT treated animals were incubated with A549 cells (Figure 6d), indicating that there is no common antigen between 4T1 and A549 cells. In other words, transferred T cells should not directly kill A459 cells. Tumors in the recipient mice have human cancer cells but murine stroma, which contain CAFs that can be recognized by T cells (Figure 6d). Overall, the results support that anti-CAF immunity stimulated by αFAP PDT contributes to tumor suppression.

2.8. Toxicity studies

One potential concern is that an anti-CAF immunity may cause systemic toxicity to normal tissues. To investigate, we examined major organ tissues taken from 4T1 bearing BALB/c animals treated with α-FAP PDT. We also examined tissues from A549-bearing mice that had received adoptive cell transfer. In both scenarios, histology analysis found no detectable toxicity in major organs (Figure S6&8, Supporting Information). The low toxicity was also supported by the observation that there was steady body weight gain in all treated animals throughout the studies (Figure S7&9, Supporting Information).

3. Conclusion

While it is well documented that PDT can boost immune response, the type and amplitude of the immunity can vary dramatically.[28] So far, most nanoparticle-based PDT formulations deliver photosensitizers to tumors via intratumoral injection, or the EPR effect, or targeting a receptor on cancer cells.[15, 29] Our approach is unique in that we target FAP, which is overexpressed on CAFs (FAP is positive in 90% solid tumors[1]). In conventional PDT, which often targets cancer cells, the goal is to induce immunogenic cell death and the release of tumor associated antigens. Targeting CAFs is a fundamentally different approach, and the consequences of CAF elimination could be complex given the wide implications of CAFs in immunosuppressive TME. We previously reported that CAF-targeted PDT can enhance T cell infiltration into tumors, and that was correlated with improved tumor suppression.[13] However, enhanced T cell infiltration can be induced by conventional PDT, and tumor suppression could be attributed to bystander effects of PDT. In the current study, we confirmed that cytotoxic T cells are indeed a major player in the tumor suppression (Figure 3). We also showed that combing with anti-PD1 antibodies can enhance anti-cancer immunity induced by CAF elimination.

More excitingly, we found that αFAP-Z@FRT PDT can prime the host’s immune system so that it can recognize and kill not only cancer cells but also CAFs (Figure 6c&d). It is believed that the anti-CAFs community has contributed to tumor suppression of both primary and distant tumors (Figure 4c). This hypothesis is supported by an adoptive cell transfer study, where we showed that T cells taken from 4T1 tumor bearing animals that had been treated with αFAP-Z@FRT PDT can retard the growth of A549 tumors established on nude mice. This finding is highly significant because CAFs are essential to establishment of almost all solid tumors.[1] Hence, the treatment holds the potential to protect hosts from future tumor challenges, including tumors carrying different mutations or having different origins. It is worth mentioning that very recent clinical studies found that FAP-targeted positron emission tomography (PET) tracers can selectively light up solid tumors of various types.[30] This is considered a major breakthrough, indicating that we have found a targetable, universal cancer biomarker. It is widely anticipated that there will be a great expansion of diagnostic and therapeutic tools based on FAP targeting. The current study is important and timely in this context for shedding some light on the impact of αFAP PDT on TME.

In summary, we report that FAP-targeted PDT mediated by αFAP-Z@FRTs can effectively and safely deplete CAFs and by doing so, induce an anti-cancer immunity. This leads to abscopal effects, which are enhanced when the αFAP PDT is used in combination with αPD-1 antibodies. Interestingly, our results suggest that there is an anti-CAF component in the cellular immunity induced by the PDT treatment. This is significant due to the universal presence of CAFs in solid tumors. Overall, αFAP PDT represents a unique approach in tumor control and holds great potential in clinical translation.

4. Experimental Section

Cell Lines:

Murine breast cancer cell, 4T1, and human lung cancer cell, A549, were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). 4T1 was cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Corning®, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals, Cat. No. S11150H). A549 was cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Corning®, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS and MEM nonessential amino acids (100×, MediaTech, USA). All medium was further supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (100×, MediaTech, USA). Cells were cultured in humidified 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Animal Models:

BALB/c mice (4 weeks) were obtained from Harlan-Envigo Laboratories Inc. (USA) and BALB/c nude mice (4 weeks) from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. (USA). Bilateral 4T1 tumor model was established by subcutaneously (s.c.) injecting 1×106 4T1 to the right flank and 5×105 to the left flank of each BALB/c mouse. Single 4T1 tumor model was established by s.c. injecting 1×106 4T1 to the right flank of each BALB/c mouse. A549 tumor model for adoptive transfer studies was established by s.c. injecting 1×107 A549 to the right flank of each BALB/c nude mouse. The studies were conducted following a protocol approved by the University of Georgia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Expression and purification of ferritin and anti-FAP scFv:

FRTs were expressed and purified as previously reported.[31] In brief, PCR was used to amplify FRT from cDNA using respective primers to introduce NcoI and XhoI restriction sites flanking the normal start and stop codons. The double digested PCR product was ligated to NcoI/XhoI digested plasmid pRSF when catalyzed by T4 DNA ligase. The resulting pRSF/FRT plasmids were screened by appropriate restriction digests, verified by DNA sequencing, and then used to transform the expression strain E. coli BL21 (DE3). For expression, a 1 L LB-ampicillin (50 μg/mL) culture of E. coli BL21(DE3)/FRT was grown at 37 °C until OD600 reached 0.8. Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, final concentration: 1 mM) was added to induce production of proteins and the culture was carried out at 37 °C for 4 h. The harvested bacteria were sonicated and then centrifuged at 30,000 g for 30 min to remove cell debris. The supernatant was incubated at 60 °C for 10 min and centrifuged at 30,000 g for 30 min to remove precipitates. The raw product was purified by HPLC on a Superose 6 size exclusion column (GE Healthcare, USA). The concentration of FRTs was determined by Bradford protein assay. The purified FRTs were stored at −80 °C. Size exclusion chromatography study was also performed on a Superose 6 column using PBS as the mobile phase.

The anti-FAP scFv was expressed and purified following a modified protocol published before.[13] The anti-FAP scFv sequence was reported by Brocks B et al.[32] NcoI and HindIII restriction sites were introduced to the heavy chain, flanking the normal start and stop codons. MluI and NotI were introduced to the light chain. The resulting sequence was inserted to a pOPE101 plasmid and transformed into E. coli JM109 with ampicillin resistance. A PelB signal peptide was added to the N-terminus of scFv, directing the translated scFv to bacteria periplasm, where the scFv completed its folding into active structure. To produce anti-FAP scFv, a 1 L LB-ampicillin (25 μg/mL) culture of E. coli JM109 was grown at 37 °C until OD600 of 0.8 was reached. IPTG (final concentration: 0.1 mM) was added to induce the production of proteins and the bacteria were incubated at 23 °C for 24 hours. The bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 g. Cell lysis took place via sonification. The cell lysate was then centrifuged at 30,000g for 30 min to remove cell debris and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.2 μm filter. A Ni-NTA cartridge (Qiagen Sciences Inc.) was connected to HPLC and rinsed with 10-fold column volume (10 mL) of binding buffer, NPI-10. The filtered supernatant was then loaded onto the Ni-NTA cartridge at 0.5 mL/min. The cartridge was subsequently washed with 10 mL NPI-20 washing buffer. Elution buffer of NPI-250 was then applied to elute the scFv from the column. The collections were dialyzed against 1× PBS (pH 7.4) at 4 °C. The concentration of scFv was determined by Bradford protein assay. The purified scFv was stored at −80°C until use. 12% SDS-PAGE was used to confirm the molecular weight of the products.

ZnF16Pc Loading and ScFv Conjugation:

ZnF16Pc was loaded to FRTs as we published before.[33] In brief, the pH of FRT solution (PBS, pH 7.4) was reduced to 2.0 using 1 M HCl. And then ZnF16Pc (5 mg/mL in DMSO) was dropwise added, reaching final w/w ratio (FRT/ZnF16Pc) of 5. After gentle shaking at room temperature (r.t.) for 30 minutes, the pH of the mixture was slowly tuned back to 7.4 using 1 M NaOH. The mixture was gently agitated for another 30 min to ensure reassociation of FRT. The resulting product was purified by NAP-10 column (GE Healthcare, USA) to remove the free ZnF16Pc.

The anti-FAP scFv was coupled onto FRT using bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate (BS3) as a crosslinker. Firstly, ZnF16Pc loaded FRT (Z@FRT, 0.5 mg FRT/mL) was incubated in 4 mM BS3/PBS (pH 7.4) at r.t. for 30 min. The mixture was subsequently subjected to purification by NAP-10 column. The resulting intermediate was mixed with scFv at a molar ratio of 1:20 (FRT:scFv) for 30 min at r.t. A 100k centrifugal filter (Amicon) was used to purify the raw product to yield Z@FRT-scFv.

Isolation of Cancer Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs):

CAFs were isolated from 4T1 s.c. tumor grown on BALB/c mice by magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS).[34] Specifically, fresh 4T1 tumor tissues were washed with ice-cold PBS and minced into 2×2×2 mm3 cubes after removing peripheral and necrotic tissues. A 5-min digestion with 0.25% Trypsin (Corning®, Cat. No. 25-053-CI) was applied to minced tissues at r.t. and then terminated by adding 10% FBS/DMEM. After PBS washing, tumor tissues were subjected to Collagenase IV (0.5 mg/ml in 10% FBS/DMEM) treatment for 1 h at 37 °C. Following PBS wash, tumor tissues were suspended in 10% FBS/DMEM, plated in a petri dish, and cultured in humidified 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 2 days. Fibroblasts would climb out of the tissue block. These tissue blocks were digested and cultured in the same way as CAF enrichment. Finally, remaining tissues were dissociated by Trypsin and all cells were collected for MACS. MACS was performed following the vendor’s protocol, which includes the first step non-CAF depletion and the second step CD90.2+ cell enrichment.

Cell Uptake Studies:

CAF and 4T1 were seeded onto a chamber slide and cultured overnight before incubation with rhodamine labeled αFAP-FRTs (40 μg/mL). After 12-h incubation, αFAP-FRT containing medium was removed and the cells washed with PBS. Cells were further fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X 100/PBS for 15 min at r.t. Cells were then incubated with FITC conjugated anti-α-SMA (Biolegend, USA) overnight at 4 °C. After PBS wash, cells were mounted with DAPI containing mounting medium (Vector, Cat. No. H-1500). Images were obtained under a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope.

MicroPET Imaging:

αFAP-Z@FRTs were conjugated with 1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) using a method published previously.[35] 64Cu labeling and imaging was performed based on reported procedures.[13] In brief, αFAP-Z@FRT-DOTA-64Cu (1 mg αFAP-FRT/kg) was i.v. injected into mice bearing s.c. 4T1 tumor followed by static scans at 1, 5 and 24 h post injection. For the blocking group, 120 μg (6.15 mg/kg) of scFv was injected 1 h prior to αFAP-Z@FRT-DOTA-64Cu administration. The radioactivity uptake in tumors and major organs was calculated based on the PET images and converted to percentage injected dose per gram (%ID/g).

In Vivo Fluorescence Imaging:

Imaging was performed on 4T1 tumor bearing nude mice when tumors reached a size of ~100 mm3. IRDye800-labeled αFAP-Z@FRTs (1 mg αFAP-FRT/kg) were i.v. injected (n = 5) and mice were imaged on Maestro system at 15 min, 1 h, 4 h, and 24 h post injection. For the control group, scFv (6.15 mg/kg) was administrated 2 h prior to the αFAP-Z@FRT injection (n = 5). 24 h later, the animals were euthanized. Tumors as well as major organs were harvested for ex vivo scan.

In Vivo Therapy:

The therapy studies were performed on either single or bilateral 4T1 tumor model. In both scenarios, only tumors on the right-hand side received irradiation. Each group had five animals. For PDT group, animals received two doses of PDT. Specifically, animals were i.v. injected with Z@FRT-scFv (0.5 mg ZnF16Pc/kg) four days after tumor inoculation and the tumors were irradiated at 24 h post injection by a 671 nm laser (300 mW/cm2, over a ~1 cm diameter beam that covered the tumor) for 15 min. The second dose of PDT was given three days later (i.e. 8 days after tumor inoculation). For anti-PD1 group, anti-PD1 antibody (BioXCell, USA) was given every 3 days by i.p. injection at a dose of 10 mg/Kg. A total of three doses were administered on Day 5, 8, and 11 post tumor inoculation respectively. The PDT+anti-PD1 group received the combination of both treatments. The PBS group as control was injected with PBS and received laser irradiation the same way. Tumor volume was measured every other day by a caliper and calculated following the formula: volume (mm3) = length (mm) × width (mm)2/2.

T Cell Depletion:

T cell depletion studies were conducted on single 4T1 tumor model. Anti-CD4 (GK1.5, BioXCell, USA), anti-CD8 (OKT-8, BioXCell, USA), or mouse IgG (C1.18.4, BioXCell, USA) antibodies were i.p. injected into the mice (200 μg/mouse per injection) on Day 5 and 10 post tumor inoculation. Two doses of PDT were given as described above.

Lymphocyte Profiling:

Tumors and lymph nodes were harvested. Cell suspensions were generated through mechanical tissue disruption and collagenase D digestion. Red blood cells were lysed, and samples were filtered through 60 μm nylon filters to obtain single cell suspensions. Cells were stained in PBS with TruStain fcX (BioLegend, Cat. No. 101320) to reduce non-specific antibody binding. Cell samples were then stained with anti-CD3-APC, CD4-FITC, and CD8-PECy5 conjugated antibodies (BioLegend, Cat. No. 100311, 100406, and 100709). After cell surface staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized (Invitrogen, eBioscience Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Kit, Cat. No. 00-5523-00) according to vendor’s protocol. Cells were then stained with anti-FoxP3-PE conjugated antibody. Samples were washed and analyzed with flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter CytoFLEX). Isotype control antibody-stained samples were used as negative staining controls. Flow cytometry data was analyzed using FlowJo Single Cell Analysis Software (Treestar, Inc., Ashland, Oregon) with gating strategies shown in Figure S10–12 (Supporting Information).

Isolation and Cryostorage of Splenocytes:

Freshly harvested spleens were mashed through a sterile cell strainer (Corning, 40 μm) in PBS with a syringe plunger. After PBS wash, cells were pelleted and re-suspended in 1 mL ACK lysis buffer (150 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM Na2-EDTA) per mouse spleen to lyse red blood cells. After 2-min incubation at r.t., splenocytes were washed with PBS, pelleted, and then subjected to IFN-gamma ELISpot assay or cryostorage in 90% FBS/10% DMSO for other assays.

In Vitro Cell-Specific Cytotoxicity Assay:

The cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity was investigated by a modified carboxy-fluorescein succinimidyl ester/propidium iodide (CFSE/PI) cytotoxicity assay.[36] Splenocytes isolated from treated or control mice on Day 12 post tumor inoculation (i.e. 1 week post first PDT session) served as the effector cells after stimulation with CAF and 4T1 debris (CAF and 4T1 frozen and thawed for 5 cycles) in the presence of recombinant mouse IL-2 (rm-IL2, Biolegend, Cat. No. 575402, 30 ng/mL). Specifically, 2.5 × 105 splenocytes in 100 μL medium supplemented with 30 ng/mL rm-IL2 were plated in a low-attachment 96-well plate per well and stimulated with CAF and 4T1 debris (splenocyte:CAF:4T1 = 80:1:1) for 4 days before co-culturing with 5×104 CFSE (Invitrogen, CellTrace, Cat. No. 34554) labeled target cells (4T1 or CAF) for 6 h. PI (Invitrogen, Cat. No. P3566, 2 μg/mL) was added 5 min before analysis on a Beckman cytoflex cytometer. The result was analyzed by FlowJo software. CFSE+PI+ cells were defined as lysed target cells. The percentage of cell lysis was calculated as %cytotoxicity = 100 × (%experimental sample lysis - %basal lysis)/(100 - %basal lysis).

ELISpot Assay:

The number of IFN-γ producing cells in splenocytes was measured using a mouse interferon gamma ELISpot Kit (Abcam, Cat. No. ab64029) following vendor’s protocol. Splenocytes freshly isolated from animals 12 days post tumor inoculation were plated at a density of 2 × 105 per well onto an anti-mouse IFN-γ pre-coated, PVDF bottomed 96-well plate. The splenocytes were incubated with or without 5,000 irradiated (100 Gy) target cells (4T1, CAF, or A549) for 3.5 days. After washing off the cells, biotinylated anti-mouse IFN-γ was added to the plate and was incubated at r.t. for 1.5 h. This was followed by 1-h incubation with Streptavidin-AP conjugate at r.t. Finally, BCIP/NBT buffer was added for spot development. Each purple spot corresponds to an IFN-γ producing cell. The number of spots was counted on a S6 macro ELISpot reader (CTL Analyzers, Shaker Heights, OH). Each sample was tested in duplicates. The number of spots was calculated after subtracting the reading from target cell-free control wells.

Adoptive Cell Transfer:

Non-adherent splenocytes were adoptive transferred to A549 tumor models established on immuno-deficient mice. Cryo-stored splenocytes were thawed and rested for 18 h in 10% FBS/RPMI 1640 in 6-well plates. This helped remove apoptotic cells resulting from cryostorage.[37] Only non-adherent splenocytes were collected after overnight resting. Splenocytes from 5 mice for each treatment group (i.e. PBS, PDT, and PDT+anti-PD1) were pooled and the live cells counted. About 3×106 live splenocytes were intratumorally injected into each A549 tumor-bearing mouse at 4 weeks post tumor inoculation (n = 5).

Histopathological Staining:

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed according to a protocol provided by the vendor (BBC Biochemical). Briefly, 5 μm paraffin-embedded slides were prepared. After being treated with 100% xylene for 3 times (3 min each), the slides were hydrated with serial dilutions of ethanol (100%, 90%, 75%, 50% and 25%, each for 2 min). The hematoxylin staining was then performed for 3 min followed by wash in running water for 3 min. The eosin staining was performed for 1 min. The slides were then washed, dehydrated, treated with xylene, and mounted with Canada balsam. The images were acquired on a Nikon Eclipse 90i microscope.

Trichrome staining kit was purchased from Abcam (Cat. No. ab150686) and the staining was conducted following the vendor’s protocol.

Anti-Ki67 staining was performed following a standard immuno-histochemical staining protocol. After deparaffinization and rehydration, 5-μm paraffin-embedded tumor sections were incubated in 3%H2O2/PBS for 10 min at r.t. and then blocked with 10% normal goat serum/1% BSA/PBS for 1 h at 37 °C. Sections were subsequently stained with anti-Ki67 antibody [SP6] (Abcam, Cat. No. ab16667) overnight at 4°C and goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) (Abcam, Cat. No. ab205718) for 1 h at 37 °C. DAB staining was developed with DAB Substrate Kit (Abcam, Cat. No. ab64238). The slides were finally counterstained with hematoxylin before dehydration and mounted onto a glass slide with Permount Mounting Medium (Electron Microscopy Science, Cat. No. 17986-01). The images were acquired on a Nikon Eclipse 90i microscope. The area of positive staining was analyzed by Image J with five images per tumor.

TUNEL staining was conducted with In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (DAB) (Abcam, Cat. No. ab206386).

Statistical Analysis:

Statistical analysis was performed with Origin software by one-way ANOVA. Statistical significance is indicated as *P< 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Julie Nelson in CTEGD Cytometry Shared Resource Laboratory at University of Georgia (UGA) for help with troubleshooting in flow studies. The authors also appreciate Dr. Ted Ross at Center for Vaccines and Immunology of UGA helping with ELISpot reader. We appreciate the support by the National Science Foundation (CAREER grant no. NSF1552617 to J.X.), and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (grant no. R01EB022596 to J.X.). This work was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award number UL1TR002378. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library.

Contributor Information

Shiyi Zhou, Department of Chemistry, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA.

Zipeng Zhen, Department of Chemistry, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA.

Amy V. Paschall, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Center for Molecular Medicine and Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA

Lijun Xue, Department of Medical Oncology, Jinling Hospital, Nanjing University Clinical School of Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu 210002, China.

Xueyuan Yang, Department of Chemistry, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA.

Anne-Gaelle Bebin-Blackwell, Center for Vaccines and Immunology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30605, USA.

Zhengwei Cao, Department of Chemistry, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA.

Weizhong Zhang, Department of Chemistry, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA.

Mengzhe Wang, Department of Radiology, Biomedical Research Imaging Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Yong Teng, Georgia Cancer Center, Augusta University, Augusta, GA 30912, USA.

Gang Zhou, Georgia Cancer Center, Augusta University, Augusta, GA 30912, USA.

Zibo Li, Department of Radiology, Biomedical Research Imaging Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.

Fikri Y. Avci, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Center for Molecular Medicine and Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA

Wei Tang, Department of Chemistry, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA.

Jin Xie, Department of Chemistry, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA.

References

- [1].Fiori ME, Di Franco S, Villanova L, Bianca P, Stassi G, De Maria R, Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].(a) Fukumura D, Xavier R, Sugiura T, Chen Y, Park E-C, Lu N, Selig M, Nielsen G, Taksir T, Jain RK, Seed B, Cell 1998, 94, 715; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) De Palma M, Biziato D, Petrova TV, Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 457; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Clapéron A, Mergey M, Aoudjehane L, Ho-Bouldoires THN, Wendum D, Prignon A, Merabtene F, Firrincieli D, Desbois-Mouthon C, Scatton O, Conti F, Housset C, Fouassier L, Hepatology 2013, 58, 2001; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Sun Y, Fan X, Zhang Q, Shi X, Xu G, Zou C, Tumor Biol. 2017, 39, 1010428317712592; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Deying W, Feng G, Shumei L, Hui Z, Ming L, Hongqing W, Biosci. Rep. 2017, 37, BSR20160470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].(a) Chen X, Song E, Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2019, 18, 99; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kalluri R, Nature Reviews Cancer 2016, 16, 582; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kobayashi H, Enomoto A, Woods SL, Burt AD, Takahashi M, Worthley DL, Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 282; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tian B, Chen X, Zhang H, Li X, Wang J, Han W, Zhang L-Y, Fu L, Li Y, Nie C, Zhao Y, Tan X, Wang H, Guan X-Y, Hong A, Oncotarget 2017, 8, 42300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hessmann E, Patzak MS, Klein L, Chen N, Kari V, Ramu I, Bapiro TE, Frese KK, Gopinathan A, Richards FM, Jodrell DI, Verbeke C, Li X, Heuchel R, Löhr JM, Johnsen SA, Gress TM, Ellenrieder V, Neesse A, Gut 2018, 67, 497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Xing F, Saidou J, Watabe K, Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2010, 15, 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ostermann E, Garin-Chesa P, Heider KH, Kalat M, Lamche H, Puri C, Kerjaschki D, Rettig WJ, Adolf GR, Clinical Cancer Research 2008, 14, 4584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fang J, Xiao L, Joo K-I, Liu Y, Zhang C, Liu S, Conti PS, Li Z, Wang P, Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].(a) Welt S, Divgi CR, Scott AM, Garin-Chesa P, Finn RD, Graham M, Carswell EA, Cohen A, Larson SM, Old LJ, J. Clin. Oncol. 1994, 12, 1193; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Scott AM, Wiseman G, Welt S, Adjei A, Lee F-T, Hopkins W, Divgi CR, Hanson LH, Mitchell P, Gansen DN, Larson SM, Ingle JN, Hoffman EW, Tanswell P, Ritter G, Cohen LS, Bette P, Arvay L, Amelsberg A, Vlock D, Rettig WJ, Old LJ, Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 1639; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hofheinz RD, al-Batran SE, Hartmann F, Hartung G, Jäger D, Renner C, Tanswell P, Kunz U, Amelsberg A, Kuthan H, Stehle G, Oncol. Res. Treat. 2003, 26, 44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Duperret EK, Trautz A, Ammons D, Perales-Puchalt A, Wise MC, Yan J, Reed C, Weiner DB, Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kakarla S, Chow KK, Mata M, Shaffer DR, Song XT, Wu MF, Liu H, Wang LL, Rowley DR, Pfizenmaier K, Gottschalk S, Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kraman M, Bambrough PJ, Arnold JN, Roberts EW, Magiera L, Jones JO, Gopinathan A, Tuveson DA, Fearon DT, Science 2010, 330, 827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tran E, Chinnasamy D, Yu Z, Morgan RA, Lee C-CR, Restifo NP, Rosenberg SA, J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhen Z, Tang W, Wang M, Zhou S, Wang H, Wu Z, Hao Z, Li Z, Liu L, Xie J, Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gheewala T, Skwor T, Munirathinam G, Oncotarget 2017, 8, 30524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Abbas M, Zou Q, Li S, Yan X, Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1605021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhen Z, Tang W, Chen H, Lin X, Todd T, Wang G, Cowger T, Chen X, Xie J, ACS Nano 2013, 7, 4830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tan T, Wang H, Cao H, Zeng L, Wang Y, Wang Z, Wang J, Li J, Wang S, Zhang Z, Li Y, Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1801012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Li L, Zhou S, Lv N, Zhen Z, Liu T, Gao S, Xie J, Ma Q, Mol. Pharmaceutics 2018, 15, 3595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Monteran L, Erez N, Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].(a) Chang AL, Miska J, Wainwright DA, Dey M, Rivetta CV, Yu D, Kanojia D, Pituch KC, Qiao J, Pytel P, Han Y, Wu M, Zhang L, Horbinski CM, Ahmed AU, Lesniak MS, Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 5671; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Costa A, Kieffer Y, Scholer-Dahirel A, Pelon F, Bourachot B, Cardon M, Sirven P, Magagna I, Fuhrmann L, Bernard C, Bonneau C, Kondratova M, Kuperstein I, Zinovyev A, Givel A-M, Parrini M-C, Soumelis V, Vincent-Salomon A, Mechta-Grigoriou F, Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 463; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kuen J, Darowski D, Kluge T, Majety M, PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0182039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Puré E, Lo A, Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016, 4, 269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pinchuk IV, Saada JI, Beswick EJ, Boya G, Qiu SM, Mifflin RC, Raju GS, Reyes VE, Powell DW, Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].(a) Gieniec KA, Butler LM, Worthley DL, Woods SL, Br. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 293; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Öhlund D, Elyada E, Tuveson D, J. Exp. Med. 2014, 211, 1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].MaHam A, Tang Z, Wu H, Wang J, Lin Y, Small 2009, 5, 1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhen Z, Tang W, Todd T, Xie J, Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 11, 1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].(a) Huang Y, Zhou S, Huang Y, Zheng D, Mao Q, He J, Wang Y, Xue D, Lu X, Yang N, Zhao Y, Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 4825108; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sha M, Jeong S, Qiu B-J, Tong Y, Xia L, Xu N, Zhang J-J, Xia Q, Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 4665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Seidel JA, Otsuka A, Kabashima K, Front. Oncol. 2018, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Reginato E, Wolf P, Hamblin MR, World J Immunol. 2014, 4, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhao L, Liu Y, Chang R, Xing R, Yan X, Adv. Func. Mater. 2019, 29, 1806877. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kratochwil C, Flechsig P, Lindner T, Abderrahim L, Altmann A, Mier W, Adeberg S, Rathke H, Röhrich M, Winter H, Plinkert PK, Marme F, Lang M, Kauczor HU, Jäger D, Debus J, Haberkorn U, Giesel FL, J. Nucl. Med. 2019, 60, 801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lin X, Xie J, Niu G, Zhang F, Gao H, Yang M, Quan Q, Aronova MA, Zhang G, Lee S, Leapman R, Chen X, Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Brocks B, Garin-Chesa P, Behrle E, Park JE, Rettig WJ, Pfizenmaier K, Moosmayer D, Mol. Med. 2001, 7, 461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhen Z, Tang W, Guo C, Chen H, Lin X, Liu G, Fei B, Chen X, Xu B, Xie J, ACS Nano 2013, 7, 6988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Huang Y, Zhou S, Huang Y, Zheng D, Mao Q, He J, Wang Y, Xue D, Lu X, Yang N, Zhao Y, Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 4825108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhou B, Wang H, Liu R, Wang M, Deng H, Giglio BC, Gill PS, Shan H, Li Z, Mol. Pharmaceutics 2015, 12, 3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Chen L, Huang T-G, Meseck M, Mandeli J, Fallon J, Woo SLC, Mol. Ther. 2007, 15, 2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Santos R, Buying A, Sabri N, Yu J, Gringeri A, Bender J, Janetzki S, Pinilla C, Judkowski AV, Cells 2015, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.