Abstract

The complex and highly organized structural arrangement of some five billion cardiomyocytes directs the coordinated electrical activity and mechanical contraction of the human heart. The characteristic transmural change in cardiomyocyte orientation underlies base-to-apex shortening, circumferential shortening, and left ventricular torsion during contraction. Individual cardiomyocytes shorten ∼15% and increase in diameter ∼8%. Remarkably, however, the left ventricular wall thickens by up to 30–40%. To accommodate this, the myocardium must undergo significant structural rearrangement during contraction. At the mesoscale, collections of cardiomyocytes are organized into sheetlets, and sheetlet shear is the fundamental mechanism of rearrangement that produces wall thickening. Herein, we review the histological and physiological studies of myocardial mesostructure that have established the sheetlet shear model of wall thickening. Recent developments in tissue clearing techniques allow for imaging of whole hearts at the cellular scale, whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) can image the myocardium at the mesoscale (100 µm to 1 mm) to resolve cardiomyocyte orientation and organization. Through histology, cardiac diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and other modalities, mesostructural sheetlets have been confirmed in both animal and human hearts. Recent in vivo cardiac DTI methods have measured reorientation of sheetlets during the cardiac cycle. We also examine the role of pathological cardiac remodeling on sheetlet organization and reorientation, and the impact this has on ventricular function and dysfunction. We also review the unresolved mesostructural questions and challenges that may direct future work in the field.

Keywords: cardiac anatomy, diffusion tensor imaging, mechanics, mesostructured, sheetlets

1. INTRODUCTION

The relationship between cardiac ventricular structure and mechanical function has long been recognized as important (1). The orientation of cardiomyocytes changes from the epicardial surface to the endocardial surface in a helical manner, giving rise to the term helix angle (2). Cardiomyocytes are heavily interconnected forming a continuously branching syncytium that contracts in near unison to pump blood efficiently. Cardiomyocyte connectedness is critical for spreading electrochemical signals throughout the heart to elicit coordinated mechanical contraction, and so the syncytial mesh poses a challenge for the integration of proliferating cardiomyocytes (3). The cardiomyocytes are embedded within the myocardial extracellular matrix, which contains a range of proteins that contribute to structural and nonstructural functions (e.g., remodeling and angiogenesis) (4). The structural components (e.g., collagen and elastin) form a scaffold that allows for effective transmission of forces throughout the heart, and also provides structural organization (5).

1.1. Multiscale Structure and Function of the Heart

One of the challenges associated with studying cardiac structure and function is the contribution of features from vastly different structural scales (Fig. 1). At the scale of the whole organ (1–100 mm) clinical imaging with echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or computed tomography (CT) measures: ventricular volumes and wall thickness; functional metrics such as ejection fraction, global longitudinal strain, and torsion; and tissue characteristics (e.g., perfusion and viability). At the cellular scale (10–100 µm) cardiomyocyte shape, cell-to-cell branching, and functional features such as cardiomyocyte shortening, transverse thickening during contraction, and cell-to-cell sliding (i.e., shear) underlie cardiac performance, but are currently difficult to measure in vivo. Between these two scales lies the intermediate mesostructural scale (100 µm to 1 mm) that is characterized by a continuously branching syncytium of cardiomyocytes collected into local sheetlets that is variously described by features such as cardiomyocyte helix angle, sheetlet orientation, sheetlet branching, the pathological fusing of sheetlets and loss of laminar organization, and extracellular matrix remodeling. These features impact sheetlet sliding mechanics, and the rearrangement of cells during contraction. Pathological remodeling also occurs at the ultrascale, with remodeling of cardiomyocyte transverse tubules (6).

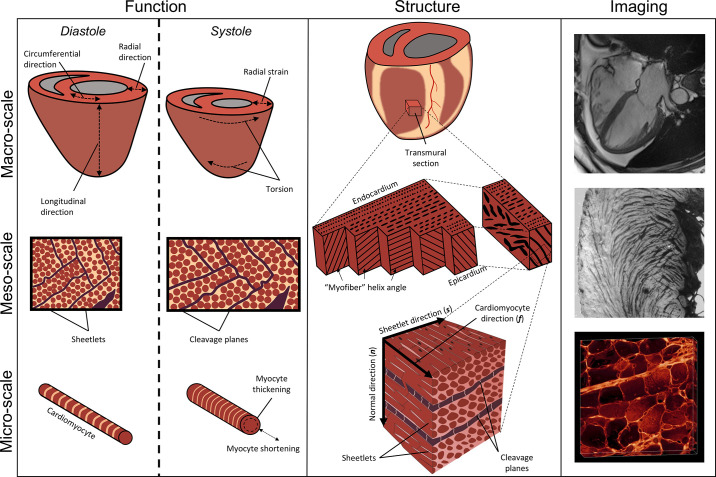

Figure 1.

The multiscale structure and function of the cardiac ventricles. Left column: mechanical function of the whole heart (top) includes ejection fraction, torsion, radial, circumferential, and longitudinal strains. At the mesoscale (middle), mesofunction (middle left) includes transmural shear because of helix angle slope, helix angle reorientation during contraction, and sliding of sheetlets producing wall thickening. At the cellular level (bottom), cardiomyocyte function (bottom left) includes both cellular shortening and transverse thickening. Middle column: structure of the whole heart (top middle) with a transmural tissue block. Myocardial mesostructure (middle) shows the transmural block of myocardium with changing helix angle through the wall, as well as the right block showing cleavage planes giving rise to sheetlets. Microscale structure (bottom middle) shows cardiomyocytes with a cardiomyocyte longitudinal direction (f), which are bundled into sheetlets forming a plane along the both sheetlet (s) and f directions. Orthogonal to the sheetlet plane is the sheetlet-normal direction (n). Right column: real imaging data including a four-chamber cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, top right), a short-axis macrograph showing sheetlet structures across the left ventricular wall (middle right), and cardiomyocyte cross-sections and their organization into sheetlets (bottom right) using extended volume confocal microscopy.

Cardiac mesostructure bridges the cellular and whole organ scales, and is therefore critical for effective cardiac function (7). For instance, measurement of mesostructural features such as aggregate cardiomyocyte direction impact the electromechanical performance of the heart (8), and provide important data for personalized computational models (9). In general, there are many fewer studies at this mesostructural scale as compared with cellular and molecular, or whole organ scales. Cellular-scale experimental methods focus on cardiomyocyte tissue culture, as well as preclinical studies examining the histology of various animal models of cardiac pathology. Organ-scale studies typically measure cardiac structure and function using CT, ultrasound, or MRI. Mesostructural studies are typically performed on ex vivo tissue, although recent developments in MRI push the limits of spatial resolution and microstructural sensitivity, thereby allowing for in vivo measurement of mesostructure (10–15). Within the literature, studies of myocardial mesostructure often lack agreement as to the best imaging and analysis techniques, as well as a standardized way of reporting results. In addition, mesostructural studies can face the problem of registering in vivo and ex vivo image sets or aligning data from different imaging modalities. These deficiencies in describing cardiac mesostructure in turn lead to inadequate computational models of the heart and severely limit their realism. However, this field has considerable opportunity for growth, and new technologies such as tissue clearing, and MRI microscopy are becoming available to study the cardiac mesostructure in unprecedented detail.

1.2. Outline

This review focuses on the mesostructure of the heart, particularly the organization and deformation of aggregate cardiomyocytes and sheetlets through the cardiac cycle, and the contribution of these structures to normal function and pathological dysfunction. Section 2 details our current understanding of ventricular mesostructure, including a review of the orientation and extent of myocardial sheetlets. Section 3 reviews the different imaging modalities able to measure cardiac mesostructure, as well as their advantages and disadvantages. Section 4 reviews the mechanics studies that have linked myocardial sheetlets to ventricular strain. Section 5 examines the changes in myocardial sheetlet structure apparent during pathophysiological remodeling. Section 6 reviews recent developments in clinical translation of diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) that enable the measurement of aggregate cardiomyocyte orientation and sheetlet orientation that, when coupled with MRI methods to measure deformation, provide in vivo insight to the mechanisms of cardiac function and dysfunction. Finally, Section 7 outlines potential future work that would have a high impact on the field of cardiac mesostructure.

2. CARDIAC MESOSTRUCTURE

In this section we 1) introduce the geometric reference frames used for understanding cardiac mesostructure, and the primary terminology, 2) present and summarize the orientation and distribution of cardiomyocytes throughout the heart from a range of animal models (Table 1), and 3) describe the laminar organization of the myocardial sheetlets.

Table 1.

List of anatomic studies measuring aggregate cardiomyocyte and sheetlet orientations

| First Author | Year | Imaging Method | Animal | Sample Size | Helix Angle | Transverse Angle | Sheetlet Elevation | Sheetlet Azimuth | E2A | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angeli | 2014 | DTI, ex vivo | Mouse, C57Bl6 | 5 | ✓ | ✓ | 16 | |||

| Bernus | 2015 | DTI, ex vivo | Rat, Wistar | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 17 | |

| Teh | 2016 | DTI, ex vivo | Rat, Sprague–Dawley | 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 18 | |

| Teh | 2017 | DTI, ex vivo | Rat, Sprague-Dawley | 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 19 | |

| Haliot | 2019 | DTI, ex vivo | Human, elderly | 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 20 | |

| Giannakidis | 2020 | DTI, ex vivo | Rat, WKY | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | 21 | |||

| Giannakidis | 2020 | DTI, ex vivo | Rat, SHR | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | 21 | |||

| Carruth | 2020 | DTI, ex vivo | Rat, Sprague-Dawley | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | 22 | |||

| Carruth | 2020 | DTI, ex vivo | Rat, TAC | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | 22 | |||

| Magat | 2021 | DTI, ex vivo | Sheep | 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 23 | |

| Ferreira | 2014 | DTI, in vivo | Human, healthy | 11 | ✓ | ✓ | 13 | |||

| Ferreira | 2014 | DTI, in vivo | Human, HCM | 11 | ✓ | ✓ | 13 | |||

| Sands | 2008 | EVCM | Rat, Wistar | 1 | ✓ | ✓ | 24 | |||

| Gilbert | 2012 | Histology | Rat, Wistar | 4 | ✓ | 25 | ||||

| Garcia-Canadilla | 2019 | HREM | Mouse, WT | 12 | ✓ | ✓ | 26 | |||

| Garcia-Canadilla | 2019 | HREM | Mouse, Het | 16 | ✓ | ✓ | 26 | |||

| Garcia-Canadilla | 2019 | HREM | Mouse, Hom | 28 | ✓ | ✓ | 26 | |||

| Gilbert | 2012 | HR-MRI, ex vivo | Rat, Wistar | 4 | ✓ | 25 | ||||

| Bernus | 2015 | HR-MRI, ex vivo | Rat, Wistar | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 17 | |

| Haliot | 2019 | HR-MRI, ex vivo | Human, Elderly | 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 20 | |

| Magat | 2021 | HR-MRI, ex vivo | Sheep | 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 23 | |

| Teh | 2017 | PB-X-PCI | Rat, Sprague–Dawley | 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 19 |

Mesostructural data have been measured from a range of human and animal hearts using various imaging modalities. DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; E2A, secondary eigenvector angle; EVCM, extended volume confocal microscopy; HCM, human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; het and hom, Mybpc3-targeted knockout heterozygous mice and homozygous mice, respectively; HREM, high-resolution episcopic microscopy; HR-MRI, high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging; PB-X-PCI, synchrotron propagation-based X-ray phase contrast imaging; SHR, spontaneously hypertensive rat; TAC, transverse aortic constriction; WKY, Wistar-Kyoto; WT, wild-type mice.

The literature is full of discussions describing and debating the correct anatomical description, or model, of the heart. For an in-depth review of the various cardiac structural models we point the reader to the excellent reviews by Gilbert et al. (28) and Anderson et al. (29). In this review, we will focus on the laminar organization of myocardial sheetlets, which has been the predominant mesostructural model adopted by studies in this journal (25, 27, 30–39).

Cardiomyocytes form a continuously branching syncytium. As such, the term “myofiber,” which has previously been borrowed from skeletal muscle anatomy, is not suitable for describing the myocardium. We use the term aggregate cardiomyocyte to indicate properties of a collection of cardiomyocytes within an imaging voxel. For instance, the primary eigenvector of the diffusion tensor indicates the aggregate cardiomyocyte direction within an MRI imaging voxel (often 0.5–2 mm in size).

2.1. Coordinate Systems and Angles

Systematically describing ventricular mesostructure requires the definition of coordinate systems and angles (Fig. 2). The “cardiac coordinate system” is most widely defined according to the left ventricular geometry with circumferential, longitudinal, and radial directions (Fig. 3). The longitudinal axis is defined as a line passing through the left ventricular apex of the heart, as well as through the commissure between the left and right coronary cusps of the aortic valve (40). In the short-axis plane (the plane orthogonal to the longitudinal axis), the radial (or transmural) direction extends from the center of the left ventricular cavity to the epicardial surface, and the circumferential direction follows the curve of the epicardial surface and is orthogonal to the radial and longitudinal directions.

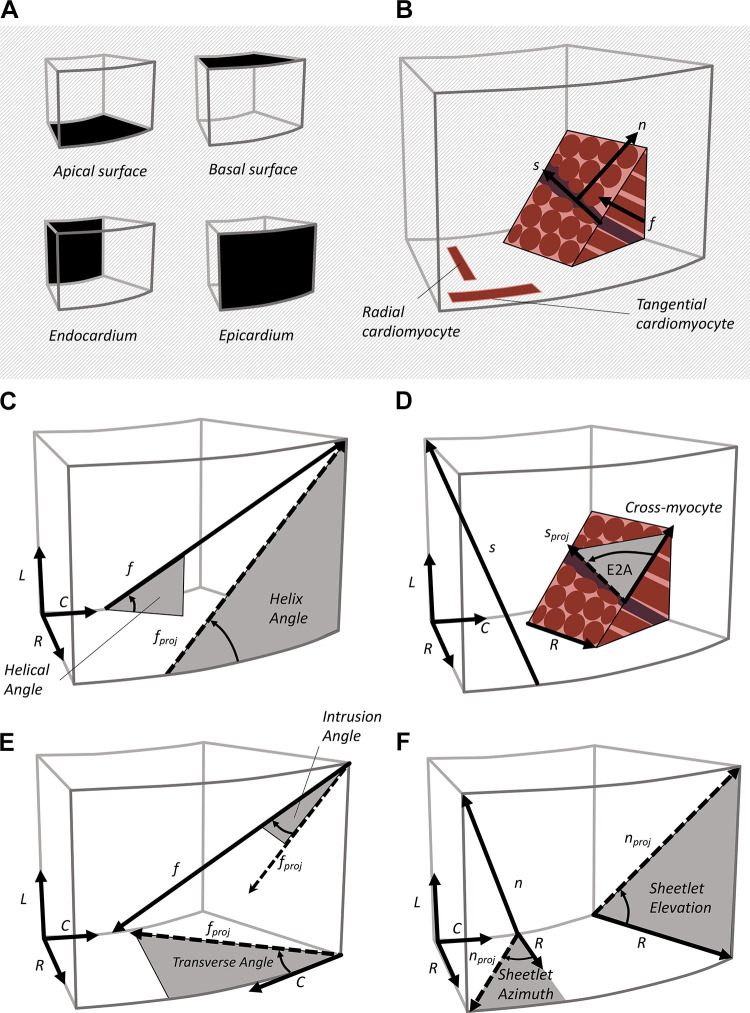

Figure 2.

Mesostructural coordinates and angles. From a reference tissue block (A), the myocardium can be defined by three orthogonal directions (B), the aggregate cardiomyocyte (f), sheetlet (s), and sheetlet-normal (n) directions. Helix angle (C) is the projection of the f onto the longitudinal-circumferential plane. Secondary eigenvector angle (E2A; D) is the projection of the sheetlet direction s onto the cross-myocyte plane. The transverse angle (E) is the projection of f onto the short axis plane (radial-circumferential plane). Sheetlet elevation and sheetlet azimuth (F) are projections of the n onto the longitudinal-radial plane and the short-axis plane, respectively.

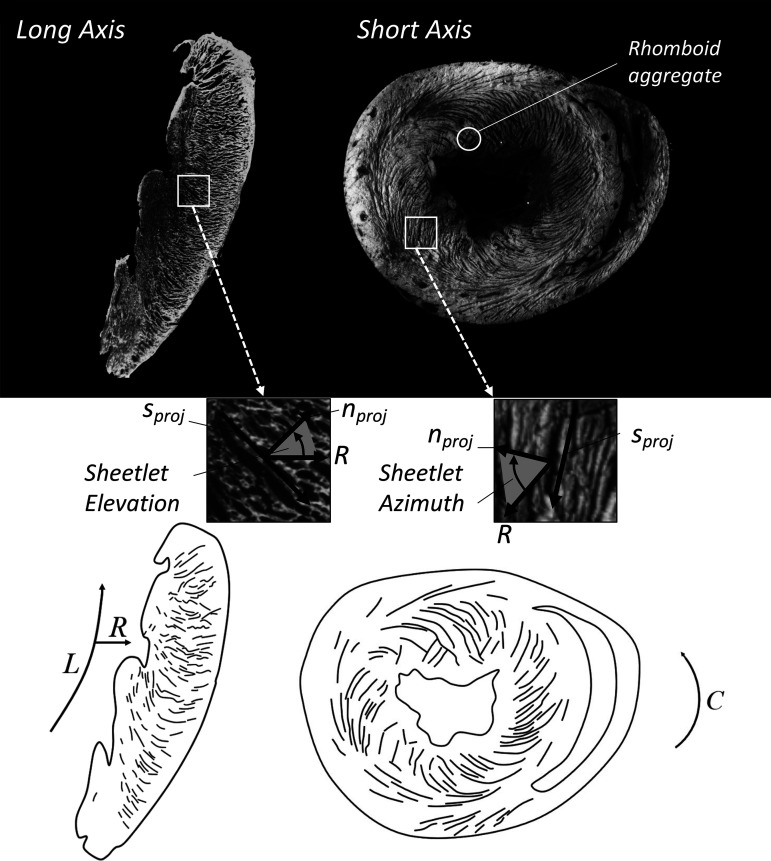

Figure 3.

Sheetlet structures imaged in cardiac long-axis (left) and short-axis (right) views. The macrographs (top) show light myocardium with dark cleavage planes, and schematic representations are also presented (bottom). Sheetlet elevation (middle left) is shown as the angle between the radial direction (R) and the projection of the sheetlet-normal direction (nproj) on the long-axis plane. Sheetlet azimuth (middle right) is shown as the angle between R and nproj on the short-axis plane. The long-axis view shows cleavage planes extending in a radial pattern toward the epicardium, with local connections as opposed to a full transmural span. In the short-axis view, cleavage planes have a herringbone or V-shaped structure, with structural discontinuities located approximately in the midwall. Intersecting populations of sheetlets are most visible in the subendocardial surface of the short-axis macrograph (top right).

Cardiomyocyte and sheetlet orientations are reported using the “myocardial coordinate system” (Fig. 1, microstructure) defined by the cardiomyocyte longitudinal direction (f), sheetlet (s) direction, and sheetlet-normal direction (n). For many use cases, such as computational modeling, these directions are assumed to be orthogonal, although there is no underlying anatomical reason for these directions to be strictly orthogonal. Various mesostructural angles relate the myocardial coordinate system to the cardiac coordinate system (Fig. 2). The helix angle is the degree to which cardiomyocytes are angled out of the short-axis plane measured either using a projection of f onto the tangential plane (helix angle) or without projection (helical angle, Fig. 2C). The transverse angle is the degree to which cardiomyocytes are angled with respect to the circumferential direction, measured either projecting f onto the short-axis plane (transverse angle), or measured without projection (intrusion angle, Fig. 2E). Sheetlet orientation can be described with the elevation of n with respect to the short-axis plane (sheetlet elevation) or angled with respect to the radial direction (sheetlet azimuth, Fig. 2F). Sheetlet orientation can also be described using the projection of the s onto the cross-fiber plane (secondary eigenvector angle, E2A, Fig. 2D). See glossary of terms.

2.2. Cardiomyocyte Orientation

The orientation of the cardiomyocytes throughout the heart is important for two principal reasons. First, the principal cardiomyocyte direction indicates the principal direction of mechanical force produced by shortening of cardiomyocytes. Second, the cardiomyocyte direction indicates the principal direction of the electrochemical action potential spreading throughout the heart.

2.2.1. Helix angle.

When examined through the left ventricle, cardiomyocyte orientation changes as a function of depth (40, 41). The transmural trend of this orientation is helical in nature, giving rise to the term “helix angle” (2). Curiously, this means that mechanical shortening of cardiomyocytes has different orientations at different transmural locations. At first this seems to be counterintuitive, as cardiomyocytes appear to be working in competition rather than cooperatively. However, longitudinally oriented cardiomyocytes are needed to produce >50% ejection fraction from the ∼15% cardiomyocyte contraction (42), thus the variable direction of principal shortening produces effective contraction at the organ level. In addition, the epicardial and endocardial cardiomyocytes form opposing spirals, contributing to efficient ejection (43). The differing orientation of epicardial and endocardial cardiomyocytes, combined with their radial position gives rise to tissue shear and ventricular torsion (44).

Key metrics for describing helix angle include the helix angle range (180° if cardiomyocyte orientation is −90° at the epicardium and +90° at the endocardium), as well as the transmural helix angle trend, which can be linear [Fig. 3 in Pope et al. (5)] or tangent [Fig. 4 in Streeter et al. (41)] among others. By convention the epicardial cardiomyocytes have a negative helix angle, whereas the endocardial cardiomyocytes have a positive helix angle. A range of studies have reported helix angle range and trend across a number of animal models, and in general small animal hearts have a larger helix angle range compared with large animal and human hearts (45). Anatomic studies of porcine hearts show helix angles of approximately −90° at the epicardium to +90° at the endocardium with roughly a linear trend (40). However, studies in dog hearts show a helix angle trend similar to a tangent function (41), with a rapid transition from longitudinally oriented cardiomyocytes toward circumferentially oriented cardiomyocytes.

Effective contraction of the heart at the organ level requires a combination of circumferential and longitudinal shortening, radial thickening, and ventricular torsion. It is therefore likely that the transmural trend, and the frequency distribution of helix angles is important to normal heart function. Different transmural helix angle distributions have been observed between healthy and diseased hearts, between different animal models, across different regions of the heart, and between different imaging modalities. Transmural trends can be represented with helix angle frequency histograms: a tangent-type transmural trend produces a Gaussian-type frequency histogram, with a linear transmural trend producing a uniform frequency histogram.

Helix angle measurements show discrepancy between imaging methods, even within the same animal strain. For example, helix angle has been measured in the Wistar-Kyoto rat using both propagation-based X-ray phase contrast imaging (PB-X-PCI, Section 3.3) and DTI (21, 46). Helix angle as measured by PB-X-PCI had a helix angle range of ∼125° (epi = −50°, endo = +75°, linear trend), whereas the DTI study measured a helix angle of ∼180° (epi = −90°, endo = +90°). When these two studies are compared, DTI overestimated helix angle range (∼55°) as compared with PB-X-PCI. Within Sprague–Dawley rat hearts, helix angle has been measured using both PB-X-PCI and DTI (19). In this study, PB-X-PCI slightly overestimated the transmural helix angle range (12°) as compared with DTI. There are likely several factors contributing to these differences including sample preparation and fixation, the time to imaging, the sample mounting medium or imaging solution, imaging parameters, image reconstruction workflow, and structure tensor processing parameters.

2.2.2. Transverse angle.

Within the literature less attention has been given to the cardiomyocyte transverse angle, which is the degree to which cardiomyocytes lie within, or deviate from the epicardial tangential plane (Fig. 2B). In terms of the organ-level contraction of the heart, cardiomyocytes that are oriented within the tangent plane (circumferentially rather than radially) contribute to both longitudinal and circumferential shortening, whereas cardiomyocyte cross-fiber thickening contributes to positive radial strain. However, a subpopulation of cardiomyocytes have been identified with a partial radial orientation, with some angles up to 45° with respect to the tangential plane (47). Histological findings of the subendocardium show that the transverse angle has a Gaussian distribution centered on 30° (48). However, the presence of transverse cardiomyocytes was also investigated using extended volume confocal microscopy, and cardiomyocyte transverse angle was found to be uniformly zero across the left ventricular (LV) free wall (24). In a functional study by Lunkenheimer et al. (49), force probes measured the contraction through the cardiac cycle of transverse cardiomyocytes as well as tangential cardiomyocytes. Transverse cardiomyocytes were found to have a different force profile as compared with tangential cardiomyocytes and proposed as a mechanism to limit ventricular compliance during diastole. To our knowledge, no other groups have confirmed this finding and it remains in need of further investigation.

Further evidence in wild-type mice found a change of transverse angle from positive at the base to negative at the apex (26). Transversely oriented cardiomyocytes may explain why ECR shear varies longitudinally, from positive at the apex to negative at the base (50). In addition, mechanics simulation of the heart show that the inclusion of transverse angle is critical for correct estimates of ECR, with a transverse angle of 25° providing the best match between experimental data and simulation (51). In the absence of transverse cardiomyocytes, contraction of subendocardial cardiomyocytes produces a greater ECR than is observed, suggesting that transverse cardiomyocytes contribute to the equilibrium of ECR. There is a clear lack of research looking into the presence, importance, and functional contribution of cardiomyocytes with a large transverse angle. Studies that independently confirm the findings of Lunkenheimer et al. (49) would perhaps lead to more widespread appreciation of the importance of cardiomyocyte transverse angle (52), and its incorporation into biomechanical models of the heart.

2.3. Myocardial Sheetlet Mesostructure

At the mesoscale, cardiomyocytes are bundled into sheetlets of three to six cells in thickness, giving rise to a layered or “laminar” structure (27). This structural organization was documented, although perhaps not fully appreciated, by those studying the hierarchical collagen structure of the myocardium (53), who noted a collagen meshwork surrounding groups of cardiomyocytes ∼4 cells in thickness. Although there are limited data on sheetlet thickness, both canine (27) and rodent hearts (33) exhibit a sheetlet thickness of ∼4 cells, suggesting a degree of conservation across species.

Sheetlets are not independent entities, as they branch and interconnect with one another at the mesoscale, via connections termed “muscle bridges” (54). The early description by LeGrice et al. was later incorrectly interpreted as proposing sheetlet layers that span the full ventricular wall without interconnection. Such an organization may however lead to gross separation during filling. Along the sheetlet direction, sheetlets span ∼250 µm, or ∼15 cells (5) before they encounter structural features such as fusing with adjacent sheetlets, branching into two sheetlets, or abutments with sheetlets of a different orientation. Cardiomyocytes with a nonzero transverse angle (Section 2.2.2) would cross between sheetlet structures, and therefore the presence of such cardiomyocytes would provide additional sheetlet connectivity. These structural branches and muscle bridges provide additional structural integrity to the myocardium. In addition, extracellular matrix collagen provides mechanical integrity within sheetlets and couples adjacent sheetlets. Within sheetlets cardiomyocytes are surrounded by endomysial collagen (33), and within cleavage planes perimysial collagen strands connect adjacent sheetlets (5).

The regional orientation of sheetlets was first systematically described in the dog heart by LeGrice et al. (27). The sheetlet orientation can be examined in macroscopic long-axis views of the heart (Fig. 3). These follow a general radial pattern: at the apex, the cleavage planes (projected sheetlet direction) point toward the apex, whereas at the equatorial region cleavage planes align roughly with the short-axis plane, and at the basal region, cleavage planes are elevated above the short-axis plane. These results are consistent with more recent measurements of sheetlets elevation using DTI and high-resolution T1-weighted imaging (18, 23), which show a sheetlet elevation of ∼45° at the apex, ∼0° at the equator, and ∼−45° at the base.

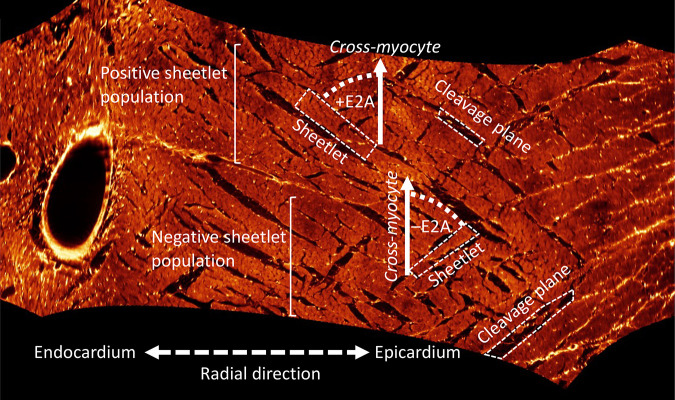

However, sheetlet elevation alone does not capture the complex arrangement of sheetlets through the transmural span. Three-dimensional (3D) imaging techniques are therefore preferred, as the image volume can be resectioned transverse to the cardiomyocyte long-axis at all transmural locations (5, 24). Virtual resectioning of a transmural LV section allows measurement of E2A, and revealed two populations of sheetlets (24). The positive sheetlet population had an E2A centered on +60° in the subepicardium and midwall, and +30° in the subendocardium. The negative sheetlet population was centered at −30° through the transmural span, although most clearly defined in the midwall. Imaging of the left ventricle using DTI reveals a bimodal distribution of E2A, with the two populations of sheetlets: one at +30° and one at −30° (55).

The sheetlet azimuth is the angle between the radial direction and the projection of the sheet-normal vector onto the short-axis plane (Fig. 2F). Sheetlet azimuth has an absolute value range of ∼20° from epicardium to endocardium, which is small relative to helix angle (18). In general, the frequency distribution of sheetlet azimuth is Gaussian and centered on zero (18). In the basal anterior, anteroseptal, inferoseptal, and midanterior segments, there is a small increase in sheetlet azimuth angle in the subendocardium. The basal inferolateral and mid inferolateral segments have a larger subepicardial increase in sheetlet azimuth.

2.4. Orthogonal Sheetlet Populations

LeGrice et al. (27) noted that in various regions of the heart the laminar structure did not follow a single stack, but rather there were two populations of sheetlets. The orientation of cleavage planes display discontinuities, producing herringbone patterns that are present in long-axis microscopy (Fig. 3) of the right ventricle (RV) and LV (56). These are also revealed using extended volume confocal microscopy (57). In addition, the intersecting populations of sheetlets can produce parallelogram or rhomboid-type aggregates of cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3) (58).

Because of the presence of two sheetlet populations (Fig. 4), sheetlet orientation is not necessarily conserved across different individuals of the same species (30, 32, 59). During systole, the myocardium has two principal orientations of maximum shear, and the sheetlet orientations align with these two shear directions (30). Comparing two hearts directly can reveal conflicting sheetlet orientations, as individual hearts favor one predominant sheetlet population over the other (59). Once sheetlet orientations from multiple hearts are pooled, a consistent bimodal distribution emerges that indicates the presence of two sheetlet populations.

Figure 4.

Orthogonal sheetlet populations. Imaging of the myocardium using extended volume confocal microscopy allows for a virtual cut that shows the cross-myocyte plane at all locations. In the midwall, two populations of sheetlets are revealed, one with a positive sheetlet angle (secondary eigenvector angle, +E2A), and one with a negative sheetlet angle (–E2A).

It is still not clear the extent to which processing of myocardial tissue opens sheetlet cleavage planes, and whether one sheetlet population over the other is preferentially opened through this processing. Sheetlet cleavage planes have been demonstrated via high-resolution MRI to be present without histological processing (17). However, within a single myocardial tissue sample, imaging of consecutive histology sections can reveal a single sheetlet population in one section, but two intersecting sheetlet populations in the next section (60). In addition, DTI reveals no signal differences in tissue which, histologically, show one sheetlet population compared with those containing two sheetlet populations. It is possible that even in regions where only one sheetlet population is visible using histology, two sheetlet populations are present in the unprocessed tissue (60). Histology processing may in some cases only render visible one sheetlet population, even if two are present.

Trying to capture information regarding hundreds of cardiomyocytes arranged into potentially two orthogonal sheetlet populations using DTI is not a straightforward task. Different sheetlet populations within a voxel may cancel out diffusion signal along the s and n directions, giving rise to nonphysiological data. A voxel containing two sheetlet populations should theoretically produce an E2A that is almost parallel with the tangential plane (13). However, in vivo measurement of human hearts revealed an E2A that is oblique with regard to the tangential plane, which is consistent with a single predominant sheetlet population within a voxel (13). Recent advances in diffusion MRI encoding may provide more insight to intravoxel sheetlet organization.

3. IMAGING OF CARDIAC MESOSTRUCTURE

In this section, we review the imaging methods that have been developed to measure cardiac mesostructure. These include diffusion tensor imaging (Section 3.1), magnetic resonance microscopy (Section 3.2), micro-computed tomography (Section 3.3), tissue clearing techniques for histology (Section 3.4), serial block-face histology (Section 3.5), ultrasound techniques (Section 3.6), and optical coherence tomography (Section 3.7). The imaging methods used to measure cardiac mesostructure are intrinsically linked with our understanding of it, and a longstanding goal in the field has been to measure both cardiac mesostructure and myocardial deformation through the cardiac cycle (61). Of these, the ultrasound techniques (Section 3.6), as well as in vivo cardiac DTI techniques (Section 6) are the methods that are closest to achieving this.

3.1. Diffusion Tensor Imaging

Diffusion tensor imaging measures the Brownian diffusion of water along many directions. Cellular structures restrict diffusion along certain directions, thereby providing information about the intravoxel tissue microenvironment (62). DTI is used to probe diffusion lengths on the order of tens of microns, roughly the radius of a cardiomyocyte. DTI uses specialized MRI pulse sequences that include waveforms (i.e., modules) called diffusion gradients. When water diffuses along the direction of the applied diffusion gradient, the result is incomplete spin rephasing, and net signal loss (attenuation). An image without the applied diffusion gradients (termed the b0 image) is also acquired, and this b0 image provides a reference for measuring signal loss and the amount of diffusion along each gradient direction. The effective magnitude of the applied diffusion gradient is summarized by the waveform’s b-value with units of s/mm2 (reciprocal to the units of diffusion, mm2/s). As each acquisition only measures diffusion along a single direction, multiple directions are acquired to measure the diffusion in three dimensions. At least six directions are needed to reconstruct the intravoxel diffusion tensor. Eigen decomposition of the diffusion data provides the primary, secondary, and tertiary eigenvectors, which correspond with the directions of greatest, next-greatest, and least diffusion, respectively.

To validate DTI as a tool for measuring cardiac mesostructure, previous studies have imaged the heart using DTI, subsequently imaged the myocardium using microscopy (the current reference standard for imaging myocardial mesostructure), registered the image data from the two methods, and compared the agreement of the mesostructural features. The DTI primary eigenvector (direction of greatest diffusion of water) has been shown to align with the aggregate cardiomyocyte direction (63–65). In addition, the DTI secondary eigenvector (direction of next-greatest diffusion) has been shown to align with the sheetlet direction (66, 67), and the tertiary eigenvector (direction of least diffusion) with the sheetlet-normal direction (60).

The invariants of the diffusion tensor have been used to estimate general microstructural features within a voxel. The two most reported measures are the fractional anisotropy, and the mean diffusivity (also known as the apparent diffusion coefficient). The fractional anisotropy indicates degree of anisotropy of the diffusion, and a low fractional anisotropy has been shown to correspond with intravoxel dispersion of cardiomyocyte direction, as measured by histology (68). A high mean diffusivity is correlated with an expanded extracellular volume (69), as is present in tissue with fibrosis.

3.2. Magnetic Resonance Microscopy

High-resolution T1-weighted imaging sequences are able to resolve sheetlet mesostructure in ex vivo rat hearts using ultra high-field MRI (imaging time ∼24 h) (17, 25). One advantage of using high-resolution T1 weighted imaging to validate DTI with myocardial mesostructure is that samples can also be scanned with both MRI sequences without moving the sample. The T1-weighted images can be processed using a structure tensor approach, with eigenvectors defined according to spatial gradients in image contrast. This processing allows a direct comparison between anatomic structure tensors and diffusion tensors. Measurements of f and n from both DTI and anatomic structure tensors have been compared in detail (17, 20, 23). The two measurements of f show excellent alignment. Although n shows good agreement on average, some regions had a difference of up to 60° between the two methods. The failure of the DTI n to completely describe the structure tensor n may be due to eigenvalue sorting problems (Section 6.4), or the presence of multiple sheetlet populations within a DTI voxel. Currently, it is clear that more studies are needed to characterize the correspondence of the structure tensor and DTI-based estimates of mesostructure with those measured by histology.

3.3. Micro-Computed Tomography

Micro-CT uses X-rays to image a sample from multiple orientations, allowing reconstruction of 3-D image volumes. Imaging that relies upon X-ray absorption does not produce good contrast in cardiac tissue, as X-ray absorption in the heart is low relative to tissues such as bone. As such, metal-based stains such as iodine can be used to increase contrast in myocardial specimens. Alternatively, contrast in unstained tissue can be boosted by acquiring phase-shift measurements (X-ray phase contrast imaging X-PCI), and this technique has been used in mouse hearts (70), and in human hearts (58, 71). Micro-CT also allows some flexibility of preparation, samples can be imaged in paraffin, ethanol, or in air after solvent evaporation.

The signal-to-noise ratio of X-ray micro CT can be further improved through the use of high-intensity synchrotron-generated X-ray beams. As such, synchrotron radiation-based X-PCI has been used to image whole rabbit hearts (72) (imaging time ∼1 h), and small blocks of human myocardium (58). Such imaging methods are already revealing novel mesostructural features of the myocardium. For example, the orientation of myocytes within sheetlets have been shown to oscillate, a mesostructural feature that may contribute to sheetlet shear (58).

3.4. Tissue Clearing

Through a combination of lipid removal and refractive index matching, tissue clearing techniques prepare samples for microscopy and allow for imaging deep into thick tissue samples (hundreds of microns) (73). Tissue clearing is particularly useful for producing high-resolution microscopy image volumes, which are requisite for measurement of cardiac mesostructure. Tissue clearing methods are divided into hydrophobic and hydrophilic categories, each with their advantages and disadvantages. For detailed information regarding tissue clearing methods as applied to the heart, we refer the reader to a review by Sands et al. (73).

Light-sheet microscopy is particularly useful for imaging of cleared specimens. The method uses a focused plane of light to selectively illuminate a section of tissue (∼5 μm in thickness). The illumination plane is scanned across the whole sample, allowing whole rodent hearts to be imaged in ∼30 min. Tissue clearing has a range of applications. In cardiac research, clearing allows measurement of cardiomyocyte disarray in human myocardial samples (74), it has been combined with transcriptomics to identify cell types within the cardiac conduction system at single-cell resolution (75), and light-sheet imaging has been used to perform cine imaging in zebrafish hearts (76). This emerging method will likely play a very important role in further characterizing the mesostructure of the heart.

3.5. Serial Block-Face Imaging

Serial block-face imaging is another technique that allows for 3-D imaging of ex vivo hearts. After excision, hearts are fixed, stained, and embedded in preparation for a series of imaging and milling cycles. Depending upon the sample type and preparation technique, confocal microscopy can achieve imaging depths of tens of microns per imaging cycle. Embedded samples are mounted on a stage that allows both imaging and milling of the top surface. The top of the sample is imaged, and then milled to expose the next layer of tissue for imaging. The cycle of milling and imaging is continued until a volume of tissue has been imaged.

Extended volume confocal microscopy has been extensively applied to the heart, and has been used to describe the myocardial collagen structure in transmural sections of the left ventricle at resolutions less than 1 μm (5, 24, 33, 57, 77). Other methods such as high-resolution episcopic microscopy have been used to assess the mesostructure of whole mouse hearts, and have in-plane resolutions of ∼30 μm (26).

3.6. Ultrasound Techniques

Ultrasonic backscatter tensor imaging is an ultrasound technique that allows for in vivo measurement of cardiac mesostructure (78, 79). Multiple tilted plane waves are emitted, and a two-dimensional (2-D) receiver array receives the backscattered echoes. During image reconstruction, coherent compounding is used to generate a tensor for each voxel, which is used to measure aggregate cardiomyocyte orientation. This technique reveals changes in aggregate cardiomyocyte orientation through the cardiac cycle, and has interesting clinical potential.

Another technique, echocardiographic shear wave imaging, uses ultrasound shear waves that propagate more quickly along the cardiomyocyte direction than in the cross-myocyte direction. This imaging technique uses a linear array ultrasound probe, which is rotated through 180° in 5° increments. This process generates plane shear waves that propagate in a range of directions, allowing the aggregate cardiomyocyte orientation to be estimated (80). The technique is able to reproduce the expected change in helix angle across the left ventricular wall.

3.7. Optical Coherence Tomography

Optical coherence tomography uses high-intensity light to penetrate tissue, and measures structure from the backscattered light. The technique is able to provide 3-D image volumes with a voxel size of <100 μm, with a penetration of several centimeters into tissue. Optical coherence tomography has been shown to be able to measure aggregate cardiomyocyte orientation (81, 82). Optical polarization tomography is a variant of optical coherence tomography that has an improved resolution and signal-to-noise ratio, allowing for tractography analysis. Measurements of f using this technique have been shown to agree with histology measurements (83).

4. MESOFUNCTION: SHEETLET SLIDING AS THE MECHANISM OF VENTRICULAR WALL THICKENING

This section will review myocardial mechanics at the mesoscale (mesofunction), with a focus on the sheetlet sliding model of wall thickening, and the evidence supporting sheetlet sliding as the primary mechanism of ventricular wall thickening. Section 4.1 defines the whole organ cardiac strains as well as the mesostructural tissue strains. Section 4.2 covers the mechanics studies that link cardiac and mesostructural strain with sheetlet mesostructure (Table 2), and the role of multiple sheetlet populations in cardiac mesofunction. Finally, in Section 4.3 we review the passive mechanics of the orthotropic myocardium.

Table 2.

Reference functional studies linking myocardial strain and mesostructure

| First Author | Year | Methods | Animal | Sample Size | Key Finding | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waldman | 1988 | Cine X-ray | Canine | 7 | The principal direction of deformation is orthogonal to the fiber direction, and therefore significant rearrangement of cardiomyocytes is required for ventricular wall thickening. | 86 |

| LeGrice | 1995 | Cine X-ray, macro videography | Canine | 10 | Sheetlet shearing aligns with maximum strain vectors in the subendocardium. | 84 |

| Costa | 1999 | Cine X-ray, macro videography | Canine | 6 | Regional differences in wall thickening reflect underlying differences in sheetlet orientation. | 32 |

| Arts | 2001 | Mathematical model | Canine (Costa) | 6 | Sheetlets align with planes of maximum shear - two solutions exist, giving rise to the two populations of sheetlets. | 30 |

| Dokos | 2002 | Shear testing | Porcine | 6 | Shear modes align with sheetlet structures (NF/NS) that are the most compliant. | 31 |

| Ashikaga | 2004 | Cine X-ray, histology | Canine | 5 | During early diastole, sheetlet strain decreases rapidly. | 36 |

| Chen | 2005 | DTI ex vivo, histology | Rat, Sprague-Dawley | 21 | Hearts fixed in systolic and diastolic states showed reorientation of sheetlets. | 35 |

| Sommer | 2015 | Shear testing | Human | 28 | Shear modes align with sheetlet structures (NF/NS) that are the most compliant. | 85 |

| Li | 2020 | Shear testing | Ovine | 5 | Further confirmation of the orthotropic myocardial material properties. | 87 |

NF, normal-myocyte; NS, normal-sheet.

4.1. Cardiac Strain and Myocardial Strain

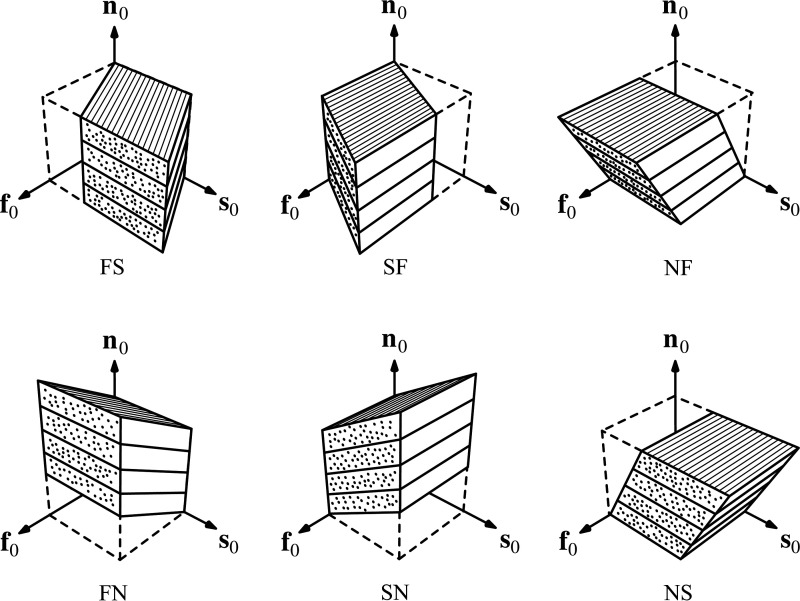

In the cardiac coordinate system, the three axial strains are: ECC circumferential strain, ELL longitudinal strain, and ERR radial strain. During systole, shortening occurs along C and L directions, and therefore ECC and ELL are negative. R expands during systole, with ERR typically having a positive value. There are also three shear strains, the most well known is the ECL circumferential-longitudinal shear strain, also known as ventricular torsion. Additional shear strains include ELR longitudinal-radial shear strain and ECR circumferential-radial shear strain. At the mesoscale, there are three mesofunction strains: Eff aggregate cardiomyocyte strain, Ess sheetlet strain, and Enn normal strain. The six mesofunction shear strains (Fig. 5) are: myocyte sheet (Efs), sheet myocyte (Esf), normal myocyte (Enf), myocyte normal (Efn), sheet normal (Esn), and normal sheet (Ens).

Figure 5.

Six modes of mesoscale shear strain. From an initial cube state, shear deformation in the form of myocyte-sheet (FS), sheet-myocyte (SF), normal-myocyte (NF), myocyte-sheet (FN), sheet-normal (SN), and normal-sheet (NS) modes are applied. Because of the laminar mesostructure of the myocardium, the different shear modes result in different shear stiffness measurements. In particular, the NF and NS shear modes have reduced shear stiffness compared with the FS, FN, SF, and SN modes. This provides evidence that sliding of sheetlets facilitates myocardial deformation. Reproduced with permission from Sommer et al. (85).

4.2. Sheetlet Mechanics Studies

Early studies matched cardiac-level strains with mesofunction by injecting columns of radio-opaque beads into the myocardium, which were imaged using cine radiography (86). By tracking the locations of these beads throughout the cardiac cycle, mesoscale strain was calculated. The principal direction of tissue deformation was observed to be orthogonal to the cardiomyocyte direction. Since cardiomyocytes only increase in diameter by ∼8% during peak contraction, it was concluded that significant mesostructural rearrangement of the myocardial tissue must occur to produce normal systolic wall thickening that exceeds 25% (86).

LeGrice et al. (84) made use of the same methodology, with the additional detail of histological measurement of cardiomyocyte and sheetlet orientations in the myocardium containing the beads. They found that the mesoscale strains aligned with shearing of the sheetlets, and proposed the sheetlet sliding model (Fig. 1, mesofunction). This model purports that the sliding of sheetlets relative to one another can account for up to 40% radial strain.

There are three components of wall thickening that arise from the sheetlets—1) sliding of sheetlets relative to one another (i.e., mesostructural shear), 2) the reorientation or tilting of sheetlets, measured by changes in E2A, sheetlet elevation, and sheetlet azimuth, and 3) sheet thickening resulting from the thickening of constituent cardiomyocytes.

The involvement of sheetlet reorientation was further supported through measurements by Chen et al. They measured sheetlet orientations in both systole and diastole using both DTI and histology, and confirmed that sheetlets change their orientation between different phases of the cardiac cycle (35). In addition, Ashikaga et al. (38) found significant sheetlet strain during early diastole, supporting the idea that recoiling of sheetlets is an important component of early diastolic filling. The organization of sheetlets allow for mesoscale shear: a resolution of forces produced from contracting cardiomyocytes both within and adjacent to a given sheetlet region (13). DTI studies have demonstrated that sheetlets reorient during the cardiac cycle—measured as E2A mobility (12). Although some studies show negligible helix angle reorientation (12) others show evidence of helix angle changes during systole (10, 48, 49, 88). Refer to Section 5.3 for further discussion of E2A mobility in diseased hearts.

Another feature of the myocardial mesostructure complicating the model of sheetlet sliding is the multiple populations of sheetlets. Sheetlet populations tend to be oriented approximately orthogonal to one another, and produce a herringbone mesostructure of intersecting layers. This herringbone mesostructure deforms in a similar manner to an accordion (Fig. 1, mesofunction), and allows for mesoscale shear without the need for transmural shearing of epicardial and endocardial surfaces (89).

4.3. Passive Shear Mechanics

Simulations of cardiac mechanics require, as input, the stress-strain (i.e., constitutive) properties of the myocardium. Myocardial stress-strain properties can be measured experimentally using devices that deform tissue samples, and measure the stresses required for such deformation. Myocardium is now accepted as orthotropic, with unique stiffness properties along f, s, and n. By mounting pieces of myocardium along different orientations, Dokos et al. (31) measured myocardial shear stiffness along the six mesoscale shear modes (Section 4.1). From their experiments, it was found that shear modes that produced sliding of sheetlets had lower shear stiffness compared with other shear modes, providing evidence that sheetlet shear facilitates mesoscale strain. These findings have since been confirmed in human hearts (85).

One of the limitations of these studies is that the size of the myocardial samples are by necessity much larger than myocardial mesostructural features. Li et al. (87) addressed this limitation by taking DTI measurements of the myocardial cubes, to match the strain measurements with the mesostructural features. These passive shear experiments are important experimental data for validating computational models of the heart. However, the identifiability of model parameters remains a problem even with experimental data available, as parameters can differ by several orders of magnitude between different myocardial samples. A comprehensive and well-validated model of myocardial constitutive properties remains an open challenge in the field.

5. SHEETLET REMODELING IN DISEASE

The link between mesostructure and function can become disrupted in disease states. In this section, we review the studies of impaired mesofunction in a range of cardiac pathologies (Table 3). These include impaired mesofunction because of the loss of aggregate cardiomyocyte organization (Section 5.1), the loss of sheetlet organization and the fibrosis that fuses adjacent sheetlets (Section 5.2), and abnormal sheetlet reorientation (Section 5.3).

Table 3.

A summary of studies that have examined mesofunction in different cardiac pathologies

| First Author | Year | Methods | Animal | Sample Size | Key Finding | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheng | 2012 | DTI and histology | Mice | 27 | Calcium mishandling is implicated in impaired sheetlet mechanics. | 91 |

| Ferreira | 2014 | DTI in vivo | Human | 22 | Patients with HCM show systolic-like E2A during diastole. | 13 |

| Garcia-Canadilla | 2019 | HREM | Mice | 56 | HCM mice showed a loss of linear helix angle profile, fewer circumferential aggregate cardiomyocytes, and greater disarray during fetal development. | 26 |

| Carruth | 2020 | DTI and histology | Rat | 16 | In pressure-overload hypertrophy, sheetlet dispersion is greater in the subendocardium. | 22 |

| Le | 2020 | DTI ex vivo | Sheep | 6 | Both helix angle and E2A are similar between term and preterm hearts. | 90 |

| Das | 2021 | DTI in vivo | Human | 30 | Infarction reduces fractional anisotropy and E2A. Both measures are associated with reduced ejection fraction. | 92 |

DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; E2A, secondary eigenvector angle; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

5.1. Loss of Aggregate Cardiomyocyte Organization

With DTI, the fractional anisotropy (Section 3.1) can be measured, providing an estimate of the coherence of aggregate cardiomyocyte orientation. Fractional anisotropy measurements from DTI have been shown to correlate with histological measures of cardiomyocyte splay (68). Patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) exhibit a lower fractional anisotropy as compared with healthy hearts (93, 94). In addition, when the HCM cohort was divided, those who suffered ventricular arrhythmia showed a significantly lower fractional anisotropy than the patients with HCM that exhibited no arrhythmia (94).

A mesostructural feature that may contribute to impaired function is the loss of healthy helix angle profile. The presence of cardiomyocytes with a significant longitudinal orientation are thought to contribute to efficient ejection (42). Although healthy hearts show a significant change in helix angle slope between systole and diastole, hearts with dilated cardiomyopathy do not show a significant change in helix angle slope through the cardiac cycle (11).

Acute myocardial infarction and its associated loss of tissue oxygenation leads to cardiomyocyte death, and eventual replacement fibrosis. Multiple studies have confirmed that infarcted myocardium has an increased mean diffusivity and a decreased fractional anisotropy (68, 95–100). The mechanism by which mean diffusivity increases is thought to be the replacement fibrosis expanding the proportion of extracellular matrix relative to cardiomyocyte volume. Extracellular matrix is less restrictive of water diffusion and thus the expanded extracellular matrix within the infarct produces an increased mean diffusivity. In addition, as cardiomyocytes have both mechanical and electrochemical coupling, cardiomyocyte death resulting from acute ischemia results in a loss of cardiomyocyte organization. The loss of cardiomyocyte cellular organization (known as “fiber disarray”) in turn is thought to cause the decreased fractional anisotropy in the infarcted region.

Interestingly, the fractional anisotropy within the infarct is not entirely isotropic, and the remaining primary eigenvector is aligned with collagen structures within the infarct (101). Pashakhanloo et al. found that within the infarcted myocardium, the collagen fibers (not cardiomyocytes) maintained a helix angle similar to the cardiomyocyte helix angle in healthy myocardium (68, 95, 102). The helix angle transmural slope was steeper in the infarct region, thought to be due to wall thinning. Conversely, Sosnovik et al. (103) used a diffusion tractography approach and found that the infarct regions did not retain a normal transmural helix angle, but rather contained nodes of crossing fibers, which are absent from normal myocardium. In addition, in hearts that have been infarcted, the remote zone may also undergo mesostructural remodeling (99). In particular, the helix angle becomes more right-handed, and this change is correlated with ventricular hypertrophy.

5.2. Loss of Sheetlet Organization

LeGrice et al. (33) examined the progressive change in cardiac mesostructure in the spontaneously hypertensive rat model of hypertensive heart disease. With extended volume confocal microscopy (Section 3.5), myocardial tissue was stained for collagen and imaged. These image volumes were able to show differences in collagen structures, as well as the sheetlet organization during the progression of disease. During late stage hypertensive heart disease, toward decompensated heart failure, the thickness of sheetlets increased, with a greater number of cardiomyocytes per layer (∼6) compared with controls (∼3). This fusing of myocardial sheetlets was associated with reduced fractional shortening at the ventricular level, measured using echocardiography. LeGrice et al. proposed that these abnormally thick sheetlets are less amenable to sliding, and less able to produce radial thickening required for effective ejection of blood.

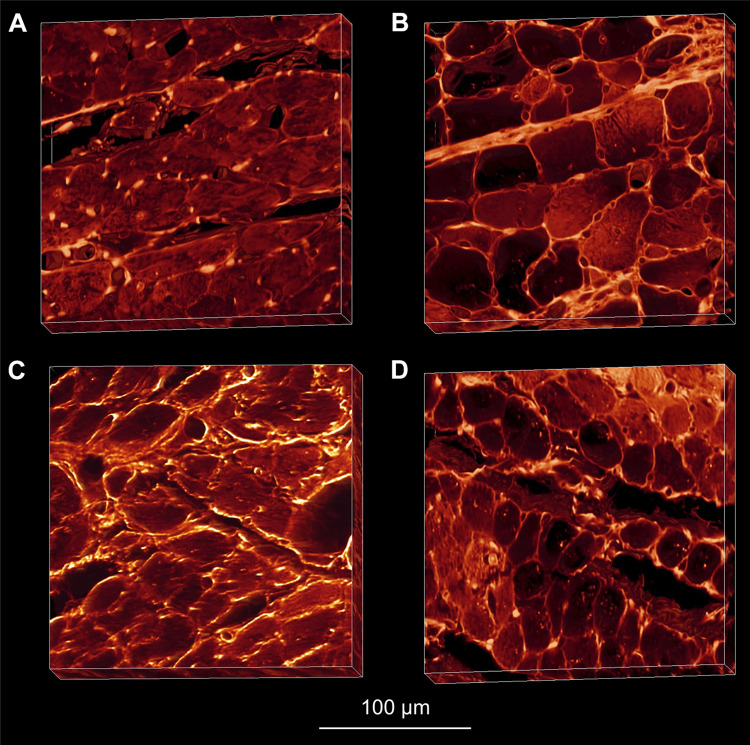

Collagen deposition is another process that can lead to the fusing of sheetlets, and the loss of mechanically separated sheetlets (Fig. 6). During the phase of compensated hypertrophy, the myocardium shows increased perimysial collagen deposition between sheetlets (33, 77), fusing sheetlet layers and limiting sheetlet shear. Treatment of hypertension with quinapril curtailed this deposition of collagen between sheetlets, and as such the number of cardiomyocytes per sheetlet in treated hearts was similar to those of control hearts (∼3.5 cells/sheetlet), in contrast to the diseased hearts (∼5.5 cells/sheetlet) (77). Continued quinapril treatment led to vastly different trajectories in terms of cardiac function, with treated hearts showing significantly greater ejection fraction, reduced mean arterial pressure, and improved rate of survival compared with diseased hearts.

Figure 6.

Extended volume confocal microscopy of laminar mesostructure in healthy (A), diseased (B) and treated (C and D) hearts. Sheetlets of the Wistar Kyoto (A) and treated spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR, C and D) showed no collagen deposition between sheetlets, maintaining normal sheetlet organization. However SHR (B) myocardium showed marked deposition of collagen between sheetlets, and the loss of structural separation. Reproduced with permission from Wilson et al. (77).

5.3. Abnormal Sheetlet Reorientation

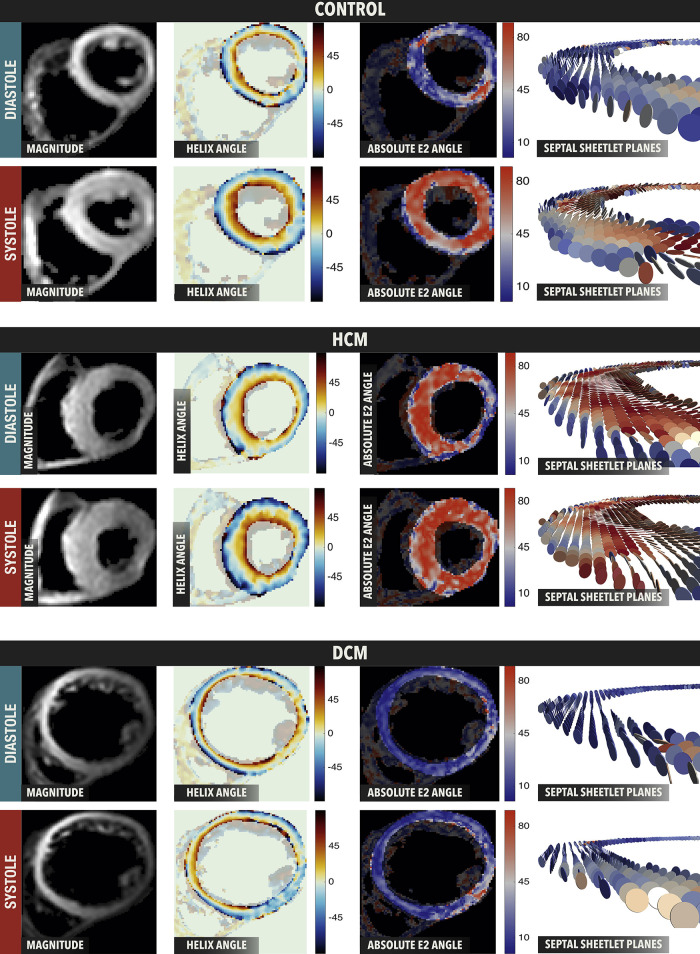

In HCM, the heart wall becomes thickened and patients can progress to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, irregular electrical activation, and sudden cardiac death. McGill et al. (104) demonstrated the clinical feasibility of in vivo cardiac DTI in patients with HCM. Further studies using in vivo cardiac DTI in patients with HCM demonstrated altered sheetlet dynamics in these patients (13). In particular, the E2A mobility, which is the reorientation of sheetlets between systole and diastole, was diminished in patients with HCM. E2A has been shown to change between systole and diastole, as shown by in vivo, in situ, and ex vivo experiments (12). In healthy controls, E2A mobility was 45°, whereas in HCM hearts mobility was 23° (12). Therefore, HCM sheetlets appear “stuck” in a systolic orientation, and unable to reorient to a diastolic confirmation (Fig. 7). As such, HCM hearts have a normal E2A during systole, but an abnormal E2A during diastole (12, 94). Abnormal sheetlet orientation and mobility in patients with HCM is thought to be due to their calcium sensitivity, and residual tension in the diastolic state (13).

Figure 7.

In vivo sheetlet orientation in control, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) hearts. In control hearts, secondary eigenvector angle (E2A) is low (blue) in diastole and high (red) in systole. HCM hearts show high (red) E2A in both systole and diastole, whereas DCM hearts show low (blue) E2A in both systole and diastole. Reproduced under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 from Nielles-vallespin et al. (62).

In dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) the ventricular lumen dilates, impairing ejection of blood, with patients progressing to heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. In patients with DCM, E2A mobility is lower (20°) as compared with healthy controls (45°) (12). In DCM hearts, sheetlets are “stuck” in a diastolic orientation, and unable to reorient to a systolic confirmation. This is supported by the E2A frequency distributions in diastole and systole, with DCM hearts showing a normal E2A distribution in diastole, but not systole.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a disease caused by a mutation in the gene that codes for dystrophin. It is characterized by muscle weakness, with death occurring due to respiratory failure or heart failure. Using the Mdx model of DMD, hearts were arrested in either systole or diastole, and perfused with either normal or low levels of calcium (37). Under normal calcium conditions, Mdx mice showed reduced diastolic E2A, and reduced E2A mobility. Perfusion with a low concentration of calcium restored E2A mobility to normal levels, suggesting that calcium dynamics are an important component of sheetlet mechanics.

6. IN VIVO ASSESSMENT OF MYOCARDIAL MESOSTRUCTURE

There are several current and emerging methods for assessment of cardiac mesostructure in vivo. Key considerations for clinical translation include: motion compensation (Section 6.1), and the potential of combination diffusion-strain techniques for measuring mesostructural mechanics (Section 6.2).

6.1. Motion Compensation of in Vivo Cardiac DTI

Diffusion tensor MRI has provided substantial insight to the microstructural organization of tissues by enabling measurement of the diffusion coefficient of water along many directions. Probing the self-diffusion of water requires the use of strong gradient waveforms that also incur high sensitivity and data corruption from bulk tissue motion. For many in vivo applications, the bulk motion can be controlled or mitigated (e.g., brain or prostate imaging), but the continuous motion of the heart presents a special challenge. Cardiac DTI requires at least four kinds of coincident motion compensation: patient compliance, respiratory management, ECG synchronization, and specialized diffusion encoding methods. Bulk motion of the heart that is not mitigated or accounted for can produce MRI signal phase accrual artifacts, and significant loss of signal. Minimizing motion during the MRI acquisition can be achieved by using fast single-shot echo-planar imaging readouts and navigator-gated or breath hold approaches to minimize respiratory motion (105). Navigator-based approaches can be used to track motion, which allows for slice-tracking and increases acquisition efficiency (106).

Some cardiac DTI acquisition methods (e.g., stimulated echo-acquisition mode) align the image acquisition times with diastole, which is typically less dynamic than systole (107, 108). This approach requires longer scan times and has inherently lower signal-to-noise ratio, but can be quite motion robust. Other approaches (e.g., motion compensated spin echo-echo planar imaging, SE-EPI) demonstrate robust data acquisition during end systole, a time point that is highly repeatable and for which motion paths are very consistent.

The motion of spins through a magnetic field can be expressed with a Taylor series expansion (e.g., position, velocity, acceleration, etc.), and phase artifacts from high-order motion features can be mitigated by adding additional diffusion sensitizing gradient waveforms that null the effects of nonstationary tissue. For example, M1 + M2-nulled (i.e., velocity and acceleration nulled) DTI enables in vivo cardiac DTI with high signal-to-noise ratio, and SE-EPI can allow human in vivo cardiac DTI acquisitions of ∼10 min for a single slice using SE-EPI (14, 109). M2-nulling has been found to optimize the combination of b-value, signal-to-noise, and insensitivity to motion (110).

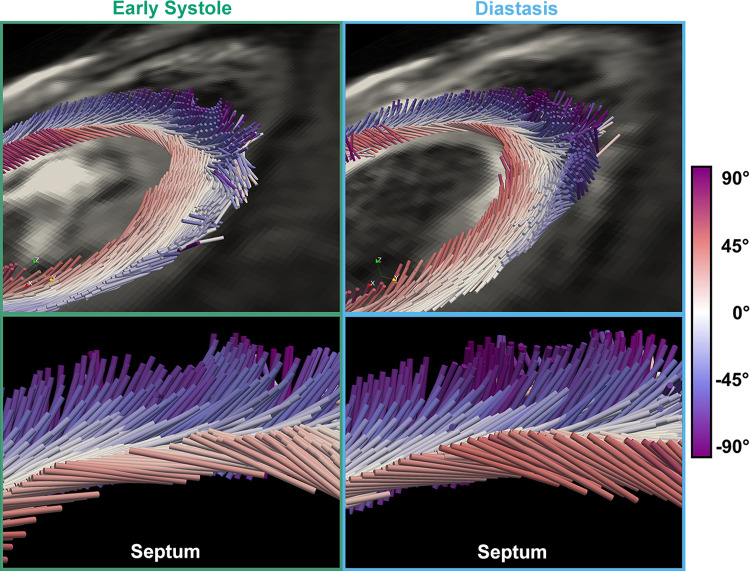

6.2. DTI and Strain

One promising application of in vivo cardiac DTI is that it can be combined with strain imaging techniques (such as DENSE). The combination of cardiac DTI with strain imaging allows for the measurement of cardiac mesofunction in vivo (10, 14, 15, 111). The cardiac DTI acquisition measures the aggregate cardiomyocyte direction, and strain imaging method measures the displacement of pixels during the cardiac cycle. These mesostructural and functional data can be combined using various computational modeling approaches (10, 11, 14, 15, 111). By measuring the displacement during the cardiac cycle along the aggregate cardiomyocyte direction, the aggregate cardiomyocyte strain can be calculated, as well as the reorientation of aggregate cardiomyocyte helix angle through the cardiac cycle (Fig. 8). Unlike circumferential strain that varies according to transmural location, measurement of aggregate cardiomyocyte strain in vivo has been shown to be uniform across the wall (14). Although these methods have so far been applied only to healthy humans, measurement of aggregate cardiomyocyte strain has the potential to identify cardiac pathology at the mesoscale, which could be masked by compensatory remodeling at the organ level.

Figure 8.

The reorientation of aggregate cardiomyocytes through the cardiac cycle. Cylinders represent the aggregate cardiomyocyte direction, with color indicating the helix angle. During early systole (left) to diastasis (right) subendocardial helix angle increases. Reproduced under CC BY 4.0 from Moulin et al. (15).

7. FUTURE RESEARCH AND CONCLUSIONS

7.1. Future Work

The field of cardiac mesostructure is well positioned for new insights and developments. There is still some disagreement as to whether multiple sheetlet orientations are the norm throughout the heart. Future work along these lines would examine myocardial samples with multiple imaging modalities, and perhaps investigate the histology preparation parameters that most impact the presence or absence of multiple sheetlet populations in histology slides. The rearrangement of sheetlets during myocardial deformation would also benefit from mesostructural imaging of the same myocardial sample in multiple strain configurations, ideally in vivo or in vitro. Developments in cardiac DTI pulse sequences, particularly improvements that reduce acquisition times and increase signal-to-noise ratio would be of high value, as scan length is currently a major impediment to their adoption in the clinic. A database of sheetlet orientations from different animal species and in different contraction states would be of great interest to the computational modeling field. In particular, mesostructural data from various disease models would be particularly valuable and would provide insights to the mesostructural features that translational researchers should investigate in human pathophysiology.

7.2. Conclusion

Developments in both in vivo and ex vivo imaging techniques allow for examination of cardiac mesostructure in unprecedented detail over the whole heart. Multiple studies have confirmed the critical contributions of sheetlets to ventricular wall thickening during the cardiac cycle. Impaired sheetlet mobility resulting from collagen deposition between sheetlets and dysfunctional calcium handling may provide avenues for pharmacological treatment of impaired mesofunction. Emerging approaches to combine mesostructural and mesofunctional imaging techniques allow for the measurement of aggregate cardiomyocyte strain and sheetlet mobility, thereby providing mechanistic insight to cardiac function and dysfunction.

GLOSSARY

- Aggregate cardiomyocyte

Referring to properties of a collection of cardiomyocytes within an imaging voxel.

- Cardiac axial strains

Circumferential strain (ECC), longitudinal strain (ELL), and radial strain (ERR) (Fig. 1, Macroscale function).

- Cardiomyocyte direction (f)

Direction aligned with the cardiomyocyte longitudinal axis (Fig. 1, Microscale structure).

- Cross-myocyte plane

The plane normal to the cardiomyocyte long-axis direction (Fig. 2B).

- Cardiac shear strains

Ventricular torsion or circumferential-longitudinal shear strain (ECL), longitudinal-radial shear strain (ELR), and circumferential-radial shear strain (ECR).

- E2A

The angle between the radial direction and the projection of the s onto the cross-myocyte plane (Fig. 2D).

- Helical angle

The angle between f and the short-axis plane without projection (Fig. 2C).

- Helix angle

The angle between the circumferential direction and the projection of f onto the tangential plane (Fig. 2C).

- Intrusion angle

The angle between f and the tangential plane without projection (Fig. 2E).

- Normal direction (n)

Direction perpendicular to both the cardiomyocyte and sheetlet directions (Fig. 1, Microscale structure).

- Sheetlets

A group of cardiomyocytes ∼4 ± 2 cells in thickness, arranged in a sheet-like structures (34). Sheetlets branch and interconnect with one another at the mesoscale (Fig. 1, Microscale structure).

- Sheetlet azimuth

The angle between the radial direction and the projection of n onto the short-axis plane (Fig. 2F).

- Sheetlet direction (s)

Direction perpendicular to the cardiomyocyte direction, but within the sheetlet plane (Fig. 1, Microscale structure).

- Sheetlet elevation

The angle between the radial direction and the projection of n onto the long-axis plane (Fig. 2F).

- Transverse angle

The angle between the circumferential direction and the projection of f onto short-axis plane. Historically known as the imbrication angle (Fig. 2E) (112).

GRANTS

This work was supported, in part, by American Heart Association Grant 19IPLOI34760294 (to D.B.E.) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01-HL131823 (to D.B.E.) and R01-HL152256 (to D.B.E.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.J.W. and D.B.E. conceived and designed research; A.J.W. and G.B.S. prepared figures; A.J.W. drafted manuscript; A.J.W., G.B.S., I.J.L., A.A.Y., and D.B.E. edited and revised manuscript; A.J.W., G.B.S., I.J.L., A.A.Y., and D.B.E. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Amy Thomas and Rudilyn Joyce Wilson for assistance with preparing figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Spotnitz HM, Spotnitz WD, Cottrell TS, Spiro D, Sonnenblick EH. Cellular basis for volume related wall thickness changes in the rat left ventricle. J Mol Cell Cardiol 6: 317–331, 1974. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(74)90074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant RP. Notes on the muscular architecture of the left ventricle. Circulation 32: 301–308, 1965. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.32.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auchampach J, Han L, Huang GN, Kühn B, Lough JW, O'Meara CC, Payumo AY, Rosenthal NA, Sucov HM, Yutzey KE, Patterson M. Measuring cardiomyocyte cell-cycle activity and proliferation in the age of heart regeneration. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 322: H579–H596, 2022. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00666.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rienks M, Papageorgiou AP, Frangogiannis NG, Heymans S. Myocardial extracellular matrix: an ever-changing and diverse entity. Circ Res 114: 872–888, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pope AJ, Sands GB, Smaill BH, LeGrice IJ. Three-dimensional transmural organization of perimysial collagen in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: 1243–1252, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00484.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howe K, Ross JM, Loiselle DS, Han JC, Crossman DJ. Right-sided heart failure is also associated with transverse tubule remodeling in the left ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 321: H940–H947, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00298.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trew ML, Caldwell BJ, Sands GB, Hooks DA, Tai DC-S, Austin TM, LeGrice IJ, Pullan AJ, Smaill BH. Cardiac electrophysiology and tissue structure: bridging the scale gap with a joint measurement and modelling paradigm. Exp Physiol 91: 355–370, 2006. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.031054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodríguez-Padilla JR, Petras A, Magat J, Bayer J, Bihan-Poudec Y, El Hamrani D, Ramlugun G, Neic A, Augustin CM, Vaillant F, Constantin M, Benoist D, Pourtau L, Dubes V, Rogier J, Labrousse L, Bernus O, Quesson B, Haïssaguerre M, Gsell M, Plank G, Ozenne V, Vigmond E. Impact of intraventricular septal fiber orientation on cardiac electromechanical function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 322: H936–H952, 2022. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00050.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen NT, Goransson C, Vejlstrup N, Carlsen J. Myocardial adaptation and exercise performance in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension assessed with patient-specific computer simulations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 321: H865–H880, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00442.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verzhbinsky IA, Perotti LE, Moulin K, Cork TE, Loecher M, Ennis DB. Estimating aggregate cardiomyocyte strain using in vivo diffusion and displacement encoded MRI. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 39: 656–667, 2020. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2019.2933813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Deuster CV, Sammut E, Asner L, Nordsletten D, Lamata P, Stoeck CT, Kozerke S, Razavi R. Studying dynamic myofiber aggregate reorientation in dilated cardiomyopathy using in vivo magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 9: 1–10, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielles-Vallespin S, Khalique Z, Ferreira PF, de Silva R, Scott AD, Kilner P, McGill LA, Giannakidis A, Gatehouse PD, Ennis D, Aliotta E, Al-Khalil M, Kellman P, Mazilu D, Balaban RS, Firmin DN, Arai AE, Pennell DJ. Assessment of myocardial microstructural dynamics by in vivo diffusion tensor cardiac magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 69: 661–676, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferreira PF, Kilner PJ, McGill LA, Nielles-Vallespin S, Scott AD, Ho SY, McCarthy KP, Haba MM, Ismail TF, Gatehouse PD, de Silva R, Lyon AR, Prasad SK, Firmin DN, Pennell DJ. In vivo cardiovascular magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging shows evidence of abnormal myocardial laminar orientations and mobility in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 16: 87, 2014. doi: 10.1186/s12968-014-0087-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moulin K, Croisille P, Viallon M, Verzhbinsky IA, Perotti LE, Ennis DB. Myofiber strain in healthy humans using DENSE and cDTI. Magn Reson Med 86: 277–292, 2021. doi: 10.1002/mrm.28724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moulin K, Verzhbinsky IA, Maforo NG, Perotti LE, Ennis DB. Probing cardiomyocyte mobility with multiphase cardiac diffusion tensor MRI. PLoS One 15: e0241996, 2020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angeli S, Befera N, Peyrat J-M, Calabrese E, Johnson GA, Constantinides C. A high-resolution cardiovascular magnetic resonance diffusion tensor map from ex-vivo C57BL/6 murine hearts. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 16: 77, 2014. doi: 10.1186/s12968-014-0077-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernus O, Radjenovic A, Trew ML, LeGrice IJ, Sands GB, Magee DR, Smaill BH, Gilbert SH. Comparison of diffusion tensor imaging by cardiovascular magnetic resonance and gadolinium enhanced 3D image intensity approaches to investigation of structural anisotropy in explanted rat hearts. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 17: 31, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s12968-015-0129-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teh I, McClymont D, Burton RAB, Maguire ML, Whittington HJ, Lygate CA, Kohl P, Schneider JE. Resolving fine cardiac structures in rats with high-resolution diffusion tensor imaging. Sci Rep 6: 30573, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep30573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teh I, McClymont D, Zdora MC, Whittington HJ, Davidoiu V, Lee J, Lygate CA, Rau C, Zanette I, Schneider JE. Validation of diffusion tensor MRI measurements of cardiac microstructure with structure tensor synchrotron radiation imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 19: 31, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12968-017-0342-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haliot K, Magat J, Ozenne V, Abell E, Dubes V, Bear LR, Gilbert SH, Trew ML, Haïssaguerre M, Quesson B, Bernus O. 3D high resolution imaging of human heart for visualization of the cardiac structure. Functional Imaging and Modeling of the Heart, edited by Coudière Y, Ozenne V, Vigmond E, Zemzemi N.. Cham: Springer, 2019, p. 196–207. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-21949-9_22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giannakidis A, Gullberg GT. Transmural remodeling of cardiac microstructure in aged spontaneously hypertensive rats by diffusion tensor MRI. Front Physiol 11: 265, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carruth ED, Teh I, Schneider JE, McCulloch AD, Omens JH, Frank LR. Regional variations in ex-vivo diffusion tensor anisotropy are associated with cardiomyocyte remodeling in rats after left ventricular pressure overload. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 22: 21, 2020. doi: 10.1186/s12968-020-00615-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magat J, Ozenne V, Cedilnik N, Naulin J, Haliot K, Sermesant M, Gilbert SH, Trew M, Haissaguerre M, Quesson B, Bernus O. 3D MRI of explanted sheep hearts with submillimeter isotropic spatial resolution: comparison between diffusion tensor and structure tensor imaging. Magn Reson Mater Phys Biol Med 34: 741–755, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s10334-021-00913-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sands GB, Smaill BH, Legrice IJ. Virtual sectioning of cardiac tissue relative to fiber orientation. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2008: 226–229, 2008. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2008.4649131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbert SH, Benoist D, Benson AP, White E, Tanner SF, Holden AV, Dobrzynski H, Bernus O, Radjenovic A. Visualization and quantification of whole rat heart laminar structure using high-spatial resolution contrast-enhanced MRI. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H287–H298, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00824.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia-Canadilla P, Cook AC, Mohun TJ, Oji O, Schlossarek S, Carrier L, McKenna WJ, Moon JC, Captur G. Myoarchitectural disarray of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy begins pre-birth. J Anat 235: 962–976, 2019. doi: 10.1111/joa.13058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.LeGrice IJ, Smaill BH, Chai L, Edgar SG, Gavin B, Hunter PJ. Laminar structure of the heart: ventricular myocyte arrangement and connective tissue architecture in the dog. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 260: 1365–1378, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.2.h571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert SH, Benson AP, Li P, Holden AV. Regional localisation of left ventricular sheet structure: integration with current models of cardiac fibre, sheet and band structure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 32: 231–249, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson RH, Niederer PF, Sanchez-Quintana D, Stephenson RS, Agger P. How are the cardiomyocytes aggregated together within the walls of the left ventricular cone? J Anat 235: 697–705, 2019. doi: 10.1111/joa.13027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arts T, Costa KD, Covell JW, McCulloch AD. Relating myocardial laminar architecture to shear strain and muscle fiber orientation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: 49–45, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.h2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dokos S, Smaill BH, Young AA, LeGrice IJ. Shear properties of passive ventricular myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: 2650–2659, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00111.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]