Abstract

While there has been an overall decline of tobacco and alcohol-related head and neck cancer in recent decades, there has been an increased incidence of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer (OPC). Recent research studies and clinical trials have revealed that the cancer biology and clinical progression of HPV-positive OPC is unique relative to its HPV-negative counterparts. HPV-positive OPC is associated with higher rates of disease control following definitive treatment when compared to HPV-negative OPC. Thus, these conditions should be considered unique diseases with regards to treatment strategies and survival. In order to sufficiently characterize HPV-positive OPC and guide treatment strategies, there has been a considerable effort to diagnose, prognose, and track the treatment response of HPV-associated OPC through advanced imaging research. Furthermore, HPV-positive OPC patients are prime candidates for radiation de-escalation protocols, which will ideally reduce toxicities associated with radiation therapy and has prompted additional imaging research to detect radiation-induced changes in organs at risk. This manuscript reviews the various imaging modalities and current strategies for tackling these challenges as well as provides commentary on the potential successes and suggested improvements for the optimal treatment of these tumors.

Introduction

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is integral to the management of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer (OPC). As many patients will present with extensive lymphadenopathy and/or radiographic evidence of extranodal extension (ENE), definitive chemoradiation therapy or surgery followed by adjuvant radiation therapy (with or without chemotherapy) forms the foundation of treatment [1], [2]. Although EBRT can achieve favorable rates of progression-free survival and overall survival for HPV-positive OPC, radiation therapy for head and neck cancer (HNC) is associated with several chronic side effects for survivors, including xerostomia, dysphagia, and osteoradionecrosis, all of which have detrimental impacts on patients’ quality of life. Therefore, there have been increased efforts to prospectively examine alternative radiation therapy strategies, such as dose de-escalation, as a mechanism of reducing the incidence and severity of side effects, while maintaining oncologic treatment integrity [3]–[7]. Strategic hurdles arise due to differences in outcomes associated with the heterogeneity of the HPV-positive OPC population, with greater than 10-pack-year smoking history and advanced adenopathy portending worse prognosis [8]. Additionally, locoregional recurrence remains a source of treatment failure following management with standard radiation therapy doses [9], [10]. Therefore, radiographic techniques that comprehensively characterize HPV-positive OPC are necessary to identify prognostic variables and clarify treatment efficacy. In the following sections, we review and discuss the role of advanced imaging modalities in the evaluation of baseline extent of disease, radiation therapy treatment response, treatment-related side effects, and treatment escalation/de-escalation for HPV-positive OPC.

Clinical Imaging and Analytical Techniques

CT and T1- and T2-weighted MRI have served as the quintessential modalities to image anatomic structures in the modern era of HNC imaging. Improvements in hardware, sequence development, and reconstruction techniques have led to advances in artifact reduction, tissue-specific attenuation, motion correction, and sub-millimeter resolutions, all while minimizing radiation dose and acquisition time. CT and T1- and T2-weighted MRI are the current gold standards for EBRT treatment planning and imaging for post-treatment follow-up exams. However, functional imaging techniques are becoming increasingly common in the radiation therapy pipeline, and descriptions of the various biomarkers acquired with these techniques are presented in Table 1.

Table 1:

Description of image biomarkers for various quantitative and functional imaging techniques which are discussed in this manuscript.

| Imaging Technique | Image Biomarker | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI) MRI | Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) | Combined magnitude of random displacement of water molecules within a tissue and microcirculation of water molecules within the capillary network of the tissue |

| Intra-Voxel Incoherent Motion (IVIM) MRI | Perfusion Fraction (f) | Fraction of perceived signal attenuation which is due to microcirculation of water molecules within the capillary network of the tissue |

| Diffusion Coefficient (D) | Magnitude of random displacement of water molecules within a tissue | |

| Pseudo Diffusion Coefficient (D*) | Magnitude of microcirculation of water molecules within the capillary network of a tissue | |

| Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced (DCE) MRI | Transfer Coefficient (Ktrans) | Rate of contrast agent extravasation from vascular space to extravascular extracellular space (EES) (due to blood flow and capillary leakage) |

| Fractional Volume in Extravascular Extracellular Space (ve) | Relative amount of available EES in a tissue for contrast agent. | |

| Rate Constant (kep) | Rate of contrast agent intravasation from EES back to the vascular space (= Ktrans/ ve) | |

| Fractional Plasma Volume (vp) | Relative amount of vasculature space for contrast agent | |

| Positron Emission Tomography (PET) | Standard Uptake Value (SUV) | Ratio of tissue radioactivity concentration to the injected dose (normalized by patient weight) |

| Metabolic Tumor Volume (MTV) | Volume of tumor with threshold value of SUV | |

| Total Lesion Glycolysis (TLG) | Multiplication of mean SUV and MTV |

Functional MRI techniques include diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), intra-voxel incoherent motion (IVIM) imaging, and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI. DWI MRI is a quantitative MRI technique that measures the random motion (diffusion) of water molecules within each imaging voxel and thus implies how tightly packed cells are in a tissue [11]. Many tumors, including OPC, are characterized by densely packed cells compared to healthy tissue, thereby resulting in restricted diffusion [12]. IVIM MRI is a variant of DWI that splits the MRI signal into two components- diffusion (i.e. random motion of water molecules within a tissue) and perfusion (i.e. pseudo-random motion of water molecules in blood through the capillary network)- to better isolate physiologic changes associated with tumor growth and treatment response [13], [14]. In DCE MRI, a series of images are acquired in rapid succession following administration of a paramagnetic contrast agent, which causes increased signal intensity (SI) in T1-weighted MRI. The kinetics and spatial patterns of contrast enhancement can improve the capacity to characterize tumors by providing information about the underlying structure and vascular function of the tumor microenvironment [15].

Positron emission tomography (PET) has emerged as a third pillar of imaging for the baseline and post-treatment evaluation of HNC. PET is a functional imaging technique that generates images of metabolic radiotracer uptake. The most common radiotracer, 2–18F fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG), allows for the analysis of glucose metabolism [16]. As replicative cancer cells often demonstrate high levels of glucose metabolism, the corresponding FDG avidity can be used in the imaging for assessment of malignant tissue [17]. A major advantage that PET offers in comparison to anatomical imaging modalities is the ability to perform quantitative studies of radiotracer uptake [18]. Modern PET images are often co-registered with CT images to localize metabolic information to anatomic structures (PET/CT). However, the development of simultaneous PET/MRI systems has facilitated the characterization of quantitative metabolic activity in combination with exquisite soft tissue contrast. Outside of FDG, there are few alternative radioisotopes used for PET imaging in clinical radiation oncology settings. However, imaging tumor hypoxia with oxygen-sensing radioisotopes has garnered interest across the field of oncology as it has been associated with more aggressive and therapy-resistant phenotypes [19].

Throughout the last few decades, the amount of imaging data collected for cancer patients has steadily increased. This has been driven by the dependence on imaging for oncologic treatment and the improvement in utility of radiological images, which directly influence oncologic treatment approaches such as dose schedules and target definitions. Medical images contain information of the tumor and normal tissue characteristics. These data can be mined to improve prediction of treatment outcome or tumor diagnosis in a process known as radiomics [20]. Radiomics refers to the quantification of patient-specific tissue characteristics from images to feature values [21]. These image features represent intensity, texture and geometric properties of the tissue from a specific volume of interest and are captured in single variables that can provide inputs for machine learning and deep learning models, more generally known as artificial intelligence (AI). While these features can describe similar characteristics as semantic features (e.g. heterogeneity of the tumor), it is hypothesized that they can identify image patterns beyond the observable capacity of human readers [20], [22]. One current challenge with radiomics, which is the motivation for many current studies, is the normalization of images so that image features can be standardized between patients imaged on the same scanner as well as between scanners and with varying sequence parameters. Until this is achieved, the detection of minute differences between disease states or treatment effects remains very difficult. While image texture definitions originate from the 1970s and 80s, the radiomics concept was introduced in 2012 and proposed a comprehensive feature extraction in order to convert medical images into high-dimensional minable data [20], [23].

The remainder of this manuscript will highlight the various clinical applications of these imaging techniques with respect to the treatment of HPV-positive OPC with radiation therapy. For clarity, clinical utility of the associated biomarkers and their statistical and predictive quantification are provided in Table 2.

Table 2:

Imaging biomarkers in OPC and their performance for several clinical applications. The majority of listed studies investigate biomarker efficacy in HPV-positive OPC patient cohorts or between HPV-positive and HPV-negative cohorts. However, some of the listed studies (denoted by * in the Ref. column) which had OPC patient cohorts of mixed HPV status did not conduct a sub-analysis on HPV-positive OPC. These are still included in this table as the results are compelling in the general OPC patient population and could potentially be applied to HPV-positive OPC patient cohorts.

| Clinical Application | Imaging Technique | Biomarker(s) | Statistics | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification of HPV-positive OPC primary tumors compared with HPV-negative OPC | CT and T2-weighted MRI + clinical features | More likely to be smaller and exophytic. Less likely to display ulceration or necrosis | AUC = 0.84 (95% CI: 0.80–0.89) | [24] |

| CT radiomics | Smaller and less complex shape | AUC = 0.911 (0.905–0.916) PPV = 0.856 (0.848–0.864) NPV = 0.829 (0.81–0.848) |

[27] | |

| AUC = 0.75 (0.67–0.83) | [26] | |||

| CT radiomics | More homogeneous CT density | AUC = 0.78 Sensitivity = 0.62 Specificity = 0.82 |

[28] | |

| T1-weighted MRI radiomics + clinical features | Smaller, rounder tumors with more homogeneous MRI density | AUC = 0.871 (0.866–0.876) Sensitivity = 0.88 (0.87–0.89) Specificity = 0.68 (0.67‐0.69) PPV = 0.73 (0.72‐0.74) NPV = 0.85 (0.84‐0.86) |

[30] | |

| DWI MRI | Lower ADC | Sensitivity = 0.833 Specificity = 0.786 |

[31] | |

| DWI MRI | Lower ADC. Higher kurtosis (homogenous ADC) and skewness (few areas of high ADC) | P < 0.05 | [34] | |

| DWI, T1-weighted, and T2-weighted MRI radiomics | Higher values of ADC wavelet and texture features | AUC = 0.77 (0.50–0.96) Sensitivity = 0.71 (0.31–0.97) Specificity = 0.72 (0.50– 1.00) |

[41] | |

| IVIM | Lower values of ADC and D (diffusion) | P < 0.003 | [42] | |

| DWI, IVIM, DCE MRI, FDG-PET | Lower values of ADC, D (diffusion) and Ktrans, ve (permeability). Higher values of f and D* (perfusion). Lower SUV (glucose uptake) | P < 0.05 | [43] | |

| DCE MRI | Higher Ktrans (mean and histogram features) | P < 0.01 | [44] | |

| FDG-PET | Smaller tumors. Lower values of SUV, MTV, and TLG | P < 0.01 | [51] | |

| P < 0.002 | [52] | |||

| Improved prognosis HPV-positive OPC-primary tumor | CT radiomics | Lower value of radiomic signature composed of tumor density, shape, intratumor signal heterogeneity- survival | P < 0.001 | [56]* |

| CT radiomics | Lower Intensity Direct Local Range Max (LRM) and Neighbor Intensity Difference 2.5 Complexity- 5-year local control rate | P < 0.001 | [57]* | |

| CT radiomics | More homogeneous CT density- local control | Concordance index = 0.87 | [28]* | |

| DWI, IVIM, DCE MRI, FDG-PET | Lower values of Ktrans, ve (permeability- locoregional recurrence-free survival | Ktrans: Hazard ratio (HR) = 8.50 (1.68–43.1), p = 0.01 ve: HR = 1.64 (1.10–2.43), p = 0.015 |

[43]* | |

| Higher values of D* (perfusion) and lower values of ve (permeability) and SUV (glucose uptake)-overall survival | D*: HR: < 0.001 (< 0.001–0.1), p = 0.016 ve: HR = 5.514 (1.32–23.1), p = 0.019 SUV: HR = 1.189 (1.07–1.32), p = 0.001 |

|||

| FDG-PET | Lower MTV- progression-free survival | HR = 4.23, p < 0.0001 | [59] | |

| Lower MTV- overall survival | HR = 3.21, p = 0.0029 | |||

| FDG-PET | Lower MTV- event-free survival (recurrence or death) | HR = 1.02 (1.01–1.04), p = 0.002 | [60] | |

| FDG-PET | Lower TLG- locoregional failure-free survival | HR = 1.86 (1.29‐2.70), p = .001 | [61] | |

| Lower TLG- distant metastasis-free survival | HR = 1.45 (1.01‐2.08), p = .04 | |||

| Lower MTV-overall survival | HR = 1.51 (1.01‐2.27), p = .04 | |||

| FMISO-PET | Hypoxic HPV-negative OPC treated with tirapazamine vs. no tirapazamine - failure-free survival | HR = 5.18 (1.98–13.55), p = 0.001 | [53] | |

| Characterization of involved lymph nodes in HPV-positive OPC compared with HPV-negative OPC | CT and T2-weighted MRI | More cystic and clustered nodes | P < 0.04 | [24] |

| CT | More cystic nodes. Fewer cases of invasion of adjacent muscle | P < 0.015 | [25] | |

| T1- and T2-weighted MRI | More cystic nodes. Fewer necrotic nodes | P < 0.03 | [67] | |

| CT | More cystic nodes | Sensitivity = 0.38 Specificity = 0.73 PPV = 0.71 NPV = 0.41 |

[68] | |

| FDG-PET | Higher nodal SUV and intraindividual homogeneity | Sensitivity = 0.90 Specificity = 0.92 |

[46] | |

| FDG-PET | Higher nodal SUV, MTV, TLG | P < 0.01 | [49] | |

| Improved prognosis HPV-positive OPC-involved lymph nodes | T1- and T2-weighted MRI | Fewer necrotic nodes- regional failure | Odds ratio [OR] = 7.310, p = 0.011 | [67]* |

| Presence of cystic nodes-distant failure | OR = 0.087, p = 0.026 | |||

| CT | No matted nodes- 3-year disease-specific survival | P = 0.0004 | [70] | |

| CT | No matted nodes- 3-year disease-specific survival | P = .0001 | [71] | |

| Detection of ENE in HPV-positive OPC | CT | Presence of irregular margins. Absence of perinodal fat plane (2 readers) | AUC = 0.61, 0.59 Sensitivity = 0.25, 0.22 Specificity = 0.98, 0.85 PPV = 0.89, 0.78 NPV = 0.63, 0.61 |

[74] |

| CT | Presence of capsular contour irregularity, poorly defined nodal margins, or loss of intervening fat planes, and/or invasion of adjacent structures (2 readers) | Sensitivity = 0.55, 0.47 Specificity = 0.70, 0.85 PPV = 0.72, 0.82 NPV = 0.53, 0.53 |

[75] | |

| CT | 3 or more radiologically suspicious nodes (greater than 2 cm in a single dimension, heterogeneous appearance, cystic change, and/or irregular borders) | Sensitivity = 0.61 Specificity = 0.94 PPV = 0.92 NPV = 0.67 |

[76] | |

| CT | Internal characteristics (cystic, necrotic, solid), capsule contour, presence of perinodal fat stranding and invasion into surrounding structures (2 readers) | Sensitivity = 0.56, 0.61 Specificity = 0.73, 0.67 PPV = 0.68, 0.65 NPV = 0.62, 0.63 |

[78] | |

| Measurement of treatment response in HPV-positive OPC | CT radiomics | Reduced skewness and entropy features, and larger percent change in size | AUC = 0.80 | [137] |

| IVIM MRI | Increased ADC and D (diffusion) at mid-therapy | AUC = 0.87 (0.79–0.96) Sensitivity = 0.63 Specificity = 0.85 |

[82] | |

| IVIM MRI | Weekly increases in ADC and D (diffusion) throughout therapy | P < 0.003 | [83]* | |

| FDG-PET | Negative post-treatment exam | NPV = 0.92 | [84] | |

| FDG-PET | Nodal complete response 12-week post-therapy- disease free survival | HR = 0.47 (0.25‐0.89), p = 0.021 | [90]* | |

| Nodal complete response 12-week post therapy- local relapse-free survival | HR = 0.27 (0.11‐0.66), p = 0.004 | |||

| Primary response 12-week post-therapy- local relapse-free survival | HR = 0.37 (0.15‐0.93), p = 0.035 | |||

| FDG-PET | Primary tumor complete response 12-week post-therapy | Sensitivity = 0.33 (0.01–0.91) Specificity = 0.90 (0.82–0.95) PPV = 0.09 (0.00–0.41) NPV = 0.98 (0.92–1.00) |

[91] | |

| Nodal complete response 12-week post-therapy | Sensitivity = 0.00 (0.00–0.37) Specificity = 0.92 (0.85–0.97) PPV = 0.00 (0.00–0.41) NPV = 0.91 (0.83–0.96) |

|||

| FDG-PET | 12-week complete response in HPV-positive patients | PPV = 0.30 (0.23–0.39) NPV = 0.93 (0.87–0.96) |

[94] | |

| 3-month complete response in HPV-negative patients | PPV = 0.82 (0.57–0.94) NPV = 0.56 (0.33–0.76) |

|||

| FDG-PET | 12-week complete response | Sensitivity = 0.56 Specificity = 0.84 PPV = 0.12 NPV = 0.98 |

[95] | |

| 16-week complete response following 12-week incomplete response | Sensitivity = 0.80 Specificity = 0.78 PPV = 0.33 NPV = 0.97 |

|||

| Detection of radiation-induced toxicities in HNC | T1- and T2-weighted MRI | Mid-therapy: Increased T2 SI in pharyngeal constrictor muscles (PCM)- dysphagia | P = 0.002 | [110] |

| Post-therapy: Increased T1 SI in PCM- dysphagia | P < 0.0001 | |||

| T1- and T2-weighted MRI | Decreased T1 SI and increased T2 SI in PCM receiving > 50 Gy | P < 0.03 | [111]* | |

| T1- and T2-weighted MRI | Early post-therapy: Increased T2 SI in PCM (no dose relationship) | P < 0.0001 | [112]* | |

| Late post-therapy: Decreased T1 SI in PCM receiving > 62.5 Gy | P = 0.003 | |||

| Modified barium swallow (video fluoroscopy) | Higher DIGEST score (swallowing safety and efficiency)- swallowing inefficiency, dysphagia | P < 0.0001 | [114]* | |

| DCE MRI | Higher values of Ktrans, ve (permeability)- ORN | P < 0.0001 | [116]* | |

| FDG-PET | Decreased SUV in ipsi- and contralateral parotid glands-xerostomia | P = 0.02 | [118]* | |

| FDG-PET | Pre-treatment increased SUV-ORN | P < 0.0001 | [128]* |

Primary Tumor Characterization and Prognosis

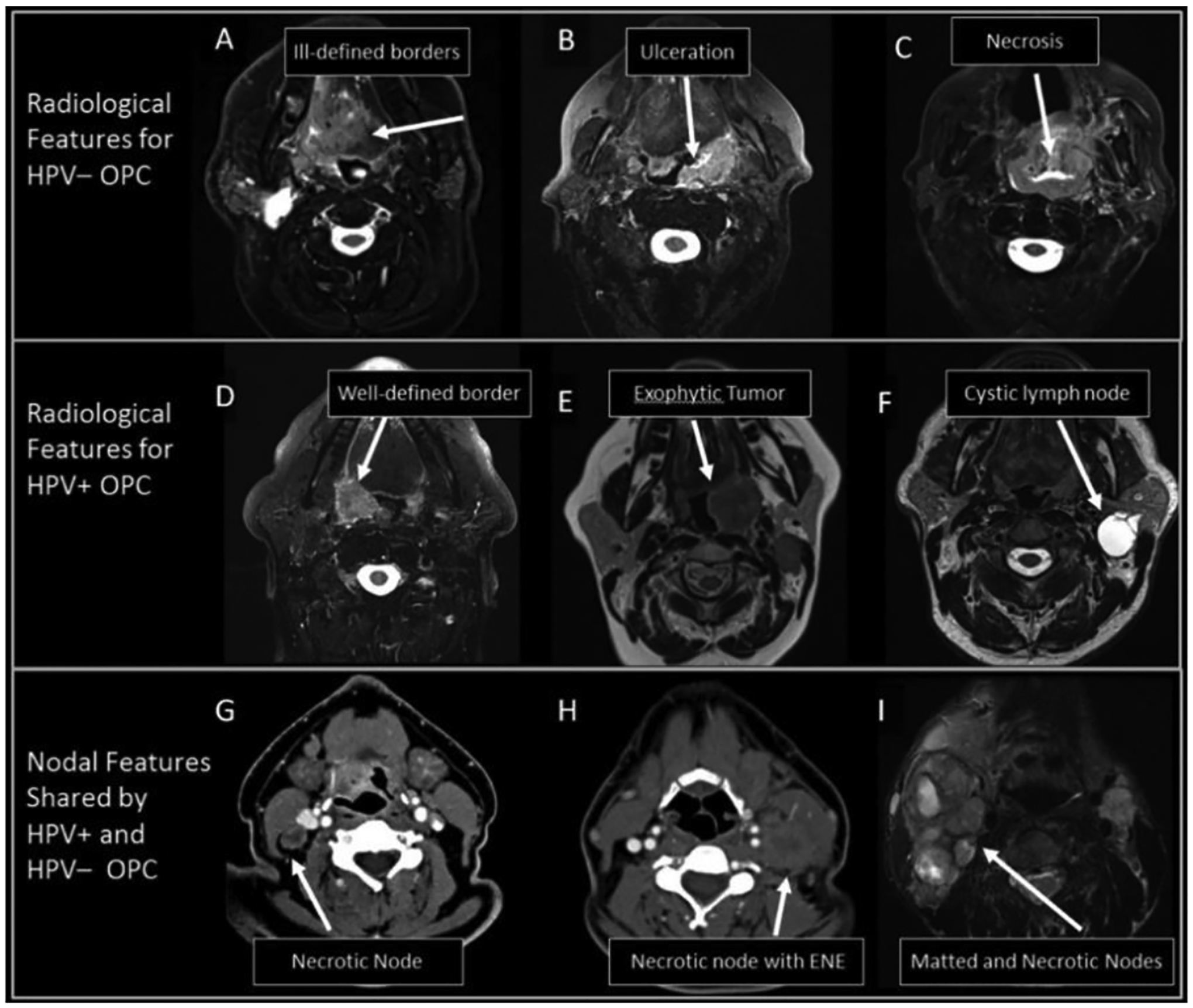

With CT and T1- and T2-weighted MRI, only the size of the primary tumor has traditionally been considered for the prognosis of OPC (i.e. T-stage). However, variations in image contrast across the tumor, known as texture features, may also contain valuable information related to its phenotype. In a comprehensive study of the radiologic appearance of HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPC tumors, Chan et al. reported HPV-positive OPC primary tumors were smaller in size at presentation, more likely to be exophytic, and less likely to display ulceration or necrosis compared with HPV-negative tumors (Fig. 1) [24]. Similar features were identified by Cantrell et al. who characterized HPV-positive OPC tumors as exophytic with well-defined borders and HPV-negative tumors as more likely to possess ill-defined borders and invade into neighboring muscle [25]. The application of quantitative radiomics models, which have robust detection power, may serve as attractive alternative approaches toward determining HPV status of OPC. These models can discriminate HPV-positive from HPV-negative OPC primary tumors when comparing geometric radiomics features from CT images which described by smaller and less complex tumors [26], [27] and more homogeneous CT density [28], [29]. Similar radiomic features were observed in HPV-positive OPC tumors when analyzing images acquired with T1-weighted MRI [30].

Figure 1:

Representative examples of radiographic features that have been useful for characterizing HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPC and associated lymph nodes. All images are T2-weighted MRI except for panels G and H which are CT. Reproduced with permission from Head Neck, 39: 1524–1534. (2017). © 2017 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Diffusion parameters, such as ADC values, have also been investigated for their ability to classify HPV-positive OPC using DWI MRI. Nakahira et al. compared pre-treatment ADC values of HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPC for 26 patients and found that both the mean and minimum ADC were significantly lower in HPV-positive tumors compared to HPV-negative tumors [31]. A number of more recent studies have found similar results for cancers of the oropharynx, oral cavity, hypopharynx, and larynx cancers [32]–[36]. However, other researchers have found that, while the mean, median, and/or minimum ADC values of HPV-positive tumors tend to be lower than those of HPV-negative tumors, the differences were not significant in cohorts of oropharyngeal, oral cavity, maxillary sinus, and other HNC [37]–[40]. In addition to looking at whole-ROI ADC values, de Parrot et al. performed histogram analysis on the distribution of ADC values within HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPC and oral cavity cancer [34]. The authors demonstrated that HPV-positive tumors were characterized by a generally homogeneous distribution of reduced ADC values with a few small areas of high ADC, whereas HPV-negative tumors had a more heterogeneous ADC distribution, centered around a higher mean value. The ADC histogram parameters were correlated with expected tumor histological characteristics of cell density and stromal involvement, highlighting the ability of DWI to discriminate between homogenous tumors with tightly packed cells where diffusion is highly restricted (i.e. HPV-positive HNC) and heterogeneous tumors with necrotic regions where diffusion is less restricted (i.e. HPV-negative HNC). Further investigating sub-regional differences in image features of HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPC, Suh et al. performed radiomics analyses on images acquired with DWI MRI in addition to and T1- and T2-weighted MRI [41]. Due to the high number of features in the model, interpretation was difficult, but the features that the authors deemed most relevant were mainly derived from the ADC parameter of DWI images.

Additional diffusion and perfusion properties were investigated in HPV-positive OPC using IVIM and DCE MRI, with mixed results. When measured with IVIM MRI, HPV-positive OPC demonstrated reduced diffusion and permeability but increased perfusion characteristics compared with HPV-negative OPC [42], [43]. In contrast, a histogram analysis on the distribution of DCE MRI parameters demonstrated that HPV-positive OPC and oral cavity cancer were characterized by increased permeability compared with HPV-negative tumors [44]. Furthermore, a number of other studies failed to find any significant correlations between DCE-MRI parameters and HPV status [39], [40], [45], although all of these studies were performed on cohorts with heterogeneous HNC types. Hardware and pulse sequence innovations which increase image quality in IVIM and DCE MRI should improve the ability of the diffusion and perfusion-related parameters to reliably discriminate between HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPC.

FDG-PET/CT has also been used to determine if any significant differences in glucose uptake metrics exist between HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPC. While several studies were unable to determine a substantial difference in conventional SUV metrics [46]–[50], there were a few that demonstrated that glucose uptake metrics were significantly lower in HPV-positive OPC primary tumors [43], [51], [52]. These results may be secondary to relatively low amounts of hypoxia, leading to less glucose metabolism, and subsequently decreased FDG uptake in HPV-positive primary tumors relative to HPV-negative primary tumors [52]. However, PET/CT imaging with hypoxia-sensing radioisotopes such as [18F]-misonidazole (FMISO), [18F]-fluoroazomycin arabinoside (FAZA), and [18F]-HX4 (a 2-nitroimidazole nucleoside analog) revealed no significant differences in hypoxia between HPV-positive and HPV-negative HNC [53]–[55].

Pretreatment imaging of HPV-positive HNC patients has been studied for prognostic value and outcome prediction following radiation therapy. Aerts et al. was the first to demonstrate that pre-treatment CT-based radiomics features could predict overall survival in cancer patients. The authors developed a radiomics model using data from non-small cell lung cancer patients which included an intensity, geometric, texture, and wavelength feature set, which was then validated on independent head and neck and lung cancer patient cohorts [21]. Additionally, Leijenaar et al. validated this model in an OPC patient cohort with mixed HPV status treated at Princess Margaret Cancer Center [56]. Although the model performed well in the validation set, the difference in survival curves was less pronounced than in the other validation HNC sets with predominantly HPV-negative patients. During validation studies, the authors observed that HPV screening may provide complementary information to the radiomic signature. This suggests that separate radiomics features are important between HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPC patients, and that the radiomics features (partly) identify HPV status. Similar results were observed by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Head and Neck Quantitative Imaging Working Group who demonstrated that a radiomics model based on two texture features was significantly predictive of local control in OPC cohort and to a greater extent than clinical factors such as HPV status and age [57]. Unfortunately, no comparison of clinical-radiomics composite models were presented, but it does suggest radiomics features may hold more information than HPV status alone. Lastly, Bogowicz et al. also identified image features that were associated with tumor control [28]. These image features, which were independent of those to characterize HPV status, also revealed that homogeneous CT density led to improved local control, and this model outperformed the prediction provided by clinical features.

Studies attempting to predict outcomes in HPV-associated OPC using pretreatment DWI MRI have demonstrated limited prognostic value. This is possibly due to the strong correlation of HPV status and ADC. For example, Ravanelli et al. observed that while HPV status and mean ADC were significant predictors of progression-free survival in univariate analysis, neither were significant using multivariate analysis [58]. Furthermore, when the authors split the patients into HPV-positive and HPV-negative cohorts and performed histogram analysis of the ADC distribution in the tumor, none of the parameters were significantly predictive of progression-free or overall survival in either the HPV-positive or HPV-negative group, and only ADC heterogeneity was associated with overall survival in the HPV-negative group. In a separate study, DWI MRI was not predictive of distant metastasis in either the general HNC patient cohort or when separated by HPV status [39]. In the multiparametric imaging analysis by Martens et al., improved locoregional recurrence-free survival was associated with reduced pretreatment tumor permeability in OPC using DCE MRI [43]. Reduced pretreatment tumor permeability was also associated with improved overall survival along with increased perfusion in IVIM MRI and reduced glucose uptake in FDG-PET. Further investigations confirmed that reduced glucose uptake values measured with FDG-PET resulted in improved prognosis of tumor control and survival in HPV-positive OPC [59]–[61]. Few alternative radioisotopes are used clinically for the prognosis of HNC. PET/CT imaging with FMISO and FAZA have proven effective at identifying patients with hypoxic HNC and stratifying them into groups that benefit from concomitant treatment with the hypoxia-activated prodrug, tirapazamine, or radiosensitizer, nimorazole, respectively, in chemoradiation regimens [54], [62]. When identifying patients with pretreatment hypoxia using FMISO, those with HPV-negative tumors demonstrated a significant improvement in survival following concomitant treatment with nimorazole [53], which was also observed in histologically-confirmed HPV-negative patients in the DAHANCA 5 trial [63]–[65]. These improvements were not as impactful for hypoxic HPV-positive patients, likely due to its generally superior prognosis.

Lymph Node Characterization and Prognosis

CT and T1- and T2-weighted MRI are traditionally used to investigate the pathologic involvement of the contralateral, cervical, ipsilateral, and retropharyngeal nodes. This is important when considering whether aggressive treatment is necessary as the retropharyngeal nodes are proximal to radiosensitive structures, and high doses of radiation lead to late-stage toxicities. In a study by Tang et al, there was no significant difference between the number of HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPC tumors that spread to the retropharyngeal nodes [66]. When investigating specific image features of these nodal metastases, it was found that clustered and cystic nodal metastases are associated with HPV-positive OPC tumors whereas necrotic nodal metastases are more characteristic of HPV-negative OPC tumors [24], [25], [67]–[69]. To determine if these nodal imaging features were prognostic, Huang et al. developed a multivariate logistical regression model from 98 OPC patients to identify patterns of chemoradiation treatment failure [67]. The presence of necrotic nodal metastases was a positive independent predictor of regional failure. Advanced nodal stage (N-stage) was a positive independent predictor of distant failure, while the presence of cystic nodal metastases was a negative independent predictor. Interestingly, HPV-status was not found to be a significant independent predictor of regional or distant failure. However, the presence of matted nodes (3 nodes abutting one another with loss of intervening fat plane), which was reported in both HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPC [24], was prognostic of poor outcome with significantly lower disease-specific survival and overall survival as well as increased risk of distant metastasis in HPV-positive OPC [70], [71].

High FDG-uptake values in metastatic nodes have been shown to be characteristic of HPV-positive patients relative to HPV-negative patients [49], [72], possibly indicating a more complex underlying relationship between HPV biology and metabolic profile within primary and metastatic lesions. These results are important since determining the characteristics of HPV-positive metastatic lymph nodes for cancers of unknown origin through FDG-PET/CT could help localize the primary tumor to the oropharynx and guide further intervention. In a study by Sharma et al. [46], the authors determine the homogeneity of FDG uptake values by subtracting the average nodal values from the primary lesion values and reveal a significant difference between the homogeneity of lesions depending on HPV status. Specifically, the authors determined a higher degree of intra-individual homogeneity of FDG-uptake in HPV-positive patients, which was suggested to be related to more homogenously triggered carcinogenesis in HPV-positive OPC compared to mutation-driven carcinogenesis in HPV-negative OPC.

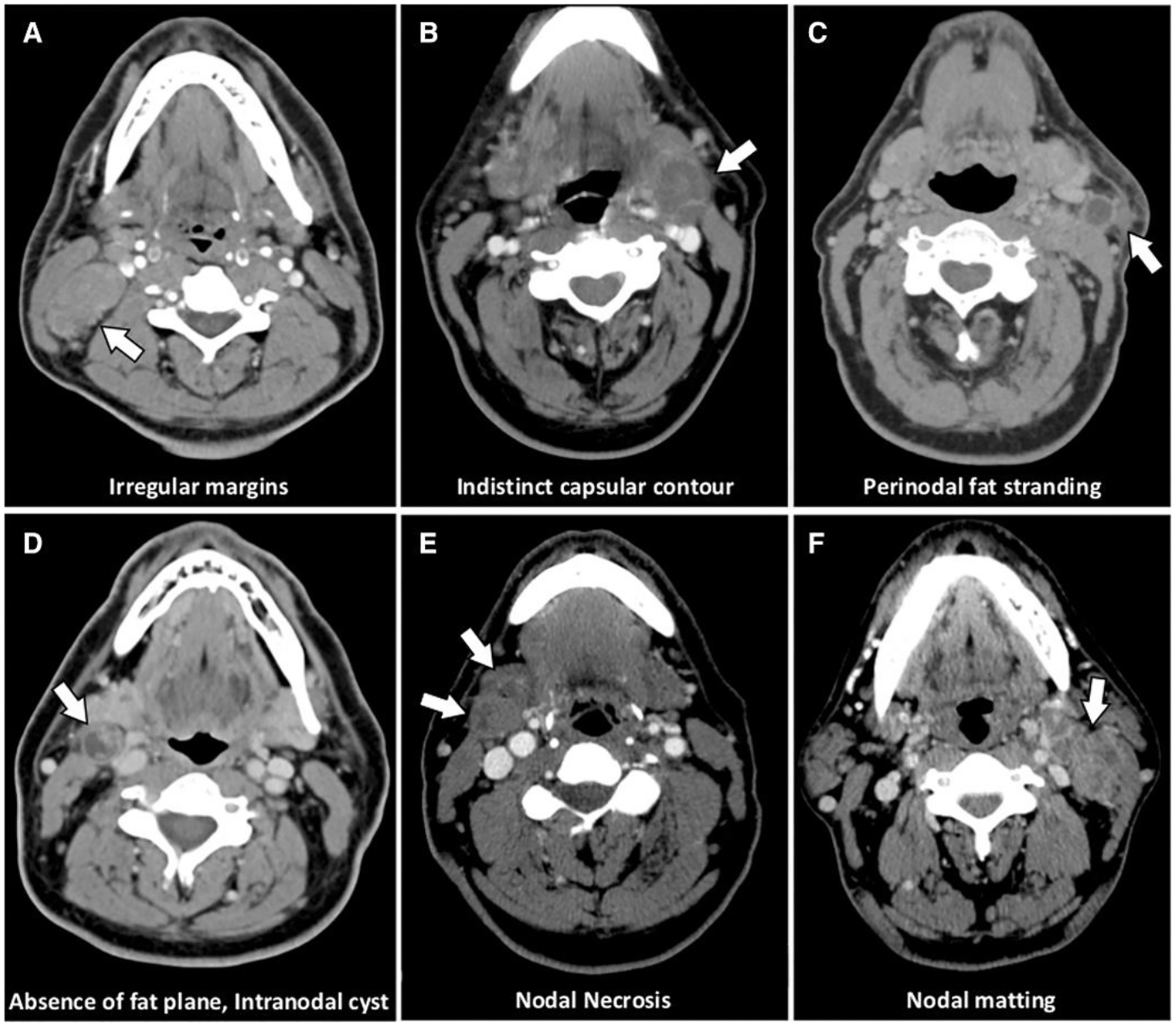

In addition to the radiologic characterization of nodal disease, there has been a large effort to radiographically diagnose extranodal extension (ENE), also known as extracapsular spread in order to appropriately stage OPC. ENE is defined as “the extension of tumor outside the capsule of a lymph node and into the perinodal soft tissue” [73]. Routine imaging with CT and T1- and T2-weighted MRI results in poor sensitivity and moderate-to-high specificity for radiographic ENE diagnosis, which is ultimately reviewer-dependent. Recently, there have been investigations to determine if there is any improvement of ENE diagnosis associated with HPV-positive OPC. In a comprehensive study, Faraji et al. evaluated the utility of several imaging features for diagnosing ENE on contrast-enhanced CT images of HPV-positive OPC [74]. Radiologic examples of these features are shown in Fig. 2. Individually, irregular lymph node margins and the absence of a perinodal fat plane were both significantly associated with ENE. Irregular margins possessed poor sensitivity (36%) but excellent specificity (95%), while absence of perinodal fat plane possessed excellent sensitivity (92%) but poor specificity (42%). The combination of both features was also significantly predictive of ENE, producing a sensitivity of 23% and specificity of 96%. Notably, the presence of nodal matting predicted ENE with a specificity of 95%. Additional studies have also reported poor sensitivity but high specificity for the diagnosis of ENE with CT in HPV-positive OPC, though their utility in the clinic is debated [75]–[78]. Park et al. recently published a meta-analysis of 22 articles, comprising of 2,478 HNC patients, which assessed the diagnostic potential of CT and MRI for ENE [79]. The authors included a sub-analysis of HPV-positive OPC, which only included CT exams. Pooled sensitivity and specificity for these exams were 65% and 74%, respectively, and specificity was significantly lower in HPV-positive OPC than the pooled specificity for HPV-negative OPC and all other HNC. Thus, while CT and MRI may not be useful screening modalities for ENE, they still possess value for the confirmation of diagnosis of suspected lesions. There is an opportunity space for significantly improving the sensitivity and specificity of ENE diagnosis in HPV-positive OPC with advanced functional imaging techniques such as DWI, DCE, or PET/CT.

Figure 2:

Contrast-enhanced CT images of various nodal imaging features that are commonly associated with extranodal extension. Reproduced with permission from Laryngoscope, 130: 1479–1486 (2019). © 2019 The American Laryngological, Rhinological and Otological Society, Inc.

Tumor Treatment Response

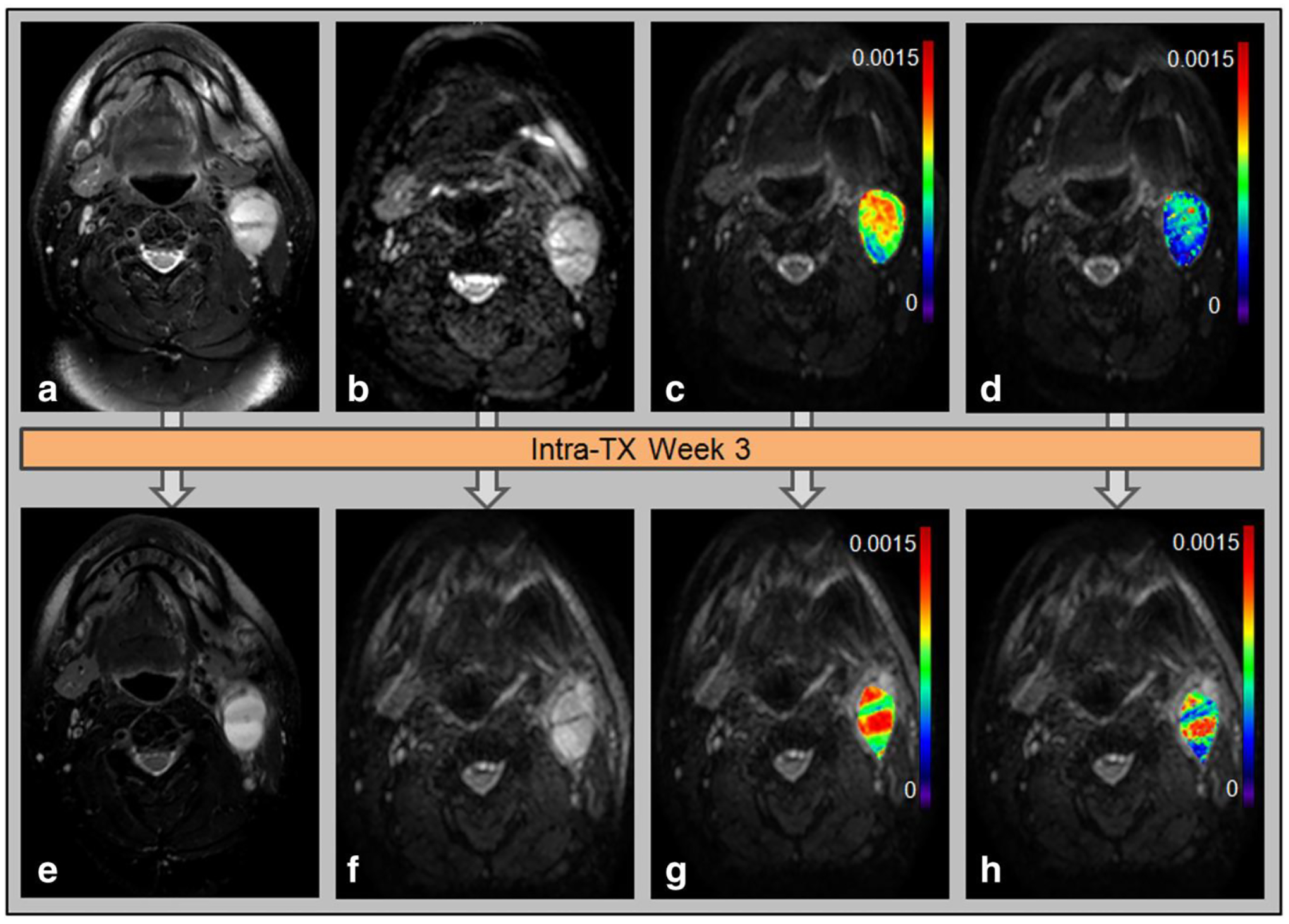

Current standard-of-care for measuring tumor response to therapy follows the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), which relies on anatomic imaging such as CT and MRI to detect the number of lesions and measure changes in tumor size [80]. Standardization and accessibility of functional and quantitative imaging techniques are still below the threshold to be considered in these criteria. The exception is FDG-PET, which can be used as an adjunct for evaluation [81]. Therefore, continued research in functional and quantitative imaging techniques for treatment response is warranted. Additionally, analytical techniques of anatomic imaging such as radiomics and AI will eventually need to be considered for RECIST criteria. In a cohort of HPV-positive OPC patients, Miller et al. demonstrated that a model which incorporated CT radiomic texture features and RECIST criteria for assessing tumor response to induction chemotherapy significantly outperformed conventional methods of measuring changes in tumor size. Quantitative MRI techniques such as DWI, IVIM, and DCE MRI can provide information about the functional properties and underlying physiology of tissues. Furthermore, functional changes in tumors over the course of treatment, such as the breakdown of tumor cell membranes or the disruption of tumor vasculature, may be quantified by acquiring DWI, IVIM, or DCE MRI scans throughout therapy and measuring differences in the values of the associated imaging biomarkers from pre-treatment scans. In a prospective study of 31 HPV-positive OPC patients, Ding et al. observed significant increases in diffusion parameters from IVIM MRI in patients with mid-therapy complete response, and these parameters could accurately discriminate between patients with and without mid-treatment complete response [82]. These results were confirmed in a rigorous study by Paudyal et al. who demonstrated that IVIM diffusion parameters significantly increased each week from pre- to mid-therapy in complete responders (Fig. 3) [83]. These diffusion parameters did not change significantly in non-complete responders and actually decreased mid-therapy. Thus, diffusion parameters measured with IVIM may provide oncologists the information to identify non-responders early in the radiation therapy regimen.

Figure 3:

Representative case of HPV-positive OPC patient who underwent imaging pre-treatment (top row) and mid-treatment at 3 weeks (bottom row) and showed complete response following chemoradiation. The tumor is imaged with T2-weighted MRI (a,e) and DWI MRI (b,f). The DWI parameter maps ADC (c,g) and D (d,h) are also displayed. Reproduced from J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, 45: 1013–1023 (2017). (Open Access)

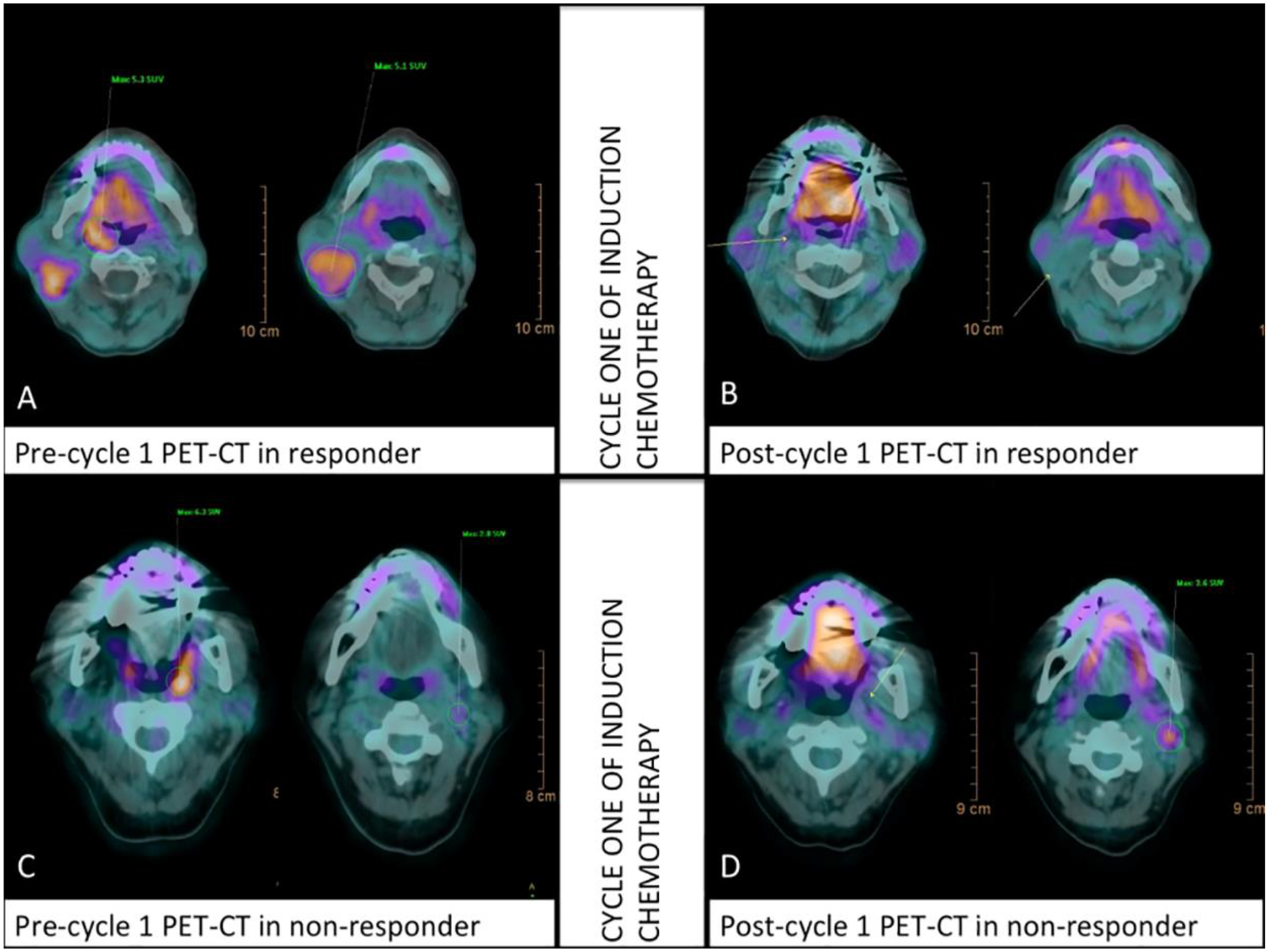

FDG-PET/CT imaging has been proposed as a method for determining intra- and post-treatment therapy response (Fig. 4). This is particularly exciting because studies have demonstrated that metabolic response measured by relatively non-invasive PET/CT imaging can act as a surrogate for histopathologic response, with superior subsequent long-term prognosis in responders than non-responders [18]. For example, Ng et al. demonstrated patients who achieved complete metabolic response on post-treatment FDG-PET/CT imaging of HPV-positive patients had an excellent prognosis with five-year disease-free survival and overall survival rates of 91% and 89%, respectively [84]. Moreover, Lin et al. demonstrated that volumetric nodal metabolic response identified on PET/CT at mid-treatment could identify a subgroup of HPV-positive OPC patients at low risk of locoregional-failure but at a higher risk of distant metastatic failure [85]. Lastly, using non-FDG PET/CT imaging, Sanduleanu et al. observed that HNC patients with increased uptake of hypoxia-sensing radioisotope [18F]-HX4 at mid-therapy suffered significantly worse progression-free and overall survival compared with patients whose [18F]-HX4 uptake remained stable or decreased [55].

Figure 4:

FDG PET/CT images of OPC patients who experienced complete response (A,B) and non-response (C,D) from induction chemotherapy at Day 14. The responding patient also displayed complete metabolic response through the reductions in primary tumor SUV (5.3 to 0.0) and lymph node SUV (5.1 to 0.0). The non-responding patient displayed reductions in primary tumor SUV but increases in lymph node SUV (2.8 to 3.6). Reproduced from PLOS ONE, 13: e0200823 (2018). (Open Access).

Historically, whole-body FDG-PET/CT has been used for surveillance imaging (recurrence, distant metastasis) of HNC, demonstrating exceptionally high sensitivity (87.5%) and specificity (95%) for detection of distant metastases [86]. Interestingly, distant metastases among HPV-positive OPC patients have been shown to have higher tendency to disseminate to multiple organs and unusual sites when compared to HPV-negative patients [18], [87]. Su et al. demonstrated that a large portion of distant metastases in HPV-positive patients were detected by FDG-PET/CT, suggesting routine surveillance imaging should be further investigated for these patients [88]. Many centers implement PET/CT imaging for surveillance at an interval of 12 weeks after therapy for HNC malignancies [89], as this time-point has been shown to be associated with disease-free survival and overall survival on multivariable analysis [90]. However, this is a large point of contention, as many studies have reported poor positive predictive value (PPV) for PET/CT in assessing disease recurrence and survival in HPV-related HNC [91]–[99]. Reported PPV for PET/CT after standard treatment ranged from as low as 13.4% [97] to 66.7% [92]. The poor PPV of PET/CT appears in part driven by persistence of residual FDG-avidity within lymph nodes [100], which is supported by findings that many complete metabolic responses occur at 16 weeks or later, rather than the typical 12 week follow-up interval [94], [95]. Another likely contributor to the poor PPV of many of these studies is the dearth of true recurrences, which may be due in part due to the radiosensitive nature of HPV-positive OPC. Radiation therapy dosing may also influence the predictive capability of PET/CT, according to a recent trial of dose de-escalation to 60 Gy [98]. In this trial, follow-up PET/CT showing equivocal or incomplete response had a PPV of only 9% [98]. Considering the evidence to date, current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommendations do not regard positive FDG-PET during follow-up as definitive evidence of recurrence, and guidelines recommend follow-up surveillance in 3–6 months or biopsy confirmation prior to surgical or therapeutic intervention [101]. Thus, rather than predicting recurrence, PET/CT may be more useful for ruling out recurrence. PET/CT has a high negative predictive value in both primary and nodal sites, approaching 100% in many studies. Therefore, in the setting of a clinical response, the NCCN recommends observation for PET/CT exams that are negative for recurrence at initial follow-up [101].

One of the pitfalls of post-treatment PET/CT for prediction of recurrence has been lack of consistent interpretation. For instance, different FDG-uptake thresholds have been used by various groups, even sometimes between studies from the same group [99], [102]. Recent work has argued for implementation of the Hopkins 5-point system [103] or Deauville criteria Likert scale [104], though these systems do not rely on a specific, objective SUV threshold. Ultimately, the use of quantitative FDG-PET features may allow for better standardization, comparison between institutional studies, and automated approaches for predictive modeling. Another major point of contention regarding the usage of PET/CT during surveillance of HPV-related HNC is whether the images meaningfully change post-treatment management. Surveillance scans lead to interventions in a fraction of cases, ranging in studies from 1.6% [97] to 12.6% [96]. Therefore, it is unclear overall if the benefit of the current standard surveillance approach outweighs risk and cost. For instance, the evidence of high false positive rate of PET/CT at 12 weeks in HPV-related HNC suggests that a delay in initial surveillance imaging to later than 16 weeks may be beneficial [94], [95]. In the current paradigm, many of these false positive cases would necessitate additional surveillance imaging and possibly unnecessary biopsies or neck dissections. Finally, it is unclear whether surveillance using PET/CT will be the most appropriate approach in the future, particularly in light of recent data using HPV circulating tumor DNA, which appears to have much better PPV for recurrence [105], [106].

Normal Tissue Toxicity Assessment and Treatment De-escalation

The combination of increased incidence, diagnosis at younger age, and prognostic improvement of HPV-positive OPC means that toxicity management of HPV-positive OPC survivors is becoming increasingly important. Initial studies qualitatively assessed the appearance of CT and T1- and T2-weighted MRI to detect the appearance and timing of various radiation-induced toxicities (osteoradionecrosis, fibrosis, inflammation-associated edema, etc.) and to distinguish them from residual/recurrent tumor [107]–[109]. Recent studies have attempted to quantify normalized signal intensity (SI) changes in T1- and T2-weighted MR images in normal tissue structures throughout and following radiation therapy of HNC and associate them with biological changes [110]–[112]. In each of these studies, normalized T2 SI in the pharyngeal constrictor muscles increased in a dose-dependent manner and was significantly higher at mid- or post-therapy, which was associated with acute edema. Furthermore, these imaging changes were identified in patients who developed radiation-induced dysphagia, which was characterized by pharyngeal constrictor doses of 50–60 Gy [110], [111], [113]. These findings were supplemented by observations that T1 SI of pharyngeal constrictors and the sternocleidomastoid muscles significantly decreased throughout therapy, representative of fibrosis, [111], [112] while SI of swallowing muscles in general significantly increased on T1 post-contrast MRI [110]. Lastly, analysis of the modified barium swallow, which is imaged with videofluoroscopy, has been recently improved by Hutcheson et al. using contrast agent-containing boluses and a 5-point grade, compatible with Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, to functionally grade radiation-induced dysphagia for organ-preserving trials [114]. This analysis, known as Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity (DIGEST), grades two components of swallowing (safety and efficiency), and it has demonstrated the ability to reliably assess pharyngeal pathophysiology, swallow efficiency, perceived dysphagia, and oral intake with substantial inter-rater agreement of κ = 0.67. As these imaging techniques for assessing organ function continue to improve, radiation therapy strategies should find success at reducing toxicities during treatment of HPV-positive OPC.

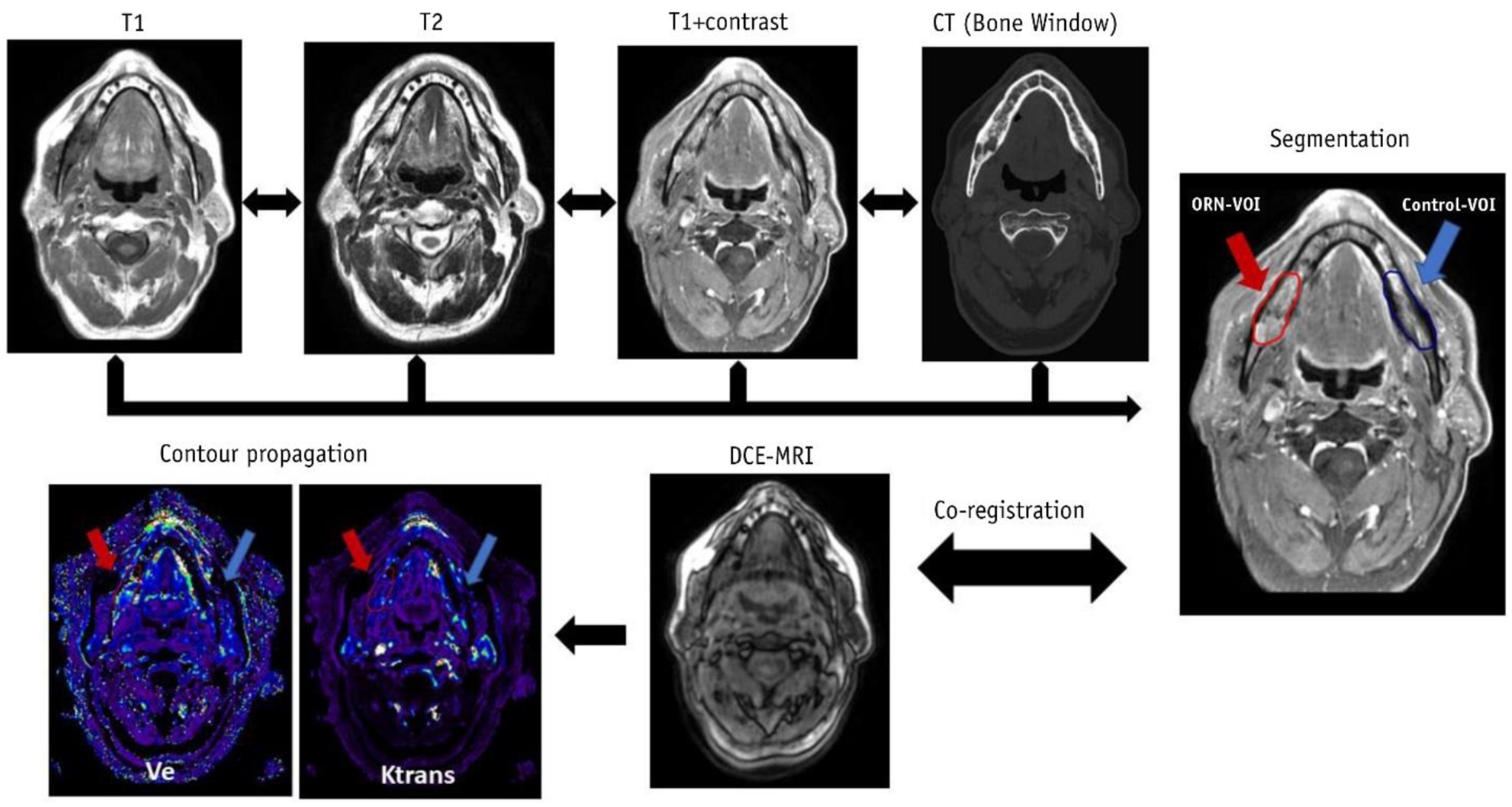

Recent investigations studying the utility of DCE-MRI to predict and measure the extent of ORN, a relatively rare, yet severe late toxicity related to radiation therapy, have been promising, in which permeability and perfusion parameters were demonstrated to vary in a dose-dependent relationship [115]. Furthermore, these DCE parameters were significantly increased in ORN-affected mandible compared with healthy contralateral mandible (Fig. 5) [116]. Despite the limited number of studies with this technique, DCE-MRI appears to be a useful modality for the early diagnosis of ORN.

Figure 5:

Incorporation of multiparametric imaging to identify changes associated with osteoradionecrosis. Reproduced with permission from Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., 108: 1319–1328 (2020). © 2020 Elsevier Inc.

As early as 1998, investigators have turned to FDG-PET/CT imaging in HNC to aid in the assessment of toxicity-related sequelae [117]. However, the literature on this topic has remained relatively sparse over the years. Recently, a series of studies by Elhalawani et al. have attempted to predict the severity of toxicity-related side effects, such as xerostomia and dysphagia, in OPC patients [118], [119]. In both of these studies, using pre- and post-treatment FDG-PET/CT, the authors discovered dose-dependent changes in longitudinal kinetics of PET-derived metrics. In particular, FDG uptake values of the parotid glands decreased following radiation therapy, compared to baseline values, which corresponded to more severe xerostomia symptoms. In contrast, increased FDG uptake values after radiation therapy were observed for all muscular structures that contributed to dysphagia, presumably due to inflammation. The FDG uptake value of the inferior constrictor muscle was an important component of a predictive model for dysphagia severity. These studies demonstrate that FDG-PET imaging metrics could serve as eventual biomarkers for patient toxicity risk stratification.

As already noted, FDG-PET/CT imaging is used for the assessment of recurrent tumors in HNC. However, image interpretation may lead to challenges deciphering between non-malignant conditions, such as inflammation, and malignancy which may appear similar. One notable example relevant for this discussion is misidentification of ORN of the mandible for tumor recurrence [120]. ORN forms approximately 10% of increased osseous uptake in HNC compared to residual tumor, disease recurrence, and benign causes such as dental infection [121]. Various case reports have identified avid FDG-uptake in areas of ORN, yielding false positive results for tumor recurrences [122]–[124]. Specifically, there is considerable overlap of FDG uptake in areas of ORN and tumor recurrence, with SUVmax values reported as high as 17.4 for ORN in areas of the ramus [123]. While it has been suggested that CT should be preferred for differentiation of these pathologies [125], a possible alternative is dual-phase semi-quantitative FDG-PET, where a variable washout time can lead to the differentiation of uptake from benign or malignant lesions [126]. Interestingly, while FDG-PET/CT can lead to false positives in the differentiation of recurrence from ORN, some studies have suggested using FDG-PET/CT in the analysis of ORN. For example, Akashi et al. demonstrated that variable FDG uptake localization in ORN with different treatment outcomes, indicating that post-treatment follow up with FDG-PET/CT could be useful for early detection and assessment of ORN [127]. While periodontal conditions are typically diagnosed by dental professionals using more conservative imaging modalities (i.e. intraoral dental x-rays), it has been suggested that PET/CT could be used to identify periodontitis in HNC, which could be used to predict future development of ORN [128].

As a means to guide decision-making between tumor control and toxicity management, the addition of FDG-PET/CT imaging data to improve de-escalation results has been the subject of much speculation [129], [130]. Studies have highlighted the viability of using mid-therapy PET/CT tumor response as patients with more pronounced metabolic response have better long-term locoregional control [131]–[133]. A few currently planned and ongoing clinical trials seek to use FDG PET/CT imaging to help identify HNC patients with favorable treatment response for dose de-escalation (NCT02442375, NCT03210103, NCT03972072, NCT04667585). The results of these trials will help shed light on the utility of PET/CT for dose de-escalation in HPV-positive patients. Dose painting, where areas of tumors can be targeted with variable doses based on radiation sensitivity, is a prime application space where FDG-PET/CT imaging has the potential to improve dose-escalation and de-escalation and warrants future investigation.

Conclusion and Future Directions

There are many imaging techniques utilized in diagnostic imaging that have the potential to translate to applications in radiation oncology. Tissue-specific imaging with dual-energy CT and photon-counting CT offer improvements in contrast compared with conventional CT techniques. Additional functional MRI techniques such as relaxometry, chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST), and MR-elastography provide valuable physiologic information that could help identify early tumor and normal tissue response at mid-therapy exams or differentiate between inflammation and residual tumor or recurrence during post-therapy and follow-up exams. The same could be said about the plethora of radioisotope tracers that are currently in development, which can detect the up- or downregulation of specific cellular processes that are characteristic of viable cancer cells. Correlations between pre-treatment imaging biomarker values and treatment response are potentially useful in identifying patients with treatment-resistant tumors who may be candidates for dose escalation, or conversely, dose de-escalation for tumors more likely to respond. As these imaging techniques continue to be clinically validated in diagnostic imaging, we predict that there will be a great opportunity to utilize these novel techniques for impactful radiation oncology research and practice.

In the short-term, advances in AI and radiomics will continue to provide a compelling argument for integration with physician review through decision support tools. Probabilities of tumor phenotypes or indications of response, whose image patterns are not detectable by human review would provide a great wealth of information that may lead to improvements in personalized care. Continued improvements in imaging technology to efficiently and reliably acquire imaging data are important steps to unlocking the full potential of these techniques. One specific example is the mitigation of artifacts that routinely arise in head and neck imaging due to dental implants, which distorts the visualization of surrounding anatomy. Furthermore, improved resolution and signal-to-noise are imperative for the precise imaging required in radiation oncology. One recent engineering feat is the clinical implementation of hybrid MRI-linear accelerator (MR-Linac) systems for radiation therapy, which introduces the possibility of acquiring serial quantitative MRI during radiation therapy and tracking daily changes to monitor treatment response [134]–[136]. Ultimately, we may be able to leverage this novel technology to provide personalized, biologically adapted radiation therapy, such as dose escalation or de-escalation based on mid-therapy response. Ultimately, we believe that further investment into imaging research which builds on the presented findings will lead to the formation of ideal radiation therapy strategies for maximal tumor control with minimal radiation-induced toxicities.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Cancer Center Support Grant (P30-CA016672-44). TCS and KAW are supported by training fellowships from The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences TL1 Program (TL1TR003169). ASRM and SYL are supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) Award (R01DE025248). BAM receives research support from the NIH NIDCR (F31DE029093) and the Dr. John J. Kopchick Fellowship through MD Anderson UTHealth Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences. C.D. Fuller received funding from an NIH NIDCR Award (1R01DE025248-01/R56DE025248) and Academic-Industrial Partnership Award (R01 DE028290), the National Science Foundation (NSF), Division of Mathematical Sciences, Joint NIH/NSF Initiative on Quantitative Approaches to Biomedical Big Data (QuBBD) Grant (NSF 1557679), the NIH Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Early Stage Development of Technologies in Biomedical Computing, Informatics, and Big Data Science Award (1R01CA214825), the NCI Early Phase Clinical Trials in Imaging and Image-Guided Interventions Program (1R01CA218148), the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) Pilot Research Program Award from the UT MD Anderson CCSG Radiation Oncology and Cancer Imaging Program (P30CA016672), the NIH/NCI Head and Neck Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) Developmental Research Program Award (P50 CA097007) and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) Research Education Program (R25EB025787). He has received direct industry grant support, speaking honoraria and travel funding from Elekta AB.

Abbreviations:

- HPV

Human papillomavirus

- OPC

Oropharyngeal cancer

- ENE

Extranodal extension

- HNC

Head and neck cancer

- CT

Computed tomography

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- SI

Signal intensity

- DCE

Dynamic contrast-enhanced

- DWI

Diffusion-weighted imaging

- IVIM

Intra-voxel incoherent motion

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- FDG

2–18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Deschuymer S, Mehanna H, and Nuyts S, “Toxicity Reduction in the Treatment of HPV Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer: Emerging Combined Modality Approaches,” Front. Oncol, vol. 8, Oct. 2018, doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pfister DG et al. , “Head and Neck Cancers, Version 2.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology,” J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw, vol. 18, no. 7, pp. 873–898, Jul. 2020, doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Seiwert TY et al. , “OPTIMA: a phase II dose and volume de-escalation trial for human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer,” Ann. Oncol, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 297–302, Feb. 2019, doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chen AM et al. , “Reduced-dose radiotherapy for human papillomavirus-associated squamous-cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: a single-arm, phase 2 study,” Lancet Oncol, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 803–811, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30246-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].NRG Oncology, “Reduced-dose Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy With or Without Cisplatin in Treating Patients With Advanced Oropharyngeal Cancer.” https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT02254278.

- [6].Mayo Clinic, “Evaluation of De-escalated Adjuvant Radiation Therapy for Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-Associated Oropharynx Cancer,” [Online]. Available: https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT02908477.

- [7].Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, “Major De-escalation to 30 Gy for Select Human Papillomavirus Associated Oropharyngeal Carcinoma,” [Online]. Available: https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT03323463.

- [8].Ang KK et al. , “Human Papillomavirus and Survival of Patients with Oropharyngeal Cancer,” N. Engl. J. Med, vol. 363, no. 1, pp. 24–35, Jul. 2010, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Di Gravio EJ et al. , “Modern treatment outcomes for early T-stage oropharyngeal cancer treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy at a tertiary care institution,” Radiat. Oncol, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 261, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1186/s13014-020-01705-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lassen P et al. , “Prognostic impact of HPV-associated p16-expression and smoking status on outcomes following radiotherapy for oropharyngeal cancer: The MARCH-HPV project,” Radiother. Oncol, vol. 126, no. 1, pp. 107–115, Jan. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Charles-Edwards EM, “Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and its application to cancer,” Cancer Imaging, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 135–143, 2006, doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2006.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Driessen JP et al. , “Diffusion-weighted MR Imaging in Laryngeal and Hypopharyngeal Carcinoma: Association between Apparent Diffusion Coefficient and Histologic Findings,” Radiology, vol. 272, no. 2, pp. 456–463, Aug. 2014, doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, Aubin ML, Vignaud J, and Laval-Jeantet M, “Separation of diffusion and perfusion in intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging.,” Radiology, vol. 168, no. 2, pp. 497–505, Aug. 1988, doi: 10.1148/radiology.168.2.3393671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Le Bihan D, “What can we see with IVIM MRI?,” Neuroimage, vol. 187, no. September 2017, pp. 56–67, Feb. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tofts PS et al. , “Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T1- weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: Standardized quantities and symbols,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 223–232, 1999, doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wong WL and Sanghera B, “Recent Advances in Technology,” in Scott-Brown’s Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, 8th ed., Watkinson JC and Clarke RW, Eds. CRC Press, 2018, pp. 541–558. [Google Scholar]

- [17].V Liberti M and Locasale JW, “The Warburg Effect: How Does it Benefit Cancer Cells?,” Trends Biochem. Sci, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 211–218, Mar. 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Subramaniam RM, Alluri KC, Tahari AK, Aygun N, and Quon H, “PET/CT Imaging and Human Papilloma Virus-Positive Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Cancer: Evolving Clinical Imaging Paradigm,” J. Nucl. Med, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 431–438, Mar. 2014, doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.125542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Vaupel P, Thews O, and Hoeckel M, “Treatment Resistance of Solid Tumors,” Med. Oncol, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 243–260, 2001, doi: 10.1385/MO:18:4:243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, and Hricak H, “Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data,” Radiology, vol. 278, no. 2, pp. 563–577, Feb. 2016, doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Aerts HJWL et al. , “Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach,” Nat. Commun, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 4006, Sep. 2014, doi: 10.1038/ncomms5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yip SSF et al. , “Associations between radiologist-defined semantic and automatically computed radiomic features in non-small cell lung cancer,” Sci. Rep, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 3519, Dec. 2017, doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02425-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lambin P et al. , “Radiomics: Extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis,” Eur. J. Cancer, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 441–446, Mar. 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chan MW et al. , “Morphologic and topographic radiologic features of human papillomavirus-related and -unrelated oropharyngeal carcinoma,” Head Neck, vol. 39, no. 8, pp. 1524–1534, Aug. 2017, doi: 10.1002/hed.24764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cantrell SC, Peck BW, Li G, Wei Q, Sturgis EM, and Ginsberg LE, “Differences in Imaging Characteristics of HPV-Positive and HPV-Negative Oropharyngeal Cancers: A Blinded Matched-Pair Analysis,” Am. J. Neuroradiol, vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 2005–2009, Oct. 2013, doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yu K et al. , “Radiomic analysis in prediction of Human Papilloma Virus status,” Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol, vol. 7, pp. 49–54, Dec. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bagher-Ebadian H et al. , “Application of radiomics for the prediction of HPV status for patients with head and neck cancers,” Med. Phys, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 563–575, Feb. 2020, doi: 10.1002/mp.13977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bogowicz M et al. , “Computed Tomography Radiomics Predicts HPV Status and Local Tumor Control After Definitive Radiochemotherapy in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol, vol. 99, no. 4, pp. 921–928, Nov. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Leijenaar RTH et al. , “Development and validation of a radiomic signature to predict HPV (p16) status from standard CT imaging: a multicenter study,” Br. J. Radiol, vol. 91, no. 1086, p. 20170498, Mar. 2018, doi: 10.1259/bjr.20170498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bos P et al. , “Clinical variables and magnetic resonance imaging-based radiomics predict human papillomavirus status of oropharyngeal cancer,” Head Neck, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 485–495, Feb. 2021, doi: 10.1002/hed.26505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Nakahira M, Saito N, Yamaguchi H, Kuba K, and Sugasawa M, “Use of quantitative diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging to predict human papilloma virus status in patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma,” Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, vol. 271, no. 5, pp. 1219–1225, May 2014, doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2641-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Payabvash S, Chan A, Jabehdar Maralani P, and Malhotra A, “Quantitative diffusion magnetic resonance imaging for prediction of human papillomavirus status in head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Neuroradiol. J, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 232–240, Aug. 2019, doi: 10.1177/1971400919849808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ravanelli M et al. , “Correlation between Human Papillomavirus Status and Quantitative MR Imaging Parameters including Diffusion-Weighted Imaging and Texture Features in Oropharyngeal Carcinoma,” Am. J. Neuroradiol, vol. 39, no. 10, pp. 1878–1883, Oct. 2018, doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].de Perrot T, Lenoir V, Domingo Ayllón M, Dulguerov N, Pusztaszeri M, and Becker M, “Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Histograms of Human Papillomavirus–Positive and Human Papillomavirus–Negative Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Assessment of Tumor Heterogeneity and Comparison with Histopathology,” Am. J. Neuroradiol, vol. 38, no. 11, pp. 2153–2160, Nov. 2017, doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Driessen JP et al. , “Correlation of human papillomavirus status with apparent diffusion coefficient of diffusion-weighted MRI in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas,” Head Neck, vol. 38, no. S1, pp. E613–E618, Apr. 2016, doi: 10.1002/hed.24051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Martens RM et al. , “Predictive value of quantitative diffusion-weighted imaging and 18-F-FDG-PET in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated by (chemo)radiotherapy,” Eur. J. Radiol, vol. 113, no. December 2018, pp. 39–50, Apr. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kawaguchi M et al. , “Comparison of Imaging Findings between Human Papillomavirus-positive and - Negative Squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Maxillary Sinus,” J. Clin. Imaging Sci, vol. 10, no. 59, p. 59, Oct. 2020, doi: 10.25259/JCIS_116_2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schouten CS et al. , “Quantitative Diffusion-Weighted MRI Parameters and Human Papillomavirus Status in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma,” Am. J. Neuroradiol, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 763–767, Apr. 2015, doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chawla S et al. , “Prediction of distant metastases in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck using DWI and DCE-MRI.,” Head Neck, vol. 42, no. 11, pp. 3295–3306, Nov. 2020, doi: 10.1002/hed.26386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Han M, Lee SJ, Lee D, Kim SY, and Choi JW, “Correlation of human papilloma virus status with quantitative perfusion/diffusion/metabolic imaging parameters in the oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: comparison of primary tumour sites and metastatic lymph nodes,” Clin. Radiol, vol. 73, no. 8, pp. 757.e21–757.e27, Aug. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Suh CH et al. , “Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: radiomic machine-learning classifiers from multiparametric MR images for determination of HPV infection status,” Sci. Rep, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 17525, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74479-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Vidiri A et al. , “Intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion-weighted imaging for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: Correlation with human papillomavirus Status,” Eur. J. Radiol, vol. 119, no. July, p. 108640, Oct. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Martens RM et al. , “Multiparametric functional MRI and 18F-FDG-PET for survival prediction in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated with (chemo)radiation,” Eur. Radiol, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 616–628, Feb. 2021, doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Choi YS, Park M, Kwon HJ, Koh YW, Lee S-K, and Kim J, “Human Papillomavirus and Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor in Oral Cavity and Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Correlation With Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI Parameters,” Am. J. Roentgenol, vol. 206, no. 2, pp. 408–413, Feb. 2016, doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.14713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Jansen JFA et al. , “Correlation of a priori DCE-MRI and 1H-MRS data with molecular markers in neck nodal metastases: Initial analysis,” Oral Oncol, vol. 48, no. 8, pp. 717–722, Aug. 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sharma SJ et al. , “Intraindividual homogeneity of 18 F-FDG PET/CT parameters in HPV-positive OPSCC,” Oral Oncol, vol. 73, pp. 166–171, Oct. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Huang Y-T, Ravi Kumar AS, and Bhuta S, “18F-FDG PET/CT as a semiquantitative imaging marker in HPV-p16-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell cancers,” Nucl. Med. Commun, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 16–20, Jan. 2015, doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Goyal S et al. , “Correlation of MRI derived parameters and SUV uptake obtained from FDG- PET-CT with human papillomavirus status in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas,” Ann. Oncol, vol. 30, no. Supplement_7, p. vii34, Nov. 2019, doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz413.121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kendi ATK et al. , “Do 18F-FDG PET/CT Parameters in Oropharyngeal and Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinomas Indicate HPV Status?,” Clin. Nucl. Med, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. e196–e200, Mar. 2015, doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Samolyk-Kogaczewska N, Sierko E, Dziemianczyk-Pakiela D, Nowaszewska KB, Lukasik M, and Reszec J, “Usefulness of Hybrid PET/MRI in Clinical Evaluation of Head and Neck Cancer Patients,” Cancers (Basel)., vol. 12, no. 2, p. 511, Feb. 2020, doi: 10.3390/cancers12020511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Tahari AK, Alluri KC, Quon H, Koch W, Wahl RL, and Subramaniam RM, “FDG PET/CT Imaging of Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma,” Clin. Nucl. Med, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 225–231, Mar. 2014, doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Schouten CS et al. , “Interaction of quantitative 18 F-FDG-PET-CT imaging parameters and human papillomavirus status in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma,” Head Neck, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 529–535, Apr. 2016, doi: 10.1002/hed.23920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Trinkaus ME et al. , “Correlation of p16 status, hypoxic imaging using [18F]-misonidazole positron emission tomography and outcome in patients with loco-regionally advanced head and neck cancer,” J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol, vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 89–97, Feb. 2014, doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.12155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Mortensen LS et al. , “FAZA PET/CT hypoxia imaging in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck treated with radiotherapy: Results from the DAHANCA 24 trial,” Radiother. Oncol, vol. 105, no. 1, pp. 14–20, Oct. 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Sanduleanu S et al. , “[18F]-HX4 PET/CT hypoxia in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck treated with chemoradiotherapy: Prognostic results from two prospective trials,” Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol, vol. 23, pp. 9–15, Jul. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Leijenaar RTH et al. , “External validation of a prognostic CT-based radiomic signature in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma,” Acta Oncol. (Madr), vol. 54, no. 9, pp. 1423–1429, Oct. 2015, doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1061214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Elhalawani H et al. , “Investigation of radiomic signatures for local recurrence using primary tumor texture analysis in oropharyngeal head and neck cancer patients,” Sci. Rep, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 1524, Dec. 2018, doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14687-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ravanelli M et al. , “Pretreatment DWI with Histogram Analysis of the ADC in Predicting the Outcome of Advanced Oropharyngeal Cancer with Known Human Papillomavirus Status Treated with Chemoradiation,” Am. J. Neuroradiol, vol. 41, no. 8, pp. 1473–1479, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Tang C et al. , “Validation that Metabolic Tumor Volume Predicts Outcome in Head-and-Neck Cancer,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol, vol. 83, no. 5, pp. 1514–1520, Aug. 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Alluri KC, Tahari AK, Wahl RL, Koch W, Chung CH, and Subramaniam RM, “Prognostic Value of FDG PET Metabolic Tumor Volume in Human Papillomavirus–Positive Stage III and IV Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma,” Am. J. Roentgenol, vol. 203, no. 4, pp. 897–903, Oct. 2014, doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Chotchutipan T et al. , “Volumetric 18 F-FDG-PET parameters as predictors of locoregional failure in low-risk HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer after definitive chemoradiation therapy,” Head Neck, vol. 41, no. 2, p. hed.25505, Dec. 2018, doi: 10.1002/hed.25505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Rischin D et al. , “Prognostic Significance of [18 F]-Misonidazole Positron Emission Tomography–Detected Tumor Hypoxia in Patients With Advanced Head and Neck Cancer Randomly Assigned to Chemoradiation With or Without Tirapazamine: A Substudy of Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncol,” J. Clin. Oncol, vol. 24, no. 13, pp. 2098–2104, May 2006, doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Lassen P, Eriksen JG, Hamilton-Dutoit S, Tramm T, Alsner J, and Overgaard J, “HPV-associated p16-expression and response to hypoxic modification of radiotherapy in head and neck cancer,” Radiother. Oncol, vol. 94, no. 1, pp. 30–35, Jan. 2010, doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Overgaard J et al. , “A randomized double-blind phase III study of nimorazole as a hypoxic radiosensitizer of primary radiotherapy in supraglottic larynx and pharynx carcinoma. Results of the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Study (DAHANCA) Protocol 5–85,” Radiother. Oncol, vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 135–146, Feb. 1998, doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(97)00220-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Toustrup K, Sørensen BS, Lassen P, Wiuf C, Alsner J, and Overgaard J, “Gene expression classifier predicts for hypoxic modification of radiotherapy with nimorazole in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck,” Radiother. Oncol, vol. 102, no. 1, pp. 122–129, Jan. 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Tang C et al. , “Radiologic assessment of retropharyngeal node involvement in oropharyngeal carcinomas stratified by HPV status,” Radiother. Oncol, vol. 109, no. 2, pp. 293–296, Nov. 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Huang Y-H et al. , “Cystic nodal metastasis in patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma receiving chemoradiotherapy: Relationship with human papillomavirus status and failure patterns,” PLoS One, vol. 12, no. 7, p. e0180779, Jul. 2017, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Morani AC, Eisbruch A, Carey TE, Hauff SJ, Walline HM, and Mukherji SK, “Intranodal Cystic Changes: A potential radiological signature/biomarker to assess the HPV (human papillomavirus) status of cases with oropharyngeal malignancies,” J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 343–345, 2013, doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e318282d7c3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Goldenberg D et al. , “Cystic lymph node metastasis in patients with head and neck cancer: An HPV-associated phenomenon,” Head Neck, vol. 30, no. 7, pp. 898–903, Jul. 2008, doi: 10.1002/hed.20796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Spector ME et al. , “Matted nodes: Poor prognostic marker in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma independent of HPV and EGFR status,” Head Neck, vol. 34, no. 12, pp. 1727–1733, Dec. 2012, doi: 10.1002/hed.21997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Spector ME et al. , “Matted nodes as a predictor of distant metastasis in advanced-stage III/IV oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma,” Head Neck, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 184–190, Feb. 2016, doi: 10.1002/hed.23882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Joo Y-H et al. , “Association between the standardized uptake value and high-risk HPV in hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma,” Acta Otolaryngol, vol. 134, no. 10, pp. 1062–1070, Oct. 2014, doi: 10.3109/00016489.2014.905701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Bullock MJ et al. , “Data Set for the Reporting of Nodal Excisions and Neck Dissection Specimens for Head and Neck Tumors: Explanations and Recommendations of the Guidelines From the International Collaboration on Cancer Reporting,” Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med, vol. 143, no. 4, pp. 452–462, Apr. 2019, doi: 10.5858/arpa.2018-0421-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Faraji F et al. , “Computed tomography performance in predicting extranodal extension in HPV-positive oropharynx cancer,” Laryngoscope, vol. 130, no. 6, pp. 1479–1486, Jun. 2020, doi: 10.1002/lary.28237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Maxwell JH et al. , “Accuracy of computed tomography to predict extracapsular spread in p16-positive squamous cell carcinoma,” Laryngoscope, vol. 125, no. 7, pp. 1613–1618, Jul. 2015, doi: 10.1002/lary.25140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Geltzeiler M et al. , “Predictors of extracapsular extension in HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer treated surgically,” Oral Oncol, vol. 65, pp. 89–93, Feb. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]