Abstract

Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 are highly effective in preventing severe disease and mortality. Although pregnant women are at increased risk of severe COVID-19, vaccination uptake among pregnant women varies. We used the Swedish and Norwegian population-based health registries to identify pregnant women and to investigate background characteristics associated with not being vaccinated. In this study of 164 560 women giving birth between May 2021 and May 2022, 78% in Sweden and 87% in Norway have been vaccinated with at least one dose at delivery. Not being vaccinated while being pregnant was associated with age below 30 years, low education and income level, birth region other than Scandinavia, smoking during pregnancy, not living with a partner, and gestational diabetes. These results can assist health authorities develop targeted vaccination information to diminish vaccination inequality and prevent severe disease in vulnerable groups.

Keywords: COVID-19 vaccination uptake, Pregnancy, Register, Birth country, Education level

1. Introduction

Pregnant women are at increased risk of severe COVID-19 compared to the non-pregnant population [1] and pregnant women hospitalized due to COVID-19 are predominantly unvaccinated [2]. Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 are highly effective at preventing severe COVID-19 infection, hospitalization and mortality, both in the general population [3], [4] and in pregnant women [5]. Reduction of morbidity and mortality of COVID-19 therefore depends on the availability and uptake of vaccination [2].

Although safety data on SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations during pregnancy is limited, current growing evidence has not detected any safety signals of concern [6], [7]. Despite recommendations for pregnant women to get vaccinated, the vaccine uptake has been lower among pregnant than non-pregnant women of fertile age in several countries [8], [9], [10]. Existing studies from the UK and Israel suggest that unvaccinated pregnant women were younger [8], [10], had lower socioeconomic status [8], [10], [11] and were more often of non-white ethnicity [8] compared to vaccinated pregnant women. More knowledge about groups who are hesitant to get vaccinated while being pregnant will contribute to identify pregnant women who will benefit from targeted information.

The Swedish and Norwegian population-based registries provide a unique possibility to follow birthing women and their pregnancies as the pandemic develops. Our objective was to describe vaccine uptake in delivering women in Sweden and Norway and the background characteristics associated with vaccine coverage and vaccinations while being pregnant.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

This registry-based cohort study included women giving birth after 22 gestational weeks from May 2021 through May 2022, identified from the Swedish Pregnancy Register and the Medical Birth Register of Norway. The Swedish Pregnancy Register covers 94% of all births (18 of 21 health care regions) in Sweden, while the Medical Birth Registry of Norway includes all births.

2.2. Vaccination data

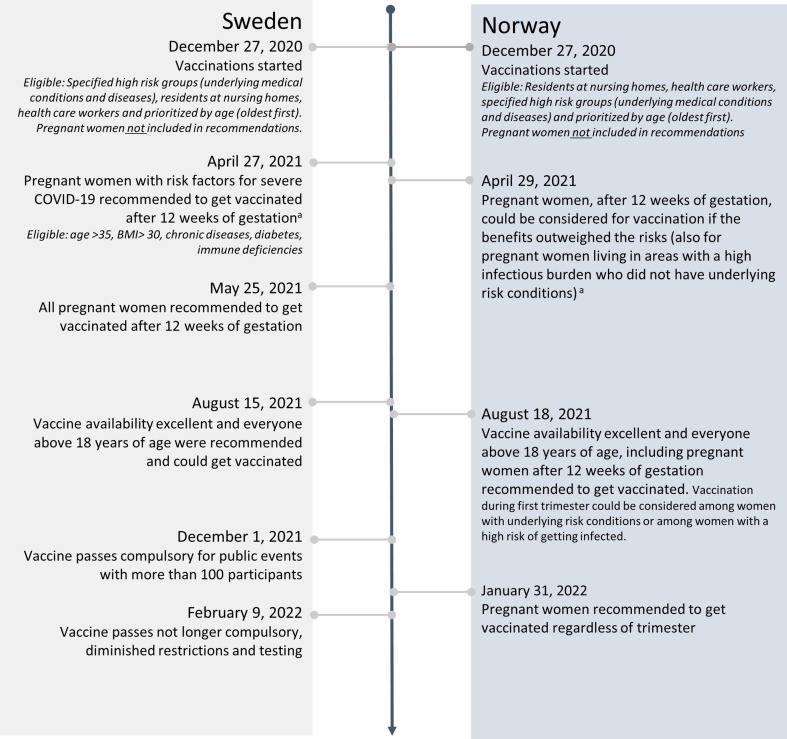

Up to end of May 2021 in Sweden and August 2021 in Norway, vaccination was only recommended to pregnant women with a high risk of severe COVID-19. Thereafter, a general recommendation for pregnant women to get vaccinated was issued, although women were recommended to wait with vaccinations to after 12 weeks of gestation. In Sweden, as availability of vaccines was restricted initially, vaccination was still being prioritized based on age (oldest first). From August 2021, however, the vaccine was available to all above 18 years of age in both countries. Since January 2022, women in Norway have been recommended vaccination regardless of trimester. A time line of vaccine recommendations is presented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Time line of vaccine recommendations in Sweden and Norway. Footnote: a Up until May 1, 2021 one pregnant individual was vaccinated in Sweden and no one in Norway.

The unique personal identity number assigned to all citizens in Sweden and Norway at birth or immigration, enabled linkage of vaccination data from the Swedish Vaccination Register at the Public Health Agency of Sweden and from the Norwegian Immunization Register held by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, to the birth registries. The number of doses, type and date of administration were identified from the vaccination registers.

Two types of mRNA vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2) and Moderna (mRNA-1273) and one viral vector vaccine from AstraZeneca (AZD1222), have been available in both Sweden and Norway. In Sweden, the AZD1222 was not recommended to individuals younger than 65 years from March 16, 2021 and not recommended to pregnant women [12]. In Norway, AZD1222 was not recommended at all after May 12, 2021 [13].

Women were regarded as vaccinated if they received at least one dose at any time before delivery (either prior pregnancy or while being pregnant). Women were defined as vaccinated while pregnant if the date of administration occurred between the estimated start of pregnancy and the date of delivery. The start of pregnancy was estimated using the date of delivery minus the estimated pregnancy length, as defined from routine ultrasound scans performed in 98% of pregnancies, or on last menstrual period if ultrasound-based estimates were missing.

2.3. Background characteristics

Background characteristics were divided into three groups: 1) maternal characteristics: including age, early pregnancy body mass index, parity, education level, income (in tertiles), region of birth, smoking status in early pregnancy and cohabitation with partner; 2) pre-pregnancy comorbidities: including diabetes, chronic hypertension, cardiovascular disease, renal disease, lung disease/asthma and thrombosis; and 3) pregnancy related factors: including pre-eclampsia/HELLP syndrome (Hemolysis, Elevated Liver Enzymes, Low platelet counts)/eclampsia, gestational diabetes and multiple pregnancy. In Sweden, education and income level were only available up until October 11, 2021 from Statistics Sweden.

2.4. Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were performed separately for each country according to a common study protocol. Descriptive statistics including the proportion of pregnant women vaccinated with at least one dose while pregnant and type of vaccine for the last given dose were calculated. To show vaccination status among delivering women over time, the proportion of vaccinated women with at least one, two and three doses at the time of delivery (independent on the doses being administered prior pregnancy or while pregnant) between May 2021 and May 2022 was calculated based on a 7-day moving average.

To assess hesitancy to get vaccinated while being pregnant, a Poisson regression with log-link and robust standard errors was used to estimate risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association between background characteristics and not being vaccinated with at least one dose of vaccine while pregnant. Two study periods were used: 1) the full study period starting in May 1, 2021; and 2) a restricted study period starting in August 15, 2021 as from this point forward everyone above 18 years of age were recommended vaccination and availability of vaccine was excellent. End of follow-up was May 24, 2022 for both study periods. First, crude RRs were estimated for the full study period. Secondly, crude and age-adjusted RRs were estimated for the restricted study period. For estimates on characteristics of education and income, only those above 30 years were included in the age-adjusted analyses, as prior to this age, few have attained their highest education and income. A sensitivity analysis excluding those that had only been vaccinated prior pregnancy was performed.

Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (Sweden) and Stata version 16 (Norway).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (approval numbers: 2020–01499, 2020–02468, 2021–00274) and Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics of South/East Norway (#141135). Each committee provided a waiver of consent for participants.

3. Results

In Sweden, 48 317 of 108 715 (44%) women registered with a birth during the full study period and 43 591 of 76 638 (57%) during the restricted study period, were vaccinated with at least one dose while pregnant. Of 55 845 women registered with a birth in Norway, 21 195 (38%) were vaccinated with at least one dose while pregnant during the full study period, and 20 931 of 38 447 (54%) during the restricted study period.

Table 1 shows the type of administered vaccine of last given dose among those vaccinated with at least one dose while pregnant. The majority was vaccinated with BNT162b2 (77%), 23% with mRNA-1273 and < 1% with AZD1222.

Table 1.

Type of administered vaccine of last given dose among those vaccinated with at least one dose while pregnant, May 1, 2021 to May 24, 2022 in Sweden and Norway.

|

Sweden (N = 48 317) |

Norway (N = 21 195) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dose 1a n = 5787 (11.9) |

Dose 2b n = 32 470 (67.2) |

Dose 3c n = 10 060 (20.8) |

Dose 1a n = 3915 (18.5) |

Dose 2b n = 15 229 (71.9) |

Dose 3c n = 2051 (9.7) |

|

| Type of vaccine – n (%) | ||||||

| BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) | 4568 (78.9) | 26 657 (82.1) | 7832 (77.9) | 2599 (66.4) | 10 102 (66.3) | 1716 (83.7) |

| mRNA-1273 (Moderna) | 1130 (19.5) | 5718 (17.6) | 2227 (22.1) | 1316 (33.6) | 5127 (33.7) | 335 (16.3) |

| AZD1222 (AstraZeneca) | 89 (1.5) | 95 (0.3) | 1 (0.01) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Women in category “dose 1”, corresponds to those that were given their first dose of vaccine while pregnant, and not taken the second or third dose while pregnant.

A women only counts once, meaning that if she received dose 2 while pregnant she is in category “dose 2” regardless of whether dose 1 was given prior pregnancy or while being pregnant.

If she received dose 3 while pregnant she is in category “dose 3”, regardless of whether dose 1 and/or 2 was given prior pregnancy or while being pregnant. Women only vaccinated before pregnancy are not included in the table (<2% of the full study period population).

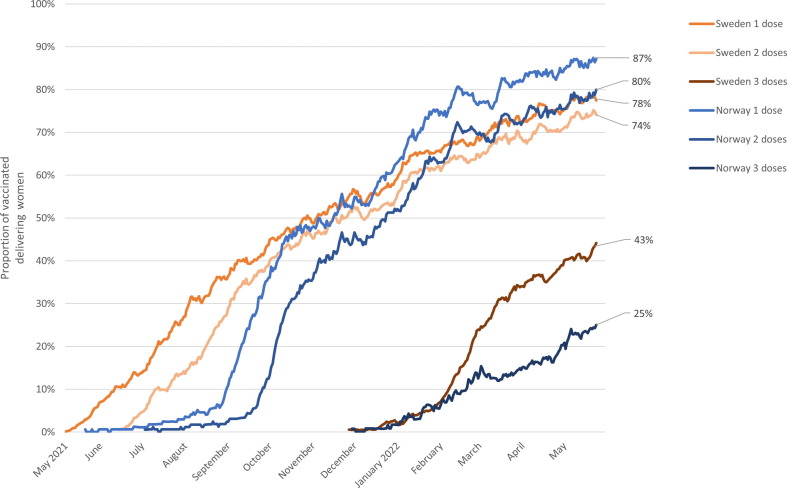

As shown in Fig. 2 , the proportion of women vaccinated with at least one, two and three doses of vaccine at the time of delivery (including doses given prior pregnancy) based on the 7-day moving average increased steadily since the vaccinations started in May 2021. As of May 2022, 78% in Sweden and 87% in Norway have been vaccinated with at least one dose.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of vaccinated delivering women between May 2021 through May 2022 in Sweden and Norway, based on a 7-day moving average. Footnote: One, two and three doses corresponds to those vaccinated with at least one, two or three doses of vaccine at delivery, and thus includes women that may have been vaccinated prior pregnancy.

Background characteristics and vaccination while pregnant are presented in Table 2 (Sweden) and Table 3 (Norway). Several background characteristics were associated with hesitancy to get vaccinated, with similar RRs for the full and restricted study period and after age adjustment in both countries. The RRs for the restricted study period showed a hesitancy to get vaccinated for women younger than 30 years of age (RR range 1.15–1.76) and above 40 years of age (only in Norway: RR 1.12), and for women being multiparous (age-adjusted RR aRR range 1.11–1.18), with less than 12 years of education ([aRR] range 1.36–1.74), being born outside Scandinavia (aRR range 1.23–2.06), those smoking during pregnancy (aRR range 1.25–1.49), living alone (aRR range 1.26–1.33) and those with gestational diabetes (aRR range 1.16–1.18). The vaccine uptake was higher (indicated as RR below 1 of being unvaccinated) in pregnant women with higher income levels, pre-pregnancy comorbidities and preeclampsia. In Sweden, women with lower (aRR 1.12) and higher BMI (aRR 1.07) compared to normal weight women were more hesitant to get vaccinated while pregnant, while this was only seen for those with lower BMI (aRR 1.14) in Norway. No difference in effect estimates was seen after exclusion of those only vaccinated prior pregnancy (<2% of the full study period population).

Table 2.

Association between background characteristics and not being vaccinated while pregnant, May 1, 2021 and May 24, 2022 (n = 108 715) and August 15, 2021 and May 24, 2022 (n = 76 638) in Sweden.

| Characteristics |

Full study period: May 1, 2021 to May 24, 2022 |

Restricted study period: August 15, 2021 to May 24, 2022 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Overall(vaccinated and not vaccinated) N = 108 715 |

At least one dose while pregnant n = 48 317 |

Not vaccinated while pregnant n = 60 398 |

Risk Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

At least one dose while pregnant n = 43 591 |

Not vaccinated while pregnant n = 33 047 |

Risk Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

Age-adjusted Risk Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

| Maternal age (years) – n (%) | ||||||||

| <20 | 1092 (1.0) | 270 (0.6) | 822 (1.4) | 1.44 (1.39, 1.49) | 261 (0.6) | 533 (1.6) | 1.76 (1.67, 1.85) | |

| 20–24 | 10 262 (9.4) | 3043 (6.3) | 7219 (12.0) | 1.34 (1.32, 1.36) | 2847 (6.5) | 4387 (13.3) | 1.59 (1.55, 1.62) | |

| 25–29 | 35 038 (32.2) | 14 337 (29.7) | 20 701 (34.3) | 1.13 (1.11, 1.14) | 13 244 (30.4) | 11 383 (34.4) | 1.21 (1.19, 1.23) | |

| 30–34 | 40 664 (37.4) | 19 367 (40.1) | 21 297 (35.3) | Reference | 17 651 (40.5) | 10 922 (33.0) | Reference | |

| 35–39 | 17 862 (16.4) | 9376 (19.4) | 8486 (14.1) | 0.91 (0.89, 0.92) | 7931 (18.2) | 4717 (14.3) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.00) | |

| >40 | 3797 (3.5) | 1924 (4.0) | 1873 (3.1) | 0.94 (0.91, 0.97) | 1657 (3.8) | 1105 (3.3) | 1.05 (1.00, 1.10) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) – n (%) | ||||||||

| <18.5 | 2269 (2.1) | 876 (1.8) | 1393 (2.3) | 1.11 (1.07, 1.14) | 820 (1.9) | 787 (2.4) | 1.17 (1.11, 1.23) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.18) |

| 18.5-<25 | 54 627 (50.2) | 24 326 (50.3) | 30 301 (50.2) | Reference | 22 158 (50.8) | 15 947 (48.3) | Reference | Reference |

| 25-<30 | 29 686 (27.3) | 12 788 (26.5) | 16 898 (28.0) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.04) | 11 668 (26.8) | 9422 (28.5) | 1.07 (1.05, 1.09) | 1.07 (1.05, 1.09) |

| >30 | 18 087 (16.6) | 8589 (17.8) | 9498 (15.7) | 0.95 (0.93, 0.96) | 7375 (16.9) | 5592 (16.9) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.05) |

| Missing | 4046 (3.7) | 1738 (3.6) | 2308 (3.8) | 1570 (3.6) | 1299 (3.9) | |||

| Parity – n (%) | ||||||||

| Nulliparous | 46 303 (42.6) | 21 068 (43.6) | 25 235 (41.8) | Reference | 19 229 (44.1) | 13 573 (41.1) | Reference | Reference |

| Multiparous | 62 412 (57.4) | 27 249 (56.4) | 35 163 (58.2) | 1.03 (1.02, 1.05) | 24 362 (55.9) | 19 474 (58.9) | 1.07 (1.06, 1.09) | 1.18 (1.16, 1.20) |

| Educational level (years) – n (%)ab | ||||||||

| <9 | 4673 (9.7) | 453 (4.0) | 4220 (11.4) | 1.29 (1.28, 1.31) | 271 (4.2) | 1275 (13.3) | 1.69 (1.64, 1.75) | 1.74 (1.66, 1.83) |

| 10–12 | 18 781 (39.0) | 3494 (31.2) | 15 287 (41.4) | 1.16 (1.15, 1.18) | 2096 (32.4) | 4190 (43.8) | 1.37 (1.33, 1.41) | 1.36 (1.31, 1.42) |

| >12 | 23 753 (49.4) | 7145 (63.8) | 16 608 (45.0) | Reference | 4034 (62.4) | 3834 (40.0) | Reference | Reference |

| Missing | 915 (1.9) | 102 (0.9) | 813 (2.2) | 67 (1.0) | 278 (2.9) | |||

| Income – n (%)abc | ||||||||

| 1st tertile | 15 651 (32.5) | 2559 (22.9) | 13 092 (35.5) | Reference | 1541 (23.8) | 3733 (39.0) | Reference | Reference |

| 2nd tertile | 15 602 (32.4) | 3684 (32.9) | 11 918 (32.3) | 0.91 (0.90, 0.92) | 2148 (33.2) | 2965 (31.0) | 0.82 (0.80, 0.84) | 0.79 (0.76, 0.83) |

| 3rd tertile | 15 460 (32.1) | 4802 (42.9) | 10 658 (28.9) | 0.82 (0.81, 0.83) | 2686 (41.5) | 2415 (25.2) | 0.67 (0.65, 0.69) | 0.64 (0.62, 0.67) |

| Missing | 1409 (2.9) | 149 (1.3) | 1260 (3.4) | 93 (1.4) | 464 (4.8) | |||

| Birth country – n (%) | ||||||||

| Scandinavia | 73 730 (67.8) | 37 236 (77.1) | 36 494 (60.4) | Reference | 33 237 (76.2) | 17 393 (52.6) | Reference | Reference |

| Other European countries | 7491 (6.9) | 1969 (4.1) | 5522 (9.1) | 1.49 (1.47, 1.51) | 1705 (3.9) | 3248 (9.8) | 1.91 (1.86, 1.95) | 1.96 (1.91, 2.00) |

| Middle East/ Africa | 16 193 (14.9) | 3547 (7.3) | 12 646 (20.9) | 1.58 (1.56, 1.60) | 3325 (7.6) | 8025 (24.3) | 2.06 (2.02, 2.09) | 2.03 (2.00, 2.07) |

| Other | 4972 (4.6) | 2357 (4.9) | 2615 (4.3) | 1.06 (1.03, 1.09) | 2123 (4.9) | 1430 (4.3) | 1.17 (1.12, 1.22) | 1.23 (1.18, 1.28) |

| Missing | 6329 (5.8) | 3208 (6.6) | 3121 (5.2) | 3201 (7.3) | 2951 (8.9) | |||

| Smoking status – n (%) | ||||||||

| Non-smoker | 101 479 (93.3) | 45 689 (94.6) | 55 790 (92.4) | Reference | 41 179 (94.5) | 30 274 (91.6) | Reference | Reference |

| Smoker | 3381 (3.1) | 887 (1.8) | 2494 (4.1) | 1.34 (1.31, 1.37) | 807 (1.9) | 1570 (4.8) | 1.56 (1.51, 1.61) | 1.49 (1.44, 1.53) |

| Missing | 3855 (3.5) | 1741 (3.6) | 2114 (3.5) | 1605 (3.7) | 1203 (3.6) | |||

| Living with partner – n (%) | ||||||||

| Yes | 98 269 (90.4) | 44 442 (92.0) | 53 827 (89.1) | Reference | 40 103 (92.0) | 29 017 (87.8) | Reference | Reference |

| No | 8010 (7.4) | 2790 (5.8) | 5220 (8.6) | 1.19 (1.17, 1.21) | 2511 (5.8) | 3259 (9.9) | 1.35 (1.31, 1.38) | 1.33 (1.30, 1.36) |

| Missing | 2436 (2.2) | 1085 (2.2) | 1351 (2.2) | 977 (2.2) | 771 (2.3) | |||

| Pre-pregnancy comorbidity – n (%) | ||||||||

| Anyd | 41 312 (38.0) | 19 917 (41.2) | 21 395 (35.4) | 0.89 (0.88, 0.91) | 17 816 (40.9) | 11 293 (34.2) | 0.85 (0.83, 0.86) | 0.86 (0.84, 0.87) |

| Pregnancy related factors – n (%) | ||||||||

| Gestational diabetes | 6318 (5.8) | 2655 (5.5) | 3663 (6.1) | 1.05 (1.02, 1.07) | 2299 (5.3) | 2113 (6.4) | 1.12 (1.08, 1.15) | 1.16 (1.12, 1.20) |

| Preeclampsia | 3785 (3.5) | 1855 (3.8) | 1930 (3.2) | 0.92 (0.89, 0.94) | 1662 (3.8) | 1005 (3.0) | 0.87 (0.83, 0.91) | 0.87 (0.83, 0.91) |

| Multiple pregnancy | 1418 (1.3) | 633 (1.3) | 785 (1.3) | 1.00 (0.95, 1.04) | 567 (1.3) | 439 (1.3) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.09) | 1.04 (0.97, 1.11) |

Information available from Statistics Sweden up to October 11, 2021 which implies information on 44% (48 122/108 715) of the cohort from May 1, 2021 and 21% (16 045/76 638) of the cohort from August 15, 2021.

For the age-adjusted analysis of education and income, only those above 30 years of age and with data from Statistics Sweden are included, which implies 57% (49 983/76 638) of the cohort from August 15, 2021.

Income in Sweden was based on individual income and tertiles were based on pregnant population with delivery dates.

Includes diabetes, chronic hypertension, cardiovascular disease, renal disease, lung disease/asthma and thrombosis.

Table 3.

Association between background characteristics and not being vaccinated while being pregnant, May 1, 2021 and May 24, 2022 (n = 55 845) and August 15, 2021 and May 24, 2022 (n = 38 447) in Norway.

| Characteristics |

Full study period: May 1, 2021 to May 24, 2022 |

Restricted study period: August 15, 2021 to May 24, 2022 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Overall (vaccinated and not vaccinated) N = 55 845 |

At least one dose while pregnant n = 21 195 |

Not vaccinated while pregnant n = 34 650 |

Risk Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

At least one dose while pregnant n = 20 931 |

Not vaccinated while pregnant n = 17 516 |

Risk Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

Age-adjusted Risk Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

| Maternal age (years) – n (%) | ||||||||

| <20 | 480 (0.9) | 121 (0.6) | 359 (1.0) | 1.26 (1.19, 1.33) | 120 (0.6) | 206 (1.2) | 1.52 (1.40, 1.66) | |

| 20–24 | 5265 (9.4) | 1615 (7.6) | 3650 (10.5) | 1.17 (1.14, 1.19) | 1598 (7.6) | 2097 (12.0) | 1.37 (1.32, 1.42) | |

| 25–29 | 18 715 (33.5) | 6769 (31.9) | 11 946 (34.5) | 1.07 (1.06, 1.09) | 6706 (32.0) | 6157 (35.2) | 1.15 (1.12, 1.19) | |

| 30–34 | 21 224 (38.0) | 8600 (40.6) | 12 624 (36.4) | Reference | 8485 (40.5) | 6007 (34.3) | Reference | |

| 35–39 | 8680 (15.5) | 3529 (16.7) | 5151 (14.9) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 3475 (16.6) | 2574 (14.7) | 1.03 (0.99, 1.06) | |

| >40 | 1481 (2.7) | 561 (2.7) | 920 (2.7) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.09) | 547 (2.6) | 475 (2.7) | 1.12 (1.5, 1.20) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) – n (%) | ||||||||

| <18.5 | 1690 (3.0) | 567 (2.7) | 1123 (3.2) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) | 555 (2.7) | 616 (3.5) | 1.17 (1.11, 1.24) | 1.14 (1.08, 1.21) |

| 18.5-<25 | 30 293 (54.2) | 11 617 (54.8) | 18 676 (53.9) | Reference | 11 493 (54.9) | 9367 (53.5) | Reference | Reference |

| 25-<30 | 7857 (14.0) | 4811 (22.7) | 7857 (22.7) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | 4754 (22.7) | 3972 (22.7) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) |

| >30 | 4725 (8.5) | 3044 (14.4) | 4725 (13.6) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 2995 (14.3) | 2472 (14.1) | 1.01 (0.9, 1.04) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) |

| Missing | 3425 (6.1) | 1156 (5.5) | 2269 (6.5) | 114 (5.4) | 1089 (6.2) | |||

| Parity – n (%) | ||||||||

| Nulliparous | 23 712 (42.5) | 9313 (43.9) | 14 399 (41.6) | Reference | 9189 (43.9) | 7254 (41.4) | Reference | Reference |

| Multiparous | 32 133 (57.5) | 11 882 (56.1) | 20 251 (58.4) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.05) | 11 742 (56.1) | 10 262 (58.6) | 1.06 (1.03, 1.08) | 1.11 (1.09, 1.14) |

| Educational level (years) – n (%)a | ||||||||

| <9 | 7507 (13.4) | 2153 (10.2) | 5354 (15.5) | 1.28 (1.25, 1.30) | 2132 (10.2) | 3161 (18.0) | 1.68 (1.63, 1.73) | 1.74 (1.67, 1.82) |

| 10–12 | 10 656 (19.1) | 3734 (17.6) | 6922 (20.0) | 1.16 (1.14, 1.18) | 3700 (17.7) | 7617 (43.5) | 1.40 (1.36, 1.44) | 1.39 (1.34, 1.46) |

| >12 | 31 662 (56.7) | 13 968 (65.9) | 17 694 (51.0) | Reference | 13 777 (65.8) | 3696 (21.1) | Reference | Reference |

| Missing | 6020 (10.8) | 1340 (6.3) | 4680 (13.5) | 1322 (6.3) | 3042 (17.4) | |||

| Income – n (%)a | ||||||||

| 1st tertile | 25 746 (46.1) | 9315 (43.9) | 16 431 (46.0) | Reference | 9201 (44.0) | 8773 (50.1) | Reference | Reference |

| 2nd tertile | 14 845 (26.6) | 5938 (28.0) | 8907 (25.7) | 0.94 (0.92, 0.96) | 5876 (28.1) | 4100 (23.4) | 0.84 (0.92, 0.87) | 0.80 (0.77, 0.83) |

| 3rd tertile | 11 631 (20.8) | 5061 (23.9) | 6570 (18.9) | 0.89 (0.87, 0.90) | 4984 (23.8) | 2788 (15.9) | 0.73 (0.71, 0.76) | 0.66 (0.63, 0.70) |

| Missing | 3623 (6.5) | 881 (4.2) | 2742 (7.9) | 870 (4.2) | 1855 (10.6) | |||

| Birth country – n (%) | ||||||||

| Scandinavia | 41 280 (74.1) | 17 767 (83.9) | 23 513 (68.1) | Reference | 17 565 (83.9) | 10 679 (61.0) | Reference | Reference |

| Other European countries |

6176 (11.1) |

1336 (6.3) | 4840 (14.0) | 1.37 (1.35, 1.40) | 1310 (6.3) | 2979 (17.0) | 1.84 (1.79, 1.88) | 1.89 (1.84, 1.93) |

| Middle East/ Africa | 4017 (7.2) | 633 (3.0) | 3384 (9.8) | 1.48 (1.46, 1.50) | 626 (3.0) | 2241 (12.8) | 2.07 (2.02, 2.12) | 2.06 (2.01, 2.11) |

| Other | 4218 (7.6) | 1437 (6.8) | 2781 (8.1) | 1.16 (1.13, 1.18) | 1409 (6.7) | 1517 (8.7) | 1.37 (1.21, 1.42) | 1.43 (1.37, 1.48) |

| Missing | 7 (0.01) | 2 (0.01) | 5 (0.01) | 21 (0.1) | 100 (5.7) | |||

| Smoking status – n (%) | ||||||||

| Non-smoker | 47 208 (84.5) | 18 202 (85.9) | 29 006 (83.7) | Reference | 17 984 (85.9) | 14 450 (82.5) | Reference | Reference |

| Smoker | 2589 (4.6) | 789 (3.7) | 1800 (5.2) | 1.13 (1.10, 1.16) | 770 (3.7) | 969 (5.5) | 1.25 (1.20, 1.31) | 1.25 (1.19, 1.30) |

| Missing | 6048 (10.8) | 2204 (10.4) | 3844 (11.1) | 2177 (10.4) | 2097 (12.0) | |||

| Living with partner – n (%) | ||||||||

| Yes | 52 713 (94.4) | 20 226 (95.4) | 32 487 (93.8) | Reference | 19 983 (95.5) | 16 324 (93.2) | Reference | Reference |

| No | 2232 (4.0) | 680 (3.2) | 1152 (3.3) | 1.13 (1.10, 1.16) | 666 (3.2) | 877 (5.0) | 1.26 (1.21, 1.32) | 1.26 (1.21, 1.32) |

| Missing | 900 (1.6) | 289 (1.4) | 611 (1.8) | 282 (1.3) | 315 (1.8) | |||

| Pre-pregnancy comorbidity – n (%) | ||||||||

| Anyb | 5075 (9.1) | 2146 (10.1) | 2929 (8.5) | 0.92 (0.90, 0.95) | 2088 (10.0) | 1416 (8.1) | 0.88 (0.84, 0.91) | 0.88 (0.84, 0.92) |

| Pregnancy related factors – n (%) | ||||||||

| Gestational diabetes | 3554 (6.4) | 1217 (5.7) | 2337 (6.7) | 1.06 (1.03, 1.09) | 1195 (5.7) | 1275 (7.3) | 1.14 (1.10, 1.19) | 1.18 (1.13, 1.22) |

| Preeclampsia | 1625 (2.9) | 680 (3.2) | 945 (2.7) | 0.94 (0.90, 0.98) | 669 (3.2) | 480 (2.7) | 0.91 (0.85, 0.98) | 0.91 (0.85, 0.97) |

| Multiple pregnancy | 776 (1.4) | 319 (1.5) | 457 (1.3) | 0.95 (0.89, 1.01) | 311 (1.5) | 213 (1.2) | 0.89 (0.80,0.99) | 0.91 (0.82, 1.00) |

For the age-adjusted analysis of education and income, only those above 30 years of age are included. Income in Norway was based on household income and tertiles were calculated based on the pregnant population.

Includes diabetes, chronic hypertension, cardiovascular disease, renal disease, lung disease/asthma and thrombosis.

4. Discussion

In this population-based cohort study of birthing women in Sweden and Norway from May 2021 through May 2022, lower vaccination uptake in pregnant women was associated with low levels of education and income, being born outside Scandinavia, smoking during pregnancy and living alone, together with young age. The overall vaccination coverage in Sweden and Norway is high, with approximately 77% of women in fertile age in Sweden [14], and 85% in Norway having received two doses of vaccine [15]. During the beginning of the study period, when the availability of vaccines was limited and when only women at high risk were recommended to get vaccinated, the overall vaccine uptake in delivering women was lower. However, there was a substantial increase in vaccination of delivering women during the autumn of 2021, with the uptake up to May 2022 corresponding to the overall vaccine uptake among women of fertile ages.

Nevertheless, a group of pregnant women are hesitant to get vaccinated while pregnant and remains unvaccinated. With pregnant women being at higher risk of severe COVID-19, and as infants born to women with severe COVID-19 are at increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes [16], [17], vaccination will prevent subsequent morbidity and mortality of COVID-19 [2], as well as protect the infant from COVID-19 infection [18]. By presenting population-based real-world data of vaccination coverage in birthing women and vaccine uptake during pregnancy in two Scandinavian countries, our results can assist health care organizers to target specific vulnerable groups to increase vaccination uptake.

Hesitancy towards vaccines in the general population is a multi-factored phenomenon affected by socio-demographic, political, cognitive, psychologic and cultural factors and may differ across countries [19], [20]. In the context of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and pregnancy, the speed during which the vaccines were developed, the exclusion of pregnant women from the first clinical trials [2], in addition to initial recommendations against routine vaccination in pregnancy that were later changed as safety data accumulated [8], may have contributed to vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women.

Similar to previous studies which investigated vaccine uptake at single-center birth hospitals and showed that those with high levels of deprivation were less likely to be vaccinated compared to those of higher socioeconomic position [8], [11], we found that low education level was associated with not being vaccinated. Similar results have been observed in the general population [21].

It has been shown that ethnic minority groups are more likely to suffer from severe disease, hospitalization and death due to COVID-19 [22]. We did not have information on ethnicity. However, our results show that being born outside Scandinavia was associated with lower rates of vaccination while pregnant. This is consistent with findings from the general population in both Sweden and Norway, and among Swedish health care workers [23]. Targeted information to vulnerable groups is necessary while challenging [19], [21].

Even after restricting the cohort to the time period when all pregnant women independent of risk factors were recommended and able to get vaccinated, and after adjustment for age, we found that women with pre-pregnancy comorbidities were more likely to get vaccinated during pregnancy. It is possible that these women were less hesitant to get vaccinated as they had additional risk factors for severe COVID-19 [17].

This study took advantage of the population-based prospectively collected data in vaccination registers to identify vulnerable groups not being vaccinated, however the study was limited by not being able to target specific reasons for vaccine hesitancy or how the introduction of compulsory vaccination passes, for instance, may have affected vaccination rates. And while our current data show similar uptake among women giving birth and non-pregnant individuals in both Sweden and Norway, this is not the case for other countries [9]. Thus, it is of importance for future studies to look at vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women in particular.

5. Conclusions

While vaccine uptake of delivering women in Sweden and Norway were similar to the general population one year after the initial recommendations to pregnant women to get vaccinated, we found that hesitancy to get vaccinated while pregnant was associated with lower socio-economic levels. Targeted intervention to specific vulnerable groups may increase vaccination uptake in groups with high risk of severe COVID-19.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper: [R.L. and B.A. are employed at the Swedish Medical Products Agency, SE-751 03 Uppsala, Sweden. The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily represent the views of this Government agency.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the Scandinavian studies of COvid-19 in PrEgnancy (SCOPE) scientific team for fruitful discussions, and the Swedish Public Health Agency for collaboration on vaccination data, and the Swedish Pregnancy Register.

Funding

This work was funded by Nordforsk through the funding to SCOPE - Scandinavian studies of COvid-19 in PrEgnancy (No. 105545) and by the Norwegian Research Council through its Centres of Excellence scheme (No. 262700) and the project: Safety of Covid-19 vaccination in pregnancy (No. 324312), and by the Swedish Medical Products Agency (No. 2021-037931).

Research data for this article

Data are available by applying to the registry owners: https://helsedata.no/soknadsveiledning/ and https://www.medscinet.com/gr/forskare.aspx

References

- 1.Magnus M.C., Oakley L., Gjessing H.K., Stephansson O., Engjom H.M., Macsali F., et al. Pregnancy and risk of COVID-19: a Norwegian registry-linkage study. BJOG. 2022;129(1):101–109. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engjom H., van den Akker T., Aabakke A., Ayras O., Bloemenkamp K., Donati S., et al. Severe COVID-19 in pregnancy is almost exclusively limited to unvaccinated women - time for policies to change. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;13:100313. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dagan N., Barda N., Kepten E., Miron O., Perchik S., Katz M.A., et al. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide mass vaccination setting. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(15):1412–1423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldshtein I., Nevo D., Steinberg D.M., Rotem R.S., Gorfine M., Chodick G., et al. Association between BNT162b2 vaccination and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women. JAMA. 2021;326(8):728. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prasad S., Kalafat E., Blakeway H., Townsend R., O’Brien P., Morris E., et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and perinatal outcomes of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30052-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magnus M.C., Örtqvist A.K., Dahlqwist E., Ljung R., Skår F., Oakley L., et al. Association of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination during pregnancy with pregnancy outcomes. JAMA. 2022;327(15):1469. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blakeway H., Prasad S., Kalafat E., Heath P.T., Ladhani S.N., Le Doare K., et al. COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy: coverage and safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(2):236.e1–236.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skjefte M., Ngirbabul M., Akeju O., Escudero D., Hernandez-Diaz S., Wyszynski D.F., et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women and mothers of young children: results of a survey in 16 countries. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36(2):197–211. doi: 10.1007/s10654-021-00728-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stock S.J., Carruthers J., Calvert C., Denny C., Donaghy J., Goulding A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women in Scotland. Nat Med. 2022;28(3):504–512. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01666-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wainstock T., Yoles I., Sergienko R., Sheiner E. Prenatal maternal COVID-19 vaccination and pregnancy outcomes. Vaccine. 2021;39(41):6037–6040. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Public Health Agency of Sweden. Guidance on vaccination against COVID-19. Web page in Swedish. [cited 2022 June 20]. Available from: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/smittskydd-beredskap/utbrott/aktuella-utbrott/covid-19/vaccination-mot-covid-19/for-personal-inom-vard-och-omsorg/for-personal-inom-halso--och-sjukvard/Vagledning-och-fordjupad-information-om-vaccination-mot-covid-19/.

- 13.Norwegian government. AstraZeneca-vaksinen tas ut av koronavaksinasjons-programmet. Web page in Norwegian. [cited 2022 June 20]. Available from: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/astrazeneca-vaksinen-tas-ut-av-koronavaksinasjonsprogrammet/id2849494/.

- 14.Public Health Agency of Sweden. Statistics of vaccinated in Sweden. Web page in Swedish. [cited 2022 June 20]. Available from: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/folkhalsorapportering-statistik/statistikdatabaser-och-visualisering/vaccinationsstatistik/statistik-for-vaccination-mot-covid-19/.

- 15.Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Statistics Bank [cited 2022 June 20]. Available from: https://www.fhi.no/en/hn/statistics/statistics-from-niph/statistikkbanker/.

- 16.Villar J., Ariff S., Gunier R.B., Thiruvengadam R., Rauch S., Kholin A., et al. Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality among pregnant women with and without COVID-19 infection: the INTERCOVID multinational cohort study. JAMA pediatrics. 2021;175(8):817. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allotey J., Stallings E., Bonet M., Yap M., Chatterjee S., Kew T., et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlsen E.O., Magnus M.C., Oakley L., Fell D.B., Greve-Isdahl M., Kinge J.M., et al. Association of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy with incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in infants. JAMA Intern Med. 2022 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9(2):160. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sallam M., Al-Sanafi M., Sallam M. A global map of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rates per country: an updated concise narrative review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2022;15:21–45. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S347669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cascini F., Pantovic A., Al-Ajlouni Y., Failla G., Ricciardi W. Attitudes, acceptance and hesitancy among the general population worldwide to receive the COVID-19 vaccines and their contributing factors: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;40:101113. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raharja A., Tamara A., Kok L.T. Association between ethnicity and severe COVID-19 disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(6):1563–1572. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00921-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ljung R., Feychting M., Burström B.o., Möller J. Differences by region of birth in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine coverage and positive SARS-CoV-2 test among 400 000 healthcare workers and the general population in Sweden. Vaccine. 2022;40(21):2904–2909. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]