This retrospective cohort study investigates the association between sociodemographic characteristics and medical school attrition rates in the US.

Key Points

Question

How do the medical student attrition rates compare across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic identities?

Findings

In this cohort study of 33 389 allopathic doctor of medicine medical school matriculants, students who identified as underrepresented in medicine race and ethnicity, had low income, and were from underresourced backgrounds were more likely to leave medical school. The rate of attrition increased with each additional coexisting marginalized identity.

Meaning

The prevalence of inequality in attrition rates across individual and structural measures of marginalization warrants systemic and structural reform.

Abstract

Importance

Diversity in the medical workforce is critical to improve health care access and achieve equity for resource-limited communities. Despite increased efforts to recruit diverse medical trainees, there remains a large chasm between the racial and ethnic and socioeconomic composition of the patient population and that of the physician workforce.

Objective

To analyze student attrition from medical school by sociodemographic identities.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study included allopathic doctor of medicine (MD)–only US medical school matriculants in academic years 2014-2015 and 2015-2016. The analysis was performed from July to September 2021.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcome was attrition, defined as withdrawal or dismissal from medical school for any reason. Attrition rate was explored across 3 self-reported marginalized identities: underrepresented in medicine (URiM) race and ethnicity, low income, and underresourced neighborhood status. Logistic regression was assessed for each marginalized identity and intersections across the 3 identities.

Results

Among 33 389 allopathic MD–only medical school matriculants (51.8% male), 938 (2.8%) experienced attrition from medical school within 5 years. Compared with non-Hispanic White students (423 of 18 213 [2.3%]), those without low income (593 of 25 205 [2.3%]), and those who did not grow up in an underresourced neighborhood (661 of 27 487 [2.4%]), students who were URiM (Hispanic [110 of 2096 (5.2%); adjusted odds ratio (aOR), 1.41; 95% CI, 1.13-1.77], non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander [13 of 118 (11.0%); aOR, 3.20; 95% CI, 1.76-5.80], and non-Hispanic Black/African American [120 of 2104 (5.7%); aOR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.13-1.77]), those who had low income (345 of 8184 [4.2%]; aOR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15-1.54), and those from an underresourced neighborhood (277 of 5902 [4.6%]; aOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.58) were more likely to experience attrition from medical school. The rate of attrition from medical school was greatest among students with all 3 marginalized identities (ie, URiM, low income, and from an underresourced neighborhood), with an attrition rate 3.7 times higher than that among students who were not URiM, did not have low income, and were not from an underresourced neighborhood (7.3% [79 of 1086] vs 1.9% [397 of 20 353]; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

This retrospective cohort study demonstrated a significant association of medical student attrition with individual (race and ethnicity and family income) and structural (growing up in an underresourced neighborhood) measures of marginalization. The findings highlight a need to retain students from marginalized groups in medical school.

Introduction

Racial and ethnic and socioeconomic diversity in the medical workforce affords complementary skill sets and perspectives that stimulate innovation and excellence in health care equity and access.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 Although diversity of matriculants to medical schools increased in the past decade after the introduction of diversity accreditation standards,9 little is known about retention of students at these institutions.

Reports from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) describe a consistent attrition rate in the past 20 years for all medical students in aggregate.10 Previous studies showed higher attrition rates among Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, and Native American/Alaska Native students.11,12 However, these studies examined outcomes of students attending medical school more than 15 years ago. In addition, to our knowledge, none of these previous studies addressed sources of marginalization; the systemic alienation of specific groups based on categories other than race and ethnicity, such as family income; or the association of the intersection of students’ sociodemographic identities with retention in medical school. Furthermore, there is scant literature describing how a student’s exposure to structural inequities, such as growing up in an underresourced neighborhood,13 influences academic success.

To address these critical knowledge gaps, we investigated the association of race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and growing up in an underresourced neighborhood and their intersectionality with medical school attrition in a contemporary, national cohort of US medical students. Greater insight into inequities in retention among medical students from these sociodemographic groups could inform future efforts to bolster physician workforce diversity.

Methods

Data and Participants

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all allopathic doctor of medicine (MD)–only US medical school matriculants in academic years 2014-2015 and 2015-2016 using deidentified student-level data from the AAMC data warehouse, the American Medical College Application Service (AMCAS), and the Student Records System. Our analyses were conducted according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. This study was deemed exempt by the Yale University institutional review board because data were deidentified, and informed consent was waived because student consent was obtained by the AAMC.

Student Sociodemographic Characteristics

Race and ethnicity were self-reported by students and were included in 7 categories: Hispanic, Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Black/African American, non-Hispanic White, and unknown or other (data on Hispanic and other racial subgroups were not available). Students who reported race and ethnicity in 2 or more of these groups were categorized as multiracial. For this study, underrepresented in medicine (URiM) referred to students who identified as Hispanic only, non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander only, or non-Hispanic Black/African American only. Race and ethnicity data were only provided by the AAMC for US citizens and permanent residents.

Family income was determined using 2 self-reported measures to capture past and current family income status: receipt of state or federal financial assistance self-reported on AMCAS and parental income reported on the Matriculating Student Questionnaire, a survey administered in the first year of medical school. A student was considered to have low income if they indicated that their family was a recipient of state or federal financial assistance programs (eg, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) or if their self-reported parental income was within the lowest 2 quintiles nationally14 (<$41 187 for the 2014-2015 cohort and <$43 512 for 2015-2016 cohort).

Underresourced neighborhood status was defined as growing up in a medically underserved area. Students were asked whether they grew up in a medically underserved area on the AMCAS. Neighborhoods that are designated as medically underserved have an inadequate number of health care practitioners to meet community needs.15 In addition, medically underserved areas often have limited access to quality housing, education, and economic opportunities.16,17

Academic Outcomes

The Student Records System is updated with students’ enrollment status by medical school registrar offices at least 3 times annually. We obtained attrition data (withdrawal or dismissal from school for any reason) for each student in September 2020, providing a minimum of 5 years’ follow-up for all students.

Covariates

Performance on standardized examinations and a student’s sex identity was previously shown to be associated with academic outcomes, such as attrition.10,18,19 Therefore, we adjusted for students’ Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) scores (categorized in quartiles) and sex in multivariable models.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed from July to September 2021. We first summarized the individual characteristics of the study cohort and compared attrition rates across sociodemographic characteristics using χ2 analysis. We then developed stepwise multivariate logistic regression models to understand the association between race and ethnicity, family income, and underresourced neighborhood status and attrition from medical school, adjusting for students’ sex and MCAT scores in quartiles. We further explored the intersections between race and ethnicity, family income, and underresourced neighborhood status by comparing relative attrition rates across multiple marginalized identities. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 16.1 (StataCorp LLC). Two-sided P < .05 indicated significance.

Results

The initial study cohort included 37 003 allopathic MD–only students, of whom 718 (1.9%) were still enrolled in medical school and were excluded. After excluding students who reenrolled, had MCAT scores not reported on the AMCAS, had missing parental income or underresourced neighborhood status data, and had unknown sex, a total of 33 389 students (90.2%; 51.8% male) were included in the analysis. Of these students, 6079 (18.2%) identified as non-Hispanic Asian, 18 213 (54.5%) as non-Hispanic White, and 4318 (12.9%) as URiM by race and ethnicity (2096 [6.3%] Hispanic, 118 [0.4%] non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 2104 [6.3%] non-Hispanic Black/African American) (Table 1). Furthermore, 8184 students (24.5%) were from low-income households (Table 1), and 5902 (17.7%) grew up in an underresourced neighborhood. Overall, 938 students (2.8%) experienced attrition from medical school.

Table 1. Characteristics of US Allopathic Doctor of Medicine Matriculants in Academic Years 2014-2015 and 2015-2016.

| Characteristic | Matriculants, No. (%) (N = 33 389) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 16 087 (48.2) |

| Male | 17 302 (51.8) |

| Race and ethnicitya | |

| Hispanic | 2096 (6.3) |

| Non-Hispanic | |

| AIAN/HNPI | 118 (0.4) |

| Asian | 6079 (18.2) |

| Black/African American | 2104 (6.3) |

| White | 18 213 (54.5) |

| Multiracial | 1961 (5.9) |

| Unknown or other | 2818 (8.4) |

| Low incomeb | |

| No | 25 205 (75.5) |

| Yes | 8184 (24.5) |

| Underresourced neighborhoodc | |

| No | 27 487 (82.3) |

| Yes | 5902 (17.7) |

| MCAT score, quartiled | |

| First | 7297 (21.9) |

| Second | 9794 (29.3) |

| Third | 6903 (20.7) |

| Fourth | 9395 (28.1) |

Abbreviations: AIAN/HNPI, American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; MCAT, Medical College Admission Test.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported by students. Students who reported race and ethnicity in 2 or more categories were identified as multiracial. Unknown or other was a category choice. Data on Hispanic racial subgroups were not available.

Recipient of state or federal financial assistance programs (eg, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) or parental income within the lowest 2 quintiles nationally (<$41 187, 2014-2015 cohort; <$43 512, 2015-2016 cohort).

Students who grew up in a medically underserved area.

Scores range from 15 to 45, with higher scores indicating greater test achievement. The first quartile included matriculants who scored less than 29; second, 29 to 31; third, 32 to 33, and fourth, greater than 33.

Attrition From Medical School

Race and Ethnicity

Student attrition varied among racial and ethnic groups. Students who were URiM had approximately twice the rate of attrition as non-Hispanic White students (5.6% [243] vs 2.3% [423]; P < .001). Although attrition was disproportionately high among all students who were URiM compared with non-Hispanic White students, the attrition rate among non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander students was particularly disparate at 11.0% (13 students).

In unadjusted models, there were significant differences in the likelihood of attrition between non-Hispanic White students and students who were URiM. Compared with non-Hispanic White students (2.3% [423 of 18 213), Hispanic (5.2% [110 of 2096]; odds ratio [OR], 2.32; 95% CI, 1.87-2.88), non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (11.0% [13 of 118]; OR, 5.20; 95% CI, 2.90-9.34), and non-Hispanic Black/African American (5.7% [120 of 2104]; OR, 2.54; 95% CI, 2.06-3.13) students were more likely to experience attrition from medical school (Table 2). After adjusting for sex and MCAT scores, the odds of attrition diminished, but differences were still significant; student groups who were URiM had disproportionately higher odds of attrition compared with non-Hispanic White students: Hispanic (adjusted OR [aOR], 1.41; 95% CI, 1.13-1.77), non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (aOR, 3.20; 95% CI, 1.76-5.80), and non-Hispanic Black/African American (aOR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.13-1.77) (Table 2).

Table 2. Attrition From Medical School Among US Allopathic Doctor of Medicine Matriculants in Academic Years 2014-2015 and 2015-2016.

| Characteristic | Matriculants, No. | Attrition, No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted rate of attrition, %b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Fully adjusteda | ||||

| All | 33 389 | 938 (2.8) | NA | NA | NA |

| Race and ethnicityc | |||||

| Hispanic | 2096 | 110 (5.2) | 2.32 (1.87-2.88) | 1.41 (1.13-1.77) | 3.5 |

| Non-Hispanic | |||||

| AIAN/HNPI | 118 | 13 (11.0) | 5.20 (2.90-9.34) | 3.20 (1.76-5.80) | 7.4 |

| Asian | 6079 | 151 (2.4) | 1.07 (0.88-1.29) | 1.22 (1.00-1.47) | 3.0 |

| Black/African American | 2104 | 120 (5.7) | 2.54 (2.06-3.13) | 1.41 (1.13-1.77) | 3.5 |

| White | 18 213 | 423 (2.3) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 2.5 |

| Multiracial | 1961 | 62 (3.1) | 1.37 (1.04-1.80) | 1.21 (0.92-1.59) | 3.0 |

| Unknown or other | 2818 | 59 (2.0) | 0.89 (0.68-1.18) | 0.92 (0.69-1.21) | 2.3 |

| Low incomed | |||||

| No | 25 205 | 593 (2.3) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 2.5 |

| Yes | 8184 | 345 (4.2) | 1.82 (1.59-2.09) | 1.33 (1.15-1.54) | 3.4 |

| Underresourced neighborhoode | |||||

| No | 27 487 | 661 (2.4) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 2.6 |

| Yes | 5902 | 277 (4.6) | 1.99 (1.73-2.30) | 1.35 (1.16-1.58) | 3.5 |

Abbreviations: AIAN/HNPI, American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

Adjusted for sex and Medical College Admission Test scores.

Calculated from the fully adjusted model.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported by students. Students who reported race and ethnicity in 2 or more categories were identified as multiracial. Unknown or other was a category choice. Data on Hispanic racial subgroups were not available.

Recipient of state or federal financial assistance programs (eg, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) or parental income within the lowest 2 quintiles nationally (<$41 187, 2014-2015 cohort; <$43 512, 2015-2016 cohort).

Students who grew up in a medically underserved area.

Family Income

A higher percentage of students with low income experienced attrition from medical school compared with students without low income (4.2% [345 of 8184] vs 2.3% [593 of 25 205]; P < .001). In unadjusted models, students with low income were 82% more likely to experience attrition from medical school compared with those without low income (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.59-2.09). This association remained in the fully adjusted model (aOR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15-1.54) (Table 2).

Underresourced Neighborhoods

Attrition rates were higher among students who grew up in an underresourced neighborhood than among students who did not (4.6% [277 of 5902] vs 2.4% [661 of 27 487]; P < .001). In unadjusted models, students who grew up in an underresourced neighborhood were 99% more likely than students who did not grow up in an underresourced neighborhood to experience attrition from medical school (OR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.73-2.30) (Table 2). Although adjusting for covariates reduced the odds of attrition, students who grew up in an underresourced neighborhood remained significantly more likely to experience attrition compared with those who did not grow up in an underresourced neighborhood (aOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.58) (Table 2).

Intersections Between Marginalized Identities

There were weak but significant positive correlations between all 3 marginalized identities, with φ coefficients of 0.22 (P < .001) for ethnic and racial identity and underresourced neighborhood, 0.24 (P < .001) for ethnic and racial identity and family income, and 0.23 (P < .001) for family income and underresourced neighborhood. Additive interaction analyses across marginalized identities revealed no significant pairwise interactions (P > .10) or 3-way interactions (P = .75) between ethnic and racial identity, underresourced neighborhood, and family income. A similar proportion of students who were URiM, grew up in an underresourced neighborhood, and had low income experienced attrition for academic and nonacademic reasons (URiM: 2.7% [115] vs 2.9% [128]; low income: 2.0% [162] vs 2.2% [183]; and underresourced neighborhood: 2.3% [134] vs 2.4% [143]).

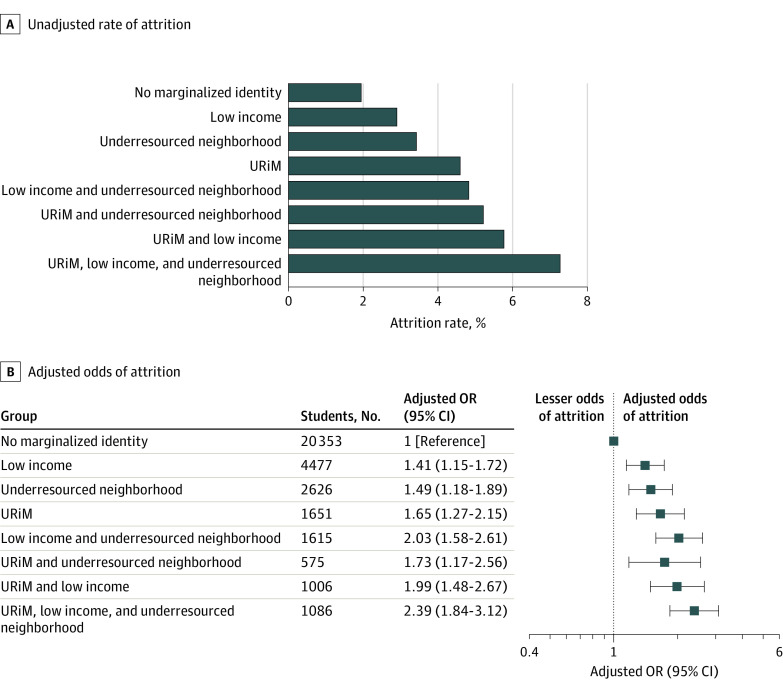

Medical student attrition increased as the number of coexisting marginalized identities increased (Figure, A). The attrition rate among students who had no marginalized identities (not URiM, did not have low income, and did not grow up in an underresourced neighborhood) was 1.9% (397 of 20 353), whereas the attrition rate among students who identified with 3 marginalized identities (URiM, had low income, and grew up in an underresourced neighborhood) was 3.7 times higher at 7.3% (79 of 1086) (P < .001) (Figure, A). Similar proportions of male and female students with 3 marginalized identities experience attrition from medical school (7.8% [39 of 500] vs 6.8% [40 of 586]; P = .54).

Figure. Intersections in Attrition From Medical School Among Race and Ethnicity, Family Income, and Underresourced Neighborhood Status.

Attrition among medical school matriculants in academic years 2014-2015 and 2015-2016 is reported. Underrepresented in medicine (URiM) included students who identified as Hispanic, non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or non-Hispanic Black/African American. B, Adjustment was made for sex and Medical College Admission Test scores. Squares represent adjusted odds ratios (ORs), and horizontal lines represent 95% CIs.

After adjusting for sex and MCAT scores, the adjusted odds of attrition also increased as the number of coexisting marginalized identities increased (Figure, B). Compared with students with no marginalized identities (not URiM, without low income, and did not grow up in an underresourced neighborhood), students with low income only were 41% more likely to experience attrition (aOR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.15-1.72), those who grew up in an underresourced neighborhood only were 49% more likely to experience attrition (aOR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.18-1.89), and those who identified as URiM only were 65% more likely to experience attrition (aOR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.27-2.15) (Figure, B). Students with 2 coexisting marginalized identities were at higher risk of attrition. Students who were URiM and had low income were 99% more likely to experience attrition (aOR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.48-2.67), students who were URiM and grew up in an underresourced neighborhood were 73% more likely to experience attrition (aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.17-2.56), and students with low income who grew up in an underresourced neighborhood were 103% more likely to experience attrition (aOR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.58-2.61) (Figure, B). In addition, compared with students who did not identify as URiM, did not have low income, and who did not grow up in an underresourced neighborhood, those with 3 coexisting marginalized identities (students who were URiM, had low income, and grew up in an underresourced neighborhood) had twice the odds of attrition from medical school (aOR, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.84-3.12) (Figure, B).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that although overall medical school attrition was low, there were substantial disparities in medical student attrition across individual (race and ethnicity and family income) and structural (growing up in an underresourced neighborhood) measures of inequality. Students who were URiM, had low income, and grew up in an underresourced neighborhood had at least 40% higher odds of attrition than their counterparts in each identity. Furthermore, differences in attrition among students increased as the number of marginalized identities increased, such that students who were URiM, had low income, and grew up in an underresourced neighborhood had the highest rates of attrition.

Although socioeconomic status and growing up in an underresourced neighborhood were each associated with medical student retention, results from our study showed an association between race and ethnicity and attrition. Irrespective of socioeconomic status or growing up in an underresourced neighborhood, students who were URiM had rates of attrition comparable to those among non-Hispanic White students who reported having low income and growing up in an underresourced neighborhood. Because our analysis accounted for standardized MCAT scores, these findings are unlikely to have been attributable to a lack of preparedness for the academic rigor of medical school.

Although the rate of attrition among students who were URiM has improved since 1995,11 in our study, a difference in the rate of attrition between students who were URiM and non-Hispanic White students persisted and warrants further investigation. Although the causes of these disparities are likely multifactorial, students who are URiM disproportionately experience interpersonal and structural barriers that impact their experience during medical school.20 These students also often lack identity-concordant mentors and role models, are frequently burdened with instances of minority tax (similar to the disparity in responsibility for underrepresented faculty),21,22 and commonly experience microaggressions and discrimination, including exposure to bigoted remarks by patients and faculty, bias in evaluations, and inequities in the receipt of academic awards.23,24,25,26,27,28,29 These experiences of social isolation, racism, and discrimination have been associated with burnout, depression, and attrition24 and highlight the need for medical schools to adopt a more proactive antiracism strategy.24,30,31,32

In this study, the higher rate of attrition among students with low income and students who grew up in an underresourced area suggests another important finding. Poverty and growing up in an underresourced neighborhood may have long-term consequences that are accentuated in medical training, such as lack of social and cultural capital to navigate medicine’s hidden curricula, social isolation from affluent majority peers, and financial stress,33,34 which may be associated with attrition among students with low income.35 Given the higher attrition rate among marginalized student groups, medical schools should consider reforms that dismantle structural inequities in medical culture and training that equate privilege with merit and physicians as an elite class of citizens. These reforms may begin with tuition and debt reform36,37,38 and purposeful partnership and support of local and national underresourced communities.39

Our study’s findings have potential implications for national medical school accrediting bodies. Training students to become physicians is an investment at both the national and institutional levels. Although the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) introduced diversity accreditation standards in 2009, regulatory accountability has focused on recruitment outcomes.9 Despite LCME requirements to report retention efforts, medical schools are not required to monitor or address disparities in medical student attrition or in early indicators of attrition, such as a leave of absence.18,35 Moving forward, an intentional focus by the LCME on retention outcomes for all students, in particular students from disadvantaged backgrounds, will be essential to ensure an equitable learning environment and diverse physician workforce.

In addition, our study’s findings may inform potential interventions for medical schools. These reforms could include robust financial and administrative support for diversity, equity, and inclusion offices and affinity groups representing marginalized groups. These offices should be populated with staff who are trained in critical race theory, health equity, and inclusive pedagogy and should be resourced to facilitate students’ preclinical and clinical curriculum, offering programming for students, faculty, and staff on implicit bias, structural competency, and civil discourse.40 Specifically, retention efforts should shift away from deficit-based to strength-based models that emphasize the recognition of individual students’ talents. Strength-based intervention models have been successful in aiding students in recognizing their value at the college level and have been associated with higher engagement, retention, and sense of professional identity formation.41

As medical schools strive to create an inclusive and equitable learning environment, a second consideration could be an aggressive effort to hire faculty from diverse backgrounds, who may offer critical mentorship opportunities for all medical students. In addition, interactions between medical students and a diverse faculty have been shown to be associated with reductions in implicit bias in the learning environment.42,43 To achieve a diverse faculty, retaining a diverse group of medical students is important because a diverse student body may attract recruitment of faculty from marginalized groups.44

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although we explored 3 sociodemographic identities, we recognize that there are other important identities, such as gender identity, sexual orientation, and disability status, that may influence student retention and are critical to cultivating a future physician workforce.45 The medical school learning environment may be associated with students’ likelihood to leave medical school.46 Students may also leave medical school for academic, financial, personal, and health reasons. Although attrition from medical school may be multifactorial (eg, academic struggles may exacerbate underlying health problems), a deeper understanding of why—personally and externally—students leave medical training may inform the development of student-centered initiatives to improve retention.

Conclusions

This retrospective cohort study found a significant association of medical student attrition with individual (race and ethnicity and family income) and structural (growing up in an underresourced neighborhood) measures of marginalization. Attrition of students with sociodemographic identities that have been marginalized in medicine may have implications for US health care delivery and the national research agenda.47 The LCME and medical schools should prioritize the evaluation of attrition rates across multiple marginalized identities to reduce retention gaps for marginalized students.

References

- 1.Saha S. Taking diversity seriously: the merits of increasing minority representation in medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):291-292. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alsan M, Garrick O, Graziani G. Does diversity matter for health? experimental evidence from Oakland. Am Econ Rev. 2019;109(12):4071-4111. doi: 10.1257/aer.20181446 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez LE, Bernet P. Diversity improves performance and outcomes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111(4):383-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):90-102. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, et al. The role of Black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(20):1305-1310. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605163342006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(3):296-306. doi: 10.2307/3090205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia AN, Kuo T, Arangua L, Pérez-Stable EJ. Factors associated with medical school graduates’ intention to work with underserved populations: policy implications for advancing workforce diversity. Acad Med. 2018;93(1):82-89. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bollinger LC. The need for diversity in higher education. Acad Med. 2003;78(5):431-436. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200305000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boatright DH, Samuels EA, Cramer L, et al. Association between the Liaison Committee on Medical Education’s diversity standards and changes in percentage of medical student sex, race, and ethnicity. JAMA. 2018;320(21):2267-2269. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Association of American Medical Colleges . Graduation rates and attrition rates of U.S. medical students. AAMC Data Snapshot. 2021;(October):1-2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrison G, Mikesell C, Matthew D. Medical school graduation and attrition rates. Analysis in Brief. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2007;7(2):1-2.

- 12.Brewer L, Grbic D. Medical students’ socioeconomic background and their completion of the first two years of medical school. Analysis in Brief. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2010;9(11):1-2.

- 13.Gill TM, Zang EX, Murphy TE, et al. Association between neighborhood disadvantage and functional well-being in community-living older persons. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(10):1297-1304. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.4260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tax Policy Center; Urban Institute & Brookings Institution . Household income quintiles. Published 2020. Accessed July 20, 2021. Updated January 25, 2022. https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/household-income-quintiles

- 15.Kim SJ, Peterson CE, Warnecke R, Barrett R, Glassgow AE. The uneven distribution of medically underserved areas in Chicago. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):556-564. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaskin DJ, Dinwiddie GY, Chan KS, McCleary RR. Residential segregation and the availability of primary care physicians. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(6):2353-2376. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01417.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaskin DJ, Thorpe RJ Jr, McGinty EE, et al. Disparities in diabetes: the nexus of race, poverty, and place. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2147-2155. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson DG. The AAMC study of medical student attrition: overview and major findings. J Med Educ. 1965;40(10):913-920. doi: 10.1097/00001888-196510000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson DG, Sedlacek WE. Retention by sex and race of 1968-1972 U.S. medical school entrants. J Med Educ. 1975;50(10):925-933. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197510000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teherani A, Hauer KE, Fernandez A, King TE Jr, Lucey C. How small differences in assessed clinical performance amplify to large differences in grades and awards: a cascade with serious consequences for students underrepresented in medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93(9):1286-1292. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orr CJ, McLaurin-Jiang S, Jamison SD. Diversity of mentorship to increase diversity in academic pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2021;147(4):e20193286. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ibrahim SA. Diversity in medical faculty and students. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2015326. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.15326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill KA, Samuels EA, Gross CP, et al. Assessment of the prevalence of medical student mistreatment by sex, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):653-665. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson N, Lett E, Asabor EN, et al. The association of microaggressions with depressive symptoms and institutional satisfaction among a national cohort of medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen M, Mason HRC, O’Connor PG, et al. Association of socioeconomic status with Alpha Omega Alpha honor society membership among medical students. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2110730. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, Moore E, Nunez-Smith M. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):659-665. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang A. Do individuals from low-income families belong in medicine? (yes!). in-House. January 27, 2021. https://in-housestaff.org/do-individuals-from-low-income-families-belong-in-medicine-yes-1903

- 28.Robins LS, Gruppen LD, Alexander GL, Fantone JC, Davis WK. A predictive model of student satisfaction with the medical school learning environment. Acad Med. 1997;72(2):134-139. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199702000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orom H, Semalulu T, Underwood W III. The social and learning environments experienced by underrepresented minority medical students: a narrative review. Acad Med. 2013;88(11):1765-1777. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a7a3af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hansell MW, Ungerleider RM, Brooks CA, Knudson MP, Kirk JK, Ungerleider JD. Temporal trends in medical student burnout. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):399-404. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.270753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Eacker A, et al. Race, ethnicity, and medical student well-being in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(19):2103-2109. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karani R. Enhancing the medical school learning environment: a complex challenge. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1235-1236. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3422-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, et al. Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults from all five sites of the moving to opportunity experiment, 2008-2010. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. March 14, 2013. Accessed November 20, 2021. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/ICPSR/studies/34563

- 34.Beagan BL. Everyday classism in medical school: experiencing marginality and resistance. Med Educ. 2005;39(8):777-784. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen M, Song SH, Ferritto A, Ata A, Mason HRC. Demographic factors and academic outcomes associated with taking a leave of absence from medical school. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2033570. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hopkins Tanne J. New York University Medical School gives students free tuition. BMJ. 2018;362:k3588. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinslow CJ. Tuition-free versus need-based, loan-free medical school: which will accomplish its goals? Acad Med. 2020;95(4):492. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas B. Free medical school tuition: will it accomplish its goals? JAMA. 2019;321(2):143-144. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.VanderWielen LM, Vanderbilt AA, Crossman SH, et al. Health disparities and underserved populations: a potential solution, medical school partnerships with free clinics to improve curriculum. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:27535-27535. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.27535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vela MB, Chin MH, Peek ME. Keeping our promise—supporting trainees from groups that are underrepresented in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(6):487-489. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2105270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Banks T, Dohy J. Mitigating barriers to persistence: a review of efforts to improve retention and graduation rates for students of color in higher education. High Educ Stud. 2019;9(1):118-131. [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Ryn M, Hardeman R, Phelan SM, et al. Medical school experiences associated with change in implicit racial bias among 3547 students: a medical student CHANGES study report. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1748-1756. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3447-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss J, Balasuriya L, Cramer LD, et al. Medical students’ demographic characteristics and their perceptions of faculty role modeling of respect for diversity. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2112795. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Page KR, Castillo-Page L, Wright SM. Faculty diversity programs in U.S. medical schools and characteristics associated with higher faculty diversity. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1221-1228. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c066d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meeks LM, Herzer K, Jain NR. Removing barriers and facilitating access: increasing the number of physicians with disabilities. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):540-543. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Marr JM, Chan SM, Crawford L, Wong AH, Samuels E, Boatright D. Perceptions on burnout and the medical school learning environment of medical students who are underrepresented in medicine. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220115. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maher BM, Hynes H, Sweeney C, et al. Medical school attrition—beyond the statistics a ten year retrospective study. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:13-13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, et al. Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults from all five sites of the moving to opportunity experiment, 2008-2010. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. March 14, 2013. Accessed November 20, 2021. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/ICPSR/studies/34563