Abstract

Objectives

Cancer is increasingly classified according to biomarkers that drive tumour growth and therapies developed to target them. In rare biomarker-defined cancers, randomised controlled trials to adequately assess targeted therapies may be infeasible. Extrapolating existing evidence of targeted therapy from common cancers to rare cancers sharing the same biomarker may reduce evidence requirements for regulatory approval in rare cancers. It is unclear whether guidelines exist for extrapolation. We sought to identify methodological guidance for extrapolating evidence from targeted therapies used for common cancers to rare biomarker-defined cancers.

Design

Scoping review.

Data sources

Websites of health technology assessment agencies, regulatory bodies, research groups, scientific societies and industry. EBM Reviews—Cochrane Methodology Register and Health Technology Assessment, Embase and MEDLINE databases (1946 to 11 May 2022).

Eligibility criteria

Papers proposing a framework or recommendations for extrapolating evidence for rare cancers, small populations and biomarker-defined cancers.

Data extraction and synthesis

We extracted framework details where available and guidance for components of extrapolation. We used these components to structure and summarise recommendations.

Results

We identified 23 papers. One paper provided an extrapolation framework but was not cancer specific. Extrapolation recommendations addressed six distinct components: strategies for grouping cancers as the same biomarker-defined disease; analytical validation requirements of a biomarker test to use across cancer types; strategies to generate control data when a randomised concurrent control arm is infeasible; sources to inform biomarker clinical utility assessment in the absence of prospective clinical evidence; requirements for surrogate endpoints chosen for the rare cancer; and assessing and augmenting safety data in the rare cancer.

Conclusions

In the absence of an established framework, our recommendations for components of extrapolation can be used to guide discussions about interpreting evidence to support extrapolation. The review can inform the development of an extrapolation framework for biomarker-targeted therapies in rare cancers.

Keywords: oncology, statistics & research methods, protocols & guidelines, molecular aspects, epidemiology, clinical trials

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review of methodological guidance on extrapolation of evidence was based on a contemporary and comprehensive search including websites of regulatory bodies, health technology assessment agencies, oncology societies and scientific databases.

Key recommendations of extrapolation components have been derived from multidisciplinary fields including governmental regulation, health technology, clinical trials, epidemiology and molecular pathology.

Although a wide variety of sources were included, the search was limited to publicly available guidance published in English.

Standard terminology for extrapolation of trial evidence in this setting is not well established which may limit the sensitivity of the search strategy to identify methodological guidance.

Introduction

Historically, cancer diagnosis has focused on managing patients according to the site of their primary cancer, such as breast cancer or colorectal cancer. Yet, as understanding of the molecular alterations driving cancer growth progresses, therapeutic developments focus on testing novel agents that target these alterations.1–3 This is termed a precision oncology approach. Using this approach, patients may be grouped together and managed based on shared biomarker profiles, as opposed to by the location of their primary cancer.

Initial trials of new molecularly targeted treatments are typically conducted in one tissue type. When these trials demonstrate a therapeutic benefit within a biomarker-defined subpopulation, the challenge is determining whether the biomarker is also ‘predictive’ of therapeutic benefit (identifies a subpopulation that responds differently to a particular treatment) in cancers of other tissue types that share the same biomarker. However, the role of a biomarker in carcinogenesis, cancer progression and prediction of treatment effect may differ between cancer tissue types.4–7 Patient prognosis regardless of treatment (‘natural history’) is also likely to differ between cancer tissue types even if they share the same biomarker status.8 9 Thus, randomised comparisons of a new therapy versus other available therapies in a specific cancer tissue-type cohort is the ideal evidence to minimise bias for estimation of the relative treatment effect on clinical outcomes and to assess cost-effectiveness.10 11

In cancer tissue types of high prevalence where biomarker prevalence is also high, referred to herein as ‘common cancers’, it is feasible to conduct randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in biomarker-defined subpopulations within each cancer tissue type. However, in cancer tissue types of low prevalence, particularly where biomarker prevalence is also low, RCTs within biomarker-defined subpopulations may not be feasible or provide timely results. A ‘rare cancer’ is formally defined as incidence of the disease less than 6–15 cases per 100 000 persons per year.12–14 In this paper, we use ‘rare cancer’ to mean cancer tissue types where the biomarker-defined subpopulation is sufficiently small that RCTs are deemed infeasible.

To illustrate, the V600E mutation of the v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homologue B (BRAF) gene is one such molecular alteration affecting tumour cell proliferation that is shared across several different primary cancers, from common to rarer cancer types.15 In patients with BRAF V600E mutated metastatic melanoma, treatment with vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, demonstrated improved overall survival (OS) compared with standard of care chemotherapy, dacarbazine, in a phase III RCT establishing the importance of determining tumour BRAF mutation status when determining treatment choice.16 17 In this example, melanoma is the common cancer expressing the molecular alteration. Beyond melanoma, vemurafenib was also tested in a basket trial, where patients are treated with the same treatment for different cancer tissue types sharing a common biomarker profile. In this instance, different cancer types all harbouring a BRAF V600 mutation (NCT01524978). Tumour response was seen in non-melanoma cancers including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (objective response rate (ORR) 42%) and Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) (ORR 43%).7 In melanoma, prevalence of BRAF V600E mutation is approximately 40%–60%.18 Mutation prevalence in ECD is comparable (~50%)19; however, ECD is a rare disease with approximately 800 reported cases in the literature and the exact incidence remains unknown.20 NSCLC is a common cancer but BRAF V600E mutation prevalence is low (1%–2%).21 To date, randomised evidence to confirm vemurafenib activity in ECD and NSCLC is unavailable.

In small populations such as in this scenario, extrapolation from similar populations where robust clinical trial evidence for therapy exists may help to infer treatment effect and lower thresholds of evidence may be accepted for regulatory or reimbursement approval.22 Extrapolation of treatment evidence from adult to paediatric populations has been used in this way23 and guidelines exist.24 25 Extrapolation from common to rare cancers sharing the same predictive biomarker has also been documented without reference to established guidelines.26 However, determining the predictive value of a biomarker across different cancer types requires careful consideration of the appropriateness of extending the existing trial evidence beyond specific cancer tissue-type cohorts.

The aim of this scoping review is to inform the development of guidance on assessing the effectiveness of molecular targeted treatments across different cancer types defined by the same biomarker—and concomitantly the value of the biomarker to predict treatment benefit for a rare cancer, where randomised trial evidence is only available for a common cancer type. Specifically, we sought to identify guidelines outlining approaches for extrapolation of evidence for targeted therapies from common to rare cancers sharing the same biomarker. The findings were used to develop a framework for extrapolation to assist key stakeholders, such as regulatory and reimbursement bodies, researchers and clinicians. This work will assist interpretation of existing data and make standardised, transparent decisions on whether extrapolation from common to rare cancers is appropriate.

Methods

Objectives

What methodological guidance frameworks exist for extrapolating evidence of relative treatment effect of targeted therapies versus standard of care treatment from common to rare cancers that share the same biomarker profile?

-

Specifically, do they address:

When it is appropriate to extrapolate evidence and to what extent?

What assumptions are made to extrapolate and what evidence is required to support these assumptions?

What methods can be used to appropriately extrapolate evidence?

Eligibility criteria

We included papers proposing a framework outlining criteria or methods for extrapolating evidence for targeted therapies from common to rare cancers sharing the same biomarker profile. As literature specific to this context was limited, we extended our review to include guidance for using extrapolation in trials assessing targeted therapies matched to a biomarker regardless of cancer type (‘pan-cancer’ trials), rare cancers or small populations. No limit was set for year of publication. We excluded papers that only discussed challenges or limitations, rather than providing an explicit framework or recommendations. Language was limited to English only.

Information sources and search strategy

We searched websites of health technology assessment (HTA) agencies, regulatory bodies, research groups, scientific societies and industry. We also searched MEDLINE, Embase, EBM Reviews—Cochrane Methodology Register and Health Technology Assessment databases (1946 to 11 May 2022). The full search strategy is available in the online supplemental appendices 1 and 2. Additional papers from reference lists of included papers and from discussions with content experts were also screened. Two reviewers performed the website and database searches and screened papers for eligibility (DC, SC). One reviewer extracted and synthesised data from the included papers (DC).

bmjopen-2021-058350supp001.pdf (58.5KB, pdf)

Data extraction and synthesis

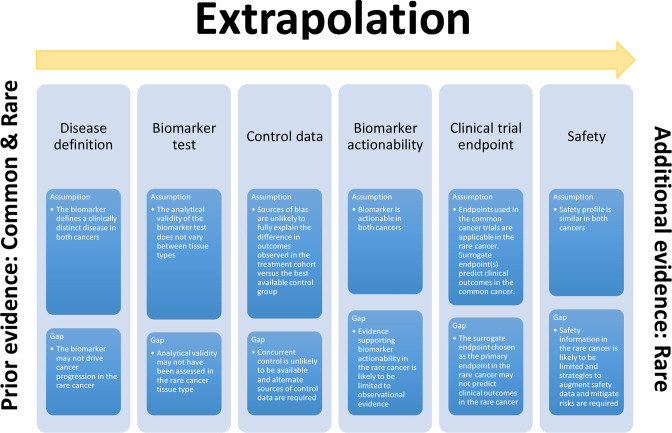

We extracted details from each paper of relevant frameworks and recommendations for evidence extrapolation. If a comprehensive framework does not exist, we then sought to identify, categorise and integrate recommendations relevant for extrapolation in this context into a single summary document. To organise this information, we defined six key evidence components for extrapolation based on evidence-based medicine principles for the evaluation of new tests and treatments27 28 as follows: disease definition, analytical validity of the biomarker test, control (‘standard of care’) data, biomarker actionability, endpoints and safety. In the absence of RCT evidence for the rare cancer, each component represents a critical assumption for extrapolation. We grouped individual recommendations for evidence to support these assumptions from each paper under the relevant component. We generated tables and figures to summarise the number of components addressed by each paper, recommendations for each component and potential evidence gaps that may limit extrapolation. We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews checklist for reporting.

Patient and public involvement

As this study was a scoping review of published methodological guidance, it was not appropriate to involve patients or the public in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Results

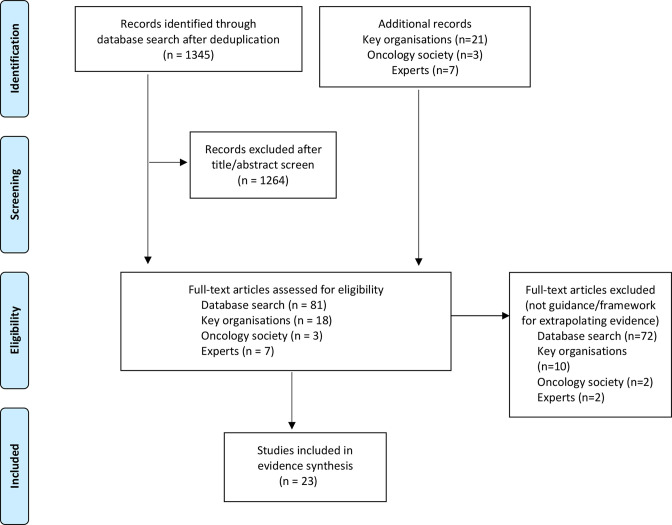

The database search yielded 1345 citations. A further 31 papers were retrieved from other sources. Screening of titles and abstracts identified 109 papers for full-text review of which 23 papers were included for evidence synthesis22 29–50 (figure 1, online supplemental appendix 3).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Characteristics of included papers

The majority of included papers were published by academic research groups (n=11, 48%), followed by regulatory bodies (n=6, 26%), HTA organisations (n=3, 13%) and scientific societies (n=3, 13%) (table 1). Publication year ranged from 2006 to 2021. The main focus of these papers were small population trials (n=10), pan-cancer trials of biomarker targeted therapies (n=10), biomarker actionability (n=10) and analytical validity of the biomarker test (n=7) (online supplemental table 1). Only one paper outlined an explicit extrapolation framework but was not specific to targeted therapies for cancer. Biomarker actionability was the most commonly addressed component (n=14) (tables 1 and 2, figure 2).

Table 1.

Extrapolation components addressed by papers

| Author group | Year | Extrapolation framework (n) | Components addressed (n) | Disease definition | Test analytical validity | Control data | Biomarker actionability | Endpoints | Safety |

| Research group | 0* | 2* | |||||||

| Seligson et al48 | 2021 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Dittrich50 | 2020 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Jørgensen49 | 2020 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Moscow et al40 | 2018 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Chakravarty et al37 | 2017 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Beckman et al 36 | 2016 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Meric-Bernstam et al 35 | 2015 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Van Allen et al33 | 2014 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Andre et al32 | 2014 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Vidwans et al 34 | 2014 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Sharma and Schilsky30 | 2011 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Regulatory body | 1* | 3* | |||||||

| FDA: Human gene therapy for rare diseases46 | 2020 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| FDA: Rare diseases: common issues in drug development44 | 2019 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| FDA: Developing targeted therapies in low-frequency molecular subsets of a disease43 | 2018 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Schuck et al (FDA)42 | 2018 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| EMA: Concept paper on extrapolation of efficacy and safety in medicine development22 | 2013 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| EMA: Guideline on clinical trials in small populations29 | 2006 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| HTA | 0* | 4* | |||||||

| Lengliné et al (TC-HAS)47 | 2021 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Morona et al (MSAC)45 | 2020 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Merlin et al (Adelaide HTA)31 | 2013 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Scientific society | 0* | 2* | |||||||

| Mateo et al (ESMO)39 | 2018 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Offin et al (ASCO)41 | 2018 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Li et al (AMP, ASCO, CAP)38 | 2017 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Total | 1 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 14 | 9 | 6 |

*Median number of components addressed by each author group.

AMP, Association for Molecular Pathology; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; CAP, College of American Pathologists; EMA, European Medicines Agency; ESMO, European Society for Medical Oncology; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; HTA, Health Technology Assessment organisations; MSAC, Medical Services Advisory Committee; TC-HAS, Transparency Committee of the French National Authority for Health (Haute Autorité de Santé).

Table 2.

Recommendations for extrapolation components

| Components | Author | Author group | Year |

| Extrapolation framework | |||

| Presents a framework for a systematic approach to set out when, to what extent and how extrapolation can be applied to extend information from a source population to make inferences for another target population. Elements of the framework include (1) a systematic synthesis of available data informing quantitative hypotheses for the similarity of the conditions and predicted response to intervention in the source and target population, (2) a reduced set of additional evidence requirements in the target population and selection of the type of extrapolation strategy (no extrapolation, partial extrapolation or full extrapolation), (3) validation of the hypotheses by emerging clinical or preclinical data or revision of the appropriateness of extrapolation if emerging data are not supportive, (4) interpretation of the limited data in the target population in the context of extrapolation, and (5) methods to address uncertainty and mitigate risk. | EMA: Concept paper on extrapolation of efficacy and safety in medicine development22 | Regulatory body | 2013 |

| Disease definition | |||

| A strong biological rationale as to why similar treatment effect could be expected across the different populations (or in this scenario cancer types) is a requirement for grouping as the same disease. | FDA: Developing targeted therapies in low-frequency molecular subsets of a disease43 | Regulatory body | 2018 |

| Schuck et al (FDA)42 | Regulatory body | 2018 | |

| Morona et al (MSAC)45 | HTA | 2020 | |

| Offin et al (ASCO)41 | Scientific society | 2018 | |

| Different types of evidence can support grouping strategies. Clinical studies are considered the strongest types of evidence. Preclinical studies and in silico (computational) evidence from a model system demonstrating similar drug effects within the proposed molecularly defined group are accepted as additional sources of evidence. Consistent treatment effects observed across more than one type of evidence increase the strength of evidence. | FDA: Human gene therapy for rare diseases46 | Regulatory body | 2020 |

| FDA: Developing targeted therapies in low-frequency molecular subsets of a disease43 | Regulatory body | 2018 | |

| Schuck et al (FDA)42 | Regulatory body | 2018 | |

| In defining the disease, a quantitative assessment of the similarity of disease between the source and target populations should be made based on aetiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and progression. Data sources can include in vitro preclinical, epidemiological studies, diagnostic studies, clinical trials and observational studies. | EMA: Concept paper on extrapolation of efficacy and safety in medicine development22 | Regulatory body | 2013 |

| Assays used to define the disease should be designed to detect and report all specific variants comprising the group expected to respond to better understand the molecular spectrum of the disease rather than limiting the definition to ‘biomarker-positive’ or ‘biomarker-negative’. | FDA: Human gene therapy for rare diseases46 | Regulatory body | 2020 |

| FDA: Developing targeted therapies in low-frequency molecular subsets of a disease43 | Regulatory body | 2018 | |

| Schuck et al (FDA)42 | Regulatory body | 2018 | |

| Merlin et al (Adelaide HTA)31 | HTA | 2013 | |

| Biomarker type may affect the generalisability of disease definition across cancer types. For binary or categorical biomarkers such as presence or absence of a particular mutation, the definitions of ‘biomarker-positive’ and ‘biomarker-negative’ may generalise across cancers. These biomarkers may also be able to be detected from liquid biopsy. However, for continuously measured biomarkers, such as protein expression, the cut-offs to define the ‘biomarker-positive’ group should be determined for each cancer type. This cut-off should be justified and could be provisionally informed by randomised exploratory studies stratified by the predictive biomarker. | Lengliné et al (TC-HAS)47 | HTA | 2021 |

| Beckman et al36 | Research group | 2016 | |

| A companion diagnostic test used to define the disease should be developed alongside clinical drug development to avoid the need for subsequent bridging studies. This test should be a central analytically validated assay to have an optimal definition of the biomarker-defined population. | Jørgensen49 | Research group | 2020 |

| Analytical validity of the biomarker test | |||

| The companion diagnostic test used should be analytically validated before the start of the clinical trial. Performance characteristics of the test (sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values) should be documented. | Jørgensen49 | Research group | 2020 |

| Moscow et al40 | Research group | 2018 | |

| Beckman et al36 | Research group | 2016 | |

| Sharma and Schilsky30 | Research group | 2011 | |

| FDA: Rare diseases: common issues in drug development44 | Regulatory body | 2019 | |

| FDA: Developing targeted therapies in low-frequency molecular subsets of a disease43 | Regulatory body | 2018 | |

| Schuck et al (FDA)42 | Regulatory body | 2018 | |

| Lengliné et al (TC-HAS)47 | HTA | 2021 | |

| Morona et al (MSAC)45 | HTA | 2020 | |

| Merlin et al (Adelaide HTA)31 | HTA | 2013 | |

| Mateo et al (ESMO)39 | Scientific society | 2018 | |

| For a test intended to be used across multiple cancer types, a central analytically validated assay should be used in order to avoid interassay variability. | Jørgensen49 | Research group | 2020 |

| For a test intended to be used across multiple cancer types, assessment of analytical accuracy of the assay in each cancer type against a reference or gold standard is required. | Beckman et al36 | Research group | 2016 |

| Moscow et al40 | Research group | 2018 | |

| Morona et al (MSAC)45 | HTA | 2020 | |

| A test with acceptable analytical validity in one cancer type may not be assumed to be valid in another cancer type. As an example, for biomarkers defined by protein expression, differences in tumour biology and tissue processing variables may alter the sensitivity of an assay. If a gold standard does not exist, concordance between the test used in the additional cancer type and the evidentiary standard (the test used in the pivotal trial that establishes the effectiveness of targeted treatment in the common cancer) should be demonstrated. Where the analytical sensitivity and specificity of the biomarker assay are the same between different tissue types, differences in biomarker prevalence alter the PPV (the proportion of biomarker ‘positive’ results correctly identifying the disease) and NPV (the proportion of biomarker ‘negative’ results correctly identifying absence of disease). As biomarker prevalence may differ substantially between cancer types, an assessment of the PPV and NPV of the test across the relevant prevalence range for the cancers being targeted is recommended. |

Morona et al (MSAC)45 | HTA | 2020 |

| Merlin et al (Adelaide HTA)31 | HTA | 2013 | |

| Tumour molecular profiling technologies are rapidly advancing. Thus, both tests using different technology (eg, next generation sequencing as opposed to PCR or Sanger sequencing to detect a mutation) or different assay (eg, two different commercial PCR assays to detect BRAF V600E mutation) to be used require validation in the new cancer type. | Moscow et al40 | Research group | 2018 |

| Standardisation of laboratory procedures for sample collection, storage and processing between laboratories currently organised according to cancer tissue type rather than test or technology type is recommended to improve interlaboratory concordance and test reproducibility. | Beckman et al36 | Research group | 2016 |

| Control (standard of care) data | |||

| If randomisation to a concurrent control arm is not feasible in the rare cancer group, alternative sources of control data will be required. Natural history data for the rare cancer can be used as a historical control. | Dittrich50 | Research group | 2020 |

| Mateo et al39 | Research group | 2018 | |

| Beckman et al36 | Research group | 2016 | |

| Sharma and Schilsky30 | Research group | 2011 | |

| FDA: Human gene therapy for rare diseases46 | Regulatory body | 2020 | |

| FDA: Rare diseases: common issues in drug development44 | Regulatory body | 2019 | |

| EMA: Guideline on clinical trials in small populations29 | Regulatory body | 2006 | |

| Lengliné et al (TC-HAS)47 | HTA | 2021 | |

| Morona et al (MSAC)45 | HTA | 2020 | |

| Natural history data should be from the biomarker-defined population to account for any difference in prognosis between biomarker-positive and biomarker-negative subgroups. | Dittrich50 | Research group | 2020 |

| Sharma and Schilsky30 | Research group | 2011 | |

| Lengliné et al (TC-HAS)47 | HTA | 2021 | |

| Morona et al (MSAC)45 | HTA | 2020 | |

| Clinically and genetically annotated retrospective cohorts of patients with a rare cancer or cancer with rare genetic alterations should be established. All data from basket trials should be recorded in registries. These data can be reused as a prespecified external control. | Lengliné et al (TC-HAS)47 | HTA | 2021 |

| RWE (observational evidence derived from clinical use outside of an RCT) from genomic databases annotated with clinical outcome data can be used to assemble historical control benchmarks. | Mateo et al (ESMO)39 | Scientific society | 2018 |

| Concurrent prospective registry controls can mitigate bias from outcome differences as a result of stage migration and improved supportive treatment or available therapies over time. Shared controls can be used for multiple rare cancer types to reduce sample size requirements. This will be limited to cancer types with the same control therapy. | Beckman et al36 | Research group | 2016 |

| Patients as their own controls where time to disease progression on targeted therapy may be compared with that from their previous treatment can be used. | FDA: Human gene therapy for rare diseases46 | Regulatory body | 2020 |

| Effect size of treatment in the common cancer (reference case) can be benchmarked against prognostic data from biomarker-positive rare cancer historical controls. | Morona et al (MSAC)45 | HTA | 2020 |

| The threshold to be met for the assessment of efficacy in the rare cancer depends on the historical control rare of the biomarker-positive cancer type. | Dittrich50 | Research group | 2020 |

| Biomarker actionability | |||

| Biomarker actionability in one cancer type may or may not extrapolate to another cancer type as molecular pathways driving cancer progression and/or resistance mechanisms can differ between cancer types despite sharing the same biomarker. Frameworks have been proposed that classify biomarkers or molecular alterations into tiers, according to actionability, and can inform this assessment in each cancer type. | Chakravarty et al37 | Research group | 2017 |

| Meric-Bernstam et al35 | Research group | 2015 | |

| Van Allen et al33 | Research group | 2014 | |

| Vidwans et al34 | Research group | 2014 | |

| Andre et al32 | Research group | 2014 | |

| Mateo et al (ESMO)39 | Scientific society | 2018 | |

| Li et al (AMP, ASCO, CAP)38 | Scientific society | 2017 | |

| If prospective clinical evidence is unavailable in the rare cancer, other types of evidence are accepted to inform functional relevance and actionability of the biomarker and include: | |||

|

Seligson et al48 | Research group | 2021 |

|

FDA: Developing targeted therapies in low-frequency molecular subsets of a disease43 | Regulatory body | 2018 |

| EMA: Concept paper on extrapolation of efficacy and safety in medicine development22 | Regulatory body | 2013 | |

| Morona et al (MSAC)45 | HTA | 2020 | |

| Offin et al (ASCO)41 | Scientific society | 2018 | |

|

Vidwans et al34 | Research group | 2014 |

|

Van Allen et al33 | Research group | 2014 |

| Vidwans et al34 | Research group | 2014 | |

| Schuck et al (FDA)42 | Regulatory body | 2018 | |

| EMA: Concept paper on extrapolation of efficacy and safety in medicine development22 | Regulatory body | 2013 | |

| ‘Linked evidence approach’—linking evidence for the test, biomarker actionability and treatment outcomes from different sources, provided they are generated in an internally valid manner from similar patient populations, to build a chain of arguments as an alternative when RCT evidence is not feasible. | Merlin et al (Adelaide HTA)31 | HTA | 2013 |

| Data assessing the functional consequence of genomic alterations must be generated in the cancer type for which the therapy is being considered as the same alteration can have distinct epistatic interactions across different cancer types. | Dittrich50 | Research group | 2020 |

| Longitudinal, multiomic (genomic, RNA sequencing, methylomic, proteomic) assessment of cancers can be used to better predict treatment response and understand resistance mechanisms across cancer types and inform biomarker actionability in the rare cancer. | Seligson et al48 | Research group | 2021 |

| The type of molecular alteration may be important for whether actionability can be extrapolated to a different cancer type. Examples of therapies exhibiting activity across cancer types are either targeting the host immune system or kinase fusions. However, very few therapies targeting single nucleotide variants and amplifications have exhibited histology-agnostic activity. | Jørgensen49 | Research group | 2020 |

| Evidence of treatment effect in the biomarker-negative population is required to inform biomarker actionability. If this is limited in the rare cancer, if early studies addressed this question whereby patients for whom no signal of efficacy was subsequently excluded in a seamless oncology trial approach, these studies may reasonably be used as best available evidence in the biomarker-negative subgroup in the rare cancer. | Morona et al (MSAC)45 | HTA | 2020 |

| Postapproval studies and RWE, including large non-randomised studies, should be used to confirm or refute regulatory decisions based on limited evidence supporting actionability in the rare cancer. | Seligson et al48 | Research group | 2021 |

| Moscow et al40 | Research group | 2018 | |

| Schuck et al42 | Regulatory body | 2018 | |

| Clinical trial endpoints | |||

| Data on clinically relevant outcomes may not be available in rare cancers. In this scenario, surrogate endpoints may need to be used for extrapolation. Recommendations on the choice of surrogate endpoint(s) include: | |||

|

FDA: Human gene therapy for rare diseases46 | Regulatory body | 2020 |

| EMA: Concept paper on extrapolation of efficacy and safety in medicine development22 | Regulatory body | 2013 | |

| EMA: Guideline on clinical trials in small populations29 | Regulatory body | 2006 | |

|

FDA: Rare diseases: common issues in drug development44 | Regulatory body | 2019 |

|

FDA: Rare diseases: common issues in drug development44 | Regulatory body | 2019 |

| EMA: Guideline on clinical trials in small populations29 | Regulatory body | 2006 | |

|

Moscow et al40 | Research group | 2018 |

| FDA: Human gene therapy for rare diseases46 | Regulatory body | 2020 | |

| EMA: Guideline on clinical trials in small populations29 | Regulatory body | 2006 | |

|

FDA: Human gene therapy for rare diseases46 | Regulatory body | 2020 |

|

Lengliné et al (TC-HAS)47 | HTA | 2021 |

| When a targeted therapy has demonstrated efficacy and safety based on clinical endpoints in a population composed of various molecular subtypes all thought to result in the same clinical disease, treatment effect can be extrapolated to additional putatively similar molecular subtypes based on pharmacodynamic or surrogate endpoints. | FDA: Developing targeted therapies in low-frequency molecular subsets of a disease43 | Regulatory body | 2018 |

| A single trial that pools different cancer-type cohorts together is only acceptable if tumour response rates are homogeneous. If tumour response is heterogeneous, separate trials for each cancer type are required. | Seligson et al48 | Research group | 2021 |

| Dittrich50 | Research group | 2020 | |

| When results of treatment are based on short-term and intermediate-term endpoints, confirmation of treatment benefit in randomised trials is required. This may occur in the postapproval setting. If the treatment effect in a non-randomised study is strong, only a small confirmatory randomised trial is required. | Dittrich50 | Research group | 2020 |

| Safety | |||

| When safety information is limited in the rare cancer, the following sources can augment safety data: (1) natural history studies, (2) auxiliary safety cohorts, (3) expanded access programmes and postmarketing studies in the rare cancer group, and (4) studies of the targeted therapy in other indications or studies of similar drugs. | FDA: Rare diseases: common issues in drug development44 | Regulatory body | 2019 |

| EMA: Guideline on clinical trials in small populations29 | Regulatory body | 2006 | |

| A quantitative assessment of existing data from clinical, preclinical and in vitro data to predict the degree of similarity in treatment response on safety outcomes and validation of this prediction from emerging data is recommended. | EMA: Concept paper on extrapolation of efficacy and safety in medicine development22 | Regulatory body | 2013 |

| In the rare cancer, postmarketing safety studies or risk mitigation measures beyond labelling and routine pharmacovigilance are recommended. | Moscow et al40 | Research group | 2018 |

| FDA: Rare diseases: common issues in drug development44 | Regulatory body | 2019 | |

| FDA: Developing targeted therapies in low-frequency molecular subsets of a disease43 | Regulatory body | 2018 | |

| EMA: Guideline on clinical trials in small populations29 | Regulatory body | 2006 | |

| Risks associated with misclassification of the biomarker should also be considered when assessing safety. | Morona et al (MSAC)45 | HTA | 2020 |

| Merlin et al (Adelaide HTA)31 | HTA | 2013 |

AMP, Association for Molecular Pathology; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; CAP, College of American Pathologists; EMA, European Medicines Agency; ESMO, European Society for Medical Oncology; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; HTA, Health Technology Assessment organisations; MSAC, Medical Services Advisory Committee; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RWE, real-world evidence; TC-HAS, Transparency Committee of the French National Authority for Health (Haute Autorité de Santé).

Figure 2.

Extrapolation components, assumptions and supportive evidence. This figure depicts extrapolation of evidence from a common cancer to a rare cancer sharing the same biomarker profile. Assumptions made for extrapolation and the potential gaps in evidence supporting these assumptions for each component are summarised.

Extrapolation framework

Our search did not identify any published guidelines or framework explicitly outlining a comprehensive approach for extrapolating evidence for targeted therapies from common to rare cancers sharing the same biomarker. However, we identified papers reporting individual recommendations in relevant fields and incorporated these into one or more components to develop an extrapolation framework for assessing biomarker-targeted therapies in rare cancers. One paper by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) outlined an extrapolation framework for medicines in general and proposed a systematic approach for when, to what extent and how extrapolation can be applied for new medicines.22 Although this framework is not cancer specific, the same extrapolation principles can be applied to targeted treatments for biomarker-defined cancers. Elements of the EMA framework as well as recommendations made by the other papers are organised under the relevant component and summarised in table 2 and discussed below.

Defining the disease

A principal assumption for extrapolation is that there is strong biological rationale that both cancers can be grouped as the same biomarker-defined disease, characterised by similar response to the targeted therapy being assessed. A quantitative assessment of the similarity of disease should be made and can be based on clinical, preclinical and mechanistic data sources. To define the disease, a companion diagnostic assay should be developed alongside the therapy that detects and reports all specific molecular variants, across cancer types, comprising the group expected to respond to the targeted therapy. For continuously measured biomarkers, the cut-offs to define the ‘biomarker-positive’ group should be determined for each cancer type.

Analytical validity of the biomarker test

Critical to defining the biomarker-defined disease is an analytically valid test that accurately, reproducibly and reliably identifies the biomarker. An assumption for extrapolation is that the biomarker test has been analytically validated against a reference or gold standard before the start of the clinical trial in both the common and rare cancers. A test with acceptable analytical validity in one cancer type may not be assumed to be valid in another cancer type. As biomarker prevalence may differ substantially between cancer types, an assessment of the positive predictive value (the proportion of biomarker ‘positive’ results correctly identifying the disease) and negative predictive value (the proportion of biomarker ‘negative’ results correctly identifying absence of disease) of the test across the relevant prevalence range for the cancers being targeted is recommended.

Control (standard of care) data

An assumption made for extrapolation is that reliable control data are available for the biomarker-defined rare cancer. To compare the effect of a targeted therapy with the effect of non-targeted therapies and differentiate treatment effect from the prognosis (natural history) of the biomarker-positive cancer subgroup, outcome data of biomarker-positive patients treated with non-targeted therapy (control arm) are essential. Concurrent standard of care data from a well-conducted RCT are the ideal source of control data to minimise risk of bias. Such data are usually available for common but not rare cancers. If randomisation to a concurrent control arm is not feasible in the rare cancer group, alternative sources of control data will be required. Natural history data from the biomarker-defined subpopulation of the rare cancer can be used as a historical control. Data sources include clinically and genetically annotated cohorts of patients with rare cancers from registries, basket trials and real-world evidence (RWE). Concurrent prospective registry controls have the advantage of mitigating bias from outcome differences as a result of stage migration and improved supportive treatment or available therapies over time.

Biomarker actionability

The actionability of a biomarker is measured by the ability of decisions based on the biomarker to improve health outcomes. For a predictive biomarker, this depends on how well it predicts treatment effect (clinical validity of a biomarker). Assessment of both biomarker-positive and biomarker-negative groups receiving targeted therapy versus non-targeted therapy is required to differentiate between the prognostic value of the biomarker to predict survival (assessed by comparing clinical outcomes for the biomarker-positive vs negative groups receiving non-targeted therapy) and the predictive value of the biomarker to predict treatment effect (assessed by comparing the relative treatment effect of targeted vs non-targeted therapy for the biomarker-positive vs negative groups).51 Prospective clinical trial evidence is essential to establish biomarker actionability in the common cancer and if trial evidence is also available in the rare cancer, extrapolation of evidence is not required. However, if this is not available in the rare cancer and extrapolation is used, a key assumption is that the biomarker is similarly actionable in the rare cancer.

Even if biomarker actionability is established in one cancer type, actionability may or may not extrapolate to another cancer type as molecular pathways driving cancer progression and/or resistance mechanisms can differ between cancer types despite having the same biomarker. Frameworks classifying biomarkers or molecular alterations into tiers, according to actionability, can inform this assessment in each cancer type. These frameworks are based on the strength of evidence supporting biomarker actionability. Sources supporting tier classification in decreasing order of level of evidence include clinical practice guidelines, prospective clinical evidence, retrospective clinical evidence, observational evidence, RWE from large-scale cancer mutation databases and registry data. High tier associations in one cancer type may be downgraded in another cancer type if the level of evidence in the latter is lower. If prospective clinical evidence is unavailable in the rare cancer, lower levels of evidence generated in the rare cancer tissue type are accepted to inform functional relevance and actionability of the biomarker, including preclinical evidence, biological rationale, systems biology and in silico evidence. Where regulatory decisions have been based on limited evidence supporting actionability in the rare cancer, postapproval studies should be used to confirm treatment benefit.

Clinical trial endpoints

Endpoints used for extrapolation are assumed to be applicable to both common and rare cancers. Progression-free survival (PFS) and OS are often used in common cancer trials to measure clinically relevant treatment outcomes, but PFS and OS data may not be available in rare cancers. In this scenario, other surrogate endpoints that are more sensitive or able to be measured earlier may be used to extrapolate treatment effect from the common cancer to the rare cancer. Extrapolation is accepted when treatment effects in both cancers, based on surrogate endpoints, are homogeneous. The surrogate endpoint chosen should reasonably be likely to predict clinical benefit. When the surrogate used is the rate of tumour shrinkage, assessment should be standardised, and the duration of response, which is more clinically relevant than tumour shrinkage rate alone, should also be analysed. Treatment results based on surrogate endpoints need confirmation of clinical benefit in postapproval studies.

Safety

Risk-benefit assessment of therapies requires data on both safety and effectiveness. However, decisions for extrapolating evidence for either safety or effectiveness are usually made independently. Clinical studies acceptable for extrapolating treatment effectiveness may not be applicable for extrapolating safety due to differences in endpoints chosen and study power requirements for rare adverse events. An assumption made for extrapolating safety data is that the safety profile of targeted therapy is the same in both the common and rare cancers. However, the safety profile of the same therapy may differ when used in different cancer tissue types.

The safety profile of therapies is generally informed by randomised concurrently controlled studies and supplemented by phase IV and RWE capturing use in broader populations compared with the highly selected populations recruited to phase III RCTs. While safety information is available in the common cancer it may be limited in the rare cancer. In this scenario, sources to augment safety data include natural history studies, auxiliary safety cohorts, expanded access programme and postmarketing studies. In the rare cancer, postmarketing safety studies or risk mitigation measures beyond labelling and routine pharmacovigilance are recommended.

In addition to the risks associated with treatment adverse events, risks associated with misclassification from the biomarker test and subsequent incorrect treatment recommendations should also be considered when assessing safety.

Discussion

This scoping review identified 23 guidance papers published by research groups, regulatory bodies, HTA organisations and scientific societies of which only one paper presented an explicit extrapolation framework for medicines. Principles from this framework may be applied to our setting but there was no framework for extrapolation to generate evidence specifically for biomarker-targeted therapies in rare cancers. Each of the other 22 papers made recommendations for one or more components of extrapolation.

With rapid advances in molecular profiling technologies, cancers are increasingly partitioned into smaller subgroups according to potentially actionable biomarkers.52 With dwindling sample sizes available for recruitment to trials, the traditional trial design paradigm is becoming unfeasible for novel therapies targeted to these biomarker-defined rare cancers. Informally, extrapolation of evidence is already being used for assessing targeted therapies in biomarker-defined rare cancers for regulatory approval.26 Our findings of similar recommendations for individual components of extrapolation from different groups indicate broad consensus. However, these recommendations are not yet integrated into a comprehensive framework for judging whether extrapolation should be used and how. Additionally, no paper outlined trial design strategies for generating new evidence in rare cancers in the context of using prior evidence from common cancers sharing the same biomarker. Overall, statistical recommendations for extrapolation were limited though four papers raised the potential for incorporating adaptive designs including Bayesian approaches using prior information from the common cancer.22 42 48 50

Strengths and limitations

There is an immediate and growing need to explore novel methods to assess evidence for biomarker-defined rare cancers when RCTs are unfeasible. This is the first scoping review aiming to identify if and to what extent guidance exists on extrapolation to address this need. A key finding is there is no extrapolation framework specific for rare biomarker-defined cancers. This review is timely to summarise in a single document recommendations of commonly accepted components of extrapolation relevant to biomarker-targeted therapies for rare cancers to guide discussions and stimulate debate about best methods for addressing each.

There are potential limitations to our work. First, given we were unable to identify any papers that fit our a priori research question, it became necessary to take a pragmatic approach and broaden the eligibility criteria to include papers that addressed one or more components of extrapolation that would be useful to inform such a framework. Second, we relied on published or publicly available guidance and may have missed unpublished documents. Third, we limited our search to documents in English due to practical restraints and may have missed extrapolation guidance published in other languages. Fourth, standard terminology for extrapolation of trial evidence in this setting is not well established which may limit the sensitivity of the search strategy to identify methodological guidance.

Application and future directions

This summary document has systematically identified distinct components for extrapolation, namely disease definition, analytical validity of the biomarker test, control (‘standard of care’) data, biomarker actionability, clinical trial endpoints and safety. This framework is specific for our setting of extrapolating data from common to rare cancers sharing the same biomarker treated with targeted therapy, and is not designed for other cancer and non-cancer settings.

This work is valuable to guide discussions between key stakeholders in drug development, regulatory approval and reimbursement when extrapolated evidence from other cancers is being used to interpret evidence for targeted therapies in rare cancers. This work is also relevant for clinical trialists designing future studies in rare cancers where extrapolated data from common cancers are used to justify the trial design. It can also inform trialists designing studies in common cancers so that data generated would be useful and easily applicable for extrapolation in the future. The work is also relevant for clinicians as it outlines important considerations when using extrapolated evidence from common to rare cancers to make targeted treatment recommendations for their patients.

Ongoing work will articulate criteria for assessing the level of uncertainty to promote standardised decision-making for clinical and regulatory decisions and facilitate transparent discussion between key stakeholders in the development and evaluation of molecular targeted therapies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DC, SC, SJL, JS and CKL have contributed to the conception and design of the study. DC and SC have contributed to the acquisition of data. DC, SJL and CKL contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors have contributed to the final design and focus of the scoping review. DC drafted the manuscript. All authors have made contributions to the drafting and revising of the article. All authors have read, reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript before submission. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. DC and CKL are responsible for the overall content as guarantor and accept full responsibility for the work, the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: This work was supported by an NHMRC Postgraduate Research Scholarship (Medical-Dental) (SC0798) and Postgraduate Research Supplementary Scholarship in Oncology.

Competing interests: This scoping review was undertaken as part of DC’s PhD studies for which she received an NHMRC Postgraduate Research Scholarship (Medical-Dental) (SC0798) and Postgraduate Research Supplementary Scholarship in Oncology. She has also received support from Novartis for attending scientific meetings. JS declares research grants to the University of Sydney (Bayer, Roche, BMS, AstraZeneca, AbbVie, MSD, Pfizer). CKL declares honoraria (AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Amgen, Takeda, Yuhan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, MSD Oncology), consulting or advisory role (Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Yuhan, Amgen) and research funding (AstraZeneca, Roche, Merck KGaA).

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011;144:646–74. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med 2015;372:793–5. 10.1056/NEJMp1500523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsimberidou AM, Fountzilas E, Nikanjam M, et al. Review of precision cancer medicine: evolution of the treatment paradigm. Cancer Treat Rev 2020;86:102019. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGrail DJ, Pilié PG, Rashid NU, et al. High tumor mutation burden fails to predict immune checkpoint blockade response across all cancer types. Ann Oncol 2021;32:661–72. 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rousseau B, Foote MB, Maron SB, et al. The spectrum of benefit from checkpoint blockade in hypermutated tumors. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1168–70. 10.1056/NEJMc2031965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature 2012;483:100–3. 10.1038/nature10868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyman DM, Puzanov I, Subbiah V, et al. Vemurafenib in multiple nonmelanoma cancers with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med 2015;373:726–36. 10.1056/NEJMoa1502309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med 2001;344:783–92. 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bang Y-J, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:687–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sargent DJ, Conley BA, Allegra C, et al. Clinical trial designs for predictive marker validation in cancer treatment trials. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2020–7. 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandrekar SJ, Sargent DJ. Clinical trial designs for predictive biomarker validation: theoretical considerations and practical challenges. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4027–34. 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Society of Medical Oncology . Rare Cancers - Europe and Asia. Available: https://www.esmo.org/policy/rare-cancers-europe-and-asia [Accessed 26 May 2022].

- 13.Cancer Australia . Rare and less common cancers. Available: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/about-us/news/rare-and-less-common-cancers [Accessed 26 May 2022].

- 14.National cancer Institute. Available: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/rare-cancer [Accessed 26 May 2022].

- 15.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002;417:949–54. 10.1038/nature00766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2507–16. 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman PB, Robert C, Larkin J, et al. Vemurafenib in patients with BRAFV600 mutation-positive metastatic melanoma: final overall survival results of the randomized BRIM-3 study. Ann Oncol 2017;28:2581–7. 10.1093/annonc/mdx339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng L, Lopez-Beltran A, Massari F, et al. Molecular testing for BRAF mutations to inform melanoma treatment decisions: a move toward precision medicine. Mod Pathol 2018;31:24–38. 10.1038/modpathol.2017.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haroche J, Charlotte F, Arnaud L, et al. High prevalence of BRAF V600E mutations in Erdheim-Chester disease but not in other non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses. Blood 2012;120:2700–3. 10.1182/blood-2012-05-430140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goyal G, Heaney ML, Collin M, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease: consensus recommendations for evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment in the molecular era. Blood 2020;135:1929–45. 10.1182/blood.2019003507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leonetti A, Facchinetti F, Rossi G, et al. Braf in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Pickaxing another brick in the wall. Cancer Treat Rev 2018;66:82–94. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.European Medicines Association . Concept paper on extrapolation of efficacy and safety in medicine development, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunne J, Rodriguez WJ, Murphy MD, et al. Extrapolation of adult data and other data in pediatric drug-development programs. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1242–9. 10.1542/peds.2010-3487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Leveraging existing clinical data for extrapolation to pediatric uses of medical devices guidance for industry and food and drug administration staff, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.European Medicines Association . Reflection paper on the use of extrapolation in the development of medicines for paediatrics, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odogwu L, Mathieu L, Blumenthal G, et al. FDA Approval Summary: Dabrafenib and Trametinib for the Treatment of Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers Harboring BRAF V600E Mutations. Oncologist 2018;23:740–5. 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Cook DJ. Users' guides to the medical literature. II. How to use an article about therapy or prevention. B. what were the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? evidence-based medicine Working group. JAMA 1994;271:59–63. 10.1001/jama.271.1.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Sackett DL. Users' guides to the medical literature. III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test. B. what are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? the evidence-based medicine Working group. JAMA 1994;271:703–7. 10.1001/jama.271.9.703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.European Medicines Association . Guideline on clinical trials in small populations, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma MR, Schilsky RL. Role of randomized phase III trials in an era of effective targeted therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011;9:208–14. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merlin T, Farah C, Schubert C, et al. Assessing personalized medicines in Australia: a national framework for reviewing codependent technologies. Med Decis Making 2013;33:333–42. 10.1177/0272989X12452341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andre F, Mardis E, Salm M, et al. Prioritizing targets for precision cancer medicine. Ann Oncol 2014;25:2295–303. 10.1093/annonc/mdu478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Allen EM, Wagle N, Stojanov P, et al. Whole-Exome sequencing and clinical interpretation of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor samples to guide precision cancer medicine. Nat Med 2014;20:682–8. 10.1038/nm.3559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vidwans SJ, Turski ML, Janku F, et al. A framework for genomic biomarker actionability and its use in clinical decision making. Oncoscience 2014;1:614–23. 10.18632/oncoscience.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meric-Bernstam F, Johnson A, Holla V, et al. A decision support framework for genomically informed investigational cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107:djv098. 10.1093/jnci/djv098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beckman RA, Antonijevic Z, Kalamegham R, et al. Adaptive design for a confirmatory basket trial in multiple tumor types based on a putative predictive biomarker. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2016;100:617–25. 10.1002/cpt.446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips SM, et al. OncoKB: a precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis Oncol 2017;2017:1–16. 10.1200/PO.17.00011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li MM, Datto M, Duncavage EJ, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of sequence variants in cancer: a joint consensus recommendation of the association for molecular pathology, American Society of clinical oncology, and College of American pathologists. J Mol Diagn 2017;19:4–23. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mateo J, Chakravarty D, Dienstmann R, et al. A framework to RANK genomic alterations as targets for cancer precision medicine: the ESMO scale for clinical Actionability of molecular targets (ESCAT). Ann Oncol 2018;29:1895–902. 10.1093/annonc/mdy263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moscow JA, Fojo T, Schilsky RL. The evidence framework for precision cancer medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018;15:183–92. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Offin M, Liu D, Drilon A. Tumor-Agnostic drug development. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2018;38:184–7. 10.1200/EDBK_200831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schuck RN, Woodcock J, Zineh I, et al. Considerations for developing targeted therapies in low-frequency molecular subsets of a disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2018;104:282–9. 10.1002/cpt.1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Developing targeted therapies in low-frequency molecular subsets of a disease, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Rare diseases: common issues in drug development guidance for industry, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morona J, Wyndham A, Scott P. Discussion paper on pan-tumour biomarker testing to determine eligibility for targeted treatment, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 46.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Human gene therapy for rare diseases guidance for industry, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lengliné E, Peron J, Vanier A, et al. Basket clinical trial design for targeted therapies for cancer: a French national authority for health statement for health technology assessment. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:e430–4. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00337-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seligson ND, Knepper TC, Ragg S, et al. Developing drugs for Tissue-Agnostic indications: a paradigm shift in Leveraging cancer biology for precision medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021;109:334–42. 10.1002/cpt.1946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jørgensen JT. Site-agnostic biomarker-guided oncology drug development. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2020;20:583–92. 10.1080/14737159.2020.1702521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dittrich C. Basket trials: from tumour gnostic to tumour agnostic drug development. Cancer Treat Rev 2020;90:102082. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee CK, Lord SJ, Coates AS, et al. Molecular biomarkers to individualise treatment: assessing the evidence. Med J Aust 2009;190:631–6. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02592.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jordan EJ, Kim HR, Arcila ME, et al. Prospective comprehensive molecular characterization of lung adenocarcinomas for efficient patient matching to Approved and emerging therapies. Cancer Discov 2017;7:596–609. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-058350supp001.pdf (58.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.