ABSTRACT

Context:

Despite increasing utilization of fusion to treat degenerative pathology, few studies have evaluated outcomes with pelvic fixation (PF). This is the first large-scale database study to compare multilevel fusion with and without PF for degenerative lumbar disease.

Aim:

The aim of this study was to compare the 30-day outcomes of multilevel lumbar fusion with and without PF.

Settings and Design:

This was a retrospective cohort study.

Subjects and Methods:

Lumbar fusion patients were identified using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Regression was utilized to analyze readmission, reoperation, morbidity, and specific complications and to evaluate for predictors thereof.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Student's t-test was used for continuous variables and Chi-squared or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables. Variables significant in the univariate analyses (P < 0.05) and PF were then evaluated for significance as independent predictors and control variables in a series of multivariate logistic regression analyses of primary outcomes.

Results:

We identified 38,413 patients. PF predicted 30-day readmission and morbidity. PF was associated with greater reoperation in univariate analysis, but not in multivariate analyses. PF predicted deep wound infections, organ-space infections, pulmonary complications, urinary tract infection, transfusion, deep venous thrombosis, and sepsis. PF was also associated with a longer hospital stay. Age, obesity, steroids, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class ≥ 3 predicted readmission. Obesity, steroids, bleeding disorder, preoperative transfusion, ASA class ≥3, and levels fused predicted reoperation. Age, African American race, decreased hematocrit, obesity, hypertension, dyspnea, steroids, bleeding disorder, ASA class ≥3, levels fused, and interbody levels fused predicted morbidity. Male gender and inclusion of anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) were protective of reoperation. Hispanic ethnicity, ALIF, and computer-assisted surgery (CAS) were protective of morbidity.

Conclusions:

Adjunctive PF was associated with a 1.5-times and 2.7-times increased odds of readmission and morbidity, respectively. ASA class and specific comorbidities predicted poorer outcomes, while ALIF and CAS were protective. These findings can guide surgical solutions given specific patient factors.

Keywords: Degenerative, fixation, fusion, lumbar spine, pelvic

INTRODUCTION

Adjunctive pelvic fixation (PF) has been utilized to provide greater sagittal and coronal correction and improve lumbar fusion construct stability and solid arthrodesis.[1,2] Given the growing elderly population and increasing utilization of PF in long constructs and deformity surgery, there is a need to evaluate the 30-day outcome profile of supplementary PF in degenerative lumbar fusion.[3,4] Thus, the purpose of this study was to compare multilevel adult degenerative lumbar fusion with and without PF based on 30-day readmission, reoperation, and morbidity and to explore predictors of primary outcomes.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study design and population

This study is a retrospective analysis of data from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database, from 2005 to 2018. This project is exempt from IRB review as this database is de-identified and no direct patient involvement occurred.

Patients ≥18 years old who underwent lumbar fusion were identified using current procedural terminology (CPT) codes for lumbar fusion and were stratified into groups with and without PF. Patients were excluded if they underwent single-level fusion; surgery for traumatic, deformity, nonelective, oncology, or revision purposes; had evidence of prior infection; or underwent additional procedures including osteotomy, arthroplasty, or cervical or thoracic procedures, including extension of fusion to the thoracic spine [Appendix A]. We evaluated patients with mid-length constructs (two-to-five segments) given that the topic of fusing to the pelvis in this group is controversial, with notably lacking literature. Further, by restricting analysis to mid-length constructs, we eliminated any potential morbidity associated with long constructs that could confound the association of fusion to the pelvis with morbidity.

Appendix A.

Inclusion and exclusion CPT codes

| CPT codes | |

|---|---|

| Stratified by | |

| Pelvic fixation | 22848 |

| Included | |

| Standalone PLIF/TLIF | Primary code: 22630; additional level code: 22632 |

| Posterolateral fusion | Primary code: 22612; additional level code: 22614 |

| PLIF/TLIF bundled with posterolateral fusion | Primary code: 22633; additional level code: 22634 |

| Standalone ALIF/LLIF | Primary code: 22558; additional level code: 22585 |

| Excluded | |

| Cervical fusion | 22600, 22590, 22551, 22552, 22554 |

| Thoracic fusion | 22610, 22556 |

| Non-elective | 10140, 11305, 20661, 22010, 22305, 22315, 22326, 22327 |

| Deformity | 22800, 22802, 22804, 22806, 22808, 22810, 22812, 22818 |

| Revision | 20680, 22830, 22849, 22850, 22852, 22855 |

| Osteotomy | 22210, 22212, 22214, 22216, 22220, 22222, 22224, 22226 |

| Intraspinal lesion | 63300, 63301, 63304, 63308 |

| Other procedures | 22858 |

Multilevel (≥2-level) fusion was identified by ≥1 entry of additional level code for a specific primary code, or ≥2 entries of separate primary codes with or without their respective additional level codes. Patients who did not meet this criteria were considered to have single level fusion and were excluded. Because thoracic fusion extending into the lumbar spine can be coded for using lumbar CPT codes, we also excluded patients who had >4 additional level codes. ALIF: Anterior lumbar interbody fusion. LLIF: Lateral lumbar interbody fusion. PLIF: Posterior lumbar interbody fusion. TLIF: Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion.

Outcomes and variables

Primary outcomes were 30-day readmission, reoperation, and morbidity. Readmission includes any inpatient stay to the same or another hospital related to the surgical procedure. The NSQIP database did not collect readmission data until 2011. Reoperation includes all major surgical procedures requiring return to the operating room for intervention of any kind. Morbidity includes infectious, pulmonary, cardiac, renal, neurological, hematologic, and thromboembolic complications reported in the ACS-NSQIP dataset.

Primary outcomes, as well as specific complications, were compared between groups with and without PF. Predictors of primary outcomes were analyzed among the entire cohort. Variables evaluated as potential predictors included patient demographic, comorbidity, laboratory values, and procedural factors [Table 1]. Procedural factors specifically included anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) and computer-assisted surgery (CAS), given prior associations of ALIF and CAS with improved 30-day outcomes and the use of circumferential fusion to promote arthrodesis in patients with particularly poor bone quality.[5,6] Variables with <80% of data available, such as operative time, were excluded from the analysis to avoid skewing of results.

Table 1.

Baseline differences in patient demographic, comorbidity, laboratory, and procedural factors and primary outcomes by presence or absence of pelvic fixation

| With pelvic fixation (n=818), n (%) | Without pelvic fixation (n=37,595), n (%) | P | Cases available (n=38,413) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Mean age (years)±SD | 63.6±12.4 | 61.1±13.1 | <0.001 | 38,413 |

| Obese | 401 (49.4) | 20,187 (54.0) | 0.009 | 38,213 |

| African American race | 49 (6.4) | 3034 (8.6) | 0.034 | 35,972 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 38 (4.8) | 2012 (5.7) | 0.320 | 36,229 |

| Male gender | 315 (38.5) | 17,457 (46.4) | <0.001 | 38,402 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Smoker | 107 (13.1) | 7388 (19.7) | <0.001 | 38,413 |

| Dyspnea | 58 (7.1) | 2293 (6.1) | 0.242 | 38,413 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 135 (16.5) | 6993 (18.6) | 0.127 | 38,413 |

| COPD | 52 (6.4) | 1695 (4.5) | 0.012 | 38,413 |

| Heart failure | 11 (1.3 ) | 138 (0.4) | <0.001# | 38,411 |

| Hypertension | 514 (62.8) | 22,031 (58.6) | 0.015 | 38,413 |

| Disseminated cancer | 38 (4.6) | 366 (1.0) | <0.001 | 38,413 |

| Open wound infection | 24 (2.9) | 171 (0.5) | <0.001# | 38,413 |

| Chronic steroid use | 59 (7.2) | 1591 (4.2) | <0.001 | 38,413 |

| Bleeding disorder | 12 (1.5) | 607 (1.6) | 0.740 | 38,413 |

| Preoperative transfusion | 16 (2.0) | 131 (0.3) | <0.001# | 38,413 |

| ASA class ≥3 | 548 (67.0) | 19,106 (50.9) | <0.001 | 38,367 |

| Lab values, mean±SD | ||||

| Creatinine | 0.93±0.76 | 0.92±0.43 | 0.591 | 34,381 |

| White cell count | 7.43±2.62 | 7.40±2.47 | 0.687 | 35,645 |

| Hematocrit | 38.6±5.6 | 40.8±4.4 | <0.001 | 36,103 |

| Platelet | 247±78 | 247±69 | 0.862 | 35,630 |

| Procedural factors | ||||

| Length of stay, mean±SD | 7.8±7.7 | 4.3±4.6 | <0.001 | 38,386 |

| Has ALIF | 159 (19.4) | 9770 (26.0) | <0.001 | 38,413 |

| Has CAS | 165 (20.2) | 2519 (6.7) | <0.001 | 38,413 |

| Mean levels fused, mean±SD | 2.6±1.0 | 2.4±0.8 | <0.001 | 38,413 |

| Mean interbody fusions, mean±SD | 0.8±1.1 | 1.2±1.1 | <0.001 | 38,413 |

| Unadjusted primary outcomes | ||||

| Readmission | 84 (12.4) | 2130 (6.8) | <0.001 | 32,022 |

| Reoperation | 60 (7.3) | 1355 (3.6) | <0.001 | 38,413 |

| Morbidity | 465 (56.8) | 8060 (21.4) | <0.001 | 38,413 |

Readmission data is relative to 677 patients with pelvic fixation and 31,324 without. #Fisher’s exact test. Bold values indicate significance (P<0.05). ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists, ALIF: Anterior lumbar interbody fusion, CAS: Computer-assisted surgery, COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, SD: Standard deviation

Statistical analysis

Analyses were completed in SPSS (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, United States). Demographic, comorbidity, laboratory, and procedural factors were individually analyzed for baseline differences between lumbar fusion with and without PF using Student's t-test for continuous and Chi-squared or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. The above factors were also individually analyzed for association with the primary outcomes using univariate logistic regression. Variables significant in the univariate analyses (P < 0.05) and PF were then evaluated for significance (P < 0.05) as independent predictors and control variables in a series of multivariate logistic regression analyses of primary outcomes.

RESULTS

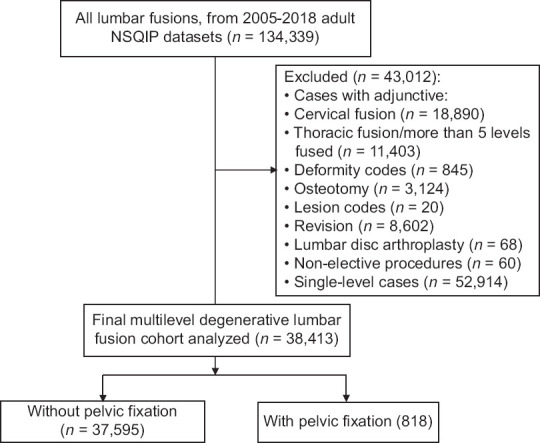

We included 38,413 multilevel degenerative lumbar fusion patients, 818 with PF [Figure 1]. Baseline group differences and unadjusted primary outcomes are provided in Table 1. Patients with PF were significantly more likely to be older (mean 64 vs. 61 years), female (61.5 vs. 53.6%), and have an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class ≥3 (67.0 vs. 50.9%) (P < 0.001) compared to patients without PF [Table 1]. Patients with PF were significantly less likely to be obese (49.4 vs. 54.0%), African American (6.4 vs. 8.6%), or smokers (13.1 vs. 19.7%).

Figure 1.

Flowchart demonstrating exclusion of patients. Adapted from the CONSORT 2010 Flow Diagram (original figure)

PF was associated with a significantly greater hospital stay (mean 7.8 vs. 4.6 days) and use of CAS (20.2 vs. 6.7%) and a significantly lower rate of inclusion of ALIF in the final construct (19.4 vs. 26.0%) (P < 0.001). Patients with PF also had greater total mean levels fused (2.6 vs. 2.4) but fewer mean interbody levels fused (0.8 vs. 1.2) (P < 0.001). The mean operative times with and without PF were 352 ± 144 min and 227 ± 105 min, respectively.

Primary outcomes

Unadjusted analysis revealed that PF was associated with greater readmission (12.4 vs. 6.8%), reoperation (7.3 vs. 3.6%), and morbidity (56.8 vs. 21.4%) (P < 0.001) [Table 1]. After adjusting for significant demographic characteristics, patient comorbidities, and procedural factors, including levels fused and number of interbody fusions, multivariate analysis [Tables 2–4] revealed that PF was still significantly associated with greater readmission (odds ratio [OR] = 1.546, confidence interval [CI]: 1.183–2.019, P < 0.001) and morbidity (OR = 2.740, CI: 2.307–3.254, P < 0.001), but not reoperation (OR = 1.298, CI: 0.935–1.802, P = 0.119).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of predictors of readmission

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Readmitted (n=2214) | Not readmitted (n=29,808) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Mean age (years)±SD | 64±13 | 61±13 | <0.001 | 1.016 (1.012, 1.021) | <0.001 |

| Obese | 1219 (58.8) | 15,887 (53.5) | <0.001 | 1.210 (1.093, 1.340) | <0.001 |

| African American race | 215 (10.3) | 2266 (8.1) | <0.001 | 1.209 (1.027, 1.423) | 0.022 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 123 (5.8) | 1547 (5.5) | 0.596 | ||

| Male gender | 993 (44.9) | 13,804 (46.3) | 0.183 | 1.048 (0.946, 1.162) | 0.368 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Smoker | 440 (19.9) | 5889 (19.8) | 0.894 | 1.157 (1.016, 1.318) | 0.028 |

| Dyspnea | 175 (7.9) | 1774 (6.0) | <0.001 | 1.034 (0.862, 1.240) | 0.720 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 548 (24.8) | 5337 (17.9) | <0.001 | 1.125 (1.000, 1.266) | 0.050 |

| COPD | 148 (6.7) | 1325 (4.4) | <0.001 | 1.169 (0.954, 1.433) | 0.132 |

| Heart failure | 16 (0.7) | 107 (0.4) | 0.008 | 1.337 (0.748, 2.393) | 0.327 |

| Hypertension | 1495 (67.5) | 17,248 (57.9) | <0.001 | 1.015 (0.906, 1.137) | 0.799 |

| Disseminated cancer | 68 (3.1) | 267 (0.9) | <0.001 | 2.494 (1.835, 3.390) | <0.001 |

| Open wound infection | 20 (0.9) | 153 (0.5) | 0.016 | 0.982 (0.583, 1.652) | 0.944 |

| Chronic steroid use | 179 (8.1) | 1,204 (4.0) | <0.001 | 1.631 (1.360, 1.956) | <0.001 |

| Bleeding disorder | 58 (2.6) | 465 (1.6) | <0.001 | 1.221 (0.904, 1.650) | 0.194 |

| Preoperative transfusion | 17 (0.8) | 107 (0.4) | 0.003 | 1.023 (0.580, 1.804) | 0.937 |

| ASA class ≥3 | 1429 (64.6) | 14,866 (49.9) | <0.001 | 1.297 (1.161, 1.449) | <0.001 |

| Lab values, mean±SD | |||||

| Creatinine | 1.0±0.5 | 0.9±0.4 | <0.001 | 1.089 (1.003, 1.182) | 0.043 |

| White cell count | 7.7±2.6 | 7.4±2.5 | <0.001 | 1.035 (1.018, 1.052) | <0.001 |

| Hematocrit | 39.7±5.0 | 40.8±4.4 | <0.001 | 0.965 (0.954, 0.976) | <0.001 |

| Platelet | 245±74 | 246±69 | 0.427 | ||

| Procedural factors | |||||

| Pelvic fixation | 84 (12.4a) | 592 (2.0) | <0.001 | 1.546 (1.183, 2.019) | 0.001 |

| Has ALIF | 546 (24.7) | 7740 (26.0) | 0.176 | ||

| Has ALIF (PF only) | 12 (14.3) | 115 (19.4) | 0.259 | ||

| Has CAS | 163 (7.4) | 2,067 (6.9) | 0.445 | ||

| Has CAS (PF only) | 19 (22.6) | 119 (20.1) | 0.592 | ||

| Mean levels fused | 2.5±0.9 | 2.4±0.9 | 0.199 | 0.999 (0.941, 1.061) | 0.980 |

| Mean interbody fusions | 1.1±1.2 | 1.2±1.1 | 0.449 | 1.046 (0.985, 1.110) | 0.140 |

| Length of stay | 5.2±4.8 | 4.3±4.9 | <0.001 | 1.007 (1.000, 1.014) | 0.059 |

aPercent of patients readmitted within pelvic fixation, #Fisher’s exact test. Bold values indicate significance (P<0.05). ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists, ALIF: Anterior lumbar interbody fusion, CAS: Computer-assisted surgery, COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, SD: Standard deviation, PF: Pelvic fixation

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of predictors of morbidity

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Morbidity (n=8525) | No morbidity (n=29,888) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Mean age (years)±SD | 64 (12) | 60 (13) | <0.001 | 1.011 (1.008-1.013) | <0.001 |

| Obese | 4634 (54.8) | 15,954 (53.6) | 0.055 | 1.065 (1.003-1.132) | 0.041 |

| African American race | 705 (8.8) | 2,378 (8.5) | 0.339 | 1.212 (1.092-1.346) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 399 (4.9) | 1,651 (5.9) | 0.001 | 0.761 (0.653-0.886) | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 3585 (42.1) | 14,187 (47.5) | <0.001 | 0.949 (0.890-1.012) | 0.114 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Smoker | 1393 (16.3) | 6102 (20.4) | <0.001 | 0.921 (0.849-0.998) | 0.046 |

| Dyspnea | 694 (8.1) | 1657 (5.5) | <0.001 | 1.201 (1.074-1.343) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1879 (22.0) | 5249 (17.6) | <0.001 | 1.048 (0.973-1.129) | 0.217 |

| COPD | 458 (5.4) | 1289 (4.3) | <0.001 | 1.076 (0.941-1.232) | 0.281 |

| Heart failure | 64 (0.8) | 85 (0.3) | <0.001 | 1.017 (0.662-1.565) | 0.937 |

| Hypertension | 5601 (65.7) | 16,944 (56.7) | <0.001 | 1.071 (1.001-1.146) | 0.046 |

| Disseminated cancer | 211 (2.5) | 193 (0.6) | <0.001 | 1.125 (0.864-1.464) | 0.382 |

| Open wound infection | 104 (1.2) | 91 (0.3) | <0.001 | 1.022 (0.693-1.511) | 0.909 |

| Chronic steroid use | 526 (6.2) | 1124 (3.8) | <0.001 | 1.238 (1.089-1.407) | 0.001 |

| Bleeding disorder | 240 (2.8) | 379 (1.3) | <0.001 | 1.516 (1.244-1.846) | <0.001 |

| Preoperative transfusion | 96 (1.1) | 51 (0.2) | <0.001 | 1.455 (0.969-2.185) | 0.070 |

| ASA class ≥3 | 5288 (62.1) | 14,366 (48.1) | <0.001 | 1.182 (1.108-1.261) | <0.001 |

| Lab values, mean±SD | |||||

| Creatinine | 1.0±0.5 | 0.9±0.4 | <0.001 | 1.029 (0.963-1.099) | 0.398 |

| White cell count | 7.4±2.6 | 7.4±2.4 | 0.823 | ||

| Hematocrit | 39.2±5.0 | 41.2±4.2 | <0.001 | 0.938 (0.931-0.944) | <0.001 |

| Platelet | 245±77 | 248±67 | 0.003 | 0.999 (0.999-1.000) | 0.001 |

| Procedural factors | |||||

| Pelvic fixation | 465 (56.8a) | 353 (43.2) | <0.001 | 2.740 (2.307-3.254) | <0.001 |

| Has ALIF | 1628 (19.1) | 8301 (27.8) | <0.001 | 0.644 (0.600-0.692) | <0.001 |

| Has ALIF (PF only) | 78 (16.8) | 81 (22.9) | 0.027 | 0.703 (0.461-1.071) | 0.101 |

| Has CAS | 589 (6.9) | 2095 (7.0) | 0.748 | 0.855 (0.759-0.962) | 0.010 |

| Has CAS (PF only) | 81 (17.4) | 84 (23.8) | 0.024 | 0.640 (.400-1.026) | 0.064 |

| Mean levels fused | 2.6±1.0 | 2.4±0.8 | <0.001 | 1.276 (1.232-1.321) | <0.001 |

| Mean interbody fusions | 1.1±1.2 | 1.2±1.1 | 0.020 | 1.042 (1.012-1.073) | 0.006 |

| Length of stay | 6.4±6.6 | 3.7±3.8 | <0.001 | 1.179 (1.167-1.190) | <0.001 |

aPercent of patients who experienced morbidity within pelvic fixation, #Fisher’s exact test. Bold values indicate significance (P<0.05). ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists, ALIF: Anterior lumbar interbody fusion, CAS: Computer-assisted surgery, COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, SD: Standard deviation, PF: Pelvic fixation

After adjusting for significant baseline characteristics in Table 1, multivariate analysis [Table 5] also revealed that PF independently predicted overall wound-related complications (OR = 1.533, CI: 1.087–2.160, P = 0.015), deep wound infection (OR = 2.915, CI: 1.827–4.651, P < 0.001), organ space infection (OR = 2.214, CI: 1.199–4.087, P = 0.011), overall pulmonary complications (OR = 1.490, CI: 1.018–2.181, P = 0.040), prolonged mechanical ventilation (OR = 3.840, CI: 2.031–7.261, P < 0.001), urinary tract infection (UTI) (OR = 1.811, CI: 1.243–2.637, P = 0.002), bleeding events requiring transfusion (OR = 3.299, CI: 2.797–3.891, P < 0.001), deep venous thrombosis (DVT)/thrombophlebitis (OR = 2.054, CI: 1.295–3.258, P = 0.002), and sepsis/septic shock (OR = 1.713, CI: 1.032–2.845, P = 0.038).

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of specific complications by presence or absence of pelvic fixation

| Specific complications | With pelvic fixation, n (%) | Without pelvic fixation, n (%) | Univariate P | OR (95% CI) | Multivariate P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wound-related complication | 52 (6.4) | 955 (2.5) | <0.001 | 1.533 (1.087-2.160) | 0.015 |

| Superficial site infections | 10 (1.2) | 432 (1.1) | 0.846 | ||

| Deep wound infections | 26 (3.2) | 279 (0.7) | <0.001 | 2.915 (1.827-4.651) | <0.001 |

| Organ space infections | 15 (1.8) | 185 (0.5) | <0.001# | 2.214 (1.199-4.087) | 0.011 |

| Dehiscence | 4 (0.5) | 149 (0.4) | 0.571# | ||

| Pulmonary complication | 40 (4.9) | 769 (2.0) | <0.001 | 1.490 (1.018-2.181) | 0.040 |

| Pneumonia | 9 (1.1) | 345 (0.9) | 0.589 | ||

| Re-intubation | 11 (1.3) | 179 (0.5) | 0.003# | 1.577 (0.748-3.325) | 0.231 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 14 (1.7) | 288 (0.8) | 0.002 | 1.712 (0.957-3.062) | 0.070 |

| Prolonged ventilation | 16 (2.0) | 137 (0.4) | <0.001 | 3.840 (2.031-7.261) | <0.001 |

| Renal complication | 6 (0.7) | 142 (0.4) | 0.138 | ||

| Renal insufficiency | 0 | 84 (0.2) | 0.429 | ||

| Acute renal failure | 6 (0.7) | 59 (0.2) | 0.003# | 1.418 (0.400-5.029) | 0.589 |

| Urinary tract infection | 37 (4.5) | 718 (1.9) | <0.001 | 1.811 (1.243-2.637) | 0.002 |

| Stroke/CVA | 3 (0.4) | 78 (0.2) | 0.248 | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 2 (0.2) | 140 (0.4) | 0.773 | ||

| Cardiac arrest requiring CPR | 4 (0.5) | 83 (0.2) | 0.115# | ||

| Bleeding transfusions | 402 (49.1) | 6,132 (16.3) | <0.001 | 3.299 (2.797-3.891) | <0.001 |

| DVT/thrombophlebitis | 23 (2.8) | 394 (1.0) | <0.001 | 2.054 (1.295-3.258) | 0.002 |

| Sepsis/septic shock | 25 (3.1) | 423 (1.1) | <0.001 | 1.713 (1.032-2.845) | 0.038 |

#Fisher’s exact test. Bold values indicate significance (P<0.05). CPR: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, DVT: Deep venous thrombosis, CVA: Cerebrovascular accident, OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval

Predictor analysis

There were 2214 readmissions (6.9%) in 32,022 patients. On multivariate analysis, increased age (P < 0.001), obesity (P < 0.001), African American race (P = 0.022), smoking (P = 0.028), disseminated cancer (P < 0.001), chronic steroid use (P < 0.001), ASA class ≥ 3 (P < 0.001), and other laboratory parameters independently predicted readmission [Table 2].

There were 1415 reoperations (3.7%) in 38,413 patients. On multivariate analysis, obesity (P = 0.021), female gender (P = 0.027), disseminated cancer (P = 0.004), chronic steroid use (P = 0.024), bleeding disorder (P = 0.028), preoperative transfusion (P = 0.037), ASA class ≥ 3 (P < 0.001), increased white cell count (P = 0.001), increased length of stay (P < 0.001), and levels fused (P = 0.003) predicted reoperation [Table 3]. Inclusion of ALIF in the final construct was protective against reoperation (P < 0.001). Among PF patients only, CAS was protective against reoperation in univariate analysis (P = 0.049), but not in multivariate analysis.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of predictors of reoperation

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Reoperation (n=1415) | No reoperation (n=36,998) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Mean age (years)±SD | 62±13 | 61±13 | 0.001 | 1.000 (0.994-1.006) | 0.988 |

| Obese | 823 (58.9) | 19,765 (53.7) | <0.001 | 1.164 (1.023-1.326) | 0.021 |

| African American race | 137 (10.4) | 2946 (8.5) | 0.016 | 1.185 (0.970-1.447) | 0.097 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 87 (6.5) | 1963 (5.6) | 0.160 | ||

| Male gender | 601 (42.5) | 17,171 (46.4) | 0.004 | 0.861 (0.755-0.983) | 0.027 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Smoker | 261 (18.4) | 7234 (19.6) | 0.302 | 0.888 (0.750-1.051) | 0.168 |

| Dyspnea | 122 (8.6) | 2229 (6.0) | <0.001 | 1.191 (0.953-1.489) | 0.124 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 340 (24.0) | 6788 (18.3) | <0.001 | 1.090 (0.937-1.268) | 0.262 |

| COPD | 88 (6.2) | 1659 (4.5) | 0.002 | 1.094 (0.841-1.423) | 0.502 |

| Heart failure | 7 (0.5) | 142 (0.4) | 0.510 | 1.695 (0.670-4.292) | 0.265 |

| Hypertension | 880 (62.2) | 21,665 (58.6) | 0.006 | 1.105 (0.959-1.274) | 0.169 |

| Disseminated cancer | 24 (1.7) | 380 (1.0) | 0.015 | 2.309 (1.316-4.065) | 0.004 |

| Open wound infection | 19 (1.3) | 176 (0.5) | <0.001 | 1.065 (0.573-1.980) | 0.842 |

| Chronic steroid use | 91 (6.4) | 1559 (4.2) | <0.001 | 1.324 (1.038-1.690) | 0.024 |

| Bleeding disorder | 41 (2.9) | 578 (1.6) | <0.001 | 1.495 (1.044-2.140) | 0.028 |

| Preoperative transfusion | 18 (1.3) | 129 (0.3) | <0.001 | 1.829 (1.037-3.226) | 0.037 |

| ASA class ≥3 | 896 (63.4) | 18,758 (50.8) | <0.001 | 1.338 (1.162-1.540) | <0.001 |

| Lab values, mean±SD | |||||

| Creatinine | 1.0±0.6 | 0.9±0.4 | 0.002 | 1.021 (0.916-1.138) | 0.708 |

| White cell count | 7.7±3.0 | 7.4±2.5 | <0.001 | 1.033 (1.013-1.054) | 0.001 |

| Hematocrit | 40.0±4.7 | 40.8±4.4 | <0.001 | 0.994 (0.980-1.008) | 0.411 |

| Platelet | 249±76 | 247±70 | 0.388 | ||

| Procedural factors | |||||

| Pelvic fixation | 60 (7.3a) | 758 (2.0) | <0.001 | 1.298 (0.935-1.802) | 0.119 |

| Has ALIF | 301 (21.3) | 9,628 (26.0) | <0.001 | 0.759 (0.653-0.882) | <0.001 |

| Has ALIF (PF only) | 7 (11.7) | 152 (20.1) | 0.114 | 0.549 (0.219-1.378) | 0.202 |

| Has CAS | 109 (7.7) | 2575 (7.0) | 0.282 | 1.012 (0.796-1.286) | 0.924 |

| Has CAS (PF only) | 18 (30.0) | 147 (19.4) | 0.049 | 1.362 (0.598-3.102) | 0.462 |

| Mean levels fused | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.4 (0.8) | <0.001 | 1.108 (1.035-1.186) | 0.003 |

| Mean interbody fusions | 1.1 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.1) | 0.158 | 0.982 (0.923-1.044) | 0.557 |

| Length of stay | 8.0 (8.0) | 4.2 (4.5) | <0.001 | 1.085 (1.074-1.096) | <0.001 |

aPercent of patients who required reoperation within pelvic fixation, #Fisher’s exact test. Bold values indicate significance (P<0.05). ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists, ALIF: Anterior lumbar interbody fusion, CAS: Computer-assisted surgery, COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, SD: Standard deviation, PF: Pelvic fixation

Morbidity occurred in 8,525 patients (22.2%). On multivariate analysis, increased age (P < 0.001), obesity (P = 0.041), African American race (P < 0.001), baseline dyspnea (P = 0.001), hypertension (P = 0.046), chronic steroid use (P = 0.001), bleeding disorder (P < 0.001), ASA class ≥ 3 (P < 0.001), and decreased preoperative hematocrit (P < 0.001) and platelet count (P = 0.001) predicted morbidity [Table 4]. Levels fused (P < 0.001) and interbody levels fused (P = 0.006) also predicted morbidity. Hispanic ethnicity (P < 0.001), smoking (P = 0.046), inclusion of ALIF in the final construct (P < 0.001), and CAS (P = 0.010) were protective against morbidity.

DISCUSSION

Comparison of surgical solution

Literature comparing multilevel lumbar fusion with and without PF for adult degenerative disease is limited, with current studies restricted by small sample size, poor generalizability, and few patients with degenerative disease. In the present study, early outcomes were significantly worse with adjunctive PF. After adjusting for significant surrogates for poorer health status, which were worse at baseline in the PF group, including specific medical comorbidities and ASA class ≥3, PF was still associated with a 55% increase in odds of readmission and 174% increase in odds of morbidity.

In a combined degenerative and deformity study, Kasten et al. demonstrated an overall 54% complication rate with PF, which is in line with the 57% rate observed in the present study.[2] In comparison, the rate of morbidity in deformity surgery in general is about 31%,[7] while in the present study, the rate of morbidity for multilevel lumbar fusion without PF was 21%. These findings suggest that PF provides a significantly greater element of morbidity to multilevel lumbar fusion.[7,8] Thus, PF should be utilized conservatively when treating degenerative lumbar pathology.

Moreover, the rate of readmission in deformity surgery is 6% and, with PF, is 7%.[4,7] For patients undergoing multilevel fusion for degenerative purposes without PF in the present study, the readmission rate was 7%. In light of the 12% readmission rate, we found with PF, these findings suggest that degenerative patients, who are inherently older on average, are less able to tolerate more invasive and morbid procedures, such as fixation to the pelvis, resulting in greater readmission and ultimately greater health-care costs.[9,10] This is particularly significant given the difference in length of stay we observed for patients with (8 days) and without PF (4 days).

Reoperation rates no longer statistically differed between the surgical techniques after multivariate analysis. Interestingly, in deformity surgery, PF has been associated with increased short-term reoperation, as well as readmission and morbidity.[1] PF has even been associated with high rates of 6-month postoperative mechanical failure in deformity surgery, ranging from 15% to 36%.[2,11] In the present degenerative study, the early reoperation rate with PF was 7.3%, considerably below that seen in deformity surgery. Therefore, the lack of a finding of a significant difference in early reoperation suggests that the mechanical stresses placed on the construct when treating degenerative lumbar pathology are not severe enough to promote early device failure. On the contrary, it also suggests that PF does not offer an appreciable benefit to early construct integrity.

Specific complications

PF has been associated with severe sexual dysfunction, rates of which exceed 40%.[3] PF has even been posited as a risk factor for posterior hip dislocation after total hip arthroplasty; however, this has not been demonstrated beyond a single case report.[12] While the NSQIP database does not evaluate for the above complications, we did identify 3.3-times increased odds of transfusion, 1.5-times increased odds of a wound-related complication, and 2.1-times increased odds of DVT/thrombophlebitis.

The increased risk of blood loss with PF has been documented in deformity surgery.[4,7,8,13,14] Kothari et al. demonstrated a 74% transfusion rate for patients undergoing PF.[4] We observed a transfusion rate of 49%, likely lower than the 74% figure as that included larger constructs extending into the thoracic spine. However, this is notably higher than the 16% transfusion rate for patients without PF in the present study. In comparison, transfusion rates for up to two-level posterior and anterior interbody fusion are 12% and 10%, respectively.[15]

The associations between PF and wound-related complication and DVT are not surprising given the greater invasiveness and more extensive surgical dissection, operative time (352 vs. 227 min) and resultant release of inflammatory factors, and potential prominence of hardware.[4,16] We specifically observed a greater rate of deep wound and organ space infections with PF, which may be directly related to the effects of transfusion on immune system modulation as well as increased operative time.[4,17,18] Interestingly, Kothari et al. did not identify PF as a risk factor for wound-related complications or DVT.

In addition, we observed 1.5-times greater odds of pulmonary complication with PF. In deformity surgery, pulmonary complications have been shown to be significantly greater in long-segment fusions, which are more likely to have fixation to the pelvis, than short-segment fusions.[19] Further, Urban et al. demonstrated greater rates of pneumonia with PF.[1] Thus, the greater rates of pulmonary injury observed could be related to acute inflammatory events incited by embolization of sacral and iliac fat and marrow debris from the greater level of morbidity that PF adds to multilevel lumbar fusion.[20]

Predictor variables

No studies have reported on risk factors associated with poor early outcomes in patients with degenerative disease undergoing PF. In the deformity literature, age, elevated ASA class, and bleeding disorder have been associated with poor outcomes and postoperative complications.[7,8,11,14,18] In other spine research literature, diabetes and hypertension were significant risk factors for readmission.[21] While we did not identify diabetes as a risk factor for poor early outcomes, we did find that increased age, obesity, and ASA class ≥3 predicted poor 30-day outcomes. We also identified hypertension as a risk factor for morbidity. Thus, these findings suggest that preoperative patient factors should be strongly considered in patient selection and surgical planning, particularly when performing more morbid adjunct procedures such as PF.

Further, we observed that African American race predicted readmission and morbidity. African American race has previously been shown to predict poorer outcomes in spine surgery, with researchers noting an interplay between differences in postoperative care, socioeconomic factors, and greater baseline comorbidities playing a role.[22,23] Interestingly, we found that Hispanic ethnicity was protective against morbidity. These findings suggest that there are factors beyond the NSQIP dataset, such as variables related to geographic location, socioeconomic and insurance status, and hospital type, that would aid in understanding the relationship between race, ethnicity, and outcomes in spine surgery.

Procedural factors

The inclusion of ALIF in the final construct predicted reduced reoperation and morbidity. The utilization of CAS also predicted reduced morbidity. Given the significantly higher rate of bleeding events requiring transfusion observed with PF, the reduced early morbidity seen with ALIF is most likely related to a lower rate of blood loss and subsequently fewer transfusions and other associated complications.[15] This is because the anatomic dissection in ALIF is through an avascular plane. Minimizing blood loss and surgical dissection have also been postulated as mechanisms for reduced morbidity seen with CAS.[5] This also raises the point of different operational approaches as being more or less beneficial for blood loss. While only 4.8% of patients with ALIF had CAS, the use of CAS with ALIF may have also bolstered the strong protective effect seen with ALIF. However, a more in-depth analysis would be beyond the scope of this study.

In addition, supplementary ALIF provides a restorative effect on reducing biomechanical strain at the lumbosacral junction when used in PF. O’Brien et al. noted that supplementary ALIF particularly augments fusion construct strength at the sacropelvic region from L4 to the S1 vertebral body and cephalad aspects of the sacral ala, thereby delivering a significant biomechanical advantage to counter lumbosacral junctional bending moments and dorsal pullout forces seen with PF.[6] Therefore, it is possible that this protective effect of ALIF against screw pullout and instrumentation failure contributed to the reduction in reoperations.

While operative time has been shown to be a highly influential factor in determining outcomes,[14] the data were only available for <80% of patients and therefore were not included in univariate or multivariate analyses. In addition, meaningful interpretation of operative time in the present study would be limited by the variability of procedures included in the present study that cannot be accounted for by the NSQIP dataset (i.e., surgical approaches, fixation to the pelvis, patient positioning, and so forth).

Limitations

While the NSQIP database provides for surrogates of bone quality, such as smoking status and chronic steroid use, the database does not provide history of osteoporosis. The database also does not provide patient-reported outcomes or radiographic parameters. Having these variables would provide additional points of discussion but ultimately would not impact our conclusions. In the context of PF, the NSQIP dataset cannot distinguish between S2-alar-iliac screw and traditional iliac screw fixation, which may have different outcome profiles. Finally, the database lacks adequate and complete ICD codes to verify whether each patient truly had degenerative lumbar disease. However, our carefully planned series of CPT-based exclusions, restriction of analysis to the lumbar spine, and overall results helped to minimize inclusion of patients with solely deformity pathology or those with infectious or spine-oncologic diagnoses.

CONCLUSION

In this national database study of 38,413 patients who underwent multilevel lumbar fusion for degenerative disease, we found that supplementary PF was associated with a 1.5-times increase in odds 30-day readmission and a 2.7-times increase in odds of morbidity compared to lumbar fusion without PF, with significantly greater rates of transfusion, DVT/thrombophlebitis, sepsis, UTI, prolonged mechanical ventilation, and wound-related complications. These findings held true despite controlling for patient- and procedural-related factors, including surrogates for increased invasiveness such as total number of levels fused and number of interbody fusions. After controlling for patient-related factors, there were no technique-based differences in 30-day reoperation. Increased age, ASA class ≥3, obesity, and other demographic factors and medical comorbidities predicted poorer 30-day outcomes, while anterior column support was protective against reoperation and morbidity, and CAS was protective against morbidity.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Malik AT, Kim J, Yu E, Khan SN. Fixation to pelvis in pediatric spine deformity – An analysis of 30-day outcomes. World Neurosurg. 2019;121:e344–50. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasten MD, Rao LA, Priest B. Long-term results of iliac wing fixation below extensive fusions in ambulatory adult patients with spinal disorders. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2010;23:e37–42. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3181cc8e7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamilton DK, Smith JS, Nguyen T, Arlet V, Kasliwal MK, Shaffrey CI. Sexual function in older adults following thoracolumbar to pelvic instrumentation for spinal deformity. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19:95–100. doi: 10.3171/2013.4.SPINE121078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kothari P, Somani S, Lee NJ, Guzman JZ, Leven DM, Skovrlj B, et al. Thirty-day morbidity associated with pelvic fixation in adult patients undergoing fusion for spinal deformity: A propensity-matched analysis. Global Spine J. 2017;7:39–46. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1583946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nooh A, Aoude A, Fortin M, Aldebeyan S, Abduljabbar FH, Eng PJ, et al. Use of computer assistance in lumbar fusion surgery: Analysis of 15 222 patients in the ACS-NSQIP database. Global Spine J. 2017;7:617–23. doi: 10.1177/2192568217699193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Brien M, Kuklo T, Lenke L. Sacropelvic instrumentation: Anatomic and biomechanical zones of fixation. Semin Spine Surg. 2004;16:76–90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee NJ, Kothari P, Kim JS, Shin JI, Phan K, Di Capua J, et al. Early complications and outcomes in adult spinal deformity surgery: An NSQIP study based on 5803 patients. Global Spine J. 2017;7:432–40. doi: 10.1177/2192568217699384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee NJ, Shin JI, Kothari P, Kim JS, Leven DM, Steinberger J, et al. Incidence, impact, and risk factors for 30-day wound complications following elective adult spinal deformity surgery. Global Spine J. 2017;7:417–24. doi: 10.1177/2192568217699378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubel NC, Chung AS, Wong M, Lara NJ, Makovicka JL, Arvind V, et al. 90-day readmission in elective primary lumbar spine surgery in the inpatient setting: A nationwide readmissions database sample analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2019;44:E857–64. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeramaneni S, Gum JL, Carreon LY, Klineberg EO, Smith JS, Jain A, et al. Impact of readmissions in episodic care of adult spinal deformity: Event-based cost analysis of 695 consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:487–95. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.01589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guler UO, Cetin E, Yaman O, Pellise F, Casademut AV, Sabat MD, et al. Sacropelvic fixation in adult spinal deformity (ASD); a very high rate of mechanical failure. Eur Spine J. 2015;24:1085–91. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3615-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furuhashi H, Togawa D, Koyama H, Hoshino H, Yasuda T, Matsuyama Y. Repeated posterior dislocation of total hip arthroplasty after spinal corrective long fusion with pelvic fixation. Eur Spine J. 2017;26:100–6. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4880-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White SJW, Cheung ZB, Ye I, Phan K, Xu J, Dowdell J, et al. Risk factors for perioperative blood transfusions in adult spinal deformity surgery. World Neurosurg. 2018;115:e731–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samuel AM, Fu MC, Anandasivam NS, Webb ML, Lukasiewicz AM, Kim HJ, et al. After posterior fusions for adult spinal deformity, operative time is more predictive of perioperative morbidity, rather than surgical invasiveness: A need for speed? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017;42:1880–7. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz AD, Mancini N, Karukonda T, Greenwood M, Cote M, Moss IL. Approach-based comparative and predictor analysis of 30-day readmission, reoperation, and morbidity in patients undergoing lumbar interbody fusion using the ACS-NSQIP dataset. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2019;44:432–41. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De la Garza-Ramos R, Abt NB, Kerezoudis P, McCutcheon BA, Bydon A, Gokaslan Z, et al. Deep-wound and organ-space infection after surgery for degenerative spine disease: An analysis from 2006 to 2012. Neurol Res. 2016;38:117–23. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2016.1138669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwarzkopf R, Chung C, Park JJ, Walsh M, Spivak JM, Steiger D. Effects of perioperative blood product use on surgical site infection following thoracic and lumbar spinal surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:340–6. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b86eda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang H, Zhu J, Ji F, Wang S, Xie Y, Fei H. Risk factors for postoperative complication after spinal fusion and instrumentation in degenerative lumbar scoliosis patients. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phan K, Xu J, Maharaj MM, Li J, Kim JS, Di Capua J, et al. Outcomes of short fusion versus long fusion for adult degenerative scoliosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop Surg. 2017;9:342–9. doi: 10.1111/os.12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urban MK, Jules-Elysee KM, Beckman JB, Sivjee K, King T, Kelsey W, et al. Pulmonary injury in patients undergoing complex spine surgery. Spine J. 2005;5:269–76. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lovecchio F, Hsu WK, Smith TR, Cybulski G, Kim B, Kim JY. Predictors of thirty-day readmission after anterior cervical fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39:127–33. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elsamadicy AA, Adogwa O, Sergesketter A, Hobbs C, Behrens S, Mehta AI, et al. Impact of race on 30-day complication rates after elective complex spinal fusion (≥5 Levels): A single institutional study of 446 patients. World Neurosurg. 2017;99:418–23. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanford Z, Taylor H, Fiorentino A, Broda A, Zaidi A, Turcotte J, et al. Racial disparities in surgical outcomes after spine surgery: An ACS-NSQIP analysis. Global Spine J. 2019;9:583–90. doi: 10.1177/2192568218811633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]