Abstract

Aim:

The aim of the study is to evaluate and compare the clinical and radiographic outcome of partial pulpotomy and full pulpotomy in mature permanent molars with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis using biodentine.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 66 vital mature permanent molars with irreversible pulpitis were randomly allocated to a partial pulpotomy (n = 33) and full pulpotomy group (n = 33). Biodentine was used as a pulp capping material which was covered with resin-modified glass ionomer cement (RMGIC) followed by composite restoration. Clinical and radiographic evaluation was done at 3, 6, and 12 months follow-up for tenderness, periapical radiolucency, dentine bridge formation, and root canal calcification. Data from the study were analyzed using a Friedman and Mann–Whitney test and the success rate was analyzed by Chi-square value.

Result:

No statistically significant difference was found between partial and full pulpotomy (P > 0.05) and the success rate was 80.7% and 92.8%, respectively, at 12 months follow-up period.

Conclusion:

Both partial and full pulpotomy can be used as a permanent treatment modality in symptomatic irreversible pulpitis of vital mature permanent molars.

Keywords: Apical periodontitis, biodentine, irreversible pulpitis, pulpotomy

INTRODUCTION

Irreversible pulpitis is a common dental condition, diagnosed clinically by spontaneous and lingering pain which lasts for minutes to hours after removal of external stimulation.[1] Root canal treatment (RCT) is the routine choice of treatment for teeth with irreversible pulpitis, which consists of total removal of the pulp tissue. RCT has the drawback of being a nonbiologic and nonconservative procedure as well as it is costly, time-consuming, and necessitates meticulous skills. According to a systematic study, RCT success rates have not increased over the last few decades, and molars have the worst survival rates of all teeth.[2] Some epidemiological studies demonstrated a high occurrence of technically inadequate root fillings, and associated apical periodontitis was seen despite new advances in root canal preparation and filling.[3,4] Hence, an economic, conservative, and simple technique would be desirable.

At present, endodontology is more shifted toward biologic treatment modalities that would postpone or avoid such nonbiologic treatment. Vital pulp therapy (VPT) is considered a minimally invasive technique (“Endolight”) for the treatment of teeth with irreversible pulpitis.[5,6,7,8] Pulpotomy can preserve the tooth structure, retain the remaining pulp tissue's proprioceptive defense mechanism, and reduce the risk of tooth fracture. In addition, it is less painful, more convenient as well as it simplifies the treatment protocols, and avoids treatment complications. Many studies reported a histologically healthy sign in a patient with signs of irreversible pulpitis. The inflammation is limited to a small area of the pulp within the exposure site, and healthy tissue persists in the coronal pulp, and the root, away from caries.[9] Conventionally, it was thought that the clinical signs and symptoms of pulpitis and the histological state of the pulp in mature teeth had little correlation; however, a recent histological study found that the clinical symptoms of pulpitis and the corresponding histological state of a diseased pulp have a strong (84%) correlation.[9]

According to some recent systematic studies, a pulpotomy is a promising treatment choice for mature permanent teeth with irreversible pulpitis.[10,11,12] A partial pulpotomy entails the removal of 2–3 mm of pulp tissue from the inflamed coronal pulp underneath the exposure while leaving the underlying essential pulp intact, making the procedure more biological. The entire coronal portion of the vital pulp is removed to the level of canal orifices in a full pulpotomy, while the remaining radicular region remains healthy. Biodentine is a calcium silicate cement that has good handling, faster initial setting, nonstaining with better marginal integrity, antimicrobial property, and bioactivity.[13] It promotes mineralization and dentine regeneration by triggering odontoblast differentiation from pulp progenitor cells.[14]

This study aimed to compare and assess the outcome of partial and full pulpotomy in symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with biodentine in mature permanent molars. The null hypothesis of this study was pulpotomy is a successful treatment modality in irreversible pulpitis of mature molars, and there is no difference between partial and full pulpotomy in these patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This double-blinded randomized clinical trial was conducted in the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics after approval from the ethical committee of the institute (Dean/2019/EC/1716) and registration in CTRI/2021/07/034842. A pilot study was assisted before beginning the main study. The pilot study results were substituted in software G*Power 3.1.9.7 (Heinrich-Heine-Universitat, Dusseldorf, Germany) giving a total sample size of 66 with 92.57% power.

A total of 66 carious exposed mature permanent molars with clinical symptoms of irreversible pulpitis were selected. The patient's ages were varied from 18 to 40 years. Mature permanent molars with carious exposed associated with or without spontaneous sharp or dull pain, lingering by cold and heat stimuli showed a clinical diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis with/without periapical involvement and responded positively to pulp vitality test were included for this study. Selected teeth were restorable, probing pocket depth and mobility were within normal limits.

Teeth with immature roots, presence of sinus tract or swelling, insufficient bleeding after pulp exposure, and profuse persistence pulpal hemorrhage were excluded from the study. The treatment protocol was explained to the patient in detail and written consent was taken in their handwritten form. Vitality test was performed with endo cold spray (Orikam Healthcare India) and electric pulp tester (Coxo vitality pulp tester C-pulse, Vico dental). After case selection, preoperative intraoral periapical radiographs were taken for all selected teeth. Preoperative cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) took for those patients, who had irreversible pulpitis with symptomatic apical periodontitis.

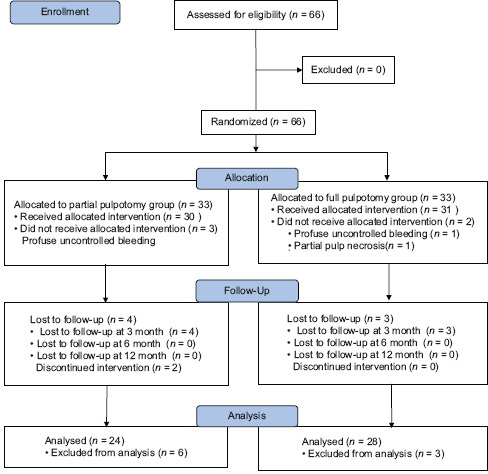

The enrolled patients were randomly allocated into 2 Groups (n = 33: In each group) depending upon the amount of pulp removal [Chart 1].

Chart 1.

Consort flow diagram of the 66 eligible patients up to 12-month follow-up

Group I: Partial pulpotomy

Group II: Full pulpotomy.

All the selected teeth were anesthetized using 2% lidocaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine (Neon, Lox 2%) and isolated with a rubber dam (GDC, India). Teeth were cleaned and disinfected with a cotton swab moistened with 3% sodium hypochlorite solution. Carious dentin removal was performed with #2 round diamond point (API, India), and the remaining soft dentine was manually removed with a sterile spoon excavator (GDC, India).

In Group I, after complete carious excavation, pulp tissue was removed from the exposure site to a depth of 2–3 mm with a high-speed hand-piece, using a sterile #2 round carbide bur (Mani, Japan). The pulp wound was flushed gently with saline, and the bleeding was controlled with a cotton pellet saturated with 3% sodium hypochlorite solution (Septodont, USA). All teeth exhibited adequate pulpal hemostasis within 10 min of sodium hypochlorite dressing, except 3 that had profuse uncontrolled bleeding from the pulp and they were excluded from the study sample.

In Group II, using fresh sterile round diamond point, the pulp chamber was deroofed in which one tooth was partially necrosed after deroofing, so excluded from the study. The opening was refined with a sterile tapered diamond bur. The pulp tissue was removed with a high-speed #2 round carbide bur (Mani, Japan) to the level of canal orifices and the remaining coronal pulp was curated with a spoon excavator. The bleeding was controlled by using a cotton pellet saturated with 3% sodium hypochlorite solution (Septodont, USA). All teeth exhibited adequate pulpal hemostasis within 10 min, except one and that was excluded from the study sample.

After pulp removal, freshly mixed biodentine (Septodont, Saint-Maurdes-Fossess, France) was placed over the exposed pulp in both the groups with a thickness of 2–3 mm, following which it was allowed to set for 15 min. Biodentine was sealed with resin-modified glass ionomer cement (RMGIC)] (GC Corporation) and light-cured (Ivoclar Vivadent) for 20 s followed by a temporary restoration (Cavitemp Ammdent, India). After 1 week, teeth were permanently restored with composite resin (Ivoclar Vivadent). The clinical and radiographic evaluation was done at 3, 6, and 12 months after the procedure and compared with baseline records. Twelve-month postoperative CBCT has been taken for those patients, who had preoperative irreversible pulpitis with symptomatic apical periodontitis.

The clinical and radiographic evaluation was done by an independent observer who was blinded from the groups. Treatment success was considered by cases in which the tooth exhibited an absence of clinical signs and symptoms of pulpal disease such as pain, tenderness to percussion, sinus tract and swelling, no evidence of root resorption, new furcal, and periapical pathosis on the recall radiograph. History of spontaneous or lingering pain after a few days of the procedure, tenderness on percussion, well-defined apical or furcal radiolucency on the periapical radiograph, no improvement or increased personal activity intelligence (PAI) score on CBCT, and signs of internal root resorption indicate treatment failure. Root-canal calcifications were not considered as failures.

After evaluation, all the data were entered in Microsoft Excel and transferred to SPSS Software (Version 21.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) for statistical analysis. Mann–Whitney test was used to analyze the data in between the groups, and the Friedman test was used for intragroup analysis to evaluate percussion sensitivity, dentine bridge formation, and root canal calcification at different follow-up periods. Furthermore, Chi-squared test was applied to evaluate the success rate between the groups.

RESULTS

The intervention was done in a total of 61 sample teeth, of these, 13 cases were associated with apical periodontitis. A total of 52 patients were examined at the end of 12 months.

Group I – Four patients dropped out due to unknown reasons and immediate failure occurred in two patients within 2 weeks, those required RCT because of severe persistent pain. Mild pain and tenderness continuously persist in one patient and two new patients developed tenderness to percussion at the end of study so, a total of five cases were considered as failures. Percussion sensitivity, dentinal bridge formation, and root canal calcification were present in 12.5%, 37.5%, 12.5% cases at the end of 12 months, respectively. The intragroup result was statistically significant (P < 0.05) regarding dentine bridge formation and nonsignificant regarding percussion sensitivity, and root canal calcification at the end of the study [Table 1a-c].

Table 1a.

Comparative evaluation of percussion sensitivity between both groups at different follow-up time

| Groups | Baseline | Follow-up (months) | Within-group comparison (Friedman test) (P) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| 3 | 6 | 12 | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | ||

| I (n=30) | 5 (16.6) | 25 (83.3) | 1 (4.1) | 23 (95.8) | 2 (8.3) | 22 (91.6) | 3 (12.5) | 21 (87.5) | 0.137 |

| II (n=31) | 8 (25.8) | 23 (74.1) | 0 | 28 (100) | 0 | 28 (100) | 2 (7.14) | 26 (92.8) | 0.001 |

| Between the groups comparison (Mann–Whitney test) (Z, P) | −0.636, 0.526 | −1.080, 0.280 | −1.543, 0.123 | −0.647, 0.518 | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| 1b: Comparative evaluation of dentin bridge formation between two groups at different follow-up times | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Groups | Follow-up (months) | Within-group comparison (Friedman test) (P) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 3 | 6 | 12 | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| P | A | P | A | P | A | ||||

| I (n=24) | 1 (4.1) | 23 (95.8) | 7 (29.1) | 17 (70) | 9 (37.5) | 15 (62.5) | 0.002 | ||

| II (n=28) | 0 | 28 (100) | 3 (10.7) | 25 (89.2) | 4 (14.2) | 24 (85.7) | 0.039 | ||

| Between the groups comparison (Mann–Whitney test) (Z, P) | −1.080, 0.280 | −1.667, 0.096 | −1.837, 0.066 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 1c: Comparative evaluation of root-canal calcification between two groups at different follow-up times | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Groups | Follow-up (months) | Within-group comparison (Friedman test) (P) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 3 | 6 | 12 | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| P | A | P | A | P | A | ||||

| I (n=24) | 0 | 24 (100) | 1 (4.1) | 23 (95.8) | 3 (12.5) | 21 (87.5) | 0.097 | ||

| II (n=28) | 0 | 28 (100) | 3 (10.7) | 25 (89.2) | 7 (25) | 21 (75) | 0.005 | ||

| Between the groups comparison (Mann–Whitney test), (Z, P) | 0.000, 1.000 | −0.875, 0.382 | −1.129, 0.259 | ||||||

Group II – Three patients dropped out due to unknown reasons. Two patients developed tenderness to percussion at the end of the study and they were considered as failures. Percussion sensitivity, dentinal bridge formation, and root canal calcification were present in 7.14%, 14.2%, 25% cases at the end of 12 months, respectively. The intragroup result was statistically significant (P < 0.05) in the case of dentine bridge formation, percussion sensitivity, and root canal calcification [Table 1a-c].

Intergroup analysis for all the parameters such as percussion sensitivity, dentin bridge formation, and root canal calcification, showed nonsignificant differences at all the intervals [Table 1a-c]. When comparison was made for success rate, both inter and intragroup analysis showed nonsignificant results at 3, 6, and 12 months follow-ups [Table 2], so the null hypothesis is accepted. The success rate was 80.7% and 92.8% for Group I and Group II, respectively, at the end of 12 months [Figures 1 and 2]. Thirteen patients were diagnosed with apical periodontitis of which eight patients had a periapical radiolucency. 92.4% of patients showed normal response to percussion and 87.5% of the patient showed healing of periapical lesion or improvement in PAI score on CBCT evaluation.

Table 2.

Comparative evaluation of success rate (percentage) between both groups at different follow-up times

| Groups | Follow-up (months) | Within-group comparison (Friedman test) (P) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 3 | 6 | 12 | ||

| I (n=26) | 23 (88.4) | 22 (84.6) | 21 (80.7) | 0.607 |

| II (n=28) | 27 (96.4) | 27 (96.4) | 26 (92.8) | 0.368 |

| Between the groups comparison (Chi-square test) (χ2, P) | 1.248, 0.264 | 2.239, 0.135 | 0.927, 0.336 | |

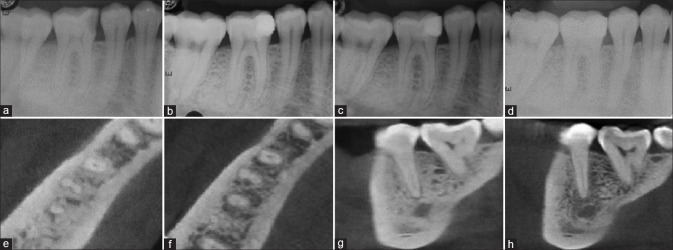

Figure 1.

Representative image of biodentine partial pulpotomy in tooth #46, (a) preoperative radiograph, (b) immediate postoperative, (c) 6-month follow-up, (d) 12-month follow-up, (e) preoperative cone beam computed tomography axial section showing apical periodontitis, (f) 12-month follow-up cone beam computed tomography, (g) preoperative cone beam computed tomography sagittal section, (h) 12-month follow-up cone beam computed tomography showing healing of periapical lesion

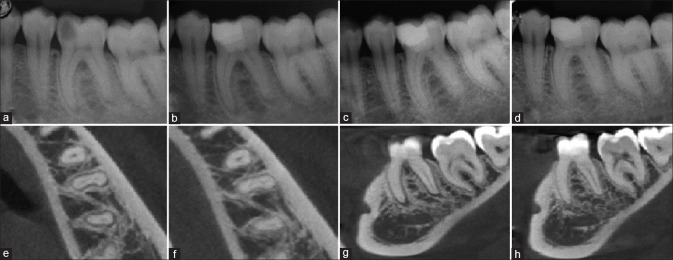

Figure 2.

Representative image of biodentine full pulpotomy in tooth #36, (a) preoperative radiograph, (b) immediate postoperative, (c) 6-month follow-up, (d) 12-month follow-up, (e) preoperative cone beam computed tomography axial section showing apical periodontitis, (f) 12-month follow-up cone beam computed tomography, (g) preoperative cone beam computed tomography sagittal section, (h) 12-month follow-up cone beam computed tomography showing healing of periapical lesion

DISCUSSION

Symptomatic irreversible pulpitis is the main cause for patients who seek dental treatment. Clinical indicators of the irreversible stage of the pulp include sudden or prolonged pain and percussion sensitivity. There is no absolute method to correctly find the depth and size of pulpal inflammation. Although the new study has found increased amounts of biological inflammatory mediators in inflamed pulps, which can assess the degree of pulp inflammation. In recent years, due to more knowledge regarding pulp biology and bioceramic materials, VPT has been grown in popularity alternative to RCT in cases with irreversible pulpitis.[15]

Both partial and full pulpotomy can be recommended in symptomatic irreversible pulpitis. However, there is a lack of study regarding which is better among these. Partial pulpotomy is a more conservative option than full pulpotomy. It retains cell-rich coronal pulp tissue, which may aid healing and maintain physiologic dentine deposition in the coronal area, which aids in the protection of the radicular pulp against dystrophic calcification caused by various pulpotomy agents.[16] However, it is difficult to establish the extent of disease progression clinically in partial pulpotomy to assure full removal of diseased tissue. Coronal pulpotomy, on the other hand, eliminates all inflammatory pulp tissue and creates a solid sheath of the pulp chamber's bottom for correct placement and condensation of the pulp capping agent.

In the present study, all cases were conducted under rubber dam isolation, which resulted in a higher pulpotomy success rate as compared to cotton rolls isolation.[17] The majority of cases took 8–10 min to achieve hemostasis, except 4 cases where we were not able to control profuse bleeding within 10 min which could be because of extensive pulpal inflammation. A study demonstrated that the pulp bleeding control time did not affect the pulpotomy success rate. Three percentage NaOCl was used for hemostasis because it is successful as a hemorrhage control agent in a pulpotomy, with pulps treated with this concentration showing no evidence of pulpal necrosis after 7 and 27 days.[18]

Appropriate sealing with bioactive material and coronal repair are the most important factors in a successful VPT. Biodentine was used as a pulpotomy medicament and a base of RMGIC with composite restoration since it helped to ensure a good postoperative coronal seal. Clinical application of biodentine in pulpotomy as a medicament has been investigated in various clinical studies and case reports in permanent teeth with symptoms of irreversible pulpitis.[7,19,20]

Biodentine showed favorable results with an overall success rate of 87% at 1-year follow-up. This could be due to its obvious advantages which include good sealing ability, biocompatibility, and compressive strength, and more calcium ion released as compared to MTA and calcium hydroxide-based materials.[13,21] Biodentine, when utilized as a capping material in VPT, can induce secretion of TGF-b1 growth factor from the dentine matrix, which can cause pulp mesenchymal stem cells to develop into odontoblast-like cells, resulting in an early form of reparative dentine synthesis.[22] In its early setting phase, biodentine is a weak restorative material, which requires some time for sufficient intrinsic maturation to combat contraction forces from the resin composite. RMGIC was used as a base material in the present study to withstand the contraction forces from the resin composite in its early maturation phase.[23] In this study, permanent restoration was done with composite resin after 1 week. The decline in pulpotomy survival rate over time could be due to microleakage through restoration.

The presence of periapical involvement might not always be associated with pulp necrosis and some part of the pulp tissue may still be vital.[24] On the completion of the study, all teeth that had previously presented with apical radiolucencies showed remineralization and periapical healing. In Group II, there was a significant reduction in percussion sensitivity over the time, after the procedure. It may be due to the higher elimination of inflammatory tissues and bacterial endotoxin. Group I showed more cases of dentine bridge formation than complete pulpotomy. This is due to more cell-rich zone available for odontoblastic differentiation and the formation of tertiary dentin. Obliteration of the pulp canal is a challenge for the clinician. Complete pulpotomy reported a greater number of cases with root canal calcification as compared to partial pulpotomy.

In our study, early failures occurred within 2 weeks which were represented by continuous or intermittent intense spontaneous pain. The possible reason for this is, the limitations of currently available diagnostic aids to correctly diagnose pulpal disease. Necrosis and periapical involvement were mainly associated with delayed failures where bacterial infection may be involved. Studies have reported that 6 months are required to assess the treatment outcome of pulpotomy.[25] Further studies to quantitatively evaluate the parameters should be conducted and studies with longer follow-up periods would help to evaluate the long-term success of pulpotomy in symptomatic vital mature permanent posterior teeth.

CONCLUSION

This study concludes that partial and full pulpotomy both can be considered as a permanent treatment approach over traditional RCT in the management of carious exposed symptomatic irreversible pulpitis or symptomatic apical periodontitis in mature permanent molars.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Endodontists A. Chicago: American Association of Endodontists; 2012. Glossary of Endodontic Terms. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng YL, Mann V, Rahbaran S, Lewsey J, Gulabivala K. Outcome of primary root canal treatment: Systematic review of the literature – Part 1. Effects of study characteristics on probability of success. Int Endod J. 2007;40:921–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Filippo G, Sidhu SK, Chong BS. Apical periodontitis and the technical quality of root canal treatment in an adult sub-population in London. Br Dent J. 2014;216:E22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van der Veken D, Curvers F, Fieuws S, Lambrechts P. Prevalence of apical periodontitis and root filled teeth in a Belgian subpopulation found on CBCT images. Int Endod J. 2017;50:317–29. doi: 10.1111/iej.12631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asgary S, Eghbal MJ, Fazlyab M, Baghban AA, Ghoddusi J. Five-year results of vital pulp therapy in permanent molars with irreversible pulpitis: A non-inferiority multicenter randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;19:335–41. doi: 10.1007/s00784-014-1244-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qudeimat MA, Alyahya A, Hasan AA. Mineral trioxide aggregate pulpotomy for permanent molars with clinical signs indicative of irreversible pulpitis: A preliminary study. Int Endod J. 2017;50:126–34. doi: 10.1111/iej.12614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taha NA, Abdelkhader SZ. Outcome of full pulpotomy using Biodentine in adult patients with symptoms indicative of irreversible pulpitis. Int Endod J. 2018;51:819–28. doi: 10.1111/iej.12903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asgary S, Eghbal MJ, Shahravan A, Saberi E, Baghban AA, Parhizkar A. Outcomes of root canal therapy or full pulpotomy using two endodontic biomaterials in mature permanent teeth: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Oral Invest. 2021;26:3287–97. doi: 10.1007/s00784-021-04310-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ricucci D, Loghin S, Siqueira JF., Jr Correlation between clinical and histologic pulp diagnoses. J Endod. 2014;40:1932–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zafar K, Nazeer MR, Ghafoor R, Khan FR. Success of pulpotomy in mature permanent teeth with irreversible pulpitis: A systematic review. J Conserv Dent. 2020;23:121–5. doi: 10.4103/JCD.JCD_179_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santos JM, Pereira JF, Marques A, Sequeira DB, Friedman S. Vital pulp therapy in permanent mature posterior teeth with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis: A systematic review of treatment outcomes. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021;57:573. doi: 10.3390/medicina57060573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cushley S, Duncan HF, Lappin MJ, Tomson PL, Lundy FT, Cooper P, et al. Pulpotomy for mature carious teeth with symptoms of irreversible pulpitis: A systematic review. J Dent. 2019;88:103158. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2019.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Docimo R, Ferrante Carrante V, Costacurta M. The physical-mechanical properties and biocompatibility of BiodentineTM: A review. J Osseointegr. 2021;13:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fathy SM. Remineralization ability of two hydraulic calcium-silicate based dental pulp capping materials: Cell-independent model. J Clin Exp Dent. 2019;11:e360–6. doi: 10.4317/jced.55689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alqaderi H, Lee CT, Borzangy S, Pagonis TC. Coronal pulpotomy for cariously exposed permanent posterior teeth with closed apices: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2016;44:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fong CD, Davis MJ. Partial pulpotomy for immature permanent teeth, its present and future. Pediatr Dent. 2002;24:29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qudeimat MA, Barrieshi-Nusair KM, Owais AI. Calcium hydroxide vs mineral trioxide aggregates for partial pulpotomy of permanent molars with deep caries. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2007;8:99–104. doi: 10.1007/BF03262577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hafez AA, Cox CF, Tarim B, Otsuki M, Akimoto N. An in vivo evaluation of hemorrhage control using sodium hypochlorite and direct capping with a one- or two-component adhesive system in exposed nonhuman primate pulps. Quintessence Int. 2002;33:261–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chinadet W, Sutharaphan T, Chompu-Inwai P. Biodentine™ partial pulpotomy of a young permanent molar with signs and symptoms indicative of irreversible pulpitis and periapical lesion: A case report of a five-year follow-up. Case Rep Dent. 2019;2019:8153250. doi: 10.1155/2019/8153250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seck A, Lèye-Benoist F, Touré B, Youssef H. The demand for emergency care after pulpotomy with Biodentine® on permanent molars with irreversible acute pulpitis: Clinical trial study. Saudi Endod J. 2021;11:339–44. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinkar RC, Patil SS, Jogad NP, Gade VJ. Comparison of sealing ability of ProRoot MTA, RetroMTA, and Biodentine as furcation repair materials: An ultraviolet spectrophotometric analysis. J Conserv Dent. 2015;18:445–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.168803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laurent P, Camps J, About I. Biodentine™ induces TGF-β1 release from human pulp cells and early dental pulp mineralization. Int Endod J. 2012;45:439–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashem DF, Foxton R, Manoharan A, Watson TF, Banerjee A. The physical characteristics of resin composite-calcium silicate interface as part of a layered/laminate adhesive restoration. Dent Mater. 2014;30:343–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ricucci D, Pascon EA, Ford TR, Langeland K. Epithelium and bacteria in periapical lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:239–49. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zanini M, Hennequin M, Cousson PY. A review of criteria for the evaluation of pulpotomy outcomes in mature permanent teeth. J Endod. 2016;42:1167–74. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]