Abstract

Cultural psychologists often treat binary contrasts of West versus East, individualism versus collectivism, and independent versus interdependent self-construal as interchangeable, thus assuming that collectivist societies promote interdependent rather than independent models of selfhood. At odds with this assumption, existing data indicate that Latin American societies emphasize collectivist values at least as strongly as Confucian East Asian societies, but they emphasize most forms of independent self-construal at least as strongly as Western societies. We argue that these seemingly “anomalous” findings can be explained by societal differences in modes of subsistence (herding vs. rice farming), colonial histories (frontier settlement), cultural heterogeneity, religious heritage, and societal organization (relational mobility, loose norms, honor logic) and that they cohere with other indices of contemporary psychological culture. We conclude that the common view linking collectivist values with interdependent self-construal needs revision. Global cultures are diverse, and researchers should pay more attention to societies beyond “the West” and East Asia. Our contribution concurrently illustrates the value of learning from unexpected results and the crucial importance of exploratory research in psychological science.

Keywords: collectivism, individualism, cultural binary, cultural models of selfhood, independent self-construal, interdependent self-construal, Latin American culture

Feelings of being miscomprehended in my culture . . . led me to strongly criticize previous work on cross-cultural psychology that still uses, sometimes unintentionally, the terms of Western and Eastern, where cultures such as Latin American don’t fit and are made invisible.

—K. M. (Chilean student of cross-cultural psychology)

Psychological perspectives on cultural variation, such as individualism–collectivism theory (Triandis, 1995) and self-construal theory (Markus & Kitayama, 1991), aim to capture patterns of substantive similarities and differences between different societies, even if the societies in question are geographically distant. Thus, people living in societies labeled collectivistic—such as China and Mexico (Hofstede, 2001)—are commonly assumed to share similarly collectivistic values and worldviews and similarly interdependent rather than independent models of selfhood. These theories aim to provide a psychology that is more globally representative—recognizing cultural differences, explaining where and why they occur, and predicting psychological and social consequences. However, the empirical literature has been heavily reliant on comparing participants from a small number of societies, mostly in Anglo America and East Asia (Matsumoto, 1999; Vignoles, 2018).

What happens when findings from diverse world regions fail to fit the expected pattern? Sometimes these troubling findings may be dismissed as “anomalies,” forcing the kaleidoscopic diversity of global cultures into an oversimplified “binary” model of cultural differences (for discussions, see Hermans & Kempen, 1998; Muthukrishna et al., 2020; Vignoles, 2018). In this way, cultures of less powerful or less affluent world regions may be misrepresented or even omitted entirely from the scientific discourse. Here, in a spirit of cross-cultural exploration, we try to see what we might learn from such findings.

We focus here on one such “anomaly”: Members of Latin American societies tend to report relatively independent self-construals compared with people in other world regions. We have seen this result repeatedly in our own research (Krys, Zelenski, et al., 2019; Vignoles et al., 2016). However, we have listened to highly respected colleagues at conferences and read peer reviews of our submitted manuscripts, declaring that this “cannot be right” and “there must be something wrong with the measurement.” We have also heard from Latin American colleagues that studies comparing patterns of self-construal in their countries against other world regions often go unreported and, if written up, are frequently rejected for publication—perhaps in part because their results are inconsistent with self-construal theory.

This article traces the steps by which we came to trust what these data were telling us, making sense of this finding rather than presuming it “must be wrong.” First, we introduce the prevailing theorizing around individualism–collectivism and models of selfhood, noting the scarcity of evidence from locations other than Western and Confucian East Asian societies. Second, findings of a quantitative synthesis show that the prevalence of independent forms of self-construal in Latin American cultures was replicated in all large-scale multinational studies that we could access. Thus, rather than an anomaly, this is a consistent finding that merits theoretical explanation. Third, we aim to provide such an explanation by focusing on societal and historical characteristics, as well as dimensions of psychological culture, that differentiate Latin American from Confucian East Asian societies. Fourth, we address some possible objections to our theoretical account. Finally, we consider some broader implications for theorizing and research about culture and psychology.

Individualism–collectivism and Self-Construal Theory

Among numerous dimensions of cultural differences, individualism–collectivism has gained the largest interest in psychological science. Hui and Triandis (1986) proposed that what differentiates individualist from collectivist cultures is “the basic unit of survival”: In individualist cultures, this is an individual person, whereas in collectivistic cultures it is a group. Studies of psychological consequences and correlates of individualism–collectivism intensified after Hofstede (1980) provided the first empirical mapping of national variation in cultural values. From Hofstede’s four original cultural dimensions, individualism–collectivism received the most positive reception from psychologists, especially in the United States, which was the most individualistic country according to Hofstede’s findings.

Hofstede’s (1980) measurement of individualism–collectivism led researchers to ask how this culture-level dimension “translates” into individual-level psychological processes. To answer this question, many turned to Markus and Kitayama’s (1991, 2010) highly influential theory of self-construals. Markus and Kitayama (1991) argued that macrolevel sociocultural contexts and psychological functioning mutually constituted each other, and central to this was how people in different societies construed themselves in relation to others. Specifically, they proposed that East Asian cultures promoted an emphasis on interdependent self-construal, whereas Anglo American culture promoted an emphasis on independent self-construal:

Many Asian cultures have distinct conceptions of individuality that insist on the fundamental relatedness of individuals to each other. The emphasis is on attending to others, fitting in, and harmonious interdependence with them. American culture neither assumes nor values such an overt connectedness among individuals. In contrast, individuals seek to maintain their independence from others by attending to the self and by discovering and expressing their unique inner attributes. (p. 224)

Markus and Kitayama (1991) supported their theorizing with empirical evidence garnered mostly from Confucian East Asian and Euro-American cultural contexts. Notably, they did not focus on the cultural dimension of individualism–collectivism—although they included this dimension in a long list of constructs that they speculated might be linked to self-construals. Nevertheless, their claim that the interdependent self-construal “is also characteristic of African cultures, Latin-American cultures, and many southern European cultures” (p. 225) may have inspired subsequent researchers to assume that collectivistic cultural contexts should foster interdependent self-construal. This assumption is now so little questioned that contrasts of independence versus interdependence and individualism versus collectivism are often treated as interchangeable both in their theoretical definition and in their measurement (e.g., Effron et al., 2018; Oyserman et al., 2002).

We believe that extrapolating theorizing about self-construals from Confucian Asia to other collectivist world regions may be an overgeneralization (see Matsumoto, 1999). Since the emergence of self-construal theory, theorizing on individualism–collectivism has grown. Cross-cultural psychologists now understand collectivism as a multifaceted construct, and so geographical regions may be characterized by qualitatively different “collectivisms” (Kim, 1994; Oyserman et al., 2002; Singelis et al., 1995; Triandis, 1993). This raises the possibility of a novel revision to the common view in self-construal research: Some collectivistic societies may foster independent forms of selfhood depending on their historical backgrounds and socioecological niches.

Just as theorizing about self-construals originated from comparing Anglo American and European individualism with Confucian collectivism, empirical evidence collected in the subsequent almost 30 years still comes mostly from these two world regions (Fig. 1; see Section S1 and Tables S1–S3 in the Supplemental Material available online). Although consistent with the overrepresentation of Western and Confucian cultures in psychology more generally (Henrich et al., 2010), this is very troubling for a literature that aims to highlight the importance of cultural diversity. The underrepresentation of Latin American cultures in the self-construal literature is potentially even more concerning given the anecdotal reports mentioned earlier that self-construal studies from this region can be harder to publish because of their theoretically inconvenient findings. This raises the possibility that there may be a substantial file-drawer problem for research into Latin American models of selfhood and consequently that the field may be missing a major opportunity for theoretical growth based on unexpected and novel findings that are hidden from sight.

Fig. 1.

Locations for which self-construals were studied. Results were quantified on the basis of all articles indexed in EBSCO that mention the term “self-construal” and a name of any country in a title or abstract. For details of our analyses, see Section S1 and Tables S1 through S3 in the Supplemental Material.

Characterizing Self-Construal in Latin American Societies

The authors’ interest in this question began with a discovery that two of us had found a similar pattern of unexpected results regarding self-construal in Latin American cultures. Krys, Zelenski, et al. (2019) found that samples from two Latin American countries had the highest mean independent self-construals and the lowest mean interdependent self-construals among the 12 nations in their study. Vignoles et al. (2016) found that Latin American samples on average emphasized independence (vs. interdependence) at least as much as Western samples on six of the seven self-construal dimensions they measured. These findings were strikingly at odds with the prevailing theoretical expectation that Latin American cultures should emphasize interdependent rather than independent self-construal.

We wanted to see whether these findings were part of a broader pattern. Hence, we conducted a quantitative synthesis (Johnson & Eagly, 2000) of multinational studies on self-construals. We compared mean self-construal scores of samples from Latin American and Confucian East Asian countries—commonly described as collectivistic—and from countries of Northwestern European heritage—commonly described as individualistic (see Section S2 and Table S4 in the Supplemental Material). We identified four major international projects that included measures of self-construal from samples in eight or more countries. Three studies, covering 49 cultural samples from 39 countries, used versions of the Singelis (1994) self-construal scale to measure independence and interdependence as separate dimensions (Church et al., 2013; Fernandez et al., 2005; Krys, Zelenski, et al., 2019); the fourth study, covering 55 cultural samples from 33 countries, measured seven bipolar dimensions of self-construal, each contrasting a way of being independent with a way of being interdependent (e.g., difference vs. similarity; self-reliance vs. dependence on others; Vignoles et al., 2016). A full report of our quantitative synthesis can be found in Section S3 and Table S5 in the Supplemental Material.

Findings using the Singelis scale

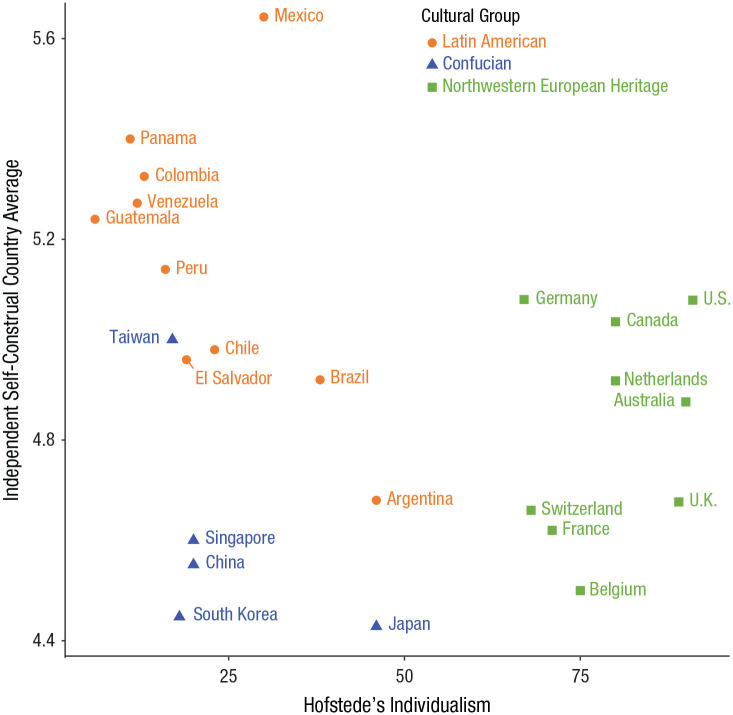

In all three studies using versions of the Singelis (1994) scale, Latin American countries scored significantly higher on independent self-construals than Confucian countries; they also scored significantly higher than countries of Northwestern European heritage. In none of these studies was there a significant difference between Latin American and Confucian countries in interdependent self-construals, and thus the results cannot easily be explained away by differences in scale usage. Using two different approaches to pooling the data, we found that Latin American samples reported significantly more independent selves than Confucian Asians, and the effect size was very large (Cohen’s d > 2.2). Moreover, Latin Americans reported significantly more independent selves than samples from countries of Northwestern European heritage (d > 1.4). Figure 2 shows pooled independence scores for the three groups of countries plotted against Hofstede’s measure of individualism–collectivism.

Fig. 2.

Rescaled independent self-construal country averages graphed as a function of Hofstede’s measure of individualism, separately for countries from three different cultural regions (Northwestern European heritage, Latin America, and Confucian East Asia). The plot shows that Latin American societies, although collectivistic, foster independent self-construal. For details of our analyses, see Section S3 and Table S5 in the Supplemental Material available online.

These findings showed a clear pattern: Samples from Latin American countries rated themselves higher on independence than those from Confucian countries—and samples from countries of Northwestern European heritage occupied an intermediate position. However, cross-cultural studies using Singelis’s (1994) self-construal scale have often reported problems of poor reliability or cross-cultural nonequivalence. The scale may be affected by cultural variation in response styles, and it does not distinguish ways of being independent or interdependent. Moreover, all three studies using the Singelis scale relied on student samples.

Findings using the Vignoles et al. scale

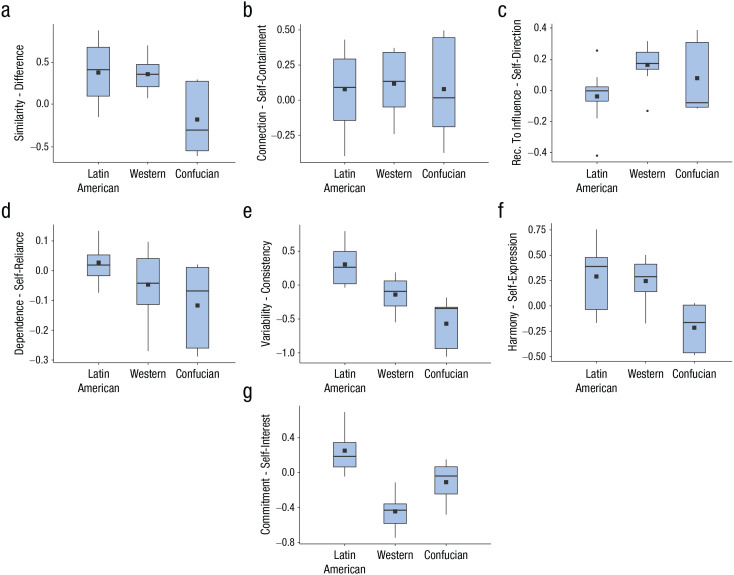

Addressing these limitations, Vignoles et al. (2016) distinguished seven dimensions of psychological functioning that were previously confounded within commonly used measures of independence and interdependence, and they reported culture-level factor scores, adjusted for age, gender, and acquiescent response styles, for adult samples from 55 cultural groups spanning 33 countries. We reanalyzed their scores for 24 cultural samples residing in the three cultural regions of interest. In five of the seven dimensions, models of selfhood in Latin American samples were significantly more independent than those in Confucian samples (d = 1.33–2.50) and at least as independent as those in samples from countries of Northwestern European heritage (see Fig. 3). Thus, evidence for a focus on independent self-construal in Latin American cultures cannot be explained away in terms of measurement problems with the Singelis (1994) scale, and it is not an artifact of relying on student samples.

Fig. 3.

A comparison of samples from Latin American societies, Confucian Asian societies, and societies of Northwestern European (“Western”) heritage on the seven dimensions of self-construal measured by Vignoles et al. (2016). For each dimension, the box shows the interquartile range (IQR), the horizontal bar indicates the median, the square shows the mean, the whiskers go out to the most extreme data points that fall within 1.5× the IQR below the 25th percentile and above the 75th percentile, and the circles indicate observed values that fall outside this range (i.e., outliers). Higher scores indicate higher independence (vs. interdependence). The plot shows that there are differences between Latin America and Confucian Asia on five of the seven measured dimensions. For further details and tests of statistical significance, see Section S3 and Table S5 in the Supplemental Material.

The seven-factor structure of the measure from Vignoles et al. (2016) also provides a finer-grained picture of prevailing models of selfhood across the three cultural regions. Samples from the three regions did not differ significantly in experiencing the self as self-contained versus connected to others, and Latin American samples reported the greatest receptivity to influence, rather than self-direction, when making decisions. Western and Latin American forms of independent selfhood differed not only in magnitude but also in kind: Both regions shared an independent focus in defining the self (difference) and in communicating with others (self-expression), but Western samples more strongly emphasized self-direction (vs. receptivity to influence) in making decisions, whereas Latin American samples more strongly emphasized consistency (vs. variability) in moving between contexts and self-interest (vs. commitment to others) in dealing with conflicting interests.

Making Sense of the Findings: Latin America Is Not Confucian Asia

Our quantitative synthesis paints a picture of models of selfhood in collectivistic Latin American societies that differs markedly from common theorizing on culture and self. Moreover, initial results from our ongoing research have continued to show a similar pattern (e.g., Krys, Park, et al., 2021; Yang, 2018). Far from being an anomaly, the emphasis on forms of independence in Latin American cultural models of selfhood is a consistent finding obtained repeatedly in large-scale cross-cultural studies among student and adult participants and using different measures and models of self-construal. This represents a notable challenge to the widely held assumption in cultural psychology that collectivist cultures will usually, or even by definition, foster interdependent models of selfhood. These findings deserve to be taken seriously and understood rather than being brushed under the carpet.

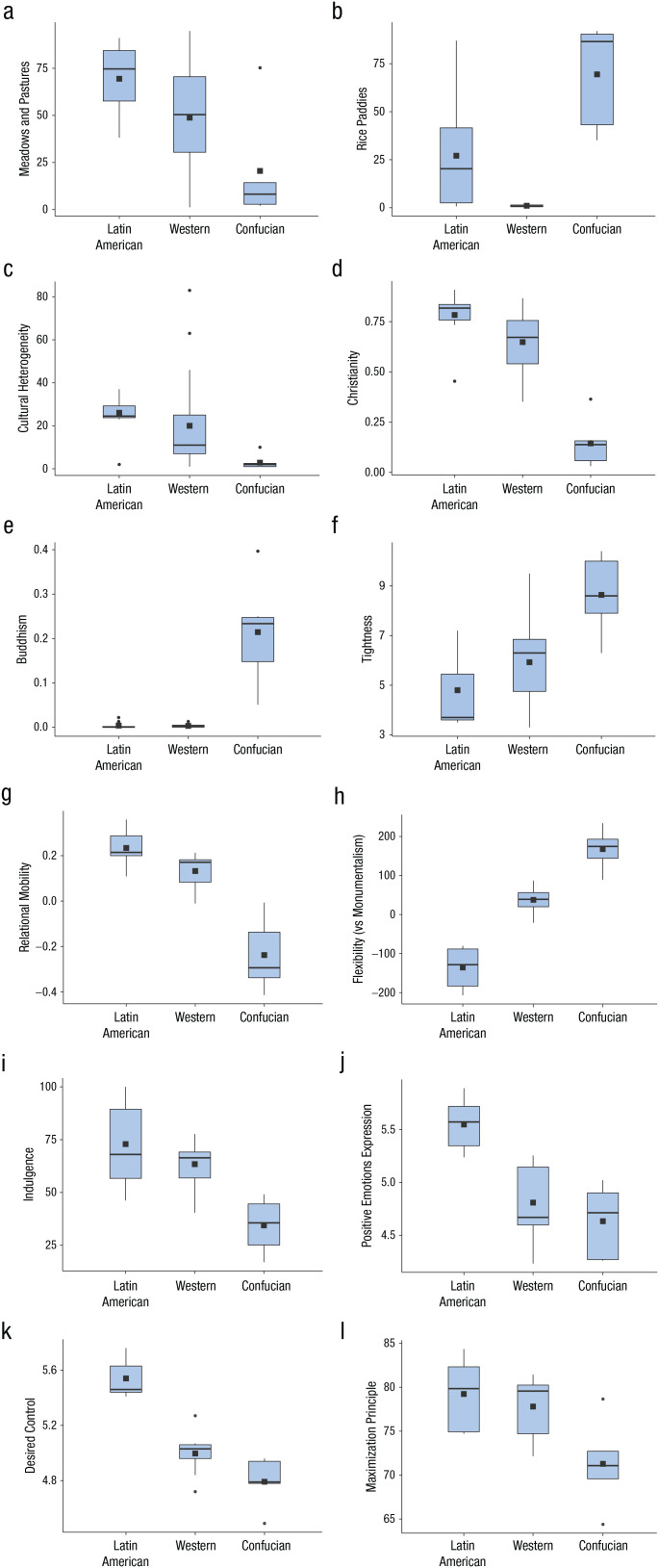

We therefore began looking for reasons why these findings might be true rather than why they might be false. Cross-cultural researchers have identified differences between Confucian Asian and Latin American samples on numerous dimensions of cultural variation other than individualism–collectivism. We reasoned that perhaps these differences—rather than individualism–collectivism—might explain the observed differences in models of selfhood. We identified and reviewed various cultural characteristics that could theoretically be linked to models of selfhood and for which multinational quantifications were available in the psychological literature (see Section S4 in the Supplemental Material). For many dimensions, Latin American cultures were positioned on the opposite pole from Confucian cultures, and Western cultures were somewhere in between (Fig. 4; also see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material). Thus, we began to form a more comprehensive theoretical explanation for the observed differences between Confucian Asian and Latin American models of selfhood, drawing on recent theorizing and research into the socioecological and historical origins of cultural independence and interdependence (e.g., Kitayama et al., 2006; Kitayama & Uskul, 2011; Talhelm et al., 2014; Uchida et al., 2019).

Fig. 4.

A comparison of data from Latin American societies, Confucian Asian societies, and societies of Northwestern European (“Western”) heritage on many characteristics that could potentially account for the prevalence of independent forms of self-construal. For each dimension, the box shows the interquartile range (IQR), the horizontal bar indicates the median, the square shows the mean, the whiskers go out to the most extreme data points that fall within 1.5× the IQR below the 25th percentile and above the 75th percentile, and the circles indicate observed values that fall outside this range (i.e., outliers). For further details and tests of statistical significance, see Section S4 and Table S6 in the Supplemental Material.

Socioecological and historical differences

Contemporary perspectives in socioecological psychology (e.g., Uskul & Oishi, 2020) and cultural evolution (e.g., Mesoudi et al., 2006) seek to understand the patterns of self-construal, values, and norms that prevail in different societies as cultural adaptations to particular socioecological and historical circumstances (Uchida et al., 2020). Confucian Asian and Latin American societies notably occupy very different socioecological and historical contexts in terms of modes of subsistence (prevalence of rice farming vs. herding and other types of farming), colonial histories (occupation vs. frontier settlement), ethnic diversity (homogeneous vs. heterogeneous), and religious heritage (Buddhist vs. Christian).

Subsistence modes

Socioecological psychology asserts that cultural beliefs and practices are shaped in part by modes of subsistence (Uskul & Oishi, 2020): Modes of subsistence that allow for greater geographical mobility, as in traditional herding communities as well as contemporary industrialized societies, will tend to foster more independent modes of being, whereas modes of subsistence that tie people to a specific geographical location, such as farming and most especially rice growing, will tend to foster more interdependent modes of being. In addition, herding may be linked to independent selfhoods via low population density (which hampers establishing macrosocial institutions such as policing) and via relatively low labor-skill requirements (which do not require cooperative labor with other specialists). Such influences are thought to occur not only among those individuals who are directly involved in food production but also at a societal level (Talhelm et al., 2014; Uchida et al., 2019).

Notably, in the year 2000, Latin American societies on average dedicated almost 70% of their agricultural land to meadows and pastures (i.e., herding), whereas the corresponding figure for Confucian Asian societies was around 20%; conversely, rice paddies occupied on average almost 70% of land used for cereal production in Confucian societies but less than 30% in Latin American societies (Fig. 4; also see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material). Because prevailing modes of food production are more conducive to geographical mobility in Latin American societies than Confucian Asian societies, socioecological theory predicts that Latin American societies should have more independent and less interdependent models of selfhood. The link between subsistence and models of selfhood may be explained by differences in relational mobility (as discussed below), which is also much higher in Latin American than in Confucian Asian societies (Thomson et al., 2018).

History of frontier settlement

Beyond subsistence modes, Kitayama and colleagues (2006) argued that a history of frontier settlement may foster a “spirit of independence” in certain nations or communities. They proposed that frontier settlement will likely attract independently minded individuals, that independence will be adaptive for survival in the harsh and unprotected circumstances of frontier life, and that those who are attracted to and survive frontier life will likely pass on their beliefs and values to subsequent generations. The frontier-settlement hypothesis has been used to explain cultural differences between sedentary and settler societies in Europe, North America, and Australasia (Varnum & Kitayama, 2011) and between regions that were more or less recently settled within Japan (Ishii et al., 2014; Kitayama et al., 2006), China (Feng et al., 2017), the United States, and Canada (Varnum & Kitayama, 2011).

The world regions of Latin America and Confucian Asia have had very different recent colonial histories. Some, but not all, Confucian Asian countries experienced occupation and exploitation by European colonizing nations, and indigenous rule was returned to most societies after independence; in contrast, countries in Latin America were typically subject to settler colonialism, in which indigenous populations were—and often still are—eliminated, displaced, marginalized, or assimilated by European settlers and their descendants (Veracini, 2010). Kashima et al. (2011) used frontier-settlement theory to predict that members of Latin American societies would show more independent forms of selfhood than would members of the Southern European societies from which they were colonized. To our knowledge, their specific prediction has not been tested directly, but it seems consistent with our current finding that models of selfhood in Latin American countries show a relatively strong focus on independence. Arguably, the greater focus on self-reliance (vs. dependence on others) and self-interest (vs. commitment to others) in Latin American societies may be especially adaptive for frontier settlement, in which individuals should not expect to depend on others nor that others will depend on them.

Cultural heterogeneity

Given their differing colonial histories, Latin American and Confucian Asian societies differ also in contemporary cultural heterogeneity. According to Putterman and Weil’s (2010) World Migration Matrix, Japan, Korea, China, and Taiwan are among the most culturally homogeneous societies. The most diverse are the United States, Canada, and Australia, followed by Latin American societies: Argentina, Panama, Chile, and Uruguay. The difference in cultural heterogeneity between Latin American and Confucian Asian societies reaches over 4 SD (Fig. 4; also see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material).

We suspect that cultural homogeneity may foster a predominance of interdependent selfhood in a given society. Feelings of relatedness to others and an emphasis on fitting in may be easier when common cultural scripts and norms are shared by members of a given society. In contrast, cultural heterogeneity may allow more scope for expressing unique cultural attributes, exploring differences in cultural backgrounds, and negotiating cultural identities. Therefore, we propose that cultural heterogeneity of a society may foster independent models of selfhood—perhaps especially on the dimensions of difference (vs. similarity) and self-expression (vs. harmony), both of which were emphasized in Latin American compared with Confucian societies in our quantitative synthesis.

Religious and philosophical traditions

Societies of Confucian Asia and Latin America also have markedly different religious and philosophical traditions. Christianity is the major religion in Latin America, whereas Buddhism has significant influence in Confucian Asia (Fig. 4; also see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material). Christian and Buddhist religious traditions have respectively been linked to independent and interdependent models of selfhood (e.g., Ho, 1995; Sampson, 2000).

Confucian philosophy advocates interdependence through its focus on the five cardinal relationships, and Confucian ethical concepts are based on benevolence and humaneness that manifest in compassion and harmony with others. Confucian societies have also been shaped extensively by Buddhist and Taoist belief systems, each of which advocates interdependence in different ways (see Ho, 1995). In Buddhism, humans are only one of many sentient beings, and in Taoism humans are but one extension of the cosmos. Ideas of human rebirth, the endless cycle of life, and karma foster harmonious and interdependent ways of being. Likewise, in Zen Buddhist philosophy, being a human means being self-aware of one’s place within the universe and one’s own limitations, as well as affirming what the circumstances bring to a person and that one needs to accept the fate and flow of experience.

Christianity’s influence has been dominant in Latin America since colonization. Most people in Latin America now self-identify as Christians (Fig. 4; also see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material). Christianity has often been linked to independent models of selfhood that emphasize self-sufficiency, autonomy, and a focus on the individual (Cohen, 2015; Sampson, 2000). Writings linking Christianity to independent selfhood often focus on the Protestant doctrine that every individual has a unique and unmediated relationship with God (e.g., Henrich, 2020), but this doctrine can also be found in contemporary Catholicism (Wooden, 2020). By giving humans a dominant position over nature (as in common understandings of Genesis 1:26), Christianity advances an independent view of human selfhood as self-directed and self-reliant—in marked contrast to Confucian, Buddhist, and Taoist thinking.

Differences in societal organization

Given their very different socioecological and historical contexts, one might expect that Confucian Asian and Latin American societies would show different patterns of societal organization. We focus here on three dimensions of societal organization that have gained prominence in recent cross-cultural studies: Compared with Confucian societies, Latin American societies have been characterized by higher relational mobility, looser norms, and social interactions guided by honor logic rather than face logic.

High versus low relational mobility

Relational mobility refers to “how much freedom and opportunity a society affords individuals to choose and dispose of interpersonal relationships based on personal preference” (Thomson et al., 2018, p. 7521; Yuki & Takemura, 2014). In societies with low relational mobility, relationships are mostly fixed; members of these societies engage in stable and long-lasting relationships, and their choice of friends, family, or romantic partners is relatively limited. In societies with high relational mobility, relationship options are more flexible; members of these societies more easily seek out new partners and leave old friends behind. Across 39 countries, Thomson et al. (2018) found that societies with the lowest relational mobility included Japan, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, whereas societies with the highest relational mobility included Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico, and Brazil. The difference in mean relational-mobility scores between Latin American and Confucian Asian samples reaches almost 4 SD (Fig. 4; also see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material).

Where relationships are fixed, the stakes of potentially disrupting a relationship will be much higher (Sato et al., 2014), and so a cautious and nondisruptive approach to self-other relationships would be more adaptive, such as maintaining harmony, accepting influence from others, adapting to fit the situation, and not differentiating oneself from others (i.e., forms of interdependence). In contrast, the greater flexibility of a high relational-mobility context may provide scope for socially riskier ways of being, such as differentiating oneself from others, behaving consistently across contexts, speaking one’s mind even if this disrupts harmony, or resisting social influence (i.e., forms of independence). Three of these four ways of being independent (vs. interdependent) were higher in Latin American than Confucian societies in our quantitative synthesis. Thomson et al. (2018) reported that several aspects of independence (vs. interdependence) covaried positively with national scores for relational mobility. Thus, relational mobility potentially may mediate between mobile (vs. sedentary) subsistence modes and models of selfhood.

Loose versus tight norms

According to Gelfand et al. (2011), tight cultures have strong norms and a low tolerance of deviant behavior, whereas loose cultures are characterized by weak norms and a relatively higher tolerance of deviant behavior. Although Gelfand et al. attributed differences in tightness and looseness mainly to the presence of ecological threats, looseness has also been associated with differences in relational mobility (Thomson et al., 2018). Notably, Gelfand et al. quantified Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong among the tightest cultures and Venezuela and Brazil among the loosest cultures among samples from 33 nations. The difference in tightness scores between Latin American and Confucian samples reaches over 2 SD (Fig. 4; also see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material).

Tight and loose societal environments are likely to be associated with interdependent and independent construals of self, respectively. Living in a tight culture imposes a necessity of conforming to social rules, and thus it might foster certain forms of interdependence, such as similarity to others, harmony in communication, and variability across contexts. Loose cultures, with their tolerance or even promotion of diverse “good ways of being,” would be expected to foster independent construals of self—especially a focus on difference, self-expression, and consistency across contexts, all of which were stronger among Latin American than Confucian Asian samples in our quantitative synthesis.

Cultural logics of honor versus face

Leung and Cohen (2011) proposed three different cultural logics linking culture and self: dignity, face, and honor. The latter two they described as different types of collectivism, locating face logic in Confucian Asia and honor logic within Latin America and the southern United States. According to Leung and Cohen, “whereas honor is contested in a competitive environment of rough equals, face exists in settled hierarchies that are essentially cooperative” (p. 510). Researchers have not yet provided a widely accepted quantification of national cultures for dignity, face, and honor logics. However, several differences in psychological culture that we review next are consistent with viewing Latin American societies as guided by honor logic and Confucian Asian societies as guided by face logic.

In face cultures, individual worth is defined by what others see. People are expected to respect social hierarchy, display humility, and curtail self-expression in the interest of social harmony—which is consistent with the observed greater emphasis on harmony (vs. self-expression) in Confucian Asian compared with Latin American societies. In honor cultures, however, an individual’s worth has both external and internal qualities. Honor can be gained, but it also can be taken away. Competition with others is a way of proving one’s honor, and expressions of toughness and individuality play an important role in building the image of an honorable person (Leung & Cohen, 2011). This is consistent with the observed greater emphases on self-reliance (vs. dependence on others), consistency (vs. variability), and self-interest (vs. commitment to others) in Latin American compared with Confucian Asian societies.

Differences in psychological culture

Cross-cultural psychologists have identified numerous differences in psychological culture that are consistent with the socioecological, historical, and societal differences between Confucian Asian and Latin American cultures. This may help to explain further, as well as corroborate, the self-construal differences found in our quantitative synthesis.

Flexibility versus monumentalism

In a revision of Hofstede’s (2001) model of cultural dimensions, Minkov (2018) and Minkov et al. (2017, 2018) concluded that East Asian and Latin American societies occupy similar positions on the dimension of individualism–collectivism but tend to be at opposite poles of a cross-cutting dimension called “flexibility versus monumentalism.” The difference in flexibility versus monumentalism scores between Latin American and Confucian samples reaches almost 6 SD (Fig. 4; also see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material).

Minkov et al. (2018) defined this dimension explicitly in terms of contrasting models of selfhood. Flexibility refers to an emphasis on modesty, humility, and contextual variability, which is especially characteristic of East Asian (i.e., Confucian) societies and resonates with the concept of face logic; monumentalism refers to an emphasis on pride, dignity, and stability—metaphorically resembling the qualities of a statue or monument—which is strongest in Latin American, Arab, and African societies and resonates with the concept of honor logic. Note that these theoretical definitions echo aspects of Markus and Kitayama’s (1991) distinction between interdependence and independence, raising the possibility that flexibility-monumentalism, over and above individualism–collectivism, may be an important cultural predictor of independent and interdependent ways of being. Forms of independent self-construal such as consistency and self-reliance may be fostered by monumentalist rather than individualist cultures, explaining their prevalence in Latin America.

Indulgence versus restraint

A further addition to Hofstede’s (2001) model is the distinction between indulgence and restraint cultures (Hofstede et al., 2010). Indulgence cultures allow relatively free gratification of human drives, cultivating joy and fun-seeking. Citizens of these countries value freedom of speech and leisure rather than maintaining order in the society. Such contexts, we claim, foster the expression of unique personal attributes and recognize individual drives as important motivators—supporting independent forms of selfhood. The top four societies in Hofstede’s indulgence ranking are Venezuela, Mexico, Puerto Rico, and El Salvador. Restraint cultures, in contrast, suppress gratification of needs and control satisfaction of natural drives with strict social norms. The stricter moral discipline, stricter sexual mores, and higher valuation of order that characterize restraint cultures may lay foundations for the emergence of interdependent selfhoods. The gap between Latin American and Confucian countries on the indulgence versus restraint dimension is more than 2 SD (Fig. 4; also see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material).

High versus low emotional expression

The distinction between indulgence and restraint is corroborated by cross-cultural research into the expression and valuation of emotions. Ethnographic studies document that a norm of moderating or restraining one’s emotions is a core feature of Confucian cultures (Potter, 1988), whereas Latin American cultures have been characterized by free, frequent, and intensive expression of emotions (Garza, 1978). Psychological studies support these portrayals (Murata et al., 2013; Soto et al., 2005). People shaped by Confucian Asian cultures are described as suppressing their emotions (Matsumoto et al., 2008) and preferring low-arousal emotions (Tsai et al., 2006); expression of emotions in Confucian contexts is relational in nature (Uchida et al., 2009), consistent with interdependent forms of selfhood. In contrast, free and frequent expression of emotions in Latin American cultures (Ruby et al., 2012) suggests a societal environment facilitating independent forms of selfhood, such as self-expression (Vignoles et al., 2016). Some even describe high emotional expression as a constitutive feature of Latin American cultures: It is said to be through vibrant positive emotions that Latin Americans connect and reinforce their social connections (De Almeida & Uchida, 2018; Triandis et al., 1984).

Figure 4 and Table S6 in the Supplemental Material compare country characteristics for emotion expression (from Krys, Yeung, et al., 2022). Although Confucian and Latin American countries do not differ on the frequency of expressing negative emotions, members of Latin American societies significantly more often report expressing positive emotions (with a difference reaching over 3 SD; see Fig. 4). Studies on emotion experience (Kuppens et al., 2008) and emotion suppression (Matsumoto et al., 2008) lend additional support to our claims (see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material).

High versus low perceived and desired control

People across cultures vary in perceived and desired control over their environment and life. Weisz et al. (1984) proposed that control is perceived as less attainable and less desirable in Japan than in the United States, attributing this difference to a religious and philosophical legacy of Buddhism. Hornsey et al. (2019) tested this assumption in two studies (Study 1, N = 38 nations; Study 2, N = 27 nations) and found lower levels of perceived and desired control in Japan than in any other nation. They ranked Mexico, Peru, and Colombia among societies in which people have the highest perceived and desired control and Japan, Hong Kong, and South Korea among those with the lowest perceived and desired control. Using their data, we found a significant difference between Latin American and Confucian societies that reaches over 4 SD for desired control and almost 3 SD for perceived control (Fig. 4; also see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material).

High desired control is linked to assertiveness, competitiveness, differentiation, goal achievement (Haase et al., 2009), and a focus on influencing one’s social environment (Hornsey et al., 2019). Low desired control, in contrast, can be linked to fitting in, sensitivity to others, adapting to environments, and accepting the “natural flow of things.” Thus, we believe that differences in perceived and desired control may especially help to explain the prevalence of self-reliance (vs. a willingness to depend on others and thus relinquish control to them) and consistency (vs. a willingness to let the context determine one’s actions) in Latin American compared with Confucian Asian societies.

High versus low endorsement of maximization principle

People across cultures vary in what they believe should be the ideal level of qualities they consider positive. Although the maximization principle—to aspire to the highest possible level of something good—has long been considered a basic assumption about human nature, Hornsey et al. (2018) showed that it is more endorsed in some cultures than in others. They asked about seven ideals for the self, and nine ideals for society, to test their prediction that “holistic” and “nonholistic” cultures would have a different intensity of maximization principle for the self but similar ideals for society. We reanalyzed their data to compare Latin American and Confucian societies and found that members of Latin American societies maximized qualities good for the self significantly more than members of Confucian societies, although members of societies in both regions maximized qualities good for society to a similar extent (see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material). Thus, people idealize higher levels of personal freedom or self-esteem in Latin American than in Confucian societies, which is consistent with our finding that Latin American cultural contexts foster independent selfhoods.

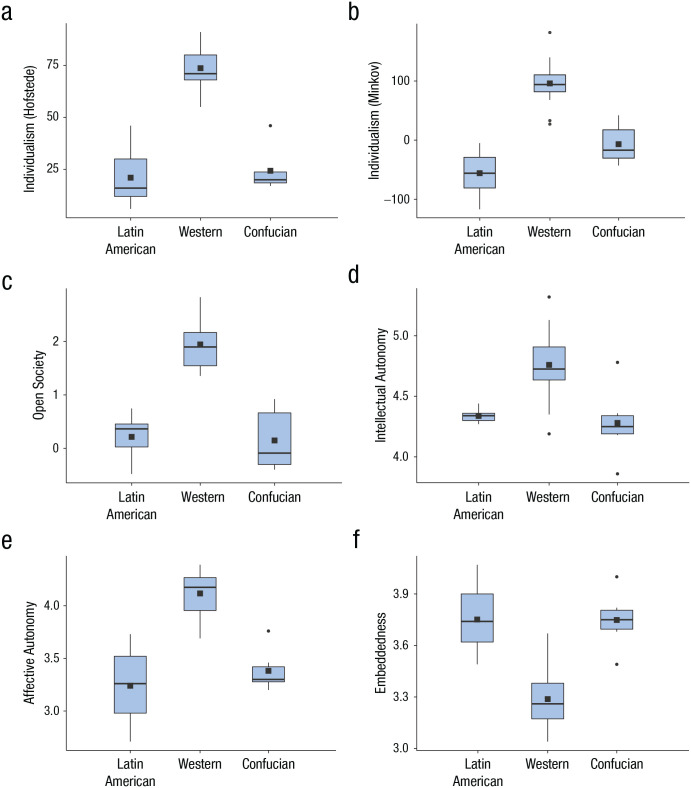

Is Latin America collectivistic?

Considering the long list of differences described above, readers might be forgiven for wondering by now whether Latin American cultures are simply not as collectivist as Confucian cultures or whether they have recently become individualistic. If one understands independence–interdependence and individualism–collectivism as synonymous, this might seem the only tenable conclusion. However, our review of cultural dimensions showed that the cultural values of Latin American societies remain at least as collectivist as those of Confucian Asian societies; moreover, both regions show a marked contrast with Western samples. As shown in Figure 5 and Table S6 in the Supplemental Material, we found this pattern in Hofstede’s (2017) index of individualist values and in Minkov and colleagues’ (2017) updated index. On the culture-level value dimension of autonomy versus embeddedness (Schwartz, 2008)—closely related to individualism–collectivism (see Gheorghiu et al., 2009)—both Latin American and Confucian Asian samples show a lower emphasis on autonomy and higher emphasis on embeddedness than Western samples. On open-society attitudes—a facet of individualism measured using the World Values Survey (Krys, Uchida, et al., 2019)—Latin America does not differ from Confucian Asia, whereas both regions rank lower than Western societies. Thus, Latin American and Confucian cultures are similarly characterized by collectivist values, distinct from Western cultures, even if they differ on numerous other dimensions.

Fig. 5.

A comparison of data from Latin American societies, Confucian Asian societies, and societies of Northwestern European (“Western”) heritage across six indicators of individualist versus collectivist cultural values. For each dimension, the box shows the interquartile range (IQR), the horizontal bar indicates the median, the square shows the mean, the whiskers go out to the most extreme data points that fall within 1.5× the IQR below the 25th percentile and above the 75th percentile, and the circles indicate observed values that fall outside this range (i.e., outliers). The plot shows that Latin American and Confucian East Asian societies share relatively collectivist values compared with Western societies. For further details and tests of statistical significance, see Supplement S4 and Table S6 in the Supplemental Material.

These findings document that members of Latin American societies have endorsed relatively collectivistic values for at least 5 decades: Hofstede’s (2017) indices were based on data collected around 50 years ago, Schwartz’s (2008) autonomy and embeddedness scores were based on data collected in the 1990s and early 2000s, Krys and colleagues’ open-society scores were based on data collected up to 2014, and Minkov and colleagues’ (2017) scores were based on data collected from 2014 to 2016. Interestingly, in the most recent data set (Minkov et al., 2017), Latin American cultures on average were even more collectivistic than Confucian Asian cultures (Fig. 4; also see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material).

The continuing prevalence of collectivist values in Latin America is consistent with theorizing that cultural collectivism arises in response to threatening socioecological contexts. Compared with Western societies, Latin American and Confucian societies on average have experienced higher historical pathogen prevalence (Murray & Schaller, 2010), higher environmental threats (Thomson et al., 2018), and lower socioeconomic development (for details, see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material). Interestingly, over the past 50 years Confucian Asian countries have approximately caught up with Western countries in socioeconomic development, which is not the case in Latin America. This raises questions about the cultural variability in pathways of socioeconomic development (see Krys et al., 2020) and how they relate to individualism (cf. Inglehart & Oyserman, 2004).

Possible Objections and Future Directions

Before drawing a firm conclusion that Latin American societies foster collectivist values and independent forms of selfhood, it is important to acknowledge and address several possible objections, many of which highlight a need for future studies.

Is this enough evidence?

Our analysis of self-construal data was based on four empirical studies whose results were already known when we planned our quantitative synthesis. Future research would be desirable to corroborate our findings. Nonetheless, these four studies were not cherry-picked from a larger literature—they include all the published data we could find comparing self-construals in Latin American and Confucian Asian societies, comprising data from 17,255 student and adult members of 104 study samples from 53 nations. Although we were aware of certain patterns of findings when planning our quantitative synthesis, the analyses reported here were conducted afterward. The findings are strikingly consistent across these four large-scale studies that were independently conducted by different teams of researchers for different original purposes. Moreover, we showed that these findings are coherent with theories and evidence from a range of other sources, including socioecological and historical perspectives, patterns of societal organization, and contemporary cross-cultural differences on related dimensions. Furthermore, initial results from subsequent studies have continued to show a similar pattern (e.g., Krys, Park, et al., 2021; Yang, 2018).

Are explicit self-reports valid?

Implicit ways of being independent or interdependent may not necessarily coincide with explicit construals of oneself as independent or interdependent that we analyzed here (Kitayama et al., 2009). Latin Americans might potentially think, feel, and act in implicitly interdependent ways but still perceive themselves as highly independent. Published research into implicit independence and interdependence has focused to date on Anglo American, East Asian, European, and Middle Eastern but not Latin American cultural contexts (Kitayama et al., 2009; San Martin et al., 2018). Nevertheless, a recent unpublished study by Salvador et al. (2020) provides initial evidence for tendencies toward independence in measures of the bases of happiness, affective preferences, symbolic self-inflation, and emotional experiences, but not in emotional expression or holistic cognition, among Colombian participants compared with U.S. and Japanese participants. Future research should explore cultural-level relationships between implicit and explicit ways of being independent and interdependent across a wider range of global regions.

Heine et al. (2002) argued that cultural comparisons of explicit self-reports can be undermined by reference-group effects, whereby participants contrast themselves against others in their local cultural context when answering rating scales—thus diluting the observed cultural differences. However, Vignoles et al. (2016) designed their measure to reduce reference-group effects. Even if a reference-group effect were involved in the high self-reported independence among Latin American samples, this would still mean that these participants tended to see themselves as more independent than their stereotype of a typical cultural member would suggest. Future studies should explore further the interplay between cultural stereotypes and self-perceptions.

Are the results context-specific?

The available data do not provide an indication of the possible scope of contextual variation in self-construals in each cultural sample. Although self-construals are often treated as trait-like constructs, priming studies have shown that they are amenable to experimental manipulation (Oyserman & Lee, 2008; Yang & Vignoles, 2020). Thus, Latin Americans may wish to act, and present themselves, as highly independent individuals in certain situations (e.g., with friends), whereas in others (e.g., among family members) they may behave much less independently. The image people build of themselves and the resultant self-construal they report when responding to a research questionnaire may be biased toward, or based on, certain types of situations. Future research could explore this further.

Are these cultural regions homogeneous?

Our grouping of cultures into broad categories of Latin American, Confucian Asian, and Northwestern European heritage assumes that countries in each of these three groups share similar historical, geographical, and cultural backgrounds to a meaningful extent, but we emphatically do not expect these groups of countries to be culturally homogeneous. Cultural systems of Mexico and Argentina or those of Japan and Taiwan differ on numerous characteristics, including those analyzed here (see Fig. 2). We especially do not want to replace oversimplified binary thinking about cultures (see Vignoles, 2018) with a similarly oversimplified cultural trichotomy. Such heuristics can help to guide sampling of populations for cross-cultural research, but they are no substitute for carefully measuring the cultural characteristics of interest. Future studies should provide a more fine-grained picture of the antecedents and consequences of cultural variation in models of selfhood.

Were Latin American forms of interdependence left unmeasured?

In comparing cultural samples from different world regions, we necessarily adopted an etic approach—comparing broad characteristics across cultures—rather than an emic approach—examining a single culture in depth (Berry, 1989; Van de Vijver, 2010). An etic approach inevitably cannot capture the full richness and complexity of a specific cultural system because it focuses only on aspects that are comparable across cultures. Nonetheless, cross-cultural validity of etic approaches can be improved to the extent that they draw on emic input from the cultures being compared (i.e., derived etic) rather than being driven from a single dominant cultural perspective (i.e., imposed etic; see Berry, 1989). Hence, an important question is to what extent the measures of self-construal compared here were sufficiently informed by emic input to capture Latin American models of selfhood.

Markus and Kitayama’s (1991) initial theorizing on self-construals was developed by a U.S. scholar and a Japanese scholar and drew mainly on evidence from Western and East Asian regions rather than Latin America. Singelis (1994) based his self-construal scale on Markus and Kitayama’s theorizing as well as previous scales developed in the same two cultural regions. He factor-analyzed data from two mixed ethnic samples, not including Latin American ethnicities, in one location (Hawaii) and validated the measure partly on the basis of its ability to differentiate Asian Americans from White Americans. In contrast, the seven-dimensional factor structure of the Vignoles et al. (2016) measure was based initially on data from 16 nations, three of which were Latin American, and validated in 55 cultural samples, of which 10 were Latin American or of Latin American heritage. Using this measure, we found that in one domain (making decisions) Latin American samples on average were significantly more interdependent (receptive to influence) than Western samples and nonsignificantly more so than Confucian Asian samples. Thus, the measure’s derived etic origins helped to capture nuanced ways of being independent or interdependent rather than forcing kaleidoscopic variation into imposed etic monolithic constructs of independence and interdependence. Nevertheless, the content of this measure was still largely derived from an East–West literature, originating in Markus and Kitayama’s (1991) theorizing, and we emphasize the need for more emic research into models of selfhood in underrepresented world regions—including Latin America—to inform development of future measures.

Is collectivism a useful construct?

Readers might object to our reliance on four measures of cultural values, triangulated with national indices of socioecological threat, to characterize Latin American and Confucian Asian cultures as collectivist. Whereas the term “individualist” tends to be reserved for a relatively narrow group of contemporary developed so-called Western societies, researchers often seem to use “collectivist” as an umbrella term covering all past and present societies that are not individualist—however diverse they are and however different their histories. Indeed, an important goal of our article is to point out that the term “collectivism” disguises a huge amount of cultural diversity. The ambiguity of collectivism can be seen through the diverse range of item contents used to measure it (e.g., Hofstede, 2001; Minkov et al., 2017; Schwartz, 2006), as well as the proliferation of diverse “forms,” “facets,” or “subtypes” of collectivism proposed by cross-cultural researchers (e.g., Brewer & Chen, 2007; Kim, 1994; Oyserman et al., 2002; Realo et al., 1997; Singelis et al., 1995; for further discussion, see Section S5 in the Supplemental Material).

We believe that there is an urgent need for a concerted and systematic effort to measure and explore at a cultural level of analysis the relations among these various proposed forms or facets of collectivism. Only when the culture-level dimensionality of collectivism is better understood will it be possible to name these constructs and theorize about them more precisely—as well as to identify conceptual boundaries for the constructs of individualism and collectivism. In the absence of such work, these concepts risk becoming too slippery for theoretical claims to be falsifiable (Vignoles, 2018). Our interim solution here was to focus on individualist and collectivist values, as measured by Hofstede (2001), Schwartz (2006), Krys, Uchida, et al. (2019), and Minkov et al. (2017).

What additional factors might be involved?

In seeking to explain Latin American models of selfhood, we focused on contextual, societal, and psychological factors that were identified in previous cross-cultural research. We felt it was important to ground our explanations as much as possible in existing theorizing, and we believe this helped us to show that the prevalence of independent models of selfhood in Latin America is consistent with broader patterns of global cultural variation rather than being an anomaly. Nevertheless, existing literature in cross-cultural psychology has been shaped especially by attempting to explain differences between Western and East Asian cultures, and so our account may be missing additional factors that are less salient or relevant in those two regions. We highlight two areas for further theorizing.

First, we looked at contemporary patterns of subsistence as well as religion, but it may be valuable to take a longer historical view of how these patterns developed in Latin American societies. Before colonization, Latin American peoples lived in societies with widely differing religious beliefs and modes of subsistence—ranging from small hunter-gatherer groups to highly developed Inca and Aztec civilizations. Indigenous religions, together with those that were brought in by enslaved Africans, often became merged or hybridized with the imported Catholic belief system of settlers and missionaries. The implications of these preexisting indigenous American and African belief systems for forms of selfhood have yet to be explored in depth (for Asian belief systems, see Ho, 1995). Pre-Columbian civilizations in Latin America cultivated corn, beans, squash, potatoes, or manioc depending on the region, and sugar cane and tobacco cultivation were extensively developed during the colonial era. Existing research into the impact of crop production on culture has focused on two crops—rice and wheat—that are prevalent in China today (Talhelm et al., 2014), and so it could be valuable to extend theorizing and research to consider the possible impact on culture of a wider range of historical and contemporary modes of subsistence.

Second, comparisons of Western and East Asian cultures have usually focused on societies with relatively stable political systems. By contrast, Latin American societies since independence have often experienced political instability, lawlessness, and dictatorships (see, e.g., Blanco & Grier, 2009), as well as high levels of income inequality (Gasparini & Nora, 2011). Although we are aware of no previous work linking political instability to cultural models of selfhood, it seems plausible that certain forms of independence—for example, self-reliance and self-interest—would be adaptive in relatively unstable societies in which one is less able to rely on the cooperation of others. Some research has linked both political violence and perceived economic inequality to forms of independent self-construal at an individual level of analysis (Khan & Smith, 2003; Sánchez-Rodríguez et al., 2019), suggesting important areas for future research.

Implications

Latin American societies have been associated theoretically with honor logic and characterized empirically by geographically mobile modes of subsistence, a history of voluntary settlement, ethnic heterogeneity, Christianity, high relational mobility, loose norms, monumental selves, indulgence and emotional expressivity, high desired and perceived control, and high endorsement of the maximization principle for self-desired outcomes—features that may explain their relative emphasis on independent forms of selfhood. Yet these societies continue to emphasize collectivist cultural values. Thus, we find it reasonable to conclude that collectivist cultures, in certain conditions, may foster independent self-construals. This novel conclusion carries important implications for extending theory and research on culture and the self. We believe it also carries a broader message for psychological scientists about the importance of being willing to learn from their data.

Extending the cross-cultural database

First, future studies urgently need to pay more attention to a wider range of cultural contexts. Psychological-research participants still mostly come from individualist countries, especially WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) societies (Henrich et al., 2010). Even in studies of major cross-cultural research topics, the remaining samples come mostly from China, Japan, and Korea (Fig. 1; also see Section S6 in the Supplemental Material). Because researchers often assume that all collectivist cultures foster a similar model of selfhood, such an unbalanced data corpus may lead to overgeneralizing theories and conclusions from Confucian East Asia to other “non-Western” contexts. For example, researchers sometimes imply that replication of a Western finding in one or more Confucian collectivist cultures provides evidence of universality (e.g., Yamaguchi et al., 2007; cf. Norenzayan & Heine, 2005). Our findings illustrate the risks of generalizing conclusions from one country to another on the basis of a single cultural characteristic such as collectivist values. Instead, more attention needs to be given to regions that are currently underrepresented in cross-cultural studies: The psychologies of cultural groups living in Africa, Eastern Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, or South Asia should be understood using finer-grained theories and measures that more accurately describe their socioecological contexts, values, and models of selfhood (e.g., Inglehart & Baker, 2000; Schwartz, 2006; Vignoles et al., 2016).

Extending the theoretical tool kit

A second implication is that oversimplified and excessively broad understandings of individualism versus collectivism and independence versus interdependence need revising. African, Middle Eastern, or South Asian societies, even if they share collectivist value priorities, may be regulated by different processes from those of the more extensively studied Confucian forms of collectivism. A more accurate understanding of these processes may be inhibited by the prevailing binary thinking about cultures (Vignoles, 2018). To redress this thinking, “anomalous” empirical results need careful theoretical attention rather than being explained away as likely artifacts of methodology or sampling (which is not to say that methodological guidelines should be ignored either). Such findings may provide valuable new insights into the functioning of diverse societies, which could inspire new theorizing.

Relatedly, cross-cultural researchers should work on “translating” the psychological implications of cultural dimensions beyond individualism–collectivism (e.g., power distance, harmony-mastery, tightness-looseness, monumentalism-flexibility, and many others) for use by mainstream psychologists. Independent and interdependent self-construals were initially theorized to help understand the psychological implications of Western and Confucian cultures (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Researchers have begun to disentangle forms of independence and interdependence (e.g., Vignoles et al., 2016), but the contents of this research domain are still shaped by the original focus on the East–West comparison. Exploring a wider range of cultural contexts and macrocultural dimensions may help reveal many further important dimensions on which cultural models of selfhood vary.

Learning from our participants

We believe that our article carries an important cautionary message for the wider community of psychological scientists about the risks of theoretical dogma and the devaluing of exploratory research. Rather than adopting the classic hypothetico-deductive narrative form of a standard psychology article, we have tried here to describe as transparently as possible our “journey” as researchers from believing the common view that individualism–collectivism and independence–interdependence were largely synonymous toward trusting the message we received from thousands of research participants that this was not the case and ultimately toward making sense of these new and unexpected findings.

With the benefit of hindsight, it now seems obvious to us that Latin American cultures would foster independent forms of self-construal, and perhaps we could have written our article as if we had predicted this from the start. But we did not predict it. Hypothesizing after the results are known is intellectually dishonest and distorts statistical findings (Kerr, 1998). Yet restricting ourselves to reporting only what was hypothesized in advance and tested using a predetermined analysis plan risks reducing the capacity of psychological scientists to learn new insights from our participants—to make scientific discoveries. Thus, we believe that adopting best practices in theory-testing research can help the advancement of psychological science only to the extent that this is accompanied by an equally strong parallel movement toward openly reporting and valuing exploratory and theory-building research.

Concluding Remarks

We have argued that the prevailing understanding of collectivism urgently needs revision and that diversity among collectivist societies must be recognized. In particular, we theorized that some collectivist societies foster independent self-construals. The evidence supporting this claim is not new—it has been “hiding in plain sight” within the literature for several years, but successive findings seemingly have been discounted because of a strongly held theoretical assumption that collectivist cultural values must by definition be associated with interdependent self-construals. We hope that the ideas and findings presented here will help unlock discussion about non-Confucian forms of collectivism and that data incongruent with previous theorizing will be recognized as potentially inspirational rather than faulty. Furthermore, we hope that our arguments will reopen discussion about how dimensions of cultural context should be translated into individual-level psychological theorizing. Individualism–collectivism is just one of many cultural dimensions likely to influence cultural members’ self-conceptions, as well as their cognitions, emotions, motivations, and behaviors. Finally, we wish to add our voice to calls for greater attention to regions that are currently underrepresented in cross-cultural studies—Africa, Eastern Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, and South Asia (Kim et al., 2006). People in all world regions deserve a cross-cultural psychology that is informed by, and helps to explain, social and psychological processes in their local cultural contexts.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pps-10.1177_17456916211029632 for Outside the “Cultural Binary”: Understanding Why Latin American Collectivist Societies Foster Independent Selves by Kuba Krys, Vivian L. Vignoles, Igor de Almeida and Yukiko Uchida in Perspectives on Psychological Science

Acknowledgments

We thank Colin A. Capaldi, John M. Zelenski, Jerzy Karylowski, and Eunkook Mark Suh for their comments and Alethea Koh for her support. All data and materials have been made publicly available via OSF and can be accessed at https://osf.io/p674z/

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Kuba Krys  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0365-423X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0365-423X

Igor de Almeida  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4599-0442

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4599-0442

Yukiko Uchida  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8336-2423

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8336-2423

Supplemental Material: Additional supporting information can be found at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/17456916211029632

Transparency

Action Editor: Laura A. King

Editor: Laura A. King

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared that there were no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship or the publication of this article.

Funding: This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grants P17806 and 17F17806 and Polish National Science Centre Grant 2016/23/D/HS6/02946.

References

- Berry J. W. (1989). Imposed etics-emics-derived etics: The operationalization of a compelling idea. International Journal of Psychology, 24, 721–735. 10.1080/00207598908247841 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco L., Grier R. (2009). Long Live Democracy: The determinants of political instability in Latin America. The Journal of Development Studies, 45, 76–95. 10.1080/00220380802264788 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer M. B., Chen Y.-R. (2007). Where (who) are collectives in collectivism? Toward conceptual clarification of individualism and collectivism. Psychological Review, 114, 133–151. 10.1037/0033-295X.114.1.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church A., Katigbak M., Locke K., Zhang H., Shen J., de Jesús Vargas-Flores J., Ibáñez-Reyes J., Tanaka-Matsumi J., Curtis G. J., Cabrera H. F., Mastor K. A., Alvarez J. M., Ortiz F. A., Simon J.-Y. R., Ching C. M. (2013). Need satisfaction and well-being: Testing self-determination theory in eight cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 507–534. 10.1177/0022022112466590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A. B. (2015). Religion’s profound influences on psychology: Morality, intergroup relations, self-construal, and enculturation. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(1), 77–82. 10.1177/0963721414553265 [DOI]

- De Almeida I., Uchida Y. (2018). Examining affective valence in Japanese and Brazilian cultural products: An analysis on emotional words in song lyrics and news articles. Psychologia, 61, 174–184. 10.2117/psysoc.2019-A103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Effron D., Markus H., Jackman L., Muramoto Y., Muluk H. (2018). Hypocrisy and culture: Failing to practice what you preach receives harsher interpersonal reactions in independent (vs. interdependent) cultures. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 371–384. 10.1016/j.jesp.2017.12.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J., Ren X., Ma X. (2017). Ongoing voluntary settlement and independent agency: Evidence from China. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 1287. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fernandez I., Paez D., González J. (2005). Independent and interdependent self-construals and socio-cultural factors in 29 nations. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale, 18, 35–63. [Google Scholar]

- Garza R. (1978). Affective and associative qualities in the learning styles of Chicanos and Anglos. Psychology in the Schools, 15, 111–115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini L., Nora L. (2011). The rise and fall of income inequality in Latin America. In Antonio J., Ocampo, Ros J. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of Latin American economics (pp. 691–714). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand M. J., Raver J. L., Nishii L., Leslie L. M., Lun J., Lim B. C., Duan L., Almaliach A., Ang S., Arnadottir J., Aycan Z., Boehnke K., Boski P., Cabecinhas R., Chan D., Chhokar J., D’Amato A., Ferrer M., Fischlmayr I. C., . . . Yamaguchi S. (2011). Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science, 332, 1100–1104. 10.1126/science.1197754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheorghiu M. A., Vignoles V. L., Smith P. B. (2009). Beyond the United States and Japan: Testing Yamagishi’s emancipation theory of trust across 31 nations. Social Psychology Quarterly, 72, 365–383. 10.1177/019027250907200408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haase C., Heckhausen J., Köller O. (2009). Goal engagement in the school-to-work transition: Beneficial for all, particularly for girls. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 671–698. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00576.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heine S. J., Lehman D. R., Peng K., Greenholtz J. (2002). What’s wrong with cross-cultural comparisons of subjective Likert scales? The reference-group effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 903–918. 10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J. (2020). The weirdest people in the world: How the west became psychologically peculiar and particularly prosperous. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J., Heine S., Norenzayan A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 61–83. 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans H. J., Kempen H. J. (1998). Moving cultures: The perilous problems of cultural dichotomies in a globalizing society. American Psychologist, 53, 1111–1120. 10.1037/0003-066X.53.10.1111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho D. Y. (1995). Selfhood and identity in Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, and Hinduism: Contrasts with the West. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 25(2), 115–139. 10.1111/j.1468-5914.1995.tb00269.x [DOI]

- Hofstede G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work related values. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. (2017, August 18). Dimension data matrix [Data set]. https://geerthofstede.com/research-and-vsm/dimension-data-matrix

- Hofstede G., Hofstede G., Minkov M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hornsey M., Bain P., Harris E., Lebedeva N., Kashima E., Guan Y., González R., Chen S., Blumen S. (2018). How much is enough in a perfect world? Cultural variation in ideal levels of happiness, pleasure, freedom, health, self-esteem, longevity, and intelligence. Psychological Science, 29, 1393–1404. 10.1177/0956797618768058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornsey M., Greenaway K., Harris E., Bain P. (2019). Exploring cultural differences in the extent to which people perceive and desire control. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45, 81–92. 10.1177/0146167218780692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui C., Triandis H. (1986). Individualism–collectivism: A study of cross-cultural researchers. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 17, 225–248. 10.1177/0022002186017002006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart R., Baker W. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 65, 19–51. 10.2307/2657288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart R., Oyserman D. (2004). Individualism, autonomy, self-expression. The human development syndrome. In Vinken H., Soeters J., Ester P. (Eds.), Comparing cultures, dimensions of culture in a comparative perspective (pp. 74–96). Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii K., Kitayama S., Uchida Y. (2014). Voluntary settlement and its consequences on predictors of happiness: The influence of initial cultural context. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, Article 1311. 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Johnson B., Eagly A. (2000). Quantitative synthesis of social psychological research. In Reis H., Judd C. (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 496–528). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kashima Y., Koval P., Kashima E. S. (2011). Reconsidering culture and self. Psychological Studies, 56, 12–22. 10.1007/s12646-011-0071-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr N. L. (1998). HARKing: Hypothesizing after the results are known. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2, 196–217. 10.1207/s15327957pspr0203_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan N., Smith P. B. (2003). Profiling the politically violent in Pakistan: Self-construals and values. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 9, 277–295. 10.1207/s15327949pac0903_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim U. (1994). Individualism and collectivism: Conceptual clarification and elaboration. In Kim U., Triandis H. C., Kâgitçibasi Ç., Choi S. C., Yoon G. (Eds.), Individualism and collectivism: Theory, method, and applications (pp. 19–40). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Kim U., Yang K.-S., Hwang K.-K. (Eds.). (2006). Indigenous and cultural psychology: Understanding people in context. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S., Ishii K., Imada T., Takemura K., Ramaswamy J. (2006). Voluntary settlement and the spirit of independence: Evidence from Japan’s “northern frontier.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 369–384. 10.1037/0022-3514.91.3.369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S., Park H., Sevincer A. T., Karasawa M., Uskul A. K. (2009). A cultural task analysis of implicit independence: Comparing North America, Western Europe, and East Asia. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 236–255. 10.1037/a0015999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S., Uskul A. K. (2011). Culture, mind, and the brain: Current evidence and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 419–449. 10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krys K., Capaldi C. A., Lun V. M.-C., Vauclair C.-M., Bond M. H., Dominguez-Espinosa A., Uchida Y. (2020). Psychologizing indexes of societal progress: Accounting for cultural diversity in preferred developmental pathways. Culture & Psychology, 26, 303–319. 10.1177/1354067X19868146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krys K., Park J., Kocimska-Zych A., Kosiarczyk A., Selim H. A., Wojtczuk-Turek A., Haas B. W., Uchida Y., Torres C., Capaldi C. A., Bond M. H., Zelenski J. M., Lun V. M.-C., Maricchiolo F., Vauclair C.-M., Šolcová I. P., Sirlopú D., Xing C., Vignoles V. L., . . . Adamovic M. (2021). Personal life satisfaction as a measure of societal happiness is an individualistic presumption: Evidence from fifty countries. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22, 2197–2214. 10.1007/s10902-020-00311-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]