Abstract

Background

Delayed-onset carpal tunnel syndrome (DCTS) can develop weeks and months after distal radius fracture (DRFx). A better understanding of the risk factors of DCTS can guide surgeon’s decision making regarding the management of DRFx and also provides another discussion point to be had with elderly patients when discussing outcomes of nonoperative management.

Methods

We reviewed 216 nonoperatively managed DRFx between June 2015 and January 2019 at a single level 1 trauma center and senior author’s office. We identified 26 patients who developed DCTS at a minimum of 6 weeks after DRFx, which constituted our case group. The remaining 190 patients served as the control group (non–carpal tunnel syndrome [CTS]). Differences between case and control group were evaluated through univariate and multivariate analyses.

Results

The prevalence of DCTS among nonoperatively managed DRFx was 12%. In univariate analysis, volar tilt (VT) and teardrop angle (TDA) were significant independent predictors of development of DCTS. Multivariate logistic regression analysis determined that the odds of developing CTS increased by 12% and 24% for each degree of decrease in VT and TDA, respectively. No other significant risk factors were identified.

Conclusions

Decreasing VT and TDA are the most significant risk factors associated with DCTS in nonoperatively managed DRFx. These are simple and reliable radiographic measurements that provide significant prognostic value. These parameters can be used to guide surgeon decision making regarding management of DRFx in the elderly while aiding patient expectations and outcomes following nonoperative management of DRFx.

Keywords: nerve, basic science, distal radius, fracture/dislocation, diagnosis, wrist, carpal tunnel syndrome, nerve compression, trauma, evaluation, research and health outcomes

Introduction

Distal radius fractures (DRFx) are the most common fractures seen in the emergency department; they represent approximately 3% of all upper extremity injuries, with an incidence greater than 640 000 annually in the United States alone. 1 Over the past 50 to 60 years, the understanding of DRFx has evolved dramatically, leading to the development of various operative modalities and techniques. Despite these advances, nonoperative management continues to be the mainstay of treatment for DRFx in the elderly, with an estimated 70% of cases managed in this way.1,2

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a major complication following DRFx and can be classified as acute, subacute, and delayed. Acute CTS occurs at the time of injury, whereas subacute CTS develops several weeks after injury. Delayed-onset CTS (DCTS) occurs months to years following the initial injury. 3 Several studies have identified risk factors for developing acute CTS after DRFx3-5; however, the cause of DCTS after DRFx remains unclear. There is currently a paucity of literature devoted to this focus, and much of the available literature is inconclusive and conflicting. In general, malunion of the distal radius is thought to be a major predisposing factor to DCTS.3,6-10 There is no formal definition of distal radius malunion, but it is generally understood as radial inclination <10°, volar tilt (VT) > 20°, dorsal tilt > 20°, radial height < 10 mm, ulnar variance > 2+, and intra-articular step or gap > 2 mm. 8

The purpose of this study was to evaluate age, sex, medical comorbidities, and radiographic parameters as potential risk factors for the development of DCTS following nonoperatively managed DRFx. We defined DCTS as development of symptoms 6 weeks after injury. Our null hypothesis was that no risk factor would predict the development of DCTS.

Materials and Methods

Billing databases at an academic level 1 trauma center and a private orthopedic office were retrospectively reviewed in compliance and after approval by the local institutional review board. A total of 247 nonoperatively managed DRFx were identified between June 2015 and January 2019. Electronic medical records were then reviewed to gather the following information: treatment modality, age, sex, occupation, and medical comorbidities, such as diabetes, renal disease, hypothyroidism, history of cancer, associated injuries, prior CTS symptoms, time of CTS diagnosis, and radiographic measurements. Patients were excluded if they underwent surgically treated DRFx (either initial or delayed operative management of DRFx), age <60, acute/subacute (0-6 weeks) onset of CTS, <6 months of follow-up, inadequate follow-up imaging (minimal 2 orthogonal views of the affected wrist), prior history of CTS, and polytrauma patients. After application of exclusion criteria, a total of 216 patients remained. The diagnosis of CTS was made using the 6-item CTS symptom scale (CTS-6) screening tool as described by Graham et al.11,12 Patients who met the criteria for CTS were assigned to the CTS (cases) group, and the remainder were assigned to the control group.

Initially, manipulation of fracture with local hematoma block was performed for displaced DRFx (dorsal angulation >5°, radial shortening >5 mm) before splinting, whereas nondisplaced DRFx were managed by application of sugar-tong splint. Sugar-tong splints were converted to below-elbow casts at week 1 or 2. Below-elbow casts were converted to removable braces at week 4, which the patients were allowed to remove for range of motion exercises. At week 6, removable braces were discontinued, and occupational therapy was initiated. Follow-up evaluation with radiographs of the affected wrist was taken at 2-week intervals for up to 6 weeks and then at 3 and 6 months or time of onset of CTS.

Radiological Assessment

Radiological parameters were measured using posterioanterior (PA) and lateral radiographs at the time of onset for the CTS group and after radiographic union was achieved for the control group. Measured parameters included radial inclination and ulnar variance on the PA view, whereas VT and teardrop angle (TDA) were measured on the lateral view. These measurements were performed using the method described by Medoff.13,14

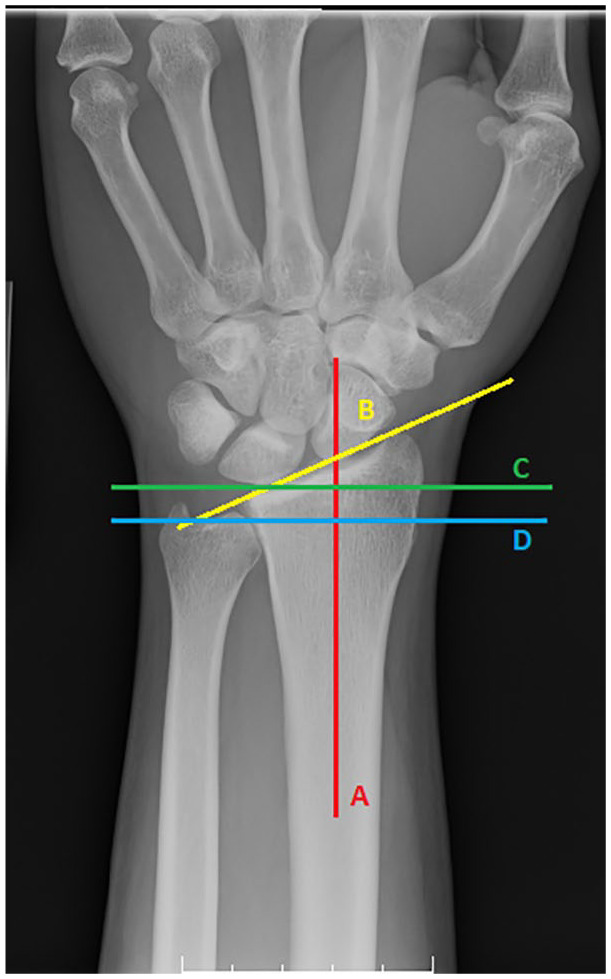

Radial inclination was measured as the angle between a line drawn from the tip of the radial styloid to the central reference point (CRP). CRP is defined as the center of dorsal ulnar and volar ulnar corners of the sigmoid notch of distal radius on the PA view and a line that is perpendicular to the long axis of the radial shaft, with the average measurement being 24° (Figure 1).13,14

Figure 1.

Posterioanterior view of wrist.

Note. Radial inclination—Angle between a line drawn from the tip of the radial styloid to the central reference point (B) and a line that is perpendicular (C) to the long axis of the radial shaft (A). Ulnar variance—Distance between 2 lines drawn perpendicular to a reference line extended along the axis of the radial shaft (A). One perpendicular line intersects the central reference point (C) and the other perpendicular line intersects the distal edge (D) of the ulnar head.

Ulnar variance was determined by measuring the distance between 2 lines drawn perpendicular to a reference line extended along the axis of the radial shaft where 1 perpendicular line intersects the distal edge of the ulnar head and the second perpendicular line intersects the CRP, normally −0.6 mm (Figure 1).13,14

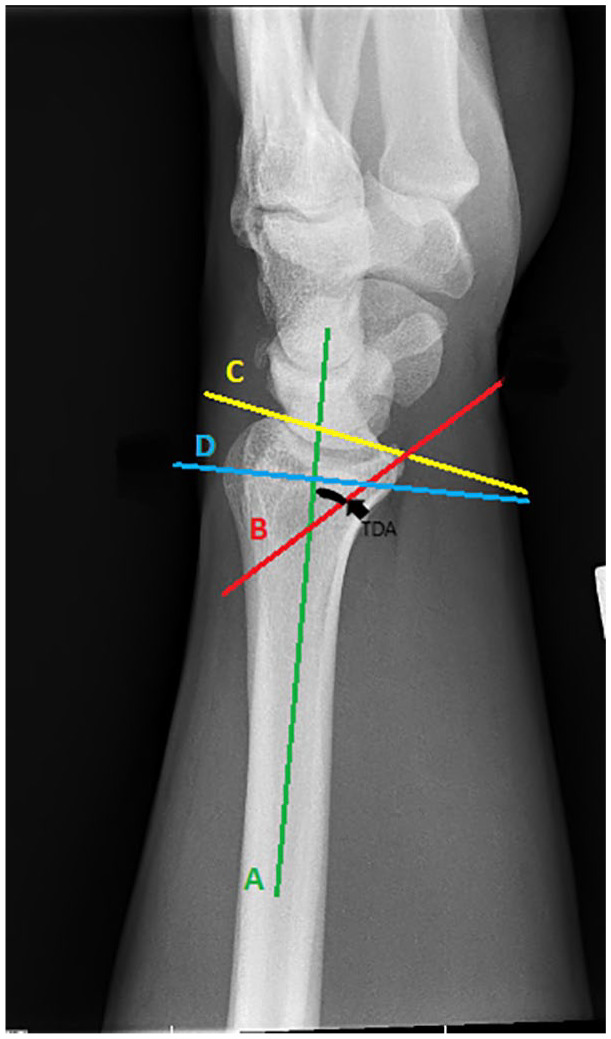

Volar tilt was defined as the angle between a line perpendicular to the central axis of the radial shaft and a line that connects the corner of the dorsal rim and the corner of the volar rim on the lateral view. Normal wrists have about 10° VT (Figure 2).13,14

Figure 2.

Lateral view of wrist.

Note. Teardrop angle—Angle between a line extended along the longitudinal axis of the radial shaft (A) and a line that is drawn down the center of the teardrop (B). Volar tilt—Angle between a line perpendicular to the central axis (D) of the radial shaft (A) and a line that connects the corner of the dorsal rim and the corner of the volar rim of distal radius (C).

The TDA is determined by measuring the angle between a line extended along the longitudinal axis of the radial shaft and a line that is drawn down the center of the teardrop; the teardrop is the U-shaped outline of the volar rim of the lunate facet. If the complete cortical outline of the teardrop is difficult to determine, a line drawn parallel to the subchondral bone of the volar rim was used instead, with the average measurement being 70° (Figure 2).13,14

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations. Categorical variables were presented using frequencies and percentages. Characteristics of the CTS and non-CTS groups were compared using Student t test for normally distributed variables and Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric variables. The χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables. To investigate factors associated with the development of CTS following DRFx, multivariate logistic regression was used. Variables that were found to be independently associated with the development of CTS were adjusted for in the multivariate regression model. Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to evaluate the fit of the adjusted model. The 2-sided level of significance was 5% (P < .05). Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

After application of exclusion criteria, the study evaluated a total of 216 patients. Twenty-six patients (12.0%) developed DCTS, and 190 (88%) did not develop CTS. Patient demographic and radiological parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Radiology Parameters of the Study Sample.

| Variable | All (N = 216) | CTS (n = 26) | No CTS (n = 190) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 73.8 ± 8.0 | 71.6 ± 9.4 | 74.1 ± 7.8 | .1506 |

| Sex | .1259 | |||

| Male | 70 (32.4%) | 5 (19.2%) | 65 (34.2%) | |

| Female | 146 (67.6%) | 21 (80.8%) | 125 (65.8%) | |

| Radial inclination | 17.9° ± 5.0° | 17.3° ± 6.2° | 17.9° ± 4.8° | .5569 |

| Ulnar variance | 0.2° ± 0.9° | 0.2° ± 0.7° | 0.2° ± 1.0° | .6994 |

| Volar tilt a | −1.2° ± 9.2° | −11.1° ± 8.1° | 0.1° ± 8.5° | <.0001** |

| Dorsal | 114 (52.8%) | 21 (80.8%) | 93 (48.9%) | |

| Neutral | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Volar | 101 (46.8%) | 5 (19.2%) | 96 (50.5%) | |

| Teardrop angle | 61.3° ± 8.2° | 48.7° ± 6.9° | 63.0° ± 6.8° | <.0001 |

Note. CTS = carpal tunnel syndrome.

Negative volar tilt = dorsal tilt.

P < .05.

Patients With CTS (Cases)

Among 26 patients, there were 21 women (80.8%) and 5 men (19.2%) with an average age of 71.6 ± 9.4 years (60-86 years), and 23 (88.5%) of 26 required manipulation. The average time to development of CTS was 89.9 days (38-166 days). The average radiographic parameters were as follows: radial inclination, 17.3° ± 6.2°; ulnar variance, 0.2° ± 0.7°; VT, −11.1° ± 8.1° (negative = dorsal); and TDA, 48.7° ± 6.9°. Dorsal tilt was observed in 21 (80.8%) patients, and VT was observed in 5 (19.2%) patients.

Patients Without CTS (Control)

Among 190 patients, there were 125 women (65.8%) and 65 men (34.2%) with an average age of 74.1 ± 7.8 years, and 171 (90%) of 190 required manipulation. The average radiographic parameters were as follows: radial inclination, 17.9° ± 4.8°; ulnar variance, 0.2° ± 1°; VT, 0.1° ± 8.5°; and TDA, 63° ± 6.8°. Dorsal tilt was observed in 93 (48.9%) patients, neutral in 1 (0.5%) patient, and VT in 96 (50.5%) patients.

Univariate Analysis

There were no significant differences between groups in terms of demographic factors (age, sex, medical comorbidities). Among the radiographic parameters, dorsal tilt was significantly higher in the CTS group compared with the non-CTS group (−11.1° ± 8.1° vs −0.1° ± 8.5°; P < .0001), whereas the TDA was significantly lower in patients who developed CTS compared with patients who did not (48.7° ± 6.9° vs 63.0° ± 6.8°; P < .0001). Only dorsal tilt and TDA were significant independent predictors of CTS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted Logistic Regression Analysis of Factors Predictive of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.963 | 0.915-1.014 | .1521 |

| Sex (female vs male) | 2.184 | 0.787-6.058 | .1335 |

| Radial inclination | 0.976 | 0.900-1.058 | .552 |

| Ulnar variance | 0.934 | 0.594-1.469 | .7683 |

| Volar tilt | 0.813 | 0.745-0.886 | <.0001** |

| Teardrop angle | 0.722 | 0.642-0.811 | <.0001 |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

P < .05.

Multivariate Analysis

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors predictive of CTS is presented in Table 3. For every degree decrease in VT angle, the odds of CTS were increased by 12% (odds ratio [OR]: 0.885, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.813-0.964; P = .0052). For every degree decrease in TDA, the odds of developing CTS were increased by 24% (OR: 0.763, 95% CI: 0.763-0.679; P < .0001).

Table 3.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Factors Predictive of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.97 | 0.898-1.047 | .4292 |

| Sex (female vs male) | 1.657 | 0.366-7.511 | .5122 |

| Volar tilt | 0.885 | 0.813-0.964 | .0052** |

| Teardrop angle | 0.763 | 0.763-0.679 | <.0001** |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

P < .05.

Discussion

Delayed-onset CTS is a well-described complication following nonoperative management of DRFx with a reported incidence of 0.5% to 22%.7,10,15-19 Factors thought to play a role in the development of DCTS include radiographic malunion, carpal instability, chronic inflammation, excess callus formation, prolonged immobilization in the cotton loader position, and other factors that alter the anatomy of the carpal tunnel.3,6-10,17,18,20-22 Despite multiple studies noting an association between malunion and the development of DCTS, there is a paucity of literature connecting specific radiographic parameters to the development of DCTS.3,6,9,15,17,18,20,21,23,24

In this study, we retrospectively reviewed 216 patients with nonoperatively managed DRFx with a primary focus on identifying radiographic parameters associated with the development of DCTS. The rate of DCTS in our cohort was 12% (26 of 216), which is consistent with the range of previously reported values.7,10,15-19 We found VT to be significantly lower in the DCTS group compared with the patients without DCTS (11.1° vs 0.1°). In addition, we found a decreased TDA to be significantly associated with the development of DCTS (48.7° vs 61.3°). Both VT and TDA were found to be independent predictors of CTS with univariate analysis. Based on multivariate logistic regression analysis, the odds of developing CTS increased by 12% and 24% for each decrease of 1° of VT and TDA, respectively. We found no significant difference between groups regarding ulnar variance, radial inclination, demographic factors, or medical comorbidities.

Many authors have speculated ideas between malalignment of DRFx and development of DCTS. Aro et al 7 reported an 8% incidence of late median nerve compression neuropathy in 166 nonoperatively managed DRFx and noted that 85% of the affected group had radial collapse. Itsubo et al 3 retrospectively reviewed 30 cases of DCTS and concluded that fracture malalignment leading to changes in the anatomical configuration of the carpal tunnel could be a predisposing factor for the development of DCTS. Stewart et al 10 evaluated a series of 235 patients with nonoperatively managed DRFx and reported a statistically significant difference in residual VT (−12.6° vs −7°) in patients who developed DCTS. Recently, Watanabe and Ota 9 reported that carpal malalignment, specifically dorsal displacement of capitate, resulting from malunion of the distal radius is a predictor of DCTS.

The teardrop is an important landmark that is often overlooked. The teardrop on the lateral radiographic projection of the distal radius can be simply understood as the volar aspect of the lunate facet. As described by Medoff, this angle is of little significance in extra-articular fractures, as it is directly proportional to VT given the continuity of the articular surface. With certain intra-articular fractures, however, this direct relationship is disrupted, and changes in VT and TDA may occur independently of one another. These fracture patterns typically result from higher energy injuries with an axial loading component, in which the lunate is driven into the lunate fossa splitting the articular surface into volar and dorsal fragments. The dorsal rim is rotated dorsally, which results in decreased TDA. Under these circumstances, the change in TDA is no longer directly related to the VT of the distal radius.14,25 This is an important concept for the clinicians to understand, and care should be taken to scrutinize TDA, as the volar rim may remain in a dorsiflexed position, which can lead to significant articular incongruity and carpal instability, even after restoration of VT by closed reduction (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Lateral view of pre/post-manipulation of intra-articular distal radius fracture.

Note. Lateral view of pre-manipulation of intra-articular distal radius fracture (a) demonstrating loss of volar tilt and decreased teardrop angle (TDA); and post-manipulation (b) demonstrating restoration of volar tilt to 6° with persistent decreased TDA of 54°.

As noted in prior studies, these residual changes from malunion of the distal radius can result in altered anatomy, cross-sectional area, and compartment pressure of the carpal tunnel,3,7-9,13,21,26,27 which has previously been shown to play a role in the development of DCTS. 28 This altered anatomy is thought to cause impingement and/or traction to the median nerve, which predisposes the affected individual to either de novo development of CTS or an exacerbation of preexisting subclinical median nerve compression neuropathy.3,21 The causal effect of malunion causing DCTS is further supported by Kwasny et al 21 and Megerle et al, 22 who report 12 of 13 and 30 of 30 respective cases of carpal tunnel, which improved with corrective osteotomy of malunited DRFx alone.

This study does have several weaknesses. First, this study is subject to limitations associated with its retrospective design. Second, the diagnosis of CTS was not confirmed with electrodiagnostic testing (EDT). As a result, the severity of CTS was unknown. However, CTS-6 has been shown to have both high validity and strong correlation with EDT when making diagnosis of CTS. 12 Third, this study was focused primarily on radiographic parameters on plain radiographs. As a result, we were unable to investigate the relationship between our radiographic findings and a change in the cross-sectional size/volume of the carpal tunnel.

Conclusion

In this study, incidence of DCTS with nonoperatively managed DRFx was 12%, which correlated with a reported incidence of 0.5% to 22%.7,10,15-19 We found that decreased VT and TDA were significant independent predictors of development of DCTS after DRFx malunion in the elderly. These results alone may not constitute a strong surgical indication, but they do provide an additional consideration for the treating surgeon regarding surgical decision making when managing DRFx in the elderly. They also provide information which can be used when counseling patients regarding expectations and outcomes following nonoperative management.

Acknowledgments

We thank Aimee Golightly, BS for her assistance with electronic medical record collection/review.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Statement of Informed Consent: This research is exempt from 45 CFR Part 46 and does not require informed consent.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Kevin H. Kim  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0593-004X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0593-004X

References

- 1. Wolfe SW, Pederson WC, Kozin SH, et al. Distal Radius Fractures: Green’s Operative Hand Surgery, 2-Volume Set. Vol. 1. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences Division; 2016:516-587. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chung KC, Shauver MJ, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in the United States in the treatment of distal radial fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(8):1868-1873. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Itsubo T, Hayashi M, Uchiyama S, et al. Differential onset patterns and causes of carpal tunnel syndrome after distal radius fracture: a retrospective study of 105 wrists. J Orthop Sci. 2010;15(4):518-523. doi: 10.1007/s00776-010-1496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Earp BE, Mora AN, Floyd WE, et al. Predictors of acute carpal tunnel syndrome following ORIF of distal radius fractures: a matched case–control study. J Hand Surg Glob On. 2019;1(1):6-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsg.2018.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dyer G, Lozano-Calderon S, Gannon C, et al. Predictors of acute carpal tunnel syndrome associated with fracture of the distal radius. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(8):1309-1313. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cooney WP, Dobyns JH, Linscheid RL. Complications of Colles’ fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(4):613-619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aro H, Koivunen T, Katevuo K, et al. Late compression neuropathies after Colles’ fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988(233):217-225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haase SC, Chung KC. Management of malunions of the distal radius. Hand Clin. 2012;28(2):207-216. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Watanabe K, Ota H. Carpal malalignment as a predictor of delayed carpal tunnel syndrome after Colles’ fracture. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7(3):e2165. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stewart HD, Innes AR, Burke FD. The hand complications of Colles’ fractures. J Hand Surg Br. 1985;10(1):103-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Graham B, Regehr G, Naglie G, et al. Development and validation of diagnostic criteria for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(6):919-924. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Graham B. The value added by electrodiagnostic testing in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(12):2587-2593. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Medoff RJ. Essential radiographic evaluation for distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 2005;21(3):279-288. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Medoff RJ. Radiographic evaluation and classification of distal radius fractures. In: Fractures and Injuries of the Distal Radius and Carpus. Elsevier; 2009:17-31. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-4160-4083-5.00005-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bacorn RW, Kurtzke JF. Colles’ fracture; a study of two thousand cases from the New York State Workmen’s Compensation Board. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1953;35-A(3):643-658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heim D, Stricker U, Rohrer G. [Carpal tunnel syndrome after trauma]. Swiss Surg. 2002;8(1):15-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lynch AC. The carpal tunnel syndrome and Colles’ fractures. JAMA. 1963;185(5):363-366. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060050041018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lidström A. Fractures of the distal end of the radius: a clinical and statistical study of end results. Acta Orthop Scand. 1959;30(suppl 41):1-118. doi: 10.3109/ort.1959.30.suppl-41.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Young BT, Rayan GM. Outcome following nonoperative treatment of displaced distal radius fractures in low-demand patients older than 60 years. J Hand Surg Am. 2000;25(1):19-28. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2000.jhsu025a0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stern PJ, Derr RG. Non-osseous complications following distal radius fractures. Iowa Orthop J. 1993;13:63-69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kwasny O, Fuchs M, Schabus R. Opening wedge osteotomy for malunion of the distal radius with neuropathy. 13 cases followed for 6 (1-11) years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1994;65(2):207-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Megerle K, Baumgarten A, Schmitt R, et al. Median neuropathy in malunited fractures of the distal radius. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2013;133(9):1321-1327. doi: 10.1007/s00402-013-1803-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Müller M, Poigenfürst J, Zaunbauer F. [Carpal tunnel syndrome following Colles’ fracture (author’s transl)]. Unfallheilkunde. 1976;79(9):389-394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Graham TJ. Surgical correction of malunited fractures of the distal radius. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5(5):270-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fujitani R, Omokawa S, Iida A, et al. Reliability and clinical importance of teardrop angle measurement in intra-articular distal radius fracture. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(3):454-459. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dresing K, Peterson T, Schmit-Neuerburg KP. Compartment pressure in the carpal tunnel in distal fractures of the radius: a prospective study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1994;113(5):285-289. doi: 10.1007/BF00443819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Keir PJ, Bach JM, Hudes M, et al. Guidelines for wrist posture based on carpal tunnel pressure thresholds. Hum Factors. 2007;49(1):88-99. doi: 10.1518/001872007779598127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dekel S, Papaioannou T, Rushworth G, et al. Idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome caused by carpal stenosis. Br Med J. 1980;280(6227):1297-1299. doi: 10.1136/bmj.280.6227.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]