Abstract

Introduction

Syphilis is a chronic infection caused by Treponema pallidum. Manifestations of this disease are vast, and syphilitic hepatitis is a rarely depicted form of secondary syphilis.

Case Presentation

We report the case of a 63-year-old man with worsening jaundice, maculopapular rash and perianal discomfort. Proctological examination with anoscopy revealed a perianal gray/white area with millimetric pale granules along the anal canal. Liver function tests showed a mixed pattern. Venereal Disease Research Laboratory, T. pallidum hemagglutination assay and IgM fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbance were positive. The patient was successfully treated with a single dose of penicillin G.

Discussion/Conclusion

Syphilitic hepatitis is scarcely reported in the literature. Secondary syphilis with mild hepatitis rarely leads to hepatic cytolysis and jaundice. Many signs of secondary syphilis including syphilitic hepatitis may be linked to immune responses initiated during early infection. Over the past decades, evidence has emerged on the importance of innate and adaptive cellular immune responses in the immunopathogenesis of syphilis. This report raises awareness to a clinical entity that should be considered in patients at risk for sexually transmitted diseases, who present with intestinal discomfort or liver dysfunction, as it is a treatable and fully reversible condition.

Keywords: Syphilis, Treponema pallidum, Syphilitic hepatitis, Secondary syphilis, Case report

Resumo

Introdução

A sífilis é uma infeção crónica provocada pelo Treponema pallidum. As manifestações desta doença são vastas e a hepatite sifilítica é uma forma de sífilis secundária raramente descrita.

Caso Clínico

Apresentamos o caso de um doente de 63 anos com icterícia de agravamento progressivo, rash maculopapular e desconforto perianal. O exame proctológico complementado por anuscopia revelou uma região perianal cinzenta-esbranquiçada com grânulos pálidos milimétricos ao longo do canal anal. Testes de função hepática revelaram um padrão misto e o Venereal Disease Research Laboratory, T. pallidum hemagglutination assay e IgM fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbance foram positivos. O doente foi tratado com sucesso com uma dose única de penicilina G.

Discussão/Conclusão

São raros os casos de hepatite sifilítica descritos na literatura. Sífilis secundária com hepatite ligeira raramente conduz a citólise hepática e icterícia. Muitos dos sinais de sífilis secundária, incluindo a hepatite sifilítica, parecem estar associados a respostas imunitárias iniciadas durante o período de infeção precoce. Ao longo das últimas décadas, têm surgido evidências crescentes sobre a importância das respostas imunes inata e adaptativa na patogénese da sífilis. Este caso clínico descreve uma entidade nosológica que deve ser considerada em doentes em risco de contraírem doenças sexualmente transmissíveis, que se apresentem com desconforto intestinal ou disfunção hepática, visto tratar-se de uma condição tratável e totalmente reversível.

Palavras Chave: Sífilis, Treponema pallidum, Hepatite sifilítica, Sífilis secundária, Caso clínico

Introduction

Syphilis is a chronic infection caused by Treponema pallidum. Nowadays, we have a relatively complete understanding of the natural history of untreated syphilis. However, the pathogenic mechanism of T. pallidum is still not fully understood [1]. Some authors suggest that manifestations like syphilitic hepatitis (SH) are likely due to innate and adaptative cellular immune responses.

Case Report

A 63-year-old man was admitted to the Emergency Department with a 1-month history of worsening jaundice and perianal discomfort. The patient had an unremarkable medical history. He denied any medication, alcohol consumption, drug administration or unprotected sexual intercourse.

Physical examination revealed icteric skin and mucosae and a maculopapular rash on the palms, inguinal region, legs and soles (Fig. 1). Genital lesions, such as chancre, were discarded. Proctological examination revealed a perianal gray/white area and painless nodular lesions on the superior anal canal and distal rectum. Anoscopy confirmed millimetric pale granules along the anal canal.

Fig. 1.

Maculopapular rash on the palms.

Liver function tests on admission showed a mixed pattern − total/direct bilirubin of 8.3/6.9 mg/dL (normal: 0.3–1 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase of 105 IU/L (normal: <34 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase of 188 IU/L (normal: <44 IU/L) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 670 IU/L (normal: <120 IU/L). Further investigations including hepatitis A, B and C, HIV, cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr serology, ceruloplasmin, α1-antitrypsin, iron studies, smooth muscle, antinuclear and antimitochondrial antibodies were unremarkable.

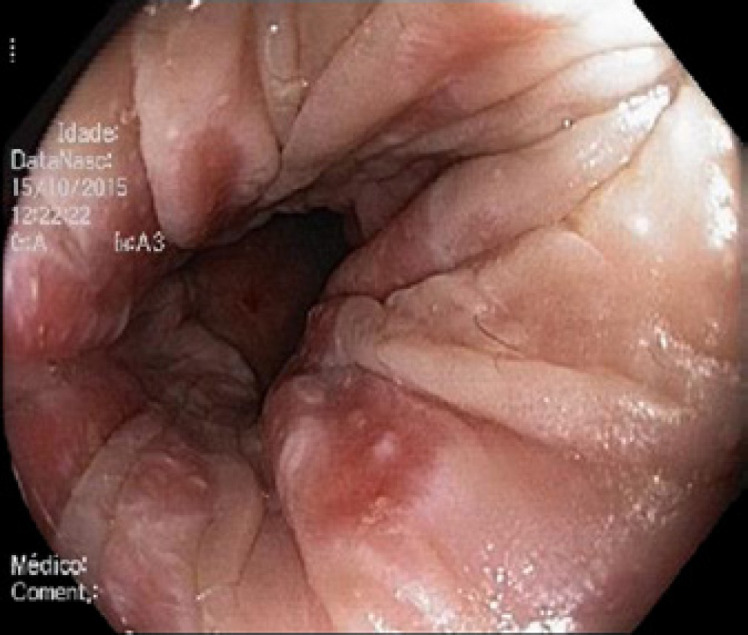

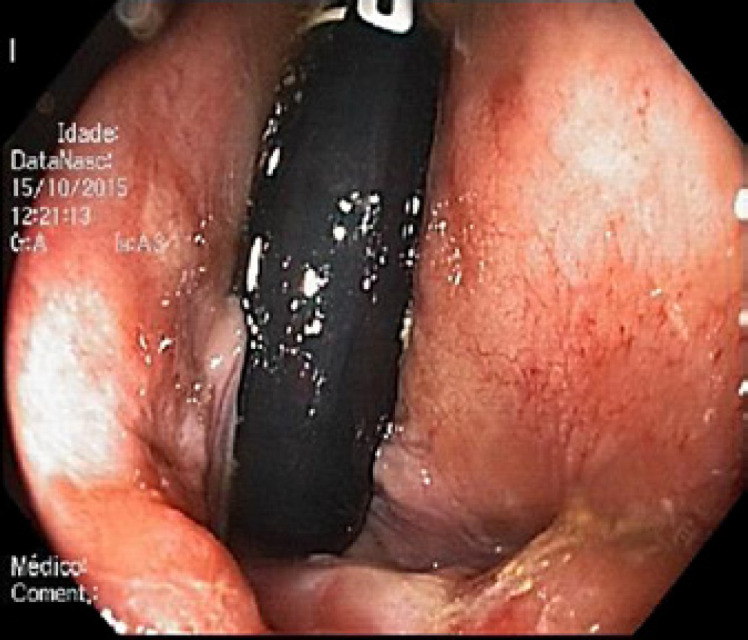

Abdominal ultrasound revealed a normal liver parenchyma and biliary tree. Colonoscopy showed an indurated nodular mucosa around the rectal lumen (Fig. 2, 3, 4). Histology of the biopsied rectal mucosa revealed an unspecific inflammatory cell infiltrate.

Fig. 2.

Tubular rectum − hardened and erythematous mucosa with pale nodular lesions.

Fig. 3.

Tubular rectum − hardened and erythematous mucosa with pale nodular lesions.

Fig. 4.

Retroflexion in the rectum − hardened and erythematous mucosa with pale nodular lesions.

ALP levels increased to 1,355 IU/L, and the maculopapular lesions remained unresolved. Suspecting a dermatological disease with perianal manifestations, consultation by Dermatology was requested, along with serological tests for syphilis. Results showed a Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) titer of 1/256, a T. pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA) of 1/5,120 and a positive IgM fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbance (IgM FTA-abs). At this point, the patient mentioned one unprotected heterosexual intercourse with a shared object, 2 months before the onset of symptoms.

The patient was treated with a single dose of penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million units intramuscularly). Jaundice and the rash lesions progressively subsided. Cytolysis resolved and cholestasis gradually disappeared. IgM FTA-abs results became negative, whereas VDRL and TPHA titers decreased over time.

Response to the standard regimen for early syphilis allowed the authors to confirm the diagnosis of SH.

Discussion/Conclusion

Untreated syphilitic infections may cause the widespread dissemination of T. pallidum, and approximately 25% of patients will primarily exhibit a systemic illness, representing the secondary stage of syphilis [2].

Condylomata lata are relatively common, occurring in about one third of patients suffering from syphilis. However, proctitis and hepatitis are a much less studied reflection of secondary syphilis (SS).

Regarding the absence of genital wounds, we considered the proctological lesions as the primary site of inoculation. Despite these, biopsies of the rectal mucosa failed to show spirochetes. However, it is well established that T. pallidum is impossible to visualize by direct microscopy and unable to grow in culture [1].

The frequency of SH ranges from 1 to 50% [3], but it is rarely reported in the literature. Mild hepatitis characterized by high serum ALP levels is the most frequent hepatic manifestation of SS, but it rarely leads to hepatic cytolysis and jaundice [4, 5].

Some authors report that liver biopsies of patients with SH may reveal focal necrosis, acute inflammatory infiltrate, Kupffer cell hyperplasia and bile duct injury. In addition, spirochetes may be identified using silver staining. However, the majority of case reports failed to reveal treponemes in liver biopsies [6, 7, 8, 9].

Since our patient had a classical skin involvement, highly suspicious of syphilis, we decided to ask for an early dermatology consultation, prior to a liver biopsy.

According to the diagnostic criteria established by Mullick et al. [10], patients with abnormal liver enzyme levels, serological evidence for syphilis with a positive TPHA titer in conjunction with an acute clinical presentation consistent with SS, exclusion of alternative causes of hepatic injury and improvements in liver enzyme levels with an appropriate antimicrobial therapy can securely be diagnosed with SH without the need of a liver biopsy. Regarding that, our patient met all the aforementioned criteria, and to prevent unnecessary invasive procedures, we therefore decided not to perform a liver biopsy.

Although some authors still prefer the administration of 3 doses of penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million units intramuscularly) each at 1-week intervals [4, 8], evidence suggests a lower number of cures with a triple dose of penicillin G benzathine compared to a single dose of penicillin G benzathine [11]. Current treatment guidelines advocate a single dose of penicillin G benzathine (2.4 million units intramuscularly) as the recommended regimen for SS [11, 12].

Many signs of SS including SH may be linked to immune responses initiated during early infection [13]. Over the past decades, evidence has emerged on the importance of innate and adaptive cellular immune responses in the immunopathogenesis of syphilis [14]. The adaptive component was documented first, with the publication of experiments in rabbit models showing that the replication of treponemes at the inoculation site elicited an intense inflammatory response resembling a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction [13]. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that syphilitic lesions in humans also contained cellular elements associated with adaptive immunity, including cytokine-producing Th1 cells. The contribution of innate responses to lesion development and resolution was studied both in vitro and in vivo, establishing that spirochetal lipoproteins are capable of activating macrophages via CD14 and Toll-like receptor 1/2 signaling pathways. Hence, these pathogen-associated molecular patterns are now believed to be the major proinflammatory agonists during spirochetal infection [15, 16]. Despite this apparent immune control, simultaneous widespread dissemination of spirochetes occurs.

Clinicians should bear in mind the possibility of syphilitic involvement in patients at risk for sexually transmitted diseases who present with intestinal discomfort or liver dysfunction, as it is a treatable and fully reversible condition.

Statement of Ethics

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the case publication. The case was presented as a poster at the Hepathology Portuguese Scientific meeting on April 2016.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The authors have no funding sources to declare.

Author Contributions

J.A.C.N. wrote, edited and approved the final paper and is the article guarantor. J.R. wrote, edited and approved the final paper. H.T.S. and R.M. revised the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final paper.

References

- 1.Magnuson HJ, Thomas EW, Olansky S, Kaplan BI, De Mello L, Cutler JC. Inoculation syphilis in human volunteers. Medicine (Baltimore) 1956 Feb;35((1)):33–82. doi: 10.1097/00005792-195602000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark EG, Danbolt N. The Oslo study of the natural history of untreated syphilis; an epidemiologic investigation based on a restudy of the Boeck-Bruusgaard material; a review and appraisal. J Chronic Dis. 1955 Sep;2((3)):311–44. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(55)90139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung KY, Lee MG, Chon CY, Lee JB. Syphilitic gastritis: demonstration of Treponema pallidum with the use of fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption complement and immunoperoxidase stains. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989 Aug;21((2 Pt 1)):183–5. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baveja S, Garg S, Rajdeo A. Syphilitic hepatitis: an uncommon manifestation of a common disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2014 Mar;59((2)):209. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.127711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adachi E, Koibuchi T, Okame M, Sato H, Imai K, Shimizu S, et al. Case of secondary syphilis presenting with unusual complications: syphilitic proctitis, gastritis, and hepatitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2011 Dec;49((12)):4394–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01240-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agrawal NM, Sassaris M, Brooks B, Akdamar K, Hunter F. The liver in secondary syphilis. South Med J. 1982 Sep;75((9)):1136–8. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198209000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campisi D, Whitcomb C. Liver disease in early syphilis. Arch Intern Med. 1979 Mar;139((3)):365–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandache C, Coca C, Caro-Sampara F, Haberstezer F, Coumaros D, Blicklé F, et al. A forgotten aetiology of acute hepatitis in immunocompetent patient: syphilitic infection. J Intern Med. 2006;259(England):p. 214–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlossberg D. Syphilitic hepatitis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987 Jun;82((6)):552–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullick CJ, Liappis AP, Benator DA, Roberts AD, Parenti DM, Simon GL. Syphilitic hepatitis in HIV-infected patients: a report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2004 Nov;39((10)):e100–5. doi: 10.1086/425501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guidelines WH, Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Treponema pallidum (Syphilis) Geneva: World Health Organization © World Health Organization. 2016:2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64((Rr-03)):1–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker-Zander S, Sell S. A histopathologic and immunologic study of the course of syphilis in the experimentally infected rabbit. Demonstration of long-lasting cellular immunity. Am J Pathol. 1980 Nov;101((2)):387–414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radolf JD, Lukehart SA. Immunology of syphilis. In: Radolf JD, Lukehart SA, editors. Pathogenic treponemes: cellular and molecular biology. Norfolk, UK: Caister Academic Press; 2006. pp. pp. 285–322. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wooten RM, Weis JJ. Host-pathogen interactions promoting inflammatory Lyme arthritis: use of mouse models for dissection of disease processes. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001 Jun;4((3)):274–9. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salazar JC, Hazlett KR, Radolf JD. The immune response to infection with Treponema pallidum, the stealth pathogen. Microbes Infect. 2002 Sep;4((11)):1133–40. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01638-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]