Objective

The objective of this review was to investigate the epidemiological characteristics of maxillofacial fractures (MFFs), to establish the prevalence of MFFs, and to recognise the major causative factors in both males and females in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Study design: The protocol of this systematic reviews was established according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P); the following databases were searched: PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Google Scholar and Web of Science. We used STROBE checklist to assess the risk of bias in all identified studies, 37 studies fulfilled the eligibility criteria, and hence were selected for analysis. Results: A total of 27,994 patients (22,965 males and 5,129 females) ranging from 0 to 97 years who experienced maxillofacial injuries during the study period were entered into this review. Road traffic accidents (RTAs) were the most common cause of MFF followed by falls. The mandible was the most common site of injury. In the MENA region, males outnumbered females in terms of maxillofacial injuries with a ratio of 4.5:1. Conclusion: Maxillofacial fractures are highly prevalent in the MENA region, and they are mainly caused by RTAs, especially among young males. Therefore, the concerned authorities need to employ and implement stricter traffic rules in order to minimise the risk of maxillofacial injuries and their subsequent increased morbidity and mortality rates.

Key words: Maxillofacial trauma, Road traffic accidents, Middle East, MENA, Systemic review

INTRODUCTION

The Middle East is a transcontinental region that is centred on Western Asia and extends to North Africa. The Middle East covers an area of 8,217,982 km2, and consists of 17 countries with a total population of 384,475,487 inhabitants. North Africa is a region that stretches from the Atlantic Ocean in Mauritania in the west to the Red sea in the east with a population of 189,967,627 million.1 Maxillofacial fractures (MFFs) are considered one of the most common injuries identified in the emergency departments of hospitals around the world. During the initial examination and diagnosis, particular attention should be dedicated to this area because of the juxtaposition to vital anatomical structures near the head and neck area. It is paramount that these structures are thoroughly evaluated whenever a trauma in this area occurs.2 The increasing pace of modern life, high-speed travel, growing frequency of violence, crowded societies, the magnitude of traffic accidents, sports injuries, combat injuries and industrial traumas have rendered MFFs a distinct form of social disease that does not offer immunity to anyone.

The main causes of MFFs on a worldwide level may frequently vary between countries and also within the same country. This significant erraticism in reported aetiologies is due to the diversity of contributing influences, such as cultural, environmental and socioeconomic factors.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

Conventionally, road traffic accidents (RTAs) have been considered to be the most common cause of MFFs in both developed and developing countries.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 However, there is a notable reduction in the MFF rates associated with RTAs in developed countries, which can be attributed to several factors, including significant public education and behavioural changes, implementation of speed limits, the prevalent use of seat belts, wearing helmets by motorcycle drivers, alcohol restriction, improvement of road quality, better motor vehicle safety, effective legislation and its subsequent implementation.14

In order to establish the significance and the applicability of the underlying prevention strategies, an evaluation of the prevalence of the MFF and the gravity of the associated injuries are needed. A literature search such as in Nigeria15, Australia16, India,17 Pakistan,18 Brazil,19 USA,20 Scotland,21 Norway,22 Austria23 and Uganda24 shows a multitude of epidemiological studies across diverse populations. Furthermore, in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, there are numerous published studies that investigate the patterns and severity of maxillofacial injuries, such as in KSA,25 UAE3, Kuwait,26 Qatar,6,7 Iraq,27 Jordan,28 Egypt,29 Sudan30 and Libya.31 However, to the best of our knowledge, current literature is lacking combined and extended research regarding maxillofacial injuries in this region. Therefore, and to gain a greater understanding of the pattern of maxillofacial injuries in the MENA region, the aim of this study was to investigate the epidemiological characteristics of maxillofacial injuries in the MENA region, determine the respective prevalence of MFF injuries, and to identify the foremost contributing factors in both males and females.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protocol and registration

The protocol of the study was established according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P), and the reporting of the present systematic review was carried out based on the PRISMA checklist.

Information sources and search strategy

In this study, the following databases were searched: PubMed/MEDLINE, SCOPUS, Google Scholar and Web of Science with no language restriction. An additional search was performed by hand-searching journals included in the acquired research studies according to their respective reference list. The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms selected for the purposes of this search included ‘facial injuries’, ‘maxillofacial injuries’, ‘aetiology’, epidemiology’, ‘children’, ‘pediatrics’ and ‘adolescent’. Because a high number of studies are linked with these terms, the Boolean operator NOT was used to exclude the following MeSH terms: ‘animals’. ‘burns’, ‘facial nerve’ and ‘eye’. The titles of the respective identified articles were then evaluated for potential associations between MFF injuries and RTAs, violence, sport-related fall, and industrial causes and concomitant MFF injuries, and a combination of these terms.

Subsequently, we used the PICO framework, which stands for P (Patient Population), I (Intervention or Exposure—in case of observational studies), C (Comparison) and O (Outcomes). In this systematic review, the PICO approach involved Population (children and adults with maxillofacial injuries), Exposure (aetiology of maxillofacial trauma), Comparison (the different MENA countries: KSA, UAE, Kuwait, Qatar and Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Yemen, Egypt, Sudan, Morocco, Libya, Algeria and Tunisia) and Outcome (prevalence maxillofacial trauma).

Eligibility criteria

The following eligibility criteria were implemented for the acquisition of research studies that were directly related to the purpose of this study: studies needed to be available as full-text articles and not merely in the form of an abstract. Moreover, they needed to employ a retrospective or prospective design that focuses on all age groups (both children and adults) and on civilian-type injuries. In addition, studies were included provided that injuries were diagnosed as a result of patients’ complaints, and verified clinically, radiographically and during treatment. For each of the included studies, a data collection form was used to identify the country, study interval, age group, male-to-female ratio, causes of MFF, and site of injuries. Studies with the following characteristics were excluded: studies providing only epidemiological data on particular groups or conditions (such as children, older adults and military exercises), as well as studies that only reported specific MFF types.

Quality of the studies

We used the recommended Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist32 to assess the risk of bias in all identified and collected full-text articles included in this study as follows: (a) had clearly defined the source of participant selection; (b) had clearly defined eligibility criteria; (c) explained how exposure was measured; (d) explained how outcomes were measured; (e) provided appropriate follow-up information; (f) defined their sample sizes; and (g) had clearly defined aims and objectives.

The quality of the included studies was assessed independently by two authors (FK and KB). Fourteen checklist criteria were selected, and the collected studies were classified into three categories: studies presenting 10 out of 14 criteria were selected as low-risk of bias; six–nine criteria were considered as moderate-risk of bias; and studies that had only five criteria were selected as having a high-risk of bias.

The value of weighted kappa statistic between author agreements was 87%. After confirming the quality of each study, two authors (FK and KB) independently extracted the data to the pre-specified data extraction sheet in Microsoft Excel. Variables extracted from each eligible study included: name of the first author; year of publication; length of the study; location of the study; study design; median follow-up time; source of data; sample size; mean age; causes of MFF; and site of MFF. We could not perform a cumulative analysis as the outcome of variables was not homogeneous across the selected studies.

RESULTS

Study selection

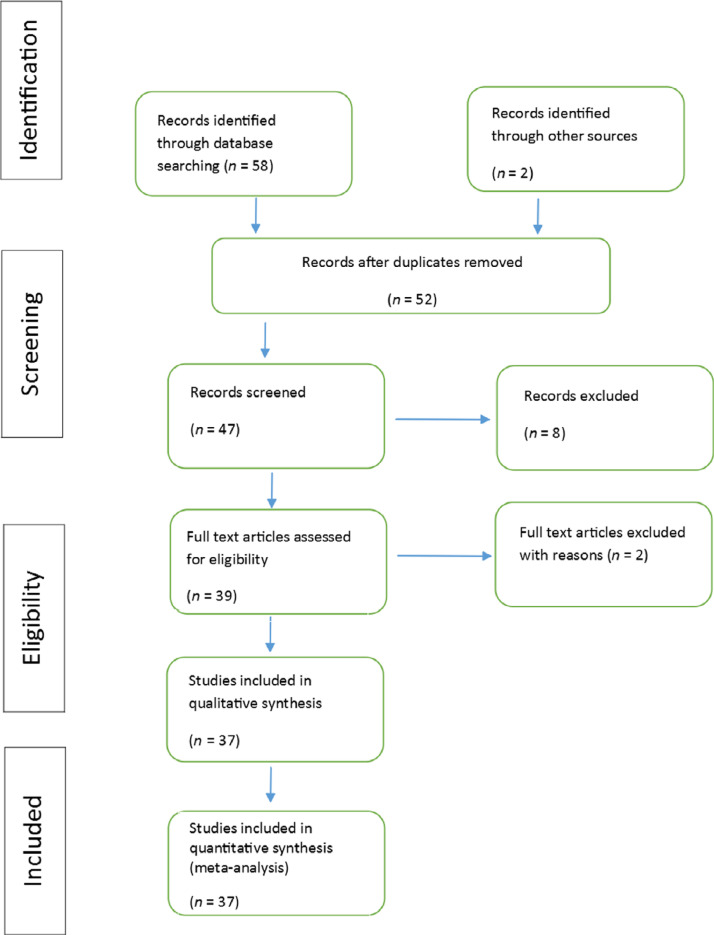

The search strategy resulted in 52 studies and, after removing, the duplicate 48 studies were included for full-text reading. Subsequently, 10 studies were excluded because they failed to fulfill the eligibility criteria, and hence 38 studies were included for analysis in this systematic review (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA chart.

Study characteristics

A total of 38 articles published between 1987 and 2018 that satisfied our inclusion criteria were included in the review. Out of 38 studies selected, 36 were classified as low-risk bias and two were classified as moderate-risk bias (Table 1). In the MENA region, a total of 27,994 patients were included (22,965 males and 5,129 females), for which the male/female ratio ranged from 11.1 in UAE to 2.1 in KSA, with an age range between 0 and 97 years (Table 2). The mandible is the most common site of injury in all of the MENA countries, except in Iran where nasal bone fracture was the most common site of fracture. RTAs were the most common cause of MFF followed by falls, except in Iraq where missile injuries were the dominant cause of maxillofacial trauma (Table 2).

Table 1.

Quality assessment of the studies using STROBE criteria (x = presence of criteria)

| Criteria | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/year | Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Study design | Data source | Study size | Causes of MFF | Common site of MFF | Statistical method | Summary of results | Follow up | Outcome | Treatment | limitation | Objective | Risk of bias |

| Elarabi, 201841 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 9 | ||||

| AlQahtani, 201861 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 9 | ||||

| AlBokhamseen, 201862 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Cenk, 20189 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Elarabi, 201731 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Rezaie, 201752 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Samman, 201734 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Mahdi, 201630 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Melek, 201629 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| AL-Aanazi, 201633 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| JAN, 201563 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Almasri, 201564 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Sehimy, 201565 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Almasri, 201566 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Walid, 20134 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Elawad, 201267 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Oikarinen, 200426 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| AlAhmed, 201968 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Nwoku, 200446 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Klenk, 20032 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Qudah, 200269Rabi, 200270 | XX | X X |

X X |

X X |

X X |

X X |

X X |

X X |

X X |

X X |

10 10 |

|||

| Bataineh, 199871 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Jaber, 199772 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Lawoyin, 199625 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

| Karyouti, 198773 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | |||

Table 2.

Summary of MFF injuries in the Middle East and North Africa

| Author/year | Country | Data Source | M:F ratio | Age range | Site of MFF | Main cause | Other causes | Total no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klenk, 20032 | UAE | Hospital records | 5:1 | 20–26 years | Mandible (53.4 %) | RTA (59%) | Falls (21.5%) Camel accidents (5.5%) |

144 |

| Oikarinen, 200426 | Kuwait | Published articles | 6.7:1 | 20–30 years | Mandible | RTA (55%) | Falls (22%) | 596 |

| Al Ahmed, 20043 | UAE | Hospital records | 11:1 | 20–29 years | Mandible (51%) | RTA (75%) | Falls (12%) | 230 |

| AlKhateeb, 200737 | UAE | Hospital records | 7:1 | 2–82 years | Mandible (70.5%) | RTA | * | 288 |

| Raval, 20115 | UAE | Hospital records | * | 11–30 years | Mandible (53%) | RTA (75%) | Falls (15%) | 177 |

| A.l Sheikhly, 20127 | Qatar | Hospital records | 4:1 | 11–40 years | * | RTA (56.25%) | Assaults (3.1%) | 9,600 |

| Firas, 20126 | Qatar | Hospital records | 8.7:1 | 17–20 years | Mandible | RTA (78%) | Falls (15.6%) Sports (10.9%) |

46 |

| Lawoyin, 199625 | KSA | Hospital records | 5.2:1 | 21–30 years | Maxilla | RTA | * | 980 |

| Rabi, 200270 | KSA | Hospital records | 5.2:1 | 21–30 years | Mandible (41%) Maxilla (59%) |

RTA (63%) | Others (37%) | 403 |

| Nwoku, 200446 | KSA | Hospital records | 5.2:1 | 9–70 years | Maxilla (61.4) Mandible (38.6%) |

RTA (87.1%) | Assaults (5.2%) Sports (4%) | 986 |

| Abdullah, 20134 | KSA | Hospital records | 6:1 | 10–29 years | Mandible 56.4% | RTA (86.1%) | Falls (50–60 %) | 200 |

| Almasri, 201564 | KSA | Hospital records | 10:1 | 20–30 years | Mandible 50.68 % | RTA (88.7%) | Assaults (6%) | 101 |

| Almasri, 201566 | KSA | Hospital records | 4.4:1 | 3–97 years | Mandible 54.19% | RTA | * | 965 |

| JAN, 201563 | KSA | Hospital records | 6:1 | 3–87 years | Mandible | RTA | Assaults (12.1%) | 853 |

| Alsehimy, 201565 | KSA | Hospital records | 6:1 | 3–87 years | Mandible (58%) Maxilla (42%) |

RTA | * | 853 |

| Al-Anazi, 201633 | KSA | Hospital records | 2.1:1 | * | Mandible (21.0%) Maxilla (79.0%) |

RTA (24%) | Others (76%) | * |

| Samman, 201734 | KSA | Hospital records | 5.15:1 | 3–86 years | Mandible | RTA (90.35%) | Falls (6.09%) | 197 |

| AlQahtani, 201861 | KSA | Hospital records | All males | 15–25 years | Mandible (49%) | RTA (71%) | * | 215 |

| AlBokhamseen, 201862 | KSA | Hospital records | 8.3:1 | 2–77 years | Mandible (54.6%) Maxilla (45.4%) |

RTA (63.3%) | Falls (15.9%) | 270 |

| AlHammad, 201968 | KSA | Records | 9:1 | 20–24 | Midface (64%) | RTA (80%) | Falls | 372* |

| Karyouti, 19 8 773 | Jordan | Hospital records | * | 0–5 years | Mandible | RTA | Assaults | |

| Qudah, 200269 | Jordan | Hospital | * | 1–15 years | Mandible (74.5%) | Falls (52%) | RTA (20%) | 274 |

| AlKhawalde, 201140 | Jordan | Hospital records | 9:1 | 18–35 years | Mandible (54%) Maxilla (36%) |

RTA (75%) | Falls (12%) | 620 |

| Qudah et al., 200528Kummoona, 201174 | Jordan Iraq |

Hospital records Hospital records | 2.5:1 3.7:1 |

30 years 1–75 years | Mandible Mandible (42.64%) Orbit (35.07%) |

RTA Falls | * | 703 673 |

| Tahrir, 201227 | Iraq | Hospital records | * | 8–75 years | Mandible (40%) | Missile injuries | * | 518 |

| Zandi, 201175 | Iran | Hospital records | 3.4:1 | * | Nasal bone (63.4%) | RTA (35%) | * | 2,450 |

| Rezaie, 201752 | Iran | Hospital records | 3.5:1 | 21–30 years | Nasal bone (45.5%) | RTA (74.8%) | Assaults (13.2%) | 1,727 |

| Atilgan, 201038 | Turkey | Hospital records | 2.3:1 | 1–80 years | Mandible (36%) | RTA (65%) | * | 532 |

| Cenk, 20189 | Turkey | Hospital records | 2.4:1 | 1–86 years | Mandible (52.2%) | RTA (25.5%) | Falls (17.6%) | 1,266 |

| Melek, 201629 | Egypt | Hospital records | 4.5:1 | 1.5–75 years | Maxilla (70%) | RTA (77.9%) | * | 177 |

| Elawad, 201267 | Sudan | Hospital records | 4:1 | 20–29 years | Nasal bone (36%) | RTA (39.4%) | Assaults (24.8%) | 218 |

| Al Mahdi, 201630 | Sudan | Hospital records | 2.2:1 | 16 years | Mandible (77%) | RTA (56.4%) | Daily activities (21.1%) | 390 |

| Jaber, 199772 | Libya | Hospital records | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | 290 |

| Elgehani, 200976 | Libya | Hospital records | 7.1:1 | 8 months to 72 years | Mandible | RTA | Assaults | 493 |

| El Arabi, 201731 | Libya | Hospital records | 4.8:1 | 7 months–84 years | Mandible 59.18% | RTA (63.8%) | Assaults and falls (12%) | * |

| El Arabi, 201841 | Libya | Hospital records | 7:1 | 21–30 years | * | RTA (58.2%) | Assaults (17.11%) | 187 |

KSA, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; MFF, maxillofacial fracture; RTA, road traffic accident; UAE, United Arab Emirates. * and ** Denote missing information.

DISCUSSION

Comparatively, the face is the most unprotected part of the body, and hence significantly more vulnerable to trauma. Statistically, it has been shown that trauma is one of the major causes of death in people under 40 years old.23 It is not only difficult but also not appropriate to compare between epidemiological investigations due to differences in study population, geographic region, socioeconomic status, cultural reasons and traffic rules. In our current study, RTAs accounted for 24%33 to 90.3%34 of injuries in the MENA countries. This wide range found between different studies can be attributed to differences in reporting and recording MFFs in the studied countries, or it may be a reflection of the proportion of vehicles registered in MENA countries. Furthermore, this can also be explained by the fact that some patients seen in neurosurgical, casualty, orthopaedic, ENT and other units exhibited maxillofacial injuries with concomitant severe injuries in other body regions.35 Moreover, patients with minor maxillofacial injuries did not need to undergo any treatment in the specialised maxillofacial surgery departments.

In the MENA region, males were found to outnumber females in terms of maxillofacial injuries, with a M:F ratio ranging between 2.1:133 and 11:13, and with an overall ratio of 4.5:1 in all countries in the MENA region. This profound difference can be ascribed to lifestyle differences in these countries, in which males are the majority of drivers, especially in Saudi Arabia where women were not permitted to drive cars until recently. Likewise, reports have also demonstrated that there is a tendency for assaulted female patients with maxillofacial injuries to provide inadequate documentation because of cultural reasons pertaining to the societal position of women in these countries.36

Our findings were comparable to reports from other populations, such as 3.4:1 in Brazil,19 5:1 in Nigeria,15 but were found to be lower compared with countries such as India (10:1)10 and USA (7:1).20 The high male-to-female ratio in these parts of the world is perhaps due to the great number of male drivers, types of employment, participation in sports, and increased consumption of alcohol and drugs.37

In the MENA region, maxillofacial injuries are caused by RTAs as most of the MENA countries do not have alternative means of transportation and the majority of inhabitants prefer motor vehicle transportation as opposed to using any other transportation method. Additional reasons that influence the prevalence of maxillofacial injuries from RTAs involve poor road infrastructure and the high percentage of old vehicles without any prominent safety features.29,36,38,39 Iraq was the only country in the study where MFFs were mainly caused by missile injuries, as Iraq has been involved in multiple wars since 2003 up to date. Collected data from different countries such as KSA,8 the United Arab Emirates,3 Jordan,40 Sudan,30 Libya41 and Turkey9 have shown that 24%–93.3% of MFFs were related to RTAs. The primary reason for this high rate includes absence or weak road traffic regulations, their subsequent complacent implementation in road practice, distinct lack of strict traffic legislation regarding wearing of seat belts, both in the front and the back, helmet use, risky driving, inferior road quality, inadequate or passive safety features in vehicles, undesignated pedestrian crossings, jay-walking, and increased usage of motor vehicles and cycles.

Earlier studies conducted in Europe and America revealed that RTAs comprised the most frequent cause of facial injuries.35,42 Over the period of time, studies have shown that the prevalence of the most common cause of maxillofacial injuries in developed countries has turned out to be assault,43, 44, 45 while traffic accidents continue to be the most prevailing cause in many developing countries.3,15,46, 47, 48

Assaults and falls were recorded closely behind the traffic accidents in the MENA region. These discrepancies could be attributed to the lower socioeconomic circumstances of these countries, including high unemployment rates in younger populations that facilitate greater levels of stress and propensity to crime. Furthermore, an additional reason for this high prevalence of MFFs involves the distinct availability and ease of access to weapons in some MENA countries.

This study reveals that the mandible was the most common affected site when evaluating maxillofacial trauma because it is the most prominent bone in the face and is usually unprotected when drivers do not wear helmets. Therefore, it is significantly more exposed to trauma compared with any other facial bone. It is also reported that mandibular fractures are more commonly affected than midfacial fractures in other countries;48 our results are consistent with the findings in other reports.42, 43, 44 The peculiar ‘U’-shape of the mandible coupled with its mobility and lower bone support as opposed to the maxilla has been associated with this increased incidence of fractures to the mandible.16,21 Nevertheless, some other studies have identified contrary results and implicated midface fractures, such as the LeFort types and orbital floor fractures, as more common than mandibular fractures in some populations.49,50 Perhaps, due to financial constraints, a possible underutilisation of advanced imaging technology of the MFFs (e.g. CBCT) in some MENA countries may be somewhat accountable for the perceived difference, as the midface skeleton is relatively more challenging to evaluate using conventional radiography compared with the mandible.51 Therefore, the presence of thin bones, fluid-filled spaces and soft tissues renders the accurate assessment of this injury as difficult because the respective images do not provide an increased level of contrast.51 On the other hand, the disparity in the occurrence of midface trauma may be associated with the drivers’ and motorists’ disinclination to use safety devices.

Iran was the only country where the nasal bone was the most common site of injury. This may be attributed to low awareness regarding seat belt use in motor vehicles as the percentage of drivers wearing seat belts was found to be very low,52 thus enabling direct facial collision with the steering wheel in case of an accident, and hence causing an immediate nasal fracture. In contrast to the MENA region's findings, the zygomatic fractures were stated as the most common subtype among midfacial fractures in both children and adults in some other studies.50,51,53

The incidence of involvement of the facial skeleton has varied geographical distribution, as seen in a study from Australia between 1994 and 1997. They identified tooth and alveolar process injuries followed by zygomatic complex fractures as the most common maxillofacial injuries involved in the traffic accidents.54,55 In fact, current research on maxillofacial injuries following steering wheel contact by drivers who did not use their seat belts highlights that nasal fractures had the main incidence, i.e. 43.8%.56 Our results demonstrate a significantly lower incidence of nasal fractures (5.5%). This is perhaps due to the fact that the majority of isolated nasal fractures are managed by the ENT surgeons or is due to their under-reporting.

There is strong evidence of a relationship between MFF and patient demographic characteristics regardless of the type of sports and country. In fact, high levels of physical activity in young adult males aged from 20 to 30 years can underline why the majority of these types of fractures are observed in this age group. On the other hand, the risk of a sport-related MFF decreases with age, and especially for elderly people who are older than 50 years.54,55

Industrial injuries were not recorded in the MENA region. However, a study performed in other regions of the world reported that 4.5% of all MFFs are caused by industrial injuries.56

The mandatory fastening of seat belts for all passengers is one of the interventions to minimise trauma in users of motor vehicles. Consequent to this strict implementation, there is an observed 25% decrease in the frequency of occurrence of injuries in the respective car drivers.57 Another study showed that drivers and passengers who had their seat belts fastened at the moment of the accident had significantly lower severity of facial injuries compared with those who failed to take that safety precaution.58,59 Furthermore, the employment of air-bag systems is also an effective means in terms of decreasing the incidence of MFFs in motor vehicle users. Finally, it should be emphasised that the use of alcohol or stupefacient was the leading cause of facial injuries in over half of the patients involved in traffic accidents.60

Limitations

Incomplete records, missing patient data and improper reporting from patients.

CONCLUSION

Maxillofacial fractures are highly prevalent in the MENA region, and are mainly caused by RTAs, especially among young males. Therefore, it is imperative to implement strict traffic rules in order to minimise the risk of maxillofacial injuries, and the associated morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding

No funding for this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.The World Bank. The World Bank. 12 October 2017. Worldatlas.com/webimage/countrys/af.htm. Accessed 16 November 2019.

- 2.Klenk G, Kovacs A. Etiology and patterns of facial fractures in the United Arab Emirates. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:78–84. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200301000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Ahmed H, Jaber M, Abu Fanas S, et al. The pattern of maxillofacial fractures in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates: A review of 230 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdullah W, Al-Mutairi K, Al-Ali Y, et al. Patterns and etiology of maxillofacial fractures in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent J. 2013;25:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raval C, Rashiduddin M. Airway management in patients with maxillofacial trauma – a retrospective study of 177 cases. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:9–14. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.76476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Firas N, Taha S, Farag I. Pattern of traumatic maxillofacial injuries among the young adult Qatari population during the years 2006–2009. A retrospective study. Egypt J Ear Nose Throat Allied Sci. 2013;14:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al Sheikhly A. Pattern of trauma in the districts of Doha/Qatar: causes and suggestionsE3. J Med Res. 2012;1:25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alqahtani F, Bishawi K, Jaber M. Analysis of the pattern of maxillofacial injuries in Saudi Arabia: a systematic review. Saudi Dent J. 2019;32:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2019.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cenk D. Epidemiologic analysis and evaluation of complications in 1266 cases with maxillofacial trauma. Turk J Plast Surg. 2018;26:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramalingam S. Role of maxillofacial trauma scoring systems in determining the economic burden to maxillofacial trauma patients in India. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:38–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiu G, Bullock M, Edwards A. Industrial maxillofacial injuries in the United Kingdom. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:926–931. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Dajani M, Quinonez C, Macpherson AK, et al. Epidemiology of maxillofacial injuries in Ontario, Canada. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73 doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.12.001. 693.e1–693.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker TW, Byrne S, Donnellan J, et al. McCann PJ. West of Ireland facial injury study. Part 1. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50:631–635. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMullin BT, Rhee JS, Pintar FA, et al. Facial fractures in motor vehicle collisions: epidemiological trends and risk factors. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2009;11:165–170. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2009.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oji C. Jaw fractures in Enugu, Nigeria, 1985–95. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;37:106–109. doi: 10.1054/bjom.1997.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Infante Cossio P, EspinGalvez F, GutierrezPerez JL, et al. Mandibular fractures in children. A retrospective study of 99 fractures in 59 patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;23:329–331. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandra Shekar BR, Reddy C. A five-year retrospective statistical analysis of maxillofacial injuries in patients admitted and treated at two hospitals of Mysore city. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:304–308. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.44532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheema SA, Amin F. Incidence and causes of maxillofacial skeletal injuries at the Mayo Hospital in Lahore, Pakistan. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;44:232–234. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chrcanovic BR, Abreu MH, Freire-Maia B, et al. 1,454 Mandibular fractures: A 3-year study in a hospital in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shere JL, Boole JR, Holtel MR, et al. An analysis of 3599 midfacial and 1141 orbital blowout fractures among 4426 United States Army Soldiers, 1980–2000. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adi M, Ogden GR, Chisholm DM. An analysis of mandibular fractures in Dundee, Scotland (1977 to 1985) Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;28:194–199. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(90)90088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voss R. The etiology of jaw fractures in Norwegian patients. J Maxillofac Surg. 1982;10:146–148. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(82)80031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obuekwe O, Owotade F, Osaiyuwu O. Etiology and pattern of zygomatic complex fractures: A retrospective study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:992–996. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamulegeya A, Lakor F, Kabenge K. Oral maxillofacial fractures seen at a Ugandan tertiary hospital: A six-month prospective study. Clin (S Paulo) 2009;64:843–848. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000900004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawoyin DO, Lawoyin JO, Lawoyin TO. Fractures of the facial skeleton in Tabuk North West Armed Forces Hospital: a five-year review. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1996;25:385–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oikarinen K, Schutz P, Thalib L, et al. Differences in the etiology of mandibular fractures in Kuwait, Canada, and Finland. Dent Traumatol. 2004;20:241–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2004.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aldelaimi TN. Surgical management of maxillofacial injuries in Iraq. Int Open Access Dent Stud. 2012;2:113. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qudah M, Al-Khateeb T, Bataineh AB, et al. Mandibular fractures in Jordanians: a comparative study between young and adult patients. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2005;33:103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melek L, Sharara A. Retrospective study of maxillofacial trauma in Alexandria University: analysis of 177 cases. Tanta Dent J. 2016;13:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Almahdi H, Higzi M. Maxillofacial fractures among Sudanese children at Khartoum Dental Teaching Hospital. BMC Res Notes. 2016;23:9–120. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-1934-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elarbi M. Why is the aetiology of facial bone fractures in west of Libya different. Int J Dent Oral Sci. 2017;4:405–412. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1495–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Aanazi Y, Alrwuili K, Salfiti M, et al. Incidence of maxillofacial injuries reported in Al-Qurayyat General Hospital over a period of 3 years. Prensa Med Argent. 2016;102:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samman M, Ahmed S, Beshir H, et al. Incidence and pattern of mandible fractures in the Madinah region: a retrospective study. J Nat Sc Biol Med. 2018;9:59–64. doi: 10.4103/jnsbm.JNSBM_60_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosman D, Knuiman M. A comparison of hospital and police road injury data. Accid Anal Prev. 1994;26:215–222. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(94)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alghamdi S, Alhabab R, Alsalmi S. The epidemiology, incidence and patterns of maxillofacial fractures in Jeddah city, Saudi Arabia. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;46:32–36. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Khateeb T, Abdullah F. Craniomaxillofacial injuries in the United Arab Emirates: a retrospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1094–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atilgan S. Mandibular fractures; a comparative analysis between young and adult patients in the southeast region of Turkey. J Appl Oral Sci. 2010;18:1–4. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572010000100005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aldelaimi T. Surgical Management of Maxillofacial Injuries in Iraq. Dentistry. 2012;2:113. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-khawalde M. Maxillofacial fractures in Jordan; a 5 year retrospective review. J Oral Surg. 2011;4:161–165. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elarabi M, Bataineh A. Changing pattern and etiology of maxillofacial fractures during the civil uprising in Western Libya. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2018;23:e248–e255. doi: 10.4317/medoral.22268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Hoof R, Merkx C, Stekelenburg E. The different patterns of fractures of the facial skeleton in four European countries. Int J Oral Surg. 1977;6:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(77)80066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Afzelius L, Rosén C. Facial fractures. a review of 368 cases. Int J Oral Surg. 1980;9:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(80)80003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown R, Cowpe J. Patterns of maxillofacial trauma in two different cultures. A comparison between Riyadh and Tayside. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1985;30:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.King R, Scianna J, Petruzzelli G. Mandible fracture patterns: a suburban trauma center experience. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nwoku A. Retrospective analysis of 1206 maxillofacial fractures in an urban Saudi hospital: 8 year review. Pak Oral Dent J. 2004;24:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laski R, Ziccardi VB, Broder HL, et al. Facial trauma: a recurrent disease? The potential role of disease prevention. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:685–688. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ansari M. Maxillofacial fractures in Hamedan province, Iran: a retrospective study (1987–2001) J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2004;32:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gassner R, Tuli T, Hachl O, et al. Cranio-maxillofacial trauma: A 10 year review of 9,543 cases with 21,067 injuries. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003;31:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(02)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Allareddy V, Allareddy V, Nalliah R. Epidemiology of facial fracture injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2613–2618. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arslan E, Solakoglu A, Komut E, et al. Assessment of maxillofacial trauma in emergency department. World J Emerg Surg. 2014;9:13. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rezaei M, Jamshidi S, Jalilian T, et al. Epidemiology of maxillofacial trauma in a university hospital of Kermanshah, Iran. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2017;29:110–115. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rallis G, Stathopoulos P, Igoumenakis D, et al. Treating maxillofacial trauma for over half a century: how can we interpret the changing patterns in etiology and management? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2015;119:614–618. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Antoun J, Lee K. Sports-related maxillofacial fractures over an 11-year period. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:504–508. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wood E, Freer T. Incidence and aetiology of facial injuries resulting from motor vehicle accidents in Queensland for a three-year period. Aust Dent J. 2001;46:284–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2001.tb00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rogers S, Hill J, Mackay G. Maxillofacial injuries following steering wheel contact by drivers using seat belts. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;30:24–30. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(92)90132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peden M. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention.http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/road_traffic/world_report/summary_en_rev.pdf Available from: [Last accessed on 2019 Nov 16] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Henderson M, Wood R. Compulsory wearing of seatbelts in NSW, Australia – and evaluation of its effects on vehicle occupant deaths in the first year. Med J Aust. 1973;2:797–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nakhgevany K, LiBassi M, Esposito B. Facial trauma in motor vehicle accidents: etiological factors. Am J Emer Med. 1994;12:160–163. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(94)90237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hutchison I, Magennis P, Shepherd J, et al. The BAOMS United Kingdom survey of facial injuries part 1: etiology and the association with alcohol consumption. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(98)90739-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alqahtani A. Patterns of maxillofacial fractures associated with assault injury in Khamis Mushait city and related factors. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2018;70:325–328. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Al-Bokhamseen MS, Al-Bodbaij RM. Patterns of maxillofacial fractures in Hofuf, Saudi Arabia: A 10-year retrospective case series. Saudi Dent J. 2019;31:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jan A, Alsehaimy M, Al-Sebaei M, et al. A retrospective study of the epidemiology of maxillofacial trauma in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Am Sci. 2015;11:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Almasri M, Aboola D, Shargawi A. Maxillofacial fractures in Makka City in Saudi Arabia. An 8-year review of practice. Am J Public Health Res. 2015;3:56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alsehaimy M. A retrospective study of the epidemiology of maxillofacial trauma in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Am Sci. 2015;11:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Almasri M. Severity and causality of maxillofacial trauma in the southern region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent J. 2013;25:107–110. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elawad A. Facial injuries in Khartoum State. Khartoum Med J. 2012;5:688–693. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Al-Hammad Z, Yanal N, Sami A, et al. A cross-sectional study of the prevalence and severity of maxillofacial fractures resulting from motor vehicle accidents in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent J. 2019;09:009. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qudah M, Bataineh A. A retrospective study of selected oral and maxillofacial fractures in a group of Jordanian children. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:310–314. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.127406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rabi A, Khateery S. Maxillofacial trauma in Al Madinah region of Saudi Arabia: a 5-year retrospective study. Asian J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;14:10–14. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bataineh A. Etiology and incidence of maxillofacial fractures in the north of Jordan. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol. 1998;86:31–35. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jaber MA, Porter SR. Maxillofacial injuries in 209 Libyan children under 13 years of age. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1997;7:39–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263x.1997.tb00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Karyouti SM. Maxillofacial injuries at Jordan University Hospital. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;16:262–265. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(87)80145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kummoona R. Management of maxillofacial injuries in Iraq. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:1561–1566. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31822e5e7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zandi M, Khayati A, Lamei A, et al. Maxillofacial injuries in western Iran: a prospective study. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;15:201–209. doi: 10.1007/s10006-011-0277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Elgehani R, Orafi M. Incidence of mandibular fractures in Eastern part of Libya. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:e529–e532. doi: 10.4317/medoral.14.e529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]