Summary

The current COVID‐19 pandemic is caused by the SARS‐CoV‐2 coronavirus. The initial recognized symptoms were respiratory, sometimes culminating in severe respiratory distress requiring ventilation, and causing death in a percentage of those infected. As time has passed, other symptoms have been recognized. The initial reports of cutaneous manifestations were from Italian dermatologists, probably because Italy was the first European country to be heavily affected by the pandemic. The overall clinical presentation, course and outcome of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in children differ from those in adults, as do the cutaneous manifestations of childhood. In this review, we summarize the current knowledge on the cutaneous manifestations of COVID‐19 in children after thorough and critical review of articles published in the literature and from the personal experience of a large panel of paediatric dermatologists in Europe. In Part 1, we discussed one of the first and most widespread cutaneous manifestations of COVID‐19, chilblain‐like lesions. In this part of the review, we describe other manifestations, including erythema multiforme, urticaria and Kawasaki disease‐like inflammatory multisystemic syndrome. In Part 3, we discuss the histological findings of COVID‐19 manifestations, and the testing and management of infected children for both COVID‐19 and any other pre‐existing conditions.

Abstract

Click here for the corresponding questions to this CME article.

Introduction

The current COVID‐19 pandemic has affected almost all countries worldwide. The overall clinical presentation, course and outcome of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, as well as the cutaneous manifestations of childhood COVID‐19 differ from those of adults. Certain manifestations are more frequently seen in children and young patients. Below we describe some of the other manifestations of COVID‐19, including erythema multiforme (EM), urticaria and Kawasaki disease (KD)‐like inflammatory multisystemic syndrome.

Erythema multiforme

EM is an acute, self‐limiting hypersensitivity condition, which is characterized clinically by a distinctive skin eruption with symmetrical erythematous lesions called iris or target lesions.1, 2

The most common cause of EM is systemic infection (up to 90%), while drug‐associated EM is reported in < 10% of cases.3 In children, the two pathogens most frequently involved in EM are herpes simplex virus (HSV) and Mycoplasma pneumoniae.4

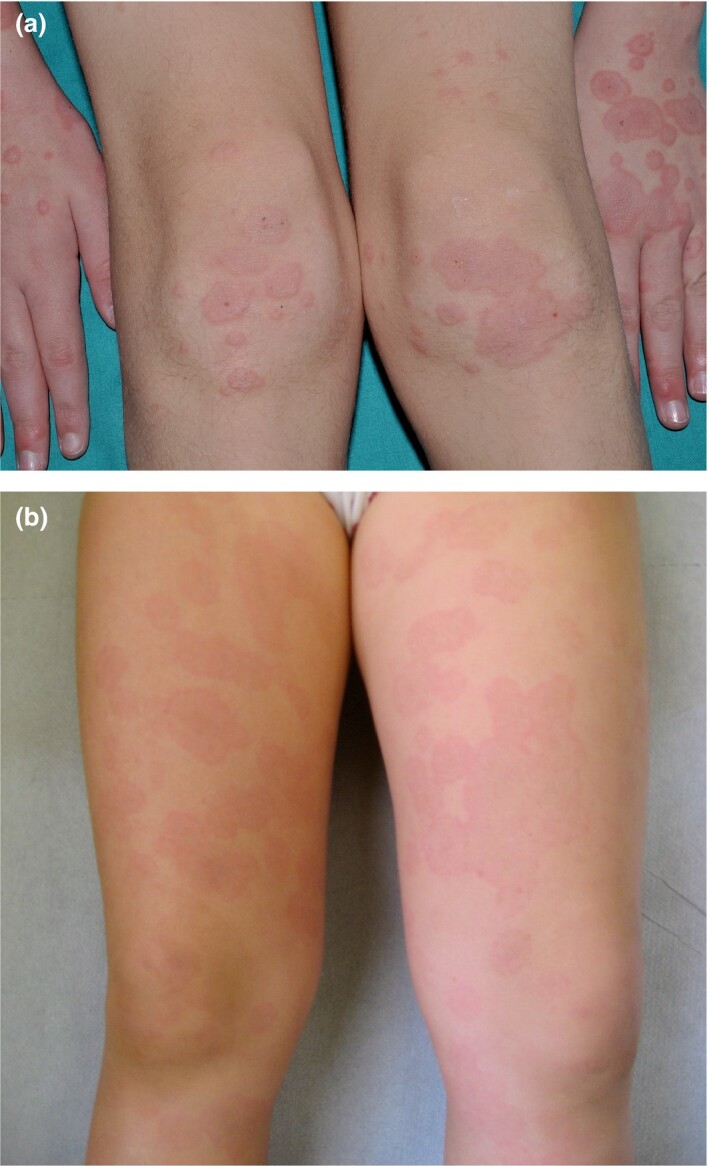

An EM‐like eruption has been observed in association with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, both in adults and in children5, 6 (Fig. 1). In one report7 a 17‐year‐old patient presented with discrete acral papules and targetoid lesions. In another report, four children (three boys and one girl) with chilblain‐like lesions also had associated EM, with both true target lesions and targetoid lesions; one of these patients had a positive PCR result for SARS‐CoV‐2, and skin biopsies carried out in two of the cases demonstrated endothelial positive immunohistochemistry stain to SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein.8 A 6‐year‐old boy with acral target lesions of EM and severe, painful cheilitis and conjunctivitis had a positive COVID‐19 PCR result.9 Other cases of EM‐like lesions on the heels of both feet in children can be better regarded as chilblains with central purpuric lesions and peripheral erythema.10

Figure 1.

(a,b) Typical targetand targetoid lesions in COVID‐19‐related erythema multiforme.

Children with EM in the setting of COVID‐19 have been otherwise asymptomatic or have had only mild respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms.8

Urticaria

Urticaria presents with usually pruritic, circumscribed, raised weals, which characteristically last < 24 h. The most common causes of urticaria are allergens, food pseudoallergens, insect envenomation, drugs and infections. Viruses are a common cause of urticaria in children,11 including parvovirus, rhinovirus, rotavirus, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), hepatitis A, B and C viruses, and human immunodeficiency virus, among others. Bacterial infections (urinary tract infections, Streptococcus, Mycoplasma, Helicobacter pylori) and some parasites can also be associated with urticaria.

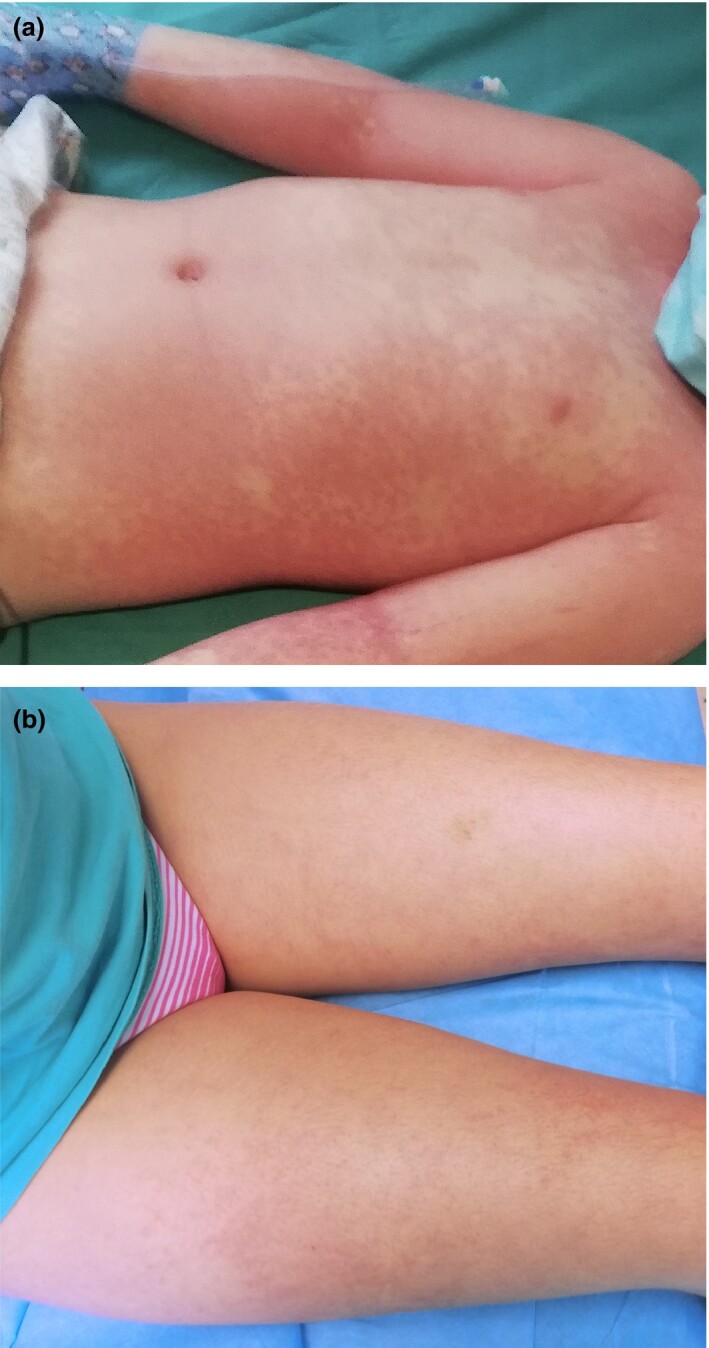

Urticaria represents about 10%–20% of the cutaneous manifestations in patients with COVID‐195, 12–24 (Fig. 2). Most reported cases of urticaria in COVID‐19 were adults, and in our experience, children with urticaria and COVID‐19 appear mostly asymptomatic apart from the urticarial rash. Additionally, most of the patients were not tested, but had household contact with confirmed or suspected patients with COVID‐19. Only a minority of patients were biopsied, all of them adults.13, 14

Figure 2.

Urticaria in a child with COVID‐19.

Viral infections may cause nonimmunological urticaria by mast cell activation via complement or vasculitis as COVID‐19 virus binds angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE)2 receptors on blood vessels. Antibodies may therefore deposit at vascular walls with ensuing immune reaction. Urticaria might be associated with bradykinin in the kinin–kallikrein system in conjunction with ACE2.15

Vesicular exanthem

There is no consensus regarding the definition of ‘COVID‐19 vesicular rash’.25–27 The vesicular exanthem was reported in 4% of 53 cases with dermatological symptoms and positive nasopharyngeal PCR for SARS‐Cov‐2 in a prospective multicentre study in China and Italy,28 in 9% of confirmed or suspected COVID‐19 cases with skin symptoms in Spain,5 and in 15% of suspected or confirmed cases in France.26

Initially, the vesicular eruption reported in patients diagnosed with COVID‐19 was a varicella‐like papulovesicular rash.28 This kind of rash may possibly be more frequent in middle‐aged women,5, 28 but it has also been reported in adult men and children. Vesicular lesions are thought to appear in the early stages of COVID‐19 disease, and occasionally even before the onset of other manifestations,5, 29 compared with other skin manifestations occurring later.30

The eruption is monomorphic27 with disseminated vesicles, appearing after a median latency of 3 days after first respiratory symptoms (Fig. 3) and persisting for around 8 days with no correlation with severity of infection.28, 31–33 Vesicles predominate on the trunk, but the limbs may also be affected34 and papular, crusted34 or haemorrhagic lesions35 are also associated. Itch is common, but is usually mild.28

Figure 3.

Vesicular exanthem of COVID‐19.

Most authors advise using PCR on vesicle fluid to test for HSV‐1 and HSV‐3 (varicella zoster virus; VZV) to exclude HSV and VZV. The histology of these also differs from that of COVID‐19 vesicular rash.24, 34, 36, 37

The pathogenesis of the vesicular exanthema is unknown and other viruses, such as HSV‐1, HSV‐2, human herpesvirus (HHV)‐6 and HHV‐7, VZV, parvovirus and EBV, have been simultaneously detected in some patients with COVID‐19.5, 32, 38

Kawasaki disease‐like inflammatory syndrome (paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome)

KD is the most common vasculitis in childhood39 and its diagnosis is based on clinical and laboratory criteria.40, 41 The role of a nonspecific infection, such as seasonal coronavirus, as a trigger factor is classically suggested.41–43

Although COVID‐19 affects children less severely than adults,44 a temporospatial association between COVID‐19 and a severe multisystemic condition has been observed in children in various countries.45–49 This has been named paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome (PIMS) temporally associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in Europe50 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in the USA.51

Around 40 articles have been published, including case reports (USA and Italy),52, 53 case series45 and two cohort studies.48

Demographics

The mean age of patients with PIMS is higher than that usually seen with classic KD, with age ranging from a mean ± SD 7.5 ± 3–547 to a median of 7.9 (range 3.7–16.6 years).48 In the French cohort,48 the proportion of patients with at least one parent originating from sub‐Saharan Africa or a Caribbean island was about 57%. This was also highlighted in patients with hyperinflammatory shock syndrome,40 with a high frequency of African‐American patients affected by more severe COVID‐19 forms.54, 55 In a French study, 14% of patients had at least one parent originating from Asia.49

Although overweight is a well‐known risk factor for complications of COVID‐19,44 overweight was not underlined as a risk factor in severe and fatal forms of COVID‐19 in children.56

Clinical features

According to the American Heart Association criteria of KD33 a complete form of KD was found in 50%–52% of cases,47, 48 and an incomplete form of the disease, according to the American Heart Association criteria57 was seen in 48%–50% of cases.47, 48 The diagnosis of incomplete types was based on fever for > 5 days plus two or three classic criteria, considering laboratory anomalies and/or abnormal echocardiography (coronary aneurysms, left ventricular depression, mitral valve regurgitation, pericardial effusion) as associated additional diagnostic criteria.47

Generally, however, in comparison with KD, children with PIMS display an over‐representation of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, myocarditis and shock syndrome. GI symptoms were found in a large proportion of patients. Diarrhoea was present in 60% of an Italian cohort47 and 100% of a French cohort,48 hence the predominance of GI symptoms could lead to diagnostic and therapeutic delay as well as unnecessary surgical interventions.

Cardiovascular symptoms including hypotension or signs of hypoperfusion were present in 50%–57% of cases in two studies,47, 48 and myocarditis in 76% of patients in the French series.48 Hyperinflammatory shock, showing similar features to atypical KD (KD shock syndrome; KDSS) have been described recently45 and was described in a French study.58

KDSS is a rare syndrome, affecting 1.5%–7% of patients with KD, and is characterized by myocardial dysfunction associated with decreased peripheral vascular resistance, and a severe inflammatory syndrome with high levels of IgE, C‐reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin.58 A higher incidence has been found in western countries, i.e. Europe and America .59

Skin and mucosal manifestations

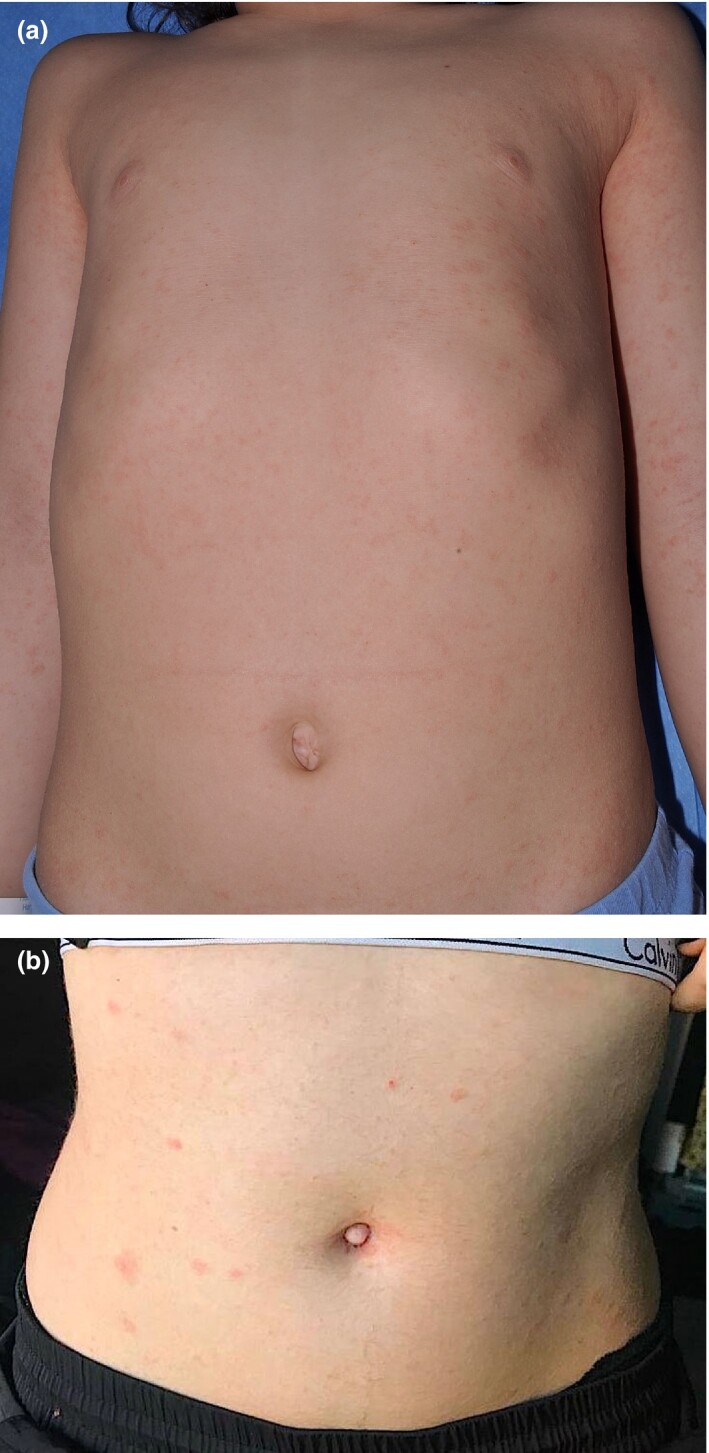

Currently, the cutaneous manifestations at the moment appear to be nonspecific to the pathogenesis, being similar to those usually described in KD or in viral infections (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

(a,b) Erythmatous exanthem in paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome.

Cutaneous and mucosal manifestations are common in PIMS.46–48 A nonexudative conjunctivitis was described in 50% of Italian patients with the complete form and 30% with the incomplete form,47 and in 81% of French patients.48 A ‘polymorphic’ rash was seen in 50% of Italian patients with the complete form and 30% with the incomplete form,47 and in 76% and 20% of French patients with the complete and incomplete forms, respectively.48 Perineal or face desquamation was observed in 19% of French patients.48 Finally, hand and feet anomalies (erythema, firm induration or both) were described in 50% of Italian patients47 and 48% of French patients.48 The semiology of the cutaneous lesions had no apparent specificity.

Laboratory studies

Inflammatory markers, including CRP, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, neutrophil count and ferritin were elevated in almost all cases, and pancytopenias have also been described along with other biochemical derangements.47, 48 Median interleukin‐6 level was shown to be elevated48 and cytokine storm has been reported.49, 60, 61

Echocardiography

In the Italian study,47 60% had abnormal heart ultrasonography results, including aneurysms (20%), decreased ejection fraction (50%), mitral valve regurgitation anomalies (40%) and pericardial effusion (40%). In the French study,48 38% of patients had coronary artery abnormalities including dilatations and increased coronary visibility, but no coronary aneurysms.

Evidence of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection

The incidence of KD in 2020 has been much higher than expected and the number of severe cases of KD has been higher than at any time in the past 5 years.47 Other members of the coronavirus family (such as HCoV‐NH, very similar to HCOV‐NL63) have previously been suspected to trigger or cause KD.41–43,62–64

In children with KD‐like multisystem inflammatory syndrome during the COVID‐19 pandemic, reverse transcription‐PCR was positive in only 20%–38% of patients,47, 48 and IgG serology testing was positive in 80%–90%.47, 48 There are of course caveats with serology testing.65

Treatment

During the pandemic, > 80% of paediatric patients required admission to an intensive care unit48 and received intravenous fluid resuscitation and/or vasoactive agents, plus systemic antibiotics.65, 66 All patients received aspirin (low‐ or high‐dose) at admission and discharge, and were also treated with high‐dose intravenous immunoglobulin infusion 2 g/kg, while over half required adjunctive steroids (methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg/day).47, 48

Other manifestations

Several nonspecific viral exanthems have been putatively attributed to SARS‐CoV‐2. Vasculopathic rashes including purpuric thrombocytopenic purpura,67 Dengue‐like exanthem,68, 69 acro‐ischaemia70 and livedoid eruptions5, 71 have been linked to COVID‐19 in adults and occasionally in children as well72, 73 (Fig. 5). As in other viral exanthems, a tendency for flexural involvement has been reported.69, 74 Histological findings range from thrombotic vasculopathy75 to perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with abundant red cell extravasation and dermal oedema without vascular occlusion,76 pointing to a paucisymptomatic inflammatory peripheral vasculopathy as the basic pathogenic mechanism.

Figure 5.

Purpuric rash in a child with suspected COVID‐19.

Maculopapular exanthems were reported in 47% of Spanish adult patients with skin manifestations (but 78% were on one or more drug)5 and in 14 out of 18 Italian cases77 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Maculopapular exanthemin COVID‐19.

Pathology findings (see Part 3 of this series) do not differ from those of other viral infections and drug eruptions.78, 79 Despite thousands of patients with COVID‐19 receiving therapy, available data on the prevalence of drug eruptions are lacking and only anecdotal reports suggesting such a possibility have been published to date.69, 80 Similarly, pityriasis rosea‐like eruptions have been widely reported,5, 81 but whether this is a specific COVID‐19 eruption or whether it is due to a reactivation of HHV‐682 is not known (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

(a,b) Pityriasis rosea‐like eruption intwo childrenwith suspected COVID‐19.

Oral mucosa findings have received little attention in all age groups. In a recent study performed in a field hospital in Spain, up to 25% of patients showed oral mucosa abnormalities, 18% of which had macroglossia and anterior papillitis 83. A 12‐year‐old girl with tongue swelling and prominent papillae with positive COVID‐19 PCR test has been reported,72 further supporting the potential involvement of the oral cavity in patients with COVID‐19.

Some of these rashes may not be directly related to SARS‐CoV‐2,84 and other aetiologies of cutaneous rashes should be kept in mind85even during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Learning points.

Lesions indistinguishable from EM may occur in association with chilblains in children suspected of COVID‐19.

Urticaria occurs in 10%–20% of patients with skin lesions in COVID‐19, and its incidence may be underestimated in children.

A monomorphic vesicular or papulovesicular, disseminated exanthema has been described both in patients with PCR‐proven and those with suspected COVID‐19, mostly in adults.

PIMS is a rare, but most severe form of COVID‐19 in children; it resembles severe KDSS and presents with skin lesions that may mimic KD.

Other forms of exanthems, whose relation to COVID‐19 is unknown, have been reported during the COVID‐19 outbreak; these include purpuric rashes, maculopapular exanthems, pityriasis rosea‐like eruptions and oral findings, among others.

Contributor Information

D. Andina, Department of Dermatology Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús Madrid Spain

A. Belloni‐Fortina, Pediatric Dermatology Unit Department of Medicine DIMED University of Padua Padua Italy

C. Bodemer, Department of Dermatology Hospital Necker Enfants MaladesParis Centre University Paris France

E. Bonifazi, Dermatologia Pediatrica Association Bari Italy

A. Chiriac, Nicolina Medical Center Iasi Romania

I. Colmenero, Department of Pathology Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús Madrid Spain

A. Diociaiuti, Dermatology Unit Bambino Gesù Children’s HospitalIRCCS Rome Italy

M. El‐Hachem, Dermatology Unit Bambino Gesù Children’s HospitalIRCCS Rome Italy

L. Fertitta, Department of Dermatology Hospital Necker Enfants MaladesParis Centre University Paris France

van D. Gysel, Department of Pediatrics O. L. Vrouw Hospital Aalst Belgium.

A. Hernández‐Martín, Department of Dermatology Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús Madrid Spain

T. Hubiche, Department of Dermatology Université Côte d'Azur Nice France

C. Luca, Nicolina Medical Center Iasi Romania

L. Martos‐Cabrera, Department of Dermatology Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús Madrid Spain

A. Maruani, Department of Dermatology Unit of Pediatric Dermatology University of ToursSPHERE‐INSERM1246, CHRU Tours Tours France

F. Mazzotta, Dermatologia Pediatrica Association Bari Italy

A. D. Akkaya, Department of Dermatology Ulus Liv Hospital Istanbul Turkey

M. Casals, Department of Dermatology Hospital Universitari de Sabadell Barcelona Spain

J. Ferrando, Department of Dermatology Hospital Clìnic Barcelona Spain

R. Grimalt, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Universitat Internacional de Catalunya Barcelona Spain

I. Grozdev, Department of Dermatology Children's University Hospital Queen Fabiola Brussels Belgium

V. Kinsler, Department of Paediatric Dermatology Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust London UK

M. A. Morren, Pediatric Dermatology Unit Department of Pediatrics and Dermato‐Venereology University Hospital Lausanne and University of Lausanne Lausanne Switzerland

M. Munisami, Department of Dermatology and Sexually Transmitted Diseases Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER) Puducherry India

A. Nanda, As'ad Al‐Hamad Dermatology Center Kuwait City Kuwait

M. P. Novoa, Department of Dermatology Hospital San Jose Bogota Colombia

H. Ott, Division of Pediatric Dermatology Children’s Hospital Auf der Bult Hannover Germany

S. Pasmans, Erasmus MC University Medical Center RotterdamSophia Children's Hospital Rotterdam The Netherlands

C. Salavastru, Department of Paediatric Dermatology Colentina Clinical HospitalCarol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy Bucharest Romania

V. Zawar, Department of Dermatology Dr Vasantrao Pawar Medical College Nashik India

A. Torrelo, Department of Dermatology Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús Madrid Spain.

CPD questions

Learning objective

To gain up‐to‐date knowledge about rarer manifestations of COVID‐19‐related skin diseases.

Question 1

Which of the following statements about erythema multiforme in the setting of COVID‐19 is true?

(a) Lesions are mostly located on the face and trunk.

(b) Lesions sometimes appear in association with chilblains.

(c) A positive PCR result to SARS‐CoV‐2 has been reported in the majority of these cases.

(d) All patients reported to date had systemic symptoms of COVID‐19.

(e) It has a severe and prolonged course.

Question 2

Which of the following is the most common skin manifestation in patients with COVID‐19?

(a) Chilblains.

(b) Urticaria.

(c) Vesicular exanthem.

(d) Maculopapular eruption.

(e) Purpuric exanthem.

Question 3

Which of the following skin signs is not characteristic of paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome?

(a) Nonexudative conjunctivitis.

(b) Erythematous rash.

(c) Splinter haemorrhage of the fingernails.

(d) Perineal desquamation.

(e) Hand erythema and induration.

Question 4

Which of the following signs is more frequent in paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome than in Kawasaki disease?

(a) Prominent gastrointestinal symptoms.

(b) Myocarditis.

(c) Shock.

(d) All of the above.

(e) None of the above.

Question 5

Which of the following skin manifestations has not been reported to be linked to COVID‐19?

(a) Lichen planus.

(b) Livedoid eruptions.

(c) Pityriasis rosea.

(d) Macroglossia.

(e) Retiform purpura.

Instructions for answering questions

This learning activity is freely available online at http://www.wileyhealthlearning.com/ced

Users are encouraged to

Read the article in print or online, paying particular attention to the learning points and any author conflict of interest disclosures.

Reflect on the article.

Register or login online at http://www.wileyhealthlearning.com/ced and answer the CPD questions.

Complete the required evaluation component of the activity.

Once the test is passed, you will receive a certificate and the learning activity can be added to your RCP CPD diary as a self‐certified entry.

This activity will be available for CPD credit for 2 years following its publication date. At that time, it will be reviewed and potentially updated and extended for an additional period.

References

- Grünwald P, Mockenhaupt M, Panzer R, Emmert S. Erythema multiforme, Stevens‐Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis – diagnosis and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2020; 18: 547–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French LE, Prins C. Erythema multiforme, Stevens‐Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Dermatology, 3rd edn (Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, ed). Atlanta: Elsevier Saunders, 2012; 319–33. [Google Scholar]

- Siedner‐Weintraub Y, Gross I, David A et al. Paediatric erythema multiforme: epidemiological, clinical and laboratory characteristics. Acta Derm Venereol 2017; 97: 489–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol 2012; 51: 889–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID‐19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol 2020; 183: 71–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez‐Cauhe J, Ortega‐Quijano D, Carretero‐Barrio I et al. Erythema multiforme‐like eruption in patients with COVID‐19 infection: clinical and histological findings. Clin Exp Dermatol 2020; 45: 892–5. 10.1111/ced.14281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janah H, Zinebi A, Elbenaye J. Atypical erythema multiforme palmar plaques lesions due to SARS‐CoV‐2. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e373–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrelo A, Andina D, Santonja C et al. Erythema multiforme‐like lesions in children and COVID‐19. Pediatr Dermatol 2020; 37: 442–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labé P, Ly A, Sin C et al. Erythema multiforme and Kawasaki disease associated with COVID‐19 infection in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e539–41. 10.1111/jdv.16666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García‐Gil MF, García García M, Monte Serrano J et al. Acral purpuric lesions (erythema multiforme type) associated with thrombotic vasculopathy in a child during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34. 10.1111/jdv.16644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbalzano E, Casciaro M, Quartuccio S et al. Association between urticaria and virus infections: a systematic review. Allergy Asthma Proc 2016; 37: 18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID‐19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci 2020; 98: 75–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez‐Nieto D, Ortega‐Quijano D, Segurado‐Miravalles G et al. Comment on: Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: a first perspective. Safety concerns of clinical images and skin biopsies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e252–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez‐Jimenez P, Chicharro P, De Argila D et al. Urticaria‐like lesions in COVID‐19 patients are not really urticaria – a case with clinicopathologic correlation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 42: 564–70. 10.1111/jdv.16618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan C, Angela A, Widysanto A. Urticarial eruption in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) infection: a case report in Tangerang. Indonesia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e372–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JJ, Dong X, Cao YY et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy 2020; 75: 1730–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry D, Ackerman M, Sancelme E et al. Urticarial eruption in COVID‐19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e244–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aktas H, Hamidi AA. Urticaria in a patient with COVID‐19: therapeutic and diagnostic difficulties. Dermatol Ther 2020; e13610. 10.1111/dth.13610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Medeiros VLS, Silva LFT. Follow‐up of skin lesions during the evolution of COVID‐19: a case report. Arch Dermatol Res 2020; 1–4. 10.1007/s00403-020-02091-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naziroglu T, Sozen S, Ozkan P et al. A case of COVID‐19 pneumonia presenting with acute urticaria. Dermatol Ther 2020; e13575. 10.1111/dth.13575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damme C, Berlingin E, Saussez S, Accaputo O. Acute urticaria with pyrexia as the first manifestations of a COVID‐19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 334: e300–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estebanez A, Perez‐Santiago L, Silva E et al. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: a new contribution. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e250–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedou M, Carsuzaa F, Chary E et al. Comment on "Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: a first perspective" by Recalcati S. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e299–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey‐Olive M, Espiau M, Mercadal‐Hally M et al. Cutaneous manifestations in the current pandemic of coronavirus infection disease (COVID 2019). An Pediatr (Engl Ed) 2020; 92: 374–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S, Fernandez AP. Skin manifestations of COVID‐19. Cleve Clin J Med 2020. 10.3949/ccjm.87a.ccc031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson de A, Bouaziz JD, Sulimovic L et al. Chilblains are a common cutaneous finding during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a retrospective nationwide study from France. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83: 667–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisondi P, PIaserico S, Bordin C et al. Cutaneous manifestations of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a clinical update. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020. 10.1111/jdv.16774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzano AV, Genovese G, Fabbrocini G et al. Varicella‐like exanthema as a specific COVID‐19‐associated skin manifestation: multi‐center case series of 22 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83: 280–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Giorgi V, Recalcati S, Jia Z et al. Cutaneous manifestations related to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): a prospective study from China and Italy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83: 674–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez‐Nieto D, Ortega‐Quijano D, Jimenez‐Cauhe J et al. Clinical and histological characterization of vesicular COVID‐19 rashes: a prospective study in a tertiary care hospital. Clin Exp Dermatol 2020; 45: 872–5. 10.1111/ced.14277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzano AV, Genovese G. Response to “Reply to ‘Varicella‐like exanthem as a specific COVID‐19‐associated skin manifestation: multicenter case series of 22 patients’: To consider varicella‐like exanthem associated with COVID‐19, virus varicella zoster and virus herpes simplex must be ruled out”. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83: e255–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang K, Wang Y, Zhang H et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19): a brief review. Dermatol Ther 2020; e13528. 10.1111/dth.13528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianotti R, Veraldi S, Recalcati S et al. Cutaneous clinico‐pathological findings in three COVID‐19‐positive patients observed in the metropolitan area of Milan, Italy. Acta Derm Venereol 2020; 100: adv00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese G, Colonna C, Marzano AV. Varicella‐like exanthem associated with COVID‐19 in an 8‐year‐old girl: a diagnostic clue? Pediatr Dermatol 2020; 37: 435–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo V, Neri I, Filippeschi C et al. Chilblain‐like lesions during COVID‐19 epidemic: a preliminary study on 63 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e29–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollina U, Karadağ AS, Rowland‐Payne C et al. Cutaneous signs in COVID‐19 patients: a review. Dermatol Ther 2020; e13549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahé A, Birckel A, Merklen C et al. Histology of skin lesions establishes that the vesicular rash associated with COVID‐19 is not ‘varicella‐like’. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e559––61.. 10.1111/jdv.16706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahe A, Birckel E, Krieger S et al. A distinctive skin rash associated with coronavirus disease 2019. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e246–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel A, Hedrich CM. Childhood vasculitis. Front Pediatr 2018; 6: 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino N, Nakamura Y, Yashiro M et al. Nationwide epidemiologic survey of Kawasaki disease in Japan, 2015–16. Pediatr Int Off J Jpn Pediatr Soc 2019; 61: 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esper F, Shapiro ED, Weibel C et al. Association between a novel human coronavirus and Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis 2005; 191: 499–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esper F, Weibel C, Ferguson D et al. Evidence of a novel human coronavirus that is associated with respiratory tract disease in infants and young children. J Infect Dis 2005; 191: 492–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L‐Y, Lu C‐Y, Shao P‐L et al. Viral infections associated with Kawasaki disease. J Formos Med Assoc Taiwan Yi Zhi 2014; 113: 148–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y et al. Epidemiology of COVID‐19 among children in China. Pediatrics 2020; 145: e20200702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez‐Martinez C et al. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID‐19 pandemic. Lancet (Lond) Engl 2020; 39: 1607–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrero‐Hernández M, García‐Salido A, Leoz‐Gordillo I et al. Severe SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in children with suspected acute abdomen: a case series from a tertiary hospital in Spain. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2020; 39: e195–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdoni L, Mazza A, Gervasoni A et al. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki‐like disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS‐CoV‐2 epidemic: an observational cohort study. Lancet (Lond) Engl 2020; 395: 1771–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toubiana J, Poirault C, Corsia A et al. Kawasaki‐like multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children during the covid‐19 pandemic in Paris, France: prospective observational study. BMJ 2020; 369: m2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trouillet‐Assant S, Viel S, Gaymard A et al. Type I IFN immunoprofiling in COVID‐19 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020; 146: 206–8.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECDC. Paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome and SARSCoV‐ 2 infection in children, 2020. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/covid‐19‐riskassessment‐paediatricinflammatory‐multisystem‐syndrome‐15‐May‐2020.pdf (accessed 15 May 2020).

- CDC. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS‐C) associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), 2020. Available at: https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2020/han00432.asp (accessed 14 May 2020).

- Jones VG, Mills M, Suarez D et al. COVID‐19 and Kawasaki disease: novel virus and novel case. Hosp Pediatr 2020; 10: 537–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licciardi F, Pruccoli G, Denina M et al. SARS‐CoV‐2‐Induced Kawasaki‐like hyperinflammatory syndrome: a novel COVID phenotype in children. Pediatrics 2020; 146: e20201711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy CW. COVID‐19 and African Americans. JAMA 2020; 323: 1891–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giudicessi JR, Roden DM, Wild A, Ackerman MJ. Genetic susceptibility for COVID‐19‐associated sudden cardiac death in African Americans. Heart Rhythm 2020; 17: 1487–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oualha M, Bendavid M, Berteloot L et al. Severe and fatal forms of COVID‐19 in children. Arch Pediatr 2020; 27: 235–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW. et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long‐term management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017; 135: e927–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaud M, Starck J, Levy M et al. Acute myocarditis and multisystem inflammatory emerging disease following SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in critically ill children. Ann Intensive Care 2020; 10: 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zheng Q, Zou L et al. Kawasaki disease shock syndrome: clinical characteristics and possible use of IL‐6, IL‐10 and IFN‐γ as biomarkers for early recognition. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2019; 17: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M et al. COVID‐19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet (Lond) Engl 2020; 395: 1033–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395: 497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnier JL, Anderson MS, Heizer HR et al. Concurrent respiratory viruses and Kawasaki disease. Pediatrics 2015; 136: 609–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirato K, Imada Y, Kawase M et al. Possible involvement of infection with human coronavirus 229E, but not NL63, in Kawasaki disease. J Med Virol 2014; 86: 2146–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara T, Endo R, Ma X et al. Lack of association between New Haven coronavirus and Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis 2005; 19: 351–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder AR, Wilson KM, Ralston SL. COVID‐19 and Kawasaki disease: finding the signal in the noise. Hosp Pediatr 2020; 10: e1–3. 10.1542/hpeds.2020-000356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanegaye JT, Wilder MS, Molkara D et al. Recognition of a Kawasaki disease shock syndrome. Pediatrics 2009; 123: 783–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulfiqar AA, Lorenzo‐Villalba N, Hassler P, Andrès E. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura in a patient with Covid‐19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joob B, Wiwanitkit V. COVID‐19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for Dengue. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82: e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez‐Cauhe J, Ortega‐Quijano D, Prieto‐Barrios M et al. Reply to "COVID‐19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for Dengue": Petechial rash in a patient with COVID‐19 infection. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 8: e141–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Cao W, Xiao M et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID‐2019 pneumonia and acro‐ischemia. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2020; 41: E006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouaziz JD, Duong T, Jachiet M et al. Vascular skin symptoms in COVID‐19: a French observational study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34. 10.1111/jdv.16544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olisova OY, Anpilogova EM, Shnakhova LM. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: a skin rash in a child. Dermatol Ther 2020; e13712. 10.1111/dth.13712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamali Aghdam M, Jafari N, Eftekhari K. Novel coronavirus in a 15‐day‐old neonate with clinical signs of sepsis, a case report. Infect Dis (Lond) 2020; 183: 591–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JH. Febrile illness with skin rashes. Infect Chemother 2015; 47: 155–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llamas‐Velasco M, Muñoz‐Hernández P, Lázaro‐González J et al. Thrombotic occlusive vasculopathy in skin biopsy from a livedoid lesion of a COVID‐19 patient. Br J Dermatol 2020; 183: 591–3. 10.1111/bjd.19222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz‐Guimaraens B, Dominguez‐Santas M, Suarez‐Valle A et al. Petechial skin rash associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol 2020; 156: 820. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e212–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero‐Moyano M, Capusan TM, Andreu‐Barasoain M et al. A clinicopathological study of 8 patients with COVID‐19 pneumonia and a late‐onset exanthema. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020. 10.1111/jdv.16631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymundo A, Fernáldez‐Bernáldez A, Reolid A et al. Clinical and histological characterization of late appearance maculopapular eruptions in association with the coronavirus disease 2019. A case series of seven patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020: 10.1111/jdv.16707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaleu J, Deniau B, Battistella M et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by hydroxychloroquine prescribed for COVID‐19. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020; 8: 2777–9.e1. 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehsani AH, Nasimi M, Bigdelo Z. Pityriasis rosea as a cutaneous manifestation of COVID‐19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34. 10.1111/jdv.16579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dursun R, Temiz SA. The clinics of HHV‐6 infection in COVID‐19 pandemic: pityriasis rosea and Kawasaki disease. Dermatol Ther 2020; e13730. 10.1111/dth.13730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuno‐Gonzalez A, Martin‐Carrillo P, Magaletsky K, et al. Prevalence of mucocutaneous manifestations, oral and palmoplantar findings in 666 patients with COVID‐19 in a field hospital in Spain. Br J Dermatol. 2020;https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7537506/pdf/BJD‐9999‐na.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartari F, Spadotto A, Zengarini C et al. Herpes zoster in COVID‐19‐positive patients. Int J Dermatol 2020; 59: 1028–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llamas‐Velasco M, Rodríguez‐Jiménez P, Chicharro P et al. Reply to "Varicella‐like exanthem as a specific COVID‐19‐associated skin manifestation: multicenter case series of 22 patients": To consider varicella‐like exanthem associated with COVID‐19, virus varicella zoster and virus herpes simplex must be ruled out. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83: e253–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]