Abstract

The actions of cyclomaltodextrin glucanotransferases (CGTase; EC 2.4.1.19) from alkalophilic Bacillus sp. strain A2-5a (A2-5a CGTase), Bacillus macerans (Bmac CGTase), and Bacillus stearothermophilus (Bste CGTase) on amylose were investigated. All three enzymes produced large cyclic α-1,4-glucans (cycloamyloses) at the early stage of the reaction, but these were subsequently converted into smaller cycloamyloses. However, the rates of this conversion differed among the three enzymes. The product specificity of each CGTase in the cyclization reaction was determined by measuring the amount of each cycloamylose from CD6 to CD31 (CDn, a cycloamylose with a degree of polymerization of n). A2-5a CGTase produced 10 times more CD7, while Bmac CGTase produced 34 times more CD6 than other cycloamyloses. Bste CGTase produced 12 and 3 times more CD6 and CD7 than other cycloamyloses, respectively. The substrate specificities of the linearization reactions of CD6, CD7, CD8, and larger cycloamyloses (a mixture of CD22 to CD50) were investigated, and we found that CD7 and CD8 are extremely poor substrates for both hydrolytic and transglycosidic linearization (coupling) reactions while larger cycloamyloses are linearized at a much higher rate. By repeating these cyclization and linearization reactions, the larger cycloamyloses initially produced are converted into smaller cycloamyloses and finally into mainly CD6, CD7, and CD8. These three enzymes also differ in their hydrolytic activities, which seem to accelerate the conversion of larger cycloamyloses into smaller cycloamyloses.

Cyclomaltodextrin glucanotransferase (CGTase; EC 2.4.1.19) plays a role in the starch utilization pathway of some bacteria (2) and catalyzes various glucan transfer reactions with starch. The action of CGTase starts with the cleavage of one α-1,4-linkage within the glucan molecule. The newly produced reducing end is then transferred either to the nonreducing end of another molecule (disproportionation reaction) or to its own nonreducing end (cyclization reaction). CGTase also catalyzes the reverse reaction of cyclization, in which cycloamylose is opened by the enzyme and a linearized fragment is transferred to an acceptor (coupling reaction). At a certain frequency, the newly produced reducing end is transferred not to a carbohydrate acceptor but rather to a water molecule, which results in either the hydrolysis of amylose or the linearization of cycloamyloses (hydrolytic reaction).

CGTase was first observed to be produced by Bacillus macerans (31) and has since been found in many bacteria (5, 9, 26, 32). All CGTases produce mainly cycloamyloses with degrees of polymerization (DP) of 6, 7, and 8 (CD6, CD7, and CD8), which are generally called α-, β-, and γ-cyclomaltodextrin, at equilibrium but with different product specificities (i.e., different amounts of CD6, CD7, and CD8). These cyclomaltodextrins can complex various inorganic or organic compounds in their hydrophobic central cavities (20). Therefore, these cyclomaltodextrins are widely used in the pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic industries (21, 24). Since each cyclomaltodextrin has a distinct spectrum for guest molecules (13), extensive studies have been carried out to understand the mechanism of the cyclization reaction (1, 16, 17, 22, 25, 33–35) and to find or engineer CGTases to produce specific types of cyclomaltodextrin (18, 23, 36–38).

Although CD6, CD7, and CD8 are its main products at equilibrium, CGTase also produces larger cycloamyloses with DP of from 9 to more than 60 (30). Therefore, to understand the reaction mechanism of CGTase, these larger cycloamyloses must also be considered. Recently, we established a method for quantifying CD6 to CD31 by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography (HPAEC) and showed that this method could be useful for understanding the cyclization reaction of CGTase (10). In the present study, this method was used to investigate the actions of three different CGTases: CGTase from B. macerans (Bmac CGTase), which produces mainly CD6 (4); CGTase from alkalophilic Bacillus sp. strain A2-5a (A2-5a CGTase), which produces mainly CD7 (11); and CGTase from Bacillus stearothermophilus (Bste CGTase), which produces nearly equal amounts of CD6 and CD7 (4). Based on our findings, we propose a model of how cycloamyloses are produced by these CGTases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and enzymes.

Synthetic amyloses with average molecular masses of 110 and 30 kDa (amyloses AS-110 and AS-30) were purchased from Nakano Vinegar Co., Ltd. (Aichi, Japan). Glucoamylase from Rhizopus sp. was purchased from Toyobo Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), and α-amylase from porcine pancreas was purchased from Sigma. CGTases from the alkalophilic Bacillus sp. strain A2-5a (11) and B. macerans (4) were purified to homogeneity. Purified CGTase from B. stearothermophilus was obtained from Hayashibara Biochemical Laboratories Inc. (Okayama, Japan). A cycloamylose mixture containing CD22 to CD50 was prepared from synthetic amylose by amylomaltase from Thermus aquaticus ATCC 33923, as previously described (29). Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd. (Osaka, Japan).

General CGTase assay (iodine method).

The activity of CGTase was assayed using amylose AS-30 as a substrate by measuring the decrease in iodine-staining power. Amylose AS-30 (0.2 g) was dissolved in 10 ml of 90% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). A reaction mixture (100 μl) containing 25 μl of amylose solution, 5 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5), and CGTase was incubated at 40°C for 10 min. To this reaction mixture was added 2 ml of 0.01% I2 and 0.1% KI in 3.8 mM HCl, and the absorbance at 660 nm was measured. One unit of enzyme was defined as the amount of the enzyme that produced a 1% reduction in A660 per min under the conditions described.

Coupling (transglycosidic linearization) activity.

To assay the coupling activity of CGTase, cycloamylose and glucose were used as the donor and acceptor substrates, respectively. In the coupling reaction, cycloamyloses are linearized and then transferred to glucose to produce maltodextrins and amylose. As a result, the amount of glucose is reduced. Therefore, the coupling activity was assayed by measuring the decrease in the amount of glucose. A reaction mixture (100 μl) containing 0.5% (wt/vol) of a donor substrate, 0.02% (wt/vol) glucose, and CGTase in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) was incubated at 40°C for 10 min and then boiled for 10 min to terminate the reaction. The amount of glucose in the reaction mixture was measured by the glucose oxidase method (15). One unit of enzyme was defined as the amount of the enzyme that reduced 1 μmol of glucose per min.

Hydrolytic activity.

The hydrolytic activity of CGTase was assayed by measuring the increase in reducing power using α-, β-, and γ-cyclomaltodextrin and a cycloamylose mixture as a substrate. A reaction mixture (100 μl) containing 0.5% (wt/vol) cycloamylose and CGTase in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) was incubated at 40°C for 10 min and then boiled for 10 min to terminate the reaction. The reducing power of the reaction mixture was determined by a modified Park-Johnson method (28). One unit of enzyme was defined as the amount of the enzyme that produced reducing power equal to 1 μmol of glucose per min.

HPAEC.

To analyze the prolonged and initial reactions of CGTase, HPAEC was carried out using a BioLC 4000i system (Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, Calif.) with a pulsed amperometric detector (model PAD-II; Dionex) and using a DX-300 system (Dionex) with a pulsed amperometric detector (model PED-II; Dionex), respectively. The column was a CarboPac PA-100 (4 by 250 mm; Dionex). A sample (25 μl), containing maltopentaose (G5) as an internal standard, was injected and eluted with a linear gradient of sodium nitrate (0 to 2 min, 8 mM; 2 to 22 min, increasing from 8 to 16 mM; 22 to 38 min, increasing from 16 to 18 mM; 38 to 49 min, increasing from 18 to 36 mM; 49 to 69 min, increasing from 36 to 56 mM; 69 to 80 min, increasing from 56 to 64 mM; and 80 to 85 min, increasing from 64 to 200 mM) in 150 mM NaOH with a flow rate of 1 ml/min. CD6 to CD31 were quantified as described previously (10).

Analysis of CGTase action on amylose.

Amylose AS-110 (0.2 g) was dissolved in 10 ml of 90% (vol/vol) DMSO. To remove the DMSO, 0.5 ml of amylose solution was mixed with 0.5 ml of distilled water and loaded on a PD-10 column (7.6 by 50 mm; Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). After the column was washed with 2 ml of distilled water, the amylose was eluted with 1.5 ml of distilled water and then used immediately. To avoid retrogradation of the amylose, all procedures were conducted at 80°C. A reaction mixture (2 ml) containing 170 U of CGTase (1.8 μg of A2-5a CGTase, 0.47 μg of Bmac CGTase, and 1.5 μg of Bste CGTase) and 0.72 ml of amylose solution was incubated at 40°C, and the reaction was then terminated by boiling the solution for 10 min. The reaction mixture (200 μl) was incubated with glucoamylase (5.4 U) or glucoamylase (5.4 U) and α-amylase (0.78 U) at 40°C for 3 h. After the reaction was terminated by boiling the solution for 5 min, the released glucose was measured by the glucose oxidase method (15). The amount of total cycloamylose was calculated by subtracting the amount of glucose released by glucoamylase from that released by glucoamylase and α-amylase. The reducing power of the reaction mixture was measured by a modified Park-Johnson method (28) before glucoamylase treatment. The amounts of cycloamyloses were quantified by HPAEC.

To quantify CD6 to CD31 at the initial stage in the reaction with CGTase, the cycloamyloses in reaction mixtures were concentrated before HPAEC analysis. A reaction mixture (22 ml) containing 0.15% (wt/vol) amylose AS-110, 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5), and a CGTase, which converted 20 to 30% of the total glucan to cycloamyloses in 80 min, was incubated at 40°C. The CGTases used were 297 U (3.1 μg) of A2-5a CGTase, 354 U (0.97 μg) of Bmac CGTase, and 286 U (2.6 μg) of Bste CGTase, which produced 3.4, 3.5, and 4.5 μg of cycloamylose per ml per min, respectively. Periodically, 5 ml of the reaction mixture was taken in a glass tube and boiled for 10 min. The sample was incubated with 3.75 U of glucoamylase/ml at 40°C for 18 h. After the reaction was terminated by boiling the solution for 10 min, 4.5 ml of the sample was loaded on a SepPak Plus C18 cartridge column (Waters). The column was washed with 10 ml of distilled water, and then the cycloamyloses were eluted with 5 ml of 50% methanol. The eluate was dried in vacuo, dissolved in 150 mM NaOH, and analyzed by HPAEC using 200 pmol of G5 as an internal standard.

RESULTS

Overview of the actions of three different CGTases on amylose.

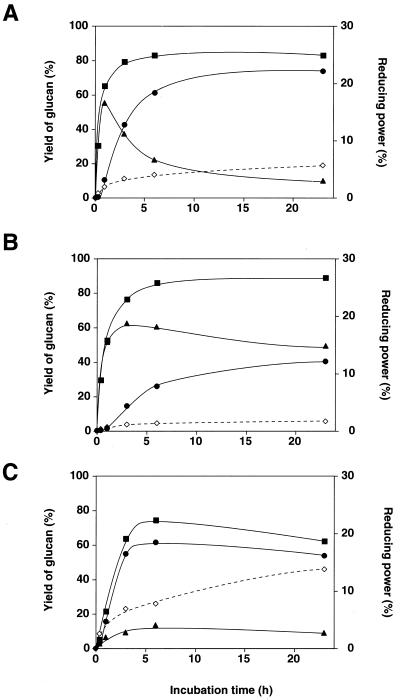

Amylose AS-110 was incubated with 170 U of A2-5a CGTase (1.8 μg), Bmac CGTase (0.47 μg), and Bste CGTase (1.5 μg), and the amounts of cycloamyloses and the reducing powers of the reaction mixtures were measured (Fig. 1). The amount of total cycloamylose produced by A2-5a CGTase and Bmac CGTase increased similarly with time and reached more than 80% at 3 h (Fig. 1A and B). However, Bste CGTase produced cycloamylose at a lower initial rate and with a lower yield than the other two enzymes (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, the reducing power was highest in the reaction mixture of Bste CGTase and lowest in that of Bmac CGTase (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Time course of the amount of cycloamyloses and the reducing power produced by the action of CGTases. The total amount of cycloamyloses (solid squares) and cyclomaltodextrins (CD6, CD7, and CD8) (solid circles) were determined after glucoamylase treatment of the reaction mixtures of alkalophilic Bacillus sp. strain A2-5a (A), B. macerans (B), and B. stearothermophilus (C). The amount of cycloamyloses with DP of more than 9 (solid triangles) were calculated by subtracting the amount of cyclomaltodextrins from the total cycloamyloses. The reducing power (open diamonds) when all of the amylose was broken down to glucose was defined as 100%.

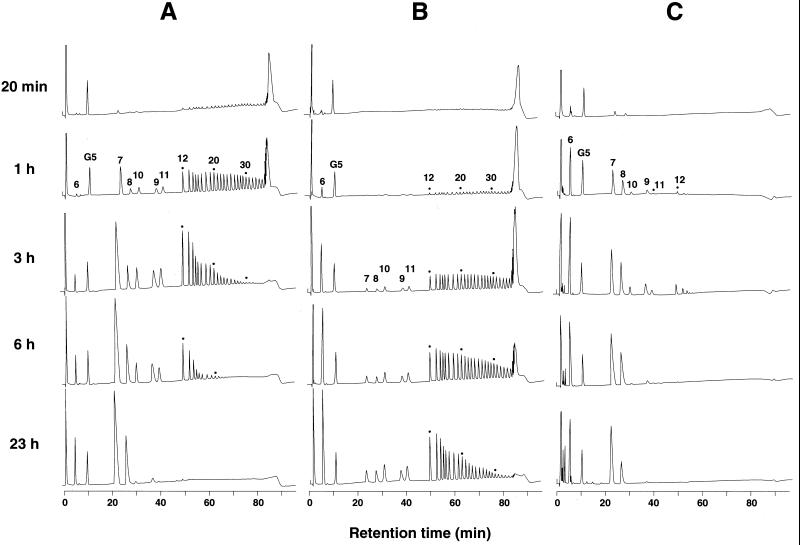

The differences among the three enzymes became more apparent when the compositions of the resulting cycloamyloses were considered. In the case of A2-5a CGTase, most of the cycloamyloses produced at the early stage of the reaction were not cyclomaltodextrins (CD6, CD7, and CD8) but rather CD9 and larger (Fig. 1A and 2A). These larger cycloamyloses were then converted into smaller ones as incubation progressed and were finally replaced by cyclomaltodextrins, among which CD7 was the major product (Fig. 2A). Cycloamyloses larger than CD9 were also the major products at the early stage of the reaction with Bmac CGTase (Fig. 1B and 2B). However, the decrease in these larger cycloamyloses with Bmac CGTase was slower than with A2-5a CGTase, and the amount of cycloamyloses larger than CD9 was higher than that of cyclomaltodextrins even after 24 h of incubation (Fig. 1B). Among cyclomaltodextrins, CD6 was the major product of Bmac CGTase (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, Bste CGTase produced mainly CD6, CD7, and CD8 even at the initial stage of the reaction (Fig. 1C), where CD6 and CD7 were the major products (Fig. 2C). These results clearly suggest that CGTases differ not only with regard to the equilibrium amounts of cyclomaltodextrins produced but also with regard to the courses by which they are formed.

FIG. 2.

HPAEC analysis of cycloamyloses produced by the action of CGTases. Amylose AS-110 (0.2% [wt/vol]) was incubated with 85 U of CGTases/ml from alkalophilic Bacillus sp. strain A2-5a (A), B. macerans (B), and B. stearothermophilus (C), and the reactions were terminated periodically. Cycloamyloses in each reaction mixture (25 μl) were analyzed by HPAEC. The number above each peak indicates the DP of cycloamyloses. G5 indicates maltopentaose (500 pmol) added as an internal standard.

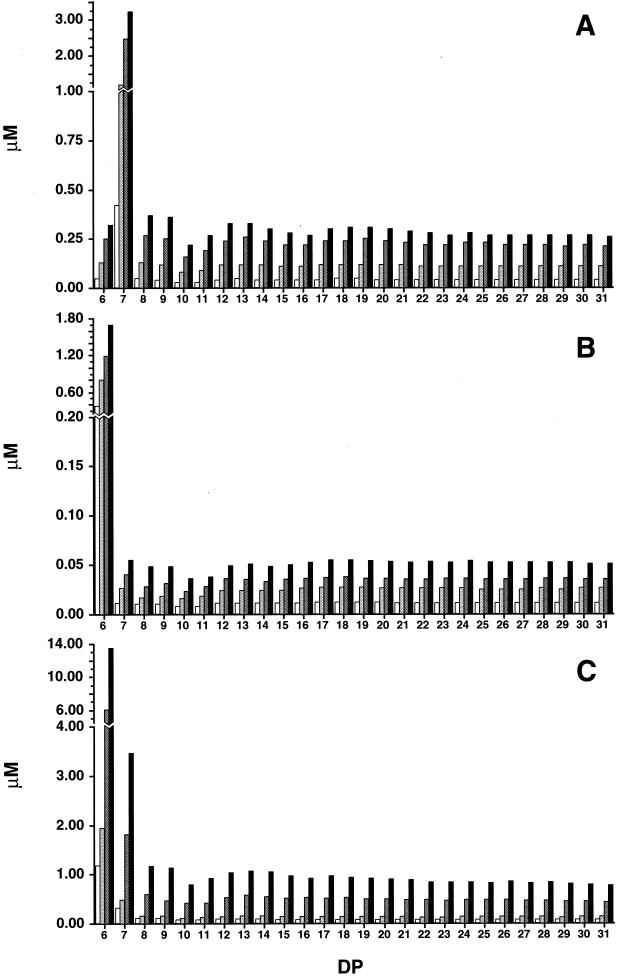

Initial actions of CGTases on amylose.

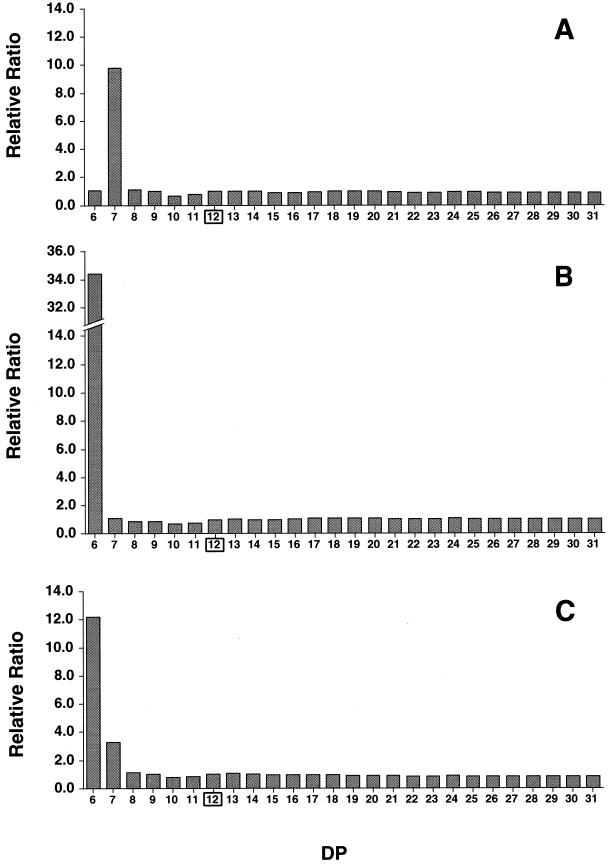

To further investigate the initial reactions of CGTases on amylose, similar experiments were carried out with decreased enzyme activity and a shorter incubation period, and the amount of each cycloamylose (CD6 to CD31) was quantified by HPAEC (Fig. 3). Under these reaction conditions, cycloamyloses larger than CD9 (up to more than CD50) were detected, even in the reaction mixture of Bste CGTase, indicating that, similar to the other two CGTases, Bste CGTase can produce larger cycloamyloses. At this stage in the reaction, the amounts of each cycloamylose in the reaction mixtures of all three CGTases increased simultaneously (Fig. 3). As a result, the relative ratios of cycloamyloses were nearly constant throughout the reaction period (Fig. 4). These results clearly demonstrate the product specificity of CGTase in the cyclization reaction. A2-5a CGTase produced cycloamyloses from CD6 to CD31, except for CD7, at similar rates, while CD7 was produced at a rate about 10 times higher than the others (Fig. 4A). Surprisingly, neither CD6 nor CD8 was preferentially produced by this enzyme, although they accumulated significantly as final products. Similar results were obtained with Bmac CGTase, in that CD6 was produced at a rate about 34 times higher than the others (Fig. 4B). On the other hand, the product specificity of Bste CGTase was not limited to just one cyclomaltodextrin, and CD6 and CD7 were produced at rates about 12 and 3 times higher than those of the other cycloamyloses (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 3.

Time course of the amounts of cycloamyloses with DP of from 6 to 31. Amylose AS-110 (0.15% [wt/vol]) was incubated with CGTases from alkalophilic Bacillus sp. strain A2-5a (13.5 U/ml) (A), B. macerans (16.1 U/ml) (B), and B. stearothermophilus (13.0 U/ml) (C) for 20 (open bars), 40 (light shaded bars), 60 (dark shaded bars), and 80 (solid bars) min, respectively. Cycloamyloses with DP of from 6 to 31 were separately quantified by HPAEC.

FIG. 4.

Relative molar ratios of cycloamyloses with DP of from 6 to 31 produced by the action of CGTases. The values are shown as molar ratios relative to the amount of cycloamylose with a DP of 12 and represent the average relative molar ratios of 20-, 40-, 60-, and 80-min reactions of CGTase from alkalophilic Bacillus sp. strain A2-5a (A), B. macerans (B), and B. stearothermophilus (C) shown in Fig. 3.

The increase in reducing power during the reaction shown in Fig. 3 was also measured, and the hydrolytic activity was calculated (Table 1). To compare the extent of hydrolytic activity against cyclization activity, the activities for producing CD6 to CD31 were calculated and are also shown in Table 1. The hydrolytic activity varied among the three CGTases tested: Bste CGTase showed the highest hydrolytic activity, which was about 10 times higher than its cyclization activity for producing CD6 to CD31. The hydrolytic activities of A2-5a CGTase and Bmac CGTase were weaker but still eight and six times higher than their respective cyclization activities.

TABLE 1.

Cyclization and hydrolytic activities of CGTases on amylose

| CGTase | Cyclization (nmol/min/mg)

|

Hydrolysis (nmol/min/mg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD6 | CD7 | CD8 | CD12 | CD 6–31 | ||

| A2-5a CGTase | 17.4 | 148 | 16.6 | 15.6 | 521 | 3,930 |

| Bmac CGTase | 417 | 11.9 | 11.4 | 12.0 | 721 | 4,220 |

| Bste CGTase | 502 | 138 | 47.9 | 43.7 | 1,580 | 16,300 |

Actions of CGTases on cycloamylose.

The coupling and hydrolytic activities of the three CGTases were measured using different cycloamylose substrates (Table 2), i.e., cyclomaltodextrins (CD6, CD7, and CD8) and a cycloamylose mixture containing CD22 to CD50. With all three enzymes, the cycloamylose mixture was a far better substrate than cyclomaltodextrins in both the coupling and hydrolytic reactions. Among the cyclomaltodextrins, CD7 and CD8 were particularly poor substrates with all three enzymes. Among the three enzymes, Bste CGTase showed the highest linearization activities, which could be attributed to the difficulty of detecting larger cycloamyloses under the reaction conditions shown in Fig. 1 and 2. This substrate specificity in the coupling and hydrolytic reactions has not been reported but should be an important factor in determining the composition of the cycloamylose product, especially in the conversion of larger cycloamyloses into smaller cycloamyloses during prolonged incubation.

TABLE 2.

Coupling and hydrolytic activities of CGTases on cycloamyloses

| CGTase | Coupling (mU/mg)

|

Hydrolysis (mU/mg)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD6 | CD7 | CD8 | CAa | CD6 | CD7 | CD8 | CAa | |

| A2-5a CGTase | 1,350 | 618 | 451 | 4,490 | 245 | 76.0 | 119 | 1,470 |

| Bmac CGTase | 2,810 | 70.0 | 76.7 | 7,680 | 607 | 39.6 | 67.9 | 1,410 |

| Bste CGTase | 12,800 | 850 | 1,190 | 24,300 | 3,030 | 434 | 657 | 14,800 |

Cycloamyloses with DP of from 22 to about 50 produced by amylomaltase from T. aquaticus.

DISCUSSION

CGTases convert α-1,4-glucans (starch and its components) into a mixture of CD6, CD7, and CD8, and the compositions of the products vary with the particular CGTase used (4, 9, 32). It had been generally believed that such product specificity was primarily determined by the frequency of the attack of the CGTase at the sixth, seventh, or eighth glucosidic linkage from the nonreducing end of an α-1,4-glucan substrate, like an exo-type enzyme. However, we demonstrated in a previous paper that this model is unlikely, since the composition of cycloamyloses changes drastically, from large cycloamyloses with DP of more than 60 into smaller cycloamyloses, as the reaction progresses (30). In the present study, we investigated the actions of three different CGTases on amylose and determined whether there were any differences in their specificities, and we found that not only the compositions of CD6, CD7, and CD8 under equilibrium conditions but also the courses of their production were different (Fig. 1 and 2). CGTase can catalyze various glucan transfer reactions with starch, i.e., cyclization and disproportionation reactions of linear glucans, the coupling reaction of cycloamyloses, and hydrolysis. Among these reactions, the factors that directly determine the composition of cycloamyloses are the product specificity of the cyclization reaction and the substrate specificity of the linearization reaction, including the coupling and hydrolytic reactions of cycloamyloses (Fig. 5).

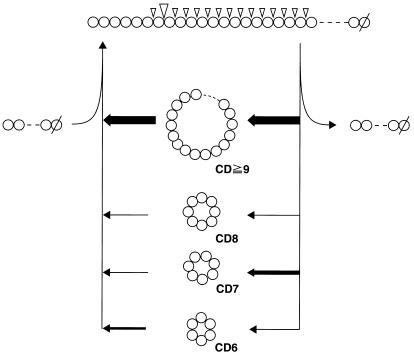

FIG. 5.

Schematic diagram of the cyclization reaction of CGTase with amylose. A model for the reactions of CGTase from alkalophilic Bacillus sp. strain A2-5a is shown. The right and left arrows indicate cyclization and coupling reactions, respectively, and the relative width of each arrow represents the relative rate of the reaction. ▿, α-1,4 linkages attacked by CGTase to produce cycloamyloses (the relative size represents the relative rate of the cyclization reaction shown in Fig. 4); ○, glucosyl residue; ∅, glucosyl residue with a reducing end.

The product specificities of these three CGTases are clearly shown in Fig. 4. A2-5a CGTase and Bmac CGTase primarily cleave the seventh and sixth glucosidic linkages. This substrate recognition seems to be very strict, since neighboring linkages (e.g., the sixth and eighth linkages with A2-5a CGTase) were not preferred by either enzyme. In addition to this strict substrate recognition, these CGTases also showed extreme randomness in substrate recognition, which resulted in the accumulation of larger cycloamyloses (from CD8 to more than CD31) at a constant molar ratio (Fig. 4). This random attack by CGTases is also supported by an analysis of their actions on fluorescently labeled soluble starch (8). We think that this specificity and randomness in glucosidic linkage recognition are the most important factors in determining the composition of cycloamyloses (Fig. 5).

As the reaction progressed, the larger cycloamyloses that were initially produced were converted into smaller cycloamyloses with all three CGTases studied. For this conversion, larger cycloamyloses should first be linearized by either a coupling or a hydrolytic reaction; CD7 and CD8 are extremely poor substrates for both reactions compared to mixtures of larger cycloamyloses (Table 2). Thus, among the initial cyclization reaction products, larger cycloamyloses are selectively subjected to the linearization reaction (Fig. 5), and the linear amyloses produced are cyclized again into cycloamyloses as described above. On the other hand, cyclomaltodextrins, especially CD7 and CD8, were virtually nonreactive in these linearization and cyclization reactions. Repetition of the cyclization reaction and the linearization reaction is the principal mechanism whereby large cycloamyloses are converted into smaller cyclomaltodextrins, resulting in the final equilibrium composition of cyclomaltodextrins (Fig. 2).

Although the three CGTases probably use a common mechanism for the conversion of larger cycloamyloses into smaller ones, the rates of this conversion were surprisingly different, especially for Bste CGTase versus the other two CGTases (Fig. 1 and 2). It is likely that this difference is due to the extent of the hydrolytic reaction. Among the three CGTases studied, Bste CGTase showed the highest hydrolytic activity (Fig. 1 and Tables 1 and 2). Hydrolytic activity leads to the net degradation of α-1,4-glucan and to an increase in the number of acceptor molecules for the coupling reaction, both of which should contribute to the acceleration of the conversion of larger cycloamyloses into smaller cycloamyloses. On the other hand, the hydrolytic activities of A2-5a CGTase and Bmac CGTase were nearly the same (Tables 1 and 2). However, the activity to reduce the iodine-staining power of Bmac CGTase (362 kU/mg) was higher than that of A2-5a CGTase (94.8 kU/mg) and also that of Bste CGTase (110 kU/mg). Therefore, since the amount of enzyme protein in the reaction mixture shown in Fig. 1 and 2 (85 U/ml) for Bmac CGTase was lower than that for A2-5a CGTase, the hydrolytic activity in the reaction mixture of Bmac CGTase was lower than those of A2-5a CGTase, which leads to the lower rate of conversion of larger cycloamyloses into smaller cycloamyloses of Bmac CGTase. Although there are other CGTases with different product specificities of cyclomaltodextrins compared to those of the three CGTases described here, we believe that the model presented in Fig. 5 can explain the reactions of other CGTases.

Although CGTase is considered a typical glucan transferase, it can also catalyze the hydrolytic reaction at the same active site through the same catalytic mechanism as that of the transglycosylation reaction (33). The reaction specificity (the ratio of transglycosylation to hydrolysis) is expected to be determined by the active-site structure and environment of each CGTase and should vary from one enzyme to another. Accurate measurement of the reaction specificity of each CGTase is of great interest, but it is difficult, since it is not possible to assay the disproportionation activity with amylose. However, our results shown in Tables 1 and 2 provide information for understanding the reaction specificity of CGTases. In Table 2, we used cycloamylose as a donor and glucose as an acceptor, in which case CGTase catalyzes only the coupling reaction as a transglycosylation reaction. With all three CGTases, maximum coupling and hydrolytic activities were obtained with CD22 and larger molecules. Surprisingly, the coupling activities of A2-5a CGTase, Bmac CGTase, and Bste CGTase were only 3.1, 5.4, and 1.6 times higher than their respective hydrolytic activities. Moreover, as shown in Table 1, the hydrolytic activities of all three CGTases were higher than the cyclization activities for producing CD6 to CD31. Note that the cyclization activities presented in Table 1 are underestimates: while all of these CGTases produced CD32 and larger, the activities for producing them are not considered in the cyclization activity shown. This discrepancy notwithstanding, these results strongly suggest that the hydrolytic activity of CGTase is not negligible. This contradiction is probably due to a previous underestimate of the hydrolytic activity of CGTases. Hydrolytic activity was measured either with cyclomaltodextrins as substrates or with soluble starch, but at the stage when most cycloamyloses were converted into cyclomaltodextrins. It is apparent from the present work that cyclomaltodextrins are very poor substrates for the hydrolytic reaction with CGTase.

These results raise the question of whether CGTase is really a typical glucan transferase. Amylomaltase (D-enzyme; EC 2.4.1.25) is a similar glucan transferase and also catalyzes the cyclization reaction of α-1,4-glucan to produce cycloamyloses. Both enzymes belong to the α-amylase family and are expected to follow the same catalytic mechanism. Despite this similarity, amylomaltase and CGTase differ in several respects. The smallest cycloamyloses produced by amylomaltase from T. aquaticus and potato are CD22 and CD17, respectively, and CD6, CD7, and CD8 are never produced (27, 29). CGTase seems to be able to recognize six or seven glucosyl units to produce a specific type of cycloamylose, but this is not the case for amylomaltase, which randomly produces cycloamylose. The hydrolytic activity of amylomaltase is much lower than that of CGTases (our unpublished results). Thus, a comparison of CGTase with amylomaltase should provide various useful pieces of information. In addition to the structure of CGTases (3, 6, 7, 12, 14), the crystal structure of amylomaltase from T. aquaticus (19) has recently become available. These results should contribute to our understanding of the actions of these enzymes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beier L, Svendsen A, Andersen C, Frandsen T P, Borchert T V, Cherry J R. Conversion of the maltogenic α-amylase Novamyl into a CGTase. Protein Eng. 2000;13:509–513. doi: 10.1093/protein/13.7.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiedler G, Pajatsch M, Böck A. Genetics of a novel starch utilization pathway present in Klebsiella oxytoca. J Mol Biol. 1996;256:279–291. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harata K, Haga K, Nakamura A, Aoyagi M, Yamane K. X-ray structure of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase from alkalophilic Bacillus sp. 1011. Comparison of two independent molecules at 1.8Å resolution. Acta Crystallogr D. 1996;52:1136–1145. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996008438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitahata S, Okada S. Comparison of action of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase from Bacillus megaterium, B. circulans, B. stearothermophilus and B. macerans. J Jpn Soc Starch Sci. 1982;29:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitahata S, Tsuyama N, Okada S. Purification and some properties of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from a strain of Bacillus species. Agric Biol Chem. 1974;38:387–393. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein C, Schulz G E. Structure of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase refined at 2.0Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1991;217:737–750. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90530-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knegtel R M A, Wind R D, Rozeboom H J, Kalk K H, Buitelaar R M, Dijkhuizen L, Dijkstra B W. Crystal structure at 2.3Å resolution and revised nucleotide sequence of the thermostable cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Thermoanaerobacterium thermosulfurigenes EM1. J Mol Biol. 1996;256:611–622. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobayashi M, Kasuga M. Further evidence for the random attack of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase on soluble starch. J Appl Glycosci. 1998;45:379–384. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi S. Cyclodextrin producing enzyme (CGTase) In: Park K H, Robyt J F, Choi Y-D, editors. Enzymes for carbohydrate engineering. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science B. V.; 1996. pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koizumi K, Sanbe H, Kubota Y, Terada Y, Takaha T. Isolation and characterization of cyclic α-(1→4)-glucans having degrees of polymerization 9–31 and their quantitative analysis by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection. J Chromatogr A. 1999;852:407–416. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(99)00643-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kometani T, Terada Y, Nishimura T, Takii H, Okada S. Purification and characterization of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase from an alkalophilic Bacillus species and transglycosylation at alkaline pHs. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1994;58:517–520. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubota M, Matsuura Y, Sakai S, Katsube Y. Three-dimensional structure of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase and its reaction mechanism. J Appl Glycosci. 1994;41:245–253. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen K L, Endo T, Ueda H, Zimmermann W. Inclusion complex formation constants of α-, β-, γ-, δ-, ɛ-, ζ-, η- and θ-cyclodextrins determined with capillary zone electrophoresis. Carbohydr Res. 1998;309:153–159. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawson C L, van Montfort R, Strokopytov B, Rozeboom H J, Kalk K H, de Vries G E, Penninga D, Dijkhuizen L, Dijkstra B W. Nucleotide sequence and X-ray structure of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Bacillus circulans strain 251 in a maltose dependent crystal form. J Mol Biol. 1994;236:590–600. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miwa I, Okuda J, Maeda K, Okuda G. Mutarotase effect on colorimetric determination of blood glucose with β-d-glucose oxidase. Clin Chim Acta. 1972;37:538–540. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(72)90483-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura A, Haga K, Yamane K. The transglycosylation of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase is operated by a ping-pong mechanism. FEBS Lett. 1994;337:66–70. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parsiegla G, Schmidt A K, Schulz G E. Substrate binding to a cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase and mutations increasing the γ-cyclodextrin production. Eur J Biochem. 1998;255:710–717. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2550710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penninga D, Strokopyov B, Rozeboom H J, Lawson C L, Dijkstra B W, Bergsma J, Dijkhuizen L. Site-directed mutations in tyrosine 195 of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Bacillus circulans strain 251 affect activity and product specificity. Biochemistry. 1995;34:3368–3376. doi: 10.1021/bi00010a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Przylas I, Tomoo K, Terada Y, Takaha T, Fujii K, Saenger W, Sträter N. Crystal structure of amylomaltase from Thermus aquaticus, a glycosyltransferase catalysing the production of large cyclic glucans. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:873–886. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saenger W. Cyclodextrin inclusion compounds in research and industry. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1980;19:344–362. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmid G. Cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase production yield enhancement by overexpression of cloned genes. Trends Biotechnol. 1989;7:244–248. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt A K, Cottaz S, Driguez H, Schulz G E. Structure of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase complexed with a derivative of its main product β-cyclodextrin. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5909–5916. doi: 10.1021/bi9729918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sin K-A, Nakamura A, Masaki H, Matsuura Y, Uozumi T. Replacement of an amino acid residue of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase of Bacillus ohbensis doubles the production of γ-cyclodextrin. J Biotechnol. 1994;32:283–288. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(94)90214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starnes R L. Industrial potential of cyclodextrin glycosyl transferases. Cereal Food World. 1990;35:1094–1099. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strokopytov B, Knegtel R M A, Penninga D, Rozeboom H J, Kalk K H, Dijkhuizen L, Dijkstra B W. Structure of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase complexed with a maltononaose inhibitor at 2.6Å resolution. Implications for product specificity. Biochemistry. 1996;35:4241–4249. doi: 10.1021/bi952339h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tachibana Y, Kuramura A, Shirasaka N, Suzuki Y, Yamamoto T, Fujiwara S, Takagi M, Imanaka T. Purification and characterization of an extremely thermostable cyclomaltodextrin glucanotransferase from a newly isolated hyperthermophilic archaeon, a Thermococcus sp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1991–1997. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.1991-1997.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takaha T, Yanase M, Takata H, Okada S, Smith S M. Potato D-enzyme catalyzes the cyclization of amylose to produce cycloamylose, a novel cyclic glucan. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2902–2908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeda Y, Guan H-P, Preiss J. Branching of amylose by the branching isoenzymes of maize endosperm. Carbohydr Res. 1993;240:253–263. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terada Y, Fujii K, Takaha T, Okada S. Thermus aquaticus ATCC 33923 amylomaltase gene cloning and expression and enzyme characterization: production of cycloamylose. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:910–915. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.910-915.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terada Y, Yanase M, Takata H, Takaha T, Okada S. Cyclodextrins are not the major cyclic α-1,4-glucans produced by the initial action of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase on amylose. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15729–15733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tilden E B, Hudson C S. Conversion of starch to crystalline dextrins by the action of a new type of amylase separated from cultures of Aerobacillus macerans. J Am Chem Soc. 1939;63:2900–2902. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tonkova A. Bacterial cyclodextrin glucanotransferase. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1998;22:678–686. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uitdehaag J C, van Alebeek G J, van der Veen B A, Dijkhuizen L, Dijkstra B W. Structures of maltohexaose and maltoheptaose bound at the donor sites of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase give insight into the mechanisms of transglycosylation activity and cyclodextrin size specificity. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7772–7780. doi: 10.1021/bi000340x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uitdehaag J C M, Kalk K H, van der Veen B A, Dijkhuizen L, Dijkstra B W. The cyclization mechanism of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase (CGTase) as revealed by a γ-cyclodextrin-CGTase complex at 1.8-Å resolution. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34868–34876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Veen B A, van Alebeek G-J W M, Uitdehaag J C M, Dijkstra B W, Dijkhuizen L. The three transglycosylation reactions catalyzed by cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Bacillus circulans (strain 251) proceed via different kinetic mechanisms. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:658–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Veen B A, Uitdehaag J C M, Penninga D, van Alebeek G-J W M, Smith L M, Dijkstra B W, Dijkhuizen L. Rational design of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Bacillus circulans strain 251 to increase α-cyclodextrin production. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:1027–1038. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wind R D, Uitdehaag J C M, Buitelaar R M, Dijkstra B W, Dijkhuizen L. Engineering of cyclodextrin product specificity and pH optima of the thermostable cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Thermoanaerobacterium thermosulfurigenes EM1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5771–5779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamamoto T, Fujiwara S, Tachibana Y, Takagi M, Fujui K, Imanaka T. Alteration of product specificity of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase from Thermococcus sp. B1001 by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biosci Bioeng. 2000;89:206–209. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(00)88740-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]