Abstract

Using data from a large longitudinal sample (N=1,292) of children and their caregivers in predominantly low-income nonurban communities, we investigated longitudinal relations between attuned caregiving in infancy, joint attention in toddlerhood, and executive functions in early childhood. Results from path analysis demonstrated that attuned caregiving during infancy predicted more joint attention in toddlerhood, which was in turn associated with better executive function performance in early childhood. Joint attention was a stronger predictor of executive functions for lower-income families. Moreover, joint attention mediated the relation between attuned caregiving and executive functions, and this mediation was amplified for lower-income families. These results highlight joint attention as a key mechanism through which attuned caregiving supports the development of executive functions, particularly for low-income families.

Keywords: joint attention, attuned caregiving, executive function, poverty

Human development in infancy is strongly dependent on social context. Interpersonal coordination between infants and their caregivers creates a shared social environment, marked by dynamic, reciprocal affective and behavioral exchanges, through which the infant develops (Bolis & Schilbach, 2018; Feldman, 2007; Fogel, 1993; Vygotsky, 1975). Evidence for the social origins of cognitive development is documented in research suggesting that sensitive caregiving behaviors practiced during infant-caregiver interactions facilitate cognitive development (for review see Hughes & Ensor, 2009). Caregiving is typically studied using broad, global ratings of parenting behaviors, however, little is known about the specific mechanisms within infant-caregiver interactions that may be driving cognitive development. In particular, attuned caregiving, defined here as sensitive and temporally-contingent responsive caregiving behaviors, is an important component of the caregiver-infant interaction. Attuned caregiver interactions in infancy are thought to set the foundation for more advanced social exchanges such as the development of joint attention in the toddler period (Legerstee, Markova, & Fischer, 2006). Here we define and conceptualize joint attention on the dyadic level during the interactions themselves. In joint attention interactions, dyads engage in bouts of coordinated gaze during which caregivers and infants guide each other’s attention to stimuli in the environment (Bakeman & Adamson, 1984; Seibert et al., 1982; Scaife & Bruner, 1975). Through these shared experiences it has recently been proposed that joint attention may function as a cognitive scaffolding mechanism, allowing parents to train the essential ‘building blocks’ of higher-order cognitive development, such as executive functions (Hughes & Devine, 2017; Wass, Clackson, et al., 2018; Yu & Smith, 2016). However, research has yet to examine how the effects of joint attention may function differently depending on environmental factors, such as socioeconomic risk. Thus, longitudinal investigations of the links between caregiver attunement, joint attention interactions in socioeconomically diverse contexts, and higher-order cognitive outcomes are warranted to understand the various social factors that contribute to individual differences and disparities in executive function development.

It is well established that various aspects of sensitive parenting behavior longitudinally predict executive function development (Blair et al., 2011; Bernier, Carlson, & Whipple, 2010; Fay-Stammbach, et al., 2014; Lugo-Gil & Tamis-LeMonda, 2008; Rhoades, et al. 2011). In particular, attuned caregiving, a sensitive parenting behavior that includes appropriate contingency, responsivity, and matching based on the child’s developmental and affective needs is especially important for cognitive development (Feldman, 2007). Through attuned interactions, caregivers flexibly respond to and regulate their children’s behavioral and cognitive cues (Landry & Smith, 2010). This reciprocal “serve-and-return” of bids and contingent responses offer children the opportunity to test and develop their self-regulatory capacities in a safe environment (Bernier et al., 2012). Further, attuned interactions provide the foundation for an affiliative parent-child relationship, creating an environment that is conducive to cognitive development (Bornstein & Tamis-LeMonda, 1997). However, attuned caregiving is a broad and global construct, yet little research has been devoted to studying the operating dyadic processes that develop from attuned infant-caregiver interactions. Attuned caregiving may be important for promoting cognitive development, particularly executive functions, which are known to be critical for academic readiness and self-regulation (Blair & Raver, 2015).

Starting early in infancy, caregivers practice attuned behaviors towards their infants during face-to-face interactions (Tronick & Cohn, 1989). This dyadic interaction is theoretically considered to be a developmental antecedent to more advanced, triadic caregiver-infant reciprocal exchanges such as joint attention, or the coordination of visual attention between individuals to shared objects in the environment (Scaife and Bruner 1975; Tomasello, 1995; Vygotsky, 1979). In the current study, we conceptualize joint attention on the dyadic level during interactions with caregivers, which emphasizes the simultaneous and concurrent shared attention behaviors of both infant and caregiver during the shared social exchanges. This definition differs from individual-level joint attention, which typically emphasizes the infant’s ability to respond to and initiate joint attention bids (Mundy and Newell 2007; Tomasello, 1995). Through the development of joint attention, infants gain a rudimentary social understanding of the cognitive and affective states of others (Reddy & Legerstee, 2007, Trevarthen, 1979). Theoretically, joint attention is considered to be an interpersonal engagement process through which caregivers create shared mental states that form the basis of infant cognitive development (Reddy & Legerstee, 2007). Repeated instances of dyadic attuned caregiving likely set the foundation for triadic joint attention interactions in which caregivers and infants share attention to other objects in their environment. Therefore, it follows that differences in caregiver attunement behaviors earlier in infancy could result in differences in joint attention interactions later in development. Indeed, evidence suggests that the development of joint attention is subject to significant individual differences, which have been traced to variability in the quality of caregiver interactions (Raver & Leadbeater, 1995). Specifically, mothers who demonstrate greater reciprocal bidding and affect matching — key characteristics of attuned parenting—have longer bouts of joint attention (Markova & Legerstee 2006). However, research has yet to explicitly test whether early-life attuned caregiving is a social antecedent to joint attention.

Investigating the early-life precursors to joint attention is critical given that joint attention is thought to support children’s cognitive development. Historically, theory suggests that higher-order cognitive abilities develop through social interactions between infants and their caregivers (Bruner, 1999; Fogel, 1993; Vygotsky, 1978). It has been proposed that through joint attention interactions, infants develop the capacity for intra-individual cognitive regulation (Bolis & Schilbach, 2018; Reddy et al. 1997). Recent empirical research has begun to test this theory by investigating how normative variations in joint attention relate to cognitive control abilities, concurrently and longitudinally. A seminal study by Yu & Smith (2016) highlighted the importance of the social context on immediate sustained attention episodes. Specifically, using head-mounted eye trackers to record moment-by-moment eye gaze patterns in 12-month old infants, Yu and Smith found that when parents visually attended to an object through joint attention, the duration of the infant’s subsequent look towards that object was prolonged. This study suggests that joint attention may be a tool whereby a mature social partner is able to scaffold an infant’s visual sustained attention to facilitate attentional control development. Similarly, Wass et al. (2018) found that infant sustained attention towards an object was higher during joint play relative to solo play and that parent’s attention towards objects predicted subsequent infant sustained attention. Both studies highlight the extent to which caregivers are able to contingently prolong infant’s sustained attention during real-time interactions. These findings indicate that caregivers may guide the emergence of internalized sustained attention in infants by engaging in joint attention behaviors during interactions.

Joint attention has been conceptualized neurobiologically as coordination of the posterior orienting attention system and the anterior executive attention system, which are involved in gaze (or other ostensive signals) following and the allocation of volitional, goal-directed attention, respectively (Mundy & Newell 2007; Posner & Petersen 1990). Repeated activation of these core attention networks during joint attention interactions likely strengthens their structural and functional connectivity, thus promoting the individual’s cognitive abilities over time. Indeed, recent research has demonstrated longitudinal associations between joint attention and cognitive control development (Niedźwiecka, Ramotowska, & Tomalski, 2017; Vaughan Van Hecke et al., 2012). Specifically, a study by Niedzweicka et al. (2017) found that at five months, mutual gaze during infant-caregiver free play interactions was positively associated with 11-month infant attentional control, assessed with a gap-and-overlap looking task. These findings highlight the importance of parent-child shared visual gaze on the development of infant attentional control, which is fundamental to higher-order cognitive processes. Complementary research demonstrated that an infant’s ability to respond to joint attention around 12 months of age was positively associated with attention regulation strategies during a delay of gratification task at 36 months (Vaughan Van Hecke et al., 2012). Given that joint attention integrates information processing, visual attention orienting, sustaining attention, and disengaging attention, these findings offer initial evidence that joint attention may provide socially-anchored scaffolding for executive attention networks that support more complex executive function processes.

Collectively, the literature suggests that attuned, contingent-responsive parenting behaviors predict joint attention and that joint attention may promote sustained attention in real-time and subsequent higher-order cognitive control development. Thus, it is plausible that through joint attention, parental attunement in infancy facilitates the basic building blocks of cognition that likely have enduring implications for the development of executive functions. However, a cohesive examination of a proposed developmental cascade linking caregiving attunement in infancy with joint attention in toddlerhood to early childhood executive function has yet to be empirically investigated.

Thus far, most studies on joint attention have been drawn from relatively small, socioeconomically homogenous samples. Therefore, it is currently unknown how the effects of joint attention may differ depending on the child’s environmental context. This is a critical limitation of the existing joint attention literature, given the research demonstrating interactions between the socioeconomic environment and parent-child interactions. Specifically, research has found that sensitive caregiving within low-income households can buffer against some of the detrimental effects of socioeconomic adversity on children’s developmental outcomes (Blair & Raver, 2016; Hostinar, Sullivan, Gunnar, 2014). Theoretically, there is reason to believe that the socioeconomic environment may moderate the effect of joint attention. In low-income households with fewer material resources that may be used to promote executive function development, infants may rely more on and reap greater benefits from attuned caregiver interactions to scaffold core cognitive processes (Rosen et al., 2019). Thus, it is possible that joint attention experiences between caregivers and their infants could buffer against some of the detrimental effects associated with living in poverty. Specifically, given the research demonstrating links between joint attention and later higher-order cognitive abilities, it is possible that joint attention is one important component of caregiver-infant interactions that facilitates executive function development, especially for lower-income families. However, as most prior work has used cross-sectional analyses, research is needed to longitudinally investigate the links between attuned caregiving, joint attention, and higher-order cognitive outcomes in a variety of socioeconomic contexts.

Additionally, a related limitation of previous research concerning context is that much of the relevant work has been carried out in less ecologically valid environments, namely laboratories. More specifically, most research has studied joint attention using standard laboratory-based tasks to elicit joint attention behaviors. However, joint attention is a naturally occurring phenomenon that is spontaneously elicited during everyday parent-child interactions. Furthermore, given the importance of environmental context in shaping caregiving behaviors and infant development, it may be especially important to assess these variables outside of the laboratory, in ecologically-valid settings, such as the home, especially when investigating potential socioeconomic differences. Here we extend the current literature on joint attention by examining naturalistic measures of joint attention and caregiving behaviors measured in the home environment among socioeconomically diverse families.

The Present Study

The aim of the present study was to address four research questions regarding relations between early life attuned caregiving, joint attention interactions in toddlerhood, and subsequent development of executive functions in early childhood. First, how does variability in observed global attuned caregiving behavior during an infant’s first year of life predict task-based joint attention at 24 months of age, as well as executive function abilities at 48 months? Second, are individual differences in children’s engagement in joint attention episodes at 24 months predictive of their executive functions at 48 months of age? Third, do relations between joint attention and executive functions differ depending on families’ income-to-needs ratio (INR)? Fourth, are the associations between attuned caregiver behaviors and early childhood executive functions mediated by joint attention? And finally, as an exploratory component of the study, we tested for moderated mediation to investigate whether the interaction between joint attention and INR mediated the relation between attuned caregiving and childhood executive functions. Consistent with prior literature, we first hypothesized that higher levels of attuned parenting behaviors during infancy would be predictive of higher executive functions in early childhood. Additionally, we hypothesized that early-life attuned caregiving behaviors would be predictive of higher joint attention in toddlerhood. Similarly, we hypothesized that joint attention at 24 months of age would be positively associated with executive functions at 48 months of age. Concerning our third question, we hypothesized that the association between joint attention and executive functions would be particularly strong for families with lower INR. Finally, we hypothesized that associations between attuned caregiving behaviors during infancy and executive functions in early childhood would be partially explained by joint attention in toddlerhood and this effect would be amplified for lower income families.

Methods

Participants

The Family Life Project (FLP) is a prospective longitudinal study of families residing in six low-wealth counties in Eastern North Carolina and Central Pennsylvania (three counties per state) that were selected to be indicative of the Black South and Appalachia, respectively. The FLP adopted a developmental epidemiological design whereby complex sampling procedures were used to recruit a representative sample of 1,292 children whose families resided in one of the six counties at the time of the child’s birth. Low-income families in both states and African American families in NC were over-sampled. Detailed descriptions of the participating families and communities are available in Vernon-Feagans, Cox, and the FLP Investigators (2013).

Procedures

The data for this analysis were collected in participants’ homes at child ages 7, 15, 24 and 48 months This study was approved by the Office of Human Research Ethics at the University of North Carolina (protocol # 05–0201; “Family Life Project: 15 through 48 Month Participation”). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. During home visits at each time point, the child’s primary caregiver provided information on demographics and numerous aspects of family life and relationships. At 15 months, parenting behaviors were observed during a semi-structured parent-child interaction task. Immediately following the home visits, research assistants (RAs) completed ratings of the child’s attention during the 2–3 hours of data collection. At 24 months, measures of joint attention and codes for maternal language were derived from a book-reading task between children and their primary caregiver. Finally, at 48 months, children were administered a battery of executive function tasks.

Measures

Attuned Caregiving.

Global caregiving behaviors were observed between infants and their mothers in a 10-minute semi-structured, dyadic free-play task during the 15-month home visit. In this task, mothers were instructed to play with their infant using a provided set of standardized toys. The interaction was video recorded and later coded by highly trained coders along several dimensions of caregiving behaviors (Cox & Crnic, 2002; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 1999). The specific dimension of interest for the current analysis is attuned caregiving. Attuned caregiving behaviors were coded using a scale of 1 (not at all characteristic) to 5 (highly characteristic) by a team of coders, which included a master coder. Coders underwent training with their master coder until acceptable reliability was established, as determined by intraclass correlation coefficients (>0.80). Once acceptable reliability was established, coders coded in pairs while continuing to complete at least 30% of the videos with their master coder. Each coding pair met biweekly to reconcile scoring discrepancies, and the scores used in analysis were the final scores arrived at after reconciling. Coders rated attuned caregiving behaviors based on the following criteria: parenting behaviors that included instances of contingent vocalizations by the parent, appropriate attention focusing, evidence of good timing paced to child’s interest and arousal level, shared positive affect, and providing an appropriate level of stimulation. Generally, parenting behavior was coded as attuned if they demonstrated the ability to flexibly adapt contingent-responsive interactions to the child’s current affective state and developmental ability. Higher scores are indicative of greater attunement.

Joint Attention.

Joint attention was assessed at 24 months through a wordless picture book task between the mother and infant using the Early Attention to Reading Situations rating system (EARS; Feagans, Kipp, & Blood, 1994). At each time-point, mothers were given a wordless picture book to review before the session began. The mother was asked to go through the book and talk to the child about the book as she might normally do. Caregivers were assigned to share the books Just a Thunderstorm (Gina & Meyer, 2003) or The New Baby (Mayer, 2001) with their children (book assignment was counterbalanced across participants). After approximately 10 minutes the RA would ask the mother to stop if the picture book task had not ended. The RA used a laptop computer that was programmed to receive observational ratings every five seconds. The RA coded the child’s focus of attention at the 5 second beep into one of 5 mutually exclusive categories: look at book, look at caregiver, gaze aversion, look at RA/camera, off task, and joint attention. The joint attention category indicated whether the child’s eyes were focused on the same page of the book as the mother’s eyes or not. For example, when both the mother and child looked at the same page of the book at the same time, this was coded as joint attention. Because we were interested in examining the effects of naturalistically elicited coordinated attention episodes themselves, we operationalize joint attention broadly and do not delineate child initiated and responded joint attention. This conceptualization of joint attention has been used previously in prior Family Life Project publications (Gueron-Sela et al., 2018).

RAs practiced the rating system with pilot children until acceptable reliability was reached with the master rater (Cohen’s Kappas of at least .70). Five selected video recordings of the book sharing activity were then rated by the master rater periodically, to confirm and maintain a Cohen’s Kappa of at least .70 for each rater. A frequency score indicating the number of instances of joint attention was recorded for each dyad. Because the length of the book sharing activity varied, raw frequency scores were converted to proportion of time to be used in analyses. Specifically, for the final analysis variable, we created a mean proportion score for each dyad that represented the proportion of 5-second intervals in which joint attention was observed.

Executive Functions.

At 48 months of age, children were administered an executive function battery consisting of two working memory tasks, three inhibitory control tasks, and one attention shifting task. Preceding the test trials in each task, RAs administered training trials and children completed up to three practice trials. RAs discontinued the task for those children who did not demonstrate an understanding of the task. Each task was presented by a RA in an open spiral-bound flipbook with pages that measured 8 in. x 14 in. Details on the tasks and administration procedures as well as psychometric characteristics are available in Willoughby et al. (2011) and Willoughby et al. (2010). We provide a brief description of the tasks here. Working Memory Span (working memory). In the span task children are shown the outline of a house with an animal and a colored dot inside it, and are prompted to name the animal and the color of the dot. Then they are shown a blank house and asked to either report the animal or the color they had seen in the previous house. In order to perform correctly, children must hold two pieces of information in mind (i.e., the animal and the color), but only recall the prompted feature (e.g., animal). Pick the Picture Game (working memory). In this self-ordered pointing task, children are presented with sets of items. For each set, the same items appear on two sequential pages in a different arrangement. On the first page children are asked to “pick one” item. On each subsequent page, children are instructed to pick an item that wasn’t previously picked so that each picture “gets a turn.” Difficulty increases as more items, up to six, are added to sets. Silly Sounds Stroop (inhibitory control). Children are presented with pictures of cats and dogs and asked to make the sound opposite of that which is typically associated with that animal (e.g., when showed a dog, a correct response would be to make a meowing sound). Spatial Conflict Arrows (inhibitory control). In this Simon-like task children are presented response cards with two black circles (“buttons”) on either side of the page and an arrow on either the left or right side of the page. Children are instructed to touch the button corresponding to the side to which the arrow is pointing. The task proceeds in difficulty from displaying left-pointing arrows on the left and right-pointing arrows on the right of the page (congruent trials), to most arrows pointing to the side opposite from which they are positioned (incongruent trials). Animal Go/No- Go (inhibitory control). In this standard go/no-go task children are instructed to click a button (which made an audible sound) every time they see an animal (go trials) unless the animal is a pig (no-go trials). Varying numbers of go trials appear prior to each no-go trial, including, in standard order, 1-go, 3-go, 3-go, 5-go, 1-go, 1-go, and 3-go trials. Something’s the Same Game (attention shifting). In this task, children are presented with a pair of pictures for matching on a single dimension (e.g., both pictures were the same color). Subsequently, a third picture was presented, and children were asked to identify which of the first two pictures was similar to the new picture. This task requires the child to shift attention from the initial dimension to a new dimension of similarity (e.g., from color to size).

Executive Function Task Scoring and Composite Formation.

Children needed to complete at least 75% of trials for each task in order for their performance to be analyzed. Tasks were scored using item response theory as this is a more precise way to estimate children’s executive function abilities than percent correct scores. For the purpose of the current study, we were interested in examining executive functions unitarily as a measure of higher-order cognitive abilities. As such, expected a posteriori (EAP) scores were derived for each task and averaged to obtain a composite score (Willoughby, Wirth, & Blair, 2011). Z-scores were calculated to reflect accuracy on each of the six executive function assessments. The total score reflected the mean of all completed z-scored individual scores. We used a formative composite, as it has been found to more appropriately represent the overarching construct of executive function than a latent factor, which is limited to measurement of the shared variance among tasks that are only weakly to moderately correlated (Willoughby et al., 2017). The authors chose to composite across the subscales given the neuroscience-based evidence suggesting that in early childhood, EFs have far less specificity in their neural localization than in adulthood (Bruce Morton, 2010). Moreover, factor analysis supports the unitary structure of EFs in young children (Willoughby, Blair, Wirth, & Greenberg, 2012; Willoughby, Wirth, Blair, & Family Life Project, 2012) as opposed to three distinct domains (working memory, inhibitory control, and attention shifting) that are seen later in development. Prior studies using this battery with the same population have demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties with the composite executive function score (Willoughby, Blair, Wirth, & Greenberg, 2012). As is typical of executive function measures (Willoughby, Holochwost, Blanton, & Blair, 2014) the reliability coefficient for the composite was relatively low, α = 0.50.

Income-to-Needs Ratio.

Income-to-needs ratio (INR) was calculated using caregiver-reported household income during home visits and corresponding federal poverty threshold values. Specifically, at the 7- and 15-month home visit, primary caregivers were asked to provide detailed information about all sources of household income (e.g., employment income, cash welfare/TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families), social security retirement, help from relatives, etc.). This total annual income was divided by the federal poverty threshold to create the family’s INR. An INR of 1.0 is at the poverty line and indicates that a family may be unable to provide for basic needs. We averaged INR values across the 7- and 15- month time points to obtain a cumulative measure of early-life INR.

Covariates.

Individual Infant Focused Attention.

To control for the potential confounding of infant’s individual attention with executive function outcomes, we included a variable for infant focused attention in our model. Infant attention was assessed at 24 months of age using the Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire (ECBQ; Putnam, Gartstein, & Rothbart, 2006), which was reported by the child’s parent at the home visit. We included the ECBQ subscale of attention focusing (10 items; e.g., While looking at picture books on his/her own, how often did TC stay interested in the book for 5 minutes or less, α = .81). Each item was scored on a scale of one to seven (never, very rarely, less than half the time, about half the time, more than half the time, almost always, or always).

Maternal Language.

To control for the potentially confounding influence of maternal language during the EARS task on executive function outcomes, we included a maternal language input variable. Maternal language was coded from digital video recordings of the same EARS picture book sharing task that the joint attention measure was derived from at 24 months of age. The task was transcribed offline by trained graduate students using Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT; Miller & Chapman, 1985). A graduate student who spent 1 year learning SALT conventions and developing a training manual trained transcribers, who themselves trained for at least 3 months before transcribing videos. To ensure accuracy in the transcription process, coders transcribed 20 cases that were reviewed by the senior transcriber and transcripts were regularly reviewed and any issues were discussed and resolved with the senior graduate student (Kuhn et al., 2014). For coding purposes, utterances were defined as a sequence of words preceded and followed by a change in conversational turn or a change in into-nation pattern. Nonverbal utterances, unintelligible speech, and abandoned utterances were not included. Mean length utterance (MLU) was used in the current analysis as a measure of maternal language input. MLU is a general measure of language complexity that was calculated by dividing the total number of utterances by the total number or morphemes.

Maternal Education.

Primary caregivers’ highest education level was derived from self-reports at the home interview at the 7- and 15-month assessment. The mean level of educational attainment was 14.6 years (SD = 2.8 years), where 14 years reflected having earned a high school diploma. We averaged caregiver education values across the 7- and 15-month time point.

Maternal Job Prestige.

Caregivers’ job prestige level was derived from the home interview at the 7- and 15-month assessment. During this interview, primary caregivers were asked a series of questions about their current job(s), including the job title, employer and a short description of primary activities and duties. Jobs were given occupational codes according to the characteristics and attributes in The Occupational Information Network (O*Net) database. The O*Net database was used to create five specific occupational characteristics: self-direction, hazardous physical conditions, physical activity, care work, and automation/repetition. Intercoder reliability was adequate with correlation coefficients ranging from .80-.92 for the five summary scales. We averaged job prestige scores across the 7- and 15-month time point.

Demographics.

State of residence (PA = 0; NC = 1), sex (0 = Male; 1 = Female) and race (0 = not African American; 1 = African American) of the child were included as covariates to control for site and demographic differences in study variables.

Data Analysis

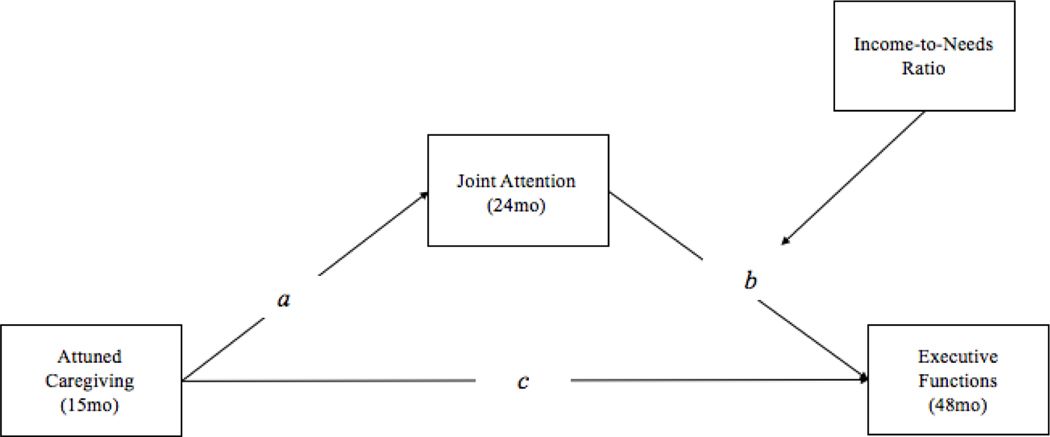

The total sample size recruited at study entry was 1,292, with 1,204 children seen at age 7 months, 1,169 at 15 months, 1,144 at 24 months, and 1,066 at 48 months. First, data were screened for outliers and normality of distributions. To avoid bias in estimates associated with listwise deletion, we used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) for all analyses. To address our main research questions, we used path analysis. In our hypothesized model (Figure 1), we were specifically interested in measuring: (1) the direct paths from attuned caregiving at 15 months to joint attention at 24 months (path a) and executive functions at 48 months (path c); (2) the direct paths from joint attention at 24 months to executive functions at 48 months (path b); (3) moderation of the path from joint attention at 24 months to executive function at 48 months by INR; (4) indirect paths from attuned caregiving to executive functions through joint attention; (5) moderated mediation of the indirect path from attuned caregiving to executive functions via conditional relations between joint attention and INR. Tests of statistical mediation employed bootstrapping with 5000 samples to generate bias-corrected confidence intervals for indirect effects (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). To test moderation, grand-mean centered scores were used to compute the interaction term and we probed statistically significant interactions at one standard deviation below (i.e., lower INR) and one standard deviation above (i.e., higher INR) the INR mean (Aiken & West, 1991). To control for the effect of infant attention and maternal language during the joint attention task on subsequent executive functions, we included infant focused attention and maternal language input as a covariate on path b. Finally, we controlled for caregiver education, job prestige, sex, state of residence, and race on all paths in our model. All analyses were conducted in the R environment (R Core Team, 2013) using the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012). All parameter estimates are standardized estimates and thus, indicate how much the dependent variable would be expected to change for a single standard deviation change in the predictor variable.

Figure 1.

The hypothesized moderated mediation model relating attuned caregiving to joint attention and executive outcomes, conditional on INR. Covariates are not shown.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and Table 2 displays correlations among the variables in the analysis. Table 2 indicates a positive association between attuned caregiving and joint attention, executive functions, infant focused attention, and maternal language. Further, attuned caregiving was positively correlated with INR, maternal education and job prestige. Joint attention was positively associated with executive functions, infant focused attention, maternal language, INR, maternal education, and job prestige. Executive functions were positively correlated with infant focused attention, maternal language, INR, maternal education, and job prestige. The reported correlation coefficients were in the hypothesized directions, thus providing support for subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| N | Mean | St. Dev. | Min | Median | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attuned Caregiving 15mos | 1,100 | 2.7 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 |

| Joint Attention 24mos | 1,078 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.0 |

| Executive Function 48mos | 1,009 | −0.1 | 0.5 | −2.1 | −0.1 | 1.2 |

| Maternal Education 7–15mos | 1,225 | 14.48 | 2.8 | 6.0 | 14.0 | 22.0 |

| INR 7–15mos | 1,228 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 16.6 |

| Job Prestige 7–15mos | 1,119 | 40.0 | 11.2 | 16.8 | 38.9 | 86.0 |

| Infant Focused Attention 24mos | 1,086 | 4.1 | 0.7 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 6.3 |

| Maternal Language Input 24mos | 1,047 | 3.1 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 8.8 |

Note. mos, months; INR, Income-to-Needs Ratio

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Attuned Caregiving 15mos | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Joint Attention 24mos | 0.18** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Executive Function 48mos | 0.28** | 0.23** | 1 | |||||

| 4. INR 7–15mos | 0.37** | 0.15** | 0.27** | 1 | ||||

| 5. Maternal Education 7–15mos | 0.41** | 0.16** | 0.30** | 0.54** | 1 | |||

| 6. Job Prestige 7–15mos | 0.31** | 0.13** | 0.24** | 0.52** | 0.56** | 1 | ||

| 7. Infant Focused Attention 24mos | 0.09* | 0.06* | 0.16** | 0.13** | 0.11** | 0.08* | 1 | |

| 8. Maternal Language Input 24mos | 0.15** | 0.08** | 0.08* | 0.06 | 0.12** | 0.06 | 0.01* | 1 |

Note.

indicates p < .05.

indicates p < .01; mos, months; INR, Income-to-Needs Ratio

Preliminary Analyses: Attuned Caregiving and Executive Functions

To assess the direct effects of attuned caregiving on executive function (without joint attention in the model), we constructed a regression of executive functions at 48 months on attuned caregiving at 15 months, controlling for all covariates. As hypothesized, attuned caregiving was positively associated with executive functions at 48 months (β=.09, SE=.02, p=.007).

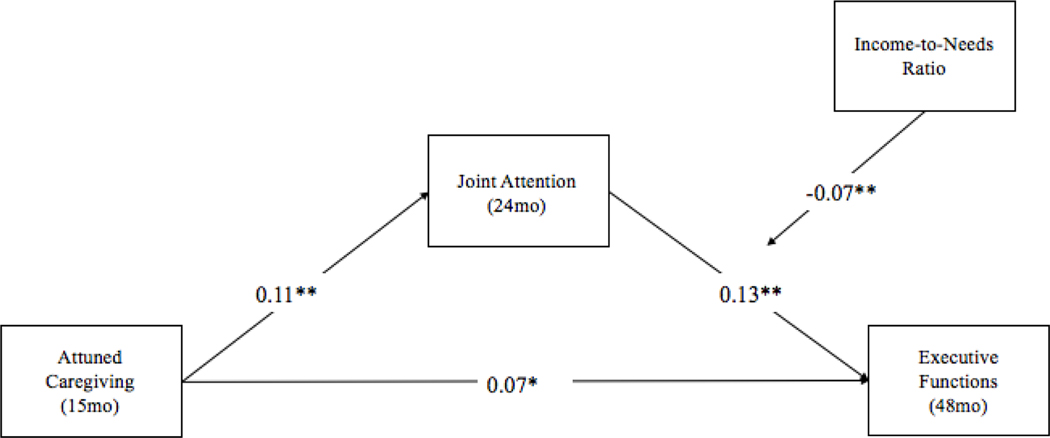

Path Analysis

To test our main hypotheses, we first examined the direct effects of attuned caregiving on joint attention and executive functions. Second, we examined direct effects of joint attention on executive function and explored the moderating role of INR while controlling for infant focused attention and maternal language input during the joint attention task. Third, we examined the indirect effects of attuned caregiving on executive function via joint attention and its interaction with INR. All effects are reported as standardized coefficients as shown in Table 3 and Figure 2.

Table 3.

Regression Results

| Standardized Estimates (Std. Err.) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Direct Paths | |

| Executive Function 48mos | |

| Attuned Caregiving 15mos | 0.07 (0.02) ** |

| Joint Attention 24mos | 0.13 (0.07) ** |

| INR 7–15mos | 0.01 (0.01) |

| INR 7–15mos X Joint Attention 24mos | −0.07 (0.04) ** |

| Maternal Education 7–15mos | 0.14 (0.01) ** |

| Job Prestige 7–15mos | 0.06 (0.02) |

| Infant Focused Attention 24mos | 0.10 (0.02) ** |

| Maternal Language Input 24mos | 0.07 (0.02) * |

| Sex | −0.14 (0.03) ** |

| State | −0.17 (0.04) ** |

| Race | −0.14 (0.04) ** |

|

| |

| Joint Attention 24mos | |

| Attuned Caregiving 15mos | 0.11 (0.01) ** |

| INR 7–15mos | 0.04 (0.01) |

| Maternal Education 7–15mos | 0.04 (0.01) |

| Job Prestige 7–15mos | 0.05 (0.01) |

| Sex | −0.06 (0.01) |

| State | −0.10 (0.02) ** |

| Race | 0.05 (0.02) |

|

| |

| Indirect Paths | Estimate (95% CI) |

| SP→JA→EF | 0.014 (.003, .017) |

| SP→JA*INR→EF | −0.008 (−.007, −.001) |

Note.

indicates p < .05.

indicates p < .01; mos, months; INR, Income-to-Needs Ratio

Figure 2.

The observed mediation model relating attuned caregiving to joint attention and executive outcomes, including moderation by INR. All coefficients are standardized (β). **p<.01, *p<.05; On the a path, we controlled for 7–15mo INR, maternal education, and job prestige, as well as sex, state, and race. On the b path, we controlled for 24mo infant focused attention and maternal language input and 7–15mo INR, maternal education, and job prestige as well as sex, state, and race.

Relations between Attuned Caregiving, Joint Attention, and Executive Functions

First, tests of direct effects demonstrated a significant positive association between attuned caregiving in infancy and executive functions in early childhood (β=.07, SE=.02, p=.036). Compared to the preliminary model without joint attention, the coefficient was reduced by 22% suggesting partial mediation through joint attention. Further, the model demonstrated a significant positive direct effect of attuned caregiving in infancy on joint attention in toddlerhood (β=.11, SE=.01, p=.001). Second, a significant direct effect was present between joint attention in toddlerhood and executive functions in early childhood, such that joint attention was positively associated with executive functions (β=.13, SE=.07, p<.001). There was also significant association between infant focused attention and executive functions (β=.10, SE=.02, p<.001) and for maternal language input during the joint attention task and executive functions (β=.07, SE=.02, p=.03).

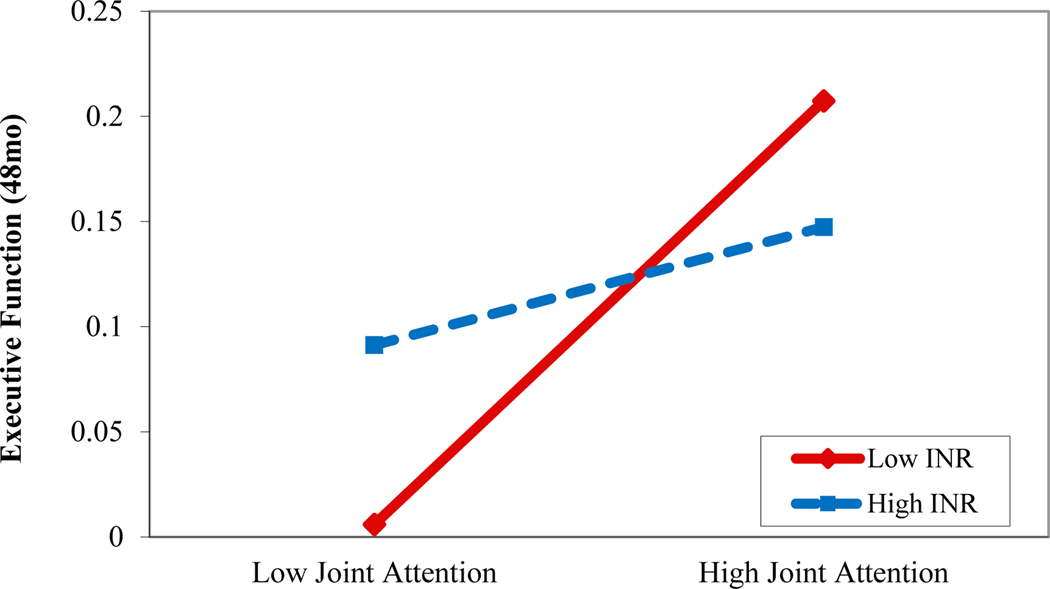

Income-to-Needs Ratio (INR) as a Moderator of Joint Attention

To examine the moderating role of INR on the relation between joint attention in toddlerhood and executive functions in early childhood, we estimated a second path model that included an interaction term for joint attention and INR as a predictor of executive functions. Tests of moderation demonstrated a significant interaction effect, such that the relation between joint attention and executive function was moderated by INR (β=−.07, SE=.04, p=.01). As shown in Figure 3, analysis of simple slopes indicated that the positive relation between joint attention and executive functions was stronger for families with lower INR (mean - 1 SD: (β=.20, SE=.08, p<.001). In contrast, for those with higher INR, the relation between joint attention and executive functions was smaller yet still significant (mean + 1 SD: β=.06, SE=.08, p=.02). These results indicate that the relation between joint attention and executive functions was approximately three times larger for low-income relative to high-income families.

Figure 3.

Family income-to-needs ratio (INR) moderates the association between joint attention at 24 months and executive function at 48 months. Model-estimated simple slopes are plotted at values of 1 standard deviation above (high) and below (low) the respective variable’s mean.

Test of Mediation through Joint Attention

To test for mediation in our model, we estimated the indirect effects of attuned caregiving in infancy to executive functions in early childhood through joint attention in toddlerhood. Results from tests of indirect effects unconditional on INR (Table 3) indicated that joint attention partially mediated the relation between attuned caregiving and executive functions (β=.014, 95% CI [.003, .017]).

Moreover, the tests of indirect effects conditional on INR demonstrated that the interactive effects between joint attention and INR partially mediated relations between attuned caregiving and executive functions (β=−.01, 95% CI [−.007, −.001]), such that the role of joint attention as a mediator was amplified among families with lower INR (mean - 1 SD; β=.02, 95% CI [.003, .023]) relative to individuals with higher INR (mean + 1 SD; β=.006, 95% CI [−.001, .013]).

Discussion

In the current study, we assessed longitudinal relations between attuned caregiving, joint attention and executive functions among families living in predominately rural, low-income environments. Specifically, we investigated joint attention during toddlerhood as a mediator between the relation of attuned caregiving during infancy to executive functions in early childhood and the extent to which income moderated this mediation. This research was motivated by the theory of joint attention as a guided attention mechanism that parents engage in with their infant to promote the basic building blocks of infant cognitive control. This foundational set of cognitive abilities may have long term developmental implications, particularly for children living in socioeconomic risk. We found evidence in support of our hypothesis that joint attention may be one operating mechanism by which attuned caregiver behaviors predict the development of higher-order cognitive abilities. Further, our findings support the hypothesis that the effect of joint attention would be amplified for children living in elevated poverty. While previous research has demonstrated associations between attuned caregiving and executive functions (Blair et al., 2011; Bernier, Carlson, & Whipple, 2010; Lugo-Gil & Tamis-LeMonda, 2008), we build upon these findings by examining joint attention in infancy, a particular contingent-responsive dyadic exchange, as a predictor of executive functions in early childhood, over and above individual infant focused attention and maternal language input. Collectively, our findings presented here in conjunction with other empirical research, support theories suggesting that it is through social interactions that infants develop the capacity for higher-order cognition and self-regulation (Fogel, 1993; Vygotsky, 1978).

Attuned Caregiving and Joint Attention

Results from our first path of interest demonstrated that attuned caregiving during infancy positively predicted joint attention in toddlerhood. While little research has been devoted to longitudinally studying early social influences on the development of joint attention, our findings are substantiated by theory and emerging empirical research. In particular, joint attention has theoretically been conceptualized as a behavioral manifestation of contingent-responsive synchrony between infants and caregivers that develops over time (Bolis & Schilbach, 2018). Attuned caregiver behaviors are characterized by adaptive and flexible affect, attention, and responsiveness to the infant. These practices are especially important in the first months of an infant’s life before the mature development of self-directed joint attention. The association between early-life attuned caregiving and joint attention in early toddlerhood provides empirical evidence that behaviorally attuned caregiving qualities may set the foundation for the development of joint attention. Specifically, throughout infancy, the caregiver and infant engage in a ‘dance’ of attention and affect matching during face-to-face interactions (Tronick & Cohn, 1989) that developmentally precede the onset of joint attention. Moreover, the development of shared visual attention towards objects may depends on the history of the dyad’s reciprocity and attentional attunement, which is co-constructed early in life during sensitive caregiver interactions (Raver & Leadbeater, 1995). Here we find empirical evidence to support this theory given that our measurement of attuned caregiving is characterized by highly attuned, affective, and attentive behaviors during interactions. This inference is empirically supported with evidence that attuned mothers are more sensitive and responsive to their infants by providing higher quality and greater quantity of affective and intentional cues, thus setting the stage for contingent gaze following during joint attention (Legerstee, Markova, & Fisher, 2007). A caregiver’s sensitivity to their infant’s cues likely contributes to their ability to capture and guide their infant’s attention, thereby scaffolding the infant’s training of shared social attention, which may further contribute to the development of joint attention over time. Through this dynamic, interpersonal process, caregivers and infants co-construct the building blocks of cognition.

Joint Attention and Executive Functions

Results from our second path of interest indicated that greater joint attention at 24 months longitudinally predicted greater executive function abilities at 48 months while also controlling for early life attuned caregiving, infant focused attention, and maternal language input during the joint attention task. This finding adds to a recent, growing body of literature suggesting that joint attention may be an important mechanism whereby infants develop higher order cognitive abilities (Niedźwiecka, Ramotowska, & Tomalski, 2017; Vaughan Van Hecke et al., 2012). In other words, it is not only attuned caregiving alone that predicts executive functions; there is an additional, unique effect of joint attention. One possible explanation for these findings is that joint attention between infants and caregivers functions as a guided attention mechanism whereby parents scaffold basic components of cognitive control with their infants. This idea is supported by empirical evidence from gaze-tracking research, which has demonstrated that infants prolong sustained gaze towards objects when their parents have focused attention on the same object (Wass, 2018; Yu, 2016). In essence, parents may be training and fine-tuning attentional control in infancy through joint attention, thus setting the foundation for higher-order cognitive abilities in early childhood. Recent evidence from neuroscience supports the theory of socially constructed cognitive control development. Specifically, Wass et al. (2018) demonstrated that increases in caregiver’s theta power (a biomarker of attention measured by EEG) during a bout of joint attention predicted subsequent infant gaze duration directed towards the same object. In other words, infant’s sustained attention is potentiated in joint attention contexts when the mature dyadic partner allocates greater neurophysiological resources to the shared object. These findings provide neural evidence for the process by which joint attention scaffolds and trains higher-order attentional control.

Our mediational findings support our central hypothesis that joint attention is a specific operating mechanism of attuned caregiver interactions that scaffold early cognitive abilities. This finding is well situated within a rich body of literature linking sensitive parenting practices to executive function outcomes in early childhood (Blair et al., 2011; Bernier, Carlson, & Whipple, 2010; Lugo-Gil & Tamis-LeMonda, 2008). Moreover, these findings are consistent with broader theory emphasizing the role of social interactions in the development of executive functions (Fernyhough 2010; Hughes and Ensor 2007; Lewis and Carpendale 2009; Perry et al. 2018, Vygotsky, 1978). Given that we assessed and defined joint attention on the level of the dyad during a structured social interaction, our findings point to the interactional process of joint attention as a specific component of attuned caregiving that scaffolds executive function development (Rosen, 2019). Importantly, because our analysis is longitudinal, we can also claim that earlier attuned caregiving may support the development of joint attention, and in turn this joint attention may support the development of executive functions. That is, caregiver attunement in infancy may foster the development of joint attention in toddlerhood, which supports executive function in early childhood. Further, it is not merely attuned caregiving alone that supports executive function, but attuned caregiving through joint attention. This further highlights the idea that although caregivers contribute significantly, it is not the caregiver alone supporting executive functions development, but the interactional nature of exchanges between both the caregiver and child. Reciprocally, the ability to attend to social cues is advantageous for infants as they develop social-communicative abilities (Carpenter, et al. 1998; Miller & Gros-Louis, 2013). As such, the development of attention in infancy may be co-constructed through attuned social interactions with caregivers during which the caregiver’s and child’s attention processes are attuned or synchronous with each other. We propose that it is through these repeated instances of joint attention or attentional synchrony that infants are able to develop their own ability for independent cognitive control and executive functions. Future longitudinal research is needed to empirically test this hypothesis.

Moderation by Income-to-Needs

Our findings also contribute to growing literature on joint attention and executive function development by assessing the moderating role of INR. Specifically, we found that the relation between toddler’s joint attention and early childhood executive functions was moderated by INR such that the positive association between joint attention and executive functions was greater for families with lower INR. This relation indicates an amplifying effect whereby the positive effects of joint attention on executive functions provide an additional boost for low-income children. We posit that this could reflect the critical effects of insufficient materials and resources in the home environment for families living with low-incomes. In other words, lower-income families may have fewer financial resources to invest in learning materials, such as toys and books. Thus, in homes with fewer cognitively enriching material resources, the child may reap more benefits from social interactions involving joint attention to scaffold the foundational building blocks of cognition (Rosen, 2019). Further evidence for this hypothesis comes from our moderated mediation finding demonstrating that the role of joint attention as a mechanism through which attuned caregiving relates to executive function was particularly strong for low-income families. Therefore, in low-income homes that may be strained by a lack of resources, children may rely more on social interactions and reap more of the cognitive benefits associated with joint attention from attuned caregivers. These findings highlight the importance of fostering well-resourced, supportive, and low-stress environments that are conducive to attuned caregiving and joint attention, particularly for low-income families and during early life when the brain is especially plastic and susceptible to social influence (Cerqueira, Mailliet, Almeida, Jay, & Sousa, 2007; Grossmann, 2013; Hodel, 2018).

One of the strengths of the current study is the longitudinal analysis, which allows us to establish temporal precedence that may support a causal relation. While the reported pathways are correlational, establishing temporal precedence strengthens our ability to infer a potentially causal relation in which joint attention operates as a causal mechanism by which attuned caregiving impacts executive function. Intervention research efforts have offered preliminary support for a casual role of dyadic, shared attention experiences in the development of higher-order cognitive abilities. Specifically, an randomized control trial intervention conducted by Cooper et al. (2014) implemented a book-sharing intervention for 14–16 month infants and caregivers living in impoverished South African communities. After 8 weeks of the book-sharing intervention, infants demonstrated gains in sustained attention relative to the infants in the control group. While this work did not specifically target joint attention, book reading allows for opportunities for joint attention, as observed in the current study, and likely may have contributed to the observed gains in sustained attention. Collectively, not only do these findings highlight a potential casual role for shared attention but also invite future research efforts to explore joint attention as a point of leverage for intervention research aimed a lower-income, at-risk populations. Additionally, because we found joint attention to be an important process likely supporting the development of executive functions especially for lower-income families, interventions targeting joint attention may be particularly useful for attenuating the disparities in executive functions associated with socioeconomic status.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study expands the literature, there are several limitations that should be addressed to inform future research efforts. First, our operationalization of joint attention was relatively broad given that a moment of joint attention was defined as the caregiver and infant both looking at the book. From this coding scheme, we are unable to glean detailed information as to who initiated joint attention or when gaze following occurred. However, this is an inherent limitation of collecting data in the field. Thus, we suggest that this shortcoming was offset by the fact that we assessed joint attention in a naturalistic interaction and ecologically valid context (in the home). Similarly, our measurement of attuned caregiving used a global coding scheme of behaviors. Future research examining attuned caregiving and joint attention could aim to micro-analyze the moment-to-moment dyadic behaviors as they unfold within the interaction. Further, analyses of joint attention would be bolstered by the inclusion of eye-tracking or dual neurophysiology measures to better understand the nuanced but rich features within joint attention interactions that may be particularly important for guiding attention In addition, future research could investigate if joint attention is more strongly predictive of specific domains of EF (i.e., working memory, inhibitory control, or attention shifting). Similarly, future research is needed to disentangle the factors from low-income environments that might be contributing to moderation of the relation between joint attention and executive functions. Importantly, the longitudinal model presented here is correlational. While the consideration and inclusion of infant focused attention and maternal language covariates improves our ability to draw inferences, causal conclusions about the relations between variables are not possible. Therefore, future experimental research is needed to evaluate causality regarding the links between caregiver behaviors, joint attention, and development of executive functions. Lastly, it is important to note that the effect sizes in our main analyses were relatively small. However, despite small effect sizes, we emphasize that the observed associations are reliably estimated given that we had a large sample size. Indeed, one of the strengths of a larger sample such as the Family Life Project is the increased statistical power to detect small but meaningful associations between constructs, which is inherently difficult in collecting longitudinal data in the field.

Despite these limitations, the present study has a number of strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to highlight joint attention as a key operating mechanism connecting caregiver attunement to the development of executive functions among families living in socioeconomic-related risk. Moreover, we used an ecologically valid measure of joint attention as it might naturally occur in the home environment, during a book reading task. This expands the literature, given that joint attention is typically studied within lab environments. However, it is through experiences like book reading activities, or prolonged play opportunities in the home environment, that infants develop and begin to demonstrate sustained and executive attention. We consider the possibility that the developmental process of joint attention between infant-caregiver dyads is a mechanism by which infants learn to regulate their attentional control through a guided attention process. Further, we propose joint attention to be an important process of social regulation in which caregivers scaffold an infant’s abilities, but together both caregiver and child co-construct higher-order cognitive processes, such as executive function.

References

- Aiken LS West SG Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, & Adamson LB (1984). Coordinating attention to people and objects in mother-infant and peer-infant interaction. Child Development, 55(4), 1278–1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Carlson SM, & Whipple N. (2010). From external regulation to self-regulation: Early parenting precursors of young children’s executive functioning. Child Development, 81(1), 326–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01397.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Carlson SM, Deschênes M, & Matte-Gagné C. (2012). Social factors in the environment. Developmental Science, 15(1), 12–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Granger DA, Willoughby M, Mills-Koonce R, Cox M, Greenberg MT, ... & FLP Investigators. (2011). Salivary cortisol mediates effects of poverty and parenting on executive functions in early childhood. Child Development, 82(6), 1970–1984. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01643.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, & Raver CC (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: A developmental psychobiological approach. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 711–731. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, & Raver CC (2016). Poverty, stress, and brain development: New directions for prevention and intervention. Academic Pediatrics, 16(3), S30–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolis D, & Schilbach L. (2018). Observing and participating in social interactions: action perception and action control across the autistic spectrum. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 29, 168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein M, & Bradley R. (2003). Socioeconomic Status, Parenting, and Child Development. New York: Routledge, doi: 10.4324/9781410607027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, & Tamis-Lemonda CS (1997). Maternal responsiveness and infant mental abilities: Specific predictive relations. Infant Behavior and Development, 20(3), 283–296. doi: 10.1016/S0163-6383(97)90001-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpendale A. R. Young, & Iarocci G. (Eds.), Self and social regulation: Social interaction and the development of social understanding and executive functions (pp. 56–79). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter M, Nagell K, Tomasello M, Butterworth G, & Moore C. (1998). Social cognition, joint attention, and communicative competence from 9 to 15 months of age. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, i–174. doi: 10.2307/1166214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira JJ, Mailliet F, Almeida OFX, Jay TM, & Sousa N. (2007). The prefrontal cortex as a key target of the maladaptive response to stress. Journal of Neuroscience, 27, 2781–2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, & Crnic K. (2002). Qualitative ratings for parent-child interaction at 3–12 months of age. Unpublished manuscript, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper PJ, Vally Z, Cooper H, Radford T, Sharples A, Tomlinson M, & Murray L. (2014). Promoting mother–infant book sharing and infant attention and language development in an impoverished South African population: a pilot study. Early Childhood Education Journal, 42(2), 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Fay-Stammbach T, Hawes DJ, & Meredith P. (2014). Parenting influences on executive function in early childhood: A review. Child Development Perspectives, 8(4), 258–264. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feagans LV, Kipp E, & Blood I. (1994). The effects of otitis media on the attention skills of day-care-attending toddlers. Developmental Psychology, 30(5), 701. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.30.5.701 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R. (2007). Parent–infant synchrony and the construction of shared timing; physiological precursors, developmental outcomes, and risk conditions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(3-4), 329–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01701.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, & Eidelman AI (2009). Biological and environmental initial conditions shape the trajectories of cognitive and social-emotional development across the first years of life. Developmental Science, 12(1), 194–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00761.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernyhough C. (2010). Vygotsky, Luria, and the social brain. Self and social regulation: Social interaction and the development of social understanding and executive functions, 56–79. [Google Scholar]

- Finegood ED, Blair C, Granger DA, Hibel LC, & Mills-Koonce R. (2016). Psychobiological influences on maternal sensitivity in the context of adversity. Developmental Psychology, 52(7), 1073. doi: 10.1037/dev0000123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel A. (1993). Developing through Relationships. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann T. (2013). Mapping prefrontal cortex functions in human infancy. Infancy, 18, 303–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hodel AS (2018). Rapid infant prefrontal cortex development and sensitivity to early environmental experience. Developmental Review, 48, 113–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostinar CE, Sullivan RM, & Gunnar MR (2014). Psychobiological mechanisms underlying the social buffering of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis: A review of animal models and human studies across development. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 256. doi: 10.1037/a0032671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C, & Devine RT (2019). For Better or for Worse? Positive and Negative Parental Influences on Young Children’s Executive Function. Child Development, 90(2), 593–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CH, & Ensor RA (2009). How do families help or hinder the emergence of early executive function?. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2009(123), 35–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C, and Ensor R. (2007). Executive function and theory of mind: predictive relations from ages 2 to 4. Developmental Psychology, 43, 1447–1459. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn LJ, Willoughby MT, Wilbourn MP, Vernon- Feagans L, Blair CB; The Family Life Project Key Investigators. (2014). Early communicative gestures prospectively predict language development and execu- tive function in early childhood. Child Development, 85, 1898–1914. 10.1111/cdev.12249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, & Smith KE (2010). Early social and cognitive precursors and parental support for self-regulation and executive function: Relations from early childhood into adolescence. In Sokol BW, Müller U, Carpendale JIM, Young AR, & Iarocci G. (Eds.), Self and social regulation: Social interaction and the development of social understanding and executive functions (p. 386–417). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195327694.003.0016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Legerstee M, Markova G, & Fisher T. (2007). The role of maternal affect attunement in dyadic and triadic communication. Infant Behavior and Development, 30(2), 296–306. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.10.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, and Carpendale JI (2009). Introduction: links between social interaction and executive function. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development,2009(123), 1–15. doi: 10.1002/cd.232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Gil J, & Tamis-LeMonda CS (2008). Family resources and parenting quality: Links to children’s cognitive development across the first 3 years. Child Development, 79(4), 1065–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01176.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network (1999). Child care and mother–child interaction in the first 3 years of life. Developmental Psychology, 35(6), 1399–1413 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markova G, & Legerstee M. (2006). Contingency, imitation, and affect sharing: Foundations of infants’ social awareness. Developmental Psychology, 42(1), 132. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M (2001). The New Baby. Random House Books for Young Reader. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer G & Mayer M. (2003). Just a Thunderstorm. Golden Books. [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, & Chapman R. (1985). Systematic analysis of language transcripts. Madison, WI: Language Analysis Laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JL, & Gros-Louis J. (2013). Socially guided attention influences infants’ communicative behavior. Infant Behavior and Development, 36(4), 627–634. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy P, & Newell L. (2007). Attention, Joint Attention, and Social Cognition. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(5), 269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedźwiecka A, Ramotowska S, & Tomalski P. (2018). Mutual gaze during early mother–infant interactions promotes attention control development. Child Development, 89(6), 2230–2244. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry RE, Blair C, & Sullivan RM (2017). Neurobiology of infant attachment: Attachment despite adversity and parental programming of emotionality. Current Opinion in Psychology, 17, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry RE, Braren SH, Blair C, & the Family Life Project Key Investigators (2018).Socioeconomic Risk and School Readiness: Longitudinal Mediation Through Children’s Social Competence and Executive Function. Frontiers in Psychology, 9:1544. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry RE, Finegood ED, Braren SH, DeJoseph ML, Putrino DF, Wilson DA, … & Family Life Project Key Investigators. (2019). Developing a neurobehavioral animal model of poverty: Drawing cross-species connections between environments of scarcity-adversity, parenting quality, and infant outcome. Development and Psychopathology, 31(2), 399–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, & Petersen SE (1990). The Attention System of the Human Brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 13(1), 25–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Gartstein MA, & Rothbart MK (2006). Measurement of fine-grained aspects of toddler temperament: the early childhood behavior questionnaire. Infant Behavior & Development, 29(3), 386–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC, & Leadbeater BJ (1995). Factors influencing joint attention between socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescent mothers and their infants. Joint Attention: Its Origins and Role in Development, 251–271. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy V, Hay D, Murray L, & Trevarthen C. (1997). Communication in infancy: Mutual regulation of affect and attention. In Bremner G. (Ed.), Infant development: Recent Advances, (pp (Vol. 339, pp. 247–273). [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades BL, Greenberg MT, Lanza ST, & Blair C. (2011). Demographic and familial predictors of early executive function development: Contribution of a person-centered perspective. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 108(3), 638–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5–12 (BETA). Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ML, Amso D, & McLaughlin KA (2019). The role of the visual association cortex in scaffolding prefrontal cortex development: A novel mechanism linking socioeconomic status and executive function. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 39, 100699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaife M, & Bruner JS (1975). The capacity for joint visual attention in the infant. Nature, 253(5489), 265–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert JM, Hogan AE, & Mundy PC (1982). Assessing interactional competencies: The early social-communication scales. Infant Mental Health Journal, 3(4), 244–258. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, and Bolger N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. doi: 10.1037//1082-989X.7.4.422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter CA, & Corey JM (2001). Vagal regulation and observed social behavior in infancy. Social Development, 10(2), 189–201. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Team, R. C. (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Internet]. 2013. Disponible sur: http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M. (1995). Joint attention as social cognition. Joint attention: Its Origins and Role in Development, 103130. [Google Scholar]

- Trevarthen C. (1979). Communication and cooperation in early infancy: A description of primary intersubjectivity. Before Speech: The Beginning of Interpersonal Communication, 1, 530–571. [Google Scholar]

- Tronick EZ, & Cohn JF (1989). Infant-mother face-to-face interaction: Age and gender differences in coordination and the occurrence of miscoordination. Child Development, 85–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb02698.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hecke AV, Mundy P, Block JJ, Delgado CE, Parlade MV, Pomares YB, & Hobson JA (2012). Infant responding to joint attention, executive processes, and self-regulation in preschool children. Infant Behavior and Development, 35(2), 303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon-Feagans L, Cox M, & the Family Life Project Investigators. (2013). The Family Life Project: An epidemiological and developmental study of young children living in poor rural communities. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, Vol. 78, No 5, Serial No. 310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS 1975. Mind in society. The development of higher psychological processes, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS (1978). Mind in society (Cole M, John-Steiner V, Scribner S, & Souberman E, Eds.). [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS (1979). The Development of Higher Forms of Attention in Childhood. Soviet Psychology, 18(1), 67–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wass SV, Noreika V, Georgieva S, Clackson K, Brightman L, Nutbrown R, et al. (2018) Parental neural responsivity to infants’ visual attention: How mature brains influence immature brains during social interaction. PLoS Biology, 16(12): e2006328. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wass SV, Clackson K, Georgieva SD, Brightman L, Nutbrown R, & Leong V. (2018). Infants’ visual sustained attention is higher during joint play than solo play: is this due to increased endogenous attention control or exogenous stimulus capture? Developmental Science, 21(6), e12667. doi: 10.1111/desc.12667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby MT, Blair CB, Wirth RJ, & Greenberg M. (2010). The measurement of executive function at age 3 years: Psychometric properties and criterion validity of a new battery of tasks. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 306–317.doi: 10.1037/a0018708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby MT, Blair CB, Wirth RJ, & Greenberg M. (2012). The measurement of executive function at age 5: Psychometric properties and relationship to academic achievement. Psychological Assessment, 24(1), 226–239. doi: 10.1037/a0025361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby M, Holochwost SJ, Blanton ZE, & Blair CB (2014). Executive Functions: Formative Versus Reflective Measurement. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives, 12(3), 69–95.doi: 10.1080/15366367.2014.929453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby M, Kupersmidt J, Voegler-Lee M, & Bryant D. (2011). Contributions of hot and cool self-regulation to preschool disruptive behavior and academic achievement. Developmental Neuropsychology, 36(2), 162–180. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2010.549980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby MT, Magnus B, Vernon-Feagans L, & Blair CB (2016). Developmental Delays in Executive Function from 3 to 5 Years of Age Predict Kindergarten Academic Readiness. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 50(4), 359–372.doi: 10.1177/0022219415619754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby MT, Wirth RJ, & Blair CB (2011). Contributions of modern measurement theory to measuring executive function in early childhood: An empirical demonstration. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 108(3), 414–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C, & Smith LB (2016). The Social Origins of Sustained Attention in One-Year-Old Human Infants. Current Biology, 26(9), 1235–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]