Abstract

Our daily rhythmicity is controlled by a circadian clock with a specific set of genes located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the hypothalamus. Mast cells (MCs) are major effector cells that play a protective role against pathogens and inflammation. MC distribution and activation are associated with the circadian rhythm via two major pathways, IgE/FcεRI- and IL-33/ST2-mediated signaling. Furthermore, there is a robust oscillation between clock genes and MC-specific genes. Melatonin is a hormone derived from the amino acid tryptophan and is produced primarily in the pineal gland near the center of the brain, and histamine is a biologically active amine synthesized from the decarboxylation of the amino acid histidine by the L-histidine decarboxylase enzyme. Melatonin and histamine are previously reported to modulate circadian rhythms by pathways incorporating various modulators in which the nuclear factor–binding near the κ light-chain gene in B cells, NF-κB, is the common key factor. NF-κB interacts with the core clock genes and disrupts the production of pro-inflammatory cytokine mediators such as IL-6, IL-13, and TNF-α. Currently, there has been no study evaluating the interdependence between melatonin and histamine with respect to circadian oscillations in MCs. Accumulating evidence suggests that restoring circadian rhythms in MCs by targeting melatonin and histamine via NF-κB may be promising therapeutic strategy for MC-mediated inflammatory diseases. This review summarizes recent findings for circadian-mediated MC functional roles and activation paradigms, as well as the therapeutic potentials of targeting circadian-mediated melatonin and histamine signaling in MC-dependent inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: circadian rhythm, clock genes, histamine, inflammation, mast cells, melatonin

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Mast cells (MCs) are derived from multipotent hematopoietic progenitor cells in the bone marrow and involved in innate immunity.1 The migration of MC progenitors into target tissues and their proliferation and activation are critically regulated by stem cell factor (SCF) recognized by its receptor c-Kit, a type III tyrosine kinase broadly expressed on mature MCs.2 Other factors contributing to MC abundancy and localization and/or phenotypic characteristics are transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)3; integrins4; C-X-C motif chemokine receptors including CXCR2, CXCR3, CXCR4, and CXCR55; and selected interleukins (IL) such as IL-36 and IL-33.7 MCs are historically considered key effector cells of allergic reactions employing the immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated activation pathway.8 MCs are associated with regulation of immunity and inflammation by releasing important inflammatory mediators, including histamine, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), IL-6, and IL-8.9 There is also evidence indicating the expression of sex hormone receptors including estrogen, estradiol, and progesterone receptors in human MCs.10 Activation of MCs is generally classified into two mechanisms based on the link to the adaptive immune system. The most extensively studied mechanism is the antigen-specific immunoglobulin E-bound/high-affinity receptor for the Fc region of immunoglobulin E (IgE/FcεRI)–mediated signaling which plays a central role in allergic responses and diseases.8 The most recently discussed paradigm independent of the adaptive immune system is the IL-33/suppressor of tumorigenicity 2 (IL-33/ST2).11 There are studies supporting an emerging role of MC activation following IgE-independent pathways in non-allergic diseases such as late-stage asthmatic response, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and lung cancer.12

Recent research has clarified that MC quantity and activity are controlled by daily rhythmic variation,13 a circadian clock under the regulation of a specific set of clock genes such as Circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (Clock), brain and muscle aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator–like 1 (Bmal1), Period (Per1/2) and Cryptochromes (Cry1/2), and environmental factors, such as light intensity and nutritional input.8 The circadian clock is an internal cellular time-keeper cycle located in the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN), a bilateral structure in the anterior part of the hypothalamus. It is driven by a series of cell-autonomous clock genes and responsible for the coordination of almost all physiological activities.14 The components of the mammalian circadian clock including a central pacemaker in the brain's SCN and peripheral clocks in the cells of most organs and tissues, as well as their connections to major processes in pathophysiological and metabolic systems, were identified using the well-characterized Mus musculus mouse model.15 Clock was the first gene identified in the circadian rhythm using C57BL/6J male mice treated with a single injection of N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU).16 From this foundational discovery , a series of mouse circadian clock and clock-related genes were identified including Bmal1, Per1/2/3, Cry1/2, Casein kinase (CK1ε and CK1δ), Differentiation of human embryo chondrocytes (Dec1/2), Retinoic acid-related orphan receptor (Rorα, Rorβ, and Rorγ), Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 (NR1D1 or Rev-erbα), Neuronal PAS domain protein 2 (NPAS2), Timeless (Tim), and F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 3 (Fbxl3).17 The core loop of the circadian clock contains two nuclear transcription factors, CLOCK and BMAL1, binding as a heterodimer to the E-box elements in Per1/2/3 and Cry1/2 genes and activating the Per1/2/3 and Cry1/2 transcriptions. In the cytoplasm, PER and CRY proteins form an active repressor complex acting on the CLOCK/BMAL1 negative feedback loop which in turn inhibits Per1/2/3 and Cry1/2 expressions.18 The transcriptional-translational feedback network plays an important role in the generation and maintenance of circadian rhythm.

Located near the center of the brain, the pineal gland is a very small organ producing melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine), which helps maintain circadian rhythm and regulate reproductive hormones.19 Melatonin is a hormone derived from the amino acid tryptophan with potential applications for early prevention of neurodegenerative diseases20 and human diseases of the biliary tract21 including primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and cholangiocarcinoma (CCA). It also possesses strong antioxidant capacity and activates two high-affinity G protein–coupled receptors in mammals, MT1 and MT2, which in turn inhibit downstream processes such as forskolin-stimulated cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production.22,23 Melatonin is one of several neurotransmitters and neuromodulators participating in the regulation of circadian rhythms, especially in the sleep-wake pattern.24 Aberrant timed melatonin production has a strong connection to the non-24 hours sleep-wake disorder, advanced sleep phase syndrome, and delayed sleep phase syndrome.25 Actions at the two melatonin receptors MT1 and MT2 lead to sleep promotion by inducing sleep-like brain waves, as well as the improved phase shift of circadian oscillations.26

Histamine (2-(1H-imidazol-4-yl)ethanamine) is a biologically active nitrogenous-based compound synthesized from the decarboxylation of the amino acid histidine by the L-histidine decarboxylase (HDC) enzyme. Both histamines released by MCs and HDC play an important role in inflammatory responses.27 Histamine binds to four protein-coupled histamine receptors (HR), H1-4HRs, in which H1-3HRs are expressed in brain.28 Though histamine was first reported in the brain half a decade ago, only recently have researchers discovered histamine's role as a key wake-promoting neurotransmitter in the sleep-wake behavior.29 Valko et al30 reported a 41% reduction of histamine neurons in the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN) of traumatic brain injury victims. They also suggested the inverse correlation between histamine signaling and sleep need. This finding was further confirmed by a ~36% loss of histamine immunoreactive neurons in the TMN of adult male Sprague Dawley rats that underwent electro-encephalography/electromyography.31 While studying larval zebrafish, that possess a mutation in HDC gene leading to deficiency of histamine production, Prober et al32 found contradicting data that the zebrafish experienced remarkably normal sleep-wake patterns. Nevertheless, there is rapidly growing evidence to identify histamine as an important neuromodulator of the sleep-wake behavior and potential targets in allergic diseases and epilepsy therapy.33

2 ∣. MECHANISMS OF CIRCADIAN RHYTHM–MEDIATED MC ACTIVATION

2.1 ∣. Circadian clock in MCs

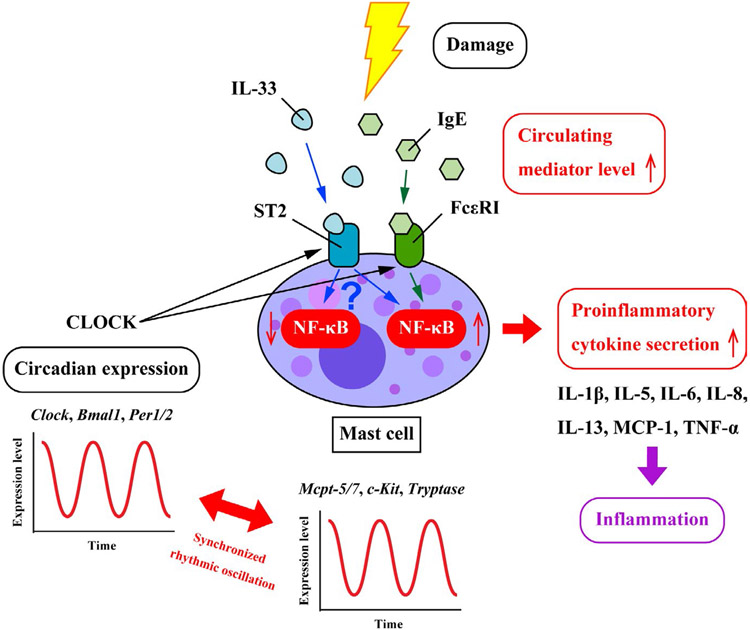

The connections between MCs and the circadian clock were first reported in the rat-thyroid gland13 and have been extensively studied since then.34 Mouse jejunal MCs from peripheral blood were isolated to study the robust oscillation between circadian clock genes (Per1/2, Clock, and Bmal1) and MC-specific genes (Mcpt-5/7, c-Kit, and FcεRIα). In purified human MCs from intestinal tissue samples, similar circadian variations were also observed between the clock genes (Per1/2 and Bmal1) and MC-related genes (FcεRIα and Tryptase).35 Downstream targets of circadian functions in MCs are pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α,36 IL-1β,37 and chloride channel accessory 1 (CLCA1 or GOB5).36 There are a significant number of studies focusing on mechanisms underlying the modulation of the circadian clock and MC functions, of which IgE/FcεRI-mediated MC activation and IL-33/ST2-mediated MC activation are the two main pathways.34,38 The promoter regions of β subunit of the Fc receptor for IgE (FcεRIβ) and IL-33 receptor (ST2) bind CLOCK with high affinity leading to a circadian rhythm–dependent MC activation (Figure 1).39 Other activation paradigms include H1-4HRs,40-42 Mas-related G protein–coupled receptor X-2 (MRGPRX2),43 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase 1 (OGG1),44 and MC-possessed potentiation which is not related to the adaptive immune system.11

FIGURE 1.

IgE/FcεRI- and IL33/ST2-mediated MC activation pathways. There is a robust oscillation between the circadian clock genes (Per1/2, Clock, and Bmal1) and MC-specific genes (Mcpt-5/7, c-Kit, FcεRI, and Tryptase). IgE/FcεRI- and IL-33/ST2-mediated MC activations are the two major pathways underlying the modulation of the circadian clock and MC functions. The promoter of β subunit of the Fc receptor for IgE (FcεRIβ) and IL-33 receptor (ST2) bind CLOCK with high affinity leading to a circadian rhythm-dependent MC activation. Upon the respective binding of IgE and IL-33 to FcεRI and ST2 in MCs, the expression level of the nuclear factor NF-κB is significantly elevated leading to the increase in the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-5/6/8/13, and MCP-1. IL-33 exhibits dualistic effect in MCs with ability to both inducing and suppressing NF-κB activity. More studies are required to decipher this dichotomous effect to avoid putative false therapeutic drugs targeting the IL-33/ST2 axis in MCs.

2.2 ∣. IgE/FcεRI-mediated MC pathway

The FcεRI receptor is an αβγγ tetramer on the surface of MCs and basophils with one α chain for IgE binding and one β and two γ for signal amplification and transduction.45 In MCs, FcεRIα and FcεRIβ are the key IgE receptors with high binding affinity in addition to FcγRII, FcγRIII (in mice only), and galectin-3.34 Human and mouse MCs with high oscillating concentration of IgE possess a high number of FcεRI receptors on the surface since the binding of IgE to FcεRI protects these receptors from being internalized and degraded which stabilizes them.46 Other researchers proposed that the IgE-dependent circadian synthesis and release of cytokines and chemokines in MCs are mediated indirectly by clock genes through the activation of various signaling molecules such as the extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK1/2),47 p38 mitogen–activated protein kinase (MAPK),48 and protein kinase B (Akt or PKB).48

In allergic reactions, MC activation was reported to follow the IgE/FcεRI signaling pathway.8,49 The significant amplifying role of FcεRIβ for IgE-mediated MC functions was identified using a mouse model repeating the tissue distribution of human FcεRI trimeric and tetrameric forms.50 However, the first evidence identifying the direct link of IgE antibodies in MC-mediated reaction under the regulation of circadian rhythms was published by Nakamura et al51 in a study on cutaneous anaphylactic reactions. Utilizing a loss-of-function mutation of Per2 (mPer2m/m) mouse model, the authors reported an aberrancy in the daily variation of serum corticosterone and a reduction in the bone marrow–derived MCs (BMMCs) sensitivity to the glucocorticoid inhibition both in vitro and in vivo suggesting Per2 may regulate MCs. Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of dexamethasone on IgE-mediated β-hexosaminidase release in BMMCs was not observed for the mPer2m/m mice as opposed to the wild type (WT).51 Consistent data were presented showing expression levels of several clock genes, such as Per1/2, Bmal1, Reverb, and Dbp oscillated in murine BMMCs. Specifically, the expression of IL-13 and IL-6 mRNA exhibits circadian rhythms upon the stimulation of synchronized BMMCs with high-affinity IgE receptor FcεRIα.52 The result indicated the IgE/FcεRIα signaling pathway as the underlying mechanism for MC activation under regulation of the circadian clock (Figure 1).

The details of temporal regulation of IgE-mediated activation in MCs remained elusive until Nakamura et al39 reported a novel regulatory mechanism suggesting IgE-mediated degranulation in MCs is primarily driven by the peripheral circadian clock in allergic reactions both in vivo and in vitro. The authors observed circadian oscillation in mRNA expression of Per2 and FcεRIβ in WT bone marrow–derived cultured MCs (BMCMCs), but not in Clock-mutated (ClockΔ19/Δ19) BMCMCs, indicating that the Clock mutation in MCs accounts for the significant disruption of temporal variation in IgE/FcεRIβ-mediated degranulation of MCs. However, that phenomenon was not observed in the same experiments using Clock-deleted (Clock siRNA treated) BMCMCs, a model with less severe interference to the circadian rhythmicity. The authors stated that Clock binds to the promoter of FcεRIβ based on two key findings (a) the reduction of FcεRIβ mRNA expression level in association with the decrease of IgE-mediated β-hexosaminidase in ClockΔ19/Δ19 BMCMCs and (b) the enhancement of FcεRIβ promotor activity due to Clock overexpression in WT BMCMCs.39 Different approaches for potential pharmacological drugs treating IgE/FcεRI-mediated allergic reactions were proposed by targeting the MC molecular clock,53 as well as using anti-IgE monoclonal antibodies, designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins), and fusion proteins.54

2.3 ∣. IL-33/ST2-mediated MC pathway

IL-33 is a member of the Toll/IL-1 cytokine family localizing in the nucleus and is expressed by different immune cells including MCs.55 IL-33 induces large synthesis of cytokines and chemokines by MCs such as IL-5 and IL-13 in group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s)56; IL-8 and IL-13 in human umbilical cord blood–derived MCs57; and T-helper subsets 1 and 2 (Th1 and Th2) in human CD34+ MCs.58 IL-33 promotes the production of cytokines in human and mouse MCs through various pathways involving binding of antigens (Ags) to IgE-bearing MCs via high-affinity FcεRI,59 anaphylatoxin complement 5a (C5a), adenosine, SCF, and nerve growth factor (NGF).60 In contrast, Martin et al proposed the dampening effect of IL-33 on pro-inflammatory signaling as evidenced in the suppression of prototypic NF-κB–triggered gene expressions including IκBα, TNF-α, and cRel.61 The interaction between IL-33 and the p50 subunit of NF-κB is constitutive with no significant enhancement in the p50 signal after stimulating human HEK293RI cells with recombinant human interleukin-1 beta (rhIL-1β), a classical activator of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Upon stimulation, the N-terminal part containing amino acids 66-109 of IL-33 interacts with the N-terminal Rel homology domain of the NF-κB p65 subunit leading to a remarkable decrease in binding affinity of p65 to its cognate DNA after IL-33/p65 nuclear translocation. However, the suppressing effect of IL-33 on the NF-κB activity is prominent at low concentration of p65 and can be overcome when p65 abundance exceeds the inhibitory capacity of IκBα.61

Both IL-33 and ST2 expression levels are significantly elevated in human asthma suggesting the crucial role of the IL-33/ST2 axis in genetic susceptibility.62 It is worth noting that the efficiency of this pathway significantly depends on the binding affinity of IL-33 to ST2.63 The IL-33/ST2 axis has been recognized as one important signaling pathway in various systems and diseases including the central nervous system,64 innate and adaptive immune responses,65 organ fibrosis,66 allergic inflammation,67 and neuroinflammation.68 IL-33/ST2 signaling promotes liver steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis due to the significant elevation of procollagen-α1 and IL-13 mRNA expression in high-fat diet-fed ST2-knockout mice compared to BALB/c mice.69 The activation of ST2 by IL-33 was proposed to be the underlying mechanism for the maturation of human MCs.70 The elevated production of IL-6 and IL-13 by mouse BMMCs via IL-33/ST2 pathway is independent of the IgE/FcεRI signals indicating potentials roles of this pathway in studying MC degranulation and survival in the absence of IgE.7 However, the IL-33/ST2 axis also improves the IgE-dependent responses to inflammation as shown in the elevation of CXCL8 concentration in IL-33–stimulated human MCs cultured with fibroblasts.60 In a study on asthma, the protective role of MC-dependent IL-33/ST2 pathway as dampening effect on airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) in MC-deficient C57BL/6KitW-sh mice was identified.71

Kawauchi et al36 evaluated the fluctuation of IL-6, IL-13, and TNFα concentrations with time and the association between ST2 and Clock expressions in WT and Clock-mutated (ClockΔ19/Δ19) BMMCs. They suggested that CLOCK protein is a novel modulator for the temporal regulation of IL-33/ST2 axis in MCs; however, the authors were not able to exclusively attribute the temporal IL-33/ST2 signaling to Clock gene. There are previously published data on the interactions between CLOCK and NF-κB that can interfere with the circadian rhythmicity of IL-33/ST2 pathway (Figure 1).72,73

The biological outcome of the IL-33/ST2 axis is profoundly controlled by the quality and abundance of ST2 expression depending on the cell types. So far, MCs are considered as the only cell type that constitutively express high levels of ST2 independent of tissue specificity; therefore, they provide critical checkpoints for IL-33 signaling in innate immune cells.74 IL-33 expression75 and MC infiltration76 have been associated with both good and poor prognosis depending on the cancer and tumor type and tissue localization. IL-33 promotes tumor progression by altering the tumor microenvironment and inducing angiogenesis whereas the anti-tumor effect of IL-33 largely correlates with the activation of immune effector cells.75 Research on the dual importance of IL-33/ST2 axis in MCs as tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing roles has quickly progressed to decipher this dichotomous effect to avoid putative false therapeutic drugs targeting the IL-33/ST2 axis in MCs.

3 ∣. EFFECTS AND ACTION MECHANISMS OF MELATONIN AND HISTAMINE IN MCS

Notwithstanding the extensive research on the roles and functions of melatonin and histamine individually, so far only one study has evaluated their interdependence under circadian rhythms. Prober et al used TALEN (transcription activator–like effector nucleases) and CRISPR/Cas9 (clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeat/CRISPR-associated protein-9 nuclease) technology to generate null mutation in arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase 2 (aanat2) zebrafish to suppress the production of melatonin in the pineal gland. They observed that the nighttime sleep activity of the aanat2−/− group was significantly decreased by half while the daytime activity was drastically increased by threefold.77 In contrast, increased sleep and decreased night activity in larvae were reported when treated with adenosine receptor agonist 5′-N-ethylcarboxamido-adenosine (NECA) and H1R antagonist pyrilamine. This indicated that histamine and melatonin act parallel in regulating sleep-wake patterns77; however, the mechanism for the interdependence of melatonin and histamine in circadian rhythms remains elusive, and at the time of this review, no such evidence has been reported in MCs. Therefore, we will discuss MC regulation with respect to melatonin and histamine separately in this section.

3.1 ∣. Melatonin: the pineal gland hormone and MCs

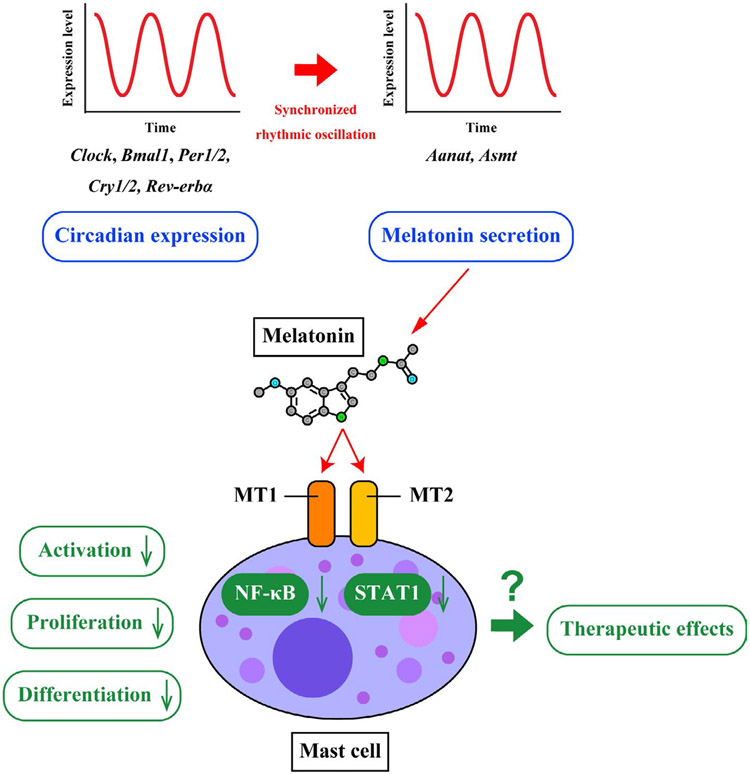

The effects of melatonin on different cells related to innate immunity have been reported.19 The circadian synthesis of melatonin is best known for its key role in mediating sleep patterns and is under regulation of the daylight-darkness cycle.78 The absence of pineal melatonin was reported to abolish the daily mRNA expression of clock genes, such as Rev-erbα, Bmal1, Per 1/2, and Cry1/2 in testes of Wistar rats.79 After pinealectomy, the daily expression profiles of melatonin-forming enzymes Aanat and acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase (Asmt), MT1, MT2, and clock genes (Clock, Bmal1, Per1/2, and Cry1/2) were significantly altered. However, these changes were partially or completely re-established by treatment with melatonin in accordance with the maturational stage of the meiotic cellular cycle and the hour of the day80 (Figure 2). Recently, new perspectives on the role of melatonin as a chronobiotic, an internal synchronizer of the circadian clock and seasonal rhythmicity, have attracted increasing interest and provided potential treatments for many sleep disorders with significant enhancement in sleep quality.20

FIGURE 2.

Therapeutic potentials targeting circadian MC-mediated melatonin. Melatonin is a hormone produced primarily in the pineal gland which helps maintain circadian rhythm and regulate reproductive hormones. Daily expressions of melatonin-forming enzymes (Aanat and Asmt) and melatonin receptors (MT1 and MT2) are in synchronized rhythmic oscillation with expression of clock genes (Clock, Bmal1, Per1/2, Cry1/2, and Rev-erbα). Melatonin is also a key mediator which recognizes potential damages and risk status in MCs via NF-κB and STAT1 pathways. Binding of melatonin to MT1 and MT2 leads to the inhibition of NF-κB activation, which in turn down-regulates MC activation, proliferation, and differentiation. Based on these findings, many compounds have been extensively investigated to impose various regulatory effects on NF-κB and melatonin in MCs and play a role as potential therapeutic drugs in MC-mediated inflammatory reactions.

The first evidence for the release of melatonin by both resting and stimulated rat basophilic leukemia (RBL)-2H3 MCs was published by Maldonado et al.81 After chemical stimuli, the melatonin secretion in RBL-2H3 culture supernatants was significantly elevated compared to unstimulated cells, supporting MC melatonin production. The activities of key enzymes N-acetyltransferase (NAT, which regulates the biosynthetic pathway of serotonin and its derivatives including melatonin) and hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase (HIOMT, which catalyzes melatonin synthesis), are significantly increased in the stimulated cells. Furthermore, the expression of melatonin membrane receptors MT1 and MT2 in both unstimulated and stimulated cells was observed indicating the modulatory effect of melatonin on MC-mediated inflammatory pathways.81 With the intravenous administration of melatonin before and after the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection, the number of MCs in the small intestine, but not liver, were reported to pronouncedly decrease.82 Pineal melatonin synthesis was decreased with the increase in pineal calcification and MC activity.83 An inversely proportional relationship between melatonin levels and the number of MCs was also reported in four separate rat groups treated with cisplatin ± melatonin/quercetin.84 Melatonin was proposed to suppress the differentiation and possibly the proliferation of MCs, indicating an inhibitory role of melatonin in the accumulation of MCs in frog testis.85 The testicular melatonin level was positively correlated with the expressions of antioxidant enzymes such as copper-zinc superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), peroxiredoxin 1, and catalase and negatively correlated with the generation of reactive oxygen species in human mast cell (HMC-1) line.86 The finding suggested melatonin might act as a protective agent against oxidative stress in testicular MCs. The protective roles of melatonin in MC degranulation in the dermis87 and in bladder88 in chronic water avoidance stress (WAS) condition were reported, and the abundancy of MCs in the WAS plus melatonin group was significantly lower than the WAS only control.

Melatonin is a key mediator which recognizes potential damages and risk status in MCs and macrophages via NF-κB89 and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT1)90 signaling pathways, respectively. During anti-inflammatory actions, the NF-κB pathway controlled by AANAT enzyme and exogenous melatonin is responsible for the synthesis of endogenous melatonin by activated MCs.89,91,92 Melatonin was confirmed as a cytoprotectant modulated by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate plus calcium ionophore A23187 (PMACI) through the NF-κB pathway.93 However, the mechanism of melatonin activation in reducing inflammatory toxicity remains unclear. In quest of elucidating this mechanism, Maldonado et al identified that in the PMACI-stimulated MCs, the significant increase of TNF-α, IL-6, and endogenous melatonin levels was recorded at 82%, 68%, and 63% higher than the unstimulated MCs. More importantly, pretreatment with exogenous melatonin before PMACI stimulation decreased the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and endogenous melatonin by 60%, 55%, and 33% in a dose-dependent manner. The authors proposed that melatonin treatment prevented the phosphorylation of IκB protein which is an inhibitor of NF-κB, stabilizing it and consequently inhibiting the activation of NF-κB.92 Diisodecyl phthalate (DIDP), a chemical widely used as an eco-friendly plasticizer, enhanced the activation of NF-κB in mouse skin MCs.94 This effect was counteracted significantly when treated with melatonin as shown in the elevated expression of redox sensor–nuclear factor erythroid–derived factor 2 (Nrf2), decreased expression of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), and up-regulation of antioxidant genes-heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate) NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO).94 Using aanat2−/− zebrafish larvae lacking melatonin, Ren et al95 suggested endogenous melatonin promotes migration of neutrophils through cytokine signaling, in particular the downregulation of inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-8. Recently, melatonin was reported to disrupt the IL-1β/NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome positive feedback loop leading to the inhibition of NLR pyrin domain–containing 3 (NLRP3), p20, and IL-1β synthesis.96 In intestinal epithelial cells, activation of NF-κB enables transcriptions of numerous genes in a rhythmic fashion.97 In microbial metabolism, NF-κB pathway modulates the regulation of melatonin in a circadian pattern. The expression of circadian clock proteins is controlled by a positive feedback inhibition involving Bmal1/Clock transcription factors.98 The regulatory mechanism between melatonin and the pathways involving NF-κB and its signaling mediator IκBα may provide new insight for diagnosis and treatment of allergic and intestinal diseases (Figure 2).

In the past three decades, there has been growing evidence supporting the production of extra-pineal melatonin in the brain, retina, skin, gastrointestinal tract, and by activated immune-competent cells. The coordination in the synthesis of melatonin by pineal gland and extra-pineal glands is fundamental in the regulation of the immune-pineal axis model.99 This model extends the bidirectional communication hypothesis on the immunological roles of pineal and extra-pineal melatonin proposed by Skwarlo-Sonta in 2003.100 The central component of the immune-pineal axis is the NF-κB family containing homo- or heterodimers of five subunits including p50, p52, p65 (RelA), RelB, and cRel. The nuclear translocation of NF-κB is promoted by the release of the inhibitory protein IκB leading to the exposure of the nuclear localization signal.99 The κB sequence was reported to be present in the promoter and the first intron of the gene that codifies AANAT, a key enzyme in melatonin synthesis, indicating NF-κB is a putative regulator of AANAT expression. Depending on the identity of the NF-κB dimers and the cellular microenvironment, the rhythmic production of melatonin can be switched from the pineal gland to immune-competent cells. In particular, the homodimer p50/p50 blocks the Aanat transcription meanwhile heterodimers containing cRel is connected to the enhancement of Aanat transcription.101 The inhibition of NF-κB activity is crucial for the reinstatement of melatonin production in the pineal gland.

3.2 ∣. MC regulation and histamine

The link between the central histaminergic system and circadian oscillation accounts for the rhythmicity regulation of various behavioral and hormonal parameters including histaminergic morphology and neuronal activity.102 The first evidence directly connecting histamine in behavior and sleep-wake control was reported using an HDC−/− mouse model. They found the HDC−/− mice, compared to the WT control group, experienced a deficit of waking at lights off and lower sleep latencies upon stimulation.103 The mRNA expression levels of clock genes in HDC−/− mice such as Per1/2 and MAL1 in 24-hour profiles appeared intact in the SCN, but were drastically disrupted in the brain areas outside the SCN, including the cortex and striatum. This suggests that the involvement of histamine in mediating circadian rhythm possibly depends on an output pathway or a feedback route.33 Researchers have proposed mechanisms by which histamine mediates the circadian clock by acting through processes including HRs, such as the H1HR/Gβγ/cAMP/PKA/CFTR pathway104 and the H1HR/CaV1.3/RyR pathway.105 Rezov et al utilized mice lacking key HRs, H1HR, and H3HR (Hrh1−/− and Hrh3−/−) to examine the contribution of these two receptors in the histamine-mediated circadian oscillation. In contrast, they found no substantial changes in the expression of Per1/2 and Bmal1 in any of the tested brain structures, suggesting the H1HR and H3HR receptors do not affect the expression patterns of the core clock genes. However, H3HR possibly contributes to the significant decrease in the amplitude of free-running activity rhythm.106 In a study of chronic rapid eye movement sleep deprivation (REM-SD), the up-regulation of HDC leading to elevated histamine release accounts for maintaining wakefulness.107

To elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the circadian function of MCs, MC mediators such as cytokines, histamine, interleukins, and TNF-α were evaluated in which histamine has emerged as a potent downstream target.8 The levels of blood histamine, thyroid histamine, and thyroid MCs follow a consistent 12-hour rhythmic manner with peaks of each variables observed at different times.13 In research conducted on MC-deficient W/Wv mice, plasma histamine levels at steady state oscillated under the influence of MC-intrinsic circadian clock. The authors indicated that organic cation transporter 3 (OCT3), which is responsible for the delivery of cytosolic histamine in MCs, is linked to the expression of Clock suggesting OCT3 is a Clock-control gene.108 Blasco et al recently studied gut MCs in stroke-induced male C57BL/6J mice and observed a significant increase of MC number and histamine receptor expression with aging. These changes lead to the elevated levels of MC-released mediators as a part of peripheral inflammatory response, such as IL-6, TNF-α, and especially histamine.109 MC-mediated histamine plays a key role in the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in inflammatory reactions.110 In LPS-treated aged F-344 rats, the release of histamine activated the MC-mediated NF-κB factor proving the major role of MC/histamine/NF-κB axis in acute inflammation.111 Recently, components of the MC-histamine autocrine loop were presented suggesting the NF-κB phosphorylation is activated because of interactions between MCs and inflammatory stimuli.112

The histamine released by MC degranulation binds to one of the four G protein–coupled HRs expressed on MCs. Pretreatment with an H1HR blocker reduced the cortisol secretion level of histamine and degranulation of brain MCs in dogs passively sensitized with IgE.113 Inhibition of H2HR in multi-drug resistant knockout mice (Mdr2−/−) decreased liver damage, in particular large ductal PSC-induced damage.114 In a study on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), the G protein–coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) was postulated to co-localized with MC markers, including histamine and substance P in human and rat colonic tissues. The levels of colonic histamine and MC degranulation were elevated in visceral hypersensitivity (VH)-induced rat; however, the effect was reversed following pretreatment with GPER antagonist G15.115 Misto et al116 reported that fasting activates the histamine release from MCs, and consequently induces liver H1HR, triggering the biosynthesis of oleoylethanolamide OEA in liver.

4 ∣. THERAPEUTIC POTENTIALS TARGETING CIRCADIAN MC-MEDIATED HISTAMINE/MELATONIN

4.1 ∣. The key factor: NF-κB

The circadian-mediated behaviors of melatonin and histamine in MCs are involved in different pathways with various factors including NF-κB which stands out as the common key player. When Sen and Baltimore first identified NF-κB,117 a nuclear factor binding near the κ light-chain gene in B cells in 1986, scientists did not realize the impact of this factor on human pathobiology.118 NF-κB comprising of dimers of Rel family members is a major signaling component in the immune system, cancer, and rapid inflammatory response.119 The roles of NF-κB in different signaling pathways modulating the SCN circadian pattern have been evaluated extensively. Marpegan et al120 reported the blocking effect of pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC), an inhibitor of NF-κB, on the light-induced phase in hamsters suggesting the connection of Rel/NF-κB family proteins to the modulation of circadian clock. Similar research in Drosophila nervous system demonstrated the circadian oscillation of cAMP response element-binding protein 2 (dCREB2)/NF-κB activity in vivo.121 There are previously published findings on the interactions between NF-κB factor and the core Clock genes such as Bmal1, Cry1/2, and Clock that can interfere with the circadian rhythmicity. Narasimamurthy et al73 further proposed that the phosphorylation of Cry proteins elevated the cAMP synthesis leading to the activation of NF-κB. RelB and Clock were reported to function as a negative and positive regulator of NF-κB-mediated pathway in circadian oscillation, respectively.122,123 A circadian pattern in the accumulation of nuclear p65, one component of NF-κB, in serum-shocked fibroblasts was observed.124 Mouse MC protease-6 (MMCP-6) and MMCP-7 induced IL-33 release in the midbrain and striatum by activation of NF-κB.125 Based on these findings, many compounds have been extensively investigated to impose various regulatory effects on NF-κB signaling pathway in MCs and play a role as potential therapeutic drugs in MC-mediated inflammatory reactions as shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Compounds targeting NF-κB in mast cells

| Name | Year | Factors decremented | Cell lines |

|---|---|---|---|

| SC-236 | 2005 | NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, VEGF, COX-2, HIF-1α | HMC147 |

| Quercetin | 2007 | NF-κB, p38 MAPK, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 | HMC-1148 |

| Gallotannins | 2007 | NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 | HMC-1149 |

| Flavonoids | 2008 | NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, intracellular [Ca2+] | MC-like RBL-2H3 cells and HMC-1150 |

| Resveratrol | 2009 | NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, COX-2, intracellular [Ca2+] | HMC-1151 |

| WECG | 2010 | NF-κB, histamine, TNF-α, IL-6 | Rat peritoneal MCs and HMC152 |

| WEEC | 2011 | NF-κB, p38 MAPK, histamine, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 | HMC-1153 |

| Chrysin | 2011 | NF-κB, histamine, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6 | MC-based in vitro and in vivo models154 |

| WESC | 2012 | NF-κB, histamine, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, intracellular [Ca2+] | HMC155 |

| Houttuynia cordata Thunb | 2013 | NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8 | HMC-1156 |

| BiRyuChe-bang | 2013 | Histamine NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8 | Rat peritoneal MCs157HMC-1157 |

| [6]-Shogaol | 2013 | Histamine NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8 | Rat peritoneal MCs158HMC-1158 |

| Caffeic acid phenethyl ester | 2014 | NF-κB, histamine, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 | HMC-1159 |

| DHMEQ | 2015 | NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-6 | RBL-2H3 MCs and BMMCs160 |

| SG-HQ2 | 2015 | NF-κB, histamine, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6 | HMC and primary peritoneal MCs161 |

| Cornuside | 2016 | NF-κB, histamine, TNF-α, IL-6 | Rat peritoneal MCs162 |

| Nodakenin | 2017 | NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 | HMC-1163 |

| Berberine | 2019 | NF-κB, p38, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-13, MCP-1 | Rat peritoneal MCs164 |

| Nothofagin | 2019 | NF-κB, histamine, TNF-α, IL-4, β-hexosaminidase | Cultured/isolated MCs165 |

4.2 ∣. Alternative factors

In IgE- and IL-33–mediated MC activation pathways, synthetic compounds able of modulating the components (casein kinase 1δ/ε and REV-ERBα) and modifiers (glucocorticoids) of clock gene expression are potential therapeutic targets.8 Evidence for the inhibitory effect of HMG-CoA reductase (statin) on the activation of MCs via IgE-mediated pathway was supported by the reduction in the synthesis of inflammatory mediators (histamine, tryptase, proteoglycans) and cytokines (IL-4, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ).126 Short-chain fatty acid such as butyrate is an effective inhibitor of both IgE-dependent and IgE-independent pathways by down-regulating the release of allergen-induced histamine.127 SR9009, a synthetic agonist of the nuclear receptor REV-ERBs, was used to inhibit MC activation independent of circadian rhythm activity.128 Human MRGPRX2 activating the release of histamine is at the center of the extensive research as a potential target to prevent allergic reactions through an IgE-dependent pathway.129,130 Suzuki et al131 employed modified systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) approach to select aptamer-X35 as an inhibitor of histamine release from MCs via MRGPRX2 pathway. Paeoniflorin was proposed as a novel inhibitor of MRGPRX2 in C48/8-induced allergic response both in vitro and in vivo.132

The development of therapeutics based on H1HR antihistamines and H2HR-targeting “blockbuster” is at the center of the search for effective treatments for allergies, liver diseases, and gastrointestinal disorders.133 In the study by Kennedy et al,134 the authors observed an elevation of H1-2HRs and MC presence in human PSC and CCA and a decrease of liver and biliary damages and fibrosis when Mdr−/− mice were treated with H1HR, H2HR, or both antagonists. In the human brain, [11C]doxepin, a potent antagonist of H1HR, was examined to visualize the neuronal histamine release as a consequence of circadian rhythms.135 Of the four HRs, the H3HR has shown a promising potential for prevention and treatment of sleep-wake disorders, due to its favorable properties and location.24 Diphenhydramine and doxylamine are the two most common over-the-counter (OTC) antihistamines offering benefits to sleep onset and sleep maintenance.136 However, more research is required to address the tolerance for sleep-promoting pharmacodynamics effect and possible adverse effects such as next-day sedating, paradoxical reactions, and increased risk of cognitive impairment in the elderly.

Recently, exposure of IgE-activated RBL-2H3 MCs to tricin, a flavone in rice bran, suppressed production of TNF-α, IL-4, leukotrienes (LT) B4, LTC4, and prostaglandin E2 by significantly decreasing the phosphorylation of the tyrosine-protein kinase (Lyn) and spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk).137 This suggested that the Lyn/Syk axis as a new potential target for prevention of IgE-mediated allergic reactions.

4.3 ∣. The emergence of complementary and herbal medicines

Herbal medicine is a fast-growing field and provides an important research direction on the prevention and treatment of MC-mediated inflammatory diseases. (−)-Asarinin (Asa), a Chinese traditional herbal medicine purified from the roots of Asiasari radix, was reported to inhibit IgE-dependent and IgE-independent allergic pathways.138 Hispidulin, another Chinese natural compound, attenuated the release of histamine and β-hexosaminidase in anti-dinitrophenyl IgE–sensitized RBL-2H3 MCs.139 The fruits of Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf (Rutaceae) (FPT)140 and the formulated ethanol extract of Artemisia asiatica Nakai (DA-9601)141 inhibited NF-κB activation by preventing the degradation of IκB, nuclear translocation of NF-κB, and NF-κB/DNA binding in activated HMCs. An unspecified aqueous extract from leaves of Eriobotrya japonica (LEJL) decreased the PMACI-induced activation of NF-κB in HMC-1 leading to the suppression of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 gene expression and secretion.142 Similar effect on the expression of IL-6 mRNA was observed when chelidonic acid in the rhizome of Chelidonium majus was tested as a potential treatment in MC-mediated inflammatory diseases.143 Oral administration of Prunus serrulata (AEBPS) leads to the suppression of MC degranulation through the downregulation of NF-κB in RBL-2H3 MCs.144 Sesamin, a lignan in sesame oil, has shown inhibitory effects on the production of histamine, TNF-α, and IL-6 dependent on the activation of NF-κB.145 Recently, the first phytomelatonin, a plant extract rich in melatonin, was successfully obtained from herbal mixed plants with the exact formulation are being patented at the time of this review.146 This finding proposed a “green” approach for producing dietary supplement rich in phytomelatonin rather than synthetic melatonin.

5 ∣. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

There is a robust association between circadian rhythms and MC activation via the IgE/FcεRI- and IL-33/ST2-mediated signaling pathways. Melatonin and histamine are two important neuromodulators involved in the regulation of circadian oscillations via NF-κB, a common key factor. The interactions between NF-κB and core clock genes Cry1/2, Clock, and Bmal1 disrupt the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-13, and TNFα and interfere with our daily rhythmic activity. Since there is currently only one study proposing the parallel acting mechanism between melatonin and histamine in regulating sleep-wake pattern, additional research is required to further elucidate the interdependence between melatonin and histamine in MC circadian rhythms. Although detailed mechanism remains elusive, current therapeutic approaches target NF-κB to restore circadian rhythms in MCs remain promising, and these studies will undoubtedly foster a better understanding on the roles of melatonin and histamine in the prevention and treatment of MC-mediated inflammatory diseases.

Funding information

Portions of these studies were supported by the Hickam Endowed Chair, Gastroenterology, Medicine, Indiana University, and PSC Partners Seeking a Cure to GA, a SRCS Award to GA, a RCS and an RCS VA Merit Award (1I01BX003031, HF) from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service and NIH grants (DK108959 and DK119421, HF) and DK115184 and DK076898 to GA and FM. Portions of the work were supported by the Strategic Research Initiative, Indiana University (HF and GA).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

This material is the result of work supported by resources at Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center. The content is the responsibility of the author(s) alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. The authors have no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Komi DEA, Rambasek T, Wohrl S. Mastocytosis: from a molecular point of view. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54(3):397–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halova I, Draberova L, Draber P. Mast cell chemotaxis - chemoattractants and signaling pathways. Front Immunol. 2012;3:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macey MR, Sturgill JL, Morales JK, et al. IL-4 and TGF-beta 1 counterbalance one another while regulating mast cell homeostasis. J Immunol. 2010;184(9):4688–4695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurish MF, Tao H, Abonia JP, et al. Intestinal mast cell progenitors require CD49d beta 7 (alpha A beta 7 integrin) for tissue-specific homing. J Exp Med. 2001;194(9):1243–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ochi H, Hirani WM, Yuan Q, Friend DS, Austen KF, Boyce JA. T helper cell type 2 cytokine-mediated comitogenic responses and CCR3 expression during differentiation of human mast cells in vitro. J Exp Med. 1999;190(2):267–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Razin E, Ihle JN, Seldin D, et al. Interleukin 3: a differentiation and growth factor for the mouse mast cell that contains chondroitin sulfate E proteoglycan. J Immunol. 1984;132(3):1479–1486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho LH, Ohno T, Oboki K, et al. IL-33 induces IL-13 production by mouse mast cells independently of IgE-Fc epsilon RI signals. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82(6):1481–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christ P, Sowa AS, Froy O, Lorentz A. The circadian clock drives mast cell functions in allergic reactions. Front Immunol. 2018;9:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komi DEA, Khomtchouk K, Maria PLS. A review of the contribution of mast cells in wound healing: involved molecular and cellular mechanisms. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2020;58(3):298–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Theoharides TC, Stewart JM. Genitourinary mast cells and survival. Transl Androl Urol. 2015;4(5):579–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyons DO, Pullen NA. Beyond IgE: alternative mast cell activation across different disease states. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komi DEA, Mortaz E, Amani S, Tiotiu A, Folkerts G, Adcock IM. The role of mast cells in IgE-independent lung diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2020;58(3):377–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catini C, Legnaioli M. Role of mast-cells in health - daily rhythmic variations in their number, exocytotic activity, histamine and serotonin content in the rat-thyroid gland. Eur J Histochem. 1992;36(4):501–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato K, Meng FY, Francis H, et al. Melatonin and circadian rhythms in liver diseases: functional roles and potential therapies. J Pineal Res. 2020;68(3):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dibner C, Schibler U, Albrecht U. The mammalian circadian timing system: organization and coordination of central and peripheral clocks. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:517–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitaterna MH, King DP, Chang AM, et al. Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene, clock, essential for circadian behavior. Science. 1994;264(5159):719–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ripperger JA, Jud C, Albrecht U. The daily rhythm of mice. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(10):1384–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakao A, Nakamura Y, Shibata S. The circadian clock functions as a potent regulator of allergic reaction. Allergy. 2015;70(5):467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calvo JR, Gonzalez-Yanes C, Maldonado MD. The role of melatonin in the cells of the innate immunity: a review. J Pineal Res. 2013;55(2):103–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zisapel N New perspectives on the role of melatonin in human sleep, circadian rhythms and their regulation. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175(16):3190–3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baiocchi L, Zhou T, Liangpunsakul S, et al. Possible application of melatonin treatment in human diseases of the biliary tract. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2019;317(5):G651–G660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aust S, Thalhammer T, Humpeler S, et al. The melatonin receptor subtype MT1 is expressed in human gallbladder epithelia. J Pineal Res. 2004;36(1):43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Renzi A, Glaser S, Demorrow S, et al. Melatonin inhibits cholangiocyte hyperplasia in cholestatic rats by interaction with MT1 but not MT2 melatonin receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301(4):G634–G643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holst SC, Valomon A, Landolt HP. Sleep pharmacogenetics: personalized sleep-wake therapy. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;56(1):577–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skene DJ, Arendt J. Circadian rhythm sleep disorders in the blind and their treatment with melatonin. Sleep Med. 2007;8(6):651–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu JB, Clough SJ, Hutchinson AJ, Adamah-Biassi EB, Popovska-Gorevski M, Dubocovich ML. MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors: a therapeutic perspective. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;56:361–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moriguchi T, Takai J. Histamine and histidine decarboxylase: Immunomodulatory functions and regulatory mechanisms. Genes Cells. 2020;25(7):443–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haas HL, Sergeeva OA, Selbach O. Histamine in the nervous system. Physiol Rev. 2008;88(3):1183–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scammell TE, Jackson AC, Franks NP, Wisden W, Dauvilliers Y. Histamine: neural circuits and new medications. Sleep. 2019;42(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valko PO, Gavrilov YV, Yamamoto M, et al. Damage to histaminergic tuberomammillary neurons and other hypothalamic neurons with traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2015;77(1):177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noain D, Buchele F, Schreglmann SR, et al. Increased sleep need and reduction of tuberomammillary histamine neurons after rodent traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(1):85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen A, Singh C, Oikonomou G, Prober DA. Genetic analysis of histamine signaling in larval Zebrafish sleep. eNeuro. 2017;4(1):1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abe H, Honma S, Ohtsu H, Honma K. Circadian rhythms in behavior and clock gene expressions in the brain of mice lacking histidine decarboxylase. Mol Brain Res. 2004;124(2):178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galli SJ, Tsai M. IgE and mast cells in allergic disease. Nat Med. 2012;18(5):693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baumann A, Gonnenwein S, Bischoff SC, et al. The circadian clock is functional in eosinophils and mast cells. Immunology. 2013;140(4):465–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawauchi T, Ishimaru K, Nakamura Y, et al. Clock-dependent temporal regulation of IL-33/ST2-mediated mast cell response. Allergol Int. 2017;66(3):472–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tahara Y, Shibata S. Entrainment of the mouse circadian clock: effects of stress, exercise, and nutrition. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;119:129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohno T, Morita H, Arae K, Matsumoto K, Nakae S. Interleukin-33 in allergy. Allergy. 2012;67(10):1203–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura Y, Nakano N, Ishimaru K, et al. Circadian regulation of allergic reactions by the mast cell clock in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):568–575.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lippert U, Artuc M, Grützkau A, et al. Human skin mast cells express H2 and H4, but not H3 receptors. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123(1):116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morse KL, Behan J, Laz TM, et al. Cloning and characterization of a novel human histamine receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296(3):1058–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hill SJ. Distribution, properties, and functional characteristics of three classes of histamine receptor. Pharmacol Rev. 1990;42(1):45–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tatemoto K, Nozaki Y, Tsuda R, et al. Immunoglobulin E-independent activation of mast cell is mediated by Mrg receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2006;349(4):1322–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Belanger KK, Ameredes BT, Boldogh I, Aguilera-Aguirre L. The potential role of 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase-driven DNA base excision repair in exercise-induced asthma. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kraft S, Kinet JP. New developments in FcepsilonRI regulation, function and inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(5):365–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Furuichi K, Rivera J, Isersky C. The receptor for immunoglobulin E on rat basophilic leukemia cells: effect of ligand binding on receptor expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82(5):1522–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baumann A, Feilhauer K, Bischoff SC, Froy O, Lorentz A. IgE-dependent activation of human mast cells and fMLP-mediated activation of human eosinophils is controlled by the circadian clock. Mol Immunol. 2015;64(1):76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feuser K, Feilhauer K, Staib L, Bischoff SC, Lorentz A. Akt cross-links IL-4 priming, stem cell factor signaling, and IgE-dependent activation in mature human mast cells. Mol Immunol. 2011;48(4):546–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cildir G, Pant H, Lopez AF, Tergaonkar V. The transcriptional program, functional heterogeneity, and clinical targeting of mast cells. J Exp Med. 2017;214(9):2491–2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kraft S, Rana S, Jouvin MH, Kinet JP. The role of the FcepsilonRI beta-chain in allergic diseases. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2004;135(1):62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakamura Y, Harama D, Shimokawa N, et al. Circadian clock gene Period2 regulates a time-of-day-dependent variation in cutaneous anaphylactic reaction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(4):1038–U1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang XJ, Reece SP, Van Scott MR, Brown JM. A circadian clock in murine bone marrow-derived mast cells modulates IgE-dependent activation in vitro. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25(1):127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakamura Y, Nakano N, Ishimaru K, et al. Inhibition of IgE-mediated allergic reactions by pharmacologically targeting the circadian clock. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4):1226–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gomez G Current strategies to inhibit high affinity FcεRI-mediated signaling for the treatment of allergic disease. Front Immunol. 2019;10:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakae S, Morita H, Ohno T, Arae K, Matsumoto K, Saito H. Role of interleukin-33 in innate-type immune cells in allergy. Allergol Int. 2013;62(1):13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cayrol C, Girard JP. IL-33: an alarmin cytokine with crucial roles in innate immunity, inflammation and allergy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;31:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iikura M, Suto H, Kajiwara N, et al. IL-33 can promote survival, adhesion and cytokine production in human mast cells. Lab Invest. 2007;87(10):971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parveen S, Saravanan DB, Saluja R, Elden BT. IL-33 mediated amplification of allergic response in human mast cells. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2019;39(4):359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oboki K, Ohno T, Kajiwara N, Saito H, Nakae S. IL-33 and IL-33 receptors in host defense and diseases. Allergol Int. 2010;59(2):143–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silver MR, Margulis A, Wood N, Goldman SJ, Kasaian M, Chaudhary D. IL-33 synergizes with IgE-dependent and IgE-independent agents to promote mast cell and basophil activation. Inflamm Res. 2010;59(3):207–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ali S, Mohs A, Thomas M, et al. The dual function cytokine IL-33 interacts with the transcription factor NF-kappa B to dampen NF-kappa B-stimulated gene transcription. J Immunol. 2011;187(4):1609–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gudbjartsson DF, Bjornsdottir US, Halapi E, et al. Sequence variants affecting eosinophil numbers associate with asthma and myocardial infarction. Nat Genet. 2009;41(3):342–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kondo Y, Yoshimoto T, Yasuda K, et al. Administration of IL-33 induces airway hyperresponsiveness and goblet cell hyperplasia in the lungs in the absence of adaptive immune system. Int Immunol. 2008;20(6):791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Du LX, Wang YQ, Hua GQ, Mi WL. IL-33/ST2 pathway as a rational therapeutic target for CNS diseases. Neuroscience. 2018;369:222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fattori V, Hohmann MSN, Rossaneis AC, et al. Targeting IL-33/ST2 signaling: regulation of immune function and analgesia. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2017;21(12):1141–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kotsiou OS, Gourgoulianis KI, Zarogiannis SG. IL-33/ST2 axis in organ fibrosis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Takatori H, Makita S, Ito T, Matsuki A, Nakajima H. Regulatory mechanisms of IL-33-ST2-mediated allergic inflammation. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cao K, Liao X, Lu J, et al. IL-33/ST2 plays a critical role in endothelial cell activation and microglia-mediated neuroinflammation modulation. J Neuroinflamm. 2018;15(1):136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pejnovic N, Jeftic I, Jovicic N, Arsenijevic N, Lukic ML. Galectin-3 and IL-33/ST2 axis roles and interplay in diet-induced steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(44):9706–9717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Allakhverdi Z, Smith DE, Comeau MR, Delespesse G. Cutting edge: The ST2 ligand IL-33 potently activates and drives maturation of human mast cells. J Immunol. 2007;179(4):2051–2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zoltowska Nilsson AM, Lei Y, Adner M, Nilsson GP. Mast cell-dependent IL-33/ST2 signaling is protective against the development of airway hyperresponsiveness in a house dust mite mouse model of asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2018;314(3):L484–L492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Curtis AM, Fagundes CT, Yang G, et al. Circadian control of innate immunity in macrophages by miR-155 targeting Bmal1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(23):7231–7236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Narasimamurthy R, Hatori M, Nayak SK, Liu F, Panda S, Verma IM. Circadian clock protein cryptochrome regulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(31):12662–12667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eissmann MF, Buchert M, Ernst M. IL33 and mast cells-the key regulators of immune responses in gastrointestinal cancers? Front Immunol. 2020;11:1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fournié J-J, Poupot M The pro-tumorigenic IL-33 involved in antitumor immunity: a yin and yang cytokine. Front Immunol. 2018;9(2506):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rigoni A, Colombo MP, Pucillo C. The role of mast cells in molding the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Microenviron. 2015;8(3):167–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gandhi AV, Mosser EA, Oikonomou G, Prober DA. Melatonin is required for the circadian regulation of sleep. Neuron. 2015;85(6):1193–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Challet E Minireview: entrainment of the Suprachiasmatic clockwork in diurnal and nocturnal mammals. Endocrinology. 2007;148(12):5648–5655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Coelho LA, Andrade-Silva J, Motta-Teixeira LC, Amaral FG, Reiter RJ, Cipolla-Neto J. The absence of pineal melatonin abolishes the daily rhythm of Tph1 (Tryptophan Hydroxylase 1), Asmt (Acetylserotonin O-Methyltransferase), and Aanat (aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase) mRNA expressions in rat testes. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56(11):7800–7809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Coelho LA, Peres R, Amaral FG, Reiter RJ, Cipolla-Neto J. Daily differential expression of melatonin-related genes and clock genes in rat cumulus-oocyte complex: changes after pinealectomy. J Pineal Res. 2015;58(4):490–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maldonado MD, Mora-Santos M, Naji L, Carrascosa-Salmoral MP, Naranjo MC, Calvo JR. Evidence of melatonin synthesis and release by mast cells. Possible modulatory role on inflammation. Pharmacol Res. 2010;62(3):282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lansink MO, Patyk V, de Groot H, Effenberger-Neidnicht K. Melatonin reduces changes to small intestinal microvasculature during systemic inflammation. J Surg Res. 2017;211:114–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maslinska D, Laure-Kamionowska M, Deregowski K, Maslinski S. Association of mast cells with calcification in the human pineal gland. Folia Neuropathol. 2010;48(4):276–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Atalik KE, Keles B, Uyar Y, Dundar MA, Oz M, Esen HH. Response to vasoconstrictor agents by detrusor smooth muscles from cisplatin-treated rats and antioxidant treatment. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2010;32(5):305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Izzo G, d'Istria M, Serino I, Minucci S. Inhibition of the increased 17 beta-estradiol-induced mast cell number by melatonin in the testis of the frog Rana esculenta, in vivo and in vitro. J Exp Biol. 2004;207(3):437–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rossi SP, Windschuettl S, Matzkin ME, et al. Melatonin in testes of infertile men: evidence for anti-proliferative and anti-oxidant effects on local macrophage and mast cell populations. Andrology. 2014;2(3):436–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cikler E, Ercan F, Cetinel S, Contuk G, Sener G. The protective effects of melatonin against water avoidance stress-induced mast cell degranulation in dermis. Acta Histochem. 2005;106(6):467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cetinel S, Ercan F, Cikler E, Contuk G, Sener G. Protective effect of melatonin on water avoidance stress induced degeneration of the bladder. J Urol. 2005;173(1):267–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pires-Lapa MA, Tamura EK, Salustiano EMA, Markus RP. Melatonin synthesis in human colostrum mononuclear cells enhances dectin-1-mediated phagocytosis by mononuclear cells. J Pineal Res. 2013;55(3):240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pfitzner E, Kliem S, Baus D, Litterst CM. The role of STATs in inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10(23):2839–2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Villela D, Lima LD, Peres R, et al. Norepinephrine activates NF-kappa B transcription factor in cultured rat pineal gland. Life Sci. 2014;94(2):122–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maldonado MD, Garcia-Moreno H, Gonzalez-Yanes C, Calvo JR. Possible involvement of the inhibition of NF-B factor in anti-inflammatory actions that melatonin exerts on mast cells. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117(8):1926–1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Maldonado MD, Garcia-Moreno H, Calvo JR. Melatonin protects mast cells against cytotoxicity mediated by chemical stimuli PMACI: possible clinical use. J Neuroimmunol. 2013;262(1–2):62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shen S, Li J, You H, et al. Oral exposure to diisodecyl phthalate aggravates allergic dermatitis by oxidative stress and enhancement of thymic stromal lymphopoietin. Food Chem Toxicol. 2017;99:60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ren DL, Ji C, Wang XB, Wang H, Hu B. Endogenous melatonin promotes rhythmic recruitment of neutrophils toward an injury in zebrafish. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen F, Jiang G, Liu H, et al. Melatonin alleviates intervertebral disc degeneration by disrupting the IL-1β/NF-κB-NLRP3 inflammasome positive feedback loop. Bone Res. 2020;8:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mukherji A, Kobiita A, Ye T, Chambon P. Homeostasis in intestinal epithelium is orchestrated by the circadian clock and microbiota cues transduced by TLRs. Cell. 2013;153(4):812–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ma N, Zhang J, Reiter RJ, Ma X. Melatonin mediates mucosal immune cells, microbial metabolism, and rhythm crosstalk: a therapeutic target to reduce intestinal inflammation. Med Res Rev. 2020;40(2):606–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Markus RP, Cecon E, Pires-Lapa MA. Immune-pineal axis: nuclear factor κB (NF-kB) mediates the shift in the melatonin source from pinealocytes to immune competent cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(6):10979–10997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Skwarlo-Sonta K, Majewski P, Markowska M, Oblap R, Olszanska B. Bidirectional communication between the pineal gland and the immune system. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;81(4):342–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Markus RP, Fernandes PA, Kinker GS, da Silveira C-M, MarÇola M. Immune-pineal axis - acute inflammatory responses coordinate melatonin synthesis by pinealocytes and phagocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175(16):3239–3250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tuomisto L, Lozeva V, Valjakka A, Lecklin A. Modifying effects of histamine on circadian rhythms and neuronal excitability. Behav Brain Res. 2001;124(2):129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Parmentier R, Ohtsu H, Djebbara-Hannas Z, Valatx JL, Watanabe T, Lin JS. Anatomical, physiological, and pharmacological characteristics of histidine decarboxylase knock-out mice: evidence for the role of brain histamine in behavioral and sleep-wake control. J Neurosci. 2002;22(17):7695–7711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kim YS, Kim YB, Kim WB, et al. Histamine 1 receptor-Gβγ-cAMP/PKA-CFTR pathway mediates the histamine-induced resetting of the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Mol Brain. 2016;9(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kim YS, Kim YB, Kim WB, et al. Histamine resets the circadian clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus through the H1R-CaV 1.3-RyR pathway in the mouse. Eur J Neurosci. 2015;42(7):2467–2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rozov SV, Porkka-Heiskanen T, Panula P. On the role of histamine receptors in the regulation of circadian rhythms. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0144694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hoffman GE, Koban M. Hypothalamic L-histidine decarboxylase is up-regulated during chronic REM sleep deprivation of rats. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nakamura Y, Ishimaru K, Shibata S, Nakao A. Regulation of plasma histamine levels by the mast cell clock and its modulation by stress. Sci Rep. 2017;7:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Blasco MP, Chauhan A, Honarpisheh P, et al. Age-dependent involvement of gut mast cells and histamine in post-stroke inflammation. J Neuroinflamm. 2020;17(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Holden NS, Gong W, King EM, Kaur M, Giembycz MA, Newton R. Potentiation of NF-kappa B-dependent transcription and inflammatory mediator release by histamine in human airway epithelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152(6):891–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nizamutdinova IT, Dusio GF, Gasheva OY, et al. Mast cells and histamine are triggering the NF-κB-mediated reactions of adult and aged perilymphatic mesenteric tissues to acute inflammation. Aging. 2016;8(11):3065–3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pal S, Gasheva OY, Zawieja DC, Meininger CJ, Gashev AA. Histamine-mediated autocrine signaling in mesenteric perilymphatic mast cells. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2020;318(3):R590–R604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Matsumoto I, Inoue Y, Shimada T, Aikawa T. Brain mast cells act as an immune gate to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in dogs. J Exp Med. 2001;194(1):71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kennedy L, Meadows V, Kyritsi K, et al. Amelioration of large bile duct damage by histamine-2 receptor vivo-morpholino treatment. Am J Pathol. 2020;190(5):1018–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Xu SX, Wang XY, Zhao J, Yang SZ, Dong L, Qin B. GPER-mediated, oestrogen-dependent visceral hypersensitivity in stressed rats is associated with mast cell tryptase and histamine expression. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2020;34:433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Misto A, Provensi G, Vozella V, Passani MB, Piomelli D. Mast cell-derived histamine regulates liver ketogenesis via oleoylethanolamide signaling. Cell Metab. 2019;29(1):91–102.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sen R, Baltimore D. Multiple nuclear factors interact with the immunoglobulin enhancer sequences. Cell. 1986;46(5):705–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhang Q, Lenardo MJ, Baltimore D. 30 years of NF-κB: a blossoming of relevance to human pathobiology. Cell. 2017;168(1–2):37–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ghosh S, Hayden MS. Celebrating 25 years of NF-κB research. Immunol Rev. 2012;246(1):5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Marpegan L, Bekinschtein TA, Freudenthal R, et al. Participation of transcription factors from the Rel/NF-kappa B family in the circadian system in hamsters. Neurosci Lett. 2004;358(1):9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tanenhaus AK, Zhang J, Yin JC. In vivo circadian oscillation of dCREB2 and NF-κB activity in the Drosophila nervous system. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e45130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Spengler ML, Kuropatwinski KK, Comas M, et al. Core circadian protein CLOCK is a positive regulator of NF-κB-mediated transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(37):E2457–E2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bellet MM, Zocchi L, Sassone-Corsi P. The RelB subunit of NFκB acts as a negative regulator of circadian gene expression. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(17):3304–3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.O'Keeffe SM, Beynon AL, Davies JS, Moynagh PN, Coogan AN. NF-κB signalling is involved in immune-modulation, but not basal functioning, of the mouse suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Eur J Neurosci. 2017;45(8):1111–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kempuraj D, Thangavel R, Selvakumar GP, et al. Mast cell proteases activate astrocytes and glia-neurons and release interleukin-33 by activating p38 and ERK1/2 MAPKs and NF-κB. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56(3):1681–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kouhpeikar H, Delbari Z, Sathyapalan T, Simental-Mendia LE, Jamialahmadi T, Sahebkar A. The effect of statins through mast cells in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis: a review. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2020;22(5):8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Folkerts J, Redegeld F, Folkerts G, et al. Butyrate inhibits human mast cell activation via epigenetic regulation of Fc epsilon RI-mediated signaling. Allergy. 2020;75:1966–1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ishimaru K, Nakajima S, Yu GN, Nakamura Y, Nakao A. The putatively specific synthetic REV-ERB agonist SR9009 inhibits IgE- and IL-33-mediated mast cell activation independently of the circadian clock. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(24):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Fujisawa D, Kashiwakura J, Kita H, et al. Expression of mas-related gene X2 on mast cells is upregulated in the skin of patients with severe chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(3):622–633.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lin YY, Wang J, Hou YJ, et al. Isosalvianolic acid C-induced pseudo-allergic reactions via the mast cell specific receptor MRGPRX2. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;71:22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Suzuki Y, Liu S, Ogasawara T, et al. A novel MRGPRX2-targeting antagonistic DNA aptamer inhibits histamine release and prevents mast cell-mediated anaphylaxis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;878:9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wang JL, Zhang YJ, Wang J, et al. Paeoniflorin inhibits MRGPRX2-mediated pseudo-allergic reaction via calcium signaling pathway. Phytother Res. 2020;34(2):401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Tiligada E, Ennis M. Histamine pharmacology: from Sir Henry Dale to the 21st century. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177(3):469–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kennedy L, Hargrove L, Demieville J, et al. Blocking H1/H2 histamine receptors inhibits damage/fibrosis in Mdr2(−/−) mice and human cholangiocarcinoma tumorigenesis. Hepatology. 2018;68(3):1042–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Shibuya K, Funaki Y, Hiraoka K, et al. [(11)C]Doxepin binding to histamine H1 receptors in living human brain: reproducibility during attentive waking and circadian rhythm. Front Syst Neurosci. 2012;6:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Neubauer DN, Pandi-Perumal SR, Spence DW, Buttoo K, Monti JM. Pharmacotherapy of Insomnia. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2018;10:1179573518770672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Lee JY, Park SH, Jhee KH, Yang SA. Tricin isolated from enzyme-treated Zizania latifolia extract inhibits IgE-mediated allergic reactions in RBL-2H3 cells by targeting the Lyn/Syk pathway. Molecules. 2020;25(9):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hou YJ, Hu T, Wei D, et al. (−)-Asarinin inhibits mast cells activation as a Src family kinase inhibitor. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2020;121:9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Kim DE, Min KJ, Kim MJ, Kim SH, Kwon TK. Hispidulin inhibits mast cell-mediated allergic inflammation through down-regulation of histamine release and inflammatory cytokines. Molecules. 2019;24(11):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Shin TY, Oh JM, Choi BJ, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of Poncirus trifoliata fruit through inhibition of NF-kappaB activation in mast cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2006;20(7):1071–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Lee S, Park HH, Son HY, et al. DA-9601 inhibits activation of the human mast cell line HMC-1 through inhibition of NF-kappaB. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2007;23(2):105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Kim SH, Shin TY. Anti-inflammatory effect of leaves of Eriobotrya japonica correlating with attenuation of p38 MAPK, ERK, and NF-kappaB activation in mast cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2009;23(7):1215–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Shin HJ, Kim HL, Kim SJ, Chung WS, Kim SS, Um JY. Inhibitory effects of chelidonic acid on IL-6 production by blocking NF-κB and caspase-1 in HMC-1 cells. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2011;33(4):614–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kim MJ, Choi YA, Lee S, et al. Prunus serrulata var. spontanea inhibits mast cell activation and mast cell-mediated anaphylaxis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;250:8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Li LC, Piao HM, Zheng MY, Lin ZH, Li G, Yan GH. Sesamin attenuates mast cell-mediated allergic responses by suppressing the activation of p38 and nuclear factor-κB. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13(1):536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Pérez-Llamas F, Hernández-Ruiz J, Cuesta A, Zamora S, Arnao MB. Development of a phytomelatonin-rich extract from cultured plants with excellent biochemical and functional properties as an alternative to synthetic melatonin. Antioxidants. 2020;9(2):1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kim SJ, Jeong HJ, Choi IY, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor SC-236 [4-[5-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-1-pyrazol-1-l] benzenesulfonamide] suppresses nuclear factor-kappaB activation and phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, extracellular signal-regulated kinase, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase in human mast cell line cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314(1):27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Min YD, Choi CH, Bark H, et al. Quercetin inhibits expression of inflammatory cytokines through attenuation of NF-kappaB and p38 MAPK in HMC-1 human mast cell line. Inflamm Res. 2007;56(5):210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Lee SH, Park HH, Kim JE, et al. Allose gallates suppress expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines through attenuation of NF-kappaB in human mast cells. Planta Med. 2007;73(8):769–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Park HH, Lee S, Son HY, et al. Flavonoids inhibit histamine release and expression of proinflammatory cytokines in mast cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2008;31(10):1303–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Kang OH, Jang HJ, Chae HS, et al. Anti-inflammatory mechanisms of resveratrol in activated HMC-1 cells: pivotal roles of NF-kappaB and MAPK. Pharmacol Res. 2009;59(5):330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Park SB, Kim SH, Suk K, et al. Clinopodium gracile inhibits mast cell-mediated allergic inflammation: involvement of calcium and nuclear factor-kappaB. Exp Biol Med. 2010;235(5):606–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Kim HH, Yoo JS, Lee HS, Kwon TK, Shin TY, Kim SH. Elsholtzia ciliata inhibits mast cell-mediated allergic inflammation: role of calcium, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-{kappa}B. Exp Biol Med. 2011;236(9):1070–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Bae Y, Lee S, Kim SH. Chrysin suppresses mast cell-mediated allergic inflammation: involvement of calcium, caspase-1 and nuclear factor-κB. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;254(1):56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]