To the Editor: Invasive pulmonary mucormycosis (IPM) is a rare but life-threatening opportunistic fungal disease with a high mortality rate of 40% to 80%.[1] Although IPM accounts for approximately 9.2% of all mucormycosis cases, it has the highest mortality rate (66.6%). A definitive diagnosis of IPM depends on the histopathological findings, regardless of culture results of the respiratory tract specimens or lung tissues.

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) is more common than IPM. In previous studies, IPA was found to be the most common invasive pulmonary fungal infection in China. It accounted for 37.9% of all invasive pulmonary fungal infection cases and had a mortality rate of 35% to 80%.[2–4] Delayed diagnosis and improper treatment are usually responsible for the high mortality rate.[3] Monitoring the level of galactomannan (GM), a specific cellular wall constituent of Aspergillus, can contribute to the early treatment of IPA. Identification of the hyphae from histopathological tissues with or without a culture of respiratory tract specimens or lung tissues can help distinguish IPA from IPM. Here, we report on the successful treatment of a case of IPA and IPM coinfection because of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.

A 54-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with complaints of nausea and vomiting 8 days ago. The patient had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus 10 years ago, and her body mass index was 22.5 kg/m2. On admission, her vitals were as follows: body temperature, 36.3°C; heart rate, 104 beats/min; respiratory rate, 24 breaths/min; and blood pressure, 83/63 mmHg. A physical examination revealed coarse breathing sounds, but there was no rale in either lung. The arterial blood gas analysis revealed the following: pH, 6.94; partial pressure of oxygen, 136.1 mmHg; and glucose, 29.4 mmol/L. Routine blood tests yielded the following results: white blood cell count, 17.06 × 109/L; neutrophil count, 13.40 × 109/L; and C-reactive protein level, 35.59 mg/L. Renal function tests showed that the serum creatinine level was 120.92 μmol/L (normal range: 41–81 μmol/L) and urea nitrogen level was 18.0 mmol/L (normal range: 3.1–8.8 mmol/L). Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed multiple nodules in the right lung. Although a combination of levofloxacin and cefminox was administered for 2 days, the patient developed high fever (body temperature, 38.3°C). On day five, chest CT revealed air crescent signs in two nodules in the right upper lobe of the lung, progressive bilateral pulmonary infiltration along the branch bundles, and bilateral pleural effusion [Figure 1A]. Hence, the antibiotic treatment was upgraded to biapenem combined with levofloxacin.

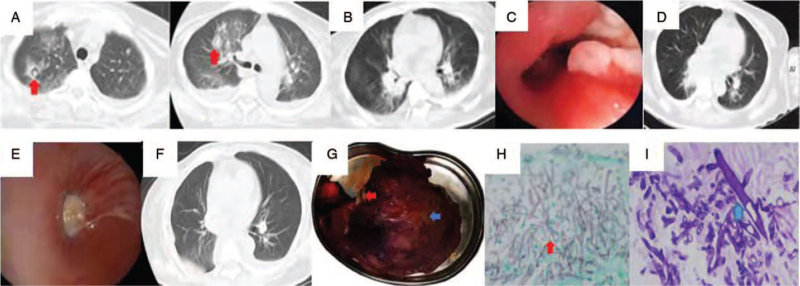

Figure 1.

(A) Chest CT showing air crescent signs in two nodules in the right upper lobe. (B) Chest CT on day nine after admission showing Inflammatory exudation and obstruction In the middle trunk of the right lung. (C) Bronchoscopy showing thickening, hyperemia, and edema of the middle trunk mucosa of the right lung, stenosis of the lumen, and the local mucosa attached to a white tail membrane on day 23 after admission. (D, E) Repeated chest CT and bronchoscopy on days 52 and 57, respectively, showed progression of the lesions. (F, G) The postoperative chest imaging finding and a gross specimen of the right middle and lower lobe of the lung showed there were fungal clusters (red arrow) and several small abscesses (blue arrow) seen in the lung. (H, I) Aspergillus: fine, acute angle, branching septate hyphae (red arrow, GMS staining, original magnification ×200); Mucor Aseptate hyphae with right-angled branching (blue arrow, PAS staining, original magnification ×200). CT: Computed tomography; GMS: Gormori methenamine silver; PAS: Periodic acid-Schiff.

After 5 days of therapy, her conditions did not improve. Therefore, considering the cerebral hemorrhage indicated on craniocerebral CT acquired after admission, aspiration pneumonia was suspected, and Gram-positive cocci infections could not be excluded. Vancomycin alone was administered for 4 days, and the right upper lobe lesion has been absorbed. But the patient had intermittent fever and cough. The serum creatinine and urea nitrogen levels were within the normal range (41.65 μmol/L and 3.55 mmol/L, respectively). On day nine, chest CT showed that her pneumonia had progressed rapidly, with atelectasis in the right lower lung [Figure 1B]. The serum GM level was 0.92 μg/L (cut-off value: 0.65 μg/L). Bedside bronchoscopy on day 23 showed stenosis of the lumen in the middle trunk of the right lung, with thickened, edematous mucus, and white moss [Figure 1C]. When the front end of the bronchoscope touched the lesion, it bled easily. A clinical diagnosis of IPA was made based on a series of auxiliary examinations in the absence of any evidence of Aspergillus infection. Hence, 0.4 g of voriconazole was administered intravenously every 12 h on day one, followed by 0.2 g every 12 h for 7 days, based on the patient weight (65 kg) and drug indications. Her body temperature gradually deceased after 4 days but tended to rise again. The second bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and serum GM tests revealed higher levels as compared to the first. On day 29, a repeat bronchoscopy showed an almost complete obstruction in the middle trunk of the right lung. The pathological results showed a small amount of Mucor hyphae. BALF and serum GM tests revealed negative results (aspergillus GM antigen 0.41 μg/L and 0.64 μg/L, respectively). On day 30, intravenous amphotericin B (AmB) was administered. Repeated BALF tests did not reveal any pathogen. The initial dose of AmB was 5 mg/day, which was then increased to 25 mg/day for 2 weeks. The patient renal function deteriorated gradually; hence, AmB was switched to liposome AmB (dose increment from 20 mg/day to 120 mg/day) for 11 days. After administering AmB for 5 days, the patient clinical symptoms and related auxiliary examination findings showed further deterioration. Therefore, 10 mg of posaconazole was administered orally twice a day to manage the disease aggravation. Subsequently, repeated chest CT [Figure 1D] and bronchoscopy [Figure 1E] on days 52 and 57, respectively, showed progression of the lesions. Considering that the resection of the patient's entire right lung would affect lung function and lead to a decline in quality of life, lobectomy of the middle and lower lobes of the right lung was performed instead [Figure 1F, G]. Histopathology revealed abundant Aspergillus and Mucor hyphae [Figure 1H, I].

Approximately 2 weeks after the lobectomy, the patient was discharged with a normal body temperature (36.7°C) on day 78. Two weeks later, a repeat bronchoscopy revealed that the lesion had disappeared, and the incision had healed well without any abnormalities. After discharge, the patient continued to take posaconazole orally and visited the respiratory clinic regularly for reexamination.

To our knowledge, this is the eleventh report of a case of IPA and IPM coinfection. Previously, ten cases, including three cases of hematological diseases, two of trauma, two of diabetes, one of decompensated liver cirrhosis, one of drowning, and one of long-term treatment with cortisol for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, have been reported. Including our case, patients with a history of uncontrolled diabetes accounted for more than one-fourth of the cases of IPM and IPA coinfection. Diabetes, especially diabetic ketoacidosis, is an important risk factor for fungal coinfection. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by neutrophils play a key role in Aspergillus infection resistance. Given that diabetes affects the production of ROS by neutrophils, patients with diabetes are at an increased risk of IPA infection.[5]

The patient's initial examination revealed impaired renal function. We consider that the main reason is the acute stress caused by acute cerebral hemorrhage and fever. Typical characteristics of chest CT, such as the air crescent sign for IPA and reversed halo sign for IPM, are useful for the diagnosis of invasive pulmonary fungal infection in immunocompromised patients. The air crescent sign usually occurs 1 to 2 weeks after disease onset. In our case, the air crescent sign appeared on the 13th day of disease onset. The positive serum GM test results led to the suspicion of Aspergillus infection, but no anti-aspergillosis treatment was started. Remarkably, the infiltration on the chest CT improved after antimicrobial treatment. The air crescent sign can also be found in pulmonary gangrene cases secondary to infections with bacteria, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae and Streptococcus pneumoniae, pulmonary echinococcosis, lung cancer, and intracavitary thrombosis. We suspected mixed IPM complicated by a bacterial infection in the early stage as short-term improvement was noted based on the imaging findings.

Bronchoscopy plays an indispensable role in diagnosing pulmonary fungal disease, as do the etiology and GM test results. The level of GM released, which reflects the degree of infection, is proportional to the Aspergillus load. This can be measured by analyzing the serum and BALF. The

GM levels in the BALF and serum returned to normal after administration of voriconazole, suggesting that continuous monitoring of the GM levels can help assess the therapeutic effects.[6] In patients with neutropenia or allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant, the sensitivity and specificity of serum detection of GM were 70% to 82% and 81% to 92%, respectively. In contrast, the sensitivity and specificity of BALF detection were 73% to 100% and 68% to 92%, respectively.[7] Notably, the GM test does not play a role in the diagnosis of IPM.[8] Among the ten patients with IPA and IPM coinfection caused by coinfections of different etiologies, the diagnosis of IPA in four patients was based on positive BALF GM test results. This suggests that physicians should focus on the increased levels of GM in BALF for the early diagnosis and treatment of IPA.

The global guidelines for mucormycosis strongly recommend aggressive surgery and high-dose liposomal AmB treatment.[1] Our patient showed clinical failure after undergoing antifungal therapy for 26 days, and this clinical failure was associated with inadequate treatment with AmB or liposome AmB because of poor renal function that recovered after lobectomy. This was similar to a case reported by Bergantim et al.[9] Histopathological diagnosis is the gold standard for the diagnosis of IPA and IPM. In addition to systematic antifungal therapy, treatment using intramucosal injection of antifungal drugs through bronchoscopy should be explored further.

The diagnosis and treatment of IPA and IPM coinfection are difficult. Clinicians should suspect this mixed infection when no clinical improvement occurs with targeted treatment of a specific fungal infection, especially in susceptible hosts. Dynamic monitoring of GM levels and bronchoscopy are valuable in the early diagnosis of IPA and IPM coinfection.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that a signed patient consent form was obtained. In the consent form, the patient has given consent for her clinical information to be published in the journal. The patient understands that her name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal her identify, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Teng P, Han X, Zhang S, Wei D, Wang Y, Liu D, Liu X. Mixed invasive pulmonary Mucor and Aspergillus infection: a case report and literature review. Chin Med J 2022;135:854–856. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001839

References

- 1.Cornely OA, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Arenz D, Chen SCA, Dannaoui E, Hochhegger B, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19:e405–e421. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30312-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costa CP, Silva DG, Rudnitskaya A, Almeida A, Rocha SM. Shedding light on Aspergillus niger volatile exometabolome. Sci Rep 2016; 6:27441.doi: 10.1038/srep27441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmiedel Y, Zimmerli S. Common invasive fungal diseases: an overview of invasive candidiasis, aspergillosis, cryptococcosis, and Pneumocystis pneumonia. Swiss Med Wkly 2016; 146:w14281.doi: 10.4414/smw.2016.14281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cadena J. Thompson GR 3rd, Patterson TF. Invasive aspergillosis: current strategies for diagnosis and management. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2016; 30:125–142. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu X, Xia C, Huang Y. Different roles of intracellular and extracellular reactive oxygen species of neutrophils in type 2 diabetic mice with invasive aspergillosis. Immunobiology 2020; 225:151996.doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2020.151996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meersseman W, Lagrou K, Maertens J, Wilmer A, Hermans G, Vanderschueren S, et al. Galactomannan in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid: a tool for diagnosing aspergillosis in intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 177:27–34. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200704-606OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miceli MH, Maertens J. Role of non-culture-based tests, with an emphasis on galactomannan testing for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 36:650–661. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1562892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin CY, Wang IT, Chang CC, Lee WC, Liu WL, Huang YC, et al. Comparison of clinical manifestation, diagnosis, and outcomes of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and pulmonary mucormycosis. Microorganisms 2019; 7:531.doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7110531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergantim R, Rios E, Trigo F, Guimarães JE. Invasive coinfection with Aspergillus and Mucor in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Drug Investig 2013; 33: (Suppl 1): S51–55. doi: 10.1007/s40261-012-0022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]