Abstract

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment landscape is shifting given the advent of direct-acting antivirals and a global call to action by the World Health Organization. Eliminating HCV is now an issue of healthcare delivery. Treatment is limited by the complexity of the HCV care continuum, expensive therapy, and competing health burdens experienced by an underserved HCV population. The objective of this literature review was to assess strategies to improve retention in HCV care, with particular focus on those implemented in the United States. We identified barriers in HCV care retention and propose solutions to increase HCV treatment delivery. The following recommendations are herein described: improving cohesion of health services through localized care and integegrated case managmeent, expanding supply of non-specialist HCV treatment providers, leveraging patient navigators and care coordiantors, improving adherence through direct observred therapy, and reducing cost barriers through value-based payment and pharmaceutical subscription models.

Keywords: hepatitis C, retention, treatment, care continuum, healthcare delivery

1. Introduction

Globally, 71 million people have chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, of whom 2.4 million live in the United States (US).1,2 Untreated HCV infection results in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and increased mortality.3 HCV also causes significant extra-hepatic morbidity including vascular, cardiometabolic, and renal disease.4

The advent of direct acting antivirals (DAAs) in 2011 revolutionized HCV therapy. Boasting HCV cure rates exceeding 95%, DAAs have replaced interferon-based as standard therapy for HCV.5 In addition to their superior efficacy, DAAs have proven to be safe, simple to administer as oral tablets, of short duration (8 to 12 weeks), and well-tolerated compared to the former standard of interferon-based regimins.6

With the paradigm shift in treatment, there has been renewed action to reduce the global burden of HCV. In 2016, the World Health Assembly adopted the Global Health Sector Strategy on viral hepatitis to eliminate the disease by 2030.7 To accomplish this, the World Health Organization (WHO) aims to close the diagnostic and treatment gap by diagnosing 90% of people with HCV and treating 80% of people diagnosed.1 In 2018, the WHO began recommending treating of all persons with chronic HCV infection over the age of 12 with pan-genotypic DAAs, regardless of disease stage.1

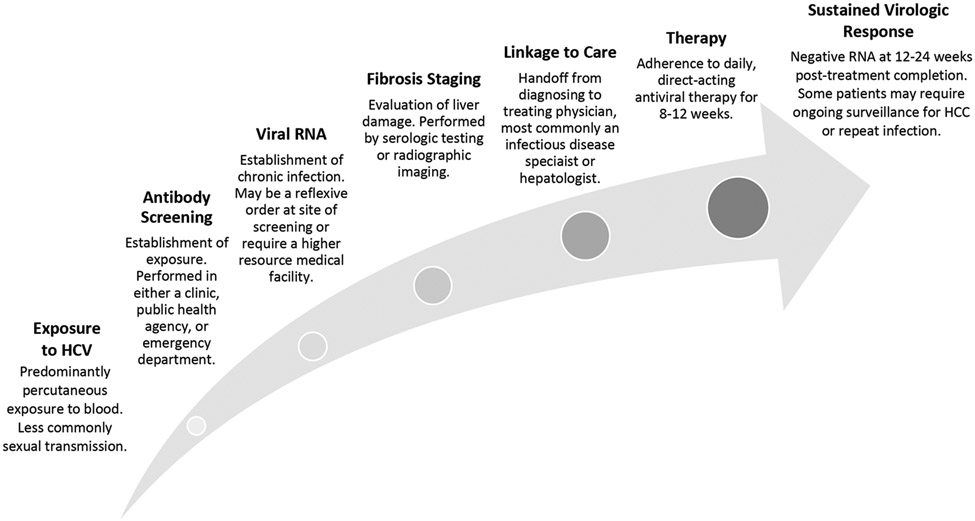

With the advent of DAAs, and a renewed global call to action, eliminating HCV is now limited by healthcare delivery. The HCV continuum of care is a population health model that outlines successive stages of HCV care delivery from diagnosis to cure (Figure 1).8 The continuum of care includes HCV antibody screening, HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) confirmation of chronic infection, linkage to an HCV specialist, hepatic fibrosis staging, HCV therapy, and achieving functional cure, or sustained virologic response at 12 weeks (SVR12).8-10 Patients are considered fully treated once achieving SVR12; failure to successfully complete one step in the continuum results in untreated HCV. This model demonstrates that curing HCV is predicated on patients’ access to and completion of multiple stages of specialty healthcare.

Figure 1. Hepatitis C care continuum.

A theoretical framework of hepatitis C care delivery.

Assessing retention at each stage in the care continuum demonstrates extensive gaps in HCV healthcare delivery. In the US in 2016, 76.5% of HCV seropositive patients received RNA confirmation, while among those chronically infected, 17.4% saw an HCV specialist.11 Among the British Columbia Hepatitis Testers Cohort in 2018, post-DAA introduction, 83% of HCV seropositive individuals received confirmatory RNA testing, while of those chronically infected, 39% initiated therapy and 35% achieved SVR.12 This treatment gap is more pronounced globally. Of the 71 million persons worldwide with HCV infection in 2015, 14 million (20%) were diagnosed. Of those diagnosed, 5.4 million (39%) had started HCV therapy, including both interferon-based and DAA regimens, while an estimated 843,000 (6%) reached SVR.13

Despite the high efficacy of DAAs, failed retention in the care continuum reduces the effectiveness of HCV therapy by approximately 75%.14 Increasing retention in the HCV care continuum is imperative to close the profound HCV treatment gap. The objective of this literature review was to assess US strategies to improve HCV healthcare delivery and retention in HCV care (Table 1).

Table 1.

Closing the treatment gap: present problem and proposed solution.

| Present Problem | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|

|

Complexity of Care Continuum HCV care continuum involves multiple distinct medical specialties and providers. The numerous steps and protracted time of the care continuum predisposes to high loss to follow-up. |

Localized Care Spatially co-localize screening, evaluation, and treatment steps in the HCV care continuum alongside primary care services. Ancillary Personnel: Care Coordinators and Patient Navigators Care coordinators contact all HCV antibody positive patients, schedule follow-up care for those chronically infected, and navigate patients through the continuum of HCV services. |

|

Underserved Population HCV+ patients are often members of underserved populations, including people who use drugs, people experiencing homelessness, and Baby Boomers with multiple comorbidities. |

Integrated Case Management Use of multi-disciplinary teams managing a patient’s co-morbidities and HCV improves rates of initiating antiviral therapy and achieving sustained virologic response. |

|

Low Supply to HCV Treatment Providers

In high-resource areas In low-resource areas |

Advanced Practice Providers Reserve physician appointments for the provision of HCV therapy, leaving advanced practice providers to conduct the initial exam and pre-treatment evaluation (RNA quantification, liver fibrosis staging, and genotype testing). Telementoring for Primary Care Physicians Connect primary care physicians with HCV specialists. Project Expanding Capacity for Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) has been demonstrated to promote equal HCV care outcomes by ECHO-telementored primary care physicians as university-based HCV specialists. |

|

High Cost of DAAs Direct acting antivirals (DAAs) are costly and many patients with HCV are un-/under-insured. |

Value Based Payment Tie reimbursement to patient health outcomes. Subscription Model By offering a lump sum payment to pharmaceutical companies, revenues are decoupled from the price per pill. Suppliers benefit from a boost in public relations in addressing public health, while also decreasing economic risk through a steady and dependable cash flow. |

2. Methods

A scoping review was performed. Three researchers performed an extensive search of PubMed Central® and Embase® electronic databases, restricting to publications written in English. After reading abstracts and titles, two independent researchers identied articles pertinent to the study objective. These articles underwent full-text review and data extraction. All discrepancies were adjudicated by a third researcher.

3. Cohesion Among Health Services

The HCV care continuum spans multiple specialties and healthcare providers. Screening may involve a general practitioner, public health agency, or emergency department (ED). A radiology referral is often needed for fibrosis staging by transient elastography and screening for liver masses concerning for HCC. Treatment and further management most commonly occur via a specialist provider, often a hepatologist or an infectious disease physician. Navigating this complex array of providers is difficult for those at highest risk for HCV, particularly people who inject drugs (PWID) and people experiencing homelessness (PEH). Increased cohesion among health services, through physical proximity or integrated care, has the potential to improve care retention.

2.1. Localized Care

Barriers to retention are reduced by spatially co-localizing screening, evaluation, and treatment steps in the HCV care continuum alongside primary care.15 This forms a centralized system of care services, tailored to the needs of vulnerable populations at highest risk for HCV. This includes PWID, for whom co-localized care in substance abuse treatment centers, correctional facilities, and needle exchange programs has improved the delivery of HCV services for this population.16

Removing travel between different HCV healthcare services improves linkage to care. In a study of a five-member network of Federal Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), patients screened at FQHCs providing both HCV screening and treatment were nearly three times more likely to undergo a medical evaluation and twice as likely to receive fibrosis staging, as compared to patients screened HCV seropositive (HCV+) at a FQHC offering only HCV screening.17

2.2. Integrated Case Management

Given that HCV is prevalent among PEH, PWID, and the baby boomer cohort (persons born from 1945 to 1965), HCV+ patients are often members of underserved and/or elderly populations with multiple comorbidities.18 Approximately a quarter of treatment non-initiation by the provider could be attributed to the psychiatric illness, alcohol use, and drug use.19 As such, integrated case management, beyond HCV therapy, is essential.

Integrated management predominantly consists of psychiatric and substance abuse services, targeting known risk factors of failed treatment initiation.20 The use of a multi-disciplinary team shows promise at improving linkage to care, initiating antiviral therapy, and achieving SVR.21-23 One study examined a Queensland, Australia community-based HCV treatment center serving PWID through integrated harm reduction services (needle exchange programs), drug and alcohol counseling, and medical care.24 Of those participants who initiated DAAs, 96% completed treatment, 92% adhered to follow-up, and 80% achieved SVR.24 Structural and behavioral interventions, including integrated case management, appear to be successful in addressing barriers to treatment adherence.

4. Decentralization of Care to Non-Specialist Healthcare Providers

A barrier to HCV care is decreased access to providers who are trained to treat HCV. The expanded 2013 and 2020 United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) screening guidelines has increased the pool of diagnosed HCV+ patients in the US, a number that cannot be sustained by current HCV specialists for treatment and management. Management of HCV therapy was traditionally limited to hepatologists who were most comfortable performing liver biopsies and managing complications of end-stage liver disease.25 A specialty that numbers 1,000-2,000 physicians in the US, there are as few as 1 hepatologist for every 330,000 Americans.26 This equates to 4.2 hepatologists per 10,000 Americans chronically infected. Issues with access to HCV specialists are not limited to the US. A study of 25 European countries found that patient groups in only 20% of European countries could access DAA treatment in the non-hospital setting, while another study found 94% of European countries to restrict DAA administration to specialists only.27,28

As less invasive alternatives to fibrosis measurement have replaced the need for liver biopsies, infectious disease (ID) physicians have begun filling the gap; however, the demand still exceeds the supply of these two specialties. By decentralizing HCV treatment away from the limited number of hepatologists and ID specialists, HCV patients can more easily access DAA therapy. People living with HCV may more readily begin therapy as services are expanded from the limited number of hepatologists and ID physicians to an increasing number of non-specialist providers. A meta-analysis of HCV care in the community demonstrated primary care clinics as a feasible treatment delivery system with increased rates of HCV treatment uptake (67.4% vs. 34.5%) and similar rates of SVR (94.9% vs 96.8%) compared to specialty care clinics.29

3.1. Advanced Practice Providers

Advanced practice providers (non-physician healthcare providers including nurse practitioners and physician assistants) can be leveraged to expand the pool of healthcare providers serving HCV patients. Shifting the responsibility of the pre-treatment evaluation – including RNA quantification, liver fibrosis, and genotype testing – to advanced practice providers reserves physician appointments for the provision and management of HCV therapy. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants have been successfully utilized in this model to address the high demand of HCV services in outpatient clinic settings.30 A non-randomized clinical trial demonstrated that advanced practice providers, primary care doctors, and specialty physicians produce equivalent rates of SVR among HCV+ patients.31 Expanding treatment to advanced practice providers will ensure equivalent quality of HCV patient care.

3.2. Telementoring for Primary Care Physicians

Project Expanding Capacity for Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO), a telementoring program initiated by the University of New Mexico in 2003, serves as a successful example of HCV provision by primary care physicians in rural communities without access to HCV specialists.32 With the goal of expanding hepatitis C services for underserved populations in the state, ECHO uses telementoring to connect primary care physicians with specialists in a ‘hub and spoke’ model via weekly videoconferencing.32 The hub consists of a single facility with a hepatologist, pharmacist, clinical nurse, and social worker, while the spokes are a number of community practitioners aiming to prescribe HCV therapy.32 The spoke reports deidentified cases to the hub; expert consensus from the hub then teaches the spokes through case-based learning and navigating care management.32 Since the US Congress passed the ECHO Act in 2016, similar programs have expanded nationally to increase the US physician capacity to treat HCV.33 Outside of the US, telementoring programs have been replicated in the Patagonia region of Argentina, improving rural primary care physicians’ ability to stage fibrosis, identify candidates for treatment, and select optimal HCV therapies.34

Expanding care to these generalist providers has not diminished patient care.31 ECHO has been demonstrated to promote equal HCV care outcomes by ECHO-telementored primary care physicians as university-based HCV specialists.21 These models enable primary care providers to provide best-practice care to rural and underserved populations.

5. Ancillary Personnel: Care Coordinators and Patient Navigators

Care coordinators and patient navigators are allied healthcare personnel included in HCV treatment programs to improve patient retention. These roles have been critical in HCV screening in EDs where care coordinators contact all HCV seropositive patients and schedule follow up care for those chronically infected.10 Care coordinators have also been used by ambulatory clinic settings that provide the full continuum of HCV services. In these settings, patient navigators maintain an active registry of all patients and their location in the care continuum, facilitating their progression towards achieving SVR.30 Once connected into care, care coordinators can monitor patients’ medication adherence and synchronize care among multiple healthcare providers.35

An economic evaluation of these services has calculated care coordination to be less than $95 USD per patient, per month.36 Studies to date involving HCV programs using care coordinators have been descriptive in the benefit of these services. To increase the implementation of these services, additional studies are needed to quantify the improvement care coordinators and patient navigators produce in HCV linkage to and retention in care.

6. Directly Observed Therapy

Directly observed therapy (DOT) is a system whereby patients receive medications under the supervision of a health care provider. DOT aims to increase treatment compliance by upholding a regular dose schedule and visually confirming dose administration. DOT models have proven to be effective in the treatment of chronic infections requiring complex therapy, such as tuberculosis and HIV.37,38

An increasing number of studies demonstrate that DOT is also both efficacious and well-received by patients in the treatment of HCV.37-40 HCV-infected, methadone-maintained patients who were treated in a pegylated-interferon DOT program were three times more likely to achieve SVR than those who self-administered treatment.41 With DAAs being easier to administer orally and having a lower side effect profile, it is conceivable that a DOT model may also prove effective in DAA therapy. The structure of DOT models may be customized to suit the capacity of individual facilities. The provider conducting the observation may include physicians, nurses, community health workers, or other trained staff, making DOT a feasible intervention in the absence of high-level providers.38,39,42 The setting is also flexible; DOT has demonstrated effectiveness in prisons, primary care clinics, hepatology clinics, drug treatment facilities, and pharmacies as patients who initiate treatment achieve SVRs ranging from 55% to 65%, up to 94% to 98%.39 A meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials demonstated that compared to standard treatment, DOT led to two-fold higher odds of achieving SVR.39

Studies have also demonstrated that DOT models may be especially effective for treating HCV in vulnerable populations.37,38 Patients who receive outpatient methadone therapy for opioid dependence have a convenient opportunity to treat their comorbid HCV infection with the addition of DOT to their methdone schedule. As an important driver of the spread of HCV, improving retention for PWID through interventions such as DOT is critical to reduce HCV incidence.38,39

7. Cost Reduction

The price of DAAs poses a significant challenge to achieving the WHO goal of HCV elimination by 2030. Ranging from $417 to $1,125 USD per day for 8 to 24 weeks, the high wholesale prices of these therapies are a primary barrier to their widespread adoption.43 Per pharmaceutical companies, the DAA prices are attributed to research and development costs.43 The wholesale acquisition cost of drugs is influenced by generics and market competition while the actual price consumers pay for the medications depends on a variety of factors including contracts, rebates, and discounts negotiated between payers and pharmaceutical companies.43,44 The recent introduction of DAAs to the market precludes generic options and competition that would benefit the payer and ultimately patient. Healthcare systems would benefit by adopting purchasing models that encourage patient treatment while minimizing costs. Some of these financial models include value-based payment, financial incentives and subscription models.

6.1. Value Based Payment

Early and complete HCV treatment has the potential to drastically curb overall costs, in addition to improving quality of life. Compared to an untreated individual, curing a single HCV+ patient saves $15,907 USD per year with incrementally increased savings each subsequent year.45 This equates to an estimated annual $1.5 billion USD savings by providing curative treatment for all HCV+ patients in the US. This cost reduction is attributed to avoided hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and prescription drug refills that significantly burden the individual, insurers, and overall health system alike.

Currently, the responsibility rests on the patient to seek care for their commonly asymptomatic HCV infection. Shifting the reimbursement structure of HCV healthcare has the potential to fund sustainable health systems designed to optimize HCV linkage to care. A value-based payment program tying reimbursement to patient health outcomes may provide financial incentives for programs to adopt practices that improve patient retention.33 Care1st Health Plan Arizona and Maricopa Integrated Health Systems announced in 2019 is the first US Medicaid plan to offer bundled payments through a value-based HCV treatment agreement.46 The program holds providers directly accountable for managing medication adherence and rewards maximal reimbursements for optimal patient outcomes. The program’s Community Connections Help Line connects members to social support resources leverages an integrated health approach to address patients’ various social determinants of health.46 This deviation from Arizona’s fee-for-service model serves as an auspicious prototype for a novel, patient-centered, and efficiency-focused approach to HCV treatment.

6.2. Subscription Model

In the traditional per-prescription revenue model, pharmaceutical companies increase revenue by increasing drug prices.47 This inherently limits access to the drug, especially to patients served by US state Medicaid and prison systems.47,48 This revenue model has left 85% of HCV patients in the US untreated.47 Creative financial strategies are essential to improve access to HCV treatment.

The revenue model for HCV shifted in 2015 when Australia purchased five years of unlimited DAAs for $1 billion Australian dollars (US$766 million).49 Modeling after the first two years of HCV therapy recipients in Australia, the country projected that over the course of the five-year program, it will treat over 104,000 patients at AU$9,595 (US$7,352) per patient compared to AU$16,260 (US$12,460) per patient without the lump-sum pricing.49 Through this plan, the Australian government will save an estimated AU$6.42 billion (US$4.92 billion).49

In 2018, Oklahoma was the first state in the US to adopt a subscription model for purchasing medications. Oklahoma negotiated an unlimited supply of antipsychotic medications for a flat recurring fee, now termed the “Netflix” subscription model.33 This landmark drug purchasing strategy used by Medicaid allowed drug manufacturers to bid for the rights to provide a drug within a state health market. By offering a lump sum payment to the winner(s) of the bid, pharmaceutical company revenues are decoupled from the price per pill.48 This strategy formed a national wave in the US with Michigan and Colorado obtaining US approval to engage in negotiations with drug manufacturers.50

In 2019, Louisiana was the first US state to implement the model for HCV DAA therapies, with Washington following suit.49,50 DAA manufacturers are incentivized to bid as the winner(s) become exempt from the Medicaid “best price rule” which mandates suppliers to extend the lowest negotiated price with one buyer to all other states in the Medicaid program.51

In addition to the government reaping significant savings, suppliers also share the financial benefit. The 5-year contract serves as a guaranteed, fixed revenue to suppliers even as the price of DAAs erodes with an increasing number of manufacturers entering the market.49 Suppliers may also find comfort knowing that the lump-sum agreement does not pinpoint a per-unit price, preventing other countries from boxing suppliers into offering the same rate.49 In the end, suppliers benefit from a boost in public relations by addressing public health, while also decreasing economic risk through a steady and dependable cash flow.47,49 A subscription model incentivizes payers and suppliers alike while helping guarantee patient access to HCV therapy.

8. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Despite DAA therapies boasting efficacy exceeding 95%, the profound treatment gap undermines the effectiveness of these new therapeutics. Strategies to improve delivery of and retention in HCV care include coupling of HCV services, decentralization of HCV providers, ancillary personnel in the HCV care team, directly observed therapy, and novel financial structures for HCV therapy. Those infected with HCV represent a fragile population with numerous comorbidities and competing health priorities. Efforts to improve retention must keep in mind the unique circumstances of this population.

In its 2018 guidelines, the World Health Organization called for a simplified service delivery model. This recommendation should be prioritized. Utilizing standardized algorithms, coupling orders through automated reflex testing, and localizing HCV services with other medical specialties would minimize follow-up visits and ease in navigation of the healthcare system by this underserved population. The interventions in this review aim to streamline HCV health services and improve retention in the HCV continuum of care.

Hepatitis C is a silent epidemic, burdening patients, communities, and healthcare systems alike. The treatment delivery strategies discussed in this review are limited by diagnosis of infected patients. Both the HCV diagnostic and treatment gaps must be addressed to effectively eradicate HCV. Continued research and novel interventions are needed to improve detection and linkage to care for all chronically HCV-infected patients.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences [5TL1TR001418 to A.T.J.] and the Emergency Medicine Foundation/Society of Academic Emergency Medicine Foundation Medical Student Research Grant [A.T.J.].

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Persons Diagnosed with Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection.; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofmeister MG, Rosenthal EM, Barker LK, et al. Estimating prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 2013-2016. Hepatology. 2018;0(0):2013–2016. doi: 10.1002/hep.30297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spearman CW, Dusheiko GM, Hellard M, Sonderup M. Hepatitis C. Lancet. 2019;394(10207):1451–1466. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32320-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Negro F, Forton D, Craxì A, Sulkowski MS, Feld JJ, Manns MP. Extrahepatic morbidity and mortality of chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1345–1360. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falade-Nwulia O, Suarez-Cuervo C, Nelson DR, Fried MW, Segal JB, Sulkowski MS. Oral direct-acting agent therapy for hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(9):637–648. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0061-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer AY, Wade AJ, Draper B, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of primary versus hospital-based specialist care for direct acting antiviral hepatitis C treatment. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;76:102633. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.102633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis: 2016-2021.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viner K, Kuncio D, Newbern EC, Johnson CC. The continuum of hepatitis C testing and care. Hepatology. 2015;61(3):783–789. doi: 10.1002/hep.27584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yehia BR, Schranz AJ, Umscheid CA, Lo Re V. The treatment cascade for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson ES, Galbraith JW, Deering LJ, et al. Continuum of care for hepatitis C virus among patients diagnosed in the emergency department setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(11):1540–1546. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reau N, Marx S, Manthena SR, Strezewski J, Chirikov VV. National examination of HCV linkage to care in the United States (2013-2016) based on large real-world dataset. Hepatology. 2018;68(S1):892A–893A. doi: 10.1002/hep.30257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartlett SR, Yu A, Chapinal N, et al. The population level care cascade for hepatitis C in British Columbia, Canada as of 2018: Impact of direct acting antivirals. Liver Int. 2019;39(12):2261–2272. doi: 10.1111/liv.14227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Global Hepatitis Report 2017. 2017. doi: 10.1149/2.030203jes [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linas BP, Barter DM, Leff JA, et al. The hepatitis C cascade of care: identifying priorities to improve clinical outcomes. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AASLD-IDSA Hepatitis C Guidance Panel. HCV guidance: Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. 2021. https://www.hcvguidelines.org/sites/default/files/full-guidance-pdf/AASLD-IDSA_HCVGuidance_October_05_2021.pdf.

- 16.Bruggmann P, Litwin AH. Models of care for the management of hepatitis C virus among people who inject drugs: One size does not fit all. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(S2):S56–61. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coyle C, Moorman AC, Bartholomew T, et al. The hepatitis C virus care continuum: linkage to hepatitis C virus care and treatment among patients at an urban health network, Philadelphia, PA. Hepatology. 2019;0(0):1–11. doi: 10.1002/hep.30501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945-1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-4):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin M, Kramer J, White D, et al. Barriers to hepatitis C treatment in the era of direct-acting anti-viral agents. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(10):992–1000. doi: 10.1111/apt.14328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLaren M, Garber G, Cooper C. Barriers to hepatitis C virus treatment in a Canadian HIV-hepatitis C virus coinfection tertiary care clinic. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22(2):133–137. doi: 10.1155/2008/949582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimova RB, Zeremski M, Jacobson IM, Hagan H, Des Jarlais DC, Talal AH. Determinants of hepatitis C virus treatment completion and efficacy in drug users assessed by meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(6):806–816. doi: 10.1093/cid/cisl [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho SB, Bräu N, Cheung R, et al. Integrated care increases treatment and improves outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection and psychiatric illness or substance abuse. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(11):2005–2014.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groessl EJ, Liu L, Sklar M, Ho SB. HCV integrated care: a randomized trial to increase treatment initiation and SVR with direct acting antivirals. Int J Hepatol. 2017;2017:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2017/5834182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris L, Smirnov A, Kvassay A, et al. Initial outcomes of integrated community-based hepatitis C treatment for people who inject drugs: findings from the Queensland Injectors’ Health Network. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;47:216–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGovern BH. Hepatitis C virus and the infectious disease physician: a perfect match. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(3):414–417. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russo MW, Koteish AA, Fuchs M, Reddy KG, Fix OK. Workforce in hepatology: update and a critical need for more information. Hepatology. 2017;65(1):336–340. doi: 10.1002/hep.28810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazarus JV, Stumo SR, Harris M, et al. Hep-CORE: a cross-sectional study of the viral hepatitis policy environment reported by patient groups in 25 European countries in 2016 and 2017. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21:e25052. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marshall AD, Cunningham EB, Nielsen S, et al. Restrictions for reimbursement of interferon-free direct-acting antiviral drugs for HCV infection in Europe. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(2):125–133. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30284-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radley A, Robinson E, Aspinall EJ, Angus K, Tan L, Dillon JF. A systematic review and meta-analysis of community and primary-care-based hepatitis C testing and treatment services that employ direct acting antiviral drug treatments. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4635-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartholomew TS, Grosgebauer K, Huynh K, Cos T. Integration of hepatitis C treatment in a primary care federally qualified health center; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2015-2017. Infect Dis Res Treat. 2019;12:1–7. doi: 10.1177/1178633719841381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kattakuzhy S, Gross C, Emmanuel B, et al. Expansion of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by task shifting to community-based nonspecialist providers: a nonrandomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(5):311–319. doi: 10.7326/m17-0118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marciano S, Haddad L, Plazzotta F, et al. Implementation of the ECHO telementoring model for the treatment of patients with hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 2017;89:660–664. doi: 10.1002/jmv [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ford MM, Jordan AE, Johnson N, et al. Check Hep C: a community-based approach to hepatitis C diagnosis and linkage to care in high-risk populations. J Public Heal Manag Pract. 2018;24(1):41–48. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohsen W, Chan P, Whelan M, et al. Hepatitis C treatment for difficult to access populations: Can telementoring (as distinct from telemedicine) help? Intern Med J. 2019;49:351–357. doi: 10.1111/imj.14072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woodrell C, Weiss J, Branch A, et al. Primary care-based hepatitis C treatment outcomes with first-generation direct-acting agents. J Addict Med. 2015;9(5):405–410. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Behrends CN, Eggman AA, Gutkind S, et al. A cost reimbursement model for hepatitis C treatment care coordination. J Public Heal Manag Pract. 2019;25(3):253–261. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cioe PA, Stein MD, Promrat K, Friedmann PD. A comparison of modified directly observed therapy to standard care for chronic hepatitis C. J Community Health. 2013;38(4):679–684. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9663-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gunn J, Higgs P. Directly observed hepatitis C treatment with opioid substitution therapy in community pharmacies: a qualitative study. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2019;16(9):1298–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDermott CL, Lockhart CM, Devine B. Outpatient directly observed therapy for hepatitis C among people who use drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Virus Erad. 2018;4(2):118–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coffin PO, Santos GM, Behar E, et al. Randomized feasibility trial of directly observed versus unobserved hepatitis C treatment with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir among people who inject drugs. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonkovsky H, Tice A, Yapp R, et al. Efficacy and safety of peginterferon alfa-2a/ribavirin in methadone maintenance patients: randomized comparson of direct observed therapy and self-administration. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2757–2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schütz A, Moser S, Schwanke C, et al. Directly observed therapy of chronic hepatitis C with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir in people who inject drugs at risk of nonadherence to direct-acting antivirals. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25(7):870–873. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woolston SL, Kim HN. Cost and access to direct-acting antiviral agents. Hepatitis C Online. https://www.hepatitisc.uw.edu/go/evaluation-treatment/cost-access-medications/core-concept/all. Published 2018. Accessed July 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenthal ES, Graham CS. Price and affordability of direct-acting antiviral regimens for hepatitis C virus in the United States. Infect Agent Cancer. 2016;11(24):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13027-016-0071-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roebuck MC, Liberman JN. Assessing the burden of illness of chronic hepatitis C and impact of direct-acting antiviral use on healthcare costs in Medicaid. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(8):S131–S139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamm N. The first hep C value-based bundled payment plan. Manag Healthc Exec. July 2019. https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/first-hep-c-value-based-bundled-payment-plan. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trusheim MR, Cassidy WM, Bach PB. Alternative state-level financing for hepatitis C treatment—the “Netflix Model”. J Am Med Assoc. 2018;320(19):1977–1978. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sood N, Ung D, Shankar A, Strom BL. A novel strategy for increasing access to treatment for hepatitis C virus infection for Medicaid beneficiaries. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:118–119. doi: 10.7326/M18-0186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moon S, Erickson E. Universal medicine access through lump-sum remuneration — Australia’s approach to hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(7):607–610. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1812959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waddill K. CMS approves WA value-based purchasing plan for hepatitis C drugs. HealthPayerIntelligence. June 2019. https://healthpayerintelligence.com/news/cms-approves-wa-value-based-purchasing-plan-for-hepatitis-c-drugs. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS approves Louisiana state plan amendment for supplemental rebate agreements using a modified subscription model for hepatitis C therapies in Medicaid. CMS.gov. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-approves-louisiana-state-plan-amendment-supplemental-rebate-agreements-using-modified. Published 2019. Accessed July 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]