Abstract

With economic globalization, there has been a rapid increase in the number of sojourners in the workforce and in international education. However, little is known about the impact of career adaptability (a key psychosocial resource for managing career transitions) on international students’ adaptation in cross-cultural contexts, particularly their quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on career construct theory, this study examined how career adaptability directly and indirectly enhances international students’ quality of life through perceived online and offline social support, and how the COVID-19 pandemic affected their adaptation in cross-cultural context. With a sample of 328 African international students in China, we found that career adaptability and perceived online/ offline social support were positively related to the quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, perceived offline social support, but not perceived online social support, was an adapting response through which career adaptability enhances international students’ quality of life in cross-cultural context. The mediating effect of perceived offline social support diminished when the self-rated COVID-19 impact on international students was severe. These findings provide a basis for future psychosocial interventions to enhance international students’ adaptation to cross-cultural contexts during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: International students, Quality of life, Career adaptability, Perceived offline social support, Perceived online social support, COVID-19 impact

Introduction

With the globalization of the economy, the number of sojourners in the workforce and international education is rapidly increasing (OECD, 2018). International students distinguish themselves from other sojourners in the quest for desirable educational opportunities and better future career prospects. Generally, they are more focused on their professional future and work harder to prepare for it, demonstrating higher career adaptability (Presbitero & Quita, 2017). In addition, cross-cultural experiences can activate and further enhance their career adaptability, and facilitate adaptation to new cultural environments (Campion, 2018, Guan et al., 2018). Career adaptability may be a vital psychological resource for international students to cope with challenges (e.g., social, cultural, and psychological adaptation) during intense cross-cultural transition processes (Mesidor & Sly, 2016). In line with this, empirical studies have shown that individuals with higher career adaptability among international students showed higher career exploration and better future employability in cross-cultural contexts (Brown et al., 2021, Guan et al., 2018). Although the positive effects of career adaptability on intercultural adaptation have been investigated and highlighted among sojourners (i.e., expatriates) and immigrants in recent years (Ayala et al., 2020, Jannesari and Sullivan, 2019, Presbitero and Quita, 2017), little attention has been paid to how career adaptability can help international students cope with adjustment issues in cross-cultural contexts.

Career adaptability and quality of life

Career adaptability is proposed by Career Construct Theory (CCT) and refers to a set of psychosocial resources including career concern (pay more attention to the vocational future), career control (put more effort into preparing for their vocational future), career curiosity (be more willing to explore possible selves and future scenarios), and career confidence (have more confidence to pursue their adaptation goals) for adapting to and dealing successfully with career transitions and challenges (Savickas & Porfeli, 2012). The outcomes of successful adaptation, indicated by success, satisfaction, and well-being, are expressed in many forms, including not only career-related outcomes (e.g., job performance) but also life outcomes (e.g., life satisfaction) (Rudolph et al., 2017, Savickas, 2020). Emerging evidence supports the positive impact of career adaptability on quality of life, which is defined by WHO as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” (The WHOQOL Group, 1998). Students with higher career adaptability perceived fewer internal and external career barriers, showing a higher quality of life (Sores et al., 2012). Besides, a longitudinal study showed that increased career adaptability predicted additional changes in quality of life beyond other variables such as socio-demographic variables, positive emotions and sense of power among students and immigrant student sample (Hirschi, 2009). Similarly, for international students, career adaptability may be an important psychological resource to address intercultural, life and career challenges, which in turn, improves their quality of life (Ayala et al., 2020, Ginevra et al., 2017, Urbanaviciute et al., 2019). Therefore, the current study directly investigated whether international students with higher career adaptability have a higher quality of life in cross-cultural contexts.

Hypothesis 1

In a cross-cultural context, career adaptability is positively correlated with the quality of life of international students.

The mediation role of perceived social support

The career construction model of adaptation assumes that a sequence of career adaptation was the result of the interplay of trait-like psychological characteristics (adaptivity), psychological resources (adaptability), and behaviors and beliefs (adapting responses) (Rudolph et al., 2017, Savickas, 2020). That is, individuals who are willing to adapt or prepare to change (adaptivity) bring self-regulation resources (adaptability) to shape their behaviors or beliefs (adapting responses) to address changing conditions, which in turn secures positive outcomes (adaptation). Campion (2018) extended such an adaptation model to refugees in the cross-cultural contexts and stated that refugees’ arrival in a host country activates their career adaptability and influences successful resettlement and adaptation via social capital. Social support, including the actual social relationships and perceived social support (Saegert & Carpiano, 2017), is stressed as the primary and crucial social capital for yielding higher levels of subjective success (e.g., life satisfaction, health), although structural and personal barriers (e.g., language fluency) still limit objective success (e.g., salary, promotions) of refugees (Campion, 2018). Like refugees, when international students move to the host country, their previously established social support system in the home country is almost unavailable, leading to social isolation and a lack of social capital in the host country (Bierwiaczonek and Waldzus, 2016, Jiang et al., 2020). Building a new social network and a new social context belief, such as perceived social support, maybe a primary adapting response for international students in their cross-cultural adaptation. Preliminary research also revealed that career exploration, especially environmental exploration through social interactions in the host country (i.e., individuals collect relevant information about the external environment), is a crucial adapting response among international students (Brown et al., 2021, Guan et al., 2018). Moreover, a high level of career adaptability was found to enable individuals to engage in more exploration behaviors (Guan et al., 2017). Given the theory as mentioned above and empirical data, it is plausible that career adaptability may influence international students’ quality of life through perceived social support.

As the context belief of available social support for daily life (Hirschi, 2009, Procidano and Smith, 1997), perceived social support includes perceived online social support (e.g., gain emotional support from online activities/communities) and perceived offline social support (e.g., gain emotional support from offline activities/communities) (Wang & Wang, 2013). According to CCT, individuals higher in career adaptability tend to hold self-beliefs about their capacity to successfully execute a course of action and overcome obstacles to achieve adaptation goals (Savickas, 2020). It may be easier for international students with such self-beliefs to form or build a variety of adaptive beliefs and feel more productive in coping with career-related transitions. Empirical studies found that individuals who perceived more social support show better performance and psychological adaptation among international students (Ng et al., 2017, Shu et al., 2020). During cross-cultural transitions, perceived social support may mediate the positive relationship between career adaptability and quality of life for international students. Career adaptability may enhance international students’ adapting beliefs (i.e., perceived social supports), including perceived online social support and perceived offline social support, which would be associated with a better quality of life in the host country. Based on the CCT and earlier empirical studies on adaptive beliefs, we propose the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

Both perceived online social support (H2a) and perceived offline social support (H2b) would mediate the association between career adaptability and quality of life for international students.

The moderation role of COVID-19 impact

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected all aspects of people’s lives, leading to changes in social interactions, work behaviors, and mental health (Jang and Choi, 2020, Trougakos et al., 2020). From an individual-contextual interaction perspective, the COVID-19 pandemic, as an important contextual factor, interacts with individual factors (e.g., career adaptability) to influence individuals’ behaviors and outcomes (Akkermans et al., 2020). What is currently lacking, however, is a better understanding of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adaptation in cross-cultural contexts.

According to CCT, contextual factors interact with career adaptability during the adaptation process. Maggiori et al. (2013) found that individuals in more precarious situations face greater stress, and in such situations, it is more difficult to activate and trigger their career adaptability. Similarly, the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic can exert additional pressures on international students, such as difficulties in returning home, separation from family, and strong feelings of isolation (Lai et al., 2020, Ma and Miller, 2020). The impact of COVID-19 may amplify the stress of international students, leading to greater stress in their host societies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, this more unstable and stressful situation may make it more difficult for international students to activate their career adaptability to form an adaptive belief (i.e., perceived social support) and achieve adaptation (i.e., quality of life). Specifically, when international students were more affected by COVID-19, the relationship between career adaptability and perceived social support and the relationship between career adaptability and quality of life were weaker. Drawing on CCT and previous empirical work, we further propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3

The relationship between career adaptability and quality of life will be weaker for international students with a higher COVID-19 impact.

Hypothesis 4

The relationship between career adaptability and perceived social support will be weaker for international students with a higher COVID-19 impact.

Hypothesis 5

The relationship between career adaptability and quality of life via perceived social support is moderated by COVID-19 impact in such a way that, when individuals report higher COVID-19 impact, the indirect effect is weaker.

Within the international student population, African international students face more cultural adjustment stress than international students from other regions (i.e., Europe, America, Oceania, and Asian countries) because of the greater gap between their culture of origin and the host culture in terms of political and economic structure, level of technology, and climate (Constantine et al., 2004, Yu et al., 2014). In addition, most African international students show no intention to return to their home countries (Li & Sun, 2019). The unfavorable conditions that African international students face in the labor market of their host countries may force them to develop higher adaptability and secure better adaptation to support their future employability (Brown et al., 2021). Thus, the present study recruited the second-largest group of international students in China: African students (Ministry of Education in China, 2019). This study will shed light on the potential pathways for the impact of career adaptability on cross-cultural adjustment of international students, particularly African international students, during and post the COVID-19 pandemic.

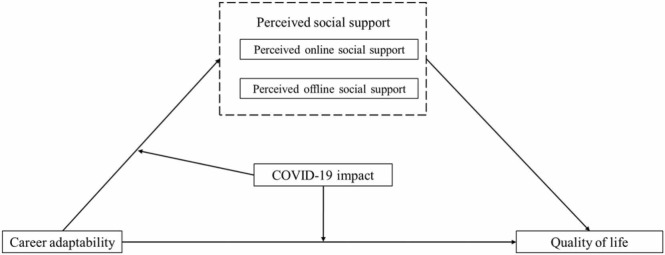

The aim of this study was to examine how international students’ career adaptability predicted their perceived social support and quality of life during the cross-cultural transition, and whether COVID-19 impact served as a significant moderator on these effects. The overall model for this study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The hypothesized model.

Method

Participants

A total of 364 African international students in China participated in the online survey study between December 2020 and January 2021. Thirty-six participants were excluded from the analysis because they completed the questionnaire with a series of consistent responses equal to or greater than half the length of the total scale (Curran, 2016). The final sample consisted of 328 African international students (223 males and 105 females). Almost three-quarters (76.8 %) of this sample were from West Africa. The majority (66.5 %) of participants were between 25 and 34 years of age, 19.2 % were between 18 and 24 years of age and 14.3 % were over 35 years of age. The majority (58.5 %) of participants self-reported they had stayed in China for one to two years, 38.1 % for more than two years, and 3.4 % for less than a year. There are 36.3 % of participants who self-reported their Chinese language proficiency was neither poor nor good, 34.5 % were good at Chinese, and 29.3 % were poor at Chinese. Of these participants, 15.9 % were undergraduates, 52.4 % were postgraduate students, 24.1% were PhD students, and 7.6 % were other degree students. Most of the participants (58.2 %) received full scholarships, 24.1 % received partial scholarships, and 17.7 % were self-funded. Most of the participants (60.9 %) had worked experience before coming to China.

Procedure

Data were collected using online survey methods. Participants were recruited from social media (e.g., WeChat, Facebook) through online advertisements. Before starting the survey, they were given informed consent and completed the survey in English through a web-based survey platform in China, the Wenjuanxing platform (www.wjx.cn). Upon completion, participants received a report and gained a random bonus ranging from three to five RMB.

Measures

Career adaptability

Career adaptability was assessed by the Career Adaptabilities Scale-Short Form (CAAS-SF) (Maggiori et al., 2015). It’s a 12-item self-report inventory. Each of the four subscales has three items: Concern, Control, Curiosity, and Confidence. Responses are rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with a total score of 12–60. Higher scores indicate greater career adaptability. In the present sample, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the total scale was 0.95, while the Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.91 for Concern, 0.91 for Control, 0.89 for Curiosity, and 0.89 for Confidence subscales.

Perceived online/ offline social support

Both perceived online and offline social support was measured by a 6-item scale, respectively. It was adapted from the Brief Form of the Perceived Social Support Questionnaire (F-SozU K-6) to measure three aspects of perceived social support (i.e., standard support, emotional support, and social integration) (Lin et al., 2019). The sample items for perceived online and offline social support were as follows: “I know several people with whom I like to do things in the online community/ in offline activities”, and “I experience a lot of understanding and security from others in online/ offline activities”. Responses were rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with a total score of 6–30. Higher scores indicate greater perceived social support. In the present sample, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of perceived online social support was 0.89, and the Cronbach’s α coefficient of perceived offline social support was 0.90.

COVID-19 impact

COVID-19 impact was measured with an item (Tull et al., 2020): “To what extent do you feel COVID-19 has impacted you since the outbreak?”. Participants responded using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (No impact) to 5 (Great impact).

Quality of life

Quality of life was measured by the World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument, Short Form (WHOQOL-BREF) (The WHOQOL Group, 1998). The WHOQOL-BREF is a self-report questionnaire containing 26 items. One item refers to the overall quality of life, and another item refers to general health. The remaining 24 items are distributed among four quality of life domains: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. Items were answered on a 5-point Likert scale, and domain scores ranged from 4 to 20. Higher scores denoted higher quality of life. In the present sample, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the total scale was 0.93, while the Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.77 for physical health, 0.81 for psychological health, 0.73 for social relationships, and 0.83 for environment domains.

Control variables

Gender, Chinese language proficiency and length of residence in China were the control variables. Previous research has shown that gender, language proficiency, and length of residence in the host country were significantly related to international students’ social support or quality of life (Bender et al., 2019, English et al., 2021, Shu et al., 2020).

Statistical analyses

To evaluate the models, we used structural equation modeling with maximum likelihood estimation in M-plus 8.3. The 95 % bias-corrected confidence intervals based on 5000 bootstrap samples were applied to judge the statistical significance of the mediation and moderation effects.

The fit was assessed by the chi-square test (χ2), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Previous research recommended that CFI ≥ 0.90, TLI ≥ 0.90, RMSEA ≤ 0.08, SRMR ≤ 0.08 indicates an acceptable fit, while CFI ≥ 0.95, TLI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.06, SRMR ≤ 0.06 indicates a good fit (Hu and Bentler, 1999, Sahoo, 2019). Moderation is indicated when there is a significant path from the interaction term to an outcome variable. Furthermore, simple slope analyses and the Johnson-Neyman technique were used to plot simple effect graphs to better understand the moderating effect (Spiller, et al., 2013).

Results

Confirmatory factor analyses

Given that our data were collected from a common resource, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to demonstrate that these measures captured distinctive factors. The results showed that the four-factor model (career adaptability, online social support, offline social support, quality of life) fit the data well, χ2(1066) = 2031.172, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.06. Additional analyses showed that the four-factor model is a significantly better fit than the three-factor, two-factor, and one-factor models.

Preliminary analyses

Before testing structural models, manifest variables were tested for skewness and kurtosis, and manifest correlations were examined. No skewness and kurtosis statistics exceeded an absolute value of 1. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among four manifest variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Career adaptability | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Perceived online social support | -0.01 | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Perceived offline social support | 0.16** | 0.25** | 1 | |||||

| 4. COVID-19 impact | -0.01 | -0.08 | -0.02 | 1 | ||||

| 5. QOL-Physical health | 0.20** | 0.18** | 0.38** | -0.21** | 1 | |||

| 6. QOL-Psychological health | 0.38** | 0.12* | 0.42** | -0.11* | 0.66** | 1 | ||

| 7. QOL-Social relationship | 0.19** | 0.25** | 0.43** | -0.09 | 0.55** | 0.59** | 1 | |

| 8. QOL-Environment | 0.21** | 0.21** | 0.44** | -0.16** | 0.72** | 0.67** | 0.59** | 1 |

| Mean | 47.00 | 18.29 | 21.32 | 3.94 | 15.03 | 15.38 | 14.44 | 14.69 |

| SD | 9.75 | 5.17 | 4.67 | 1.01 | 2.54 | 2.48 | 3.30 | 2.32 |

Note. QOL: Quality of life, SD: Standard deviation.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

Career adaptability was positively associated with perceived offline social support (r = 0.16, p = 0.004), but was not associated with perceived online social support (r = −0.01, p = 0.860). Perceived online social support was positively associated with perceived offline social support (r = 0.25, p < 0.001) and four domains of quality of life (r = 0.18, 0.12, 0.25, 0.21, respectively, ps < 0.05). Perceived offline social support was positively associated with four domains of quality of life (r = 0.38, 0.42,0.43 and 0.44, respectively, ps < 0.001). COVID-19 impact was negatively associated with quality of physical health, psychological health and environment (r = −0.21, −0.11, −0.16, respectively, ps < 0.05).

Testing the mediation model

To rule out potential confounding background effects, gender, Chinese language proficiency and length of residence in China were controlled when testing the hypotheses. The mediation model had a good fit, χ2(215) = 452.96, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.058, SRMR = 0.051.

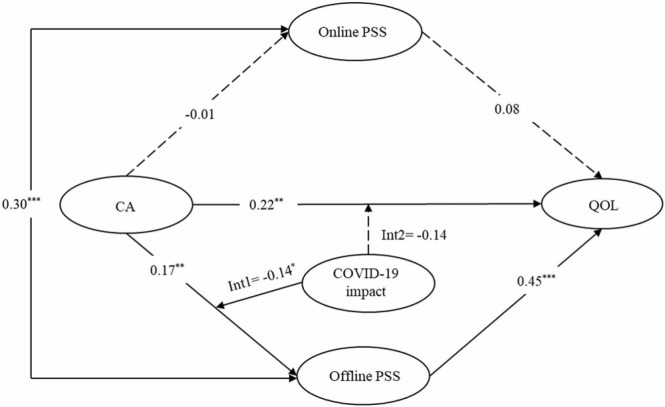

The regression analysis results showed that career adaptability was significantly related to the quality of life (β = 0.22, SE = 0.07, p = 0.001), consistent with Hypothesis 1. There was a significant effect of career adaptability on perceived offline social support (β = 0.17, SE= 0.06, p = 0.003), but not on perceived online social support (β = −0.01, SE = 0.06, p = 0.835). The positive path from perceived offline social support to quality of life was also significant (β = 0.45, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001), whereas the path from perceived online social support to quality of life was not significant (β = 0.08, SE = 0.06, p = 0.199). Thus, Hypothesis 2b was supported, while Hypothesis 2a wasn’t supported.

The mediation analysis showed a significant indirect effect from career adaptability to quality of life (indirect effect = 0.08; total effect = 0.30). The estimated indirect effect from career adaptability to quality of life through perceived offline social support was significant (mediation effect = 0.08, p = 0.006, 95 %CI [0.03, 0.13]), but the indirect effect through perceived online social support was insignificant (mediation effect = −0.001, p = 0.861, 95 %CI [−0.02, 0.01]). In sum, perceived offline social support mediated the effect of career adaptability on quality of life, which supported Hypothesis 2b (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The moderated mediation model, Note. The model about perceived online/offline social support mediating the effect of career adaptability on quality of life with COVID-19 impact as moderation. Path coefficients are standardized estimates (β). Gender, Chinese language proficiency and length of resident in China were controlled in the model. Solid lines indicate significant paths, while dashed lines indicated insignificant pathways. CA: Career adaptability, PSS: perceived social support, QOL: Quality of life, Int: interaction. * p < 0.05, * * p < 0.01, * ** p < 0.001.

Testing the moderated mediation model with COVID-19 impact as a moderator

The parameter estimates for the moderated mediation model fit the data well, χ2 (327) = 634.82, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.054, SRMR = 0.047. There was a significant direct effect of COVID-19 impact on quality of life (β = −0.16, SE = 0.06, p = 0.006). The effect of the interaction between career adaptability and COVID-19 impact on quality of life was marginally significant (β = −0.14, SE = 0.07, p = 0.051). It means further research with a large sample size are needed to examined Hypothesis 3. There was no significant direct effect of COVID-19 impact on perceived offline social support (β = −0.01, SE = 0.06, p = 0.833). The interaction term between career adaptability and COVID-19 impact had a significant effect on perceived offline social support (β = −0.14, SE = 0.07, p = 0.030). It demonstrated that the association between career adaptability and perceived offline social support depended on the level of COVID-19 impact, which supports Hypothesis 4.

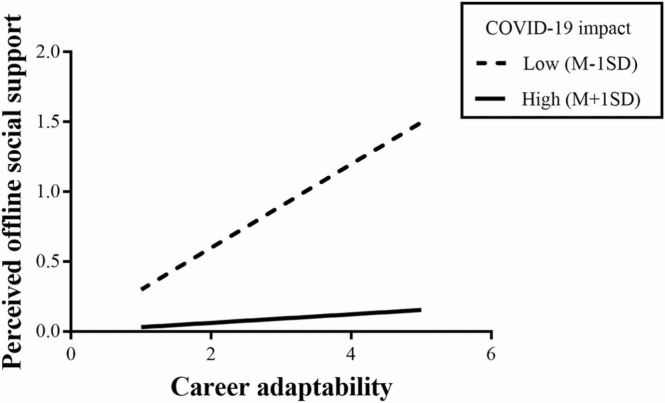

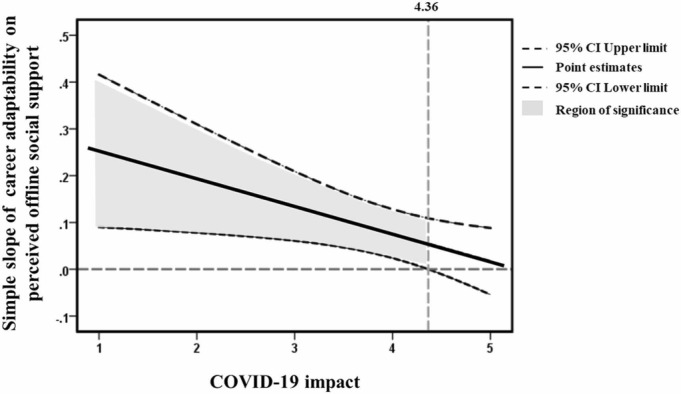

As shown in Fig. 3, simple slope analyses revealed that the positive association between career adaptability and perceived offline social support was significant when COVID-19 impact was low (β = 0.30, p = 0.001), though not when COVID-19 impact was high (β = 0.03, p = 0.726). A Johnson-Neyman plot of continuous predictors showed that high career adaptability was related to greater perceived offline social support when COVID-19 impact was lower than 4.36. In contrast, the association between career adaptability and perceived offline social support was absent among participants with higher COVID-19 impact (i.e., above 4.36) (see Fig. 4). Conditional indirect effects of career adaptability on quality of life via perceived offline social support at different levels of COVID-19 impact were presented in Table 2. As seen from the conditional indirect effect analysis, two of the three conditional indirect effects (based on the moderator values at mean and at −1 standard deviation) were positively and significantly different from zero. Namely, the indirect effect of career adaptability on quality of life through perceived offline social support was observed when COVID-19 impact was moderated to low, but not when COVID-19 impact was high. Thus, Hypothesis 5 was supported.

Fig. 3.

Interaction of COVID-19 impact and career adaptability in predicting perceived offline social support, Note. M: Mean, SD: Standard deviation.

Fig. 4.

The Johnson-Neyman plot of COVID-19 impact, Note. CI: Confidence interval.

Table 2.

Conditional indirect effects of career adaptability on quality of life via perceived offline social support at different levels of COVID-19 impact.

| COVID-19 impact | Indirect effect | SE | 95 % CI of Indirect effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low: Mean − 1 SD | 0.17 | 0.06 | [0.09, 0.29] |

| Mean | 0.10 | 0.04 | [0.04, 0.17] |

| High: Mean + 1 SD | 0.02 | 0.05 | [−0.06, 0.02] |

Note. CI: Confident interval, SE: Standard error, SD: Standard deviation.

Discussion

Based on career construct theory (Savickas, 2020), we examined how international students’ career adaptability in a cross-cultural context predicted their quality of life through perceived social support (including online and offline perceived social support) and whether the impact of COVID-19 acted as a significant moderating variable for these effects in a sample of African international students in China. We found that only perceived offline social support mediated the relationship between career adaptability and quality of life. Furthermore, the indirect effect of career adaptability on quality of life through perceived offline social support was weaker when the impact of COVID-19 impact was higher.

The mediation model of career adaptability, perceived social support, and quality of life

This study extended the career construction theory by showing that perceived social support, as an aspect of social context beliefs, is an important adapting response of international students during the cross-cultural transition, particularly African international students. These findings suggest that perceived social support is one of the key links between career adaptability and quality of life in a new cultural environment. When moving to the host country, international students left much of their social support system behind. To cope with this change, they tend to reform their social contextual belief about the availability of social support in the host country and build a new social support system, which is the best coping strategy for cross-cultural transition (Bierwiaczonek & Waldzus, 2016). Furthermore, the findings showed that perceived offline social support mediated the relationship between career adaptability and quality of life, whereas perceived online social support did not. That is, international students with higher career adaptability would believe that they could receive support from their offline social networks. This stronger belief in their offline social environment would increase the satisfaction with social relationships, report happier feelings and ultimately lead to a higher quality of life in the host country (Shu et al., 2020, Siedlecki et al., 2014).

Contrary to our expectations, career adaptability does not predict perceived online social support. A possible explanation is that individuals do receive and perceive social support in online contexts when they seek advice online, but online social support also makes individuals more likely to be addicted and feel more stressed (Lin et al., 2018; Utz & Breuer, 2017). It is difficult to distinguish between the positive and negative effects of perceived online social support. Therefore, the relationship between career adaptability and perceived online social support may be underestimated because of the opposite effects of perceived online social support.

The moderating role of COVID-19 impact

Since the COVID-19 outbreak, there have been repeated calls for more research on the impact of COVID-19 (Akkermans et al., 2020, Cho, 2020). The present study answers these calls by examining the relationship between the theoretical construct of career adaptability and the impact of COVID-19 on international students. The significant indirect effect of career adaptability on quality of life through perceived offline social support was weaker for those international students who reported a higher COVID-19 impact. The results indicated that the contribution of career adaptability on international students’ perceived offline social support is influenced by the impact of COVID-19. The present findings provided novel evidence for the interaction relationship between career adaptability and contextual factors.

Savickas (2013) argues that career adaptability is more easily modified by training, education and experience, that it can be activated to cope with life and career challenges (such as transitions or traumas) and that it interacts dynamically with contextual factors. Previous research has shown that career adaptability was more effective when individuals experienced work-related life events (Urbanaviciute et al., 2019). In contrast to these concepts, the moderated mediation model in the current study suggests that in the COVID-19 pandemic context, activating and triggering adaptability resources appears to be more difficult for international students in the context of greater COVID-19 impact. According to situational strength theory, personality characteristic (e.g., traits and resources) predicts individual behavior and relevant outcomes in “weak” situations, but in “strong” situations, situational characteristic forces individuals to behave in a particular way and the influence of personality characteristic is diminished (Meyer et al., 2020). Compared to daily work-related life events (a weak situation), the COVID-19 pandemic is less controllable and more unpredictable for individuals (a strong situation), which leads international students to study in a quite unstable and stressful environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. When self-rated COVID-19 impact is severe (i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic is a strong situation), regardless of their level of career adaptability, international students may keep themselves away from COVID-19 infection in the first place, rather than accumulate social capital. That is, the COVID-19 pandemic suppresses the beneficial effect of career adaptability. Therefore, such a strong situation is a barrier to international students’ activation of career adaptability in the host country. Considering the earlier empirical work and the findings in the present study, the effect of stressful contextual conditions on career adaptability may be an inverted U-shape. Specifically, career adaptability is difficult to be effectively activated either when the situational strength is too weak or too strong. Future research should further explore such interaction effects between the situational strength and career adaptability on adaptation outcomes.

Practical implications

In addition to its theoretical implications, this study also has implications for career counseling and higher education practice. First, career counselors should assess international students’ self-regulation resources (i.e., career adaptability) and areas for improvement. The present findings showed that career adaptability is positively related to successful adaptation in the host society. International students scoring in the lower end of any adaptability dimensions (i.e., 25th percentile or lower) may require interventions tailored to the specific needs of the individual (Taber, 2019). For example, either before or after being international students, individuals with low levels of career concern may not give much thought to their career futures. In these cases, interventions to increase one’s future time perspectives may be required to improve their intercultural adaptation.

Secondly, the positive effects of career adaptability on quality of life through perceived offline social support rather than perceived online social support suggests that international students should be more involved in offline social activities rather than social interactions merely through online networks. Higher education institutions should also provide more opportunities for international students to interact with local students and to engage in offline activities, in order to facilitate a more adaptive belief about the offline support they can receive. Specifically, local higher education institutions should organize more tailored cultural and employment-related activities, such as culture corner, internships, skill development and volunteer activities designed for African international students. Such practices are expected to benefit international students' quality of life in general, and the adaptation and career development of African students in particular.

Thirdly, the moderating effect of COVID-19 impact suggests that the higher education institutions should provide more security for international students in the host country to reduce the impact of COVID-19, so that their career adaptability can be effectively activated to carry out adapting responses and achieve adaptation outcomes. More attention should be paid to international students with great COVID-19 impact.

Limitations and future research directions

Despite the above theoretical and practical implications, the present study should be considered to have the following limitations. First, this study used a cross-sectional, single-survey design that made it difficult to confirm the direction of causality. Therefore, further studies should use a longitudinal design to capture changes in international students’ career adaptability, perceived social support and quality of life over time. Second, future research should consider the effect of return intention in the relationship between career adaptability and adaptations. Third, since the present study was conducted in a sample of African international students in China, more research should be done to examine whether the current findings can be generalized to international student samples in other countries or other cultural contexts.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study adds to our understanding of international students’ adaptation during the cross-cultural transition. It extends the literature on the effects of career adaptability interplaying with situational strength in career construct theory. The findings revealed that African international students with higher career adaptability perceived more offline social support in the host society associated with a higher quality of life. In addition, greater COVID-19 impact weakened the relationship between career adaptability and perceived offline social support. These findings indicate that perceived offline social support is an important adapting response through which career adaptability affects African international students’ quality of life during the cross-cultural transition, and that the mediating effect of perceived offline social support was diminished when the level of COVID-19 impact on African international students is too high. Understanding how career adaptability assists international students in pursuit of successful adjustment and how the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on international students’ adaptation to the host society are important to provide interventions that can assist international students to adjust themselves better in the host society, especially those severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Declarations

This manuscript has not been published before and is not being considered for publication elsewhere. All authors have contributed to the creation of this manuscript for important intellectual content and read and approved the final manuscript. We declare there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No. 31800928], Youth Fund Project of Humanities and Social Sciences Research of Ministry of Education of China [Grant No. 18YJC740092], Guangdong Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences “13th Five-Year Plan” Planning Co-construction Project [Grant No. GD18XXL04] and Guangzhou Philosophy and Social Sciences Development “ 13th Five-Year Plan” Planning Young Scholar Project of City of Rams [Grant No. 2020GZQN42].

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee at Southern Medical University, China.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all participants in this study. We would like to thank authors for their contribution of this article.

References

- Akkermans J., Richardson J., Kraimer M.L. The Covid-19 crisis as a career shock: Implications for careers and vocational behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2020;119 doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala Y., Bayona J.A., Karaeminogullari A., Perdomo-Ortiz J., Ramos-Mejia M. We are very similar but not really: the moderating role of cultural identification for refugee resettlement of Venezuelans in Colombia. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.569394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender M., van Osch Y., Sleegers W., Ye M. Social support benefits psychological adjustment of international students: evidence from a meta-analysis. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology. 2019;50(7):827–847. doi: 10.1177/0022022119861151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bierwiaczonek K., Waldzus S. Socio-cultural factors as antecedents of cross-cultural adaptation in expatriates, international students, and migrants. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology. 2016;47(6):767–817. doi: 10.1177/0022022116644526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J.L., Dollinger M., Hammer S.J., McIlveen P. Career adaptability and career adaptive behaviors: A qualitative analysis of university students’ participation in extracurricular activities. Australian Journal of Career Development. 2021;30(3):189–198. doi: 10.1177/10384162211067014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campion E.D. The career adaptive refugee: Exploring the structural and personal barriers to refugee resettlement. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2018;105:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho E. Examining boundaries to understand the impact of COVID-19 on vocational behaviors. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2020;119 doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantine M.G., Okazaki S., Utsey S.O. Self-concealment, social self-efficacy, acculturative stress, and depression in African, Asian, and Latin American international college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74(3):230–241. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.3.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran P.G. Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2016;66:4–19. doi: 10.1016/J.JESP.2015.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- English A.S., Zhang Y.B., Tong R. Social support and cultural distance: Sojourners’ experience in China. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2021;80:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ginevra M.C., Di Maggio I., Santilli S., Sgaramella T.M., Nota L., Soresi S. Career adaptability, resilience, and life satisfaction: A mediational analysis in a sample of parents of children with mild intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability. 2017;43(4):473–482. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2017.1293236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y., Liu S., Guo M.J., Li M., Wu M., Chen S.X., et al. Acculturation orientations and Chinese student Sojourners' career adaptability: The roles of career exploration and cultural distance. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2018;104:228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y., Zhuang M., Cai Z., Ding Y., Wang Y., Huang Z., et al. Modeling dynamics in career construction: Reciprocal relationship between future work self and career exploration. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2017;101:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi A. Career adaptability development in adolescence: Multiple predictors and effect on sense of power and life satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2009;74(2):145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.-T., Bentler P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang I.C., Choi L.J. Staying connected during COVID-19: The social and communicative role of an ethnic online community of Chinese international students in South Korea. Multilingua. 2020;39(5):541–552. doi: 10.1515/multi-2020-0097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jannesari M., Sullivan S.E. Career adaptability and the success of self-initiated expatriates in China. Career Development International. 2019;24(4):331–349. doi: 10.1108/cdi-02-2019-0038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q., Yuen M., Horta H. Factors Influencing Life Satisfaction of International Students in Mainland China. International Association for Counselling. 2020:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s10447-020-09409-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai A.Y., Lee L., Wang M.P., Feng Y., Lai T.T., Ho L.M., et al. Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on international university students, related stressors, and coping strategies. Frontriers in Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.584240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Sun H. Migration intentions of Asian and African medical students educated in China: a cross-sectional study. Human Resources for Health. 2019;17(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12960-019-0431-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M., Hirschfeld G., Margraf J. Brief form of the Perceived Social Support Questionnaire (F-SozU K-6): Validation, norms, and cross-cultural measurement invariance in the USA, Germany, Russia, and China. Psychol Assess. 2019;31(5):609–621. doi: 10.1037/pas0000686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M.-P., Wu J.Y.-W., You J., Chang K.-M., Hu W.-H., Xu S. Association between online and offline social support and internet addiction in a representative sample of senior high school students in Taiwan: The mediating role of self-esteem. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;84:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H., Miller C. Trapped in a double bind: chinese overseas student anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Communication. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1775439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggiori C., Johnston C.S., Krings F., Massoudi K., Rossier J. The role of career adaptability and work conditions on general and professional well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2013;83(3):437–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2013.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maggiori C., Rossier J., Savickas M.L. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale–Short Form (CAAS-SF) Journal of Career Assessment. 2015;25(2):312–325. doi: 10.1177/1069072714565856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mesidor J.K., Sly K. Factors That Contribute to the Adjustment of International Students. Journal of International Students. 2016;6:262–282. doi: 10.32674/jis.v6i1.569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R.D., Kelly E.D., Bowling N.A. The Oxford handbook of psychological situations. Oxford University Press; 2020. Situational strength theory; pp. 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education in China. (2019). Statistics of studying in China in 2018. Retrieved from 〈http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/gzdt_gzdt/s5987/201904/t20190412_377692.html〉. (Accessed 12 April ).

- Ng T.K., Wang K.W.C., Chan W. Acculturation and cross-cultural adaptation: The moderating role of social support. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2017;59:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2018). Internationalisation for education. Retrieved from 〈https://gpseducation.oecd.org/IndicatorExplorer?plotter=h5&query=28&indicators=C014*C071*C028*A226*A231*A232*A233*C059*C062*C065*C068*C072*C073*C119*C120*C121*C122*C123*C124*C125*C126*C127*C138*C156*C157*C158*C159*C160*C161*C162*C163*C164*C166*B047〉. 〉. (Accessed 1 June 2020).

- Presbitero A., Quita C. Expatriate career intentions: Links to career adaptability and cultural intelligence. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2017;98:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2016.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Procidano, M.E., & Smith, W.W. (1997). Assessing perceived social support, 93–106. Retrieved from 〈 10.1007/978-1-4899-1843-7_5〉. [DOI]

- Rudolph C.W., Lavigne K.N., Zacher H. Career adaptability: A meta-analysis of relationships with measures of adaptivity, adapting responses, and adaptation results. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2017;98:17–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2016.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo M. In: Methodological issues in management research: Advances, challenges, and the way ahead. Subudhi R.N., Mishra S., editors. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2019. Structural equation modeling: threshold criteria for assessing model fit; pp. 269–276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saegert, S., & Carpiano, R.M. (2017). Social support and social capital: A theoretical synthesis using community psychology and community sociology approaches. 295–314. Retrieved from 〈 10.1037/14953-014〉. [DOI]

- Savickas M.L. In: Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work. 2nd ed. Lent R.W., Brown S.D., editors. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2013. Career construction theory and practice; pp. 147–183. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M.L. (2020). Career construction theory and practice. Career developmentand counseling: putting theory and research to work (2nd ed.). (pp. 147–183).

- Savickas M.L., Porfeli E.J. Career adapt-abilities scale: construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2012;80(3):661–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shu F., Ahmed S.F., Pickett M.L., Ayman R., McAbee S.T. Social support perceptions, network characteristics, and international student adjustment. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2020;74:136–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siedlecki K.L., Salthouse T.A., Oishi S., Jeswani S. The relationship between social support and subjective well-being across age. Social Indicators Research. 2014;117(2):561–576. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0361-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soresi S., Nota L., Ferrari L. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale-Italian Form: Psychometric properties and relationships to breadth of interests, quality of life, and perceived barriers. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2012;80(3):705–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller S.A., Fitzsimons G.J., Lynch J.G., McClelland G.H. Spotlights, floodlights, and the magic number zero: simple effects tests in moderated regression. Journal of Marketing Research. 2013;50(2):277–288. doi: 10.1509/JMR.12.0420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taber B.J. In: Handbook of innovative career counselling. Maree J.G., editor. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2019. Career counselling interventions to enhance career adaptabilities for sustainable employment; pp. 103–115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The WHOQOL Group Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28(3):551–558. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trougakos J.P., Chawla N., McCarthy J.M. Working in a pandemic: Exploring the impact of COVID-19 health anxiety on work, family, and health outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2020;105(11):1234–1245. doi: 10.1037/apl0000739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull M.T., Edmonds K.A., Scamaldo K.M., Richmond J.R., Rose J.P., Gratz K.L. Psychological outcomes associated with stay-at-home orders and the perceived impact of COVID-19 on daily life. Psychiatry Research. 2020;289 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanaviciute I., Udayar S., Rossier J. Career adaptability and employee well-being over a two-year period: Investigating cross-lagged effects and their boundary conditions. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2019;111:74–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2018.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Utz S., Breuer J. The relationship between use of social network sites, online social support, and well-being. Journal of Media Psychology. 2017;29(3):115–125. doi: 10.1027/a000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E.S., Wang M.C. Social support and social interaction ties on internet addiction: Integrating online and offline contexts. Cyberpsychology Behavior, and Social Networking. 2013;16(11):843–849. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B., Chen X., Li S., Liu Y., Jacques-Tiura A.J., Yan H. Acculturative stress and influential factors among international students in China: a structural dynamic perspective. PLoS One. 2014;9(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]