Abstract

Purpose/Background:

Therapeutic hypothermia (TH) is the standard treatment for hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE). We surveyed parents of infants treated with TH about their experiences of communication and parental involvement in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU).

Methods/Approach:

A 29-question anonymous survey was posted on a parent support website (https://www.hopeforhie.org) and sent to members via e-mail. Responses from open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results:

165 respondents completed the survey and 108 (66%) infants were treated with TH. 79 (48%) respondents were dissatisfied/neutral regarding the quality of communication in the NICU, whereas 127 (77%) were satisfied/greatly satisfied with the quality of parental involvement in the NICU.

6 themes were identified: 1) Setting for communication: Parents preferred face to face meetings with clinicians. 2) Content and clarity of language: Parents valued clear language (use of layman’s terms) and being explicitly told the medical diagnosis of HIE. 3) Immediate and Longitudinal Emotional Support: Parents required support from clinicians to process the trauma of the birth experience and hypothermia treatment. 4) Clinician time and scheduling: Parents valued the ability to join rounds and other major conversations about infant care. 5) Valuing the Parent Role: Parents desired being actively involved in rounds, care times and decision making. 6) Physical Presence and Touch: Parents valued being physically present and touching their baby; this presence was limited by COVID-related restrictions.

Conclusion:

We highlight stakeholder views on parent involvement and parent-clinician communication in the NICU and note significant overlap with principles of Trauma Informed Care: safety (physical and psychological), trustworthiness and transparency, peer support, collaboration and mutuality, and empowerment, voice and choice. We propose that a greater understanding and implementation of these principles may allow the medical team to more effectively communicate with and involve parents in the care of infants with HIE in the NICU.

Keywords: trauma informed care, therapeutic hypothermia, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, communication

Introduction:

While therapeutic hypothermia (TH) has become the standard of care for treating infants with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE)1 and has been shown to improve outcomes2–5, the uncertainty of being in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) and the process of treating infants with TH can be traumatic for families6,7. Being separated from their infant after birth6, not being able to hold or touch their infant8, not being provided with complete medical information about their infant9, not being able to fully play the role of the infant’s parent, and not being supported emotionally throughout their experience are all factors that contribute to the trauma experience for parents.

Employing a model of trauma informed care (TIC), first widely implemented by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (SAMHSA)10, with parents in the NICU may be a first step to ameliorating the effects of this trauma11. This approach relies on the realization of the widespread impact of trauma, on the recognition of signs of trauma and the development of policies that actively resist re-traumatization10. TIC involves six fundamental principles: 1. safety (both physical and psychological), 2. Trustworthiness and transparency, 3. peer support, 4. collaboration and mutuality, 5. empowerment, voice and choice and lastly 6. cultural, historical and gender issues. Good communication with the NICU team12 and creating the opportunity for parents to be actively involved in caring for the infant while in the NICU are crucial to avoid exacerbating the trauma that families of infants with HIE already experience11. Providers in the NICU have the opportunity to positively or negatively influence the trauma trajectory of families of children with HIE by communicating well and by involving parents. We aimed to assess the parental experience of HIE care through a survey, with particular focus on the experience of communication and parental involvement.

Methods:

Survey Development:

A 29-question survey was designed (Appendix A) by the authors, who represent a multidisciplinary team of two parents with children affected by HIE and two Neonatal Neurologists. Questions included the caregiver’s relation to the infant, the age of the parent at the time of the child’s birth, the child’s year of birth, and a race/ethnicity question. We asked if the parent/caregiver was aware of the cause of their child’s HIE and if treatment with TH had occurred. Additional multiple-choice questions assessed the severity of the child’s symptoms both in the NICU and after discharge. We then asked parents/caregivers to rate the quality of the communication in the NICU and how involved they felt in their newborn’s care on a one through five Likert scale (1= very dissatisfied, 5=greatly satisfied). We followed this with open-ended questions about what worked best for effective communication and parental involvement in the infant’s care, and about what could be improved. Detailed personal demographic information was not collected from respondents in order to protect anonymity.

Survey Implementation:

A link to the anonymous REDCap survey was posted on the Hope for HIE website (https://www.hopeforhie.org) by author B.P., and was also e-mailed to Hope for HIE members. The survey was available only in English. The survey link was active for a period of two weeks starting September 11, 2020. The Institutional Review Board at Maine Medical Center approved the study as Exempt Category 2(i).

Study Participants:

Study participants included parents and caregivers of children with a diagnosis of HIE. We included those who were treated with TH and those who were not.

Analysis:

Multiple choice survey responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics. We used thematic analysis to identify common sentiments expressed by parents in the open-ended survey responses about what made communication and parent involvement effective during HIE, and what could be improved. As Braun and Clarke describe, thematic analysis “is a method for identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data” and is an established method used for qualitative data analysis13. We used an inductive approach to identify themes present in the survey data, meaning “the themes identified are strongly linked to the data themselves”, and were not pre-conceived by the study authors prior to examining the data13. Specifically, we had two authors independently review the open-ended survey response data and identify patterns and themes in the responses; they then came together to discuss these identified patterns, and developed a coding system to reflect common themes present. These authors then separately re-examined all open-ended survey responses and coded the responses as representing any of the six identified themes. The authors met to discuss their coding results and resolve any differences in coding. As themes were identified, we noted overlap between these themes and the existing framework of TIC. It should be noted that the goal of this study was not to measure the exact prevalence of each theme in the data, but to identify the themes present.

Results:

Of the 167 individuals who clicked on the link for the survey, 165 (99%) completed the survey. At the time the survey was sent, there were 5,582 members of Hope for HIE. The majority of respondents were mothers (96%), who identified as White (85%). Two-thirds of the infants were treated with therapeutic hypothermia and clinical outcomes varied from typical development, to a cerebral palsy diagnosis for about half of survivors, to demise from HIE for 16 (10%) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Demographic Data

| Question | Response |

|---|---|

| What role do you play in life of child with HIE? | |

| Mother | 158 (96%) |

| Father (3), Grandparent (3), Aunt (1) | 7 (4%) |

|

| |

| Mother’s age at time of child’s birth (n=158) | |

| < 18 years | 3 (2%) |

| 19–25 years | 23 (14%) |

| 26–34 years | 96 (61%) |

| 35–44 years | 36 (23%) |

|

| |

| Year of child’s birth (n=164) | |

| <=2010 | 17 (10%) |

| 2011–2015 | 34 (21%) |

| 2016 to present | 113 (69%) |

|

| |

| Treated with hypothermia (n=164) | 108 (66%) |

|

| |

| Was an MRI brain done in NICU (n=164) | 157 (96%) |

|

| |

| Was there brain injury on MRI (n=157) | 123 (78%) |

|

| |

| Clinical outcome for your child (n=162) | |

| Typical | 36 (22%) |

| Mild | 28 (17%) |

| Moderate | 40 (25%) |

| Severe | 42 (26%) |

| Loss from HIE | 16 (10%) |

|

| |

| When was the prognosis discussed with you? | |

| Following birth | 52 (32%) |

| During TH | 48 (29%) |

| After the MRI | 106 (64%) |

| Prior to discharge | 52 (32%) |

| Don’t know | 17 (10%) |

| Other | 14 (8%) |

|

| |

| Quality of communication in the NICU | |

| 1= very dissatisfied | 13 (8%) |

| 2 | 18 (11%) |

| 3= neutral | 48 (29%) |

| 4 | 49 (30%) |

| 5= greatly satisfied | 35 (22%) |

|

| |

| Quality of involvement in care of baby | |

| 1= very dissatisfied | 11 (7%) |

| 2 | 7 (4%) |

| 3= neutral | 20 (12%) |

| 4 | 39 (24%) |

| 5= greatly satisfied | 88 (53%) |

Just under half of respondents were dissatisfied or neutral regarding the quality of the communication they experienced in the NICU (Table 1). However, more than three-quarters of parents were satisfied or greatly satisfied with the quality of their involvement in the care of their baby while in the NICU (Table 1). In the numerous written responses to open-ended questions, six major themes were identified as being important for communication and parent involvement in the NICU: setting for communication, content and clarity of language, immediate and longitudinal emotional support, clinician time and scheduling, valuing the parent role, and physical presence and touch.

Theme 1: Setting for Communication

Setting was defined as the physical or virtual location where communication with the medical team occurred. Parents overwhelmingly reported that they wanted to have communication with the medical team occur face to face, in person, when possible (Table 2). Though parents often found rounds informative, parents also commented that information was communicated most effectively during “one on one meetings.” Parents reported that communication over the phone was helpful and strongly desired when they were not able to be physically present (Table 2). Families often expressed geographic, financial and care obligations for other children as barriers to being present for in person communication. Several mothers also explicitly commented on deficiencies surrounding communication prior to the mother being transferred to the hospital where the baby was receiving care. Parents also commented on the importance of virtual communication during the COVID-19 pandemic, as their ability to be present in person was often limited by COVID related visitation restrictions. One parent commented that “being able to attend ward rounds remotely” would improve communication since they “couldn’t attend in person due to COVID.”

Table 2:

Quotes describing how the setting for communication and language impacted parent experience of communication

| Sub-themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| In person communication | “Listening to rounds” and “In person private talks” were ways information was most effectively communicated |

| Virtual communication | “The doctors called us if we weren’t there for rounds. I appreciated that.” |

| Written communication | “Having things in writing (flyers, leaflets, even just a sketched summary of the MRI, etc.) would have been very helpful… It was very hard to keep track of things we were told, information would slip out of my brain as soon as it was said, and something physical to refer to would have helped a lot.” |

| Naming the diagnosis | “Being given the name of the diagnosis” and “Actually telling me she had HIE.” would make communication more effective |

| Information on prognosis | “Some sense of the complexity/uncertainty of what was going on would have really helped us at that time…No one directly told us.” |

| Unified message | “We felt at the time that we were being told conflicting things every time we spoke to a doctor and that we were being purposely kept in the dark, it really damaged our trust in them.” |

Theme 2: Content and Clarity of Language

This theme was defined by the format (verbal versus written), the content of the language used by the medical team, and the type of words (medical versus layman’s terms) used when communicating with families. Parents expressed a preference for receiving both verbal and written information from providers with both formats contributing to their ability to understand their infant’s medical care (Table 2). Parents expressed the desire to be told the medical term for their infant’s diagnosis, specifically referencing “Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy” or “HIE” as terms that were often not disclosed except in discharge paperwork or accidentally discovered online. As one parent explained, “No one really told us anything. We did not even know our daughter had a diagnosis of HIE. We found out when we read our discharge papers.” Parents wanted to have the medical diagnosis named, but to have this diagnosis explained using non-medical terminology. As one parent wrote, “Doctors talked in a manner that was hard to understand and decipher unless you had a medical background. I would have loved for someone to put everything into layman’s terms.”

Theme 3: Immediate and Longitudinal Emotional Support

Emotional support was defined as providers showing compassion towards families, providing multidisciplinary care to infants and their families and connecting families to resources such as peer support groups (Table 3). Many families commented on the traumatic nature of their birth experience, explaining “we were still in shock and trying to process,” and how this fact made emotional support especially crucial. Multiple parents stated that they wished they had been introduced to peer support groups for infants with HIE by their NICU team. Parents also expressed the desire for doctors and nurses to show compassion. One parent explained that “More compassion for the fact that we were in shock by the outcome of birth, and understanding that we were in a fragile state” would have been helpful when providers were communicating with them. Parents also remarked on the positive impact that multidisciplinary care teams had on decreasing parental stress and helping parents feel prepared to take care of their infant, especially when preparing for discharge. For infants who did not survive, parents felt involving the palliative care team was key for providing support and promoting clear communication. One parent wrote, “Knowing the severity of the injury at the beginning and being given an opportunity to let him go as his organ systems failed [would improve communication]. Having a palliative team earlier could’ve changed everything.”

Table 3:

Quotes describing the impact of emotional support on parent experience

| Sub-themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Compassion | “I really wish that our NICU team were more aware of how to not only take care of the child but also the family.” |

| Peer Support, family support and general emotional support | “After a traumatic birth, the entire family is traumatized, you find yourself thrust into an unknown world and your baby is taken away to be cared for by other people in a place (NICU) where you don’t belong or actually even feel wanted. PTSD is real and I think emotional support for families is a must. Not only would it make the initial trauma more bearable, it could help avoid the devastating long term effects on the parents and siblings.” |

| Multidisciplinary Team | “The family support member of staff was a key mediator between consultants and ourselves and prompted key/challenging conversations.” |

| Support surrounding discharge | “I felt like we left the NICU and were left to our own devices. The future was up to us to navigate with almost zero road map.” |

Theme 4: Clinician time and scheduling

This theme encompassed survey responses that referenced how time either allowed for or limited communication and parent involvement in the NICU. Providers in the NICU were viewed positively when adequate time for questions was made on rounds or when time was created for regular and repeated check-ins with families. One parent expressed that “doctors having more time to explain HIE and answer questions” would improve communication, and explained that “Trying to hurry along NICU visits made us feel very alone.” Another parent wrote that “longer talks with neurology” would have made communication better. Providing parents with a schedule was also perceived to facilitate parental presence and therefore parent involvement for both medical rounds and care times. One parent wrote that “knowing what time ward rounds was going to be” would have been helpful; “sometimes I waited half the day especially at weekends, missing meals, etc in order to try to be present for rounds”. Another parent commented that “If I knew what time morning rounds were actually taking place,” that would have improved communication—“It was a guessing game…. And each day was a different time.”

Theme 5: Valuing the Parent Role

This theme was defined as recognizing and respecting parents as important members of the care team. Parents expressed a strong desire to be involved in cares (diaper changes, baths, temperature checks, etc). Parents often felt they did not know what they were and were not allowed to do, and expressed repeatedly throughout this survey that they wanted to be encouraged and taught by bedside nurses to be involved in any way they could (Table 4). Parents also expressed the desire to have some sense of normalcy brought to their infant’s situation, by being able to do normal parent activities like dressing the infant or reading to the infant. Communication with the medical team was also crucial for parents to feel involved in their infant’s care. One parent explained that if they were not present for rounds, “I wouldn’t get a say in what happened.” When present for rounds, parents also expressed the desire to have the team actively involve them, instead of just hold rounds in front of them. One parent stated, “I was kind of ignored by doctors when they were on their rounds, it was a teaching hospital and I feel like they should have been showing the new ones [trainee physicians] that communication with the family is important.”

Table 4:

Quotes illustrating the importance of the parent role and physical presence

| Sub-themes: | Quotes: |

|---|---|

| Physical presence and touch | “Just being able to be at her bedside, touch her, and let her know her parents were there.” as an effective way to involve parents |

| Involvement in Cares | “Nurses inviting you to take on the cares, at first the cot side felt like a real barrier, and I felt like I needed to ask permission to hold my child.” as a way to improve parent involvement |

| Sense of Normalcy | “Even amongst the terrible news, shock of medical things, and being under a microscope, I wanted to be a parent. I wanted to participate and understand all things medical, but I also wanted to be a first time mom. I wanted to hold my child, I wanted to have hope against odds, I wanted to love and care for my baby… I needed the space to be a parent, even amongst the 24/7 bright lights, noise and confusion.” |

| Communication with the medical team | “I really wish there had been more information, more support, more openness and more willingness to let us be involved, especially as ultimately she passed away so most of the memories we have are just sitting next to her and waiting for someone to tell us what was going on.” |

| Shared decision making | “Allow parents to have a say in their child’s treatment options.” |

Theme 6: Physical Presence and Touch

There were many responses that discussed spending time physically near the infant, being able to stay overnight with the infant, having alone time with the infant, and being able to touch the infant through hand hugs and holding when able. Parents expressed that “being able to physically be there” was key to being involved, even if they were not yet able to hold the infant. Holding as soon as possible was strongly desired. COVID related visitation restrictions made it more difficult for families to be physically present with their infants, which negatively impacted their ability to be involved in the infant’s care. One mother explained, “Because of COVID, after I was discharged only one person per day was allowed in the NICU which meant either I had to go across the hospital and 5 floors up to get to my baby alone or I had to sit at home alone while my husband went up.”

Discussion:

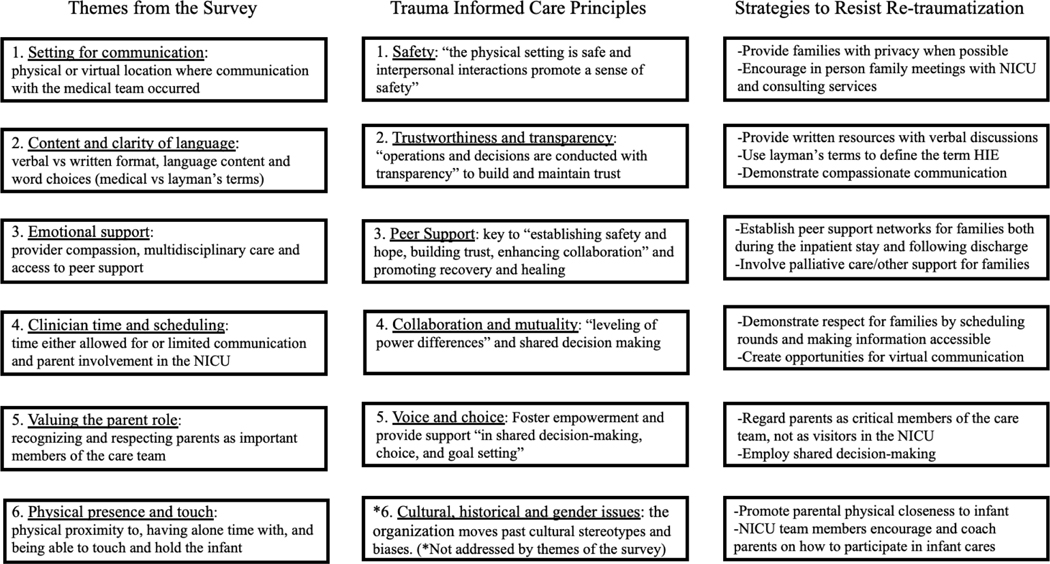

Here, we highlight stakeholder views on parent involvement and parent-clinician communication in the NICU. Our results suggest modifiable behaviors for clinicians that can help parents navigate the NICU experience. We identified six themes characterizing how to improve communication and parent involvement. These themes relate directly to five of the six principles of TIC (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Summary of themes from the survey, trauma informed care principles and strategies to resist re-traumatization

A TIC approach begins with the principle of safety, characterized by both physical and psychological safety10. Both the physical setting and interpersonal interactions should promote a sense of safety, and safety should be defined by those being served10. Existing literature suggests that the NICU team should provide “supportive care that enhances the client’s or patient’s feelings of safety and security, to prevent their re-traumatization in a current situation that may potentially overwhelm their coping skills”11. Sanders and Hall state that to promote a sense of safety for families in the NICU, several things should be provided: privacy for families, providers should respect the parents, and providers should communicate in a caring and empathic manner. It has also been well established that physical separation from the infant is a source of stress6,8 and that physical proximity or holding can ameliorate that stress14. These ways of promoting safety relate directly to themes identified in our study. Specifically, parents in our study felt that being physically present with their infant promoted a sense of safety, as did having alone time with their infant and having adequate time to be with their infant. In person, private communication with doctors promoted this as well. Our findings support existing literature demonstrating that NICU parents are at risk of poor psychological well-being15,16; promoting psychological safety can mitigate this distress.

The second principle of TIC is trustworthiness and transparency. To provide TIC, “organizational operations and decisions are conducted with transparency with the goal of building and maintaining trust with clients and families”10. In the NICU, this means that communication “free of medical jargon” occurs with families frequently, that parents’ presence on rounds is encouraged, that parents have access to all of their baby’s medical information, and that parents’ “concerns and questions are respected”11. These methods of promoting trustworthiness and transparency for NICU families again relate directly to what families in our study called for: clear, direct language in laymen’s terms, an understanding of and access to their infant’s medical information including the name of their infant’s diagnosis, honest information about prognosis when available, and the opportunity to have their questions answered. Other studies have highlighted the importance of communicating without medical jargon to families of infants with HIE9,12, however this project uniquely frames the use of medical jargon as a way of re-traumatizing parents by making crucial information unavailable to them. These findings support the implementation of family-centered and family-integrated models of care for infants with HIE17–20.

The third principle of TIC is peer support. One of the key ways of providing emotional support, a theme identified many times in our survey results, is to provide peer support for families. Peer support is noted by SAMHSA to be a “key vehicle for establishing safety and hope, building trust, enhancing collaboration and utilizing their [peers’] stories and lived experience to promote recovery and healing.” Peers are defined as those who have lived experiences of trauma or who are trauma survivors10. Sanders and Hall state that peer support should be offered to every NICU family within 72 hours of admission, and acknowledge that there are multiple ways that peer support can be provided: “one-on-one, in a group setting, by telephone or internet.” Coughlin suggests that institutionalizing peer support resources in the NICU improves both maternal and infant well-being21. Parents in our study felt strongly that peer support either did or would have greatly helped them cope during their time in the NICU and after being discharged.

The next principle of TIC as defined by SAMHSA is collaboration and mutuality. This principle is defined by “partnering and the leveling of power differences between staff and clients,” and by recognizing that “healing happens in relationships and in the meaningful sharing of power and decision-making.”10 In the NICU, this means that “parents are partners with the NICU team”11 and not visitors22 a sentiment particularly relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic23. It also means that “parents are involved in the care of their baby as early and as often as possible” and that nurses “take the role of mentor and coach to parents,” not only allowing, but teaching and encouraging parents to care for their baby11. “Shared decision making for baby’s care plans” should also occur11 between parents and the medical team. This principle of collaboration and mutuality relates directly to valuing the parent role and clinician time and scheduling, themes identified in our study. The medical team must value the parent role for shared decision making to take place, and nurses must encourage and teach parents how to participate in cares in order for parents to fully collaborate with the medical team in caring for their infant.

The last TIC principle that relates to the themes identified in our study is empowerment, voice and choice. This principle emphasizes the importance of “shared decision-making, choice, and goal setting to determine the plan of action they [families] need to heal and move forward,”10 ideas already touched upon by other principles of TIC. This principle is built upon the belief that individuals are resilient, and have the ability to “heal and promote recovery from trauma.”10 In the NICU, this means that parents’ resilience should be fostered by providing emotional support, by supporting parents in being active caregivers for their infant, and by supporting parents’ being physically present on rounds and at the bedside11. This principle relates strongly to our themes of valuing the parent role, physical presence, and emotional support, as these themes are all crucial in promoting resilience and lessening the deleterious effects that HIE trauma can have on the entire family unit.

The goal of providing TIC for HIE infants and families is to ameliorate the effects of the trauma already experienced by the parent/infant dyad or triad. The results of this study support a TIC approach to caring for these families in the NICU. A strength of this study is the survey design which utilized many open-ended questions to maximize respondents’ ability to share information. While posting this survey on the Hope for HIE website is considered a strength as it provided access to a large number of families with children diagnosed with HIE, there is also the possibility of inherent selection bias as parents who had already sought out peer support would be more likely to respond. It must also be acknowledged that the responses reflect the experience of mothers, who predominantly identified as White, and therefore the results may not be as applicable to fathers or caregivers of other races. Many parents in our cohort had a child with moderate to severe brain injury and/or lost a child to HIE; responses may underrepresent the experiences of parents whose children experienced milder outcomes.

Despite these limitations, our findings, taken directly from stakeholders, highlight the importance of a TIC approach to care in HIE. Our identified themes illustrate the importance of providing TIC to these families, and may have implications on the ways in which NICUs approach caring for these infants and their parents. Future directions include surveying a larger and more diverse population of caregivers of infants with HIE, educating NICU providers and staff on ways to provide TIC, and further partnership between providers and parent-led peer support organizations to collaborate and provide the best possible care to families.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Disclosures: Dr. Craig was supported by grant 1P20GM139745-01 from the National Institutes of Health for the Center of Biomedical Research Excellence in Acute Care Research and Rural Disparities. Dr. Lemmon receives salary support from the National Institute of Health (K23NS116453).

Abbreviations:

- HIE

hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy

- NICU

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- TH

therapeutic hypothermia

- TIC

trauma informed care

References:

- 1.Jacobs SE, Berg M, Hunt R, Tarnow-Mordi WO, Inder TE, Davis PG. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(1):CD003311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(15):1574–1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shankaran S, Pappas A, McDonald SA, et al. Childhood outcomes after hypothermia for neonatal encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(22):2085–2092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azzopardi DV, Strohm B, Edwards AD, et al. Moderate hypothermia to treat perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1349–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azzopardi D, Strohm B, Marlow N, et al. Effects of hypothermia for perinatal asphyxia on childhood outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):140–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig AK, James C, Bainter J, Evans S, Gerwin R. Parental perceptions of neonatal therapeutic hypothermia; emotional and healing experiences. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018:1–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemmon ME, Donohue PK, Parkinson C, Northington FJ, Boss RD. Parent Experience of Neonatal Encephalopathy. J Child Neurol. 2017;32(3):286–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Backe P, Hjelte B, Hellstrom Westas L, Agren J, Thernstrom Blomqvist Y. When all I wanted was to hold my baby-The experiences of parents of infants who received therapeutic hypothermia. Acta Paediatr. 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig AK, Gerwin R, Bainter J, Evans S, James C. Exploring Parent Experience of Communication About Therapeutic Hypothermia in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Adv Neonatal Care. 2018;18(2):136–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Administration SAaMHS. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach; 2014;Report No.: HHS Publication No. (SMA):14–4884 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders MR, Hall SL. Trauma-informed care in the newborn intensive care unit: promoting safety, security and connectedness. J Perinatol. 2018;38(1):3–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemmon ME, Donohue PK, Parkinson C, Northington FJ, Boss RD. Communication Challenges in Neonatal Encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun VC V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig A, Deerwester K, Fox L, Jacobs J, Evans S. Maternal holding during therapeutic hypothermia for infants with neonatal encephalopathy is feasible. Acta Paediatr. 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemmon M, Glass H, Shellhaas RA, et al. Parent experience of caring for neonates with seizures. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2020;105(6):634–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franck LS, Shellhaas RA, Lemmon M, et al. Associations between Infant and Parent Characteristics and Measures of Family Well-Being in Neonates with Seizures: A Cohort Study. J Pediatr. 2020;221:64–71 e64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franck LS, O’Brien K. The evolution of family-centered care: From supporting parent-delivered interventions to a model of family integrated care. Birth Defects Res. 2019;111(15):1044–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien K, Robson K, Bracht M, et al. Effectiveness of Family Integrated Care in neonatal intensive care units on infant and parent outcomes: a multicentre, multinational, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(4):245–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sigurdson K, Profit J, Dhurjati R, et al. Former NICU Families Describe Gaps in Family-Centered Care. Qual Health Res. 2020;30(12):1861–1875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franck LS, Waddington C, O’Brien K. Family Integrated Care for Preterm Infants. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2020;32(2):149–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coughlin ME. Trauma-Informed Care in the NICU; Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines for Neonatal Clinicians. 2017:215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffin T. A family-centered “visitation” policy in the neonatal intensive care unit that welcomes parents as partners. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2013;27(2):160–165; quiz 166–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemmon ME, Chapman I, Malcolm W, et al. Beyond the First Wave: Consequences of COVID-19 on High-Risk Infants and Families. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37(12):1283–1288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.