Abstract

Purpose of Review

The role of the meniscus in preserving the biomechanical function of the knee joint has been clearly defined. The hypothesis that meniscus root integrity is a prerequisite for meniscus function is supported by the development of progressive knee osteoarthritis (OA) following meniscus root tears (MRTs) treated either non-operatively or with meniscectomy. Consequently, there has been a resurgence of interest in the diagnosis and treatment of MRTs. This review examines the contemporary literature surrounding the natural history, clinical presentation, evaluation, preferred surgical repair technique and outcomes.

Recent Findings

Surgeons must have a high index of suspicion in order to diagnose a MRT because of the nonspecific clinical presentation and difficult visualization on imaging. Compared with medial MRTs that commonly occur in middle age/older patients, lateral meniscus root injuries tend to occur in younger males with lower BMIs, less cartilage degeneration, and with concomitant ligament injury. Subchondral insufficiency fractures of the knee have been found to be associated with both MRTs and following arthroscopic procedures. Meniscus root repair has demonstrated good outcomes, and acute injuries with intact cartilage should be repaired. Cartilage degeneration, BMI, and malalignment are important considerations when choosing surgical candidates. Meniscus centralization has emerged as a viable adjunct strategy aimed at correcting meniscus extrusion.

Summary

Meniscus root repair results in a decreased rate of OA and arthroplasty and is economically advantageous when compared with nonoperative treatment and partial meniscectomy. The transtibial pull-through technique with the addition of centralization for the medial meniscus is associated with encouraging early results.

Keywords: Knee cartilage, Meniscus root tear, Meniscus extrusion, Meniscus root repair, Transtibial pull-through, Subchondral insufficiency fractures of the knee

Introduction

Meniscus tears are a common orthopedic injury, comprising 12–14% of orthopedic knee presentations with an annual incidence of 60–70 cases per 100,000 persons [1–3]. Knowledge of the functional and biomechanical role of the meniscus, and the anterior and posterior roots specifically, has evolved in the past few decades. Meniscus root tears (MRTs), defined as a complete radial tear within 1 cm of the tibial attachment point or a bony/soft tissue avulsion has grown in interest with mounting data showing poor native outcomes equivalent to subtotal meniscectomy [4, 5]. Lateral MRTs are more commonly acute, high impact injuries with concomitant ligamentous injury, while medial MRTs are degenerative in nature in an older population [6•]. These tears may be clinically difficult as many go undiagnosed at initial presentation and are missed on conventional imaging [7].

Meniscus extrusion is increasingly being discussed in recent root tear literature and is defined as the meniscus displacement beyond the border of the tibial plateau on MRI [8]. Whether meniscus extrusion precedes root tear or is a consequence of the tear itself is unclear; however, the downstream impact including increased contact pressures of the tibiofemoral joint surface, rapid articular cartilage damage, and severe osteoarthritis (OA) development correlated with degree of extrusion is now well understood [8–12]. Additionally, the etiology of subchondral insufficiency fracture (SIFK), which is occasionally still misrepresented as the term spontaneous osteonecrosis (SONK) on imaging, is another pathology more recently attributed to root tears. These have shown to be particularly deleterious, with studies citing one-third to one-half of patients failing nonoperative treatment with conversion to arthroplasty [13, 14•].

Historically, MRTs were treated with partial or total meniscectomy. Consistent evidence showing degenerative changes and poor patient outcomes following meniscectomy has now shifted the focus to joint preservation and anatomic restoration of the meniscus root via meniscus root repair [15]. Encouraging results showing restoration of peak contact pressures to near native state, improved results in patient reported outcomes and OA development, and decreased overall healthcare costs are reasons root repair may be preferrable in certain patients [16, 17•, 18•, 19•, 20•]. Additionally, root repair augmented with a contemporary centralization technique to anchor the extruded meniscus back to the surface of the tibial plateau is an emphasis of current research [21, 22]. The purpose of this review is to document the natural history, clinical presentation and evaluation, treatment options, and MRT repair outcomes in light of the most recent literature.

Anatomy and Biomechanics

Form and Function

The medial and lateral menisci are crescent shaped wedges of fibrocartilage that cover one-half to two-thirds of the tibial plateau. The primary purpose of these structures is load transmission across the tibiofemoral joint, thereby decreasing impact on surrounding articular cartilage and preserving the joint over time [23]. The medial and lateral meniscus roots are responsible for meniscus anchorage to the tibial plateau anteriorly and posteriorly. These attachments have an important biomechanical function in converting axial loads to circumferential hoop stresses, preventing meniscus extrusion, and maintaining knee kinematics [4, 24].

Meniscus Roots

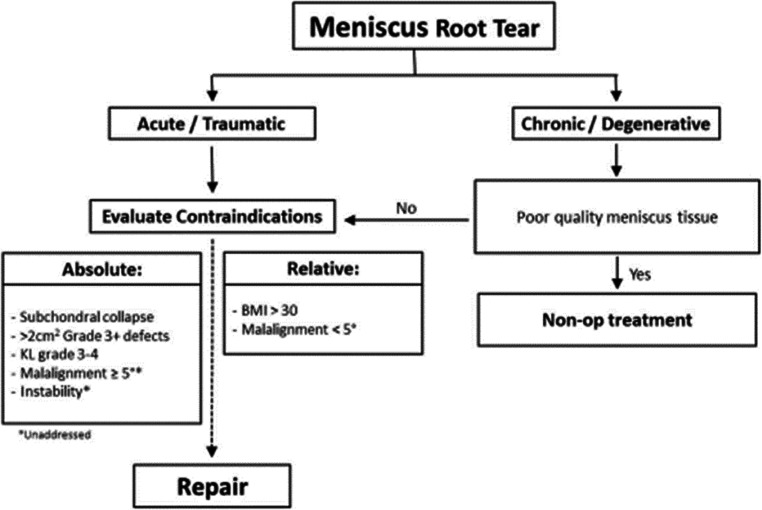

The anatomy of the meniscus roots is well described, with each of the four root attachments varying in native strength and attachment footprint (Fig. 1). The anterior medial (AM), posterior medial (PM), and posterior lateral (PL) roots contain both a central bundle of fibers as well as supplemental attaching fibers. The anterior lateral (AL) root interlinks with the ACL by overlapping the ligament itself and running beneath its insertion point on the tibia [25]. It is uniform throughout, lacking supplemental attaching fibers [26].

Fig. 1.

Distances to meniscus root attachments are well described in cadaveric studies. Meniscus root anatomy is important in successfully reducing menisci to anatomic position. Abbreviations: MPRA: Medial posterior root attachment, LPRA: Lateral posterior root attachment, LARA: Lateral anterior root attachment, MARA: Medial anterior root attachment, ACL: Anterior cruciate ligament, TT: Tibial tubercle, MTE: Medial tibial eminence, LTE: Lateral tibial eminence, SWFs: Shiny White fibers of the posterior medial meniscus root, PCL: Posterior cruciate ligament. Reproduced with permission from: LaPrade RF, Floyd ER, Carlson GB, Moatshe G, Chahla J, Monson JK. Meniscal root tears: Solving the silent epidemic. J Arthrosc Surg Sports Med 2021;2 [1]:47-57 [12]

Anterior Lateral (AL)

The tibial attachment area of the AL root is 140.7 mm with the ACL insertion area 218.4 mm. LaPrade et al. has shown an average overlap of 88.9 mm between the ACL and AL root. Simply, the ACL tibial insertion site is approximately 63.2% AL root and 40.7% ACL [25]. This association is relevant during tibial tunnel reaming of ACL reconstruction as iatrogenic injury to the root may be unavoidable [4, 27].

Anterior Medial (AM)

The AM root is fan shaped and sits 27.5 mm anterior to the apex of the medial tibial eminence (MTE) [25], with supplemental fibers that contribute 28.4% to native root strength [27]. It is the largest and strongest footprint of all the root attachments. Anatomic awareness of this location is important during intramedullary tibial nailing [28].

Posterior Lateral (PL)

The PL meniscus root lies 12.7 mm to the nearest point of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) and 5.3 mm posteromedial to the apex of the lateral tibial eminence (LTE) [25]. Uniquely, the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus has connections to the intercondylar area of the femur via the meniscofemoral ligaments (MFLs). These additional attachments have been reported to decrease contact pressure and alleviate extrusion, at least in part, during isolated PL root tears [29].

Posterior Medial (PM)

The horn of the PM root has an expansion of Shiny White Fibers (SWFs) that are an important visible landmark during PCL reconstruction [30]. Current literature reports an attachment area of 30.4 mm after excluding the transverse SWF [24, 31]. Intraoperatively, one can use the MTE apex as a primary landmark with distances to the most superior edge of the PCL and medial tibial plateau articular cartilage inflection point as secondary landmarks in ensuring anatomic tunnel placement during repair [31].

Equivalence to Meniscectomy and Importance of Biomechanical Repair

Meniscus root injuries result in increased peak tibiofemoral contact pressure, rapid articular cartilage deterioration, and risk of OA development [15]. A landmark paper in 2008 by Allaire et al. revealed that posterior medial MRTs are equivalent to a total medial meniscectomy in the resulting biomechanical function of the knee [16]. Specifically, complete posterior medial MRTs increased peak contact pressures by 25% [16]. Similarly, an increase in lateral peak contact pressure by 50% after lateral root tear was reported by Schillhammer et al. [32]. Multiple studies report biomechanical restoration to native peak contact pressures after repair [16, 32].

Articular Cartilage

Articular cartilage is composed of type II collagen fibers and has a highly organized structure [33]. Damage to joint articular cartilage during meniscus root injury is not uncommon, with risk for injury during acute lateral root tears higher than the degenerative medial root tear counterpart [6•]. The avascular nature of articular cartilage limits healing potential, with restorative techniques to address the deleterious effects of chondral injury an active area of research [34–36]. Additionally, loss of hoop stresses secondary to root tear itself result in supraphysiologic loads to the articular cartilage of the knee. These compounding factors are risks for OA development and conversion to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) [9, 15, 37].

Etiology and Natural History

Incidence and Etiology

Twelve to 14% of all orthopedic presentations involving the knee are due to a meniscus tear [3]. Meniscus root tears, in particular, were relatively unknown until Pagnani et al. described medial meniscus posterior root tears (MMPRTs) with associated meniscus extrusion in 1991 [38]. Ten to twenty percent of patients undergoing meniscectomy or repair are estimated to have a root tear with an estimated 100,000 patients affected annually, though the prevalence may be higher given only recent increase in identification and recognition of importance [7, 39–41].

Lateral root tears more commonly result from acute, traumatic injury in a young active individual with concomitant single or multiligamentous injury [6•]. It is reported that 81% of lateral root tears occur with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury [42]. In these patients, secondary stabilization is lost as the PL roots and MFLs are known resistors against anterior tibial translation and internal rotation in the ACL deficient knee [43]. In contrast, around 70% of medial root tears are degenerative in nature [4], manifest in the fourth or fifth decade of life [26], and have a six time increased risk of having Outerbridge grade two or higher [42]. The PM root is the least mobile, and the mechanism of injury thought of as chronic, repetitive low-energy events such as standing from deep seated position in an older adult [15].

Natural History

The natural fate of MRTs is especially poor. Nonoperative management leads to inferior clinical outcomes as Krych et al. reported 31% of patients progressed to TKA at mean 30 months after diagnosis of PM root tear. Overall, 87% of patients failed nonoperative treatment based on patient reported outcomes, Kellgren-Lawrence grades, and rate of OA progression at 5 year follow up. Female gender was associated with lower subjective scores and higher rate of arthroplasty [44]. Tear-associated meniscus extrusion, seen as an outward radial displacement of the meniscus from the tibial articular cartilage on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is a known player in these poor outcomes with data showing progression of extrusion and medial compartment articular cartilage degeneration within one year from diagnosis [9]. Degree of extrusion is strongly correlated with degree of OA changes on radiographs, though it remains unclear whether root tear leads to subsequent extrusion and OA or whether existing extrusion is a preceding factor in tear and articular pathology [12].

Subchondral Insufficiency Fractures of the Knee (SIFK) and Articular Cartilage Lesions

In parallel, recent work shed light on spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee (SONK) seen with MRTs. Originally thought to occur in idiopathic relation [45], evidence and terminology now accurately reflects the etiology as tear-associated extrusion and loss of biomechanic competence resulting in subchondral insufficiency fractures of the knee (SIFK) [13, 46]. SIFK predominantly occurs with medial meniscus root and radial tears and has a known association with arthroscopic meniscectomy. Post-arthroscopic SIFK was documented in 28 patients, 75% of whom had a meniscus root or radial tear. Of these, 89% of SIFK involved the medial compartment and 75% had a BMI >35 [14•]. Unfortunately, this pathology is significant given the 30–50% rate of conversion to arthroplasty [13]. With the increase in machine learning utility in orthopedics, Pareek et al. created a model to predict progression to TKA following SIFK. They identified lateral meniscus extrusion, Kellgren-Lawrence (K-L) Grade 4, SIFK of the medial femoral condyle, lateral MRT, and medial meniscus extrusion to be independent risk factors in order of importance, respectively [47].

The intricate interplay of root tear, extrusion, and contemporary articular cartilage lesion or pathology (SIFK) with subsequent OA development is an active area of research [9, 48]. State of the art treatment is now meniscus root repair. Other chondral restoration procedures such as chondroplasty, microfracture, osteochondral autograft transfer, and autologous chondrocyte implantation in efforts to preserve joint integrity in cases of articular damage are expanding as well [34, 49].

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Patient Symptoms & Physical Exam Findings

Despite representing a substantial portion of all meniscus pathology, MRTs are often misdiagnosed or undiagnosed at initial examination. This may be partially attributed to variable presentation, as patients do not tend to describe uniform mechanical symptoms or pain patterns. Injuries often occur while in deep flexion or squatting; patients may describe a rotational mechanism as well [15]. Lateral meniscus root injuries typically occur secondary to trauma or during athletics. Individuals with ACL disruption should be screened for concomitant lateral meniscus injury, as the two structures have been shown to have interdigitation and synergistical contributions to joint stability [4, 15, 26, 43]. Medial meniscus root injuries most often occur secondary to low-energy, chronic mechanisms, and degeneration. Consequently, there should be a high index of suspicion when seeing middle-aged or older patients with biomechanical risk factors such as high BMI or varus malalignment [7]. Although some patients present with complaints of posterior pain, as noted above, the lack of uniform mechanical symptoms limits the ability to diagnose MRTs based on history and physical exam maneuvers alone.

Imaging

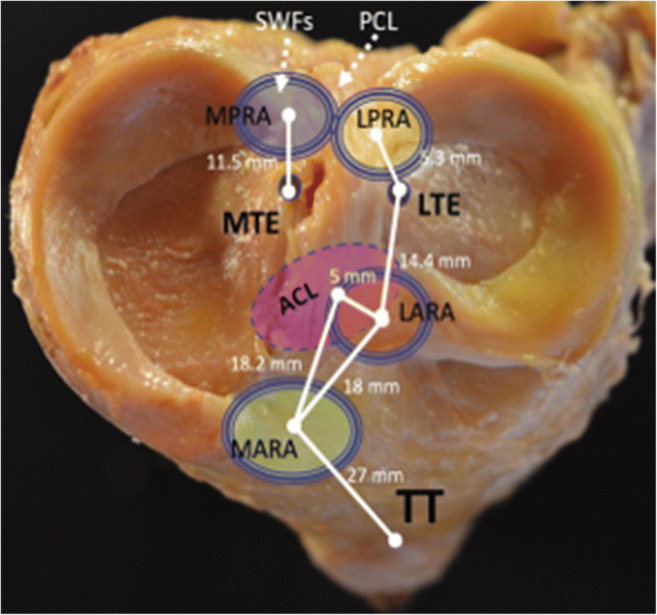

MRI continues to be the gold-standard for detection of MRTs by imaging, with T-2 weighted images as the preferred modality [7, 15, 26]. Several classic findings can help identify the presence of a meniscus root pathology (Fig. 2). These include “Truncation sign” (presence of a vertical, linear defect at the meniscal root on coronal series, often with meniscal extrusion), “Ghost sign” (absence of normal meniscal signal in sagittal series), and “Radial tear” (high signal, linear intensities appearing perpendicular to the meniscal root in axial series) [15, 26, 50].

Fig. 2.

Pre-op sagittal MRI showing ghost sign

Despite these signs, MRI has been reported to miss tears. Bhatia et al. reported up to 1/3rd of medial MRTs may be overlooked on imaging [7]. Similarly, Krych and colleagues further demonstrated preoperative MRI read by musculoskeletal-trained radiologists only detected 33% of lateral MRTs and only 50% of known tears were “clearly evident” on images reinspected post-operatively [50]. Thus, while MRI remains the most reliable non-operative method of MRT detection, surgeons should recognize the potential for missed diagnoses and carefully probe the posterior root of the lateral meniscus at the time of arthroscopy.

Classification

Classifying injuries based on tear morphology allows for improved diagnosis and management. The classification system described by LaPrade et al. [51] remains the current standard. Type 1 (7%) is a partial, mechanically stable tear. Type 2 (68%) are complete radial tears occurring within 9 mm of bony root attachment and are further subdivided: Type 2A occur within <3 mm, Type 2B within 3mm to <6mm, and Type 2C within 6mm to 9mm. Type 3 (6%) are complete root detachment with concomitant bucket-handle. Type 4 (10%) are complete root detachment in the setting of complex oblique tears. Type 5 (9%) are bony avulsion fractures at the root attachment [15, 49, 51].

Extrusion

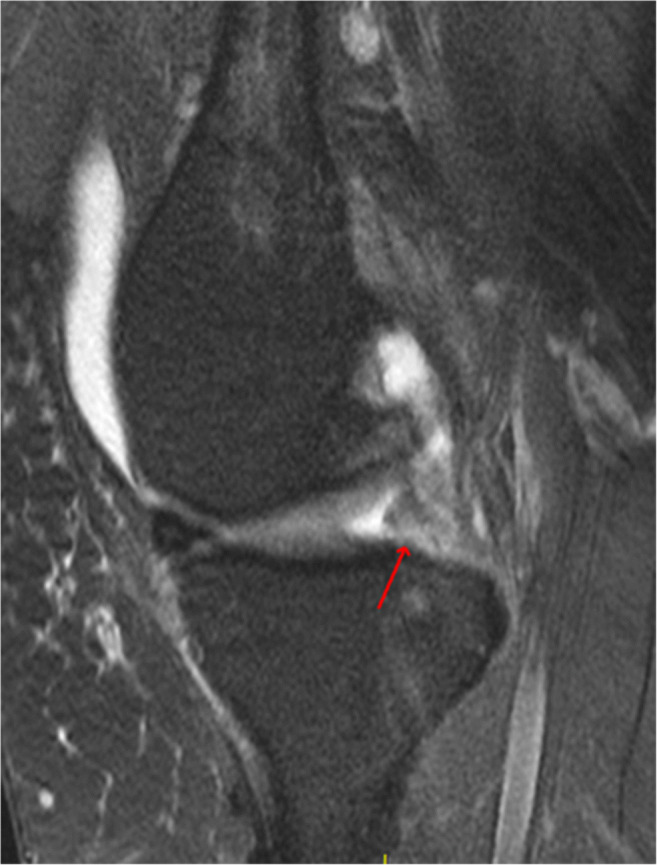

With increasing awareness regarding meniscal pathologies extrusion has become an area of recent focus. Defined as meniscus displacement of <3mm (minor) or >3mm (major) beyond the tibial plateau, this morphology is associated with MMPRTs (Fig. 3) and a predictor of tibiofemoral cartilage loss [7, 11, 15]. The associated cartilage loss appears to be contingent on the amount of extrusion, as less extrusion after repair has been linked to greater cartilage protection [12]. Although connected, the exact relationship between MRTs and extrusion remains ill-defined. Recent literature has demonstrated meniscotibial (MT) ligament disruption and associated meniscus extrusion to be a predecessor to MRTs, which may be caused by increased biomechanical forces after failure of the MT ligament [8, 12].

Fig. 3.

Pre-op coronal MRI showing PMMRT (red arrow) with extrusion

Centralization

Recent focus has been given to the concept of medial meniscus centralization prior to repair. The MT ligament has been found to be a key component of meniscus stability and when disrupted, can lead to worsened meniscus instability and displacement [12]. Correcting MT ligament deficiencies by securing the midbody of the meniscus to the tibial articular surface has been shown to significantly minimize or fully correct meniscus extrusion [11, 52, 53]. Initial studies investigating the utility of augmenting current repair strategies with centralization support continued research for its role in restoring tibiofemoral contact mechanics [21, 22, 49, 54, 55, 56•].

Treatment Options

Patients diagnosed with medial MRTs have a variety of treatment options available to them at this time. These include non-operative management, meniscectomy, and various styles of repair. Certain methods remain superior in overall patient outcomes and preservation of joint longevity.

Non-operative Management

Patients wishing to avoid surgical intervention can attempt nonoperative treatment. This typically entails a course of anti-inflammatory medications, activity modification, and physical therapy or supervised exercise program [5, 57, 58]. Guided intra-articular joint injections have also ameliorated pain and mechanical function in degenerative MRTs [59].

Despite some early symptomatic benefits, leaving meniscal pathology unaddressed has been demonstrated to negatively impact joint longevity [5, 57, 58, 60]. Neogi et al. showed the clinical improvements to be typically short-lived, peaking at approximately 6 months post-treatment before subsequently decreasing. Additionally, non-operative management is associated with poor clinical outcomes, worsening arthritis, and a relatively high rate of arthroplasty [5, 58, 60]. Furthermore, patients with large meniscus extrusion should not be considered for non-operative management, as large extrusion correlates with worsened outcomes [57].

Arthroplasty

Arthroplasty represents a dependable treatment option for patients with MRTs and end stage arthritis refractory to conservative measures. Tagliero and colleagues completed a matched case control study comparing outcomes in patients who underwent arthroplasty for secondary OA (n=75) versus patients with primary OA (n=150) and reported similar improvements in pain, activity level, complications, and reoperation rates between the two cohorts [60].

Meniscectomy

Previously a staple of meniscus pathology treatment, partial meniscectomy (PMM) is uncommonly utilized in modern treatment of MRTs. The meniscus, as mentioned previously, is a key biomechanical component of the knee; multiple studies have demonstrated its ability to protect the knee against OA development. MRTs have been theorized to increase tibiofemoral contact pressures [16, 61], thus already increasing risk of OA. Although patients can experience initial improvements, particularly symptomatic relief, PMM has demonstrated similar outcomes to non-operative management and provides no benefit in halting arthritic progression [61, 62]. A recent comparative study of matched PMM and non-operatively treated patients reported poor clinical outcomes and 54% progression to TKA at mean 54.3 months in those who underwent PMM. Female gender, increased BMI, and meniscus extrusion were associated with worse outcomes [61].

Repair

Due to its contributions to biomechanical stability and joint integrity, preservation of the meniscus is essential for overall joint preservation. There continues to be mounting evidence of improved joint longevity after repair of MRTs compared to treatment with meniscectomy or non-operative management [18•, 19•, 61, 63, 64]. Moreover, Faucett et al. completed a meta-analysis with cost-effectiveness modeling that compared meniscus repair, meniscectomy, and nonoperative treatment approaches among middle-aged patients with medial MRT. The authors reported MRT repair leads to less OA and is a cost-saving intervention. Overall, evidence supports meniscus repair as the preferred initial intervention in good candidates [17•]. Similarly, encouraging results have been published in cohorts with lateral MRTs treated with repair. As reported by Krych et al., there is data to suggest even greater improvements in clinical and functional outcomes after lateral MRT repair [6•] compared to peers with medial root pathology. While these increases may reflect differences in injury populations, the relative youth and high activity levels typical of patients with lateral MRT further necessitates treatment that allows both return to function and long-term joint preservation.

Repair Indications

Indications

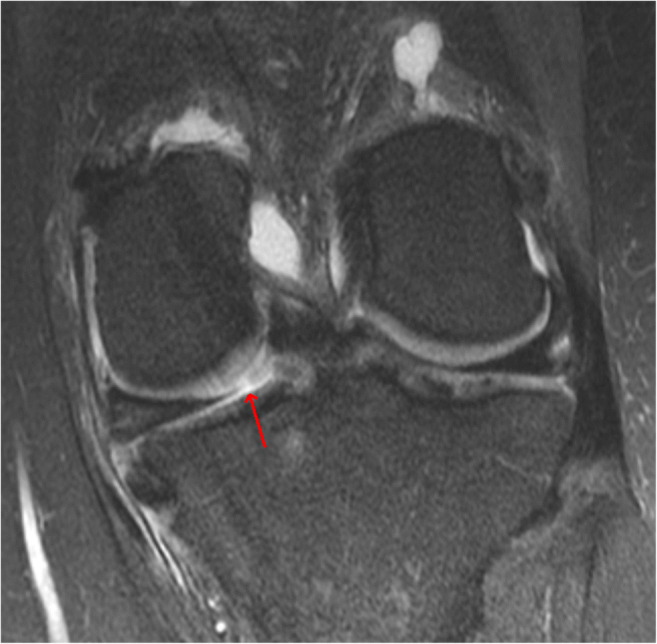

Although repair has demonstrated promising results, patient selection (Fig. 4) remains paramount to successful outcomes [6•, 15]. Young, active patients with an otherwise healthy knee are the optimal candidates for surgical repair. Older patients should also be considered depending on joint health, activity level, and presence of comorbidities such as malalignment, OA, and BMI status. It is essential to correct any concomitant ligamentous or cartilaginous pathology at time of repair to mitigate risk of failure [65, 66]. Accordingly, surgeons must carefully review individual patient risk factors and injuries to determine the likelihood of successful treatment. In short, however, patients with intact cartilage (K-L grade ≤2) and acute injuries should undergo repair.

Fig. 4.

Flowchart showing indications and contraindications for meniscus root tear repair. Reproduced with permission from Krych AJ, Hevesi M, Leland DP, Stuart MJ. Meniscal Root Injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28 [12]:491-9 [3]

Absolute Contraindications

Repair has been found to be unsuccessful in patients with substantial joint deformity, which includes varus malalignment >10 degrees, subchondral bone collapse, diffuse chondromalacia of grade 3 or higher, or K-L grade ≥ 3 on radiograph. Patients unwilling or unable to utilize crutches for 6 weeks should also be excluded [6•, 15, 49, 67].

Relative Contraindications

There are some patient cohorts in which the decision to pursue surgery should be met with caution. Generalized OA and varus malalignment >5 degrees are believed to lessen the benefits of repair [15, 65], although the latter is somewhat controversial as mild to modest varus alignment has also shown equivocal outcomes [68•]. Consequently, those with isolated mild to moderate varus (5–10 degrees) should not be automatically excluded for consideration of root repair. However, both mild malalignment (< 5 degrees) and obesity (BMI> 30) are risk factors for potential failure secondary to increased stress on the repair construct [15, 69].

Repair Techniques

Repair Options

Repair of MRTs is primarily executed by achieving direct fixation with suture anchors or by utilizing sutures pulled through a transtibial tunnel. In a direct comparison, Kim and colleagues found the two techniques to have equivalent outcomes. Each construct demonstrated similar reductions in meniscus extrusion, medial root tear gaps, and rates of complete healing [70]. Although repair has shown to demonstrate superior outcomes to both meniscectomy and nonoperative management, the margin for error in achieving a functionally sufficient repair appears to be small. Starke et al. reported that just 3mm of misalignment in repair placement greatly inhibits the meniscus’s biomechanical abilities [71].

Suture Anchor Repair

Suture anchor constructs enable root repair without creating tibial bone tunnels, thus allowing for utilization in patients with concomitant multiligamentous pathology or skeletal immaturity. This all arthroscopic technique was first described by Engelsohn [72], with subsequent modifications described by Lee et al. [73]. After initial suture placement on the posterior and anterior meniscus thirds in a vertical fashion, a posteromedial portal is established. The posteromedial portal is adjacent to the neurovascular bundle and requires specialized arthroscopic instruments. Although this repair technique has other attributes, such as placement of anchors closer to the native root and minimal disruption of tibial bone, it is technically challenging, it requires great care to minimize injury to cartilaginous tissue and the nearby neurovascular bundle.

Transtibial Pull-Through Repair

The transtibial pull-through technique utilizes a transosseous tunnel to reduce the meniscus root to the tibial plateau via sutures anchored to the anterior tibial cortex. Although this technique can interfere with concomitant procedures such as a high tibial osteotomy, it represents a pragmatic approach that is less technically demanding, omits the need to create a posterior portal adjacent to critical neurovascular structures, and does not require dedicated suture-passing devices. Consequently, the authors are advocates of transtibial fixation using standard and familiar arthroscopy portals, which has an established record of positive midterm to long-term results [20•, 49, 63, 74, 75].

Author’s Preferred Technique

Transtibial Pull-Through Repair

Our preferred technique of meniscus root repair has been described in detail [15, 49, 76]. Key steps, pearls, and pitfalls are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 [53]. Standard knee arthroscopy portals are used, including a portal ipsilateral to the tear to allow for direct visualization of the posterior root. The attachment of the meniscus horn is inspected and palpated with a probe (Fig. 5), which is of clinical significance because of the high rate of incomplete tear visualization on preoperative MRI [50]. In cases where it is difficult to obtain adequate visualization of the posterior meniscus roots and their respective compartments, we recommend consideration of (reverse) notchplasty or ‘pie crusting’ of the medial collateral ligament to provide satisfactory arthroscopic access [77]. Given that lateral MRTs are challenging to identify preoperatively, including in the setting of both primary and revision ACL reconstruction, surgeons must always thoroughly inspect the meniscus attachments and be ready to repair detected root tears.

Table 1.

Key steps in medial meniscus root repair and centralization

|

• Identify the tear and evaluate for meniscus extrusion. Of note, medial meniscus (MM) root tears are commonly missed on imaging • Place standard anteromedial (AM) and anterolateral (AL) portals • Use accessory AM portal proximal and 2 cm medial to standard AM portal • May need additional exposure with percutaneous medial collateral ligament (MCL) lengthening • Elevate or release the meniscotibial ligament using a curved elevator at the location of the tibial plateau periphery • Use 2-3 anchors to centralize the meniscus, starting posteromedially and working anteriorly • Perform posterior root transtibial root repair using self-retrieving suture-passing device to pass nonabsorbable suture in a simple cinch configuration (2 to 3 sutures) • Reduce the root to its anatomic footprint with tension and tibial fixation |

Table 2.

Pearls and pitfalls

|

Centralization Pearls • Enhance visualization with fat pad debridement • Percutaneous MCL lengthening can improve exposure • Optimize portal positioning with accessory AM portal • Improve meniscus mobility after release of MT ligament peripherally • Avoid soft tissue entrapment by utilizing cannula for suture management • Use self-retrieving suture passer • Tension the knotless sutures with a pusher/cutter through the accessory AM portal Meniscus Root Repair Pearls • Transtibial meniscal root drill guide allows anatomic placement of the meniscal root • Perform transtibial drilling prior to meniscal root suturing. This helps avoid entanglement • Self-retrieving suture passer allows for use of standard and familiar arthroscopy portals Pitfalls • Inadequate exposure • Iatrogenic cartilaginous injury • Poor patient adherence to rehabilitation protocol can lead to fixation failure |

Adapted with permission from: Leafblad ND, Smith PA, Stuart MJ, et al. Arthroscopic Centralization of the Extruded Medial Meniscus. Arthrosc Tech. 2021;10(1):e43-e48 [64]

Fig. 5.

Anterolateral viewing portal with probe through anteromedial portal showing PMMRT

After establishment of optimal portals and working space, attention is turned to tibial socket preparation. Given the importance of anatomic socket location, our preference is to use a root-specific tibial guide placed through the ipsilateral arthroscopy portal and centered on the meniscus root footprint. However, this can also be achieved with a standard ACL guide and drill. Subsequently, a 6-mm all-in-one guide pin/reamer is introduced into the joint through an incision on the proximal and medial tibia and deployed so that a shallow 6-mm socket is formed to provide fixation access to healing vascular subchondral bone. This can also be achieved with the standard 6-mm drill; however, this leads to greater bone loss along the length of the entire tibial tunnel compared with selective inside-out drilling with all-in-one instrumentation.

For meniscus fixation, a free No. 0 nonabsorbable suture is passed through the torn meniscus in a simple cinch configuration using a self-retrieving suture-passing device. A total of 2 to 3 locking sutures are placed, depending on the tissue size and quality, and then individually tightened, with the knee cycled to remove creep from the system. Subsequently, the sutures are tensioned through the tibial socket to reduce the meniscus root back to the native bony root attachment. Tibial fixation is subsequently obtained using a 5.5-mm anchor or, as classically described, a tibial button, with the knee in 90 degrees of flexion.

Medial Meniscus Centralization

Our preferred technique (Fig. 6) combines transtibial pull-through and centralization sutures [49, 53]. Meniscus centralization is completed prior to the transtibial pull-through method described above. Similarly, beginning with a diagnostic arthroscopy is fundamental to understanding the pathology prior to carrying out the surgical plan. Create an accessory medial portal that is proximal and medial to the standard anteromedial portal, to allow for the correct angulation of instruments. Using a curved elevator, perform a release of the MT ligaments off the periphery of the tibial plateau. Next, the anteromedial portal is utilized to place a knotless suture anchor just central to the peripheral rim of the tibial articular surface. With a self-retrieving suture passing device, via the anterolateral portal, pass the repair suture through the meniscocapsular junction in a mattress fashion. Tension the centralization suture down with an arthroscopic knot pusher or with a pusher-cutter device. Repeat this process to create a total of 2 to 3 centralization sutures. Once the meniscus centralization is complete, move on to the transtibial root repair.

Fig. 6.

Anterolateral viewing portal showing (A) knotless anchor placement for centralization (B) final anatomic root repair and (C) final construct of root repair (red arrow) with centralization (yellow arrow)

Postoperative Rehabilitation

Establishing a comprehensive postoperative management protocol is key to patient success. Throughout the first several months the optimal healing environment for the repair occurs when the meniscus remains free of loading of events, especially in deep flexion. The postoperative rehabilitation recommendations detailed below (Table 3) are specific for isolated root repairs. Patient specific alterations should be considered when patients undergo concomitant procedures (i.e., osteotomy, ligament reconstruction, etc.) which can influence optimal range of motion, weight-bearing, and timeline considerations. Consequently, communication between the patient, surgeon, and physical therapist should be prioritized [15, 49].

Table 3.

Meniscus root repair rehabilitation protocol

| Time (wk) | Hinged knee brace | Weight-bearing | Active/passive ROM | Loaded ROM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–6 | Full time | Toe-touch | 0°–90° | 0° |

| >6–16 | No | Full-Progressive | No restrictions | 0°–90° |

| >16–24 | No | Full | No restrictions | No restrictions |

Return to Sport

The point at which patients return to sport is influenced by the clinical timeline and the physical readiness of the patient. After 4–6 months of recovery, those who have attained normal strength with symmetric gaits are able to gradually begin participating in sporting activities. The typical timeline from isolated root repair to full return to high impact sporting activities is 6–9 months.

Meniscus Root Repair Outcomes

The main objective in treating patients with MRTs is to prevent or delay the development of progressive knee OA and, ultimately, facilitate their return to activity. As outlined above, both non-operative management and PMM are associated with poor clinical outcomes and the development of progressive tibiofemoral OA [7, 16, 44, 61, 62]. The early literature reporting on the outcomes of MRT repair have been encouraging [11, 17•, 18•, 20•, 78–81]. Bernard et al. compared 45 age, sex, and K-L grade matched patients with known medial MRT treated with either non-operative management (n =15), transtibial pull-through repair (n = 15) or PMM (n = 15). Those who underwent repair showed significantly decreased OA progression and rates of progression to TKA than those managed with either PMM or non-operative regimen [18•]. Chung and colleagues investigated the clinical outcomes and mid- to long-term survival rates of 91 patients with medial MRTs treated with transtibial pullout repair. The authors noted significant improvements in patient reported outcomes and an overall 92% clinical survival rate at 8 years with only 1 patient (1.1%) progressing to TKA [74]. The same group observed 37 patients for a minimum of 10 years after medial MRT repair in effort to determine the long-term predictors of clinical failure after surgical root repair. Risk factors for failure, defined as conversion to arthroplasty, were preoperative varus alignment >4 degrees (OR 3.7) and postoperative meniscal extrusion (OR 1.5) [82•]. Notably, the timing surrounding operative repair following MRT may influence surgical outcomes. Moon et al. demonstrated this relationship in their 2020 review of 2-year outcomes [83•]. Decreased length of time between injury and repair has been associated with decreased meniscal extrusion, particularly if repair is undertaken within 13 weeks or less from time of injury. Importantly, meniscus extrusion is thought to be a reflection of hoop tension, and increased meniscal extrusion is an independent predictor of tibiofemoral cartilage loss [15, 83•].

The last two decades of MRT literature have increased our understanding of repair techniques and the strong association between meniscus extrusion and the progression of OA; however, contemporary repair concepts focused exclusively on anatomic root repair are deficient in their ability to fully correct extrusion and the associated progression of OA [11, 54, 55, 84]. Krych and colleagues studied the progression of MMPRTs utilizing serial MRIs and reported progressive meniscus extrusion and medial compartment articular cartilage degeneration within 1 year from diagnosis [9]. Additionally, Chung et al. performed pullout fixation on 39 patients with MMPRTs and compared 5-year outcomes between patients with increased extrusion (preop vs. 1 year postop) and patients with decreased extrusion. The group with decreased meniscus extrusion following surgery had significantly decreased joint space narrowing and significantly better K-L grades and clinical scores compared to the cohort with increased meniscus extrusion [11]. Importantly, both repair groups demonstrated significant postoperative clinical score improvements at final follow-up [63].

Koga et al. described the arthroscopic technique of meniscus centralization in effort to enhance current root repair strategies where the displaced meniscus is “centralized” by anchoring it onto the rim of the tibial plateau prior to repair [21, 22]. Although limited, early studies combining centralization with anatomic repair have shown encouraging results for additional cartilage protection [49, 52, 54]. Mochizuki et al. recently reported on 26 patients with medial MRT repair augmented by centralization with 2-year follow up and demonstrated significant improvements in both clinical outcomes and extrusion ratio at final follow-up [56•]. Comparable outcomes have been reported following lateral MRT repairs supplemented with centralization [52]. Long-term clinical outcomes of this technique will impact the future of meniscus extrusion treatment [49].

Conclusions

Meniscus root attachments are vital for meniscus function and tibiofemoral joint preservation. Diagnosing meniscal root pathology can be difficult because of the nonspecific clinical presentation and difficult visualization on imaging. When left untreated, MRTs lead to meniscus insufficiency, decreased knee joint stability, and rapid cartilage degeneration. More recently, SIFK is another pathology attributed to root tears and has a known association with arthroscopy. Recent literature indicates that meniscus root repair is superior to both non-operative management and meniscectomy, supporting repair as the first-line treatment for select patient populations. The transtibial pull-through technique is a robust, safe, and pragmatic method for meniscus root repair with an established record of positive outcomes. Meniscus centralization is a newer strategy performed prior to root repair in effort to decrease extrusion by anchoring or “centralizing” the mid-body of the meniscus to the tibial articular surface. Early research hypothesizing that meniscus root repair augmented with centralization would offer added chondroprotective benefits have demonstrated encouraging results.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Lee, Dr. Lu, Anna Reinholz, and Sara Till declare they have no conflict of interest.

Dr. Camp reports personal fees from Arthrex, Inc, other from Zimmer Biomet Holdings, Inc, other from Gemini Medical LLC

Dr. DeBerardino reports paid consultant for Aesculap/B.Braun, board or committee member for the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, paid consultant, IP royalties, research support, and other services from Arthrex, Inc, board or committee member for Arthroscopy Association of North America, editorial or governing board of Current Orthopaedic Practice, paid consultant for EMOVI, board or committee member for the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery, and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine, paid consultant for the Joint Restoration Foundation, paid consultant for the Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation

Dr. Stuart reports royalties, consulting fee, and compensation for services other than consulting from Arthrex, Inc; editorial or governing board of AJSM, and research support from Stryker

Dr. Krych reports research support from Aesculap/B.Braun, editorial or governing board of the American Journal of Sports Medicine, consulting fees from Arthrex (through 2020), IP royalties (2019-2020), speaking fees (through 2019), and research support from Arthrex, research support from the Arthritis Foundation, research support and personal from Ceterix, personal from Gemini Mountain Medical, LLC, personal from Smith & Nephew, research support from Histogenics, board or committee member for the International Cartilage Repair Society, board or committee member for the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery, and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine, paid consultant for JRF Ortho, board or committee member of the Minnesota Orthopedic Society, board or committee member for the Musculoskeletal Transplantation Foundation, paid consultant for Vericel and honoraria (2017), consulting fee and royalties for Responsive Arthroscopy LLC, Joint Restoration Foundation honoraria, Responsive Arthroscopy (2019), serves on the medical board of trustees for the Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation (through 2018) ; grant from DJO (2020) and Exatech (2017)

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Meniscus

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Dustin R. Lee, Email: Lee.Dustin1@mayo.edu

Anna K. Reinholz, Email: Reinholz.Anna@mayo.edu

Sara E. Till, Email: Till.Sara@mayo.edu

Yining Lu, Email: Lu.Yining@mayo.edu.

Christopher L. Camp, Email: Camp.Christopher@mayo.edu

Thomas M. DeBerardino, Email: deberardino@uthscsa.edu

Michael J. Stuart, Email: Stuart.Michael@mayo.edu

Aaron J. Krych, Email: Krych.Aaron@mayo.edu

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

- 1.Logerstedt DS, Scalzitti DA, Bennell KL, Hinman RS, Silvers-Granelli H, Ebert J, Hambly K, Carey JL, Snyder-Mackler L, Axe MJ, McDonough CM. Knee pain and mobility impairments: meniscal and articular cartilage lesions revision 2018. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48(2):A1–a50. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2018.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox AJ, Bedi A, Rodeo SA. The basic science of human knee menisci: structure, composition, and function. Sports health. 2012;4(4):340–351. doi: 10.1177/1941738111429419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majewski M, Susanne H, Klaus S. Epidemiology of athletic knee injuries: A 10-year study. The Knee. 2006;13(3):184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pache S, Aman ZS, Kennedy MI, Nakama G, Moatshe G, Ziegler C, LaPrade R. Meniscal root tears: current concepts review. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2018;6:250–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krych AJ, Reardon PJ, Johnson NR, Mohan R, Peter L, Levy BA, Stuart MJ. Non-operative management of medial meniscus posterior horn root tears is associated with worsening arthritis and poor clinical outcome at 5-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(2):383–389. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4359-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.•.Krych AJ, Bernard CD, Kennedy NI, Tagliero AJ, Camp CL, Levy BA, et al. Medial versus lateral meniscus root tears: is there a difference in injury presentation, treatment decisions, and surgical repair outcomes? Arthroscopy. 2020;36(4):1135-41. Comparative study analyzing differences between medial and lateral MRTs in terms of diagnosis, treatment decisions and outcomes, and overall prognosis. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Bhatia S, LaPrade CM, Ellman MB, LaPrade RF. Meniscal root tears: significance, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(12):3016–3030. doi: 10.1177/0363546514524162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krych AJ, Bernard CD, Leland DP. Camp CL. Finnoff JT, et al. Isolated meniscus extrusion associated with meniscotibial ligament abnormality. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc: Johnson AC; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krych AJ, Johnson NR, Mohan R, Hevesi M, Stuart MJ, Littrell LA, Collins MS. Arthritis progression on serial mris following diagnosis of medial meniscal posterior horn root tear. J Knee Surg. 2018;31(7):698–704. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa CR, Morrison WB, Carrino JA. Medial meniscus extrusion on knee MRI: is extent associated with severity of degeneration or type of tear? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(1):17–23. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.1.1830017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung KS, Ha JK, Ra HJ, Nam GW, Kim JG. Pullout fixation of posterior medial meniscus root tears: correlation between meniscus extrusion and midterm clinical results. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(1):42–49. doi: 10.1177/0363546516662445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krych AJ, LaPrade MD, Hevesi M, Rhodes NG, Johnson AC, Camp CL, Stuart MJ. Investigating the Chronology of Meniscus Root Tears: Do Medial Meniscus Posterior Root Tears Cause Extrusion or the Other Way Around? Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(11):2325967120961368. doi: 10.1177/2325967120961368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pareek A, Parkes CW, Bernard C, Camp CL, Saris DBF, Stuart MJ, Krych AJ. Spontaneous osteonecrosis/subchondral insufficiency fractures of the knee: high rates of conversion to surgical treatment and arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(9):821–829. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.00381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.•.Barras LA, Pareek A, Parkes CW, Song BM, Camp CL, Saris DBF, et al. Post-arthroscopic subchondral insufficiency fractures of the knee yield high rate of conversion to arthroplasty. Arthroscopy. 2021;37(8):2545-53. Study investigating the controversy regarding the cause and associated outcomes of SIFK after knee arthroscopy. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Krych AJ, Hevesi M, Leland DP, Stuart MJ. Meniscal Root Injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(12):491–499. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allaire R, Muriuki M, Gilbertson L, Harner CD. Biomechanical consequences of a tear of the posterior root of the medial meniscus: similar to total meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(9):1922–1931. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.•.Faucett SC, Geisler BP, Chahla J, Krych AJ, Kurzweil PR, Garner AM, et al. Meniscus root repair vs meniscectomy or nonoperative management to prevent knee osteoarthritis after medial meniscus root tears: clinical and economic effectiveness. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(3):762-9. Meta-analysis and economic evaluation suggesting that repair of medial MRTs leads to less OA and is a cost-saving intervention when compared with meniscectomy and nonsurgical treatment. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.•.Bernard CD, Kennedy NI, Tagliero AJ, Camp CL, Saris DBF, Levy BA, et al. Medial meniscus posterior root tear treatment: a matched cohort comparison of nonoperative management, partial meniscectomy, and repair. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48(1):128-32. Matched cohort comparison study demonstrating less arthritis progression and knee arthroplasty in patients treated with meniscus root repair compared with nonoperative management and PMM. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.•.Chung KS, Ha JK, Ra HJ, Yu WJ, Kim JG. Root repair versus partial meniscectomy for medial meniscus posterior root tears: comparison of long-term survivorship and clinical outcomes at minimum 10-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48(8):1937-44. Study reporting clinical outcomes and long-term survival rates in patients undergoing transtibial pullout repair of MMPRTs. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.•.Krych AJ, Song BM, Nauert RF 3rd, Cook CS, Levy BA, Camp CL, et al. Prospective consecutive clinical outcomes after transtibial root repair for posterior meniscal root tears: a multicenter study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022;10(2):23259671221079794. Prospective study investigating clinical outcomes in a cohort of patients with both medial and lateral MRTs treated with transtibial pullout repair. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Koga H, Muneta T, Yagishita K, Watanabe T, Mochizuki T, Horie M, Nakamura T, Okawa A, Sekiya I. Arthroscopic centralization of an extruded lateral meniscus. Arthrosc Tech. 2012;1(2):e209–e212. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koga H, Watanabe T, Horie M, Katagiri H, Otabe K, Ohara T, Katakura M, Sekiya I, Muneta T. Augmentation of the pullout repair of a medial meniscus posterior root tear by arthroscopic centralization. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6(4):e1335–e13e9. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox AJ, Wanivenhaus F, Burge AJ, Warren RF, Rodeo SA. The human meniscus: a review of anatomy, function, injury, and advances in treatment. Clin Anat. 2015;28(2):269–287. doi: 10.1002/ca.22456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kennedy MI, Strauss M, LaPrade RF. Injury of the meniscus root. Clin Sports Med. 2020;39(1):57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2019.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaPrade CM, Ellman MB, Rasmussen MT, James EW, Wijdicks CA, Engebretsen L, et al. Anatomy of the anterior root attachments of the medial and lateral menisci: a quantitative analysis. The American journal of sports medicine. 2014;42(10):2386–2392. doi: 10.1177/0363546514544678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaPrade RF, Floyd ER, Carlson GB, Moatshe G, Chahla J, Monson JK. Meniscal root tears: Solving the silent epidemic. Journal of Arthroscopic Surgery and Sports Medicine. 2021;1:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellman MB, LaPrade CM, Smith SD, Rasmussen MT, Engebretsen L, Wijdicks CA, et al. Structural properties of the meniscal roots. The American journal of sports medicine. 2014;42(8):1881–1887. doi: 10.1177/0363546514531730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LaPrade MD, LaPrade CM, Hamming MG, Ellman MB, Turnbull TL, Rasmussen MT, et al. Intramedullary tibial nailing reduces the attachment area and ultimate load of the anterior medial meniscal root: a potential explanation for anterior knee pain in female patients and smaller patients. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1670–1675. doi: 10.1177/0363546515580296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forkel P, Herbort M, Sprenker F, Metzlaff S, Raschke M, Petersen W. The biomechanical effect of a lateral meniscus posterior root tear with and without damage to the meniscofemoral ligament: efficacy of different repair techniques. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(7):833–840. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chahla J, Nitri M, Civitarese D, Dean CS, Moulton SG, LaPrade RF. Anatomic Double-Bundle Posterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5(1):e149–e156. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johannsen AM, Civitarese DM, Padalecki JR, Goldsmith MT, Wijdicks CA, LaPrade RF. Qualitative and quantitative anatomic analysis of the posterior root attachments of the medial and lateral menisci. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2342–2347. doi: 10.1177/0363546512457642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schillhammer CK, Werner FW, Scuderi MG, Cannizzaro JP. Repair of lateral meniscus posterior horn detachment lesions: a biomechanical evaluation. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(11):2604–2609. doi: 10.1177/0363546512458574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carballo CB, Nakagawa Y, Sekiya I, Rodeo SA. Basic Science of Articular Cartilage. Clin Sports Med. 2017;36(3):413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camp CL, Stuart MJ, Krych AJ. Current concepts of articular cartilage restoration techniques in the knee. Sports Health. 2014;6(3):265–273. doi: 10.1177/1941738113508917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Redondo ML, Naveen NB, Liu JN, Tauro TM, Southworth TM, Cole BJ. Preservation of knee articular cartilage. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2018;26(4):e23–e30. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patil S, Tapasvi SR. Osteochondral autografts. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;8(4):423–428. doi: 10.1007/s12178-015-9299-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi ES, Park SJ. Clinical evaluation of the root tear of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus in total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2015;27(2):90–94. doi: 10.5792/ksrr.2015.27.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pagnani MJ, Cooper DE, Warren RF. Extrusion of the medial meniscus. Arthroscopy. 1991;7(3):297–300. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(91)90131-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonasia DE, Pellegrino P, D'Amelio A, Cottino U, Rossi R. Meniscal root tear repair: why, when and how? Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2015;7(2):5792. doi: 10.4081/or.2015.5792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, Kalske J, Järvinen TL, Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study (FIDELITY) Group Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2515–2524. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.LaPrade RF, Ho CP, James E, Crespo B, LaPrade CM, Matheny LM. Diagnostic accuracy of 3.0 T magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of meniscus posterior root pathology. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(1):152–157. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3395-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matheny LM, Ockuly AC, Steadman JR, LaPrade RF. Posterior meniscus root tears: associated pathologies to assist as diagnostic tools. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(10):3127–3131. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frank JM, Moatshe G, Brady AW, Dornan GJ, Coggins A, Muckenhirn KJ, Slette EL, Mikula JD, LaPrade R. Lateral meniscus posterior root and meniscofemoral ligaments as stabilizing structures in the ACL-deficient knee: a biomechanical study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(6):2325967117695756. doi: 10.1177/2325967117695756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krych AJ, Reardon PJ, Johnson NR, Mohan R, Peter L, Levy BA, Stuart MJ. Non-operative management of medial meniscus posterior horn root tears is associated with worsening arthritis and poor clinical outcome at 5-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(2):383–389. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4359-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robertson DD, Armfield DR, Towers JD, Irrgang JI, Maloney WJ, Harner CD. Meniscal root injury and spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee: An observation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91-B(2):190–195. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B2.21097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hussain ZB, Chahla J, Mandelbaum BR, Gomoll AH, LaPrade RF. The role of meniscal tears in spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee: a systematic review of suspected etiology and a call to revisit nomenclature. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(2):501–507. doi: 10.1177/0363546517743734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pareek A, Parkes CW, Bernard CD, Abdel MP, Saris DBF, Krych AJ. The SIFK score: a validated predictive model for arthroplasty progression after subchondral insufficiency fractures of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(10):3149–3155. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05792-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park JY, Kim BH, Ro DH, Lee MC, Han HS. Characteristic location and rapid progression of medial femoral condylar chondral lesions accompanying medial meniscus posterior root tear. The Knee. 2019;26(3):673–678. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozeki N, Seil R, Krych AJ, Koga H. Surgical treatment of complex meniscus tear and disease: state of the art. J isakos. 2021;6(1):35–45. doi: 10.1136/jisakos-2019-000380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krych AJ, Wu IT, Desai VS, Murthy NS, Collins MS, Saris DBF, Levy BA, Stuart MJ. High rate of missed lateral meniscus posterior root tears on preoperative magnetic resonance imaging. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(4):2325967118765722. doi: 10.1177/2325967118765722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LaPrade CM, James EW, Cram TR, Feagin JA, Engebretsen L, LaPrade RF. Meniscal root tears: a classification system based on tear morphology. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(2):363–369. doi: 10.1177/0363546514559684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koga H, Muneta T, Watanabe T, Mochizuki T, Horie M, Nakamura T, Otabe K, Nakagawa Y, Sekiya I. Two-year outcomes after arthroscopic lateral meniscus centralization. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(10):2000–2008. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leafblad ND, Smith PA, Stuart MJ, Krych AJ. Arthroscopic centralization of the extruded medial meniscus. Arthrosc Tech. 2021;10(1):e43–ee8. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2020.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Daney BT, Aman ZS, Krob JJ, Storaci HW, Brady AW, Nakama G, Dornan GJ, Provencher MT, LaPrade RF. Utilization of transtibial centralization suture best minimizes extrusion and restores tibiofemoral contact mechanics for anatomic medial meniscal root repairs in a cadaveric model. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(7):1591–1600. doi: 10.1177/0363546519844250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krych AJ, Nauert RF, 3rd, Song BM, Cook CS, Johnson AC, Smith PA, et al. Association between transtibial meniscus root repair and rate of meniscal healing and extrusion on postoperative magnetic resonance imaging: a prospective multicenter study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9(8):23259671211023774. doi: 10.1177/23259671211023774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.•.Mochizuki Y, Kawahara K, Samejima Y, Kaneko T, Ikegami H, Musha Y. Short-term results and surgical technique of arthroscopic centralization as an augmentation for medial meniscus extrusion caused by medial meniscus posterior root tear. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2021;31(6):1235-41. Case series demonstrating an improvement in meniscus extrusion following medial meniscus root repairs augmented with arthroscopic centralization. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Kwak YH, Lee S, Lee MC, Han HS. Large meniscus extrusion ratio is a poor prognostic factor of conservative treatment for medial meniscus posterior root tear. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(3):781–786. doi: 10.1007/s00167-017-4441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neogi DS, Kumar A, Rijal L, Yadav CS, Jaiman A, Nag HL. Role of nonoperative treatment in managing degenerative tears of the medial meniscus posterior root. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14(3):193–199. doi: 10.1007/s10195-013-0234-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Byrne C, Alkhayat A, Bowden D, Murray A, Kavanagh EC, Eustace SJ. Degenerative tears of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus: correlation between MRI findings and outcome following intra-articular steroid/bupivacaine injection of the knee. Clin Radiol. 2019;74(6):488.e1-.e8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Tagliero AJ, Kurian EB, LaPrade MD, Song BM, Saris DBF, Stuart MJ, et al. Arthritic progression secondary to meniscus root tear treated with knee arthroplasty demonstrates similar outcomes to primary osteoarthritis: a matched case-control comparison. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(6):1977–1982. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-06273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krych AJ, Johnson NR, Mohan R, Dahm DL, Levy BA, Stuart MJ. Partial meniscectomy provides no benefit for symptomatic degenerative medial meniscus posterior root tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(4):1117–1122. doi: 10.1007/s00167-017-4454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salata MJ, Gibbs AE, Sekiya JK. A systematic review of clinical outcomes in patients undergoing meniscectomy. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(9):1907–1916. doi: 10.1177/0363546510370196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chung KS, Ha JK, Yeom CH, Ra HJ, Jang HS, Choi SH, Kim JG. comparison of clinical and radiologic results between partial meniscectomy and refixation of medial meniscus posterior root tears: a minimum 5-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(10):1941–1950. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ro KH, Kim JH, Heo JW, Lee DH. Clinical and radiological outcomes of meniscal repair versus partial meniscectomy for medial meniscus root tears: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(11):2325967120962078. doi: 10.1177/2325967120962078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krych AJ. Editorial commentary: knee medial meniscus root Tears: "You may not have seen it, but it's seen you". Arthroscopy. 2018;34(2):536–537. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang EX, Abouljoud MM, Everhart JS, DiBartola AC, Kaeding CC, Magnussen RA, et al. Clinical factors associated with successful meniscal root repairs: A systematic review. The Knee. 2019;26(2):285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ahn JH, Jeong HJ, Lee YS, Park JH, Lee JW, Park JH, Ko TS. Comparison between conservative treatment and arthroscopic pull-out repair of the medial meniscus root tear and analysis of prognostic factors for the determination of repair indication. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135(9):1265–1276. doi: 10.1007/s00402-015-2269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.•.Moon HS, Choi CH, Yoo JH, Jung M, Lee TH, Jeon BH, et al. Mild to moderate varus alignment in relation to surgical repair of a medial meniscus root tear: a matched-cohort controlled study with 2 years of follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2021;49(4):1005-16. Highlights the importance of considering root repair in patients with mild to moderate varus alignment. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Brophy RH, Wojahn RD, Lillegraven O, Lamplot JD. Outcomes of arthroscopic posterior medial meniscus root repair: association with body mass index. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27(3):104–111. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim JH, Chung JH, Lee DH, Lee YS, Kim JR, Ryu KJ. Arthroscopic suture anchor repair versus pullout suture repair in posterior root tear of the medial meniscus: a prospective comparison study. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(12):1644–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stärke C, Kopf S, Gröbel KH, Becker R. The effect of a nonanatomic repair of the meniscal horn attachment on meniscal tension: a biomechanical study. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(3):358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Engelsohn E, Umans H, Difelice GS. Marginal fractures of the medial tibial plateau: possible association with medial meniscal root tear. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36(1):73–76. doi: 10.1007/s00256-006-0089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee SK, Yang BS, Park BM, Yeom JU, Kim JH, Yu JS. Medial meniscal root repair using curved guide and soft suture anchor. Clin Orthop Surg. 2018;10(1):111–115. doi: 10.4055/cios.2018.10.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chung KS, Noh JM, Ha JK, Ra HJ, Park SB, Kim HK, Kim JG. Survivorship analysis and clinical outcomes of transtibial pullout repair for medial meniscus posterior root tears: a 5- to 10-year follow-up study. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(2):530–535. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.08.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Woodmass JM, Mohan R, Stuart MJ, Krych AJ. Medial meniscus posterior root repair using a transtibial technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6(3):e511–e5e6. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hevesi M, Stuart MJ, Krych AJ. Medial meniscus root repair: a transtibial pull-out surgical technique. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2018;26(3):205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bert JM. First, do no harm: protect the articular cartilage when performing arthroscopic knee surgery! Arthroscopy. 2016;32(10):2169–2174. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang L, Zhang K, Liu X, Liu Z, Yi Q, Jiang J, et al. The efficacy of meniscus posterior root tears repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2021;29(1):23094990211003350. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Dai W, Yan W, Leng X, Wang J, Hu X, Ao Y. Comparative efficacy of root repair versus partial meniscectomy and observation for patients with meniscus root tears. J Knee Surg. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.Stein JM, Yayac M, Conte EJ, Hornstein J. Treatment outcomes of meniscal root tears: a systematic review. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2020;2(3):e251–ee61. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2020.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.LaPrade RF, Matheny LM, Moulton SG, James EW, Dean CS. Posterior meniscal root repairs: outcomes of an anatomic transtibial pull-out technique. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(4):884–891. doi: 10.1177/0363546516673996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.•.Chung KS, Ha JK, Ra HJ, Kim JG. Preoperative varus alignment and postoperative meniscus extrusion are the main long-term predictive factors of clinical failure of meniscal root repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021. Case series identifying preoperative varus alignment and postoperative extrusion as potential long term risk factors for failure following meniscus root repair. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 83.•.Moon HS, Choi CH, Jung M, Lee DY, Hong SP, Kim SH. Early surgical repair of medial meniscus posterior root tear minimizes the progression of meniscal extrusion: 2-year follow-up of clinical and radiographic parameters after arthroscopic transtibial pull-out repair. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48(11):2692-702. Study suggesting that meniscus root repair within 13 weeks from the onset of symptoms leads to better clinical outcomes, less extrusion, and less progression of arthritis. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Kim SJ, Choi CH, Chun YM, Kim SH, Lee SK, Jang J, Jeong H, Jung M. Relationship between preoperative extrusion of the medial meniscus and surgical outcomes after partial meniscectomy. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(8):1864–1871. doi: 10.1177/0363546517697302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]