Abstract

Introduction

In depression treatment, most patients do not reach response or remission with current psychotherapeutic approaches. Major reasons for individual non-response are interindividual heterogeneity of etiological mechanisms and pathological forms, and a high rate of comorbid disorders. Personalised treatments targeting comorbidities as well as underlying transdiagnostic mechanisms and factors like early childhood maltreatment may lead to better outcomes. A modular-based psychotherapy (MoBa) approach provides a treatment model of independent and flexible therapy elements within a systematic treatment algorithm to combine and integrate existing evidence-based approaches. By optimally tailoring module selection and application to the specific needs of each patient, MoBa has great potential to improve the currently unsatisfying results of psychotherapy as a bridge between disorder-specific and personalised approaches.

Methods and analysis

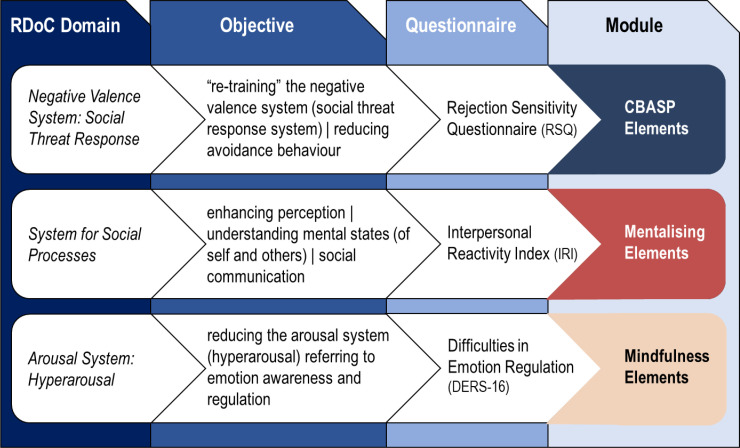

In a randomised controlled feasibility trial, N=70 outpatients with episodic or persistent major depression, comorbidity and childhood maltreatment are treated in 20 individual sessions with MoBa or standard cognitive–behavioural therapy for depression. The three modules of MoBa focus on deficits associated with early childhood maltreatment: the systems of negative valence, social processes and arousal. According to a specific questionnaire-based treatment algorithm, elements from cognitive behavioural analysis system of psychotherapy, mentalisation-based psychotherapy and/or mindfulness-based cognitive therapy are integrated for a personalised modular procedure.

As a proof of concept, this trial will provide evidence for the feasibility and efficacy (post-treatment and 6-month follow-up) of a modular add-on approach for patients with depression, comorbidities and a history of childhood maltreatment. Crucial feasibility aspects include targeted psychopathological mechanisms, selection (treatment algorithm), sequence and application of modules, as well as training and supervision of the study therapists.

Ethics and dissemination

This study obtained approval from the independent Ethics Committees of the University of Freiburg and the University of Heidelberg. All findings will be disseminated broadly via peer-reviewed articles in scientific journals and contributions to national and international conferences.

Trial registration number

DRKS00022093.

Keywords: Depression & mood disorders, PSYCHIATRY, Adult psychiatry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to investigate the feasibility of a modular-based psychotherapy (MoBa) approach for patients with comorbid depression and a history of childhood maltreatment generating effect estimates for subsequent confirmatory trials.

Clinicians will be provided with an evidence-based treatment algorithm to combine available treatment modules systematically instead of ad libitum eclecticism.

Using cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) as control condition represents a strong comparator for a rigorous evaluation with a high generalisability to the clinical reality.

Since no a priori values are established, the algorithm cut-offs used here are based on general population means of self-rated questionnaires.

Due to the limited sample size of this feasibility study (N=70), statistical analyses will be limited to exploratory comparisons of MoBa versus CBT, since tests between different modules within the MoBa intervention arm are not sufficiently powered.

Introduction

Until recently, depressive disorders have been predominantly conceptualised and researched with a focus on the primary diagnosis. This has led to the development of several disorder-specific approaches such as the cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT)1 and the interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT).2 While these approaches (among others) have proven efficacy in unipolar major depression, there is a large proportion of patients who do not respond (more than 50%) or do not reach full remission (about two-thirds) with first-line treatment,3 even when the procedure is in accordance with treatment guidelines.4 5 Major reasons for individual non-response and non-remission include interindividual heterogeneity of etiological mechanisms of depression and high rates of comorbid disorders of up to 80% in clinical and epidemiological studies.6–8 Particularly anxiety disorders and cluster C personality disorders are highly prevalent in major depressive disorder (MDD).9 These comorbid disorders typically predict poorer treatment outcomes for MDD10–13 or longer time to remission.14

Childhood maltreatment

One major transdiagnostic factor associated with cognitive, emotional, behavioural and interpersonal dysfunctions common to a wide range of disorders is childhood maltreatment (CM). CM has most frequently been operationalised based on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ),15 defined as onset reported before the age of 18 and meeting the criterion of at least ‘moderate to severe’ on one of the five trauma subtypes (emotional abuse, emotional neglect, physical abuse, physical neglect, sexual abuse). In depressive disorders, CM is highly prevalent (~46%),16 especially in early-onset and persistent depression with up to 80%.17 18 An emerging body of evidence suggests a significant relationship between emotional maltreatment (abuse and/or neglect) in particular and depression.19–22 Maltreated individuals are 2.7–3.7 times more likely to develop depression in adulthood, have an earlier depression onset and are twice as likely to develop a chronic or treatment-resistant course.16 CM was also associated with an elevated risk for comorbid disorders.18 23 Treated with psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, the probability of non-response is 1.9 times higher in depressed patients with early trauma compared with those without.16 Taken together, study results indicate that interpersonal trauma exposure complicates the treatment of depression and reduces the impact of traditional cognitive therapy or treatments such as psychoeducation, treatment as usual (TAU) or pharmacotherapy.24 However, some approaches like mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT)25 or the cognitive behavioural analysis system of psychotherapy (CBASP)26–28 show promising results in the subgroup of depressed patients with CM.

Impact of CM on social and emotional functioning

A growing body of evidence links interpersonal trauma in both youth and adults to difficulties in social and emotional functioning.24 Among other sequelae, CM usually results in marked avoidance behaviour9 with negative social consequences and in concomitant retardation of emotional maturational growth.28 29 These deficits are also expressed in terms of social threat hyperresponsivity (ie, being highly sensitive to social rejection and anxiously expecting, readily perceiving and overreacting to it),30–33 social stress and avoidance behaviour,34 35 lack of empathy and theory-of-mind36–38 and emotional dysregulation.39 40 These emotional and social dysfunctions are mediated in common brain circuits for emotion and salience regulation, fear and mentalising, suggesting that abnormalities in these functional pathways may be induced by CM.41 42 Despite these severe consequences of CM and their important implications for treatment, disorder-specific approaches for depression such as CBT or IPT do not specifically address the role of CM and the affected dimensions of functioning.

Personalised treatments

This calls for personalised treatments that target both comorbidities as well as underlying mechanisms and factors, which are central to the development and maintenance of psychological disorders. One of the challenges in the development of personalised approaches is to select treatment modules for targeted dysfunctions and to determine whether and in which sequence to combine them with standard treatment. In daily practice, it is left to the clinical judgement and expertise of the therapist to address the patient’s individual needs and comorbidities by adding various therapeutic strategies to the disorder-specific interventions. However, this choice of add-on strategies is not backed up by empirical evidence and thus hardly conveyable to usual clinical practice in a systematic way.43 Driven by these concerns, there has been growing consensus that a novel approach is needed in the way we classify, formulate, treat, and prevent depression and other mental disorders.44 45 Insel and Cuthbert46 postulated the concept of Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) to move ‘towards a new classification system’ of studying and validating transdiagnostic, dimensional constructs since psychiatric diagnosis seem to be no longer optimal as long as they remain restricted to symptoms and signs. The transdiagnostic procedure focuses on identifying the common and core maladaptive temperamental, cognitive, emotional, interpersonal and behavioural characteristics that underpin a broad array of diagnostic presentations47 and addresses them via specific modules in treatment.48 In this sense, a modular-based psychotherapy (MoBa) provides a structured approach of tailoring treatments to fit patient needs by allowing greater flexibility to consider interindividual differences and comorbidity.49 50 The modules, as sets of independent but combinable functional units, focus on common transdiagnostic dysfunctions and offer skills to improve, for example, emotion regulation, social competence, empathy or self-motivation. There is only one study51 in which emotion regulation skills were successfully added to CBT in depressed patients that had sufficient statistical power to detect a clinically significant effect.

Modular-based psychotherapy

Empirical support for the effectiveness of modular approaches following decision flowcharts is emerging lately.50 52 For instance, Weisz et al49 conducted a large randomised controlled trial (RCT) in which a Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma or Conduct Problems (MATCH) outperformed standard manual TAU as care as usual (TAU/CAU). The superiority of MATCH was found to be sustained in a 2-year follow-up53 and was replicated in a more recent trial.54 Another example of a modular approach to psychotherapy is Behavioural Interventions for Anxiety in Children with Autism (BIACA).55 By using a modular format and including an algorithm to guide the selection of modules, it offers a treatment approach for several anxiety disorders and obsessive–compulsive disorder for youths on the autism spectrum. BIACA was superior to waitlist and CAU in several RCTs.56 In adults, a recent RCT57 assessed the feasibility and efficacy of a modular transdiagnostic intervention for mood, stressor-related and anxiety disorders (HARMONIC trial) in preparation for a later-stage trial. The modular transdiagnostic intervention demonstrated superiority with moderate effect sizes compared with psychological treatment-as-usual.58 This represents early signs of a significant paradigm shift away from single-diagnosis approaches towards dimensional, transdiagnostic and modular-based conceptualisations.46 59

The here proposed rationale for a MoBa for depressed patients with comorbidity and a history of CM is two-fold: First, to include patients regularly seen in clinical practice showing (1) more often comorbid and heterogeneous complaints than the samples usually included in RCTs and (2) a limited treatment response to standard disorder-specific approaches. Second, tailoring the treatment to the specific characteristics and needs of patients with CM and comorbid depression can ensure that the psychotherapeutic process is responsive and may reach better treatment results. The MoBa intervention aims at interpersonal and emotional maturation by overcoming social threat hypersensitivity and interpersonal avoidance patterns and improving poor mentalisation as well as poor emotion regulation capacities. The rationale is supported by previous trials with empirically supported treatments such as CBASP for chronic depression,60–63 MBCT for depression prevention and treatment64–67 and Mentalisation-Based Therapy (MBT)68 for borderline personality disorder (BPD).69 70 In the here used design, MoBa complements standard CBT with modules compiling specific elements from CBASP, MBCT, and MBT focusing on three disturbed systems (figure 1). Those systems are part of the RDoC model and have been shown to be critically related to CM.

Figure 1.

Overview of the targeted RDoC domains and their corresponding objectives, assessments and modules. A detailed description of the modules is given below. CBASP, Cognitive Behavioural Analysis System of Psychotherapy; RDoC, Research Domain Criteria.

The negative valence system (acute, potential and sustained threat): social threat response and avoidance behaviour.9 34

The system of social processes: perception and understanding of self and others (understanding mental states), social communication, attachment.37 38 71

The arousal system: emotion awareness and arousal regulation.40 72–74

Objectives

This pilot study has a number of objectives appropriate to its status as a feasibility study:

Providing initial evidence for the efficacy of MoBa (reduction of clinician-rated depressive symptoms) as well as generating pilot data for the power calculation in terms of effect and sample size for a subsequent multicentre confirmatory trial.

Investigating the planned study design regarding the feasibility of recruitment, feasibility of applying cut-off values of self-reported deficits to select the modules, acceptability of the programme to therapists and patients as well as patient ratings of ‘usefulness’ (both overall and in terms of individual modules). A crucial goal is to refine the algorithm for the selection of modules based on questionnaires.

Explore potential moderators of the primary outcome (in a hypothesis-generating exercise and to help refine the intervention).

Methods and analysis

Study design

The bicentric study will be conducted at the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Medical Centre Freiburg, Germany and the Department of General Psychiatry, University Medical Centre Heidelberg, Germany. It is a parallel-arm RCT (N=70) comparing MoBa with CBT in 20 individual sessions over 16 weeks of treatment (twice weekly in weeks 1–4, then once per week in weeks 5–16). Participants will be assessed at screening, baseline, post-treatment and follow-up (6 months after end of treatment).

Study population and recruitment

Seventy outpatients with episodic/persistent major depression, comorbidity and CM will be recruited. Key inclusion and exclusion criteria are:

Inclusion criteria

Age eligibility: 18–65 years.

Episodic or persistent MDD or MDD superimposed on Dysthymia (‘double depression’) as the primary diagnosis (according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, SCID-5).75

A score of >18 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-24).76

History of CM: at least moderate to severe in one or more of the five CTQ-categories (emotional neglect, emotional abuse, physical neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse).15

At least one psychiatric comorbidity or more according to the SCID-5 (except for those described in the exclusion criteria below).

Exceeding the ‘cut-off’ value of at least one of the following measures (module questionnaires): (1) Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (RSQ,77)≥9.88, 2) Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI,78)<45, or 3) Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-16 (DERS-16,79)≥55.73.

Written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Acute risk of suicide.

Other current psychiatric disorders as primary diagnosis.

Comorbid schizophrenia, bipolar I disorder, neurocognitive disorder or substance dependence fulfilling criteria within the last 6 months.

A diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or more than three traits of BPD according to SCID-5 PD.

Severe cognitive impairment.

Serious medical condition (interfering with participation in regular sessions).

Other ongoing psychotherapy or psychotropic medication except antidepressant (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor/ serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor) and/or sleep-inducing treatment at baseline if stable for at least 3 weeks before inclusion (4 weeks for fluoxetine). The continuous intake of benzodiazepine is prohibited; the selective use of benzodiazepine as rescue medication on-demand for a maximum of 2 weeks is permitted.

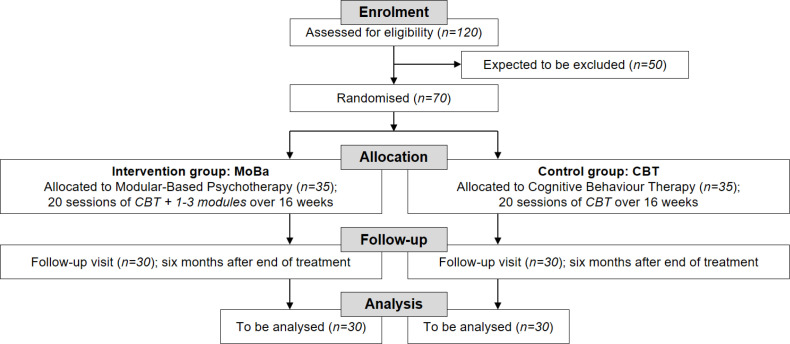

Patients will be recruited through psychiatric and psychotherapeutic outpatient clinics and private practices by announcement of the psychotherapy treatment offers. Approximately 120 patients will be prescreened for eligibility by research assistants via telephone with a brief prescreening guide that has been successfully used in prior depression studies. A total of N=70 patients will be randomised (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Trial design and flow of patients. CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; MoBA, modular-based psychotherapy.

Sample size

Due to the exploratory nature of the design and the lack of comparable studies, no formal sample size calculation is possible. One of the major aims of this trial is to generate pilot data for a subsequent sample size calculation for a confirmatory study. With reference to Billingham et al80 a medium sample size of 30 patients per group in pilot trials seems to be reasonable for the generation of pilot data for such estimation. That results in a total of 60 patients. Non-compliance and/or dropout of patients after randomization are assumed to be at most 14%. Therefore, 70 patients have to be randomised to observe the desired number of compliant patients, split in two groups for each of the two participating centres (FR=35, HD=35; figure 2).

Outcomes

The primary endpoint is the HRSD-24 measured by blind, independent raters at the conclusion of the 16 week treatment period. All secondary endpoints are describe in table 1.

Table 1.

Primary and secondary endpoints and corresponding measures

| Endpoint | Measure |

| Severity of depression (post-treatment) |

Primary endpoint: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-24)76at the end of treatment rated by trained and blinded clinicians. |

| Feasibility | Assessed by recruitment rates, distribution rates to the modules and therapists’ as well as patients’ ratings (Therapeutic Element Checklist; Working Alliance Inventory-Short Revised, WAI-SR)91 |

| Severity of depression (FUP) | HRSD-24 6 months after end of treatment rated by trained and blinded clinicians. |

| Social threat response system | Module questionnaire: The Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (RSQ) is a self-report questionnaire comprising 18 hypothetical interpersonal interactions with potential rejections by others (eg, “You ask someone you don’t know well out on a date”). It assesses the level of anxiety the patient feels about the outcome of each situation on a six point Likert scale ranging from “very unconcerned” to “very concerned”. The RSQ shows good internal consistency and test-retest reliability, and is a reliable measure of the anxious-expectations-of-rejection component of rejection sensitivity. For the German version, the original has been translated, adapted, and shown to be a homogeneous measure with good psychometric properties81. |

| Mentalising of others’ mental states/empathy | Module questionnaire: The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) is a 28-item self-report instrument that measures both cognitive and emotional aspects of empathy. Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘does not describe me well’) to 4 (‘describes me very well’). The questionnaire comprises four subscales (seven items each): Perspective Taking (eg, “I sometimes find it difficult to see things from the ’other guys‘ point of view.”), Fantasy (eg, “I daydream and fantasize, with some regularity, about things that might happen to me.”), Empathic Concern (eg, “I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me.”), and Personal Distress (eg, “I sometimes feel helpless when I am in the middle of a very emotional situation.”). The German version of the IRI92was reduced to only four items per scale and showed good psychometric properties. |

| The Mentalisation Questionnaire (MZQ)93 is a self-rating instrument for the assessment of mentalisation in patients with mental disorders and consists of 15 items. The MZQ can be considered a practicable instrument with acceptable reliability and sufficient validity to assess mentalisation in patients with mental disorders.93 | |

| Emotion awareness and regulation | Module questionnaire: A validated shorter version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale79 94with 16 items (DERS-16). For each of the DERS-16 items, participants are asked to “indicate how much it applies to your emotions right now” with response options ranging from 1 (‘not at all’) to 5 (‘completely’). The questionnaire has four subscales: non-acceptance (ie, non-acceptance of current emotions), modulate (ie, difficulties modulating emotional and behavioural responses in the moment), awareness (ie, limited awareness of current emotions) and clarity (ie, limited clarity about current emotions). Results of the study provide support for the reliability and validity of the DERS-16 as a measure of emotion regulation difficulties. |

| Response and remission rates | Response is defined as a reduction in the HRSD-24 score by at least 50% from baseline and a total score of less than 16; remission is defined a priori as an HRSD-24 score of ≤8. |

| Social and Occupational Functioning | The clinician-rated Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale95 assesses social role functioning irrespective of psychopathology. |

| Quality of life | The WHO Quality of Life Instrument (WHOQOL-BREF)96is a short form tool consisting of 26 items divided into four domains (physical health, psychological health, social relationships and the environment) to measure quality of life. |

| Self-rated depressive and anxiety symptoms | Self-ratings of depressive and anxiety symptoms will be obtained using the Beck Depression Inventory-II97 and the Beck Anxiety Inventory.98 |

| Attachment | The Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised99scale assesses attachment in adults. |

| Body connectedness | Self-ratings of body awareness and bodily dissociation will be obtained using the Scale of Body Connectedness.100 |

| Therapeutic alliance | The WAI-SR91 assesses three key aspects of the therapeutic alliance: (1) agreement on the tasks of therapy, (2) agreement on the goals of therapy and (3) development of an affective bond. |

| Course of depressive symptoms | Patients will fill out the Patient Health Questionnaire-9101 before every session to constantly monitor depressive symptom severity as a proxy of therapy progress or deterioration. |

| Therapeutic Element Checklist | All elements/strategies/components will be recorded immediately after each session including the approximate time the therapist used for applying those interventions using a Therapeutic Element Checklist designed for this feasibility trial. |

A comprehensive overview about the frequency and scope of all trial visits including all assessments and measures is depicted below (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Frequency and scope of trial visits. AE, adverse event; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; DERS, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; ECR, Experiences in Close Relationships; HRSD-24, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; IRI, Interpersonal Reactivity Index; MZQ, Mentalisation Questionnaire; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; RSQ, Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire; SAE, serious AE; SBC, Scale of Body Connectedness; SOFAS, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale; WAI, Working Alliance Inventory.

Adherence

Study psychotherapists are in a completed or far advanced stage of psychotherapy training. All therapist will execute CBT as well as MoBa interventions after thorough training to ensure a high treatment quality (1.5-day training course in CBT, 2.5-day training course in MoBa). All trainings are led by clinical experts in the field. The training process for therapists includes the supervision of one pilot case in each arm and an adherence rating for study certification. To check for adherence in the further process and to support the supervision, a ‘Therapeutic Element Checklist’ is filled out by the therapists immediately after each session. Supervisors will review the ‘Therapeutic Element Checklist’ regularly in ongoing supervision. All therapy sessions will be videotaped for adherence and supervision. Every fifth session will be supervised by the responsible supervisor in biweekly video conference meetings and/or by written feedback. Two clinical experts will conduct the diagnostic training of raters in SCID-5, HRSD-24 and Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale and inter-rater reliability will be ensured.

Experimental intervention: MoBa

The MoBa model complements standard CBT for depression with modules aiming at socioemotional cognitive deficits and compiling specific strategies from CBASP, MBT and mindfulness (figure 1). Content and implementation of the three modules are illustrated in table 2.

Table 2.

Content and implementation of modules

CBASP MODULE

|

| The CBASP module includes interpersonal discrimination training between abusing and well meaning others based on continued safety signals given by the therapist.28 As a first step, a so-called ‘Significant Other History’ (SOH) is conducted, a short procedure listing significant others who left an interpersonal-emotional ‘stamp’ in the patient’s learning history. From the SOH, causal conclusions are derived (eg, ‘Growing up with my mother led to the pervasive assumption that I have nothing to expect from others’). Based on the patient’s assumptions about relationships the patient experienced in his/her history with abusive significant others, a proactive ‘transference hypothesis’ is formulated stating the patient’s most relevant interpersonal expectation/fear regarding the therapist-patient encounter The transference hypothesis is then systematically contrasted with the therapist’s actual behaviour in ‘hot spot situations’, applying the structured ‘Interpersonal Discrimination Exercise’. By means of this exposure procedure, the patient learns to differentiate the abusive significant other (generalised to his/her social environment) from current non-abusive or well-intended persons by discrimination learning. Thus, the patient is enabled to overlearn dysfunctional expectations and reprogram the conditioned social threat systems. In addition, by enriching safety signals in therapists’ behaviour and re-establishing the perception of operant interpersonal contingencies, this intervention is designed to provide a secure learning environment to decrease interpersonal threat sensitivity. In addition, teaching the patient the mechanisms of complementary interpersonal processes illustrated by Kiesler’s circumplex model102 enables the patient to recognise the consequences of his/her own behaviour on other persons and to develop empathy (‘reading others’) and social problem-solving skills (element of CBASP). Genuine empathy and theory of mind skills are furthermore facilitated by the therapist’s ‘Disciplined Personal Involvement’ (DPI) and more specifically ‘Contingent Personal Reactivity’ (CPR), that is, expressing personal emotional reactions to the patients dysfunctional behaviour patterns in a disciplined way (including considering a teachable moment and relating it to the patient’s core pathology) and offering alternative behaviour. The key objective of this module is social fear extinction by overlearning conditioned associations and avoidance behaviour. |

MENTALISING MODULE

|

| The mentalising module contains modelling and teaching mentalising by learning to ‘read’ others' behaviour and thereby reconnecting the patient to his/her social environment and creating social competence. To promote mentalised affectivity (ie, mentalising own emotional states as described by MBT), the therapist introduces repetitive sequences to stimulate basic mentalising functions in the patient. Based on empathy, the therapist uses a ‘not knowing’ stance of exploration of the patients’ experiences and identifies context-related emotional reactions, raising ‘what-questions’ rather than ‘why-questions’. Two typical interventions to engage mentalising are the ‘Stop and Stand’ and the ‘Stop, Re-wind, Explore’ sequences68 In the first case, the therapist stops a patient who is stuck in drawing non-mentalising assumptions (eg, ‘everybody hates me’) by surprise or humour to subsequently help the patient to mentalise about his/her experiences. The second sequence generates a joined attention on the patients past experiences by shifting the focus back and forth within an episodic experience to make it accessible for the mentalising process. Genuine empathy and theory of mind skills are furthermore facilitated by the therapist’s ‘DPI’ (and more specifically ‘CPR’ as an element of CBASP as well. The key objective of this module is to improve mentalising capabilities in social interactions. |

MINDFULNESS MODULE

|

| This module integrates mindfulness-based exercises, which focus on (1) observing non-judgmentally internal and external stimuli, (2) shifting attention away from trauma-related inner ‘movies’ and monitoring skills to (3) overcome hyperarousal and experiential avoidance or being run over by one’s emotions. Mindfulness-based interventions aim to change a person’s perspective on his or her emotions and cognitions. This process is facilitated through mindfulness meditation (eg, body scan, formal sitting meditation) in which close attention is paid to the present moment while thoughts, feelings and body sensations are noted with an attitude of curiosity, non-judgement, and acceptance of psychological experiences. Mindfulness has been suggested to be effective via four mechanisms: attention regulation, body awareness, changes in perspective on the self, and emotion regulation.103 104 Mindfulness training enhances positive affect,105 decreases negative affect, and reduces maladaptive automatic emotional responses106 being associated with changes in areas of the brain responsible for affect regulation and stress impulse reaction.103 107 The key objective of this module is to improve emotion awareness and regulation in order to mitigate hyperarousal. |

CBASP, Cognitive Behavioural Analysis System of Psychotherapy; DERS-16, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-16; MBT, Mentalisation-based Psychotherapy; RDoC, Research Domain Criteria.

Selection of modules

The application of the modular intervention is preceded by a diagnostic assessment of the patient’s impaired systems (negative valence system, system of social processes or arousal system) according to the scores on the self-rated (1) RSQ (social threat response); (2) IRI (mentalisation, empathy) and (3) Brief Version of the DERS-16 (emotion awareness and regulation). The corresponding modular interventions will be applied if the cut-off value in one or more of these measures is exceeded. Since no a priori values are established, the cut-offs used here are defined as one SD above the general population mean, that is, the upper 16%.79 81 The problem(s) thus identified is/are assigned as the target for one, two or three of the modules (figure 3) according to the systematic treatment algorithm (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Decision tree algorithm for modular-based psychotherapy. CBASP, Cognitive Behavioural Analysis System of Psychotherapy; CBT, Cognitive–behavioural Therapy; MBT, Mentalisation-based Psychotherapy.

Treatment modules are selected according to the evidence-based treatment algorithm on the basis of the self-rated module-specific questionnaires. However, the selection of specific treatment strategies or techniques within a specific module (eg, BA or cognitive restructuring in CBT, use of Kiesler’s circumplex model or interpersonal discrimination exercise in CBASP) and the sequence of treatment strategies or techniques between modules are based on the clinical judgement and expertise of the therapist and the supervisors, since there is no reliable evidence to implement a data-driven decision algorithm for sequencing yet. The individual case conceptualisations are formulated in consultation with the supervisors who regularly check on the weekly intraindividual Patient Health Questionnaire-9 courses and the utilisation of treatment techniques within each session according to the Therapy Elements Checklist and the videorecordings.

Application of modules (time distribution)

The modules are not simply added as separate components, but rather integrated into the therapeutic process and course as add-on to the standard CBT procedure as basis for both interventions. Consequently, the amount of time spent with single CBT-techniques (eg, cognitive restructuring) will be reduced with increasing number of modules and the procedure will be condensed to behavioural activation (eg, identifying and promoting pleasant activities) as the most effective component of CBT.82 Depending on the selected number of modules, approximately one-third of the time will be spent with basic CBT procedures and two-thirds of the time with the application of modules. Therapists will document the time, which is spent with CBT procedures or with single modules, after each session.

Control intervention: CBT

CBT will be delivered according to the German standard manual by Hautzinger.83 The main CBT elements are (1) establishing therapeutic relationship, (2) psychoeducation, (3) behaviour activation, (4) cognitive restructuring and (5) maintenance and relapse prevention. CBT has been shown to be efficacious in depressed patients in prior clinical trials,84 85 but not specifically in this subgroup of depressed and comorbid patients exposed to CM.

Randomisation

The randomisation code will be generated by the Clinical Trials Unit Freiburg (CTU) using the following procedure to ensure that treatment assignment is unbiased and concealed from patients and investigator staff. Randomisation will be performed, stratified by site, in blocks of variable length in a ratio of 1:1. The block lengths will be documented separately and will not be disclosed to the sites. The randomisation code will be produced by validated programmes based on the Statistical Analysis System. This dataset is included in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) so that patients can be randomised directly in the electronic case report form (eCRF).

Blinding

All clinical ratings will be completed by trained and independent raters blinded to treatment assignment. Each of the sites implements procedures to mask a patient treatment assignment from the person who will evaluate the results of the clinical ratings through the following: (1) locating the raters at a separate physical location, and (2) reminding the patients at each visit not to mention anything that might reveal their treatment condition to the independent evaluator.

Data management and monitoring

Study data will be entered in pseudonymised form in a study database by authorised and trained members of the study team via eCRF. The data management will be performed with REDCap V.9, a fully web based remote data entry system based on web forms, which is developed and maintained by the REDCap Consortium (redcap@vanderbilt.edu). This system uses built-in security features to prevent unauthorised access to patient data, including an encrypted transport protocol for data transmission from the participating sites to the study database. An audit trail provides a history of the data entered, changed or deleted, indicating the processor and date. Monitoring is performed by CTU. Risk-based monitoring will be done according to ICH-GCP E6 (R2) and standard operating procedures to ensure patient’s safety and integrity of clinical trial data.

Statistical analysis

Before the start of the final analysis, a detailed statistical analysis plan will be prepared. This will be completed during the 'blind review' of the data, at the latest. The primary efficacy analysis will be performed according to the intention-to-treat principle and will therefore be based on the full analysis set (FAS) including all randomised patients. Patients are analysed as randomised regardless of any protocol deviations. This analysis corresponds to the analysis of the treatment policy estimand. The effects of CBT and MoBa with respect to the HRSD-24 score after 16 weeks of treatment (primary endpoint) will be estimated within a linear regression model, and the two-sided 95% CI will be calculated for the treatment effect. The model will include treatment and study centre as independent variables, as well as baseline HRSD-24 score. A conservative assumption of the effect size anticipated for the subsequent confirmative trial will be derived from these analyses by a combination of clinical and statistical judgement. Secondary endpoints will be analysed descriptively in a similar fashion as the primary outcome in the FAS, using regression models as appropriate for the respective type of data. Treatment effects will be calculated with two-sided 95% CIs. All secondary analyses are exploratory and are interpreted in a descriptive fashion.

The safety analysis includes calculation and comparison of frequencies and rates of serious adverse events (SAEs). Furthermore, statistical methods are used to assess the quality of data and the homogeneity of intervention groups. Data should be collected regardless of the patients’ adherence to the protocol, especially on the clinical outcome, to obtain the best approximation to the FAS. Data should also be collected on other therapies received post dropout. Patients with missing follow-up will be excluded. As the only available measurement of the patient is taken at baseline and the primary aim is feasibility, this can be considered as an adequate strategy. The reasons for missing postbaseline values will be collected and will be taken into consideration for the subsequent confirmatory trial.

Study results will be reported according to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines. Further details of the statistical analysis will be fixed before data base lock and start of the analysis. The responsible biostatistician will remain blind for treatment allocation throughout the study. For further information regarding the statistical analysis, see the extensive study protocol publicly accessible at https://www.drks.de/drks_web/navigate.do?navigationId=trial.HTML&TRIAL_ID=DRKS00022093.

Ethics and dissemination

This study obtained approval from the independent Ethics Committees of the University of Freiburg in August 2020 and the University of Heidelberg in October 2020. Additionally, the administrative department for governance and quality of the University Medical Centre Freiburg verified GCP conformity. All findings will be disseminated broadly via peer-reviewed articles in scientific journals and contributions to national and international conferences.

Consent to participate

At first contact, all prospects will be informed about the study in detail and will receive standardised participant information sheets. At screening, voluntary written informed consent for study participation and storage, evaluation and transfer of study-related data will be obtained from each study participant by research associates of the respective study centre. Withdrawal of written consent is possible at any time, without giving reasons. In the event of a withdrawal of the informed consent, patients can decide whether their data should be deleted or destroyed or whether they can be used in anonymised form for this research project.

Safety/harms

Side effects of evidence- based psychotherapies are fortunately rather rare (eg,86 87). According to the most recent meta-analysis, only approximately 5% of patients deteriorate while in psychotherapeutic treatment.3 AEs (eg, private/occupational stress or conflicts in the patient-therapist relationship) and SAEs (eg, severe events requiring stationary medical treatment or with potential permanent damage) are screened for at every assessment or therapy session. AEs have to be reported to the principal investigators (ES, SH) and SAEs to the independent experts. In addition, on-site data monitoring will be regularly conducted by a clinical monitor from CTU to ensure patients’ safety and integrity of the clinical data in adherence to the study protocol, as well as to check data quality and accuracy. Individual trial participation will be stopped if one of the following discontinuation criteria occurs:

Active suicidality

The physical health of the patient is at risk according to clinical judgement

Occurrence of an AE/SAE with therapeutic implications incompatible with the study

Newly occurring exclusion criteria (demanding further procedures not compatible with the continuation of the study participation)

Withdrawal of the informed consent

If the study principal investigator or the coprincipal investigator have serious ethical concerns because of the performance at one of the sites or severe safety concerns become apparent to the independent experts, the whole trial will be discontinued.

Trial status

Official study begin was in May 2020. The first patient was included in December 2020. Within the first months of recruiting, there were no difficulties regarding the recruitment and inclusion of eligible patients, or the implementation of the MoBa and CBT treatments. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, all in person contacts (assessments as well as psychotherapy sessions) are done while wearing appropriate face masks (surgical or FFP2) according to the national guidelines and the respective guidelines of the University Medical Centres in Freiburg and Heidelberg. The end of treatment is expected for August 2022 and data collection aims to be completed in April 2023.

Discussion

Most evidence-based treatment protocols are single-disorder-specific manuals disregarding common comorbidities and transdiagnostic clinical phenomena as sequelae of early trauma and childhood adversities. This leaves a mismatch between the available disorder-specific manuals and the clinical reality. Many clinicians consider the use of evidence-based manuals as challenging or even inadequate for their daily work and report resistances to the ‘oversimplified’, ‘rigid’, ‘inflexible’ or ‘flawed’ rationales and the ‘extensive efforts’ needed to maintain up-to-date knowledge by ongoing training.88 Even attending evidence-based workshops has little impact on clinicians’ decisions to use evidence-based treatment protocols in their practice resulting in the well-known underutilisation in community settings.89 90 In contrast to conventional evidence-based treatment protocols, a MoBa supports the eclectic approach of most clinicians by providing them with an evidence-based treatment algorithm to combine and integrate available treatment modules as independent but combinable sets of functional units systematically. This reduces the perceived challenges of using evidence-based approaches by ensuring a high flexibility and goodness-of-fit within a systematic framework for personalised treatments. By optimally tailoring module selection and application to the specific needs of each patient, MoBa has great potential to improve the currently unsatisfying results of psychotherapeutic treatments in research and clinical practice as a bridge between disorder-specific and personalised approaches. Due to the limited sample size of this feasibility study, statistical analyses will be limited exclusively to comparisons of MoBa versus CBT, since tests between different modules within the MoBa intervention arm are not sufficiently powered. While the modules are selected based on our evidence-based algorithm, the selection of specific treatment strategies or techniques within a specific module and the sequencing between modules are based on individual case conceptualisations, since there is no reliable evidence to implement a data-driven decision algorithm for sequencing yet.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The article processing charge was funded by the Baden-Wuerttemberg Ministry of Science, Research and Art and the University of Freiburg in the funding programme Open Access Publishing. We would like to thank Prof Fritz Hohagen, Prof Klaus Lieb and Prof Matthias Backenstraß for their contributions as independent experts, as well as Dr Thomas Fangmeier for his valuable assistance in determining the module cut-offs for the initial grant. Furthermore, we are grateful for the participation of Dr Anne Külz and Prof Svenja Taubner for their ongoing supervision and therapist trainings as experts of their fields in MBCT and MBT.

Footnotes

Contributors: ME, ES and SH were the main contributors in drafting this manuscript. ES and SH were the main contributors in designing this study with support by ME. CJ provided expertise on data monitoring, data management and statistical analyses. HP and MH provided important feedback on all manuscript versions. All authors approved the final version.

Funding: The clinical trial is financially supported by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG; GZ: SCHR 443/16-1).

Disclaimer: The funders do not control the final decision regarding any of aspects of the trial: design, conduct, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and dissemination of trial results.

Competing interests: ME received minor book royalties. SH received minor royalties for books with chapters on modular psychotherapy. MH received book royalties from several publishers. ES received book royalties and honoraria for workshops and presentations relating to Interpersonal Psychotherapy and CBASP.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Beck AT. Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ. Interpersonal psychotherapy of depression. Basic Books, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E, Ciharova M, et al. The effects of psychotherapies for depression on response, remission, reliable change, and deterioration: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2021;144:288–99. 10.1111/acps.13335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berlim MT, Turecki G. What is the meaning of treatment resistant/refractory major depression (TRD)? A systematic review of current randomized trials. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2007;17:696–707. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holtzheimer PE, Mayberg HS. Stuck in a rut: rethinking depression and its treatment. Trends Neurosci 2011;34:1–9. 10.1016/j.tins.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:593–602. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamers F, van Oppen P, Comijs HC, et al. Comorbidity patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large cohort study: the Netherlands study of depression and anxiety (NESDA). J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72:341–8. 10.4088/JCP.10m06176blu [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roca M, Gili M, Garcia-Garcia M, et al. Prevalence and comorbidity of common mental disorders in primary care. J Affect Disord 2009;119:52–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein JP, Roniger A, Schweiger U, et al. The association of childhood trauma and personality disorders with chronic depression: a cross-sectional study in depressed outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76:e794–801. 10.4088/JCP.14m09158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papakostas GI, Fava M. Predictors, moderators, and mediators (correlates) of treatment outcome in major depressive disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2008;10:439–51. 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.4/gipapakostas [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Souery D, Oswald P, Massat I. Clinical factors associated with treatment resistance in major depressive disorder: results from a European multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:1062–70. 10.4088/jcp.v68n0713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goddard E, Wingrove J, Moran P. The impact of comorbid personality difficulties on response to IAPT treatment for depression and anxiety. Behav Res Ther 2015;73:1–7. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agosti V. Predictors of remission from chronic depression: a prospective study in a nationally representative sample. Compr Psychiatry 2014;55:463–7. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank E, Cassano GB, Rucci P, et al. Predictors and moderators of time to remission of major depression with interpersonal psychotherapy and SSRI pharmacotherapy. Psychol Med 2011;41:151–62. 10.1017/S0033291710000553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl 2003;27:169–90. 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson J, Klumparendt A, Doebler P, et al. Childhood maltreatment and characteristics of adult depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2017;210:96–104. 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.180752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Struck N, Krug A, Yuksel D, et al. Childhood maltreatment and adult mental disorders - the prevalence of different types of maltreatment and associations with age of onset and severity of symptoms. Psychiatry Res 2020;293:113398. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiersma JE, Hovens JGFM, van Oppen P, et al. The importance of childhood trauma and childhood life events for chronicity of depression in adults. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:983–9. 10.4088/JCP.08m04521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphreys KL, LeMoult J, Wear JG, et al. Child maltreatment and depression: a meta-analysis of studies using the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl 2020;102:104361. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Infurna MR, Reichl C, Parzer P, et al. Associations between depression and specific childhood experiences of abuse and neglect: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2016;190:47–55. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandelli L, Petrelli C, Serretti A. The role of specific early trauma in adult depression: a meta-analysis of published literature. childhood trauma and adult depression. Eur Psychiatry 2015;30:665–80. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bausch P, Fangmeier T, Meister R, et al. The impact of childhood maltreatment on long-term outcomes in Disorder-Specific vs. nonspecific psychotherapy for chronic depression. J Affect Disord 2020;272:152–7. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teicher MH, Samson JA. Childhood maltreatment and psychopathology: a case for ecophenotypic variants as clinically and neurobiologically distinct subtypes. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:1114–33. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12070957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shirk SR, Deprince AP, Crisostomo PS, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for depressed adolescents exposed to interpersonal trauma: an initial effectiveness trial. Psychotherapy 2014;51:167–79. 10.1037/a0034845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams JMG, Crane C, Barnhofer T, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for preventing relapse in recurrent depression: a randomized dismantling trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2014;82:275–86. 10.1037/a0035036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nemeroff CB, Heim CM, Thase ME, et al. Differential responses to psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy in patients with chronic forms of major depression and childhood trauma. Focus 2005;3:131–5. 10.1176/foc.3.1.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein JP, Erkens N, Schweiger U, et al. Does childhood maltreatment moderate the effect of the cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy versus supportive psychotherapy in persistent depressive disorder? Psychother Psychosom 2018;87:46–8. 10.1159/000484412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCullough JP. Treatment for chronic depression. cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy. Guilford Press, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCullough J, Schramm E, Penberthy JK. CBASP as a distinctive treatment for persistent depressive disorder: distinctive features. Routledge, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bertsch K, Krauch M, Stopfer K, et al. Interpersonal threat sensitivity in borderline personality disorder: an Eye-Tracking study. J Pers Disord 2017;31:647–70. 10.1521/pedi_2017_31_273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu DA, Bryant RA, Gatt JM, et al. Failure to differentiate between threat-related and positive emotion cues in healthy adults with childhood interpersonal or adult trauma. J Psychiatr Res 2016;78:31–41. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herpertz SC, Bertsch K. The social-cognitive basis of personality disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2014;27:73–7. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bertsch K, Gamer M, Schmidt B, et al. Oxytocin and reduction of social threat hypersensitivity in women with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:1169–77. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shapero BG, Black SK, Liu RT, et al. Stressful life events and depression symptoms: the effect of childhood emotional abuse on stress reactivity. J Clin Psychol 2014;70:209–23. 10.1002/jclp.22011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erhardt A, Spoormaker VI. Translational approaches to anxiety: focus on genetics, fear extinction and brain imaging. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2013;15:417. 10.1007/s11920-013-0417-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnell K, Herpertz SC. Emotion regulation and social cognition as functional targets of mechanism-based psychotherapy in major depression with comorbid personality pathology. J Pers Disord 2018;32:12–35. 10.1521/pedi.2018.32.supp.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schnell K, Bluschke S, Konradt B, et al. Functional relations of empathy and mentalizing: an fMRI study on the neural basis of cognitive empathy. Neuroimage 2011;54:1743–54. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mattern M, Walter H, Hentze C, et al. Behavioral evidence for an impairment of affective theory of mind capabilities in chronic depression. Psychopathology 2015;48:240–50. 10.1159/000430450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weissman DG, Bitran D, Miller AB, et al. Difficulties with emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic mechanism linking child maltreatment with the emergence of psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol 2019;31:899–915. 10.1017/S0954579419000348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cloitre M, Stovall-McClough C, Zorbas P, et al. Attachment organization, emotion regulation, and expectations of support in a clinical sample of women with childhood abuse histories. J Trauma Stress 2008;21:282–9. 10.1002/jts.20339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lippard ETC, Nemeroff CB. The devastating clinical consequences of child abuse and neglect: increased disease vulnerability and poor treatment response in mood disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2020;177:20–36. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bock J, Wainstock T, Braun K, et al. Stress in utero: prenatal programming of brain plasticity and cognition. Biol Psychiatry 2015;78:315–26. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.02.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fonagy P, Luyten P. Fidelity vs. flexibility in the implementation of psychotherapies: time to move on. World Psychiatry 2019;18:270–1. 10.1002/wps.20657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barlow DH, Bullis JR, Comer JS, et al. Evidence-Based psychological treatments: an update and a way forward. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2013;9:1–27. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lyon AR, Lau AS, McCauley E, et al. A case for modular design: implications for implementing evidence-based interventions with culturally-diverse youth. Prof Psychol Res Pr 2014;45:57–66. 10.1037/a0035301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Insel TR, Cuthbert BN. Brain disorders? precisely. Science 2015;348:499–500. 10.1126/science.aab2358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harvey AG, Watkins E, Mansell W. Cognitive behavioral processes across psychological disorders: a Transdiagnostic approach to research and treatment. Oxford University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behavior Therapy 2004;35:205–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Palinkas LA, et al. Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth: a randomized effectiveness trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012;69:274–82. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ng MY, Weisz JR. Annual research review: building a science of personalized intervention for youth mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2016;57:216–36. 10.1111/jcpp.12470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berking M, Ebert D, Cuijpers P, et al. Emotion regulation skills training enhances the efficacy of inpatient cognitive behavioral therapy for major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom 2013;82:234–45. 10.1159/000348448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cuijpers P, Ebert DD, Acarturk C, et al. Personalized psychotherapy for adult depression: a meta-analytic review. Behav Ther 2016;47:966–80. 10.1016/j.beth.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chorpita BF, Weisz JR, Daleiden EL, et al. Long-Term outcomes for the child steps randomized effectiveness trial: a comparison of modular and standard treatment designs with usual care. J Consult Clin Psychol 2013;81:999–1009. 10.1037/a0034200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Park AL, et al. Child steps in California: a cluster randomized effectiveness trial comparing modular treatment with community implemented treatment for youth with anxiety, depression, conduct problems, or traumatic stress. J Consult Clin Psychol 2017;85:13–25. 10.1037/ccp0000133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wood JJ, Drahota A, Sze K, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized, controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2009;50:224–34. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01948.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Storch EA, Arnold EB, Lewin AB, et al. The effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013;52:132–42. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Black M, Hitchcock C, Bevan A, et al. The harmonic trial: study protocol for a randomised controlled feasibility trial of shaping healthy Minds-a modular transdiagnostic intervention for mood, stressor-related and anxiety disorders in adults. BMJ Open 2018;8:e024546. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Black M, Johnston D, Elliott R. A randomised controlled feasibility trial (the HARMONIC Trial) of a novel modular transdiagnostic intervention—Shaping Healthy Minds—versus psychological treatment-as-usual, for clinic-attending adults with comorbid mood, stressor- related and anxiety disorders. mrc-cbu.cam.ac [Preprint], 2022. Available: https://www.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Black-et-al.-Shaping-Healthy-Minds.pdf [Accessed 2 Feb 2022].

- 59.Dalgleish T, Black M, Johnston D, et al. Transdiagnostic approaches to mental health problems: current status and future directions. J Consult Clin Psychol 2020;88:179–95. 10.1037/ccp0000482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Negt P, Brakemeier E-L, Michalak J, et al. The treatment of chronic depression with cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled clinical trials. Brain Behav 2016;6:e00486. 10.1002/brb3.486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, et al. A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1462–70. 10.1056/NEJM200005183422001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schramm E, Kriston L, Zobel I, et al. Effect of Disorder-Specific vs nonspecific psychotherapy for chronic depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74:233–42. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schramm E, Kriston L, Elsaesser M, et al. Two-Year follow-up after treatment with the cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy versus supportive psychotherapy for early-onset chronic depression. Psychother Psychosom 2019;88:154–64. 10.1159/000500189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McCartney M, Nevitt S, Lloyd A, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention and time to depressive relapse: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2021;143:6–21. 10.1111/acps.13242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goldberg SB, Tucker RP, Greene PA, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the treatment of current depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis. Cognitive Behavior Therapy 2019;48:445–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Piet J, Hougaard E. The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention of relapse in recurrent major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2011;31:1032–40. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kuyken W, Hayes R, Barrett B, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (prevent): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2015;386:63–73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62222-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Handbook of Mentalizing in mental health practice. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Malda-Castillo J, Browne C, Perez-Algorta G. Mentalization-based treatment and its evidence-base status: a systematic literature review. Psychol Psychother 2019;92:465–98. 10.1111/papt.12195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bateman A, Fonagy P. Randomized controlled trial of outpatient mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2009;166:1355–64. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zilberstein K. Neurocognitive considerations in the treatment of attachment and complex trauma in children. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2014;19:336–54. 10.1177/1359104513486998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hofmann M, Fehlinger T, Stenzel N, et al. The relationship between skill deficits and disability-a transdiagnostic study. J Clin Psychol 2015;71:413–21. 10.1002/jclp.22156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fehlinger T, Stumpenhorst M, Stenzel N, et al. Emotion regulation is the essential skill for improving depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord 2013;144:116–22. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ochsner KN, Silvers JA, Buhle JT. Functional imaging studies of emotion regulation: a synthetic review and evolving model of the cognitive control of emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012;1251:E1–24. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06751.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Beesdo-Baum K, Zaudig M, Wittchen H-U. Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview Für DSM-5 [The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5-Clinician Version] (SCID-5-CV). Hogrefe, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967;6:278–96. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol 1996;70:1327–43. 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 1983;44:113–26. 10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bjureberg J, Ljótsson B, Tull MT, et al. Development and validation of a brief version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale: the DERS-16. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2016;38:284–96. 10.1007/s10862-015-9514-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Billingham SAM, Whitehead AL, Julious SA. An audit of sample sizes for pilot and feasibility trials being undertaken in the United Kingdom registered in the United Kingdom clinical research network database. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:104. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Staebler K, Helbing E, Rosenbach C, et al. Rejection sensitivity and borderline personality disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother 2011;18:275–83. 10.1002/cpp.705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:658–70. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hautzinger M. Kognitive Verhaltenstherapie Bei Depressionen. Auflage. Beltz Psychologie Verlags Union, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cuijpers P. Four decades of outcome research on psychotherapies for adult depression: an overview of a series of meta-analyses. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne 2017;58:7–19. 10.1037/cap0000096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Barth J, Munder T, Gerger H, et al. Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: a network meta-analysis. Focus 2016;14:229–43. 10.1176/appi.focus.140201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Linden M, Strauß B. Risiken und Nebenwirkungen von Psychotherapie: Erfassung, Bewältigung, Risikovermeidung. In: MWV Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. 1st ed, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hoffmann SO, Rudolf G, Strauß B, Strauß B. Unerwünschte und schädliche Wirkungen von Psychotherapie. Psychotherapeut 2008;53:4–16. 10.1007/s00278-007-0578-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cook SC, Schwartz AC, Kaslow NJ. Evidence-Based psychotherapy: advantages and challenges. Neurotherapeutics 2017;14:537–45. 10.1007/s13311-017-0549-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, et al. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: a review and critique with recommendations. Clin Psychol Rev 2010;30:448–66. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ecker AH, O’Leary K, Fletcher TL. Training and supporting mental health providers to implement evidence-based psychotherapies in frontline practice. Translational Behavioral Medicine 2021:ibab084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Munder T, Wilmers F, Leonhart R, et al. Working alliance Inventory-Short revised (WAI-SR): psychometric properties in outpatients and inpatients. Clin Psychol Psychother 2010;17:231–9. 10.1002/cpp.658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Paulus C. Der Saarbrücker Persönlichkeitsfragebogen zur Messung von Empathie (SPF-IRI), 2006. Available: http://bildungswissenschaften.uni-saarland.de/personal/paulus/homepage/empathie.html

- 93.Hausberg MC, Schulz H, Piegler T, et al. Is a self-rated instrument appropriate to assess mentalization in patients with mental disorders? development and first validation of the mentalization questionnaire (MZQ). Psychother Res 2012;22:699–709. 10.1080/10503307.2012.709325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2004;26:41–54. 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR. Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning, 1992. Available: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2143992 [Accessed 27 Jul 2021]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 96.WHOQOL Group . Development of the world Health organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL group. Psychol Med 1998;28:551–8. 10.1017/S0033291798006667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corperation, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck anxiety inventory manual. Psychological Corperation, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ehrenthal J, Dinger U, Lamla A, et al. Evaluation der deutschsprachigen Version des Bindungsfragebogens „Experiences in Close Relationships – Revised” (ECR-RD). Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2009;59:215–23. 10.1055/s-2008-1067425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Price CJ, Thompson EA. Measuring dimensions of body connection: body awareness and bodily dissociation. J Altern Complement Med 2007;13:945–53. 10.1089/acm.2007.0537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann 2002;32:509–15. 10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kiesler DJ. The 1982 interpersonal circle: a taxonomy for complementarity in human transactions. Psychol Rev 1983;90:185–214. 10.1037/0033-295X.90.3.185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, et al. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci 2011;6:537–59. 10.1177/1745691611419671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Arch JJ, Craske MG. Mechanisms of mindfulness: emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behav Res Ther 2006;44:1849–58. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Geschwind N, Peeters F, Drukker M, et al. Mindfulness training increases momentary positive emotions and reward experience in adults vulnerable to depression: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2011;79:618–28. 10.1037/a0024595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Khoury B, Lecomte T, Fortin G, et al. Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2013;33:763–71. 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Davidson RJ, Kabat-Zinn J, Schumacher J, et al. Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosom Med 2003;65:564–70. 10.1097/01.psy.0000077505.67574.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.