Abstract

The origin of switchable site selectivity during Pd-catalysed C–H alkenylation of heteroarenes has been examined through More O’Ferrall–Jencks, isotope effect, and DFT computational analyses, which indicate substitution of ionic thioether for pyridine dative ligands induces a change from selectivity-determining C–H cleavage to C–C bond formation, respectively.

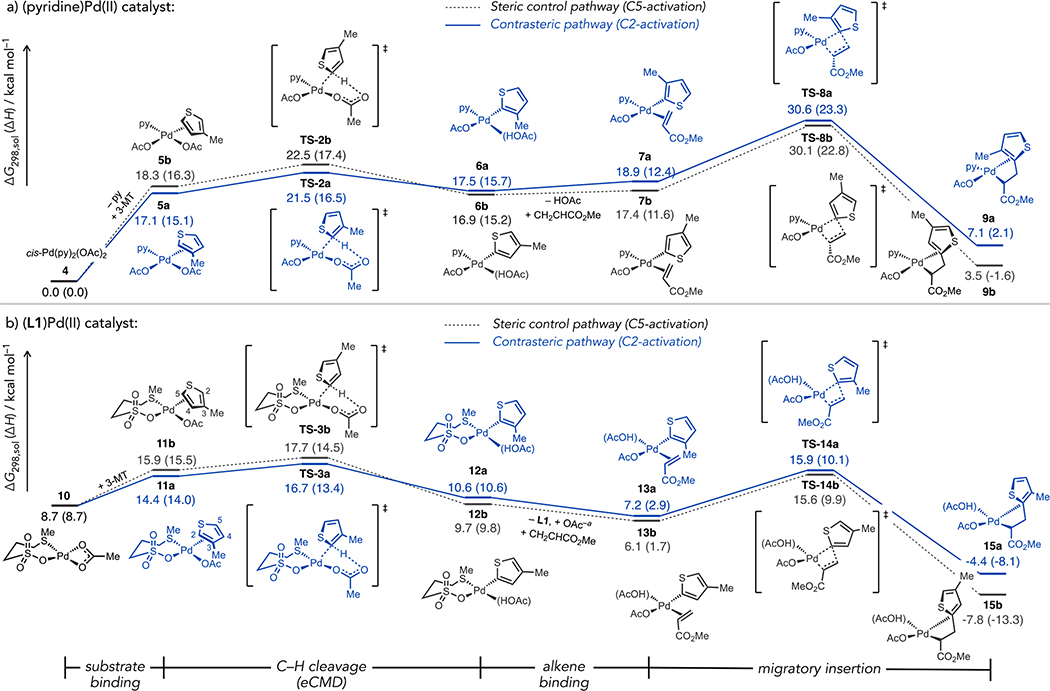

Catalyst control over site selectivity in the field of C–H functionalization holds the potential for expanded versatility and scope versus existing C–H functionalization methods dependent on directing group effects and remains a topical challenge within this field.1–3 Catalytic methods for undirected C–H functionalization reactions such as C–H borylation4–7 or silylation,8–10 oxidative C–H alkenylation11 (Fujiwara-Moritani),12–13 and direct arylation14–15 reactions frequently operate under steric control of site selectivity (Fig 1a). Recent advances have further refined that type of catalyst control in C–H alkenylation or alkynlation of substituted heteroarenes.16 In contrast, contra-steric site selectivity remains uncommon in undirected reactions, for instance by favouring the more hindered C2 site in 3-substituted five atom heteroarenes.17 Several recent studies nevertheless demonstrate the potential for ligand switchable control between steric and contra-steric selectivity (Fig 1b).18–20 This work considers the origin of catalyst control over selectivity in such systems.

Figure 1.

(a) Typical steric control of non-directed C–H functionalization of five-atom heteroarenes and (b) representative case of ligand-enforced contra-steric selectivity during Pd-catalysed C–H alkenylation.

Recently, our group reported examples of C–H alkenylation of 3-substituted five-atom pyrrole or thiophene substrates using thioether-coordinated Pd catalysts that enforce unusual, high selectivity for the contra-steric site (Fig 1b).18, 21 This selectivity pattern complements the typical undirected site selectivity for C–H alkenylation/alkynlation and is enabled simply by substitution of a thioether (e.g., L1 = MeS(CH2)3SO3−) for common pyridine type ligands. We have been interested in establishing a mechanistic basis for this selectivity switch to potentially leverage this tunable catalyst control in other contexts. Fluctuations in the polarization of the C–H cleavage transition state were examined in previous work, which led to the proposal of an electrophilic counterpart to the standard concerted metalation-deprotonation model for heterolytic C–H cleavage termed electrophilic CMD or eCMD.22–24 We report here a comparative mechanistic study of prototypical catalysts favouring steric or contra-steric control during C–H alkenylation of thiophenes. The available data are most consistent with selectivity differences due to a switch from reversible to irreversible C–H cleavage25–27 as opposed to reactions involving distinct mechanisms (i.e., CMD vs eCMD).

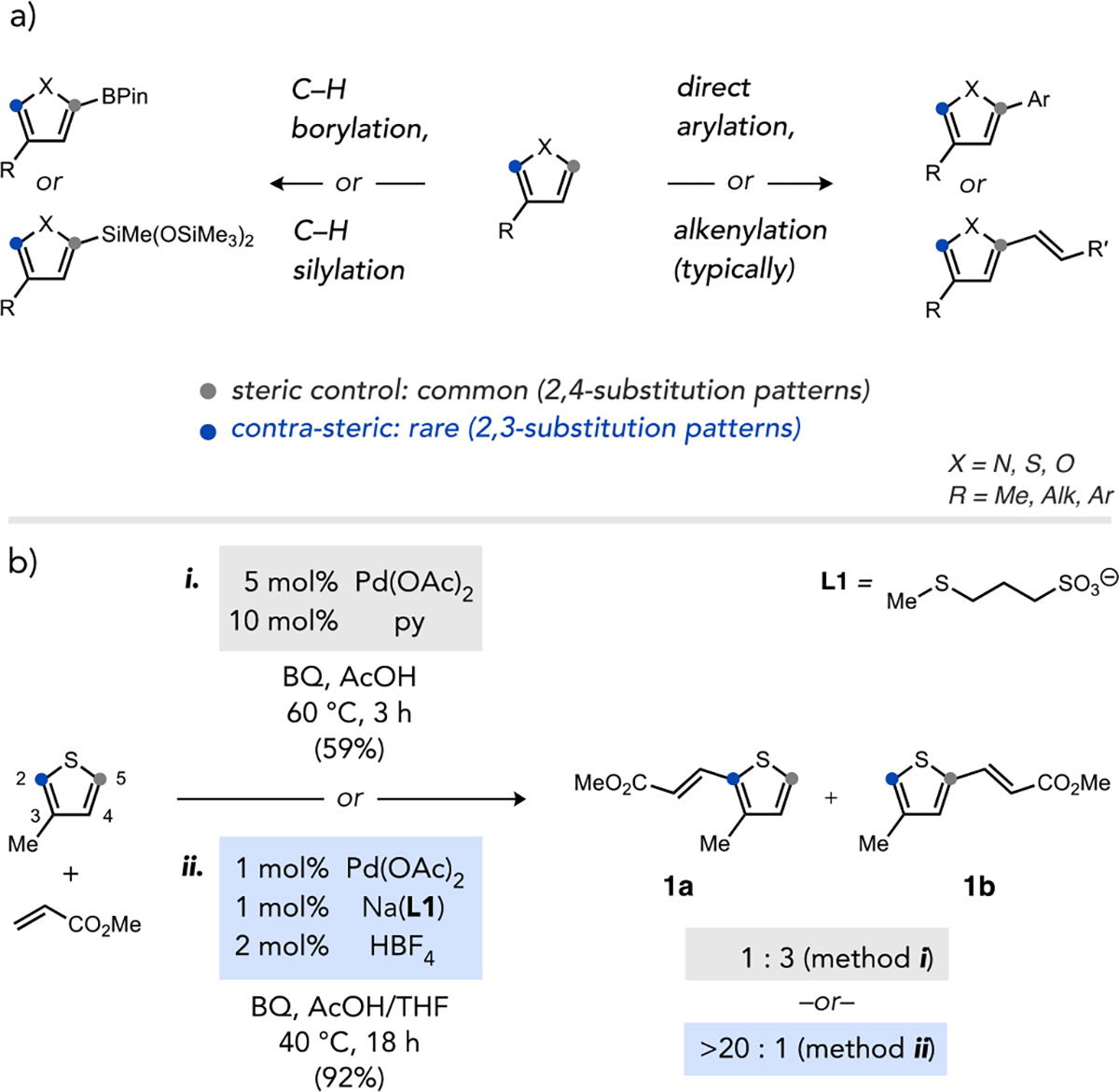

The transition states for C–H cleavage at C2 (contra-steric site) or C5 (steric control) in a prototypical substrate 3-methylthiophene (3-MT) were examined by DFT calculations. Geometry optimizations and transition state optimizations were performed using the BP86 functional with Stuttgart/Dresden ECP (SDD) basis set for Pd and 6–31G* basis set for other atoms. Solvent (AcOH) was modeled by a polarizable continuum model (PCM). Full computational details can be found in the Supporting Information. The respective transition states for heterolytic cleavage of C2–H (TS-2a vs TS-3a) or C5–H (TS-2b vs TS-3b) in 3-MT by either a pyridine-Pd(OAc)2 or (κ2S,O-L1)Pd(OAc) complex, respectively, are shown in Fig 2a.

Figure 2.

(a) Transition states (bond lengths in Å) and (b) More O’Ferrall–Jencks plot for C–H cleavage at C2 or C5 in 3-MT promoted by (py)Pd(OAc) or (κ2S,O-L1)Pd(OAc).

The Wiberg bond indices for the four base-assisted C–H cleavage transition states were then used to construct a More O’Ferrall–Jencks diagram (Fig 2b), which shows clear clustering of transition states for both the pyridine- and thioether-coordinated Pd(II) species within the eCMD region.23 Because the eCMD mechanism features build-up of partial positive charge on the substrate, these data predict both catalysts should exhibit electronic preferences favouring activation proximal to the inductively donating methyl substituent in 3-MT (e.g., C2). The transition states for the thioether-coordinated catalyst are displaced further from the synchronous diagonal, signifying a greater extent of polarization (bond-breaking exceeding bond formation) that should enhance site differentiation. However, this analysis alone does not account for the contrasting experimental site selectivity for the two Pd catalysts (Fig. 1b). Other effects of selectivity control were thus considered, in particular the potential for different selectivity-determining steps.

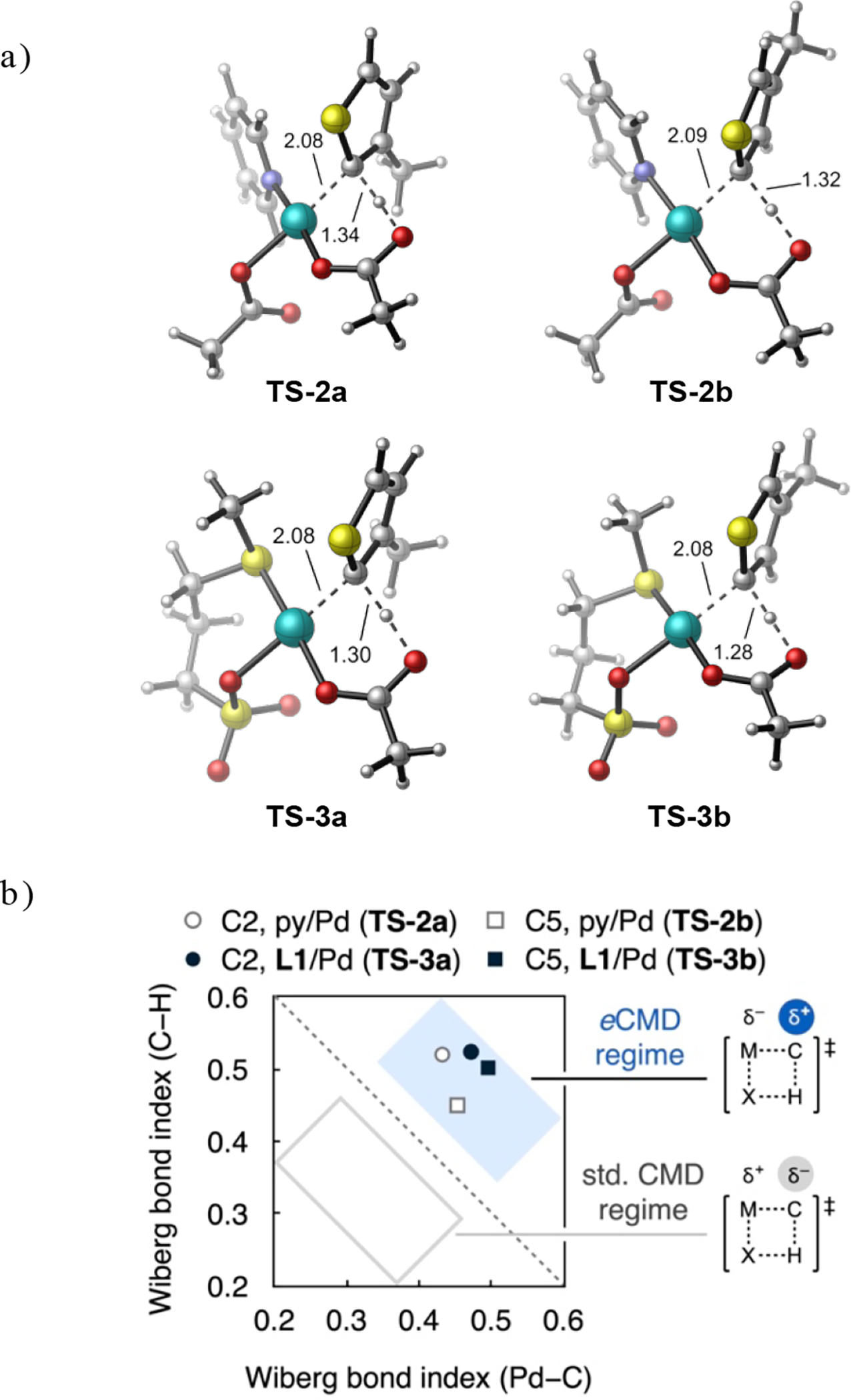

Kinetic isotope effect (KIE) values were determined for independent reactions of 3-hexylthiophene (3-HT) or 2,5-d2-3-HT in AcOH or AcOD solvent, respectively (Fig 3a). From C–H alkenylation reactions of the 3-HT isotopologues catalysed by L1/Pd(OAc)2, kH/kD values of 2.0(1) at C5 leading to the minor product isomer and 1.52(3) at C2 leading to the major product isomer were determined. In line with previous studies of thioether-coordinated Pd(II) catalysts,18, 22 these data are consistent with site selectivity occurring at the C–H cleavage stage and are consistent with this catalyst’s preference for the more π-basic C2 site. On the other hand, kH/kD values of 1.31(3) at C5 (major) and 0.87(8) at C2 (minor) site were determined from analogous C–H alkenylation reactions catalysed by pyridine-coordinated Pd(OAc)2. A secondary or inverse KIE, respectively, is inconsistent with C–H cleavage being irreversible and selectivity-determining at either site.

Figure 3.

(a) KIE values determined from independent C–H alkenylation reactions of 3-HT in AcOH or 2,5-d2-3-HT in AcOD. (b) Site incorporation of deuterium into excess 3-MT during C–H alkenylation in acetic acid-d4 catalysed by py/Pd(OAc)2.

An isotope scrambling experiment (Fig 3b) was conducted using a pyridine-Pd(OAc)2 catalyst for C–H alkenylation of 3-MT in acetic acid-d4. Deuterium incorporation at C2 of 3-MT was fast despite activation of this site correlating to formation of the minor product isomer using pyridine-coordinated Pd. We interpret these data and the inverse KIE at C2 (Fig 3a) as indicative of fast yet reversible C–H cleavage at this site. The reverse step, protodemetalation, is thus inhibited in the presence of deuterated acetic acid and product formation following migratory insertion becomes more kinetically favourable as a result. The experimentally observed selectivity for the pyridine-coordinated Pd catalyst thus does not contradict the More O’Ferrall–Jencks analysis of C–H cleavage mechanisms. Rather, eCMD is favoured in both cases and gives rise to faster activation of the most π-basic site in 3-MT (C2) using either catalyst. A catalytic step other than unfavourable C5–H activation must govern selectivity for the pyridine/Pd(OAc)2 catalyst to generate 1b as the major product.

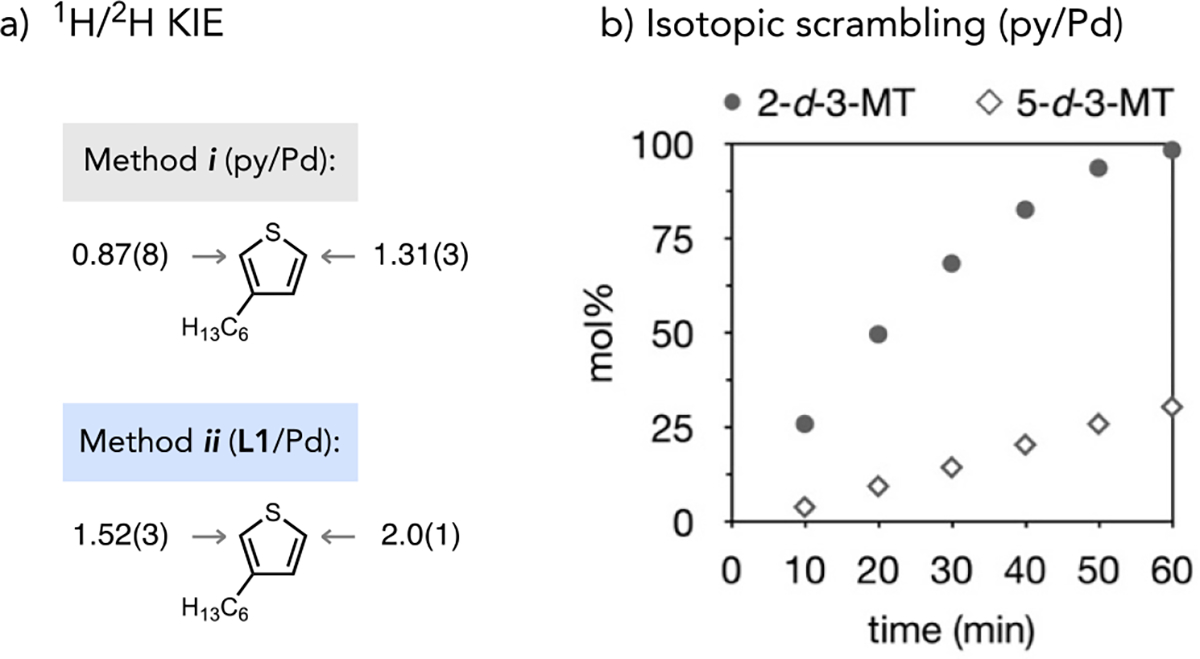

The potential for switching between reversible or irreversible C2 activation as a governing effect on the ligand-dependent site selectivity was evaluated further using DFT calculations. The key catalytic steps of substrate binding, C–H cleavage, alkene binding, then migratory insertion (Fig 4) were examined for both pyridine- or L1-coordinated Pd catalysts. Consistent with prediction based on the eCMD model, C–H cleavage in 3-MT beginning from (py)2Pd(OAc)2 (Fig 4a) kinetically favors C2 activation via TS-2a (ΔG‡ = 21.5 kcal/mol) relative to C5 activation via TS-2b (22.5 kcal/mol). Importantly, subsequent alkene migratory insertion is predicted to occur through higher energy barriers than either of the competing eCMD steps. These data are consistent with the small KIE values measured during C–H alkenylations with a pyridine-coordinated Pd catalyst. The alkene insertion barrier for the more sterically hindered C2-isomer of the aryl-Pd species via TS-8a (ΔG‡ = 30.6 kcal/mol) is slightly less favourable than the respective pathway (TS-8b) from the C5 organopalladium species (30.1 kcal/mol). These relative energies are qualitatively consistent with the experimental product distribution that modestly favours steric control. For the pyridine-coordinated Pd catalyst, C–H activation thus appears to be quasi- or fully reversible (see Fig 3b) prior to rate- and selectivity-determining alkene migratory insertion. Several alternative plausible reaction pathways through “ligandless” Pd species were also investigated for either the eCMD or alkene insertion steps, both of which occur with higher energy barriers relative to the respective pyridine-coordinated pathways.28

Figure 4.

Computed energy profiles for (a) (py)Pd-catalysed or (b) (L1)Pd-catalysed C–H cleavage at C2 or C5 in 3-MT then migratory insertion of acrylate. Energies in part (b) are referenced to 1/2 [(κ2S,O-L1)Pd(μ-OAc)]2 (S1).22 Geometry and transition state optimization were carried out at the BP86/SDD-6-31G* level of theory, including implicit solvent via PCM(AcOH). Free energies (enthalpies) in kcal/mol. aIon effects were mitigated by calculating exchange of L1 in 12a-b with OAc− in 10 to form S5.

Kinetic experiments were also used to gauge the dependence of initial rates on [alkene] and [3-HT] during pyridine-Pd(OAc)2-catalysed C–H alkenylation. From analysis of reactions at different [3-HT], fractional orders of 0.7 for activation at the C5 position and 0.3 for activation at C2 were estimated. At differing concentrations of [alkene], apparent orders of 0.3 (C5) and 0.6 (C2) were also estimated. The non-zero dependence of rates on [alkene] along with the calculated energy barriers and kinetic isotope data are consistent with alkene insertion being the turnover- and selectivity-determining step using a pyridine-coordinated Pd catalyst.

Initial rates measurements using the L1-coordinated Pd catalyst determined the major, C2 product formed with an apparent kinetic order of 0.1 and 0.3 with respect to [3-HT] and [alkene], respectively. For the minor, C5 product these values were 0.3 and 0.1 with respect to [3-HT] and [alkene], respectively. These small fractional values are difficult to interpret but could reflect saturation behavior we have observed in prior studies of related (thioether)Pd catalysts.18, 22 Considering the similarity of the calculated energy barriers for eCMD and alkene insertion using the thioether-Pd catalysts (vide infra), it may simply be the case that no one reaction step is rate-determining in this system.

The complementary reaction steps beginning from a thioether-coordinated Pd catalyst are illustrated in Fig 4b. Consistent with the notion that both pyridine- and L1-coordinated Pd species operate under the eCMD mechanism, C–H cleavage at C2 in 3-MT is kinetically favoured via TS-3a (ΔG‡, 16.7 kcal/mol) compared to the respective C5 activation pathway (TS-3b, 17.7 kcal/mol). The migratory insertion barriers involving L1-coordinated Pd species appeared unreasonably high (ΔG‡ = 26.8–26.9 kcal/mol).28 Prior studies by us had hinted substitutional lability is a beneficial property of thioether ligands like L1 in C–H functionalization reactions.18, 22 An alternative pathway was thus calculated in which L1 dissociation precedes C–C bond formation. While ligand dissociation is unfavourable for C–H cleavage, substitution of L1 for acetate after eCMD was beneficial to migratory insertion barrier. Alkene insertion barriers from the C2- and C5-isomers of the aryl-Pd species occurred through TS-14a (ΔG‡ = 15.9 kcal/mol) and TS-14b (15.6 kcal/mol), respectively, both of which fall just below the lower calculated barrier for C–H bond cleavage (e.g., TS-3a). A serial ligand catalysis29 scenario is suggested from these data that facilitates tuning of catalytic performance at different reaction stages through dynamic ligand exchange. Thioether ligand coordination enables facile eCMD whereafter exchange to a thioether-free catalytic state accelerates C–C bond formation.

In summary, More O’Ferrall–Jencks plot, isotopic exchange, kinetic isotope effect, and computational data were obtained to understand the ligand-switchable site selectivity for C–H alkenylation of 3-substituted thiophenes. These data are most consistent with a change in selectivity-determining step between pyridine- and thioether-coordinated Pd(II) catalysts. The contra-steric selectivity (C2) enabled by electrophilic (thioether)Pd(II) catalysts correlates to a highly polarized, selectivity-determining eCMD transition state for C–H cleavage that favors the most π-basic site and is selectivity-determining. In contrast, steric control is favoured by A pyridine-coordinated Pd catalyst also manifests the eCMD mechanism but C–H cleavage is (quasi)reversible at both sites followed selectivity-determining alkene insertion from the less-hindered organometallic intermediate in this system. The potential for serial ligand catalysis is also suggested from computational data and may indicate combinations of ligands could be to independently tune catalyst performance at different reaction stages. This mechanistic understanding should be informative for ongoing efforts to realize tunable catalyst control of base-assisted, nondirected C–H functionalization reactions.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Yamaguchi J; Yamaguchi AD; Itami K, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 8960–9009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wencel-Delord J; Glorius F, Nat. Chem 2013, 5, 369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartwig JF, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 2–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho J-Y; Iverson CN; Smith MR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 12868–12869. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishiyama T; Takagi J; Ishida K; Miyaura N; Anastasi NR; Hartwig JF, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 390–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho J-Y; Tse MK; Holmes D; Maleczka RE; Smith MR, Science 2002, 295, 305–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mkhalid IAI; Barnard JH; Marder TB; Murphy JM; Hartwig JF, Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 890–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng C; Hartwig JF, Science 2014, 343, 853–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng C; Hartwig JF, Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 8946–8975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karmel C; Rubel CZ; Kharitonova EV; Hartwig JF, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 6074–6081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H; Farizyan M; Ghiringhelli F; van Gemmeren M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 12213–12220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Bras J; Muzart J, Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 1170–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou L; Lu W, Chem. Eur. J 2014, 20, 634–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stuart DR; Villemure E; Fagnou K, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 12072–12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lapointe D; Markiewicz T; Whipp CJ; Toderian A; Fagnou K, J. Org. Chem 2011, 76, 749–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen H; Farizyan M; van Gemmeren M, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2020, 2020, 6318–6327. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Álvarez-Casao Y; Fernández-Ibáñez MÁ, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2019, 2019, 1842–1845. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorsline BJ; Wang L; Ren P; Carrow BP, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 9605–9614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mondal A; van Gemmeren M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 60, 742–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beckers I; Krasniqi B; Kumar P; Escudero D; De Vos D, ACS Catal 2021, 11, 2435–2444. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y-J; Yuan C-H; Chu D-Z; Jiao L, Chem. Sci 2020, 11, 11042–11054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L; Carrow BP, ACS Catal 2019, 9, 6821–6836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrow BP; Sampson J; Wang L, Isr. J. Chem 2020, 60, 230–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogge T; Oliveira JCA; Kuniyil R; Hu L; Ackermann L, ACS Catal 2020, 10, 10551–10558. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alharis RA; McMullin CL; Davies DL; Singh K; Macgregor SA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 8896–8906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies DL; Singh K; Tamosiunaite N, Dalton Trans 2020, 49, 2680–2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alharis RA; McMullin CL; Davies DL; Singh K; Macgregor SA, Faraday Discuss 2019, 220, 386–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.See Supporting Information for details.

- 29.Chen MS; Prabagaran N; Labenz NA; White MC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 6970–6971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.